Polish Power Grid Breach: How Russian Hackers Exploited Default Credentials [2025]

On December 29, 2024, something happened that should've been impossible in a modern energy grid. Russian government hackers broke into Polish power infrastructure. And they did it with the digital equivalent of guessing "password 123."

Not "password 123" exactly, but default usernames and passwords. No multi-factor authentication. No network segmentation. Just old infrastructure with security holes wide enough to drive a truck through.

The Polish government's Computer Emergency Response Team released a technical report about the incident in January 2025. What it revealed should shake every energy operator on the planet. This wasn't some advanced zero-day exploit that took years to develop. This was basic negligence combined with nation-state resources. And it worked.

The attackers targeted wind farms, solar installations, and a heat-and-power plant. They deployed wiper malware designed to destroy the systems they compromised. The goal seemed clear: turn off the lights in Poland. Cause chaos. Demonstrate weakness. Maybe inspire copycat attacks across Europe.

They failed to actually disrupt power. But they got close. And the reason they didn't succeed had nothing to do with good security practices. It was luck.

TL; DR

- Russian hackers breached Polish energy infrastructure using default credentials and zero multi-factor authentication, a basic security failure that should be impossible in 2025

- Two Russian hacking groups implicated: Security firms blamed Sandworm (known for destructive attacks in Ukraine), but Polish authorities identified Berserk Bear (traditionally espionage-focused, suggesting mission creep)

- Wiper malware deployed: Attackers attempted to destroy systems at wind and solar farms, rendering control and monitoring systems inoperable, though power wasn't actually disrupted

- Default credentials remain the #1 attack vector: 60% of breaches involve weak or default passwords, making this a persistent systemic vulnerability across critical infrastructure

- No MFA enabled: The absence of multi-factor authentication turned a bad password problem into a complete network compromise, a basic security control available for decades

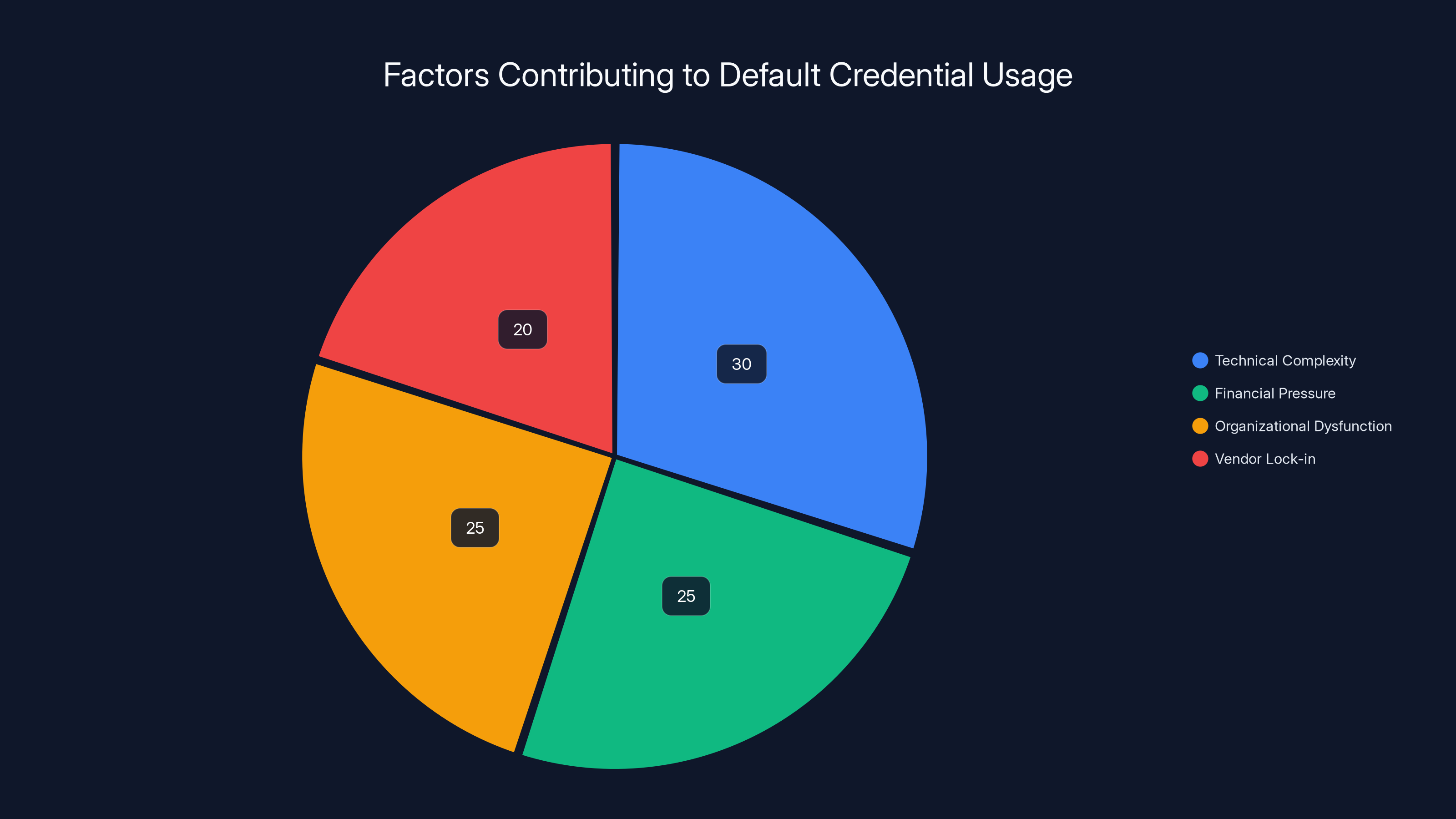

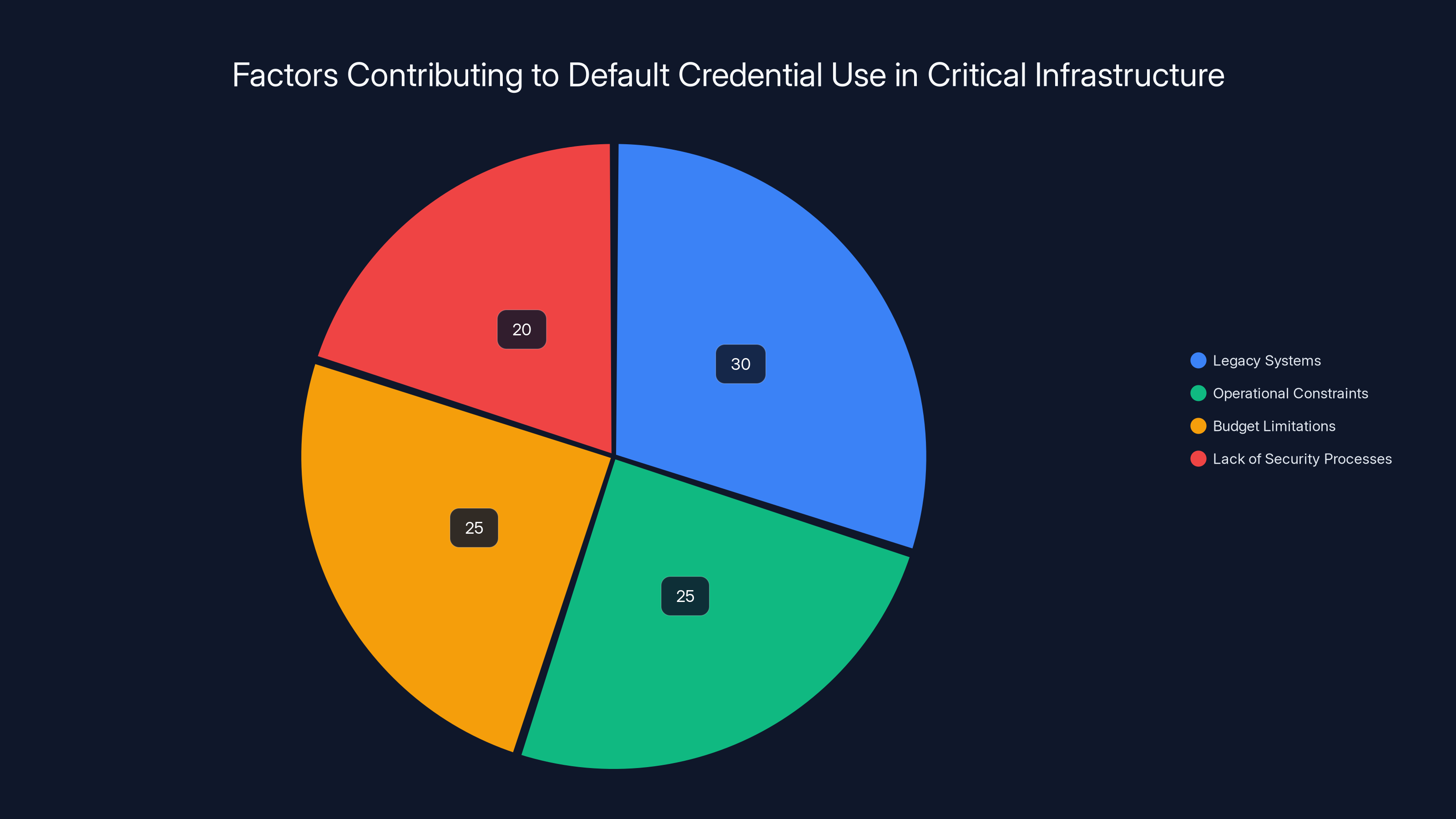

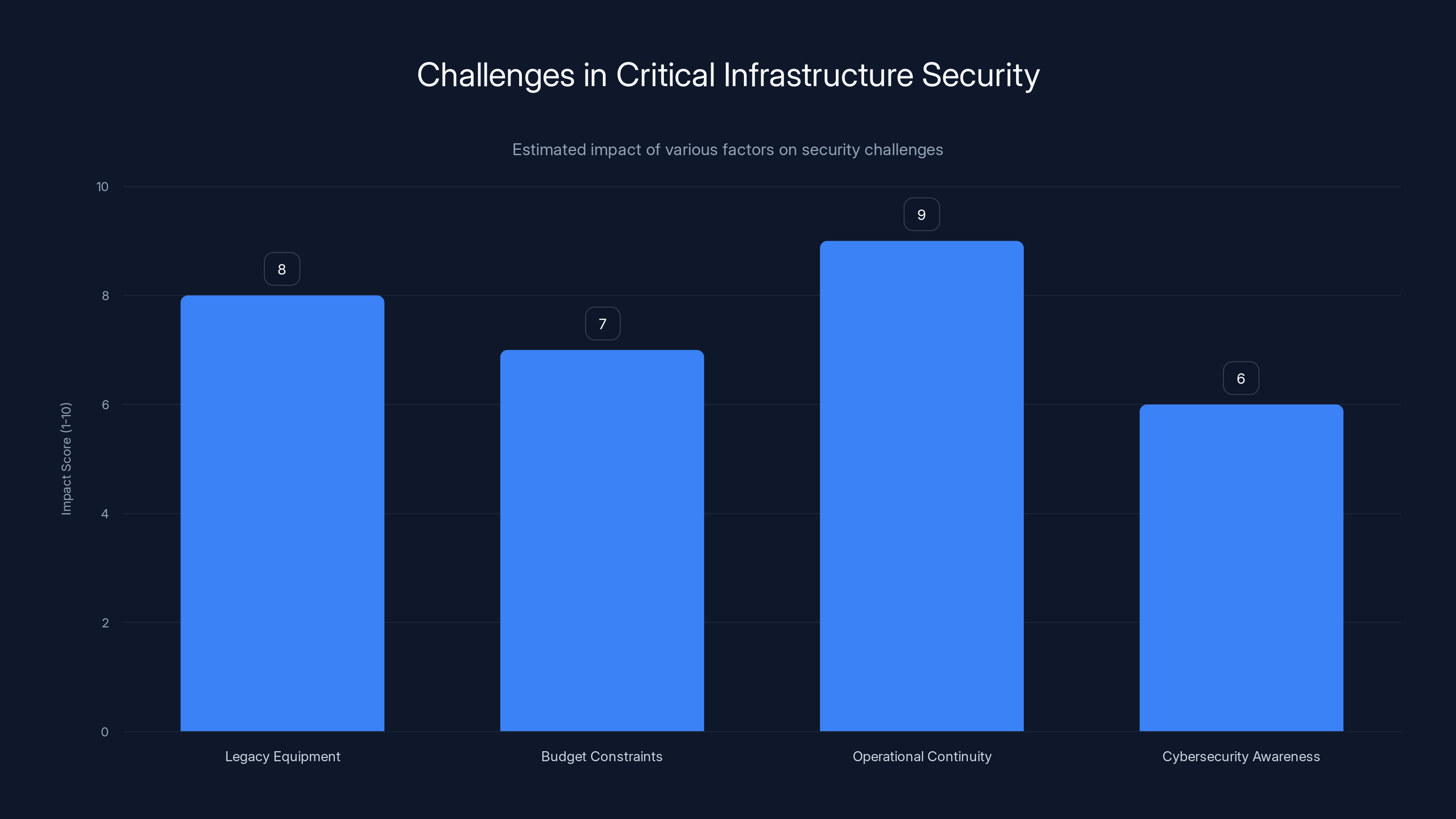

Technical complexity and organizational dysfunction are major contributors to the persistence of default credentials, each accounting for approximately 25-30% of the issue. Estimated data.

What Happened: The December 29 Incident Timeline

Let's talk about the actual attack. Because understanding what went down matters if you're running any kind of critical infrastructure.

On December 29, 2024, someone noticed unusual activity in Polish energy networks. The systems being targeted were part of the country's power generation and distribution infrastructure. Wind farms that feed power into the grid. Solar installations doing the same. A heat-and-power plant that supplies both electricity and heating to customers.

Not the biggest facilities. Not the most critical. But operational infrastructure that people depend on. The kind of place where "down for maintenance" is a real problem.

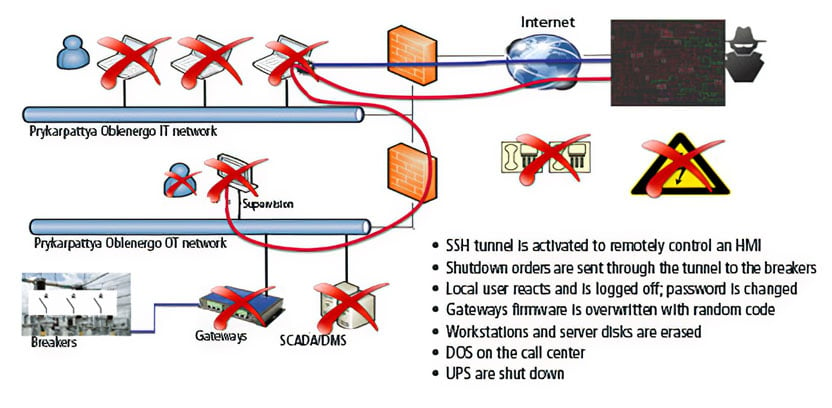

The hackers got in using default credentials. This is important to understand because it's not a failure of cryptography or some obscure vulnerability. It's a failure of basic operations. Someone deployed systems with factory defaults. No one changed the passwords. No one restricted who could access them. This happens more often than you'd think.

Once inside, the attackers deployed malware designed specifically to destroy. Wiper malware. The goal was to erase critical files and render the systems inoperable. Imagine a virus that doesn't steal data or lock files for ransom. It just deletes everything and makes the system unbootable.

At the heat-and-power plant, the attack was stopped. Systems were isolated. The malware didn't spread. Operators noticed something was wrong before irreversible damage happened. They're not entirely sure why the attack failed there, but the isolation worked.

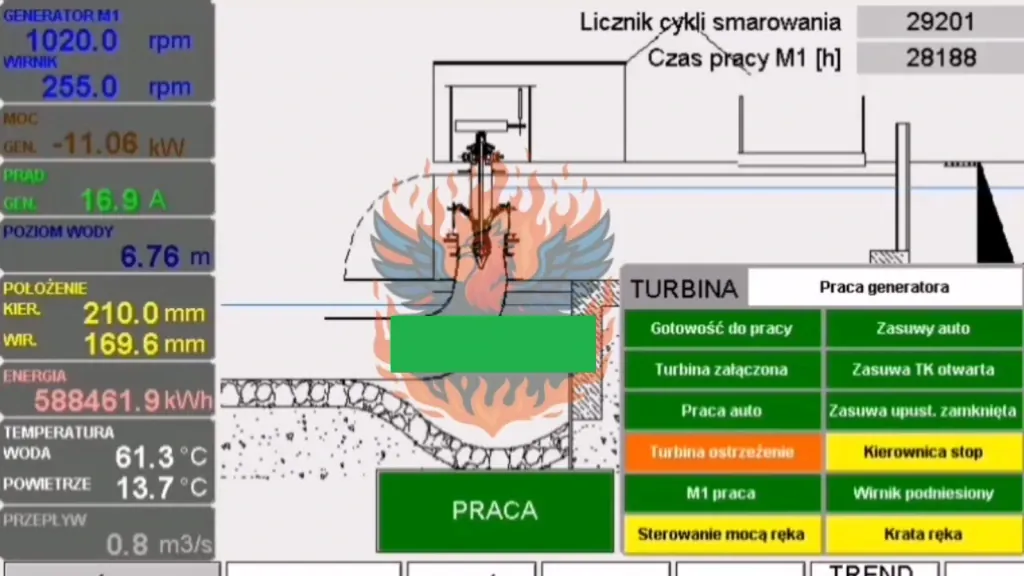

At the wind and solar farms, the story was different. The malware got further. It infected the systems that monitor and control the power flowing into the grid from these facilities. SCADA systems. Industrial control systems. The kind of things you absolutely cannot afford to have compromised.

Once infected, these systems became inoperable. They couldn't monitor power flow. They couldn't make adjustments. They basically became very expensive paperweights.

But here's the thing: the power didn't actually go out. The Polish grid kept running. Why? Because the farms that were hit weren't critical enough at that moment to cause a cascading failure. If the attackers had hit different facilities, or hit at a time when power demand was higher, or if more facilities had been compromised simultaneously, the outcome could've been very different.

The Polish government acknowledged this in their report. The attacks were destructive in nature, but the timing and targeting meant they didn't cause actual blackouts. It was like a arsonist setting small fires that happened to burn out on their own.

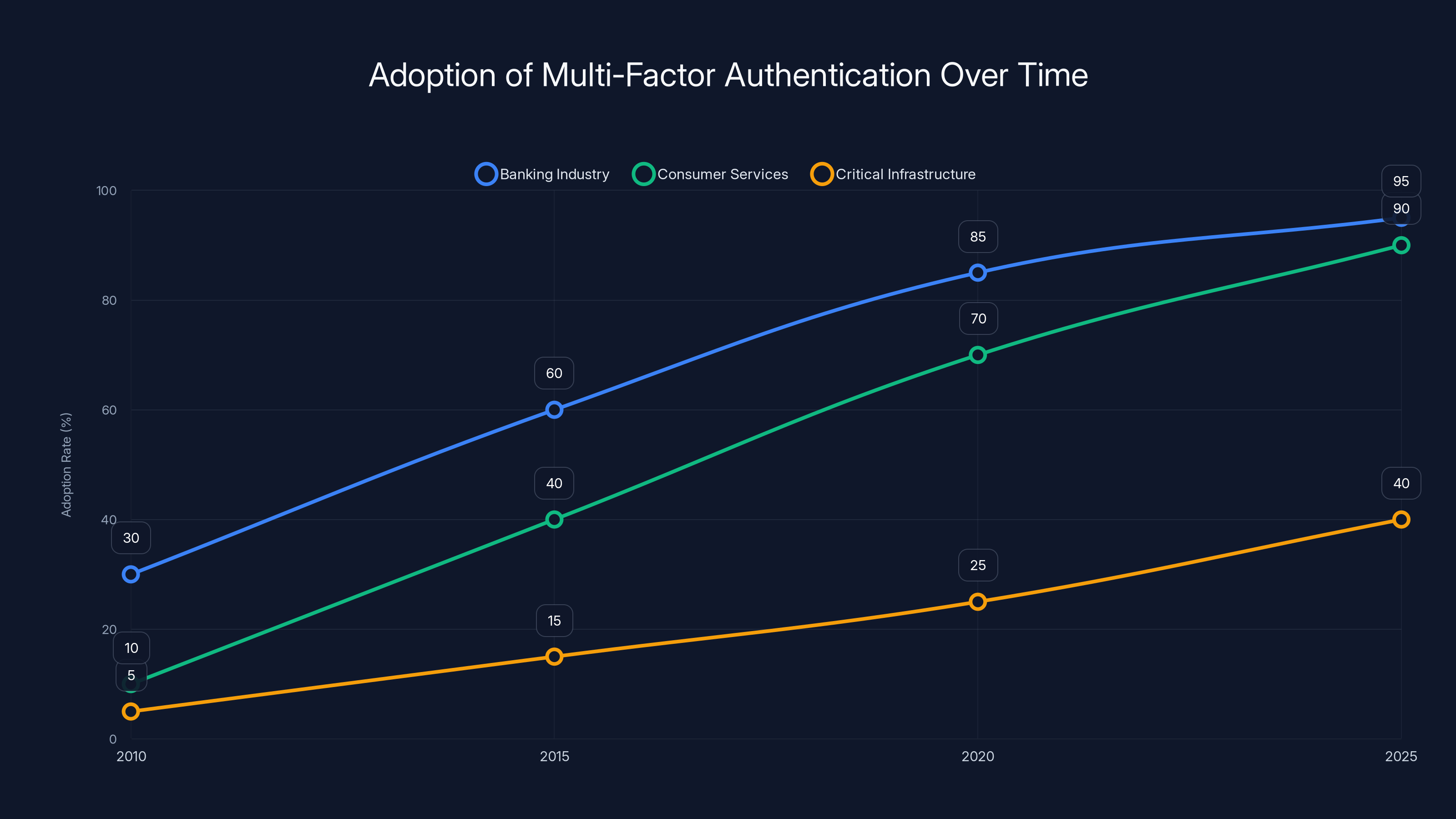

Estimated data shows that by 2025, MFA adoption is nearly universal in banking and consumer services, but lags in critical infrastructure due to operational concerns.

The Culprits: Attribution and the Disagreement

Who did this? That's where things get complicated.

The security research community pointed at Sandworm. ESET and Dragos, two major cybersecurity firms, both published technical analyses. Both concluded that Sandworm was responsible.

This matters because Sandworm has a documented history. They're a Russian government hacking group with a specific, terrifying specialty: turning off power grids. They did it in Ukraine in 2015, knocking out part of the power system during winter. They did it again in 2016. And again in 2022. Each time, the goal was destruction and disruption. Each time, it worked.

Sandworm operates like a military unit. Organized. Coordinated. Willing to take destructive action on behalf of the state. They're not after data theft or fraud. They're after damage.

But then Poland's Computer Emergency Response Team released their analysis. And they said something different. Not Sandworm. They identified the attackers as Berserk Bear, also known as Dragonfly.

Now here's why this matters: Berserk Bear is traditionally a espionage group. They steal information. They establish long-term access. They map networks and gather intelligence. They're the kind of threat that lurks quietly, gathering secrets, not the kind that likes to blow things up.

If Berserk Bear is actually behind the destructive attacks in Poland, that's a significant shift in their operational profile. That's mission creep. That's a group expanding into new territory, new tactics.

The disagreement between these organizations is important because it affects how we understand the threat. Is this Sandworm doubling down on destructive attacks? Or is a different group expanding their capabilities?

Both organizations agree on one thing though: this was a Russian government operation. Not cybercriminals. Not hacktivists. A state actor with resources, intent, and capability.

Why Default Credentials? The Economics of Negligence

Let's get real about why this keeps happening. Because the question everyone asks is obvious: how does a critical infrastructure facility still have default passwords in 2025?

The answer combines technical complexity, financial pressure, and organizational dysfunction.

Energy infrastructure is old. Really old. Many SCADA systems and industrial control systems running in power plants were deployed in the 1990s or early 2000s. They were designed for a different threat landscape. A time when the Internet was smaller, attacks were less sophisticated, and the assumption was that physical security was enough.

These systems weren't built with cybersecurity as a primary concern. They were built to be reliable and to last decades. You don't tear out a SCADA system because of security concerns. That system might keep a power plant running smoothly for thirty years. Ripping it out costs millions and causes disruption.

So you leave it in place. And you layer newer security controls around it. And sometimes, you just accept the risk.

Then there's the human element. Changing default credentials sounds easy. In practice, it's not. Someone has to have credentials that work. Someone has to document what they changed so the next technician can access the system. Someone has to manage access across multiple systems. Do you use different passwords everywhere? The same password everywhere? A password manager?

Many organizations never get this right. They plan to do it. They schedule it. Then something else becomes higher priority. A security patch. A system failure. A storm that demands immediate attention. The credential change gets postponed.

Then years pass. And nobody ever gets around to it.

There's also the vendor lock-in problem. Some equipment comes with default credentials hardcoded by the manufacturer. You can't change them without breaking the system's functionality. You can't patch out the vulnerability. You can only hope no one exploits it.

And then there's the sheer scale of the problem. A large energy utility might operate thousands of systems. Each one potentially with access credentials. Even with the best intentions, keeping track of all of them, ensuring they're all changed, documented, and properly rotated is a monumental task.

The economics are also brutal. Improving security costs money. New hardware. New software. New training. New processes. For a utility company trying to keep costs down for consumers while maintaining aging infrastructure, security often gets the short end of the budget stick.

Multi-factor authentication would've stopped this attack completely. But MFA has costs too. Implementation. Hardware tokens or authentication apps. User training. Support for people who lose their second factor. It adds friction to everyday operations.

When security controls add friction and cost money, they often don't get implemented until after a breach happens.

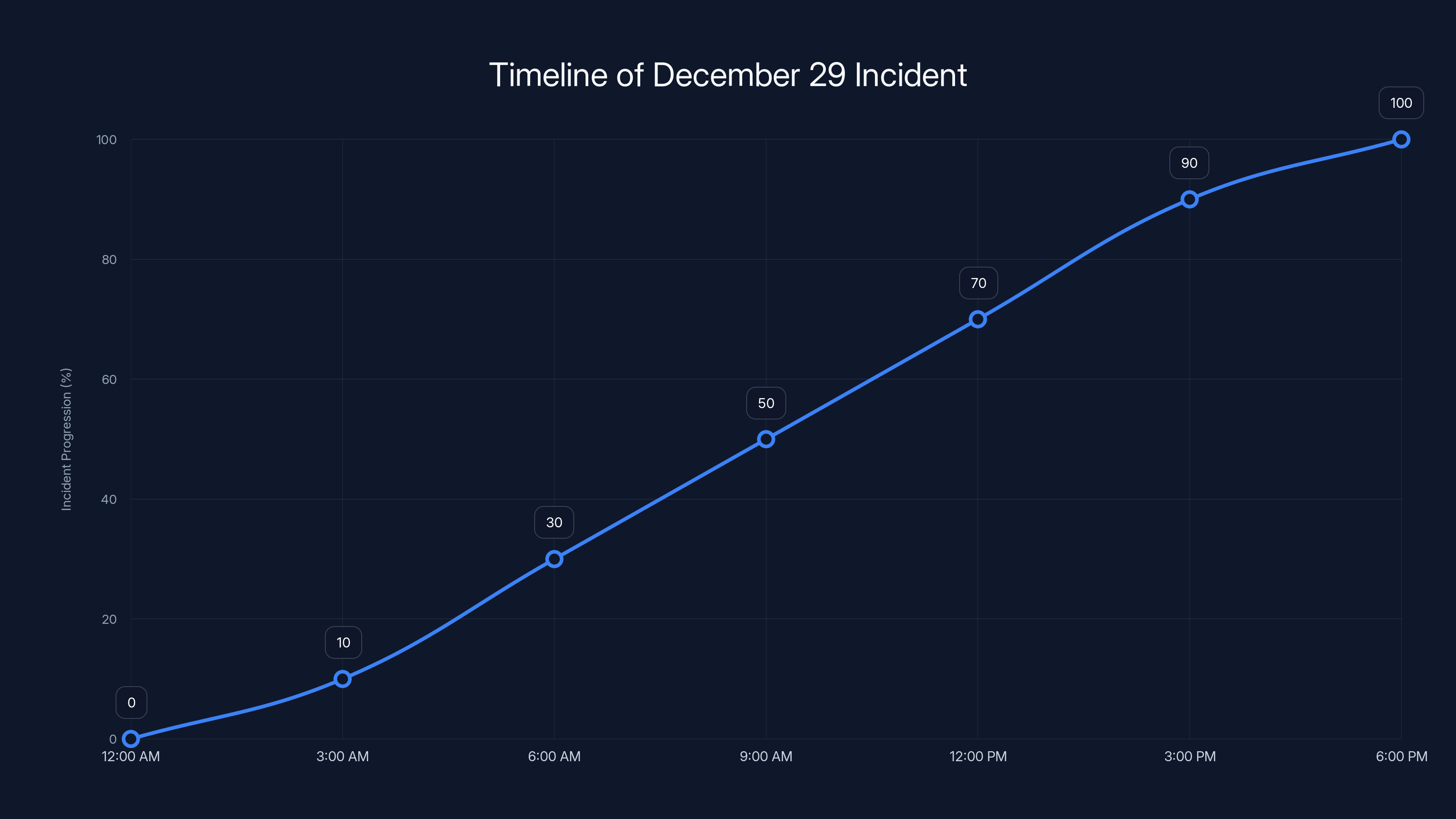

The attack on December 29, 2024, escalated throughout the day, peaking in the afternoon before containment measures took effect. Estimated data.

Multi-Factor Authentication: The Control That Wasn't There

Let's talk about the second failure: the complete absence of multi-factor authentication.

Multi-factor authentication isn't new. It's not cutting-edge. It's not even particularly complicated. It's a second verification step. You enter your password. Then you enter a code from your phone, or approve a notification, or scan a biometric.

It's been standard in the banking industry for years. Consumer services started adopting it in the 2010s. By 2025, it's basically everywhere.

Except critical infrastructure.

The reason is ostensibly reasonable. Critical systems need to work all the time. A blackout is worse than a breach (at least that's the logic). Adding a second verification step creates operational friction. What happens if the authentication system goes down? What happens if a technician loses their phone during an emergency? What happens if the authentication app crashes?

These are real concerns with real consequences. But they're not reasons to skip MFA entirely. They're reasons to design good MFA implementation. Backup tokens. Biometric options. Failsafe procedures.

The Polish facilities had none of this. Just passwords. Just one thing standing between an attacker and complete system access.

Now, here's what's interesting: even with MFA, the attackers probably could've gotten in. They had default credentials, which suggests they had documentation. Maybe they had system specifications, design diagrams, or access procedures. Maybe they had inside information.

But MFA would've created a significant barrier. They couldn't just use the default username and password remotely. They'd need to either compromise the MFA system too, or have the second factor somehow.

That's a meaningful security improvement.

The Wiper Malware: Destructive Intent and Tactics

The malware used in this attack wasn't designed to steal data. It wasn't ransomware trying to extort money. It was wiper malware. Destructive. Purpose-built for damage.

This tells us something important about the attackers' intent. They weren't interested in espionage. They weren't trying to install a persistent backdoor for future exploitation. They wanted to break things.

Wiper malware works by finding critical files and deleting them. Operating system files. Configuration files. Boot records. Anything that makes the system functional. Once infected, the system often becomes completely unusable. Reinstalling the OS and restoring from backups is the only fix.

Different wiper malware variants target different systems. Some focus on Windows systems. Others target Linux. Some specifically target SCADA systems and industrial control systems, which often run proprietary operating systems.

The sophistication here is moderate. Not elite-level hacking. But competent. The malware successfully infected systems, identified critical files, and deleted them. It wasn't defeated by antivirus software (suggesting it was either undetectable or antivirus was disabled or outdated). It propagated from system to system within the networks it compromised.

This is the kind of malware that takes significant forensic work to understand. Where did it come from? How was it deployed? What vulnerabilities did it exploit? How did it move between systems?

Polish authorities would have to conduct deep analysis to answer these questions. The technical details matter because they tell the story of how the attack happened, what tools and techniques were used, and whether these techniques have been used elsewhere.

Wiper malware is particularly dangerous in energy contexts because SCADA systems often don't have good backup and recovery procedures. They're supposed to run forever. The idea of completely wiping a system and rebuilding it from scratch is operationally traumatic.

Default credentials and lack of network segmentation are the most common security failures, occurring in 80% and 70% of cases respectively. (Estimated data)

Why These Attacks Matter: The Broader Context

You might be thinking: okay, this is bad, but no one lost power. No hospitals went dark. No infrastructure failed. Why should we care?

Because close calls are warnings.

Ukraine learned this the hard way. In 2015, when Sandworm turned off parts of the power grid, it was a shock. Nobody thought it could actually happen. Then it happened again. And again. Each time, the attackers learned. Each time, they refined their tactics.

By the time the 2022 attacks came, they were sophisticated and coordinated. Multiple utilities hit simultaneously. Backup systems compromised. The goal was clear: maximize disruption.

Poland is seeing the same pattern start. Russian government hackers are testing Polish infrastructure. Learning its vulnerabilities. Developing access. It might be a months-long reconnaissance campaign. It might be preparation for actual attacks during a conflict.

The timing matters too. This happened in late December, during winter, when power demand is highest and blackouts would cause the most harm. That's not coincidental. That's deliberate targeting.

There's also the European geopolitical context. Ukraine is fighting Russian military aggression. NATO is involved (through support, not direct military engagement). Poland is on NATO's eastern border. It's a staging ground for NATO support to Ukraine. It's also a potential direct conflict zone.

Attacking Polish energy infrastructure serves multiple purposes for Russia. It's reconnaissance. It's intimidation. It's preparing for potential future operations. It's demonstrating that they can reach into European critical infrastructure whenever they want.

That last point is the scariest one. Because if Russian hackers can break into Polish power infrastructure, they can probably break into other countries' infrastructure too. Most energy systems face similar challenges: old equipment, security bolt-ons rather than built-in, limited resources for cybersecurity, and the operational priority of keeping things running over keeping them secure.

The Security Failures: A Detailed Technical Breakdown

Let's deconstruct exactly what went wrong from a security perspective. Because this wasn't one single failure. It was a cascade of failures, each one enabling the next.

Default Credentials in Production

This is the primary infection vector. The attackers started with default usernames and passwords. Not compromised credentials they obtained through phishing. Not passwords they cracked through brute force. Literally the username and password that came with the equipment from the manufacturer.

This should be impossible in any production environment. Every system should have documented credential changes. Every account should have unique credentials. Every change should be tracked in a change management system.

The fact that default credentials existed suggests:

- Systems were deployed without proper configuration

- No one changed the default credentials before going live

- No one ever audited to verify the credentials had been changed

- If audits happened, nobody fixed the failures

- Security processes existed on paper but not in practice

This is organizational failure, not technical failure.

Absence of Network Segmentation

Once the attackers got initial access, they were able to move between systems. They got from one compromised system to another, spreading the malware more widely.

In well-designed networks, this wouldn't happen. Critical systems would sit on separate network segments with controlled access between them. A firewall would enforce which systems could talk to which other systems. Even if one system was compromised, it would be isolated from more critical infrastructure.

The fact that malware could spread from a compromised system to unaffected systems means there was no network segmentation or it was poorly implemented.

Lack of System Hardening

Hardening means removing unnecessary services, disabling unnecessary features, and locking down configuration to only allow what's needed.

Many SCADA systems come with default configurations that include services the operator doesn't actually use. Remote access capabilities. File sharing. Management interfaces. Each one is a potential attack surface.

Proper hardening would mean:

- Documenting which services are actually needed

- Disabling everything else

- Configuring firewalls to only allow necessary traffic

- Removing or restricting user accounts that aren't needed

- Regular verification that configurations haven't drifted

There's no indication the Polish facilities had done this work.

No Multi-Factor Authentication

We covered this already, but it deserves emphasis. A single password is not adequate security for critical infrastructure in 2025. It's not adequate for anything, really.

MFA doesn't have to be complicated. SMS codes are better than nothing (even though security experts dislike SMS for sensitive accounts, it's still better than just passwords). TOTP apps are widely available. Hardware tokens exist.

Implementing MFA for administrative access would've been a significant hurdle for the attackers.

Outdated or Missing Antivirus Software

The wiper malware successfully infected systems. If antivirus software had been properly installed, updated, and configured, it might have detected and blocked the malware.

This suggests either:

- No antivirus software was running

- Antivirus signatures weren't updated

- Antivirus was disabled to improve system performance

- The malware was sophisticated enough to evade detection anyway

Each of these is a systemic security failure.

Inadequate Logging and Monitoring

To detect an intrusion, you need to see what's happening. That requires logging system events and monitoring for suspicious activity.

The Polish authorities detected these attacks, which suggests some level of monitoring existed. But the fact that malware was able to propagate and destroy systems before being stopped suggests the monitoring wasn't comprehensive or responsive enough.

Legacy systems and operational constraints are the leading reasons for the persistence of default credentials in critical infrastructure. (Estimated data)

Industry Context: Why Critical Infrastructure Security Is So Hard

Critical infrastructure is trapped between competing priorities. Understanding why these failures happen requires understanding the operational and financial constraints.

The Legacy Equipment Problem

Power plants, water treatment facilities, and other critical infrastructure often run equipment that's decades old. A SCADA system deployed in the 1990s might still be running perfectly in 2025. Why replace it?

Equipment replacement costs millions. Downtime during replacement is operationally disastrous. Training staff on new systems takes time. Integration with newer systems can be complex.

From an operational perspective, an aging but functioning system is better than a new system with unknown failure modes.

But old systems weren't designed with cybersecurity in mind. They assume physical security is adequate. They assume the network is protected by geography, not firewalls. They might not have encryption. They might not have authentication at all, or just basic authentication.

You can't easily bolt modern security onto a 30-year-old system. You have to work within its constraints.

Budget Constraints

Energy utilities operate on thin margins. They're regulated utilities in many cases, which means their profits and budgets are set by government regulators.

Spending millions on cybersecurity improvements means higher costs, which means either higher consumer bills or lower profits. Neither option is popular with regulators or shareholders.

Security is invisible when it works. Nobody celebrates that your power plant wasn't hacked. But higher electricity bills are very visible.

This creates perverse incentives. Utilities underinvest in security until a breach happens. Then they invest heavily because they have no choice.

Operational Continuity vs. Security

Keeping the power on is the utility's primary mission. Everything else, including security, is secondary.

Security controls that add friction or risk downtime are unpopular with operations teams. An authentication system that requires maintenance windows? Unpopular. A firewall that needs configuration changes? Unpopular. A system hardening effort that could cause unexpected compatibility problems? Very unpopular.

Operations teams have learned through hard experience that changes to critical systems can cause problems. Changing a single configuration might cause an outage. The safer choice, from an operational perspective, is to avoid changes.

This creates a security-operations tension that plays out in actual vulnerabilities.

Regulatory Requirements and Compliance Theater

There are regulations governing security in critical infrastructure. NERC CIP in North America. NIS Directive in Europe. Many utilities follow these regulations.

But regulations create a checkbox mentality. You need to have a firewall? Check. You need to have a security policy? Check. You need to audit compliance? Check.

What you don't always get is actually secure systems. A firewall exists but is improperly configured. A security policy exists but isn't enforced. An audit happens but findings aren't remediated.

Compliance becomes theater. Doing things that look good on paper but don't actually improve security much.

Lessons for Energy Operators: What Should Be Different

If you run energy infrastructure, or any critical system, what should you take from this incident?

Treat Default Credentials as Showstoppers

Before any system goes into production, someone needs to verify that all default credentials have been changed. This needs to be documented. This needs to be audited regularly. This needs to be part of your security acceptance criteria.

If you discover default credentials in your environment, change them immediately. Don't schedule it for next quarter. Do it this week.

Implement Multi-Factor Authentication for All Administrative Access

Every technician or administrator accessing critical systems should require two factors. Not optional. Not for the most important systems only. For everything.

Yes, this creates operational friction. But that friction is vastly preferable to compromise.

Segment Your Networks

Critical systems shouldn't be able to communicate with less critical systems unless absolutely necessary. Use firewalls to enforce this. Monitor traffic between segments.

If someone compromises a less critical system, they shouldn't automatically have access to critical systems.

Implement Continuous Monitoring

You can't defend what you don't see. Implement logging and monitoring across your infrastructure. Monitor for:

- Unusual login attempts

- Failed authentications followed by successful ones (possible brute force)

- Accounts accessed outside normal hours

- Accounts with administrative access doing unusual things

- File deletions on critical systems

- System configuration changes

- Network traffic to unusual destinations

Monitoring needs to be active, not passive. Alerts should trigger investigations, not just create logs to review later.

Create an Incident Response Plan

When an intrusion is detected (and it will happen eventually), you need to know what to do. Who calls who? What systems get isolated? How do you preserve evidence? How do you communicate with regulatory authorities?

Having a plan before an incident happens means you can respond in minutes instead of hours. Minutes matter when wiper malware is deleting files.

Regular Penetration Testing and Vulnerability Assessment

Hire external security professionals to attack your systems. Find the vulnerabilities before attackers do. Then fix them.

This is expensive, but it's cheaper than dealing with a breach.

Backup and Recovery Testing

If wiper malware destroys your systems, your only option is to restore from backups. But backups do no good if:

- They're on the same network and get infected too

- You don't have current backups

- Recovery procedures haven't been tested

- Nobody knows how to do the recovery

Test your recovery procedures regularly. Run full recovery drills. Document everything.

Legacy equipment and operational continuity are major challenges in securing critical infrastructure, with high impact scores. (Estimated data)

The Attribution Question: Sandworm vs. Berserk Bear

We mentioned earlier that security firms disagreed on who was responsible. Let's dig deeper into why this matters and what the disagreement tells us.

Sandworm's Track Record

Sandworm, officially Unit 74455 of the Russian GRU's Main Directorate of Operations, has a clear modus operandi. They target energy infrastructure. They develop sophisticated techniques specifically for attacking power systems. They've caused actual blackouts.

2015: They attacked Ukraine's power grid in the middle of winter using a technique called Black Energy. The attack was sophisticated and coordinated. It worked. Hundreds of thousands of people lost power during freezing temperatures.

2016: They did it again, but more aggressively. This time they used a more evolved version of their malware. They also launched a secondary attack that disabled the data center supporting the power grid.

2022: As Russia invaded Ukraine, Sandworm attacked Ukrainian power infrastructure. They continued attempting to cause blackouts throughout the year.

Sandworm is literally the most effective power grid attack group in the world. They have a 7+ year track record of successful destructive attacks.

So when Sandworm is identified as responsible for an attack on Polish power infrastructure using similar techniques (default credentials, wiper malware, destructive intent), that's cause for serious concern.

Berserk Bear's Profile

Berserk Bear (also known as Dragonfly or Energetic Bear) has a very different profile. They're espionage-focused. They establish persistent access to networks and gather intelligence. They're interested in blueprints, organizational structures, operational procedures, and access credentials.

Berserk Bear has compromised energy infrastructure before, but the goal has always been intelligence gathering, not disruption. They're the group that maps networks and plants backdoors for future use.

If Berserk Bear is behind the Polish attacks, that's a significant change in their operational profile. It would suggest:

- They're expanding their capabilities

- They're shifting from espionage to potentially destructive operations

- They might be coordinating with or taking orders from actors with different objectives

Why Attribution Matters

The difference between these two groups affects threat assessment:

-

Sandworm: We know they're willing to cause destruction. We know their techniques work against European energy infrastructure. We should expect more attacks like this.

-

Berserk Bear: Their expansion into destructive operations suggests widening threat scope. It might indicate organizational changes or new directives within Russian intelligence services.

Either way, the threat to energy infrastructure is real and growing.

The Broader Trend: Increasing Sophistication and Targeting

The Polish incident isn't isolated. It's part of a trend of increasing sophistication in attacks on critical infrastructure.

Increasing Targeting of NATO Members

Attacks on energy infrastructure in NATO members are becoming more frequent. This isn't limited to Poland. Similar incidents have been reported in other European countries.

The pattern suggests reconnaissance. Russian-backed hackers are mapping European energy infrastructure. Learning vulnerabilities. Building access for potential future operations.

This might be purely defensive (improving their own security against NATO). It might be preparation for potential conflict (establishing attack capabilities for wartime). It might be intimidation (demonstrating they can reach critical infrastructure whenever they want).

All of these are concerning.

Increasing Technical Sophistication

Earlier attacks on energy infrastructure used relatively simple techniques. In 2015, Sandworm's Black Energy attack was sophisticated for its time, but it exploited basic vulnerabilities.

Modern attacks show increased sophistication. Better malware. Better exploitation techniques. Better understanding of target systems.

But the Polish incident shows something interesting: even with advanced capabilities, attackers often start with the simplest possible vector. Default credentials. Basic reconnaissance. Obvious vulnerabilities.

This suggests that against properly secured infrastructure, attackers would need to use more advanced techniques. The Polish incident proves that basic security failures are still common, but it also shows what's possible when targets actually defend themselves.

Coordination with State Objectives

Russian attacks on energy infrastructure don't appear random. They align with Russian military and political objectives. Ukraine attacks happen when Russia is conducting military operations. Europe attacks happen during periods of heightened tensions.

This coordination suggests central direction. These attacks aren't rogue hackers or mercenary groups. They're state-directed operations with strategic objectives.

How Energy Operators Should Respond

If you run an energy utility or any critical infrastructure, what's your response to the Polish incident?

First, don't panic. The incident shows that current security practices are inadequate, but it also shows that damage can be limited through basic defenses.

Second, conduct a security assessment. Specifically:

- Audit all administrative access credentials. Change any that are default or shared.

- Verify multi-factor authentication is enabled for all administrative access.

- Test network segmentation. Can one compromised system access critical systems?

- Review monitoring and logging systems. Would you detect an intrusion in progress?

- Test incident response procedures. Can you isolate a compromised system quickly?

- Verify backups are current and tested. Can you recover from a total system wipe?

Third, prioritize fixes based on impact. Default credentials need to be changed immediately. Network segmentation might take months. Plan accordingly.

Fourth, assume attackers are already in your systems. Implement threat hunting procedures. Look for signs of compromise. Look for dormant malware. Look for compromised credentials.

Fifth, increase monitoring. Assume intrusions will happen despite your best efforts. The goal shifts from "prevent all intrusions" to "detect intrusions quickly and respond before damage occurs."

Sixth, communicate with your industry peers. The Energy Information Sharing and Analysis Center, various government agencies, and industry groups share threat intelligence. Use it. Contribute to it.

Government and Regulatory Response

Governments are taking notice of these attacks. They have to. Energy security is national security.

Czech Republic, Poland, other European nations are increasing requirements for critical infrastructure security. The EU's NIS2 Directive sets baseline security requirements for critical sectors including energy.

But regulations alone won't fix the problem. Utilities need funding to implement security improvements. They need time and expertise to deploy them. They need regulatory certainty about security investments (knowing that regulations won't change next year).

Governments should also be improving their own threat intelligence sharing. When intelligence agencies know about vulnerabilities in energy infrastructure, that information should reach utility operators so they can fix vulnerabilities before attackers exploit them.

What's Next: Future Risks and Escalation Potential

Where does this trend go from here?

Russian hackers will likely continue targeting European energy infrastructure. Whether for reconnaissance, preparation for conflict, or actual destructive operations remains to be seen.

Other nations are watching these attacks with great interest. What Sandworm proves possible, other state actors might try to replicate. China's APT10, Iran's IRGC-affiliated groups, and North Korean hackers all have some capability against critical infrastructure.

Meanwhile, the infrastructure itself is evolving. Modern power grids integrate more renewable energy (like the Polish wind and solar farms in this incident). They use more distributed generation. They use more Internet-connected devices.

This modernization provides benefits (renewable energy, efficiency, remote management). But it also creates new attack surfaces.

As power grids become more connected, they become more vulnerable to remote attacks. The transition to renewable energy is inevitable and good, but it comes with cybersecurity challenges that utilities are still struggling to address.

Building Resilient Infrastructure: A Long-term View

Ultimately, resilience against cyberattacks on critical infrastructure comes down to treating security as fundamental, not optional.

Security should be built in from the beginning, not bolted on later. New systems should be designed with threat models and security requirements from day one.

Security should be funded adequately. It's expensive. It's ongoing. It requires skilled people. But not funding security is vastly more expensive.

Security should be operational. It's not something IT people do. It's something the entire organization does. Operators need security training. Managers need to prioritize security. Leadership needs to fund it.

Security should be measured. What are your key security metrics? Are you improving? Are you getting worse? Are you meeting your security objectives?

Security should be assumed to fail sometimes. Intrusions will happen. The goal isn't perfect prevention. The goal is detecting intrusions quickly and responding effectively before they cause major damage.

The Polish incident, despite the damage that could've happened, also demonstrates something encouraging: the attacks were detected. They were stopped before cascading failure. The grid kept running.

That's what we need: infrastructure that's hard enough to attack that most attackers go elsewhere, but also resilient enough to handle intrusions when they happen.

FAQ

What exactly happened in the Polish power grid breach?

Russian government hackers compromised wind farms, solar installations, and a heat-and-power plant in Poland on December 29, 2024. They gained initial access using default usernames and passwords, then deployed wiper malware designed to destroy critical systems. At two of the three locations, the malware was stopped before causing major damage. At the wind and solar farms, the malware successfully rendered control and monitoring systems inoperable, though actual power generation wasn't disrupted because the facilities' timing and criticality meant the outage didn't cascade through the grid.

Why were default credentials still in use on critical infrastructure?

Default credentials persist on critical infrastructure for several reasons: legacy systems designed before cybersecurity was a priority, operational constraints that make system changes risky, budget limitations, and lack of adequate security processes and oversight. Changing credentials requires documentation, access management, and operational procedures, all of which take time and resources that many utilities haven't adequately invested in.

Who was responsible for the attacks: Sandworm or Berserk Bear?

Security firms ESET and Dragos attributed the attacks to Sandworm, a Russian government hacking group with a track record of destructive attacks on Ukraine's power grid. However, Poland's Computer Emergency Response Team identified Berserk Bear (also known as Dragonfly) as responsible. The disagreement matters because Sandworm specializes in destructive attacks while Berserk Bear traditionally focuses on espionage. The identification of Berserk Bear potentially suggests mission expansion into destructive operations.

How could this attack have been prevented?

Multiple preventive measures could've stopped this attack: changing all default credentials before systems went into production, implementing multi-factor authentication for administrative access, segmenting networks so compromised systems couldn't access critical infrastructure, updating antivirus and threat detection software, implementing continuous monitoring and alerting for suspicious activity, and regularly testing backup and recovery procedures. The single most effective control would've been multi-factor authentication.

What does this mean for other countries' energy infrastructure?

This attack demonstrates that Russian government hackers can compromise energy infrastructure in NATO member countries. It's likely reconnaissance for potential future operations, intimidation, or preparation for conflict. Other nations' energy infrastructure faces similar vulnerabilities. Most energy utilities operate legacy systems with inadequate security, default credentials, and insufficient monitoring. This is a strategic vulnerability that affects multiple countries.

How should energy operators respond to this incident?

Energy operators should immediately conduct security assessments focusing on default credentials, multi-factor authentication, network segmentation, monitoring and logging capabilities, incident response procedures, and backup testing. They should change all default credentials immediately and implement MFA for all administrative access within months. They should also assume attackers are already in their systems and begin threat hunting. Incident response procedures should be tested and improved based on the Polish experience.

What is wiper malware and why is it particularly dangerous?

Wiper malware is destructive software designed to delete critical files and render systems inoperable, as opposed to ransomware which demands payment or spyware which steals information. It's particularly dangerous in critical infrastructure because SCADA systems and industrial control systems often lack good backup and recovery procedures. Systems can be permanently damaged, requiring complete replacement or rebuilding from backups, which can take weeks or months. The apparent goal is not financial gain but operational disruption and damage.

What are SCADA systems and why are they vulnerable?

SCADA (Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition) systems are specialized industrial control systems used to monitor and control critical infrastructure like power grids, water systems, and industrial facilities. They're vulnerable because most were designed decades ago without modern cybersecurity features. They often use default credentials, lack encryption, don't support modern authentication, and run proprietary software that's difficult to patch. Replacing them is expensive and operationally disruptive, so many utilities keep aging SCADA systems running indefinitely.

How does this fit into broader Russian cyber operations?

This attack aligns with a documented pattern of Russian government cyberattacks on critical infrastructure. Sandworm successfully attacked Ukraine's power grid multiple times. Attacks on NATO member infrastructure appear to be reconnaissance, preparation for potential conflict, or intimidation. The attacks suggest state direction and coordination with military and political objectives, distinguishing them from criminal activity.

What regulations exist to prevent these kinds of breaches?

Various regulations govern critical infrastructure security including NERC CIP in North America, the EU's NIS2 Directive in Europe, and various national standards. However, regulations often create checkbox compliance rather than actual security improvements. Regulations specify what companies must have (firewalls, policies, audits) but not necessarily how effectively those controls are implemented. The Polish incident suggests current regulations are inadequate at preventing these attacks.

The Path Forward

The Polish power grid breach represents a watershed moment for critical infrastructure security. It proves that nation-state actors can compromise energy infrastructure in developed NATO members. It shows that basic security failures remain common even in critical systems. It demonstrates the potential for destructive attacks that could disrupt economies and endanger lives.

But it also shows that defenses work. The attacks were detected. Most facilities were protected. The grid kept running. With better security practices, these attacks could've been completely prevented.

The challenge now is translating this lesson into action. Energy utilities need to invest in security. Governments need to enforce stronger standards. Operators need to prioritize security alongside reliability.

This won't be quick. It won't be cheap. But the alternative is worse.

Every day, nation-state hackers are mapping critical infrastructure. They're finding vulnerabilities. They're developing capabilities. Some day, probably soon, they'll attempt a destructive attack on European or American energy infrastructure that actually succeeds.

When that happens, the question will be: did we learn from Poland? Or did we ignore the warning?

The answer will determine whether millions of people have power during winter, or whether they don't.

Key Takeaways

- Russian government hackers breached Polish energy infrastructure on December 29, 2024, using default credentials and deploying wiper malware, but attacks were stopped before causing grid-wide disruption

- Default credentials remain the #1 attack vector in critical infrastructure because legacy systems, operational constraints, and budget limitations prevent proper credential management at scale

- Multi-factor authentication would have completely prevented this attack, yet most energy utilities still rely on passwords alone for administrative access

- Attribution to Sandworm (destructive attacks) versus Berserk Bear (espionage-focused) matters because it indicates different threat patterns and potentially mission expansion for Russian hacking groups

- Energy utilities must immediately audit credentials, implement MFA, segment networks, improve monitoring, test incident response, and maintain air-gapped backups as systemic security improvements

Related Articles

- Bumble & Match Cyberattack: What Happened & How to Protect Your Data [2025]

- Device Protection Beyond Hardware: Securing Your Digital Identity [2025]

- Google's War on Residential Proxies: How IPIDEA's Network Collapsed [2025]

- Are VPNs Really Safe? Security Factors to Consider [2025]

- I Tested a VPN for 24 Hours. Here's What Actually Happened [2025]

- Iran's Digital Isolation: Why VPNs May Not Survive This Crackdown [2025]

![Polish Power Grid Breach: How Russian Hackers Exploited Default Credentials [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/polish-power-grid-breach-how-russian-hackers-exploited-defau/image-1-1769792984930.jpg)