The Fusion Economics Problem Nobody's Solved Yet

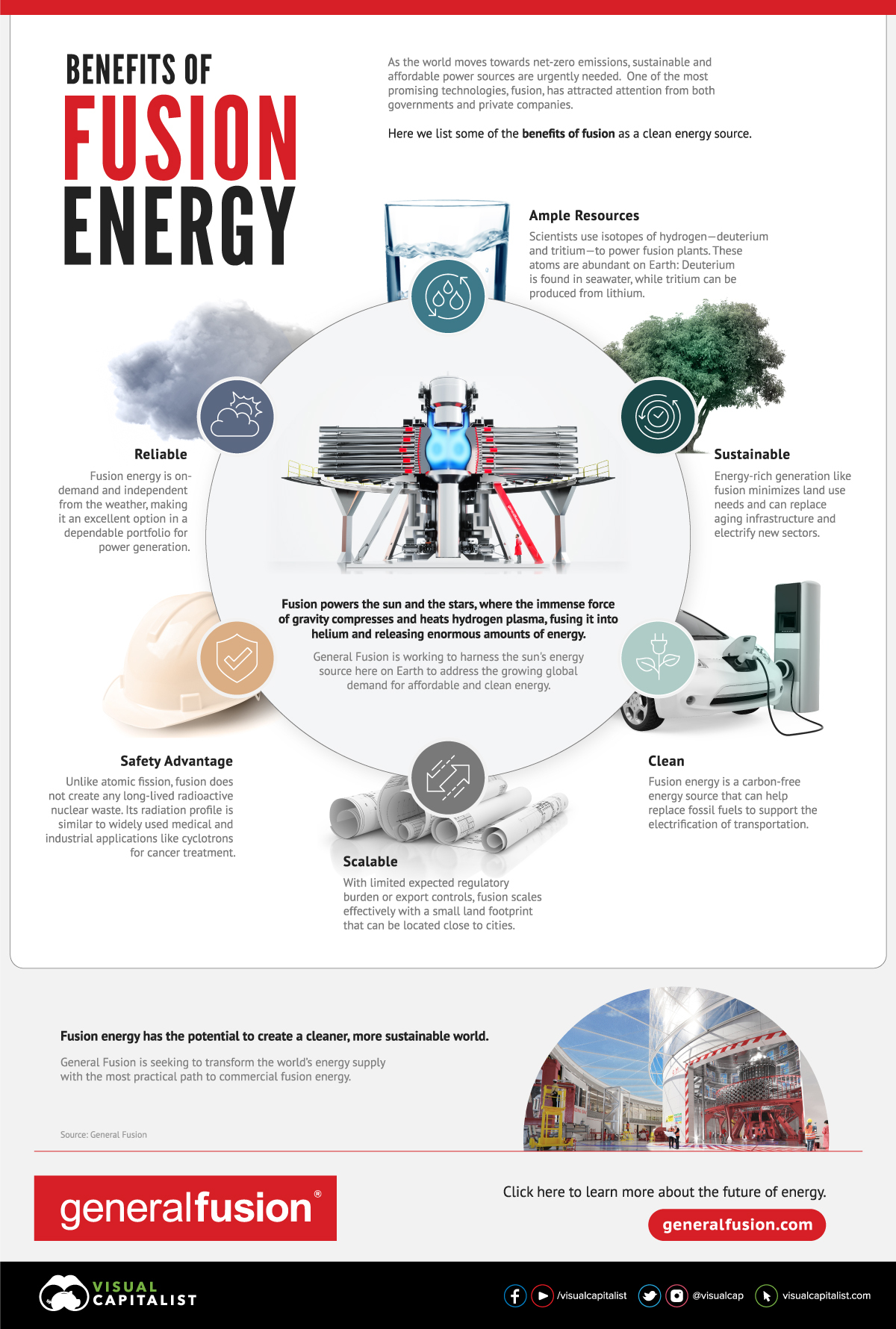

Fusion power is tantalizing. Imagine massive amounts of electricity generated 24/7, no carbon emissions, no meltdown risks. It sounds perfect. But there's a brutal economic reality that keeps fusion startups up at night: the cost to initiate the fusion reaction can't exceed what you'll earn selling the electricity.

That's it. That's the entire puzzle.

Commonwealth Fusion Systems thinks they've cracked it, and they're betting hundreds of millions of dollars on it. They're building a reactor that costs several hundred million dollars upfront, but they won't flip the switch until next year. So the question remains unanswered. Other companies are more optimistic about their timeline, particularly startups founded in recent years that believe they can build commercial fusion plants cheaper and faster.

Pacific Fusion just announced something interesting. They completed experiments at Sandia National Laboratory's Z Machine that could eliminate some of the most expensive components from their approach. The results matter because they reveal a path to removing a system that costs north of $100 million.

Here's what makes this worth paying attention to: most fusion companies haven't demonstrated anything beyond simulations and small-scale experiments. Pacific Fusion just ran real hardware tests at one of the most respected fusion research facilities in the world. And the results worked.

Understanding Pulser-Driven Inertial Confinement Fusion

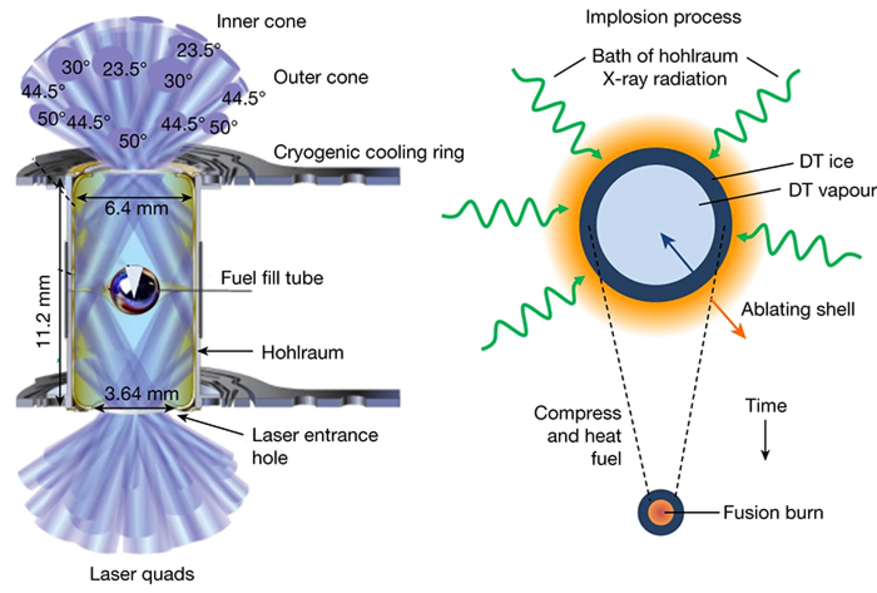

Pacific Fusion isn't inventing fusion from scratch. They're adapting an approach that's been proven in laboratories: inertial confinement fusion, or ICF. The concept is deceptively simple—compress fuel so densely that atoms slam together and release energy. But simplicity ends there.

Inertial confinement works on a principle that sounds like science fiction: squeeze a pellet the size of a pencil eraser in less than 100 billionths of a second. That's not exaggeration. The compression needs to happen so fast and so completely that the atoms inside have nowhere to go except toward each other. When they collide, they fuse, releasing energy. That energy comes from Einstein's mass-energy equivalence equation:

Where even tiny amounts of mass convert to enormous amounts of energy. A single gram of matter converted completely would equal roughly 20 kilotons of TNT—the size of the Hiroshima bomb.

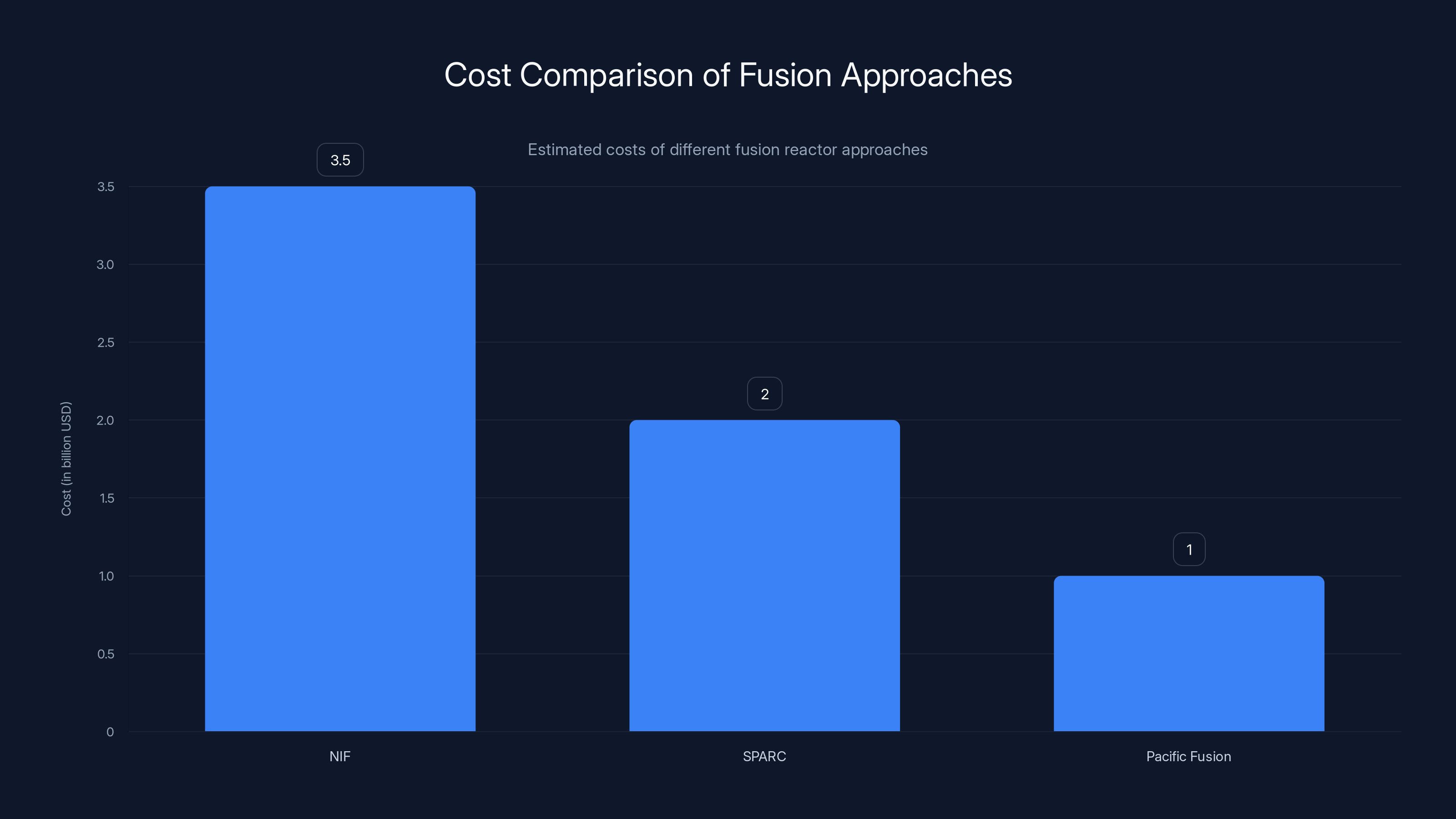

The National Ignition Facility proved this works, but they use lasers. Specifically, 192 laser beams focused on a target smaller than a human cell. The approach delivers incredible precision, but those 192 beams cost billions of dollars, occupy an entire building, and require armies of physicists to operate. That's not exactly a business model.

Pacific Fusion wants to use electricity instead.

Think of it differently. Take a metal cylinder, place the fuel pellet inside, then hit it with a massive electrical pulse. That pulse creates a magnetic field that squeezes the cylinder, which compresses the fuel inside. The speed matters enormously. Keith Le Chien, Pacific Fusion's co-founder and CTO, explained the core physics simply: the faster the compression, the hotter it gets. Temperature is what drives fusion. Get it hot enough, and atoms stop acting like separate particles and start acting like a unified plasma where fusion becomes inevitable.

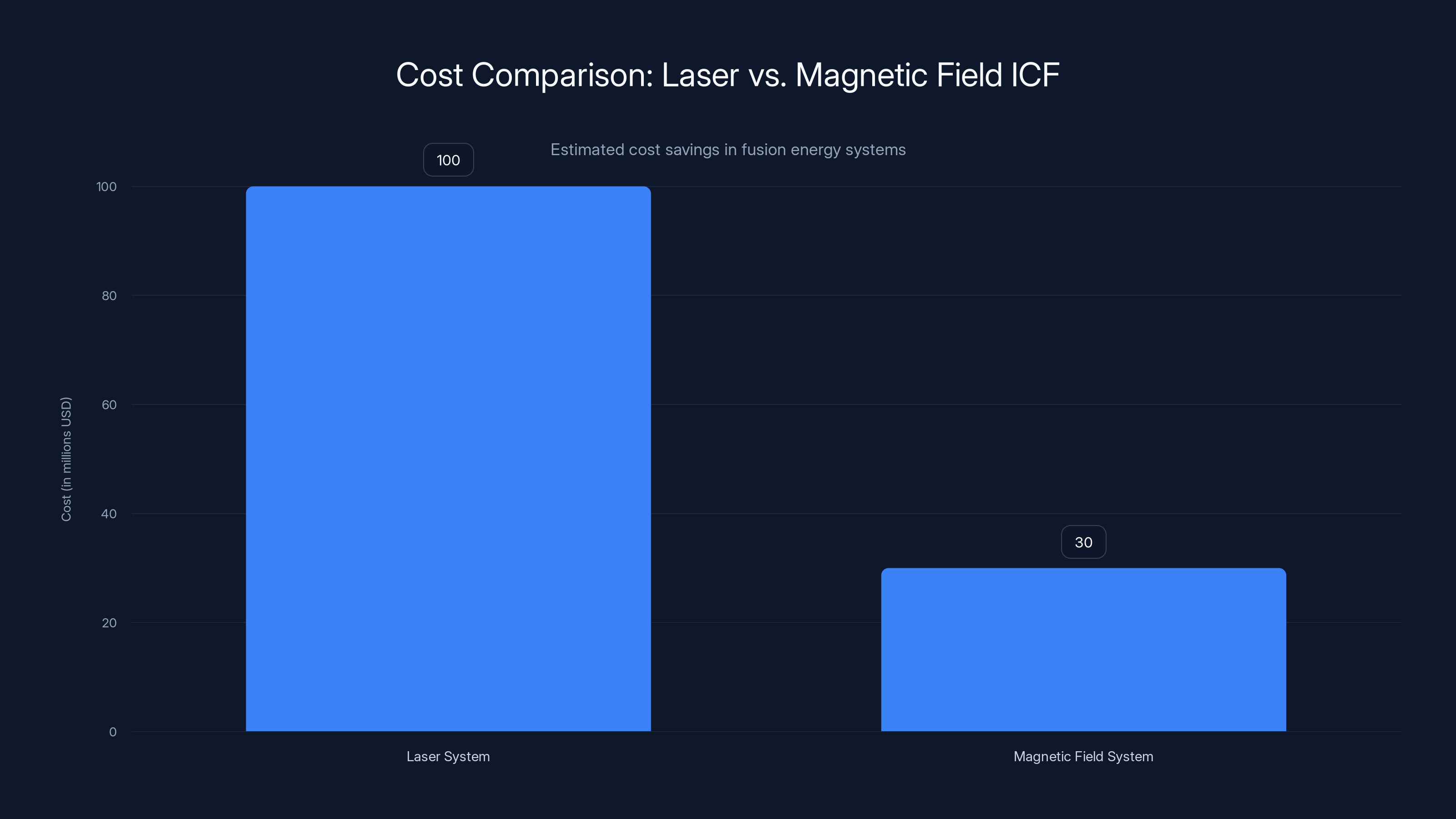

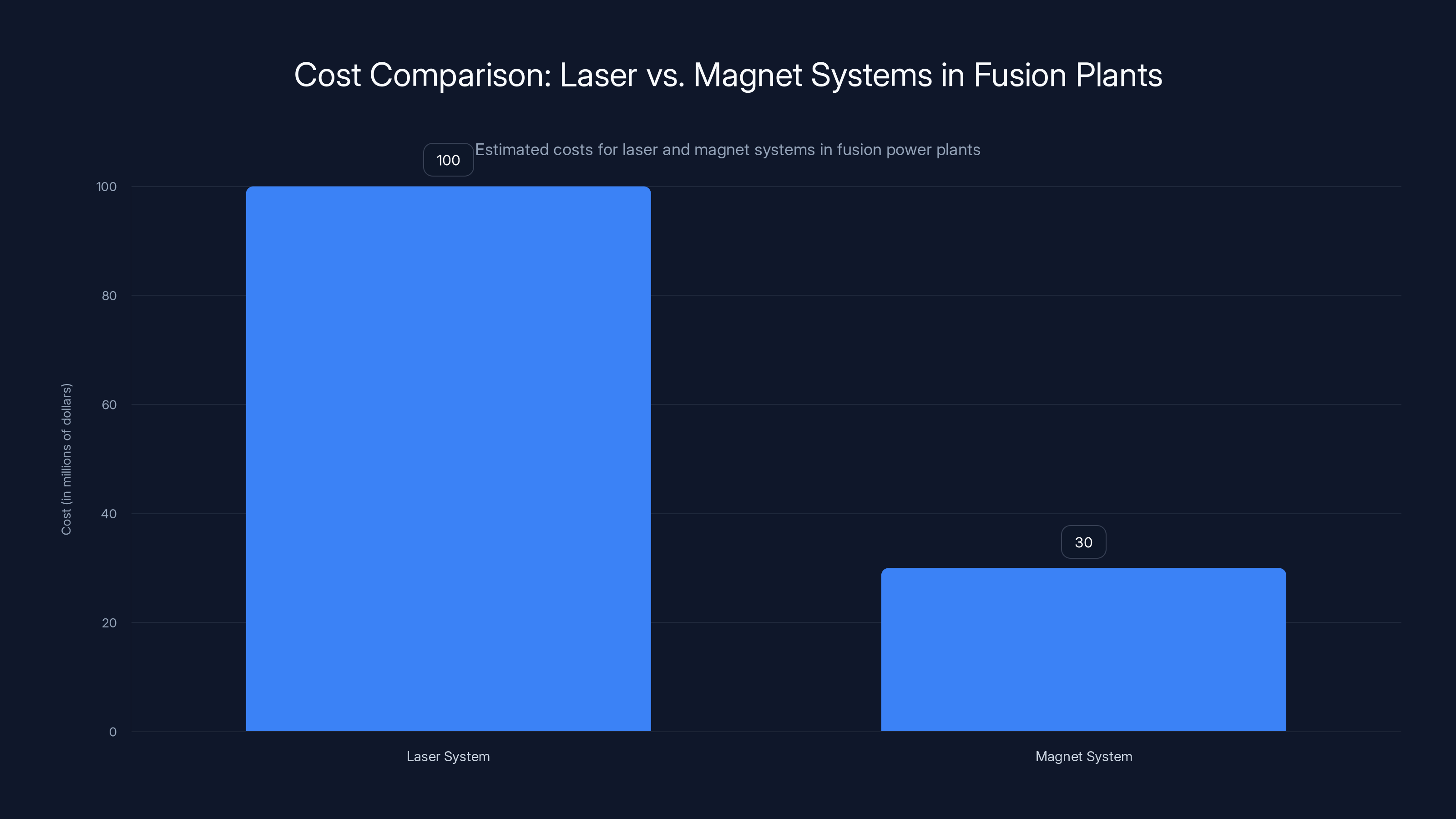

Estimated data shows that magnetic field systems can reduce costs by up to 70% compared to traditional laser systems in fusion energy setups.

The Heating Problem Nobody Wanted to Solve

Here's where the actual engineering challenge emerges. Compressing a fuel pellet to fusion temperatures isn't straightforward. The compression alone doesn't generate enough heat. You need a head start.

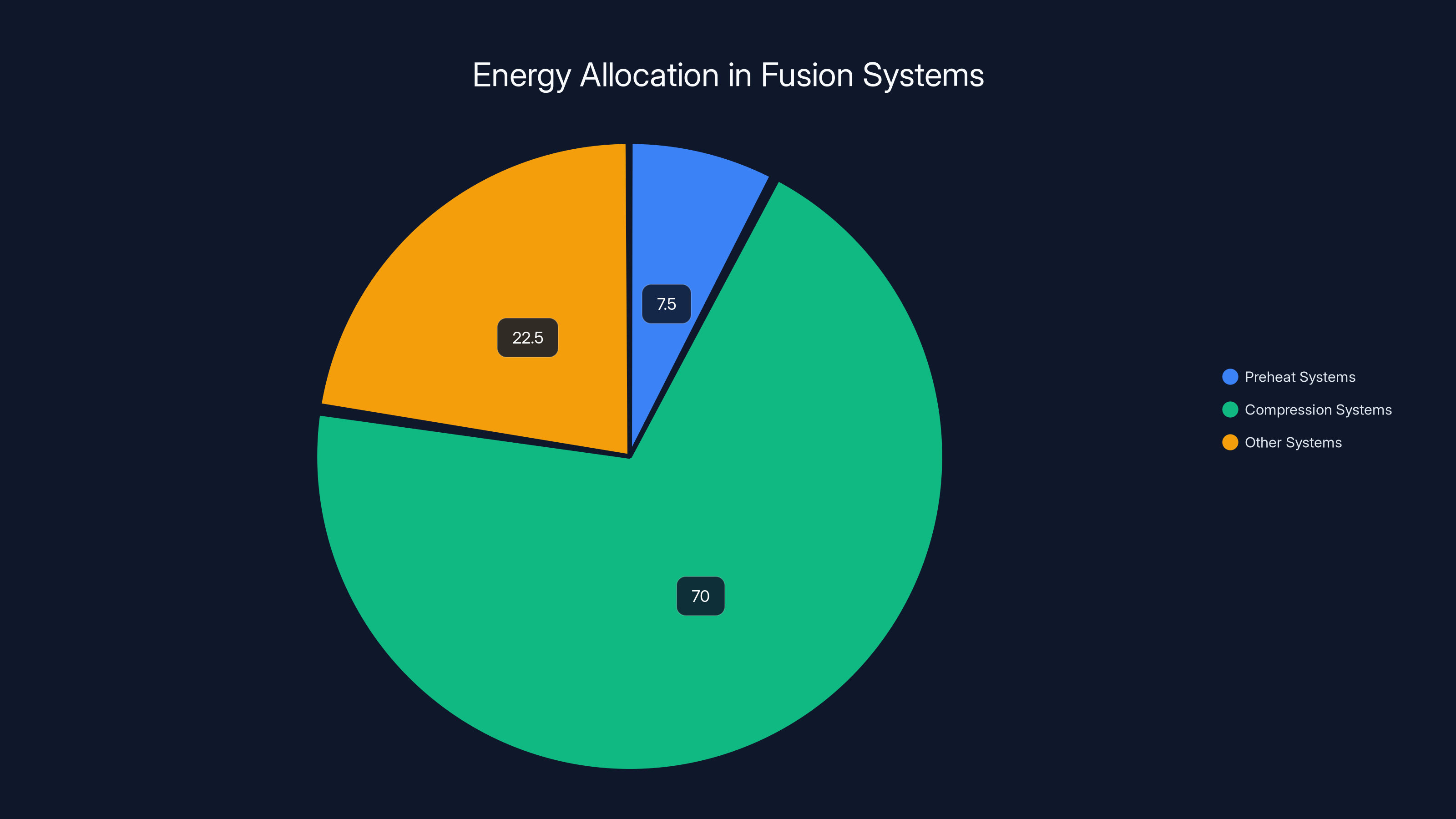

For decades, fusion researchers have used a two-step process. Step one: use lasers or other energy sources to preheat the fuel pellet to millions of degrees. Step two: compress it even further, reaching the billions of degrees needed for fusion. This preheat step typically requires 5% to 10% of the total energy in the system.

Five to 10 percent sounds small. It's not. When you're building a massive pulsed power machine that costs hundreds of millions of dollars, that 5% to 10% translates directly to major subsystems. You need dedicated laser arrays or magnetic coils just for preheating. You need the infrastructure to support them. You need people trained to maintain them. You need redundancy for reliability.

Most fusion companies have accepted this as inevitable. It's just how the physics works, they figured. You need a preheat system, so you build one, you optimize it, you hope it doesn't break.

Pacific Fusion asked a different question: what if we didn't?

The Breakthrough: Controlled Magnetic Field Leakage

The experiments at Sandia revealed something elegant. Pacific Fusion didn't need to eliminate preheating entirely. They just needed to rethink how it happens.

Instead of dedicated preheat systems, they let the main compression system do double duty. Here's the clever part: the cylinder that contains the fuel pellet was traditionally designed to be perfectly sealed. Not anymore. Pacific Fusion modified the cylinder design so that some of the magnetic field from the main compression pulse would leak through and into the fuel before the main compression started.

Imagine a container with tiny intentional gaps. When you apply the main magnetic field, a little bit seeps through the gaps first, heating the fuel slightly. Then, once that seepage is complete, the full force of the magnetic field compresses the cylinder and the fuel inside. It's like getting a running start without needing a separate system to provide it.

The key innovation wasn't some exotic new physics. It was precision manufacturing of the cylinder itself. Pacific Fusion adjusted the thickness of the aluminum wrapping around the fuel pellet. Change the aluminum thickness, and you change how much magnetic field leaks through. It's a tuning knob, essentially.

Le Chien emphasized something important: this doesn't require exotic manufacturing tolerances. The precision needed is equivalent to what's used for .22 caliber bullet casings. That process has been refined and perfected over 100 years. It's not novel. It's not expensive. It's mass-producible.

The energy cost of allowing this magnetic field leakage? Essentially zero. Le Chien described it as "a very, very, very small fraction of the overall energy in the system, so it's effectively unnoticeable." Less than 1% of total system energy. Probably closer to 0.1%.

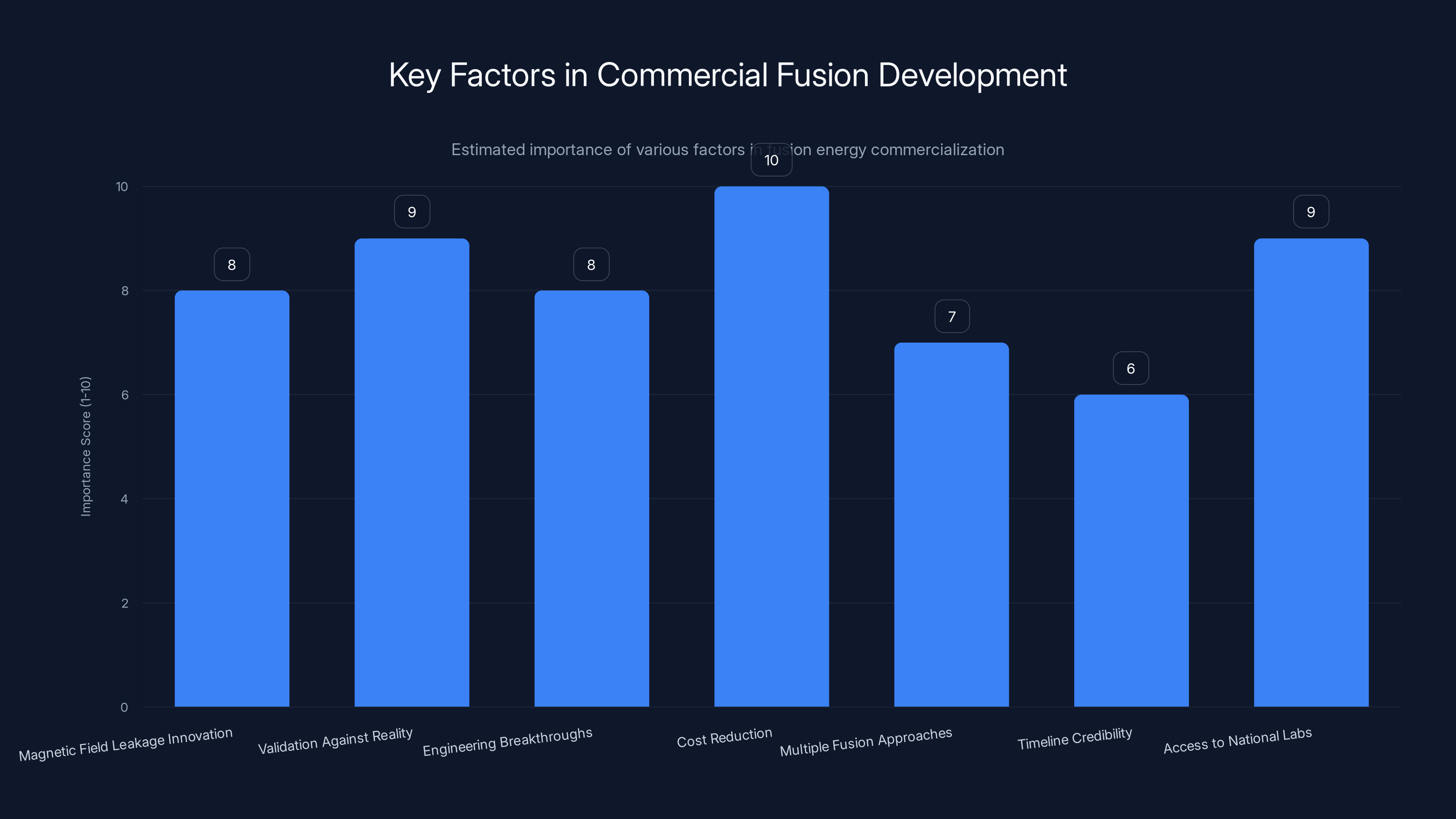

Cost reduction and validation against reality are crucial for commercial fusion success, with scores of 10 and 9 respectively. Estimated data based on key takeaways.

Eliminating the $100 Million Laser System

Here's where this matters economically. The laser system required for traditional ICF preheating costs over $100 million. That's not a typo. One hundred million dollars. For lasers alone.

Consider the full implications. You're building a fusion power plant that will compete on electricity markets. Utility-scale power plants typically cost

Now imagine removing that $100 million laser system. Suddenly your plant is cheaper. You have fewer things that can break. You have less infrastructure to maintain. You need fewer highly specialized technicians. Your supply chain becomes simpler.

Does the magnetic field leakage approach require a magnet system instead? Yes, but magnetic systems are far cheaper than laser systems at this scale. Magnets are mature technology. Laser systems for ICF applications are specialized, custom-built, and rare. Only a handful of facilities in the world have them.

The cost differential is substantial. Not quite matching the $100 million laser, but significantly lower. And more importantly, magnet systems are far more reliable and easier to maintain. A magnet doesn't degrade the same way a laser does. It doesn't have optical alignment requirements. It doesn't have the cooling demands of a massive laser.

Why Simulation Doesn't Always Match Reality

Le Chien made an important point that nuclear physics people understand but the broader industry sometimes misses: simulating something and building it are entirely different games.

Fusion physics is complex. You've got magnetohydrodynamics, plasma instabilities, radiation transport, thermodynamics, and a dozen other fields interacting simultaneously. Computers can simulate these interactions, and researchers have gotten very good at it. The physics models are sound.

But simulation and reality have a marriage problem. Small uncertainties in simulation assumptions compound. A material behaves slightly differently than modeled. Surfaces have microscopic imperfections. Temperature distributions aren't perfectly uniform. These tiny variations accumulate.

That's why experiments matter. That's why Sandia's Z Machine is valuable. It's a real, physical system where these physics interactions can be measured directly.

Pacific Fusion ran their modified cylinder design at Sandia and compared the actual results to their simulations. When reality matches simulation, it's validation. When it doesn't, you learn something. Either your simulation was wrong, or you've discovered unexpected physics.

In this case, the experiments worked. The magnetic field leaked through the cylinder as designed. The fuel preheated as expected. The compression proceeded normally. Everything aligned with simulation. That's a green light. It means Pacific Fusion's computer models are trustworthy for the next stage of development.

The Broader Context of Fusion Power Development

Pacific Fusion isn't alone in the race. The fusion landscape has become crowded with startups and major companies pursuing different approaches. Understanding where Pacific Fusion fits helps explain why this particular breakthrough matters.

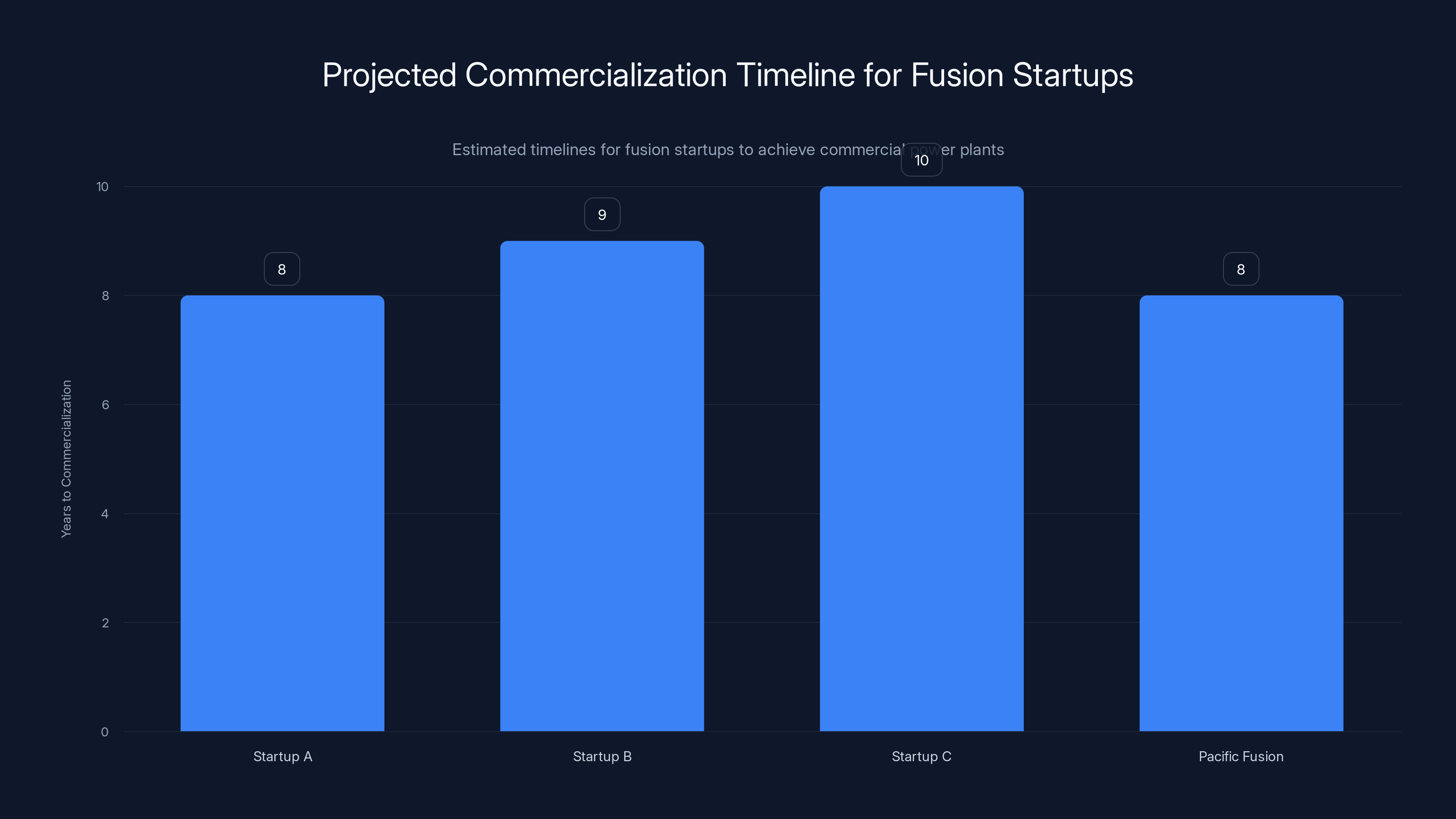

Most fusion startups target the early to mid-2030s for their first commercial power plant. That's a tight timeline—roughly 8 to 10 years away. For context, that's shorter than the time between initial concept and commercial operation for most energy infrastructure projects.

Fusion companies are pursuing multiple different approaches simultaneously. Some use lasers like NIF. Some use magnetic confinement (tokamaks and stellarators). Some use alternative compression methods. Some try hybrid approaches. The diversity matters because no one has proven the "correct" path yet.

Pacific Fusion's approach, pulser-driven inertial confinement, sits at an interesting intersection. It borrows from ICF's proven success at facilities like NIF, but uses electrical compression instead of lasers. That's potentially cheaper and simpler. Potentially. The word matters because it hasn't been proven at commercial scale yet.

Cost matters intensely. Electricity prices in most of the world hover between

Do the math backwards. A 500-megawatt fusion plant needs to generate revenue of roughly

Every

Estimated data shows that magnet systems are significantly cheaper than laser systems, costing roughly

Analyzing the Manufacturing Path Forward

One nuance worth exploring: the manufacturing challenges aren't over just because the aluminum thickness precision is reasonable.

Pacific Fusion described the precision required as equivalent to .22 caliber bullet casings. That's accurate and important. But there's a scaling question. Bullet casing manufacturing is optimized for producing millions of cases per year at relatively low unit cost. Fusion reactor targets would be produced in much smaller quantities, at least initially.

Small production volumes mean higher per-unit costs. You can't leverage the economy of scale that ammunition manufacturers enjoy. But you also don't need the level of process control that ammunition requires. A bullet needs extreme consistency because slight variations affect ballistics. A fusion target just needs consistent aluminum thickness—as long as that thickness is correct, variations elsewhere don't matter as much.

The engineering path seems clear: work with established ammunition manufacturers or precision machining shops, adapt their processes slightly, and begin producing targets. This is conventional manufacturing, not exotic new technology.

That's actually a sign of good engineering. When your solution relies on existing, proven manufacturing processes rather than inventing new ones, you've probably found something economically viable.

The Implications for Fusion Economics

Why does this announcement matter beyond Pacific Fusion's specific reactor?

It demonstrates that fusion researchers are finding clever ways to reduce costs through thoughtful engineering rather than just building bigger and more expensive machines. Commonwealth Fusion Systems is going the big-and-expensive route with SPARC. Pacific Fusion is demonstrating the small-and-clever route.

Both approaches might work. Both might fail. But the existence of multiple viable paths increases the probability that at least one fusion company will achieve commercial viability.

The cost reduction also touches on a psychological barrier in fusion. For decades, fusion has been "always 30 years away." That reputation comes partly from fundamental physics complexity, but also from the sense that fusion requires increasingly massive, expensive, specialized facilities. NIF cost $3.5 billion. Future inertial confinement fusion plants were imagined to be equally massive.

Pacific Fusion's approach suggests that you can get exceptional compression and preheating using clever engineering rather than massive laser systems. That changes the conversation. Suddenly fusion plants don't need to be boutique scientific facilities. They can be conventional industrial facilities operated by conventional power companies.

That's a significant shift in narrative.

Comparing Fusion Approaches: Strengths and Challenges

Different fusion approaches have different strengths. Inertial confinement (what Pacific Fusion uses) offers some real advantages.

First, it's pulsed, not continuous. The reactor operates in rapid pulses rather than steady state. This means you can make design choices that would be impossible in a continuously operating system. Materials don't need to handle continuous neutron bombardment. Temperature cycling is extreme but brief.

Second, ICF has a proven path to ignition. The National Ignition Facility achieved net energy from fusion reactions in 2022. That proves the concept works. Other approaches (magnetic confinement) haven't achieved the same verification.

Third, ICF scales relatively well geometrically. A bigger pellet requires proportionally more compression energy, but the physics doesn't fundamentally change. You're not discovering new barriers as you scale up.

But ICF has challenges too. The compression timescale is incredibly fast, which makes diagnostics difficult. You need to measure what happens in billionths of a second, which requires specialized equipment. The repetition rate is limited by how fast you can construct and compress new pellets.

Magnetic confinement approaches (tokamaks, stellarators) offer different trade-offs. They operate continuously, which is conceptually simpler for power generation. But they're incredibly complex to build, and achieving the plasma parameters needed for fusion has proven far harder than expected.

CFTS is betting on magnetic confinement with their SPARC tokamak. It's a different bet with different risk factors.

Preheat systems consume an estimated 5% to 10% of total energy in fusion systems, highlighting their significant role despite being a small percentage. Estimated data.

The Role of National Laboratories in Startup Development

Pacific Fusion's use of Sandia's Z Machine raises an interesting point about how modern fusion startups develop technology.

Sandia doesn't exist to help startups. It's a national laboratory funded by the Department of Energy, focused on nuclear security and energy research. But it does have capacity, and it does have relationships with private companies.

Using national lab facilities accelerates development dramatically. Building your own ICF testing facility would cost hundreds of millions of dollars and take years. Accessing an existing facility lets you run experiments in months.

This has implications for the broader startup ecosystem. Access to national labs isn't unlimited, but it's available to companies pursuing credible approaches. For fusion startups, getting time at places like Sandia, Lawrence Livermore, or Princeton PPPL is a credential. It means your approach has passed some basic credibility threshold.

Pacific Fusion clearly has that credibility. Their experimental results came from a legitimate facility, not a bench-top test in a warehouse. That matters for investor confidence and for the regulatory path to commercialization.

Risk Factors and What Could Go Wrong

Breakthrough announcements are exciting, but it's worth being skeptical about what they do and don't prove.

Pacific Fusion demonstrated one specific innovation: removing the need for a dedicated preheat laser system by allowing controlled magnetic field leakage. That's a real achievement. But one successful experiment at a national lab doesn't guarantee commercial viability.

Here's what could still go wrong:

Scaling challenges: The experiments used a small-scale setup. Scaling to commercial power levels might reveal problems that don't appear at smaller scales. Instabilities might emerge. Materials might behave differently. The physics might remain correct while engineering challenges overwhelm the project.

Repetition rate limitations: Current ICF approaches struggle with repetition rate. How many times per second can you build a new target, position it, compress it, and extract the energy? Commonwealth Fusion Systems has shown some progress here, but it's not solved. If Pacific Fusion's approach doesn't improve repetition rates significantly, they'll struggle to generate continuous power.

Energy net gain at scale: National Ignition achieved net energy, but only recently, and only at tiny scales. Scaling to commercial levels with net positive energy output is orders of magnitude harder. Pacific Fusion hasn't demonstrated net energy yet. They've demonstrated a clever engineering solution to reduce costs, but that's not the same as proving their full reactor will work.

Supply chain and manufacturing: Even if the physics works perfectly, manufacturing challenges could derail commercialization. Producing thousands of targets per day with consistent quality is harder than producing hundreds per month for experiments.

Materials science: The neutrons released from fusion reactions are incredibly energetic. Over decades of operation, reactor materials degrade. There's no material science solution yet for fusion-scale neutron damage. Pacific Fusion hasn't solved that; neither has anyone else.

These aren't criticisms. They're the real challenges that fusion companies must overcome. Pacific Fusion has solved one important problem elegantly. Many more remain.

The Competitive Landscape and Timeline Implications

Pacific Fusion isn't the only company pursuing electrical pulsed compression. Helion Energy has taken similar approaches. TAE Technologies uses alternative compression methods. Commonwealth Fusion Systems, despite being the most well-funded, is pursuing magnetic confinement, not ICF.

Each approach has different advantages, different cost structures, and different remaining challenges. The diversity is healthy. It means if one approach hits a fundamental barrier, others might still succeed.

The timeline is critical. Most fusion startups promise commercial plants in the early to mid-2030s. We're now in 2026, so that's roughly 6 to 10 years away. That's simultaneously very soon and very far away in technology development terms.

Very soon because significant engineering challenges remain. Prototype plants need to be designed, built, tested, debugged, and refined before commercial plants can be deployed. Material science problems need solutions. Regulatory frameworks need development. Electricity grid integration strategies need refinement.

Very far away because a lot can happen in 6 to 10 years. Fusion has surprised people before. What seems impossible now might be straightforward with new approaches or materials. Conversely, what seems imminent might hit an unexpected barrier.

Pacific Fusion's recent announcement pushes their timeline forward slightly by removing a major cost component. But it doesn't guarantee they'll hit their targets. It's evidence of progress, not proof of success.

Most fusion startups, including Pacific Fusion, aim to achieve commercial power plants within 8 to 10 years. Estimated data.

What This Means for Energy Markets

If fusion eventually works commercially, it would reshape energy markets. Cheap, abundant, 24/7 baseline power would transform electricity economics. But "eventually" matters here.

Right now, in 2026, fusion is still speculative. Wind and solar are proven, cheap, and increasingly economical. Battery storage is improving rapidly. Grid management strategies are evolving. Nuclear fission remains a baseload option, though politically contentious in many regions.

Fusion doesn't need to be revolutionary to be valuable. It just needs to work at a cost-competitive level. If Pacific Fusion or any of their competitors can produce electricity at

Pacific Fusion's cost reduction announcement moves them incrementally closer to the first threshold. It's not a guarantee, but it's real progress.

For investors, policymakers, and energy strategists, this matters. It suggests the physics path to commercial fusion is becoming clearer. The engineering path is becoming more defined. The economic path, while still uncertain, is becoming more tractable.

The Broader Significance of Engineering-Driven Solutions

One theme worth highlighting: Pacific Fusion's solution is fundamentally an engineering breakthrough rather than a physics breakthrough. The magnetic field leakage approach isn't new physics. It's clever application of existing physics.

This matters because engineering breakthroughs are more reproducible and scalable than physics breakthroughs. If Pacific Fusion figured out something about the fundamental nature of fusion, maybe only they can exploit it. If they just figured out a clever way to arrange existing components more efficiently, others can potentially replicate it.

The history of technology is largely the history of engineering optimization. Jet engines, internal combustion engines, transistors, batteries—all basic physics was understood long before they became economically viable. The path from physics understanding to practical technology is purely engineering.

Fusion has been stuck in the physics phase for decades. Seeing movement into the engineering phase is genuinely significant.

Funding and Private Capital Trends

Private funding for fusion has increased substantially in recent years. Billions of dollars have flowed to fusion startups from venture capital, corporate investors, and governments. Pacific Fusion has raised funding, though exact amounts aren't always disclosed.

This capital influx reflects genuine belief that commercial fusion is achievable. It also reflects a sense of urgency in energy markets. Climate change, grid reliability concerns, and energy independence motivations all push capital toward fusion solutions.

But capital alone doesn't guarantee success. Fusion is incredibly difficult technically. The best funding in the world doesn't create new physics or eliminate hard engineering challenges. However, it does accelerate development, allow better talent recruitment, and enable expensive experiments.

Pacific Fusion's experimental work at Sandia likely required significant funding. Running experiments at national labs is expensive. The ability to execute that work signals resource availability and investor confidence.

Estimated data shows Pacific Fusion's approach could significantly reduce costs compared to traditional methods like NIF and SPARC. This shift could make fusion more accessible and commercially viable.

Looking Forward: Next Steps for Pacific Fusion

Where does Pacific Fusion go from here?

The logical next step is scaling. They've demonstrated the concept works at modest scale. The next phase involves designing and building a prototype reactor that's larger, more complex, and closer to commercial specifications.

This prototype phase typically takes 3 to 5 years for fusion projects, sometimes longer. It requires solving numerous engineering challenges that don't appear at smaller scales. Thermal management becomes crucial. Materials selection becomes critical. Power plant integration requires serious thought.

After a successful prototype comes engineering and deployment of the first commercial plant. This phase involves regulatory approval, grid operator coordination, construction, and commissioning. For a first-of-kind fusion plant, this could easily take 5 years.

So realistically, Pacific Fusion hitting a 2032-2033 commercial plant deployment is aggressive but not impossible. They'd need to execute well on engineering, avoid major surprises, secure continued funding, and navigate regulatory approval.

Other fusion companies are on similar timelines. Some might hit earlier. Some might hit later. Some might fail entirely.

The Investment Thesis and Risk Reward

For investors considering fusion startups, Pacific Fusion's recent breakthrough is a positive signal but not a guarantee. Here's the investment thinking:

Bull case: Fusion becomes commercially viable in the 2030s. Pacific Fusion's cost reduction makes them competitive relative to other fusion approaches. They scale manufacturing, deploy multiple plants, become a major energy producer. Investors who backed them early see spectacular returns.

Base case: Fusion eventually works but faces more delays than expected. First commercial plants appear in the late 2030s or early 2040s. Pacific Fusion survives but faces intense competition. Returns are good but not spectacular.

Bear case: Fusion continues to face fundamental challenges. Companies merge or consolidate. Some shut down. Investors recover some capital but face significant losses. Only one or two fusion companies ultimately succeed.

The probability distribution across these cases determines expected value. Most sophisticated investors probably put >50% probability on some form of fusion success eventually. But "eventually" could mean 2035 or 2055. That timeline uncertainty is priced into risk.

Pacific Fusion's breakthrough moves probability slightly toward earlier success and slightly reduces the risk of fundamental barriers. That's valuable but incremental.

Lessons for Other Technology Domains

Pacific Fusion's approach offers lessons beyond fusion specifically.

First, clever engineering can substitute for expensive specialized hardware. Trying to remove a $100 million laser by buying a better laser is wrong. Trying to remove it by rethinking the entire system is right.

Second, validating simulations against reality matters enormously. Computer models are powerful, but they're models. The real world is more complex. Always build and test.

Third, manufacturing processes are powerful tools for optimization. Pacific Fusion didn't invent new manufacturing. They adapted existing high-precision manufacturing to their application. That's good engineering.

Fourth, incremental improvements to fundamentally sound approaches can compound into major breakthroughs. Inertial confinement fusion was conceptually proven decades ago. Incremental improvements to components, processes, and approaches have gradually moved it from "interesting physics" to "potentially practical technology."

These lessons apply across technology domains. Some of the most valuable innovations aren't physics breakthroughs—they're clever engineering applied to understood physics.

Challenges Remaining Before Commercial Viability

Even with Pacific Fusion's breakthrough, substantial challenges remain.

Repetition rate: Current ICF can't compress pellets fast enough to generate continuous power. Pacific Fusion must solve this. Commonwealth Fusion Systems has shown some progress, but it's not solved.

Net energy at scale: National Ignition achieved net energy, but only at small scale. Pacific Fusion hasn't demonstrated net energy at any scale yet. Scaling to commercial levels with net positive energy is orders of magnitude harder.

Materials durability: Neutrons from fusion damage reactor materials. Over 30+ years of operation, that damage accumulates. Material science has no complete solution yet.

Thermal conversion efficiency: Even if fusion produces energy, you need to convert it to electricity efficiently. The thermal conversion pathways are complicated by the extreme temperatures and radiation environment.

Grid integration: Fusion plants need to integrate with existing grids, follow dispatch signals, provide grid services. The operational requirements are different from current generators.

Regulatory approval: Fusion plants will be nuclear facilities. Regulatory approval will be thorough and potentially slow. The existing regulatory framework wasn't designed for fusion.

None of these are insurmountable. All are solvable engineering problems. But they're real obstacles that must be overcome before Pacific Fusion can declare victory.

The Path to Commercialization: A Practical Timeline

If Pacific Fusion executes well, what might a realistic timeline look like?

2026-2027: Refine the magnetic field leakage approach. Run more experiments. Optimize the design. Prepare for the prototype phase.

2027-2030: Design and build a prototype reactor incorporating the new findings. This would be a larger system, closer to commercial specifications. Run extended tests to verify reliability and performance.

2030-2032: Design and engineer the first commercial plant. Navigate regulatory approval. Secure power purchase agreements with utilities. Begin construction.

2033-2035: Complete construction. Commission the plant. Run operational tests. Begin selling power to the grid.

This timeline is aggressive but not unrealistic given the recent progress in fusion. It assumes no major technical setbacks and reasonable regulatory cooperation.

Other fusion companies have similar timelines. Helion Energy, TAE Technologies, and Commonwealth Fusion Systems are all aiming for first commercial plants in the early to mid-2030s.

The interesting question is whether any of them will actually hit these timelines. Technology projects often slip. Regulatory processes take longer than expected. Manufacturing challenges emerge. Integration issues arise.

But the timelines are getting shorter and more credible than they were five years ago. That's progress.

Broader Energy Sector Implications

If even one fusion startup succeeds commercially, it reshapes the energy industry. But success would take time to scale.

Even with commercial success, fusion plants won't immediately dominate electricity generation. Wind and solar will continue growing. Grid infrastructure will continue evolving. Energy storage will continue improving.

But fusion success would change the growth trajectory. Right now, many assume renewable + storage + grid management is the path to decarbonization. Add fusion to that mix, and you have additional flexibility. Fusion provides 24/7 baseline power that renewables and storage don't match.

For utilities, fossil fuel companies, and energy investors, fusion represents a potential disruption. For climate advocates, it represents a tool to accelerate decarbonization. For consumers, it potentially represents cheaper electricity in future decades.

Pacific Fusion's announcement is a small step forward in that longer journey, but small steps compound.

FAQ

What is pulser-driven inertial confinement fusion (ICF)?

Pulser-driven ICF is a fusion approach where powerful electrical pulses create magnetic fields that compress fuel pellets rapidly, causing atoms to fuse and release energy. Unlike laser-based ICF approaches used at facilities like the National Ignition Facility, Pacific Fusion's method uses electricity instead of lasers, potentially reducing cost and complexity. The compression happens in less than 100 billionths of a second, creating the extreme temperatures and densities needed for fusion reactions.

How does Pacific Fusion's magnetic field leakage approach work?

Pacific Fusion modified their fuel target cylinder design so that some magnetic field from the main compression pulse leaks through to the fuel before full compression begins. By adjusting the aluminum thickness around the fuel pellet, they control exactly how much magnetic field seeps through. This provides the preheat energy that was previously required from dedicated laser systems, but without the $100+ million cost of those systems. The approach requires precision manufacturing equivalent to .22 caliber bullet casings, which has been refined over 100+ years.

Why is eliminating the laser system significant for fusion economics?

Traditional inertial confinement fusion requires dedicated laser systems for preheating fuel, with costs exceeding $100 million. These systems add significant upfront capital costs and ongoing maintenance burden without directly generating electricity. If Pacific Fusion can eliminate this system while maintaining fusion conditions through their magnetic field leakage approach, it reduces total plant cost substantially. This makes the economics of commercial fusion power more attractive, as a larger percentage of capital investment goes directly to power generation rather than support systems.

What experiments did Pacific Fusion conduct at Sandia National Laboratory?

Pacific Fusion conducted experiments at Sandia's Z Machine, one of the most powerful pulsed power devices in the world. They tested their modified cylinder design with controlled magnetic field leakage to verify that their preheating approach would work in real hardware, not just in simulations. The experiments demonstrated that the magnetic field leaked as designed, the fuel preheated as expected, and the overall compression proceeded normally—validating that their computer simulations accurately predicted real-world behavior.

What challenges does Pacific Fusion still need to overcome?

Despite their breakthrough, several major challenges remain: achieving net energy gain at commercial scale (the National Ignition Facility only recently achieved net energy at small scale), increasing repetition rate to enable continuous power generation (current ICF systems can't compress pellets fast enough), solving materials durability issues from neutron damage over decades of operation, developing thermal conversion systems to convert fusion energy to electricity efficiently, and navigating regulatory approval as the first commercial fusion facilities. These are solvable engineering problems but represent significant remaining work before commercial deployment.

When might Pacific Fusion deploy their first commercial plant?

Pacific Fusion likely targets the early to mid-2030s for first commercial deployment, following a development timeline of prototype construction (2027-2030), commercial plant design and regulatory approval (2030-2032), and construction and commissioning (2033-2035). This timeline is aggressive but consistent with other fusion startups' timelines and recent technical progress. However, technology projects often slip, so actual deployment could occur several years later if unexpected challenges arise.

How does Pacific Fusion's approach compare to other fusion methods?

Pacific Fusion uses pulser-driven inertial confinement fusion, which borrows from proven ICF physics (demonstrated at the National Ignition Facility) but replaces expensive lasers with electrical compression. This differs from Commonwealth Fusion Systems' magnetic confinement tokamak approach and other alternative fusion methods. Each approach has different cost structures, remaining challenges, and timelines. The diversity means that if one approach hits a fundamental barrier, others might still succeed, increasing the overall probability of commercial fusion success.

What makes national laboratory experiments valuable for startup development?

Access to facilities like Sandia's Z Machine accelerates fusion development dramatically. Building equivalent experimental facilities would cost hundreds of millions and take years. Using existing national lab capacity lets companies validate concepts in months rather than years. It also provides credibility—getting time at a national lab signals that your approach has passed basic feasibility thresholds and attracts investor confidence. For regulatory approval of first commercial plants, having validated results from respected national laboratories strengthens the case for safety and performance.

What is the broader significance of Pacific Fusion's breakthrough?

Pacific Fusion's innovation demonstrates that fusion cost reduction can come from clever engineering applied to understood physics rather than requiring exotic new discoveries. This shifts fusion development from purely physics-driven to increasingly engineering-driven. The distinction matters because engineering solutions are reproducible, scalable, and more economically viable than physics research. It suggests fusion is transitioning from the research phase to the engineering phase, which is when technologies typically become commercially viable.

How might successful fusion affect electricity markets?

If Pacific Fusion or competitors achieve commercial viability producing electricity at $50-100 per megawatt-hour by the mid-2030s, it would provide an additional baseload power source complementing renewables and storage. Fusion wouldn't immediately displace existing generation but would reshape growth trajectories. For climate decarbonization, fusion adds a powerful tool. For utilities, it provides flexibility. For fossil fuel industries, it represents disruption. For consumers, it potentially means cheaper electricity in future decades. Success wouldn't transform markets overnight but would create substantial long-term shifts.

Key Takeaways

-

Pacific Fusion's magnetic field leakage innovation eliminates a $100+ million laser system by cleverly allowing the main compression pulse to partially preheat fuel before full compression, using precision manufacturing equivalent to bullet casings rather than exotic new technology.

-

Validation against reality matters more than simulation perfection: Pacific Fusion's experiments at Sandia National Laboratory confirmed that their computer models accurately predicted real-world behavior, a critical prerequisite for scaling to commercial systems.

-

Engineering breakthroughs matter as much as physics breakthroughs: The path to commercial fusion increasingly relies on clever engineering applied to understood physics rather than exotic physics discoveries, making commercialization timelines more credible.

-

Cost reduction is the central economic challenge for fusion: With electricity markets pricing power at $50-150 per megawatt-hour, fusion plants need dramatic cost reductions to compete. Pacific Fusion's breakthrough removes a significant cost component, incrementally improving economics.

-

Multiple fusion approaches reduce risk and increase probability of success: Pacific Fusion's ICF approach, Commonwealth Fusion Systems' magnetic confinement, and other methods pursue different paths. If one hits a barrier, others might still succeed, improving overall commercial fusion probability.

-

Timeline credibility is increasing but remains uncertain: While Pacific Fusion and others target early-to-mid 2030s for first commercial plants, technology development often faces unexpected delays. Reasonable probability windows extend to late 2030s or early 2040s.

-

Access to national laboratories accelerates development significantly: Pacific Fusion's use of Sandia's Z Machine compressed development timelines and provided credibility, demonstrating the value of relationships between startups and government research facilities.

Related Articles

- How Lunar Energy's $232M Funding Round Is Reshaping Grid Storage [2025]

- General Fusion's $1B SPAC Merger: Fusion Power's Survival Strategy [2025]

- Why America's $12B Mineral Stockpile Proves the Future Is Electric [2025]

- US Offshore Wind Court Orders: Construction Restart [2025]

- SpaceX's 1 Million Satellite Data Centers: The Future of AI Computing [2025]

- SpaceX's Million Satellite Data Centers: The Future of Cloud Computing [2025]

![Pacific Fusion's Cost-Cutting Innovation: The $100M Laser Elimination [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/pacific-fusion-s-cost-cutting-innovation-the-100m-laser-elim/image-1-1770313493466.jpg)