Space X's Million Satellite Data Centers: The Future of Cloud Computing [2025]

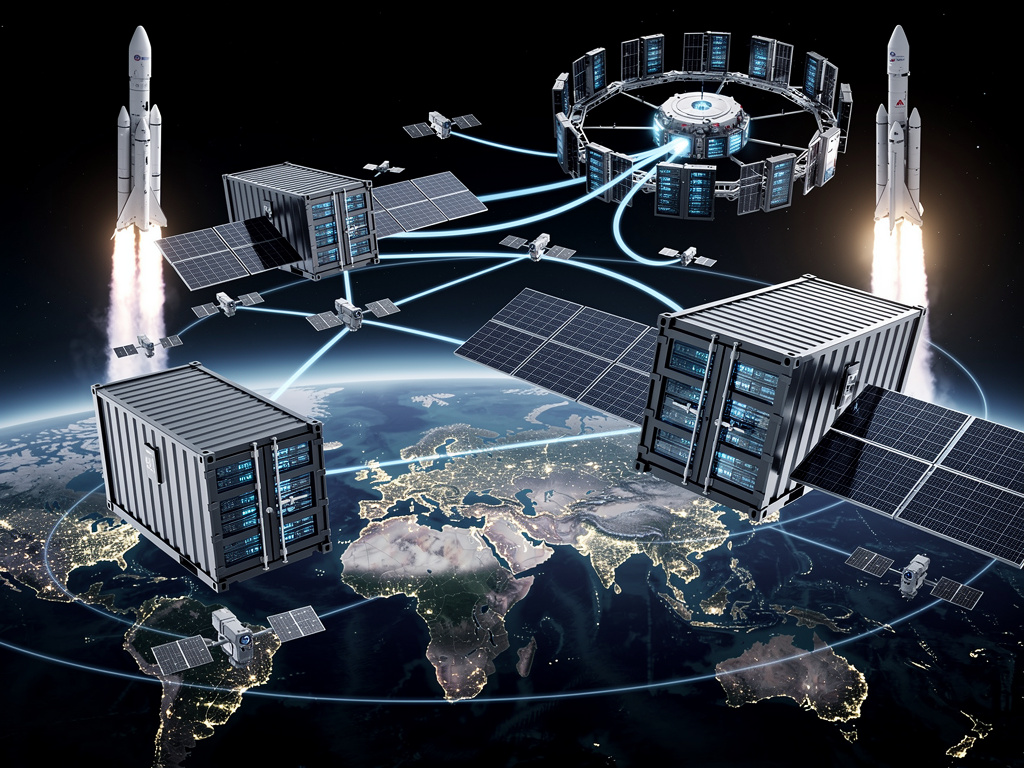

There's a moment in every technology's evolution when someone looks at an existing problem and thinks, "What if we just moved it somewhere completely different?" That's essentially what Space X did when it filed a request with the Federal Communications Commission seeking approval to deploy up to one million solar-powered data center satellites into low Earth orbit.

On the surface, the idea sounds delightfully absurd. But peel back the layers, and there's a genuinely compelling logic underneath. Data centers consume enormous amounts of water for cooling, consume staggering quantities of electricity, and they're increasingly unwelcome in communities that see them as environmental drain. Put them in space? No neighbors to complain. No aquifers to deplete. No power grid to strain. Just endless sunshine and the cold vacuum of space.

But here's where reality gets complicated. The Kardashev II civilization rhetoric aside, this proposal raises legitimate questions about space traffic, orbital debris, regulatory frameworks, and whether we're actually solving problems or just externalizing them to a new frontier. Let's dig into what Space X actually proposed, why it matters, and what could go wrong.

TL; DR

- The Proposal: Space X filed for FCC approval to launch one million solar-powered data center satellites into low Earth orbit, communicating via laser links

- The Promise: Orbital data centers eliminate water use, reduce electricity costs, and operate in perpetual sunlight without environmental community opposition

- The Challenge: One million satellites would more than quadruple the number of orbital objects currently in space, dramatically increasing collision and debris risks

- The Reality: Space X's strategy involves requesting massive numbers as a negotiating anchor, so expect the final approved constellation to be substantially smaller

- The Timing: This addresses a critical industry pressure point—communities worldwide are increasingly blocking terrestrial data center construction

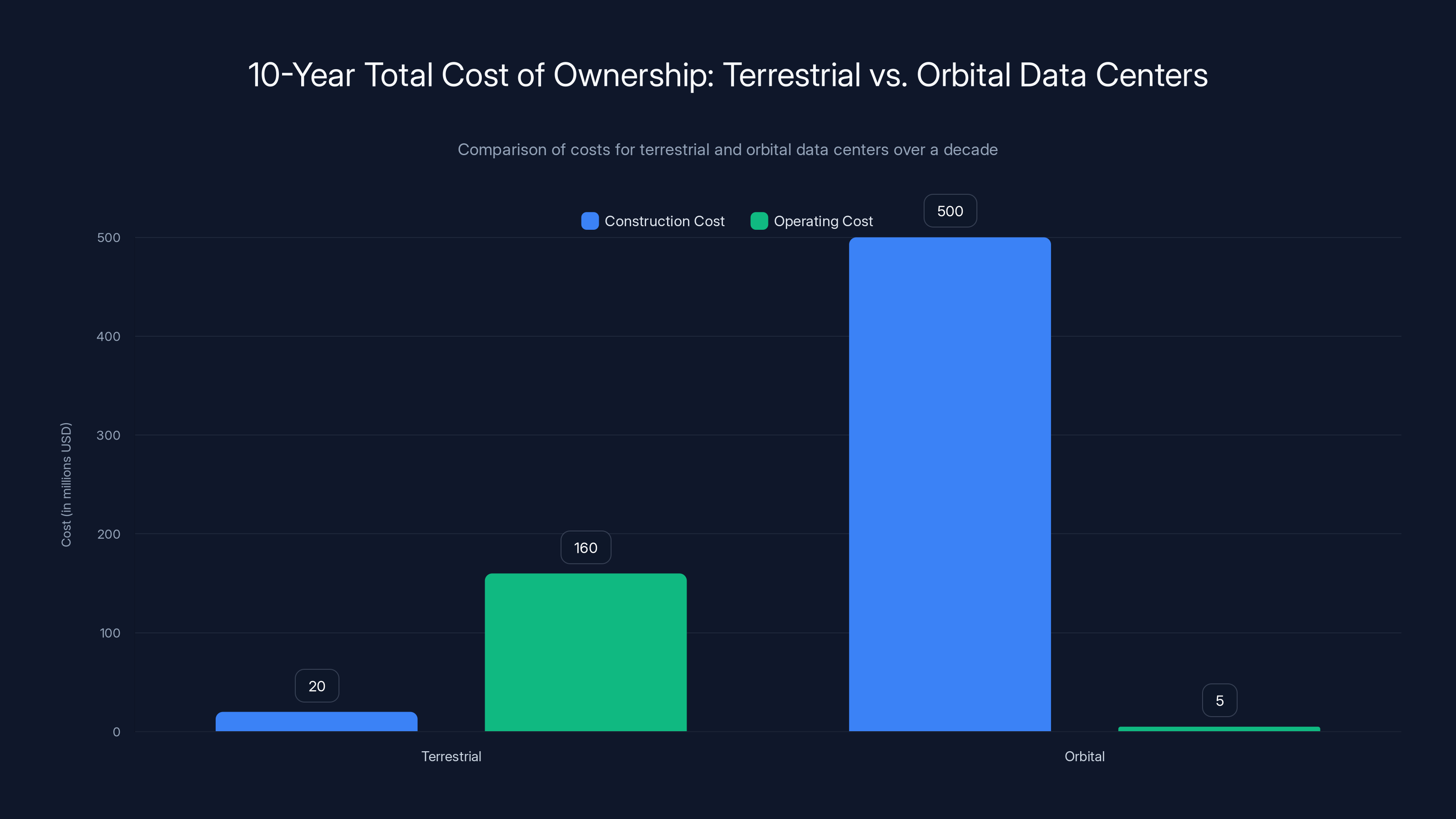

Over a 10-year period, terrestrial data centers have significantly lower total costs compared to orbital ones, primarily due to the high initial deployment costs of orbital data centers.

The Problem Space X Is Trying to Solve: Data Centers Are Becoming Toxic to Communities

Let's start with the actual problem statement, because the orbital data center proposal doesn't make sense without understanding what's happening on Earth.

Data centers have become essential infrastructure for the AI boom. Training large language models, running inference workloads, storing user data—all of it requires massive computational facilities. But here's the uncomfortable part: they're unpopular everywhere they show up.

A typical hyperscale data center consumes between 1 to 5 million gallons of water per day for cooling. In Texas, where water is already scarce, data centers have sparked fierce community resistance. In Ireland, local opposition to Meta and Google facilities has become so intense that the government is now restricting new data center construction. Virginia's data center corridor, once heralded as an economic engine, now faces pushback from residents concerned about electricity demand and environmental impact.

Electricity consumption is the second problem. A single hyperscale data center can consume 10 to 20 megawatts of continuous power—equivalent to a small city. This strains local power grids and forces utilities to invest in new generation capacity. In some cases, it literally means fossil fuel plants stay online longer because of the demand.

Then there's the community opposition factor. Unlike a factory or office building, people don't really understand what a data center does, so they just know it as "the big building using all our water and electricity." Local governments have started blocking approvals. Oregon counties have rejected Meta proposals. New Mexico has created buffer zones around data centers. The trend is unmistakable: terrestrial data center expansion is hitting local political resistance.

The major cloud providers—Amazon, Microsoft, Google, and Meta—have been aggressively seeking new sites. But the scarcity of politically viable locations is becoming a real constraint on their AI ambitions.

That's the problem Space X identified. And the solution they proposed? Orbit.

What Space X Actually Proposed: The FCC Filing Details

When Space X filed with the FCC in May 2025, the filing was relatively sparse on technical details but bold in scope. The company proposed establishing a constellation of solar-powered data center satellites in low Earth orbit (LEO), operating at altitudes between approximately 340 and 460 kilometers above Earth's surface.

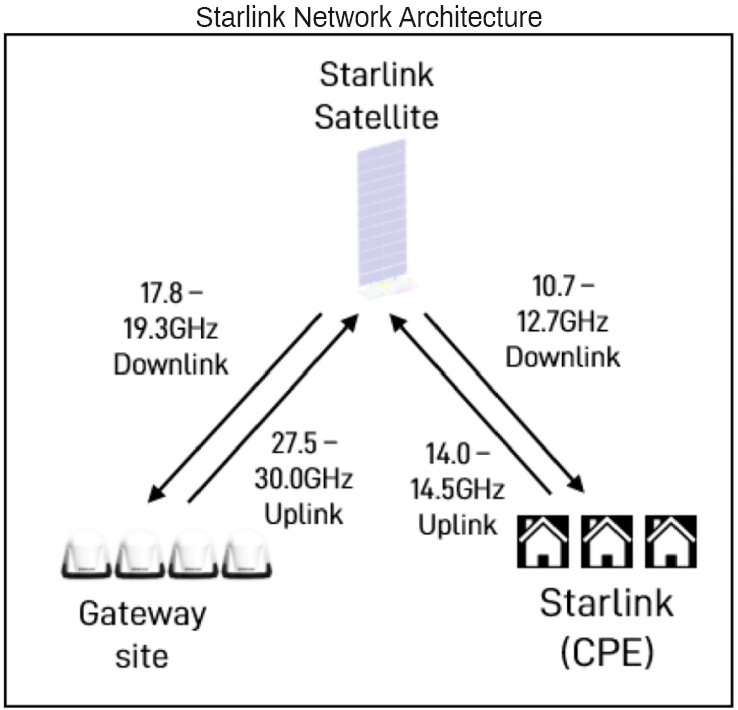

The key technical architecture involves several connected elements. Each satellite would be equipped with solar panels for power generation. They'd communicate with adjacent satellites using laser inter-satellite links rather than radio signals bouncing through ground infrastructure. This creates a self-contained orbital network independent of terrestrial connectivity constraints.

Thermally, the design exploits a fundamental advantage of space: empty space has no medium for heat conduction. A radiator panel on an orbital data center can reject heat directly into the vacuum, achieving cooling efficiency impossible on Earth where ambient temperatures and humidity constrain heat rejection.

The power system relies on solar generation with battery storage for eclipse periods (when satellites pass through Earth's shadow, lasting roughly 30-40 minutes per orbit). Rather than needing continuous power from a grid, orbital data centers generate their own during daylight passes.

The filing speaks grandiose terms about becoming a "Kardashev II civilization"—a civilization capable of harnessing a star's entire energy output. While that's futuristic rhetoric more than engineering specification, it does reflect Space X's actual vision: orbital infrastructure as a fundamental enabler of near-infinite computational capacity.

But here's what matters most about the proposal: the one million satellite figure almost certainly isn't the actual target. This is Space X's negotiating position. Companies filing with regulators often request approval for larger deployments than they actually intend, expecting negotiation to land on a smaller number. Think of it as the opening bid in a regulatory auction.

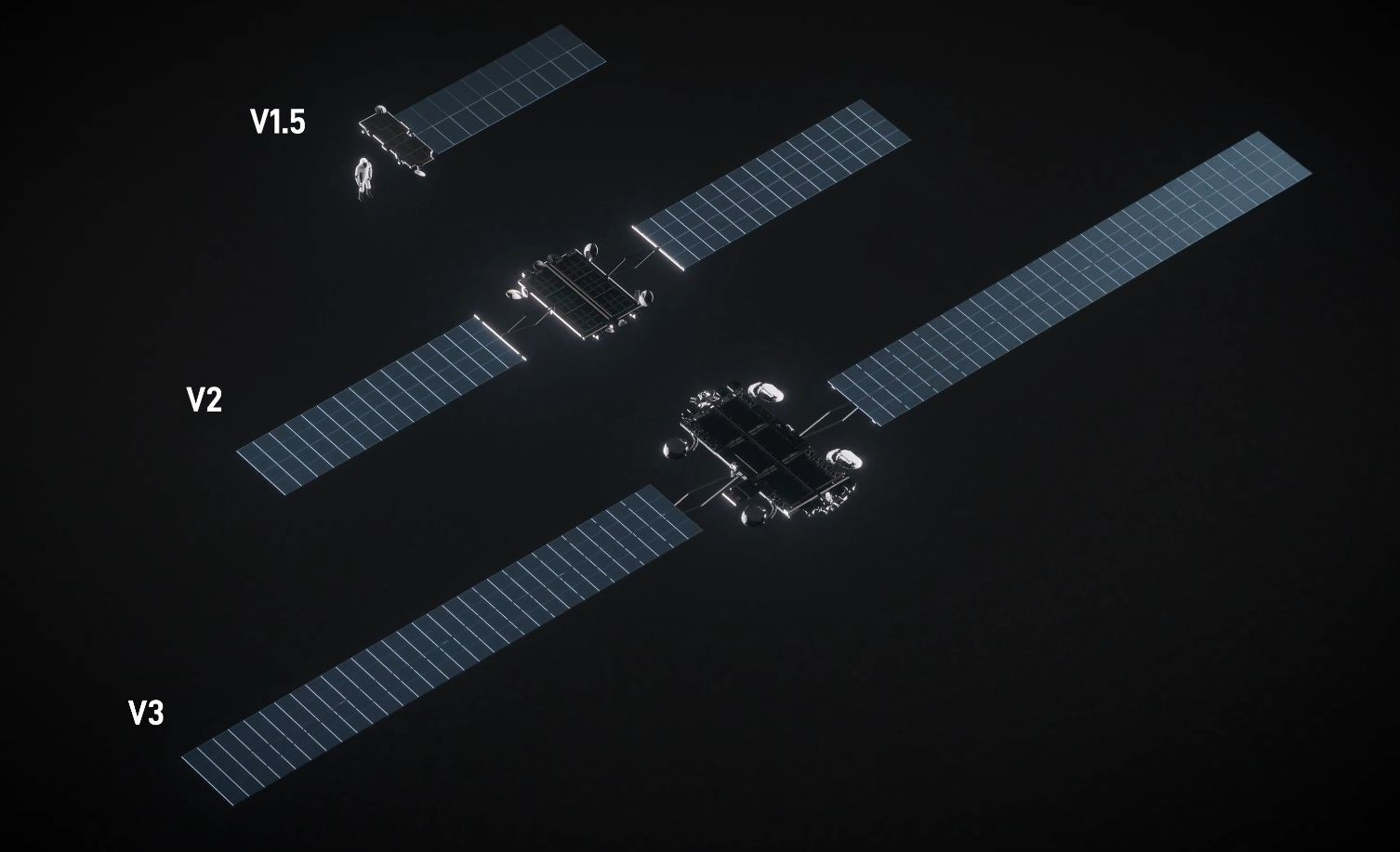

Historically, Starlink (Space X's broadband satellite network) originally proposed 12,000 satellites and later amended to 42,000. As of 2025, roughly 7,000 are in orbit. The actual deployed constellation is typically 30-50% of the initially requested number.

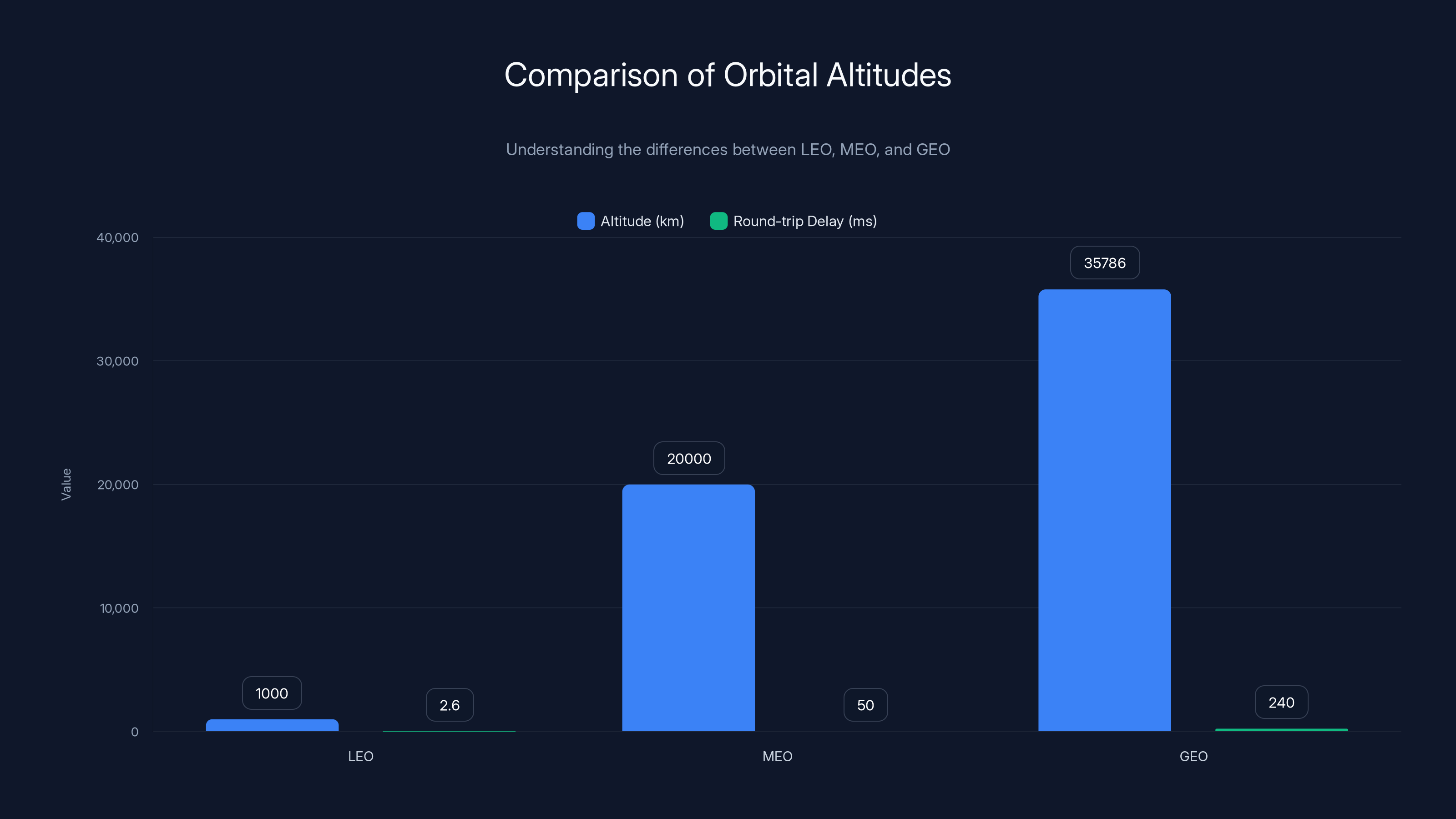

LEO offers the shortest round-trip delay, making it ideal for data centers that require fast communication. Estimated data based on typical values.

The Technical Advantages: Why Space Cooling Actually Works

Let's examine why orbital data centers aren't completely absurd from a physics standpoint. There are genuine technical advantages.

Thermal Rejection and Cooling Efficiency

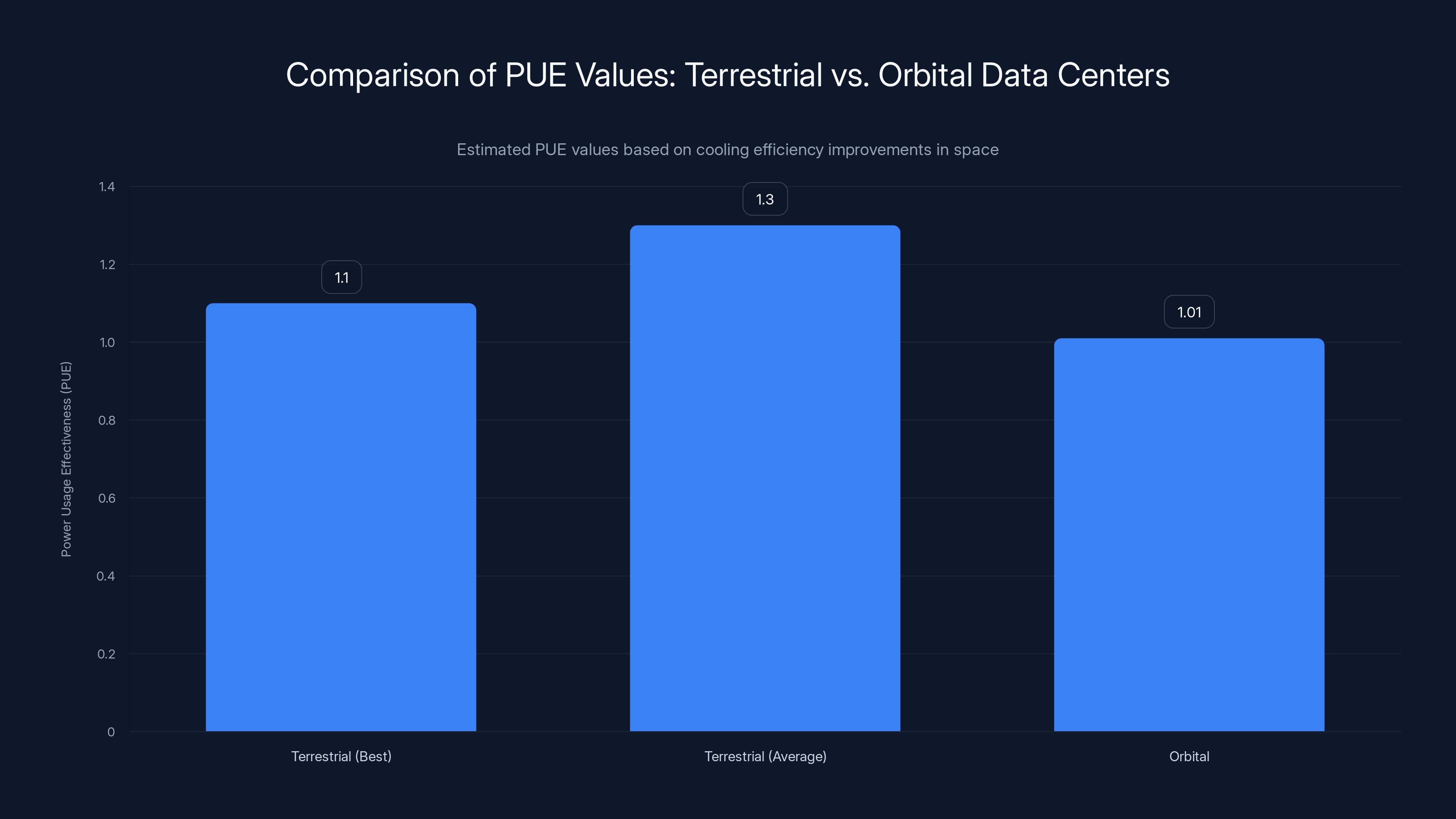

A data center's primary operating cost challenge is cooling. Modern hyperscale facilities maintain data center floors at roughly 25-27°C. The cooling infrastructure (chillers, pumps, airflow systems) consumes approximately 30-40% of total data center power. This is called Power Usage Effectiveness or PUE—the ratio of total facility power to IT equipment power.

A PUE of 1.1 means 10% overhead for cooling and infrastructure. A PUE of 2.0 means 50% overhead. The best terrestrial data centers achieve PUE values around 1.1-1.15. Orbital data centers could theoretically achieve PUE values near 1.01 or 1.02 because thermal radiation into vacuum is vastly more efficient than any terrestrial cooling method.

The physics: A radiator panel in space radiates heat via thermal radiation according to the Stefan-Boltzmann law:

Where epsilon is emissivity, sigma is the Stefan-Boltzmann constant, A is area, and T is absolute temperature. In vacuum, with nothing to absorb that radiation, heat dissipates extremely efficiently. A terrestrial air-cooled radiator must reject heat to ambient air at roughly 25-30°C. An orbital radiator can reject heat to the cosmic microwave background at approximately 2.7 Kelvin. The temperature differential is vastly larger.

This translates directly to power savings. If cooling overhead drops from 35% to 5%, that's a 30% reduction in total facility power consumption. For a 10-megawatt data center, that's 3 megawatts of instant savings—equivalent to powering 2,500 homes.

Perpetual Solar Power

Orbital data centers operate in continuous or near-continuous sunlight. At LEO altitudes, satellites experience eclipse periods of 30-40 minutes per 90-minute orbit during certain times of year. But outside eclipse season, they receive unfiltered solar radiation roughly 8-10 hours per day at significantly higher intensity than terrestrial solar panels experience (no atmospheric attenuation, no cloud cover).

The solar power density at Earth's orbital distance is approximately 1,361 watts per square meter (the solar constant). Modern solar panels achieve 20-22% efficiency, meaning each square meter generates roughly 270-300 watts. A data center consuming 10 megawatts would need approximately 33,000-37,000 square meters of solar panels. That's roughly the footprint of 5-6 football fields, which is entirely feasible for a satellite constellation.

Batteries handle eclipse periods. Current space-qualified battery technology (lithium-ion chemistries similar to those in Tesla vehicles) can store enough energy for the 30-40 minute eclipse with acceptable weight and volume.

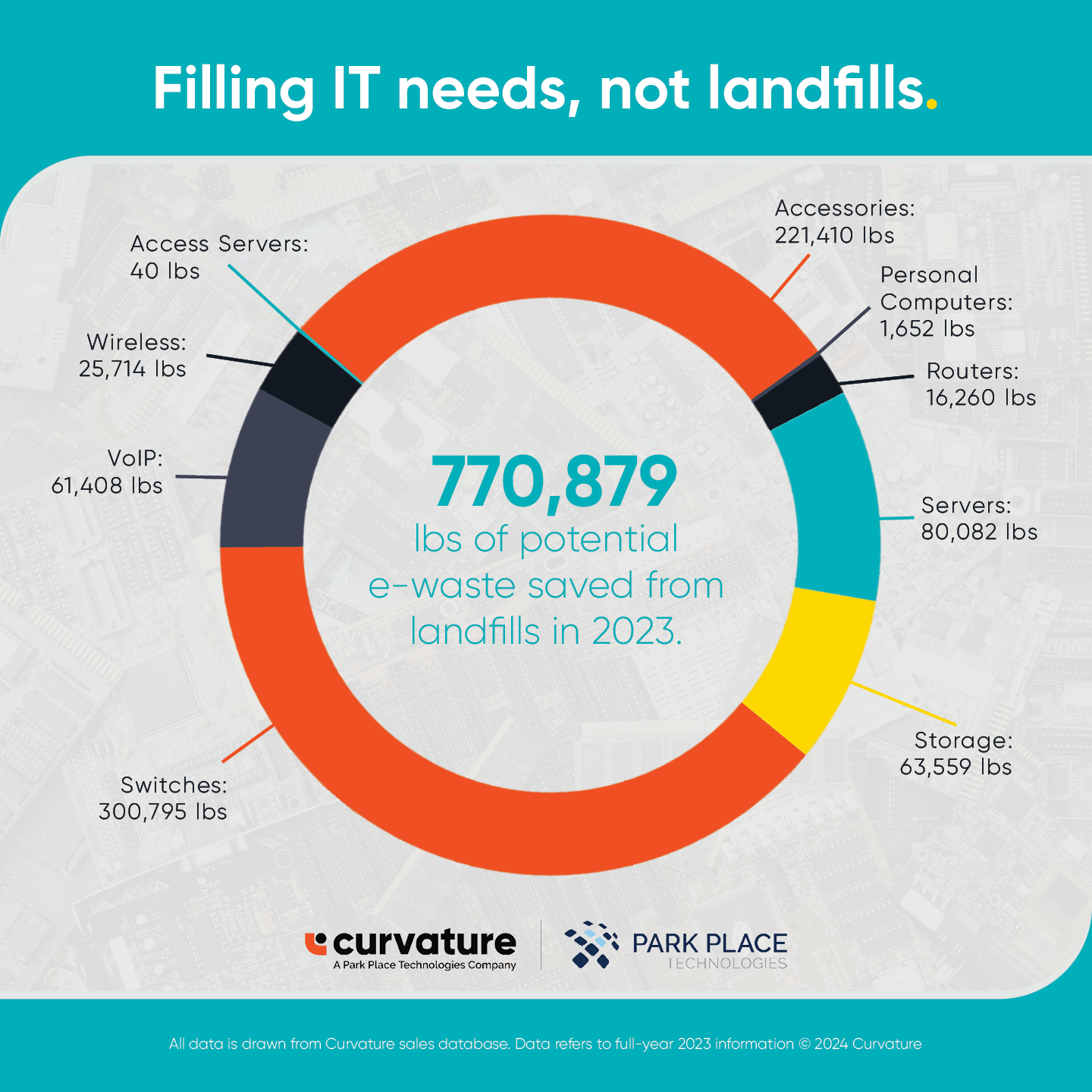

No Water Consumption

This is the cleanest advantage. Terrestrial data centers either use evaporative cooling (which consumes 1-3 million gallons daily) or closed-loop systems with cooling towers. Orbital data centers use none of it. The environmental benefit is straightforward: zero water consumption means zero impact on local aquifers or water supplies.

For communities facing water stress—which increasingly includes parts of Texas, the Southwest, and even traditionally water-rich regions—this is a material difference.

The Massive Problem: Space Debris and Orbital Collision Risk

Here's where the proposal collides with reality. Orbital mechanics and debris management are unforgiving fields.

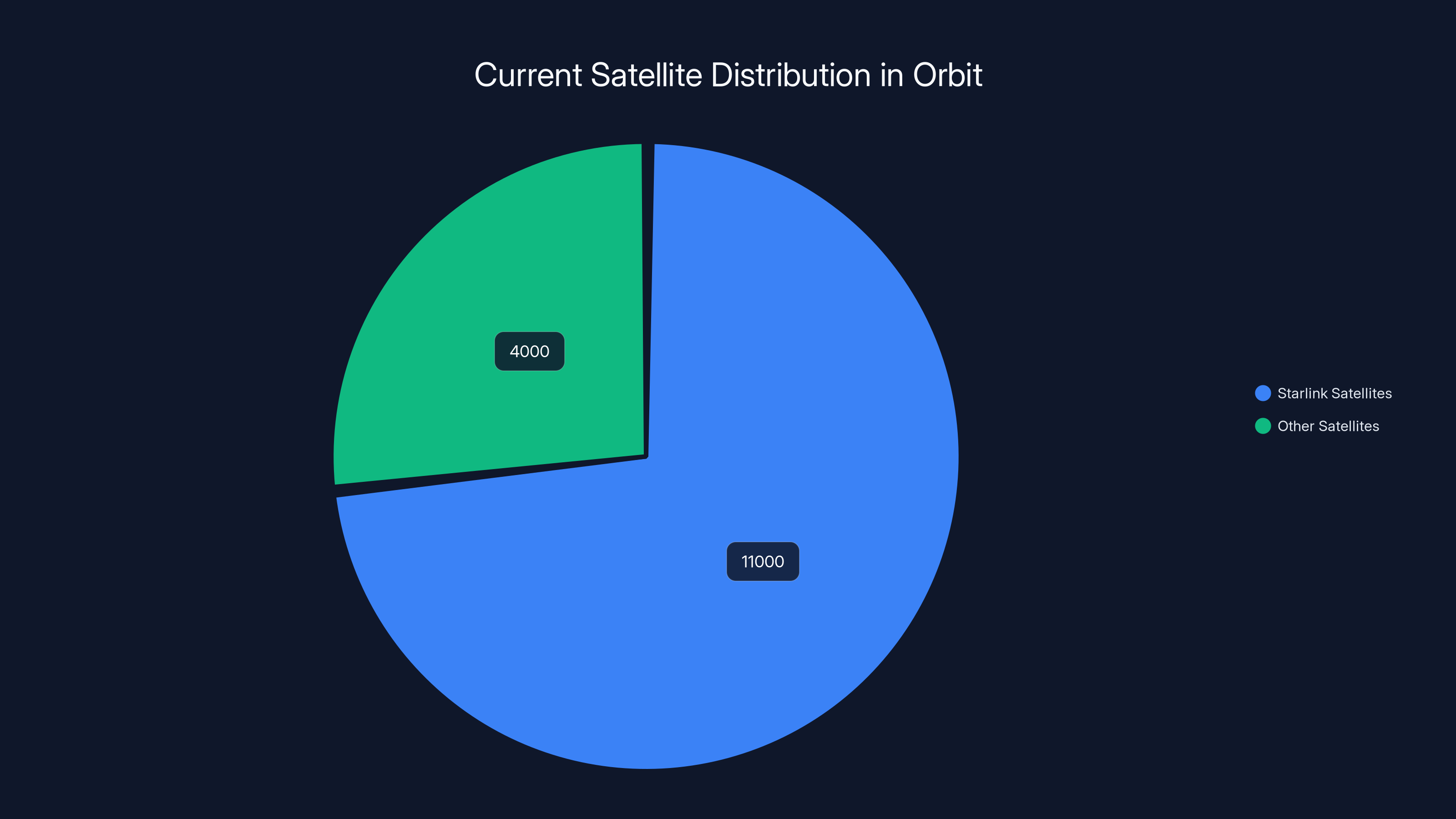

Currently, the European Space Agency estimates approximately 15,000 satellites in orbit around Earth. Most are Starlink satellites (over 11,000). The remainder includes legacy communications satellites, Earth observation platforms, and national space assets.

One million satellites would increase that by roughly 67 times. To put it differently, Space X's proposed constellation would add more satellites than all other human space activity combined.

But satellites aren't the only problem. The bigger issue is space debris. Every defunct satellite, rocket stage, and collision fragment is now a piece of debris. The ESA estimates there are approximately 100 million debris pieces larger than 1 millimeter. About 34,000 of these are trackable (larger than 10 cm).

Each of these debris pieces travels at orbital velocity—roughly 7.8 km/second at LEO altitudes. At that speed, a 1-centimeter piece of debris hits with the kinetic energy of a small grenade. A 10-centimeter piece is equivalent to a car crash. This creates the Kessler Syndrome risk: collisions generate more debris, which causes more collisions, which generates exponentially more debris in a cascading catastrophe.

One million additional satellites in LEO dramatically increases collision probability. Even with perfect orbital spacing, you're creating a much denser environment.

Let's calculate a rough order of magnitude. The LEO region spans from roughly 160 km to 2,000 km altitude, though most operational satellites cluster between 300-600 km. If we approximate usable LEO as a shell from 300 to 600 km:

With Earth's radius at 6,371 km, this yields a volume of roughly 1.2 × 10^15 cubic kilometers. One million satellites distributed through this volume gives an average density of about 0.83 satellites per 1.2 × 10^9 cubic km—very sparse on an absolute basis.

But satellite collisions aren't random three-dimensional events. Satellites cluster in specific orbital inclinations and altitudes. Space X's data center constellation would likely concentrate at similar altitude bands, creating local density hot spots. In those regions, collision probability increases dramatically.

Space X's filing addresses this by proposing satellite deorbiting procedures: end-of-life satellites would be commanded to deorbit and burn up in the atmosphere. This is technically feasible but operationally challenging. A satellite malfunction at end-of-life could leave debris in orbit indefinitely. And if even 1% of one million satellites experience failures that prevent deorbiting, you'd be adding 10,000 permanent debris pieces.

Regulatory Reality: Why One Million Satellites Won't Actually Happen

Space X's filing asked the FCC for authorization to deploy one million satellites. The FCC is extremely unlikely to grant approval for that number. Here's why.

The regulatory framework for orbital debris is still developing. The U. S. government, through the Office of Space Commerce, has started implementing debris mitigation requirements. The basic principle: satellites should deorbit within 25 years. This is a compromise between safety (shorter times are safer) and operational reality (longer times allow longer mission life).

For debris mitigation to be credible, companies must demonstrate end-of-life disposal procedures. Deorbiting a single satellite is straightforward. Deorbiting one million satellites introduces logistical and reliability challenges that cascade through the entire proposal.

Additionally, other nations will object. The European Space Agency, Japanese space authorities, and Chinese space agencies have all expressed concern about orbital crowding. A U. S. FCC approval for a million satellites would generate immediate diplomatic pushback.

There's also the self-interest factor. Amazon's Project Kuiper (a competing broadband constellation), One Web, and numerous international operators all have orbital slots. They have economic incentive to oppose regulations that allow Space X to saturate the spectrum and orbital real estate.

Historically, FCC approvals for satellite constellations have reduced initial requests by 50-70%. Space X's Starlink asked for 42,000 satellites in some filings; current deployed constellation is roughly 7,000 approved for expansion to 12,000. The company's strategy is to ask for the moon and accept Earth as a compromise.

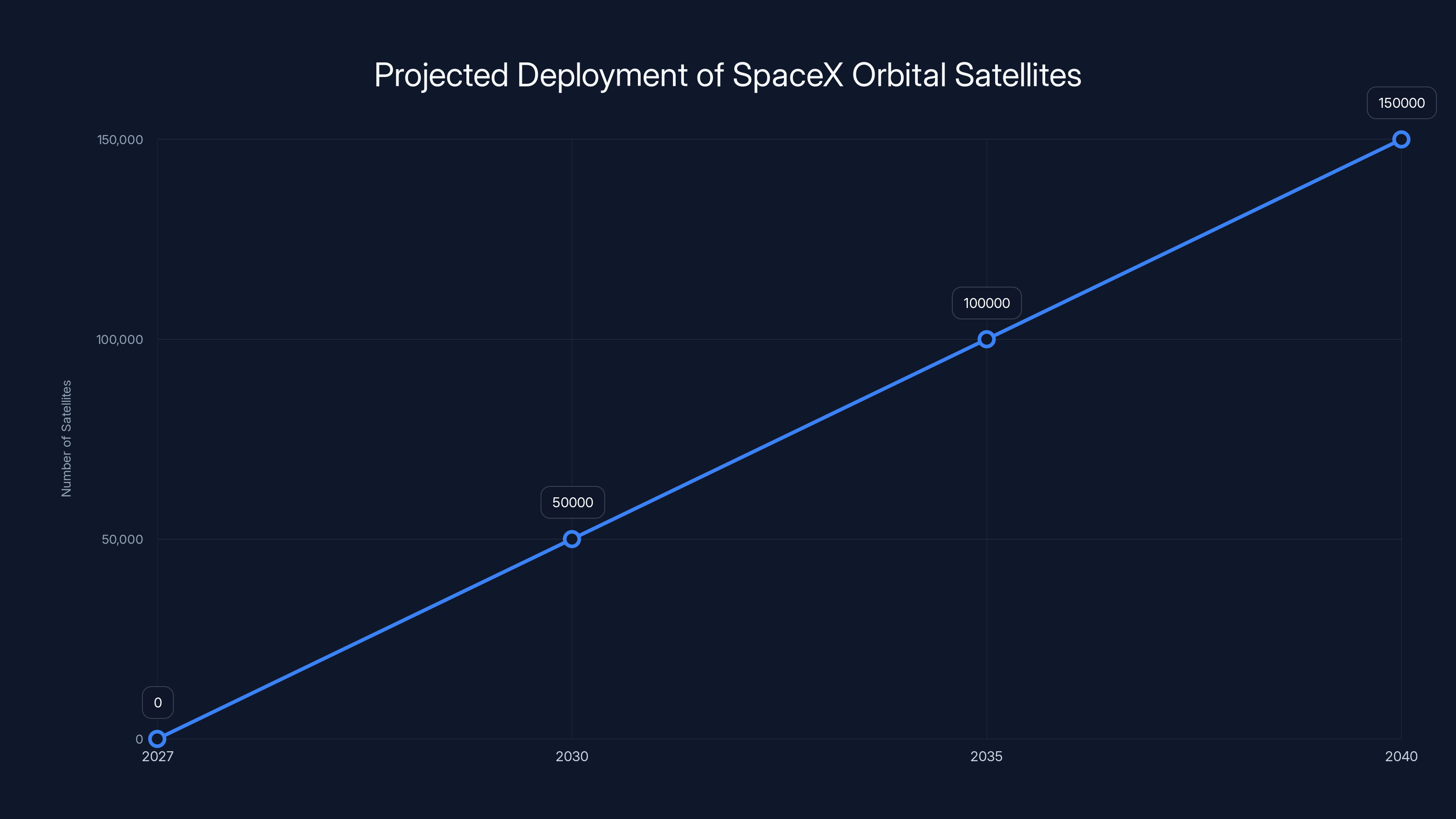

A realistic estimate: if Space X eventually deploys data center satellites, the approved constellation is more likely 50,000-150,000 satellites rather than one million. That's still a significant increase in orbital density, but it's materially different from the filing.

Orbital data centers could achieve PUE values as low as 1.01, significantly lower than the best terrestrial centers at 1.1, due to efficient thermal radiation in space. Estimated data.

Latency: The Achilles' Heel Nobody Talks About

There's a critical technical problem that Space X's filing glosses over, and it might be the actual killer for this proposal: latency.

Data centers in LEO orbit at altitudes around 400 km, moving at roughly 7.8 km/second. Signal propagation time from ground to satellite and back is determined by the speed of light: 300,000 km/second. The round-trip time from Earth's surface to a LEO satellite and back is approximately 2.6 milliseconds.

That doesn't sound like much. But modern AI applications and financial trading systems operate on the microsecond scale. High-frequency trading algorithms make decisions in under 100 microseconds. Machine learning inference on neural networks demands sub-millisecond latency for acceptable user experience.

A 2.6 millisecond round-trip introduces latency that's 26 times worse than the microsecond scale these applications demand. For some workloads (batch processing, model training), this might be acceptable. For others (real-time inference, interactive applications), it's a non-starter.

Space X's filing mentions using laser inter-satellite links to route traffic between satellites and eventually to ground stations. But that doesn't solve the fundamental physics problem: the signal has to travel from ground to orbit and back. There's no way around that 2.6 millisecond baseline, and in practice it's worse because routing through multiple satellites adds hops.

Compare this to terrestrial data centers, which can achieve sub-millisecond latency for applications in the same region. A customer in California accessing a data center in Oregon experiences latency under 1 millisecond. Orbital access adds 2.6+ milliseconds, making it uncompetitive for latency-sensitive workloads.

This is why Space X's proposal makes most sense for non-interactive workloads: batch processing, model training, data analytics, research computing. These workloads are less latency-sensitive but are also less profitable and require less infrastructure investment than real-time applications.

Where h is orbital altitude (~400 km) and c is speed of light (300,000 km/s), yielding approximately 2.67 milliseconds per hop. Multi-hop paths (satellite to satellite to ground) would add 2.67 milliseconds per additional hop.

The Cloud Provider Perspective: Why Companies Are Interested Despite Concerns

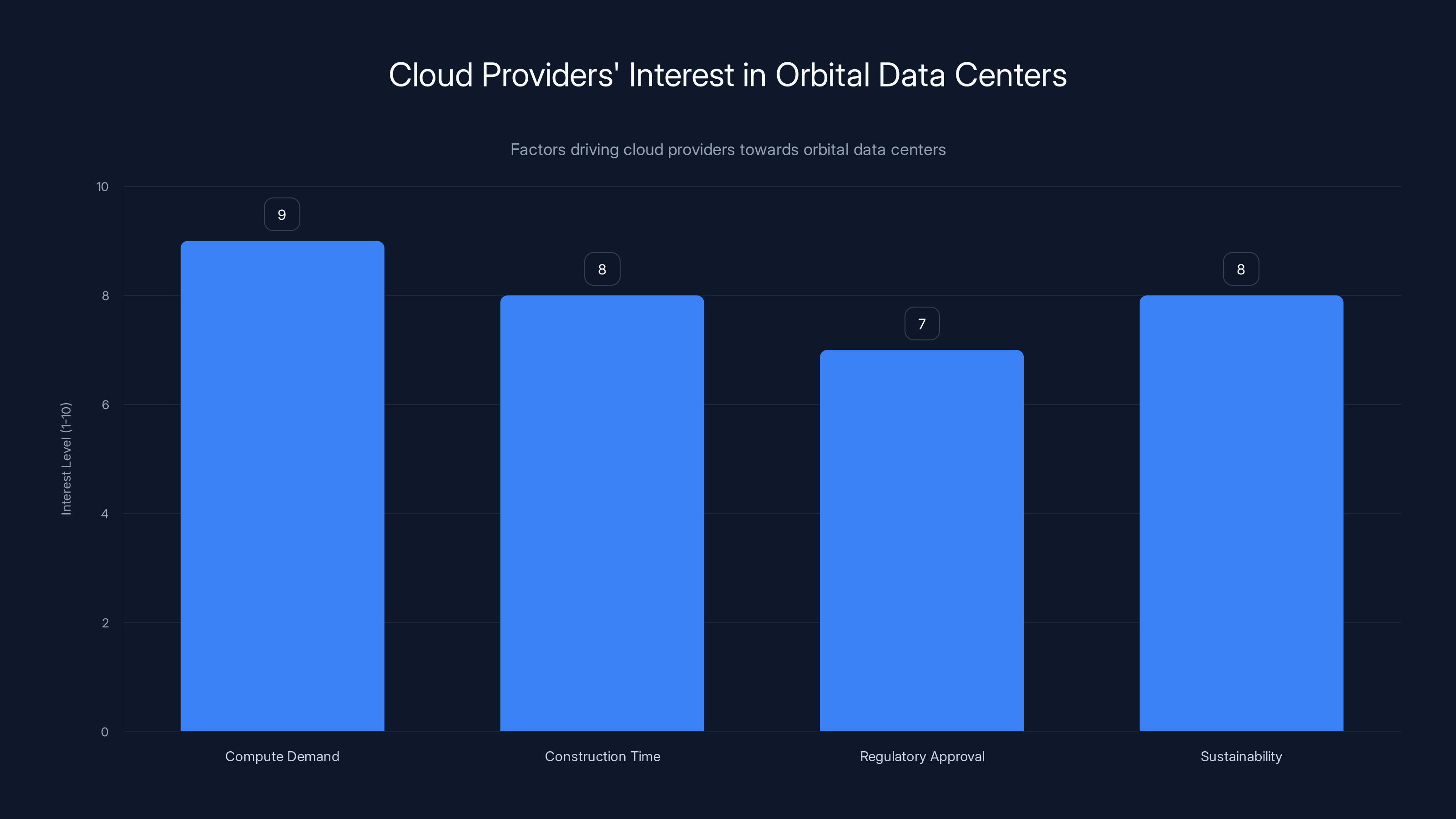

Despite the latency and debris concerns, major cloud providers are watching this closely. Here's why: they're desperate for more capacity.

The AI boom has created unprecedented demand for compute. Open AI, Anthropic, Google Deep Mind, and others are training increasingly massive models that require staggering computational resources. Training a state-of-the-art language model consumes 10-50 petaflops of compute—that's millions of GPUs running continuously for months.

Large language model inference is almost as demanding. As these models proliferate, cloud providers face capacity constraints. Data center construction takes 18-24 months. Regulatory approval takes 6-12 months before that. The timeline is too long for the growth trajectory they're experiencing.

Orbital data centers offer a potential shortcut: launch satellites, deploy compute, begin operation in weeks rather than years. The economics are speculative, but the potential to bypass terrestrial construction timelines is genuinely attractive.

Additionally, from a corporate sustainability perspective, orbital data centers are a PR win. Cloud providers face increasing pressure on environmental footprint. An orbital facility using zero water, running on solar power, and claiming near-zero emissions is remarkable marketing material.

Platforms like Runable are also exploring how to optimize AI workloads for distributed execution—important because orbital infrastructure will eventually require intelligent load balancing and task scheduling across multiple geographic and orbital locations.

Use Case: Automating the selection and deployment of workloads to optimal data center locations (terrestrial or orbital) based on latency, power cost, and environmental impact requirements.

Try Runable For FreePower Economics: When Does Orbital Make Sense Financially?

Let's run some actual numbers on the economics. This is where the proposal gets interesting because the math isn't obviously wrong.

A hyperscale terrestrial data center typically costs **

In high-cost regions, electricity can run $0.10-0.15 per kilowatt-hour. With cooling overhead at 35% of power draw, a 10-megawatt facility consuming 13.5 megawatts total experiences annual power costs of:

Now for orbital. A satellite costs roughly **

But operating costs are near-zero: the satellite generates its own power via solar panels. After accounting for battery replacements and periodic repairs, ongoing power costs approach zero. Over a 10-year mission life, that's **

The numbers don't work unless you stack multiple advantages: elimination of water costs (

At these numbers, terrestrial wins. But if you factor in environmental premiums (companies paying 20-30% more for guaranteed renewable compute), elimination of regulatory delays, and exclusion from community opposition battles, the calculus shifts.

Moreover, these are 2025-era numbers. Launch costs are declining. Space X's ambition is to reduce launch cost to

Starlink satellites make up the majority of the current 15,000 satellites in orbit, highlighting the dominance of commercial satellite constellations.

The Community Resistance Context: Why Orbiting Infrastructure Looks Good Right Now

To understand why Space X's proposal appeals to major cloud providers, you have to understand the community resistance problem facing terrestrial data center expansion.

Over the past 5 years, major cloud providers have faced escalating opposition to new data center construction. In Ireland, Meta and Google faced campaigns from environmental groups concerned about water consumption and carbon footprint. The government eventually imposed a multi-year moratorium on new data center development, affecting billions of dollars in planned infrastructure.

In Virginia, local governments initially welcomed the data center boom for tax revenue. Then power costs spiked, water stress became apparent, and communities realized they'd traded long-term environmental impact for short-term economic gain. New counties are now restricting new development.

Oregon blocked Meta's Prineville expansion. New Mexico restricted development in sensitive aquifer regions. The pattern is consistent: initial enthusiasm followed by organized community opposition.

This is a serious problem for cloud providers because their expansion plans are contingent on building new data centers. Without new sites, they can't deploy new AI capacity. Without new capacity, they lose competitive advantage in the AI arms race.

Orbital infrastructure, by contrast, faces no community opposition. No neighbors to upset. No local environmental committees. No water board complaints. This is its true strategic advantage.

International Coordination and Space Policy Implications

Space X's filing is unilateral—a U. S. company making a request to a U. S. regulator. But implementing a constellation of this magnitude has global implications that can't be ignored.

The Outer Space Treaty of 1967 (ratified by 112 nations including the U. S., Russia, China, and most spacefaring nations) establishes that space is "the province of all mankind." No nation can claim territory in space. But the treaty also specifies that nations are responsible for national space activities, whether carried out by governments or private companies.

This creates tension. Space X is a U. S. company, but its satellites operate in orbits that pass over every nation multiple times daily. If a Space X satellite collides with another nation's satellite, who's liable? If debris from a Space X collision injures someone on the ground, what jurisdiction applies?

These questions are currently unresolved. The FCC can approve Space X's filing, but implementation would immediately trigger international coordination challenges.

Europe, through the ESA, is developing its own orbital infrastructure policies. China has satellite constellations of its own. The emerging pattern is that orbital resources (spectrum, orbital slots, debris management responsibility) will need international negotiation.

A million-satellite constellation from a single U. S. company would likely violate the spirit of international space coordination, even if it satisfies the letter of existing treaties. Expect pushback from other spacefaring nations.

Timeline and Reality Check: When Might This Actually Happen?

Let's be realistic about deployment timeline. Even if regulatory approval somehow came through for a substantially reduced constellation (say, 100,000 satellites instead of one million), how long would actual deployment take?

Space X currently launches roughly 120-150 Falcon 9 rockets annually. Each rocket can carry roughly 50-60 data center satellites (assuming they're smaller than Starlink satellites, which already pack 53 per launch).

To deploy 100,000 satellites would require:

At current launch rates of 140 per year:

That's a 13-year deployment timeline even after regulatory approval. In reality, it would likely be longer because ramping manufacturing from current rates to required production volumes takes time.

For context, Starlink deployment started in 2019. As of 2025, roughly 7,000 satellites are deployed (targeting 12,000 total). That's six years for 7,000 satellites. Data center satellites are likely larger and more complex than Starlink internet satellites, which would slow deployment further.

A realistic estimate: if approved today, a meaningful orbital data center constellation (10,000-50,000 satellites) wouldn't reach operational capacity until 2035-2040.

That's a long time to wait in the AI computing cycle. GPU generations change every 1-2 years. AI model capabilities advance even faster. By 2035, the compute demands and architectures we're optimizing for today will be obsolete.

Estimated data suggests SpaceX could deploy up to 150,000 satellites by 2040, providing supplementary compute capacity. Estimated data.

Alternatives and Intermediate Solutions

While we're debating orbital data centers, more immediately practical solutions are being deployed.

Modular and Temporary Data Centers

Companies like Google and Amazon are deploying modular data center units that can be rapidly deployed and removed. These reduce environmental footprint compared to traditional facilities and face less community resistance because of their temporary nature. They're not as speculative as orbital infrastructure and can be deployed immediately.

Distributed Edge Computing

Rather than centralizing all compute in massive data centers, cloud providers are distributing compute to edge locations closer to users. This reduces latency and distributes resource burden. AWS Wavelength, Azure Edge Zones, and Google Cloud CDN all pursue this model.

Renewable Energy Integration

Instead of seeking new locations, existing data centers are integrating onsite renewable energy. Solar panels on data center roofs, wind turbines co-located with facilities, and power purchase agreements for renewable generation reduce operational emissions. This eliminates the "fossil fuel power" objection that drives some community opposition.

Liquid Cooling and Efficiency Improvements

Direct liquid cooling (where coolant flows directly over chips) reduces cooling overhead from 35% to 20-25%. Immersion cooling (submerging entire servers in dielectric fluid) pushes efficiency even further. These technologies are mature and deployable today, dramatically reducing water and energy consumption compared to traditional air cooling.

Water Recycling Systems

Closed-loop water recycling systems allow data centers to operate with minimal external water consumption. Wastewater is recycled and reused in cooling loops. This doesn't eliminate water consumption entirely but reduces it by 80-90%, which often satisfies community concerns.

These solutions are less romantically appealing than "data centers in space," but they're practical, deployable, and immediately addressing the community opposition problem.

What's Really Happening: The Strategy Behind the Filing

Step back and consider what Space X might actually be trying to accomplish with this filing. The proposal for one million satellites is likely not a serious execution plan. Instead, it's a strategic move with multiple simultaneous objectives.

First objective: Establishing orbital presence claims. By filing for satellite approval, Space X is claiming orbital real estate and spectrum slots. These are finite resources regulated by the ITU (International Telecommunication Union). Filing establishes Space X's priority for orbital slots that could eventually be used for data center constellations.

Second objective: Attracting partnership capital. If cloud providers (Amazon, Google, Microsoft) become convinced that orbital data centers are viable, they might fund development. A billion-dollar investment from AWS would accelerate Space X's orbital infrastructure timeline dramatically. The filing is positioning the company for such partnerships.

Third objective: Long-term optionality. Space technology and economics are changing rapidly. Launch costs declining, manufacturing improving, computational efficiency increasing—all favor orbital infrastructure eventually becoming viable. Space X is preserving the option to pursue this by establishing current regulatory claims.

Fourth objective: Technology development. Even if orbital data centers never deploy, the technologies developed (efficient thermal management, laser inter-satellite links, autonomous satellite operations) have military and commercial applications. The investment is justifiable on technology grounds alone.

From this perspective, the filing is rational even if deployment never materializes. Space X gains orbital claims, potential partnerships, and technology development advancement.

Environmental and Sustainability Assessment

Let's dig into the environmental claims more carefully, because they're central to the proposal's appeal.

Water Impact

The claim: orbital data centers eliminate water consumption.

Reality: This is true for direct operational water (cooling). But the full lifecycle has water impacts. Manufacturing satellites requires water-intensive industrial processes. Mining rare earth elements and semiconductor fabrication both consume substantial water. Rocket fuel production (liquid oxygen and methane for Space X's Starship) involves water-intensive processes.

A comprehensive lifecycle assessment would need to account for all of this. Eliminating operational water consumption is genuinely valuable, but doesn't mean zero total water impact.

Carbon Footprint

The claim: renewable solar power means zero operational emissions.

Reality: Again, partially true. Operating emissions are minimal. But launch emissions are substantial. A single Falcon 9 launch (roughly 200+ tons of rocket) generates several hundred tons of CO2 equivalent. Launching enough satellites to deploy one million constellation means thousands of launches—millions of tons of launch emissions.

A carbon payback analysis would compare launch emissions against terrestrial power generation emissions over the satellite's operational life. For shorter-mission satellites or high-carbon terrestrial electricity grids, this could be favorable. For longer-mission satellites or grids with substantial renewable generation, the payback might never occur.

Orbital Debris

The environmental claim here is speculative. Increased orbital congestion and debris risk are genuine environmental problems if they lead to catastrophic collisions. That's a hard-to-quantify but potentially severe environmental cost.

Cloud providers are highly interested in orbital data centers due to high compute demand, long construction timelines, regulatory delays, and sustainability benefits. Estimated data.

Comparison: Orbital Data Centers vs. Current Alternatives

| Approach | Water Use | Power Cost | Capital Cost | Deployment Time | Community Opposition | Latency Risk |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Terrestrial Traditional | 1-3M gal/day | $1.5-3M/year | $10-20M/MW | 18-24 months | Very High | <1ms |

| Terrestrial Modular | 200K-500K gal/day | $1-2M/year | $5-10M/MW | 6-12 months | Moderate | <1ms |

| Terrestrial Liquid Cooled | 50K-200K gal/day | $0.8-1.5M/year | $8-15M/MW | 12-18 months | Moderate-High | <1ms |

| Terrestrial Renewable | 500K-1M gal/day | $0.5-1M/year | $12-18M/MW | 18-24 months | Low-Moderate | <1ms |

| Edge Distribution | Minimal | $0.2-0.5M | $3-8M/MW | 6-12 months | Low | 1-5ms |

| Orbital Data Centers | Zero | ~$0 | $100-500M/MW | 7-13+ years | Zero | 2.6-5ms+ |

The Bigger Picture: Space Infrastructure Convergence

Orbital data centers aren't an isolated idea. They're part of a larger trend toward space-based infrastructure that includes communications (Starlink, Amazon Kuiper), Earth observation (Planet, Axiom), and scientific research satellites.

The convergence point is that these systems increasingly need to communicate and integrate with each other. Starlink satellites already carry optical inter-satellite links (lasers connecting satellite to satellite). Data center satellites would use similar technology. Over time, you get an integrated orbital infrastructure ecosystem where computational capacity, communications bandwidth, and sensing capabilities are all networked together.

This is genuinely interesting from a technology perspective. An orbital cloud computing network integrated with global broadband and Earth observation would have capabilities impossible with purely terrestrial infrastructure.

But it also represents an enormous concentration of critical infrastructure in the hands of a single company (Space X) or a small set of companies. That raises legitimate concerns about resilience, competition, and what happens if a catastrophic collision cascades through the entire system.

Regulatory Likely Outcomes and Feasibility Assessment

Here's my practical assessment of what will actually happen:

Most Likely Outcome (70% probability): FCC negotiates with Space X and approves a substantially reduced constellation: 50,000-150,000 satellites rather than one million. Space X begins limited deployment focused on non-interactive compute workloads (AI training, batch processing, data analytics). By 2035-2040, the constellation reaches ~100,000 deployed satellites, providing roughly 1-2 petaflops of additional compute capacity globally.

Optimistic Outcome (15% probability): Launch costs decline faster than expected due to Starship success. Space X achieves near-term regulatory approval for larger constellations. By 2032, they deploy 300,000+ satellites and demonstrate compelling economic case for orbital compute. Other companies (Blue Origin, Axiom) launch competing constellations.

Pessimistic Outcome (15% probability): Catastrophic collision in LEO triggers Kessler Syndrome cascades. International pressure and liability concerns force severe restrictions on new satellite deployments. Space X's orbital data center project is abandoned or severely scaled back.

The path forward is complex because it depends on technological progress (launch costs), policy decisions (international debris standards), and operational experience (how many collisions actually occur).

Preparing for Orbital Infrastructure: What Organizations Should Do Now

If you're at a cloud provider, enterprise IT organization, or infrastructure company, what should you do about orbital data centers?

Monitor developments closely. FCC filings, Space X announcements, and ESA policy statements will signal direction. Subscribe to space industry news sources and track regulatory timelines.

Develop technical expertise. Orbital computing will require different optimization approaches: different latency characteristics, power management constraints, and failure modes than terrestrial infrastructure. Build familiarity with space systems engineering now.

Don't depend on it for near-term plans. Your 2025-2028 expansion plans should assume terrestrial or edge infrastructure. Orbital compute is 2035+ timeframe.

Invest in alternatives aggressively. Liquid cooling, edge computing, renewable energy integration—these address the community opposition and environmental concerns driving interest in orbital alternatives. Execute them now rather than waiting for space-based solutions.

Evaluate partnerships. If your organization has unique capabilities (satellite manufacturing, orbital operations, launch services), consider how to position for potential orbital data center partnerships. Space X will likely seek partnerships with cloud providers and specialized contractors.

Use Case: Generating strategic infrastructure reports and competitive analysis documents that synthesize satellite data, orbit mechanics research, and regulatory intelligence to inform data center expansion decisions.

Try Runable For Free

The Deeper Questions: Is This Actually Progress?

Once you've understood the technical details and regulatory landscape, a more fundamental question remains: is orbital data center infrastructure actually a net positive for society?

There are genuinely compelling arguments on both sides.

The optimistic case: Orbital infrastructure eliminates water consumption, reduces emissions if solar power is superior to grid electricity, and breaks the political gridlock preventing data center expansion. This enables AI research and deployment that otherwise would be constrained by infrastructure limits. The computational capacity freed could accelerate medical research, climate modeling, and scientific discovery.

The pessimistic case: We're externalizing a terrestrial problem (environmental impact of computing) to space without fully understanding the consequences (orbital debris, collision risk, long-term space sustainability). We're concentrating critical infrastructure with a single company operating in a domain with minimal regulatory oversight. And we're doing this to maximize commercial AI deployment, which itself raises ethical questions about labor displacement, energy consumption, and AI safety.

Neither extreme is obviously correct. The reality is probably somewhere in the middle: orbital data centers will eventually happen in some form, but not at the scale or speed Space X's filing suggests. They'll address real problems (water consumption, community opposition, expansion limits) but create new ones (debris, concentration, latency constraints).

The most important thing is that this transition happens thoughtfully rather than accidentally. That requires international coordination on orbital debris standards, regulatory frameworks that account for long-term sustainability, and honest assessment of environmental impacts across the entire lifecycle.

Space X's filing is the opening move in this negotiation. Don't mistake the opening bid for the final answer.

FAQ

What is a Kardashev II civilization and why does it matter for this proposal?

A Kardashev II civilization is a theoretical society capable of harvesting the entire energy output of a star (approximately 3.8 × 10^26 watts for our Sun). Space X's filing references this to describe the long-term ambition of orbital infrastructure: eventually achieving civilization-scale access to solar power through orbital systems. While this is aspirational rather than a near-term engineering spec, it indicates Space X's vision extends beyond incremental improvements to terrestrial data centers. The reference signals thinking about fundamental infrastructure transformation rather than marginal optimization.

How does laser communication between satellites work and why is it important for orbital data centers?

Laser inter-satellite links transmit data using modulated light beams between satellites in orbit. Unlike radio-based communication that must bounce through ground infrastructure, laser links maintain direct satellite-to-satellite connections, reducing latency and avoiding terrestrial bandwidth constraints. For orbital data centers, this is critical because it allows a networked constellation to function as an integrated compute system: splitting workloads across multiple satellites, load-balancing based on local power availability, and aggregating results without returning all data to Earth. Without efficient laser inter-satellite communication, each satellite would operate independently with severe limitations.

What is the difference between LEO and other orbital altitudes and why does Space X choose LEO for data centers?

Low Earth Orbit (LEO) spans roughly 160-2,000 km altitude, Medium Earth Orbit (MEO) spans 2,000-35,786 km, and Geostationary Orbit (GEO) is at 35,786 km altitude. LEO offers multiple advantages: shorter round-trip communication delay (roughly 2.6 milliseconds versus much longer for higher orbits), more frequent revisit times for ground station access, and shorter orbital periods (90 minutes) that ensure regular eclipse periods for power management planning. However, LEO introduces faster orbital decay due to atmospheric drag, requiring periodic reboost. Space X chooses LEO for data centers because the latency and frequency trade-offs work well for the proposed use cases.

Why would companies choose orbital data centers if latency is worse than terrestrial facilities?

Orbit makes sense for workload categories where latency is less critical: model training (no latency constraint), batch data processing (delays acceptable), and research computing (interactive response not required). These workloads are actually substantial portions of current cloud provider revenue. Additionally, as orbital capacity scales, you might have scenarios where the nearest available compute is orbital rather than terrestrial, making latency trade-off worthwhile for time-critical applications. The key is that not all cloud workloads require sub-millisecond latency—only interactive user-facing applications do.

How does the deorbiting requirement work and why is it challenging for orbital data centers?

Deorbiting requires commanding a satellite to fire thrusters, lowering its orbit until it re-enters Earth's atmosphere and burns up. This needs to happen at end-of-life to prevent long-term orbital debris accumulation. For a single satellite, this is straightforward. For one million satellites, deorbiting becomes a massive operational logistics challenge: ensuring every single satellite remains operational enough to perform deorbiting, coordinating simultaneous or sequenced deorbiting to avoid congestion in the reentry corridor, and managing inevitable failures where some satellites can't deorbit and remain as debris. A 1% failure rate means 10,000 permanent debris pieces, which is significant.

What is space junk and how does it relate to orbital data center proposals?

Space junk (orbital debris) includes defunct satellites, spent rocket stages, fragments from collisions, and other human-made objects in orbit. Currently roughly 100 million pieces exist larger than 1mm, with 34,000 trackable pieces larger than 10cm. At orbital velocities (7.8 km/s for LEO), even tiny debris is destructive. More satellites mean more potential collision sources, which generates more debris, creating exponential risk (Kessler Syndrome). A constellation of one million satellites would dramatically increase collision probability, especially if any significant failures prevent proper deorbiting.

When could orbital data centers realistically begin operations and what would be the timeline for meaningful capacity?

If regulatory approval came tomorrow and Space X achieved current launch rates, deploying 100,000 operational data center satellites would take roughly 13 years. More realistically, factoring in manufacturing ramp-up, launch rate increases, and regulatory delays, you're looking at 2035-2040 before substantial orbital data center capacity exists. In AI time, that's an eternity—current GPU generations are 18-24 month cycles. By then, the compute architectures and AI models we're optimizing for today will be obsolete. This timeline is why orbital solutions matter more for long-term capacity planning than near-term infrastructure gaps.

How do environmental claims about orbital data centers hold up under scrutiny?

The claim of zero water consumption is accurate for operations but ignores lifecycle water impacts (manufacturing, mining, fuel production). The zero-emission claim is partially true for operations but ignores substantial launch emissions—thousands of rockets mean millions of tons of CO2 equivalent. A true environmental assessment requires lifecycle analysis comparing all impacts (water, carbon, materials, debris) against terrestrial alternatives. The honest answer: orbital likely has lower operational environmental footprint but higher embodied environmental cost, and the comparison is complex enough that definitive claims either way are premature.

Conclusion: The Reality Behind the Headlines

Space X's filing for one million orbital data center satellites is simultaneously impossible, speculative, strategically brilliant, and genuinely interesting—sometimes all at the same time.

It's impossible in the sense that regulatory approval for a million satellites won't happen. The orbital debris risk, international coordination challenges, and sheer operational complexity make it unrealistic.

It's speculative because it depends on technologies (efficient orbital cooling, reliable satellite operations, economic launch costs) that aren't fully proven at scale.

It's strategically brilliant because it establishes orbital claims, attracts partnership interest, and develops technologies with applications far beyond data centers. Even if orbital compute never becomes economically viable, the technologies developed are valuable.

And it's genuinely interesting because if even 5-10% of the proposed constellation materializes, it represents a meaningful new category of infrastructure with real implications for cloud computing, space sustainability, and how we'll structure computing in the future.

The actual trajectory is almost certainly something like this: Space X negotiates with the FCC for approval of a smaller constellation (50,000-150,000 satellites). They begin deployment around 2027-2030, targeting batch processing and model training workloads first. By 2035-2040, roughly 100,000+ satellites are operational, providing meaningful supplementary compute capacity. They operate profitably in specific use cases but never completely replace terrestrial data centers.

Meanwhile, terrestrial alternatives (modular units, edge computing, renewable integration, liquid cooling) advance in parallel, capturing the near-term growth in AI infrastructure demand. The orbital and terrestrial systems coexist and eventually integrate into a hybrid global compute infrastructure.

What makes this more interesting than traditional data center expansion is that it forces us to think about computing infrastructure at a scale and scope we haven't really considered before. How do you manage global compute as a utility when it's distributed across terrestrial and orbital resources? How do you optimize workload placement when some capacity is in space with different latency and power characteristics? What does resilience mean when critical infrastructure depends on avoiding orbital collisions?

These aren't trivial questions, and Space X's filing is forcing the entire industry to grapple with them.

The next few years will be telling. Watch the FCC's response, follow Space X's actual deployment rate, and monitor whether any major cloud providers make public commitments to orbital compute. The gap between the filing request and regulatory reality will show us how seriously different stakeholders take this vision.

For now, don't wait for orbital data centers to solve your infrastructure problems. The technology is real, the opportunities are genuine, but the timeline is measured in decades, not years. Build your terrestrial infrastructure, optimize your edge strategies, and invest in efficiency improvements. Orbital compute will be there eventually—but when you need new capacity, it's going to come from much more earthbound sources.

Key Takeaways

- SpaceX's one million satellite filing is likely a negotiating anchor; realistic approval would be 50,000-150,000 satellites enabling meaningful but not transformative compute capacity

- Orbital data centers eliminate water consumption and enable renewable solar power, addressing legitimate environmental concerns driving community opposition to terrestrial facilities

- Latency disadvantage (2.6ms round-trip vs <1ms terrestrial) limits orbital infrastructure to non-interactive workloads like model training and batch processing, not real-time AI inference

- Space debris risk increases dramatically with orbital density; a catastrophic collision could trigger Kessler Syndrome cascades that render entire orbital regions unusable

- Realistic deployment timeline of 2035-2040 means orbital compute addresses long-term capacity planning, not near-term infrastructure gaps that terrestrial and edge solutions solve faster

Related Articles

- SpaceX's Million-Satellite Orbital Data Center: Reshaping AI Infrastructure [2025]

- SpaceX and xAI Merger: What It Means for AI and Space [2025]

- NASA Used Claude to Plot Perseverance's Mars Route [2025]

- Saudi Arabia's The Line Transforms into AI Data Centers [2025]

- Declassified JUMPSEAT Spy Satellites: Cold War Signals Intelligence Revealed [2025]

- AI Data Centers Drive Historic Gas Power Surge [2025]

![SpaceX's Million Satellite Data Centers: The Future of Cloud Computing [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/spacex-s-million-satellite-data-centers-the-future-of-cloud-/image-1-1769890027750.jpg)