Nvidia's $100B Open AI Deal Collapse: What Went Wrong [2025]

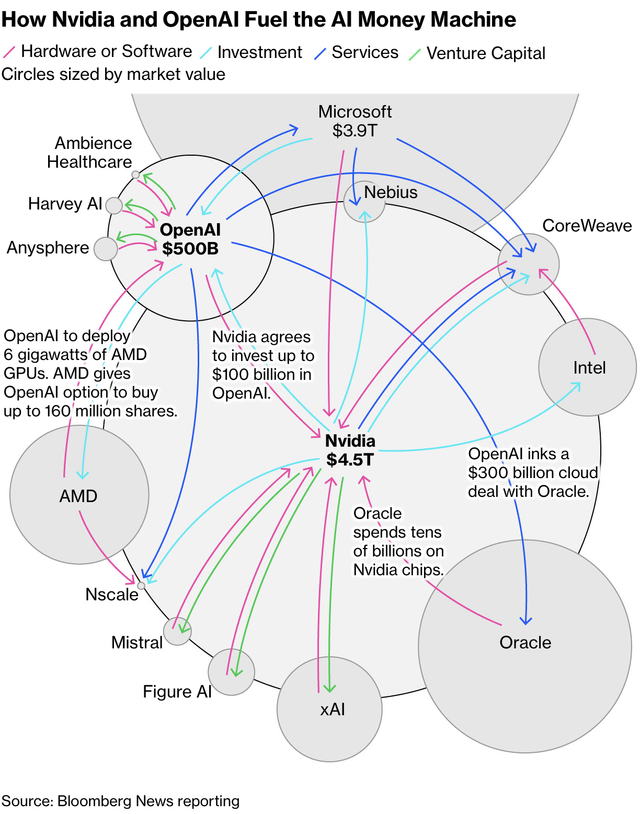

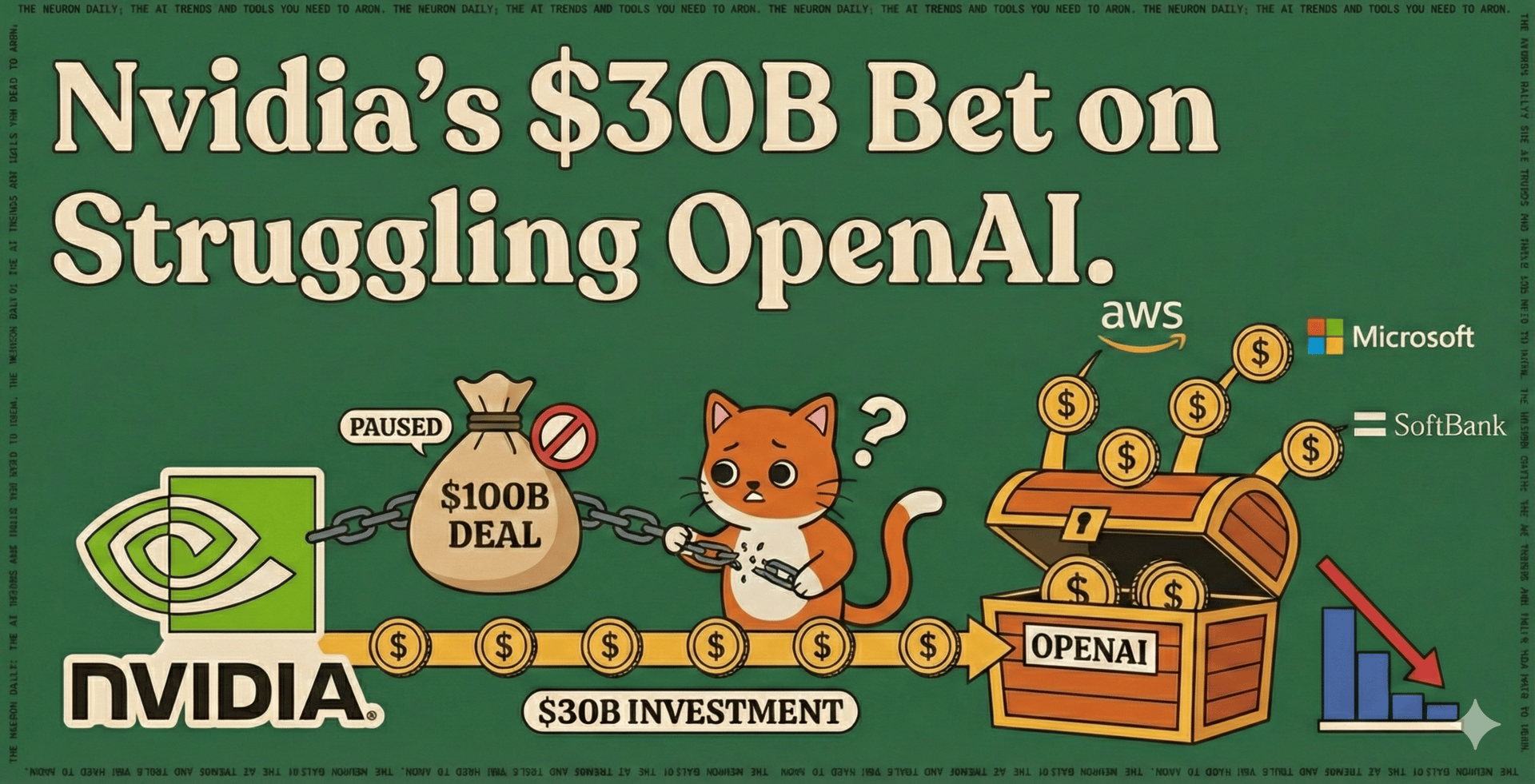

Back in September 2025, the tech world erupted. Nvidia and Open AI announced a letter of intent—Nvidia would invest up to $100 billion in Open AI's computing infrastructure. A hundred billion dollars. That's not pocket change. That's the kind of number that makes headlines, moves stock prices, and makes you wonder what you're missing in your own career.

Five months later? The deal quietly evaporated.

No official press release. No formal announcement that things fell through. Just Jensen Huang, Nvidia's CEO, casually telling reporters in Taiwan that the $100 billion figure was "never a commitment" as reported by Bloomberg. Then Reuters published a story suggesting Open AI had been quietly shopping for alternatives to Nvidia chips since last year. Suddenly, the narrative shifted from "AI titans joining forces" to "two billionaires' pipe dream collapsed quietly."

This isn't just a business story about two companies not getting along. This reveals something deeper about the AI infrastructure arms race—the desperation, the circular dependencies, and the uncomfortable truth that even when companies claim to be partners, they're really hedging bets against each other.

TL; DR

- The $100B deal was never binding: Nvidia and Open AI announced a letter of intent in September 2025, not a contract. Five months later, Huang said it was "never a commitment."

- Open AI actively explored alternatives: Reuters sources confirm Open AI was already talking to Cerebras and Groq about inference-optimized chips while publicly praising Nvidia.

- Performance problems sparked the split: Open AI staff blamed Nvidia's H100 and B200 GPUs for latency issues in their Codex tool, particularly for inference tasks.

- Nvidia played defense: After Reuters published damaging reports, Huang walked back statements and Nvidia struck a $20B licensing deal with Groq (one of Open AI's alternatives) to prevent them from competing.

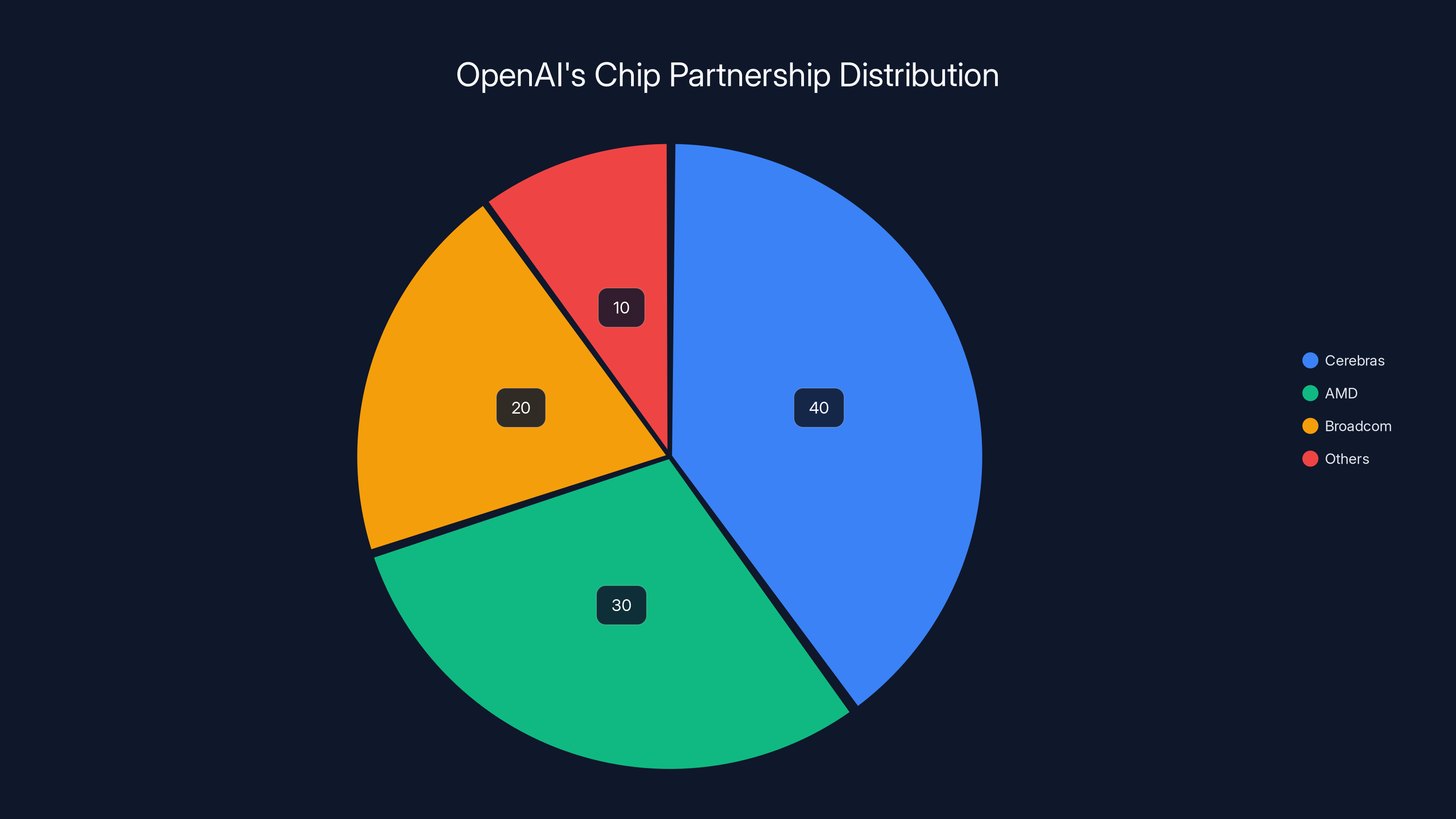

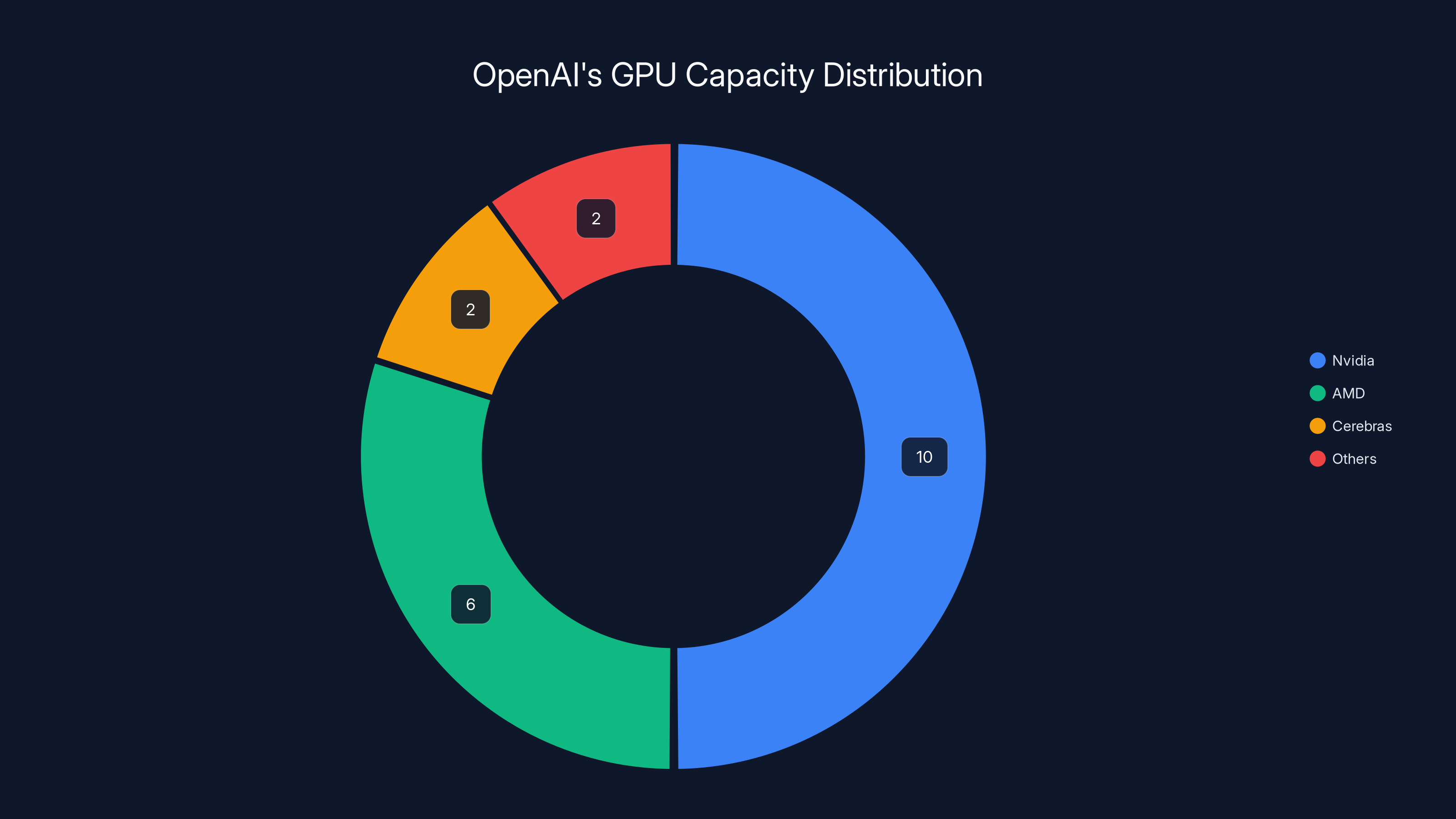

- Open AI is diversifying aggressively: Since the deal collapsed, Open AI inked a $10B Cerebras partnership, a separate AMD deal for 6GW of capacity, and announced plans for a custom Broadcom chip.

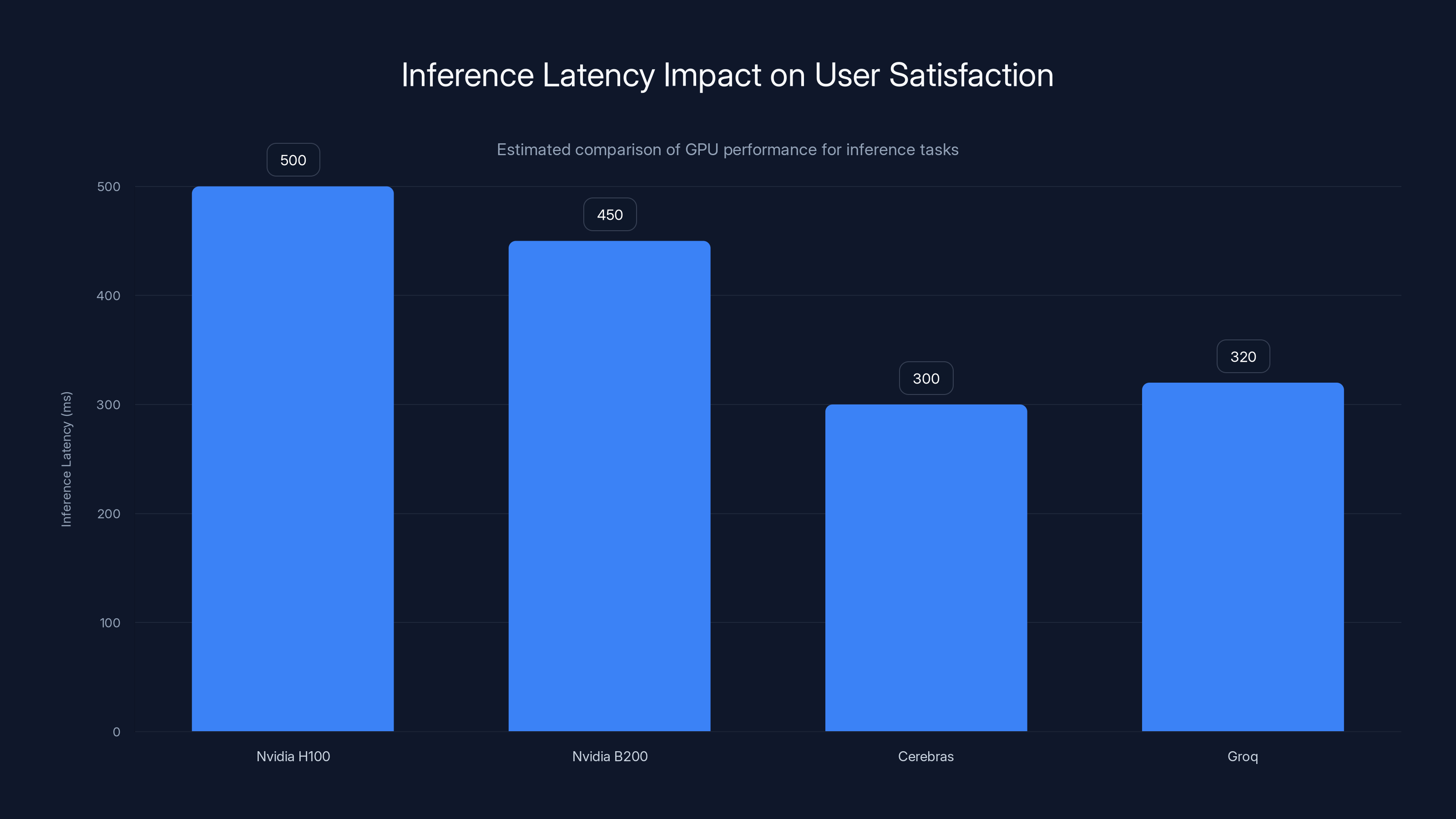

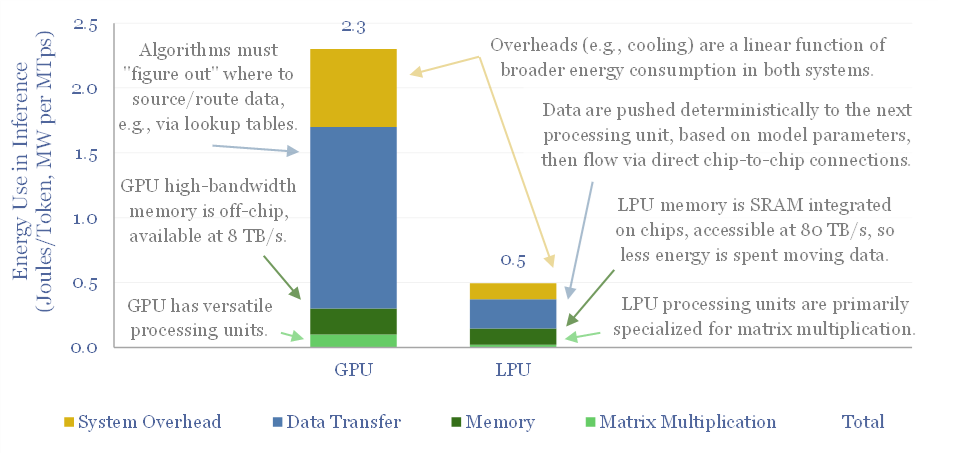

Estimated data suggests that alternatives like Cerebras and Groq may offer better inference performance than Nvidia, which is crucial for OpenAI's user-facing applications.

What Actually Happened in September 2025

Let's rewind. In September 2025, the announcement felt transformative. Nvidia would invest "up to $100 billion" in Open AI's infrastructure. The math was staggering: 10 gigawatts of Nvidia systems. Ten gigawatts. That's roughly the equivalent power output of 10 nuclear reactors. Jensen Huang told CNBC the project would consume Nvidia's total GPU shipments for an entire year.

"This is a giant project," Huang said, with visible excitement.

The announcement made sense superficially. Nvidia needed a flagship customer. Open AI needed computing power. They'd been working together for years. Huang has a history of making massive bets. Open AI's Sam Altman has a reputation for thinking big.

But here's what everyone glossed over: it was a letter of intent, not a binding contract. Not a signed deal. Not even close to a signed deal. A letter of intent is basically a "we're thinking about doing this" document. It's what you sign when you want to tell investors and the media you're serious, but you haven't actually committed to anything legally.

The details were vague. The timeline was vague. The actual terms were not finalized. In the announcement, both companies said they expected to "finalize details in the coming weeks."

Well. Those weeks came and went. And then some.

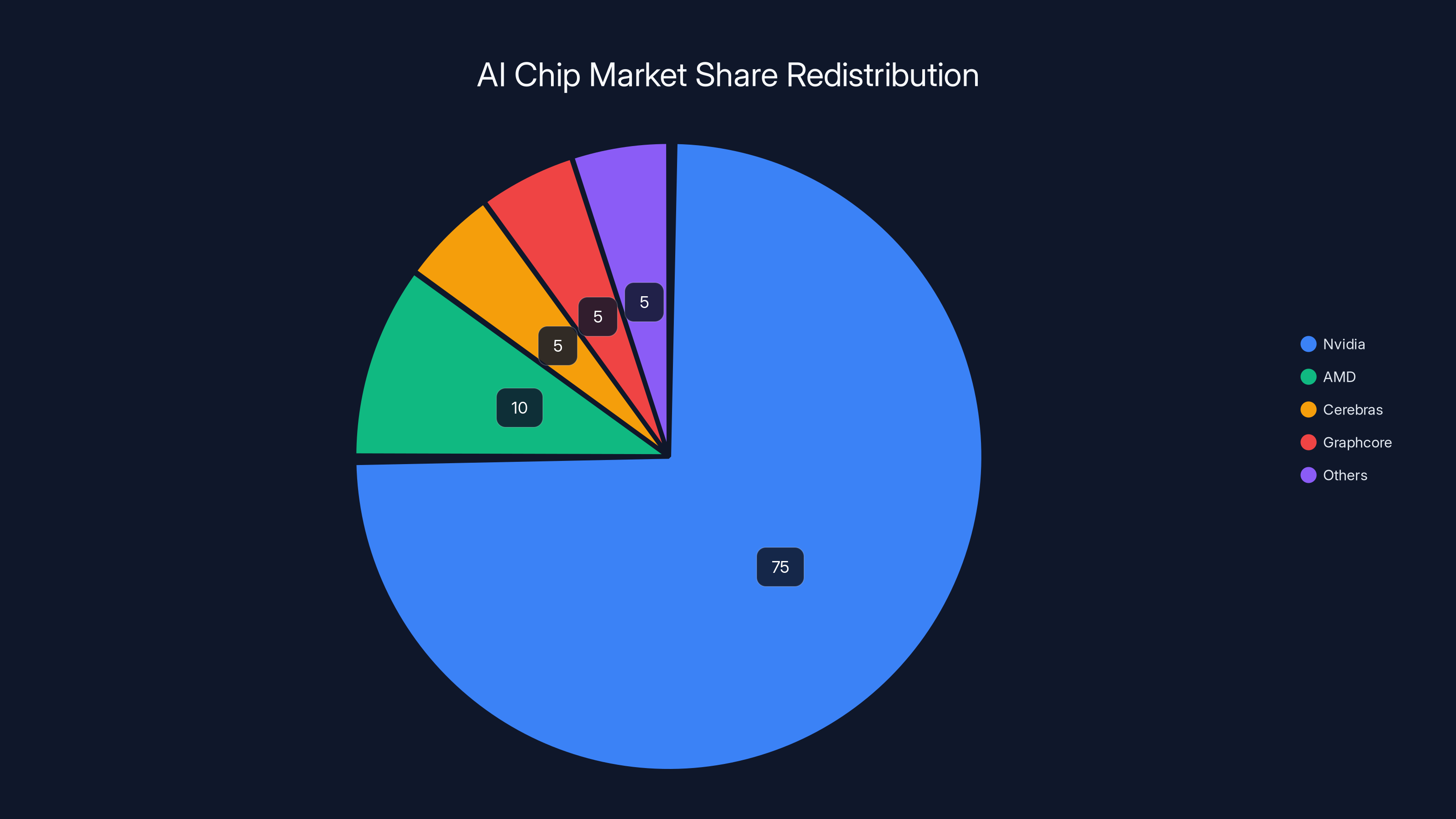

Estimated data shows Nvidia's market share could reduce to 75%, redistributing billions to competitors like AMD, Cerebras, and Graphcore.

The Performance Problem Nobody Wanted to Admit

While the PR teams were celebrating, something else was happening behind closed doors. Open AI engineers were frustrated.

According to Reuters' reporting, Open AI had been quietly exploring alternatives to Nvidia chips since at least 2024. The reason? Speed. Or rather, the lack of it.

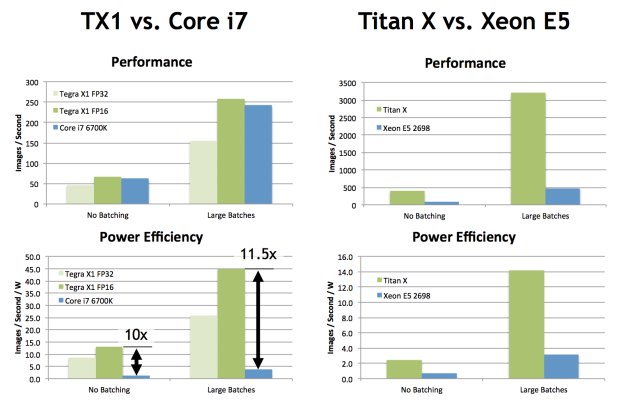

Nvidia's GPUs are optimized for training—the process where you take massive datasets and teach a neural network. But inference is different. Inference is when your trained model actually answers questions, generates text, produces code. It's what users interact with. It's also latency-sensitive. If your inference takes 5 seconds instead of 500 milliseconds, users notice. They get frustrated. They switch to competitors.

Open AI's Codex tool—their AI code-generation system—was suffering from performance issues. Staff members internally attributed these problems to Nvidia's hardware. The H100 and B200 GPUs just weren't optimized for the inference workloads Open AI needed to run at scale.

This is actually a well-known limitation in GPU design. You can't optimize for both training and inference equally. You have to make trade-offs. Nvidia chose to dominate training (because that's where the money was, historically). But as AI systems matured and inference became the bottleneck, Nvidia's architecture started showing its weak points.

Open AI couldn't exactly say this publicly. Nvidia had been their partner for years. Calling out performance problems publicly would burn bridges. So they did it quietly. They started talking to other chip companies.

Enter Cerebras and Groq.

The Groq Wrinkle and Nvidia's Countermove

Groq was the hotter story. Founded by Jonathan Ross (formerly a chip architect at Google), Groq had built an AI inference chip specifically designed to reduce latency. They called it the Groq LPU (Language Processing Unit), not a GPU. It was built from the ground up for transformer inference—the mathematical operation that powers language models.

Open AI was interested. So was everyone else, really. Groq had raised significant funding and was positioning itself as the "inference chip" alternative to Nvidia.

But then something interesting happened.

In December 2024, Nvidia struck a $20 billion licensing deal with Groq. Part of the deal included Nvidia hiring Jonathan Ross, Groq's founder and CEO, along with other senior leaders.

According to Reuters sources, this deal essentially killed Open AI's partnership discussions with Groq. Why? Because Groq's founder and key technical talent moved to Nvidia. The company lost its autonomous vision. Groq became effectively a Nvidia subsidiary.

It was a masterful defensive move. Nvidia couldn't prevent Open AI from exploring alternatives, but they could acquire—or at least neutralize—those alternatives.

This pattern repeats throughout tech. When a competitor gains traction, you either beat them or absorb them. Rarely do you genuinely lose. Nvidia chose absorption.

Estimated data shows that Cerebras and Groq offer lower inference latency compared to Nvidia's H100 and B200, potentially improving user satisfaction and reducing compute costs.

The Circular Investment Problem

Before we move forward, there's something important to understand about how Nvidia operates. It's not malicious, exactly. But it's worth examining.

Nvidia gives money to companies. These companies then buy Nvidia chips. In the case of the proposed Open AI deal, here's how it would've worked:

- Nvidia invests $100 billion in Open AI

- Open AI uses that money to buy Nvidia hardware

- The money flows back to Nvidia

- Nvidia records the revenue

It's not a straight circle—there are complexities, tax implications, time delays. But the basic dynamic is circular. Nvidia's investment essentially guarantees its own revenue.

Tech critic Ed Zitron pointed this out forcefully after the September announcement. "NVIDIA seeds companies and gives them the guaranteed contracts necessary to raise debt to buy GPUs from NVIDIA," he wrote. "Even though these companies are horribly unprofitable and will eventually die from a lack of any real demand."

This isn't a Zitron invention. It's a recognized pattern. Nvidia has done this with dozens of companies—big players, startups, everyone in between. They all become Nvidia customers. They all are guaranteed Nvidia contracts. None of them are making real money independently.

For Open AI, the dynamic was uncomfortable. Yes, you get $100 billion. But you're committing to be a massive Nvidia customer. You're entrenching yourself with one vendor. You're also proving the point that your business model depends on Nvidia's infrastructure.

Nvidia needed Open AI's money more than Open AI needed Nvidia's investment. But Nvidia had the hardware.

That's leverage.

Cerebras: The Pragmatic Alternative

While Groq's leadership was moving to Nvidia, Open AI was having more successful conversations with Cerebras.

Cerebras is another startup building inference-optimized AI chips. In January 2025 (just weeks after the Groq deal collapsed), Open AI announced a $10 billion partnership with Cerebras. The deal promised 750 megawatts of computing capacity for faster inference through 2028.

Sachin Katti, who'd just joined Open AI from Intel to lead compute infrastructure, framed it as adding a "dedicated low-latency inference solution" to Open AI's platform.

The difference between this deal and the Nvidia proposal is worth noting. This wasn't an investment. This was a capacity agreement. Open AI got hardware access. Cerebras got a guaranteed customer. The terms were explicit and time-bound (through 2028). Both parties had aligned incentives.

No circular money. No ambiguous letters of intent. Just a straightforward commercial relationship.

That's the model that works. That's what Open AI clearly wanted all along.

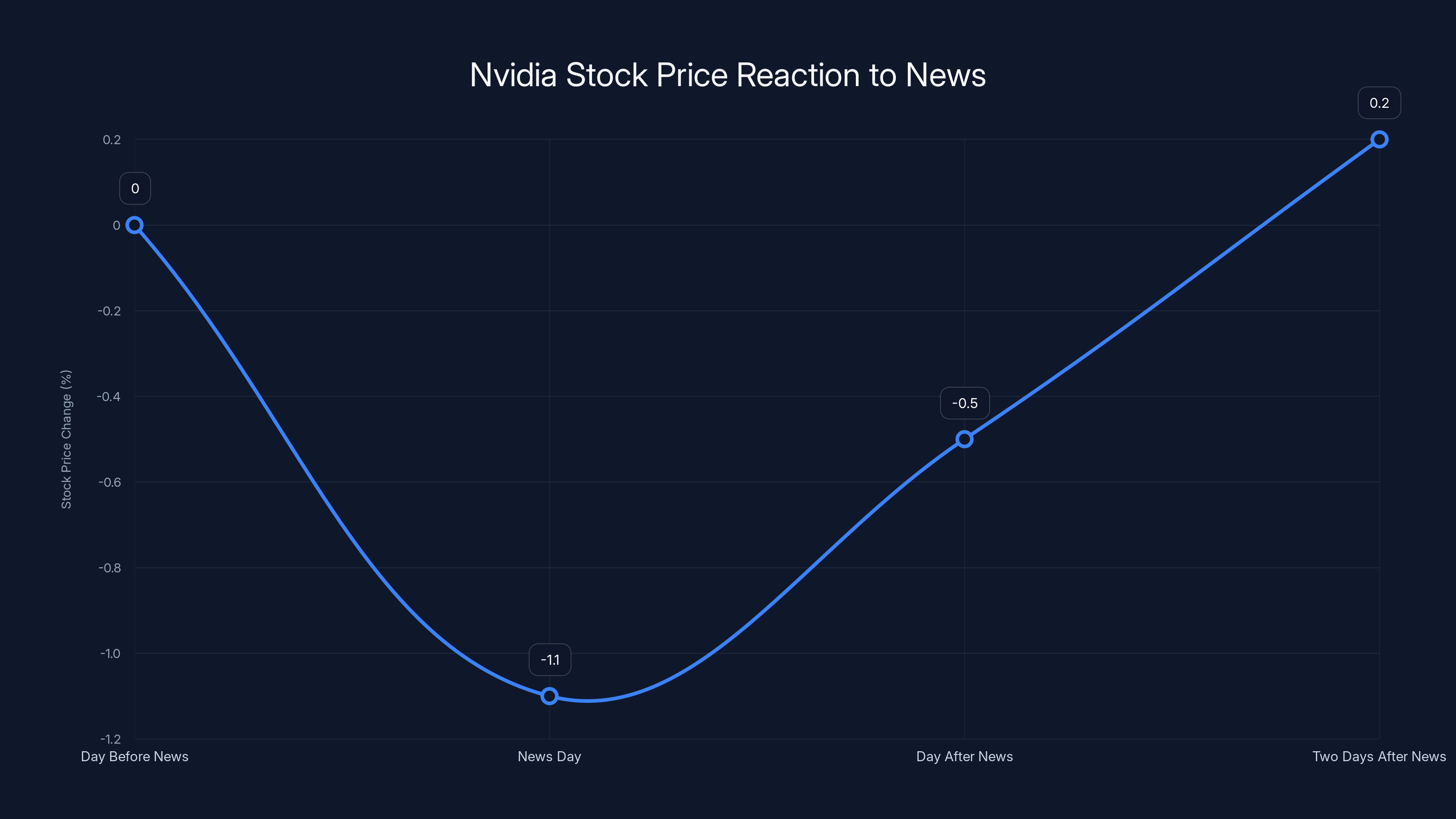

Nvidia's stock price dropped by 1.1% on the day of the news, indicating a loss of investor confidence. Estimated data for subsequent days shows partial recovery.

AMD: The Second Bet

While the Cerebras deal was being finalized, Open AI had struck another bargain. In October 2024, before the Cerebras announcement even, Open AI made a deal with AMD for six gigawatts of GPU capacity.

Six gigawatts. That's not trivial. For context, the Nvidia deal was supposed to be 10 gigawatts. So Open AI essentially found 60% of the capacity they allegedly needed from Nvidia through AMD instead.

AMD's chips aren't as efficient as Nvidia's for training large models. Everyone knows this. But for inference? AMD's approach is competitive. And importantly, AMD was hungry for customers. They wanted the Open AI partnership more than Nvidia wanted anything at this point.

So Open AI got favorable terms. They got capacity. They diversified their supply chain.

This is the pattern emerging: Open AI is taking the money that was theoretically going to Nvidia and spreading it across multiple vendors. Cerebras. AMD. Broadcom (for custom chip development). The goal is obvious: reduce dependence on any single supplier.

The Broadcom Wildcard

Here's where it gets interesting. In addition to external partnerships, Open AI announced plans with Broadcom to develop a custom AI chip.

Broadcom is a semiconductor company, but not in the "AI chip" business the way Nvidia, AMD, or Cerebras are. Broadcom makes networking chips, infrastructure components, and has significant semiconductor manufacturing partnerships.

The plan: co-develop a custom AI chip designed specifically for Open AI's inference needs.

This is the ultimate hedge. Why rent chips from Nvidia when you can design your own? Why use generic GPUs optimized for everyone's workload when you can build something optimized specifically for your models?

The timeline is unclear. Custom chip development takes 2-3 years minimum. But once complete, Open AI would have hardware they actually own. Hardware designed for their software. Hardware where Nvidia has no leverage.

This is existential for Nvidia. If Open AI, Google, Meta, and other major AI labs all develop custom chips, Nvidia's monopoly breaks. The companies that control the compute control the AI industry. Right now, Nvidia controls the compute. But that era might be ending.

OpenAI has diversified its chip partnerships, with significant investments in Cerebras and AMD. Estimated data based on reported deals.

Jensen Huang's Spin, Then Walk-Back

After Reuters published the damaging story in February 2026, things got messy.

First, the damage control. Sam Altman posted on X: "We love working with NVIDIA and they make the best AI chips in the world. We hope to be a gigantic customer for a very long time. I don't get where all this insanity is coming from."

Translation: "The Reuters story is overblown. We still love Nvidia. Please don't sell Nvidia stock."

Then Jensen Huang's response. At first, he defended the partnership: "We are going to make a huge investment in Open AI," he said. "Sam is closing the round, and we will absolutely be involved. We will invest a great deal of money, probably the largest investment we've ever made."

Sounds good. Sounds committed.

Then the reporter asked: "Will it be $100 billion?"

Huang's response: "No, no, nothing like that."

There it is. The admission. The $100 billion figure—the headline number, the number that moved markets, the number that was in every announcement—was never real.

Huang called it a "letter of intent amount." Meaning Nvidia invited Open AI to potentially invest up to $100 billion, but neither party ever actually intended to spend that much.

This is a crucial distinction. An LOI that says "up to

A Wall Street Journal report added more color. Nvidia insiders had expressed doubts about the transaction. Huang had privately criticized Open AI's lack of "business discipline." Huang worried about competition from Google and Anthropic.

Huang called these claims "nonsense." But the pattern was clear. Privately, Nvidia was concerned. Publicly, they were enthusiastically behind the deal. When Reuters pried open the gap between private and public, the spin started failing.

The Stock Price Reaction

Nvidia shares fell about 1.1% on Monday following the Reuters reports and Huang's comments.

1.1% might not sound like much. But for a company with a market cap in the multi-trillions, 1.1% is billions of dollars. It's also a sign of lost confidence.

Sarah Kunst, managing director at Cleo Capital, told CNBC something important: "One of the things I did notice about Jensen Huang is that there wasn't a strong 'It will be $100 billion.' It was, 'It will be big. It will be our biggest investment ever.' And so I do think there are some question marks there."

Kunst is right. Huang's original statements were hedged. He never committed to

The stock price reflected that lost certainty.

OpenAI's GPU capacity deals in 2024 show a strategic diversification with 60% of Nvidia's capacity sourced from AMD, highlighting a shift to reduce supplier dependency. (Estimated data)

What This Reveals About AI Infrastructure

Zoom out. This isn't just about Nvidia and Open AI. This reveals something systemic about the AI infrastructure market.

First: The industry is desperate for alternatives to Nvidia. If one company had all the leverage, there'd be no need for Cerebras, Groq, AMD investments. The fact that Open AI is spreading money across multiple vendors signals they're uncomfortable with Nvidia dependency.

Second: Nvidia's performance advantages are narrowing. For training, Nvidia is still king. But for inference—the operational workload—other solutions are becoming competitive. That's a threat to Nvidia's long-term dominance.

Third: Custom chips are inevitable. Every major AI lab will eventually build custom hardware. Google has TPUs. Meta is building custom chips. Open AI is working with Broadcom. Microsoft has custom silicon in development. Custom hardware gives you control, performance, and independence. Once this trend finishes, Nvidia's leverage evaporates.

Fourth: The circular investment model is under scrutiny. When Nvidia invests $100 billion in Open AI (theoretically) and Open AI immediately becomes a massive Nvidia customer, questions arise about the real economics. Is Open AI viable without Nvidia's infrastructure capital? What happens when Nvidia needs the money back? These questions matter, and the deal falling apart suggests the economics didn't work.

Fifth: Vendor lock-in is becoming a business risk. Companies that depend entirely on one vendor have limited negotiating power. Open AI realized this and started diversifying. Every smart company will follow this pattern.

The Timing: Why Now?

Why did this deal collapse in early 2026, five months after announcement?

The Reuters story gives clues. Open AI's dissatisfaction with Nvidia performance wasn't new. It had been ongoing since at least 2024. But the deal announcement happened anyway in September 2025. Something must have shifted.

Possible theory: Open AI realized during due diligence that actually integrating $100 billion of Nvidia systems wouldn't solve their inference problems. The money would be wasted on hardware that didn't solve their core issue. Better to redirect that toward specialized inference chips from Cerebras, AMD, and custom development.

Alternative theory: Nvidia and Open AI were pursuing different business models. Nvidia wanted Open AI locked into a long-term dependency. Open AI wanted optionality. Those goals are incompatible. The deal collapsed because the fundamental incentives never aligned.

Most likely: Both are true. Open AI wanted alternatives. Nvidia realized Open AI wasn't a captive customer. Both sides recognized the deal would tie them together in ways neither wanted. Better to have a smaller, more focused relationship.

The September announcement was the hopeful phase. The February walk-back was reality hitting.

Implications for the Broader AI Industry

This collapse matters beyond just Nvidia and Open AI. It signals several things to the industry.

For AI startups: Don't become entirely dependent on Nvidia. Diversify. Use AMD, Cerebras, custom chips when possible. The companies that build multi-vendor capabilities will be more resilient.

For infrastructure investors: The race to build alternatives to Nvidia is real and accelerating. Cerebras, Groq (despite Nvidia's acquisition), Graphcore, and others have viable products. This isn't a dud. This is the birth of a competitive market.

For cloud companies: AWS, Google Cloud, and Azure all saw the Nvidia deal collapse. They should be investing heavily in custom silicon. Cloud margins depend on infrastructure efficiency. Nvidia's leverage is a risk. Custom chips are insurance.

For large language model companies: The era of outsourcing all compute to Nvidia infrastructure is ending. Companies that own or control their hardware will have competitive advantages. Control over latency, cost, and performance is too important to outsource entirely.

For investors: Nvidia's dominance is being questioned seriously for the first time. The stock won't crash tomorrow. But the certainty of its monopoly is gone. Other companies will gain share. Diversified portfolios matter.

The Competitive Landscape Post-Collapse

With the Nvidia-Open AI deal fallen apart, the competitive landscape is reshaping.

Cerebras is positioning itself as the inference specialist. They're taking real customer commitments (Open AI $10B) and delivering hardware. If they execute, they become the go-to for inference workloads.

AMD is using its cost advantage and willingness to sell to customers Nvidia neglects. Six gigawatts to Open AI is substantial. If Open AI's experience with AMD inference is positive, others will follow.

Groq has lost its independence but retained its technology. Whether Nvidia actually productizes Groq's LPU or lets it languish is unclear. If they productize it, they're admitting they need an alternative to their own H100 architecture. That's a statement.

Broadcom's custom chip development could be the wild card. If successful, it creates a template for others. Every major company wants custom hardware optimized for their workloads. Broadcom could become the infrastructure partner for this trend.

Meanwhile, Nvidia isn't going anywhere. They still make the best training GPUs. They still have the best software ecosystem (CUDA). They still have the installed base. But the assumption of inevitable dominance is gone.

What Happens to Open AI's Compute Strategy

Open AI now has multiple infrastructure partners, multiple vendors, and a custom chip in development. That's a diversified portfolio.

Short term (next 12 months): Open AI relies on Cerebras for inference, AMD for GPU capacity, and existing Nvidia systems for training. They're probably also running some workloads on Azure infrastructure using their partnership with Microsoft.

Medium term (12-36 months): The Broadcom custom chip enters production. Open AI starts moving inference workloads onto their own silicon. They need less Cerebras capacity. They need less AMD capacity. Nvidia is still their primary training vendor but no longer the bottleneck.

Long term (3+ years): Open AI has its own hardware for inference. They've optimized for their specific models. They're competitive on cost and performance. Their dependence on external vendors shrinks dramatically. They might actually become a competitor, selling custom chips or inference-as-a-service using their own hardware.

This trajectory is available to every large AI company. Google, Meta, Microsoft, Anthropic—they're all following similar paths. Custom hardware becomes the endgame. Vendor dependency becomes a competitive disadvantage.

Nvidia's job is to remain essential in the areas where custom hardware doesn't make sense: training, research, small-scale deployments, general-purpose compute.

That's still a massive market. But it's not the only market anymore.

The Broader Economic Signal

Here's what this story tells us about the AI economy more broadly.

First: We're in a transition from "one vendor dominates" to "multiple vendors compete." This is healthy. Competition drives innovation. It drives prices down. It prevents monopolistic practices.

Second: Companies that became successful during the Nvidia monopoly period need to quickly adapt. If your business model depended on Nvidia being the only reliable option, that model is under threat.

Third: The capital intensity of AI is shifting. Instead of "buy someone else's chips," the equation becomes "design your own hardware." This requires different expertise, different partnerships, different timelines. Companies that master this transition will dominate.

Fourth: The circular investment model is being questioned. When you invest in someone to guarantee they buy from you, the incentives are misaligned. Open AI's willingness to walk away signals that these circular deals aren't as valuable as they seem.

Fifth: Vendor lock-in is the new battleground. Companies want to avoid it. Vendors want to enforce it. The companies with leverage (Open AI, Google, Meta) are winning this battle. Smaller companies don't have that luxury.

Lessons for Enterprise Buyers

If you're an enterprise technology buyer considering major infrastructure investments, this story offers lessons.

First: Avoid circular deals. When a vendor offers you capital and guarantees their revenue back through your purchases, be skeptical. The vendor is betting on their ability to lock you in. If you're considering such a deal, ensure you have genuine optionality and exit rights.

Second: Diversify vendors. No single vendor should be irreplaceable. Spread critical workloads across multiple suppliers. This costs more upfront but saves money and risk long-term.

Third: Consider custom solutions. If your workloads are unique and large-scale enough, invest in custom infrastructure. It's expensive but gives you control and competitive advantages.

Fourth: Track performance claims carefully. When vendors make performance assertions, validate them against real-world workloads. Nvidia's GPUs are amazing for training but not optimal for inference. Different workloads need different solutions.

Fifth: Read between the lines on announcements. When a CEO says "up to

The Road Ahead

Where does this go from here?

Nvidia will remain dominant in training. They'll continue developing faster, better chips. The H100 and B200 are incredible. Future generations will be even better. For companies building new models from scratch, Nvidia is still the choice.

But inference is the new frontier. That's where Open AI, Google, Meta are focusing. That's where custom chips make sense. That's where the competitive market is opening up.

Cerebras will grow. Groq's technology will probably end up in Nvidia products (that's what happens when you acquire a startup—you absorb its IP). AMD will gain share. Custom chip development will become standard practice.

In five years, the chip landscape will look very different. Nvidia won't be a monopoly. They'll be the leading player in a competitive market. That's a healthy outcome for the industry.

For Nvidia shareholders, it means slower growth rates than the past 18 months. For customers, it means more options, better prices, and less vendor lock-in. For the AI industry, it means innovation accelerates because competition drives it.

The $100 billion deal that never was signals the beginning of the end for Nvidia's unilateral control. The next phase is more interesting: genuine competition, multiple winners, and an industry growing up.

Conclusion: From Hype to Reality

The Nvidia-Open AI deal collapse tells a specific story about two companies, but it's really a story about the AI infrastructure market mattering.

In September 2025, the narrative was simple: Two giants combine to reshape AI infrastructure. Nvidia invests billions. Open AI gets resources. Everyone wins. The story fit perfectly into the tech press's appetite for mega-deals and transformative partnerships.

But the real world is messier. Open AI had performance problems Nvidia couldn't solve. Nvidia had circular incentives that didn't serve Open AI. Both companies wanted things the other couldn't provide. So the deal quietly fell apart.

Five months later, we have the real story. Open AI didn't need Nvidia's capital. They had better options. Alternatives existed. Vendors wanted their business. The leverage shifted from Nvidia to Open AI.

This shift is the actual story. Not the $100 billion that was never real. But the diversification, the custom chips, the competition that's now underway.

When a startup builds inference-optimized chips and lands Open AI as a customer, that's meaningful. When AMD gains capacity orders in the gigawatts, that's meaningful. When major AI labs start designing custom hardware, that's meaningful.

These developments don't kill Nvidia. They reshape the market. They break the assumption of perpetual dominance. They create space for competition.

Looking ahead, the winners will be the companies that control their own infrastructure. The losers will be the companies dependent on a single vendor. Nvidia remains essential, but no longer sufficient.

The $100 billion deal that vanished actually revealed something valuable. It showed us that even the biggest tech companies are rethinking their infrastructure strategies. The era of outsourcing everything to one vendor is ending. The era of diversified, custom, competitive infrastructure is beginning.

That's worth paying attention to—not because of a deal that fell apart, but because of what the collapse signals about where the industry is heading.

FAQ

Why did Nvidia and Open AI announce a $100 billion deal and then abandon it five months later?

The announcement was a letter of intent, not a binding contract. Both companies expected to finalize details "in the coming weeks," but due diligence revealed incompatible incentives. Open AI faced performance limitations with Nvidia chips for inference tasks and wanted to diversify suppliers. Nvidia wanted guaranteed revenue through customer lock-in. When both parties realized the deal wouldn't serve their actual needs, they let it quietly expire rather than renegotiate.

Was the $100 billion figure ever actually real?

No. Jensen Huang later admitted it was a ceiling, not a commitment. The announcement said "up to

What performance problems did Open AI have with Nvidia chips?

Open AI's Codex tool experienced latency issues, particularly for inference tasks (generating responses from trained models). Nvidia's GPUs are optimized for training—teaching models on massive datasets—but not for inference, where latency matters enormously to user experience. Open AI staff internally attributed these performance limitations to Nvidia's GPU architecture, which prompted them to explore alternatives from Cerebras and Groq.

What are inference and training, and why does Open AI care about the difference?

Training is the computationally expensive process of teaching a model on massive datasets. Inference is when a trained model generates outputs for user queries. Nvidia's hardware excels at training but isn't optimized for inference. Open AI cares about inference because that's what users interact with daily—and if inference is slow, users notice and switch to competitors. Custom inference-optimized chips (from Cerebras, Groq, or internally developed) matter far more for user experience than training performance.

Did Nvidia acquire Groq to prevent Open AI from using them?

Nvidia struck a $20 billion licensing deal with Groq and hired Groq's founder Jonathan Ross. According to Reuters sources, this deal effectively ended Open AI's partnership discussions with Groq. While Nvidia framed it as an acquisition of talent and technology, the practical effect was neutralizing a competitor that Open AI was interested in. It's a defensive move—if Nvidia can't keep Open AI as a customer, acquiring their alternatives is the next best thing.

What partnerships does Open AI have now instead of the Nvidia deal?

Open AI has diversified its infrastructure strategy significantly. They announced a $10 billion partnership with Cerebras for inference capacity through 2028, struck a deal with AMD for six gigawatts of GPU capacity, and are developing a custom AI chip with Broadcom. Each partnership targets specific needs: Cerebras for low-latency inference, AMD for cost-effective GPU capacity, and Broadcom for long-term hardware independence through custom silicon.

Is Nvidia in trouble because of this deal collapse?

No, Nvidia remains the dominant player in AI chips, especially for training. The deal collapse doesn't threaten Nvidia's core business—it just breaks the assumption that Nvidia would have unilateral control forever. Nvidia will remain essential for training but faces growing competition in inference. The company's growth rate might slow, but the market is still massive, and Nvidia is still winning most of it.

What does this mean for companies buying AI infrastructure?

The lesson is clear: avoid becoming entirely dependent on a single vendor. Diversify across multiple suppliers, consider custom solutions if your workloads are large enough, and carefully examine circular investment deals where a vendor invests in you primarily to guarantee their own revenue. The companies that build vendor flexibility into their infrastructure will be more resilient and competitive long-term.

Will other companies build custom AI chips like Open AI is doing?

Yes. Google has TPUs, Meta is developing custom silicon, Microsoft is working on custom chips, and Anthropic will likely follow. Every major AI lab will eventually build custom hardware because it provides control, performance optimization, and independence from vendor lock-in. Custom chips are becoming table stakes for large-scale AI infrastructure.

How does this reshape the competitive landscape for AI chips?

The market is transitioning from Nvidia monopoly to competitive plurality. Training will remain Nvidia-dominated for now, but inference is becoming competitive with Cerebras, AMD, and custom solutions gaining share. In 3-5 years, the landscape will look very different: multiple vendors will coexist, prices will be more competitive, and customers will have genuine optionality. This is healthy for the industry and drives innovation.

Key Takeaways

- Nvidia's $100B investment in OpenAI was never a real commitment—just a theoretical ceiling in a letter of intent that both parties quietly abandoned after five months

- OpenAI suffered inference performance limitations with Nvidia GPUs and systematically explored alternatives (Cerebras, Groq, AMD) while publicly praising Nvidia

- The circular investment model—where Nvidia invests in OpenAI, guaranteeing OpenAI becomes a Nvidia customer—has structural flaws that became apparent during due diligence

- Custom chip development is becoming existential for major AI labs; OpenAI's Broadcom partnership, Google's TPUs, and Meta's custom silicon signal the end of vendor-dependent infrastructure

- Market leadership is shifting from Nvidia's single-vendor dominance to a competitive landscape where specialized chips (inference), cost alternatives (AMD), and custom solutions (Broadcom, internal) fragment the market

Related Articles

- Nvidia's $100B OpenAI Gamble: What's Really Happening Behind Closed Doors [2025]

- NVIDIA's $100B OpenAI Investment: What the Deal Really Means [2025]

- Intel's GPU Strategy: Can It Challenge Nvidia's Market Dominance? [2025]

- Microsoft Killing OneDrive and SharePoint Plans: What You Need to Know [2025]

- OpenAI Staff Exodus: Why Senior Researchers Are Leaving 2025

- SpaceX Acquires xAI: The 1 Million Satellite Gambit for AI Compute [2025]

![Nvidia's $100B OpenAI Deal Collapse: What Went Wrong [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/nvidia-s-100b-openai-deal-collapse-what-went-wrong-2025/image-1-1770160007724.jpg)