Space X Starship Upper Stage Malfunction: What Happened and What's Next

It's one of those moments in spaceflight when everything looks perfect on paper until it doesn't. Early February brought sobering news from Space X: a Falcon 9 rocket launched successfully from Vandenberg Space Force Base in California, deployed its 25 Starlink satellites exactly as planned, but then encountered what the company described as an "off-nominal condition" during a critical engine firing sequence. That phrase, in aerospace speak, means something went wrong in a way engineers didn't expect.

The second stage was supposed to perform a controlled deorbit maneuver—a precision burn designed to guide the rocket's upper stage back through the atmosphere in a planned, destructive reentry. Instead, the stage couldn't execute this final firing. It remained in low-altitude orbit, eventually tumbling back to Earth in an unguided trajectory later that week. No debris reached populated areas, but the incident was significant enough that Space X immediately halted subsequent launches while teams dove into the data.

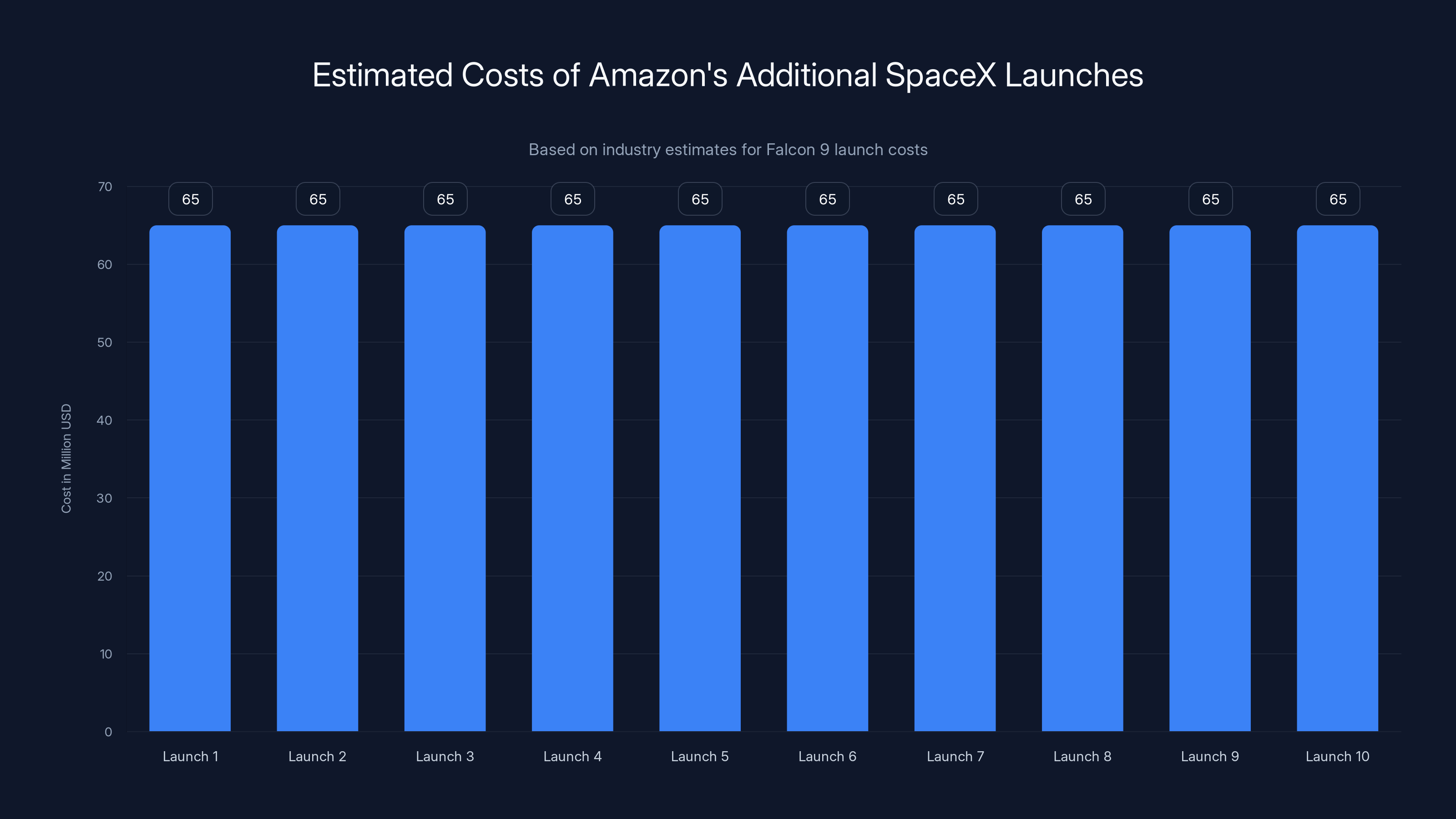

This isn't just another anomaly report filed away in aerospace archives. The timing matters. Amazon just committed to 10 additional launches with Space X, citing what the company called a "near-term shortage in launch capacity." That shortage isn't theoretical—it's real, immediate, and getting more acute as demand for satellite internet, commercial missions, and government contracts outpaces available launch vehicles worldwide. When Space X has to pause operations, the entire commercial space industry feels the ripple.

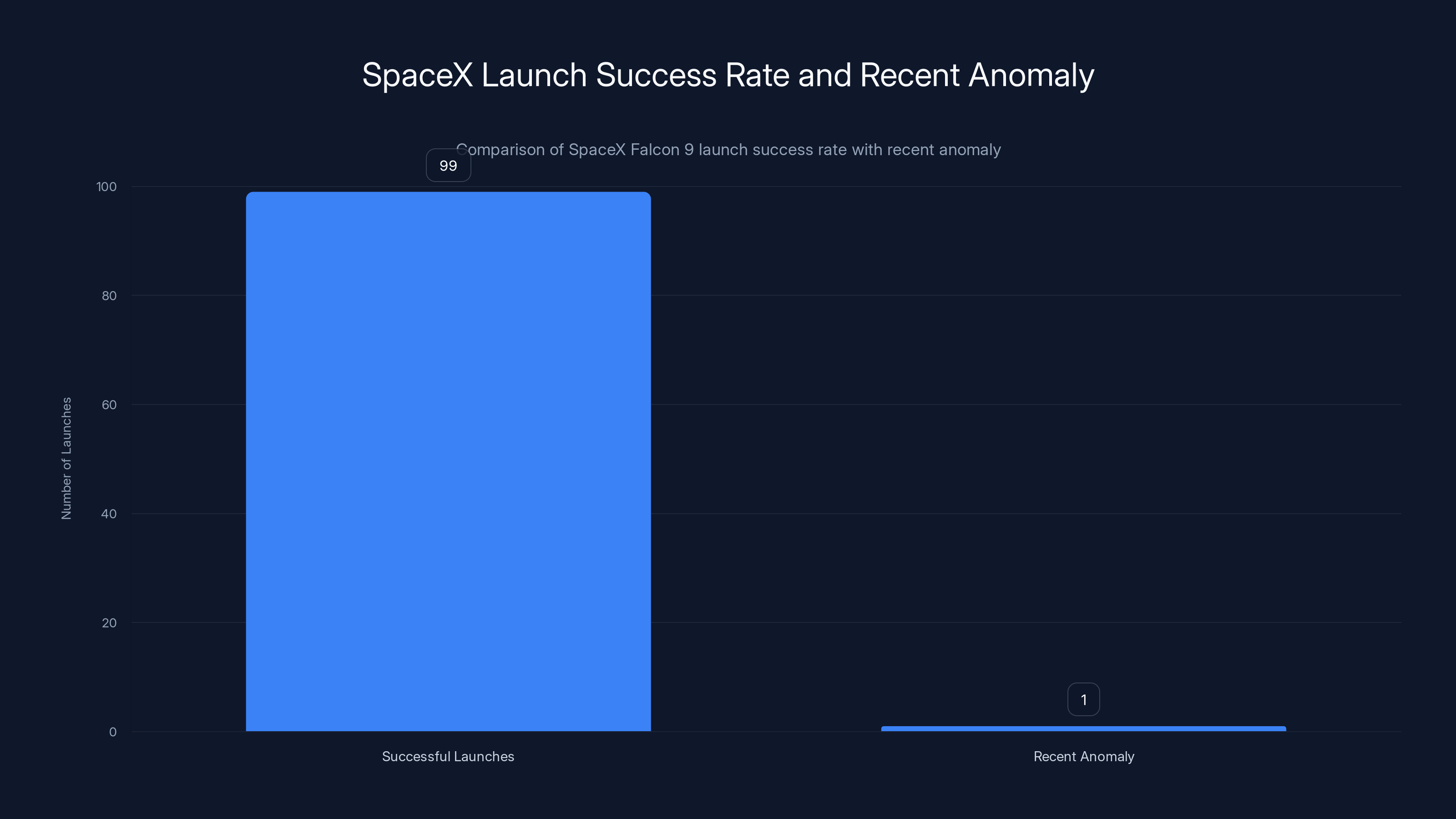

What makes this incident particularly noteworthy is the context surrounding it. Space X has achieved something remarkable: the Falcon 9 is the most reliable operational rocket in human spaceflight, with a success rate approaching 99%. But statistics hide the grinding reality of flight operations. Every launch is an experiment in controlled explosion. Every malfunction is a puzzle that demands answers before the next rocket lights its engines. And right now, the space industry is running at full throttle, with customers expecting launches on a schedule that leaves little room for extended troubleshooting.

Meanwhile, across the aerospace landscape, other programs face their own showdowns with physics and engineering. NASA's Space Launch System battles persistent hydrogen leak problems. China prepares to test next-generation crew hardware. Blue Origin makes startling strategic pivots. And Firefly Aerospace climbs out of a crater of its own making, preparing to launch again after catastrophic failures. The rocket business in 2025 is simultaneously booming and fragile—explosive growth paired with the very real consequences of getting something wrong at hypersonic speeds.

Let's dig into what happened with that Space X flight, why it matters, and what comes next for the company that's trying to make spaceflight routine.

TL; DR

- Space X Falcon 9 experienced upper stage malfunction during a deorbit burn on a Falcon 9 mission from Vandenberg, forcing the company to pause launches pending investigation

- Amazon booked 10 additional launches with Space X, signaling strong commercial demand despite the temporary flight pause

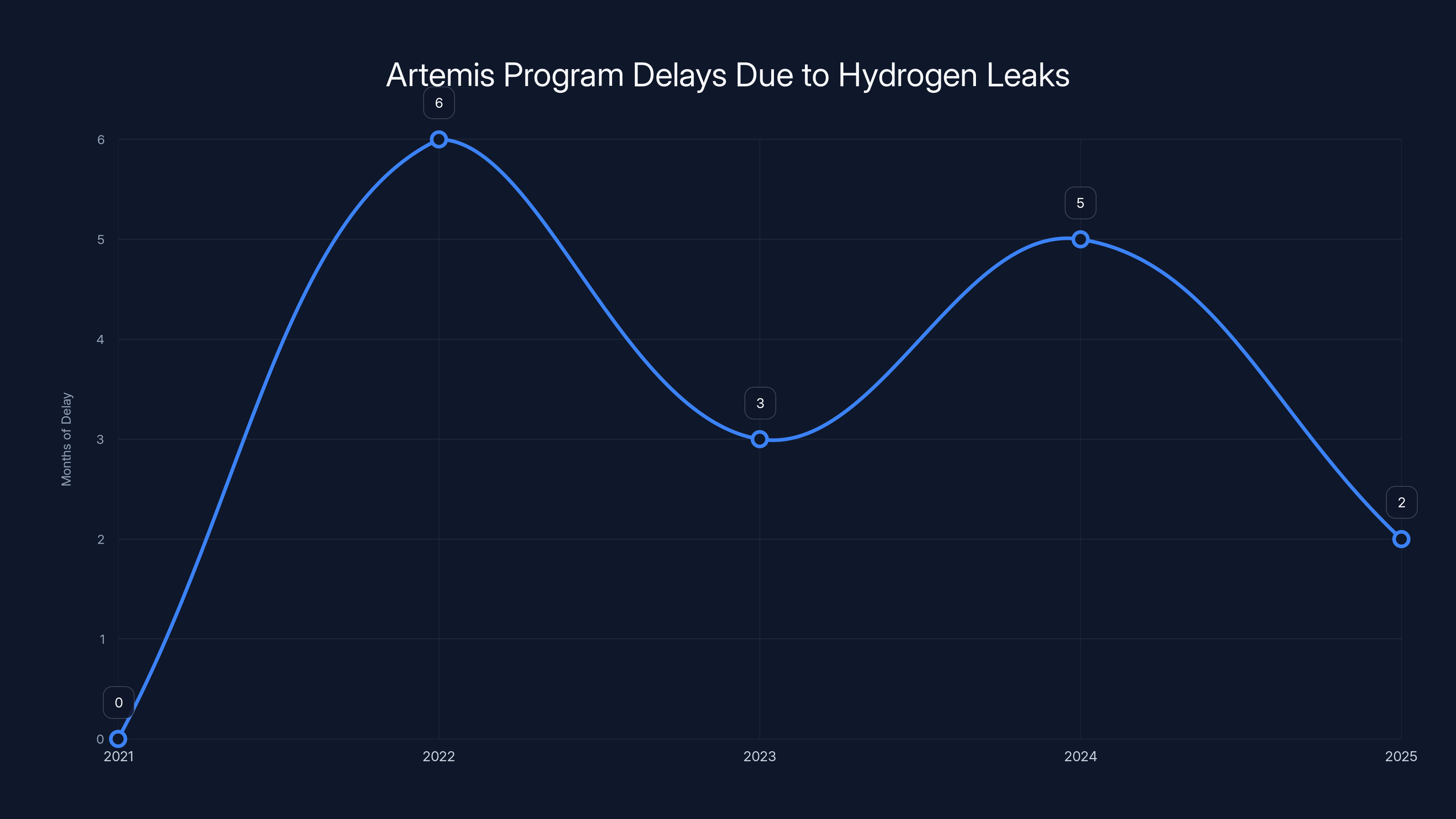

- NASA's SLS faces continued hydrogen leak issues during Artemis II fueling tests, pushing the mission launch to March and beyond

- Firefly Aerospace prepares for return to flight after two catastrophic failures (first stage explosion in April, booster destruction in September)

- China testing next-generation crew spacecraft with planned abort system tests potentially launching in February

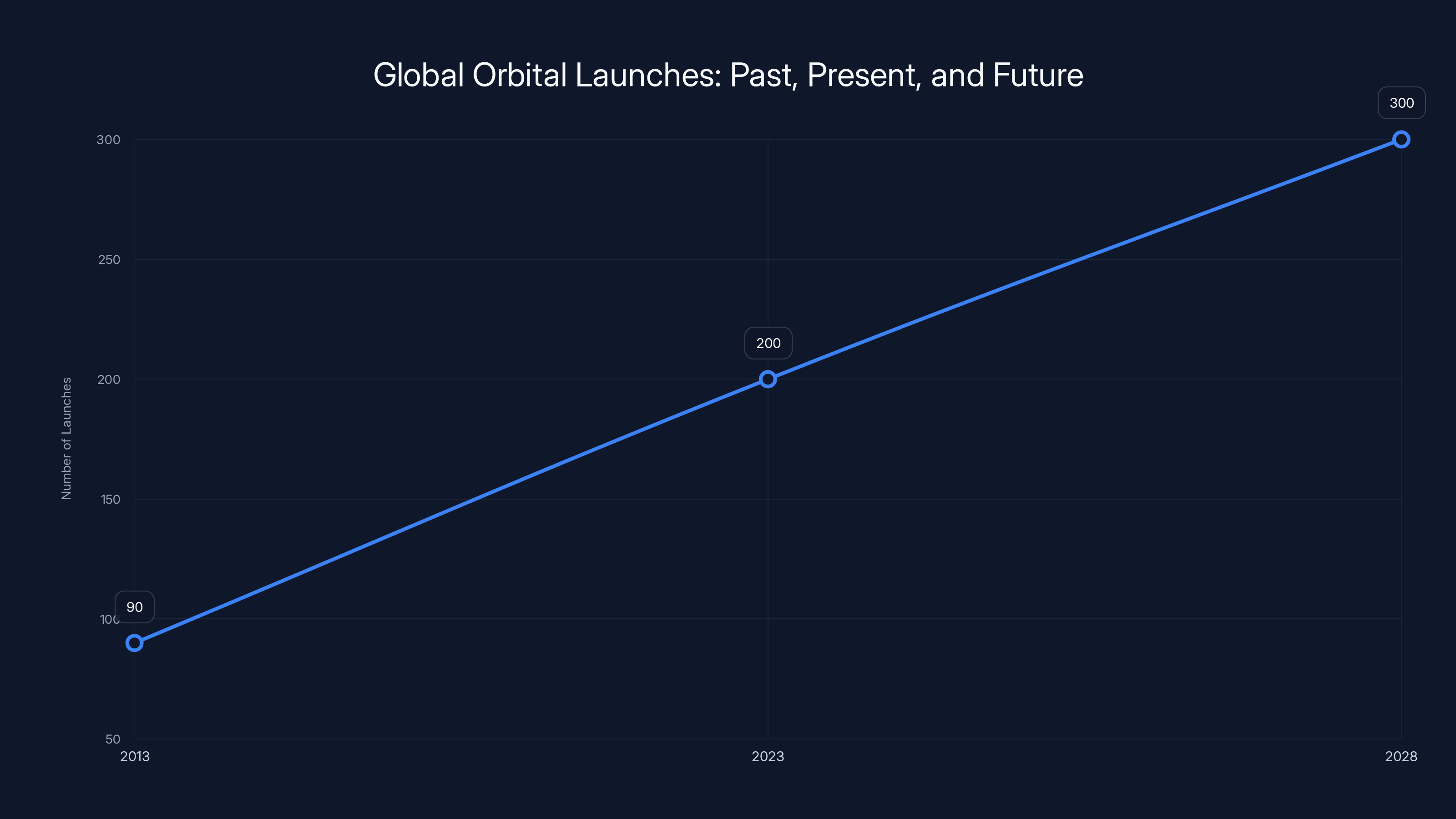

The number of global orbital launches is projected to increase from around 90 in 2013 to over 300 by 2028, driven by the growing demand for satellite deployment and space missions (Estimated data).

Understanding the Falcon 9 Upper Stage Anomaly

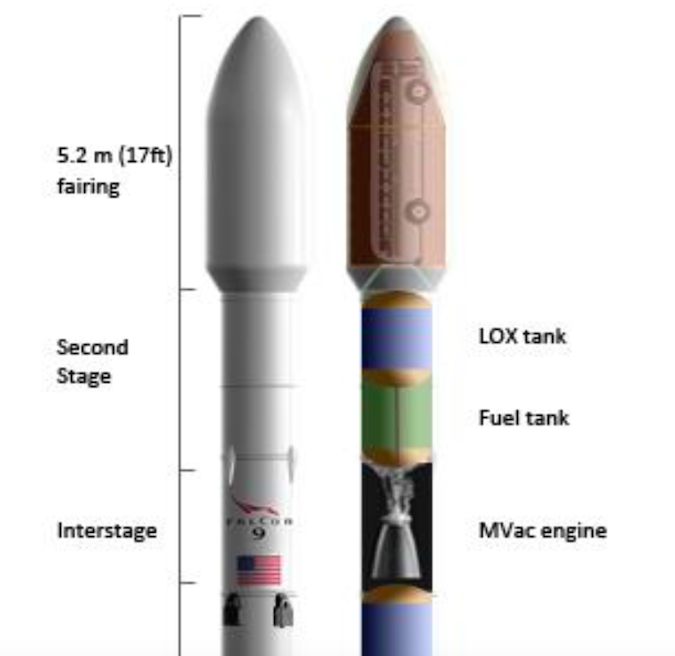

The Falcon 9 has two stages: the first stage, which gets you to the edge of space and comes back for a landing; and the second stage, which takes over once the booster separates and carries your payload to orbit. The second stage is where things get delicate. It doesn't land. It either stays in orbit to deploy cargo over multiple firings, or it performs a controlled deorbit burn—a precisely timed engine firing that kills enough velocity for the stage to fall back through the atmosphere and burn up.

On this particular flight, everything worked until the final act. The payload (25 Starlink satellites) was deployed perfectly. The second stage began preparing for its deorbit sequence. Then the engine refused to fire as commanded.

Why does this matter? Because a rocket upper stage sitting in low-Earth orbit is a problem. It'll eventually decay and reenter anyway—orbital mechanics guarantees that. But an uncontrolled reentry is unpredictable. You can't tell exactly when it'll happen or where it'll come down. For a company launching dozens of rockets per year, one errant upper stage is manageable. Systematic failures become a liability. Insurance rates climb. Customers get nervous. Regulators ask questions.

Space X was smart to pause operations immediately. The statement was direct: "Teams are reviewing data to determine root cause and corrective actions before returning to flight." That's the right call. Better to find the problem now than have it happen on a critical national security mission or a customer's expensive payload.

The question now is: what caused the malfunction? Possibilities include instrumentation failure (sensors gave bad readings), mechanical issues (a valve stuck or a pipe cracked), software glitches (the flight computer received corrupted data or had a logic error), or engine problems (combustion chamber malfunction, fuel line blockage, ignition system failure). Each has different implications for how long the fix takes.

Space X has faced second-stage anomalies before. In 2016, a Falcon 9 exploded on the launchpad during fueling operations—the Amos-6 incident. That took weeks to investigate and understand. But Space X also has something most aerospace companies don't: institutional knowledge from launching frequently. When you launch 60+ times per year instead of 5-10 times per year, you encounter more failure modes, faster. You build expertise. You iterate.

Still, pausing launches in early February meant disrupting a full manifest. A Starlink launch from Florida's Kennedy Space Center that was scheduled for later that week got postponed. The flight operators moved the payload fairing (the nose cone protecting the satellites) from the launchpad back to the hangar. That's logistical work—moving multi-ton hardware, updating launch schedules, notifying customers.

But here's what's remarkable: Space X has built so much margin into its operations that one pause doesn't cascade into catastrophe. The company operates multiple launch facilities simultaneously (Vandenberg in California, Kennedy in Florida). Multiple booster cores are in various stages of refurbishment. The Falcon 9 production pipeline is designed for high volume. This is the infrastructure advantage of routine spaceflight—when one mission stumbles, the next one doesn't have to wait weeks or months for investigation.

The broader question is whether this incident signals something systemic or just random bad luck. Rocket engineering is probabilistic. Every component has a failure rate. Every system has redundancies. But redundancies themselves can fail. Until Space X releases its findings (if it does publicly), we're in speculation territory. But what we know is this: the company had the discipline to stop, investigate, and methodically work through the problem. That's exactly how the aerospace industry stays safe.

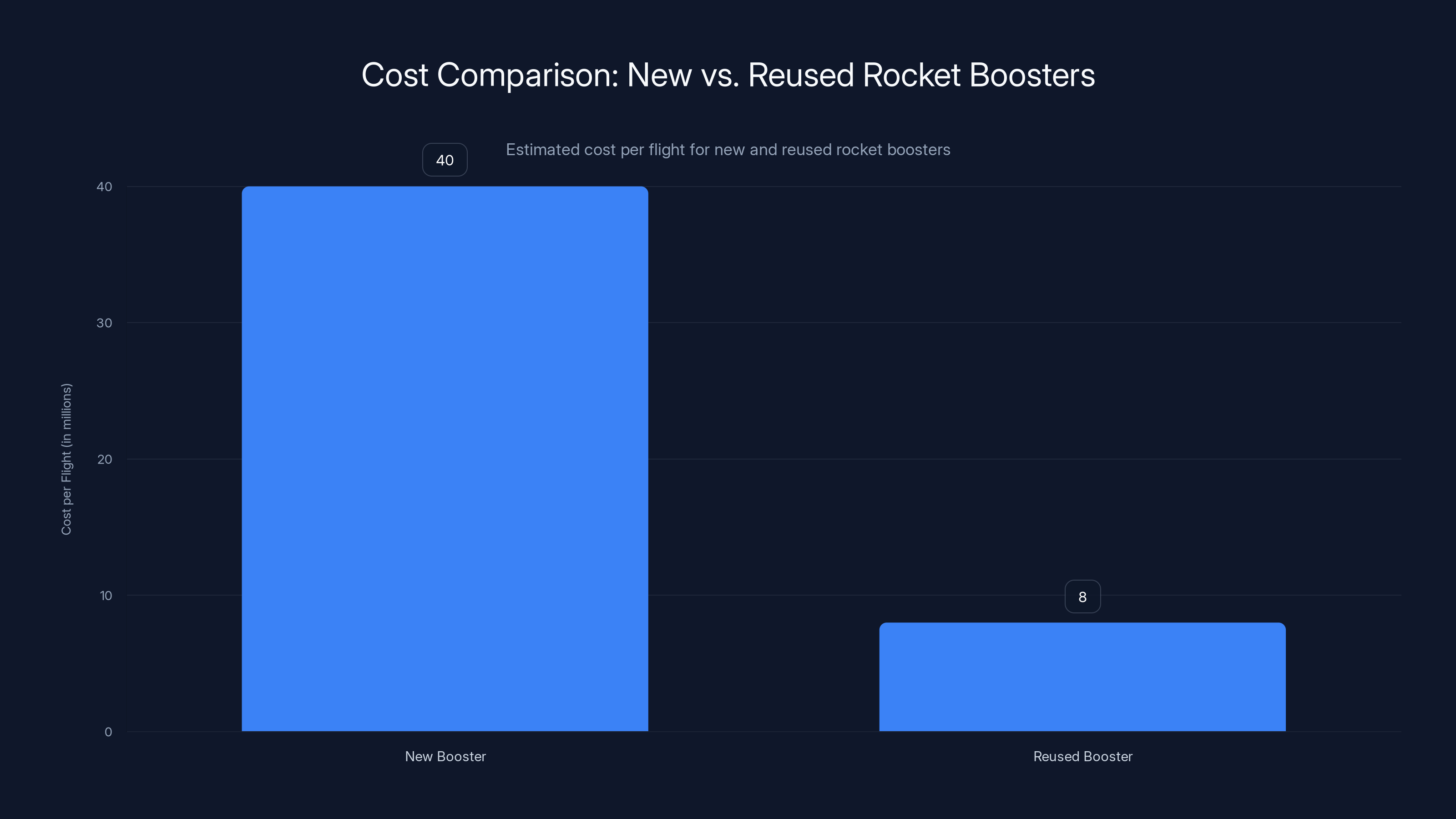

Reused rocket boosters reduce the cost per flight by approximately 5 times compared to new boosters, offering significant economic advantages. (Estimated data)

Amazon's Confidence Vote: 10 New Space X Launches

Amid the pause and investigation, Space X received a vote of confidence that speaks volumes. Amazon announced it had booked an additional 10 launches with Space X, continuing the company's multi-year strategy to build out its Kuiper satellite internet constellation. Coming during a moment when Space X's launch cadence was temporarily halted, the announcement feels almost deliberately timed.

Amazon's statement was explicit about the why: "near-term shortage in launch capacity." That's not hyperbole. The company needs to deploy thousands of satellites to compete with Space X's Starlink and other constellation projects. The global launch manifest is packed. Every available rocket is booked years in advance. When Amazon looks at available launch capacity, it sees a bottleneck.

This is the inverse of the problem from a decade ago, when too many rockets were being built for too few payloads. The Space X Falcon 9 changed that equation. By making launch cheaper and more frequent, Space X increased demand. Now everyone wants to launch. Governments want to launch reconnaissance and navigation satellites. Commercial companies want to launch internet constellations, Earth observation networks, and deep-space probes. University researchers want to launch experiments. The queue is real.

Amazon's decision to stick with Space X despite the temporary pause is telling. The company could have diversified more, contracted with Blue Origin's New Glenn or Arianespace's Ariane 6 or other providers. Instead, it doubled down on Space X. That suggests extreme confidence in the company's ability to solve the problem quickly and return to operations.

The financial implications are significant. At somewhere in the neighborhood of

Beyond Kuiper, Amazon is also using Space X launches for Project Kuiper ground segment testing and for deploying satellites for other divisions of the company. The breadth of Amazon's payload diversity with Space X shows the depth of the commercial partnership. It's not one project. It's an entire company's space infrastructure being built on Falcon 9 launches.

The timing of this announcement also highlights something important about market dynamics in commercial spaceflight. When demand exceeds supply dramatically, even a temporary outage from your preferred provider doesn't change the calculus. Amazon needs launch capacity more than it needs to make a political statement. Space X still offers the best combination of capacity, reliability, and cost. The pause is a speed bump, not a dealbreaker.

What's happening here is market maturation. Fifteen years ago, the question was whether commercial spaceflight could even work. Today, the question is how fast the industry can scale to meet astronomical (pun intended) demand. Amazon's 10-launch commitment is a data point in a much larger trend: satellite internet is becoming infrastructure, and infrastructure requires reliable, affordable launch services. Space X has become essential to that infrastructure. A single malfunction, taken seriously and investigated properly, doesn't change that fundamental reality.

NASA's Artemis II Nightmare: The SLS Hydrogen Leak Saga Continues

While Space X was investigating a single upper-stage anomaly, NASA was wrestling with a problem that's been haunting its Space Launch System since the program's inception: hydrogen leaks in the fuel loading system.

The problem cropped up during a fueling test on Monday for Artemis II, NASA's second crewed lunar mission. During the test, cryogenic hydrogen (one of the propellants needed to launch the rocket) began leaking from the ground systems. NASA engineers have seen this movie before. In 2022, similar leaks delayed the Artemis I launch by months. The agency thought it had fixed the issue. Apparently not.

This is where the SLS's low launch cadence becomes a liability rather than a feature. The Space Shuttle flew nearly every month at its peak. The SLS has flown once in over a decade. Every launch is rare enough that the ground support infrastructure gets rusty. Procedures that haven't been executed in years get pulled from filing cabinets. Teams rotate. Institutional memory fades. When you finally do launch, decades of accumulated issues in the pad's infrastructure surface.

NASA's colleague Eric Berger reported extensively on this dynamic: every SLS fueling test becomes an unplanned experiment because you simply haven't done it recently enough to have smooth operations. The rocket is solid. The hardware is built correctly. But the ecosystem around it—the launch pad, the ground support equipment, the procedures, the training—all of that atrophies when you only fly once every few years.

The hydrogen leaks are particularly frustrating because they're not mysterious. NASA knows what's causing them: the fueling line connections aren't perfectly sealed. Fix: redesign the quick-disconnects. But redesigning and manufacturing new hardware, then certifying that it works, then installing it—that all takes time. Months of time. And Artemis II was already delayed repeatedly.

The updated timeline: another fueling test in the coming weeks after troubleshooting. If that succeeds, Artemis II launches in March. If it doesn't, the mission slips further. Meanwhile, Space X's Starship—which doesn't exist in NASA's formal manifest but represents the most radical transformation in launch vehicle design in decades—continues testing and iterating on a much faster schedule.

The broader context is important here. The SLS was designed to be built once, then fly multiple times. Instead, it became a monument to one-at-a-time engineering. Every rocket is essentially a custom build. The supply chain is global and complex. Components that should be interchangeable sometimes aren't. Tolerances that should be tight get loose. When you're only flying once every two years, you lose the economies of scale that make spaceflight cheaper and faster.

NASA isn't unaware of these problems. The agency has been working on streamlining SLS operations, reducing per-flight costs, and accelerating the cadence. But those changes take time to implement. For Artemis II, the agency is working with what it has: a powerful rocket that works but is surrounded by ground infrastructure that struggles with the cadence.

The hydrogen leak issue is solvable. There's no physics problem here, no fundamental design flaw. It's engineering. Tweaky engineering that requires attention to detail, proper testing, and adequate time to troubleshoot. NASA will fix it. But every delay pushes back the next crewed lunar landing by another month. And in the accelerating space race—with China rapidly advancing its lunar program and international partnerships reshaping the competitive landscape—every month matters.

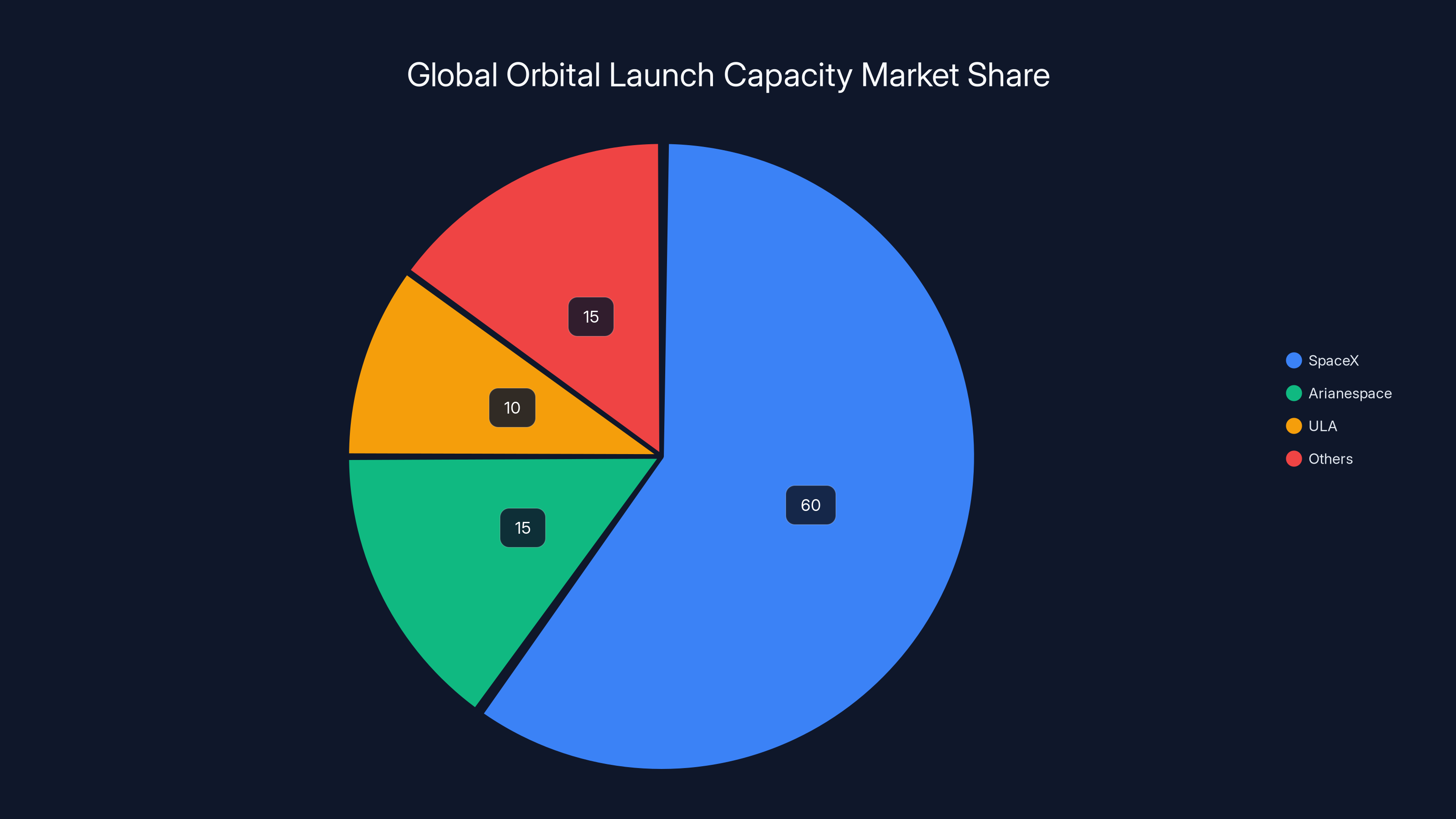

SpaceX controls approximately 60% of the global orbital launch capacity, significantly impacting the industry when operations pause. Estimated data.

Blue Origin's Stunning Strategic Pivot: New Shepard Pause

In late January, Blue Origin made an announcement that shocked its own employees: the company was pausing the New Shepard program for the next two years. In corporate speak, a "pause" often means "permanent cancellation." And based on the reasoning Blue Origin provided, this looks like exactly that.

New Shepard has been flying since 2015—a decade of continuous operations. The program has completed 38 launches and 36 landings, never suffering a mission-ending failure (one booster crashed during landing, but the capsule and crew escaped safely). In its existence, New Shepard flew 98 people to space and launched over 200 scientific and research payloads. By any measure, it was a successful program.

But success in spaceflight isn't measured purely by mission reliability. It's measured by strategic value and resource allocation. And Blue Origin's leadership decided New Shepard no longer represented the best use of the company's people and resources.

The decision came from CEO Dave Limp in an internal email on January 30. His reasoning: Blue Origin needs to accelerate development of its New Glenn rocket and lunar capabilities to participate in America's goal of returning to the Moon and establishing a permanent sustained lunar presence. In other words, Blue Origin is placing its strategic bet on heavy-lift rockets and deep-space infrastructure, not on suborbital tourism.

That's a bold decision. Suborbital space tourism is profitable. People pay $450,000 per seat to experience a few minutes of weightlessness and see Earth from space. That's real revenue. It's a business that works. But from Blue Origin's perspective, it's also a business that doesn't advance the company's core mission: becoming a major player in orbital spaceflight, lunar operations, and beyond.

The cancellation did surprise Blue Origin employees, judging by media reports. The company had just flown a mission a week before the announcement—six people on a suborbital joyride. Then the next week, the program was paused. That kind of abruptness creates organizational uncertainty. Teams get reassigned. Projects get shelved. Institutional knowledge starts leaking as people look for jobs elsewhere.

But from a strategic standpoint, it makes sense. Blue Origin is owned by Jeff Bezos, one of the wealthiest people on Earth. His company can afford to place long-term strategic bets that don't show immediate returns. New Shepard was generating revenue but not advancing the company's position in the competitive space industry. New Glenn and lunar capabilities do. So Bezos and Limp made the hard choice: sunset one program to accelerate another.

This also signals something about market expectations. Blue Origin could have continued New Shepard indefinitely, milking revenue from wealthy space tourists. But the company's leadership apparently believes the real action—the strategic prize—is elsewhere. That's a rational decision from leadership that sees the landscape clearly: suborbital tourism is a niche market, profitable but limited. Orbital spaceflight and deep-space operations are where the future lies.

New Shepard's legacy is secure. The program proved that suborbital spaceflight is commercially viable, that rocket reusability works for booster vehicles, and that human spaceflight can be routine and safe. Those achievements matter. But for Blue Origin in 2025, they're not enough. The company wants to win at the bigger game.

Firefly Aerospace's Resurrection: The Path Back to Flight

While Space X investigates anomalies and NASA debugs ground infrastructure, Firefly Aerospace is doing something harder: coming back from catastrophic failure. And it's happening at an impressive pace.

Firefly's Alpha rocket has had a brutal eighteen months. In April 2024, an Alpha first stage exploded during flight—literally blew apart moments after separating from the second stage. The blast damaged the upper stage and prevented deployment of a small commercial satellite. It was a bad day. But Firefly kept going. The company announced that the next Alpha flight would be a test mission with no customer payloads, effectively a recovery flight.

Then in September, during a preflight test in Texas, the booster for that next Alpha mission was destroyed during ground testing. That's not a flight failure—it's worse. It means the damage was done before the rocket even got to the pad, revealing a fundamental problem in how the booster was being built or tested.

Two massive setbacks in five months. For a startup company, that's potentially company-ending. But Firefly is resilient, and now—in late January—the company was preparing for another attempt. The Alpha rocket shipped to Vandenberg Space Force Base in California, and on January 29, video showed the rocket rolling to the launch pad for static fire testing.

Static fire is exactly what it sounds like: you tether the rocket to the pad and ignite the engines to verify they work before actually launching. It's a critical test. If the engines don't fire reliably on the pad when you can shut them down immediately, they definitely won't be safe to fly vertically. This particular test was called the "Stairway to Seven" mission, because it's a stepping stone toward Firefly's goal of seven successful launches.

What's remarkable about Firefly's situation is the timeline. From catastrophic booster failure in September to static fire testing in late January is approximately four months. That's an aggressive schedule for investigating what went wrong, redesigning components, manufacturing new hardware, and preparing for the next test. For context, Space X might move at a similar pace, but Space X is an established company with enormous manufacturing capacity and institutional experience. Firefly is younger, leaner, and still building that infrastructure.

The company also announced that the Stairway to Seven mission would use an upgraded "Block II" version of the Alpha rocket, incorporating lessons learned from previous failures. This is the textbook approach to rocket development: crash, learn, iterate, improve. The cadence is painful—nobody wants failures—but it's the proven path to building reliable vehicles.

Alpha is a 1-ton-class rocket, not a giant. It's designed to launch small satellites and payloads on dedicated missions. It competes in a market segment that includes rockets like Rocket Lab's Electron and ABL Space Systems' RS1. The market for dedicated small launch is real and growing as companies want their own rockets instead of sharing rides on larger vehicles.

For Firefly, getting back to flight and proving the system works is existential. The company has investment backing, but investors have patience limits. Demonstration that the rocket can fly successfully and on a reasonable testing cadence is essential for securing additional funding and customer contracts. The Stairway to Seven mission represents that demonstration.

The broader context is that small-lift launch is becoming more competitive and more important. Companies like Planet Labs, Spire Global, and others depend on frequent, affordable access to space. Rocket Lab has proven there's a viable market. Now multiple companies are trying to capture pieces of that market. Firefly's Alpha is one of several contenders. Execution matters. Firefly needs to demonstrate that it can execute reliably.

Amazon's commitment to 10 new SpaceX launches is estimated to cost between $600-700 million, indicating strong confidence in SpaceX's capabilities. Estimated data.

China's Next-Generation Crew Spacecraft: The Mengzhou Test Campaign

While American companies navigate their own challenges, China is advancing its human spaceflight program with impressive pace. The government announced that it was preparing to test the Mengzhou spacecraft, its next-generation crew vehicle, with a planned in-flight abort system test potentially launching in early February from the Wenchang spaceport on Hainan Island.

Mengzhou is significant because it represents China's strategy for both near-term operations and long-term lunar ambitions. In the near term, Mengzhou will eventually replace the Shenzhou spacecraft for routine trips to the Tiangong space station. Shenzhou has worked well—it's based on Soviet-era design but has been refined and improved over two decades of Chinese spaceflight. But Mengzhou is purpose-built for what China wants to do next: carry crews to the Moon.

The in-flight abort test is a critical milestone. Abort system testing proves that if something goes catastrophically wrong during launch, the crew capsule can separate from the rocket and bring astronauts safely back to Earth. Every human-rated spacecraft needs this capability tested and verified before carrying crews. It's non-negotiable safety engineering.

The test hardware revealed in images from Wenchang showed a test capsule being hoisted onto a booster stage. This particular booster is a subscale version of China's Long March 10 rocket—a partially reusable, human-rated launcher under development specifically for lunar missions. So this test serves double duty: it qualifies the Mengzhou abort system, and it gathers flight data on the Long March 10 hardware.

This is efficient spacecraft development. Each test flight accomplishes multiple objectives. China's space program has learned from decades of international cooperation and observation. The flight test program is methodical and well-planned.

Why does China's progress matter to American space policy? Because China is executing on human lunar missions with extraordinary focus and resources. The U. S. Artemis program aims to return Americans to the Moon, but the timeline keeps slipping. China's timeline is clearer, and the political will is evident. If China lands humans on the Moon before the U. S. returns, it becomes a geopolitical statement—not just about spaceflight capability but about technological leadership and systemic effectiveness.

Mengzhou's design philosophy reflects learning from both Soviet and American spacecraft. The capsule design is pragmatic and proven. The life support systems are robust. The avionics are modern. None of this is cutting-edge in the sense of untested technology, but it's cutting-edge in terms of integration and operational capability.

What's particularly interesting is China's willingness to test frequently and methodically. The agency has already conducted a pad abort test of Mengzhou's launch escape system. Now it's moving to in-flight abort testing. If that succeeds, orbital tests follow, then uncrewed missions, then crewed flights. This is the proven development sequence. China is following it.

The implications extend beyond lunar missions. A spacecraft designed to reliably carry humans to the Moon is a spacecraft that can reliably carry humans anywhere in cislunar space. Once Mengzhou is operational, China can conduct extended-duration missions, visit space stations, potentially refuel and resupply orbiting vehicles. The capability set expands dramatically with each successful test.

For American space planners and policymakers, China's progress on next-generation crew vehicles is a wake-up call. The window for American dominance in crewed deep-space exploration is closing. The U. S. needs to move faster or risk ceding leadership in the most prestigious domain of spaceflight: human exploration beyond Earth orbit.

The Global Launch Capacity Crisis: Why Demand Is Outpacing Supply

Beneath all these individual stories—Space X's pause, NASA's delays, Blue Origin's pivot, Firefly's recovery, China's progress—lies a fundamental market dynamic that's reshaping the space industry: demand for launch capacity is exploding while supply, despite rapid increases, still can't keep pace.

Consider the numbers. A decade ago, maybe 80-100 orbital launches happened per year globally. Today that number is approaching 200. Within another five years, industry analysts expect 300+ launches per year. That's exponential growth driven by mega-constellations (Starlink, Kuiper, One Web), government missions (national security satellites, scientific missions), commercial ventures (Earth observation, communications), and emerging markets (space-based manufacturing, orbital tourism infrastructure).

Space X alone is launching at a rate approaching 60+ per year now. That's a mind-bending cadence that would have been impossible a decade ago. But even at 60 launches per year, Space X can't meet total global demand. Arianespace, United Launch Alliance, Rocket Lab, and other providers are all operating at full capacity, and new providers are still coming online.

What does a capacity shortage mean in practice? It means customers have to wait. Amazon can't deploy Kuiper satellites as fast as it wants. Governments can't launch reconnaissance satellites on their preferred timelines. Commercial companies can't launch constellation deployments at the pace that maximizes their competitive advantage. Everyone is constrained by the availability of launch vehicles.

This creates a multi-layered market opportunity. Established launch providers (Space X, United Launch Alliance) have full manifests years in advance. Emerging providers (Firefly, ABL Space, Relativity Space) fight for whatever contract slots remain. Customers negotiate for priority, pay premium prices, or accept delays.

From Space X's perspective, this abundance of demand is both opportunity and risk. Opportunity because the company can charge premium prices for dedicated missions and negotiate favorable terms with mega-customers like Amazon. Risk because if Space X has operational pauses—investigating upper-stage anomalies, for example—the company is walking away from millions of dollars in revenue and potentially disappointing customers at a time when those customers are most frustrated with tight capacity.

But there's a second-order effect: this capacity constraint is actually accelerating innovation in the industry. Companies that can't book flights are forced to build better vehicles, cheaper rockets, or more efficient payloads. ULA is developing Vulcan, Blue Origin is developing New Glenn, Arianespace is developing Ariane 6, and a dozen smaller companies are developing their own vehicles. Within 5-10 years, the supply situation should ease somewhat as new rockets come online.

The tragedy is that capacity constraints slow down progress in space. Scientific missions get delayed. Commercial ventures postpone revenue-generating launches. National security missions compete with civilian missions for limited slots. The entire ecosystem grinds against capacity limits.

Solving this problem requires either more rocket launches or fewer desired missions. Since the demand isn't going away, the solution is obviously more rockets. That means more development, more testing, more investment, and more operational infrastructure. Every failed test (like Firefly's booster destruction in September) delays the addition of new capacity to the market. Every anomaly that causes an operational pause (like Space X's upper-stage issue) reduces the supply of launch services in the near term.

This is the underlying tension playing out across all the stories of early 2025: the space industry is growing too fast to be comfortable, but not growing fast enough to meet demand. That tension drives innovation, drives investment, and occasionally drives failures. Managing that tension effectively separates winners from losers.

SpaceX's Falcon 9 boasts a near 99% success rate, but the recent upper stage malfunction highlights the challenges in spaceflight operations. Estimated data based on typical launch statistics.

The Economics of Rocket Recovery and Reusability

One thread connecting many of these stories is the dramatic reduction in launch costs that reusable rockets enable. Understanding this economics is essential to understanding why Space X dominates the market and why other companies are struggling to compete.

Before reusability, every rocket was essentially a single-use vehicle. You built it, you flew it, it crashed into the ocean, you recycled the scrap. Each launch required building a completely new vehicle from scratch. For a company like United Launch Alliance, an Atlas V or Delta IV rocket cost $200-500 million per flight when fully loaded with development, manufacturing, and operational costs. That enormous expense meant launch was only accessible to governments and the wealthiest corporations.

Space X changed this equation by making the first stage reusable. The Falcon 9's first stage lands itself, gets inspected, gets refueled, and launches again. After 10+ reuses, the per-flight cost drops dramatically. A reused booster might cost

Here's the math in simplified form. Let's say a Falcon 9 booster costs

That's not quite

But reusability only works if you actually reuse your rockets. That requires reliability. If a booster crashes on landing even 5% of the time, you lose money. If the booster degrades from flight to flight and needs expensive refurbishment, the economics deteriorate. Space X solved both problems through design, testing, and operational discipline. Their boosters reliably land. Their refurbishment processes are efficient.

Other companies are trying to compete on this front. Blue Origin's New Shepard uses a fully reusable suborbital vehicle, but suborbital doesn't generate the same revenue as orbital launches. ULA's new Vulcan rocket is being designed with a reusable first stage, but it's not operational yet. Relativity Space is trying to use 3D printing to reduce manufacturing costs (a different approach to the same goal: lower per-launch costs). None have achieved Space X's combination of reliability, reusability, and operational volume.

The consequence is that Space X can undercut competitors on price while still maintaining profitability. A ULA launch might cost

And here's the kicker: as Space X launches more, the company gets better at recovery and refurbishment. Each booster landing generates operational data. Each refurbishment cycle reveals optimization opportunities. The company's margins improve with volume and experience. That's a competitive advantage that compounds over time.

Firefly and other emerging companies can compete in the small-lift market or by going after very specific niches where Space X doesn't play. But in the general orbital launch market for mid-to-heavy payloads, Space X's reusability advantage is nearly insurmountable. That's why Blue Origin pivoted away from New Shepard (which wasn't generating the volume needed to make economics work) and why ULA is focused on national security missions where cheaper isn't the primary competitive factor.

The economics also explain why Amazon's decision to book 10 more Space X launches is rational even during a launch pause. Space X's pricing is simply better than alternatives. That advantage persists even when the company has temporary operational pauses. The customer needs to move payloads to orbit, and the cheapest way to do so is still via Falcon 9.

Safety Culture in Modern Spaceflight: When "Failure to Launch" Is the Right Call

One aspect of the recent events worth highlighting is how different the modern space industry's approach to safety is from earlier generations. When Space X discovered the upper-stage anomaly, the company didn't just write a report and move on. It paused operations. That's expensive. That costs revenue. That disappoints customers. But it's the right call.

This represents a profound shift in how spaceflight operates. In the Space Shuttle era, the pressure to keep flying was constant. Political pressure, budget pressure, schedule pressure—all pushed toward "just launch." That culture contributed to two tragic losses: Challenger in 1986 and Columbia in 2003. The NASA accidents investigation boards afterward identified schedule pressure and normalization of deviation as key factors. Basically, the organization got used to accepting risk.

Modern commercial spaceflight companies learned from that history. They understand that a crash is catastrophically expensive. Insurance rates explode. Customers flee. Regulatory approval becomes nearly impossible. It's far cheaper to pause operations for weeks, investigate a problem properly, fix it thoroughly, and resume—than it is to launch with an unresolved anomaly and suffer a catastrophic failure.

This is rational risk management, not excessive caution. Space X pauses operations when anomalies occur because the company learned that being thorough now prevents disasters later. NASA pauses fueling tests on the SLS because hydrogen leaks are a real problem that needs solving, not a scheduling inconvenience.

The flip side is that companies can use "safety" as cover for poor execution. "We're investigating," is a good reason to delay a launch. But it can also be used cynically if the actual investigation is cursory. The key is transparency and credibility. Space X has built credibility through consistent follow-through: when they identify a problem, they fix it, and they tell customers and the public what they found.

Firefly is currently in the delicate position of trying to rebuild credibility after two catastrophic failures. Every test success moves the needle. Every delay erodes confidence. The company has to demonstrate that the problems have been identified and addressed, not just that enough time has passed to try again.

China's methodical approach to Mengzhou testing reflects the same safety culture: test thoroughly, verify each stage, don't move forward until you're confident. This is different from the old Soviet approach, which favored speed over absolute certainty and occasionally resulted in disasters.

What's happened in the modern era is that failure is increasingly seen as valuable data, provided the failure is investigated thoroughly and learned from. When Firefly's booster exploded in April 2024, that was bad news for the company, bad news for its investors, and bad news for the payload customer. But it was also an expensive education in what doesn't work. The company is now using that knowledge to improve. That's the ideal failure scenario: you learn something that improves future performance.

The flip side of safety culture is speed. If you over-investigate every anomaly, you move slowly. Teams get paralyzed. Decision-making becomes glacial. This is somewhat the problem NASA faces with the SLS: the system is so expensive and so risky that every decision gets scrutinized to death. The result is ponderous progress.

Space X has somehow threaded the needle: the company moves fast (60+ launches per year) while maintaining a healthy respect for safety (pausing when anomalies arise). It's partly due to the Falcon 9 being a relatively simple rocket compared to the SLS, and partly due to leadership that trusts engineers to make good decisions. That combination is rare in aerospace.

Estimated data shows a fluctuating delay pattern in the Artemis program due to recurring hydrogen leaks. The trend indicates ongoing challenges in resolving the issue.

Looking Ahead: The Competitive Landscape in 2025 and Beyond

The events of early 2025 paint a picture of an industry in transition. Space X remains dominant but has to maintain reliability while operating at unprecedented cadence. Amazon's confidence vote shows commercial mega-customers believe the space industry is essential to their future. Blue Origin is taking a patience play, betting that long-term investments in New Glenn and lunar capabilities will pay off. NASA's slower-moving programs are fighting against entropy and complexity. China is advancing steadily on human spaceflight capabilities. Smaller companies like Firefly are fighting for survival, trying to prove their concepts work reliably enough to justify customer investment.

Over the next year, we can expect to see:

Space X: Resolution of the upper-stage anomaly, return to full launch cadence, and continuing high-frequency operations from both coasts. The company will almost certainly break its previous launch record. Starship tests will continue. The company will push toward increasingly ambitious flight test objectives.

NASA: Artemis II finally launches, probably in mid-2025 or later. The mission will carry astronauts around the Moon and back—not landing, but important symbolically and operationally. The SLS will continue flying at its glacial cadence, limited by infrastructure constraints and cost.

Blue Origin: New Glenn continues development. The company remains relatively quiet publicly but is quietly advancing its lunar lander and deep-space infrastructure capabilities. New Shepard stays paused.

Firefly and Other Emerging Providers: Some will succeed, demonstrating reliable vehicles that command customer loyalty. Others will fail—perhaps spectacularly. The market will consolidate around a handful of viable providers.

China: Mengzhou testing continues. By mid-2025, expect crewed missions to Tiangong to use the new spacecraft. Lunar missions will accelerate. China will likely announce an ambitious timeline for crewed Moon landing, probably in the 2028-2030 timeframe.

Launch Capacity: Remains tight. New rockets come online slowly (Vulcan delays, Ariane 6 delays). Demand continues growing. Pricing for launch services remains premium.

The longer-term trajectory is clear: spaceflight is becoming infrastructure. It's no longer a spectacular achievement to put a satellite in orbit. It's becoming routine, taken for granted by commercial customers and governments alike. The companies that can operate routinely, safely, and affordably will thrive. Those that can't will fade.

Space X has the advantage right now, but the advantage isn't permanent. If the company stumbles, if reliability falters, if execution fails, competitors will seize the opportunity. That's why pausing operations to investigate an anomaly is so important—it prevents small problems from becoming existential ones.

The space industry is moving faster, scaling larger, and becoming more critical to human civilization than ever before. That's exciting. It's also risky. Every failure teaches lessons. Every success validates approaches. The industry is learning in real time how to do spaceflight at scale. That's what makes 2025 such a fascinating inflection point.

FAQ

What caused the Space X Falcon 9 upper stage malfunction?

The exact cause hasn't been publicly disclosed as Space X teams continue investigating. The upper stage failed to execute a controlled deorbit burn, which is a precision engine firing designed to guide the rocket's second stage back through the atmosphere. Possible causes include instrumentation failure, mechanical issues, software glitches, or engine problems, but Space X's official statement only indicated an "off-nominal condition" during the deorbit preparation phase. The company halted subsequent launches pending investigation and corrective actions.

How does Space X's pause in launches affect the space industry?

When Space X pauses operations even temporarily, it ripples across the entire commercial space industry because the company controls roughly 60% of global orbital launch capacity. Customers with scheduled missions experience delays. Satellite deployment timelines slip. The tight supply-demand balance in launch capacity becomes even more strained. However, other providers like Arianespace, ULA, and smaller companies can absorb some overflow demand. Amazon's commitment of 10 additional launches to Space X despite the pause shows confidence that the issue will be resolved quickly without long-term impact.

Why is NASA's Space Launch System experiencing recurring hydrogen leak problems?

The SLS ground support infrastructure, particularly the fueling systems and quick-disconnect valves, was built during an era when spaceflight cadence was much lower. Hydrogen leaks indicate that sealing connections between the launch pad equipment and the rocket aren't perfect. Because NASA only launches the SLS every few years (unlike Space X's 60+ annual launches), the ground infrastructure doesn't get the routine maintenance and operational refinement that comes from frequent use. Additionally, complex systems deteriorate when not regularly exercised. NASA is addressing the issue through redesigned quick-disconnects and improved procedures, but solutions take time to implement and test.

What is China's Mengzhou spacecraft and why does it matter?

Mengzhou is China's next-generation human-rated spacecraft designed to carry crews to orbit and eventually to the Moon. It will eventually replace the aging Shenzhou spacecraft for missions to the Tiangong space station and serve as China's primary crewed vehicle for lunar exploration. The spacecraft is significant because it demonstrates China's commitment to independent human spaceflight capability and autonomous lunar exploration capability, potentially advancing a crewed Moon landing before the U. S. Artemis program returns astronauts to the lunar surface.

Why did Blue Origin pause the New Shepard program?

Blue Origin's CEO Dave Limp stated that the company needed to redirect resources toward New Glenn rocket development and lunar capabilities to participate in America's goal of returning to the Moon with a sustained presence. While New Shepard was a successful and profitable suborbital space tourism program, it doesn't advance Blue Origin's core strategic objectives in orbital spaceflight and deep-space operations. From a resource allocation perspective, New Glenn and lunar systems represent greater long-term value than continuing suborbital tourism flights.

What is the global launch capacity shortage and why is it a problem?

Demand for orbital launches has grown exponentially with the rise of mega-constellations like Starlink and Kuiper, Earth observation networks, government missions, and commercial ventures. While Space X has dramatically increased launch cadence to 60+ per year, global demand is approaching 200+ launches annually. This mismatch means customers face delays, can't deploy satellites on their preferred timelines, and have limited negotiating power on pricing. The shortage drives up costs, slows down space-based services, and creates competitive pressure for companies to develop new launch vehicles.

How does rocket booster reusability affect launch economics?

Reusable rockets like the Falcon 9 reduce per-flight costs by amortizing manufacturing costs across multiple missions. A booster costing

What safety practices do modern spaceflight companies use to prevent failures?

Modern commercial spaceflight companies have adopted formal safety cultures learned from Space Shuttle accidents (Challenger and Columbia). Key practices include pausing operations when anomalies are discovered rather than pressing forward, conducting thorough root cause analysis before resuming flights, transparent communication with customers and the public about problems and solutions, and investment in testing and verification. This approach is more expensive short-term but prevents catastrophic failures that would be far more damaging to the company and industry.

How will the space industry evolve over the next 5-10 years?

Expect spaceflight to become increasingly routine and accessible as new rockets like Blue Origin's New Glenn, ULA's Vulcan, and others come online. Launch capacity will eventually exceed demand as the supply catches up, potentially reducing prices. Space X will likely maintain leadership through operational excellence and efficiency. China will advance its lunar program and may achieve crewed landing before U. S. Artemis missions. The industry will consolidate around a handful of major providers supplemented by specialists serving niche markets. Space-based services (satellite internet, Earth observation, manufacturing) will become essential infrastructure.

Why does frequency of rocket launches matter for reliability and safety?

When a company launches frequently (Space X's 60+ per year), every mission is an experiment that teaches lessons. The organization accumulates operational data, refines procedures, discovers and fixes issues at scale. Ground infrastructure gets regular exercise and maintenance. Teams stay sharp. In contrast, programs that launch infrequently (SLS every few years) lose institutional momentum, ground infrastructure deteriorates, procedures get rusty, and teams rotate. This explains why Space X achieves reliable operations at higher cadence than NASA—volume enables excellence.

Conclusion

The space industry in early 2025 presents a snapshot of rapid transformation. Space X paused operations to investigate an upper-stage anomaly, exactly the right response to an unexpected problem. Amazon booked 10 additional launches, voting confidence in Space X's ability to solve the issue and deliver launch capacity at a time when demand far exceeds supply. NASA continued struggling with hydrogen leak issues on the SLS, revealing the challenges of operating infrastructure designed for a cadence that's slower than reality. Blue Origin made a strategic decision to pause its successful suborbital space tourism program in favor of long-term bets on orbital rocket development and lunar capabilities. Firefly Aerospace clawed its way back from catastrophic failures, preparing for a critical return-to-flight test. And China advanced methodically toward human lunar missions with a new generation of spacecraft and rockets.

These individual stories interweave into a larger narrative: spaceflight has transitioned from engineering accomplishment to essential infrastructure. The constraints are real. Demand exceeds supply dramatically. Launch costs matter. Reliability matters more. The companies that execute efficiently will thrive. Those that can't will fade.

Space X remains the dominant force, but dominance in spaceflight is never permanent. Ariane had it once. The Soviet Union had it. Now Space X has it. In 10 years, who knows? The variables are technology (new rocket concepts that fundamentally change economics), geopolitics (government priorities and investment levels), and human execution (whether leaders and engineers make good decisions).

What's certain is that spaceflight will accelerate. The timeline from today until the first crewed Chinese lunar landing is probably shorter than skeptics expect. The timeline until Blue Origin's New Glenn is operational is probably longer than Blue Origin's official projections. Space X will break its launch records repeatedly. NASA's SLS will eventually fly humans to the Moon and back, even if the timeline stretches into 2026 or beyond.

The space industry isn't slowing down. It's accelerating, learning, iterating, and occasionally crashing spectacularly. That's how engineering progress happens. Pay attention to the companies that handle failures well—they're the ones that'll thrive for decades to come.

Additional Resources

For those wanting to dive deeper into any of these topics, tracking official announcements from Space X, NASA, Blue Origin, Firefly, and Chinese space agencies provides the most current information. Industry publications like Spaceflight Now, Space News, and The Verge cover these developments in depth. Academic resources on orbital mechanics, rocket propulsion, and spacecraft design are available through universities and professional engineering societies.

The story of spaceflight is being written in real time right now. If you're interested in technology, business, and human ambition, the space industry is where all three intersect in ways that are genuinely consequential. The next few years will be fascinating.

Key Takeaways

- SpaceX paused launches after Falcon 9 upper stage malfunction, demonstrating safety-first culture in modern commercial spaceflight

- Amazon committed 10 additional launches to SpaceX despite temporary pause, showing market confidence in company's problem-solving and capacity

- NASA's SLS faces recurring hydrogen leak issues due to low launch cadence, revealing infrastructure challenges with infrequent flight operations

- Booster reusability reduces per-flight manufacturing costs by 90%+, creating competitive pricing advantage that dominates global launch market

- Global launch demand approaching 200+ annual missions while supply remains constrained, creating premium pricing environment for launch services

- China advancing Mengzhou crew spacecraft systematically toward potential crewed lunar landing before U.S. Artemis program returns astronauts to Moon

- Blue Origin's pivot away from New Shepard suborbital tourism reflects strategic bet that orbital rocket development and lunar capabilities offer greater long-term value

Related Articles

- Blue Origin Pauses Space Tourism to Focus on Moon Missions [2025]

- Blue Origin Pauses Space Tourism for NASA Lunar Lander Development [2025]

- Elon Musk's Orbital Data Centers: The Future of AI Computing [2025]

- NASA Astronauts Can Now Bring Smartphones to the Moon [2025]

- Why NASA Finally Allows Astronauts to Bring iPhones to Space [2025]

- NASA's SLS Rocket Problem: Why the Costliest Booster Flies So Slowly [2025]

![SpaceX Starship Upper Stage Malfunction: Launch Recovery Timeline [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/spacex-starship-upper-stage-malfunction-launch-recovery-time/image-1-1770381597425.jpg)