Space X's 7,500 New Starlink Satellites: What It Means for Global Internet [2025]

Last Friday, the Federal Communications Commission handed Space X a massive win. The agency approved deployment of 7,500 additional second-generation Starlink satellites, pushing the total planned constellation to 15,000 units. On the surface, that's just a big number. But dig into what this actually means, and you're looking at something that could fundamentally reshape how billions of people access the internet.

Here's the thing: Space X didn't just get permission to launch more satellites. The FCC's decision unlocked something bigger. These new satellites can operate across five different frequency bands and provide direct-to-cell connectivity outside the United States, with supplemental coverage domestically. That's not minor. That's the infrastructure backbone for mobile communication in areas where terrestrial networks simply can't reach.

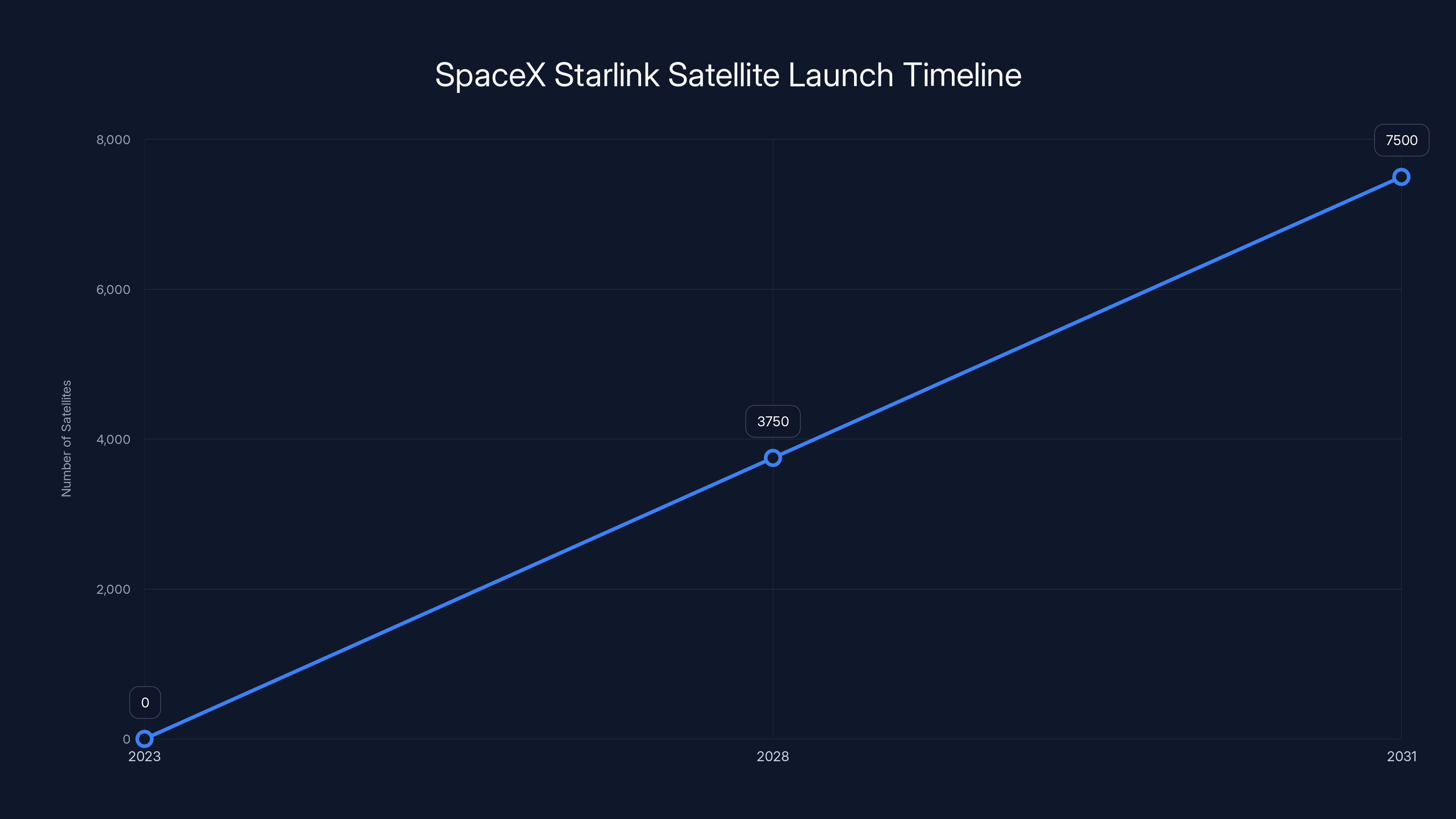

But there's a catch. Space X asked for 15,000 satellites and got approved for 7,500. The FCC deferred the remaining 14,988 proposed Gen 2 Starlink satellites, citing unspecified concerns. Space X has a timeline now: launch half the approved satellites by December 1, 2028, and the remaining half by December 2031. It's ambitious, but Space X has shown it can move fast when it counts.

Why does this matter to you? Because satellite internet is about to stop being a niche play for remote cabins and become a genuine alternative to terrestrial broadband. Speeds are improving. Latency is dropping. Coverage is expanding. The competitive pressure is forcing traditional ISPs to actually innovate. And the geopolitical implications are massive. Countries that can't build out fiber infrastructure now have a path to high-speed connectivity. That changes everything.

Let's break down what's actually happening here, why the FCC approved it, what challenges remain, and what comes next.

TL; DR

- FCC Approval: Space X got cleared to launch 7,500 new second-gen Starlink satellites, bringing the total to 15,000

- Frequency Expansion: New satellites operate across five frequency bands instead of current limitations

- Direct-to-Cell: Direct mobile connectivity coming to rural areas, with supplemental U. S. coverage

- Timeline: 50% must launch by December 2028, remaining 50% by December 2031

- Partial Victory: Space X requested 15,000 but got 7,500; remaining 14,988 are deferred pending FCC review

- Global Impact: This positions satellite internet as a legitimate competitor to fiber and 5G in underserved regions

SpaceX is required to launch 3,750 satellites by 2028 and the remaining 3,750 by 2031, as per FCC's regulatory deadlines.

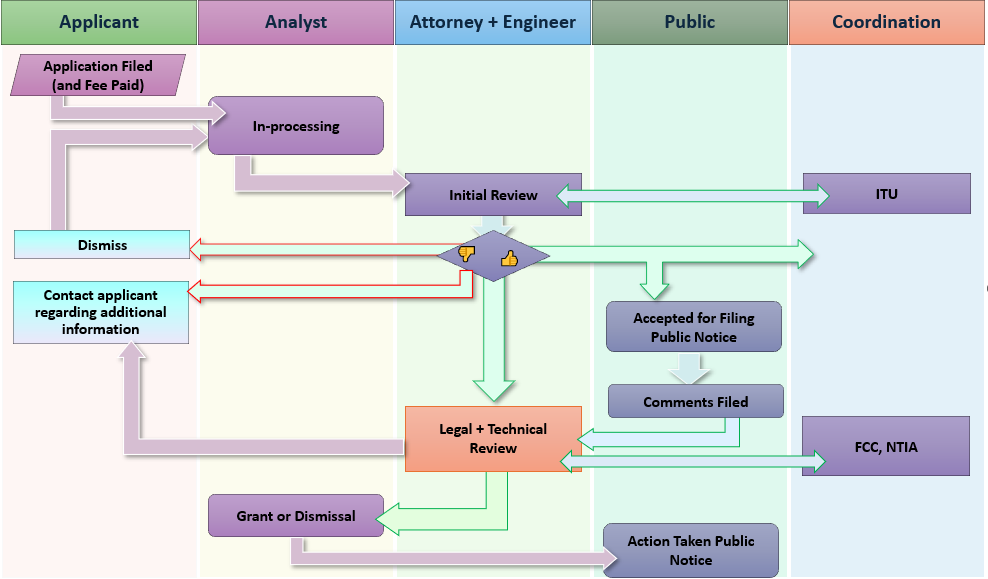

Understanding the FCC's Decision: What Actually Got Approved

The FCC didn't just rubber-stamp a request to launch more satellites. The agency actually evaluated what Space X proposed, raised concerns, and approved a portion while deferring the rest. That's the regulatory framework at work, even if the optics suggest Space X got most of what it wanted.

What the FCC approved is significant but not unlimited. Seven thousand five hundred satellites is a massive constellation, but it's not the 15,000 Space X pitched. The FCC's reasoning: the agency wanted time to study potential interference with other satellite operators, ground-based telecommunications systems, and Earth observation satellites. Fair concern. Adding more satellites to an already-crowded orbital environment means more potential for interference.

The approval also includes operational constraints. These new satellites can operate on five frequency bands. That's more flexibility than current-generation Starlink satellites, which operate on a narrower band. More frequencies mean more capacity and better spectrum efficiency. But it also means more coordination with other satellite operators. The FCC isn't just handing Space X blank checks.

Direct-to-cell connectivity is perhaps the biggest unlock here. Currently, if you're in a rural area without cellular coverage, satellite internet works for data but not for calls. The new capability means your phone can connect directly to a Starlink satellite for voice, text, and data. Globally, this is transformative. In the United States, it's supplemental to existing cellular networks. But in developing countries or remote regions where cellular infrastructure barely exists, this changes the game.

The timeline is tight but realistic. Space X needs to launch 3,750 satellites by December 2028. That's roughly 1,250 per year for three years. Given that Space X has been launching around 50 Starlink satellites per Falcon 9 mission, and they've scaled up launch cadence significantly, this is achievable. The second half by December 2031 gives them more breathing room.

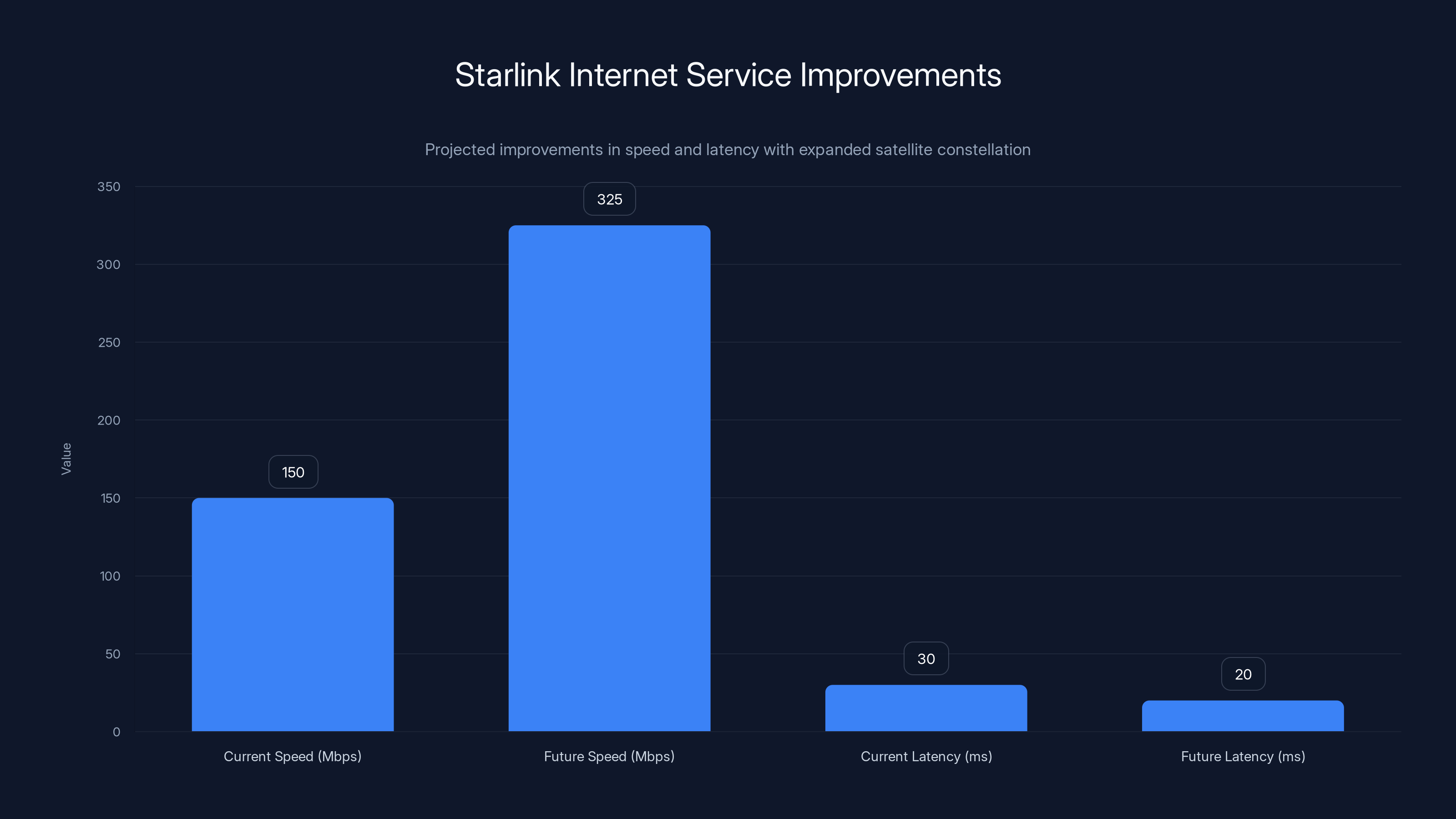

Starlink's expanded satellite constellation is projected to improve download speeds from 150 Mbps to 325 Mbps and reduce latency from 30 ms to 20 ms. Estimated data.

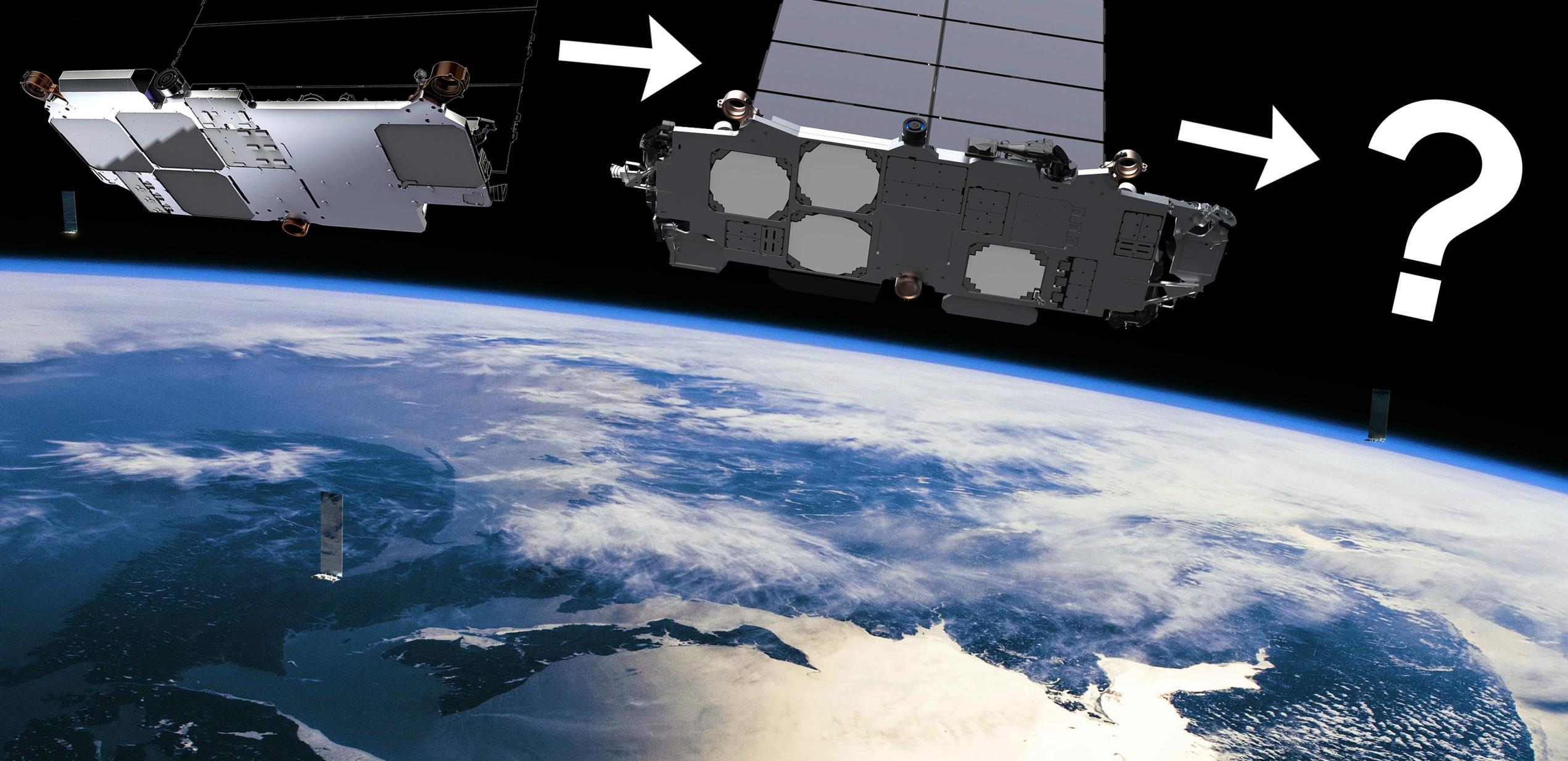

Second-Generation Starlink: Why It's Different from First-Gen

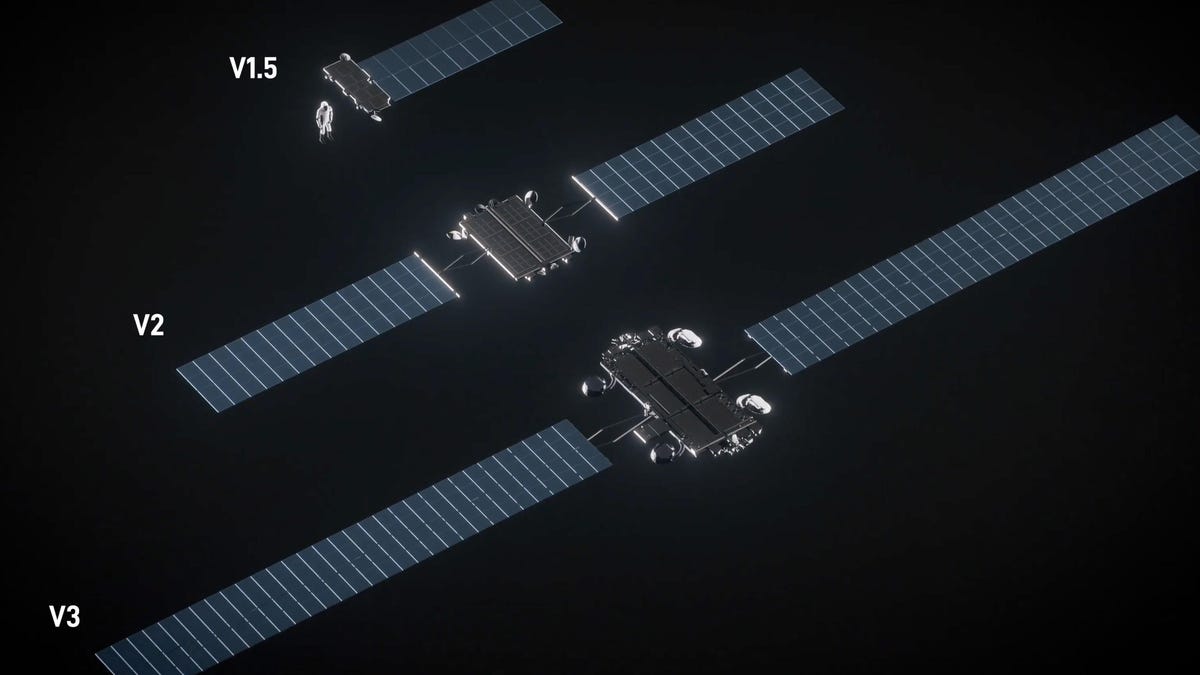

First-generation Starlink satellites served a purpose. They proved the concept worked. Coverage expanded. Speeds improved. But they had limitations. The second-generation satellites address most of those constraints.

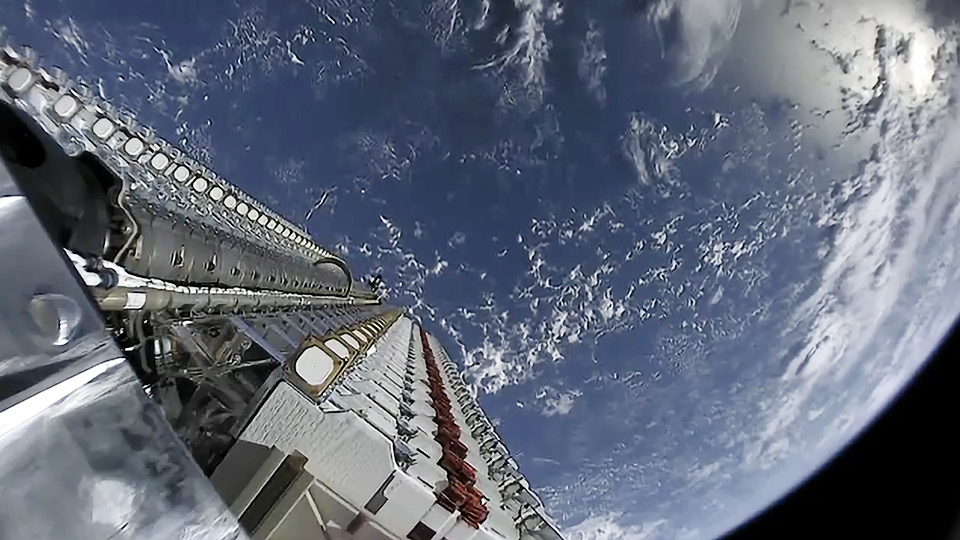

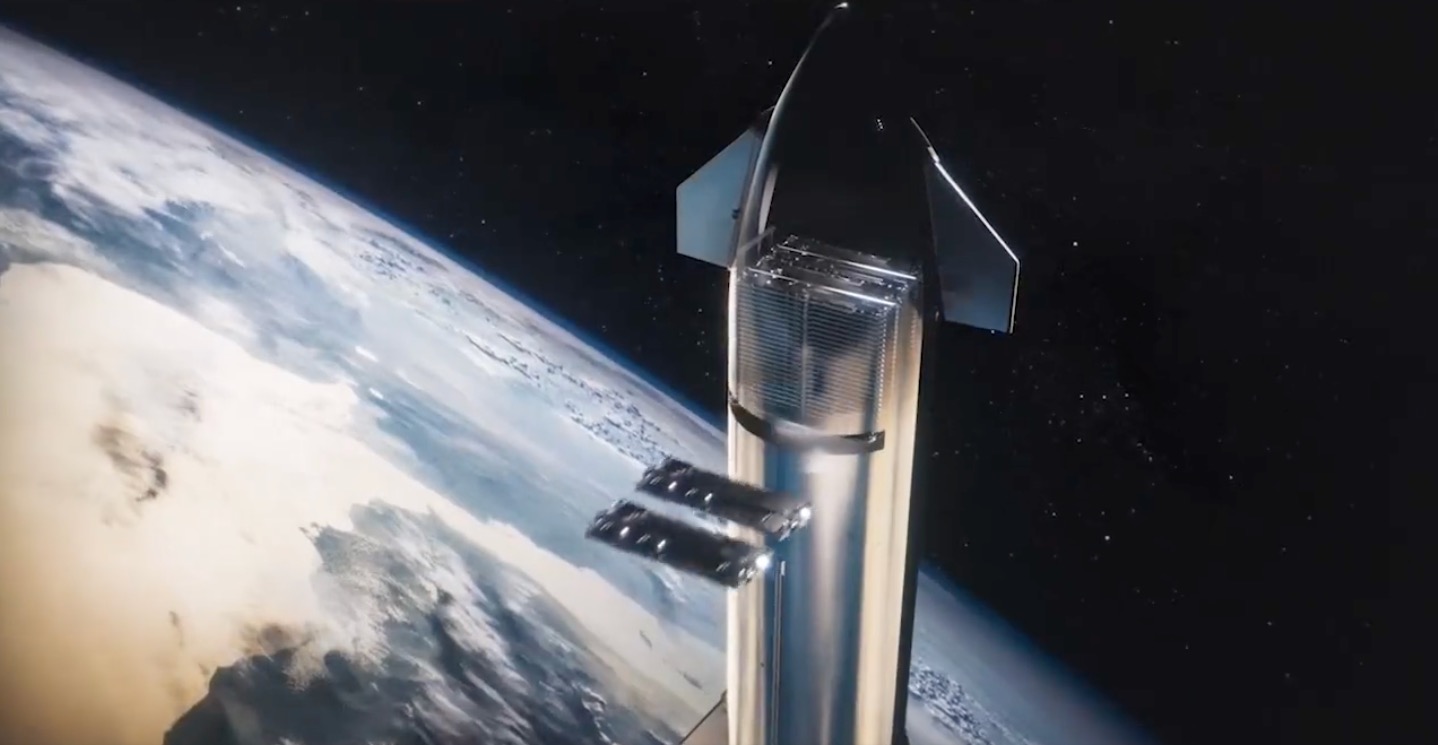

Size and weight are the first obvious differences. Gen 2 satellites are substantially larger and heavier than Gen 1. Larger apertures mean more capacity per satellite. That translates to higher throughput and more simultaneous connections. You're not just adding satellites; you're adding satellites with significantly better performance.

Communications capability is another huge upgrade. Gen 2 satellites have more advanced inter-satellite links, which is technical jargon for better communication between satellites in the constellation. This matters because it means data can route more efficiently through the network. Instead of bouncing traffic back to ground stations frequently, satellites can pass data along the network. Lower latency. Better reliability. Faster speeds.

Frequency flexibility is critical. I mentioned earlier that Gen 2 satellites operate on five frequency bands. Compare that to current Starlink operations, which are more constrained. More frequencies mean less congestion, higher capacity, and better ability to avoid interference with other systems. It's like going from a two-lane highway to a five-lane expressway. You can handle way more traffic without everyone getting backed up.

Power consumption is a consideration that doesn't get much attention but matters immensely. Second-gen satellites need more powerful solar arrays and batteries to support all that additional capability. Space X has invested heavily in power systems that can sustain the higher operational demand. This affects constellation lifetime. A satellite that burns through power quickly doesn't last as long in orbit.

Testing has been ongoing. Space X has launched multiple Gen 2 test satellites already, gathering real-world performance data. These aren't flying blind. They've iterated through failures, observed how satellites perform, and refined designs accordingly. The FCC approval is based partly on demonstrated capability, not just theoretical performance.

The manufacturing scale required for 7,500 satellites is immense. Space X has ramped up production significantly, but there are limits to how fast you can physically build, test, and prepare satellites for launch. The timeline constraints in the FCC approval reflect realistic manufacturing capacity, though Space X has surprised people before with accelerated schedules.

The Direct-to-Cell Revolution: Why This Changes Everything

Direct-to-cell connectivity via satellite is not brand new as a concept. But Space X implementing it at scale and getting FCC approval for it internationally? That's significant.

Here's what it means in practical terms. You're in rural Montana. No cell coverage. Starlink's satellite is overhead. Your phone automatically connects to that satellite, and suddenly you can send a text message or make an emergency call. No special hardware. No app. Your phone just works, the same way it would with a tower.

The applications are enormous. Emergency responders in disaster zones can communicate instantly without rebuilding infrastructure. Farmers in developing nations with no cellular access can run connected operations. Ships in the middle of the ocean can have reliable communication. Hiking and outdoor enthusiasts can stay in touch even in remote areas.

Latency is the critical variable here. Early satellite systems had latency in the 600 to 800 millisecond range, which made real-time communication feel sluggish. Modern Starlink satellite systems have dropped that to 20 to 40 milliseconds for data, which is comparable to terrestrial cellular. Direct-to-cell latency will be slightly higher, but still acceptable for voice and messaging. It won't feel different from a normal call.

Bandwidth is another constraint. You can't stream video over direct-to-cell satellite links in the same way you do over LTE. The capacity per satellite serving a wide area is limited. But for voice, messaging, and light data, it's more than sufficient. The FCC's decision to allow supplemental coverage in the United States suggests they're thinking about this as a backup when terrestrial systems are overwhelmed or damaged, not as a primary replacement.

International deployment of direct-to-cell is even more significant. In countries where cellular infrastructure is sparse, satellite direct-to-cell becomes a genuine alternative to building towers. Countries in Africa, Southeast Asia, and Latin America have enormous populations in areas without cellular coverage. Starlink satellites overhead means those areas get connectivity without massive infrastructure investment.

Competition with terrestrial carriers is inevitable. Telecom companies in developed markets are watching this closely. If Starlink can offer competitive voice and data rates globally, it disrupts the traditional telecom business model. That's why you're seeing some carriers partner with Starlink (like they've done with T-Mobile in the U. S.) and others lobby regulators to limit satellite capabilities.

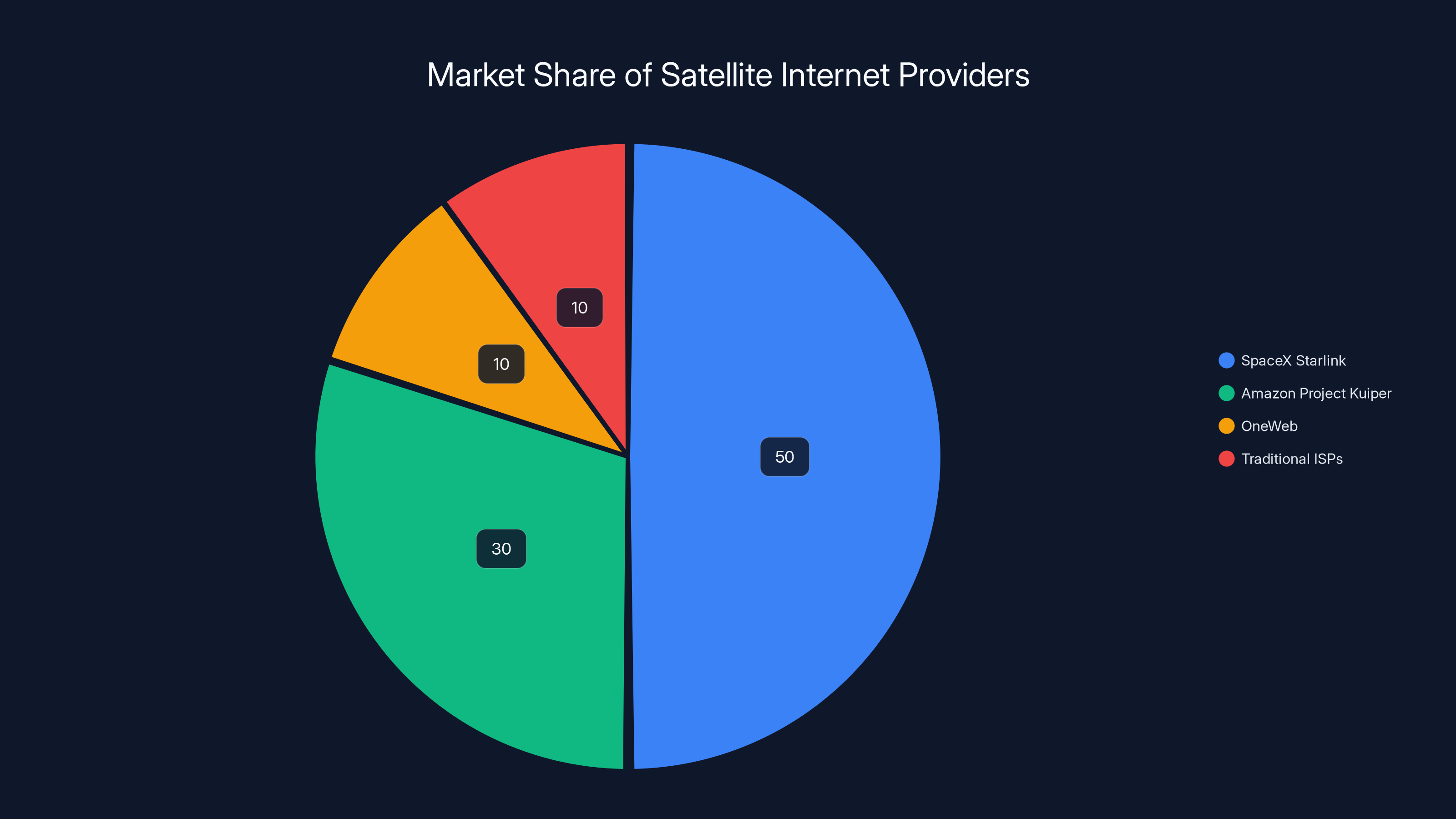

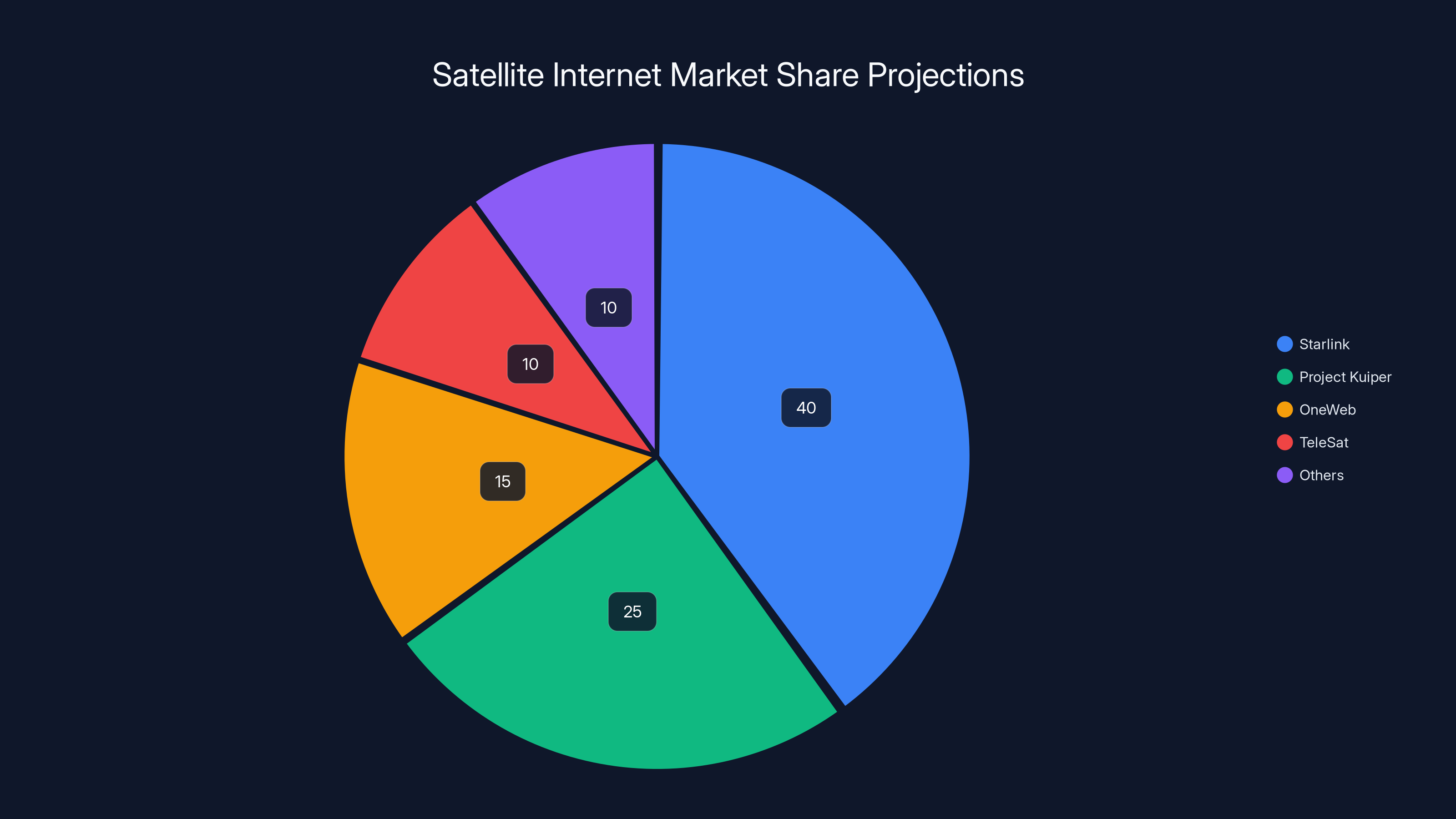

SpaceX Starlink is projected to dominate the satellite internet market with 50% share, followed by Amazon's Project Kuiper at 30%. OneWeb and traditional ISPs share the remaining market. Estimated data.

What the FCC Didn't Approve: The Deferred 14,988 Satellites

Space X asked for 15,000 satellites. They got 7,500. What happened to the remaining 14,988?

The FCC deferred authorization, which is regulatory speak for "we need more time to study this." It's not a rejection. It's a pause. But pauses in regulatory approval can become permanent if concerns aren't addressed.

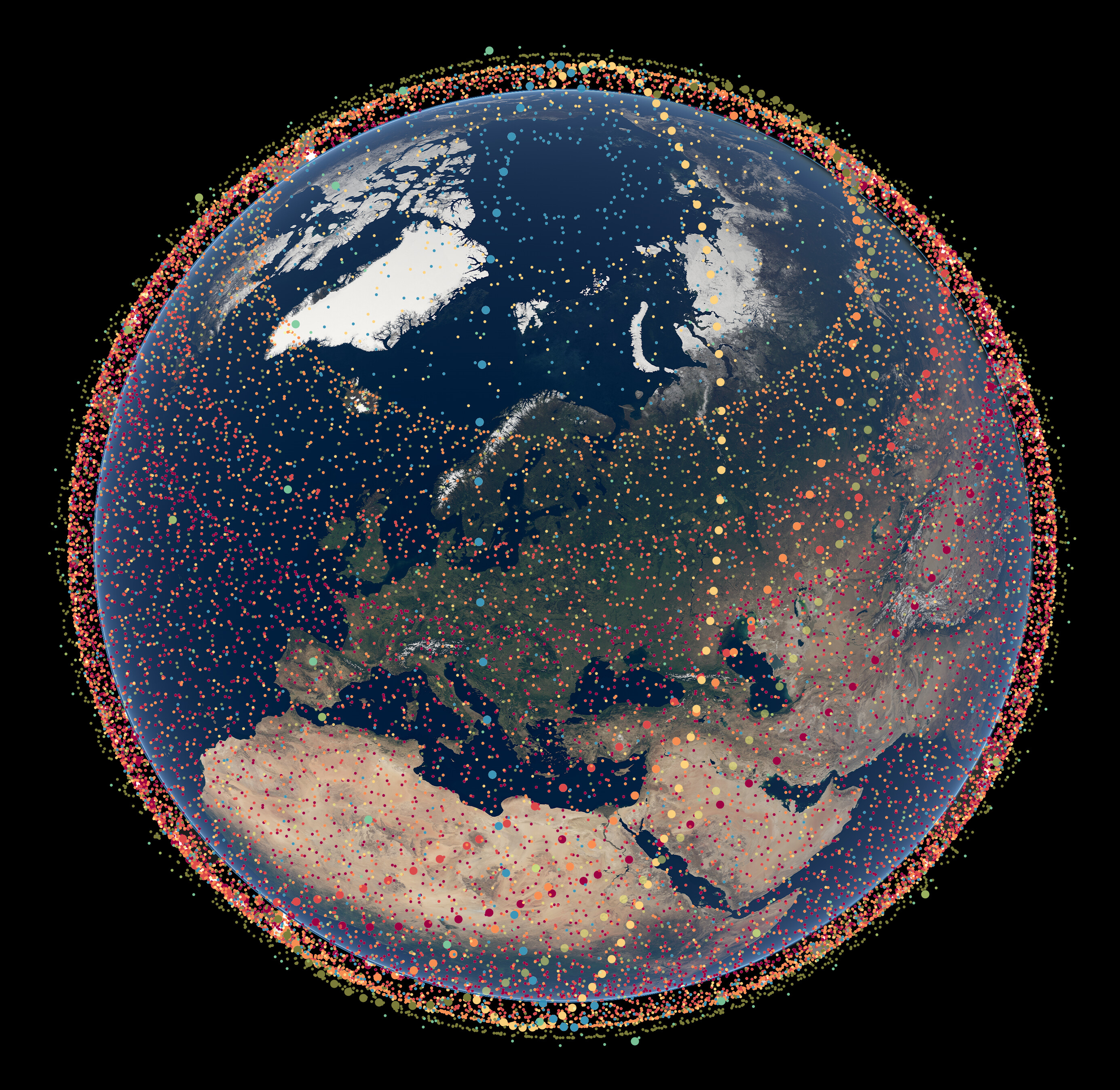

The stated reasoning involves potential interference with other satellite systems, ground-based networks, and Earth observation satellites. That sounds generic, but there's real substance underneath. The orbital space at medium Earth orbit and low Earth orbit is getting crowded. Starlink is the largest single constellation, but there are others: Amazon's Project Kuiper is coming online, China's Guowang constellation is in development, and there are smaller operators filling niches.

When satellites share orbital zones, interference becomes a technical and regulatory nightmare. Frequencies can overlap. Radiation patterns can interfere with ground stations. Debris from decommissioning old satellites can hit new ones. The FCC has to balance Space X's expansion ambitions against broader spectrum management.

Earth observation satellites are a specific concern. These are used for weather forecasting, climate monitoring, agriculture, disaster response, and national security. Space X's Starlink satellites can interfere with the sensors on these observation satellites, degrading data quality. It's not catastrophic, but it's real. The FCC is hearing from agencies like NOAA about the importance of protected observation bands.

The deferred satellites might get approved later if Space X can demonstrate adequate mitigation for these concerns. Or the FCC might approve them with additional constraints. Or approval might get stuck indefinitely while Space X and other parties negotiate technical standards.

The timeline pressure is deliberate. By requiring 50% of approved satellites to launch by December 2028, the FCC is saying Space X needs to demonstrate execution capability before getting approval for the rest. If Space X stumbles, misses launch targets, or causes interference issues, the remaining satellites might never get cleared. It's regulatory oversight working as intended, not as a constraint but as a gate.

This also gives competitors time to file objections and make their case. Amazon, One Web, traditional telecom companies, and international space agencies can all raise concerns about the remaining satellites. The deferred approval period is when those arguments get heard.

Global Internet Coverage: The Real Endgame

The practical outcome of 15,000 Starlink satellites is near-global internet coverage with reasonable speed and latency. Let's be specific about what that means.

Coverage is the first obvious benefit. Starlink already reaches most inhabited areas of Earth. Seven thousand five hundred additional satellites with larger capacity doesn't dramatically expand coverage area, but it dramatically improves redundancy and capacity in existing coverage zones. More satellites overhead means more simultaneous connections and faster speeds for the same geographic area.

Speed improvements are coming. Current Starlink residential service offers download speeds around 50 to 250 Mbps depending on location and congestion. With second-gen satellites and expanded constellation, expect that to rise to 150 to 500 Mbps in most served areas. That's competitive with good fiber and way better than legacy copper-based DSL. It won't match fiber in optimal conditions, but it's in the same ballpark.

Latency will improve modestly. I mentioned earlier that modern Starlink latency is 20 to 40 milliseconds. With more satellites and optimized routing, you might see that drop to 15 to 25 milliseconds. It matters for gaming and real-time applications. At 15 milliseconds, you're pretty close to what you get with terrestrial networks. Gaming competitively becomes viable.

Cost structure is critical. Space X has repeatedly stated that satellite internet needs to be affordable to disrupt the market. The expansion to 15,000 satellites is partly about spreading capital costs over more revenue-generating units. Fixed costs get amortized across more customers. That should push service pricing down over the next few years, though Space X has other financial priorities.

Competition is intensifying. Amazon's Kuiper constellation will eventually offer competing service. One Web is already in orbit, though with different positioning. Traditional ISPs are watching and investing in their own infrastructure. The healthy competitive dynamic should drive innovation and pricing pressure on everyone, including Space X.

Regulatory approval in other countries matters immensely. The FCC approval is U. S.-centric. Space X needs approvals from regulators in Europe, Asia, Latin America, and Africa to operate fully. Some countries will demand local partnerships. Others will limit frequencies or coverage. The 15,000 satellite constellation is designed with flexibility to operate across diverse regulatory environments, but each one takes time.

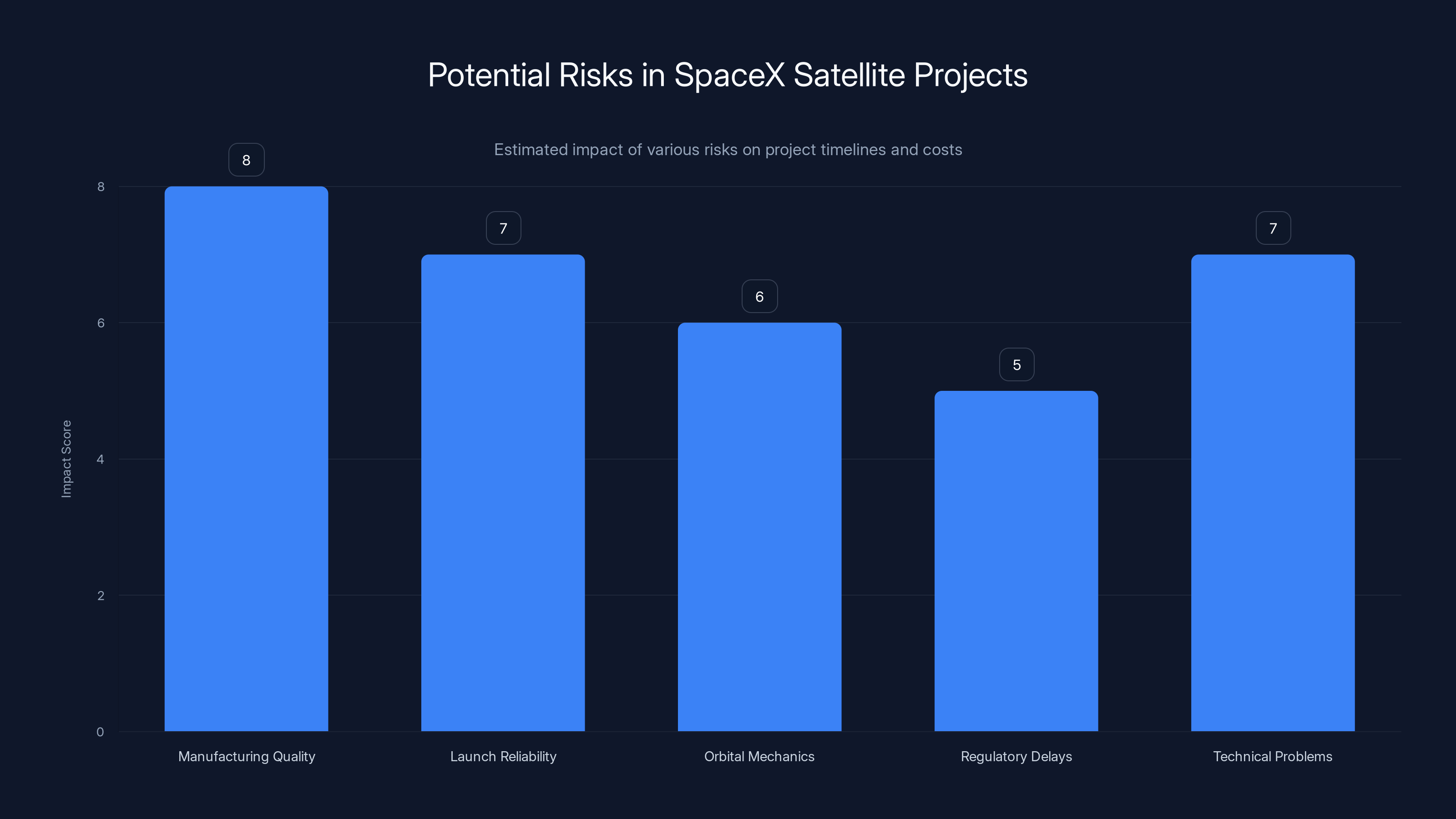

Manufacturing quality and technical problems are estimated to have the highest impact on SpaceX's satellite project timelines and costs. Estimated data.

The Timeline Matters: Meeting December 2028 and December 2031 Deadlines

Space X has shown it can accelerate launches when it matters. But timelines in regulatory approval are different from internal targets. Miss them, and the FCC can reevaluate the entire approval.

December 2028 is 36 months away. Space X needs to launch 3,750 satellites by then, which breaks down to roughly 1,250 per year or 104 per month. They're currently launching around 30 to 40 Starlink satellites per Falcon 9 mission, with multiple missions per month. So they need roughly 2.5 to 4 missions monthly for satellites alone. That's possible but requires maintaining launch cadence while also servicing other customers.

Manufacturing is the actual constraint, not launch capacity. Building, testing, and preparing 3,750 satellites in 36 months means producing about 100 per month. Space X has ramped up production, but there are physical limits to how many you can build in a facility. Quality control matters too. You can't just throw satellites at rockets; they need to work.

December 2031 is more relaxed, giving Space X seven years for the full constellation. That's 2,143 satellites per year or roughly 178 per month. More manageable, but still requires sustained production and launch cadence.

What could cause delays? Hardware failures during testing. Manufacturing bottlenecks. Launch vehicle problems. Competition for launch capacity. International regulatory issues. Unexpected technical problems discovered during deployment. Space weather affecting orbital operations. Any of these could push timelines back.

The FCC won't grant automatic extensions. Space X would need to formally request relief, which opens the approval to reconsideration. Better to build in contingency and finish early than to ask for delay and trigger re-review.

Historically, Space X has been better at maintaining aggressive timelines than traditional aerospace companies. But satellite constellations are different from single-payload missions. The scale and complexity are greater. Still, betting against Space X meeting these timelines is risky.

Parallel development is Space X's advantage. They can work on launch vehicle improvements while ramping satellite production. They can test satellite improvements on early Gen 2 units while manufacturing later batches. The integration of design, manufacturing, and launch at one company creates efficiency gains that traditional contractors can't match.

Orbital Debris and Space Sustainability: The Elephant in the Room

More satellites means more stuff in orbit. Eventually, every satellite dies. When it does, it becomes debris if not properly decommissioned. The FCC approval requires Space X to manage this, but it's worth understanding the challenge.

Starlink satellites have orbital lifespans of roughly 5 to 7 years. At full constellation of 15,000 satellites, that means roughly 2,000 to 3,000 satellites reaching end-of-life annually. Each one needs to either be deorbited (brought back to Earth to burn up in the atmosphere) or maneuvered to a graveyard orbit above operational altitude.

Space X designs Starlink satellites to deorbit passively. Each satellite carries fuel that, when depleted at end-of-life, leaves enough margin for a final descent burn. The satellite reenters Earth's atmosphere and burns up. It's not guaranteed; some debris survives reentry. But it's better than leaving dead satellites in orbit indefinitely.

The fuel margin is critical. If a satellite fails early and can't maneuver, it becomes debris. On a constellation of 15,000 units, even a 1% failure rate that prevents proper deorbiting means 150 defunct satellites staying in orbit. That sounds small until you consider collision risk. Debris traveling at 17,500 miles per hour can destroy active satellites. One collision creates more debris, which creates more collisions. Kessler Syndrome, the cascade failure scenario, is a real concern.

Regulatory agencies are tightening debris requirements. The FCC now requires operators to deorbit satellites within five years of end-of-life. Space X's design supports this, but it's a constraint on satellite design and operations. Every gram of fuel allocated to deorbiting is fuel not available for station-keeping or other operations.

International coordination is essential. Debris from one country's satellites affects everyone's space operations. The UN and various international bodies have established guidelines, but enforcement is weak. The FCC is pushing Space X to be responsible, which sets a precedent. If Space X does this well, pressure increases on other operators to match.

The argument that Starlink satellites are small and mostly burn up on reentry is true but incomplete. Yes, most material burns. But some fragments survive, some debris pieces from the rocket body, and the occasional malfunction means fragments reach the ground. Risk is manageable but real.

Long-term, sustainable space operations require solving the debris problem. Space X's approach is responsible but not revolutionary. We need active debris removal technology, better collision avoidance systems, and enforcement of deorbiting standards. The FCC approval includes provisions for ongoing monitoring, which is at least a step forward.

Estimated data suggests Starlink will maintain a significant market share by 2027, but Project Kuiper and OneWeb will also capture substantial portions, indicating a competitive landscape.

Interference Concerns: The Technical Reality

When the FCC deferred the remaining 14,988 satellites, interference was cited as a key concern. Understanding what interference actually means helps clarify the decision.

Spectrum interference is the most straightforward. Starlink uses specific frequency bands. Other satellite operators use overlapping bands. When both transmit in the same area, signals can degrade each other. Coordination and careful frequency planning can minimize this, but it requires cooperation and international agreements. More satellites mean more complexity in coordination.

Astronomical observation interference is more nuanced. Ground-based telescopes and space-based observatories use specific frequencies to observe the universe. Starlink satellites reflecting sunlight or radiating in observation bands can contaminate data. Modern telescopes have filters and can work around this, but it's an added constraint. A constellation of 15,000 satellites means more potential for contamination.

GPS and navigation interference is less of a concern for Starlink specifically, but it's relevant for the broader space environment. More satellites transmitting means more potential for signal degradation of GPS receivers. Modern receivers are resilient, but the accumulated effect of 30,000+ satellites from multiple operators could eventually require spectrum management adjustments.

Earth observation interference is specific and significant. Satellites monitoring weather, climate, agriculture, and disaster response operate in certain frequency bands. Starlink interference with these systems degrades their capability, which has real consequences. NOAA and international weather organizations are invested in protecting these frequencies. The FCC is hearing their concerns.

Technical mitigation exists. Frequency coordination databases allow operators to plan transmissions to avoid conflicts. Directional antennas focus signals away from sensitive bands. Ground station placement can reduce interference. But mitigation adds complexity and cost. As constellations grow, mitigation becomes harder.

The deferred approval probably reflects pressure from other parties who want the FCC to establish stricter interference standards before approving more satellites. It's not necessarily that 15,000 satellites will cause catastrophic interference. It's that the regulatory bar for allowing additional satellites should be higher. The FCC is listening to that argument by deferring.

Competition and Market Implications: Who Wins and Loses

Space X's constellation expansion has enormous implications for competitors and the broader telecom market.

Amazon's Project Kuiper is the most direct competitor. Amazon has FCC approval for roughly 3,000 satellites, with potential expansion to 13,000. Amazon's satellites target a different orbit than Starlink (higher altitude, longer latency but wider coverage per satellite). The two systems serve different market segments. But both will eventually compete for customers. Amazon has unlimited capital and corporate backing. They're a serious threat to Starlink's dominance.

One Web is smaller, with about 400 satellites in orbit and plans for 6,000 total. One Web focuses on enterprise and government markets rather than residential consumers. They've secured partnerships with European agencies and telecom companies. One Web's market is real but niche compared to what Starlink targets.

Traditional ISPs are the biggest losers. Fiber deployment is expensive and slow. Wireless carriers have limited spectrum. Starlink coverage in rural areas undercuts the value of their network expansions. Rural broadband subsidies from government programs could shift from funding fiber to allowing Starlink subscriptions. That reduces revenue for traditional providers. Some have responded by acquiring stake in space-based alternatives or partnering with Starlink.

Telecom carriers in developing nations face existential pressure. If Starlink offers decent service globally without requiring ground infrastructure partnerships, it bypasses traditional carrier business models. Carriers can't prevent Starlink from operating in their airspace (mostly), so they're forced to adapt. Some are considering Starlink as a complement, not a threat.

Governments benefit from expanded connectivity in underserved areas. Rural broadband access is a policy priority in most democracies. Satellite internet offers a faster path than fiber deployment. Subsidies might shift toward making satellite service affordable for rural consumers rather than funding infrastructure build-out. That's politically popular even if it means traditional carriers lose revenue.

Venture-backed satellite startups in niche markets (Earth observation, data collection, specific vertical solutions) are less affected. They serve specialized needs that Starlink's general-purpose internet service doesn't directly compete with. But capital availability for space ventures has increased partly because of Space X's success and investor appetite for space commerce. Competition for funding intensifies, but the pie grows.

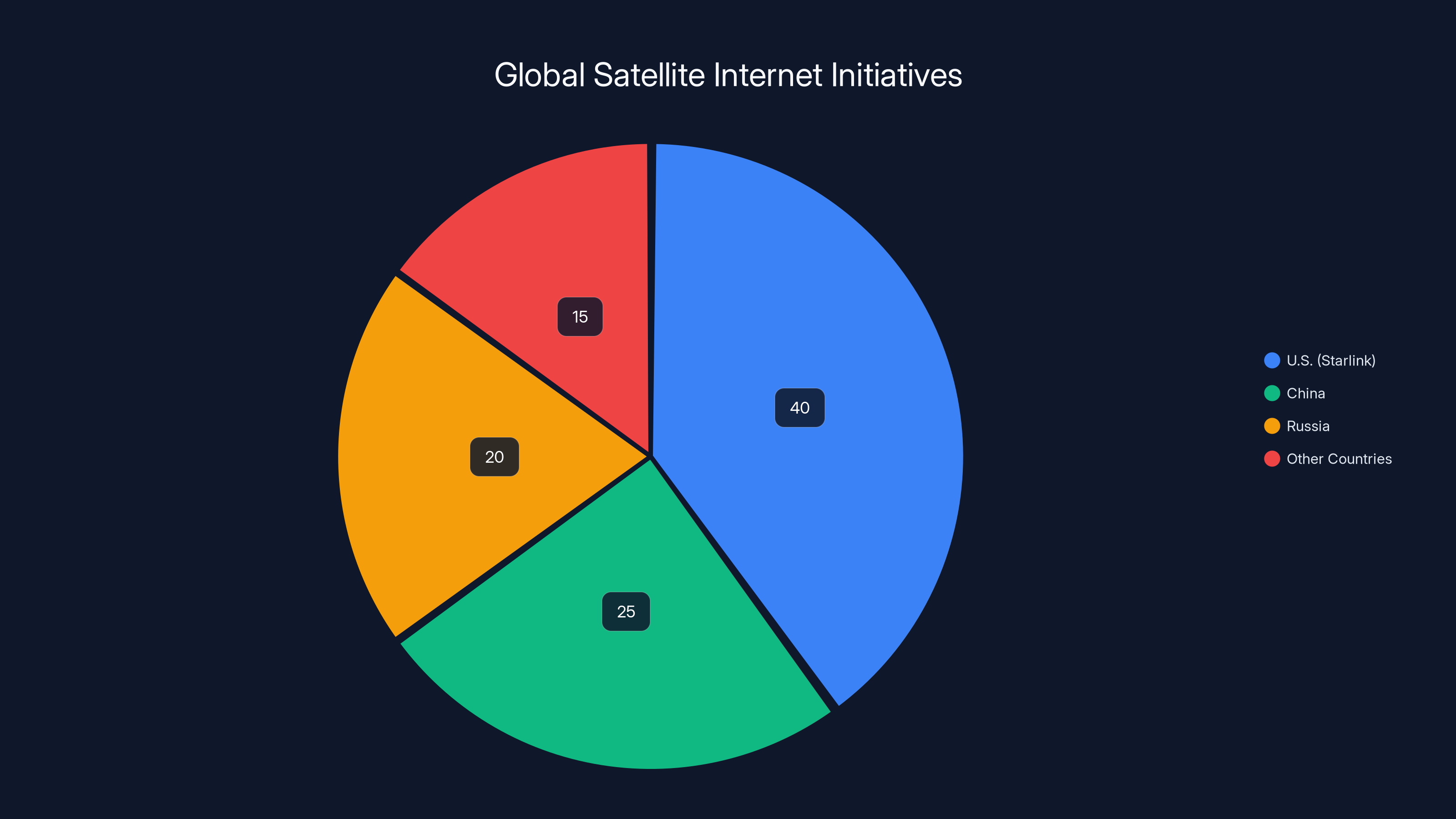

Estimated data shows the U.S. leads with Starlink, but China and Russia are rapidly developing their own satellite constellations to reduce reliance on U.S. infrastructure.

Financial and Strategic Implications for Space X

The FCC approval is strategically significant beyond the immediate satellite constellation benefits.

Revenue scaling is obvious. More satellites in orbit means more capacity for customers. Capacity constraints are currently limiting Starlink's ability to add subscribers in congested areas. Second-generation satellites with larger capacity and the expanded constellation remove that constraint. Revenue can scale without hitting a ceiling.

Valuation impact matters for Space X's fundraising and future IPO possibilities. Every major approval milestone increases investor confidence in the Starlink business. The FCC approval is material validation that the business model is viable at scale. Conversations with investors will be different after this approval than before.

Capital requirements are immense. Building and launching 15,000 satellites costs tens of billions of dollars. Space X is funding this from internal cash flow, venture financing, and external investments. The approval de-risks the business case, making it easier to raise capital. But capital intensity remains the limiting factor for how fast Space X can scale.

Space X's other business units benefit from constellation growth. Starlink requires frequent launches. Every Starlink launch is a Falcon 9 mission that generates revenue and experience. Rocket reusability improvements come from launch cadence. The Starship program benefits from lessons learned on Falcon 9. Synergies between Starlink and launch services amplify each other.

International expansion costs are front-loaded. Securing regulatory approvals in each country, establishing ground stations, building local partnerships, and managing compliance costs money. The FCC approval is just the start. European, Asian, and Latin American regulators will each have their own review processes. Expect 12 to 24 months per major region for full regulatory clarity.

Employee scaling is required. Building 15,000 satellites and launching them all requires hiring hundreds or thousands of engineers, technicians, and operations staff. Space X is already growing rapidly, but this acceleration will test their recruiting and management capacity. Culture and quality maintenance become harder at larger scale.

Stock-based compensation and equity incentives matter. Space X employees are betting their long-term wealth on the company's success. Major milestones like FCC approval increase the perceived value of that equity. Retention improves. Recruitment becomes easier.

Geopolitical Dimensions: Global Implications

Beyond commerce, Starlink's expansion has geopolitical consequences that nations are taking seriously.

Cyberinfrastructure resilience is a national security concern. Countries that rely on terrestrial networks operated by foreign companies face potential vulnerability. Satellite internet from Space X (a U. S. company) creates similar dependencies. China and Russia are developing their own satellite constellations partly to reduce reliance on Starlink and U. S.-controlled infrastructure. The FCC approval accelerates this competition.

Digital divide reduction is real but uneven. Starlink coverage reaches most inhabited areas, but affordability is another matter. In developing countries, a $100 monthly Starlink subscription is unaffordable for most households. Without subsidies or lower pricing, Starlink coverage doesn't translate to access. Governments in developing regions are watching whether Space X can make service affordable or if they need to fund subsidies.

Military and government applications are significant. Direct-to-cell capability enables military communications in austere environments without relying on terrestrial networks. The U. S. military is already integrating Starlink into operations. Other nations are developing countermeasures or seeking alternative sources. This arms-race dynamic is why some countries are investing in their own constellations.

Data sovereignty concerns are rising. Every internet connection through Starlink creates traffic that potentially transits U. S. infrastructure, at least from a regulatory perspective. European regulators are concerned about data governance. China explicitly distrusts U. S.-controlled infrastructure. Russia has restricted Starlink. These geopolitical tensions will shape regulatory decisions about constellation expansion in various countries.

International treaties and agreements are inadequate for modern space commerce. The Outer Space Treaty (1967) is the foundational document, but it predates commercial satellite constellations. There's no agreement on interference standards, debris responsibility, or spectrum allocation for large operators. The FCC's approach to regulating Starlink is somewhat pioneering, setting precedent for how other regulators might approach the problem.

Competitive advantage in rural connectivity matters politically. The first nation to provide affordable, reliable satellite internet broadly changes the competitive landscape. Space X has first-mover advantage. China and Russia are trying to catch up. The outcome affects which nations develop digital economies and which remain dependent on foreign infrastructure.

Challenges and Risks: What Could Go Wrong

The approval assumes execution, but history shows that space projects encounter unexpected challenges.

Manufacturing quality at scale is the first risk. Space X has proven good at Falcon 9 production, but satellite manufacturing is different. Each satellite is complex with thousands of components. A design flaw discovered after 1,000 units are built could require rework or scrapping. Quality defects would delay timelines and increase costs.

Launch vehicle reliability remains critical. Falcon 9 has a strong reliability record, but no vehicle is perfect. A serious anomaly could ground the vehicle for investigation. Space X has Falcon Heavy available as backup, but launch cadence would suffer. Delays in getting vehicles flying again directly threaten the FCC timeline.

Orbital mechanics and space weather present unpredictable challenges. Solar activity varies. Geomagnetic storms can increase atmospheric drag, pulling satellites down faster. Individual satellites can fail earlier than designed. On a constellation of 15,000 units, even normal failure rates mean hundreds of failed satellites that need replacement. Manufacturing and launch cadence must account for attrition.

Regulatory delays in other countries could slow global rollout. Space X can't fully monetize the constellation until it's approved worldwide. Delays in key markets (Europe, China, India) would reduce revenue and pressure profitability timelines. International approvals are less in Space X's control than U. S. approval.

Technical problems with second-gen satellites discovered after deployment could require redesign. Testing can't replicate all possible failure modes. Satellites operate for 5 to 7 years, and problems might emerge years after launch. This happened with early Starlink satellites; some had unexpected issues that required ground-based corrections. Gen 2 satellites are more complex, increasing risk of unknown unknowns.

Competition could accelerate faster than expected. Amazon's Kuiper might launch more aggressively. Other entrants might emerge. Market saturation in some regions could occur faster, reducing pricing power. Price wars are possible if multiple operators compete for the same customers.

Customer demand uncertainties linger. Starlink needs to acquire millions of paying subscribers to justify the constellation. Residential demand exists, but will it grow fast enough? Enterprise and government demand is real, but what price point clears the market? If growth is slower than projected, the financial case weakens.

Costly surprises in deorbiting could emerge. If satellites fail to deorbit properly or if reentry poses more risk than anticipated, remediation could be expensive and complicated. Environmental concerns about reentry could also create political pressure for alternative decommissioning methods, which would increase costs.

Timeline to Full Deployment: What to Expect Year by Year

Understanding when you can actually use the expanded Starlink constellation helps contextualize the approval.

2025 through 2026: Manufacturing ramp and initial second-gen launches. Space X will increase production of Gen 2 satellites while continuing first-gen launches for existing commitments. You'll see Starlink-dedicated missions increasing in frequency. Coverage won't dramatically change, but capacity in existing coverage areas will improve subtly. Speeds and reliability should improve as new satellites deploy.

2027 through 2028: Acceleration toward first deadline. Launch pace reaches peaks. Starlink mission density increases significantly. By December 2028, Space X needs to have 3,750 satellites deployed. If on schedule, this is when you'd expect noticeable service improvements in most areas: faster speeds, lower latency, better availability during peak hours. International approvals should be mostly finalized by this point, enabling service in more countries.

2029 through 2031: Second phase build-out. Space X has more breathing room here, but the goal is deploying the remaining 3,750 satellites. Manufacturing continues at high volume. Launch cadence remains elevated but less frantic than 2027–2028. By late 2031, the full 7,500 approved satellites are operational. The constellation reaches mature capacity.

Beyond 2031: Stabilization and operations. Space X shifts from growth to steady-state operations. Launch missions focus on replacing aging satellites as they reach end-of-life. The constellation becomes a revenue-generating asset rather than a growth project. By this point, Starlink should be profitable and self-funding from operations.

But remember, this is the approved portion. If Space X successfully demonstrates 15,000 satellites don't cause unmanageable interference, the FCC could approve the remaining 14,988 satellites deferred today. That's another 5 to 7 years of deployment beyond 2031. And there's always the possibility of requesting even more satellites as technology improves and demand grows.

Service improvements for consumers should be tangible by 2027 and dramatic by 2028. If you're currently a Starlink customer, expect better service. If you're considering it, waiting until 2026 or 2027 is probably wise because improvements are coming.

For enterprise and government customers, deployments will accelerate once the constellation approaches maturity. Mission-critical applications requiring high reliability prefer proven, mature systems to brand-new rollouts. The 2028 to 2030 window is when enterprise adoption should spike.

The Broader Satellite Internet Landscape: Beyond Starlink

While Starlink dominates headlines, it's one piece of a larger satellite internet market emerging.

Amazon's Project Kuiper is the 800-pound gorilla to watch. Amazon has regulatory approval for 3,000 satellites with potential expansion to 13,000. They're building this slowly and deliberately, which suggests they want to avoid Starlink's challenges. Amazon's first launches are expected within 12 to 18 months. By 2027, Kuiper should be commercial. Competition will intensify from there.

One Web is already operational with about 400 satellites providing coverage. Their business model targets enterprise and government rather than consumers. They're profitable and growing. One Web's existence proves the market works; they're just playing a different game than Starlink.

Tele Sat's Lightspeed constellation is another entrant. Fewer satellites but higher orbit means different coverage and latency characteristics. Canadian-backed, regulatory approvals are progressing. They're targeting enterprise communications.

Startups in the space are exploring niches: Earth observation, Io T connectivity for devices, maritime communications, aviation connectivity. These aren't direct Starlink competitors but represent adjacent market opportunities. The successful ones will offer specific value Starlink doesn't, not try to out-Starlink Starlink.

International constellations are emerging too. China's Guowang, Russia's Sphere, and others are developing sovereign alternatives to Western systems. These are partly technological, partly geopolitical. Countries want options that aren't dependent on U. S. companies.

The market is large enough for multiple operators. Global internet infrastructure is diverse; many providers coexist. Satellite internet is becoming part of that diversity rather than a Starlink monopoly. That's actually healthy for competition and innovation.

Pricing will trend downward as competition intensifies. Current Starlink residential pricing is around

What This Means for Internet Infrastructure and Society

Zooming out, the FCC approval represents a inflection point in global internet infrastructure.

The terrestrial internet we built over 40 years isn't changing. Fiber, 5G, copper DSL, and wireless all remain important. But space-based infrastructure is becoming a primary component rather than a backup. This is a meaningful shift in how we think about internet access.

Rural broadband will improve. The digital divide between rural and urban areas narrows. Not eliminated—terrain, economics, and local infrastructure still matter. But satellite connectivity reduces the gap significantly. That has educational, economic, and social implications.

Disaster resilience improves. When hurricanes, earthquakes, or other disasters damage terrestrial networks, satellite backup becomes more critical. Space X has demonstrated this; they've supported hurricane response and disaster relief. A mature constellation with multiple operators means more reliable backup availability.

Global connectivity is increasingly reality rather than aspiration. Developing nations without fiber infrastructure can skip legacy technologies and jump to satellite internet. It's not perfect, but it's better than no options. Over a decade, this cascades into broader digital economic transformation in underserved regions.

Privacy and surveillance become more complex. Satellite internet means traffic potentially routes through U. S. infrastructure and legal jurisdiction. Privacy-conscious users in certain jurisdictions might prefer local alternatives. Governments might mandate domestic infrastructure. The geopolitical tensions around internet governance intensify.

Space infrastructure becomes critical national security concern. The U. S. relies on space-based assets for communications, navigation, and surveillance. Expanded commercial space infrastructure increases dependency but also increases vulnerability. Military planning has to account for potential threats to satellite constellations.

Climate and environmental questions linger. Thousands of satellites in orbit affect Earth observation data quality. Reentry impacts are manageable but real. Long-term space sustainability requires solving debris and environmental concerns. The FCC approval includes provisions for monitoring, but international standards need strengthening.

Jobless projections and workforce implications exist. Fewer terrestrial network technicians will be needed if satellite backhaul replaces fiber routes. But satellite operations require new skills. Workforce transition will be real.

What Investors and Stakeholders Should Know

If you're invested in telecom, infrastructure, or space, this approval changes calculus.

Traditional telecom valuations face pressure. Companies relying on terrestrial broadband monopolies in rural areas see competitive threats emerging. Valuation multiples might compress as investors price in satellite competition. Not everywhere, but in specific markets and customer segments.

Space infrastructure companies get validation. The FCC approval demonstrates that space-based internet is commercially viable and regulatory framework is manageable. Other satellite operators and startup backers see a clearer path to viability. Capital for space ventures should increase.

Government broadband programs might shift strategy. Federal and state programs funding fiber deployment might redirect toward Starlink subsidies for rural customers. Cheaper and faster than fiber. Politically popular. But that requires legislative changes and appropriations.

Equity in Space X would be valuable if available. Space X is private, but employees holding equity benefit from increased valuation. Investors with secondary market access see potential gains. An eventual IPO (if Space X decides to go public) would value the company at enormous multiples based on Starlink's proven business model.

Risks remain significant. Space X has delivered on most promises, but space is hard. Technology changes. Market demand is uncertain. International regulatory challenges could slow expansion. Competitive pressure could compress margins. These aren't dealbreakers, but they're real risks that equity investors should consider.

Diversification across multiple satellite operators is prudent. Betting entirely on Starlink success is risky. Starlink dominance is likely, but competition will eventually limit market share. Investors comfortable with satellite internet as an infrastructure bet should diversify across Space X, Amazon, and other operators.

Long-term positioning in space infrastructure is sound. This isn't a temporary trend. Satellite internet is becoming permanent infrastructure. Valuations might fluctuate, but long-term trajectory is up. Patient capital with 5 to 10-year horizons benefits most.

FAQ

What exactly did the FCC approve for Space X's Starlink satellites?

The FCC approved Space X to launch 7,500 additional second-generation Starlink satellites, bringing the total constellation to 15,000 units. The approval includes operational capability across five frequency bands and direct-to-cell connectivity outside the United States with supplemental coverage domestically. Space X requested 15,000 satellites initially, but the FCC deferred authorization for the remaining 14,988 proposed satellites pending further review of interference concerns.

Why didn't the FCC approve all 15,000 satellites at once?

The FCC deferred the remaining satellites to study potential interference with other satellite operators, ground-based telecommunications systems, and Earth observation satellites. Interference management is complex with so many satellites in orbit. The FCC wanted time to evaluate technical impacts and coordinate with international regulators and affected parties. This phased approach lets Space X demonstrate successful operation of the approved constellation before expanding further.

What are the launch timeline requirements from the FCC?

Space X must launch 50% of the approved satellites (3,750) by December 1, 2028, and the remaining 50% by December 2031. These are regulatory deadlines, not guidelines. Missing them could trigger FCC reconsideration of the approval. Space X has demonstrated the launch cadence required is feasible, though it requires maintaining high production and launch rates.

How will second-generation Starlink satellites improve service compared to first-generation?

Second-generation satellites are significantly larger with greater capacity per satellite. They operate across five frequency bands instead of more limited spectrum, enabling higher throughput and less congestion. Inter-satellite links are improved, allowing more efficient data routing through the constellation. The combination means faster speeds, lower latency, and higher availability in coverage areas. Residential customers should expect download speeds improving from current 50–250 Mbps range toward 150–500 Mbps as Gen 2 satellites deploy.

What is direct-to-cell connectivity and why is it significant?

Direct-to-cell means your phone connects directly to a Starlink satellite without special hardware or apps, enabling voice calls, text messages, and data in areas without terrestrial cellular coverage. This is transformative for emergency responders, rural areas, maritime operations, and developing nations where cellular infrastructure is sparse. The FCC approval allows this globally outside the U. S. and as supplemental coverage domestically, enabling satellite-based communication even in remote locations.

How long will it take for consumers to see service improvements from this constellation expansion?

Initial improvements should be noticeable by 2027 as second-generation satellites deploy at scale. Speeds and latency should improve modestly, and congestion in populated areas should decrease. Dramatic improvements should be apparent by 2028–2029 when the approved constellation reaches mature deployment. For new customers outside current coverage, expansion capability is more immediate, potentially enabling service in areas currently dark within 18 to 24 months.

What happens to Starlink satellites at end-of-life, and does the FCC care about this?

Each Starlink satellite is designed to deorbit (reenter Earth's atmosphere and burn up) within five years of end-of-life through controlled descent burns. Space X must maintain fuel reserves for this purpose. The FCC requires compliance with orbital debris regulations and monitors satellite decommissioning. Proper deorbiting prevents accumulation of debris in orbit, which is critical for long-term space sustainability. Failures in this process would create regulatory issues for future approvals.

Will Starlink remain the dominant provider as other operators like Amazon Kuiper launch?

Starlink has first-mover advantage and will likely remain the largest constellation for years. However, Amazon Project Kuiper will provide serious competition starting around 2027. Market size is large enough for multiple operators serving different customer segments. Consumers will benefit from competition driving innovation and pricing pressure. Starlink's dominance in consumer market is likely to decline from near-monopoly to perhaps 40-50% market share over a decade, which is still enormous.

What are the geopolitical implications of Space X expanding Starlink globally?

Space X's expansion raises questions about dependency on U. S.-controlled infrastructure for critical communications. China and Russia are developing sovereign alternatives partly in response. European regulators are concerned about data sovereignty and infrastructure control. The approval implicitly positions the U. S. as dominant in space-based internet infrastructure, creating leverage in international relations. Other nations are investing in competitive systems to reduce reliance on Space X and U. S. jurisdiction.

How much will expanded Starlink service cost consumers?

Current Starlink pricing ranges from

What could prevent Space X from meeting the FCC deployment timeline?

Multiple risks exist: manufacturing quality issues, launch vehicle reliability problems, space weather affecting satellite operations, unexpected technical failures, regulatory delays in other countries, or accelerated competition reducing demand. Missing the December 2028 deadline (50% deployment) would trigger FCC review and potentially threaten remaining approvals. Space X has historically delivered on aggressive timelines, but space projects are inherently uncertain. Building contingency into schedules is prudent.

Conclusion: A Watershed Moment for Space Infrastructure

The FCC's approval of 7,500 new Starlink satellites is significant because it represents regulatory validation that commercial space-based internet is viable and sustainable. Space X didn't get everything it asked for, but it got enough to build a mature constellation capable of providing genuinely competitive global internet service.

This isn't hype. The technical foundations are proven. Starlink already provides service to hundreds of thousands of customers. Speeds are approaching terrestrial broadband quality. Latency is acceptable for most applications. Coverage spans most inhabited areas. The question was never whether the technology works. The question was whether regulators would allow deployment at scale without catastrophic interference.

The FCC's decision, while partial, answers that question. Space X can proceed with confidence knowing that expansion is regulatory-endorsed. The deferred remaining satellites suggest the FCC wants oversight but isn't blocking growth. That's the outcome Space X needed.

For consumers and businesses, this approval means satellite internet is about to stop being a niche product and become a genuine alternative to fiber and terrestrial wireless. That matters in rural areas with no fiber access. It matters for disaster resilience. It matters internationally in developing nations without infrastructure. The competitive pressure will force traditional ISPs to innovate and improve service. Everyone wins except perhaps incumbent providers relying on local monopolies.

The timeline is ambitious but realistic. If Space X executes as expected, the constellation reaches mature capacity by 2031. Service improvements compound over time. By the end of the decade, satellite internet should be mainstream rather than exotic.

The geopolitical implications are profound but understated. Space-based infrastructure is becoming critical to national security and economic development. The FCC approval positions the U. S. and Space X as dominant players. Other nations are responding with competitive efforts. This infrastructure race will define technology positioning for the coming decades.

Risks remain. Space is hard. Manufacturing at scale is challenging. International approvals will be messier than U. S. approval. Competition will intensify. But the baseline bet that satellite internet is transformative is now backed by regulatory approval from the world's most influential telecom regulator.

We're witnessing infrastructure transformation. In ten years, satellite internet won't be novel. It'll be part of the expected landscape alongside fiber, cellular, and wireless. This FCC approval accelerates that transition. It's not the final word, but it's the word that matters most.

The next chapters play out over years, not months. Monitor Space X's launch cadence, international regulatory decisions, and competitive launches from Kuiper and others. The space-based internet era is real, and the infrastructure buildout has the FCC's blessing. That changes everything.

Key Takeaways

- FCC approved 7,500 new second-generation Starlink satellites, pushing total constellation to 15,000 (deferred remaining 14,988 for future review)

- Second-gen satellites operate across five frequency bands with direct-to-cell connectivity capability, significantly expanding capacity and service capabilities

- SpaceX must launch 50% of approved satellites by December 2028 and remaining 50% by December 2031 per FCC timeline requirements

- Expanded constellation will enable near-global internet coverage with speeds improving from current 50–250 Mbps range toward 150–500 Mbps

- FCC deferred remaining satellites due to interference concerns with other operators and Earth observation systems, showing regulatory oversight is working

- Competition from Amazon Kuiper and other operators will intensify but market is large enough for multiple providers serving different customer segments

- Satellite internet transitions from niche product to mainstream infrastructure, threatening traditional ISP monopolies in rural areas

- Geopolitical implications are significant as space-based internet becomes critical infrastructure and leverage in international relations

Related Articles

- SpaceX's 15,000 Starlink Gen2 Satellites: What It Means [2025]

- SpaceX Lowers Starlink Satellites to Reduce Collision Risk [2025]

- Starlink's Free Internet Push in Venezuela: What It Means [2025]

- SpaceX's 7,500 New Starlink Satellites: What the FCC Approval Means [2025]

- NASA Spacewalk Postponement: What Happened and Why [2025]

- Warner Bros. Discovery Rejects Paramount Skydance Bid: Why Netflix Won [2025]

![SpaceX's 7,500 New Starlink Satellites: What It Means [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/spacex-s-7-500-new-starlink-satellites-what-it-means-2025/image-1-1768084602662.jpg)