Introduction: The Slippery Slope From Lost Dogs to Mass Surveillance

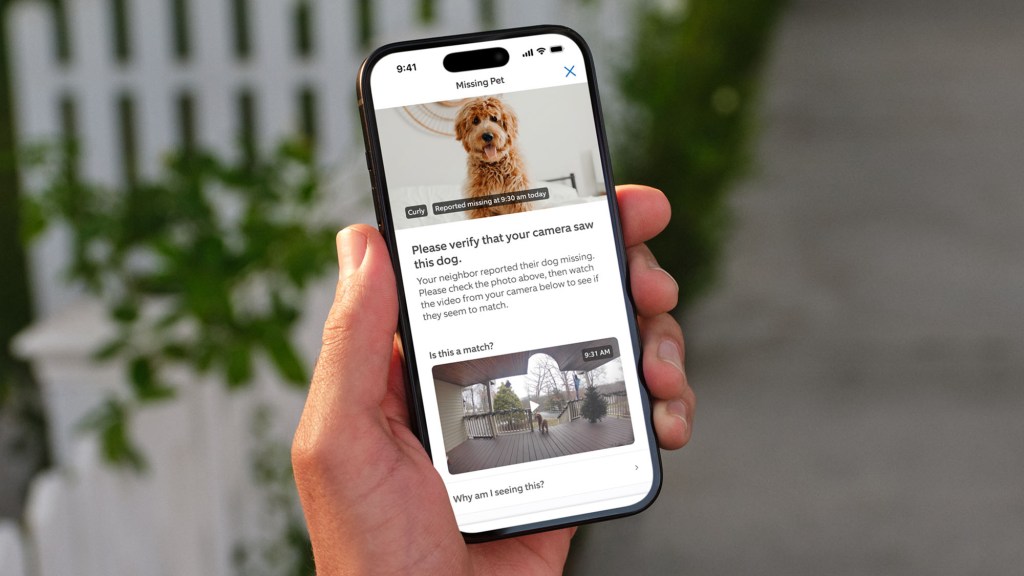

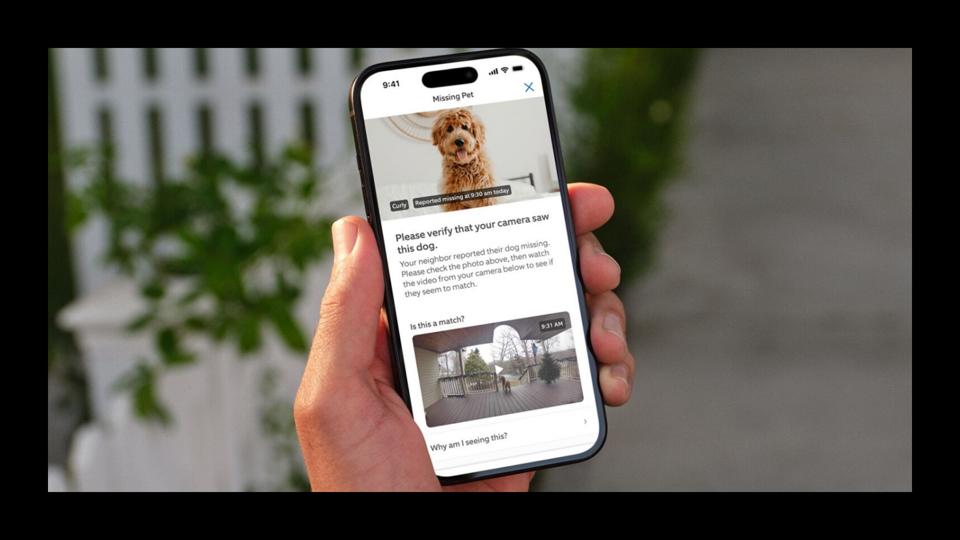

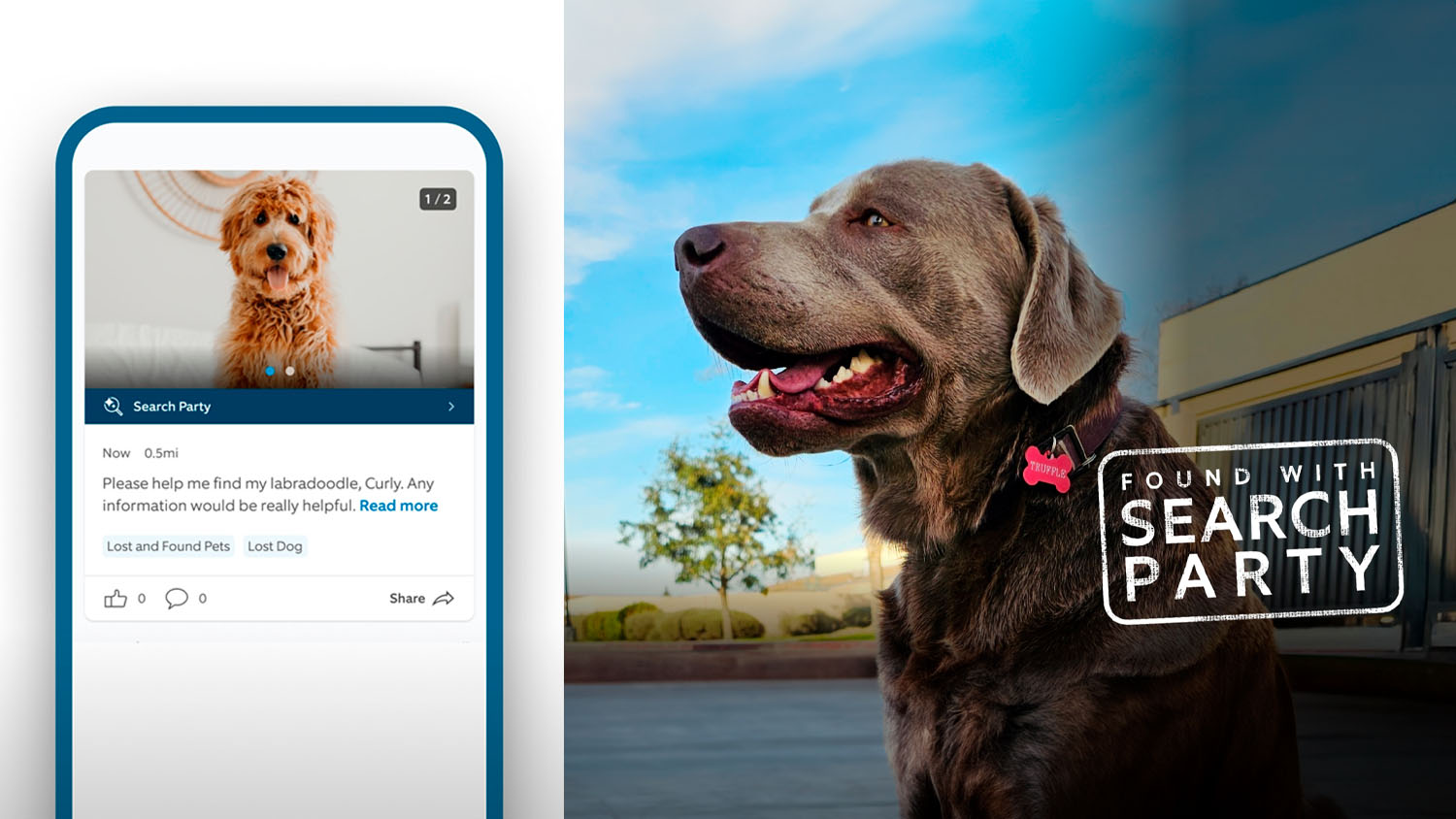

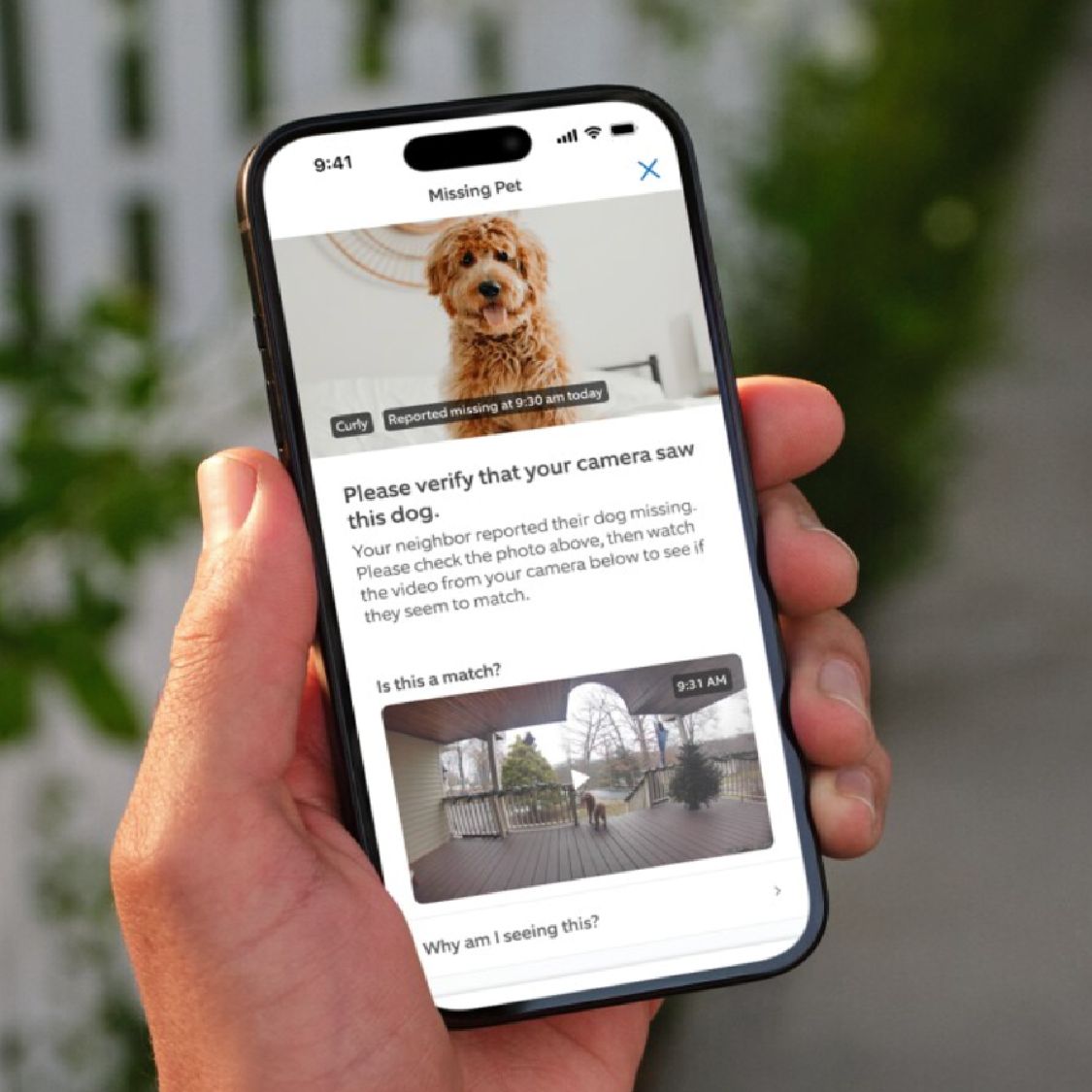

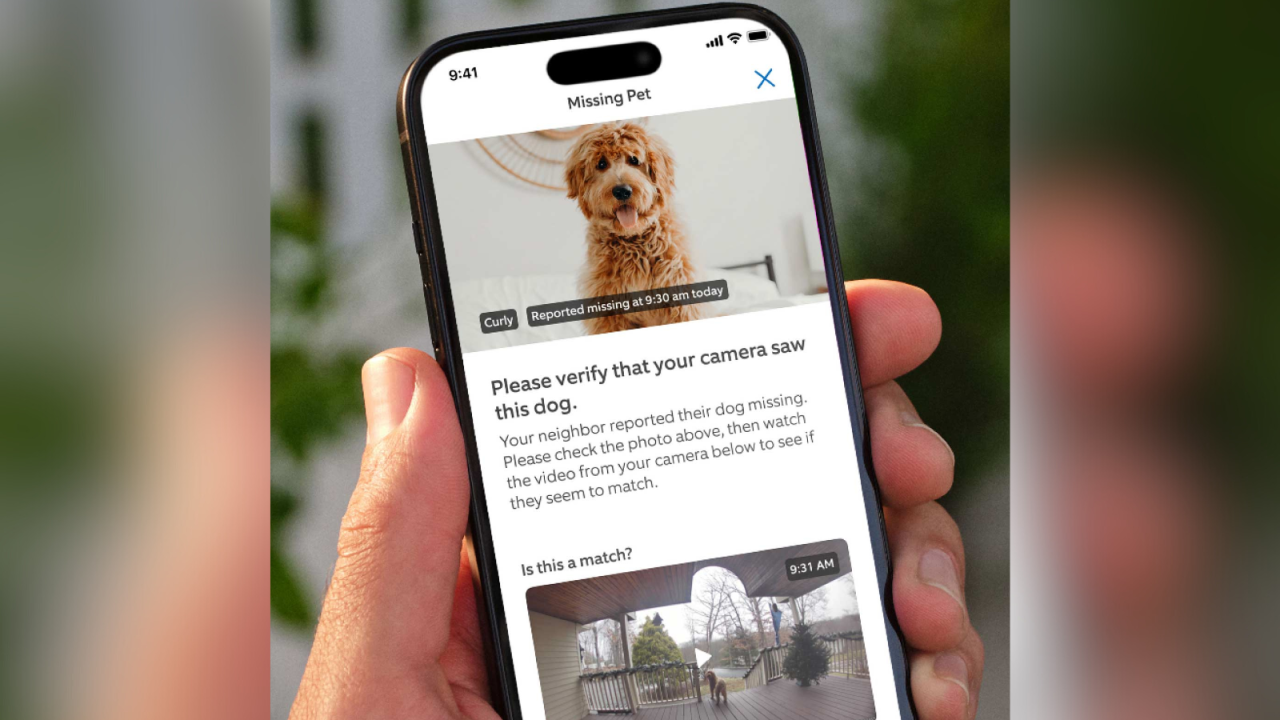

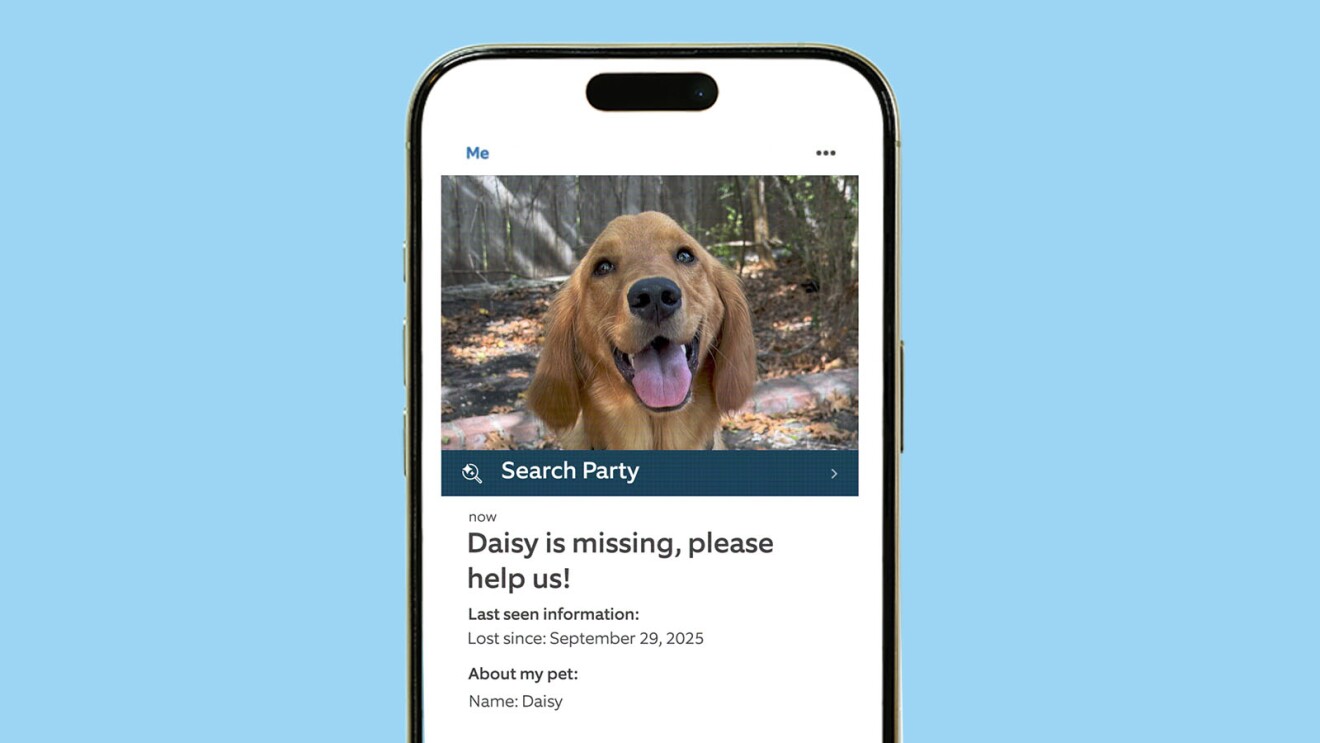

When Ring launched its Search Party feature in late 2024, the company framed it as a heartwarming solution to a genuine problem. Pet owners could post about their missing dogs, and neighbors with Ring cameras could help search through footage—a clever use of existing infrastructure to do something genuinely good.

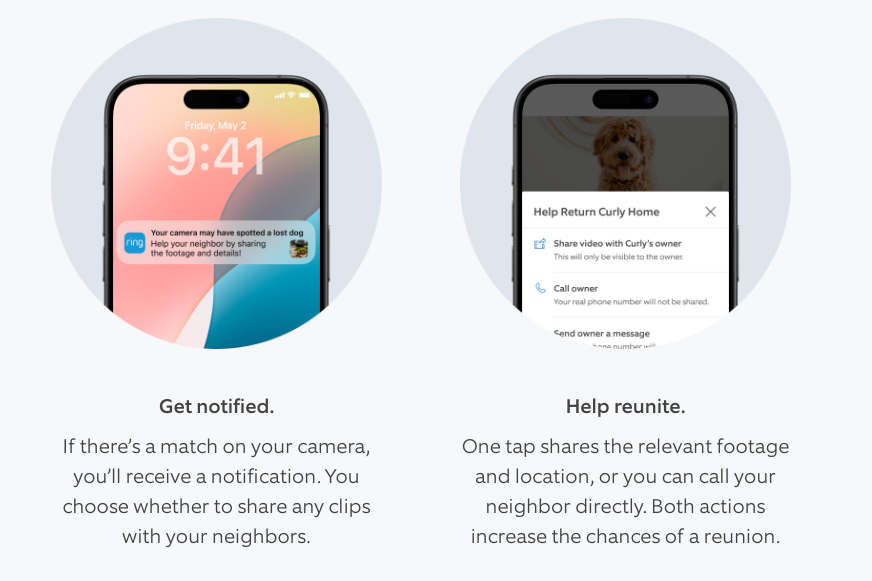

Then came the Super Bowl commercial. The ad showed a Lost Dog poster, Ring cameras scanning neighborhoods, AI algorithms combing through footage, and the reunion with a happy golden retriever. It looked almost wholesome. Almost.

But here's what caught everyone's attention: if Ring can search for dogs, what stops it from searching for people? That question isn't theoretical anymore. A leaked internal email from Ring founder Jamie Siminoff, obtained by 404 Media, reveals the company's true ambitions. The email says Ring can now "see a future where we are able to zero out crime in neighborhoods." Search Party for dogs wasn't the endgame. It was the first domino.

This revelation hits different when you consider what Ring has already built. Facial recognition. Direct ties to law enforcement through Community Requests. An AI-powered visual search that can find virtually anything in any video. And now, a crowdsourced scanning network that operates by default across millions of doorbell cameras.

The company maintains these tools are separate, that Search Party currently can't find people, and that sharing footage requires consent. But the leaked email suggests leadership views these as building blocks toward something larger. Something comprehensive. Something that sounds, to critics, like a dystopian surveillance apparatus.

This isn't about whether Ring's intention is malicious. It's about whether the infrastructure they're building—intentionally or not—creates the conditions for something problematic. And whether "we can stop crime" justifies the massive shift in how we're watched in our own neighborhoods.

TL; DR

- Search Party started small: Ring positioned Search Party for lost dogs as a cute, practical feature that helps neighbors help each other

- But the leaked email reveals ambitions: Founder Jamie Siminoff wrote that Search Party is "the foundation" for "zeroing out crime in neighborhoods," suggesting much broader surveillance applications

- Ring has already assembled the pieces: Facial recognition, law enforcement partnerships, AI-powered visual search, and a default-enabled crowdsourced scanning network all exist today

- Privacy concerns are legitimate: Critics worry the company is building infrastructure that could enable mass surveillance, whether intentionally or through gradual feature expansion

- The consent problem remains: While Ring says sharing footage is voluntary, Search Party opt-out happens at the network level, not the individual camera level

- Bottom line: Ring's public framing of Search Party as a pet-finding tool masks strategic expansion toward neighborhood-wide surveillance capabilities

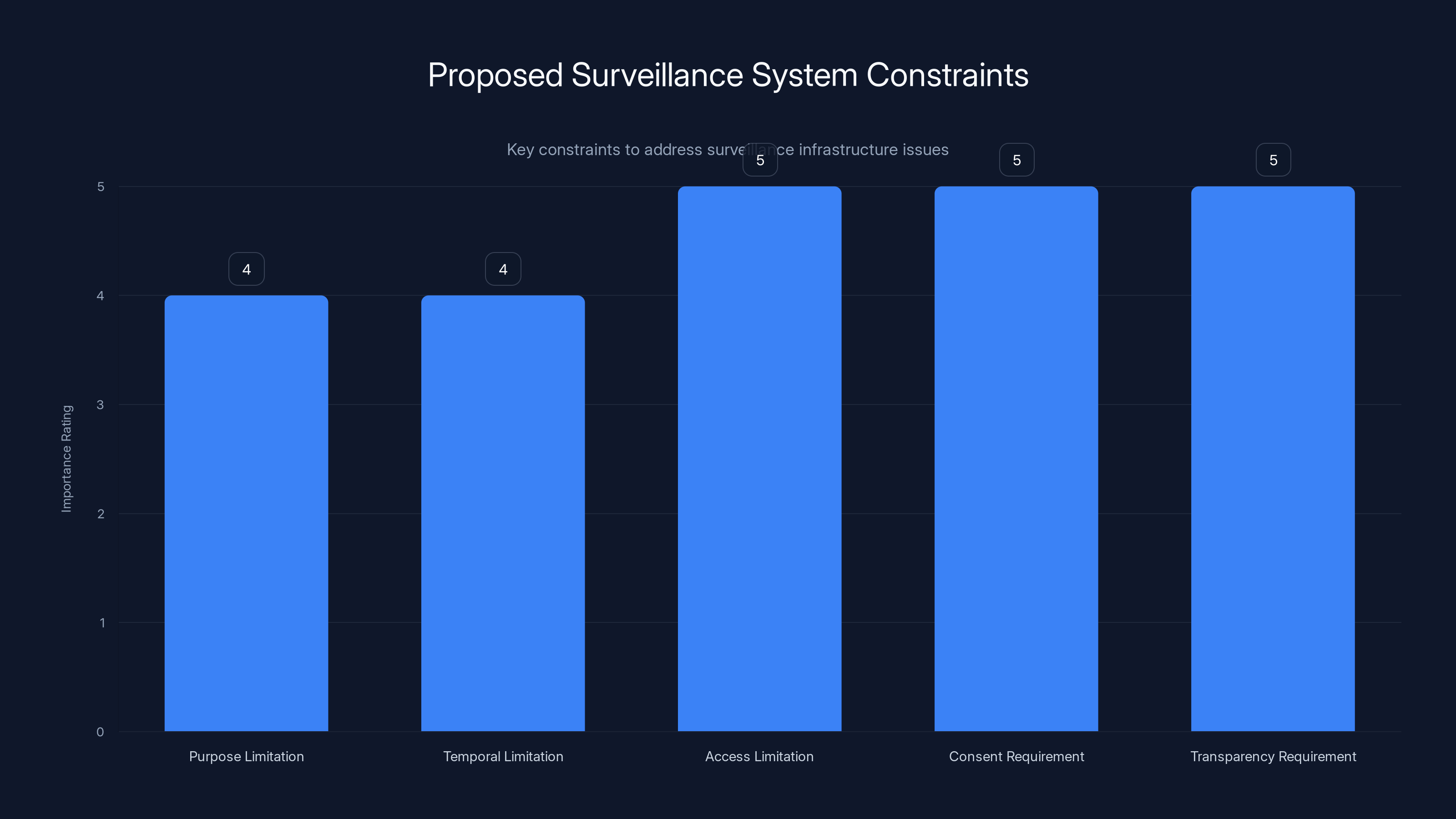

Implementing these constraints can mitigate the risks associated with surveillance systems by ensuring clear rules and transparency. Estimated data based on topic discussion.

What Search Party Actually Is (And How It Works)

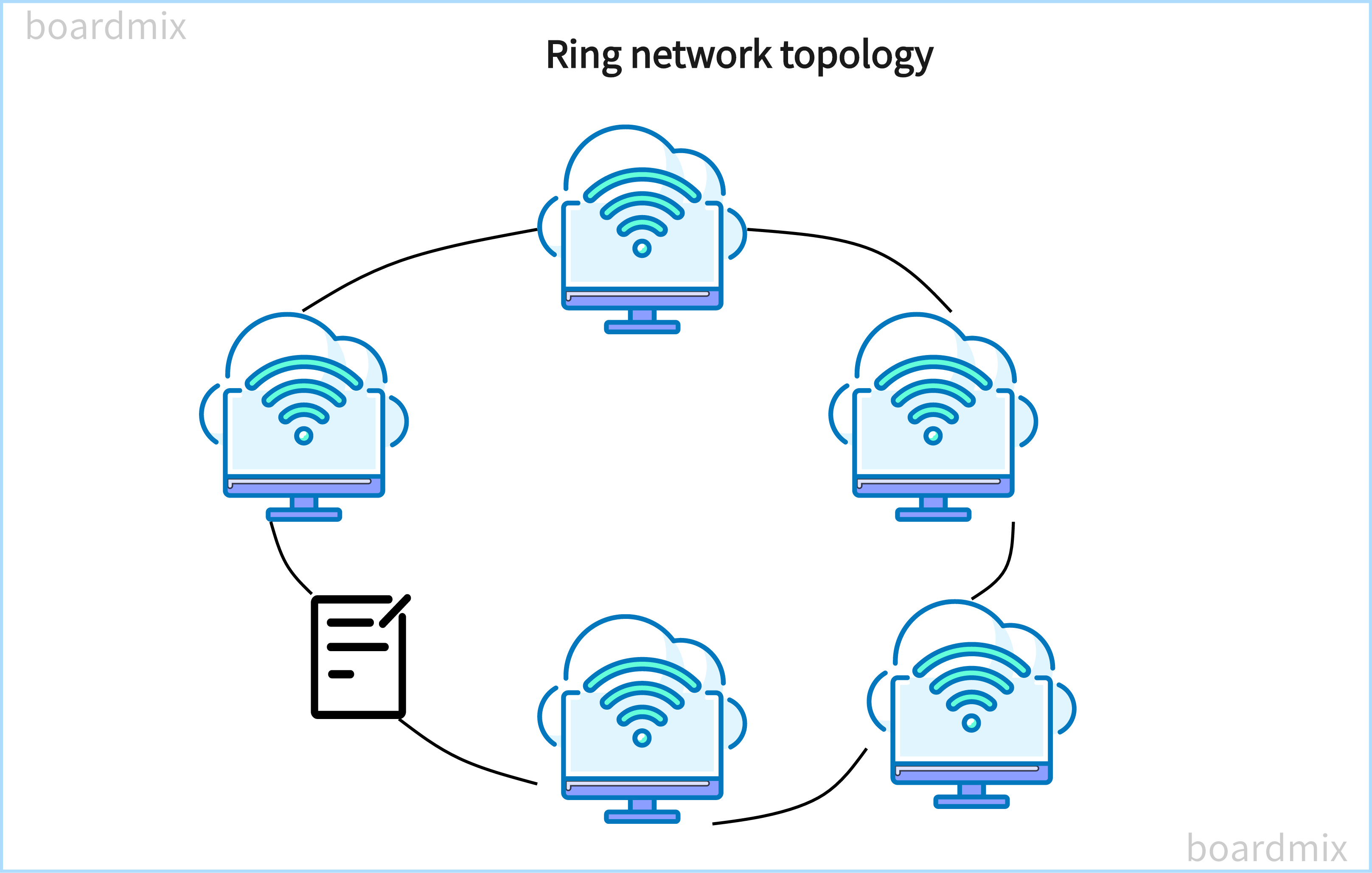

Search Party isn't magic, though it probably sounds like it. It's fundamentally a crowdsourcing system that turns Ring's network of cameras—the company claims over 20 million devices—into a searchable database.

Here's the actual mechanics. Someone reports a lost dog through the Ring Neighbors app. That report triggers a notification to nearby Ring users asking if they can help search. Those users can then browse through footage from their own cameras and shared clips from neighbors' cameras, looking for the missing pet. The AI helps by identifying what it thinks are dogs in the footage, automatically flagging potential matches.

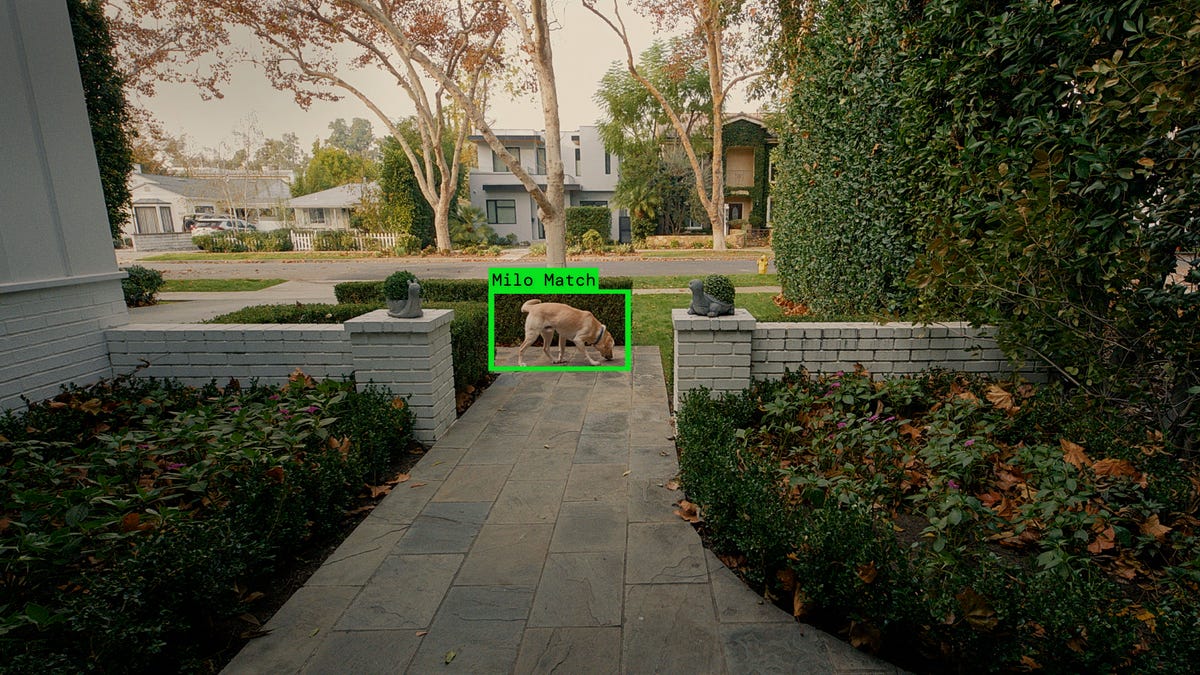

The key difference between this and just asking neighbors manually: it's systematic, searchable, and AI-assisted. Without the technology layer, you'd be relying on humans scrolling through hours of grainy doorbell footage. With it, the AI can process thousands of clips and surface likely matches in minutes.

Ring's cameras already had the ability to record and analyze video locally. Search Party didn't require new hardware—it required new software that could stitch together the ecosystem. It required a system where footage could be shared across the network. It required an AI model trained to recognize dogs. And it required a way to surface relevant results to the right people at the right time.

What makes this different from existing Ring features is the crowdsourcing angle. A single Ring owner can already search their own footage for anything they want—people, cars, animals, you name it. But Search Party brings the collective power of thousands of cameras to bear on a single query.

That's the innovation. That's also where the surveillance implications live.

Recently, Ring expanded Search Party to find wildfires. You can already see the trajectory. Lost dogs. Wildfires. What comes next? Missing people? Suspects? Stolen vehicles? Each expansion seems reasonable in isolation. But stacked together, they show where the infrastructure is heading.

Amazon's strategic investments in Ring are distributed across acquisition, integration, discounts, and capability expansion, with a significant focus on expanding capabilities. Estimated data.

The Leaked Email: What Siminoff Actually Said

The email, sent in October 2024 after Search Party's launch, is worth reading carefully because it reveals how the company's leadership actually thinks about this feature.

Siminoff wrote: "This is by far the most innovative that we have launched in the history of Ring. And it is not only the quantity, but quality. I believe that the foundation we created with Search Party, first for finding dogs, will end up becoming one of the most important pieces of tech and innovation to truly unlock the impact of our mission. You can now see a future where we are able to zero out crime in neighborhoods."

Let's parse that. "The foundation we created with Search Party, first for finding dogs"—that phrase "first for" matters. It's the qualifier that changes everything. This isn't "we made a thing for finding dogs." It's "we made foundational technology, and we're starting by finding dogs."

"Zero out crime in neighborhoods." Not "reduce" crime. Not "help police respond faster." Zero it out. That's ambitious language that suggests a vision of total crime prevention through total visibility.

The email continues: "So many things to do to get there but for the first time ever we have the chance to fully complete what we started." Fully complete what they started. That phrasing suggests a multi-phase plan that's been in motion longer than Search Party's public launch.

Ring confirmed the email was authentic. The company's response was careful: they said the email reflects Siminoff's personal vision and aspirations, but doesn't necessarily reflect the company's immediate product roadmap. That distinction matters legally, but it doesn't calm the concerns.

Why? Because Siminoff isn't some middle manager with big dreams. He founded Ring in 2013, sold it to Amazon for a reported $1 billion in 2018, and still runs the company. His vision is the company's direction.

Ring's Existing Surveillance Arsenal

To understand why the leaked email matters, you need to understand what Ring has already built. Search Party doesn't exist in isolation. It's the newest piece of an increasingly comprehensive surveillance apparatus.

Facial Recognition

Ring quietly added facial recognition to its cameras in 2024. The company frames it as a privacy-protective feature—it can recognize people you designate (like family members) and alert you when they're recognized. But it's also identifying everyone else, capturing their faces, and storing biometric data. Ring says you can enable or disable this feature, and that data stays on device or in your Ring account. But you're still creating a facial database of your neighborhood whether you realize it or not.

Community Requests and Law Enforcement Integration

Ring's Neighbors app has a feature called Community Requests. Local police departments can post requests for video footage related to crimes. Residents can choose to share or not share their footage. Sounds voluntary. But researchers have found that law enforcement uses these requests frequently and creatively—sometimes casting extremely wide nets asking for footage of "suspicious activity" in an entire neighborhood for multiple days.

Ring has formalized these relationships. The company maintains a law enforcement portal. Police departments can set up official accounts. Some departments have hundreds of thousands of Neighbors app users in their communities.

Local Video Search

Ring's cameras can already search their own footage for virtually anything. People, cars, pets, packages, motion. The AI model is trained to identify objects and activities. A single homeowner can search their own recordings with impressive precision. This isn't controversial on its own—you own your own camera footage. But it's the foundation for everything else.

The Neighbors App Ecosystem

The Neighbors app is where the network effects happen. Crime alerts. Package theft reports. Suspicious activity posts. Community Requests from police. All flowing through a central platform. Users get conditioned to report things. To seek confirmation from neighbors. To think of their community as a security collective.

Search Party is just the latest evolution of that ecosystem.

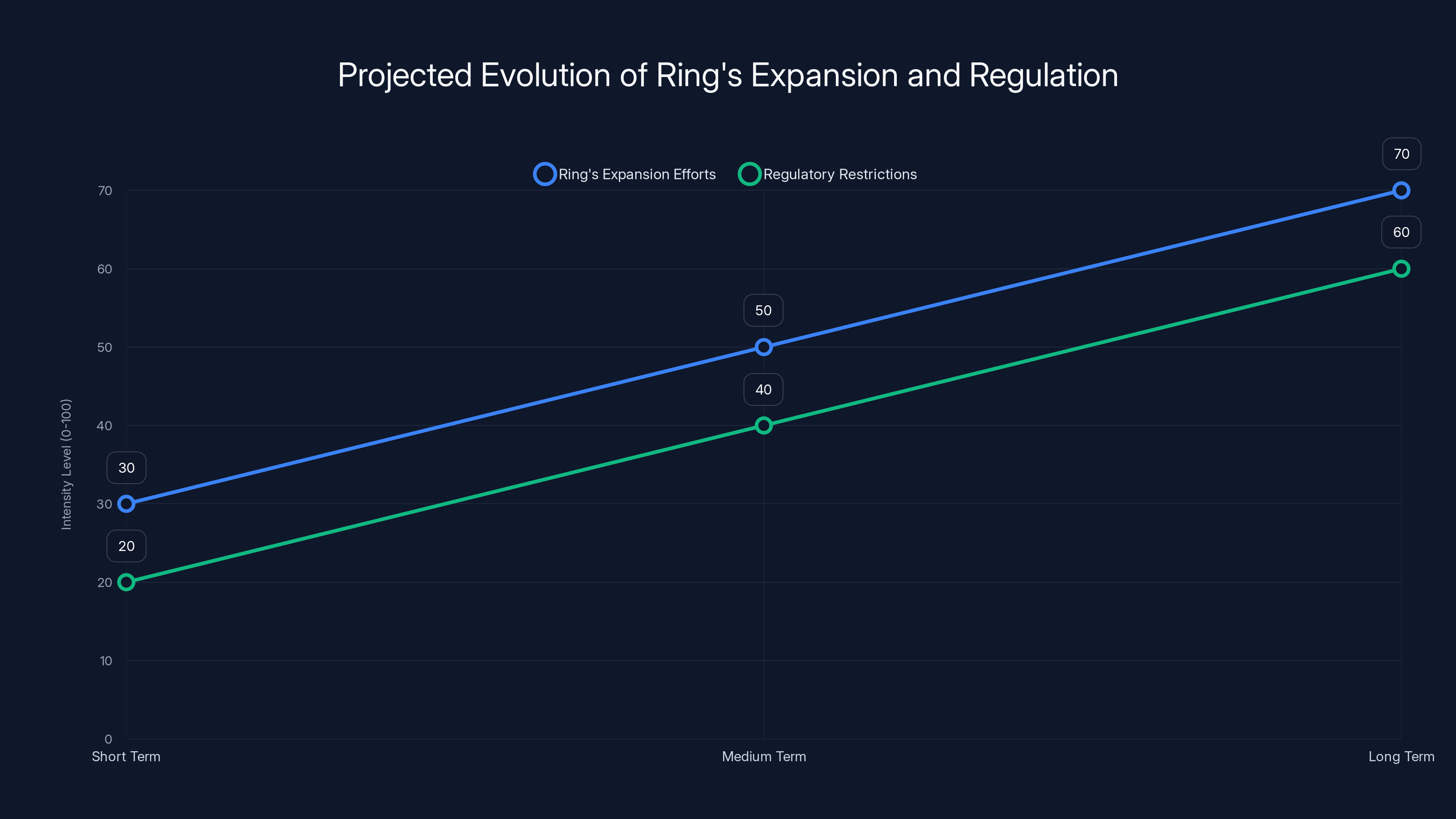

Estimated data suggests Ring will cautiously expand its capabilities while facing increasing regulatory scrutiny over time. Expansion efforts and regulatory restrictions are projected to intensify in parallel.

The Privacy Problem: Beyond Individual Consent

Ring's standard defense goes like this: sharing footage is voluntary. A homeowner can post to Community Requests or participate in Search Party. Nobody forces them. The company isn't creating surveillance—it's enabling community members to help each other.

That logic breaks down when you think about how these systems actually work at scale.

First, there's the opt-out problem. Search Party is on by default for anyone with a Ring subscription. You have to actively find the setting and turn it off. Most people won't. The defaults are doing the heavy lifting here, and the default is "yes, participate in neighborhood surveillance."

Second, there's the network effect problem. Even if you opt out of Search Party, if enough neighbors participate, your neighborhood is still fully surveilled. You can't actually prevent the surveillance of your street. You can only prevent your own camera from contributing to it.

Third, there's the consent scope problem. When you agree to Neighbors app terms, you're consenting to the app as it exists today. You're not consenting to future features. Ring can expand Search Party's capabilities—add people, add vehicles, add biometric matching—and your old consent doesn't cover the new scope.

Fourth, there's the function creep problem. A feature built for finding lost dogs can be repurposed. Law enforcement might start using Search Party. Insurance companies might request access. Marketers might analyze traffic patterns. Each of these seems like a small step. Together, they're infrastructure for something much larger.

Ring says Search Party can't currently find people. That's true today. But the technological capability exists. Ring has facial recognition. It has AI models that can identify humans. It has a crowdsourced network of cameras. The only thing stopping it from searching for people is a policy decision. Policy decisions can change. And a leaked email from the founder suggesting he wants to "zero out crime in neighborhoods" suggests policy might change.

The company's public statements try to separate these concerns. Search Party for dogs isn't the same as Search Party for people. Facial recognition is optional. Law enforcement partnerships are transparent. But critics argue that adding these pieces together—a crowdsourced camera network, facial recognition, police partnerships, and a founder explicitly discussing crime prevention through visibility—creates the infrastructure for something that looks like mass surveillance, whether that's the stated intent or not.

Why "Zeroing Out Crime" Is a Dangerous Goal

Siminoff's language in the leaked email—"zero out crime in neighborhoods"—sounds good on the surface. Who doesn't want crime to decrease?

But zero crime is impossible. And the surveillance infrastructure built in pursuit of zero crime has historically enabled abuses.

In cities with comprehensive CCTV systems, those cameras don't just catch criminals. They've been used to track protesters, to monitor politically disfavored groups, to enable harassment. In countries with extensive surveillance, the infrastructure built for crime prevention gets repurposed for social control. Not always immediately. But eventually.

There's also a measurement problem. If Ring's goal is to reduce crime, who measures that? Ring can count how many lost dogs are found (good metric). But neighborhood crime is harder to measure. You could measure reported crimes, but that's influenced by policing practices. You could measure victimization surveys, but that's expensive and complicated. More likely, Ring will measure whatever they can measure—camera engagement, searches completed, tips provided—and claim those correlate with crime reduction.

There's also an inequality problem. Affluent neighborhoods will have dense Ring camera coverage because Ring cameras cost money. Poorer neighborhoods will have less. So the "crime prevention" infrastructure will be denser in neighborhoods that can afford it, and sparser in neighborhoods that need it most. That's not crime prevention. That's surveillance comfort for the wealthy.

And there's the false confidence problem. If you can see everything in your neighborhood—every person, every car, every moment—you start to feel safe in ways that might not be real. You might let your guard down in places that are actually dangerous. You might trust the cameras more than you trust your own judgment. You might demand more cameras, more monitoring, more control, chasing the illusion of perfect safety.

Estimated data suggests a significant reduction in neighborhood crime over five years with the implementation of Ring's Search Party technology, aiming to 'zero out' crime.

Amazon's Role: The Silent Shareholder

It's easy to blame Siminoff personally. He's the public face, he sent the ambitious email, he's stated publicly that he believes AI can prevent crime. But Amazon owns Ring. That ownership matters.

Amazon bought Ring for approximately $1 billion in 2018. Since then, Amazon has integrated Ring into its smart home ecosystem. Amazon offers Ring hardware discounts with Prime memberships. Amazon promotes Ring cameras through Echo devices. Amazon has invested billions in expanding Ring's capabilities.

Why? Because Ring gives Amazon something valuable: real-time visibility into neighborhood patterns. Traffic flows. Foot traffic. Time-of-day patterns. Emergency services responses. All the data that could be useful for logistics, delivery optimization, insurance pricing, or market analysis.

Amazon doesn't need to use Search Party maliciously. It just needs access to the aggregate data. "Which neighborhoods have high theft rates?" "Which streets see the most foot traffic?" "How long do emergency responses take?" These insights are valuable to Amazon's business in ways that have nothing to do with crime prevention.

And Amazon has significant law enforcement relationships already. It owns Ring, but it also owns AWS cloud services used by police departments. It owns Rekognition, a facial recognition service that law enforcement uses. It has a public-private partnership with law enforcement through its various security and surveillance divisions.

The combination is worth thinking about. Amazon doesn't need to mandate that Ring expand Search Party to surveillance. The incentive structures are aligned. More cameras, more data, more capability—that's good for Amazon's business, good for Ring's status as essential security infrastructure, and good for Siminoff's vision of crime prevention through visibility.

The Super Bowl Ad and the PR Disaster

Ring's Super Bowl commercial is worth analyzing because it's where the company thought it could safely introduce Search Party to a mainstream audience.

The ad opens with a lost dog poster. A concerned owner. Neighbors with Ring cameras helping search. The AI finds the dog. Reunion. Emotional payoff. The message: Ring cameras help neighbors help each other in meaningful ways.

It's effective marketing. It hits emotional notes. It makes surveillance feel warm and community-focused.

But the internet noticed something the ad didn't explicitly state: if the technology can find dogs, it can find people. The inference isn't paranoid. It's logical. The company that built this technology isn't hiding its ambitions either—Siminoff has said publicly that he wants to reduce crime through better visibility.

The backlash was swift. Critics pointed out that the same infrastructure could be used to track protesters, to monitor minorities, to enable harassment. Researchers published papers about how Ring's network could be weaponized. Privacy advocates called for regulation. Even some tech journalists who usually defend innovation companies acknowledged the concerns were legitimate.

Ring responded by saying Search Party is currently limited to dogs and wildfires. The implication: stop worrying about the future, focus on what exists today. But the leaked email makes it clear the future expansion is the point.

This is where brand trust matters. Companies that expand features gradually, without being transparent about the direction, face more backlash than companies that are honest about their plans. Ring tried to keep Search Party looking small and wholesome, then got caught with evidence of bigger ambitions. That's a trust problem that doesn't go away just because the company says "we're not doing that yet."

Estimated data suggests that while the current focus is on finding lost pets, future expansions may include crime prevention and broader surveillance capabilities.

How Search Party Actually Expands (The Technical Roadmap)

The leaked email doesn't specify how Ring would expand Search Party beyond dogs and wildfires. But if you understand the technology, the logical progression is visible.

Phase One: Lost Dogs (Current)

Searchable for: dogs

Who can initiate: community members

Time window: presumably 24-48 hours after report

AI capability: object detection for dogs

Phase Two: Stolen Property (Likely)

Searchable for: packages, bicycles, vehicles

Who can initiate: property owners or police

Time window: wider window, maybe 7 days

AI capability: object detection + property description matching

Why: packages are stolen constantly. Ring users would use this aggressively. It scales easily because the same AI models can be retrained on different objects.

Phase Three: Missing People (Possible)

Searchable for: people matching descriptions

Who can initiate: family members or law enforcement

Time window: weeks

AI capability: facial recognition + description matching

Why: this is what Siminoff is actually talking about. If Search Party can find a dog, finding a missing child or elder seems like an obvious expansion. The emotional case is strong. The technology exists.

Phase Four: Suspects (The Surveillance Endpoint)

Searchable for: people matching descriptions provided by police

Who can initiate: law enforcement

Time window: indefinite

AI capability: facial recognition, behavior pattern matching, temporal analysis

Why: this is where the infrastructure becomes surveillance. Not for lost dogs. For policing.

Each phase seems reasonable in isolation. Each builds on the technology of the previous phase. Each gets normalized. By the time you reach Phase Four, the idea of searching for suspects seems like a natural extension of searching for lost dogs.

But each phase also requires policy decisions. Ring could make different choices. It could decline to expand to people. It could limit law enforcement access. It could require explicit consent rather than defaults. But the technological capability is there, waiting, and the leaked email suggests the company's leadership wants to use it.

Regulatory and Legal Challenges Ahead

Ring's Search Party feature exists in a weird regulatory space. It's not quite law enforcement. It's not quite a utility. It's private infrastructure operating at public scale.

In the EU, Search Party would likely face challenges under GDPR. The feature processes biometric data (even if just for dogs). It creates records of people and movement patterns. It violates privacy principles around data minimization and purpose limitation. The EU might not ban the feature, but they'd require much stronger opt-in consent, clearer limitations on how data can be used, and explicit prohibitions on law enforcement access.

In the US, the regulatory environment is more fragmented. Some cities have considered restricting Ring's law enforcement partnerships. Some states have passed laws around facial recognition. But nothing comprehensively addresses networked surveillance systems like Search Party.

There are also Section 230 implications. Ring, like many platforms, claims Section 230 protection—if a user shares a video through Search Party and someone claims that video infringes their rights, Ring argues it's not responsible because it didn't create the content. But Section 230 is increasingly under legal pressure, and a comprehensive surveillance network might face different arguments.

Biggest legal risk: if Ring expands Search Party to people before getting clear regulatory guidance, and law enforcement uses it in ways that facilitate harassment or civil rights violations, Ring could face major liability. The company would likely argue it's not responsible for how police use its tools. But a feature explicitly designed for law enforcement participation, run by a company with known law enforcement relationships, might face tougher scrutiny.

The pie chart illustrates the equal distribution of key privacy concerns associated with Ring's Search Party, highlighting the opt-out problem, network effect, consent scope, and function creep. Estimated data.

What Other Companies Are Doing (And Thinking)

Ring isn't the only camera company expanding AI-powered search. But it's the first to explicitly propose something at this scale.

Google Nest cameras have AI detection (people, dogs, vehicles, etc.) but the search is limited to your own footage. Google hasn't proposed a crowdsourced search network.

Logitech's security cameras are smart but limited to local processing.

Wyze is budget-focused and hasn't proposed advanced features.

The difference is strategic. Ring decided early on that the value would come from the network. One Ring camera is useful. Two hundred thousand Ring cameras in a city? That's infrastructure. That's data. That's power.

Ring also benefits from Amazon's resources and ambitions. Most other camera companies don't have a trillion-dollar tech conglomerate behind them willing to fund aggressive feature expansion and take long-term views on profitability.

So Ring is the test case. If Search Party expands as the leaked email suggests, other companies will follow. If Ring faces serious regulatory pushback, others might be more cautious.

There's also the opportunity for a competitor to position itself as "privacy-focused Ring." A camera company that explicitly limited its AI search to user-owned footage, that rejected law enforcement access, that required explicit opt-in for any feature, that publicly committed to not expanding to person-search. That company could capture the privacy-conscious market. But it would require turning down significant business opportunities, and most tech companies aren't willing to do that.

The Real Surveillance Infrastructure Problem

People sometimes frame the Ring debate as "is Ring evil?" That's the wrong question. It assumes surveillance comes from malicious actors with bad intentions. Reality is more subtle.

Surveillance infrastructure becomes problematic not because of intent, but because of capability and incentive misalignment. Ring's founder might genuinely believe AI-powered visibility reduces crime. He might be sincere. But the infrastructure he's building—a network where law enforcement has easy access, where facial recognition operates by default, where crowdsourcing normalizes sharing footage—that infrastructure enables abuse regardless of intent.

The problem isn't Ring specifically. It's that we're building surveillance systems without clear rules about what they can be used for, who can access them, and how to prevent abuse.

Historically, this is how invasive surveillance powers get created. Not through dramatic governmental takeover, but through incremental, reasonable-seeming expansions. A feature to find lost dogs. A request to help law enforcement. Integration with emergency services. Better algorithms. Easier access. Each step seems justified. The whole becomes dystopian.

The solution isn't banning Ring. It's being explicit about constraints upfront. The rules should be:

-

Purpose limitation: Ring cameras can only be searched for the specific purpose consented to. Searching for a lost dog doesn't grant permission to search for people.

-

Temporal limitation: Search requests expire. You can search for 24 hours after a report, not indefinitely.

-

Access limitation: Law enforcement doesn't get automatic access to Search Party. They have to go through the same community request process as ordinary citizens.

-

Consent requirement: Participation should be opt-in, not opt-out. Search Party is an active choice, not a default.

-

Transparency requirement: Any expansion of Search Party should be publicly announced with explicit consent requests. No silent feature upgrades.

-

Data deletion: Footage retrieved through Search Party isn't kept forever for future searches. It's deleted after the search concludes.

These constraints wouldn't prevent Ring from operating. They'd just prevent it from becoming infrastructure for comprehensive neighborhood surveillance.

But they'd also cost Ring money. Deleted data can't be monetized. Limited law enforcement access means less partnership revenue. Opt-in features have lower participation rates. So Ring will resist these constraints.

That's where regulation comes in. If companies won't self-constrain powerful technology, regulation has to do it for them.

Why This Matters Beyond Ring

The Ring situation is a test case for a bigger question: are we okay with comprehensive surveillance infrastructure?

Ring's 20+ million cameras aren't unique anymore. Samsung and other companies are selling smart video doorbell cameras. Apple is integrating surveillance features into its Home Kit ecosystem. Every major tech company is trying to own the surveillance layer of smart homes.

As these networks grow, they become infrastructure. Governments will pressure companies for access. Companies will justify access as helping law enforcement. Feature expansion will seem reasonable. Before you know it, every neighborhood in America has comprehensive video surveillance, and we'll be arguing about the constraints instead of whether it should exist.

Ring got ahead of the curve. It's the first to propose explicit person-search infrastructure at scale. But it won't be the last.

The question isn't really about Ring anymore. It's about whether we want to live in neighborhoods where everything is recorded and searchable. Whether we're okay with police having direct access to cameras. Whether we think the privacy cost of comprehensive surveillance is worth the security benefit.

Those are societal questions, not tech questions. Ring is just the vehicle forcing us to ask them.

The Path Forward: What Happens Next

So where does this go from here?

Short term: Ring will probably slow its public expansion plans. The leaked email created a PR problem. Privacy advocates are paying attention. Regulators are watching. The company will focus on defending the current Search Party (dogs and wildfires) and demonstrating responsible operation.

Simultaneously, Ring will probably work behind the scenes on the technical capabilities for person-search. They'll build the models, train the algorithms, prepare the infrastructure. When the time is right—when enough time has passed, when the controversy fades, when another company tries something similar—they'll propose the expansion as a natural next step.

Medium term: Law enforcement will push for broader access. Some police departments will ask Ring directly for person-search capabilities. Others will try to use Community Requests to approximate it ("looking for a person of interest"). Ring will probably accommodate these requests gradually, framing them as helping law enforcement.

Regulators will start paying attention. Some municipalities will propose restrictions. Some states will pass laws. Nothing comprehensive, because surveillance regulation is hard. But enough to create friction.

Long term: We'll probably end up with a patchwork approach. Some cities allow extensive law enforcement use of Ring data. Others restrict it sharply. Privacy advocates will lose some battles and win others. Ring will expand where it can, pull back where it can't. The infrastructure will grow, but more slowly and carefully than Siminoff's leaked email suggests.

The real outcome will depend on whether people actually care enough to demand constraints. So far, Ring's growth suggests people care more about the convenience of neighborhood monitoring than the privacy costs. That could change. But it probably won't unless something bad happens—unless Search Party data is used to enable harassment, to target protesters, to violate someone's rights in a way that becomes public.

Then people will care. Then regulation will happen. Then Ring will adapt.

But by then, the infrastructure will already exist.

Best Practices for Privacy-Conscious Neighbors

If you care about this stuff, here's what you can actually do:

Take control of your own camera

If you own a Ring camera, go into your app settings right now. Find Search Party. Turn it off. Turn off any opt-in data sharing. Review your privacy settings thoroughly. Ring's default is "yes, participate in surveillance." Change that default.

If you don't own a Ring camera, thank your past self for good decisions and move on.

Talk to your neighbors

You can't control what other people do with their cameras. But you can talk to them. Share your privacy concerns. Ask them to disable Search Party. Build community pressure for privacy-protective settings.

This is actually more effective than it sounds. Neighborhoods where people talk about surveillance are neighborhoods where surveillance grows more slowly.

Stay informed about expansion

Ring will expand Search Party eventually. When it happens, it'll be buried in a product update or announced quietly on a blog post. Follow tech news. Read privacy advocates' analyses. Know what's changing before it affects you.

Support regulation

Contact your representatives. Ask them to regulate surveillance cameras. Support organizations that push for surveillance constraints. Vote based on candidates' privacy stances if it matters to you.

Regulation is the only thing that will actually constrain Ring at scale.

Consider your own participation

Even if you don't own a Ring camera, you might participate in Neighbors if someone shares a video with you. Every time you engage with shared surveillance, you normalize it. Think about whether you want to be part of that infrastructure.

The Deeper Question: What Kind of Neighborhood Do We Want?

Ultimately, the Ring debate is asking a question that goes beyond surveillance technology.

What kind of neighborhoods do we want to live in? What's the right balance between security and privacy, between trust in infrastructure and trust in each other, between visibility and freedom?

There's a vision where Ring represents: neighborhoods are safer when they're heavily surveilled. When everyone watches everyone. When AI helps identify threats. When law enforcement has tools to find criminals quickly. This isn't necessarily wrong. Cities with comprehensive surveillance do experience lower crime rates in some studies. The safety is real.

But there's a cost to that safety. It's the freedom to exist in public without being recorded. It's the ability to make mistakes or have bad days without it being captured and searchable forever. It's the right to not be tracked, not to be profiled, not to be observed.

There's another vision where neighborhoods work through relationships, community trust, and privacy protection. You watch out for your neighbors, but you watch out with your eyes, not with cameras that feed into a searchable database. You know your street because you walk it, not because you can search video from the last week. You trust that crime will be rare because communities with trust usually are safer than communities that only have surveillance.

Neither vision is fully realistic. We'll probably end up with some hybrid. But the balance matters. And right now, the balance is shifting toward "more surveillance because the technology enables it." The leaked Ring email just confirms that's intentional, not accidental.

The question for all of us is whether we want to stop that shift or embrace it. Ring's going to build the infrastructure either way. The only variable is whether we demand constraints.

Key Takeaways From Ring's Surveillance Expansion

Let me put the most important points in one place so they're clear:

-

Search Party was always about more than dogs. The leaked email shows Ring's founder explicitly framed the feature as "foundation" technology for neighborhood crime prevention. That's code for: this is the beginning.

-

Ring already has the technical pieces for person-search. Facial recognition, law enforcement partnerships, AI-powered visual search, crowdsourced network access. The company isn't waiting for permission—it's waiting for the controversy to fade.

-

Consent is illusory. Opt-out defaults mean most people participate without realizing it. Even if you opt out of Search Party, your neighborhood is probably still covered by neighbors who didn't.

-

Amazon is the real player. Ring's parent company has vast resources and significant law enforcement relationships. Don't just think about what Ring wants—think about what Amazon wants with neighborhood surveillance data.

-

This is about infrastructure, not devices. The danger isn't that Ring cameras will be used for surveillance (they already are). The danger is that Ring is building the infrastructure for comprehensive, searchable, law-enforcement-accessible neighborhood surveillance, and doing it before we've decided if we want that.

-

The expansion will probably happen. Unless there's serious regulation or serious public pressure, Ring will eventually expand Search Party to people. It's profitable, it's technically feasible, and it aligns with the company's stated mission.

-

We still have time to set constraints. But not much time. The window for deciding what surveillance infrastructure should be allowed is closing. Once the systems are built and normalized, changing them is much harder.

FAQ

What is Ring's Search Party feature?

Search Party is a crowdsourced video search tool that lets Ring Neighbors app users request help finding lost pets (currently dogs and wildfires). When someone reports a lost dog, nearby Ring camera owners can search through their own and neighbors' shared footage to help locate the pet. The feature uses AI to identify dogs in video footage and surface potential matches to searchers.

How does Ring's Search Party actually work with its AI?

Ring uses computer vision AI models trained to detect dogs in video footage. When a search is initiated, the system notifies nearby Ring users and allows them to browse footage from their own cameras plus voluntarily shared footage from neighbors. The AI automatically flags clips likely to contain dogs, reducing the amount of footage humans need to manually review. The system matches searches to neighborhoods where Ring cameras are concentrated, making it more likely that relevant footage exists.

What did the leaked email from Jamie Siminoff reveal about Ring's plans?

The email, sent in October 2024, stated that Search Party for finding dogs was "the foundation" for "zeroing out crime in neighborhoods." Siminoff wrote that Ring could eventually use this technology to comprehensively prevent crime, suggesting the lost-dog use case was intentionally the first step of a larger expansion plan. The email reveals Ring's leadership views Search Party as infrastructure for broader surveillance capabilities, not just a pet-finding tool.

Why are privacy advocates concerned about Search Party expansion?

Privacy advocates worry that the same technology used to find dogs could be expanded to find people without explicit new consent. Ring already has facial recognition, law enforcement partnerships through its Community Requests feature, and AI-powered visual search capabilities. Critics argue these pieces create infrastructure for comprehensive surveillance that could enable harassment, targeting of protesters, or discriminatory policing. The leaked email confirms expansion is the explicit goal.

What surveillance capabilities does Ring already have besides Search Party?

Ring cameras include facial recognition (turned on by default in some cases), local video search that can identify people and vehicles, integration with the law enforcement Community Requests system, and cloud storage of footage. The company also maintains official relationships with police departments through its law enforcement portal, allowing departments to post official search requests to Neighbors app users.

Can I actually opt out of Search Party without affecting my own cameras?

You can disable Search Party for your own camera, but this only prevents your footage from being shared in searches—it doesn't prevent other neighbors' cameras from surveilling your street. If enough neighbors participate, your neighborhood remains fully monitored regardless of your personal settings. You can't prevent the surveillance network; you can only opt out of contributing to it.

What would Ring need to do to expand Search Party to finding people?

Technically, Ring would need minimal new development. The company already has facial recognition, person-detection AI, law enforcement partnerships, and the crowdsourced search infrastructure. Expanding to people would primarily be a policy decision plus training existing AI models on person-search use cases. The technology exists; the company is choosing not to use it (publicly) yet.

How is Amazon involved in Ring's surveillance expansion?

Amazon owns Ring and has integrated it into its broader smart home and business ecosystem. Amazon benefits from Ring's surveillance data through logistics optimization, market analysis, and understanding of neighborhood patterns. Amazon also owns Rekognition (facial recognition for law enforcement) and AWS services used by police departments, creating aligned interests in expanding surveillance capabilities across multiple products.

What regulatory constraints could limit Ring's Search Party expansion?

Effective constraints could include: purpose limitation (can only search for specified purpose, not expanded uses), temporal limitation (searches expire after set time), opt-in requirements (rather than opt-out defaults), law enforcement limitations (requiring explicit consent rather than default participation in Community Requests), data deletion requirements (footage isn't kept for future searches), and transparency requirements (public announcement of any feature expansion with explicit consent requests). None of these constraints exist at federal level in the US currently.

What's the actual risk if Ring expands Search Party to comprehensive person-search?

Comprehensive person-search infrastructure, especially with law enforcement access, could enable tracking of specific individuals, targeting of protesters or minorities, harassment of disfavored groups, insurance discrimination, and mass surveillance capabilities. Historical examples show surveillance infrastructure built for one purpose (crime prevention) gets repurposed for others (suppressing dissent, monitoring political opponents). The risk isn't necessarily Ring's intentions, but what the infrastructure enables once it exists.

Conclusion: The Surveillance Infrastructure We're Building

Ring's Search Party feature exists at a critical moment in how we're building surveillance infrastructure for American neighborhoods. The leaked email from founder Jamie Siminoff removes any ambiguity about where the company wants to go: comprehensive, AI-powered, law enforcement-accessible neighborhood surveillance disguised as community safety tools.

That's not a paranoid interpretation. That's what "zeroing out crime in neighborhoods" means at scale. That's what building "foundation" technology explicitly designed for eventual person-search means. Ring isn't hiding its ambitions. It's just using warm language (helping find lost dogs) to introduce infrastructure that will eventually serve colder purposes (helping police find suspects).

The company isn't doing anything illegal. The technology works. Enough people are adopting it that Ring has built genuinely comprehensive network coverage in many neighborhoods. Police departments like having access to video footage. And the company's founder genuinely seems to believe that visibility reduces crime.

But good intentions build bad futures when the technology isn't properly constrained. And right now, Search Party has almost no constraints. It's opt-out, not opt-in. It's expanding without explicit new consent. It's integrated with law enforcement. It's owned by a company with massive resources and aligned incentives to expand it further.

The window for setting constraints is still open. Regulators could act. Cities could pass ordinances. Consumer pressure could force Ring to self-limit. But that requires people caring enough to demand it. And so far, people seem to care more about safety (and the feeling of safety from comprehensive surveillance) than about privacy.

If that calculus holds, we're going to end up with neighborhoods where every street is monitored, every person is searchable, and every interaction is recorded. It won't happen suddenly. It'll happen through reasonable-seeming expansions: dogs to people, community searches to law enforcement, voluntary participation to default participation, temporary storage to indefinite storage.

Each step seems small. The accumulated effect is total surveillance.

The question isn't whether Ring will try to build this. The leaked email confirms they will. The question is whether we'll let them. And we're running out of time to decide.

Related Articles

- Ring's Search Party: How Lost Dogs Became a Surveillance Battleground [2025]

- Meta's Facial Recognition Smart Glasses: Privacy, Tech, and What's Coming [2025]

- Meta's Facial Recognition Smart Glasses: What You Need to Know [2025]

- Ring Cancels Flock Deal After Super Bowl Ad Sparks Mass Privacy Outrage [2025]

- Ring's Super Bowl Ad Backlash: The Surveillance Debate [2025]

- Meta's Facial Recognition Smart Glasses: The Privacy Reckoning [2025]

![Ring's AI Search Party: From Lost Dogs to Neighborhood Surveillance [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/ring-s-ai-search-party-from-lost-dogs-to-neighborhood-survei/image-1-1771450727660.jpg)