Introduction: When Companies Become Activists

In October 2024, something unusual happened in Washington, DC. A tech company sent an email blast to thousands of residents asking them to contact their elected officials. Not to vote on a bill. Not to attend a hearing. They were being asked to pressure city leaders into passing regulations that would allow the company to operate its service.

That company was Waymo, the autonomous vehicle division of Alphabet. And the email was basically a permission slip to skip the normal approval process.

This moment reveals something profound about how tech is reshaping governance in America. Companies no longer wait for governments to create rules. They create grassroots pressure campaigns to force the rules they want.

Waymo has been trying to launch driverless robotaxis in DC for over a year. City officials dragged their feet. So Waymo did what Uber did a decade ago with ride-sharing: it went directly to the people.

The company's email told DC residents that Waymo vehicles were "nearly ready" to provide driverless rides. But despite "significant support," District leadership hadn't given approval. Would residents mind sending a pre-written letter to the mayor, the Department of Transportation, and city council members?

Within 90 minutes, 1,500 residents had complied. The campaign worked. But it also exposed a troubling pattern: major tech companies increasingly bypass traditional democratic processes by mobilizing citizens to pressure elected officials on their behalf.

Waymo isn't alone. Uber, Lyft, Bird, and scooter companies used nearly identical tactics to force cities into changing regulations. This playbook is now becoming standard for autonomous vehicle developers.

Understanding Waymo's DC campaign requires looking at three things: why the company needs approval at all, how its lobbying strategy actually works, and what this means for how cities govern technology going forward.

TL; DR

- Waymo launched a grassroots pressure campaign asking DC residents to contact officials after the city refused to approve driverless operations for over a year

- The tactic worked immediately: 1,500 residents contacted leaders within 90 minutes, replicating the playbook that worked for Uber and Lyft nearly a decade ago

- Traditional approval processes are being bypassed as tech companies use citizen mobilization to create political pressure that circumvents regulatory review

- Autonomous vehicle regulation is fragmented across 50 states and hundreds of cities, giving companies leverage to shop for favorable rules

- Congress is considering federal preemption legislation that would override state and local authority, preventing cities from creating their own AV safety standards

- This pattern repeats: mobility disruptors have consistently used grassroots campaigns to force deregulation, then lobbied Congress for federal laws that prevent cities from regulating them

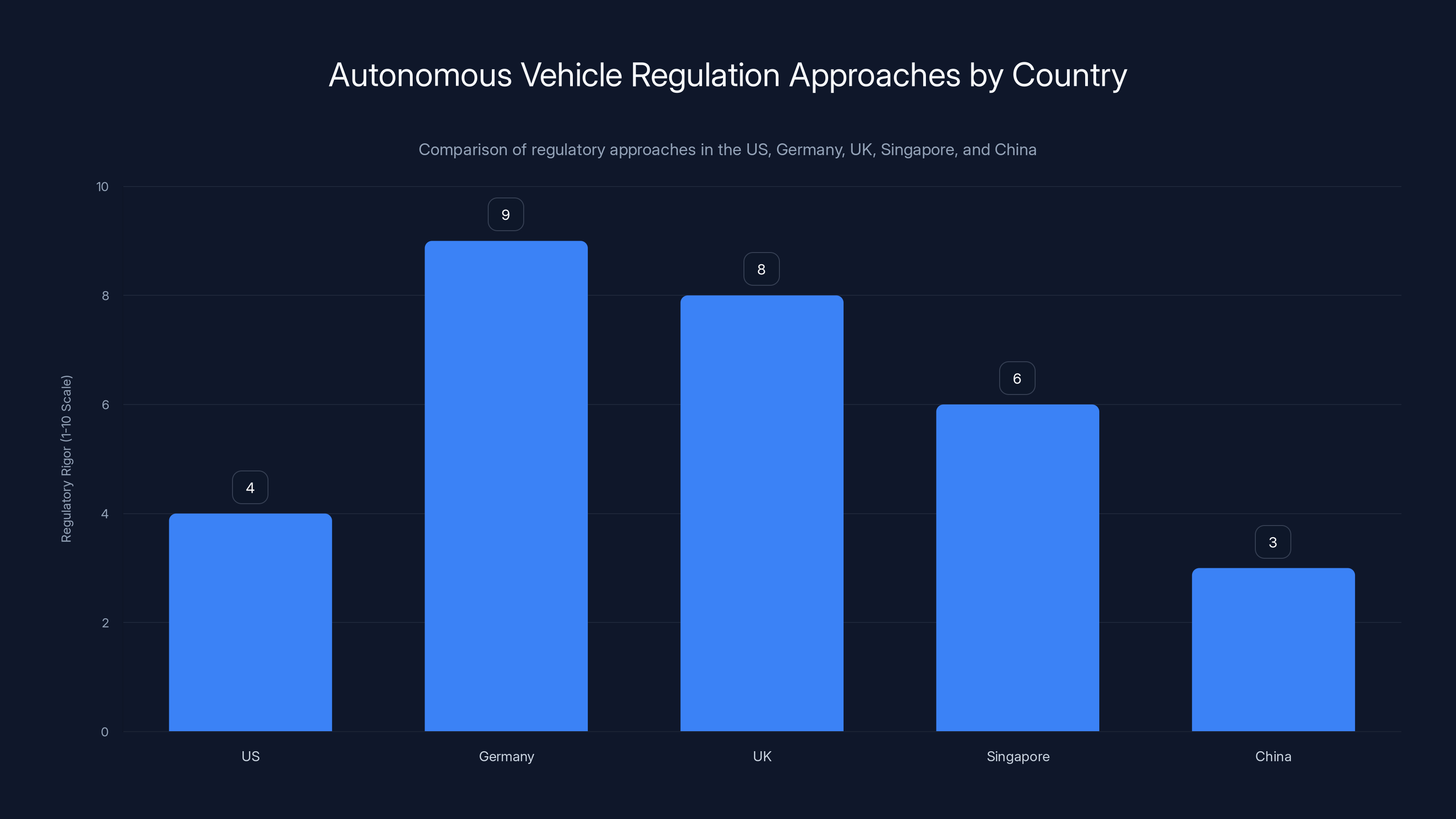

Germany and the UK have the most rigorous autonomous vehicle regulations, prioritizing safety and thorough testing. In contrast, the US and China have more lenient approaches, focusing on faster market entry. (Estimated data)

Why DC Matters: The Regulatory Bottleneck

Waymo's fixation on Washington, DC isn't random. The city represents a test case for penetrating major metropolitan markets where regulations don't yet accommodate autonomous vehicles.

DC's regulatory structure is unique. The city has partial home rule, meaning Congress technically has authority over its budget and some policy areas. The mayor can't unilaterally change traffic laws. The DC Department of Transportation, the mayor's office, and the city council all need to agree. This creates a slower approval process than most US cities.

Waymo has been testing vehicles in DC since 2020. These tests required a human driver behind the wheel. Under current DC law, self-driving cars can operate in testing mode, but not in full driverless mode with paying passengers. That's the regulatory gap Waymo wants to close.

The company has said it would launch driverless service in DC in 2024, then 2025. Neither happened. Not because of technical limitations. Waymo's vehicles work. The problem was pure policy: DC leaders hadn't created rules allowing driverless operations.

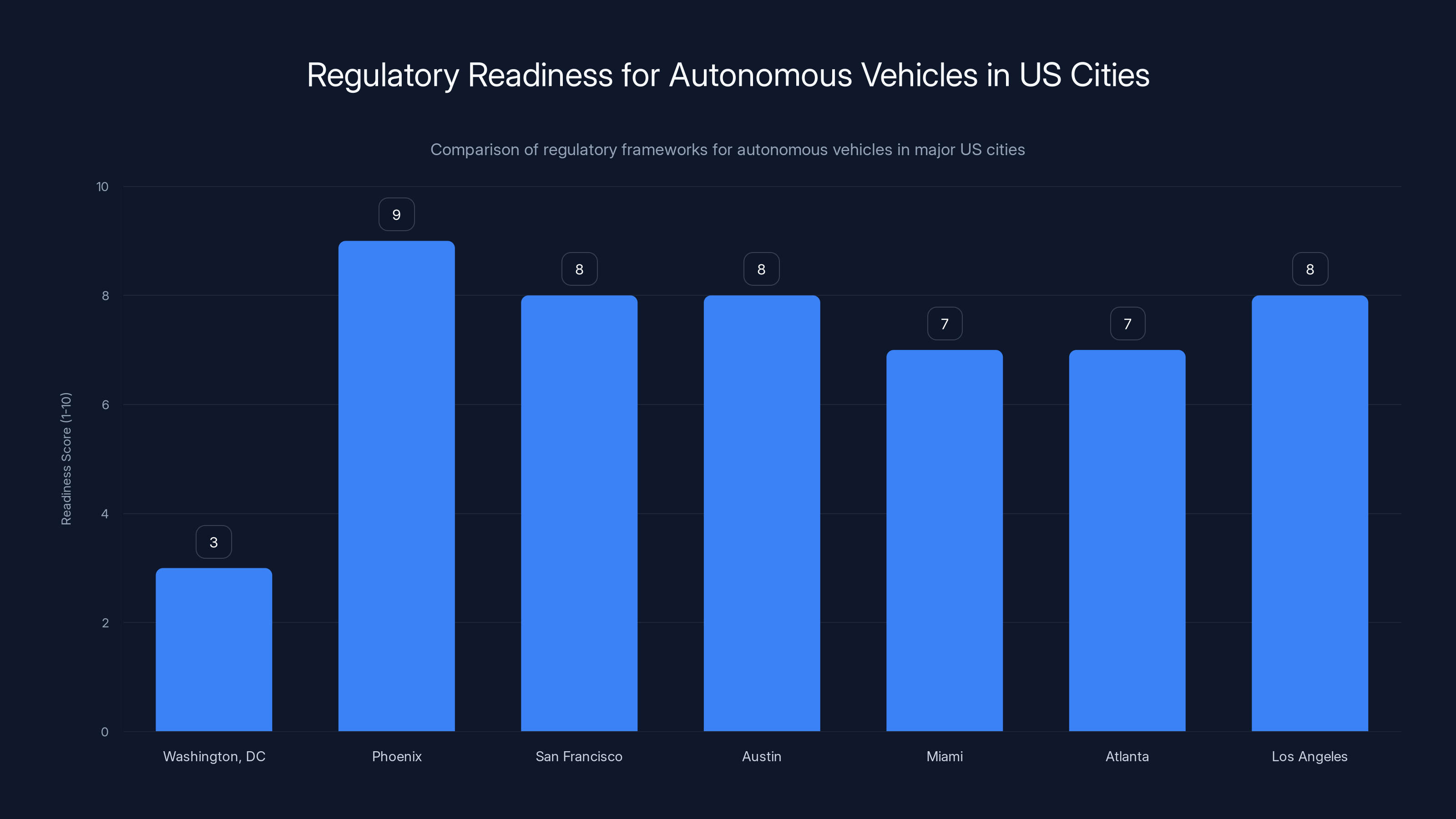

Compare this to other US cities where Waymo operates. In Phoenix, Arizona, Waymo launched driverless service in 2020. Phoenix had already created a regulatory framework welcoming autonomous vehicles. Same with San Francisco, Austin, Miami, Atlanta, and Los Angeles. These cities had written the rules before Waymo arrived.

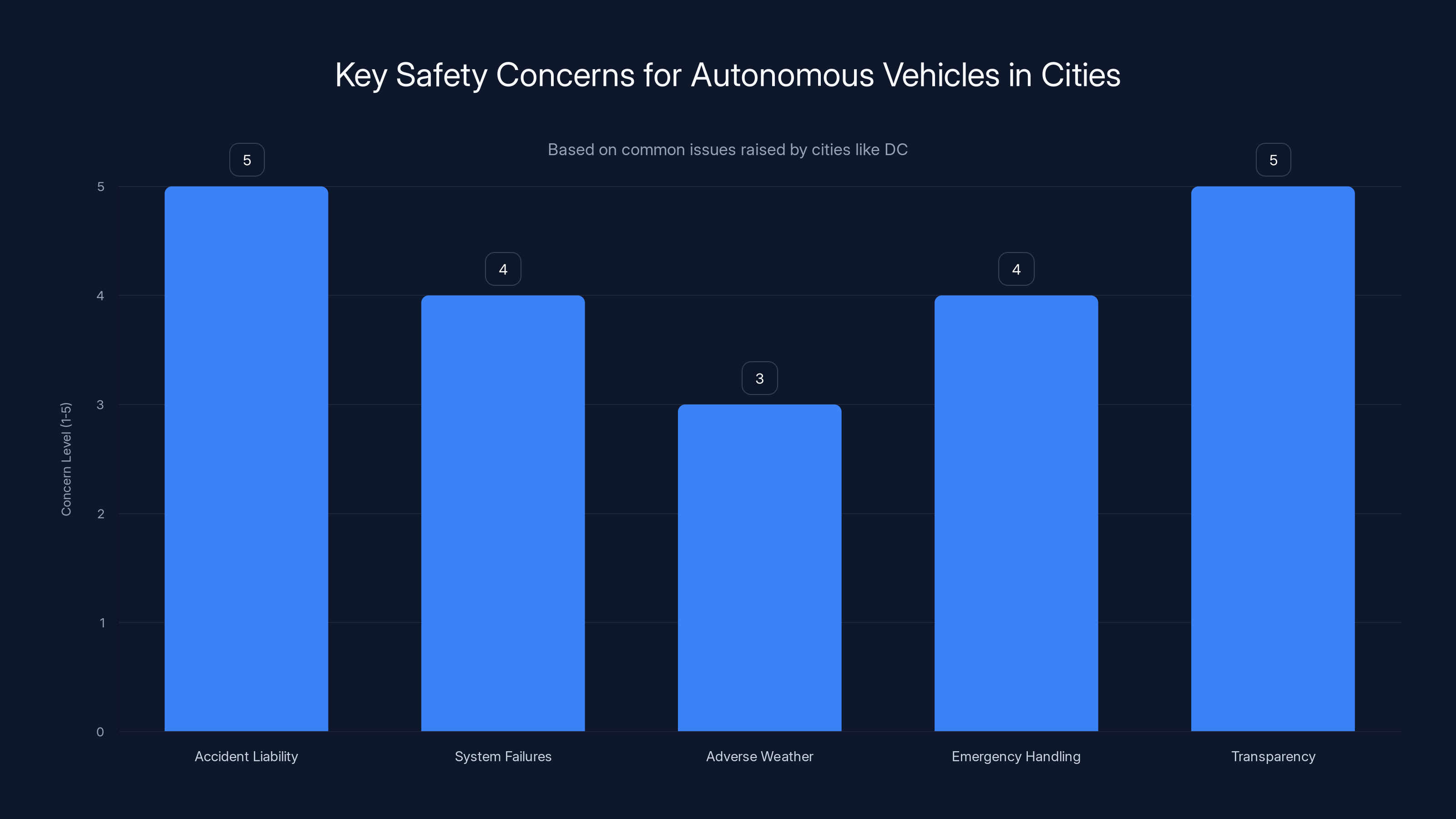

DC's hesitation made sense. Autonomous vehicle safety data was limited. The technology was still maturing. Some council members raised legitimate questions: What happens when a robotaxi gets into an accident? Who's liable? What standards apply? Does DC need its own safety testing?

These were reasonable regulatory concerns. But Waymo didn't want to answer them through normal channels. So it mobilized residents instead.

The Playbook: How Waymo Engineered Citizen Pressure

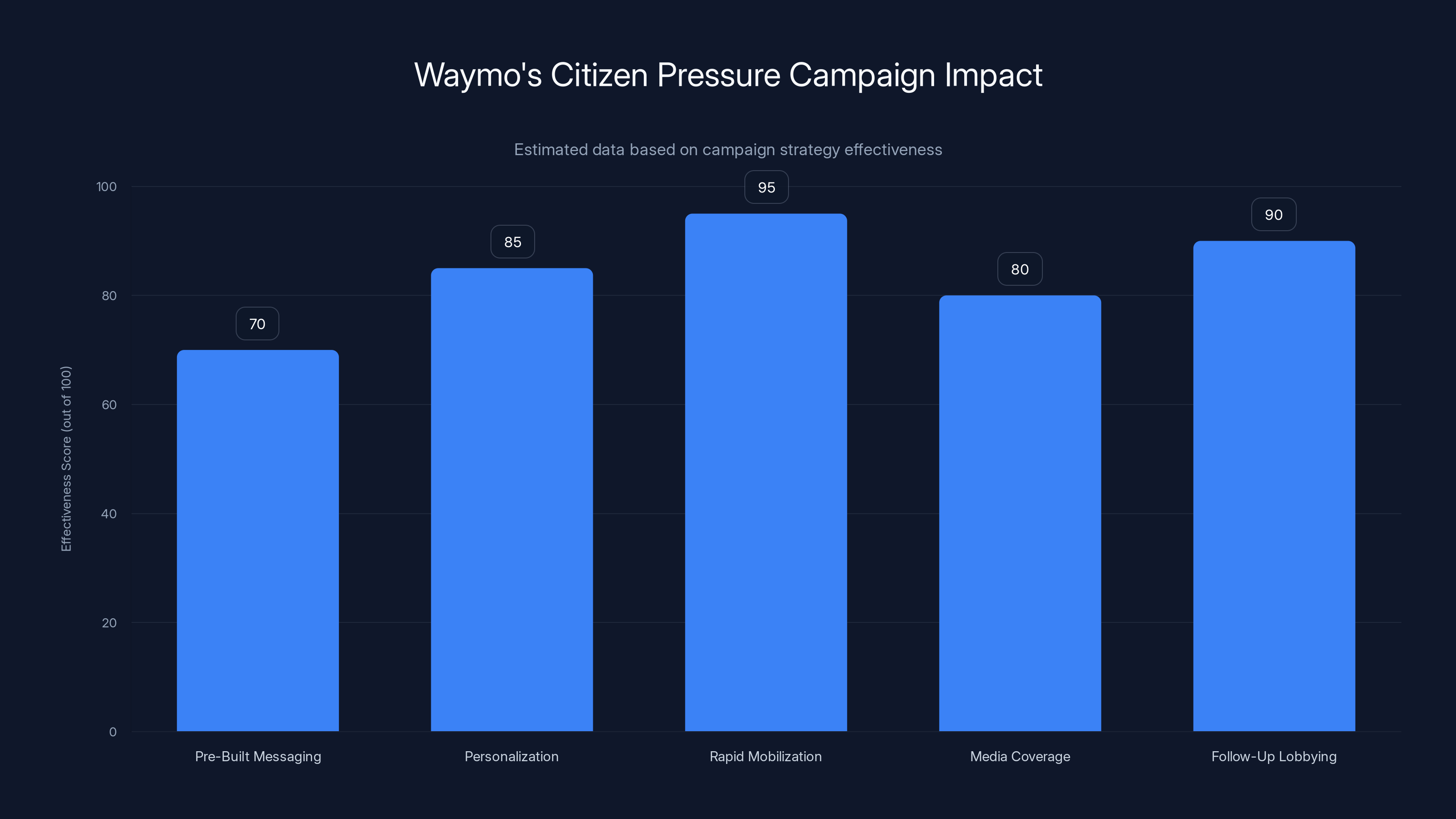

Waymo's email campaign followed a script that worked for Uber and Lyft a decade earlier. Let's break down how it works.

Step 1: Pre-Built Messaging

The email Waymo sent included a pre-written letter for DC residents to send to officials. The letter said things like: "I have observed Waymo vehicles operating throughout our local areas, and I am thrilled about the potential advantages this service could provide, including enhanced accessibility and a decline in traffic-related incidents."

This wording was deliberate. It sounds like personal, grassroots support. But the message was manufactured. Waymo wrote it. Most residents probably just copied and pasted.

Step 2: Personalization Requirement

Waymo's email specifically asked residents to "use your own words." Why? Because form letters have less impact with elected officials. Personalized messages signal genuine public support. By asking residents to add their own thoughts, Waymo could claim these were authentic citizen voices, not corporate messaging.

Step 3: Rapid Mobilization

The speed was critical. Waymo wanted to show overwhelming public support quickly. Getting 1,500 messages to city officials in 90 minutes created a narrative: the public urgently wants this service.

Step 4: Media Coverage

Once reporters learned about the campaign, coverage amplified the message. Headlines said Waymo was "nearly ready" to launch, creating pressure on officials to approve service. The company didn't need everyone in DC to support robotaxis, just enough media attention to make city leaders feel pressure.

Step 5: Follow-Up Lobbying

While residents sent letters, Waymo's lobbyists worked DC's power corridors directly. Mayor Muriel Bowser's office, city council members, and transportation officials all received direct outreach from Waymo representatives.

The grassroots campaign and direct lobbying worked together. Officials felt pressure from below (residents) and persuasion from above (corporate lobbyists). It's a classic squeeze.

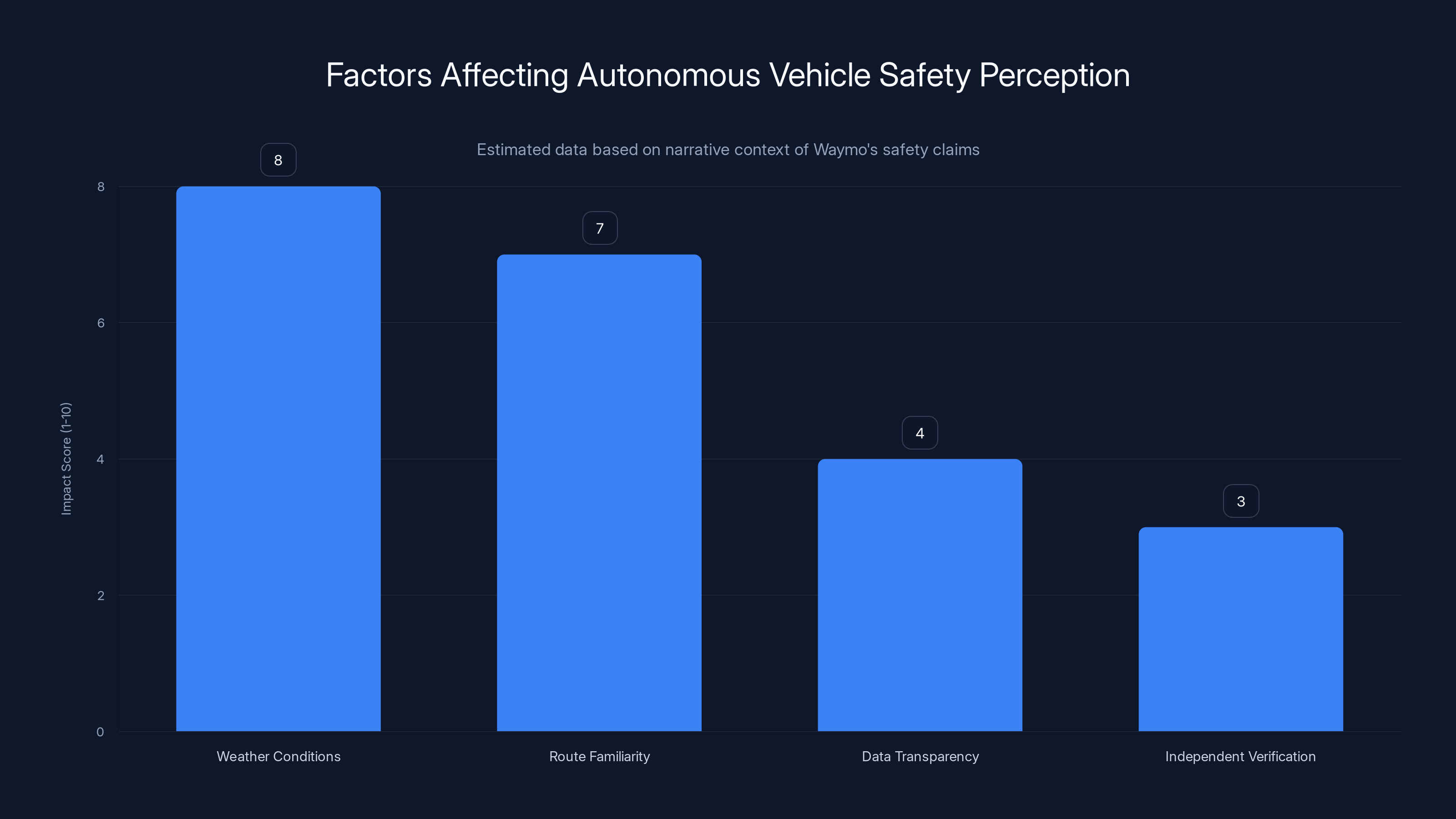

Weather conditions and route familiarity significantly impact the perception of autonomous vehicle safety, while lack of data transparency and independent verification lower confidence. Estimated data.

The Historical Precedent: Learning From Uber

Waymo's campaign isn't original. It's a carbon copy of the Uber playbook from 2014-2016.

When Uber launched in cities like New York, San Francisco, and Austin, local taxi regulations didn't allow it. Ride-sharing was illegal. Cities had medallion systems where a limited number of licensed taxis operated. Adding Uber would undermine that system.

Uber didn't negotiate. It launched anyway, operating in legal gray areas. Then it mobilized users through in-app notifications. When cities threatened to shut Uber down, the app would light up: "Tell your mayor to let us operate." Millions of users sent messages to elected officials.

The strategy worked because it reframed the issue. Uber wasn't a transportation company disrupting taxi medallion holders. It was a consumer service that people loved, being blocked by outdated regulations. By flooding city officials with messages from users, Uber made opposition look like it was against "innovation" and "consumer choice."

Cities eventually surrendered. Most legalized Uber and Lyft, often with minimal safety or labor protections. Then Uber went to state legislatures and lobbied for laws preventing cities from regulating ride-sharing. Those campaigns worked too.

Today, Lyft and Uber operate in nearly every US city with minimal restrictions. This didn't happen because regulation became easier. It happened because tech companies learned to mobilize grassroots pressure faster than cities could build regulatory frameworks.

Waymo is using the same model. But it faces one complication that Uber didn't: safety concerns are more serious. Autonomous vehicles have had accidents. Some were fatal. Public concern about robot cars isn't irrational fear of innovation. It's legitimate worry about untested technology on city streets.

Why Cities Are Hesitant: The Liability Question

DC officials weren't blocking Waymo out of technophobia. They had legitimate concerns.

When a robotaxi gets into an accident, who's responsible? The company? The car owner (if it's a leased vehicle)? Insurance carriers? Passengers? Pedestrians?

Traditional car accident liability is clear. The driver is usually at fault. But with a self-driving car, there's no driver to blame. You can't sue the robot.

DC's hesitation came down to this: does the city have the authority to create liability standards for autonomous vehicles? Or is that a state or federal matter?

This jurisdictional ambiguity is why autonomous vehicle regulation has been so slow. A patchwork of rules applies:

- Federal authorities like the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) can set national standards

- States can create their own AV laws

- Cities can regulate where vehicles operate on city streets

- Insurance companies can decide whether to insure autonomous vehicles

Different cities have taken different approaches. Some required robotaxis to maintain human monitors in vehicles. Some required companies to report accident data. Some created testing periods before full launch.

DC didn't have a framework. Approving Waymo would mean creating one from scratch. That takes time, public input, and expert analysis.

Waymo didn't want to wait. So it went to the public.

The Broader Context: Where Waymo Operates Today

Understanding Waymo's push into DC requires looking at where it already operates and why.

As of 2025, Waymo has launched driverless service in six metropolitan areas:

Phoenix, Arizona: Waymo's largest market. The company has been testing in Phoenix since 2017 and launched driverless service in 2020. Arizona's minimal regulations made this possible. Phoenix saw autonomous vehicles as economic opportunity, not regulatory risk.

San Francisco, California: Waymo launched driverless service here in 2023, though California's regulations require active monitoring and reporting. The company operates in limited geographic areas.

Austin, Texas: Waymo partnered with Uber to offer driverless rides. Texas, like Arizona, has been relatively permissive about autonomous vehicle testing.

Miami, Florida: Waymo launched service in 2023. Florida has been forward-thinking about autonomous vehicle regulation, creating frameworks before companies launched service.

Atlanta, Georgia: Waymo announced service expansion here in 2024. Georgia created regulatory pathways for autonomous vehicles.

San Francisco Bay Area (broader region): Waymo operates across multiple Bay Area cities with varying regulatory structures.

Notice a pattern? Most of these places already had regulatory frameworks in place before Waymo launched. The company didn't fight for approval in these cities. It moved to them because the approval process was already clear.

DC represents a different challenge. The city had no established autonomous vehicle framework. Waymo could either work with regulators to create one, or skip that process and pressure officials instead.

It chose the latter.

Phoenix and other cities have established regulatory frameworks for autonomous vehicles, scoring higher in readiness compared to Washington, DC. Estimated data based on regulatory progress.

The Federal Preemption Play: Congress Gets Involved

Waymo's DC campaign isn't just about DC. It's part of a larger strategy to reshape how autonomous vehicles are regulated nationally.

While Waymo was pressuring DC, Congress was considering legislation that would supersede city and state authority over autonomous vehicles. The bill, called the Autonomous Vehicle Innovation Act, would:

- Prevent states from banning autonomous vehicles

- Stop states from requiring companies to report crash data

- Block states from requiring human backup drivers

- Override city regulations that restrict where autonomous vehicles can operate

In other words, the bill would make it impossible for DC, or any city, to restrict Waymo's operations once federal rules were in place.

This is the endgame. Waymo doesn't just want DC to approve service. It wants Congress to prevent DC from ever restricting it again.

The House advanced this bill in 2024. If it passes, cities lose regulatory authority over autonomous vehicles. That authority moves to federal agencies like NHTSA, which have been notoriously slow at creating autonomous vehicle standards.

This is the same pattern that played out with ride-sharing. Uber and Lyft pushed for state preemption laws that prevented cities from regulating driver classification, pay, or benefits. Those laws passed. Now cities can't require gig drivers to be classified as employees, even if they wanted to.

Autonomous vehicle preemption would work the same way. Cities would lose authority. Federal regulators would control policy. And federal regulators are generally weaker than city regulators because they face more corporate lobbying and political pressure.

The Safety Question: What Data Actually Exists?

Waymo's marketing emphasizes that its vehicles are safer than human drivers. The company claims extensive real-world testing and accident data. But the actual evidence is murkier than the company's claims.

Here's what we know:

Waymo's Accident Record: Waymo has reported some accidents, but the company hasn't published comprehensive safety data. A few high-profile incidents have occurred: collisions with cyclists, accidents at intersections, and instances where the vehicle couldn't handle unexpected situations.

Limited Comparison Data: Comparing autonomous vehicles to human drivers is harder than it sounds. You can't just count accidents. You need to control for road conditions, trip purpose, geography, and time of day. Waymo's vehicles mostly operate in favorable conditions: sunny places like Phoenix, mostly on known routes.

Bias in Testing: Waymo tests in areas with good weather and clear roads. Human drivers operate in rain, snow, construction zones, and complex urban environments everywhere. The comparison isn't fair.

Missing Data: Waymo doesn't publish detailed accident reports. Independent safety researchers have limited access to real data. Most claims about safety come from the company itself.

DC officials knew this. That's partly why they hesitated to approve service. The city wanted more transparent safety data before allowing driverless operations.

Waymo's citizen pressure campaign circumvented that legitimate regulatory concern.

How Other Companies Are Doing This

Waymo isn't the only autonomous vehicle company pushing regulations. Others are using similar tactics.

Cruise (formerly Cruise Automation): Cruise, owned by General Motors, operated in San Francisco with minimal oversight. The company faced criticism after a robotaxi collided with a fire truck. Even after that incident, the company continued lobbying for fewer restrictions.

Zoox (owned by Amazon): Zoox has permits to test autonomous vehicles in DC, like Waymo. The company is also pushing for regulatory approval to launch commercial service.

Nuro: Nuro, which focuses on autonomous delivery, has obtained special federal exemptions allowing it to test small self-driving vehicles on public roads. The company is expanding rapidly, partly because it's focused on delivery, not passenger transportation, which faces different regulations.

Tesla: While Tesla doesn't explicitly operate robotaxis, the company is developing "Full Self-Driving" capabilities. Tesla has been pushing regulators in multiple states to allow expanded testing of autonomous features. The company's approach is more aggressive, sometimes operating in legal gray areas while asking for regulatory clarification after the fact.

All these companies face the same problem: regulations lag behind technology. Their solution is consistent: pressure regulators into approval rather than work through normal processes.

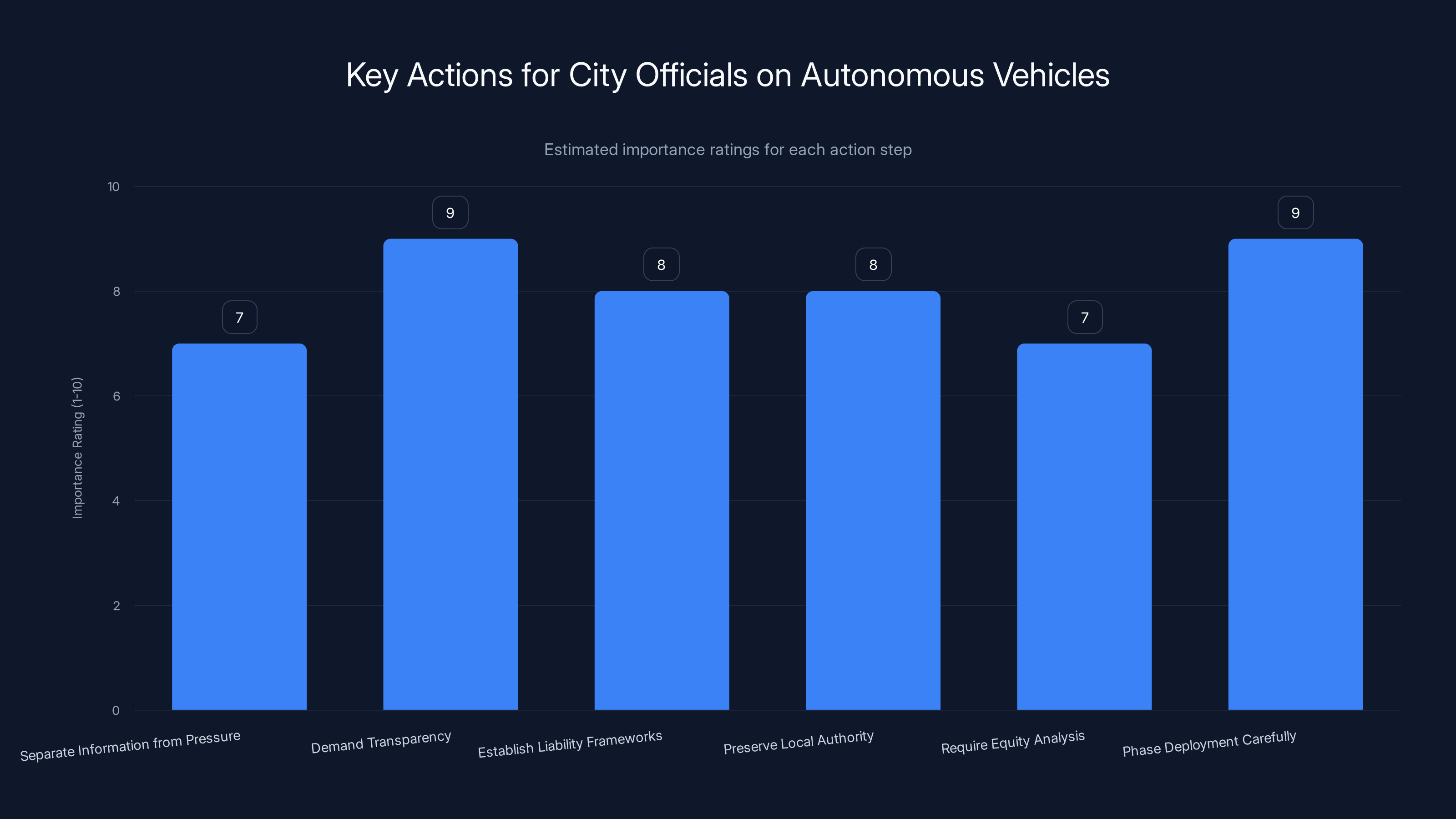

City officials should prioritize demanding transparency and phasing deployment carefully, both rated at 9, to effectively manage autonomous vehicle integration. (Estimated data)

The Citizen Pressure Model: Why It Works

Waymo's DC campaign succeeded because grassroots pressure is more politically potent than expert analysis or safety concerns.

Here's why the model works:

Elected officials care about public opinion: Mayors and city council members need to get reelected. When constituents contact them, it influences their thinking. 1,500 messages from residents saying "I want robotaxis" is politically significant. It's harder to ignore than expert testimony about liability standards.

Media loves the narrative: When a company mobilizes residents, it's newsworthy. Journalists cover it as a populist uprising. The story becomes "DC residents push officials to approve Waymo service" rather than "Company bypasses regulatory process." This shifts the narrative in Waymo's favor.

Opposition becomes visible: Once residents start contacting officials, opponents have to organize their own grassroots response. But many citizens are neutral about autonomous vehicles. Waymo's early mobilization sets the tone. By the time skeptics organize, Waymo already has political momentum.

Officials face accountability pressure: If a city council member opposes a service that residents want, they risk being painted as blocking innovation. Even if the official has legitimate safety concerns, the political pressure makes taking a stand harder.

The company controls the narrative: Waymo gets to define the terms. The message is "enhanced accessibility" and "decline in traffic-related incidents." Residents don't hear about safety concerns or liability questions. They hear about benefits.

This is why the citizen pressure model is so effective. It's not lying, exactly. It's selective truth-telling with political pressure.

Why Cities Can't Just Say No

You might think DC could simply refuse to approve Waymo. The city could say "no autonomous vehicles until we have safety standards." Why didn't that happen?

Political risk plays a role. Once residents contact city officials expressing support for a service, opposition becomes risky. The official who blocks it faces being labeled anti-innovation.

But there's a deeper reason: Waymo controls the approval timeline.

The company can keep testing legally. It can keep lobbying. It can keep mobilizing citizens. DC officials face constant pressure without an obvious resolution. Eventually, many find it easier to approve service than to keep fighting.

This is the asymmetry of the situation. Waymo has infinite resources and time. DC officials have limited political capital. Eventually, the company wins.

Moreover, cities fear regulatory arbitrage. If DC refuses Waymo, the company moves to another city that approves it. That city gets jobs, tax revenue, and prestige as a "tech-forward" place. DC gets labeled as anti-innovation. In competition between cities for corporate investment, that's a powerful incentive to capitulate.

This is especially true in DC, where economic development is a constant concern. If officials can show they're friendly to tech companies, that attracts other investments too.

The Broader Implications: Democracy as a Service

Waymo's DC campaign reveals something troubling about how regulation works in modern America: democracy is becoming a service that companies can buy.

The model is simple:

- Company wants regulatory approval

- Company mobilizes citizens through targeted messaging

- Citizens contact elected officials

- Officials feel pressure and approve service

- Company gets what it wanted

At no point are there genuine public deliberation, transparent debate, or expert analysis. There's just corporate-engineered pressure masquerading as grassroots support.

This works because most people don't pay attention to transportation regulation. They care about getting good deals on services. If Waymo says robotaxis are coming and they want help, many people say yes. Few stop to ask whether they really have the information needed to support the policy.

The problem deepens when you consider that Waymo controls the information citizens receive. The company gets to frame the question. It gets to emphasize benefits and downplay risks. Citizens making "grassroots" arguments are repeating talking points written by corporate communications teams.

This isn't democracy. It's astroturf: fake grassroots movements created by corporations.

Cities like DC have high concern levels about accident liability and transparency in autonomous vehicle operations, highlighting the need for clear regulatory frameworks. Estimated data.

What Regulators Should Require Instead

If cities want to avoid being manipulated by corporate pressure campaigns, they need different approaches.

Transparency Requirements: Cities should require companies seeking approval to publish all accident data, near-miss incidents, and performance metrics. This data should be available to researchers and the public, not just regulators.

Independent Audits: Before approving autonomous vehicle service, cities should require independent safety audits by engineers who don't work for the company. These audits should be public.

Liability Frameworks: Cities should establish clear liability rules before approving service. If a robotaxi hits a pedestrian, who pays? This needs to be decided through deliberation, not assumed after launch.

Gradual Expansion: Instead of approving unlimited operations, cities should require phased launches. Start in limited areas, under human monitoring, with frequent review checkpoints.

Public Input Periods: Cities should conduct formal public comment periods before approving autonomous vehicle service. Not in response to corporate-mobilized citizens, but as part of intentional regulatory deliberation.

Equity Analysis: Cities should consider who benefits from autonomous vehicles and who bears the risks. Do low-income residents get cheaper transportation, or do they just lose jobs as human drivers are replaced?

None of this requires banning autonomous vehicles. It just requires making approval decisions through transparent, deliberate processes instead of responding to corporate pressure.

International Comparisons: How Other Countries Do This

The US isn't the only place grappling with autonomous vehicle regulation. Other countries have taken different approaches.

Germany: German regulators created detailed safety standards for autonomous vehicles before allowing widespread testing. The standards specify what sensors vehicles must have, how they should handle emergency situations, and what insurance coverage is required. Companies must meet these standards before launching service. It's slower than the US approach, but more rigorous.

UK: British regulators created a regulatory sandbox specifically for autonomous vehicles. Companies can test in designated areas under close oversight. The government collects performance data, which informs future regulations. Testing is monitored, not self-reported.

Singapore: Singapore approved autonomous vehicle testing, but only in controlled environments like closed parks and industrial zones. The city-state is evaluating the technology carefully before allowing public road testing.

China: China is pursuing autonomous vehicles aggressively, with minimal public oversight. Companies operate in cities with limited regulatory restrictions. But this has led to safety incidents and public backlash.

The contrast is stark. Germany and the UK emphasize thorough testing before approval. The US emphasizes market entry with minimal requirements. Germany's approach is slower, but produces more robust regulations. The US approach is faster, but regulators are constantly playing catch-up.

Waymo's DC campaign is happening in the US because the US regulatory system is weaker and more fragmented. In Germany, a company couldn't mobilize citizens to force approval. The regulatory framework is too strong.

The Future: Federal Preemption and What Comes Next

Waymo's immediate goal is DC approval. But its longer-term strategy is federal preemption legislation that removes cities from autonomous vehicle regulation entirely.

If that legislation passes, DC and every other city loses authority to regulate where autonomous vehicles operate, how many can be on roads, or what safety standards they must meet. Federal agencies like NHTSA take over.

This would represent a massive shift in regulatory authority. Cities have controlled transportation policy for over a century. That's about to change.

Federal preemption is industry strategy, not accident. Tesla, Waymo, and other autonomous vehicle companies have organized to push for it. Lobbyists are working Congress actively.

The legislation would likely pass because:

- Autonomous vehicle companies are well-funded and politically connected

- Congress generally favors federal preemption (it's easier than negotiating with 50 states)

- There's bipartisan support (both parties want to be seen as pro-innovation)

- Cities lack the lobbying power to fight it effectively

Once it passes, the game changes. Cities can't slow autonomous vehicle deployment. They can't require human backup drivers. They can't demand transparency about accidents. Federal regulators would control those decisions.

Historically, federal regulators set weaker standards than cities do. This could lead to faster autonomous vehicle deployment, but less public safety oversight.

Waymo's campaign effectively used rapid mobilization and follow-up lobbying to create significant pressure, with rapid mobilization scoring the highest in effectiveness. Estimated data.

The Gig Economy Parallel: What Happened With Ride-Sharing

Autonomous vehicles are following the exact path ride-sharing took, and it's worth understanding that history because it predicts the future.

When Uber launched, cities wanted to regulate it. They wanted driver protections, passenger protections, and tax compliance. Uber said no—regulations would stifle innovation.

Uber organized users to contact city officials. It lobbied aggressively. It operated in legal gray areas while fighting regulation.

Eventually, cities gave up. Uber and Lyft are now operating in most US cities with minimal protection for drivers. There are no mandated benefits, no requirement for driver training, and no guarantee of minimum earnings.

Then Uber lobbied state legislatures for preemption laws. California's Proposition 22 passed in 2020, removing the ability to classify gig workers as employees. Other states followed.

Today, the gig economy operates with fewer protections than traditional employment. This happened not through deliberate policy choice, but through corporate mobilization and regulatory circumvention.

Autonomous vehicles are following the same trajectory. First, companies pressure cities for approval. Then they push for state and federal preemption laws that remove regulatory authority. The result is rapid deployment with minimal oversight.

Waymo's DC campaign is step one of that process.

What Would Real Regulation Look Like?

Implicitly, Waymo and other autonomous vehicle companies argue that regulation should get out of the way. But regulation isn't inherently bad. The question is whether regulation is designed well.

Good autonomous vehicle regulation would:

Separate testing from commercial service: Companies can test vehicles under controlled conditions, with close monitoring. But commercial service (paying customers) requires different rules. Testing is about learning. Commercial service is about revenue.

Require transparent safety data: Companies must report accidents, near-misses, and system failures. This data should be accessible to researchers, not proprietary.

Establish liability clarity: Before approving service, cities must determine who pays when accidents happen. Is it the company? Insurance? The city? This must be clear in advance, not litigated after incidents.

Create human oversight mechanisms: Cities should require human monitoring during early deployment phases. If the autonomous system fails, a human can take over. This builds safety margins.

Consider equity: Who benefits from autonomous vehicles? Who bears costs? Are low-income people served, or just wealthy customers? Regulation should ensure equitable access.

Plan for displacement: Autonomous vehicles will eliminate driving jobs. That's millions of people. Regulation should require companies to support retraining and transition assistance.

Preserve city authority: Federal preemption removes cities' ability to regulate technologies on their streets. That's undemocratic. Regulation should preserve local control.

None of this prevents autonomous vehicles from existing. It just ensures they're deployed thoughtfully, safely, and equitably.

Waymo opposes most of these measures because they slow deployment and add costs. That's Waymo's perspective. But cities have legitimate reasons to want them.

The Bigger Picture: When Innovation Outpaces Democracy

Waymo's campaign illustrates a fundamental tension in modern governance: technology moves faster than democracy.

Autonomous vehicles exist. They're being tested. They're becoming real. But we haven't had deliberate, inclusive democratic conversations about whether we want them, under what conditions, or what benefits and harms we're accepting.

Instead, companies are making those decisions through regulatory pressure and lobby campaigns. Public input is manufactured through grassroots mobilization, not genuine deliberation.

This pattern isn't unique to autonomous vehicles. It's happened with social media (Facebook's regulatory capture), cryptocurrency (industry pressure preventing regulation), and AI generally (companies racing ahead while regulation lags).

The underlying problem is that democratic institutions move slowly. Regulation requires hearings, expert analysis, stakeholder input, and deliberation. That takes time. Companies want approval faster.

So companies have learned to work around democracy. They mobilize citizens. They lobby aggressively. They operate in legal gray areas. They threaten to take business elsewhere if regulation gets too strict.

This isn't inherent to technology. It's a choice technology companies make. They could work within democratic processes. Instead, they push against them.

Waymo's DC campaign is a symptom of this larger dynamic. The company wants to deploy robotaxis. Democracy might say no, or yes with conditions. The company prefers to bypass democracy and go straight to approval.

What City Officials Can Do Right Now

If you're a city official or citizen concerned about autonomous vehicle regulation, here's what to consider:

First, separate information from pressure: When you receive citizen messages about a technology, ask whether those messages are genuine grassroots opinion or manufactured pressure. Most of the time, you can tell. Citizens mobilized through corporate campaigns often use similar language, often express the same talking points, often don't engage with policy nuances.

Second, demand transparency: Before approving any autonomous vehicle service, require the company to publish accident data, safety metrics, and performance statistics. This data should be reviewed by independent engineers, not just accepted as the company claims.

Third, establish liability frameworks first: Before approving service, have legal discussions about liability. If a robotaxi hits a pedestrian, who pays? Make this decision deliberately, not in response to accidents.

Fourth, preserve local authority: When federal preemption legislation is considered, oppose it. Cities should maintain the right to regulate technologies on their streets. Federal preemption removes that authority and gives it to agencies that move slowly and face intense industry lobbying.

Fifth, require equity analysis: Autonomous vehicles create both benefits and harms. Some people gain cheaper transportation. Others lose driving jobs. Regulation should address both impacts.

Sixth, phase deployment carefully: Instead of approving unlimited operations, require phased rollouts. Start with human monitoring, expand gradually, maintain review checkpoints.

FAQ

What is Waymo and how is it related to Alphabet?

Waymo is the autonomous vehicle division of Alphabet, Google's parent company. Waymo develops, tests, and operates self-driving cars. The company spun out as a separate Alphabet subsidiary in 2016 and has since become the most advanced autonomous vehicle company in the US, operating robotaxi services in six major metropolitan areas.

Why is Waymo pushing DC so hard if it operates successfully in other cities?

Waymo is pushing DC because it represents a major metropolitan market with high revenue potential. DC also demonstrates that the company can overcome regulatory resistance in a major blue-state city, which would validate its ability to operate in other regulated urban markets like Boston and Los Angeles. Success in DC would create a precedent for other cities to approve service.

How does Waymo's citizen pressure campaign differ from legitimate grassroots movements?

Waymo's campaign uses a pre-written template, asks residents to personalize it (rather than express authentic concerns), and mobilizes citizens through corporate communication channels. Genuine grassroots movements emerge from citizen concern, not corporate initiative. Waymo controlled the narrative, framing, and talking points, while making it appear citizen-driven.

What specific safety concerns do cities like DC have about autonomous vehicles?

Cities have multiple safety concerns: accident liability (who pays if a robotaxi hits someone), system failures in complex traffic situations, performance in adverse weather, ability to handle emergency vehicles and construction zones, and the lack of transparent, independent safety data. DC wanted to establish clear regulatory frameworks addressing these issues before approving service, but Waymo wanted approval without addressing them comprehensively.

Has the Uber and Lyft playbook for regulatory pressure actually worked for them?

Yes, extensively. Uber and Lyft used identical grassroots mobilization tactics to force most US cities to legalize ride-sharing despite regulatory concerns. Then they lobbied for state preemption laws preventing cities from regulating driver classification, benefits, or labor protections. Today, both companies operate in most US cities with minimal restrictions because of those successful regulatory circumvention campaigns.

What would federal preemption mean for cities' ability to regulate autonomous vehicles?

Federal preemption would remove cities' authority to regulate where autonomous vehicles operate, how many can be deployed, what safety standards they must meet, and how accidents are handled. That authority would transfer to federal agencies like the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. Historically, federal regulators set weaker standards than cities do, so preemption would likely accelerate autonomous vehicle deployment with less local oversight.

Why haven't other autonomous vehicle companies used identical pressure campaigns?

Some have, in different forms. Cruise used regulatory pressure tactics in San Francisco. Nuro lobbied for federal exemptions. Tesla influences regulators through public advocacy and strategic testing announcements. But Waymo's DC campaign is particularly visible because the company sent an explicit email asking residents to contact officials, making the tactic obvious. Other companies use more subtle lobbying approaches.

Could DC simply refuse to approve Waymo and prevent robotaxis from operating?

DC could refuse approval, but faces pressure because federal preemption legislation might override that refusal. If Congress passes laws preventing states and cities from banning autonomous vehicles, DC's authority disappears regardless of what it decides now. Additionally, refusing Waymo creates political risk for officials because the company has mobilized public support, making opposition seem anti-innovation.

What happened with autonomous vehicle regulation during Waymo's pressure campaign?

The campaign appears to have influenced DC's regulatory posture. Initially, officials moved slowly on autonomous vehicle approval. After Waymo's citizen mobilization, pressure increased. The DC Department of Transportation began considering frameworks for autonomous vehicle testing and eventual commercial service. This suggests the grassroots campaign achieved its intended effect, pushing officials toward approval they had been resisting.

How does autonomous vehicle regulation compare internationally?

Germany and the UK require rigorous safety testing before approving commercial service. Singapore allows testing only in controlled environments. China allows rapid deployment with minimal oversight. The US falls somewhere in the middle but is shifting toward the China model because of corporate pressure. Waymo's campaign is part of that shift.

Conclusion: When Companies Shape Policy

Waymo's DC campaign teaches an important lesson about modern governance: major corporations have learned to shape policy by mobilizing citizens rather than working through democratic institutions.

This isn't necessarily new. Corporations have always lobbied governments. But using grassroots pressure campaigns to create political cover for decisions made elsewhere is a relatively recent tactic that has proven remarkably effective.

The Waymo case shows how it works. The company faces a regulatory bottleneck. City officials want more information about safety and liability. Rather than engaging with those legitimate concerns, Waymo went to residents. Get enough people to contact officials, and the approval becomes easier. Opposition looks anti-innovation. Caution looks like obstruction.

Within 90 minutes, Waymo had 1,500 citizen messages to DC leaders. That's significant political pressure. It's also completely artificial.

This matters because it reveals how 21st-century regulation actually works: through corporate-engineered pressure, manufactured consent, and circumvention of deliberate democratic processes.

Autonomous vehicles might be beneficial. They might improve transportation. But that's a decision cities should make thoughtfully, with transparent information, through genuine deliberation. They shouldn't make it because a tech company mobilized residents to pressure them.

The solution isn't to ban autonomous vehicles. It's to strengthen regulatory institutions so they're not easily pushed around by corporate campaigns. It's to require transparency, independent safety audits, and equity analysis before approval. It's to preserve local authority instead of allowing federal preemption.

Most importantly, it's to resist the corporate pressure campaign playbook that Waymo, Uber, and others have perfected. That playbook works because we accept it as normal. But there's nothing normal about corporations using astroturf campaigns to shape public policy.

Waymo's DC push is a test case. If the company succeeds through pressure campaigns rather than careful regulation, it will validate a model other companies will replicate. Congress might pass preemption laws. Cities might lose authority over technologies deployed on their streets.

Or, cities could insist on transparent, deliberate regulation. They could demand independent safety data. They could preserve local authority. They could require equity analysis. They could treat autonomous vehicles seriously, not as something to approve reflexively because a company pressured them.

That would be slower. It would be harder. But it would be democratic. And for a technology this consequential, democracy should matter more than deployment speed.

Key Takeaways

- Waymo used astroturf campaigns to pressure DC officials into approving robotaxis after 1+ year of regulatory stonewalling, mirroring Uber's successful playbook

- The company mobilized 1,500 residents in 90 minutes using pre-written messaging, demonstrating how corporations manufacture grassroots pressure

- Autonomous vehicle regulation is fragmented across 50 states, allowing companies to shop for favorable rules and pressure holdouts

- Federal preemption legislation would remove cities' authority to regulate autonomous vehicles, centralizing control with slower federal agencies

- This regulatory circumvention pattern repeats across tech: Uber used it for ride-sharing, Bird for scooters, and now Waymo for autonomous vehicles

- Cities lack resources to counter corporate lobbying campaigns, making grassroots pressure extremely effective political leverage

- International comparisons show countries like Germany maintain stronger regulatory authority by requiring rigorous safety testing before commercial approval

Related Articles

- Waymo's Sixth-Generation Robotaxi: The Future of Autonomous Vehicles [2025]

- Waymo's Fully Driverless Vehicles in Nashville: What It Means [2025]

- Waymo's Nashville Robotaxis: The Future of Autonomous Mobility [2025]

- Waymo's Genie 3 World Model Transforms Autonomous Driving [2025]

- How Waymo Uses AI Simulation to Handle Tornadoes, Elephants, and Edge Cases [2025]

- Waymo's DC Regulatory Battle: Autonomous Vehicles Face Urban Complexity [2025]

![Waymo's DC Robotaxi Campaign: How AI Companies Are Reshaping City Regulation [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/waymo-s-dc-robotaxi-campaign-how-ai-companies-are-reshaping-/image-1-1770928730615.jpg)