Password Manager Vulnerabilities Explained [2025]

You trust your password manager with everything. Your bank login. Your email account. Your cryptocurrency exchange credentials. The whole digital foundation of your life, basically.

So when researchers at ETH Zurich and Università della Svizzera italiana (USI) published findings showing that 27 vulnerabilities existed across the four most popular password managers in the world, it sent shockwaves through the security community. Not because it was surprising that vulnerabilities existed, but because of where they found them and what attackers could do with them.

Here's the thing: these weren't theoretical bugs buried in obscure code paths. These were fundamental architectural flaws affecting the core mechanics of how password managers encrypt, store, and share your credentials. The research showed that attackers with access to a compromised server could potentially rewrite your passwords, steal your entire vault, or trick you into adding fake credentials that look legitimate.

The affected managers include Bitwarden, Last Pass, Dashlane, and 1 Password, collectively protecting over 60 million individual users and nearly 125,000 businesses worldwide. Each platform had different vulnerabilities across four major categories: key escrow flaws, vault encryption weaknesses, sharing mechanism gaps, and backwards compatibility issues.

Now, the good news: there's no evidence these vulnerabilities have been exploited in the wild. All affected vendors have begun remediation efforts, with several vulnerabilities already patched. But what matters right now is understanding what went wrong, why it matters, and what you should do to protect your accounts.

Let's break this down.

TL; DR

- 27 vulnerabilities discovered across Bitwarden (12), Last Pass (7), Dashlane (6), and 1 Password (2) affecting 60+ million users

- Key escrow flaws allow attackers to intercept encryption keys during account recovery processes without proper authentication

- Vault encryption gaps leave credential metadata unencrypted, allowing attackers to identify and manipulate stored passwords

- Weak sharing mechanisms enable attackers to gain unauthorized access to shared credentials and folders

- Backwards compatibility exploits let attackers downgrade encryption to older, weaker algorithms

- No active exploits confirmed, but all vendors have released or are releasing patches

- Best practice: enable additional authentication, use unique master passwords, and keep your client software updated

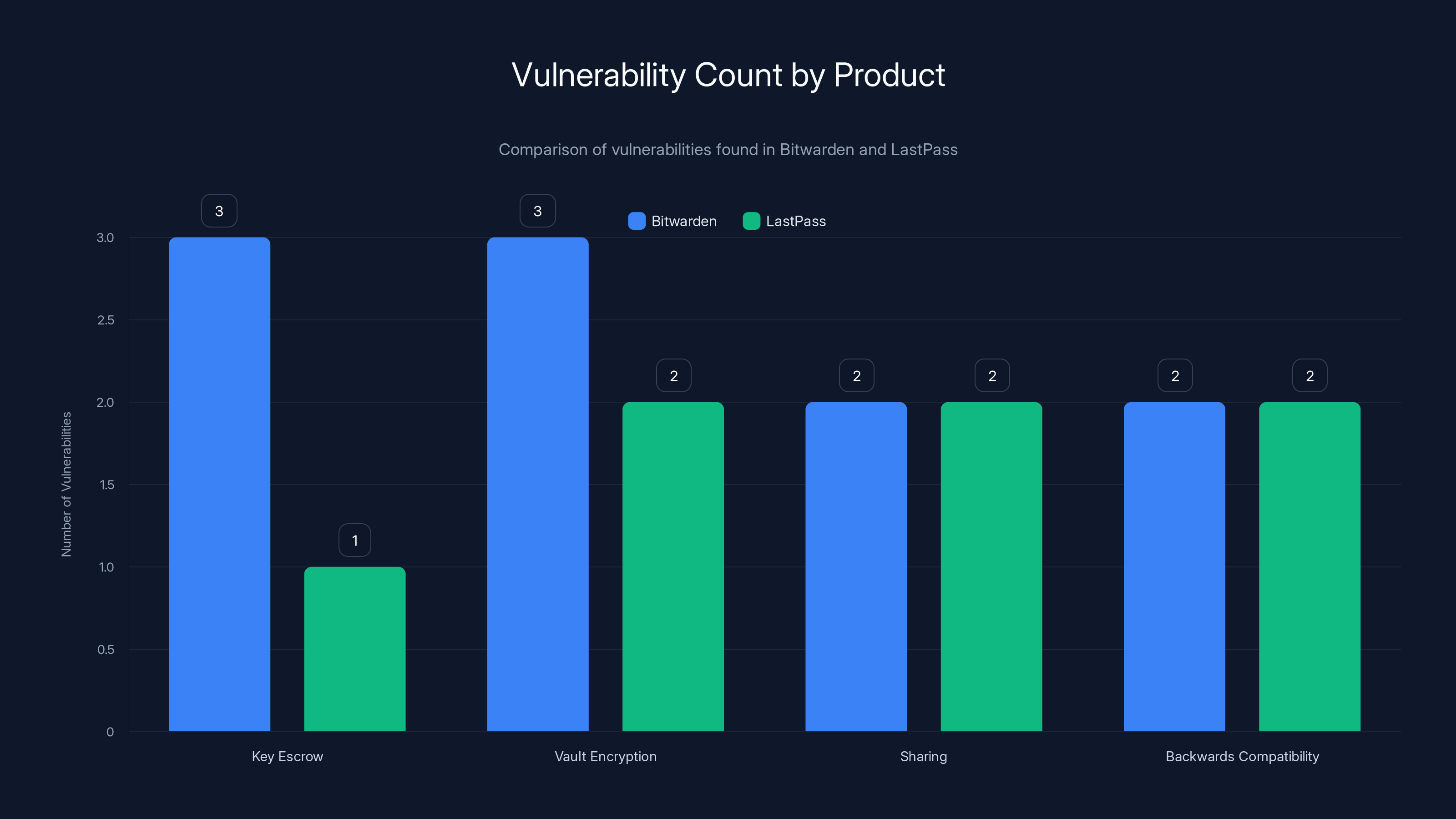

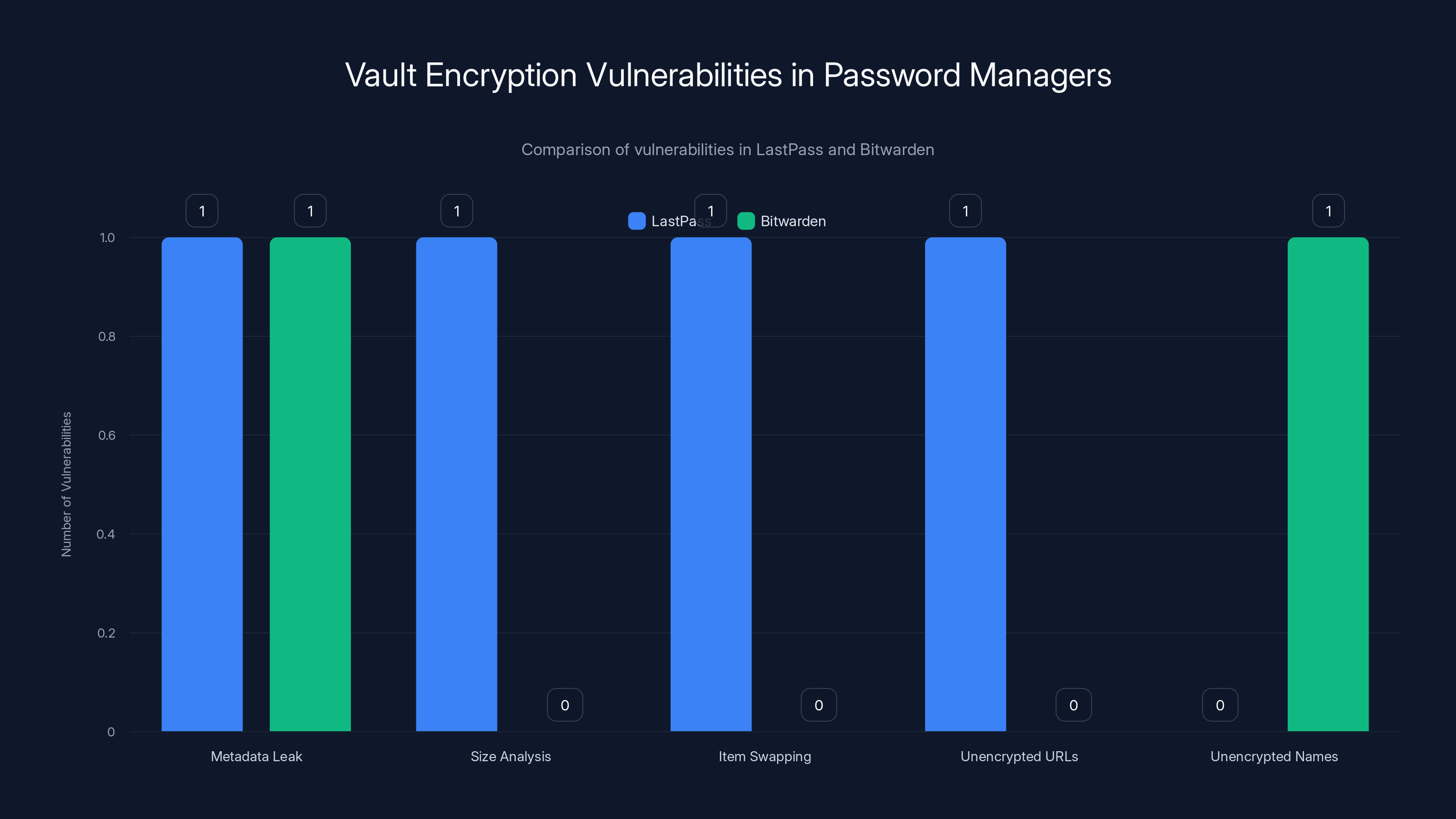

Bitwarden had a total of 12 vulnerabilities, with key escrow and vault encryption being significant areas of concern. LastPass had 7 vulnerabilities, distributed more evenly across categories. Estimated data based on narrative.

Understanding Password Manager Architecture

Before diving into the vulnerabilities, you need to understand how password managers actually work at a fundamental level. Most people think of them as simple encrypted databases. Close, but not quite.

Here's the real architecture: when you create an account with a password manager, your master password never leaves your device. Instead, it's used to derive an encryption key through a process called key derivation. This derived key encrypts everything in your vault locally, on your computer or phone. Then, the encrypted vault gets synchronized to the cloud so you can access it from other devices.

The critical part: only your device knows the encryption key. The password manager's servers only store the encrypted blob. They can't decrypt it. They shouldn't even be able to decrypt it.

That's the theory. In practice, password managers have added convenience features over the years that complicate this model. Account recovery is the big one. If you forget your master password, how do you get back into your account? The password manager needs some way to help you recover access without requiring the master password itself. This creates a fundamental tension between convenience and security.

Other features that complicate the model: shared credentials (so your team can access a Wi-Fi password), backwards compatibility with older encryption standards, and account synchronization across multiple devices.

Each of these features introduces potential attack vectors. The research examined all of them.

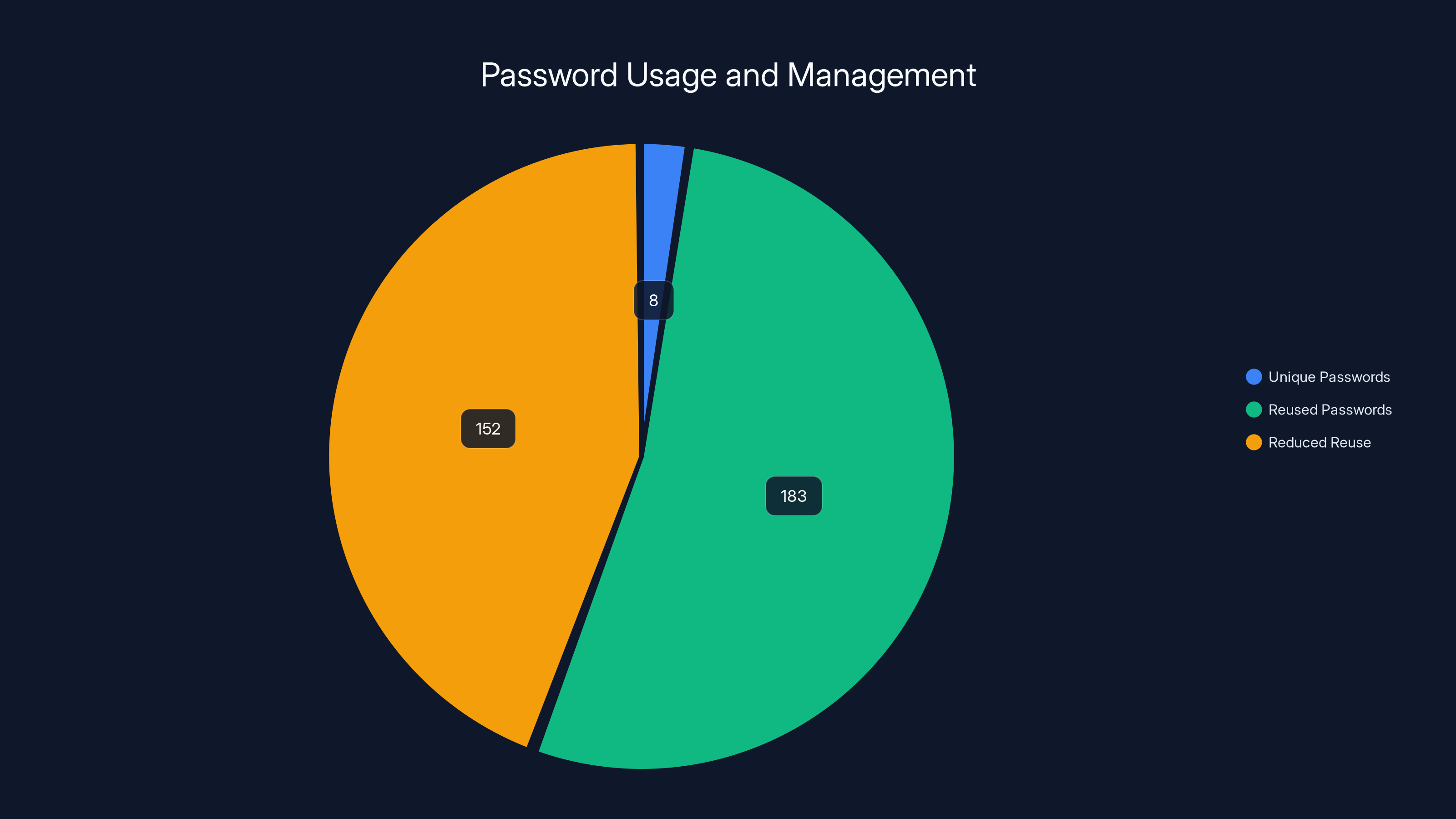

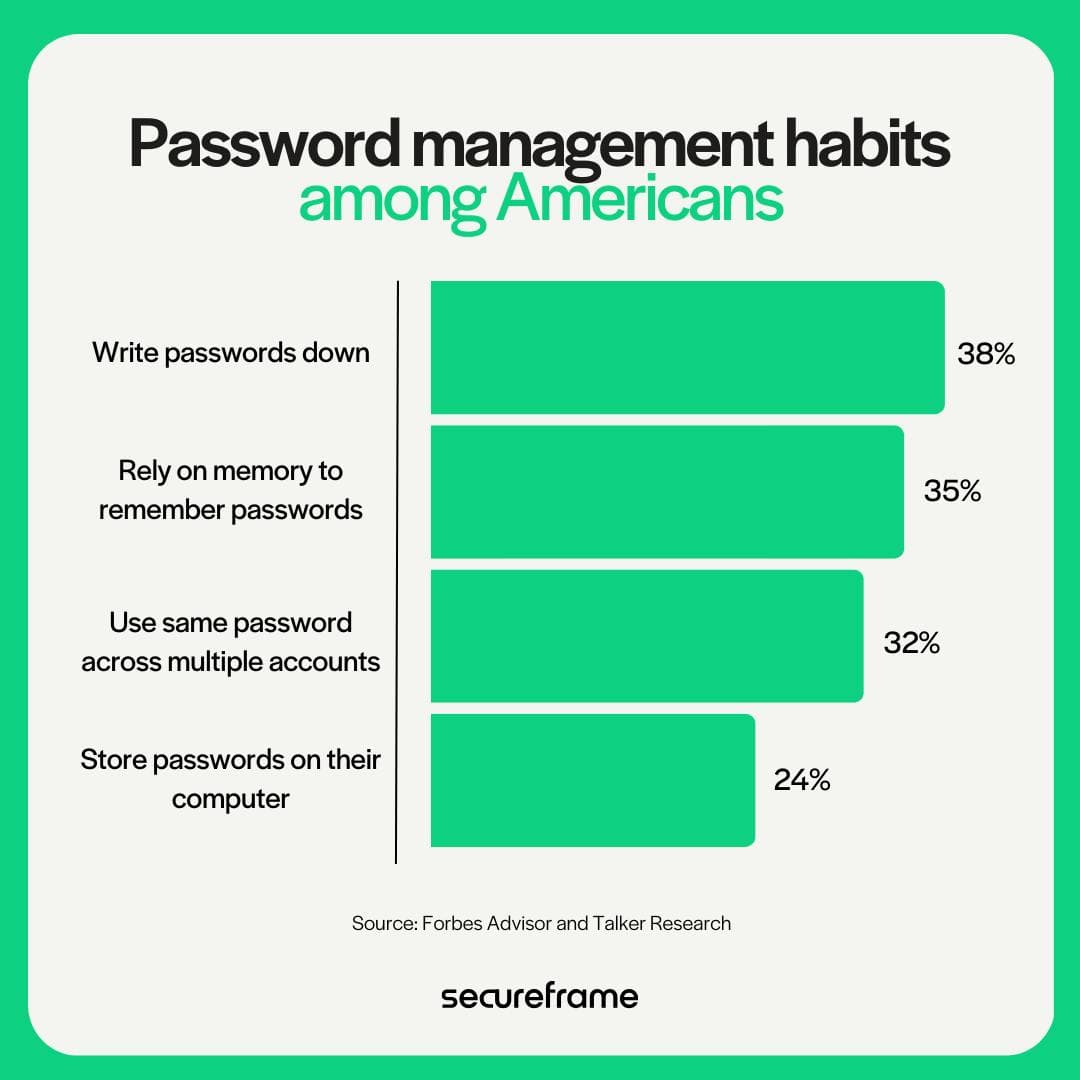

The average person manages 191 passwords but only uses 5-8 unique ones. Password managers can reduce password reuse by an estimated 80%, highlighting their effectiveness in enhancing security.

Key Escrow Vulnerabilities: The Account Recovery Problem

Key escrow is a fancy term for a simple concept: storing a copy of your encryption key somewhere safe so you can recover your account if something goes wrong.

Most password managers implement this using a wrapped key system. Here's how it works: your actual encryption key is wrapped (encrypted) using a different key derived from your master password. Then, a recovery key is generated and presented to you during setup. You're supposed to save this recovery key somewhere safe like your password manager (ironic, I know), a physical notebook, or your email.

If you forget your master password, you can use the recovery key to regenerate access to your account. It's a sensible design on paper.

The vulnerability researchers found: in some implementations, the key escrow mechanism didn't require proper authentication. An attacker who gained access to the server could request a key recovery without needing to know the master password. In other cases, the recovery process accepted requests from any IP address without rate limiting or alerting the user.

Bitwarden was vulnerable to three key escrow attacks. One attack path involved intercepting the account recovery endpoint and requesting decryption keys without proper verification. Another involved exploiting a missing authentication check that allowed direct key access. A third involved a race condition where an attacker could trigger recovery before the user's legitimate request completed.

Last Pass had one key escrow vulnerability related to how recovery tokens were validated. The token validation logic didn't properly check the timestamp or origin of the request, theoretically allowing an attacker to reuse old tokens or forge new ones.

The attack flow was straightforward: an attacker gains server access (through a breach, insider threat, or man-in-the-middle positioning), then exploits the weak recovery authentication to grab the wrapped encryption keys. With those keys and the ability to trigger a password reset on the victim's email account, the attacker could change the master password and take over the entire vault.

The remediation here is straightforward but important: authentication checks need to be reinforced on all recovery endpoints. The validators need to confirm the request comes from an authenticated session, rate-limit recovery attempts, and alert the user whenever a recovery is initiated. Some vendors were already doing this; others weren't.

Vault Encryption Flaws: When Metadata Leaks

This is where things get more subtle and potentially more dangerous.

Ideal vault encryption works like this: everything in your vault—every password, every URL, every note, every metadata field—gets encrypted together as a single block. If an attacker gets access to the encrypted blob, it's completely opaque. They can't tell if it contains 5 passwords or 500. They can't tell if you're storing cryptocurrency keys or just your Netflix password. It's all encrypted noise.

Several password managers don't do this. Instead, they encrypt each credential individually. Your Gmail password gets encrypted separately from your Amazon password, which gets encrypted separately from your banking password. And then, metadata about the vault—like how many items you have, what categories you use, sometimes even the URLs associated with credentials—gets stored unencrypted.

Why? Performance. Encrypting everything as a single block means decrypting the entire vault every time you look at a single password. Encrypting items individually allows the client to decrypt only what you need.

Last Pass was vulnerable to five vault encryption attacks. One attack involved analyzing the sizes of individual encrypted password items to determine how many passwords were in the vault and make educated guesses about their contents. (A 50-byte encrypted item is probably just a password; a 500-byte item might be a SSH key or secured note.) Another attack involved swapping items within fields to leak information. A third attack exploited unencrypted URLs that were stored alongside encrypted credentials, allowing the attacker to correlate URLs with password patterns.

Bitwarden had four similar vulnerabilities. One involved unencrypted names of credential items, allowing an attacker to identify what each password was for. Another involved the organization structure being partially unencrypted, revealing which credentials were shared and who they were shared with.

Dashlane was vulnerable to one vault encryption attack involving unencrypted metadata about secure notes, allowing an attacker to determine which accounts had associated notes and what categories of information was being stored.

The attack methodology was clever: an attacker doesn't need to decrypt anything. They just analyze the patterns, sizes, and metadata of encrypted items to make inferences about the contents. A 256-byte field is probably a password plus username. A 2MB field is probably a file attachment. An attacker could systematically map out your entire vault structure without ever decrypting a single item.

Worse, if the attacker has a dictionary of common passwords and can see which items are swapped or modified, they can narrow down possibilities. If they know you use Gmail, they can search for items likely associated with Gmail and make educated guesses about which encrypted blob contains that specific credential.

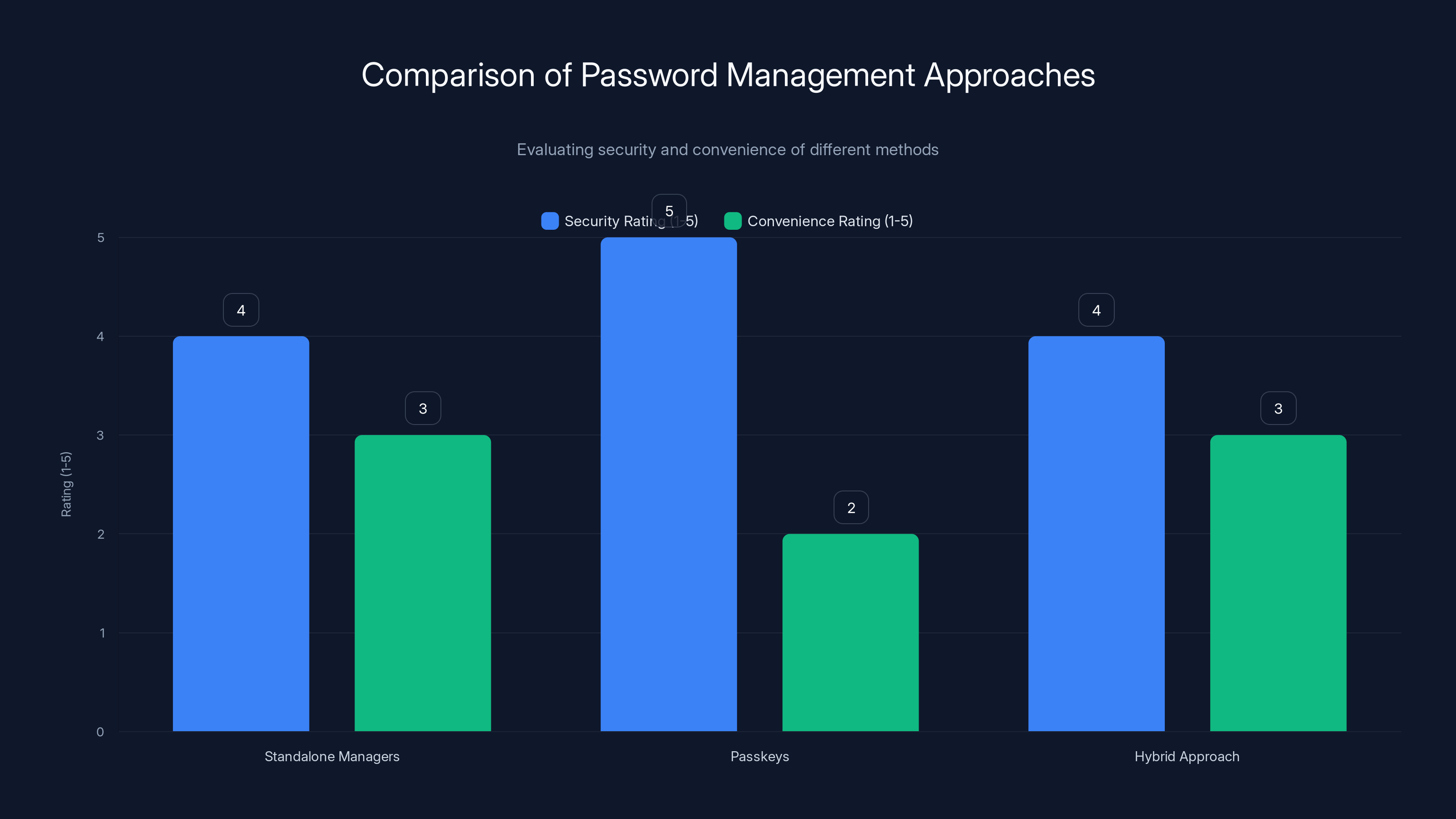

Standalone managers and hybrid approaches offer high security but vary in convenience. Passkeys provide the highest security but are less convenient due to limited adoption. Estimated data based on typical user experience.

Sharing Mechanism Vulnerabilities

Most password managers include sharing functionality. You want to share your Wi-Fi password with a houseguest. Your team needs access to the AWS account credentials. Your family should know your emergency contact information.

Sharing is convenient. But convenience and security are frequently at odds.

The researchers found that in several password managers, the sharing mechanism included very minimal authentication checks. Here's a specific example of an attack:

An attacker creates an "organization" within the password manager system. Organizations are typically used for team collaboration. Then, the attacker adds victim users to this fake organization using only the victims' public usernames (no email verification, no explicit acceptance required). The password manager then automatically synchronizes these users with the fake organization.

Now the victims appear to belong to an organization they never joined. If the password manager's sharing logic automatically grants organization members access to shared items, the attacker has access to everything shared within the organization. Better yet, the attacker can now add malicious items to the shared folders.

Bitwarden was vulnerable to two sharing attacks. One involved the organization creation process not validating that the creator actually owned an email domain before granting organization creation privileges. Another involved shared folder permissions being applied retroactively to items added after the sharing was set up.

Last Pass had one sharing vulnerability related to how shared items were synchronized to new members. When a user was added to a shared group, the password manager would push all previously shared items to them, but the permission validation happened asynchronously. An attacker could theoretically view items before permission checks completed.

Dashlane also had one sharing vulnerability involving the sharing invitation process not properly validating the identity of the person receiving the shared credentials.

The implications were serious: an attacker could gain access to shared credentials without authorization, or even more troubling, add backdoor credentials to the vault that look legitimate but were actually controlled by the attacker.

Think about the corporate scenario: a company uses a password manager to share database credentials across a team. An attacker compromises the server, creates a fake organization, and adds themselves to the real team. Now they have database access. They could even add a second database credential that looks identical to the real one but points to their own honeypot, capturing everything the legitimate users do.

Backwards Compatibility Exploits

This category is sneaky because it exists for a legitimate reason: helping users transition smoothly between old and new encryption standards.

Password managers need to maintain backwards compatibility because users don't all update at the same time. A company might have legacy systems running old password manager versions. A user might have credentials encrypted with an old algorithm that they want to keep using. To avoid forcing everyone to re-encrypt everything at once, password managers support multiple encryption standards.

But here's the problem: if an attacker can downgrade the encryption, they can force the client to use a weaker algorithm.

Let's say the password manager originally used DES (Data Encryption Standard), which was standard in the 1970s and is now trivially broken. Then they upgraded to AES-256, which is currently unbreakable. The password manager code still contains the DES decryption logic for backwards compatibility.

An attacker who compromises the server could modify the client's requests or responses to force the use of DES. Now, instead of the user's vault being encrypted with unbreakable AES-256, it's encrypted with DES, which can be broken in seconds with modern computers.

Dashlane was vulnerable to four backwards compatibility attacks. One involved the encryption algorithm negotiation happening in plaintext without authentication, allowing an attacker to modify the algorithm selection. Another involved the client not validating that the key derivation parameters matched the user's configured settings.

Bitwarden had three backwards compatibility vulnerabilities. One involved supporting legacy encryption modes that were weaker than the current standard. Another involved the client not properly validating the encryption version in stored credentials.

The attack wouldn't necessarily be obvious to the user. They'd unlock their vault, and it would work fine. They wouldn't realize that their credentials had been downgraded to weak encryption and were now vulnerable.

LastPass and Bitwarden both have vulnerabilities related to metadata leaks, but differ in other areas. LastPass has more vulnerabilities related to size analysis and item swapping, while Bitwarden has issues with unencrypted names.

How Attacks Actually Work in Practice

Understanding the categories is one thing. Understanding how they'd actually be exploited is another.

Let's walk through a realistic attack scenario that combines multiple vulnerabilities:

Step 1: Server Compromise

The attacker gains access to the password manager's cloud servers. This could happen through a zero-day vulnerability, a supply chain compromise, a malicious insider, or an advanced persistent threat. The details don't matter—assume the attacker has read-write access to the database and the ability to modify the API responses.

Step 2: Target Identification

The attacker identifies a high-value target. Maybe it's an executive at a target company, a cryptocurrency trader with valuable keys stored, or just a random business owner. They look at the unencrypted metadata (key escrow vulnerabilities) to understand what's in the vault without decrypting anything. URLs, folder names, and item counts give the attacker valuable information about what's worth targeting.

Step 3: Attack Initiation

The attacker modifies the API response for the target user to inject a downgraded encryption parameter (backwards compatibility vulnerability). When the user next syncs their vault, the client version negotiation gets confused and starts using weak encryption for new items added to the vault.

Simultaneously, the attacker exploits the key escrow vulnerability. They trigger an account recovery request for the target user, which is processed without proper authentication because of the flaw in the recovery mechanism. The attacker now has access to the wrapped encryption key.

Step 4: Credential Theft and Modification

With the wrapped key and the knowledge of the weak encryption parameters, the attacker can decrypt the vault. They extract all credentials. But they don't delete the vault or do anything suspicious. Instead, they modify specific credentials.

Let's say the target's AWS credentials are stored in the vault. The attacker changes the AWS secret key to one they control, while keeping everything else identical. The user wouldn't notice because they'd still authenticate successfully (both the old and new keys would work for a period of time, thanks to AWS key rotation windows).

Step 5: Persistence

Now the attacker has access to the target's AWS account. They can read everything, modify everything, extract sensitive data. And the original password manager vault isn't flagged as compromised.

Worse, if the target's password manager vault is used for team sharing (sharing mechanism vulnerability), the attacker can add themselves to shared groups and access everyone else's credentials too.

This scenario isn't theoretical. It combines vulnerabilities that the researchers found in real password managers. The researchers didn't publish exploitation code, but the attack methodology is straightforward for anyone with the technical capability to compromise a server.

Specific Vulnerability Breakdown by Product

Bitwarden's 12 Vulnerabilities

Bitwarden, the open-source password manager, was hit hardest with 12 vulnerabilities across all four categories.

In key escrow, Bitwarden's recovery mechanism had three distinct vulnerabilities: missing authentication checks on recovery requests, unvalidated recovery tokens, and a race condition in the recovery process. The researchers found that an attacker could request key recovery without proving they owned the account.

Vault encryption flaws included unencrypted item names (revealing what each credential was for), unencrypted folder structure (revealing how credentials were organized), and metadata leakage about secure notes and attachments. The researchers could determine the vault's contents without decrypting anything by analyzing encrypted item sizes and metadata patterns.

Sharing vulnerabilities included the fake organization attack (creating an organization and adding victims without their consent) and retroactive permission application (shared items not properly restricting access during the first sync). An attacker could add themselves to any team and gain access to shared credentials.

Backwards compatibility issues included support for legacy encryption modes and insufficient validation of key derivation parameters. An attacker could modify API responses to force the use of weaker encryption.

Bitwarden responded to the research by acknowledging the findings and beginning remediation. Several patches have already been released. The open-source nature of Bitwarden actually helps here—security researchers can review the patches before they're deployed.

Last Pass's 7 Vulnerabilities

Last Pass, which has had multiple major security incidents already, was found vulnerable to 7 attacks.

One key escrow vulnerability involved recovery token validation not checking timestamps or request origins, allowing reuse or forgery of old tokens. Someone with access to an old recovery token could use it to regain access to a vault years later.

Five vault encryption flaws included analyzing encrypted item sizes to guess contents, swapping items to leak information, and exploiting unencrypted URLs stored alongside encrypted passwords. The researchers could determine approximately what passwords were in a vault by analyzing the sizes and patterns of encrypted fields.

One sharing vulnerability involved asynchronous permission validation, where shared items were pushed to new organization members before permission checks completed. An attacker could potentially see items before access was properly validated.

Interestingly, Last Pass wasn't found to have significant backwards compatibility vulnerabilities. Last Pass had already deprecated older encryption standards, which actually prevented that class of attack.

Last Pass committed to addressing the vulnerabilities within their disclosed timeline. Given the company's security history, they probably faced additional scrutiny from users and regulators.

Dashlane's 6 Vulnerabilities

Dashlane was vulnerable to 6 attacks spread across the different categories.

One vault encryption flaw involved unencrypted metadata about secure notes, allowing attackers to infer what types of information were being stored. One sharing vulnerability involved invitation validation not properly checking the identity of invitation recipients. And four backwards compatibility exploits involved encryption algorithm negotiation happening in cleartext and the client not validating stored encryption versions.

Dashlane's vulnerabilities were more concentrated in the backwards compatibility category than the other managers, suggesting their encryption and sharing mechanisms were somewhat more robust, but their version negotiation had weaknesses.

1 Password's 2 Vulnerabilities

1 Password was found vulnerable to only 2 attacks, both in the backwards compatibility category. This actually suggests a more secure architecture overall, though backwards compatibility is still a gap.

1 Password's leadership acknowledged the vulnerabilities and stated that they're related to documented architectural choices. 1 Password uses Secure Remote Password (SRP) for authentication, which prevents transmitting encryption keys to servers. This architectural decision helped prevent the more severe classes of attacks that affected other managers.

The company publicly stated their commitment to continually strengthening security and evaluating it against advanced threat models. Their lower vulnerability count suggests they're either doing something right architecturally or the researchers found it harder to identify their weaknesses. Probably both.

Keeping your password manager updated is the most crucial practice, followed by using a strong master password and enabling two-factor authentication. Estimated data.

The Patch Timeline and Remediation Efforts

Ahead of the research being publicly released, the researchers followed responsible disclosure practices. They contacted all affected vendors with a 90-day disclosure window. This is standard in security research: give vendors time to patch before publishing details that could be exploited.

All affected password managers took the disclosure seriously and began remediation efforts. Some vendors patched more quickly than others.

Bitwarden, being open-source, had patches available in their GitHub repository within weeks. The open-source model actually accelerates patching because the security fixes are visible and can be independently verified. Community security researchers can audit the code and confirm the fixes actually work.

1 Password was quick to respond, releasing a statement acknowledging the findings and their architectural approach to mitigating similar attacks in the future. They've already implemented mitigations for new credential creation in their enterprise product.

Last Pass and Dashlane committed to patching but were slower in the initial responses, likely because they needed to coordinate with their larger organizational structures and testing processes.

By the time this research was published, several vulnerabilities were already patched. Others were in the development pipeline. The key point: there's no evidence any of these vulnerabilities were exploited in production before being patched. This isn't like the Last Pass breach where stolen vaults could be attacked offline. These vulnerabilities required active server compromise to exploit.

What This Means for Users: Risk Assessment

Okay, let's talk about what you should actually worry about.

First, the good news: there's no evidence these vulnerabilities have been exploited in the wild. The researchers disclosed them through proper channels. The vendors are patching them. Your password manager being vulnerable doesn't mean your passwords have been stolen.

Second: most of these attacks require the attacker to have compromised the password manager's servers first. Yes, that's a scary scenario, but it's not the most likely attack vector. If someone can compromise Last Pass or Bitwarden's servers, they probably have other, easier ways to get what they want.

Third: not all vulnerabilities are equally exploitable. Key escrow vulnerabilities that require specific conditions are harder to exploit than vault encryption flaws that allow passive analysis. A backwards compatibility attack requires the attacker to control the user's network or the server's responses, which adds complexity.

But here's what you should actually be concerned about: the vulnerabilities highlight architectural weaknesses in how these services balance security and convenience.

Password managers need to support account recovery because people forget passwords. But account recovery is inherently a security challenge. The vulnerability research shows that several vendors haven't solved this problem as robustly as they should.

Password managers need to support sharing because teams genuinely need to collaborate on credentials. But sharing is complex. The vulnerabilities show that several vendors haven't secured sharing mechanisms as well as they should.

Password managers need to maintain backwards compatibility so older systems don't break. But backwards compatibility creates downgrade attack opportunities. The research shows that several vendors haven't properly restricted encryption algorithm selection.

These aren't zero-day exploits in the traditional sense. They're architectural gaps that only matter if someone with server access exploits them. But they're real, they affect major products, and they're being fixed.

Your risk depends on several factors:

Which password manager you use: Bitwarden users had more vulnerabilities affecting them, but Bitwarden is also open-source, so patches are more transparent. 1 Password users were least affected by the research. But vulnerability count isn't the only factor—vulnerability severity and ease of exploitation matter too.

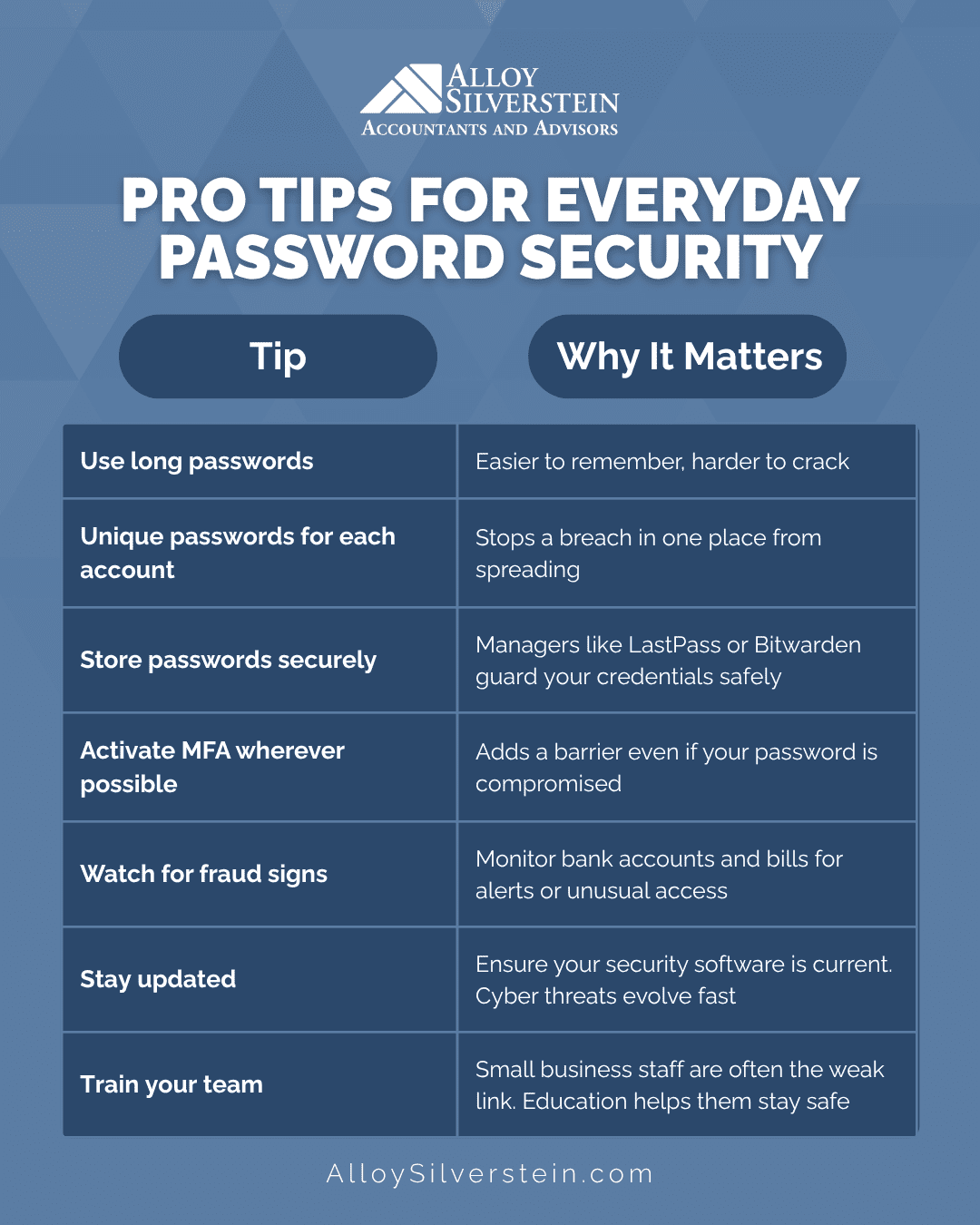

Whether you keep your software updated: This is the biggest single factor. If you update your password manager as soon as new versions are released, you'll get the patches that fix these vulnerabilities. If you ignore updates, you stay vulnerable.

What credentials you store: If you're storing banking passwords, cryptocurrency keys, and corporate credentials, the stakes are higher than if you're storing Netflix passwords. Attackers prioritize high-value targets.

Whether you use organizational sharing: If your password manager is used to share team credentials and you don't restrict who can view the shared items, the sharing vulnerabilities matter more.

Your threat model: If you're a regular person who's concerned about common threats (credential stuffing attacks, phishing), this research is interesting but shouldn't significantly change your behavior. If you're a high-value target of sophisticated attackers (CEO, security researcher, cryptocurrency trader), this research should make you reconsider your password management strategy.

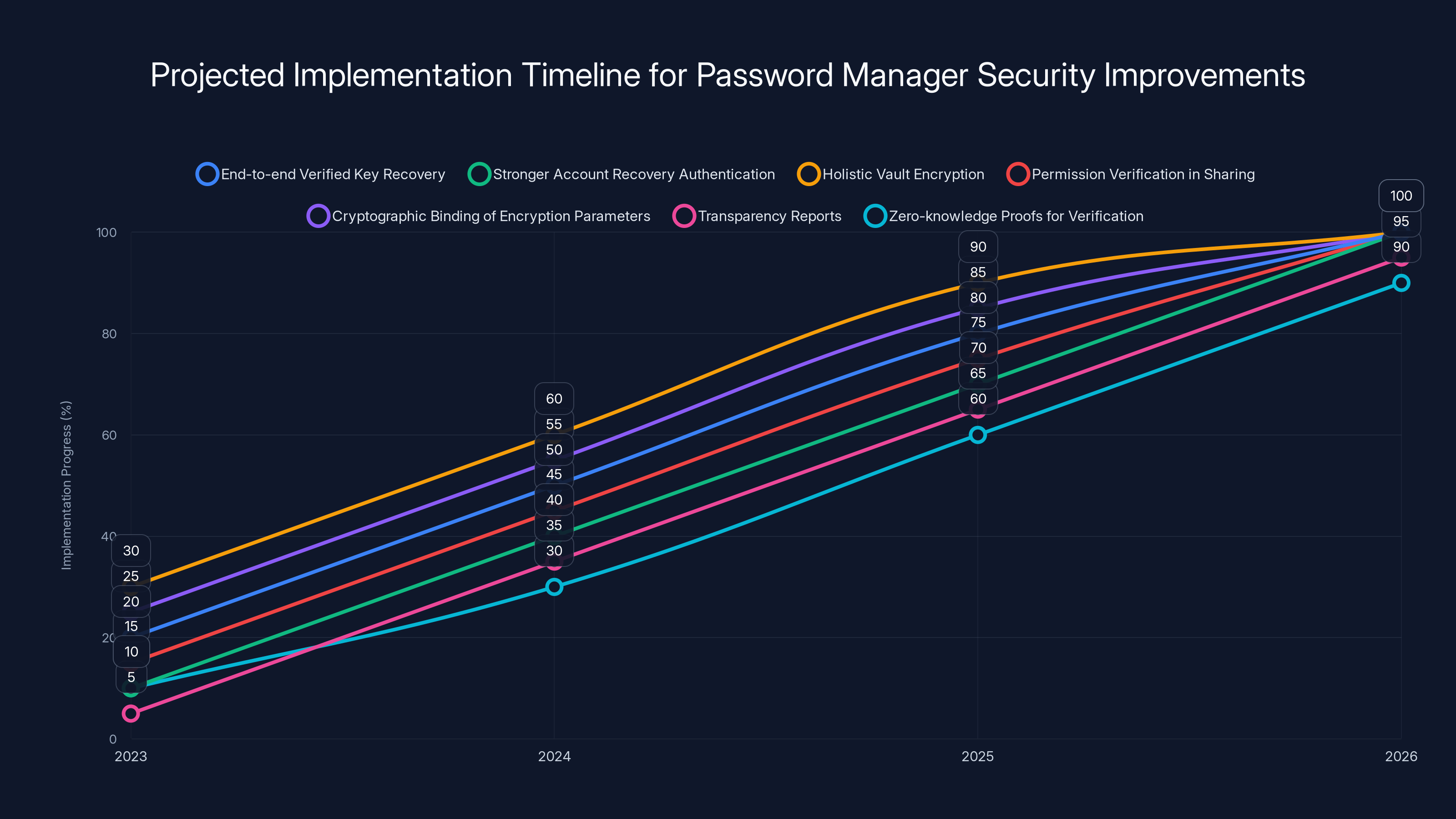

This timeline projects the adoption of various security improvements in password managers, with full implementation expected by 2026. Estimated data based on industry trends.

Best Practices to Protect Your Password Manager

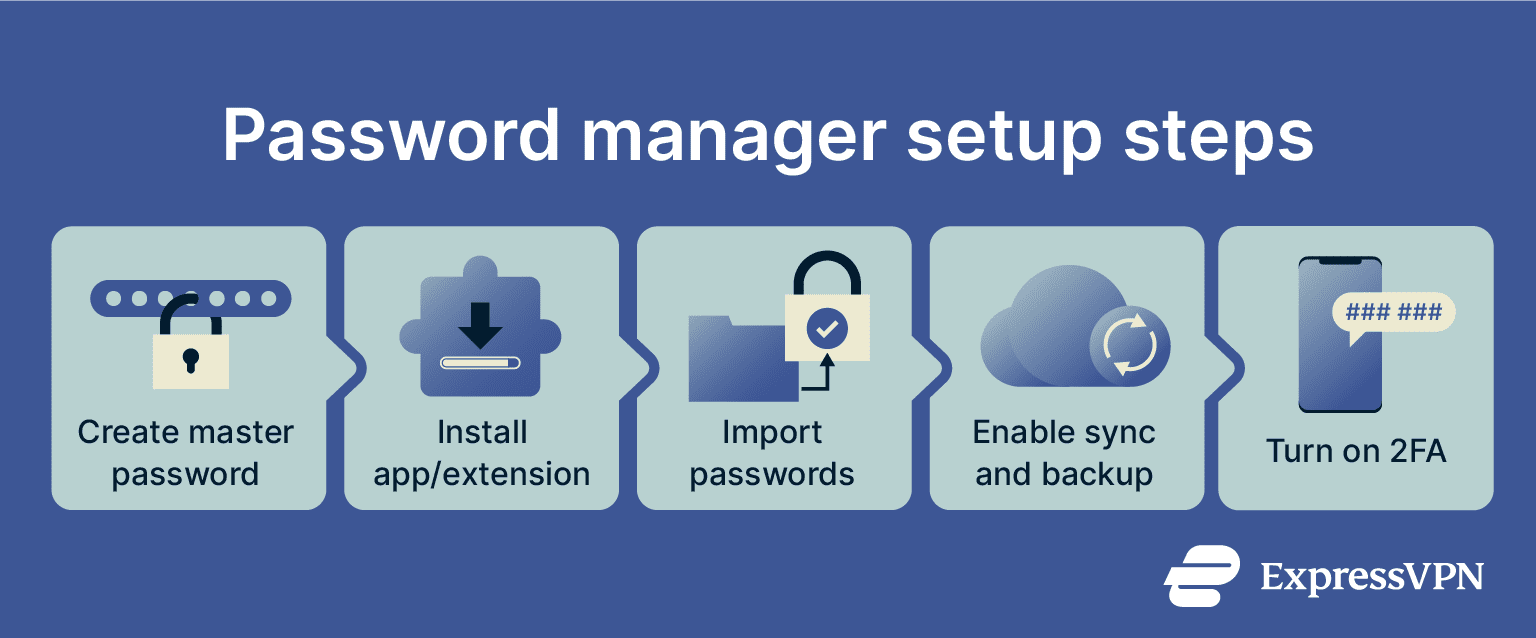

Given these vulnerabilities, what should you actually do?

First and most important: keep your password manager updated. Seriously, this isn't optional. Enable automatic updates if your password manager offers them. Check manually every week if it doesn't. The patches addressing these vulnerabilities are being deployed, and you need to be running the patched versions.

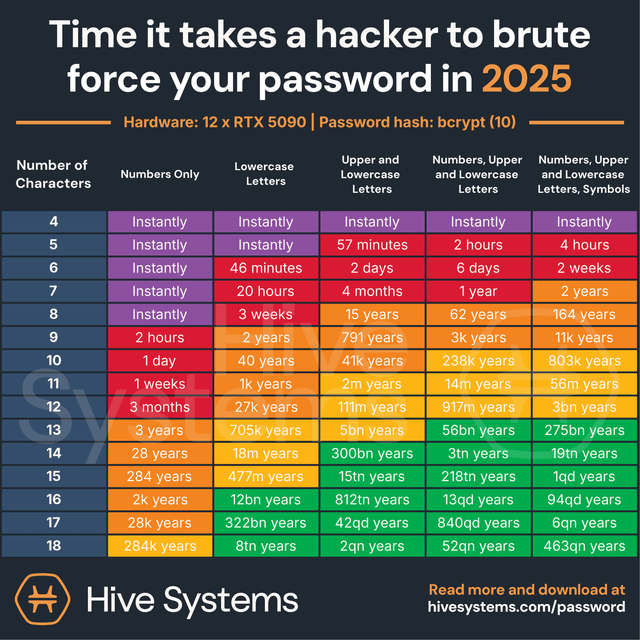

Second: use a strong, unique master password. This might sound obvious, but it's the foundation of everything. Your master password is the key to everything. If an attacker steals your encrypted vault and your master password is weak, they can break it offline. Make it at least 16 characters, include uppercase, lowercase, numbers, and special characters, and don't reuse it anywhere.

Third: enable two-factor authentication on your password manager account. Most password managers support 2FA (typically through authenticator apps like Google Authenticator or Authy). Yes, this adds an extra step to logging in. It's worth it. 2FA prevents account takeover even if someone has your master password.

Fourth: store your account recovery key in a separate, secure location. Don't store it in your password manager (ironic, but true). Don't store it in a cloud service that uses the same password as your password manager. Print it out, seal it in an envelope, and put it in a safe deposit box. You'll probably never need it, but if you do, you'll really need it.

Fifth: be careful with credential sharing. Only share credentials with people who actually need them. Use organizational or group sharing features if your password manager supports them, because they typically have better access controls than individual sharing. Always verify the identity of the person you're sharing with through a secondary channel (phone call, in-person conversation, corporate directory).

Sixth: consider your threat model and whether your current password manager is adequate. If you're storing cryptocurrency keys or accessing critical corporate systems, consider whether the password manager you're using has the security posture you need. 1 Password's response to these vulnerabilities was more reassuring than some others. Bitwarden's open-source nature means patches are transparent. Last Pass's history of breaches suggests reconsidering their platform entirely.

Seventh: don't share your master password with anyone, ever. Not with your spouse, not with your business partner, not with your IT department. If someone legitimately needs access to credentials, they should have their own password manager account and you should share the specific credential with them through your password manager's sharing feature.

Eighth: regularly review what's in your vault. Know what passwords you're actually storing. Are there old accounts you forgot about? Are there credentials that have been moved to other systems and don't need to be in the password manager anymore? Periodically audit your vault and clean up old, unnecessary credentials.

Alternative Approaches to Password Management

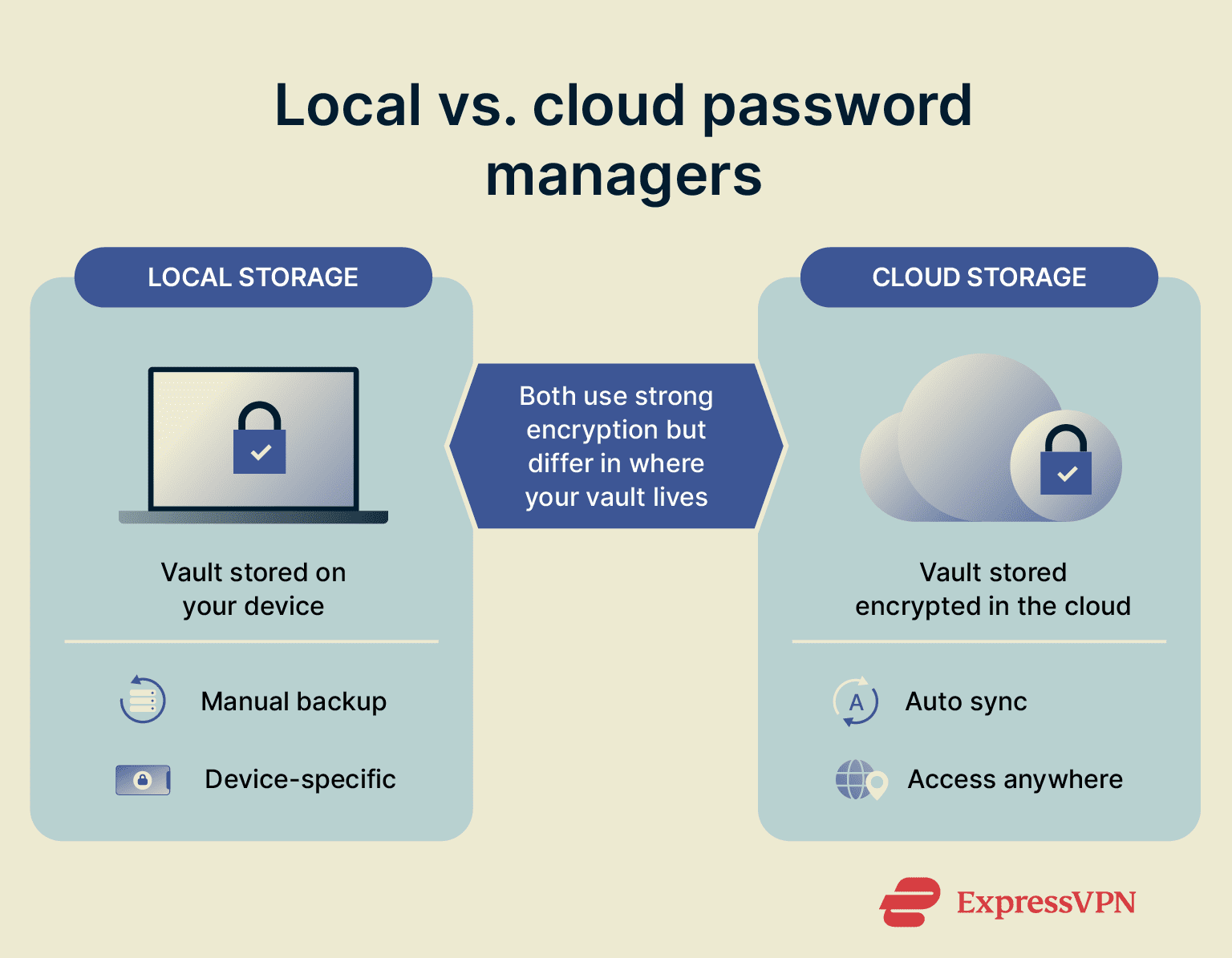

If these vulnerabilities shake your confidence in cloud-based password managers entirely, there are alternatives.

Standalone password managers like Kee Pass or Bitwarden Desktop (running locally) store your encrypted vault on your computer instead of the cloud. You lose the convenience of synchronization across devices, but you eliminate the risk of server compromise. Everything lives on your machine, encrypted with your master password, with no network component.

The tradeoff: you need to manage backups yourself. If your computer's drive fails, your vault is gone unless you've backed it up. You don't have access to your passwords on other devices unless you manually sync the file.

Passkeys (also called passwordless authentication) are a newer approach. Instead of storing passwords, you use your device's biometric authentication (fingerprint, face recognition) to prove your identity directly to websites. Websites that support passkeys don't store passwords at all—they verify your biometric locally on your device.

The advantage: no password manager needed. You can't have a password compromised if you don't have passwords. The disadvantage: websites still need to support passkeys, and adoption is slow. Currently only about 25% of major websites support them.

Hybrid approach: Use a password manager for most of your accounts, but keep critical accounts (email, banking, cryptocurrency) using a different system. Maybe you use a password manager for convenience on lower-security accounts, but you memorize your most important passwords or store them in physical form.

The tradeoff: more inconvenient but potentially more secure for high-value accounts.

None of these alternatives is clearly superior for everyone. It depends on your threat model, your technical comfort level, and what balance you want between security and convenience.

For most people, a reputable cloud-based password manager with 2FA and regular software updates is still the best option. The vulnerabilities in this research are serious but not unsolvable. They're being patched.

What the Industry Has Learned

This vulnerability research contributes to a broader understanding of password manager security. Here's what the industry is taking away:

Key escrow is hard to get right. Account recovery features are useful, but they create security challenges that many vendors haven't adequately addressed. Future password managers will likely implement stronger authentication checks, rate limiting, and user notifications for all recovery attempts.

Vault encryption needs to be holistic. Encrypting individual items separately creates information leakage opportunities. Future designs will likely encrypt entire vaults as atomic units, with metadata also encrypted. This trades some performance for better security.

Sharing mechanisms need better access controls. Allowing users to add others to organizations without verification was a mistake. Future implementations will require explicit acceptance of organization invitations and verify ownership of email addresses before granting administrative privileges.

Backwards compatibility requires careful management. Supporting old encryption standards creates downgrade attack opportunities. Future managers will either eliminate legacy support or implement cryptographic binding that makes downgrades impossible without breaking the entire system.

Server-side compromise must be assumed. Password managers are increasingly treating server compromise as a threat model they need to defend against, not just treat as catastrophic. This means moving more validation and cryptographic operations to the client side.

The good news: these are all solvable problems. The research didn't find fundamental flaws in how password managers work. It found implementation gaps that can be fixed with more careful security architecture.

Future Improvements and Security Roadmap

Looking forward, password manager vendors are working on several improvements based on this research:

End-to-end verified key recovery will become standard. Instead of the server managing key recovery, the client will verify and control the entire recovery process. The server will be trusted less and the client will be trusted more.

Stronger account recovery authentication will require multiple factors. Recovery won't just accept a recovery key; it will require the recovery key plus email verification, plus device fingerprinting, plus time-based validation.

Holistic vault encryption will become more common. The entire vault will be encrypted as a single unit rather than individual items separately. Clients will cache decrypted vault contents locally for performance, but the server will see only an opaque blob.

Permission verification in sharing will happen at multiple levels. When credentials are shared, the receiving user will need to explicitly accept the sharing. The password manager will verify their identity through secondary channels.

Cryptographic binding of encryption parameters will prevent downgrades. If a vault is encrypted with AES-256, that decision will be cryptographically bound in the vault metadata. An attacker can't modify it to force AES-128 or DES without invalidating the entire vault.

Transparency reports showing which accounts have been accessed, from where, and when. Users will get detailed logs of their password manager activity, making unauthorized access obvious.

Zero-knowledge proofs for verification will allow servers to verify that the client is using the correct encryption without the server ever seeing the decrypted data. The server can cryptographically verify security properties without compromising privacy.

Comparing This Research to Previous Password Manager Breaches

It's worth contextualizing this vulnerability research against the actual breaches that password managers have suffered.

The Last Pass breach (2022) was fundamentally different. In that case, an attacker compromised Last Pass's network, stole encrypted vaults, and then conducted offline attacks against them. The vulnerabilities in that breach weren't architectural weaknesses in the protocol—they were poor security practices by Last Pass (unencrypted metadata, weak encryption for some items, etc.).

This research reveals vulnerabilities that would require active server compromise to exploit, but wouldn't require attacking the encrypted vaults offline.

The 1 Password breach (2023) was relatively minor—an attacker gained access to some customer metadata but not the actual encrypted vaults. The vaults remained secure because of 1 Password's encryption architecture.

This research suggests that 1 Password's architecture, which was robust enough to resist the 2023 breach, is also more resistant to the vulnerabilities these researchers identified.

The Dashlane breach (2022) exposed usernames and hashed passwords but not encrypted vault contents. Again, the vault encryption itself held up even though other parts of the system were compromised.

What's interesting is that actual breaches have largely vindicated the fundamental architecture of password managers: encrypted vaults, even when compromised, remain secure. The vulnerabilities in this research suggest ways to make them even more secure.

In a way, this is good news. The vulnerabilities aren't being used to attack anyone right now. They require sophisticated attack scenarios (server compromise plus exploitation). And they're being fixed. The password manager ecosystem is maturing and adapting.

Should You Switch Password Managers?

This is the question everyone's asking.

Honest answer: probably not, unless you were already considering switching.

If you're using Last Pass, particularly given their history of breaches, switching to 1 Password or Bitwarden might make sense. But the vulnerabilities in this research aren't the strongest reason to switch—the Last Pass breach history is.

If you're using Bitwarden, the fact that it had the most vulnerabilities shouldn't make you switch immediately. Bitwarden is open-source, which means patches are transparent and community auditable. Updates are being rolled out. The open-source model actually gives you more confidence in the security remediation.

If you're using 1 Password, the research showed fewer vulnerabilities, and their response was reassuring. You don't have a strong reason to switch based on this research.

If you're using Dashlane, the vulnerability count is in the middle. Their response to the research will tell you more about whether you should stay or switch.

The key question to ask: what's your password manager's track record on security, and how quickly do they patch when vulnerabilities are discovered? Historical behavior is a better predictor of future behavior than vulnerability counts from a single research project.

The Bigger Picture: Password Manager Security Maturity

These vulnerabilities are evidence of something positive, actually: the security research community is taking password managers seriously as critical infrastructure.

Five years ago, detailed vulnerability research on password manager architecture like this would have been rare. Today, it's becoming standard. Researchers publish papers on password manager security regularly. Bug bounty programs incentivize researchers to find and report vulnerabilities. Security audits of password managers happen frequently.

This increased scrutiny is good. It drives vendors to improve. It surfaces weaknesses before attackers can exploit them. It creates accountability.

Yes, vulnerabilities are being discovered. But the vulnerabilities are being discovered before they're exploited in the wild, which means the system is working. The vendors are patching. Users are updating. The ecosystem is improving.

Password managers are still vastly more secure than password reuse or post-it notes. They're still the best practical solution for managing credentials at scale. And their security is steadily improving as research reveals vulnerabilities and vendors patch them.

Key Takeaways and Action Items

Let's distill this into actionable steps:

Right now:

- Update your password manager to the latest version immediately

- Enable two-factor authentication on your password manager account if you haven't already

- Review your master password—is it strong enough? Change it if necessary

This week:

- Export and review what's actually in your password vault

- Store your account recovery key in a physically separate, secure location

- Check if your password manager has any important security announcements or patch notes

This month:

- Audit your organizational sharing settings—remove credentials you're no longer sharing

- Consider your threat model and whether your current password manager is appropriate

- Review your password manager vendor's response to this vulnerability research

Ongoing:

- Keep your password manager software updated automatically

- Monitor security news for your specific password manager

- Review your password manager's activity logs monthly to spot unauthorized access

- Periodically change passwords for your most critical accounts

Password managers are tools for security, and like all security tools, they require informed use. These vulnerabilities are being fixed. Your responsibility is to keep your software updated and your master password strong.

FAQ

What exactly is a password manager vulnerability?

A password manager vulnerability is a flaw in the system's design or implementation that could allow an attacker to access your encrypted passwords, steal them, modify them, or trick you into storing attacker-controlled credentials. The vulnerabilities discovered in this research ranged from weak authentication on recovery mechanisms to unencrypted metadata that reveals information about your vault contents. The severity varies—some vulnerabilities require the attacker to already have compromised the password manager's servers, while others could potentially be exploited through network positioning.

Do these vulnerabilities mean my passwords have been stolen?

No. There's no evidence that these vulnerabilities have been exploited in the wild to actually steal passwords. These are theoretical vulnerabilities that researchers discovered through code analysis and testing. The vulnerability research was done responsibly—the researchers notified vendors before publishing, giving them time to patch. Your passwords are safe as long as your password manager is running the latest patched version and your master password is strong.

Which password manager is the safest?

Based on this specific research, 1 Password was found to have the fewest vulnerabilities (only 2), and they were both in the backwards compatibility category. However, "fewest vulnerabilities in one research study" isn't the same as "most secure overall." You should also consider historical breach records (Last Pass had a major breach; 1 Password's breaches were relatively minor), transparency about security (Bitwarden is open-source, making patches transparent), and how quickly vendors patch vulnerabilities. For most users, any of the major password managers—1 Password, Bitwarden, Dashlane—with 2FA enabled and regular updates is sufficiently secure.

Should I stop using a password manager?

No. Despite these vulnerabilities, password managers are still vastly more secure than the alternatives (password reuse, writing down passwords, etc.). The vulnerabilities are being patched. The bigger risk for most people is not using a password manager and therefore reusing weak passwords across websites. Keep using your password manager, but make sure you're running the latest version with 2FA enabled.

How long will it take for my password manager to be fully patched?

It depends on your specific password manager and which vulnerabilities affect it. Some vendors released patches within weeks of the research. Others will take longer because they need to coordinate with organizational testing processes and release schedules. 1 Password's response was relatively quick; Bitwarden patches are transparent on Git Hub; Last Pass and Dashlane have been slower. Check your password manager's official website or security announcements for the specific patch timeline. You should update as soon as new versions are available.

If my password manager is compromised, are my passwords guaranteed to be stolen?

No, not necessarily. A compromised password manager server doesn't automatically mean stolen passwords. If your vault is encrypted end-to-end (only your device has the encryption key), the attackers only get an encrypted blob. They'd need to either break the encryption (which is computationally infeasible if it's AES-256) or exploit one of the architectural vulnerabilities to create a back door. This is actually what makes these vulnerabilities significant—they allow attackers to bypass the encryption without breaking it.

What's the difference between these vulnerabilities and the Last Pass breach?

The Last Pass breach was a case where attackers compromised the company's network and stole encrypted vaults. Then they conducted offline attacks against those encrypted vaults, trying to decrypt them. The vulnerabilities in this research are architectural weaknesses that would require active server compromise and sophisticated exploitation. The Last Pass breach showed that encrypted vaults stolen in a breach remain relatively secure. These vulnerabilities suggest ways that a more sophisticated attacker with active server access could circumvent the encryption, rather than just attacking it offline.

Do I need to change all my passwords immediately?

No. You should change your passwords if the vulnerabilities are actively exploited or if there's evidence your specific account was compromised. Right now, neither is the case. What you should do is ensure your password manager is updated and your master password is strong. After patches are released, most users can continue using their existing passwords. Your password manager updates are the priority, not changing every password.

Password manager security is an ongoing process. Vulnerabilities will continue to be discovered. Vendors will continue to patch them. The important thing is maintaining good security hygiene: strong master passwords, two-factor authentication, regular updates, and careful sharing of credentials. Do that, and you'll be in good shape regardless of theoretical vulnerabilities that researchers uncover.

Related Articles

- ShinyHunters SSO Scams: How Vishing & Phishing Attacks Work [2025]

- Machine Credentials: The Ransomware Playbook Gap [2025]

- DJI Romo Security Flaw: How 7,000 Robot Vacuums Were Exposed [2025]

- Vega Security Raises $120M Series B: Rethinking Enterprise Threat Detection [2025]

- VPNs and AI Security: How to Protect Yourself [2025]

- AI Security Breaches: How AI Agents Exposed Real Data [2025]

![Password Manager Vulnerabilities Explained [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/password-manager-vulnerabilities-explained-2025/image-1-1771353529723.jpg)