Photonic Packet Switching: How Light Controls Light in Next-Gen Networks [2025]

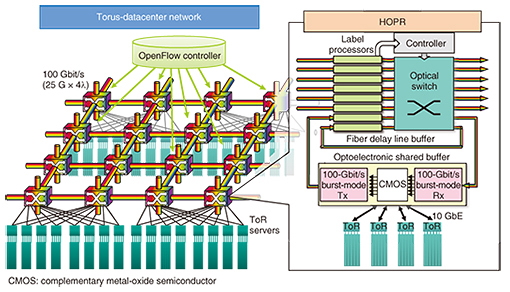

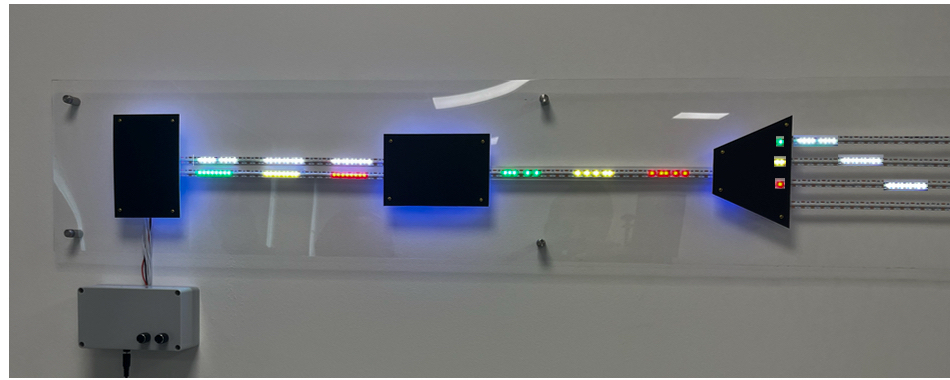

For decades, we've built networks the same way. Data travels as light through fiber optic cables, then gets converted into electrical signals inside switches so processors can decide where to send it, then converts back to light again to continue its journey. It works. But it's inefficient.

That constant light-to-electron-to-light conversion adds latency. It burns power. It introduces failure points. And as AI systems grow more demanding, those inefficiencies are becoming genuine bottlenecks in hyperscale data centers.

A UK-based startup called Finchetto thinks there's a better way. What if switches didn't need to convert light to electrons at all? What if light could control light directly, keeping data entirely in the optical domain?

This isn't science fiction. It's photonic packet switching, and it could fundamentally reshape how the world's largest networks handle data. In an exclusive conversation, Finchetto's CEO Mark Rushworth walked through exactly how this works, why it matters for AI infrastructure, and why the biggest cloud providers are paying attention.

The conversation covers everything from the physics of optical routing to the real-world economics of deploying photonic switches alongside existing equipment. More importantly, it explains why solving network latency might matter more than raw compute power when training the next generation of AI models.

Let's dive into the technology that's about to make traditional network switches look like relics from the broadband era.

TL; DR

- Photonic packet switching eliminates electronic conversions: Data stays as light throughout the network, cutting latency and power consumption dramatically compared to traditional electronic switches that convert light to electrons and back

- AI workloads expose network bottlenecks: Modern GPU clusters move enormous data volumes with tight timing requirements, making network architecture critical—sometimes more critical than compute power itself

- Finchetto's breakthrough is all-optical routing: Unlike legacy circuit switching approaches using mirrors or thermo-optic steering, photonic packet switching makes routing decisions per packet at terabit speeds while keeping everything in light

- Adoption happens incrementally: Data centers can deploy photonic switches phase by phase, improving performance and efficiency over time without ripping out existing infrastructure—critical for billion-dollar operations

- The real win is efficiency at scale: Reduced power consumption, fewer failed components, and the ability to run exotic network topologies create compounding advantages that grow with network size

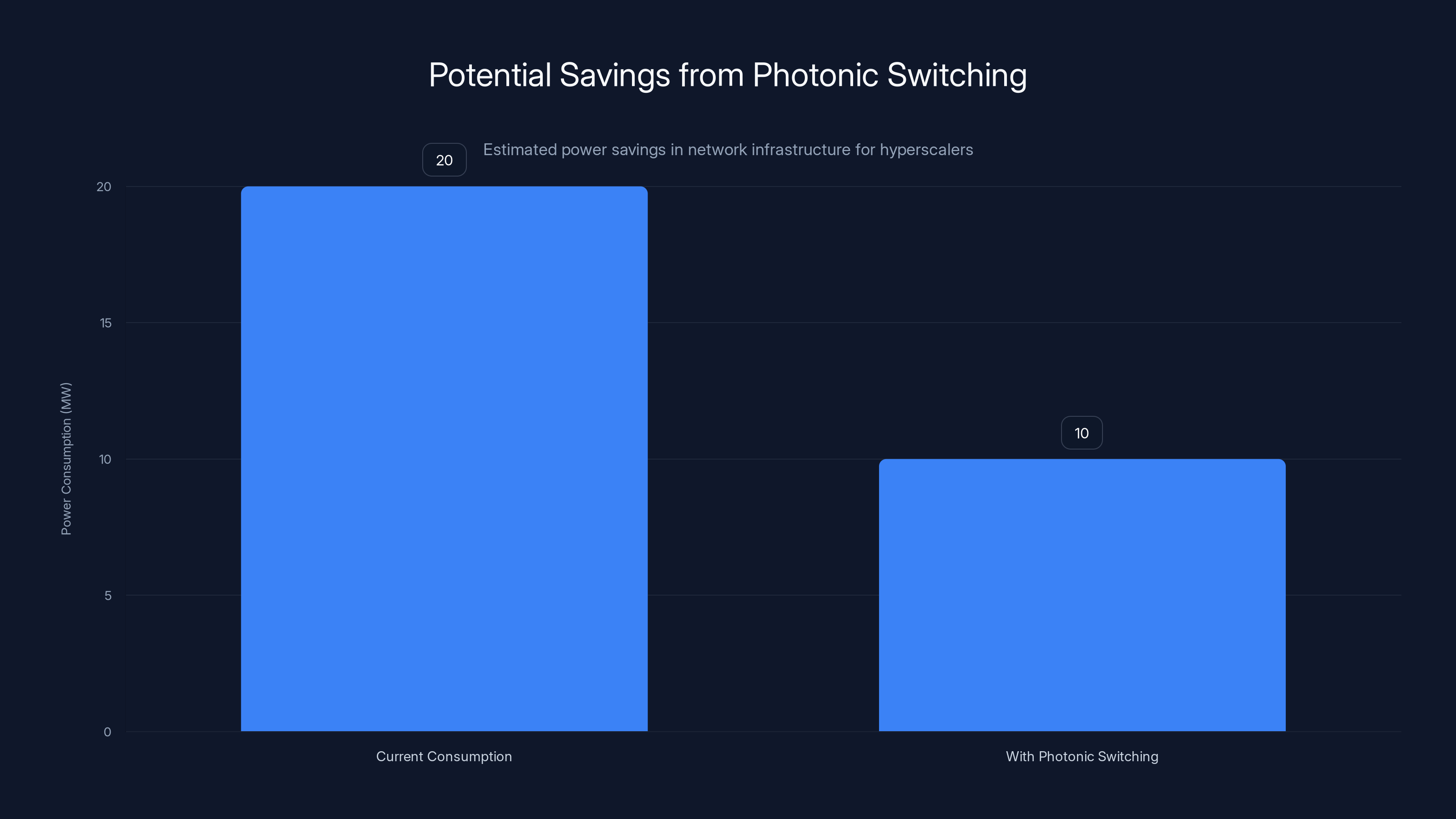

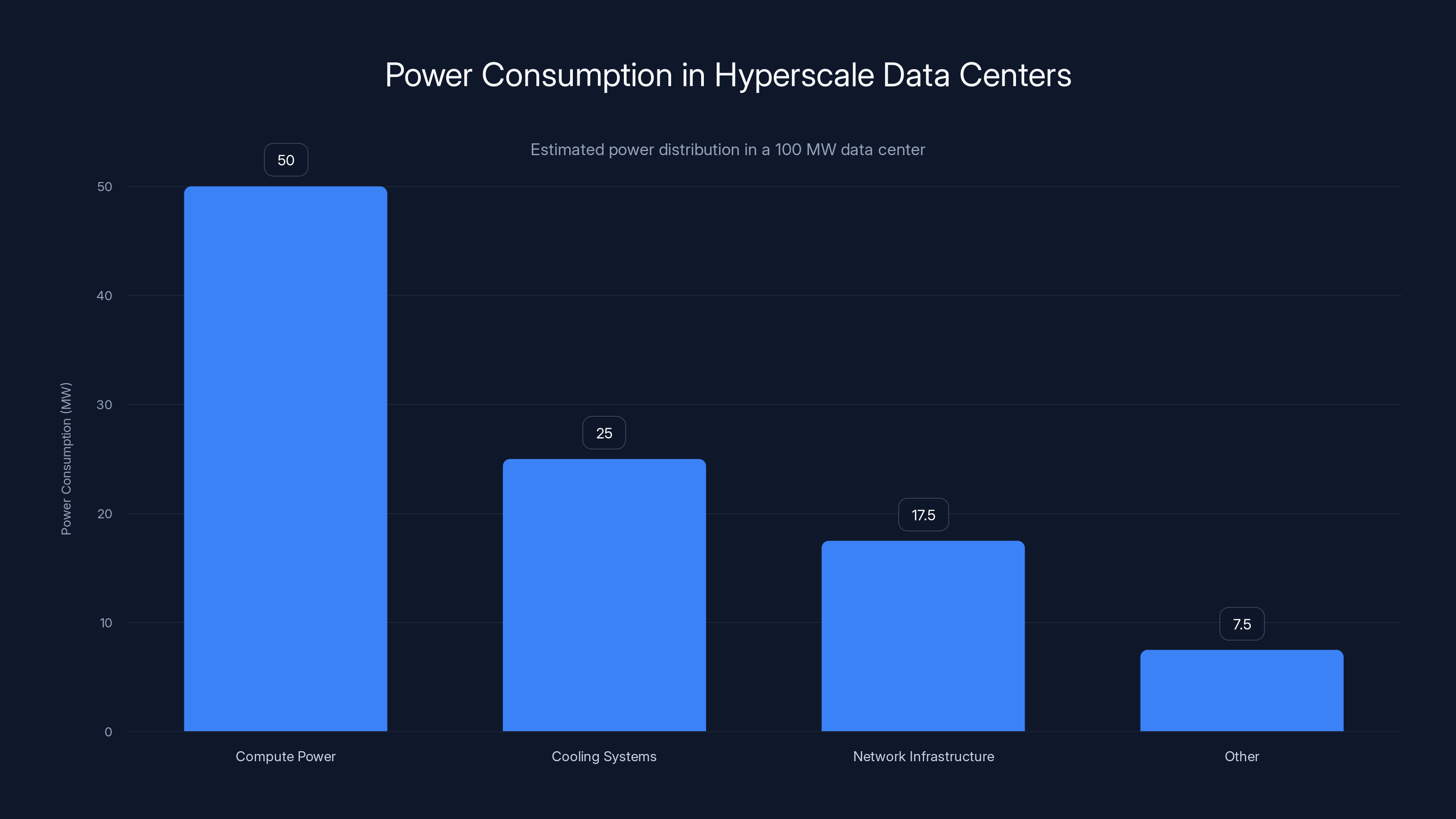

Photonic switches can potentially reduce network power consumption by 50%, saving hyperscalers $700 million annually. Estimated data based on industry trends.

The Problem With Converting Light to Electrons

Here's the thing about modern data center networks: they're weirdly inefficient for a system that handles petabytes of data per day.

A server or GPU generates data and sends it as light through a fiber optic cable. That light enters a switch, where the first thing that happens is electro-optical conversion. The optical signal gets turned into electrical current so a processor can read the packet header, determine the destination port, and figure out where to send it. Once the decision is made, the data gets converted back to light and shipped out on another fiber toward its destination.

This happens millions of times per second in a hyperscale data center. And every single conversion costs something.

The power cost is obvious. Converting light to electrical signals, processing those signals with silicon, and converting back to light requires energy at every step. Hyperscalers pay for electricity by the megawatt. A switch consuming 2 kilowatts instead of 200 watts isn't a nice-to-have optimization—it's tens of millions of dollars annually across a global infrastructure footprint.

But power consumption is only half the problem. The latency is worse.

When you're running AI training clusters, microseconds matter. These systems move terabytes of data between GPUs with synchronization requirements measured in hundreds of nanoseconds. If the network introduces unexpected delays, expensive silicon sits idle waiting for data. That idle time cascades through the entire training job.

Then there's the reliability problem. Electro-optical and optical-electro converters fail more often than pure optical components. Every transceiver in a traditional switch is a potential failure point. More failure points means more maintenance, more downtime, more operational complexity.

So the fundamental question Finchetto asked was simple: what if we didn't have to do all that converting? What if switches could make routing decisions while data stays in the optical domain?

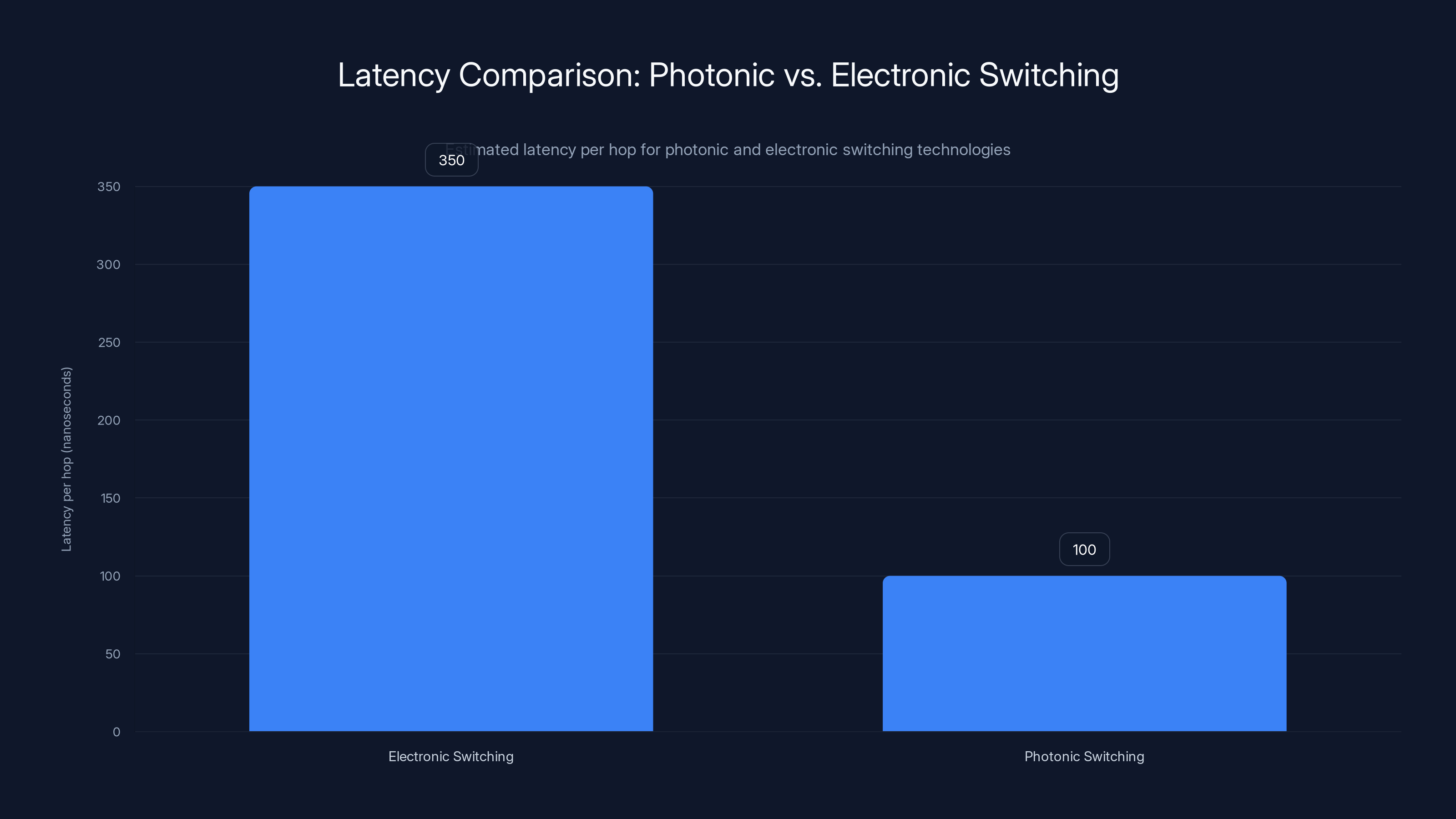

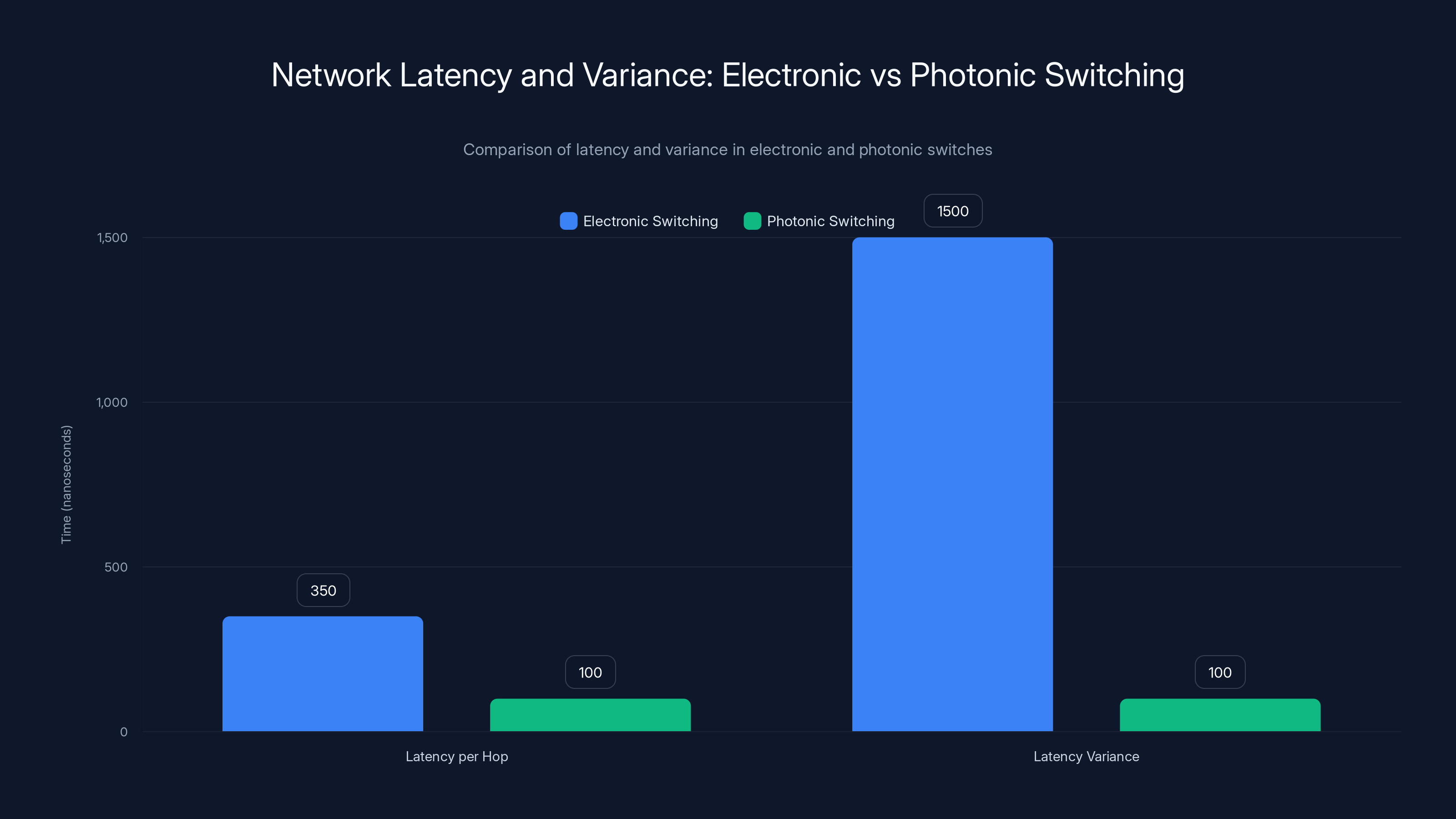

Photonic packet switching significantly reduces latency per hop compared to traditional electronic switching, with estimated values of 100 nanoseconds versus 350 nanoseconds, respectively.

Understanding Photonic Packet Switching: Light Controlling Light

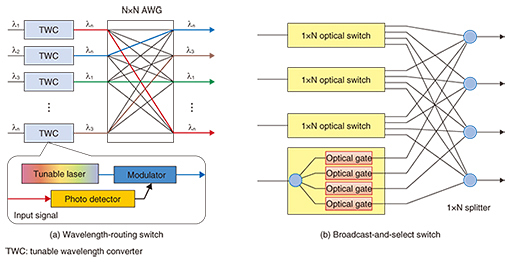

Photonics isn't new. Fiber optic cables have existed since the 1970s. The telecommunications industry has been running photonic networks for decades. But most optical networking falls into one of two categories, and neither solves the conversion problem.

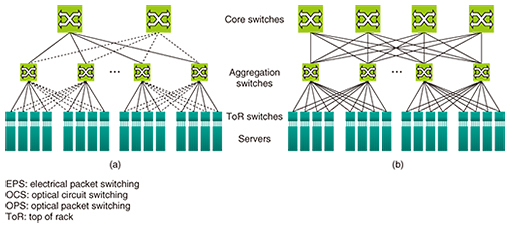

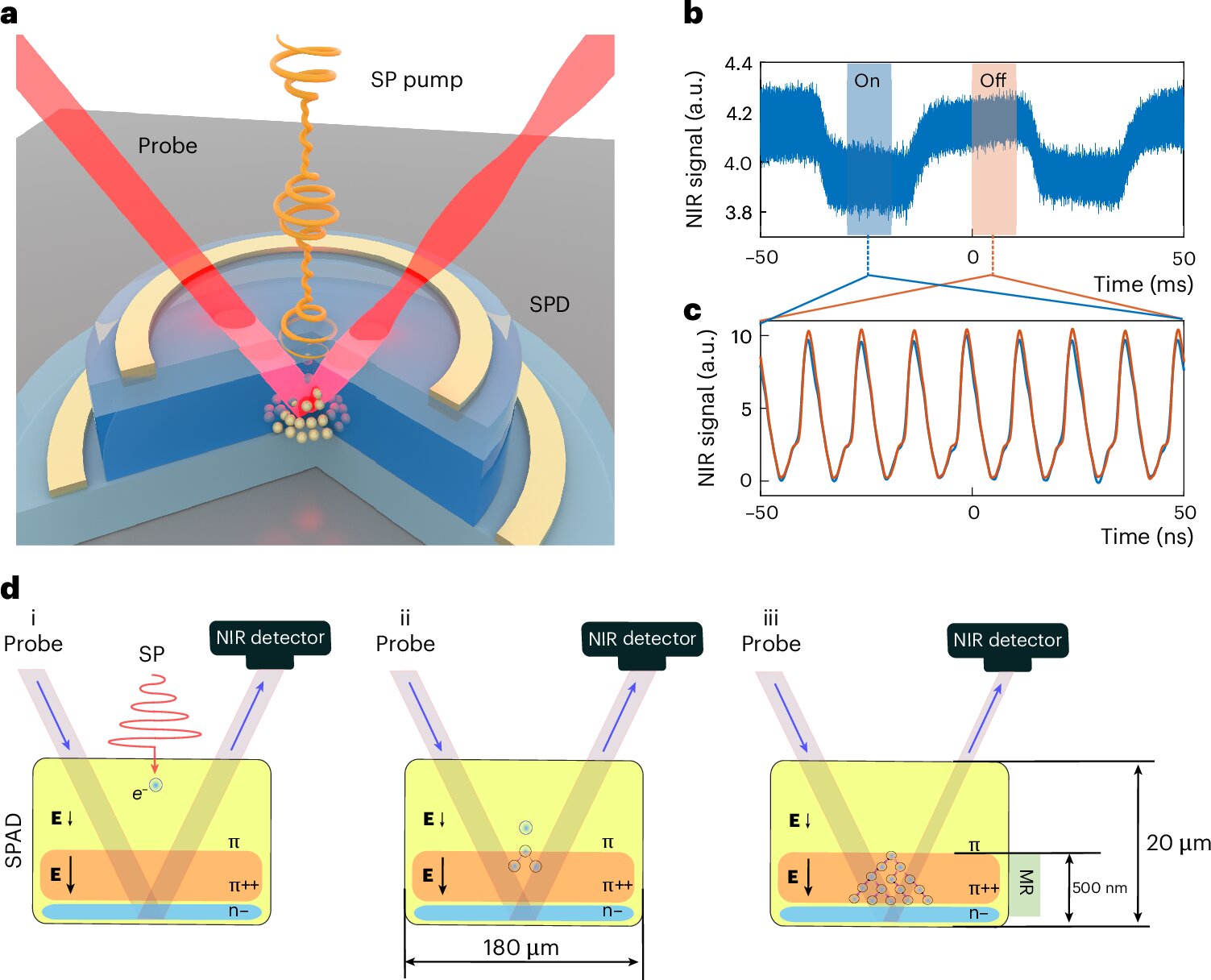

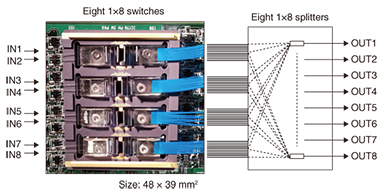

The first category is circuit switching. This is what optical networks traditionally did. A controller sets up a dedicated path between two points—using MEMS mirrors or thermo-optic switches to physically steer light—and that path stays open for as long as the connection needs to exist. Think of it like a traditional telephone switchboard: you dial a number, a connection is made, and that line stays open until you hang up.

Circuit switching works well for long-lived connections that don't need to change frequently. It introduced very little latency once the path was established. But here's the problem: setting up and tearing down those paths takes time. And when you're dealing with modern data center traffic patterns, which involve millions of different packet flows per second, circuit switching becomes a bottleneck.

The packet-switching model is different. In electronic networks, every single packet gets examined. The switch reads the destination address, makes an independent routing decision, and sends that packet where it needs to go. If the next packet in the stream needs to go somewhere different, the switch makes a completely independent decision. This flexibility is why packet switching became the standard for data center networks—it adapts to traffic patterns in real time.

But here's where the problem comes in: to make these packet-by-packet routing decisions, you need to read the packet header. And reading electrical signals is easy. Reading optical signals requires conversion. So every packet switch in a data center has been electronic for this reason.

Finchetto's insight was to ask: what if you could make routing decisions at the optical level without converting to electronics?

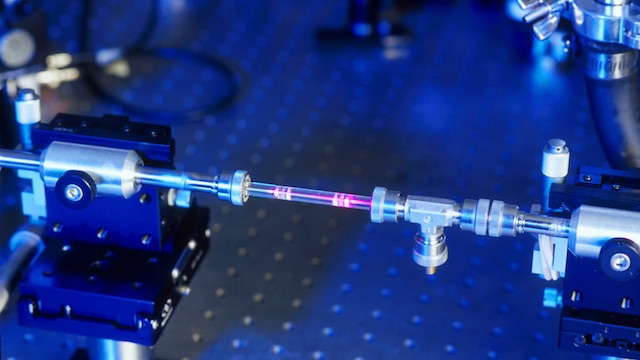

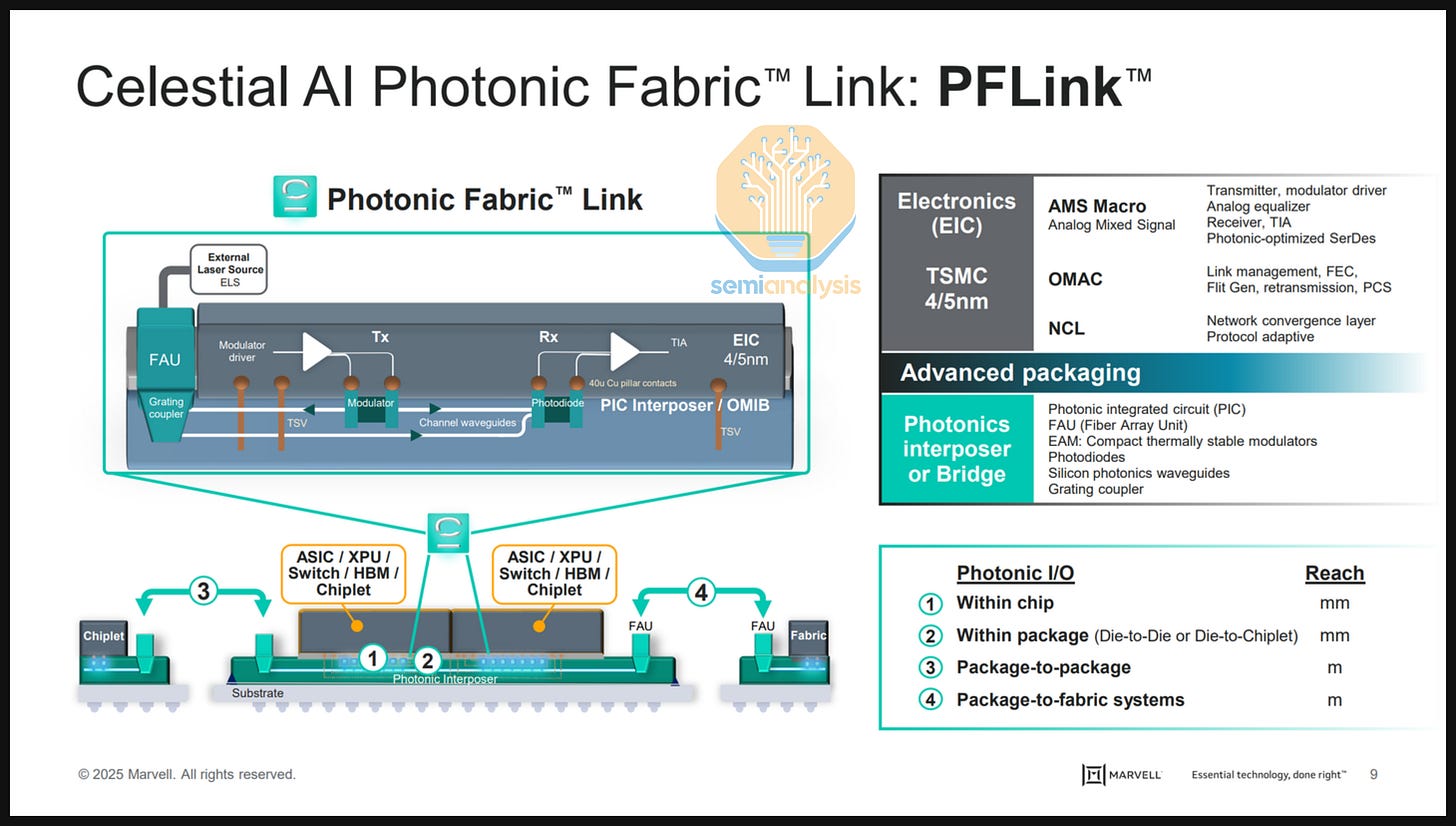

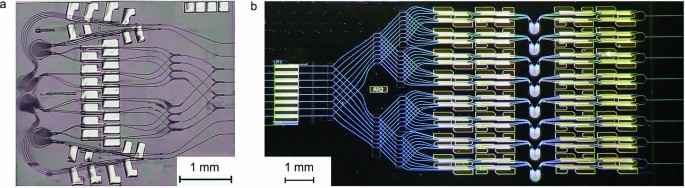

The technology they've developed does exactly that. Using photonic components to manipulate light without converting it to electrical current, they can read optical packets and route them based on their destination address—all while keeping the signal in the optical domain.

This isn't a simple tweak. The physics of manipulating light is fundamentally different from manipulating electrons. You can't just use logic gates and memory the way electronic processors do. Instead, you're working with properties of light itself: wavelength, phase, intensity, and polarization.

Finchetto's approach uses light to control light. Different wavelengths can be used to control which paths other wavelengths take through the switch. By carefully orchestrating light signals, the switch can route incoming packets to the correct output port without ever converting to electronics.

The result is a switch that makes per-packet routing decisions at terabit speeds, introduces minimal latency, consumes minimal power, and stays entirely in the optical domain.

Why Hyperscale Data Centers Are Running Out of Time

If photonic packet switching is so obviously better, you might wonder why it hasn't been deployed everywhere already. The answer is that the pain point hasn't been severe enough—until now.

For the past decade, hyperscale data centers could add compute power faster than network demands grew. Cloud providers would deploy more GPUs, add more switches, upgrade link speeds, and the system would continue to work. It was inefficient, but it was manageable.

AI changed that calculation overnight.

When you're training large language models or running complex inference operations, the network becomes a critical bottleneck in ways it never was before. A single training run might involve hundreds or thousands of GPUs, all simultaneously moving enormous volumes of data through the network with microsecond-level timing requirements.

Consider the math. A single modern GPU can generate 300 gigabits per second of network traffic. An 8-GPU node can saturate several terabits per second. A training cluster with 10,000 GPUs needs a network that can handle petabits of data per second, with latency measured in microseconds, while maintaining synchronization across thousands of devices.

Traditional network architectures start to crack under this load. The switches themselves become a limiting factor. Each hop through a switch introduces latency and reduces throughput slightly. The power consumed by these massive switch fabrics becomes a real operational constraint.

It's not that electronic switches are broken. They're not. But they're beginning to show their limits, and cloud providers are acutely aware that the next generation of AI systems will demand more from the network.

There's also a secondary pressure: competition. When multiple cloud providers are trying to train frontier AI models, the one whose infrastructure can execute training jobs 5% faster has a meaningful advantage. That advantage compounds over time. It affects which models they can afford to train, how quickly they can iterate, and ultimately their competitive position in the AI market.

Photonic packet switching addresses all of these pressures simultaneously. Lower latency. Lower power. Better scalability. And critically, deployable incrementally rather than requiring a rip-and-replace of existing infrastructure.

Photonic switches significantly reduce latency per hop and eliminate latency variance, improving network performance for AI clusters. Estimated data.

How Photonic Switching Improves Network Performance

Let's talk about specific performance gains, because they're substantial.

Latency is the most obvious metric. Electronic packet switches introduce roughly 200-500 nanoseconds of latency per hop. In a typical data center fabric, a packet might traverse 4-6 hops from source to destination. That's 1-3 microseconds of switching latency alone, on top of the propagation delay through the fiber.

Finchetto's photonic switches reduce this to roughly 100 nanoseconds per hop by eliminating the electro-optical conversion step. Across a 6-hop path, that saves roughly 2 microseconds. For a GPU cluster synchronizing across thousands of devices, every microsecond saved is training time recovered.

But latency improvements are just the beginning. The real benefit emerges when you consider latency variance. Traditional switches have relatively consistent latency when they're not congested. But as they approach capacity, latency becomes unpredictable. You'll get 500 nanoseconds most of the time, then suddenly 2 microseconds because the processor is busy handling a packet with a longer processing time.

This variance is devastating for AI clusters. The entire training job runs at the speed of the slowest network roundtrip. If most packets arrive in 1 microsecond but 1% arrive in 10 microseconds due to switch processing variance, the cluster waits for those slowest packets. Keeping signal in the optical domain eliminates the variance—every packet takes roughly the same time to route.

Throughput is another significant factor. Electronic switches have to serializing packet processing to some extent. They read headers, make routing decisions, update statistics, handle exceptions. All of this takes CPU cycles, which create bottlenecks. Photonic switches can route packets completely in parallel using optical components that process multiple packets simultaneously.

In practical terms, this means a photonic switch can handle higher aggregate throughput with the same physical component count as an electronic switch.

Power consumption is where the efficiency gains become truly dramatic. Electronic switches consume power proportional to the number of packets they process. More packets equals more processing equals more power. Photonic switches consume minimal power because they're not converting signals or running processors to make routing decisions.

The power difference scales with link speed. At 100 Gbps per port, the difference between electronic and photonic switching is noticeable. At 1.6 Tbps per port, it becomes a major operational factor. Multiply this across thousands of ports in a hyperscale fabric, and you're talking about tens of megawatts of power consumption difference.

For a hyperscaler operating on a fixed power budget for their facility, that's the difference between running 10,000 GPUs or 11,000 GPUs in the same facility. That's not a small efficiency gain—it's a fundamental shift in how many resources they can deploy.

Reliability and Operational Simplicity

Power and latency get the headlines, but operational teams care deeply about reliability.

Traditional electronic switches are complex systems. Every port has an electro-optical transceiver that converts incoming optical signals to electrical signals. These transceivers are precision components. They drift with temperature. They accumulate wear. They fail at measurable rates.

When a transceiver fails, you lose that port. In a data center network, losing a single port often means rerouting traffic through alternative paths, which consumes bandwidth elsewhere. If the failure happens at a critical location, it can cascade through the network and degrade service to multiple racks.

Photonic switches reduce the number of transceivers needed. Instead of one transceiver per port, a photonic switch processes multiple data streams directly in the optical domain. This eliminates a major failure point and reduces the operational overhead of managing thousands of precision electronics.

Maintenance becomes simpler. No firmware updates to transceivers. No thermal management for processors. No complex synchronization logic to manage packet ordering across multiple processing engines. The switch just routes packets optically and stays out of the way.

For a hyperscaler managing thousands of switches across multiple data centers, this operational simplification translates directly to reduced staffing costs and fewer incidents.

Network infrastructure can consume 15-20% of total power in hyperscale data centers, highlighting the need for more efficient solutions. Estimated data.

Finchetto's Integration Philosophy: Playing Nice with Existing Infrastructure

Here's a reality check that often gets overlooked in technology discussions: hyperscale data centers operate on billion-dollar budgets that took years to deploy. No operator is going to rip out working infrastructure and rebuild from scratch based on a startup's claims about photonic switching.

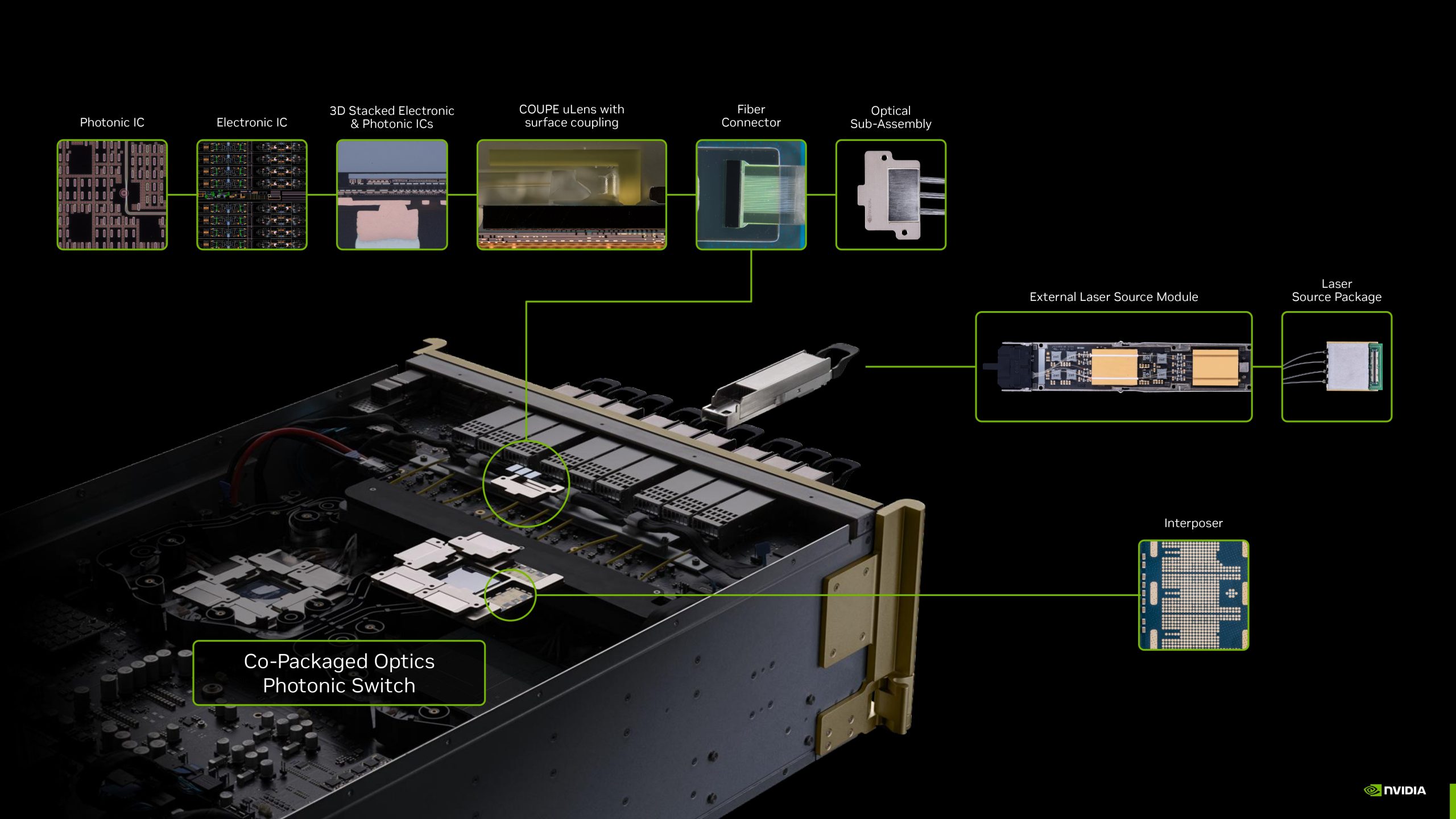

This is why Finchetto's design philosophy matters. From day one, they optimized for incremental deployment alongside existing equipment.

The switches present the same interface to the rest of the network as traditional electronic switches. They speak the same protocols. They integrate with the same orchestration and monitoring systems. From a data center operator's perspective, a photonic switch looks and acts like a very efficient electronic switch.

This matters practically. A hyperscaler can deploy photonic switches in specific parts of their fabric—perhaps in the hottest part of the network where AI training clusters connect—while leaving existing electronic switches in place elsewhere. They can measure performance improvements in real time. They can validate that the switches work reliably with their existing infrastructure. Only after proving the technology in production do they invest in wider deployment.

This staged approach reduces risk dramatically. Instead of betting the entire network on a new technology, operators can start small and scale up as confidence increases.

From a business perspective, it also means Finchetto doesn't need to convince operators to buy 100,000 switches at once. They need to convince them to buy a few thousand to pilot the technology. Once those pilots prove the value, the operators themselves become advocates and drive wider adoption.

The AI Workload Perspective: Why Networks Matter More Than You Think

There's a pervasive misconception in AI infrastructure discussions. The assumption is that GPU performance is the limiting factor. More powerful GPUs equal faster training. So optimization efforts focus on compute.

But conversations with people actually running large training clusters reveal a different reality. GPU compute is rarely the bottleneck. The bottleneck is almost always data movement.

Consider how a distributed training job works. You have thousands of GPUs, each working on a portion of the problem. After each batch of computation, they need to synchronize. GPUs calculate gradients. Those gradients need to move across the network to be aggregated. Updated parameters need to move back to each GPU. Then computation resumes.

The synchronization step—which depends entirely on network speed and latency—determines the overall training speed. If you can shave 100 microseconds off every synchronization, and you do this 10 million times across a training run, you've accelerated the entire training process.

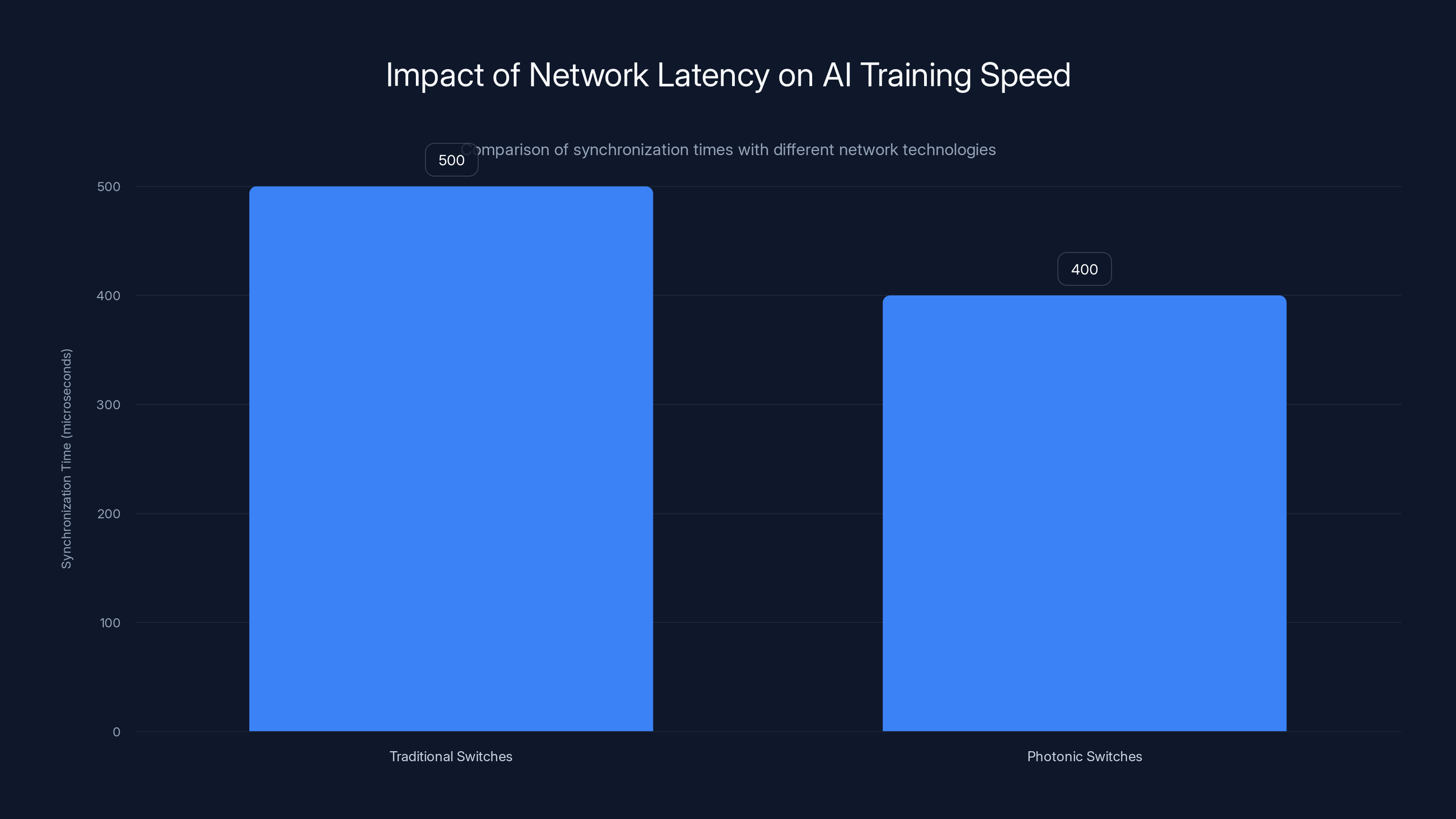

Simplified math: if synchronization takes 500 microseconds with traditional switches and 400 microseconds with photonic switches, and you synchronize 10 million times, that's 1,000 seconds or roughly 17 minutes of training time recovered. On a multi-week training job, that's meaningful.

But the advantage compounds. The same low-latency network that accelerates training also enables different training topologies. With higher latency tolerance, you might be constrained to simple distributed approaches. With lower, more predictable latency, you can use sophisticated topologies like ring allreduce or hierarchical approaches that are more efficient but require tighter timing.

This is why conversations with cloud providers increasingly emphasize network architecture alongside compute architecture. They're recognizing that for frontier AI models, the network is compute. Optimizing the network doesn't just make existing models train faster—it enables new model sizes and architectures that weren't previously feasible.

Photonic packet switching doesn't solve every network problem. But it does eliminate one of the primary sources of latency and inefficiency, allowing architects to design networks that get out of the way of the compute.

Switching from traditional to photonic switches can reduce synchronization time by 100 microseconds, saving approximately 17 minutes in a multi-week AI training job. Estimated data.

Comparing Photonic Switching to Traditional Approaches

To understand why photonic packet switching is significant, it helps to see how it compares to existing technologies that have been trying to optimize network performance.

Traditional electronic packet switching has been the standard for data center networks for 20 years. It works by converting optical signals to electrical, making routing decisions with silicon processors, and converting back to optical for transmission. The technology is mature, understood, and proven at every scale. Its main limitations are power consumption, latency, and limited scalability to higher link speeds.

Electronic circuit switching addresses some limitations by establishing dedicated optical paths that stay optical end-to-end. This eliminates per-packet conversion overhead. But it introduces new problems: slow path establishment, difficulty handling dynamic traffic patterns, and limited flexibility in network topology. A circuit-switched optical network is fast and efficient for stable, long-lived connections, but becomes a bottleneck when traffic patterns change frequently, which they always do in data center environments.

Higher-speed electronics is another approach. Instead of 400 Gbps switches, build 1.6 Tbps switches. Instead of 7-nanometer silicon, use 5-nanometer. Push the boundaries of what electrons can do. This works to a point—and cloud providers are pursuing this aggressively. But there are physical limits. At some point, silicon processors can't make routing decisions faster without consuming prohibitive power. Finchetto's technology approaches the problem from a completely different angle: don't use electrons for routing at all.

Photonic packet switching combines the advantages of both approaches. Like electronic packet switching, it can make flexible per-packet routing decisions that adapt to traffic patterns. Like optical circuit switching, it keeps data entirely in the optical domain, minimizing latency and power consumption. It's neither approach applied harder—it's a fundamentally different approach enabled by advances in photonic components.

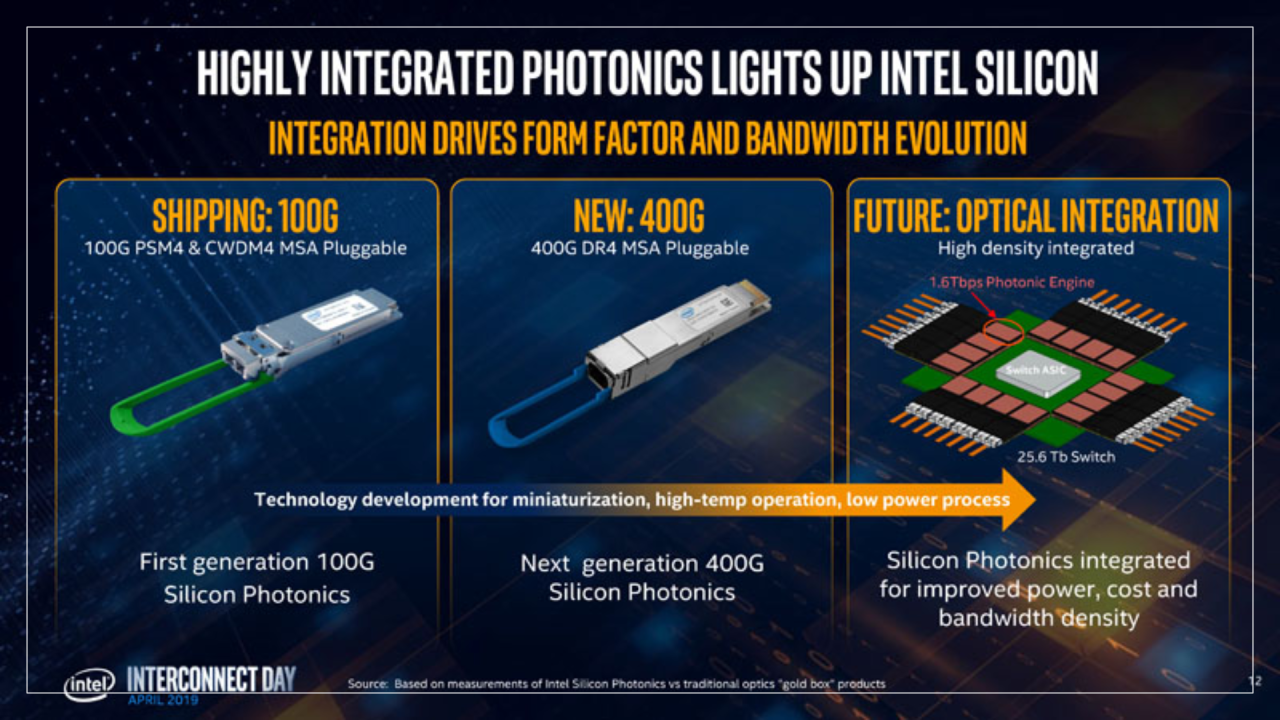

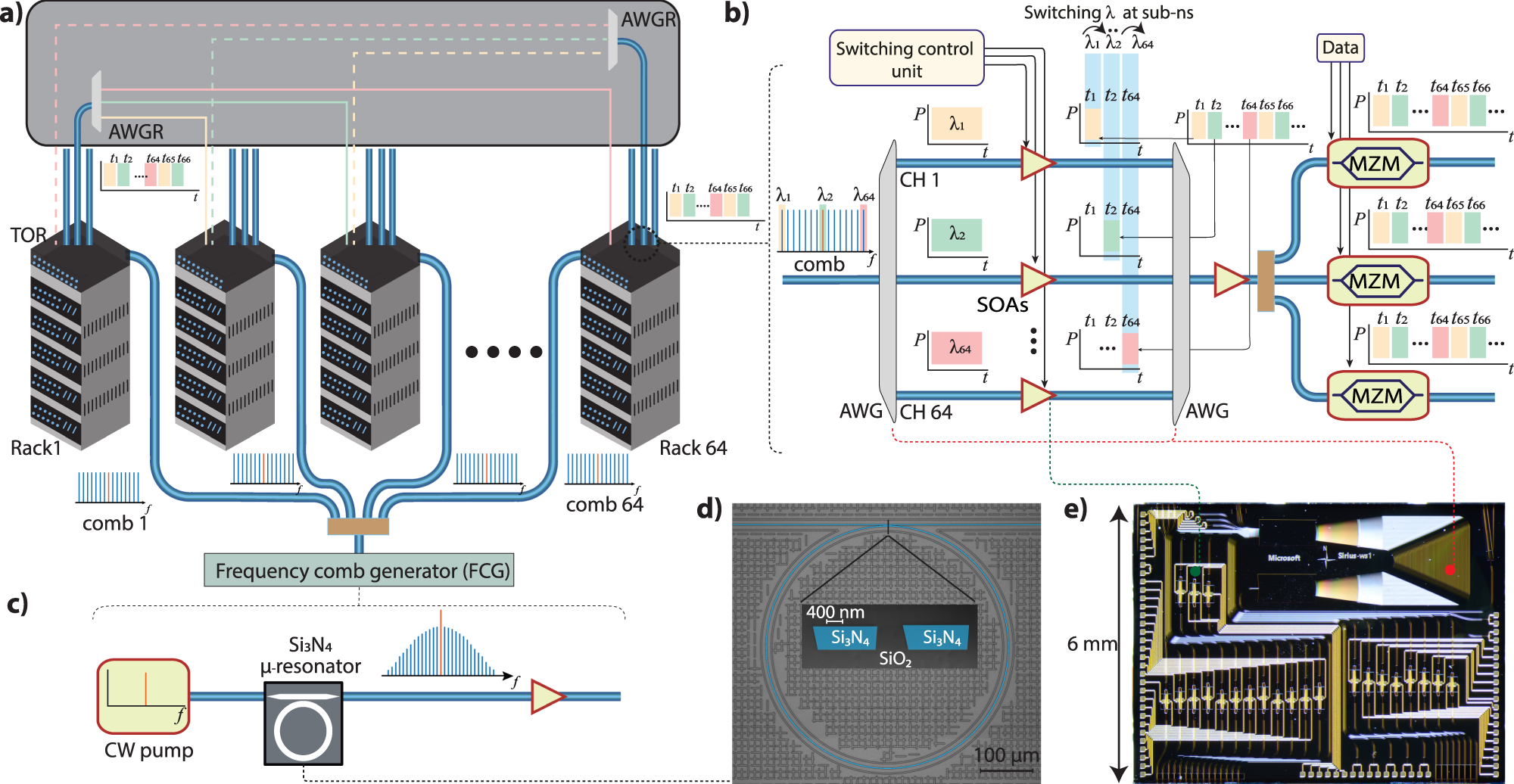

There are other photonic approaches being explored by researchers and startups. Some are pushing on circuit switching, trying to make reconfiguration faster. Some are exploring exotic topologies like silicon photonics that integrate light and electronics at smaller scales. Some are working on wavelength-selective routing where different wavelengths take different paths, allowing some multiplexing benefits.

Finchetto's specific contribution is making photonic packet switching work at the scale and speed required for hyperscale data center networks. It's not the only photonic approach being explored, but it's one of the closest to practical deployment.

The Physics Challenge: Making Light Do Logic

Building a photonic packet switch sounds conceptually simple. Keep data as light, route it optically, and you're done. But the engineering challenge is substantial.

Electronic logic is easy. You manipulate electrical signals using transistors, logic gates, and processors. The fundamental operations—AND, OR, NOT—are straightforward to implement. You build larger systems from these primitives.

Optical logic is different. Light has properties that electrons don't have. You can't just store an optical signal in a register and manipulate it the way you would electrical current. You need to work with the physics of light itself.

To route packets optically, you need several capabilities. First, you need to identify what each packet is and where it should go. This means reading the packet header information while it's still in optical form. You can't convert to electronics and read it that way—that defeats the whole purpose. So you need optical mechanisms to examine optical signals and extract information.

Second, you need to actually switch the signal to different ports based on that header information. You need to physically direct light to different outputs. This can be done with photonic components—switches, couplers, and waveguides—but implementing complex routing logic using optical components is far harder than implementing it with transistors.

Third, you need to handle the fact that light travels at the speed of light. In a traditional electronic switch, you can buffer packets, process them at your leisure, and send them on. With optical packets moving at light speed, you don't have that luxury. Everything needs to happen essentially in real time.

These challenges require innovations at multiple levels. Finchetto had to develop new photonic components. They had to figure out how to encode routing information in optical signals so it can be read and acted upon photonically. They had to solve synchronization problems that don't exist in electronic switches. They had to implement error checking and packet handling in the optical domain.

These aren't theoretical problems. They're practical engineering challenges that took significant work to solve. And they're the reason why photonic packet switching hasn't been deployed widely despite the obvious benefits—it's genuinely hard to build.

But here's where Finchetto's breakthrough matters. They figured it out. They moved from theory and lab demonstrations to something that works at the speeds and scales required for real data centers. That's the engineering achievement that matters.

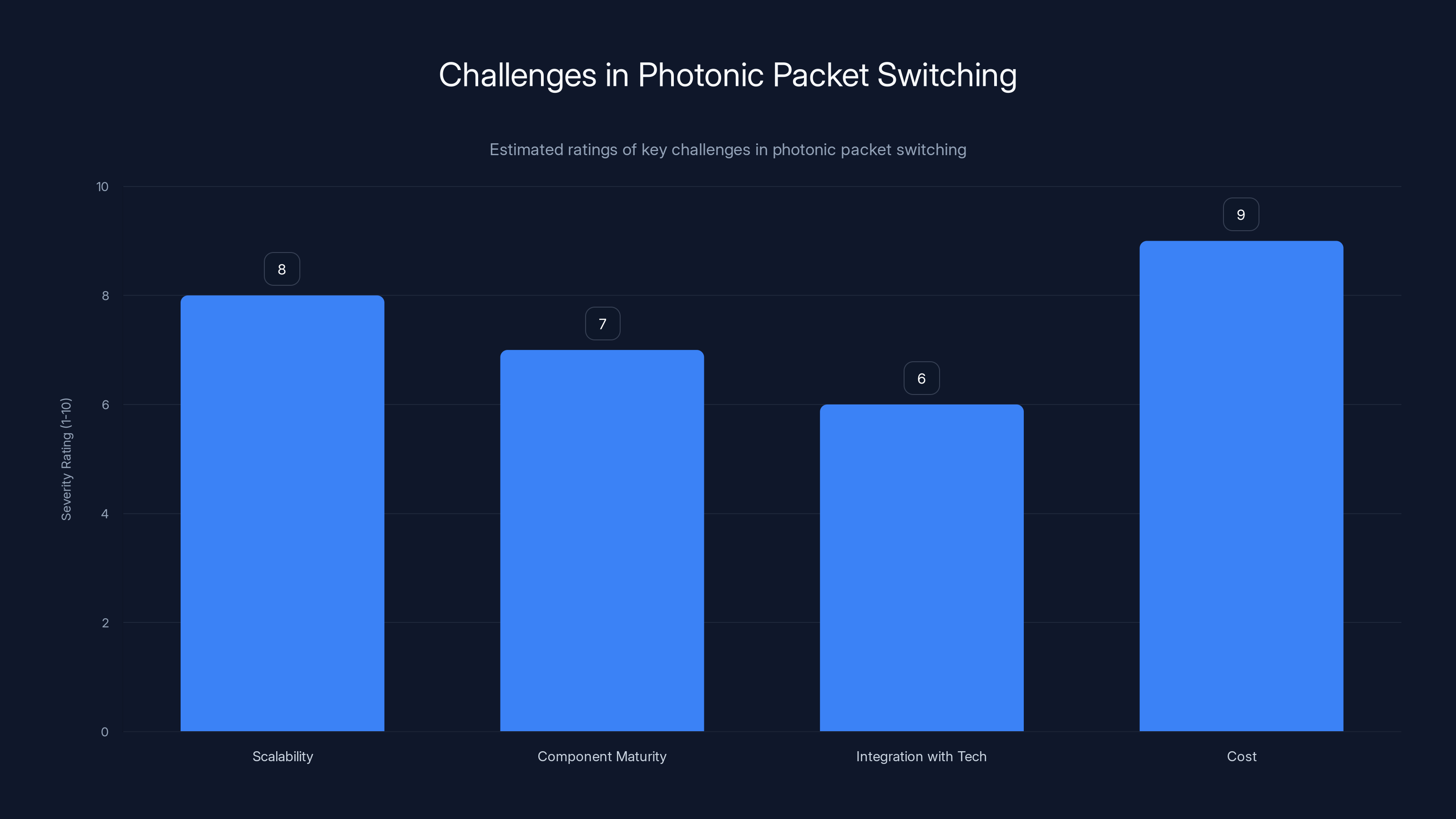

Cost and scalability are the most significant challenges for photonic packet switching, with cost being the most critical. Estimated data based on discussion points.

Real-World Deployment Considerations

Technology that works in labs still needs to work in production. Hyperscale data centers are not forgiving environments. They run 24/7. Equipment failures cause cascading outages. The stakes are measured in revenue impact.

Finchetto has designed their technology with production deployment in mind. The switches need to operate in the temperature ranges and environmental conditions of real data center facilities. They need to integrate with existing management systems that monitor network performance and health. They need to fail gracefully so a failed switch doesn't bring down an entire fabric.

Operational monitoring is critical. Data center teams need to understand what's happening in the network, identify problems, and troubleshoot issues. Traditional switches provide extensive telemetry: packet counts, error statistics, latency metrics. Photonic switches need to do the same, but through different mechanisms since they're not processing packets electronically.

Management and control systems need to work with photonic switches the same way they work with electronic switches. A hyperscaler's network orchestration system needs to be able to program routing policies, monitor switch health, detect failures, and fail traffic over to alternative paths. This isn't just a software problem—it's an integrated hardware-software problem that required significant design work.

Finchetto approached these challenges by ensuring their switches present a compatible interface to existing network management systems. From the data center operator's perspective, the switch looks and acts like a conventional switch, just with dramatically better power and latency characteristics.

This design choice influenced many technical decisions. It meant the switches needed to support the same APIs and protocols as traditional switches. It meant they needed to be compatible with existing monitoring and management tools. It meant they needed to integrate with orchestration systems built to manage electronic switches.

These constraints actually make the engineering achievement more impressive, not less. It's harder to build a new technology that seamlessly integrates with existing infrastructure than to build something that requires a complete redesign. But it's also how transformative technologies actually get deployed in mature, mission-critical environments.

Power Consumption: The Dollar Argument

While latency improvements and technical elegance make good marketing materials, the real business case for photonic switching comes down to power consumption.

Hyperscalers operate at enormous scale. A single data center might consume 100+ megawatts continuously. Some approaching 500 megawatts or more. The annual power bill for a large facility is hundreds of millions of dollars.

Network infrastructure typically consumes 15-20% of total facility power. For a 100 MW facility, that's 15-20 MW going to network equipment. That's not insignificant. Over a year, with power costs around

Photonic switches reduce this by a significant percentage. The exact savings depend on traffic patterns and switch utilization, but industry estimates suggest 40-70% power reduction in network switching fabric compared to electronic switches.

Let's do some napkin math. A large hyperscaler might have 20 megawatts of network power consumption across all facilities. A 50% reduction saves 10 megawatts. At

That's not per-facility savings. That's global savings across a hyperscaler's entire infrastructure. Now, deploying new switches across thousands of facilities has costs too—equipment costs, installation labor, operational validation, and testing. But at that scale of annual savings, the return on investment is measured in months, not years.

For a hyperscaler with tight margins and intense competition from other cloud providers, a technology that reduces operational costs by hundreds of millions annually is not optional. It's a competitive necessity.

This is probably why multiple hyperscalers have been collaborating with Finchetto and other photonic networking companies. It's not about being on the bleeding edge of technology. It's about being able to offer more compute resources at the same cost, which translates directly to competitive advantage.

Network Topology Implications: More Than Just Better Performance

When you remove latency as a constraint, it opens up possibilities that were previously impractical.

Traditional data center networks use spine-and-leaf architectures. Servers connect to leaf switches. Leaf switches connect to spine switches. All traffic between servers in different racks goes through spine switches. It's simple, it works at scale, and with electronic switches, it's the only approach that makes economic sense.

But it's not necessarily optimal. More exotic topologies like torus networks or dragonfly architectures can provide better scaling and lower congestion under certain traffic patterns. They just require lower latency and higher reliability than electronic switches could consistently provide. So network architects designed around the limitations of electronic switching rather than around what would be optimal for the workload.

With photonic packet switching, those exotic topologies become practical. A torus network, where each switch connects to multiple neighbors instead of just spines and leaves, becomes deployable. A dragonfly network, where traffic can take multiple hierarchical paths, becomes feasible. These topologies provide better performance for certain workload patterns that are common in AI training clusters.

This means photonic switches don't just make existing network architectures faster. They enable network architectures that were previously impractical, which can be fundamentally better for AI workloads.

For hyperscalers building new AI training facilities, this is significant. They can design networks optimized for how GPUs actually communicate, rather than optimized for the limitations of electronic switching. The resulting fabric might be 10-20% more efficient at handling synchronization traffic simply because the topology is better suited to the workload.

This compounds with the other advantages. Lower latency plus better topology plus lower power consumption equals networks that fundamentally outperform what's possible with electronic switching.

The Competitive Dynamics and Adoption Timeline

Photonic switching is not a technology that exists in isolation. Multiple companies are working on optical networking solutions. Some are optimizing optical circuit switching. Some are exploring different approaches to photonic packet switching. Some are pushing on electronics to go faster.

This competition is healthy. It means photonic switching will improve rapidly. But it also means adoption won't happen overnight. Hyperscalers need to validate that the technology works at production scale before committing to large deployments.

Finchetto's approach of integrating seamlessly with existing infrastructure gives them an adoption advantage. But they're not the only company pursuing photonic solutions, and they're not the only company trying to optimize network performance.

The adoption timeline probably looks something like this. Over the next 12-18 months, the largest hyperscalers do serious pilots of photonic switching in production environments. They validate performance, reliability, and operational integration. They work through any issues that emerge at scale.

Assuming pilots go well, we probably see initial production deployments starting in 2026-2027. These are probably not massive deployments—maybe 10-20% of a facility's switching fabric replaced with photonic switches. Operators collect real-world data on performance gains, power savings, and operational characteristics.

If real-world deployments confirm pilot results, we start seeing broader adoption around 2027-2028. This is probably when other hyperscalers who aren't doing pilots see competitors deploying photonic switching and feel competitive pressure to deploy it themselves.

By 2030, if the technology proves reliable and the business case holds up, photonic switching probably becomes the default for new large-scale network deployments. Existing electronic switches continue running in other parts of the infrastructure, but new capacity and new facilities default to photonic.

That's a reasonable timeline for a transformative infrastructure technology. It's fast enough to matter—hyperscalers can't wait 10 years for the industry to migrate. But slow enough that the technology can be validated and refined before being deployed at massive scale.

Limitations and Open Questions

Photonic packet switching sounds like a breakthrough, and in many ways it is. But no technology is perfect, and there are genuine questions that need answering before we declare electronic switching obsolete.

Scalability is one question. Electronic switches today can handle thousands of ports at very high speeds. Can photonic switches scale to the same extent? What are the theoretical limits? At what point does the photonic switch become as complex and hard to manage as the electronic switch it's replacing?

Component maturity is another. Photonic switches are more complex systems than electronic switches. They depend on precision photonic components that may not be available in the volumes hyperscalers need. Manufacturing yield and consistency matter enormously—if you can't consistently produce thousands of switches with identical performance characteristics, deployment becomes difficult.

Integration with emerging technologies like in-network computing is an open question. Some research is exploring putting computation into network switches—allowing certain types of computation to happen in the data path rather than requiring data to traverse multiple hops. Can photonic switches support this? What would it look like?

Cost is the elephant in the room. We don't know the actual production cost of photonic switches or how that compares to electronic switches. If photonic switches cost 3x more than electronic switches, the power savings need to be dramatic to justify the investment. If they cost 20% more, they're an obvious choice. The cost-benefit analysis depends entirely on production economics, which probably won't be clear until manufacturing ramifies up.

These aren't flaws in the concept. They're legitimate open questions that will be answered as the technology develops and scales. But they're important to acknowledge. Photonic packet switching is not a done deal. It's a promising technology that needs to prove itself through extended production deployment.

The Broader Context: Networks as Critical Infrastructure

Photonic packet switching is interesting as a technology story. But it's important because it reveals something broader: the network is becoming a critical bottleneck in AI infrastructure.

For years, we assumed compute was the bottleneck. More powerful GPUs equals better AI. That's still true in many contexts. But for large-scale training and inference, especially as models get larger and more complex, the network becomes equally important.

This is actually a return to earlier principles in computer architecture. In the 1970s and 1980s, system architects obsessed over interconnect. How fast can data move between processors? How efficiently? The phrase "memory is the new disk" captured this idea—the constraint was moving data, not doing arithmetic.

AI systems are hitting the same constraint. Doing arithmetic on 1000 GPUs is feasible. Getting data to those GPUs in the right amounts, at the right times, with minimal latency is the hard problem.

Photonic packet switching is one solution to that problem. But it's not the only solution. Other approaches include optimizing application code to communicate less. Redesigning algorithms to tolerate higher latency. Changing how models are trained to reduce synchronization requirements. Building larger models so the ratio of compute time to communication time is higher.

The hyperscalers working on AI are probably pursuing all of these simultaneously. Finchetto's technology is one piece of a larger puzzle. But it's an important piece—it removes a fundamental bottleneck at the infrastructure level.

Looking forward, this raises interesting questions about the future of data center architecture. Will networks eventually be optimized so thoroughly that compute becomes the bottleneck again? Probably not—there will always be tradeoffs. But as networks get faster and more efficient, the optimization frontier shifts. Problems that are impossible today become engineering challenges. Engineering challenges become implementation details.

That's how technological progress works at the infrastructure level. A breakthrough like photonic packet switching moves the frontier. It doesn't solve every problem, but it moves past one set of constraints, revealing whatever was previously hidden beyond them.

Interview Insights: Directly from Finchetto's Leadership

One of the most valuable parts of understanding photonic packet switching is hearing directly from the people building it. Finchetto's CEO Mark Rushworth has been working on this problem for years and has clear thinking about both the technical and business implications.

The core insight from Rushworth is that the problem isn't fundamentally about making switches faster or more efficient. It's about rethinking the entire switching paradigm. Traditional packet switches had to be electronic because reading optical information requires conversion to electrical. But that constraint is removable. Once you can read and process optical packets while they're still light, the entire system becomes more efficient.

Rushworth emphasizes the importance of staying compatible with existing infrastructure. This is not an academic exercise or a research project. This is real hardware that needs to work alongside existing equipment in production data centers. That compatibility requirement drove many design decisions, but it's also what enables practical adoption.

The timeframe for adoption is realistic but not overnight. Rushworth notes that data centers operate on billion-dollar budgets deployed over years. Change happens, but it happens methodically. The pilots happening now with hyperscalers are the critical step. Once those validate in production, adoption will accelerate.

On the question of why now, Rushworth points directly to AI. The demands that AI systems place on networks exposed limitations that existed but weren't critical before. Synchronization latency wasn't important when you had a few hundred servers. It becomes important at thousands of GPUs. Power consumption wasn't critical when networks consumed 5% of facility power. It becomes critical at 15-20%.

AI didn't create the need for photonic switching. It just made that need urgent enough that hyperscalers started actively pursuing solutions. That's always how transformative technologies get adopted—not because they're theoretically interesting, but because they solve a pressing practical problem.

Practical Implications for Different Players

Photonic packet switching has different implications for different groups in the ecosystem.

For hyperscalers, the implications are straightforward: if photonic switching works at scale and the cost-benefit analysis is positive, it becomes an essential part of new infrastructure. The technology is not optional—it's a competitive necessity for operating large-scale AI training systems.

For networking equipment vendors, the implications are more complex. Some vendors will embrace photonic switching and develop products in this space. Others will stay focused on electronic switching and try to optimize there. As with most technology transitions, some vendors thrive and some decline based on whether they're early movers or late to adapt.

For AI systems developers, the implications are mostly about opportunity. Lower-latency networks enable different training approaches and algorithms that weren't previously practical. The constraint that previously forced certain architectural choices is removed, so new architectures become possible.

For startups building AI infrastructure and networking solutions, photonic switching creates both opportunities and challenges. The opportunity is that the networking stack is being reimagined—there are new problems to solve and new companies to build. The challenge is that hyperscale adoption requires vast capital, deep expertise, and tight integration with hyperscaler infrastructure. It's not a market that small startups typically win in directly.

For researchers and academics, photonic switching is a validation that bold approaches to fundamental problems can work. The problem seemed hard because the existing paradigm (electronic switching) was so entrenched. Rethinking from first principles enabled a better solution.

FAQ

What is photonic packet switching?

Photonic packet switching is a networking technology that routes data packets while keeping them in the optical domain, avoiding conversion to electronic signals. Unlike traditional packet switches that convert light to electrical current for processing, photonic packet switches read and route optical packets directly using photonic components, dramatically reducing latency and power consumption while maintaining the flexibility of packet-based routing.

How does photonic packet switching differ from traditional electronic switching?

Traditional electronic switches convert incoming optical signals to electrical current, use silicon processors to read packet headers and make routing decisions, and then convert the signal back to light for transmission. This process introduces latency (200-500 nanoseconds per hop) and significant power consumption. Photonic packet switching eliminates these conversions by making routing decisions entirely in the optical domain, reducing latency to roughly 100 nanoseconds per hop and consuming a fraction of the power of electronic switches.

Why is network latency important for AI training clusters?

AI training clusters require frequent synchronization across thousands of GPUs to aggregate gradients and distribute updated parameters. Network latency directly impacts how long these synchronization steps take, which determines overall training speed. Latency variance is even more critical—if most synchronizations complete in 1 microsecond but occasional ones take 10 microseconds due to switch processing delays, the entire cluster waits for the slowest synchronization. Reducing and stabilizing latency can improve training speed by 5-15% or more, depending on the model and cluster configuration.

What are the main challenges in deploying photonic switching?

The main challenges include developing photonic components that work reliably at the scale required for data centers, integrating with existing network management and orchestration systems, ensuring consistent manufacturing and yield of photonic switches, validating performance in production environments before committing to large deployments, and proving that the cost-benefit analysis justifies investment compared to continuing to optimize electronic switching. The technology also needs to scale to handle thousands of ports while maintaining the power and latency advantages that make it valuable.

How much power can photonic switching save a hyperscale data center?

Photonic switching can reduce network power consumption by an estimated 40-70% compared to electronic switches, depending on traffic patterns and utilization. For a hyperscaler operating at 100 megawatts total facility power with 15-20 MW going to networking (typical proportions), this could save 6-14 MW of continuous power. At

When will photonic packet switching be widely deployed?

Adoption is likely to follow a gradual timeline. Initial production pilots with major hyperscalers are happening now and should validate the technology through 2025-2026. Initial production deployments are likely to begin in 2026-2027, probably representing 10-20% of a facility's switching fabric. Broader adoption across the industry would probably accelerate after 2027-2028 as successful deployments prove the business case. By 2030-2035, photonic switching would likely become the standard for new large-scale network deployments, though existing electronic switches would continue operating in other infrastructure for many years. This timeline is typical for transformative infrastructure technologies that require validation and integration with existing systems.

How does photonic switching affect network topology options?

Electronic switching latency and performance characteristics have forced data center networks into spine-and-leaf architectures, which are simple but not always optimal. With photonic switching removing latency as a constraint, more exotic topologies become practical, including torus networks and dragonfly-style hierarchical architectures. These topologies can provide better scaling and lower congestion under traffic patterns common in AI training clusters. This means hyperscalers designing new facilities can optimize network topology for actual workloads rather than around hardware constraints, potentially improving efficiency by an additional 10-20%.

How does Finchetto's approach integrate with existing data center infrastructure?

Finchetto designed their photonic switches to present the same interface and integrate with existing network management systems as traditional electronic switches. This means hyperscalers can deploy photonic switches alongside electronic switches using existing orchestration and monitoring tools. This compatibility was a deliberate design choice that reduces deployment risk and allows staged rollout rather than requiring complete network redesign. A data center operator sees photonic switches as very efficient electronic switches rather than as a fundamentally different technology requiring new operational processes.

The Future of Network Infrastructure: Optimizing What Matters Most

Photonic packet switching represents a fundamental shift in how we think about network infrastructure at hyperscale. For decades, the constraint was speed. Can we make switches that operate at higher speeds? Can we transmit data faster through fiber?

We solved those problems. Networks today transmit data at terabit speeds. The constraint shifted. Now it's latency and power—can we move data at those speeds while minimizing the time it takes and the energy it consumes?

Photonic packet switching solves those problems by removing the electro-optical conversion bottleneck entirely. It's not a incremental optimization of electronic switching. It's a rethinking of the whole approach based on fundamentally different physics.

But this is probably not the end of the story. As photonic switching becomes mainstream, the constraint will shift again. Maybe it's cost, and the industry needs to figure out how to manufacture photonic switches at lower cost. Maybe it's scalability to even higher speeds. Maybe it's integration with emerging technologies like in-network computing or quantum networking.

Each solution to a major constraint opens up new possibilities and reveals new constraints. That's how technology progresses at the infrastructure level. A breakthrough doesn't answer every question—it answers one critical question, enabling progress on the next set of challenges.

For hyperscalers building AI infrastructure, photonic packet switching is part of a broader trend toward optimizing the entire stack. GPUs are optimized. Memory bandwidth is optimized. Storage systems are optimized. Network infrastructure was the remaining weak link. Closing that gap removes a major limitation on how much AI capability can be deployed in a single facility.

Looking further ahead, the infrastructure constraint will probably become something else entirely. Maybe it's power delivery into the facility. Maybe it's cooling. Maybe it's something we haven't thought about yet. But that's a problem for the next generation of infrastructure engineers.

For now, photonic packet switching is the breakthrough that matters. It's the solution to the network latency and power consumption problems that AI systems exposed. And it's probably one of the key enabling technologies for the next generation of AI capabilities that require even larger training clusters and more efficient data movement.

The technology is real. The business case is real. The hyperscalers are paying attention. What's left is the execution—actually deploying this at scale and making it work reliably in production environments serving the world's most demanding workloads.

That's the next frontier. The physics is solved. The engineering is done. The remaining work is making it real.

Key Takeaways

- Photonic packet switching eliminates electro-optical conversions by keeping data in the optical domain, reducing latency by 60-70% and power consumption by 40-70%

- AI training clusters expose network bottlenecks because GPUs require frequent synchronization with microsecond-level timing precision, making network efficiency critical to overall performance

- Finchetto's technology enables deployment alongside existing infrastructure without rip-and-replace, allowing hyperscalers to improve performance and efficiency incrementally

- Power consumption savings translate to hundreds of millions annually for hyperscalers, making photonic switching a competitive necessity rather than optional optimization

- Photonic switching removes latency constraints that forced networks into suboptimal topologies, enabling exotic architectures like torus and dragonfly networks

Related Articles

- Microsoft Maia 200: The AI Inference Chip Reshaping Enterprise AI [2025]

- Why Agentic AI Projects Stall: Moving Past Proof-of-Concept [2025]

- Modernizing Apps for AI: Why Legacy Infrastructure Is Killing Your ROI [2025]

- Agentic AI Demands a Data Constitution, Not Better Prompts [2025]

- The AI Adoption Gap: Why Some Countries Are Leaving Others Behind [2025]

- Tesla's Dojo 3 Supercomputer: Inside the AI Chip Battle With Nvidia [2025]

![Photonic Packet Switching: How Light Controls Light in Next-Gen Networks [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/photonic-packet-switching-how-light-controls-light-in-next-g/image-1-1769472623296.jpg)