Introduction: When Destruction Is Part of the Design

In late November, a Rocket Lab employee made a call that would spark headlines and speculation across the aerospace industry. The caller reached the Stennis Space Center Fire Department from a test stand in southern Mississippi with an urgent message: there was a fire at the facility where Archimedes engines were being tested. According to dispatcher logs, it started during a test when "an anomaly caused an electrical box to catch fire."

But that sanitized description masked a more dramatic reality. Satellite imagery showed the roof of the left test cell had been blown completely off. Sources close to the incident described it differently from the official report: this wasn't just an electrical fire. It was a catastrophic engine explosion. The kind of test failure that would terrify most companies. The kind that makes you wonder if something has gone seriously wrong.

Except nothing had gone wrong. Everything was going exactly according to plan.

This is the story behind one of the most misunderstood practices in rocket development: intentional engine failure testing. It's also a window into how Rocket Lab is preparing its most ambitious rocket to date. The company is building the Neutron, a heavy-lift vehicle powered by nine Archimedes engines, each producing 165,000 pounds of sea-level thrust. These aren't small, manageable test articles. They're the real deal. And before any of them fly on an actual rocket, they need to be pushed to the absolute edge of their operating limits and beyond.

What happened at Stennis wasn't a crisis. It was Thursday.

The Archimedes Engine Context

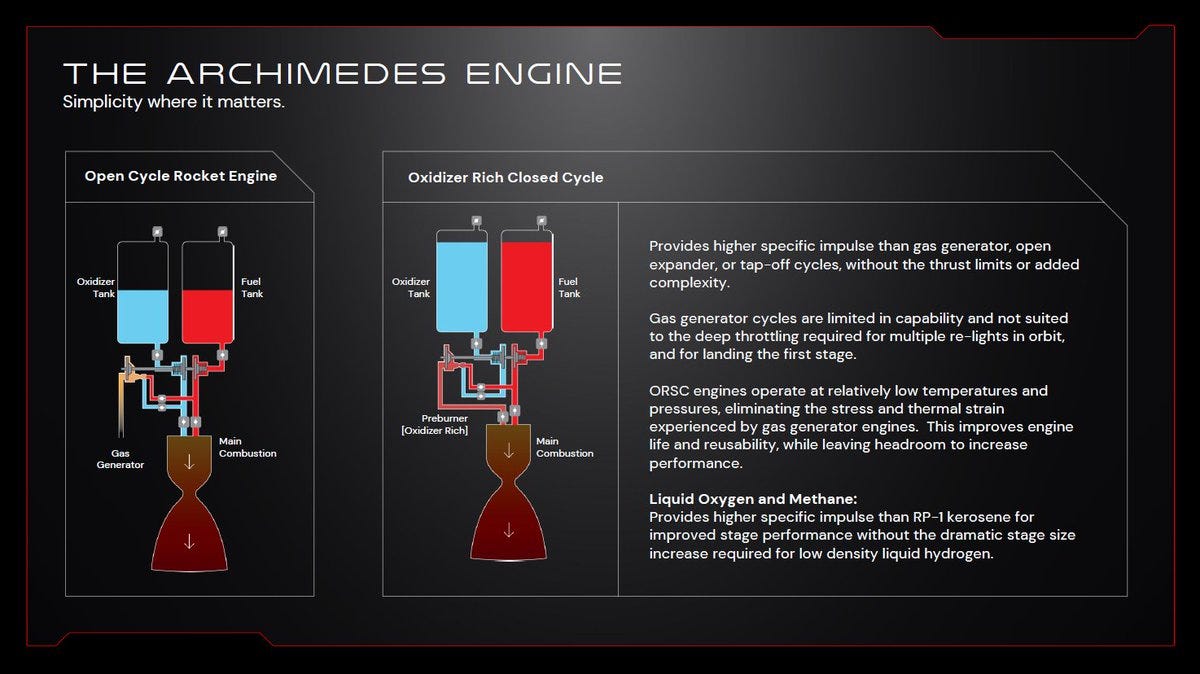

The Archimedes engine represents a significant leap for Rocket Lab. The company built its reputation on the Electron rocket, a small-lift vehicle powered by the Rutherford engine, an electric-pump-fed rocket that's quite different from traditional hypergolic designs. But Neutron is a different beast entirely. It burns liquid oxygen and methane at significantly higher pressures and flow rates than anything Rocket Lab has operationally deployed.

Liquid oxygen and methane—commonly called LOX and methane—create a more energetic propellant combination than the hypergolic propellants Rocket Lab has traditionally used. This means higher performance, more thrust, and greater complexity. The Archimedes engine needs to operate with precision across a broader range of conditions than anything the company has flown before. It needs to be robust enough to handle the stresses of launch, yet efficient enough to deliver the performance numbers Rocket Lab has promised.

That combination of demands is precisely why these engines need to fail spectacularly before they ever leave the ground.

Understanding Engine Test Philosophy

Rocket engines aren't like car engines that you test to ensure they meet reliability targets and then put into production. Rocket engines exist in a realm of extremes. They operate at pressures and temperatures that would destroy nearly any material. They burn propellants that release enormous amounts of energy in confined spaces. They need to function flawlessly for minutes at a time while being exposed to conditions that would melt conventional metals.

Because of these extremes, rocket companies have developed an engineering philosophy around engine testing that goes beyond the typical find-and-fix approach. Instead of testing engines to ensure they meet specifications, rocket engineers test engines to understand where those specifications break down. They test to find the boundaries of safe operation. They test to discover failure modes that might not be obvious from theoretical analysis.

This philosophy has a practical purpose that extends far beyond academic curiosity. Every failure discovered during a ground test is one less failure that might occur in flight. Every broken engine at a test stand is infinitely preferable to a broken engine in the sky. The cost difference between a destroyed test engine and a destroyed rocket with payload is measured in millions of dollars. More importantly, the safety difference is measured in potential loss of life and mission criticality.

Rocket Lab Chief Executive Officer Peter Beck articulated this approach directly when responding to concerns about the Archimedes test failures: "We test to the limits, that's part of developing a successful rocket. We often put the engine into very off nominal states to find the limits and sometimes they let go, this is normal and how you ensure rockets don't fail in flight."

The Test Cadence Question

One of the most interesting aspects of Rocket Lab's response to the engine test failures was the emphasis on test cadence. Beck stated that because Rocket Lab has two test cells at the Stennis facility, a catastrophic failure in one cell doesn't interrupt the overall testing schedule. "We have two test cells so we can do these types of tests and not interrupt our test cadence or production flow, hence there is zero impact to schedule," he said. "In fact 48 hours later we were running engines again."

This detail reveals something important about how modern rocket companies approach engine development. The goal isn't to avoid failures. The goal is to achieve a testing velocity that allows you to fail fast, learn quickly, and move forward without delay. Two test cells enable a strategy where one can be undergoing aggressive, destructive testing while the other conducts more nominal qualification runs. You're not waiting for repairs between tests. You're not pausing development because one engine decided to catastrophically fail under extreme conditions.

This acceleration of the testing timeline has real implications for development schedules. Historically, rocket engine development has been a multi-year process with extended gaps between test attempts while engineers analyzed data and implemented changes. Modern companies have compressed that timeline by running more tests, more frequently, with better instrumentation to capture what's happening in the microseconds before failure occurs.

What "Very Nasty Things" Actually Means

When Beck described the current phase of Archimedes testing, he used language that initially sounds alarming: "Right now we are in the part of the program where we are doing very nasty things to the engine like backing right off the suction pressure, inducing cavitation and exploring outside the run box."

To someone unfamiliar with rocket engine terminology, this sounds chaotic and reckless. In reality, it's precisely the opposite. Beck is describing a deliberate, methodical exploration of failure modes. Let's unpack what these terms actually mean.

Backing off suction pressure refers to reducing the pressure at the inlet of the turbopump, the device that pressurizes the propellants before they enter the combustion chamber. At normal operating points, the turbopump inlet operates at specific pressure levels that ensure smooth flow and prevent cavitation. By reducing this pressure, engineers intentionally create conditions that push toward the edge of pump cavitation.

Cavitation is what happens when pressure drops below the vapor pressure of a liquid, causing bubbles to form within the flow. In a rocket engine, cavitation is catastrophic because it disrupts the smooth flow of propellant, reduces cooling effectiveness, and can damage pump components. Inducing cavitation is like deliberately creating a condition that the engine wasn't designed to handle, specifically to understand what happens when you cross that boundary.

Exploring outside the run box means operating the engine at thrust levels, mixture ratios, and chamber pressures that fall outside the normal flight envelope. The run box is the operating region where the engine is certified to function. Outside that box, all bets are off. Engineers operate outside the box specifically to find where the boundaries actually should be, whether current assumptions are conservative enough, and what happens when you push past them.

These aren't accidents. They're methodical. They're designed. And they're producing the kinds of failures that make engines "let go," as Beck described it.

Precedent from Other Rocket Companies

Rocket Lab isn't unique in pushing engines to failure during development. This is standard practice across the industry, though it's not always visible to the public. SpaceX's Raptor engine development involved numerous test failures. When NASASpateflight installed cameras outside SpaceX's McGregor test facility in Texas, footage became available showing the reality of modern engine development. Raptor tests regularly ended with dramatic explosions, destroyed turbopumps, and catastrophic failures of engine sections.

The difference is visibility. SpaceX's test failures at McGregor became famous precisely because enthusiasts with cameras documented them. For most of rocket history, engine testing has occurred in remote, restricted areas away from public view and documentation. Rocket Lab's test failures at Stennis might not have become public at all if satellite imagery hadn't captured the damage.

Blue Origin, developing the BE-4 engine for the United Launch Alliance, conducted extensive failure testing during development. Boeing and Lockheed Martin did the same with the RS-68 and other large engines. The Space Shuttle Main Engine required years of development with multiple test failures before it was certified for flight. This is the normal cost of developing engines that will reliably power crewed vehicles or expensive national security payloads.

The fact that Rocket Lab is conducting similar tests is not evidence of problems. It's evidence of good engineering practice.

The Risk of Skipping the Hard Tests

There's a tempting alternative to all this destructive testing: run fewer tests, operate within narrower margins, and hope nothing unexpected happens in flight. Some companies have tried this approach. The results are predictable.

Rocket Motor Two, Virgin Galactic's air-launch spaceplane, experienced a catastrophic hybrid rocket motor failure during flight in 2014 that killed one of two pilots. The investigation revealed that the company had insufficient understanding of their motor's failure modes and hadn't conducted the aggressive ground testing necessary to understand how the motor might behave under unexpected conditions.

The Orbital Sciences Antares rocket failed in 2014 when one of its AJ26 engines, powered by Soviet-era NK-33 designs, experienced an undiagnosed failure. The company had attempted to use legacy engines without fully understanding their operational limits under modern conditions. Insufficient ground testing meant insufficient understanding of failure modes.

These failures didn't happen in isolation. They happened because development programs chose efficiency over thoroughness, chose faster schedules over comprehensive understanding. By contrast, SpaceX's aggressive testing program and willingness to accept multiple failures during Raptor development meant that when Raptor finally flew on Starship, the engine had been exposed to a far broader range of conditions than would typically be encountered in flight.

This is the hidden cost of development programs that avoid the hard tests. The cost materializes later, in flight failures, schedule delays, and mission losses.

Infrastructure Damage and Design Philosophy

The fact that a test failure at Stennis blew off the roof of a test cell might seem like a problem. In one sense, it definitely is: infrastructure damage is expensive and inconvenient. In another sense, it's valuable information.

Test infrastructure is explicitly designed with failure in mind. Test cells have structures that allow for catastrophic engine failures without cascading damage to critical systems. They're engineered to contain explosions and direct the worst energy away from control systems, instrumentation, and other critical infrastructure. The fact that an engine explosion damaged the test cell structure but didn't destroy irreplaceable equipment or create a safety hazard is exactly how good test infrastructure is supposed to work.

Rocket Lab's decision to operate with two test cells reveals a design philosophy that accounts for failure as a normal part of operations. If failures were unexpected and unusual, you wouldn't design your test infrastructure to handle multiple simultaneous test cells with the assumption that one might occasionally fail catastrophically. You design for it because it's not if failure happens, it's when.

Schedule Impact and Realism

Beck's statement that the test failures had "zero impact to schedule" warrants scrutiny. On the surface, it seems implausible. You blow up an engine, damage a test cell, and somehow there's no schedule impact?

But the logic holds under one condition: if the test failures are expected and accounted for in the development schedule. If Rocket Lab planned to conduct 50 engine tests during Archimedes development, and 3 or 4 of those tests end in catastrophic failure, that's not a schedule delay. That's part of the plan. The schedule already accounts for failures. The schedule was built assuming a certain number of engines would be destroyed in testing.

This is radically different from the scenario where you're expecting to run 20 tests, successfully complete all 20, and then discover in test 21 that something unexpected happens. In that scenario, you have schedule impact. You have unplanned delays. You have engineers scrambling to understand what went wrong.

The fact that Rocket Lab could absorb these failures without schedule impact suggests they were testing according to plan, destroying engines they expected to destroy, in pursuit of information they needed to extract. This is good project management. This is the sign of a company that understands what it's doing.

Data Extraction from Failure

One element that's easy to overlook: every time an engine fails during testing, engineers learn something. Modern rocket engines are instrumented with hundreds of sensors. Pressure transducers, thermocouples, vibration sensors, strain gauges, high-speed cameras, and acoustic monitoring systems all feed data into the test control system.

When an engine fails, all that data is still there. In fact, the most valuable data often comes from the seconds immediately before and during failure. How did pressure change? Where did it change first? Which sensor went to its maximum reading before others? How did the engine physically respond to the developing failure condition?

A catastrophic engine failure that occurs at a test stand with full instrumentation provides far more information about failure modes than a successful test run ever could. You learn the exact conditions that led to failure. You learn whether the failure was caused by cavitation, structural resonance, thermal issues, or something else entirely. You learn whether your design margins are adequate or whether they need to be expanded.

In some cases, a test failure reveals that a component was never going to work under the desired conditions, and a fundamental redesign is needed. In other cases, it shows that a small design modification can solve the problem. Either way, the information is gold for engineers trying to build a reliable engine.

Turbopump Challenges

The turbopump is arguably the most critical and most challenging component in a rocket engine. It's a device that needs to take liquid propellant from a tank at relatively low pressure and accelerate it to incredibly high pressures and flow rates in microseconds. The Mars rover Perseverance costs about $2.7 billion dollars and is probably less sophisticated than a rocket engine turbopump.

Turbopumps operate at extraordinary speeds. A LOX turbopump for a large engine might spin at 35,000 RPM or higher while pumping hundreds of thousands of pounds of fluid per minute. At these speeds, vibrations, cavitation, and imbalances can cause failures within milliseconds. Small imperfections in blade geometry can cause resonances that build catastrophically. Tiny amounts of wear can change the dynamic characteristics of the pump until it becomes unstable.

This is why inducing cavitation and backing off suction pressure are such critical tests. These conditions stress the turbopump in ways that normal operation never will. They expose design flaws that might not manifest under nominal conditions but could appear in unexpected flight scenarios. They help engineers understand the margin between normal operation and failure.

Learning from Modern Competitors

SpaceX's Raptor engine is one of the most advanced rocket engines ever built. It uses a full-flow staging cycle, a complex approach where both the oxygen and fuel turbines exhaust directly into the engine's combustion chamber. This design enables higher efficiency but also introduces additional complexity and failure modes.

Raptor development involved extensive ground testing with multiple catastrophic failures. Videos from SpaceX's McGregor facility show Raptor tests ending in dramatic explosions, complete turbopump failures, and other impressive destruction. But those failures weren't failures of Raptor as a production engine. They were failures of Raptor during the development process, while engineers were still exploring the engine's boundaries.

When Raptor finally flew on Starship, it had been tested far more thoroughly than most engines are ever tested. The extensive ground testing and willingness to accept multiple failures during development meant that the flight engine had a much higher probability of functioning as designed.

Rocket Lab, by adopting a similar philosophy with Archimedes, is following a proven path. SpaceX proved that extensive failure testing during development leads to robust engines. Blue Origin proved it with BE-4 development. The aerospace industry has proven it repeatedly across decades of engine development. Rocket Lab is simply following best practices.

Component-Level Testing Strategy

Beck emphasized that Rocket Lab's goal is to identify failures during "component level testing" rather than allowing failures to propagate to system level or flight level. This is the right engineering hierarchy.

Component level testing focuses on individual parts: turbopumps, injectors, combustion chambers, turbine blades, seals, and other discrete elements. System level testing integrates those components into a full engine and tests the integrated behavior. Flight level testing is when you actually launch the rocket.

The cost and consequences escalate dramatically at each level. A turbopump failure discovered during component testing might cost $500,000 to address. The same failure discovered during system-level engine testing might cost millions. Discovered during flight, it might cost tens of millions or more, not to mention the loss of the payload and potential loss of crew if it's a crewed vehicle.

Rocket Lab's emphasis on component-level discovery aligns with this escalating cost structure. Push components to failure in a lab setting, understand what breaks, fix it, and move up to the next level. This approach avoids the catastrophic cost of discovering problems late in development or in flight.

The Off-Nominal State Philosophy

One phrase Beck used deserves deeper examination: "very off nominal states." In engineering terminology, nominal means "expected" or "normal." Off-nominal means outside normal conditions. Very off-nominal means you're exploring territories far from where the engine was designed to operate.

This is intentional. Engineers recognize that no matter how well a rocket is designed, it will sometimes operate in off-nominal states during flight. An engine might experience higher-than-expected chamber pressure. Propellant flow rates might be slightly different than predicted. Thrust vector control might require the engine to operate at an unexpected mixture ratio. These things happen. The question is whether the engine can survive them.

Testing in very off-nominal states—intentionally creating conditions the engine wasn't designed for—helps answer this question. It shows engineers how much margin exists between nominal operation and failure. It reveals whether that margin is adequate for flight safety or whether designs need to be more robust.

This is why Rocket Lab's description of their testing approach is so important. They're not accidentally pushing engines into off-nominal states. They're deliberately exploring these territories to understand failure boundaries and ensure the flight engine is robust enough to handle unexpected conditions.

Quality Control and Flight Readiness

A common misconception about engine test failures is that they indicate quality control problems or that the engine isn't ready for flight. In reality, the opposite is often true. The companies that fail to discover problems during ground testing are the ones most likely to experience failures in flight.

Rocket Lab's approach—deliberately inducing failures and exploring failure modes during development—is a form of quality control. It's a way of ensuring that the flight engine has been exposed to a broader range of conditions than it will encounter in actual operation. It's a way of verifying that design margins are adequate.

Flight readiness isn't determined by how many engines you've tested successfully. It's determined by how thoroughly you understand your engine's limits and how confident you are that the flight engine operates well within those limits. A company that tests 30 engines successfully but doesn't understand failure modes is less ready for flight than a company that tests 30 engines, intentionally fails 5 of them, and has deep understanding of what caused those failures.

The Cost of Engine Development

Developing a rocket engine is one of the most expensive undertakings in aerospace. A single engine test can cost hundreds of thousands of dollars. A full development program for a large rocket engine can cost hundreds of millions. SpaceX spent over a billion dollars developing the Raptor engine. Blue Origin's BE-4 development was similarly expensive.

For a company like Rocket Lab, which is working with finite resources, the investment in Archimedes development represents a substantial commitment. The fact that they're willing to deliberately destroy engines during that development process shows confidence in the engine's design and the development strategy.

Budgeting to destroy engines—accounting for the cost of failed tests as part of the normal development process—is a sign of a mature development program. It's the opposite of a program hoping to get lucky. It's a program that expects to fail, plans for that failure, and uses those failures as stepping stones to success.

Industry Comparison: Who Tests Aggressively?

The aerospace companies most trusted to fly critical payloads are the ones with the most extensive testing histories. NASA's Space Launch System underwent enormous amounts of testing before its first flight. The Space Shuttle Main Engine required 3,000+ test firings during development. These were engines and systems that couldn't afford to fail in flight because the consequences were unacceptable.

By contrast, companies with less robust testing programs often experience more flight failures. The pattern is clear and consistent: companies that test more aggressively, accept more failures during development, and develop deeper understanding of their systems fly more reliably.

Rocket Lab's aggressive testing approach follows this proven pattern. It's not a sign of problems. It's a sign of a company that understands the cost of failures and is willing to pay that cost during development to avoid paying it during flight.

Communication and Perception

One element worth noting: Rocket Lab initially downplayed the Stennis incident. The fire department dispatcher log described it as an "electrical fire." Only when pressed by external questions did the reality emerge: this was a catastrophic engine explosion. This gap between initial characterization and actual event reveals something about how aerospace companies communicate about failures.

There's always tension between transparency and not alarming the public or investors. A catastrophic engine explosion sounds bad. A catastrophic engine explosion during intentional failure testing as part of normal development sounds reasonable. The difference is context.

Rocket Lab ultimately provided that context through CEO Beck's statement. This kind of transparency is important for building trust with the aerospace industry and stakeholders. It shows that the company understands what's happening, is in control of the situation, and is following industry best practices.

Timeline to Neutron Flight

The fact that Archimedes testing is at the point where engineers are deliberately inducing catastrophic failures suggests the engine is in mid-to-late development stages. Early development focuses on getting the engine to run. Middle stages focus on expanding the operating envelope and understanding normal limits. Late stages focus on edge cases, failure modes, and the extreme conditions an engine might encounter.

Rocket Lab has stated that Neutron is aiming for a debut launch in late 2025 or 2026. The current testing phase—deliberately pushing engines into failure—suggests that development is on track for this timeline. If the company were discovering unexpected failures or running into fundamental design problems, the testing approach would be different. Engineers would be focused on fixing problems rather than exploring extreme conditions.

The aggressive testing schedule made possible by having two test cells supports a development timeline that brings the engine to flight readiness without unnecessary delays. Two cells enable parallel testing approaches that compress the overall development schedule while maintaining the thoroughness needed for a reliable production engine.

Long-Term Implications for Rocket Lab

The Archimedes engine represents Rocket Lab's transition from a small-launch specialist to a broader aerospace player. The Electron rocket served the company well, but the market for small lift vehicles is limited. Neutron, powered by Archimedes engines, opens access to significantly larger markets including commercial space stations, government payloads, and other applications that require greater capacity.

Successfully developing a reliable large rocket engine is the foundation for this expansion. If Rocket Lab executes well on Archimedes development and Neutron deployment, the company establishes itself as a credible heavy-lift provider. If the company stumbles, it opens space in the market for other providers.

The current testing approach—aggressive, thorough, and willing to accept failures—is the right strategy for avoiding stumbles. It's the path to building a reliable engine and a successful rocket. It's standard practice across the industry because standard practice exists for good reasons.

Conclusion: The Unsexy Reality of Rocket Development

A catastrophic engine explosion that destroys test infrastructure sounds dramatic. It sounds like something has gone wrong. In the context of rocket engine development, it sounds like exactly what should be happening.

Rocket Lab is in the phase of Archimedes development where engineers deliberately push engines to failure. They're inducing cavitation, backing off suction pressure, exploring outside the normal run box, and discovering exactly what it takes to make the engine fail. This is intentional. It's planned. It's the correct approach to developing a reliable engine.

The fact that Rocket Lab has two test cells enables them to conduct these aggressive tests without delaying the overall development schedule. The fact that they can absorb catastrophic failures without schedule impact is evidence that these failures were anticipated and planned for. The fact that they're willing to destroy engines to understand failure modes is a sign of a mature development program.

This is the unglamorous reality of rocket development. It's expensive. It's destructive. It involves blowing up perfectly good test articles. And it's absolutely essential for building rockets that don't fail in flight.

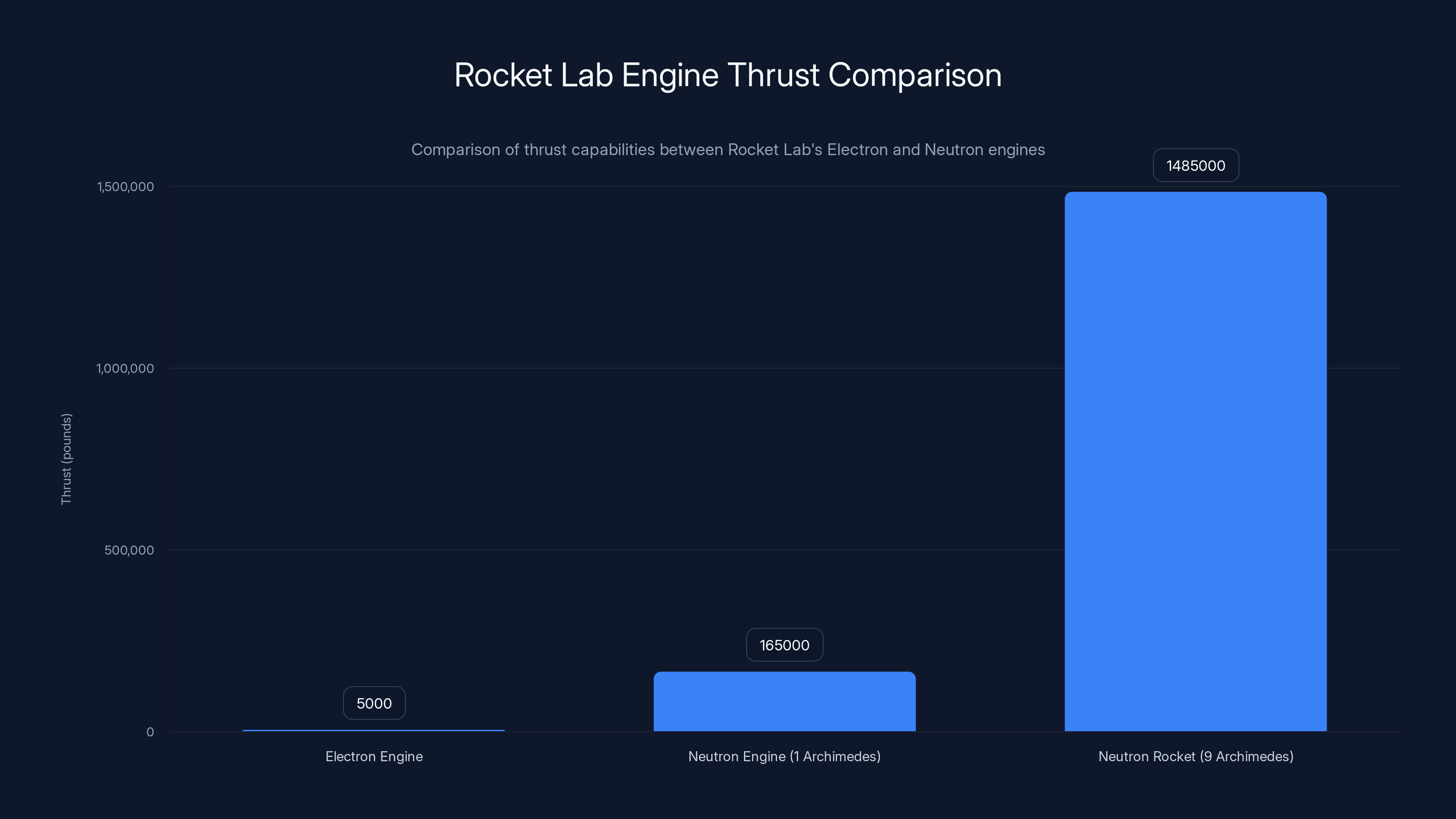

When Neutron launches later this year, it will do so carrying nine Archimedes engines that have been tested far more thoroughly than most rocket engines ever are. Some of those engines' siblings will have failed catastrophically at the test stand, providing engineers with critical information about engine limits and failure modes. That information will be embedded in the design of the flight engines. Those flight engines will be more reliable because their development included multiple carefully controlled failures.

That's not a story about problems. That's a story about how good engineering works.

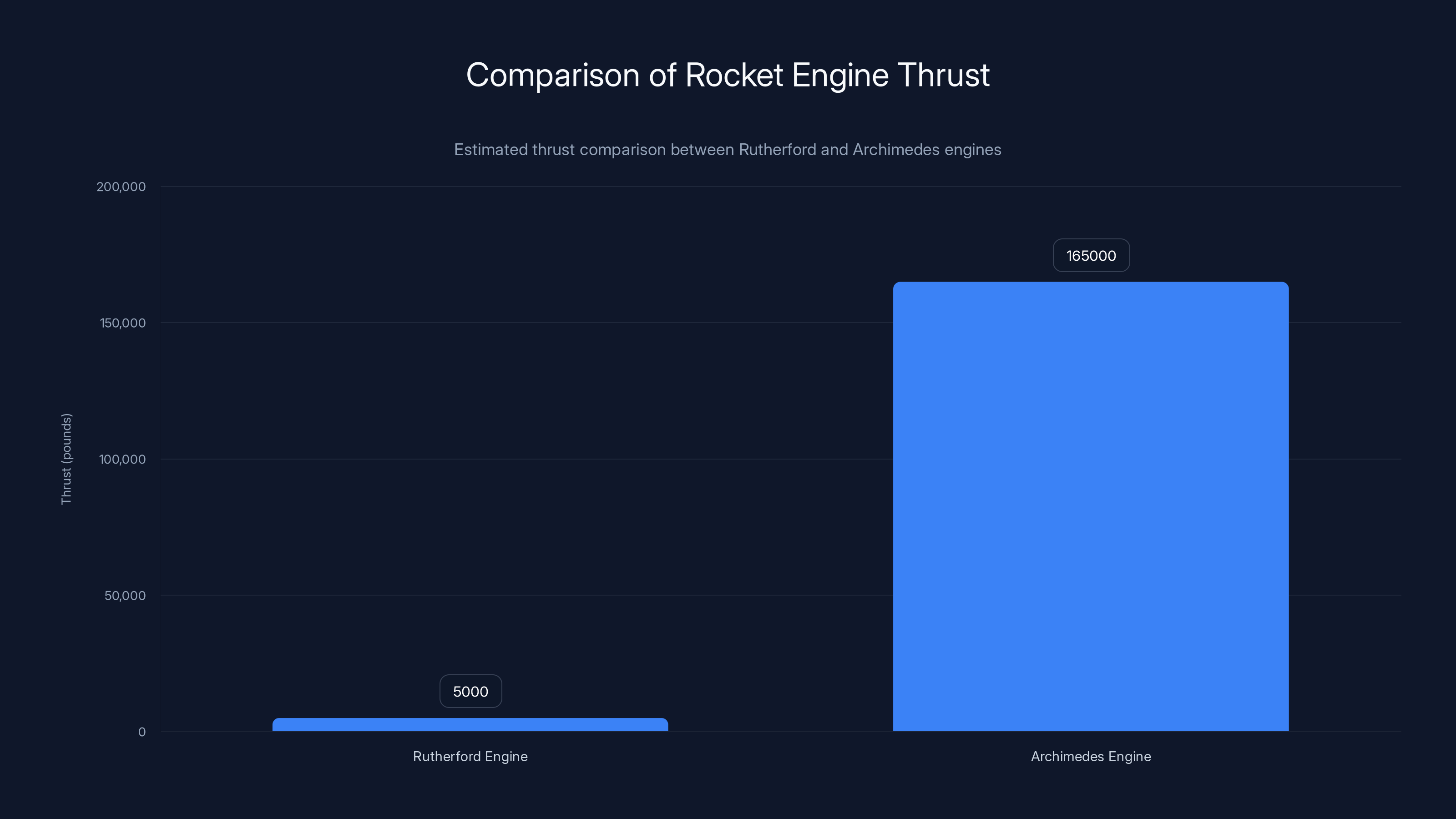

The Archimedes engine produces significantly more thrust than the Rutherford engine, marking a major advancement for Rocket Lab. Estimated data based on typical engine specifications.

FAQ

What is the Archimedes engine?

The Archimedes engine is a large liquid oxygen and methane rocket engine in development by Rocket Lab for use on the Neutron rocket. Each engine produces 165,000 pounds of sea-level thrust, representing a significant step up from the engines that power Rocket Lab's smaller Electron rocket. Nine of these engines will power the Neutron, which is designed to launch heavier payloads than Electron can accommodate.

Why does Rocket Lab deliberately test engines to failure?

Deliberate failure testing during development helps engineers understand an engine's limits, discover failure modes before they occur in flight, and verify that design margins are adequate for safe operation. Testing to failure reveals information that successful tests cannot provide, including how pressure changes before failure, which components are most vulnerable, and where designs might need to be more robust. This approach reduces the risk of unexpected failures during actual launch.

What does "backing off suction pressure" mean in rocket engine testing?

Backing off suction pressure refers to reducing the inlet pressure to the turbopump, the device that pressurizes propellants before they enter the combustion chamber. Lower inlet pressure increases the risk of cavitation, which is when bubbles form in the liquid flow and disrupt normal engine operation. By intentionally reducing suction pressure, engineers test how the engine responds to conditions at or beyond the edge of cavitation and can understand the margin between normal operation and turbopump failure.

How does having two test cells enable faster development?

With two test cells, Rocket Lab can conduct destructive failure tests in one cell while running more nominal qualification tests in the other cell simultaneously. This parallel testing approach compresses the overall development timeline because engineers don't need to repair or rebuild infrastructure between tests. One catastrophic failure doesn't interrupt the testing cadence because another engine can be running in the second cell while repairs occur on the first cell.

Is engine failure testing common in the aerospace industry?

Yes. All major rocket engine developers including SpaceX, Blue Origin, and traditional aerospace contractors conduct extensive failure testing during engine development. SpaceX's Raptor engine development involved multiple dramatic test failures. NASA's Space Shuttle Main Engine required over 3,000 test firings during development. Aggressive testing during development is the proven path to building reliable engines that function well during flight operations.

What happens to the data from a failed engine test?

Rocket engines are instrumented with hundreds of sensors including pressure transducers, thermocouples, vibration sensors, and high-speed cameras. When an engine fails during testing, all this sensor data remains intact and is analyzed by engineers to understand the exact failure mode. The data from the moments immediately before and during failure provides the most valuable information about engine limits. This information is used to improve designs and ensure flight engines have adequate design margins.

How could a test failure at Stennis impact the Neutron launch schedule?

According to Rocket Lab's CEO, the test failures had zero impact on schedule because they were anticipated and accounted for in the development plan. The presence of two test cells means catastrophic failure in one cell doesn't prevent testing from continuing in the other cell. If testing failures are expected and planned for, they're part of the normal development timeline rather than unexpected delays. Unexpected failures would impact schedule; planned failures do not.

Why is component-level testing preferable to system-level or flight-level testing?

Component-level testing costs significantly less and has lower consequences when failures occur. A turbopump component failure at a test stand might cost thousands to address, while the same failure discovered during flight could cost millions and potentially lose the entire mission. By discovering and fixing problems at the component level, engineers avoid the compounding costs and consequences of failures at higher levels of integration.

The Neutron rocket, powered by nine Archimedes engines, produces a combined thrust of 1,485,000 pounds, significantly surpassing the Electron's engine thrust of 5,000 pounds. Estimated data for Electron engine thrust.

Key Takeaways

- Rocket Lab is deliberately testing Archimedes engines to failure as part of normal development, not a sign of problems

- Engine failure testing is standard practice across the aerospace industry including SpaceX, Blue Origin, and traditional contractors

- Testing to find failure modes during component-level development prevents catastrophic failures during flight

- Having two test cells allows Rocket Lab to conduct aggressive destructive tests while maintaining development schedule

- Archimedes development follows proven strategies for building reliable large rocket engines for Neutron launches

Related Articles

- SpaceX Starship Upper Stage Malfunction: Launch Recovery Timeline [2025]

- Why NASA Finally Allows Astronauts to Bring iPhones to Space [2025]

- SpaceX Super Heavy Booster Cryoproof Testing Explained [2025]

- Why Elon Musk Pivoted from Mars to the Moon: The Strategic Shift [2025]

- SpaceX's Moon Base Strategy: Why Mars Takes a Backseat in 2025 [2025]

- NASA Astronauts Can Now Take Smartphones to Space [2025]

![Rocket Lab's Archimedes Engine Explosions: Why Blowing Up Is Part of the Plan [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/rocket-lab-s-archimedes-engine-explosions-why-blowing-up-is-/image-1-1770845954449.jpg)