RAM Shortage Crisis 2026: How Memory Scarcity Could Bankrupt Companies

Last month, the CEO of one of the world's largest memory chip controller manufacturers dropped a bombshell that barely made headlines outside tech circles. Pua Khein-Seng, the head of Phison, flatly stated that companies could be forced to eliminate entire product lines in the second half of 2026. Worse, some won't survive at all.

This isn't speculation or tech doomsaying. This is a warning from someone who sits at the intersection of hardware manufacturing and global supply chains. Phison makes the controller chips that manage data on SSDs and flash memory devices, which means Khein-Seng sees the supply picture before most of us do.

The RAM shortage isn't coming. It's already here. And what started as a whisper in data centers has become a roar that threatens to reshape the entire consumer electronics market.

Here's what's actually happening, why it matters, and what you need to understand about a crisis that could touch every device you own.

TL; DR

- Phison CEO warns of severe impact: Companies may cut entire product lines in H2 2026; some may face bankruptcy due to RAM scarcity

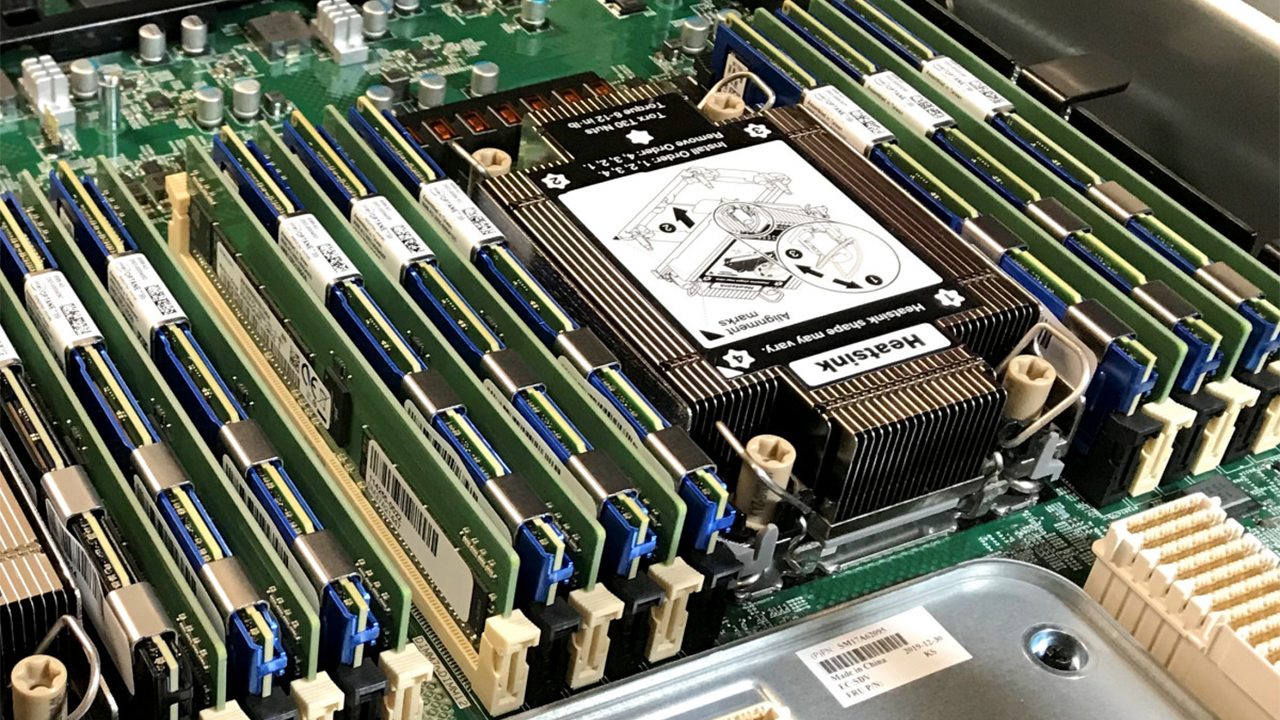

- AI data centers are hoarding memory: These facilities consume the vast majority of global DRAM supply for training and inference operations

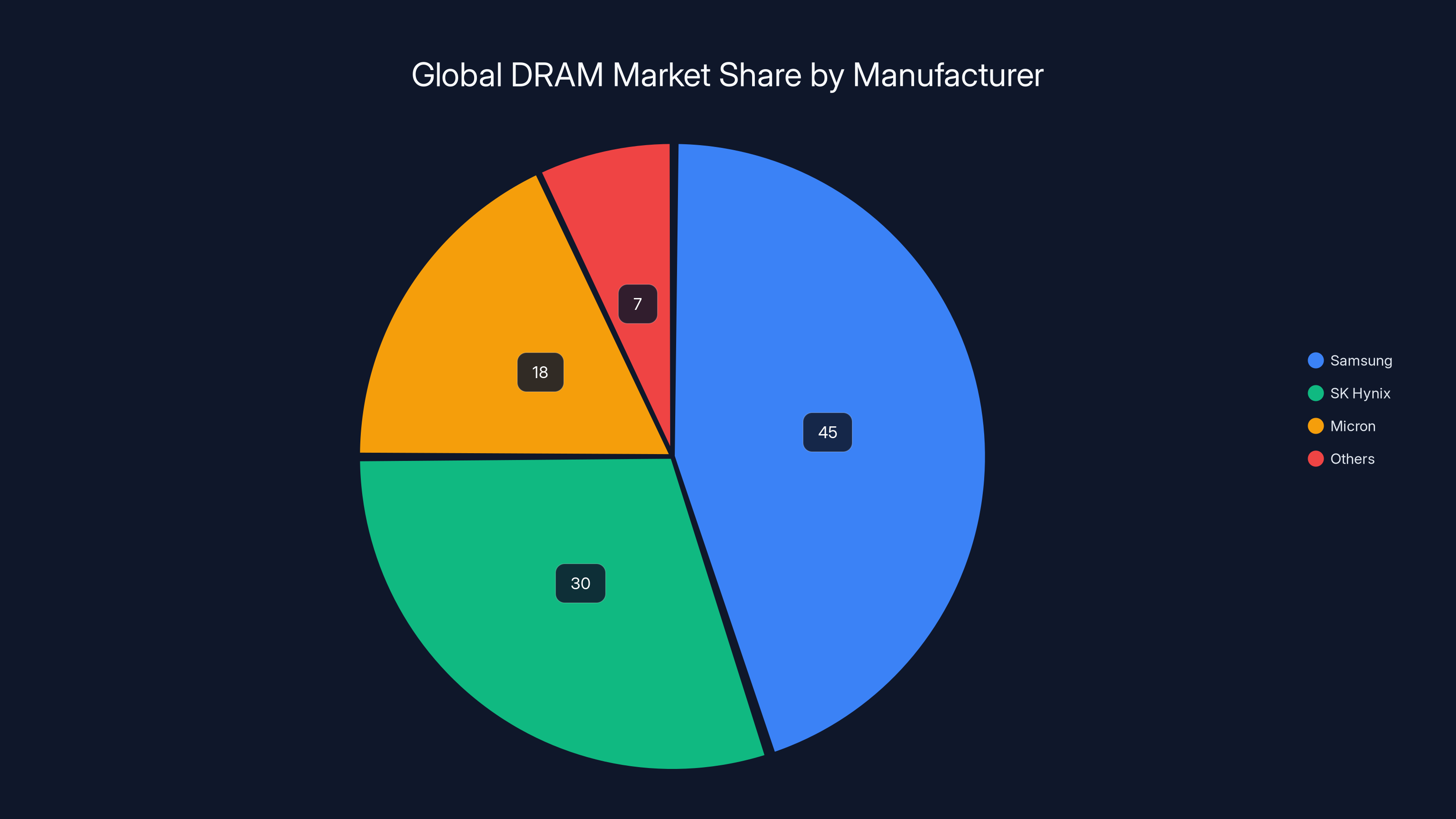

- Supply heavily concentrated: Just three companies (SK Hynix, Samsung, Micron) control 93% of the global DRAM market

- Prioritizing profits over production: Memory manufacturers are deliberately slowing factory expansion to avoid overproduction and maintain higher prices

- Ripple effects everywhere: From smartphones to enterprise servers, every computing device will feel the impact over the next 2-3 years

Samsung, SK Hynix, and Micron control 93% of the DRAM market, allowing them to manage supply and prices effectively. Estimated data.

What's Actually Happening to RAM Right Now

The current RAM shortage is unlike anything the industry has seen before. This isn't a temporary disruption caused by a factory fire or logistics bottleneck. This is a structural imbalance in supply and demand that's being deliberately maintained by the companies controlling the market.

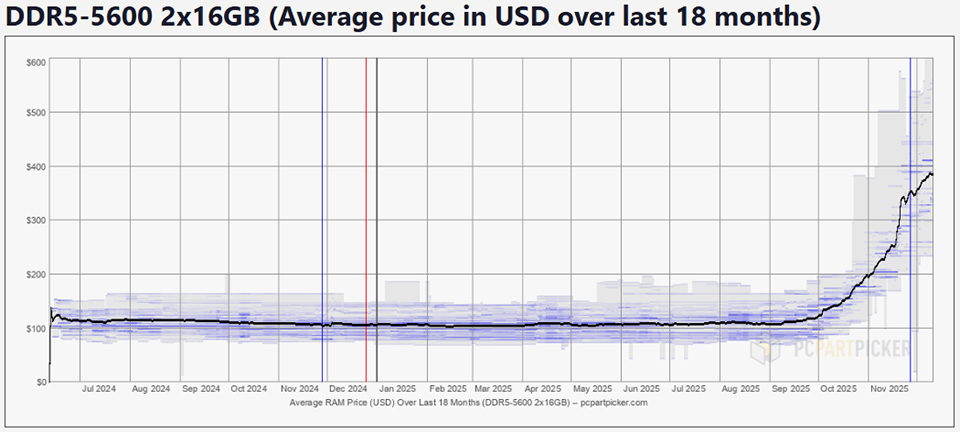

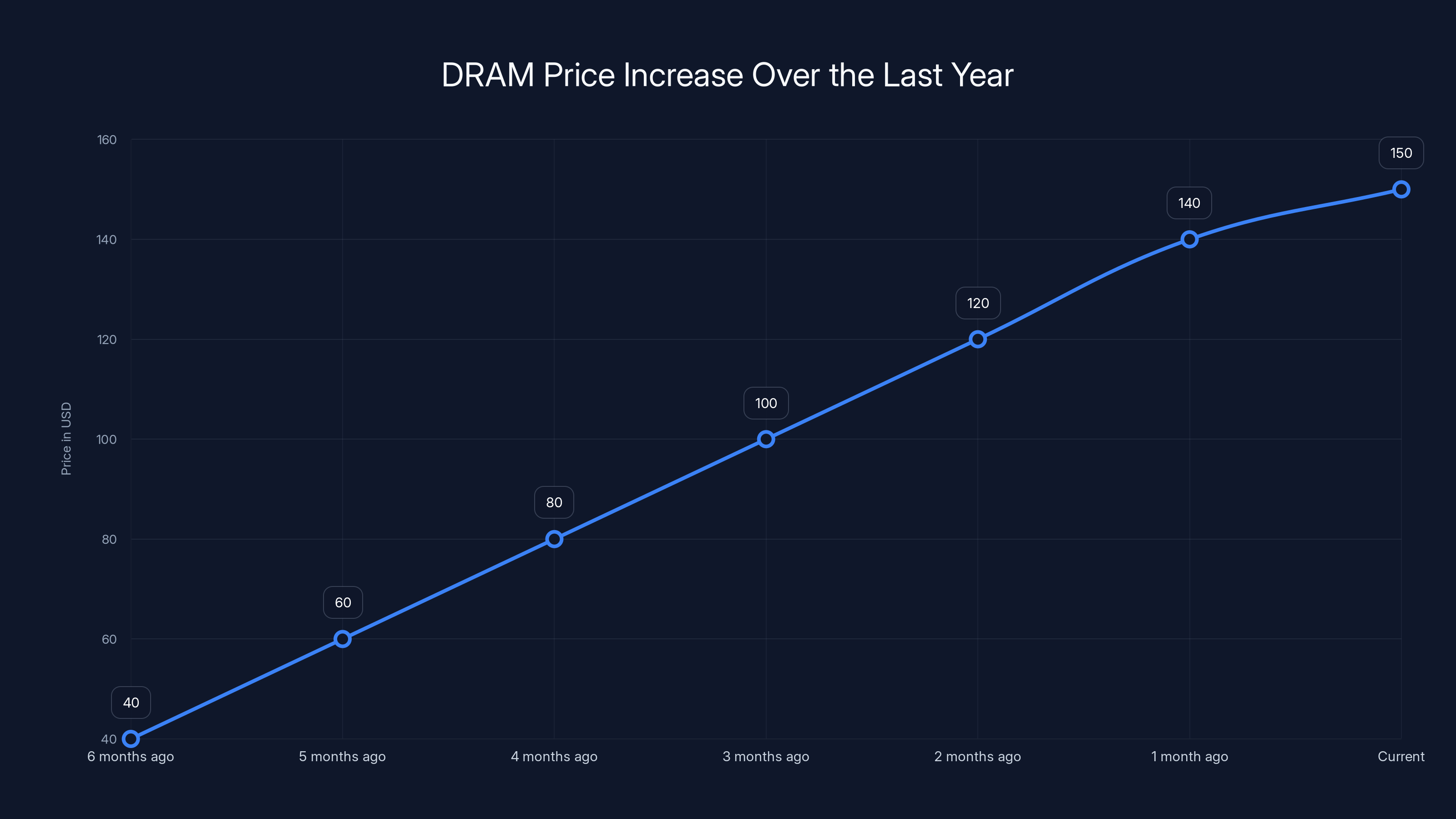

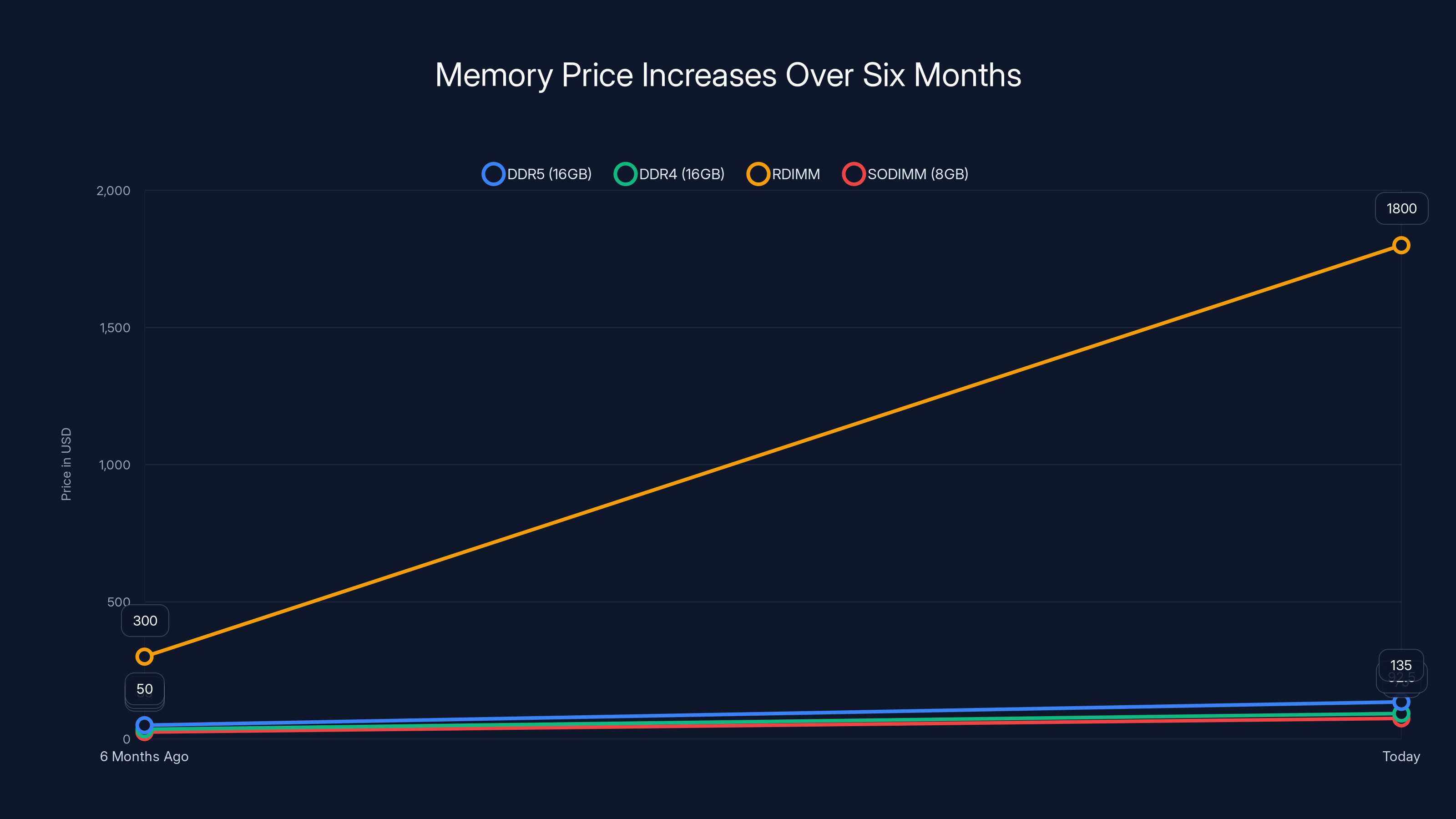

Memory prices have done something extraordinary over the past six months. DRAM prices have tripled, quadrupled, and in some cases even sextupled. We're talking about price increases that dwarf typical market volatility. A stick of DDR5 RAM that cost

The immediate cause is clear: artificial intelligence. Data centers building out massive GPU clusters to train large language models and run inference engines have become voracious consumers of memory. A single high-end AI training rig can consume gigabytes of RAM. When you multiply that across thousands of data center installations worldwide, suddenly you're talking about allocation shortages that ripple through the entire supply chain.

What makes this crisis unique is that it's not temporary. The AI infrastructure buildout will continue for years. Open AI, Anthropic, Google Deep Mind, and every other major AI lab will need more memory, not less. The data centers supporting Microsoft's AI infrastructure will keep expanding. This means the shortage isn't a one-time problem you wait out. It's a multiyear squeeze that will get worse before it improves.

Even companies that don't build AI models are affected. If you run any substantial cloud infrastructure, you're competing for the same limited memory pools. Your enterprise servers are stuck in traffic behind data center expansion projects that have unlimited budgets.

DRAM prices have surged due to AI-driven demand, with DDR5 RAM prices increasing from

The Three Companies Controlling Your Memory

To understand why this crisis is so severe, you need to understand market concentration. The DRAM market isn't competitive in any meaningful sense. It's an oligopoly, and it's the most concentrated oligopoly in the semiconductor industry.

SK Hynix, Samsung, and Micron Technology control 93 percent of global DRAM production. Let that number sink in. Ninety-three percent. That's not a duopoly. That's functional monopoly territory.

When demand spikes across the industry, there's nowhere else to turn. You can't switch suppliers. You can't source from new manufacturers. There are no alternatives. This gives the three dominant players absolute power over pricing and allocation.

What's worse is how these companies are responding to the shortage. You might expect them to rapidly expand production capacity to capture market share and cash in on high prices. That's what any rational, competitive market would do. Instead, all three are deliberately pumping the brakes.

Samsung recently announced it would slow down memory production even as prices soared. Micron has taken a similar cautious approach. SK Hynix is making measured increases rather than all-out capacity expansion. The reason is simple: they remember 2018.

In 2018, the industry overproduced memory chips in response to high prices. Manufacturers built too much capacity too fast, prices crashed, and the entire sector suffered billions in losses. Nobody made money. The companies learned that lesson hard. Now they're prioritizing profits over production volume.

This creates a perverse incentive structure. As long as shortage persists, prices stay high and margins remain fat. If production surges and shortage eases, prices collapse and margins evaporate. From a shareholder perspective, slower production at high prices beats rapid production at low prices. The math is brutal, but it's clear.

The result? The shortage will persist exactly as long as manufacturers believe they can control supply without triggering competitive pressure or regulatory scrutiny. And with only three players, coordination isn't hard. They don't need to collude. They all reach the same rational conclusion independently.

Why Data Centers Are Consuming Everything

The AI arms race has created an unprecedented demand for memory that dwarfs everything else. To understand the magnitude, you need to think about what happens inside a data center running modern AI workloads.

When Claude or Chat GPT responds to your query, it's not magic. Those queries are running on physical hardware that consumes staggering amounts of memory. A large language model with 70 billion parameters needs to fit in RAM. GPUs need memory to cache activations. Systems need memory for scheduling, batching, and handling concurrent requests. The aggregate memory footprint for even modest-scale AI infrastructure is measured in petabytes.

Compare this to consumer needs. Your laptop has 16GB of RAM. Your gaming PC might have 32GB. Even a high-end workstation rarely exceeds 256GB. Now imagine thousands of servers, each with terabytes of RAM, all operating continuously in data centers worldwide. The disparity is staggering.

And here's the key point: data centers get first dibs. When memory is scarce, cloud providers and AI infrastructure companies have the budgets to outbid everyone else. They'll pay whatever it takes because they have VC funding, venture debt, or deep corporate pockets. A startup might need to choose between buying RAM and making payroll. A data center just pays the premium and passes the cost to customers.

This creates a cascading effect. As data center demand consumes available supply, regular manufacturers and smaller companies get squeezed. They either accept massive price increases, reduce orders, or go without. For consumer electronics makers, this is a disaster.

Cloud service prices are projected to increase by 30-50% by 2025 due to capacity constraints and prioritization of AI services. (Estimated data)

The Phison Warning and What It Really Means

When Pua Khein-Seng made his remarks about potential company failures, he wasn't being hyperbolic. He was being precise about the implications of continued scarcity.

Phison makes controller chips, which are critical for SSDs and other flash memory devices. These aren't the DRAM chips that people think of when they hear "RAM." They're the controllers that manage how data gets written and read from flash storage. But here's the thing: Phison's position in the supply chain gives them visibility into broader trends. When memory becomes scarce, everything gets scarce, because DRAM is required to run the systems that manufacture and manage everything else.

Khein-Seng's warning specifically mentioned that companies would face two problems in the second half of 2026. First, they might not have enough memory to sustain their product lines. Second, if they couldn't secure supply, they would be forced to choose which products to kill and which to keep.

For a diversified consumer electronics company, this is a nightmare scenario. Imagine being Apple or Samsung. You make phones, tablets, laptops, watches, and enterprise servers. Each product line has different memory requirements. When supply is constrained, you have to triage. Do you allocate memory to the high-margin iPhone Pro Max, or the lower-margin SE? Do you keep your tablet line alive, or focus entirely on phones?

For smaller manufacturers, the decision is even more brutal. A maker of specialty computing devices, industrial controllers, or embedded systems might not be able to compete for memory at all. Their entire business could become unviable if they can't secure the components they need at any price.

Khein-Seng was careful in his phrasing. The interviewer asked whether companies might shut down. Khein-Seng agreed and clarified that it would happen if companies couldn't secure RAM. That's a crucial distinction. He's not predicting arbitrary bankruptcies. He's saying that if the shortage persists and remains severe enough, companies will fail as a direct result of supply constraints.

Is this likely? It depends on how long the shortage lasts and how severe it becomes. But it's definitely possible. Companies operate with inventory buffers and supply chain resilience plans. Those buffers are finite. If shortage stretches across multiple quarters without relief, smaller players will exhaust their reserves.

Which Companies Are Most Vulnerable

Not all companies face equal risk. The RAM shortage will hit different sectors and different manufacturers with different severity levels.

Small to mid-sized hardware manufacturers are most exposed. If you make specialized industrial controls, embedded systems, robotics, IoT devices, or niche computing hardware, your margins are typically thinner than consumer electronics makers. You can't absorb 3x or 4x increases in memory costs. You can't negotiate favorable terms with DRAM suppliers. You're taking whatever allocation you can get at whatever price the market demands.

Consumer electronics makers with diversified product lines face forced choices. Dell, HP, and other PC makers will have to decide whether to shift resources toward gaming and professional laptops (higher margins) or budget systems (higher volume). Those budget product lines might simply disappear.

Laptop manufacturers specifically face brutal pressure. Lenovo, ASUS, and Acer all operate on thin margins in the consumer segment. They're already dealing with CPU shortages and GPU constraints. Adding severe memory scarcity could force consolidation of product lines.

Mobile phone makers have more flexibility but still face challenges. Apple has the resources to secure memory at any price. But mid-range phone manufacturers that compete on value will get priced out. This could accelerate the market consolidation we're already seeing, where the industry shrinks down to a handful of major players.

What's counterintuitive is that some of these companies might actually be more vulnerable in late 2026 than in early 2026. Early in the shortage, they have inventory. As months go on, they deplete reserves. By mid-to-late 2026, they're buying new production at peak prices with no buffer. That's when the business model breaks.

Memory prices have surged dramatically over the past six months, with RDIMM experiencing the most significant increase, sextupling in price. Estimated data.

Even Giant Companies Face Real Constraints

You might think that massive companies with enormous market power could simply outspend everyone else and secure all the memory they need. The reality is more complicated.

Even Apple, which has the largest cash reserves of any tech company, faces constraints. DRAM manufacturers can't simply produce unlimited memory. There are physical limits to factory capacity. Even if Apple negotiates an exclusive deal for a percentage of production, that percentage is still a fixed allocation. And DRAM manufacturers know Apple will pay whatever they ask, so they don't have incentive to expand capacity just for Apple.

Worse, Apple also needs memory for non-obvious products. People think about iPhone RAM and MacBook RAM. But Apple also needs memory for iPad, for Apple Watch, for Apple TV, for data center servers running iCloud, and for enterprise servers. Suddenly the allocation problem becomes complex even for giants.

Microsoft faces an even more acute squeeze. They need memory not just for consumer devices, but for the vast Azure cloud infrastructure. They need it for AI workloads. They need it for enterprise servers. They're competing against themselves for allocation.

Even Nvidia acknowledged the severity. The company said it might skip shipping gaming GPUs entirely in 2026 for the first time in 30 years. Why? Because without sufficient memory to run AI data centers, there's no revenue to justify the R&D and manufacturing for consumer gaming cards. Nvidia is openly stating that it will prioritize AI supply even if it means abandoning consumer markets.

This signals how serious the constraint has become. Nvidia doesn't need to abandon consumer products. It chooses to, because data center opportunities are that lucrative. When market leaders are voluntarily exiting consumer segments, you know the supply crisis is real.

The SSD and Flash Memory Implications

The RAM shortage isn't limited to DRAM. Flash memory for SSDs and other storage devices will also face pressure, though for somewhat different reasons.

Flash memory manufacturers face a resource allocation problem. They need to invest in new fabs (manufacturing facilities), but those fabs are expensive. A single state-of-the-art fab costs several billion dollars and takes years to build. Manufacturers have limited capital, so they have to choose where to invest.

Historically, they'd invest in whichever segment was most profitable. That's traditionally been high-capacity data center SSDs and enterprise storage. But AI's demand for memory is pulling resources in a different direction. Some manufacturers are shifting capex toward memory production rather than flash expansion.

This creates a secondary shortage in SSDs. Your laptop or desktop might not just face memory constraints. It might also struggle to get a large-capacity SSD. A 2TB SSD that cost

Phison's warning about controller shortages is relevant here. If you can't get the controller chips that manage SSDs, then you can't ship SSDs, regardless of whether the underlying NAND flash is available. A shortage cascades through multiple layers of the supply chain.

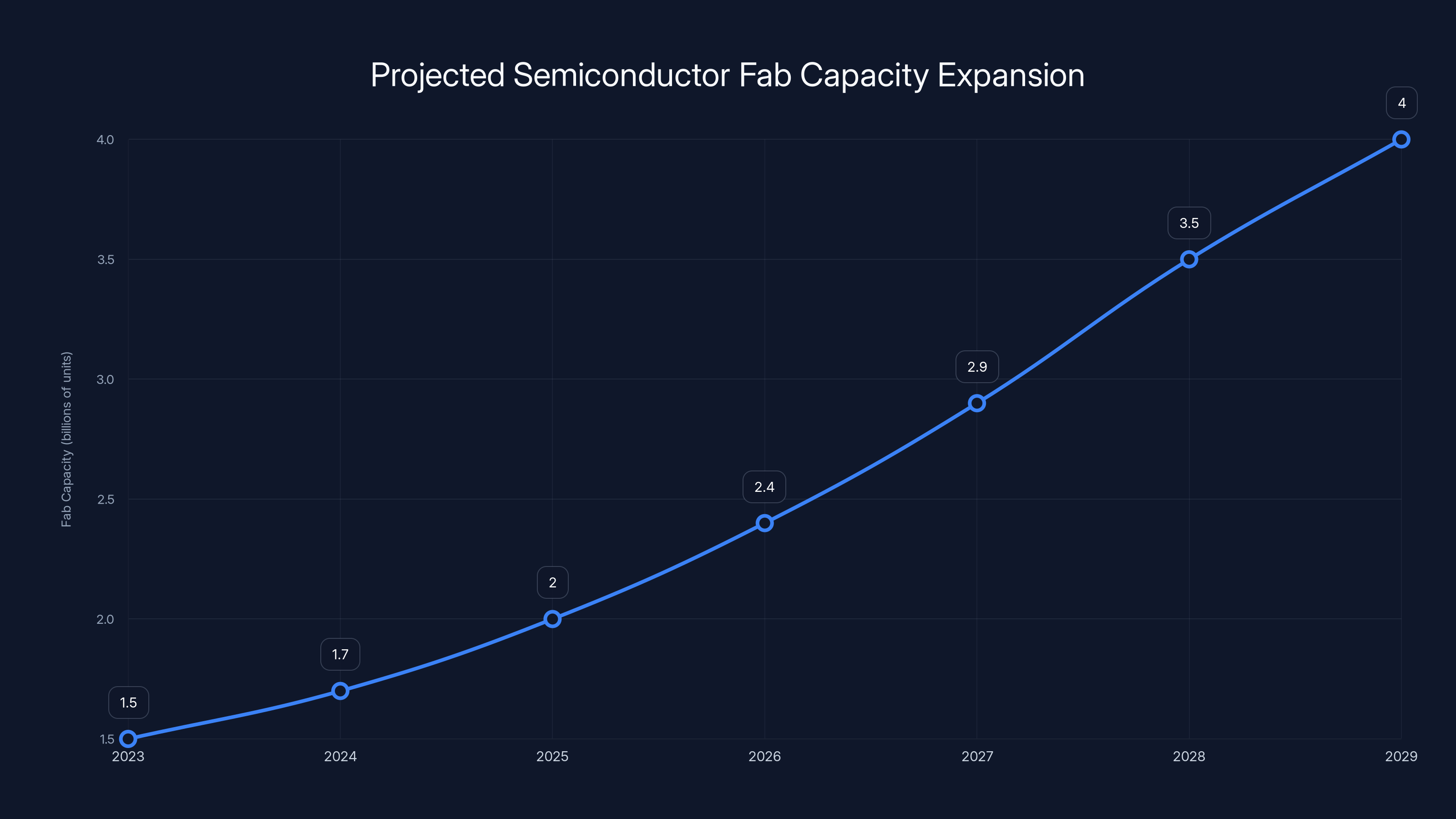

Estimated data shows gradual fab capacity expansion, with significant improvements expected by 2028-2029. Current slow growth is due to high capital costs and regulatory delays.

Pricing Reality Check: What's Actually Happening to Costs

The abstract discussion of shortage means nothing until you see real price movements. Let's ground this in actual market data.

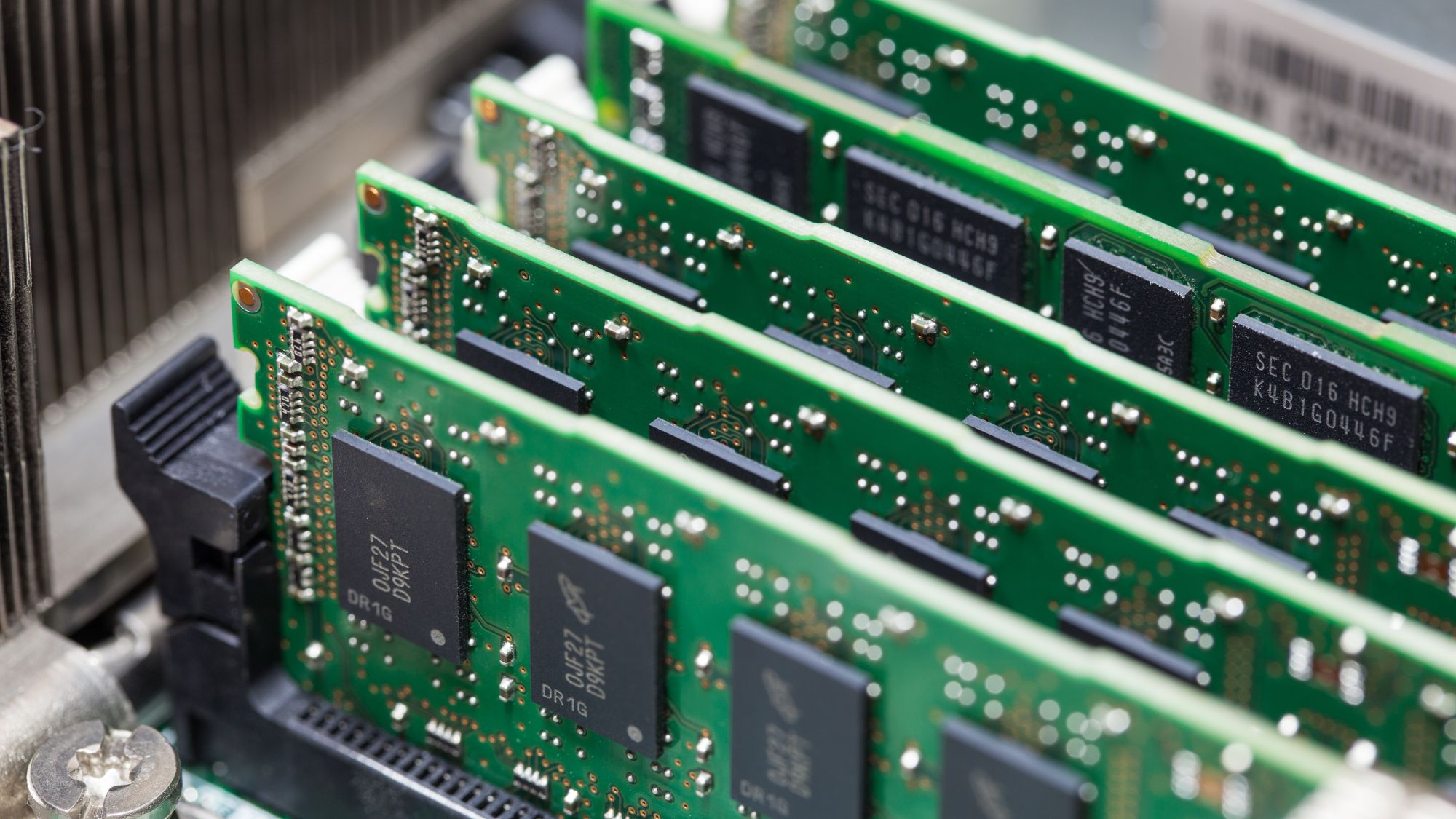

DDR5 memory, which powers modern PCs and servers, has seen the most dramatic price increases. Six months ago, you could buy 16GB of DDR5 for roughly

DDR4 memory (older but still widely used) has also spiked, though less dramatically. 16GB went from roughly

Server-grade memory has spiked even more. Registered DIMM (RDIMM) memory used in data centers has sextupled in some configurations. A memory module that cost

Laptop memory has tracked similarly. SODIMM (laptop-specific memory) has jumped from

These aren't marginal increases. These are transformational cost changes that completely alter the economics of hardware manufacturing. A gaming laptop that cost

What's crucial to understand is that these prices are sticky. Even when shortage eases, prices don't immediately return to previous levels. When semiconductor prices rise, they typically stay elevated for months or years before gradually declining. The manufacturers aren't motivated to crash prices. The market will accept higher prices until demand destruction forces adjustment.

This is why companies face such dire choices. They can't just wait out the shortage. They need to make margin-crushing decisions immediately while hoping conditions improve before they're forced to execute those decisions.

Why Manufacturers Won't Solve This Quickly

Here's the part that keeps industry observers up at night: the companies that could solve the shortage have no incentive to do so rapidly.

Build a new semiconductor fab and you're committing to

What if data center demand moderates? What if AI investment slows? What if regulatory intervention forces some kind of prioritization? Any of these scenarios would leave you with massive excess capacity that you can't profitably utilize.

Fab expansion also requires regulatory approval in many cases. Congress wants DRAM production in the US, but it's moving slowly on subsidies. Europe wants fabs but hasn't provided clear incentives. South Korea and Taiwan dominate production, but they're already at capacity.

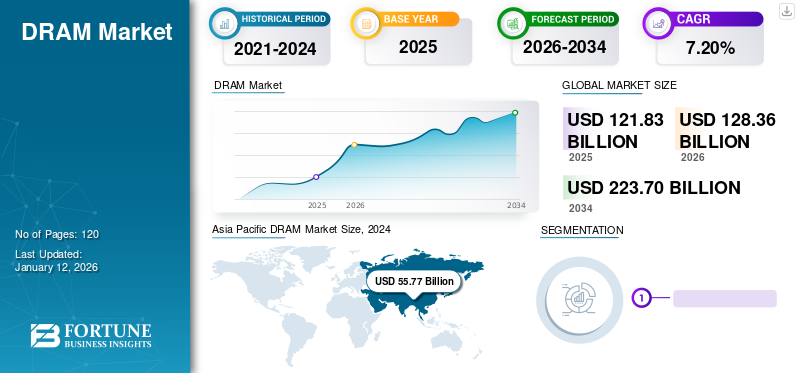

So manufacturers are taking the rational short-term path: expand modestly while capturing margin from shortage pricing. By 2028 or 2029, supply will improve as various capacity expansions come online. But that's years away. Until then, the shortage persists.

This is the essence of the crisis. It's not unsolvable. It's not permanent. It's just that nobody is motivated to solve it fast. Shortage benefits memory manufacturers. Shortage incentivizes data centers to negotiate long-term contracts at premium prices. Shortage eliminates competitive pressure on pricing.

From a game theory perspective, this is a classic prisoner's dilemma. The industry as a whole would benefit from rapid capacity expansion. Individual manufacturers are better off with constrained supply and high prices. So we get constrained supply and high prices, even though everyone knows it's suboptimal long-term.

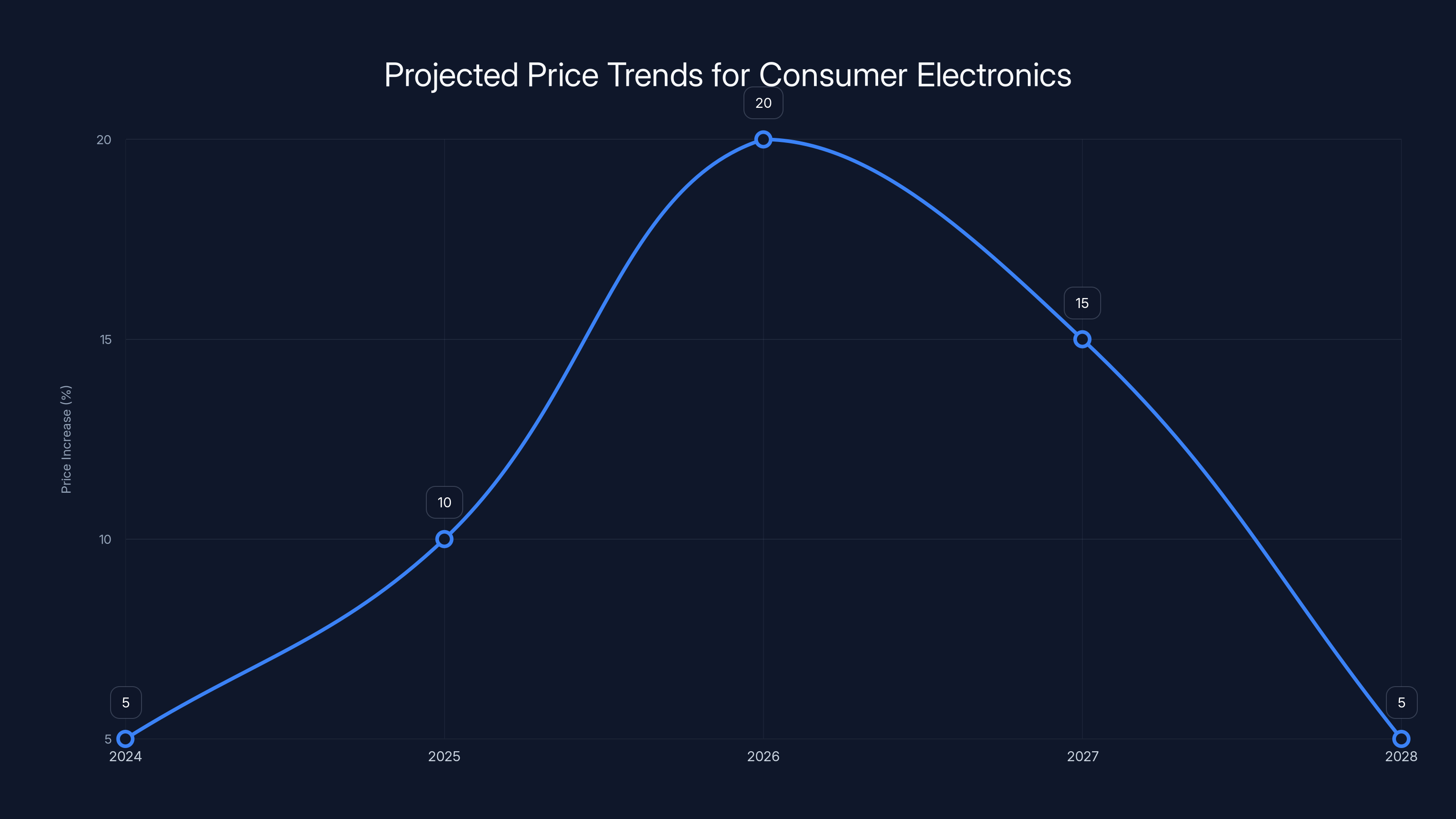

Estimated data shows a peak in consumer electronics prices around 2026 due to shortages, with prices stabilizing by 2028.

Second-Order Effects: Repair Culture and the Right to Repair

Khein-Seng made an interesting aside during his interview. He mentioned that he expects people will start fixing devices more often instead of discarding them. This seems like an oddly specific prediction, but it reveals something important about how shortage changes behavior.

When hardware is cheap and easy to replace, people throw things away. Your laptop's motherboard fails after three years? Buy a new laptop. Your phone stops holding a charge? Upgrade to a newer model. This replacement-focused culture is built on abundance.

When hardware becomes expensive and components are scarce, that calculus shifts. Suddenly it makes economic sense to repair things. You'll pay a technician to replace a motherboard if a new laptop costs 40% more than it did last year. You'll hunt for a battery replacement if phones are backordered for months.

This creates economic and environmental ripple effects. Repair shops might finally become viable as a business model. Parts supply chains for older devices might become valuable. Companies might have to invest in repairability design rather than disposability design.

Apple has been moving toward this under right-to-repair pressure, but mostly as a political concession. Shortage creates economic incentives to accelerate this shift. Suddenly Apple doesn't mind if you repair your phone, because you'll keep using an older model longer before upgrading.

This has environmental implications. E-waste decreases if devices get repaired instead of replaced. But it also has labor implications. More repair jobs, fewer manufacturing jobs. Economic opportunities in different places.

Khein-Seng's comment suggests he understands that shortage doesn't just affect supply chains and corporate profitability. It changes how billions of people interact with technology.

The Timeline: When Does This Actually Get Better

The shortage isn't permanent, but the timeline matters enormously for affected companies.

Short-term (next 6-12 months): Conditions will likely worsen before improving. Data centers will continue aggressive capacity building. Memory prices might stabilize at current elevated levels rather than spiking further, but they won't decline. Companies will begin making hard choices about product lines.

Medium-term (12-24 months): Some of the modest fab expansions that started in 2024-2025 will begin coming online. Production will increase incrementally. Prices might plateau or start declining slowly, but probably not dramatically. Companies will have made permanent changes to product portfolios based on scarcity decisions. Those decisions will stick even after shortage eases.

Long-term (24-36 months): Sufficient capacity should be online to substantially ease shortage. New fabs in the US, expanded capacity in South Korea and Taiwan, and increased efficiency should meet demand. But this assumes continued data center investment doesn't accelerate further.

The risk is that data center demand accelerates beyond expectations. If AI funding continues growing at current rates, shortage could persist longer. If memory demand from non-AI sources increases (quantum computing, edge AI, advanced robotics), shortage could deepen.

Conversely, if AI investment moderates or regulations limit data center growth, shortage could ease faster. But there's no indication of that happening.

The most likely scenario is that we're looking at a 2-3 year period of elevated prices and supply constraints. For some companies, that's survivable. For others, it's existential.

What Happens to Consumer Electronics

The consumer electronics market will undergo visible transformation as shortage unfolds.

Prices will rise. Expect to pay more for phones, laptops, tablets, and gaming systems. Not just because memory costs more, but because manufacturers will shift product mix toward higher-margin devices and away from budget segments. Your options will shrink.

Product lines will consolidate. The massive variety of laptop configurations you can currently choose from will shrink. Manufacturers will offer fewer SKUs (stock keeping units). You might find it hard to buy a laptop in your preferred spec combination because manufacturers are only producing the highest-margin configurations.

Feature differentiation will change. When memory is expensive, manufacturers might disable features to reduce per-unit memory requirements. A gaming laptop might have less onboard RAM by default. A smartphone might have less cache. These reductions happen silently, without obvious marketing announcements.

Timing to upgrade becomes critical. If you need a laptop or phone in 2026, you're buying at peak shortage pricing with reduced selection. If you can upgrade in 2024 or early 2025, you'll pay less and have more options. If you can wait until 2027 or 2028, prices will be lower and availability will be better. But few people can time their upgrades that precisely.

Refurbished and used markets might become more valuable. Older devices become scarce and expensive as people hold onto them longer. This creates economic incentive for device refurbishment and resale. You might get better value buying a used laptop than buying a new budget model.

Enterprise and Cloud Implications

Data center operators and cloud providers face a different set of challenges than consumer electronics makers.

Capacity constraints will force difficult prioritization. Cloud providers like AWS, Azure, and Google Cloud will have to choose which services to prioritize. AI services will get preference. Enterprise databases and traditional workloads will face resource rationing. This could translate to higher pricing or service degradation for non-AI customers.

Pricing power shifts. Enterprises that have historically negotiated favorable cloud pricing suddenly face a seller's market. Cloud providers might move customers to higher-cost service tiers to stay within memory budgets. Contracts that came up for renewal in 2025 might see 30-50% price increases.

Data center expansion slows. Companies planning new data centers or major upgrades might delay projects. This affects real estate, construction, and power infrastructure companies that depend on data center buildout.

Customers will face difficult choices. Should an enterprise negotiate a long-term contract with a cloud provider at today's premium rates, locking in high costs? Or should they wait for shortage to ease and risk being locked out of capacity? This is a genuine dilemma with no good answer.

Competitive dynamics shift. Cloud providers with existing capacity and strong DRAM relationships (like Microsoft with massive cash reserves) can weather shortage better than smaller competitors. Shortage could accelerate consolidation in cloud markets, with dominant players capturing share from struggling competitors.

The Geopolitical Dimension

Memory shortage also has implications for US-China relations and tech independence.

The US currently manufactures almost no DRAM. Micron is the only US company in the top three, and most of its advanced production is in Japan, not the US. This creates dependency on South Korea and Taiwan.

Policymakers have noticed. The CHIPS Act allocated funding for US memory manufacturing, but results have been slow. It takes years to build fabs and achieve competitive production. In the meantime, shortage highlights the vulnerability of depending entirely on foreign suppliers for critical components.

China is also watching. The country has aggressive plans to develop domestic DRAM manufacturing, though it lags Western capabilities. Shortage might actually accelerate China's efforts by demonstrating the strategic importance of memory independence.

The result could be a more fragmented global memory market, with different regions maintaining higher domestic buffer stocks and some degree of isolation from global supply shocks. This is economically inefficient but strategically appealing to policymakers worried about semiconductor independence.

Potential Government Responses

Governments might intervene to mitigate shortage impact, though previous experience suggests intervention is slow and ineffective.

Investment subsidies could accelerate fab construction. More aggressive CHIPS Act funding might bring forward timelines for new US plants. But this is a slow process. Any new US fab won't meaningfully contribute to supply until 2027 or later.

Prioritization schemes could be implemented. Government could designate certain sectors (healthcare, defense, critical infrastructure) for preferential memory allocation. This would ease shortage for those sectors while worsening it for consumer electronics and non-essential computing. The political fights over who gets preferred access would be brutal.

Tariffs or export controls might be used. The US could restrict DRAM exports to certain countries, or could negotiate bilateral agreements with South Korea and Taiwan to prioritize US company supply. The White House could exert pressure on manufacturers to prioritize US companies. This might help US-headquartered companies but would violate free trade principles and would likely trigger retaliation.

Price controls are theoretically possible but would likely backfire. Imposing price caps on memory would reduce manufacturer incentive to expand production and might accelerate shortage. Most economists view price controls as destructive during shortage, though some politicians might still propose them.

Most likely, government response will be slow and inadequate. By the time bureaucratic processes produce interventions, market conditions will have already shifted. History suggests that shortage resolves through market mechanisms (margin pressure forcing expansion) rather than through government action.

Broader Implications for the Tech Industry

Memory shortage will have lasting effects beyond the immediate 2-3 year crisis period.

Vertical integration might accelerate. Companies that depend on memory will consider whether they can bring memory production in-house or form long-term partnerships with suppliers. Samsung and SK Hynix profit from shortage, but customers will remember this and might seek alternatives or develop internal capabilities.

Software optimization becomes critical. If memory is expensive and constrained, software engineers will be incentivized to write more efficient code. Large language models might be compressed or optimized for lower memory footprints. Operating systems might shed bloat. This could lead to a useful reset where efficiency matters again.

Computer architecture might shift. Hardware designs optimizing for memory efficiency (smaller memory footprints, better caching, heterogeneous architectures) might gain favor over designs assuming unlimited memory. This could accelerate adoption of specialized processors and AI accelerators that reduce memory requirements.

Diversification of supply becomes a strategic priority. Apple, Microsoft, and other major companies will likely negotiate agreements with all three memory suppliers rather than concentrating with single vendors. This increases costs but reduces risk.

Long-term contracts become standard. Rather than spot market purchases, we might see more of the market shift toward multi-year contracts at fixed prices. This would provide supply certainty but would eliminate upside potential if shortage eases.

The Honest Assessment: This Is Serious

It's easy to dismiss tech industry warnings as hyperbole. The industry has a track record of overstating crises. But the memory shortage is different. It's structural, it's being deliberately maintained, and it has clear implications that ripple through every part of computing.

Khein-Seng's warning that companies could go bankrupt isn't designed to cause panic. It's an acknowledgment that continued shortage at current severity would force real economic consequences. Some companies will fail. Some product lines will be killed. Some markets will consolidate. These aren't theoretical possibilities. They're probable outcomes if shortage persists.

The good news is that shortage is temporary. By 2027 or 2028, supply should adequately meet demand. Prices will normalize. Selection will improve. This isn't a permanent state of scarcity.

The bad news is that the next 2-3 years matter enormously. Companies making decisions now about product lines or capacity will live with those decisions for years. Customers buying devices in 2026 will pay premium prices and have reduced choices. The disruption is real even if it's ultimately temporary.

What matters most is understanding that this isn't random market dysfunction. It's a predictable consequence of concentrated supply meeting explosive demand, with manufacturers rationally choosing to maintain scarcity rather than expand rapidly. Understanding that causality helps you see through the hype and make informed decisions.

FAQ

What exactly is causing the RAM shortage?

The primary driver is artificial intelligence. Data centers building out massive AI infrastructure are consuming the vast majority of global DRAM supply. Open AI, Anthropic, and other AI companies, along with Microsoft, Google, and Amazon's cloud divisions, have practically unlimited budgets to outbid other customers for available memory supply.

Why don't memory manufacturers just produce more RAM?

Manufacturers are deliberately limiting expansion because they learned a painful lesson in 2018 when overproduction crashed prices industry-wide. Samsung, SK Hynix, and Micron control 93% of the market, so they can rationally choose constrained supply to maintain high prices and margins. Building a new semiconductor fab costs $5-10 billion and takes 3-4 years, making rapid expansion a risky bet.

How long will the RAM shortage last?

Most industry analysts expect the acute phase to last through 2026, with gradual improvement in 2027 as new fab capacity comes online. However, this assumes AI spending continues at current trajectory. If data center investment accelerates further, shortage could extend longer. If AI investment moderates, shortage could ease faster.

Which companies are most at risk of bankruptcy or product line cuts?

Small to mid-sized hardware manufacturers with thin margins face the highest risk. Laptop makers like Lenovo, ASUS, and budget-focused brands are vulnerable. Large companies like Apple and Samsung can absorb higher costs but will likely eliminate lower-margin product lines.

Will RAM prices stay high even after shortage ends?

Historically, semiconductor prices stay elevated well after shortage eases. Manufacturers won't rapidly crash prices. Expect a gradual decline rather than a return to pre-shortage levels. Prices might normalize to 30-50% above early 2024 levels, but probably not to the exact previous baseline.

How will this affect people buying computers in 2026?

You'll face higher prices, fewer configuration options, and potentially lower memory allocations on base models. Laptop prices might increase 15-25%. Gaming system prices could jump even more. Storage capacity might be reduced on lower-end devices. Selection of budget models will shrink as manufacturers focus on higher-margin products.

Should I buy a new computer now or wait?

It depends on your actual need. If you need a computer now, buy now. If you can genuinely wait until 2027-2028, prices will be better. If you're in the grey area, you're making a bet on how aggressively shortage worsens through 2026. Early 2025 is probably better timing than late 2026.

What's Phison and why does their CEO matter?

Phison manufactures controller chips that manage data on SSDs and flash storage devices. CEO Pua Khein-Seng sits at the intersection of memory supply chains and sees real-time market conditions. His warning carries weight because his company is directly observing the supply constraints affecting the industry.

Could government intervention solve this?

Unlikely in the near term. The US CHIPS Act is providing funding for new fab construction, but new fabs won't contribute meaningfully to supply until 2027 or later. By that point, market forces will have already resolved much of the shortage. Aggressive government intervention (tariffs, export controls, price controls) could backfire or trigger retaliation.

What should businesses do to prepare?

Accelerate hardware refresh timelines if possible. Lock in long-term supply agreements with memory manufacturers if negotiating power allows. Optimize software for lower memory efficiency. Develop relationships with multiple suppliers. Build inventory buffers ahead of peak shortage periods. Plan product line decisions now rather than later when shortage forces reactive choices.

Closing Thoughts: Navigating the Crisis

The RAM shortage is real, serious, and will reshape consumer electronics markets over the next 2-3 years. It's not hypothetical. It's not hype. It's a direct consequence of supply concentration, demand imbalance, and rational behavior from manufacturers choosing constrained supply over rapid expansion.

For most people, this manifests as higher prices and fewer options when buying computers. For companies, it's far more existential. Some will make strategic bets on product line consolidation. Some will try and fail to secure sufficient supply. A few unlucky ones will fail entirely.

The warning from Phison's CEO serves as a reality check. This isn't something the industry expects to magically resolve. It's something everyone's actively planning around. Companies are already making decisions about which products to kill and which to keep. Manufacturers are already shifting production toward higher-margin segments. Supply chains are already tightening.

The good news is that this is temporary. Shortage will ease as new fab capacity comes online. Prices will decline. Selection will improve. By 2028, this will be a historical lesson in supply chain dynamics rather than an acute crisis.

Until then, the memory shortage will be the defining constraint on computing hardware. Understand it, plan around it, and make informed decisions about your own hardware purchases and business strategies. The companies that navigate this period successfully will be the ones that understood the underlying dynamics and made decisions accordingly.

Key Takeaways

- Phison CEO warns companies may need to eliminate entire product lines in H2 2026 if RAM shortage persists, with some facing potential bankruptcy

- AI data centers are consuming the vast majority of global DRAM supply, creating unprecedented scarcity for consumer electronics and enterprise computing

- Three companies (SK Hynix, Samsung, Micron) control 93% of DRAM production and are deliberately limiting expansion to maintain high prices

- DDR5 memory prices have tripled to quadrupled in six months, while server-grade memory has sextupled, fundamentally altering hardware manufacturing economics

- Shortage will likely persist through 2026 with gradual improvement in 2027-2028 as new fab capacity comes online, but manufacturers are rationally choosing constrained supply over rapid expansion

- Effects will ripple through consumer electronics (higher laptop/phone prices, reduced selection), enterprise (higher cloud costs, capacity constraints), and repair culture (increased device repair vs. replacement)

Related Articles

- Steam Deck Out of Stock 2026: What RAMaggedon Means [2025]

- Valve's Steam Machine & Frame Delayed by RAM Shortage [2026]

- Mac Mini Shortages Explained: Why AI Demand is Reshaping Apple's Supply [2025]

- Steam Deck Out of Stock: RAM Shortage Impact [2025]

- PS6 Delayed to 2029, Switch 2 Price Hike: RAM Shortage Impact [2025]

- Steam Deck Stock Crisis: Memory & Storage Shortage Impact [2025]

![RAM Shortage Crisis 2026: How Memory Scarcity Could Bankrupt Companies [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/ram-shortage-crisis-2026-how-memory-scarcity-could-bankrupt-/image-1-1771463171758.jpg)