Orbital AI Data Centers: Technical Promise vs. Catastrophic Risk [2025]

Last month, Elon Musk made an announcement that sounded like science fiction: his two companies, SpaceX and xAI, would merge operations and launch one million satellites into orbit to function as distributed AI data centers. On paper, the idea has merit. Solar panels in space collect energy without atmospheric interference. No clouds blocking sunlight. No cooling requirements like ground-based facilities. Within three years, Musk claimed, orbital compute would be cheaper than anything we can build on Earth.

But here's where things get uncomfortable: if executed at that scale, this plan could fundamentally break low Earth orbit (LEO) and trigger an environmental catastrophe that makes every other space sustainability concern look quaint.

I've spent the last few weeks digging into the technical feasibility, the environmental implications, and why experts from orbital mechanics to climate science are sounding alarm bells. The reality is messier than Musk's optimism suggests. It's also more consequential than most people realize.

TL; DR

- The Plan: SpaceX and xAI aim to deploy 1 million satellites in low Earth orbit as AI data centers, citing superior solar efficiency and lower operational costs than terrestrial facilities.

- Technical Reality: Cooling millions of GPUs in space, protecting advanced chips from cosmic radiation, and managing debris are theoretically solvable but practically nightmarish at this scale.

- The Real Threat: A single collision could trigger Kessler syndrome, a cascading debris event that renders entire orbital zones unusable for generations and threatens active satellites and space stations.

- Environmental Impact: Beyond orbital debris, 1 million satellites would dramatically alter Earth's night sky, interfere with radio astronomy, and create unprecedented space traffic management challenges.

- The Bottom Line: Orbital data centers might work technically, but deploying them at Musk's proposed scale would sacrifice the sustainability of low Earth orbit for computational convenience on Earth.

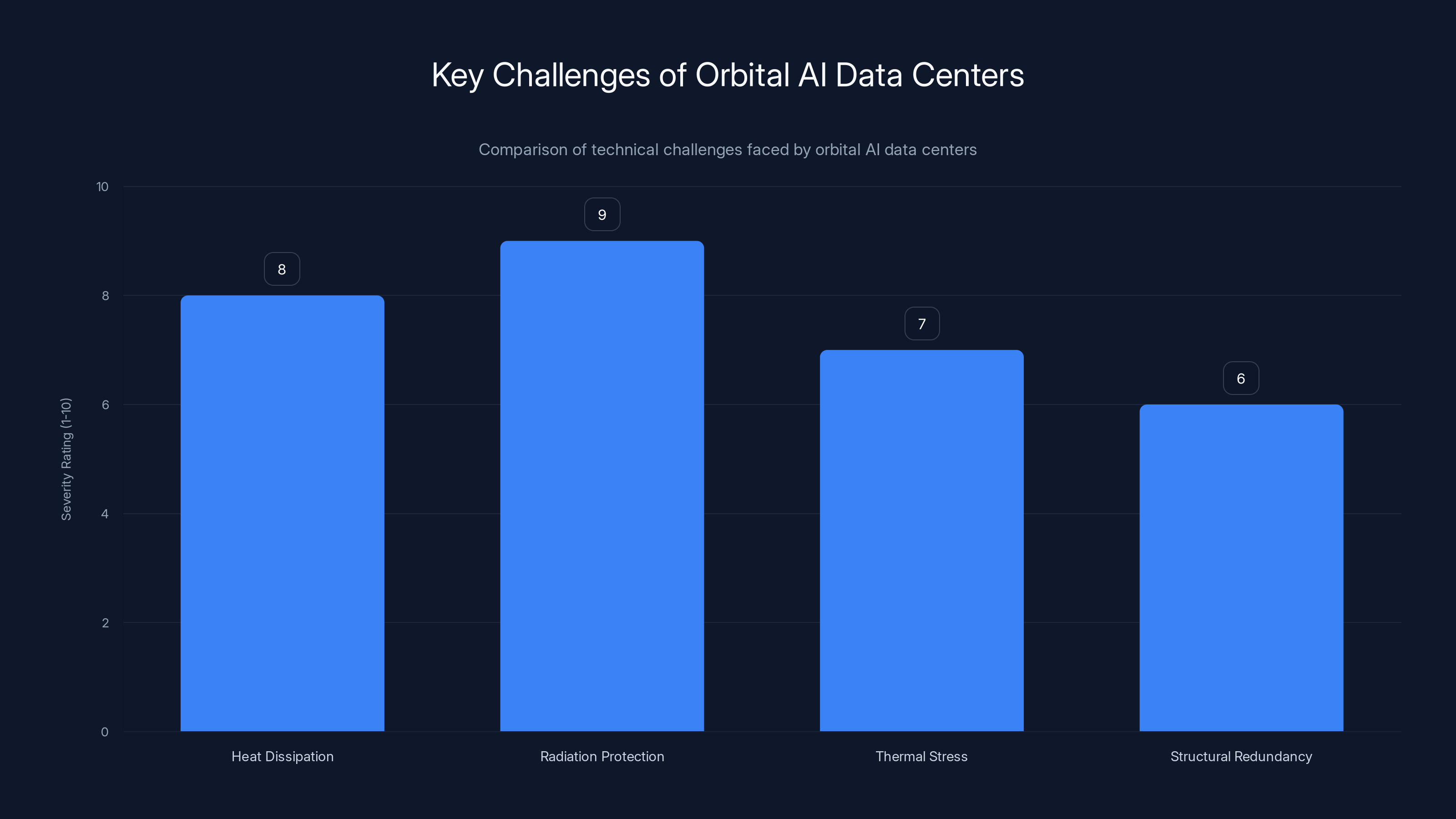

Radiation protection is the most severe challenge for orbital AI data centers, followed closely by heat dissipation issues. Estimated data.

The Core Concept: Why Orbit Looks Attractive for Computing

Let's start with why this idea isn't completely absurd. The economics are genuinely compelling when you do the math.

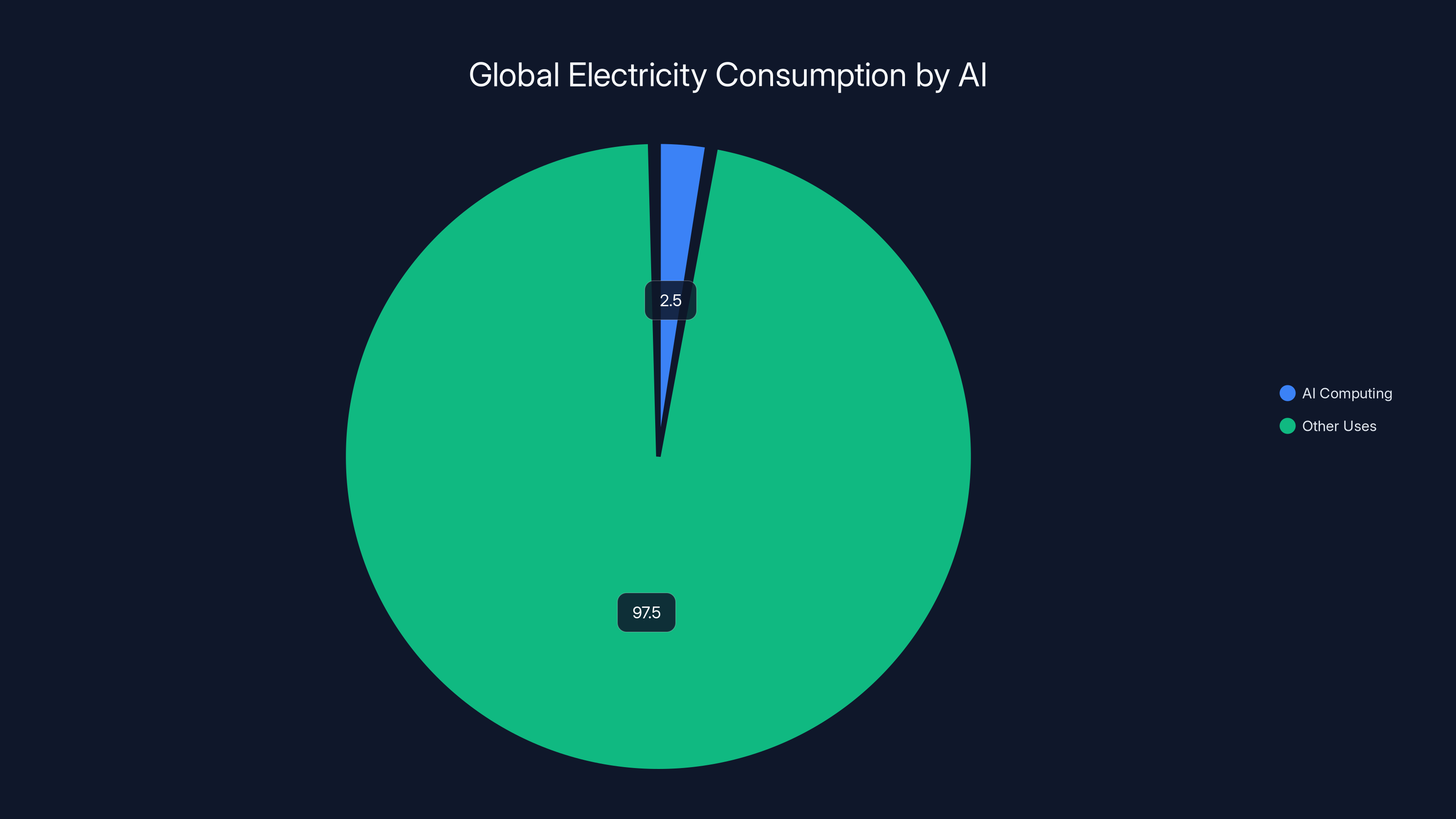

Here on Earth, data centers consume enormous amounts of power. A large facility running thousands of GPUs for AI training can easily pull 100+ megawatts. Recent estimates suggest AI computing already accounts for 2-3% of global electricity consumption, and that number is climbing fast.

Power is expensive. Cooling is expensive. Real estate is expensive. All of these constraints vanish in space.

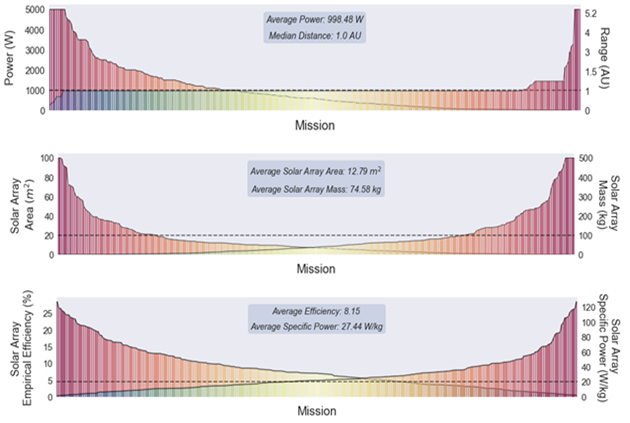

In low Earth orbit, solar panels work differently than on the ground. There's no atmospheric absorption, no seasonal variation, no clouds rolling in at inconvenient times. A spacecraft in sun-synchronous orbit—the type SpaceX proposed—flies along the terminator line separating day and night. This means solar panels receive nearly constant illumination. The calculation is straightforward:

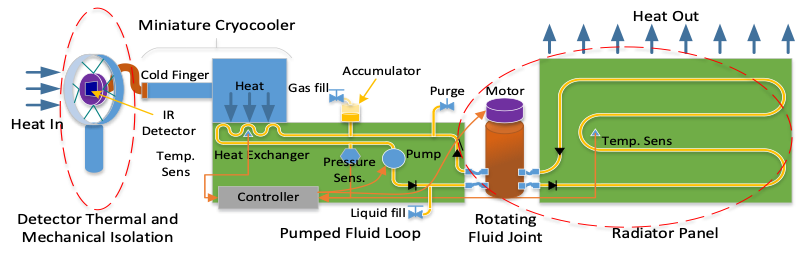

Addressing the elephant in the room: cooling. Space is cold, right? Negative 450 Fahrenheit. Shouldn't that make cooling trivial?

Not exactly. Here's the counterintuitive part that trips up most people who haven't worked in aerospace engineering.

On Earth, we cool data centers using air conditioning, liquid cooling loops, and massive fans that push heat out into the atmosphere. In space, you can't blow air anywhere because, well, there's no air. The only mechanism available is thermal radiation, governed by the Stefan-Boltzmann law:

Where

SpaceX's Starlink satellites manage this on a smaller scale. The V3 model carries about 30 square meters of solar panels and keeps multiple compute elements functioning. But Starlink satellites are processing routing traffic, not running dense matrix multiplications for AI inference or training. The thermal load is completely different.

Let me be direct: the cooling problem is hard but not insurmountable. The radiation resistance problem is the part that actually keeps orbital engineers awake at night.

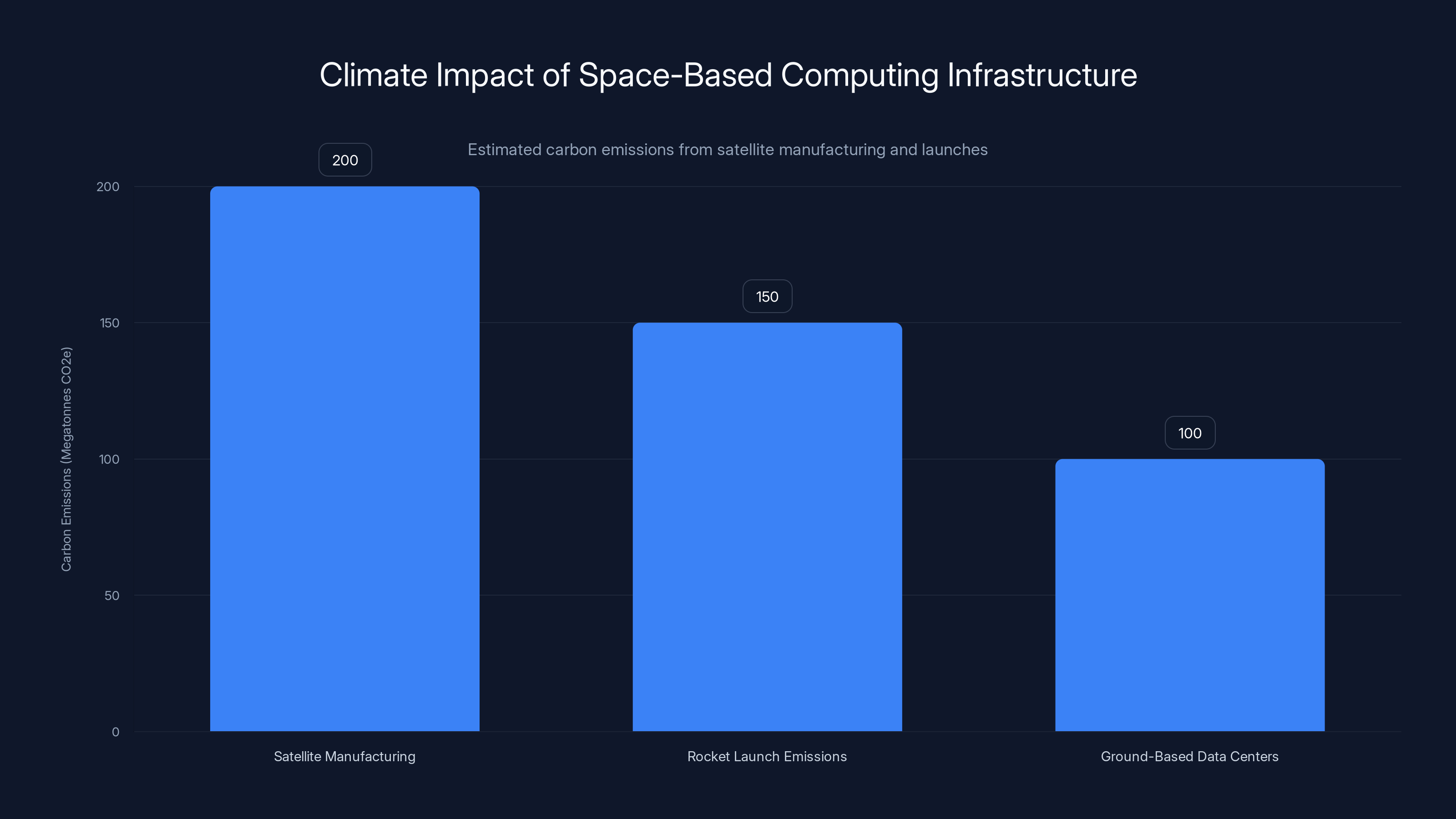

Estimated data shows that the combined carbon emissions from manufacturing and launching satellites could significantly exceed those from ground-based data centers, raising concerns about the climate impact of space-based computing.

The Radiation Problem: Why Advanced Chips Become Unreliable in Space

Modern GPUs are engineering marvels. They pack billions of transistors onto silicon using the smallest possible geometry—currently down to 3 nanometers at the cutting edge. This density is what makes them powerful. It's also what makes them incredibly vulnerable in space.

Cosmic radiation constantly bombards Earth's orbit. Protons, solar wind particles, and heavy ions travel at relativistic speeds. When these particles slam into silicon, they create ionization events that can flip bits in memory and processor registers. A binary one becomes a zero. A calculation gives the wrong answer.

This phenomenon is called a single event upset (SEU), and it's been a known problem since the 1970s. Cosmic ray bit flips have crashed satellites, disrupted telecommunications, and corrupted data throughout space history.

The effect scales with transistor size. Older chips, with larger transistors, require more charge to represent a binary one. Cosmic particles struggle to flip bits. Modern processors, with transistors at 5, 3, or 2 nanometers, store information in incredibly tiny charge states. A single particle can flip multiple bits.

Benjamin Lee, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania's computer science department, explained the physics clearly: "Binary ones and zeroes are about the presence or absence of electrons, and the amount of charge required to represent a 'one' goes down as transistors get smaller and smaller."

When NASA needs radiation tolerance, they use ancient hardware. The Perseverance rover on Mars uses a Power PC 750 processor from the 1990s—not because engineers love retro computing, but because old chips with large transistors simply don't break under radiation the way modern processors do.

Google explored this problem as part of Project Suncatcher, their own investigation into orbital data center feasibility. They took one of their Trillium TPUs and exposed it to a proton beam to simulate orbital radiation. The results were "surprisingly radiation-hard for space applications." That's encouraging. But Google tested one chip, once, in a controlled lab setting.

Deploying millions of GPUs, each packed with hundreds of gigabytes of memory, continuously running at full capacity in an environment saturated with cosmic particles? That's a different magnitude of problem entirely.

Professor Lee raised a critical uncertainty: "We just don't know how resilient GPUs are to radiation at this scale. Even though modern computer architectures can detect and sometimes correct for those errors, having to do that again and again will slow down or add overhead to space-based computation."

There's an optimistic counterargument. AI models are inherently noisy systems. Training modern neural networks deliberately involves injecting random noise to prevent overfitting. Some engineers argue that a certain level of computational errors would be absorbed by the model's existing noise tolerance.

But there's a difference between injected noise during controlled training and random bit flips corrupting a model running inference on real user queries. One is engineered. The other is chaos.

The Thermal and Radiation Solvability Problem

Let's set aside whether these problems are fundamentally solvable—they probably are, eventually, with enough engineering effort and cost.

The real question is simpler: at what cost, and with what reliability?

Kevin Hicks, a former NASA systems engineer who worked on the Curiosity rover, expressed skepticism grounded in experience: "Satellites with the primary goal of processing large amounts of compute requests would generate more heat than pretty much any other type of satellite. Cooling them is theoretically possible but would require a ton of extra work, complexity, and I have doubts about the durability of such a cooling system."

There's a hidden cost buried in that statement. Extra work and complexity mean extra weight. Extra weight means more fuel to lift into orbit. More fuel means exponentially higher launch costs. The economic advantage of cheap space-based power evaporates when you have to spend thousands per kilogram to haul massive radiators, shielding, and redundant cooling systems to orbit.

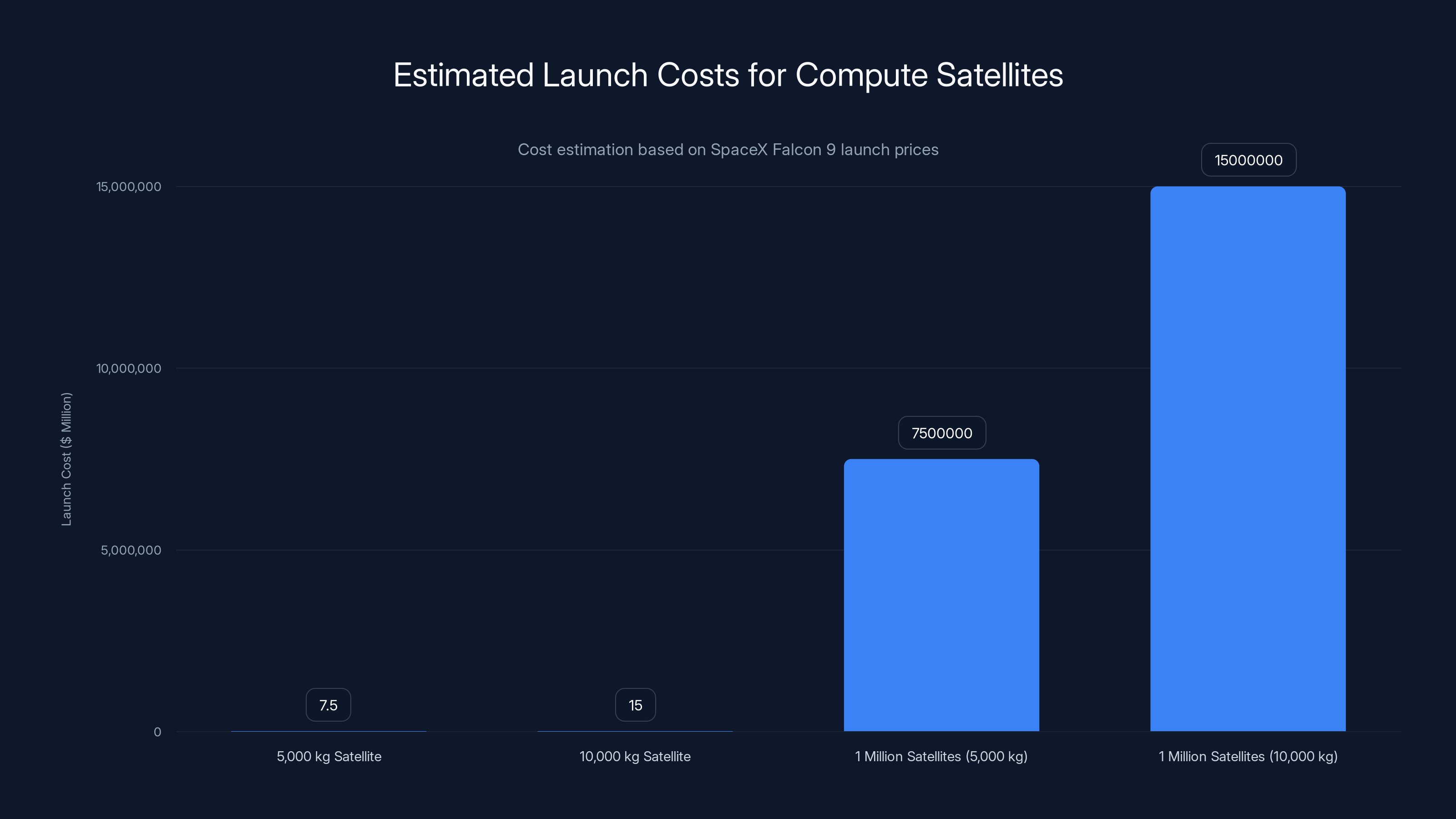

SpaceX's Falcon 9 currently charges roughly

At one million satellites, you're looking at somewhere in the neighborhood of $7.5-15 trillion in launch costs alone, even with Musk's optimistic reusability improvements. That's close to the entire annual GDP of the United States.

So yes, the thermal and radiation problems are probably solvable. But solving them at scale introduces engineering complexity and cost that fundamentally undermines the economic case for orbital computing.

AI computing accounts for an estimated 2-3% of global electricity consumption, highlighting its significant energy demand. Estimated data.

The Kessler Syndrome Problem: Why One Mistake Could Ruin Everything

Here's where the conversation shifts from engineering challenges to existential risk.

In 1978, Donald Kessler, a NASA scientist, published a paper describing a catastrophic scenario: if satellites in orbit start colliding and creating debris, that debris could hit other satellites, creating more debris, triggering an unstoppable cascade of collisions. The result is a cloud of thousands of pieces of shrapnel traveling at thousands of miles per hour, making entire orbital zones unusable for decades.

This phenomenon is called Kessler syndrome, and it's not theoretical. We've already had a preview. In 2009, an inactive Iridium 33 satellite collided with a Russian Cosmos satellite, creating thousands of pieces of trackable debris and countless more pieces too small to track.

Now imagine instead of two satellites colliding once, you have one million satellites sharing the same orbital zones, maneuvering, deorbiting, getting hit by micrometeoroids, and potentially experiencing failures. The probability space for collision events becomes astronomical.

Aaron Boley, an astronomy professor at the University of Alberta, co-authored research on the orbital debris implications of mega-constellations. His findings were unambiguous: deploying satellites at the scale Musk proposed would substantially increase collision risk.

Here's why this matters more than an academic concern. Once Kessler syndrome begins, you can't stop it with phone calls. You can't recall satellites. Debris traveling at 17,500 miles per hour (the typical orbital velocity in LEO) hits like a bullet. A 1-centimeter piece of debris carries kinetic energy equivalent to a grenade. A 10-centimeter piece carries the energy of several kilograms of TNT.

That's roughly the energy of 73 kilograms of TNT. A 1-centimeter piece of trash.

Once a cascade starts, it accelerates. Debris hits satellites, creating more debris, which hits more satellites. Within weeks, you could render entire altitude bands unusable. The International Space Station becomes unreachable. Active satellites for communications, weather monitoring, GPS, and science are destroyed or forced to perform expensive deorbit maneuvers.

The economic impact alone would be staggering. Modern economies depend entirely on satellite infrastructure. GPS for navigation. Communications satellites for internet and phone service. Weather satellites for forecasting. Millions of dollars of space-based infrastructure could become scrap metal.

But the practical challenge goes deeper. With one million satellites to manage, U. S. Space Command and similar tracking organizations would be overwhelmed. They currently track about 35,000 objects in orbit. Adding one million would multiply the tracking challenge by roughly 30 times. That assumes they can even detect all million satellites and maintain tracking updates.

Orbital Crowding: The Coordination Problem

This brings us to a problem that receives less attention than Kessler syndrome but is equally immediate: orbital traffic management.

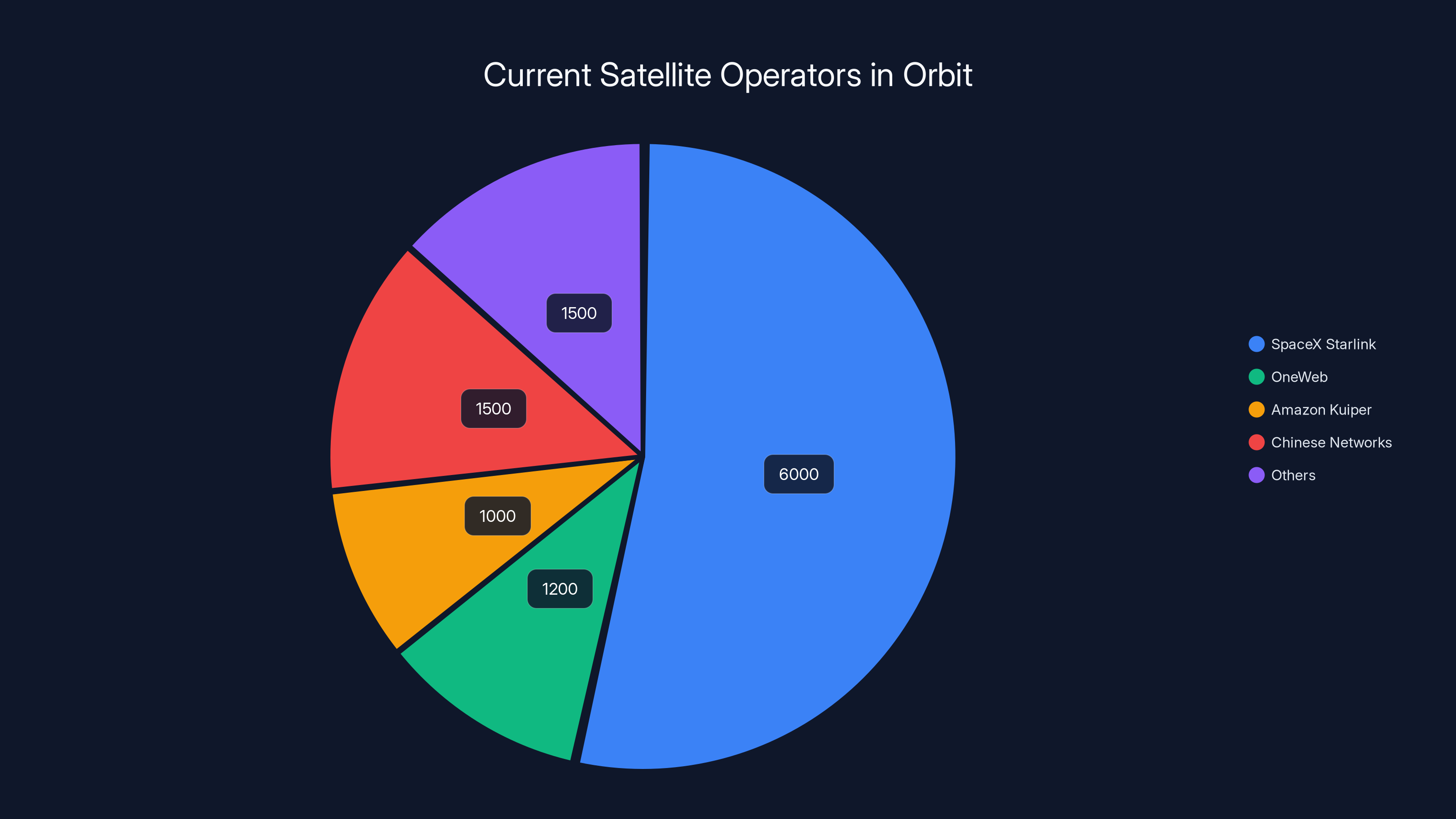

Right now, Starlink operates roughly 6,000 satellites. There are also OneWeb satellites, Amazon's Kuiper constellation in development, Chinese satellite networks, and dozens of smaller operators. Total operational satellites in orbit: roughly 10,000-12,000.

Musk's plan would increase that to roughly 1 million from SpaceX and xAI alone. That's a 100-fold increase in orbital population from one company in a single constellation.

Managing collision avoidance becomes a real-time computational problem. Every satellite needs to know where every other satellite is, calculate trajectories, predict near-approaches, and execute course corrections when necessary. The computational overhead alone could consume significant power—defeating one of the core efficiency arguments for orbital data centers.

More practically, it creates a new coordination problem. Space is international territory, but there's no global space traffic control authority. Each nation operates its own tracking and coordination systems. Integrating a million new satellites into existing tracking infrastructure would require unprecedented international cooperation.

The International Telecommunication Union (ITU) handles frequency coordination for satellites, but there's no comparable body for orbital traffic management. The assumption is that operators will coordinate directly. One million satellites make that assumption break down completely.

The cost of deploying a single orbital satellite is

Environmental Impact Beyond Orbit: Light Pollution and Radio Interference

Here's something the calculations don't capture: what happens when you flood Earth's night sky with a million reflective objects.

Starlink has already created a massive problem for astronomy. Bright satellites crossing the night sky during observations blind telescopes. The upcoming Vera C. Rubin Observatory, designed to map the universe and identify near-Earth hazards, could have 20% of its images contaminated by bright satellite trails from existing constellations. Adding one million more satellites would essentially destroy ground-based optical astronomy as it currently exists.

Robert Massey, the associate director of the Royal Astronomical Society, has been vocal about this: satellite constellations at the scale Musk proposes would render astronomical observation nearly impossible.

Beyond visual light, radio astronomers face interference. One million satellites transmitting laser and microwave signals to maintain constellation coherence creates a noisy radio environment. Detecting fast radio bursts, searching for extraterrestrial signals, mapping the universe at radio frequencies—all become exponentially harder.

There's also the purely aesthetic argument. Human culture has oriented around the night sky since the dawn of consciousness. A sky filled with moving dots of light isn't a minor aesthetic loss. It's a fundamental change to human experience.

The Deorbiting Problem: What Happens When Satellites Die

Starlink satellites are designed with a five-year lifespan. In low Earth orbit, atmospheric drag gradually brings satellites down. Eventually, they reenter Earth's atmosphere and burn up.

For Starlink, that's relatively manageable. For one million compute satellites, it's a nightmare.

Every five years, you'd need to launch one million new satellites to replace those that reached end-of-life. That's 200,000 launches per year using current rocket efficiency. That's roughly 550 launches per day, every single day, forever.

For context, SpaceX launched about 100 Falcon 9 rockets in 2024. They'd need to increase launch cadence by 5,500 percent.

Some satellites will fail prematurely. Some will experience degraded performance requiring replacement. Some will develop bugs that need patching—now you need ways to service satellites in orbit, adding complexity and cost.

Meanwhile, you have hundreds of thousands of defunct satellites still in orbit, becoming uncontrolled debris, increasing collision probability, and contributing to Kessler syndrome risk.

There's also the practical question: where do you build one million satellites? The manufacturing capacity doesn't exist. You'd need factories operating on a scale unprecedented in human history just to produce the hardware.

Estimated launch costs for compute satellites range from

The Climate Impact of Space-Based Computing Infrastructure

This is where the argument gets genuinely complicated. Orbital data centers are being proposed partly to address climate concerns about energy consumption. But achieving the goal of orbital computing creates its own climate impacts that are largely ignored.

Manufacturing satellites involves mining, refining metals, producing semiconductors, and assembling components. The carbon footprint of a single satellite is significant. Multiply that by one million, and you're looking at a manufacturing carbon cost measured in megatonnes of CO2 equivalent.

Then there's the launch cost. Rocket engines operate by burning fuel (usually kerosene) and liquid oxygen or solid rocket propellant. Each kilogram lifted to orbit requires significant fuel, which burns in the upper atmosphere. The resulting emissions—not just CO2, but soot, nitrogen oxides, and water vapor—have complex climate effects that scientists are still characterizing.

Research on rocket launch climate impacts suggests each launch contributes meaningful warming, and at scale, the cumulative effect could exceed any climate benefits achieved by reducing ground-based data center energy consumption.

You're essentially trading ground-based energy consumption (increasingly renewable powered) for space-based infrastructure with massive embedded carbon costs and long-term climate implications.

Let's do a rough calculation. If one million satellites weigh 5 tonnes each, that's 5 million tonnes of material requiring launch to orbit. At current rocket efficiency, that requires roughly 7-8 million tonnes of rocket fuel (depending on engine efficiency). Burning rocket fuel produces roughly 3.15 tonnes of CO2 per tonne of fuel burned. So you're looking at approximately 22-25 million tonnes of CO2 just from the initial deployment.

For comparison, the entire data center industry produces roughly 1% of global greenhouse gas emissions, or about 500 million tonnes annually. Orbital infrastructure could represent 4-5% of annual data center emissions just for the initial deployment.

Then add replacement satellites every five years, and you're sustaining massive launch rates indefinitely.

The Economics Reality Check: Does This Actually Pencil Out

Let's strip away the vision and do the math.

A single compute satellite for orbital data centers might cost

Total cost per satellite: roughly $3-4 billion per satellite over five years of operation.

Return on investment requires that the satellite generates more than $600-800 million annually in compute revenue to break even. For a single satellite.

Now multiply that across one million satellites, and you're talking about $3-4 trillion in capital investment, plus ongoing operational costs in the hundreds of billions per year.

For perspective, the entire current data center industry—ground-based, terrestrial, proven, with existing demand—generates roughly $150-200 billion in annual revenue globally. Creating an orbital equivalent would require more than a decade of global AI compute growth at current rates.

SpaceX Starlink dominates current orbital satellite operations with an estimated 6,000 satellites, highlighting the potential for increased orbital crowding. (Estimated data)

Are There Safer Alternatives to Orbital Computing

Here's the thing people often miss: the problems being solved by orbital data centers could be addressed terrestrially with far less risk.

Renewable energy is becoming cheaper and more abundant. Solar and wind farms can power data centers directly. The challenge isn't electricity cost—it's matching generation to demand and transmission to population centers where that computing power is used.

That's a logistics and infrastructure problem, not a physics problem. Solvable through boring, unglamorous engineering: grid modernization, transmission system upgrades, energy storage, demand shifting. No satellites required.

More efficient algorithms and chip architecture also reduce power consumption. Transformer-based architectures, which power modern AI, continue to improve in efficiency. Specialized hardware—tensor processors, quantum-inspired processors—push toward better performance-per-watt.

Focusing computational power in fewer, larger facilities with better thermal management and redundancy is more efficient than distributing it across a million satellites subject to radiation and requiring continuous replacement.

Anthropic, OpenAI, and other major AI labs are building ground-based data centers at unprecedented scales with cutting-edge efficiency. These aren't slow solutions. They're happening now.

The Regulatory and Governance Vacuum

Here's where the discussion gets into messy reality.

There's no international body with authority to regulate orbital mega-constellations. The Outer Space Treaty of 1967 established that no nation can claim ownership of space, but it's silent on constellation sizes, debris mitigation, and traffic management.

Nations can propose launches to the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) for frequency coordination, but approval is largely automatic. There's no authority that can say "no, that's too many satellites."

The United States can regulate SpaceX domestically through the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) and the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), but regulatory oversight is often permissive when dealing with commercial innovation.

Meanwhile, other nations see the precedent. If China or Russia decide to launch competing mega-constellations, the race toward orbital saturation accelerates unchecked.

This is a classic tragedy of the commons scenario. Individually rational decisions (launch satellites, generate value) create collectively catastrophic outcomes (orbital debris, collision cascades, dead zones).

Expert Consensus: Skepticism Dominates

When you talk to actual orbital engineers, astronomers, and debris specialists, the consensus emerges quickly.

No one thinks the idea is impossible. Yes, the thermal problems are solvable. Yes, you could protect chips from radiation with enough engineering. Yes, technically, you could launch one million satellites.

But "technically possible" and "strategically wise" are different questions. And when asked whether this is wise, experts universally express concern.

NASA's Astrobiology Institute has flagged mega-constellation concerns. The European Space Agency raised collision risk in official statements. Academic researchers who study orbital mechanics publish papers documenting the danger.

None of this prevents Musk or other companies from proceeding. Legal authority is ambiguous. Regulatory oversight is limited. But the signals are clear: this path leads toward collective risk.

What Should Actually Happen: A Framework for Responsible Innovation

If orbital computing has genuine merit—and there may be narrow use cases where it does—then deploying it responsibly requires:

1. Binding International Agreements

Create a treaty establishing limits on orbital mega-constellations, similar to nuclear arms control. Set maximum constellation sizes, spacing requirements, and debris mitigation standards. Make compliance verifiable and sanctions meaningful.

2. Real-Time Debris Tracking

Invest in global tracking systems capable of monitoring millions of objects in real-time. Current systems are adequate for thousands of satellites. Scaling to millions requires new sensor networks, computational capacity, and international data-sharing protocols.

3. Collision Avoidance Standards

Establish mandatory collision avoidance systems, automated or autonomous, that execute evasive maneuvers before close approaches. Currently, some operators coordinate manually. At scale, that's unworkable.

4. Deorbiting Requirements

Make end-of-life deorbiting mandatory. Require all satellites to carry deorbiting fuel and demonstrate capability before launch. Penalize operators who leave dead satellites in orbit.

5. Environmental Impact Assessments

Require comprehensive environmental impact reviews before mega-constellation deployment, including cumulative effects on astronomy, radio frequencies, atmospheric chemistry, and climate.

6. Open Questions Resolved First

Before deploying one million satellites, answer the open research questions:

- Actual radiation hardness of advanced GPUs at scale

- Thermal management durability under long-term operation

- Collision probability models with realistic failure rates

- Atmospheric effects of sustained high-cadence launch programs

The Broader Lesson: Ambition Without Wisdom Is Dangerous

This conversation isn't really about whether orbital data centers could work. It's about the difference between technological possibility and strategic wisdom.

We can do things we shouldn't do. Humans are good at building things. We're worse at understanding systemic consequences at scale.

Orbital mega-constellations are the latest example of that gap. The ambition is genuine. The potential efficiency gains are real. But deploying them at scale would trade solved problems on Earth for unsolved problems in space—and those space problems affect everyone, whether they benefit from orbital computing or not.

Musk's reputation suggests he moves fast and takes risks. That works for electric cars and reusable rockets. It's dangerous when the downside risk is making Earth orbit unusable for everyone, including future space exploration that might actually matter.

The challenge for regulators and international bodies is establishing guardrails before the race to populate orbit becomes irreversible.

FAQ

What is an orbital AI data center?

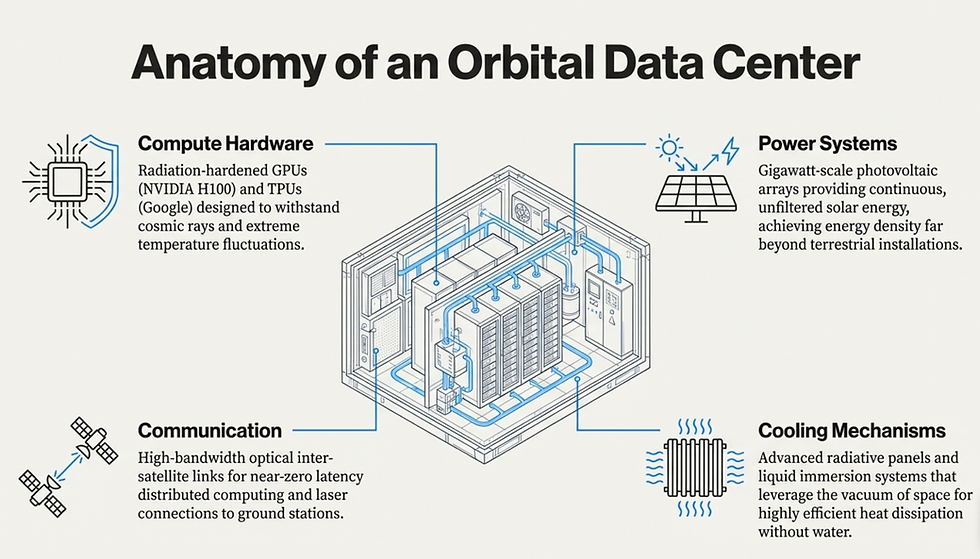

An orbital AI data center is a satellite equipped with powerful computing hardware (GPUs or specialized chips) designed to perform artificial intelligence inference or training tasks while in orbit. The concept leverages the efficiency advantages of solar power in space and eliminates cooling challenges associated with ground-based facilities, though it introduces new engineering and debris challenges.

How would orbital AI data centers actually work in practice?

The proposed system would deploy satellites in clusters at altitudes between 500 and 2,000 kilometers, equipped with large solar panel arrays and computing hardware. These satellites would communicate with each other and with ground stations using laser links and microwave signals. Ground users would send compute requests up to the constellation, which processes the data and returns results, all theoretically faster and cheaper than terrestrial data centers due to superior solar efficiency.

What are the main technical challenges with orbital compute?

The primary challenges include dissipating excess heat from densely packed processors in near-vacuum conditions (radiation is the only cooling mechanism), protecting advanced semiconductors from cosmic radiation that causes bit errors, managing thermal stress from varying sunlight exposure, and providing the enormous structural and thermal redundancy required for reliable long-duration operation in space.

Why is Kessler syndrome such a big concern for mega-constellations?

Kessler syndrome occurs when satellite collisions create debris that collides with other satellites, creating more debris in a cascade effect. Once triggered, it's unstoppable. One million orbital satellites dramatically increase collision probability. A single cascade event could render large swaths of low Earth orbit unusable for decades, threatening all satellite infrastructure including communications, GPS, weather monitoring, and the International Space Station.

How does radiation affect satellite computing in orbit?

Cosmic radiation bombards Earth orbit constantly, causing bit flips in semiconductor memory and processors. Modern GPUs use tiny transistors vulnerable to single-particle events that flip bits. While AI models tolerate some computational errors, the scale of errors from unshielded advanced chips in space radiation would degrade reliability significantly, requiring expensive error-correction mechanisms that consume power and reduce efficiency.

What would be the environmental impact beyond orbital debris?

Beyond collision risk, one million satellites would dramatically reduce ground-based optical and radio astronomy capabilities by creating light pollution and radio interference, destroy the aesthetic night sky experience, and the massive launch rate required for initial deployment and satellite replacement would inject billions of tonnes of emissions into the atmosphere over time, potentially offsetting any climate benefits from efficient space-based computing.

Why doesn't the economics pencil out for orbital data centers?

Developing, building, launching, and operating a satellite requires roughly

Are there better alternatives to orbital data centers?

Yes. Renewable energy continues becoming cheaper and more abundant. Terrestrial data center efficiency improves through better cooling systems, specialized chips, and algorithmic improvements. Grid modernization and energy storage solve the matching problem between generation and demand without requiring satellite infrastructure. These approaches avoid the systemic risks and environmental costs of orbital deployment.

What regulatory authority oversees orbital mega-constellations?

No single international authority has clear regulatory control over constellation size or collision risk. The Outer Space Treaty establishes that space isn't owned by nations, but contains no provisions for constellation limits. The International Telecommunication Union coordinates radio frequencies, but has no authority over debris or traffic management. Individual nations can regulate launches within their borders, but lack incentive to restrict competitive companies.

What would responsible orbital computing deployment require?

Responsible deployment would require international treaties limiting constellation sizes, mandatory collision avoidance systems, binding deorbiting requirements, comprehensive environmental impact assessments addressing astronomy and atmospheric effects, real-time global debris tracking systems, and resolution of fundamental questions about radiation hardness and thermal durability before deployment of even partial constellations.

Conclusion: Progress Requires Wisdom, Not Just Ambition

Elon Musk's ability to accomplish difficult technical feats is well-documented. SpaceX proved that reusable rockets work when conventional wisdom said they didn't. Tesla accelerated the electric vehicle timeline by a decade. xAI is pushing large language models forward at a furious pace.

But not every technically achievable goal should be pursued at maximum scale. Sometimes the constraints preventing implementation exist for good reasons.

Orbital AI data centers might work technically. The cooling problems, radiation challenges, and operational complexity are hard but arguably solvable with enough engineering effort and capital. Dozens of researchers would be delighted to attack these problems for billions in funding.

But solving them doesn't mean the project makes sense.

Low Earth orbit is a shared resource. It's not infinitely large. Its utility depends on a baseline of safety, sustainability, and international coordination that a mega-constellation of one million satellites would shatter. The collision risk alone, even if carefully managed, represents an irreversible environmental hazard to global infrastructure that depends on space-based services.

Meanwhile, the economic case crumbles under scrutiny. The investment required to build, launch, and operate one million satellites exceeds the total global demand for computing power at realistic price points. Unless efficiency gains materially exceed current projections—possible but speculative—the fundamental math doesn't work.

And there's the uncomfortable truth that terrestrial solutions already exist. Solar farms, wind farms, geothermal facilities, next-generation nuclear power, grid modernization, algorithmic improvements, and architectural innovation are all proven paths to more efficient computing. They lack the science-fiction appeal of satellite megaconstellations. They lack the venture capital narrative of a billion-dollar disruption. But they work, they're deployable now, and they don't risk cascading orbital catastrophes.

Sometimes the most ambitious thing we can do is choose not to do something just because we can. That's not risk-aversion. It's wisdom.

Regulators, international bodies, and the broader space community need to establish that precedent now, before the race toward orbital saturation becomes unstoppable. SpaceX and xAI will deploy what regulators allow. Once mega-constellations become normalized, international coordination becomes exponentially harder. The time to establish guardrails is before deployment begins at scale, not after we've created an unsustainable orbital environment.

The choice isn't between orbital computing and innovation. It's between pursuing innovation responsibly and chasing technological possibility regardless of consequence. The first path requires accepting constraints. The second path leads to shared disaster.

Given what's at stake, choosing wisdom seems like the genuinely ambitious path forward.

Key Takeaways

- SpaceX and xAI's proposal to deploy 1 million orbital AI satellites is technically feasible but economically questionable and environmentally catastrophic at proposed scale

- Thermal cooling in near-vacuum and cosmic radiation protection of advanced GPUs present solvable but increasingly expensive engineering challenges that erode the economic case

- Kessler syndrome risk from orbital debris could render critical satellite infrastructure unusable for decades if a cascade collision event is triggered

- Alternative terrestrial solutions using renewable energy, improved algorithms, and grid modernization already exist and pose far fewer systemic risks

- International governance vacuum leaves no regulatory body capable of preventing orbital mega-constellation deployment despite known environmental and safety concerns

Related Articles

- Moonbase Alpha: Musk's Bold Vision for AI and Space Convergence [2025]

- Elon Musk's Moon Satellite Catapult: The Lunar Factory Plan [2025]

- xAI's Mass Exodus: What Musk's Spin Can't Hide [2025]

- The xAI Mass Exodus: What Musk's Departures Really Mean [2025]

- xAI's Interplanetary Vision: Musk's Bold AI Strategy Revealed [2025]

- xAI Founding Team Exodus: Why Half Are Leaving [2025]

![Orbital AI Data Centers: Technical Promise vs. Catastrophic Risk [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/orbital-ai-data-centers-technical-promise-vs-catastrophic-ri/image-1-1771522893546.jpg)