The Super Bowl Ad That Started a Privacy Crisis

Ring released what seemed like an innocent, heartwarming Super Bowl commercial. Cute dogs. Reunited families. The kind of feel-good storytelling that makes people cry into their chicken wings during the big game.

Except not everyone was crying tears of joy.

Instead, security experts, privacy advocates, and regular people started asking uncomfortable questions. The ad showed Ring cameras operating seamlessly across multiple homes, tracking packages, identifying people, and building what looked like a comprehensive surveillance network. What Amazon marketed as "community safety" looked to critics like the infrastructure for mass surveillance.

This wasn't just abstract concern. It was specific anxiety about a world where every doorstep, driveway, and front porch becomes a monitoring station. Where facial recognition quietly catalogs your neighbors. Where deleted footage might not actually be deleted.

The backlash reveals something deeper about how we feel regarding technology companies, privacy, and the trade-offs we're making without fully realizing it.

Understanding Ring's Business Model and Why It Matters

Amazon's Ring isn't just a doorbell company anymore. What started as a simple home security device has evolved into something far more ambitious: a distributed surveillance infrastructure that covers neighborhoods, cities, and eventually entire regions.

Ring's core business model relies on several interconnected pieces. First, you buy a Ring device (doorbell, spotlight camera, or indoor cam). Then Ring collects video footage from your camera. It stores that footage (for a fee, or for free with limitations). It offers subscription services for extended storage and features. And critically, it encourages users to share footage with each other and with law enforcement.

This sharing element is where things get interesting. Ring has been aggressively courting police departments. Over 2,500 police agencies across the United States now have direct access to Ring's Neighbors app, allowing them to request footage from specific areas without warrants or subpoenas in many cases.

The company frames this as community safety. Ring published data suggesting that neighborhoods with Ring cameras experience reduced crime. Whether that's true or whether it's correlation masquerading as causation remains debated, but the narrative is powerful.

But here's what worries people. When you combine footage from thousands of Ring cameras, add facial recognition technology (which Ring has been developing), throw in AI analysis of behavior patterns, and give law enforcement direct access, you're not building a security system anymore. You're building mass surveillance infrastructure.

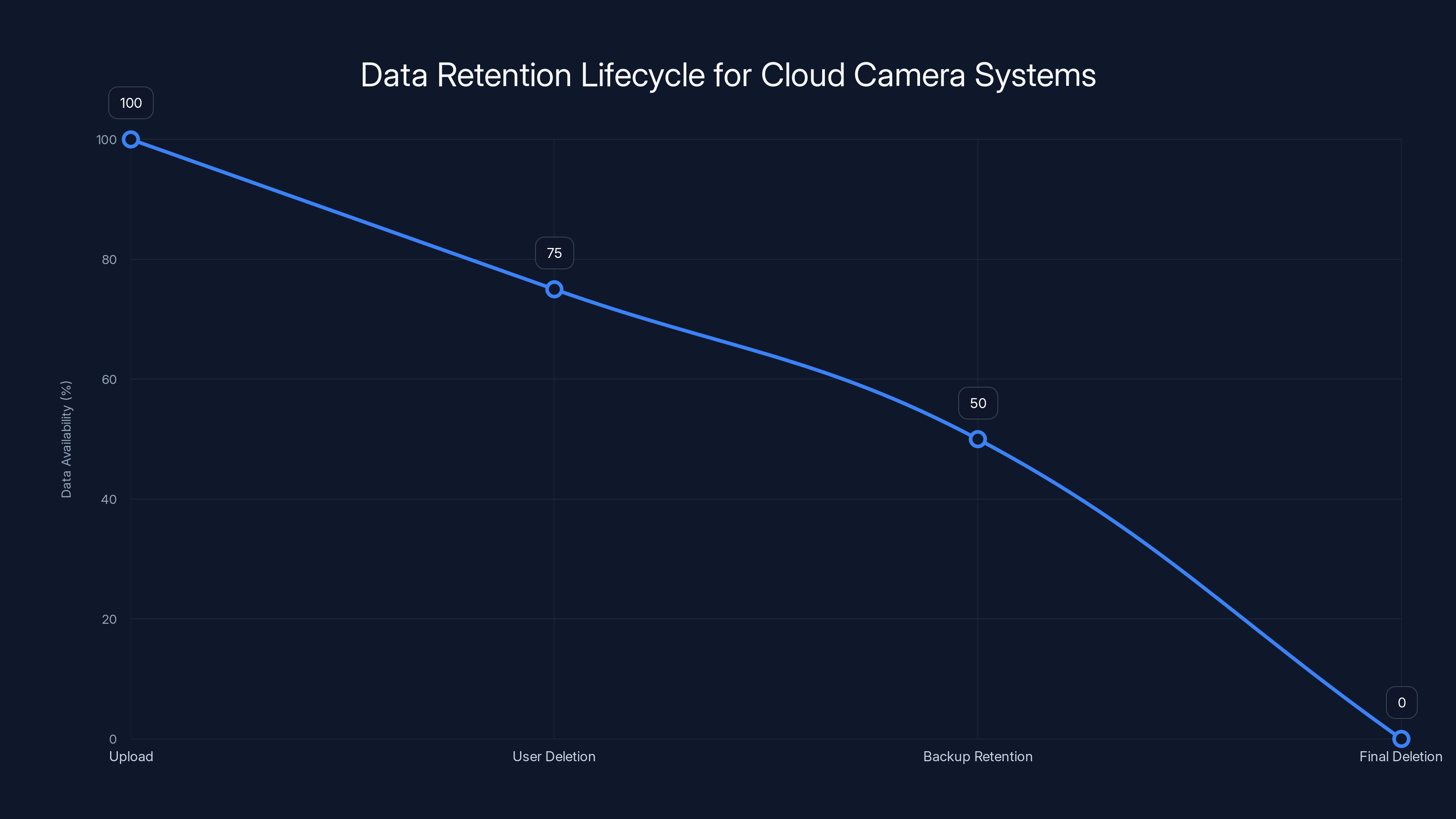

This timeline illustrates how cloud camera footage remains available even after user deletion due to backup retention policies. Estimated data based on typical cloud storage practices.

The Super Bowl Ad's Hidden Messages

The specific Ring Super Bowl commercial that triggered backlash showed something ostensibly innocent. Dogs getting reunited. A delivery person bringing packages. Families getting alerts when someone arrives home.

But privacy analysts and surveillance experts watched the same ad and saw something else entirely. They saw the scaffolding of mass surveillance being normalized through heartwarming storytelling.

In one scene, a Ring camera identifies a lost dog and alerts the owner. Cute. Heartwarming. But also: facial recognition of animals and objects working at scale across neighborhoods.

In another scene, a doorbell camera shows a delivery person arriving, and the footage is shared across the neighborhood network. Safe and convenient. But also: continuous recording of public spaces and the people moving through them.

In yet another scene, someone uses their Ring camera to talk to a delivery driver. Trust-building. But also: two-way audio surveillance normalized as casual interaction.

The genius of the ad (if genius is the right word) is that it's all true. Ring cameras do reunite lost pets with their owners. They do help people monitor deliveries. They do provide convenience and some legitimate security benefits.

But those legitimate benefits are inseparable from the surveillance infrastructure that enables them. You can't have the good without enabling the potentially bad. That's what made critics uncomfortable.

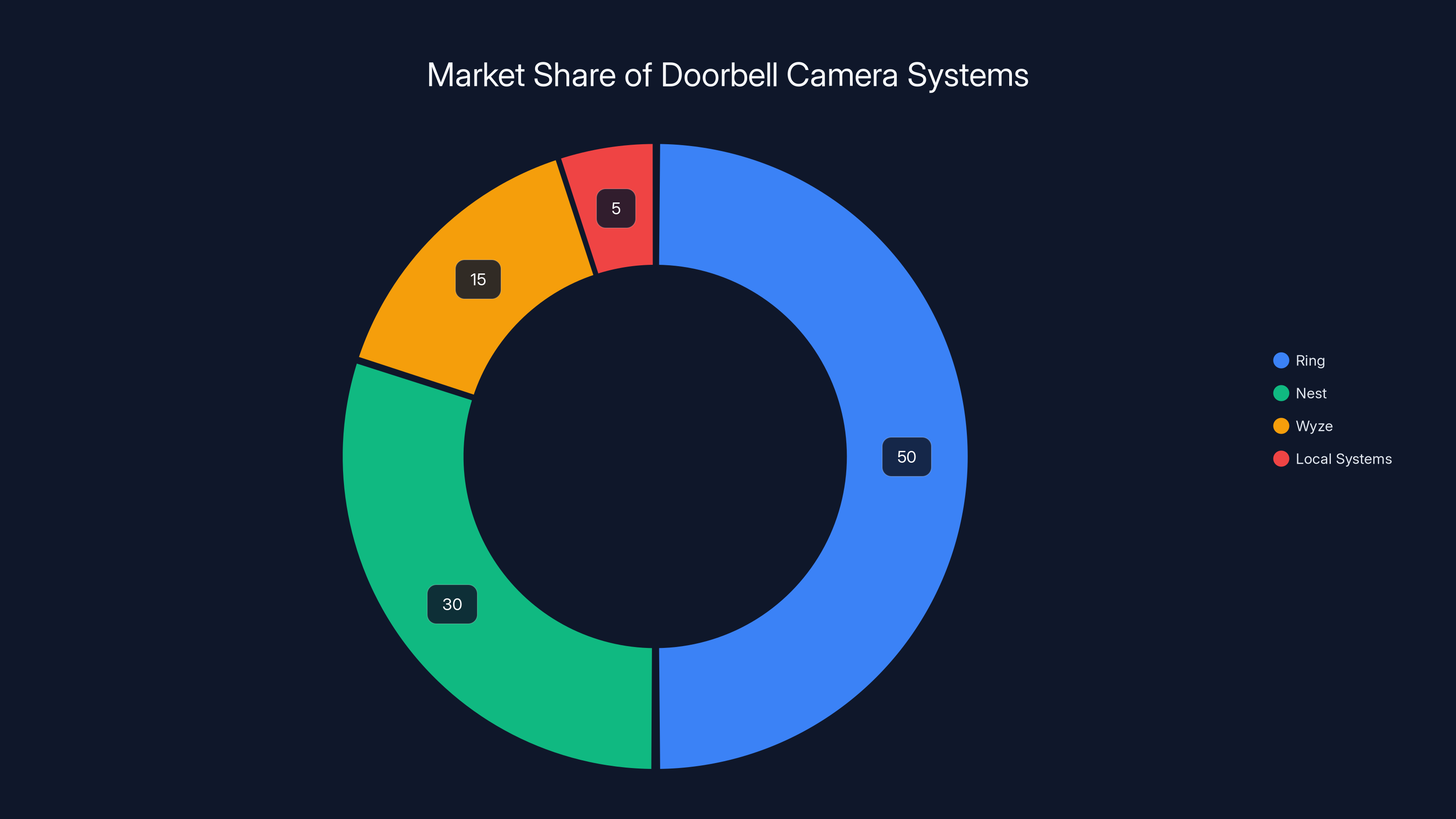

Ring holds an estimated 50% market share in doorbell cameras, with Nest as the closest competitor at 30%. Estimated data.

Privacy Concerns: What Critics Actually Worry About

The backlash wasn't just vague concern about "surveillance." People articulated specific, concrete worries.

The facial recognition escalation. Ring has been hiring computer vision engineers and researchers. The company is developing technology to recognize faces across cameras. Once that's deployed at scale (which may have already happened), law enforcement could potentially identify suspects just by running video through the system. No warrant required. No oversight.

Data retention and deletion. This is where the Nancy Guthrie case became important. Guthrie is a journalist who asked Google (which owns Nest, another Ring competitor) to delete her camera footage. Google said yes. But then, after a police investigation, Google recovered the footage anyway, claiming it had been archived for backup purposes.

The message: when you upload video to the cloud, you don't actually control whether it gets deleted. The company does. And the company can change its mind, especially if law enforcement asks nicely.

Scope creep and mission drift. Ring started as a doorbell. Now it's expanded to spotlight cameras, indoor cameras, and AI-powered threat detection. Where does it stop? Once the infrastructure is built, what prevents Amazon from expanding its capabilities? What prevents law enforcement from requesting footage for increasingly minor offenses?

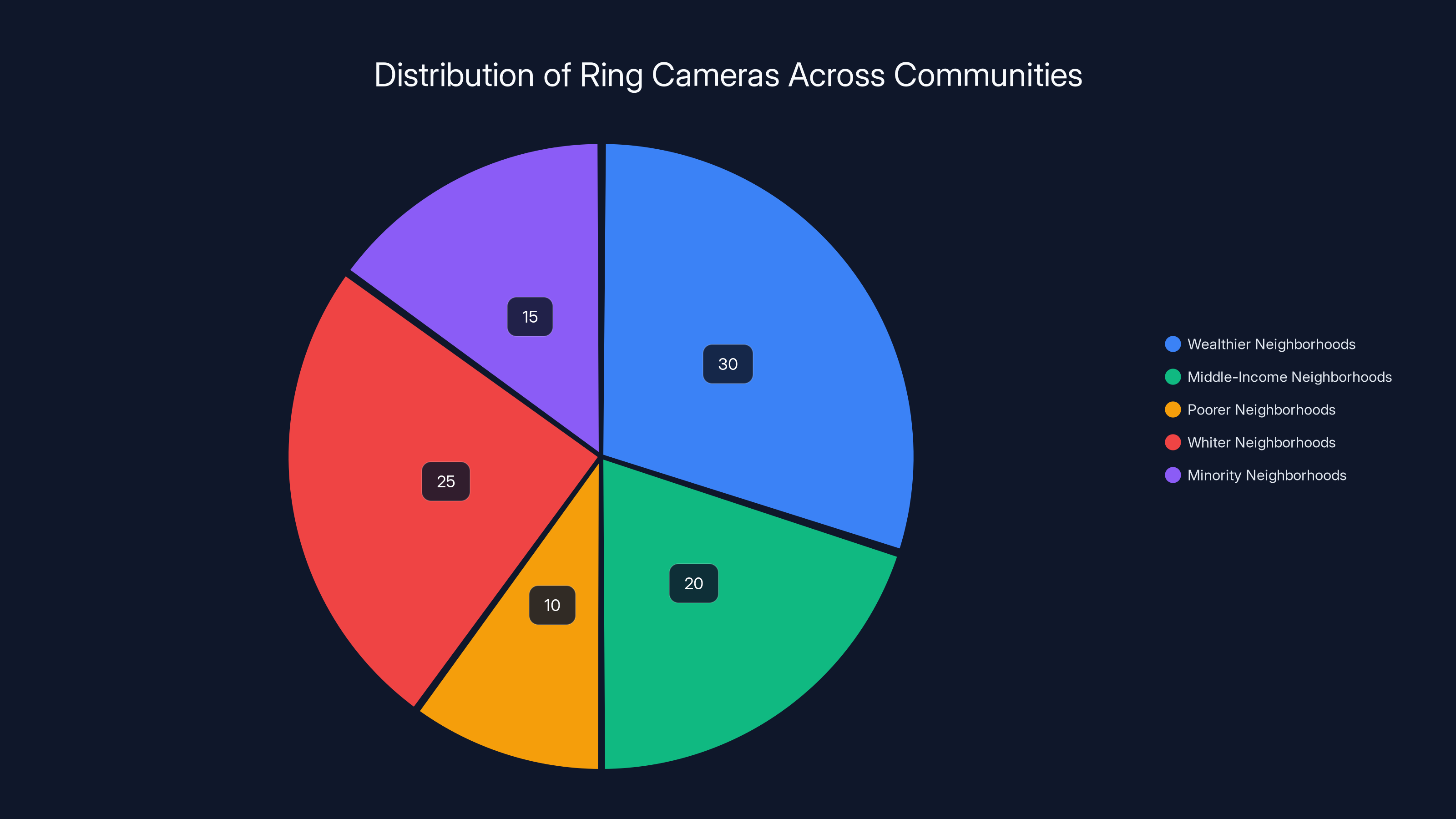

Disparate impact and bias. Surveillance systems aren't neutral. They tend to focus on poor and minority neighborhoods. If Ring is providing cameras more densely in some areas than others, and if law enforcement uses it to target communities, the result is structural inequality encoded in surveillance infrastructure.

The normalization problem. The most dangerous aspect of the Super Bowl ad wasn't that it was deceptive. It was that it was successful at normalizing comprehensive surveillance. After seeing the ad, people think "oh, this is just how things work now." They don't think about implications. They don't consider trade-offs. Surveillance becomes background noise.

The Nest Footage Case and Cloud Storage Reality

The Nancy Guthrie situation with Google Nest deserves deeper examination because it illustrates a critical problem most people don't understand about cloud-based surveillance systems.

Guthrie installed a Google Nest camera in her home. She then requested that her footage be deleted. Google complied. The footage was gone. Or so she thought.

Months later, Guthrie was interviewed by police about an incident in her building. The detective told her they had recovered footage from her Nest camera. Footage she had explicitly deleted. When Guthrie pressed Google on how this was possible, the company explained that deleted footage was archived for backup and recovery purposes. Google held onto it longer than it told users it would.

Now, Google maintained they followed their privacy policy. Technically, they probably did. The terms of service likely mentioned backup archiving in prose so dense that almost nobody reads it. But the key issue remains: users believed they had deleted their data. They hadn't. The company had.

This matters because it shows that the "privacy controls" companies claim to offer aren't as meaningful as they seem. You can delete a video. But the company decides how long to actually keep it. You can adjust privacy settings. But the company decides what those settings actually mean operationally.

For Ring and Nest users, this means that footage you think is gone might still exist in company backups. Law enforcement can request it. Companies can hand it over. And the person who recorded the footage might never know.

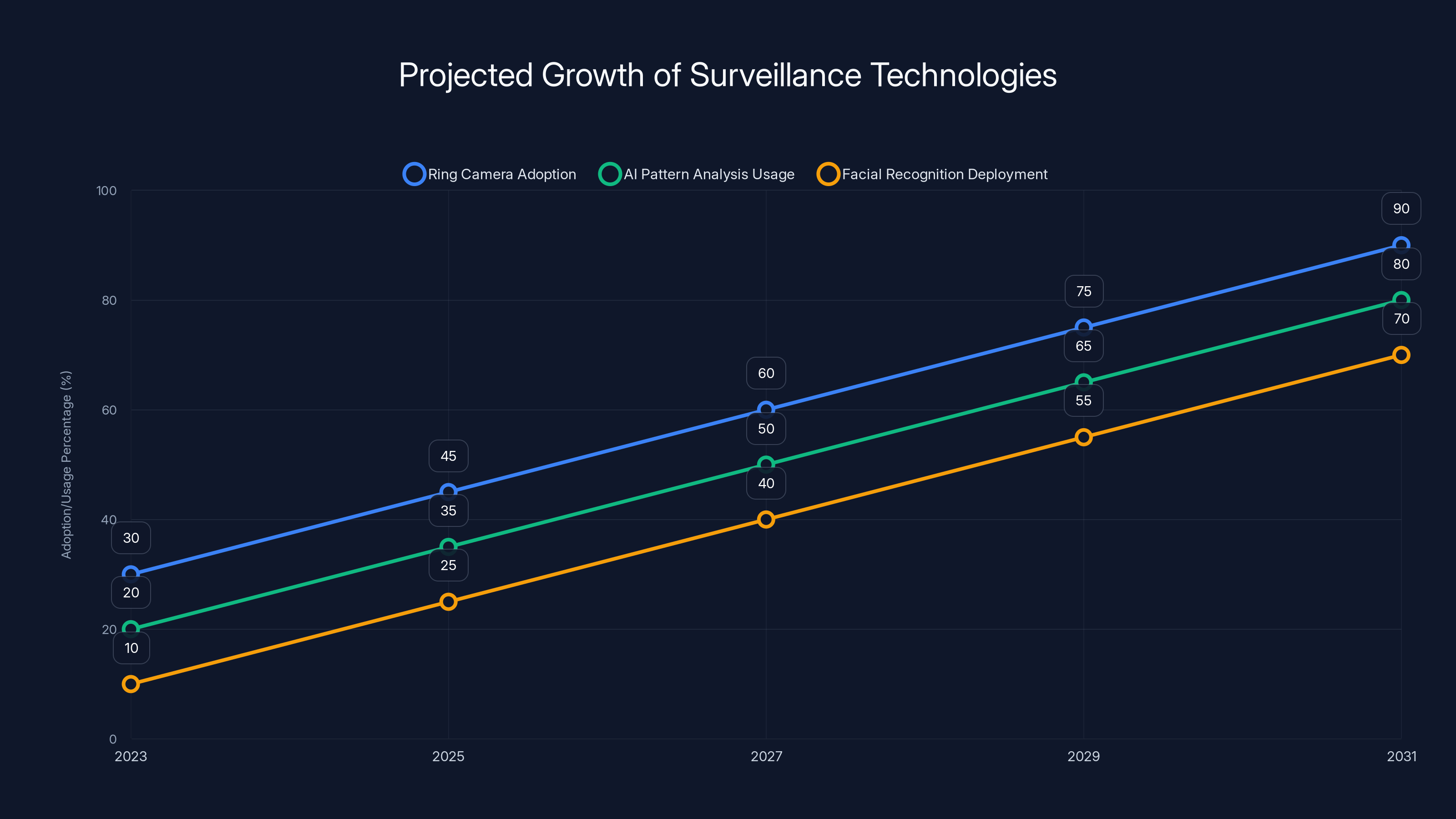

Estimated data shows significant growth in surveillance technologies, with Ring camera adoption potentially reaching 90% by 2031, driven by AI and facial recognition integration.

Law Enforcement Access and Warrant Requests

Ring has been extraordinarily cooperative with law enforcement. The company has given police direct access to its Neighbors app, allowing officers to request footage from specific areas.

This sounds efficient. Instead of a cop having to contact each homeowner individually, they can just submit a request through Ring, and the system notifies all relevant users. If those users agree to share footage, the cop gets it. Fast and easy.

But this system has problems that go beyond inconvenience.

First, it circumvents the warrant requirement. In the United States, police traditionally need a warrant to search someone's property or records. That requirement exists to prevent fishing expeditions and abuse of police power. But Ring's system allows police to bypass that by asking nicely through the app.

When a cop makes a request through Neighbors, they're not serving a warrant. They're asking a homeowner for consent. And lots of people consent. Maybe they believe in helping law enforcement. Maybe they don't understand the implications. Maybe they feel social pressure. But the end result is that law enforcement gets access to footage without judicial oversight.

Second, Ring's system normalizes mass footage requests. When a cop can request footage from a hundred homes simultaneously, instead of having to go through the tedious process of serving warrants on each one individually, the barrier to investigation drops dramatically. Investigations that might have been too resource-intensive to pursue become routine.

Third, there's no transparency. Ring doesn't publish clear data about how many law enforcement requests it receives, what those requests are for, or how often homeowners deny them. The company is opaque about this entire ecosystem.

Some police departments have been more aggressive than others. A few have used Ring's Neighbors requests to investigate minor offenses like package theft. Others have used it for serious crimes. But there's no systematic oversight or analysis of whether this tool is being used appropriately.

The AI Detection and Pattern Recognition Danger

Ring is investing heavily in AI. The company is working on systems that can identify threats automatically, recognize faces across cameras, and predict criminal behavior.

These technologies don't exist yet in mature form, but when they do, they'll enable surveillance at a scale that previous generations couldn't imagine.

Think about what's possible once you have facial recognition working across thousands of cameras in a city. A person's face becomes trackable wherever they go. Walk past a Ring camera to get coffee. Another Ring camera sees you at the store. Another at the bus stop. Within hours, you've created a comprehensive timeline of someone's movements.

Now add AI analysis. The system could predict where someone is likely to go next. It could flag people who match descriptions of suspects. It could categorize people by age, gender, or other characteristics.

The dystopian potential is real. But so is the incremental escalation risk. Ring doesn't need to jump straight to sci-fi surveillance. It can add features gradually. First, simple motion detection. Then, person detection (identifying that there's a human in the frame). Then, rough demographic information. Then, actual facial recognition. Each step seems reasonable in isolation. Collectively, they add up to mass surveillance.

And once the infrastructure is built, reversing it becomes nearly impossible. You can't uninvent facial recognition. You can't ask people to take down their Ring cameras. The network effects mean that once enough people have the devices, the surveillance coverage becomes comprehensive regardless of individual choices.

Ring cameras are more prevalent in wealthier and whiter neighborhoods, potentially leading to uneven surveillance and scrutiny. (Estimated data)

The Chilling Effect on Behavior and Communities

There's a psychological and social dimension to ubiquitous surveillance that goes beyond the technical concerns.

When people know they're being watched, they change their behavior. Psychologists call this the "panopticon effect," named after Jeremy Bentham's design for a prison where inmates never know when they're being observed, so they behave as if they're always being watched.

In neighborhoods saturated with Ring cameras, the panopticon effect starts kicking in. People become more cautious about their movements. Parents worry about letting kids play outside unsupervised if every moment is being recorded. Teenagers become self-conscious about hanging out on street corners. People thinking about leaving abusive relationships worry about being tracked.

This chilling effect isn't just about paranoia. It's about freedom. Free societies depend on the ability to move through public and semi-public spaces without constant surveillance. That freedom to be unwatched is part of what makes a community feel livable.

Ring cameras also change community dynamics in other ways. Instead of neighbors knowing each other and building trust through interaction, they watch each other through cameras. The Neighbors app becomes a tool for surveillance of your neighbors, not for community building. Conflicts that might have been resolved through conversation get escalated when someone sees a "suspicious" person and immediately reports them to the network.

There's also the question of who gets surveilled more intensely. Research shows that Ring cameras are distributed unevenly across communities. Wealthier neighborhoods have more cameras. Whiter neighborhoods have more cameras. This means that poor and minority communities might face less total surveillance, but they face more intense scrutiny from law enforcement using Ring cameras as a tool.

Amazon's Power and the Absence of Meaningful Alternatives

Part of what makes the Ring situation concerning is Amazon's dominant market position and the lack of meaningful alternatives.

Amazon owns Ring. Amazon also owns Alexa, AWS, and operates vast fulfillment networks. The company collects data about what you buy, how you move through your home, what you search for, and increasingly, what you say. Ring footage adds another data stream to that comprehensive profile.

When one company has this much data and this much power, it's nearly impossible to trust that data will be used responsibly. Companies change policies. New executives with different values take over. External pressure forces changes in behavior. And there's no guarantee that any given company will make decisions that respect privacy.

The alternative to Ring would be to use a different camera system. But what are the options? Google Nest, which has the same issues plus the added problem of being Google (which is in the advertising business and has even more incentive to monetize data). Wyze, which is cheaper but offers less integration. Local systems that don't upload to the cloud, which are harder to set up and don't work as seamlessly.

In reality, most people choosing a doorbell camera are choosing between Ring and Nest. And both companies have strong incentives to collect data, work with law enforcement, and gradually expand surveillance capabilities.

Without meaningful alternatives, without strong regulation, and without transparency, users have almost no meaningful choice in whether they participate in this surveillance infrastructure. They can choose not to install Ring. But then they live in a neighborhood where their house is the only one without surveillance, which creates a different set of problems.

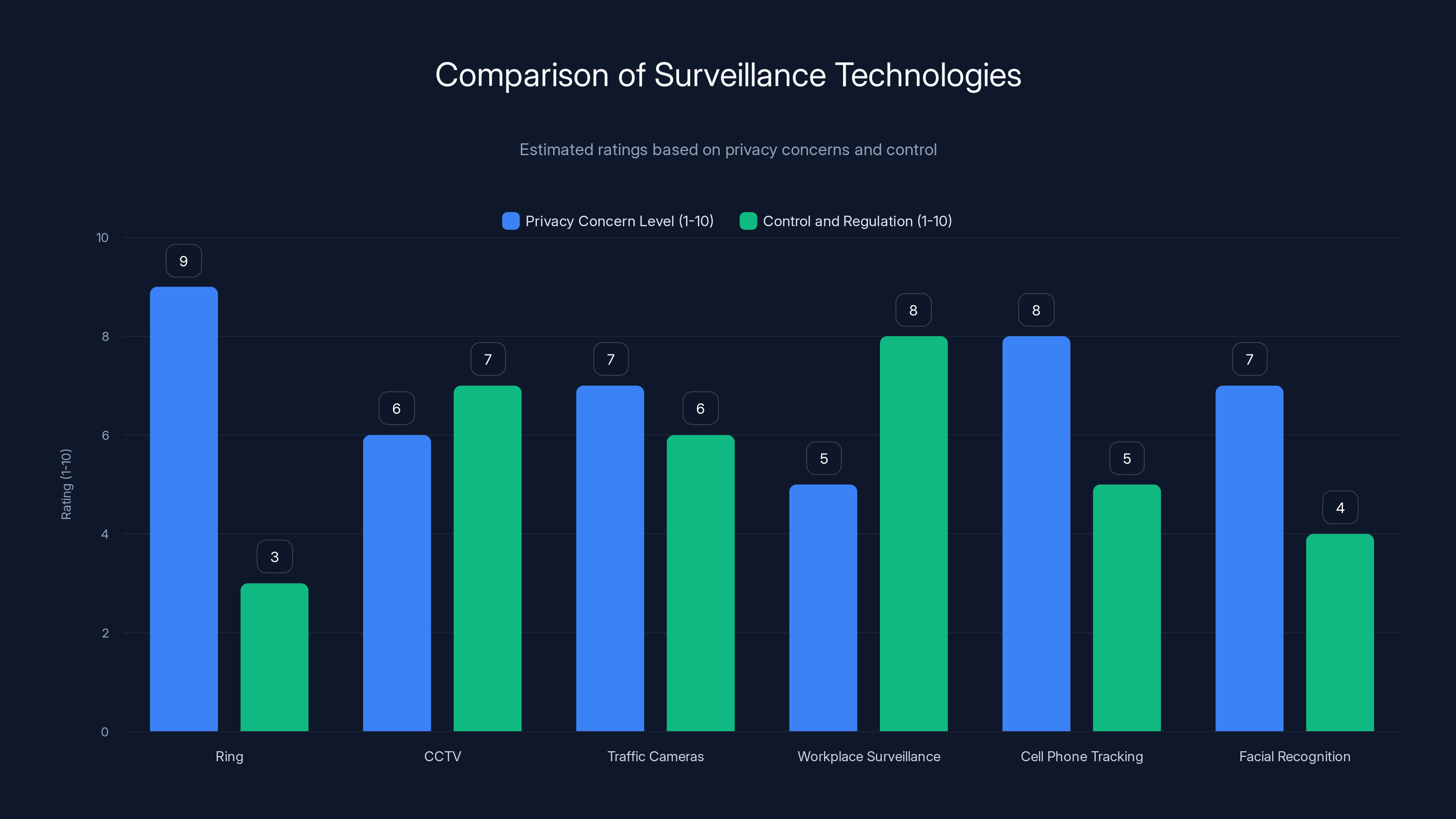

Ring scores high on privacy concerns due to its distributed nature and low on control due to lack of regulation. Estimated data based on privacy and control factors.

The Open AI Advertising Connection and Data Privacy Concerns

Interestingly, the Ring Super Bowl ad controversy emerged during the same week that another privacy concern hit the tech industry: Open AI began selling advertising in Chat GPT.

The timing matters because it reveals a pattern. As AI companies mature, they're transitioning from "we'll figure out the business model later" to "let's monetize everything, including the data you're generating." And they're doing it gradually, hoping people won't notice or won't care enough to leave.

With Chat GPT advertising, the concern is that your conversations with the AI are now product. Advertisers get to target you based on what you ask the AI. Your private conversations with an AI assistant become data points in an advertising database.

Ring operates on the same logic. Your home surveillance footage is product. It's valuable to law enforcement, to Amazon (for training AI systems), and potentially to advertisers (who want to know when you're home, when you're buying things, what your neighborhood looks like).

The companies will insist they're protecting privacy, following the law, and doing nothing wrong. And technically, they might be right. But the direction is clear: technology companies are extracting maximum value from every data stream they can capture.

This affects how you should think about Ring. It's not just a home security system. It's a data collection device that Amazon will monetize in ways you can't predict or control.

Regulatory Frameworks and What's Actually Being Done

So far, regulation of home surveillance and Ring specifically has been minimal.

In the United States, there's no federal law governing what Ring can do with footage. There's no requirement that Ring be transparent about police access. There's no mandate that Ring users be notified when law enforcement requests their footage.

Some states have moved faster. California passed legislation requiring Ring to remove data older than 60 days and to be more transparent about police requests. But California is an exception. Most states have done nothing.

International regulation has been slightly more aggressive. The European Union's GDPR gives users more rights to control their data and requires companies to minimize data collection. But Ring operates globally, and if Amazon decides something is compliant with GDPR, it applies that policy everywhere.

There have been some restrictions on facial recognition specifically. A few cities and states have banned police use of facial recognition entirely. But these bans are fragile, and they don't restrict Ring's ability to build the technology, only governments' ability to use it.

Advocacy organizations have called for stronger regulation. The Electronic Frontier Foundation, CNIL (France's data authority), and others have published detailed criticisms of Ring. But so far, those criticisms have mostly resulted in incremental improvements (like Ring's decision to store data for only 60 days in California).

The gap between what advocates want and what's actually happening is enormous. Advocates want Ring cameras to be banned entirely, or severely restricted. At minimum, they want warrant requirements for law enforcement access and transparency about how cameras are being used.

Instead, what's happening is minor policy tweaks while the Ring network expands. Ring now operates in most major U.S. cities. The infrastructure keeps growing. And regulation keeps lagging.

The Comparison: Ring vs. Other Surveillance Technologies

Ring isn't the first surveillance technology to raise privacy concerns. It won't be the last. But it's worth understanding how it compares to other systems.

CCTV and traditional cameras. These have been around for decades. But they're typically controlled by businesses or governments, not distributed across neighborhoods. And crucially, CCTV footage doesn't get uploaded to the cloud and indexed by AI. It's localized and time-limited.

Traffic cameras and license plate readers. Cities use these to monitor traffic and identify stolen vehicles. Concerns about mass surveillance are real. But most places have some legal framework governing their use. Ring operates in a legal vacuum.

Workplace surveillance. Companies monitor employees through cameras, keystroke logging, and other tools. Privacy advocates hate it. But there's at least a clear relationship: employer-employee. With Ring, the relationships are more complicated and less clear.

Cell phone tracking. Location data from phones is tracked by carriers, apps, and increasingly by law enforcement. This is possibly more intrusive than Ring because it's continuous and covers entire cities. But it's also abstract and invisible. Ring is more visible, which makes it easier to think about.

Facial recognition systems. Governments use these at borders, in cities, and increasingly by police. Most countries have minimal regulation. But most facial recognition systems are centralized, controlled by a single government or agency. Ring's network is distributed, makes it harder to regulate or oversight.

The unique danger of Ring is the combination: it's distributed, it's ubiquitous in many neighborhoods, it's controlled by a private company without clear oversight, and it's being equipped with increasingly sophisticated AI. No previous surveillance technology has quite this combination.

The Future: Where This Is Heading

If current trends continue, here's what the surveillance landscape might look like in five to ten years.

Ring cameras will be even more ubiquitous. Integration with Alexa will deepen. You won't just have video surveillance on your doorstep; you'll have voice recordings inside your home, both feeding into Amazon's systems. The data will be comprehensive.

Facial recognition will be deployed, either by Ring directly or by law enforcement using Ring footage. Faces will be identifiable. Movements will be trackable.

AI systems will do pattern analysis. They'll predict crime before it happens (with all the bias and inaccuracy that implies). They'll flag people as suspicious based on behavior that seems abnormal.

Law enforcement will use these systems extensively. What's now a request through the Neighbors app will become a standard part of police investigations. Asking for Ring footage won't seem like a violation of privacy; it'll seem like common sense.

And the privacy-conscious minority who don't use Ring will become increasingly conspicuous. Absence from the surveillance network will raise suspicion rather than providing privacy.

This future isn't inevitable. But it's where we're heading if nothing changes. And the Super Bowl ad, with its depiction of seamless, neighborhood-wide surveillance normalized as helpful and wholesome, is part of the machinery that's pushing us there.

What You Can Actually Do About This

Feeling helpless is understandable. Ring is huge. Amazon is powerful. The surveillance infrastructure keeps expanding. What can an individual actually do?

Don't install Ring if you can avoid it. The most direct thing is to not participate. Use a different camera system (even if the alternatives aren't perfect). Or don't use a doorbell camera at all. Your doorstep probably doesn't need to be surveilled.

If you do use Ring, minimize what it collects. Don't enable every feature. Use the least intrusive settings. Don't share footage with neighbors if you can avoid it. Delete footage regularly.

Advocate for regulation. Contact your local representatives. Support organizations pushing for privacy rights. Vote for politicians who take surveillance seriously.

Educate people around you. Most people don't think deeply about Ring. They see a helpful tool for security. Talking to neighbors about privacy implications can shift thinking.

Support alternative technologies. If you're going to use smart home stuff, use the services from companies that have better privacy practices. It won't be perfect, but it matters at the margins.

Stay informed. Watch what Ring is doing. Notice when the company makes changes. Pay attention to policy shifts. Surveillance expands through incremental steps that are easy to miss if you're not paying attention.

None of these are perfect solutions. The problem is structural. But individual choices still matter. They create demand signals. They create social pressure. They create the political will that might eventually lead to meaningful regulation.

The Broader Message: What the Ring Backlash Reveals About Technology Culture

At the deepest level, the Ring Super Bowl ad backlash reveals something about how technology companies and society are out of sync on fundamental values.

Companies like Amazon see ubiquitous data collection as an obvious good. More data means better products. Better products mean happier customers. From their perspective, Ring is the natural evolution of home security. Why wouldn't you want comprehensive surveillance? It makes you safer!

But a significant portion of society sees something different. They see privacy as a good in itself. They see autonomy as valuable. They see the right to move through the world without being watched and recorded as fundamental to human dignity.

These aren't easily reconciled. Amazon isn't wrong that Ring provides real security benefits. And critics aren't wrong that it enables mass surveillance. Both things are true simultaneously. The question is whether the security benefits outweigh the surveillance costs.

Companies assume the answer is yes. People questioning the backlash assume no. That gap between how tech companies see the world and how some people see it is going to be the defining tension of the next decade.

Ring is just the most visible example. The same tensions appear with facial recognition, algorithmic decision-making, worker surveillance, and a hundred other technologies. Companies build systems that are profitable and efficient. The social cost comes later, and it's often not counted in balance sheets.

The Super Bowl ad worked brilliantly as marketing because it spoke directly to what Amazon values: convenience, safety, connectivity. It didn't address what critics value: autonomy, privacy, freedom from observation. And that gap is probably unbridgeable through advertising.

What might bridge it is regulation, competition, and cultural shift. But those are slow processes. In the meantime, Ring cameras keep spreading. And the infrastructure for mass surveillance keeps getting built, one heartwarming commercial at a time.

FAQ

What is Ring and what does it do?

Ring is a smart doorbell and camera system owned by Amazon that records video of your front entrance and other areas of your home. The system allows homeowners to view live footage remotely, receive alerts when motion is detected, talk to visitors through two-way audio, and share footage with neighbors and law enforcement through Ring's Neighbors app.

How does Ring's data collection work?

When you install a Ring camera, it records continuous or motion-triggered video that gets uploaded to Amazon's servers. Amazon stores this footage for a period you can configure, offers cloud storage options for extended retention, and can provide that footage to law enforcement upon request through the Neighbors app or other mechanisms. The company also collects metadata about when the camera is active, who accessed it, and what notifications were triggered.

What are the privacy risks associated with Ring?

The main privacy risks include potential facial recognition capabilities Amazon is developing, law enforcement access to footage without warrants, unclear data retention policies, the normalization of neighborhood-wide surveillance, and the fact that supposedly deleted footage may persist in Amazon's backup systems. Additionally, the distributed nature of Ring cameras across neighborhoods creates a comprehensive surveillance network that can track people's movements and behaviors.

Why did Ring's Super Bowl ad receive backlash?

The Super Bowl ad depicted a seamless, neighborhood-wide surveillance system where Ring cameras tracked lost dogs, monitored deliveries, and shared footage across the community. While these depictions showed real benefits, critics argued the ad normalized mass surveillance infrastructure that could enable facial recognition, warrantless police access, and comprehensive tracking of people's movements through public and semi-public spaces.

What happened in the Nancy Guthrie case with Google Nest?

Journalist Nancy Guthrie requested deletion of her Google Nest camera footage, and Google complied. However, months later when police investigated an incident, they recovered footage from her deleted camera using archived backups. This revealed that cloud-based camera systems retain deleted footage in backup systems longer than users expect, and that companies can recover "deleted" data upon law enforcement request.

What can I do to protect my privacy regarding surveillance cameras?

You can avoid installing Ring or similar cloud-based cameras if possible, choose alternative camera systems with better privacy protections, minimize the data your cameras collect by disabling unnecessary features, regularly delete footage, avoid sharing video with neighbors or law enforcement, support privacy-focused regulation and advocacy, and educate others about surveillance implications. Additionally, research the data practices of any smart home device before purchasing.

How does Ring work with law enforcement?

Ring has provided law enforcement with access to its Neighbors app, allowing police to request footage from cameras in specific areas without serving individual warrants. This system works through voluntary user consent, creating a faster process for law enforcement to obtain surveillance footage while bypassing traditional warrant procedures that include judicial oversight.

What does the future of Ring surveillance look like?

If current trends continue, Ring cameras will become increasingly ubiquitous with deeper integration with Amazon Alexa and other services, facial recognition capabilities will be deployed either by Ring or law enforcement, AI systems will analyze patterns and predict suspicious behavior, and Ring footage will become a standard investigative tool for police departments. The result could be comprehensive surveillance networks that track people's movements and behaviors throughout neighborhoods and cities.

Key Takeaways

- Ring's Super Bowl ad raised legitimate concerns about normalizing comprehensive neighborhood-wide surveillance infrastructure.

- Ring footage can be recovered by law enforcement without traditional warrants through the Neighbors app system.

- Cloud-based camera systems retain supposedly deleted footage in backup archives, limiting user control over data.

- Amazon is investing in facial recognition AI that would enable tracking people across multiple cameras in a city.

- The lack of meaningful alternatives and regulation means Ring's surveillance expansion continues largely unchecked.

- Privacy concerns extend beyond Ring to broader questions about who controls our data and how it's used.

Related Articles

- Ring Cancels Flock Safety Partnership Amid Surveillance Backlash [2025]

- How to Disable Ring's Search Party Surveillance Feature [2025]

- Ring's Police Partnership & Super Bowl Controversy Explained [2025]

- Google Recovers Deleted Nest Videos: What This Means for Your Privacy [2025]

- FBI Recovers Nest Camera Footage: What This Means for Your Smart Home Privacy [2025]

- Technology Powering ICE's Deportation Operations [2025]

![Ring's Super Bowl Ad Backlash: The Surveillance Debate [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/ring-s-super-bowl-ad-backlash-the-surveillance-debate-2025/image-1-1771000901775.jpg)