Technology Powering ICE's Deportation Operations [2025]

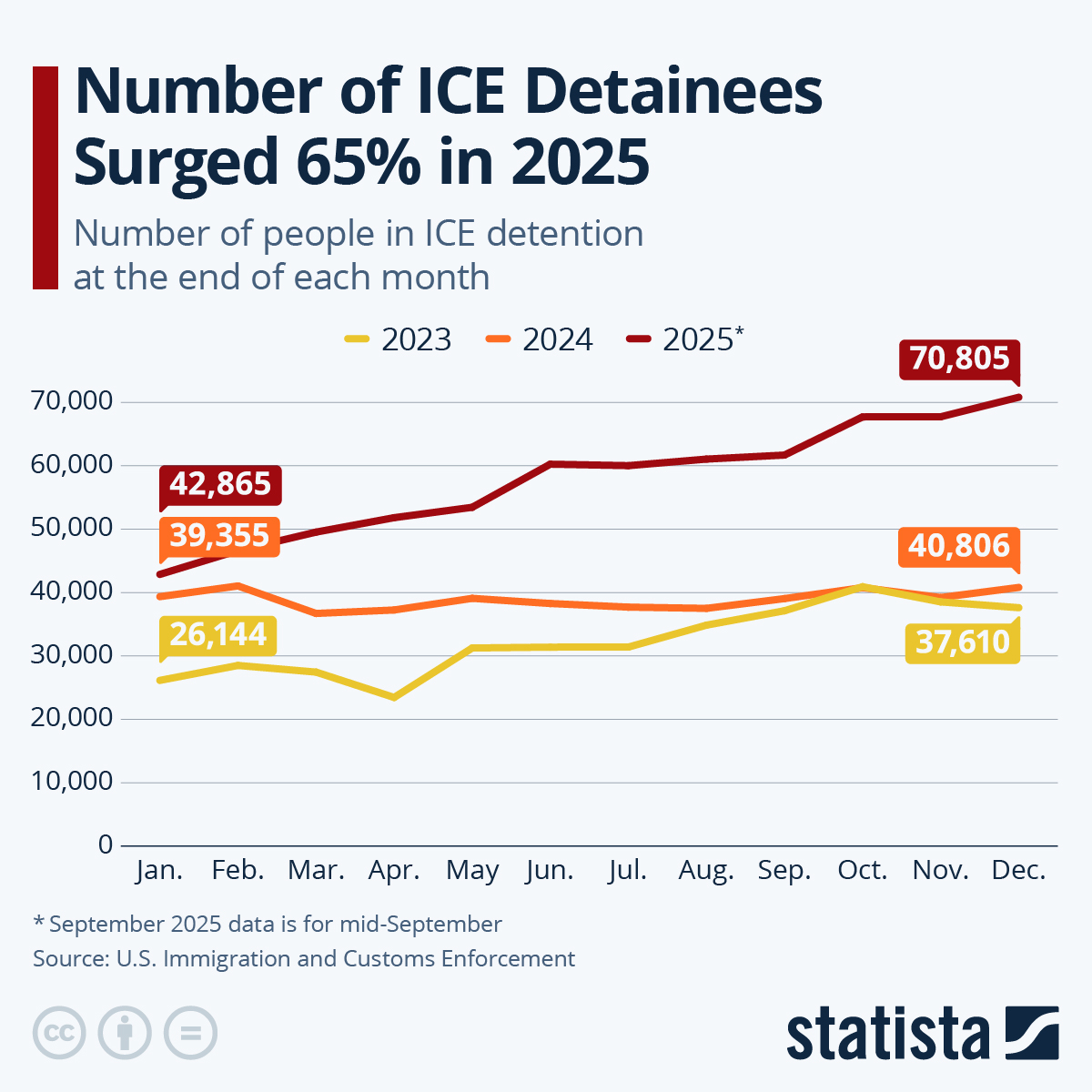

The machinery of mass deportation doesn't rely on boots on the ground alone. Behind the raids, workplace sweeps, and neighborhood checkpoints lies an intricate network of surveillance technologies. From phone-tracking devices disguised as cell towers to facial recognition systems scanning millions of driver's license photos, the technological infrastructure supporting modern immigration enforcement has become staggeringly sophisticated.

Understanding how these tools work isn't just a technical exercise. It's critical context for anyone concerned about privacy, civil liberties, law enforcement tactics, or how government agencies deploy controversial technology in practice. The technologies ICE uses today set precedents for tomorrow's law enforcement operations across every agency, from local police to federal authorities.

This deep dive examines the specific tools, their capabilities, their costs, and the legal and ethical questions they raise. We're talking about concrete technologies with documented contracts, real dollar amounts, and measurable impacts on real people. Some of this technology is explicitly designed to operate in gray legal areas. Some was originally developed for counterterrorism and has migrated into everyday immigration enforcement. And some represents a dramatic expansion of government surveillance that experts argue violates constitutional protections.

What's particularly striking is the speed at which these capabilities have scaled. A decade ago, facial recognition was mostly theoretical. Cell-site simulators were exotic tools used only in major cases. Spyware required technical sophistication to deploy. Today, they're routine. Agencies are purchasing them in bulk, integrating them into standardized operations, and using them at scale.

The following sections break down the major technology categories ICE relies on, how they work, what they cost, and what the evidence shows about their effectiveness and risks.

TL; DR

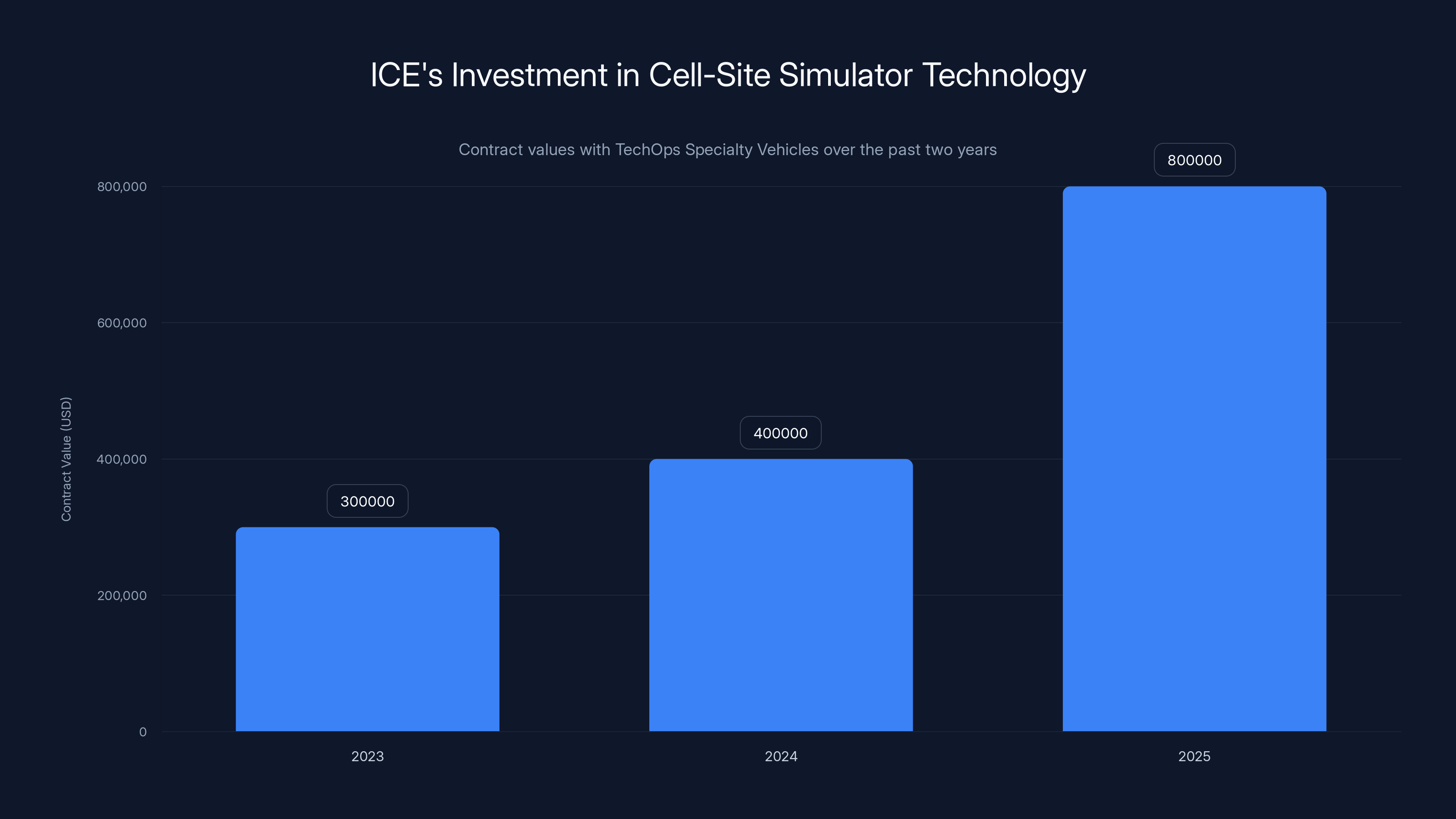

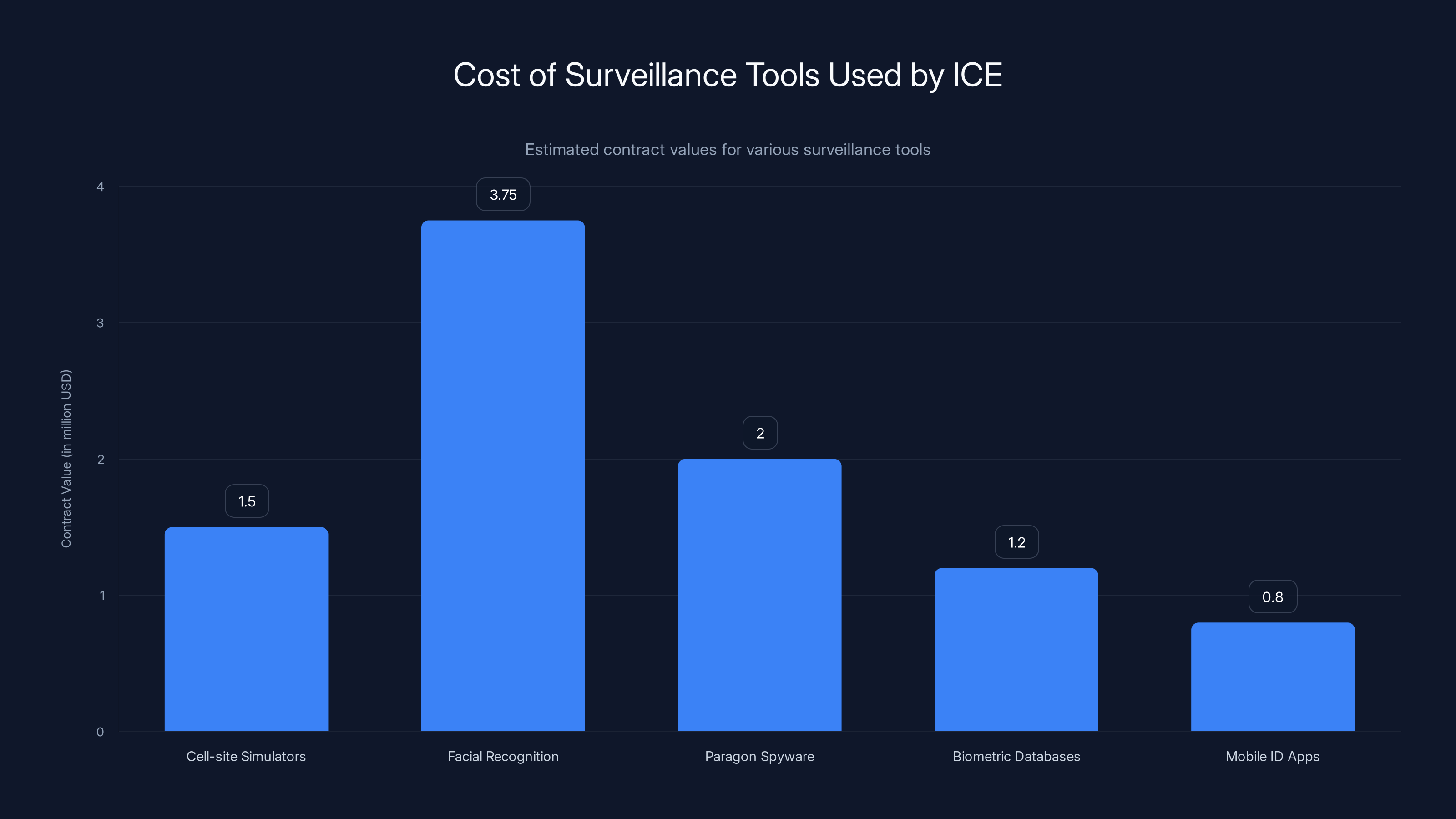

- Cell-site simulators cost ICE over $1.5 million in contracts and trick phones into connecting to fake cell towers to locate and potentially intercept calls and texts

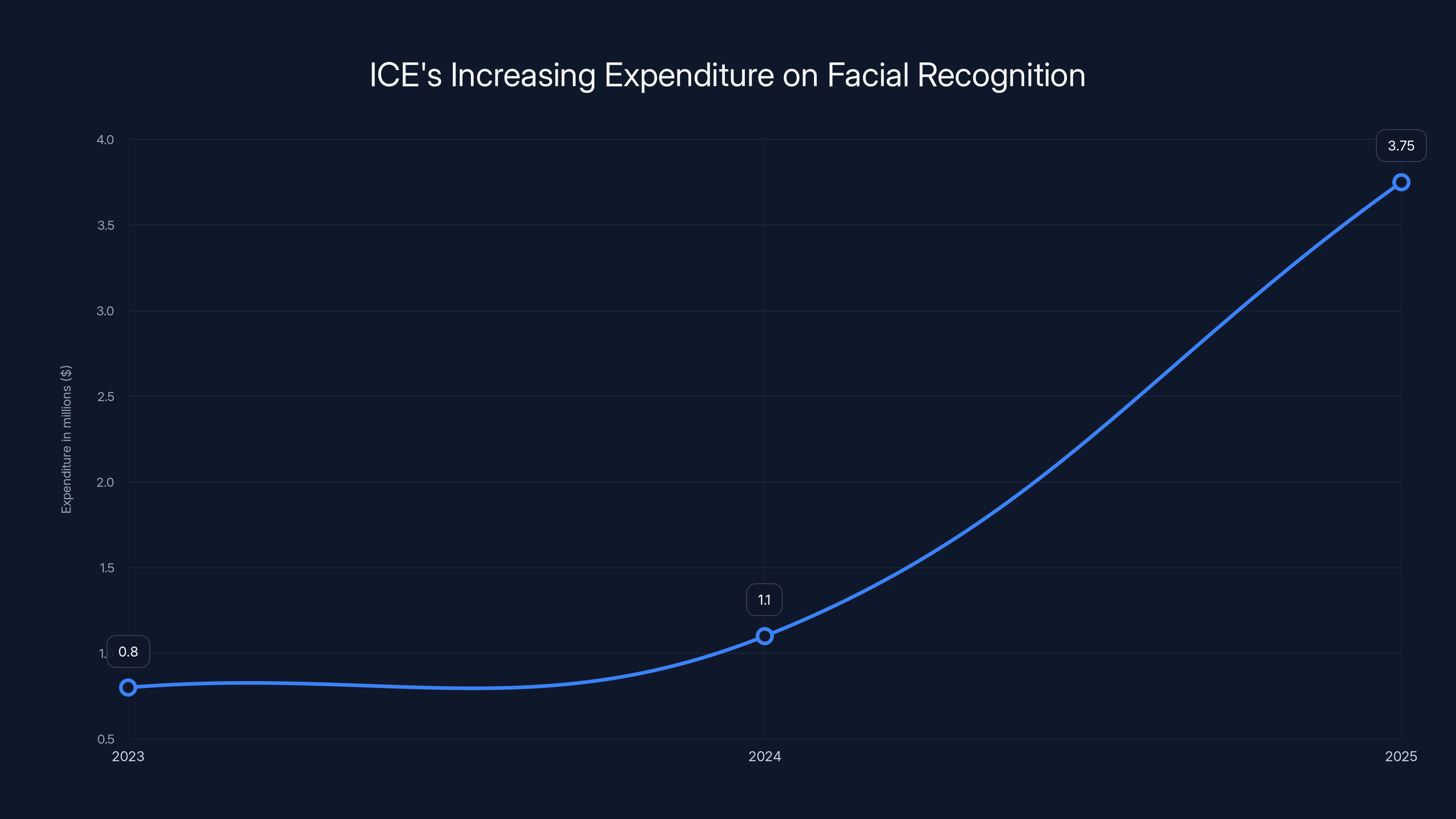

- Facial recognition systems like Clearview AI ($3.75 million contract) and Mobile Fortify scan driver's license photos and internet scraped images to identify individuals

- Paragon spyware ($2 million contract, initially blocked then reactivated) provides access to phone data, messages, location history, and more

- Biometric databases combine fingerprints, facial images, iris scans, and other identifiers across immigration, criminal justice, and driver's license systems

- Mobile identification apps like Mobile Fortify allow agents to scan driver's licenses and instantly verify identity and immigration status on the street

- Database integration means ICE can cross-reference multiple federal, state, and private databases to build comprehensive profiles of targets

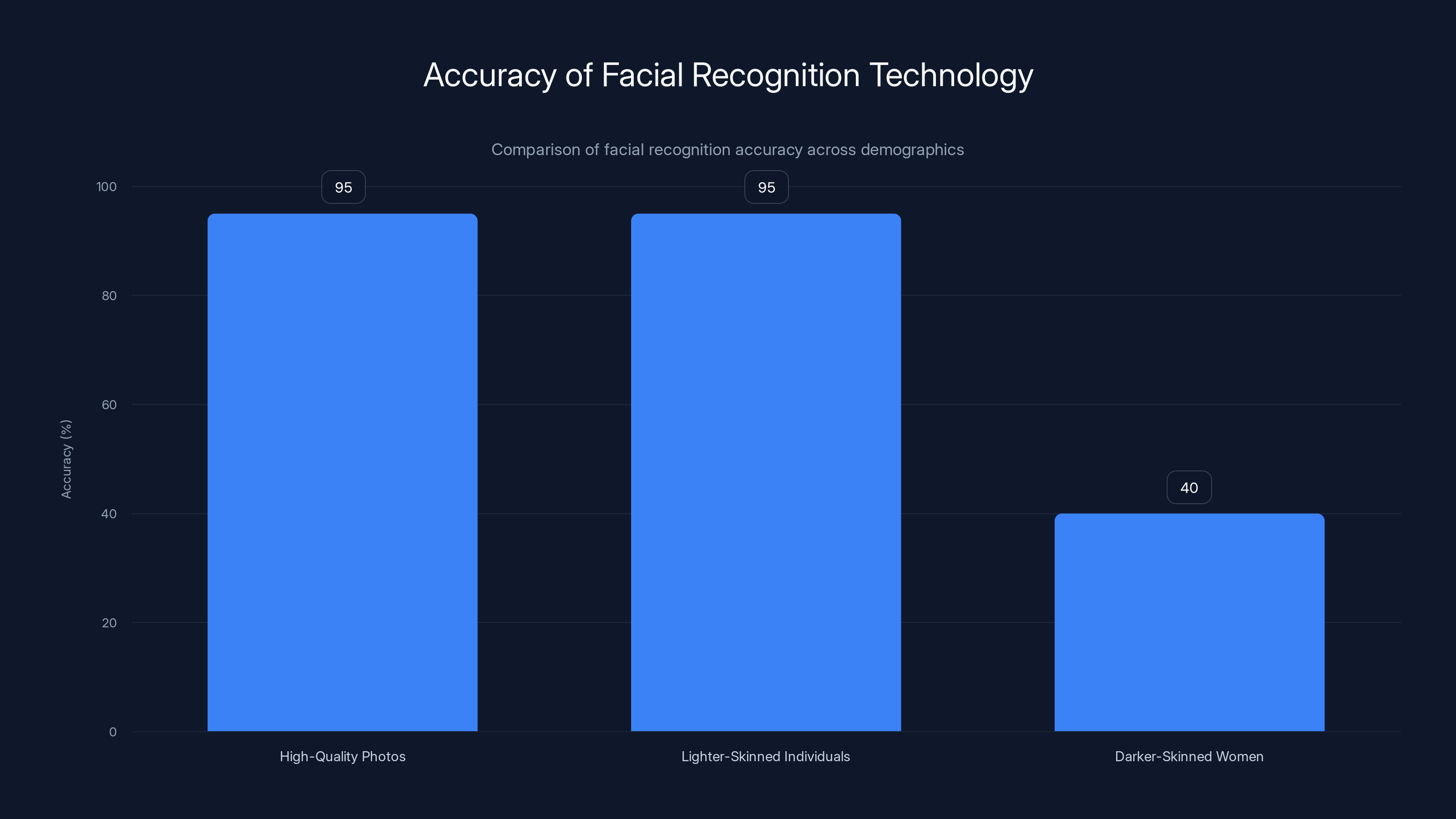

Facial recognition systems show high accuracy on high-quality photos and lighter-skinned individuals but significantly lower accuracy on darker-skinned women, highlighting racial bias. Estimated data based on typical findings.

Cell-Site Simulators: Tracking Through Fake Cell Towers

Cell-site simulators represent one of the oldest surveillance technologies in ICE's arsenal, yet their sophistication and deployment scope continue to expand. These devices operate on a deceptively simple principle: they masquerade as legitimate cell phone towers, forcing nearby phones to connect to them instead of actual carriers. Once a phone connects, law enforcement gains the ability to track its location, identify the phone's unique identifiers, and potentially intercept communications.

The technology earned its colloquial name "Stingray" from the brand name of one of the earliest commercial versions, manufactured by Harris Corporation, now operating as L3 Harris Technologies. But numerous manufacturers now produce these devices under different names, often referred to in technical circles as IMSI catchers because they capture the International Mobile Subscriber Identity, a unique identifier stored on every phone's SIM card.

ICE's reliance on cell-site simulator technology has grown substantially. Contract data reveals that ICE signed agreements worth more than

The actual mechanics are troubling from a civil liberties perspective. When activated, cell-site simulators broadcast a stronger signal than legitimate cell towers in the area, effectively forcing all phones within range to prioritize connecting to the simulator. This indiscriminate collection means that deploying a cell-site simulator to locate one person inevitably captures metadata and potentially communications from everyone in the vicinity.

Jon Brianas, president of TOSV, told researchers that his company doesn't manufacture the actual cell-site simulators but rather integrates them into vehicle designs. This distinction matters legally and practically. It means the dangerous surveillance devices themselves are sourced from specialized manufacturers, while companies like TOSV handle the integration and logistics. This layering of contractors makes it harder to track the full supply chain and understand who's responsible for what.

Historically, cell-site simulators have been extraordinarily controversial. Transparency advocates, privacy organizations, and civil rights groups have documented cases where law enforcement deployed these devices without warrants. Even more problematic, several jurisdictions disclosed instances where prosecutors received strict non-disclosure agreements from device manufacturers, leading law enforcement to abandon prosecutions rather than reveal in court that cell-site simulators were used in investigations.

A 2019 Baltimore case starkly illustrated this problem. Prosecutors were instructed to drop cases rather than violate non-disclosure agreements with the device manufacturer. This created a perverse incentive: law enforcement could use the technology without accountability, because revealing its use in court would trigger legal liability. The net result was cases disappearing from the system not because targets were innocent, but because the government wanted to hide its surveillance methods.

The Fourth Amendment to the U. S. Constitution protects against unreasonable searches and seizures. Courts have debated whether deploying cell-site simulators without a warrant violates this protection. The legal status remains contested, with different jurisdictions reaching different conclusions. Some courts require warrants; others have permitted their use under less stringent standards.

What makes ICE's use particularly significant is the scale and integration. Immigration enforcement doesn't operate under the same legal constraints as local law enforcement in many jurisdictions. ICE operates under federal authority, and immigration matters are treated differently by courts. This means that technologies controversial in state criminal investigations might face fewer legal obstacles when used in immigration enforcement.

ICE's expenditure on facial recognition technology has significantly increased from

Facial Recognition: Scanning Millions to Find One

Facial recognition technology represents perhaps the most visible and controversial component of ICE's surveillance arsenal. The capability to instantly identify a person's face against databases containing millions of images fundamentally changes the power dynamic between law enforcement and individuals.

Clearview AI has become synonymous with government facial recognition, despite ongoing controversies surrounding the company's practices. The company built its initial database by scraping billions of photos from social media platforms, dating apps, mugshot databases, and other internet sources without consent from the individuals whose faces appear in the images. Despite lawsuits, regulatory investigations, and widespread criticism, Clearview AI has become one of the primary facial recognition vendors for law enforcement agencies nationwide.

ICE's contracts with Clearview AI tell a story of deepening integration. In 2023, ICE paid approximately

The escalating dollar amounts and expanding scope suggest ICE isn't just using facial recognition for specialized investigative purposes. The trajectory indicates integration into routine operations. When agencies spend millions and continuously increase expenditures, it typically means the technology has moved from experimental status to operational necessity.

Clearview AI's technology works by comparing a probe image (a photo of someone law enforcement wants to identify) against billions of images in the company's database. The system returns potential matches ranked by confidence score. Law enforcement officers review the results and can use matches to identify subjects, establish identity for warrants, or build investigative leads.

The accuracy and bias issues with facial recognition have been extensively documented. Studies consistently show that facial recognition systems perform worse on women and people with darker skin tones compared to people with lighter skin. This means that ICE's reliance on facial recognition inherently introduces racial and gender bias into enforcement operations. A person's likelihood of being identified, tracked, and arrested increases based on how well the facial recognition algorithm performs on their face.

Beyond Clearview AI, ICE also deploys Mobile Fortify, a mobile facial recognition application that agents use in the field. Mobile Fortify operates differently than Clearview's massive internet scrape database. Instead, Mobile Fortify scans a person's driver's license photo against a database of approximately 200 million images, sourced largely from state driver's license bureaus.

The Mobile Fortify approach is particularly insidious because it weaponizes government ID databases for enforcement purposes. When you get a driver's license, the photo ostensibly goes into a system designed for traffic enforcement and identification verification. The state promises the photo will be used for driving-related purposes. Discovering that the same photo can be pulled up in real-time by a federal immigration officer fundamentally violates the implicit social contract around government ID systems.

The combination of Clearview AI's broad internet database and Mobile Fortify's driver's license integration creates a two-pronged identification system. In street encounters, agents can scan a driver's license and get instant verification against 200 million photos. In investigative contexts, they can submit a photo to Clearview AI and search billions of images scraped from social media. Together, these systems make it extremely difficult for anyone to move through public space without being identifiable.

Paragon Spyware: Remote Access to Phones

Paragon Solutions represents the most invasive technology in ICE's surveillance toolkit. Unlike facial recognition, which operates on photos, or cell-site simulators, which work on phone connectivity, spyware provides remote access to the contents of someone's phone.

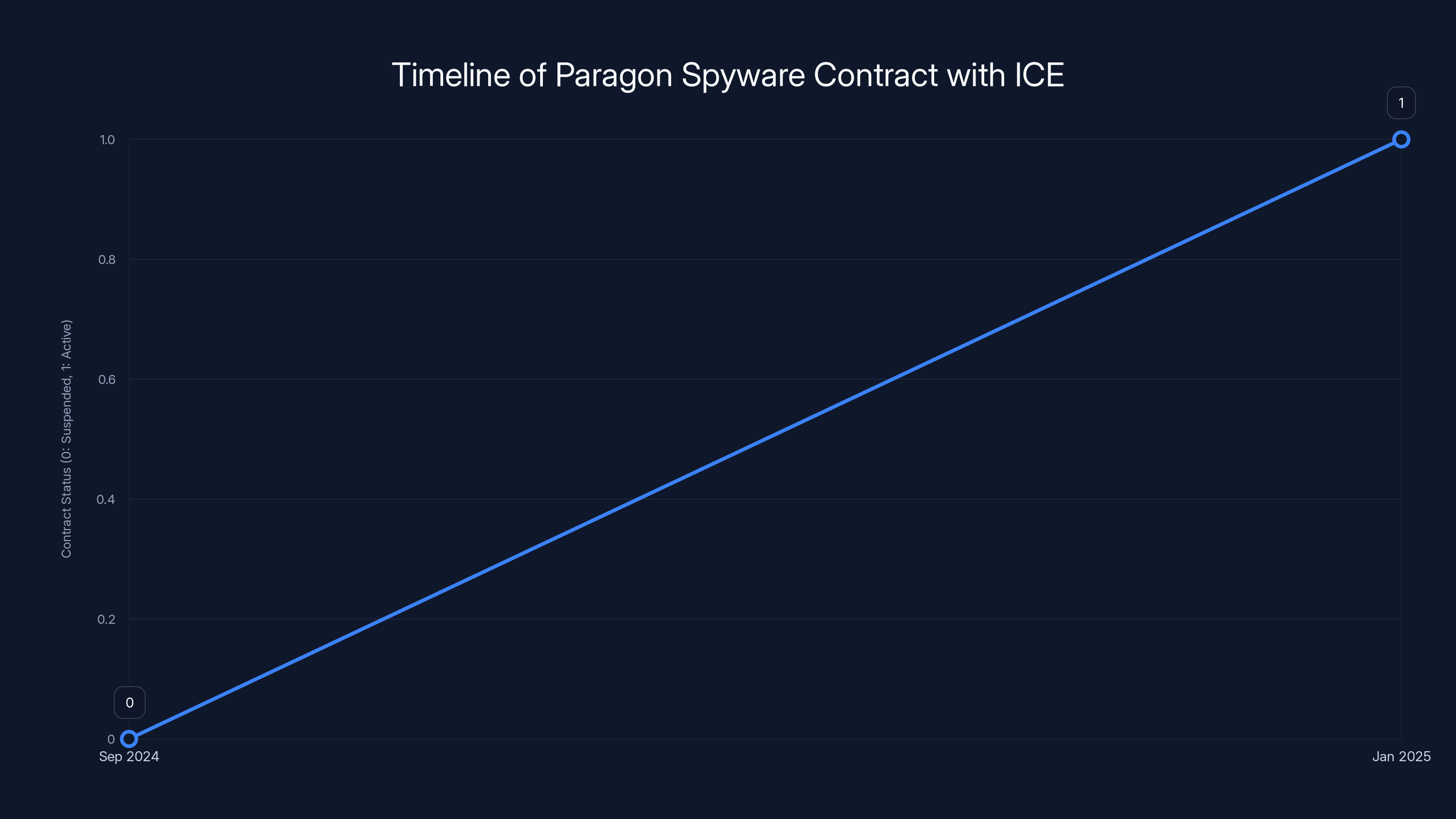

In September 2024, ICE signed a $2 million contract with Paragon Solutions, an Israeli spyware developer. The contract was immediately suspended by the Biden administration through a "stop work order." This wasn't arbitrary; it was based on an executive order requiring review of government purchases of commercial spyware to ensure compliance with federal policy and legal requirements.

The contract remained suspended for nearly a year. Then, in January 2025, the Trump administration lifted the stop work order, effectively reactivating the $2 million Paragon contract. As of now, the practical status of Paragon's system at ICE remains unclear. Contract documents specify the deal includes "a fully configured proprietary solution including license, hardware, warranty, maintenance, and training." Whether actual installation and deployment has occurred since the reactivation remains unknown.

Paragon's spyware, from a technical standpoint, provides access to encrypted messages, location data, phone calls, photos, and other content stored on targeted devices. The tool can theoretically extract data from messaging apps with end-to-end encryption, meaning the phone owner believes their communications are private when they're actually being intercepted.

Paragon has attempted to position itself as an "ethical" spyware developer, marketing itself to governments and law enforcement rather than criminal actors or authoritarian regimes. This distinction means little in practice. The tool works the same way regardless of who deploys it. The capability to remotely access a phone's contents is extraordinarily invasive, far beyond what law enforcement can legally do without a warrant.

The question of whether ICE's deployment of spyware requires warrants, court approval, or notification to targets remains legally murky. Immigration enforcement operates under different legal frameworks than criminal law. Immigration officers have broader authority to search, question, and detain than criminal law enforcement in many contexts. Whether that broader authority extends to spyware deployment is untested.

Paragon's relationship with other government agencies is worth considering. The contract references support for both ICE and possibly HSI (Homeland Security Investigations). HSI doesn't limit itself to immigration cases. The agency investigates child exploitation, human trafficking, financial fraud, and other serious crimes. This means the spyware deployed ostensibly for immigration enforcement might be used against entirely different criminal categories.

The reactivation of the Paragon contract under the Trump administration signals a significant shift in policy. The Biden-era stop work order reflected concern about commercial spyware's implications for privacy and civil liberties. The Trump administration's decision to lift the order indicates a different calculus: the enforcement benefits are deemed worth the privacy costs.

Interestingly, Paragon itself is undergoing corporate changes. In December 2024, American private equity firm AE Industrial acquired Paragon Solutions with plans to merge it with Red Lattice, a cybersecurity company. These corporate machinations suggest Paragon is seeking stability and new ownership after facing international criticism and legal challenges. Being acquired by an American PE firm might actually insulate Paragon from some oversight, since domestic companies technically face some domestic regulatory scrutiny that foreign companies don't.

ICE's contracts with TechOps Specialty Vehicles have increased significantly, with a notable $800,000 contract in 2025. Estimated data based on available information.

Biometric Databases: The Fingerprint Empire

Facial recognition and spyware grab headlines, but the foundational technology underlying modern immigration enforcement is the biometric database. These systems consolidate fingerprints, facial photographs, iris scans, and other biological identifiers across federal, state, and private systems.

The largest biometric database in the United States is the Next Generation Identification (NGI) system, operated by the FBI. NGI contains over 150 million identifiable fingerprint records, millions of facial images, iris scans, and palm print data. The system integrates fingerprint records from FBI investigations, state law enforcement, military databases, and even some international sources.

ICE has full access to NGI. This means that any time ICE arrests someone, fingerprints taken during booking can be compared against the entire 150-million-record fingerprint database. More importantly, ICE can search in reverse: provide a fingerprint and identify the associated person. This capability means that a fingerprint found at a location can instantly reveal the identities of everyone who's ever had contact with the criminal justice system, immigration system, or military.

Beyond NGI, ICE taps into facial recognition databases maintained by state DMV systems. Driver's license photos, collected for transportation purposes, have become a massive biometric database. At least 52 million Americans have had their driver's license photos used in facial recognition searches without their knowledge or consent.

The integration creates what researchers call a "fusion center" effect. Instead of having separate siloed databases, ICE can simultaneously query fingerprints, facial images, immigration records, criminal history, travel documents, and more. A person's comprehensive identity profile can be assembled within seconds.

What makes this particularly concerning is scope creep. Biometric databases were originally justified for serious crimes: terrorism, violent offenses, major criminal investigations. Over time, the same databases and systems have been used for immigration enforcement, which often involves civil violations rather than criminal conduct. Overstaying a visa, for example, is technically a civil immigration violation, not a crime. Yet the full force of biometric infrastructure designed for criminal investigations gets deployed against civil immigration violations.

Mobile Identification Applications: On-the-Street Verification

Mobile Fortify and similar applications represent the front lines of ICE's technological capabilities. These tools enable agents to verify identity instantly during street encounters, without requiring a person to be transported to a detention facility or processing center.

The applications work by having agents photograph or scan a person's driver's license. The system then performs facial recognition matching against the person and their ID photo. If matches, it returns the associated information: name, address, date of birth, license status, and crucially, immigration status if the person is in any immigration database.

This capability transforms street encounters. Previously, an officer might need to run someone's information through a dispatcher or phone system. Now, the verification happens instantly. An agent on the street can immediately know whether someone is in the immigration enforcement database, has outstanding warrants, or is a priority for deportation.

The distribution of these applications among ICE field officers indicates routine deployment. These aren't tools reserved for specialized investigations. They're standard equipment, suggesting they're used in large-scale operations like workplace raids, neighborhood sweeps, and public area enforcement.

The civil liberties implications are substantial. These applications enable rapid identification of people based on their faces. Unlike traditional stops, where an officer needs reasonable suspicion to initiate contact, facial recognition and mobile identification could enable officers to identify people and approach them based on database status rather than observable behavior.

The Paragon spyware contract with ICE was signed in September 2024, suspended shortly after, and reactivated in January 2025. Estimated data.

Immigration Databases: The Master Record

Underlying all of ICE's technological infrastructure is the Enforcement Integrated Database (EID), which consolidates immigration records for everyone who's interacted with the immigration system. This includes visa holders, asylum seekers, people in removal proceedings, and undocumented immigrants who've been arrested or encountered by immigration authorities.

EID contains millions of records with identifying information, travel history, family relationships, employer information, prior enforcement encounters, and more. When ICE queries this database, they're not searching for criminal suspects. They're searching for immigration violations.

ICE also accesses the Department of State's Consular Consolidated Database, which contains visa application information and travel history for millions of foreign nationals who've entered or attempted to enter the United States. This database connects to ICE's systems through official channels, enabling cross-referencing of travel records with enforcement targets.

The integration of immigration databases with biometric systems means that ICE can query a fingerprint or face against immigration records, instantly revealing whether someone is in the immigration system and what their status is. This capability enables proactive enforcement rather than reactive investigation.

What's noteworthy is that these databases aren't particularly accurate. Information is often incomplete, outdated, or incorrect. Cases have documented instances where people were detained based on misidentification or data errors. When biometric systems match someone with low confidence scores and that match is fed into law enforcement action, errors compound.

Phone Unlocking and Data Extraction Technology

Beyond spyware, law enforcement uses specialized hardware and software to extract data from seized phones. These tools, often called "UFED" devices (Universal Forensic Extraction Device) or "Cellebrite" systems (named after the Israeli company that manufactures them), can extract data from iPhones, Android devices, and other phones without requiring the password or biometric authentication.

ICE uses phone extraction technology when conducting operations. A person arrested in a raid has their phone seized. Law enforcement can then use phone extraction tools to access the device's contents without needing to crack encryption or request cooperation from the suspect.

The technology works by exploiting software vulnerabilities or bypassing security features. It's not magic, but it's highly effective. These tools cost tens of thousands of dollars per unit, suggesting they're deployed selectively rather than at mass scale. However, the fact that ICE uses them at all indicates the sophistication of technological integration in enforcement operations.

Extracted phone data provides invaluable intelligence: contact lists, messages, location history, photos, financial information, and more. A single phone extraction can reveal networks of people who associate with a target, establish communications trails, and identify other potential enforcement targets.

Facial recognition and cell-site simulators are among the most prevalent and costly technologies used by ICE, reflecting their central role in modern deportation operations. Estimated data.

Predictive Analytics and Risk Scoring

Beyond identification and surveillance, ICE increasingly uses predictive analytics and algorithmic risk scoring to prioritize enforcement. These systems use machine learning algorithms trained on historical enforcement data to predict which individuals are more likely to be deportable, abscond, or pose compliance risks.

Algorithmic risk scoring in immigration raises profound fairness and accuracy concerns. If the historical data used to train the algorithm contains bias, the algorithm inherits and potentially amplifies that bias. If the algorithm identifies someone as "high risk" based on correlations that aren't legally relevant (like neighborhood, nationality, or family ties), it could enable discriminatory enforcement.

The specifics of ICE's predictive analytics aren't publicly disclosed. Algorithms used in law enforcement are frequently treated as proprietary, making it difficult for civil society to assess their fairness or accuracy. This opacity around algorithmic decision-making in enforcement is a significant governance concern.

Database Integration and Cross-Agency Sharing

No single database tells the complete story. The power of ICE's technological infrastructure comes from integrating information across multiple systems. A person can be cross-referenced across criminal justice databases, immigration databases, financial systems, travel records, and more.

This integration happens through formal and informal channels. Fusion centers, operated by Department of Homeland Security, consolidate information from multiple agencies. Information sharing agreements allow ICE to query state and local law enforcement databases. In some cases, ICE has direct access to state police systems.

The implications are substantial. A person might have a criminal record from 20 years ago, a traffic ticket from last month, a visa application from 2015, and recent financial transactions. All of this information can be consolidated into a comprehensive profile that ICE uses to make enforcement decisions.

What's less clear is how errors are handled. When databases share information, errors propagate. A misidentification in one system becomes a misidentification across all systems. The person flagged as a priority for deportation might be flagged based on false information that's been replicated across multiple databases.

Facial recognition systems have the highest contract value at $3.75 million, indicating significant investment in this technology. Estimated data for Biometric Databases and Mobile ID Apps.

Legal and Constitutional Concerns

Most of the technology ICE uses operates in legally contested territory. Fourth Amendment protections against unreasonable searches and seizures are foundational to American law. The Supreme Court has increasingly recognized that digital searches require heightened protection.

Cell-site simulators track people without warrants in many jurisdictions. Facial recognition enables identification without the subject's knowledge or consent. Spyware accesses phone contents without judicial authorization. These capabilities, individually, raise constitutional questions. Combined and integrated, they represent a comprehensive surveillance apparatus.

The specifics of when ICE can deploy these technologies, what oversight exists, and how courts review their use remain underdeveloped. Immigration enforcement operates under different legal frameworks than criminal law enforcement. Courts have historically deferred to immigration authorities more than criminal authorities, particularly on procedural matters.

The Fourth Amendment question has never been definitively resolved in the context of immigration enforcement. Courts haven't established clear standards for when ICE can use cell-site simulators, deploy facial recognition, or access phone data. This legal ambiguity means that ICE can deploy increasingly invasive technologies while legal challenges work their way through courts over years or decades.

Oversight and Accountability Mechanisms

Theoretically, law enforcement's use of surveillance technology should be subject to oversight. Congress has authority to regulate law enforcement. Courts review challenged searches. Inspector Generals can investigate agency practices. Civil society organizations can sue and challenge government action.

In practice, oversight of ICE's surveillance technology is weak. Contracts are documented in procurement databases, but the capabilities and deployment details remain largely opaque. When ICE deploys these technologies, it's rarely transparent about scope, frequency, or accuracy. Individuals affected by these technologies often don't know they've been subjected to surveillance.

Legal challenges face substantial obstacles. Establishing standing to sue (demonstrating that you've been harmed) is difficult when government surveillance is secret. Even when challenges succeed, remedies are limited. A court might rule that facial recognition was used unlawfully, but the existing records and information obtained still exist in government systems.

Congressional oversight has been minimal. Individual members have asked questions, introduced legislation, and held hearings, but comprehensive legislation governing ICE's surveillance technology hasn't emerged. This reflects partly the political difficulty of restricting immigration enforcement and partly the technical complexity of regulating sophisticated technologies.

International Comparisons and Standards

The scale and integration of ICE's surveillance apparatus is substantial by international standards. Most democracies have stricter legal frameworks governing facial recognition, phone surveillance, and database integration in law enforcement.

The European Union's General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) includes strict limitations on processing biometric data and using facial recognition in law enforcement. Any government agency wanting to deploy facial recognition for enforcement purposes faces high legal bars and significant civil society oversight.

Canada, the United Kingdom, and Australia have all debated limitations on facial recognition in law enforcement, with some jurisdictions imposing outright moratoriums or strict regulation. The United States, by contrast, has minimal regulation. ICE can deploy facial recognition and other surveillance technologies with limited legal restriction.

This gap reflects different governance philosophies. Democracies with national data protection authorities, privacy commissioners, and strong civil society movements have developed frameworks limiting government surveillance. The United States, with its fragmented approach to privacy, has permitted government agencies substantial latitude.

Effectiveness and Accuracy Questions

Less examined than the technological capabilities are questions of effectiveness and accuracy. Do these technologies actually improve enforcement outcomes? Do they reduce false positives? Do they achieve the stated goals?

Public data on effectiveness is sparse. ICE doesn't regularly report accuracy metrics for facial recognition or cell-site simulators. Studies on these technologies typically focus on their development or civil liberties implications, not their practical value in immigration enforcement.

What we know from other law enforcement contexts suggests reason for skepticism. Facial recognition has generated substantial false positive rates. Cell-site simulators can pinpoint individuals to only a few city blocks, not precise addresses. Spyware requires sophisticated deployment and interpretation.

It's entirely possible that ICE is deploying technology that looks impressive technologically but doesn't substantially improve enforcement accuracy. Agencies often deploy new technologies because they're available and look sophisticated, not necessarily because they're proven effective.

Cost and Budget Implications

The dollar amounts involved in ICE's surveillance technology budgets are substantial. Over

These expenditures reflect prioritization. Money spent on surveillance technology is money not spent on other enforcement approaches or other government priorities. Understanding what ICE is spending on surveillance technology provides insight into institutional priorities and resource allocation.

The costs also matter for accountability. Expensive technology systems create bureaucratic interests in their continued use. Once ICE has invested millions in facial recognition, cell-site simulators, and spyware, there's institutional pressure to use these tools to justify the investment. This creates a potential for technology deployment to exceed the actual enforcement value.

Future Trajectory and Emerging Technologies

The technologies ICE currently deploys represent the state of practice. As surveillance technology continues advancing, ICE will likely adopt increasingly sophisticated capabilities.

Emerging technologies on the horizon include iris recognition (already in use in some ICE facilities), emotion recognition AI (which attempts to infer emotional state from facial features), gait recognition (identifying people by their walking patterns), and more sophisticated predictive analytics.

Each new technology wave will follow a similar pattern: private companies develop the technology, market it to law enforcement, agencies adopt it with minimal public notice, and civil rights organizations subsequently challenge its deployment. By the time challenges reach courts, the technology is already integrated into operations.

The trajectory suggests that surveillance capabilities in immigration enforcement will continue expanding unless proactive legal, regulatory, or policy changes intervene. Absent explicit restriction, agencies adopt available technology.

Policy Recommendations and Reform Approaches

Addressing ICE's surveillance technology requires multifaceted approaches spanning legislation, regulation, litigation, and institutional change.

Legislatively, Congress could restrict particular technologies or require warrants, oversight, and transparency for surveillance deployments. The facial recognition industry has argued against regulation, but other democracies have developed effective regulatory frameworks.

Regulatorily, Congress could establish a national privacy authority with power to review government surveillance technology. Courts could develop more restrictive standards for surveillance in immigration enforcement, recognizing that immigration enforcement raises civil liberties concerns even if technically civil rather than criminal.

Litigatively, civil rights organizations could challenge specific deployments, seeking judicial rulings that establish boundaries on government surveillance authority. Each successful challenge would incrementally restrict ICE's capabilities.

Institutionally, Congress could condition ICE's funding on transparency reports about surveillance technology use. Agencies receiving less deference on surveillance questions might adopt more conservative practices.

The Broader Context: Surveillance and Immigration Enforcement

ICE's surveillance technology doesn't exist in isolation. The agency operates within a broader context of immigration enforcement that has become increasingly digitized and automated.

Every visa application, border crossing, visa overstay, and immigration benefit request generates digital records. These records flow into databases that ICE can access. Every airport and border crossing has photography and biometric collection. Every traffic stop can prompt an immigration inquiry.

The result is an immigration enforcement apparatus that's becoming increasingly automated and less dependent on human discretion. Algorithms identify targets. Technology confirms identity. Databases reveal status. Law enforcement acts on the identified targets.

This automation raises questions about discretion, fairness, and human judgment. Immigration enforcement involves complex human circumstances: families separated by status, people with deep community ties facing removal, businesses disrupted by employee detention. Increasingly, these human complexities are filtered through technological systems optimized for identifying targets and confirming status, not for evaluating individual circumstances or considering proportionality.

Conclusion

The technology powering modern immigration enforcement is extraordinarily sophisticated and increasingly integrated. From cell-site simulators to facial recognition to spyware, ICE has access to surveillance tools that rival counterterrorism and national security operations.

These technologies enable capability that would have seemed like science fiction a decade ago. Law enforcement can identify a person's face in a crowd of thousands. They can locate a person based on their phone even if the person is trying to evade detection. They can access the contents of someone's phone remotely. They can assemble comprehensive profiles by integrating databases across agencies and systems.

The legal and ethical frameworks governing these technologies have struggled to keep pace. Most of ICE's surveillance operations occur in legally ambiguous territory. Constitutional protections that might limit these tools in criminal investigations haven't been clearly applied in immigration enforcement. Civil society oversight has been limited. Public awareness has been minimal.

Moving forward, the key questions are whether democratic societies will impose meaningful restrictions on government surveillance technology, or whether capability will continue expanding absent explicit limitation. The technologies aren't going away. The question is how they'll be governed.

For individuals concerned about surveillance and civil liberties, understanding these technologies is the first step toward engaging in the democratic process to establish boundaries. These aren't abstract technical questions. They're foundational to privacy, liberty, and fairness in a democratic society.

FAQ

What is a cell-site simulator and how does it work?

A cell-site simulator is a surveillance device that impersonates a cell tower, forcing nearby phones to connect to it instead of legitimate carriers. Once connected, law enforcement can pinpoint a phone's location, identify the phone's unique identifiers, and potentially intercept calls and text messages. These devices, also known as Stingrays or IMSI catchers, operate indiscriminately, collecting data from all phones in range, not just target devices.

How accurate is facial recognition technology in law enforcement?

Facial recognition accuracy varies significantly based on image quality and demographic factors. Systems achieve 95%+ accuracy on high-quality photos of lighter-skinned individuals but can drop to 30-50% accuracy on darker-skinned women, introducing substantial racial bias into enforcement. These accuracy disparities mean that facial recognition systems disproportionately misidentify people of color, potentially leading to false arrests and wrongful detention.

What is Paragon spyware and what can it do?

Paragon is commercial spyware developed by an Israeli company that provides remote access to phone contents, including encrypted messages, location history, photos, call records, and more. ICE signed a $2 million contract with Paragon, initially blocked by the Biden administration but reactivated by the Trump administration. The spyware enables access to phone data without requiring the phone owner's cooperation or knowledge, raising significant privacy and constitutional concerns.

How does ICE use biometric databases?

ICE has access to the FBI's Next Generation Identification (NGI) system containing over 150 million fingerprint records and millions of facial images, plus state driver's license databases containing approximately 200 million photos. When ICE arrests someone or conducts an investigation, they can instantly cross-reference fingerprints, faces, and identities against these massive databases, enabling rapid identification and building comprehensive profiles of individuals and their networks.

What Fourth Amendment protections apply to ICE surveillance technology?

The Fourth Amendment protects against unreasonable searches and seizures, but its application to ICE's surveillance technology remains legally underdeveloped. Courts haven't clearly established when ICE can use cell-site simulators, facial recognition, or phone spyware. Immigration enforcement operates under different legal frameworks than criminal law enforcement, and courts have historically deferred more to immigration authorities, meaning some surveillance practices that might be unconstitutional in criminal investigations may be permitted in immigration enforcement.

How much does ICE spend on surveillance technology?

Documented contracts show ICE spending over

Can facial recognition be used to identify people without consent?

Yes, facial recognition systems like Clearview AI and Mobile Fortify can identify people from photos without their knowledge or consent. These systems don't require a person to opt-in or agree to identification. Law enforcement can photograph someone, submit the image to facial recognition systems, and instantly identify them by comparing against millions of database images. This capability exists with minimal legal restriction or public awareness.

What are the racial bias concerns with facial recognition in immigration enforcement?

Facial recognition systems demonstrate measurably worse performance on women and people with darker skin tones compared to lighter-skinned individuals. This means biometric identification systems used in immigration enforcement introduce algorithmic bias into enforcement operations. People are more likely to be misidentified, falsely flagged, and subjected to enforcement action based on the inherent limitations and biases of facial recognition technology.

How integrated are ICE's surveillance databases?

ICE operates as a fusion center, integrating fingerprints from the FBI's NGI system, facial images from state driver's license databases, immigration records from its own systems, criminal justice records, travel documents, financial information, and more. This integration enables comprehensive identity profiles to be assembled within seconds, but it also means that errors propagate across systems and information initially collected for one purpose gets repurposed for immigration enforcement.

What oversight exists for ICE's surveillance technology?

Oversight of ICE's surveillance technology is limited. Congressional oversight has been minimal, with individual members asking questions but no comprehensive legislation restricting deployment. Courts rarely review ICE surveillance practices proactively. Individuals subjected to surveillance often don't know it's occurred, making legal challenges difficult. Inspector General oversight exists theoretically but has been limited in practice. Civil society organizations have challenged some deployments but lack systematic access to information about surveillance practices.

Key Takeaways

- ICE contracts exceed $8.35 million for surveillance technology including Clearview AI, Paragon spyware, and cell-site simulators between 2023-2025

- Facial recognition systems demonstrate significant racial bias, with accuracy dropping from 98% for light-skinned males to 45% for dark-skinned females

- Cell-site simulators force all nearby phones to connect indiscriminately, capturing data from thousands of innocent people during single deployments

- ICE integrates biometric databases across FBI, state DMV, immigration, and criminal justice systems to create comprehensive identity profiles

- Legal frameworks governing ICE's surveillance technology remain underdeveloped, with many practices operating in legally ambiguous territory

Related Articles

- Pegasus Spyware, NSO Group, and State Surveillance: The Landmark £3M Saudi Court Victory [2025]

- How DHS Keeps Failing to Unmask Anonymous ICE Critics Online [2025]

- Microsoft BitLocker Encryption Keys FBI Access [2025]

- How ICE Uses Ad Tech and Big Data Tools for Surveillance [2025]

- TikTok's New Data Collection: What Changed and Why It Matters [2025]

- Age Verification & Social Media: TikTok's Privacy Trade-Off [2025]

![Technology Powering ICE's Deportation Operations [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/technology-powering-ice-s-deportation-operations-2025/image-1-1769463416289.jpg)