The Password Manager Paradox: Your Digital Vault Might Not Be as Secure as You Think

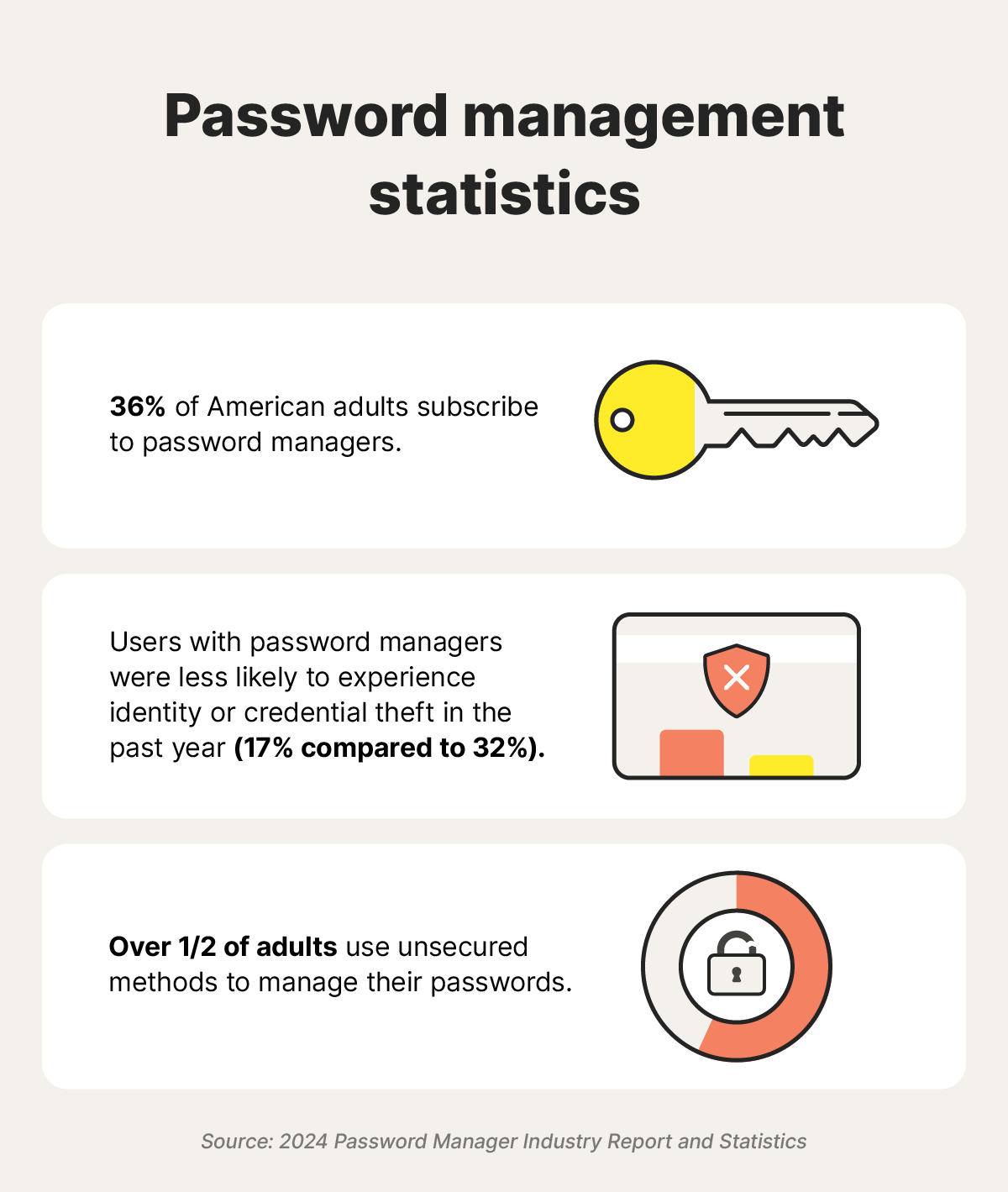

There's a cruel irony at the heart of modern cybersecurity. We tell people to use password managers—to stop reusing passwords, to stop writing them on sticky notes, to embrace the future of credential management. And it's good advice. Really good advice. A randomly generated 16-character password is objectively better than "My Dog 2024!" across 47 different sites.

But here's what keeps security researchers up at night: the very tool designed to protect your passwords might be the single point of failure that exposes every account you own.

In late 2024, researchers from some of Europe's most prestigious security institutions published findings that should have set off alarm bells across the industry. Their message was simple but terrifying: the "zero knowledge" encryption that password manager companies promise doesn't always work the way customers think it does. In some cases, it doesn't work at all.

We're not talking about theoretical attacks that require a quantum computer and a decade of compute time. These vulnerabilities are practical. Exploitable. Some of them exist in the current versions of platforms you're probably using right now. And they expose a fundamental truth about security in 2025: convenience and cryptographic security are still at war with each other.

This isn't a reason to panic and abandon password managers entirely. But it is a reason to understand what's actually happening with your credentials when you trust them to these services. Because the difference between "secure" and "supposedly secure" might be the only thing standing between your identity and a criminal's hands.

TL; DR

- Major password managers (Bitwarden, Dashlane, Last Pass) contain cryptographic flaws that could expose entire credential vaults under certain conditions

- "Zero knowledge" claims are not always true: researchers found ways to access passwords even when providers claim encryption prevents it

- Key escrow features (password recovery functions) create backdoors that attackers can exploit if they gain access to the company's infrastructure

- The vulnerabilities are simple enough to exploit that they've likely been discovered and abused before public disclosure

- Your best defense: enable two-factor authentication, use strong master passwords, and understand what "zero knowledge" actually means (and what it doesn't)

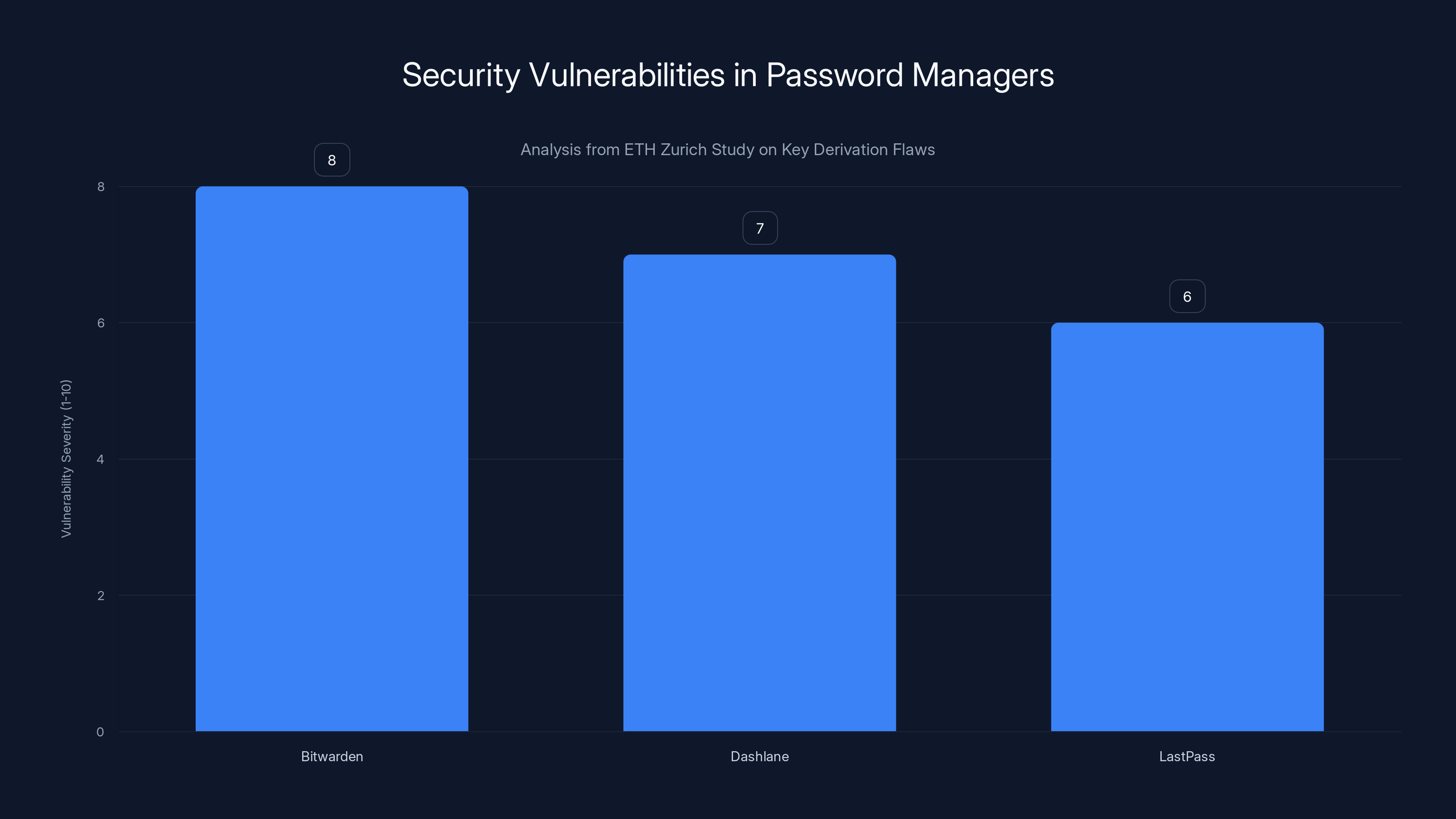

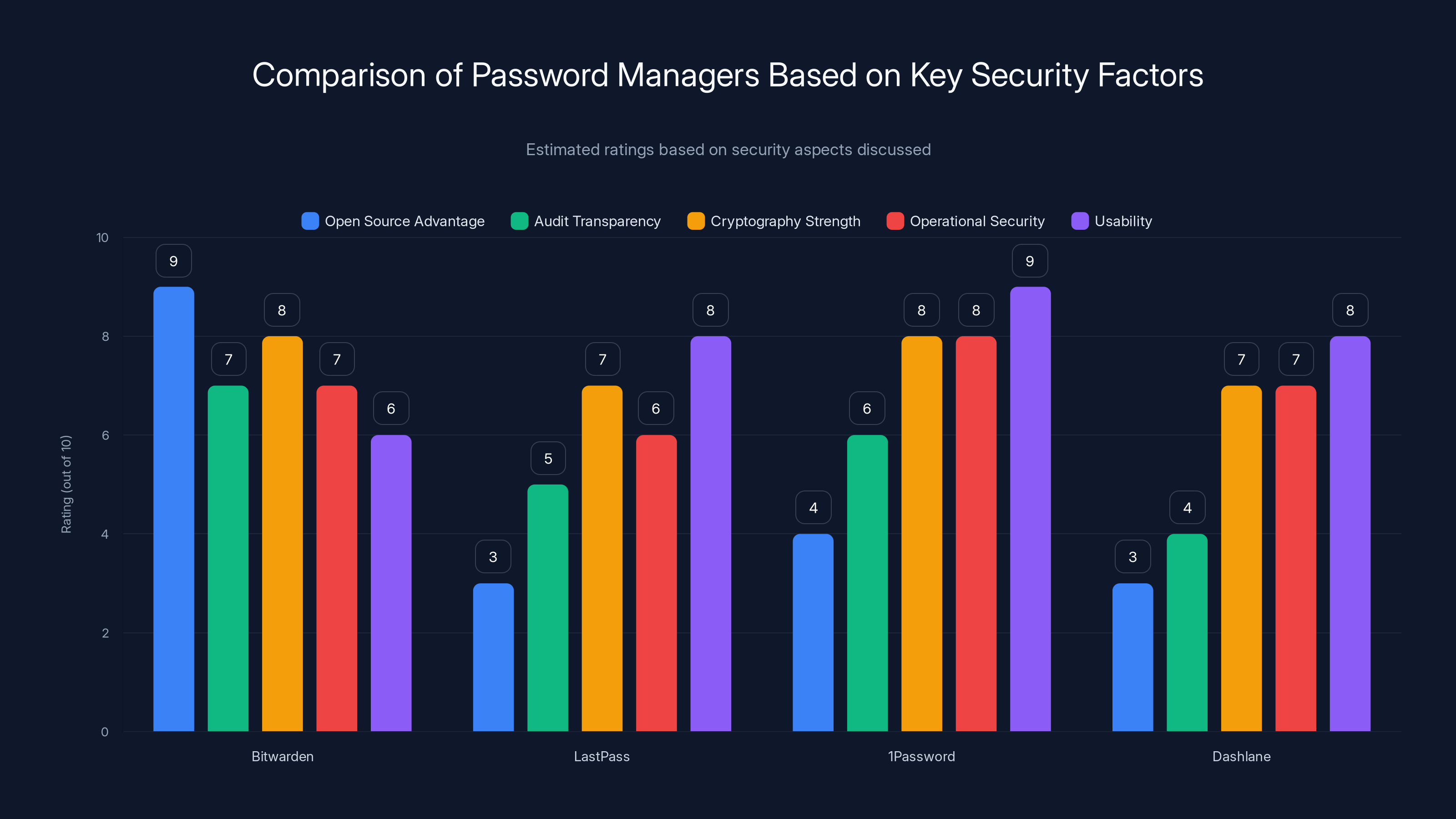

The ETH Zurich study revealed significant vulnerabilities in major password managers, with Bitwarden showing the highest severity due to key derivation flaws. Estimated data based on study context.

Understanding the "Zero Knowledge" Promise

Before we dive into what's broken, you need to understand what's supposed to work.

Password managers operate on a promise that sounds almost magical: "Your data is encrypted so thoroughly that even we can't access it." In technical terms, this is called zero knowledge architecture. The company stores your encrypted credentials, but only you have the key to decrypt them. The servers hold the vault, but they're just glorified filing cabinets with no ability to open the drawers.

This is different from most web services. Your email provider (even the privacy-focused ones) can technically access your messages because they control both the encryption and the keys. Your cloud storage might be encrypted, but the company that runs it can still see what's inside if they decide to look.

Password managers, theoretically, can't do this. The encryption and decryption happen entirely on your device, before anything leaves your computer or phone. The company's servers never see your unencrypted passwords. They never see your master password. They see only encrypted gibberish that would take longer to crack than the heat death of the universe.

Theory, though, is where perfection lives. Reality is messier.

The problem starts with a simple practical need: what happens when you forget your master password? If it's truly impossible for anyone (including the company) to decrypt your vault, then a forgotten password means losing everything forever. That's a terrible user experience. It's also bad for business—customers who lose access to their credentials will switch to competitors.

So password managers invented a feature called key escrow. In essence, they keep an encrypted copy of your decryption key on their servers. If you forget your master password, you can prove your identity through recovery codes or other verification methods, and they'll give you back the key to your encrypted vault.

It sounds reasonable. It's also where the entire security model begins to fracture.

The ETH Zurich Study: When Theory Meets Reality

In November 2024, security researchers from ETH Zurich (one of the world's top cryptography research institutions) and USI Lugano published a paper titled "Cryptographic Analysis of Password Managers." It was thorough. It was methodical. And it was deeply uncomfortable reading for three of the major players in the password manager industry.

The research team analyzed Bitwarden, Dashlane, and Last Pass. They looked specifically at how these companies implemented their zero-knowledge claims. And they found that the emperor had no clothes.

The Bitwarden Vulnerability

Bitwarden, an open-source password manager that many in the security community recommend specifically because its code is public and auditable, contains flaws in how it generates and manages the keys that encrypt users' vaults.

The researchers found that Bitwarden's implementation of key derivation functions—the cryptographic process that converts your master password into the actual encryption key—contained a critical flaw when certain cloud features were enabled. Specifically, the library Bitwarden uses for encryption didn't properly implement proper key management, leaving room for attackers to compromise the master key without ever knowing your master password.

What made this particularly troubling was that the vulnerability wasn't exotic. It wasn't a theoretical attack that required advanced cryptographic knowledge. It was the kind of implementation error that any competent engineer should have caught during code review.

The Dashlane Problem

Dashlane's vulnerabilities were different in nature but equally concerning. The researchers found that Dashlane's key escrow system—that recovery mechanism for forgotten passwords—contained fundamental cryptographic weaknesses.

Specifically, the way Dashlane stores the recovery key on their servers could potentially allow an insider threat or a sophisticated attacker to reconstruct users' master encryption keys. The researchers demonstrated that with access to certain server files, an attacker could derive the keys needed to decrypt entire password vaults.

What's particularly alarming about Dashlane's case is that the company has positioned itself as a security-first solution, especially for enterprise customers. If a criminal gains access to Dashlane's infrastructure, they wouldn't just get one person's passwords—they could potentially unlock the vaults of hundreds of thousands of users simultaneously.

The Last Pass Legacy

Last Pass's position in this research is complicated by its history. The company suffered a major security breach in 2022 where attackers gained access to customer vault backups. Last Pass claimed that the backups were encrypted and therefore useless to the attackers.

The ETH Zurich researchers found that while Last Pass's encryption is generally stronger than the other two, the company's implementation of the key escrow system—particularly when certain backup and recovery features are enabled—opens doors for attackers.

When you combine this with the 2022 breach and subsequent disclosures about what attackers actually accessed, a clear picture emerges: the gap between what Last Pass claims about its security and what it actually provides might be wider than many users realize.

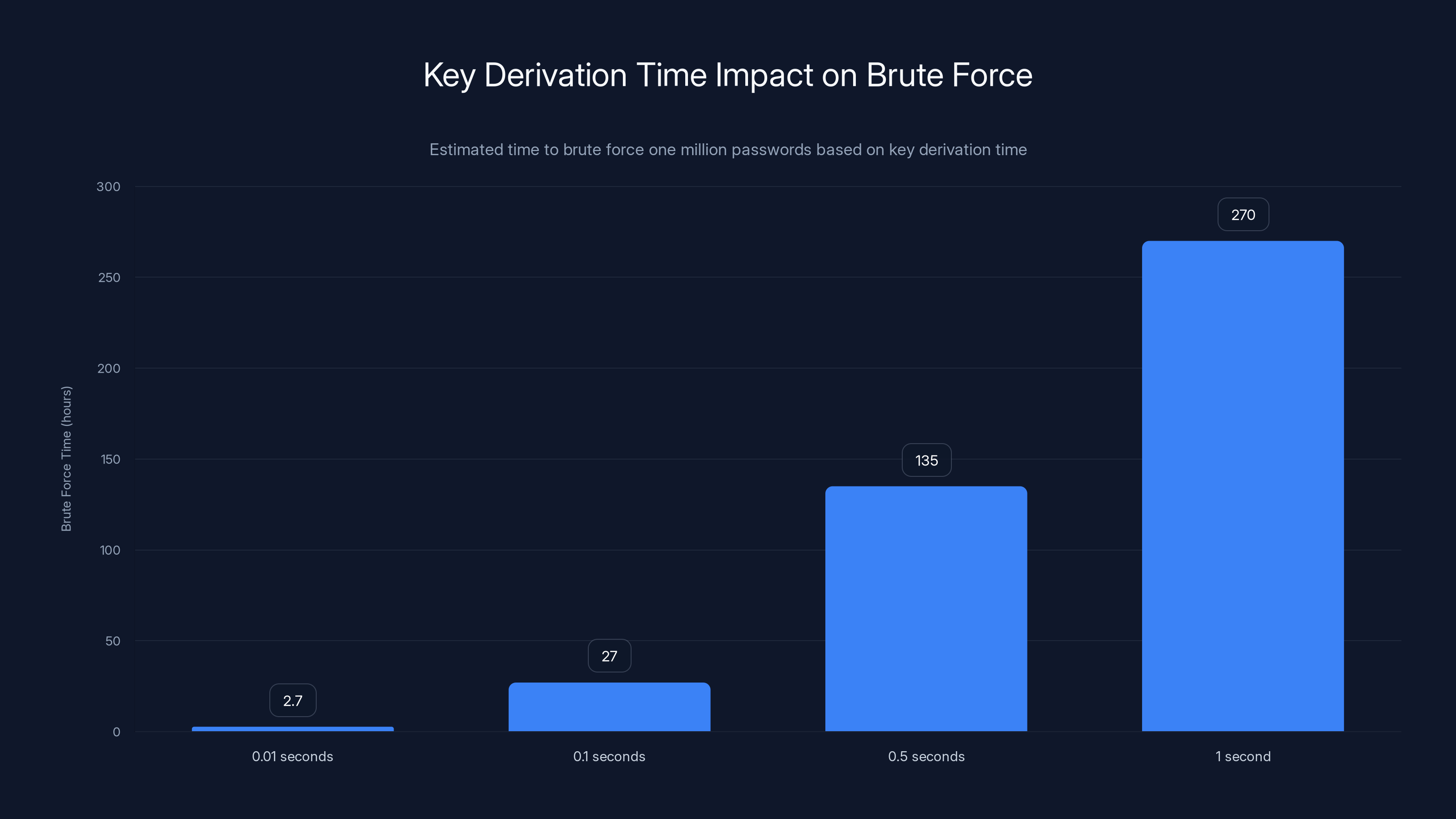

Longer key derivation times significantly increase the time required to brute force passwords, enhancing security. Estimated data.

How These Vulnerabilities Actually Work

Understanding the technical details isn't just academic. It helps you understand why the threat is real.

The Key Escrow Attack Path

Let's walk through a practical scenario. You use a password manager with key escrow enabled (this is the default or semi-default for Dashlane and Last Pass). Here's what happens:

- Your master password gets hashed using a key derivation function to create a master encryption key

- This encryption key encrypts all your passwords in what's called your vault

- The vault is stored encrypted on the company's servers

- But the encryption key itself is also encrypted using a secondary key and stored on the company's servers (this is the key escrow)

- The secondary key that encrypts the escrow key uses additional factors like your username and a server-side value

Now, if an attacker gains access to the password manager company's infrastructure, they have the encrypted vault and the encrypted escrow key. They might not have your master password, but they can try to brute-force the secondary encryption. Or, if they have insider access, they can potentially reconstruct the keys mathematically without ever guessing your password.

The researchers showed that in several cases, the secondary encryption was weak enough that with moderate computational resources, a determined attacker could crack it in days or even hours.

The Insider Threat Vector

The researchers also explored what a malicious insider at a password manager company could accomplish. Here's where things get really dark.

If someone with legitimate access to the company's servers—a database administrator, a security engineer, a contractor—decides to steal data, they don't need to crack encryption. They can simply observe where the keys are stored, what the key derivation parameters are, and potentially intercept unencrypted material during legitimate operations.

One particularly concerning finding was that several password managers store enough information on their servers that an insider could potentially create a decryption tool that works for multiple users or even all users. It's not about cracking individual passwords. It's about stealing the master keys that unlock everything.

Historically, this threat has been dismissed as theoretical. But the 2022 Last Pass breach and other incidents have shown that password manager companies can and do suffer from insider threats and sophisticated attackers who maintain deep access to infrastructure for months or years.

The Specific Vulnerabilities Explained

Let's get into the actual technical problems the researchers identified.

Weak Key Derivation Parameters

One of the simplest findings was also one of the most damning: several password managers didn't use sufficiently expensive key derivation functions.

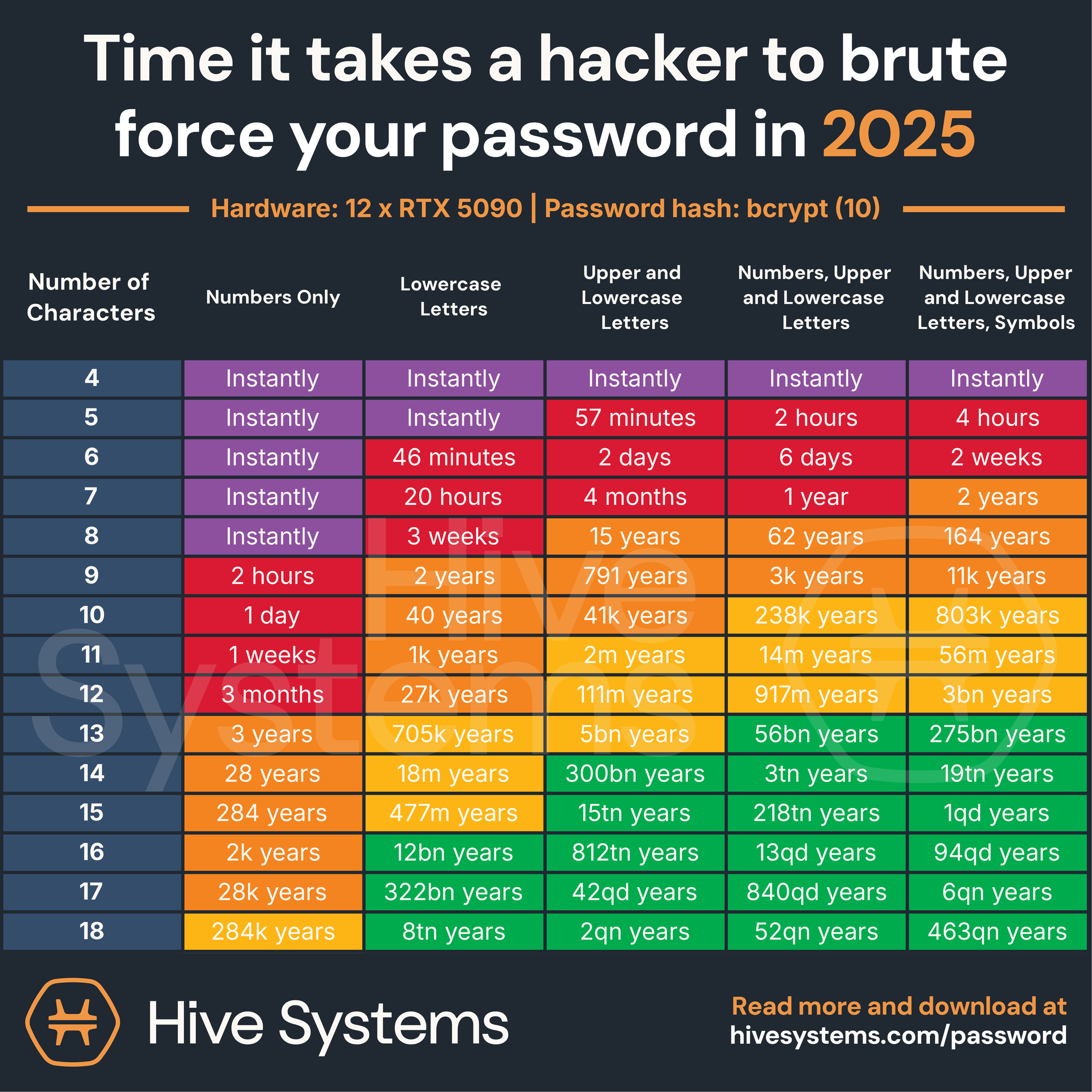

When you create a password manager account, your master password gets converted into an encryption key through a process called key derivation. This process is supposed to be slow—intentionally, deliberately slow. A modern secure implementation should take at least 0.1 seconds or more on your device.

Why slow? Because it makes brute-forcing harder. If deriving a key takes 0.1 seconds, then testing one million potential passwords takes 27 hours of computing. If it takes 1 second, it takes 11 days. This forces attackers to do large amounts of work.

The researchers found that some implementations used parameters that were either outdated or not aggressive enough, meaning the key derivation was faster than it should be. In the context of a compromised database with thousands of vaults, this could mean an attacker could test millions of master passwords in a reasonable timeframe.

Improper Separation of Concerns

Good cryptographic design follows a principle called "separation of concerns." Different keys should be used for different purposes. Your encryption key should be different from the key that signs your requests to the server. Your authentication credential should be completely separate from your encryption material.

Several implementations violated this principle. In some cases, the researchers found that the same key material or derived values of the same key material were used for multiple purposes. This is dangerous because if one key is compromised or leaked through one channel, it potentially compromises multiple security mechanisms simultaneously.

It's like using the same password for your email and your bank account. You're concentrating risk. A breach at one place cascades to another.

Recovery Mechanisms That Skip Encryption

One of the most troubling findings involved password recovery features. In certain scenarios—particularly when using cloud synchronization features or account recovery—some password managers would temporarily store keys in forms that were either weakly encrypted or encrypted with keys that could be derived from information stored on the company's servers.

The researchers demonstrated that they could force these recovery paths and potentially recover keys without ever knowing the user's master password. Some of these attack paths required either insider access or a very thorough compromise of the company's infrastructure, but others could potentially work from the outside.

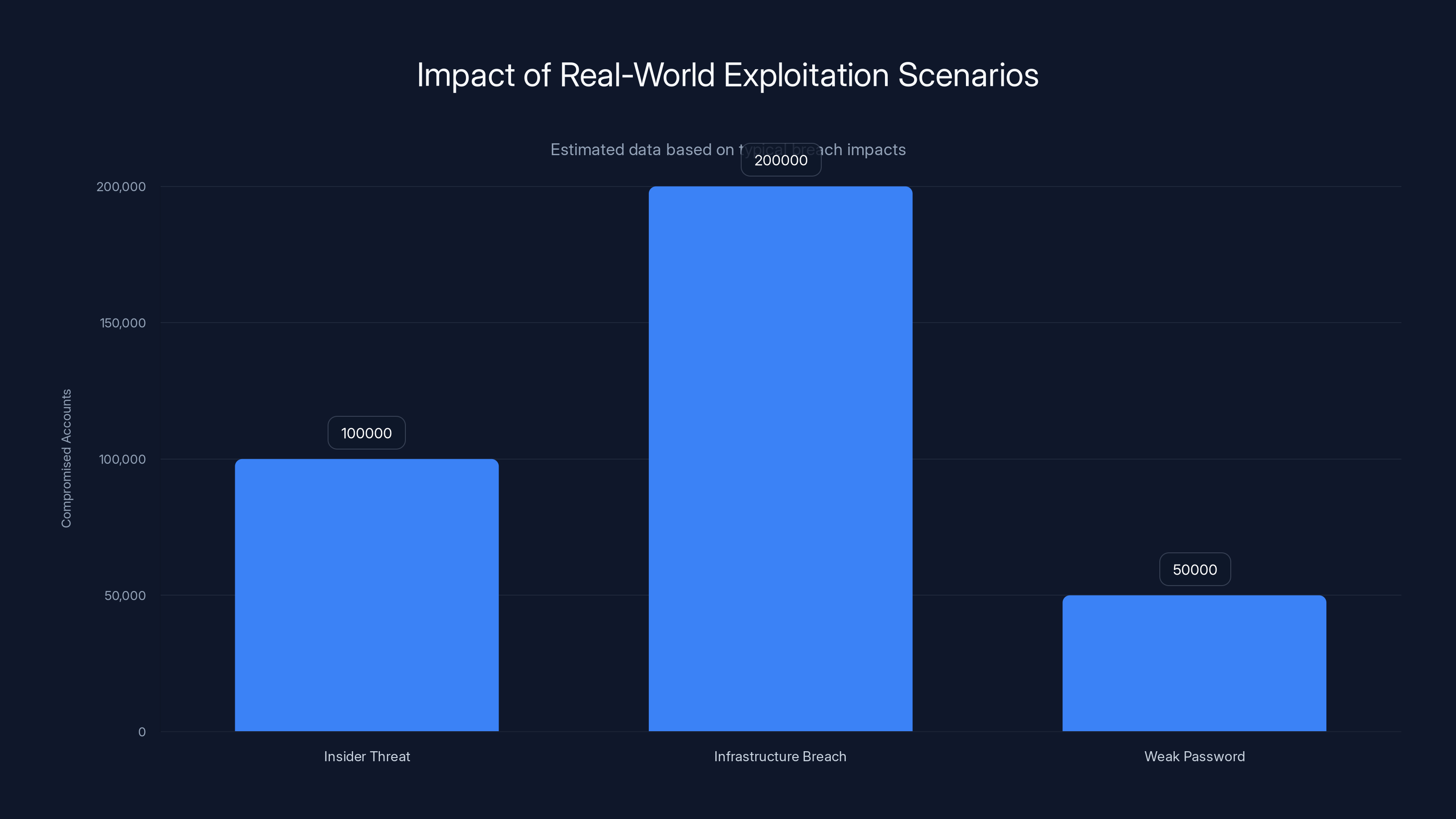

Real-World Exploitation Scenarios

Now let's talk about what this actually means in practice.

The Insider Threat Scenario

A contractor at a password manager company is hired for a legitimate reason: maybe to help with server migration, maybe to fix a bug in the cloud infrastructure. Over the course of months, this person develops a tool that can extract encryption keys from the company's database. They steal 100,000 encrypted vaults along with the key material.

They disappear. Months later, the vaults start being decrypted. By the time the password manager company realizes what happened, tens of thousands of accounts across multiple services have been compromised. The attackers have already used the stolen credentials to access bank accounts, email addresses, and corporate systems.

Is this scenario plausible? Absolutely. Similar scenarios have happened in the real world multiple times.

The Infrastructure Breach Scenario

A sophisticated nation-state or organized crime group gains access to a password manager company's infrastructure through a vulnerability in a third-party tool or service. They maintain access for weeks while they systematically map out how encryption is implemented.

They discover that the key escrow system, while encrypted, uses a secondary key that depends heavily on information stored in other database tables. Through careful analysis and brute-forcing, they reconstruct the secondary keys.

Now they can decrypt the escrowed encryption keys for hundreds of thousands of users. They copy the encrypted vaults, extract them along with the now-decrypted encryption keys, and exfiltrate everything. Months later, when they start selling access to these vaults on dark web markets, the password manager company realizes the scope of the disaster.

Is this plausible? The 2022 Last Pass breach demonstrates it absolutely is.

The Weak Master Password Scenario

Someone chooses "correct horse battery staple" (yes, that classic xkcd password) as their master password. It seems random, seems strong. But it's vulnerable to dictionary attacks that combine common words.

With the weak key derivation parameters the researchers found in some implementations, testing a dictionary of millions of common passwords becomes feasible. An attacker with access to the encrypted vault could crack the master password in weeks rather than centuries.

This reveals another uncomfortable truth: the password manager's security is only as strong as your weakest decision. Even perfect cryptography can't save you if your master password is guessable.

Estimated data shows that infrastructure breaches can potentially compromise more accounts than insider threats or weak passwords. Estimated data.

Why These Vulnerabilities Exist

Understood one level deeper, these vulnerabilities aren't really surprises. They exist because of fundamental tensions in password manager design.

The Convenience Trap

Password managers need to be convenient. If they're not convenient, people won't use them. They'll go back to reusing passwords or writing them down.

Convenience often means features like password recovery, cloud sync, and multiple device support. Each of these features inherently weakens the security model slightly. You're trading absolute theoretical security for practical usability.

The question is: how much trade-off is acceptable? The ETH Zurich research suggests that some password managers have traded away more security than necessary for their target use case.

The Open Source Illusion

Bitwarden markets itself heavily on the fact that its code is open source. The security community has long held that "many eyes make all bugs shallow"—that public code is more secure because more people can review it.

But this assumes that many eyes are actually looking. In reality, security code review is hard. It requires specific expertise. Most open-source projects don't have a dozen cryptography experts examining every line of code. They have whoever is willing to volunteer.

For Bitwarden specifically, the vulnerabilities existed in production code for months or years before being discovered in this research. That's not because the code was reviewed and approved. It's because cryptography is hard and the security community's review capacity is limited.

The Enterprise Compromise

Dashlane and Last Pass both serve enterprise customers. Enterprise customers need features like admin panels, user management, emergency access, and compliance reporting. Each of these features introduces additional code paths, additional key material, and additional places where security can degrade.

The researchers found that many of the vulnerabilities appeared specifically when these enterprise features were enabled. It's not that the companies did something obviously wrong. It's that they built complex systems to serve complex needs, and complexity is the enemy of security.

Cryptographic Weakness vs. Practical Risk

Here's where we need to be careful about interpretation.

The ETH Zurich researchers found cryptographic vulnerabilities. These are real technical flaws. But the question of whether these flaws translate into practical attacks is more nuanced.

Some of the vulnerabilities they discovered would require an attacker to have already compromised the password manager company's infrastructure. If an attacker has already gotten that deep into your password manager's servers, the integrity of your password manager security is kind of secondary to the fact that you've already lost.

Other vulnerabilities are more concerning because they could potentially be exploited by determined attackers without necessarily compromising the entire infrastructure—they'd just need to compromise specific database tables or steal specific key material.

The real issue is that password manager companies are making claims about their security that the technical details don't fully support. They claim "zero knowledge architecture" and "end-to-end encryption" and "we can't access your passwords." The research shows these claims are more nuanced than the marketing suggests.

Under normal circumstances, with normal threats, using a major password manager is still more secure than the alternatives. But under specific circumstances—particularly insider threats, sophisticated attackers, and the presence of certain enabled features—the security degradation is real.

What Password Manager Companies Are Doing

After the ETH Zurich findings were published, the affected companies responded in different ways.

Bitwarden's Response

Bitwarden took the findings seriously and committed to fixing the identified issues. The company acknowledged that the vulnerability in their key derivation implementation was a genuine problem and worked on patches.

Being open source, Bitwarden has some advantages here. The fixes are visible to anyone who cares to look, and the community can verify that the changes actually address the problems.

However, fixes take time to deploy. Users need to update their clients. Servers need to be patched. There's a window where vulnerable versions are still in use.

Dashlane's Approach

Dashlane's response was more defensive. The company argued that the vulnerabilities the researchers identified would require specific preconditions (like compromised infrastructure) and that their overall security model is still sound.

They're not entirely wrong—many of the Dashlane vulnerabilities do require assumption of compromise at a deeper level. But this response also illustrates a broader problem: companies are defending against the research rather than engaging with the substance of the technical findings.

Last Pass's Position

Last Pass has a complicated history with security research. After the 2022 breach, the company made several security commitments. The discovery of additional vulnerabilities in their key escrow system suggests that some of these commitments haven't fully addressed underlying architectural issues.

The company has since announced plans to migrate to new infrastructure and improve key management, but rollouts of these changes take time.

This chart provides an estimated comparison of popular password managers based on open source advantage, audit transparency, cryptography strength, operational security, and usability. Estimated data.

The Broader Ecosystem Problem

What's particularly concerning about these findings is that they're probably not unique to these three companies.

The researchers specifically noted that "while we analyzed Bitwarden, Dashlane, and Last Pass, our findings likely apply to other password managers as well." In other words, the cryptographic problems they found are symptomatic of how the entire industry approaches password manager security.

This suggests that if you're using 1 Password, Kee Pass, or any other major password manager, similar vulnerabilities might exist. We just haven't published detailed analysis of them yet.

The password manager industry has been relatively immune to scrutiny compared to other security software. Most password managers don't undergo regular independent security audits. Many rely on bug bounty programs rather than comprehensive code reviews.

How Strong Is Your Master Password Really?

In the context of these vulnerabilities, your master password becomes more important than ever.

Remember: if an attacker has access to your encrypted vault and sufficient computing power, they'll try to crack your master password by testing millions of possibilities. The difficulty of this task depends entirely on how strong your master password is.

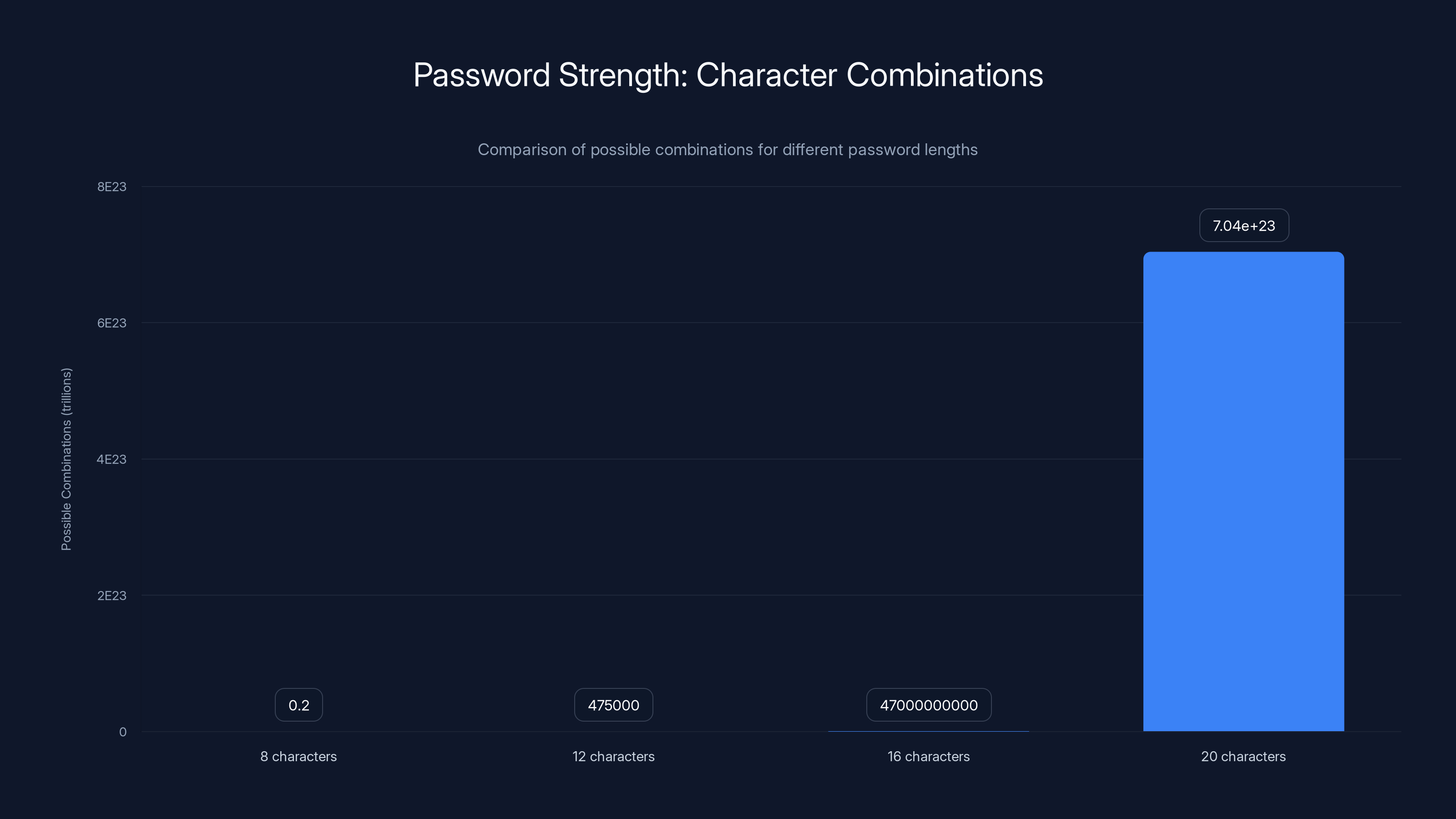

Consider the math. A 12-character password using lowercase, uppercase, numbers, and symbols gives you roughly

A 20-character password using the same character set gives you roughly

But here's the critical part: this only works if your master password is truly random. If it's composed of recognizable words or patterns, it becomes vulnerable to dictionary attacks and pattern-based cracking. Your brain can't reliably generate randomness. You need a password generator for this.

The practical implication: if you've chosen your master password yourself, and it has any words or patterns you can actually remember without writing down, it's probably vulnerable to dictionary attacks even with strong key derivation functions. Your password manager is only as strong as your ability to choose a truly random 20+ character master password.

Two-Factor Authentication: The Overlooked Line of Defense

One thing the cryptographic vulnerabilities don't account for: two-factor authentication at the password manager account level.

If your password manager account (not just your master password, but your actual account with the company) has two-factor authentication enabled, then an attacker needs two things to gain access: your master password (or the ability to derive it) and physical access to your second factor (typically your phone).

Two-factor authentication doesn't prevent a database breach. It doesn't stop cryptographic vulnerabilities. But it does make the attack exponentially harder. An attacker who steals an encrypted vault and attempts to crack your master password can do that completely offline. An attacker who tries to log into your account still needs your second factor.

This is a critical line of defense that's often overlooked. Most password manager users don't enable two-factor authentication on their password manager accounts. They figure if the encryption is good enough, they don't need it. These vulnerabilities suggest otherwise.

Every major password manager now supports two-factor authentication. If yours supports it and you haven't enabled it, you should. Today. Right now. Go enable it.

A 20-character password offers exponentially more combinations than shorter passwords, making it significantly more secure against brute-force attacks. Estimated data based on character set possibilities.

Which Password Manager Should You Trust?

This is the question everyone wants answered, and it's frustratingly complicated.

The Open Source Advantage

Bitwarden's major selling point is that its code is open source. You can see exactly what it's doing. You can compile it yourself if you want. You can contribute security patches.

The vulnerability findings don't change the fact that open source is fundamentally better for security review. But the findings do reveal that being open source isn't sufficient protection. You also need active security expertise in your community.

The Audit Question

Several password managers claim to have undergone independent security audits. These audits are valuable but not perfect. An audit at a point in time shows what was secure at that moment. New vulnerabilities can emerge afterward. Features added after an audit might not have the same security scrutiny.

Audit reports should be public and detailed, not just a passing mention that an audit was done. Look for companies that publish full reports or detailed summaries of what was tested and what was found.

The Operational Security Reality

Here's what ultimately matters: a password manager's security depends on:

- The strength of its cryptography

- The quality of its implementation

- The operational security of the company running it

- The trustworthiness of everyone with access to the company's infrastructure

- Your own behavior in using it

No single password manager wins on all five dimensions. Different companies make different trade-offs. The question isn't which one is perfect (none of them are). The question is which one's trade-offs align with your threat model.

If you're worried about insider threats at large corporations, an open-source option with peer review might be better. If you're worried about usability and recovery, accepting slightly less cryptographic purity for practical features might be reasonable.

The Threat Model Question

Before deciding on a password manager, you need to understand your actual threat model.

Who is likely to target your accounts? Is it random cybercriminals? A sophisticated nation-state? A jealous ex? Someone trying to steal specific confidential information?

For most people, a major password manager (yes, even given these vulnerabilities) provides vastly more security than the alternatives. The alternative isn't some theoretically perfect password manager. The alternative is writing passwords down, reusing passwords, or storing them in a spreadsheet.

The vulnerabilities discovered in this research are concerning. They're worth fixing. But they don't suddenly make password managers insecure.

What they do is remind us that real-world security is always a compromise between protection, convenience, and usability. There's no such thing as perfect security. There's only better security relative to the alternatives.

The Broader Implications for Internet Security

These vulnerabilities reveal something uncomfortable about modern cryptographic systems: they're only as good as their implementation.

We have mathematically sound encryption algorithms. We have well-understood cryptographic principles. We know how to build secure systems in theory. But implementing these systems at scale, across multiple platforms, while maintaining usability, while dealing with legacy constraints, and while a company is trying to make money—that's where everything gets messy.

Password managers are sophisticated software. They manage encryption keys, they synchronize data across multiple devices, they provide recovery mechanisms, they integrate with browsers and mobile operating systems. Each of these adds complexity. Each adds attack surface.

The lesson for the broader security industry: marketing claims about security ("zero knowledge," "end-to-end encrypted," "unhackable") need to be matched by technical reality. And that reality should be subject to independent verification.

For password manager users: the existence of these vulnerabilities doesn't mean you should abandon password managers. It means you should be thoughtful about which one you use, how you configure it, and what additional security measures you layer on top.

Password managers incorporate complex features, each adding potential vulnerabilities. Estimated data based on typical feature complexity.

Key Takeaways for Protecting Your Passwords

If this deep dive into password manager vulnerabilities has left you feeling anxious, here's what actually matters for keeping your accounts safe:

Choose a reputable password manager with recent security audits. Whether that's Bitwarden, 1 Password, Dashlane, Last Pass, or another option, the important thing is that it's a recognized company with a security track record. Don't use random small tools or browser-based solutions.

Use a truly random master password of at least 20 characters. This is your most critical security decision. Use your password manager itself to generate it, then write it down and store it securely (physically, in a safe or vault). Your master password should be something you literally cannot remember.

Enable two-factor authentication on your password manager account. This is the single most effective protection against the class of vulnerabilities discovered in this research. An attacker needs both your master password derivation and your second factor.

Disable recovery and key escrow features unless you actively need them. These are the primary attack surfaces for these vulnerabilities. If you're confident you won't forget your master password, disable the recovery mechanisms.

Update your password manager regularly. Security issues get fixed. New versions address problems. Staying current isn't optional.

Use unique, strong passwords for every account. This is the entire point of password managers. If a site gets breached, attackers get one password that only works on that one account. They can't use it to compromise your email, your banking, or anything else.

Password managers remain your best practical defense against credential compromise. These vulnerabilities are real and worth understanding. But they're not a reason to stop using password managers. They're a reason to use them thoughtfully and carefully.

The Broader Cybersecurity Landscape: What Else Is Happening

While password manager vulnerabilities dominated security news in late 2024, they're just one piece of a much larger picture of evolving cyber threats.

The Epstein Files Revelations and Industry Trust

The release of previously sealed documents related to Jeffrey Epstein exposed uncomfortable truths about financial and political networks. But in the context of cybersecurity, these revelations had another impact: they revealed how deeply problematic actors had infiltrated trusted institutions, including prominent figures in the technology and cybersecurity communities.

When the Defcon hacker conference banned three individuals based on their documented associations with Epstein, it raised uncomfortable questions about vetting, about who we trust with security knowledge, and about the gap between an industry's public values and the networks that actually operate within it.

For cybersecurity specifically, the revelations underscored something security professionals already knew: insider threats are real, institutional corruption is possible, and the security community isn't immune to these problems.

Government Censorship Tools and Internet Freedom

The US State Department's registration of "freedom.gov" as an anti-censorship portal represents an interesting and potentially problematic shift in how the US approaches internet freedom globally.

Theoretically, the portal could help people in censored countries access information they're being blocked from. Practically, it opens questions about US government involvement in circumventing other governments' laws, about whether US-sanctioned information access platforms are truly different from the control mechanisms they're designed to circumvent, and about the complexity of internet governance in an increasingly fragmented digital world.

For password manager users specifically, it's worth noting that if you're in a country with significant internet censorship, a password manager that can be accessible through VPN or other circumvention tools might be more critical than in less restrictive countries.

AI and Synthetic Identity Threats

One aspect not covered in the password manager research but increasingly relevant: synthetic identity creation using AI.

As large language models become more sophisticated, creating convincing fraudulent accounts, phishing emails, and identity impersonations becomes easier. Password managers provide defense against some of these threats (strong, unique passwords prevent account takeovers). They don't defend against fraud that never involves guessing your password.

Supply Chain Vulnerabilities in Security Tools

The vulnerabilities discovered in password managers are part of a broader pattern: security tools themselves have become attractive targets for attackers.

If you compromise the password manager, you compromise every account the user has. If you compromise the VPN provider, you can see all the user's traffic. If you compromise the antivirus software, you have full system access.

This means security vendors are under greater attack pressure than general software companies. They need not just good security, but exceptional security. The ETH Zurich findings suggest that not all password managers are meeting this bar.

Looking Forward: The Future of Password Manager Security

The password manager industry will evolve in response to these findings, and understanding the direction of that evolution matters for your security decisions.

Hardware-Based Key Storage

One promising direction is moving encryption key material to hardware security modules (HSMs). If your encryption key never exists in software where attackers can copy it, the threat surface shrinks dramatically.

Some password managers are exploring this, but it requires significant infrastructure changes and additional hardware that increases costs. It's likely to remain an enterprise feature for the foreseeable future.

Distributed Encryption

Another approach: instead of storing all your encrypted credentials in one company's database, distribute them across multiple providers or across your own devices.

Imagine a system where your password manager keeps only a fraction of the encryption key, your email provider keeps another fraction, and your phone keeps the final piece. No single compromise exposes all your passwords.

This is technically possible but very hard to implement in a user-friendly way. It also requires trusting multiple parties rather than one, which might not actually improve security if you don't trust all the parties equally.

Post-Quantum Cryptography

Long-term, password managers will need to migrate to cryptography that's resistant to quantum computers. The current encryption algorithms work fine against classical computers but would be vulnerable to sufficiently powerful quantum computers.

Password manager companies are already planning this transition, but it takes time. The cryptographic standards need to be finalized, implementations need to be tested, and users need to be migrated to new systems without losing access to their existing credentials.

Stronger Key Derivation Standards

The most immediate fix: more aggressive key derivation functions that make brute-forcing master passwords harder.

But this creates a usability trade-off. Stronger key derivation means slower logins. Some users will resist this, particularly on mobile devices with limited processing power.

It's the classic security versus convenience tension that will keep recurring in password manager design.

Making Peace with Imperfect Security

If there's one big insight from these password manager vulnerabilities, it's this: perfect security doesn't exist. Security is always a compromise.

Password managers remain vastly superior to the alternatives for most users. The cryptographic vulnerabilities discovered don't change that basic fact. What they do is remind us to be thoughtful, to verify security claims independently, and to layer multiple security measures rather than relying on any single tool to be perfectly secure.

Your goal shouldn't be to find the perfectly secure password manager. Your goal should be to reduce your actual risk of account compromise relative to the effort you're willing to expend on security.

For most people, that means using a reputable password manager, protecting your master password carefully, enabling two-factor authentication on critical accounts, and maintaining good password practices.

The vulnerabilities are real. Your need for better security practices is real. The good news is that addressing one helps with the other.

FAQ

What exactly is a "zero knowledge" password manager?

A zero knowledge password manager is one where the company claims they cannot access your passwords because the encryption and decryption happen entirely on your device. Your encrypted passwords are stored on their servers, but only you have the decryption key. In theory, this means even the company employees cannot see your actual passwords. However, as the ETH Zurich research shows, this theoretical claim often doesn't match the practical implementation, particularly when recovery features are enabled.

Can I still trust password managers after these vulnerabilities were disclosed?

Yes, password managers remain significantly more secure than the alternatives, even with these vulnerabilities. The discovered flaws are real and concerning, but they typically require specific preconditions (like an infrastructure breach or insider threat) to exploit. Using a strong master password, enabling two-factor authentication, and keeping your password manager updated dramatically reduces your practical risk. The alternative to using a password manager—reusing passwords or writing them down—is far more dangerous for the vast majority of users.

Which password manager should I use if I'm worried about these vulnerabilities?

There's no single perfect answer, but consider these factors: Open-source password managers like Bitwarden allow public code review but rely on community security expertise. Enterprise solutions like Dashlane have larger security teams but were more compromised by the research findings. Historical players like Last Pass have had previous breaches but continue to improve security. The most important factor is enabling two-factor authentication on whichever service you choose.

How strong does my master password actually need to be?

Your master password should be at least 20 characters long, truly random (using a password generator, not something you create yourself), and include mixed case, numbers, and symbols. Because it's so critical, write it down in a secure location (physical safe or vault) rather than relying on memory. This seems counterintuitive—writing down a password—but a strong written master password is far better than a weak one you can remember. Your password manager handles the rest of your passwords, so your master password only needs to be strong enough to protect your vault.

Are these vulnerabilities being actively exploited in the wild?

The research doesn't definitively prove that these specific vulnerabilities have been exploited. However, given that they're practical to exploit and some date back years in certain implementations, it's reasonable to assume sophisticated attackers may have discovered and abused them before public disclosure. This is why timely updates and strong security practices matter: the vulnerabilities might have been exploited before you even knew they existed.

What does "key escrow" actually do, and should I use it?

Key escrow is a recovery feature that lets you reset your master password if you forget it. The company stores an encrypted copy of your decryption key, and if you prove your identity (through recovery codes or other methods), they can give you access to it. This is convenient but weakens security because the company now stores additional key material. Unless you actively need password recovery (and you might not if you store your master password securely), disabling this feature reduces your attack surface.

Do these vulnerabilities mean I should use a local password manager instead of a cloud-based one?

Local password managers like Kee Pass eliminate some risks (you're not trusting a cloud company's infrastructure) but create others (you're responsible for backing up your vault, synchronizing across devices, and protecting it from malware on your local devices). Cloud-based managers make recovery and synchronization easier but do create centralized targets. The choice depends on your comfort with technical management and your threat model. For most users, a cloud-based manager with strong master password and two-factor authentication remains the better option.

How often should I update my password manager?

You should update your password manager whenever security patches become available, ideally within days of release. Enable automatic updates if your password manager supports them. Security patches typically address vulnerabilities like those found in this research. Additionally, update all other software on your devices regularly—the password manager is only one part of your security system. A compromised browser, operating system, or other software could still expose your credentials even if your password manager is perfectly secure.

Where Password Managers Fit in Your Broader Security Strategy

Password managers aren't magic. They're one tool in a larger security ecosystem. To actually be secure, you need to think about the whole picture.

The Layers of Account Protection

Your account security should look like an onion: multiple layers protecting against different types of attacks.

Layer 1: Strong, Unique Passwords - This is what password managers enable. Every account gets a different, strong password.

Layer 2: Two-Factor Authentication - A second thing attackers need even if they have your password. For critical accounts (email, banking, social media), this is essential.

Layer 3: Recovery Options - Recovery codes, backup methods, and emergency contacts should be documented in case you lose access to your second factor.

Layer 4: Monitoring and Alerts - Set up notifications for login activity, password changes, and account access. This helps you catch compromises quickly.

Layer 5: Backup Plans - In the worst case where your password manager is compromised, what happens? This is where offline backups of critical information matter.

Password managers excel at Layer 1. They're helpful for Layers 2-4. They don't address Layer 5. You need to think about all five.

The Risk of Putting All Eggs in One Basket

One legitimate concern with password managers is concentration of risk. If your password manager is compromised, every account is potentially at risk. This is exactly what the cryptographic vulnerabilities researchers found could happen.

You can mitigate this by:

- Using two-factor authentication everywhere (so compromised passwords aren't enough)

- Not storing passwords for the most sensitive accounts in your password manager (keep your email and banking passwords elsewhere)

- Monitoring your most critical accounts closely for suspicious activity

- Having recovery codes and backup authentication methods for important accounts

These aren't perfect solutions, but they reduce the probability that a single compromise cascades into total account takeover.

The Alternative (And Why It's Worse)

The thing is, the alternative to using a password manager is worse.

If you don't use a password manager, you either:

- Reuse passwords (which means one breach compromises multiple accounts)

- Use weak passwords (which means individual accounts are easily hacked)

- Write passwords down (which means anyone with physical access to your notes can compromise you)

- Use predictable patterns (like My Account Name 123, which attackers crack automatically)

Any of these options puts you at higher risk than using a password manager, even one with the vulnerabilities discovered in this research. The attackers don't need subtle cryptographic attacks if your password is "password 123".

The Human Factor

Ultimately, the security of your password manager depends as much on your behavior as on the technology.

A perfectly secure password manager is useless if you:

- Write your master password down on a sticky note

- Share your master password with someone else

- Use the same master password for multiple services

- Fall for a phishing attempt and enter your master password on a fake website

- Store your master password in a note on your phone that isn't password-protected

Conversely, even a flawed password manager provides decent protection if you:

- Keep your master password confidential and complex

- Don't fall for phishing (verify URLs carefully)

- Enable two-factor authentication

- Update regularly

- Monitor your accounts for suspicious activity

The vulnerabilities are real, but they operate in a threat landscape that includes human factors, technical factors, and organizational factors. Your behavior is part of the equation.

Conclusion: Living with Imperfect Security

The discovery that major password managers contain cryptographic vulnerabilities is uncomfortable. It challenges the marketing narrative that these services are unhackable.

But it's important to keep perspective. Real-world security is always a compromise between protection and practicality. Perfect cryptography exists in textbooks. Real-world systems are implemented by humans, deployed in complex environments, and need to balance security with usability.

Password managers remain essential tools for anyone managing more than five or six online accounts. The vulnerabilities discovered don't change that. What they do is reinforce the importance of defense in depth: strong master passwords, two-factor authentication, regular updates, and thoughtful account security practices.

The security landscape in 2025 is more complex than it was a decade ago. Threats are more sophisticated. Attackers have more resources. Your password manager is one line of defense, not your only one. Use it as part of a broader security strategy, understand its limitations, and maintain the practices that actually keep you safe.

That's not perfect security. But it's the kind of security that actually works in the real world.

Related Articles

- Password Manager Vulnerabilities Explained [2025]

- Password Manager Zero Knowledge Claims Under Fire: What You Need to Know [2025]

- Online Privacy Questions People Are Asking AI in 2026 [Guide]

- 6.8 Billion Email Addresses Leaked: What You Need to Know [2025]

- Mac Security & Antivirus Protection Guide [2025]

- CX Platform Security Gaps: 6 AI Stack Blind Spots Attackers Exploit [2025]

![Password Manager Security Flaws Exposed: What You Need to Know [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/password-manager-security-flaws-exposed-what-you-need-to-kno/image-1-1771675599391.jpg)