Introduction: A Critical Moment for Autonomous Vehicles in America

On a Wednesday afternoon in the US Senate, two of the most powerful forces shaping transportation's future sat across from lawmakers who seemed genuinely unsure whether to accelerate or pump the brakes. Waymo executives and Tesla representatives came to Capitol Hill with a unified message: America needs federal rules for autonomous vehicles now, or China will own this market. But after two hours of testimony and questioning that touched on everything from Chinese-manufactured chassis to children struck by robotaxis, one thing became crystal clear—Congress remains deeply divided on what those rules should even look like.

This wasn't a routine hearing. The stakes are genuinely enormous. The autonomous vehicle industry has moved from "science fiction" to "operational in multiple US cities" in roughly five years. Waymo's robotaxis are picking up actual passengers in San Francisco, Phoenix, and Los Angeles. Tesla is pushing hard on its vision of autonomous driving, even as regulators scrutinize the company's safety practices and marketing claims. And meanwhile, Chinese companies are building autonomous vehicles at scale, backed by government support and technological momentum that's hard for American companies to ignore.

What made this hearing particularly revealing wasn't just what the executives said. It was what the senators didn't agree on. Some lawmakers are concerned that federal regulation will slow innovation. Others worry that without strict oversight, people will die. Some believe the free market should decide winners. Others point to recall investigations being cut by 25 percent and ask how that's supposed to keep roads safe. The hearing exposed real fractures in how Congress thinks about autonomy, competition, liability, and the role of government in managing a technology that's fundamentally reshaping transportation.

This moment matters because the regulatory decisions made in the next 12 to 24 months will likely determine which companies dominate autonomous driving for the next decade. Federal preemption could enable rapid deployment and American competitiveness. Fragmented state-by-state rules could create chaos. And neither outcome is guaranteed. The hearing revealed that lawmakers are nowhere close to consensus, which means the status quo—a patchwork of state regulations, manufacturer discretion, and NHTSA guidance that lacks the force of law—will probably persist for longer than either industry or public safety advocates want.

Let's break down what happened, why it matters, and what it tells us about where autonomous vehicles are actually headed in America.

The Setup: Why This Hearing Happened Now

Autonomous vehicle regulation has been stalled in Congress for years. The industry has been pushing for federal preemption legislation that would allow companies to deploy robotaxis more quickly without navigating 50 different state regulatory frameworks. But every time legislation gets close to passing, something happens—a crash, an incident, a safety concern—that makes lawmakers nervous about moving forward.

Waymo's expansion into Los Angeles and San Francisco, combined with Tesla's increasingly aggressive claims about autonomous capabilities, forced the issue back onto the legislative agenda. The company operates hundreds of robotaxis carrying real passengers on real roads. Tesla CEO Elon Musk has promised "full self-driving" capability and autonomy features that have drawn regulatory scrutiny and public backlash. China's BYD, Baidu, and other companies are deploying autonomous vehicles at scale in Chinese cities. And the US is watching, wondering if it's about to lose a technology race that could be as economically significant as semiconductors or battery manufacturing.

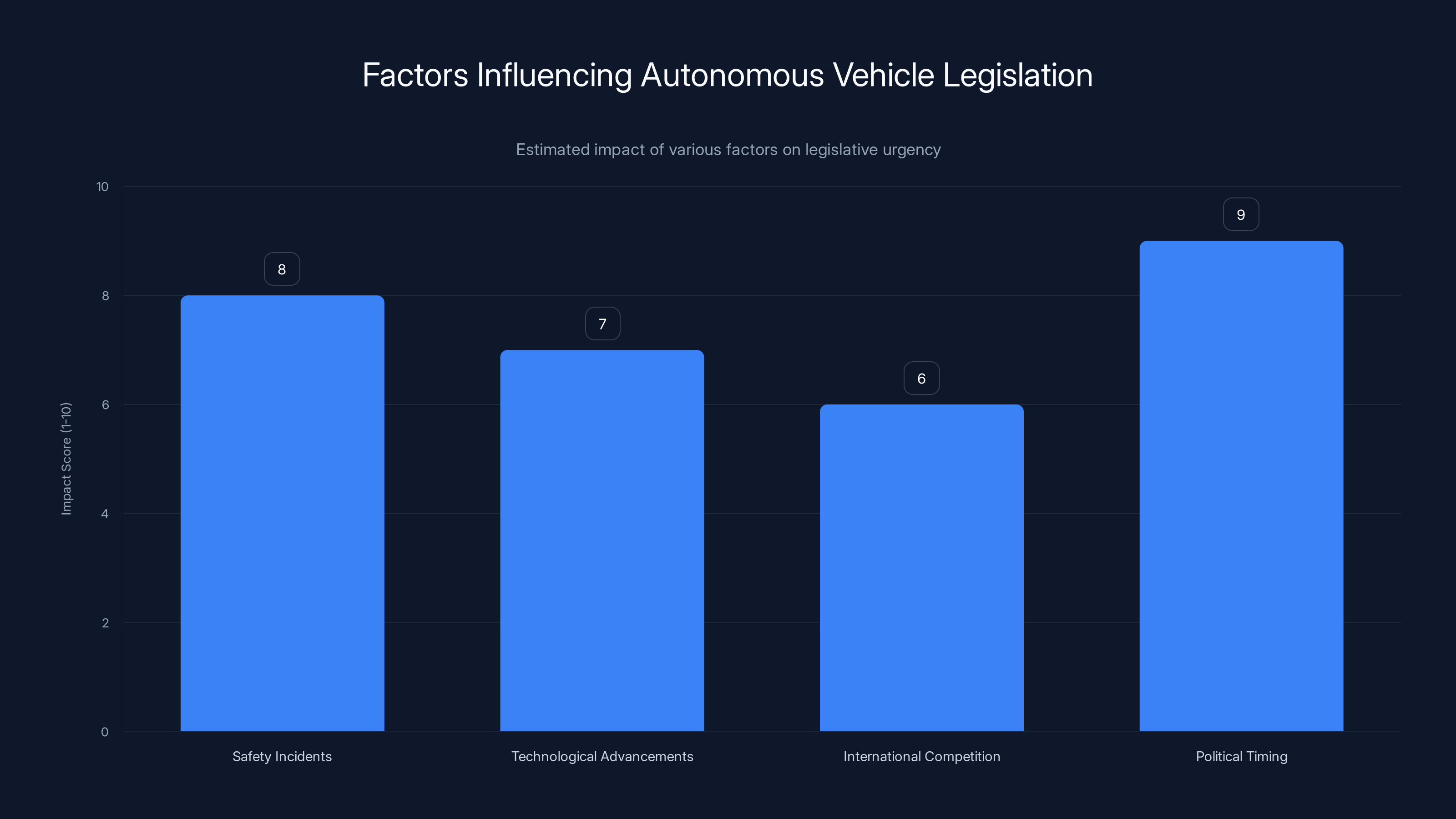

Senator Ted Cruz, who chairs the Senate Commerce, Science and Transportation Committee, scheduled this hearing partly because the committee is working on what's called the Surface Transportation Reauthorization Act—a massive piece of legislation that covers federal funding for highways, transit, and safety programs. That bill is the vehicle through which autonomous vehicle regulation could actually move. It's the right committee, the right moment, and the right political moment to push legislation forward.

But the hearing also happened because safety incidents keep happening. Waymo's vehicles failed to stop behind a school bus in Austin during student pickups—multiple times. A robotaxi struck a child at low speed in Santa Monica. Tesla's removal of radar from its vehicles has drawn concern from safety experts. And the general question of what happens when a robot-driven car hits someone remains legally and technically unresolved. These incidents matter politically because they remind lawmakers that this technology is being deployed in the real world with real consequences, and those consequences aren't theoretical anymore.

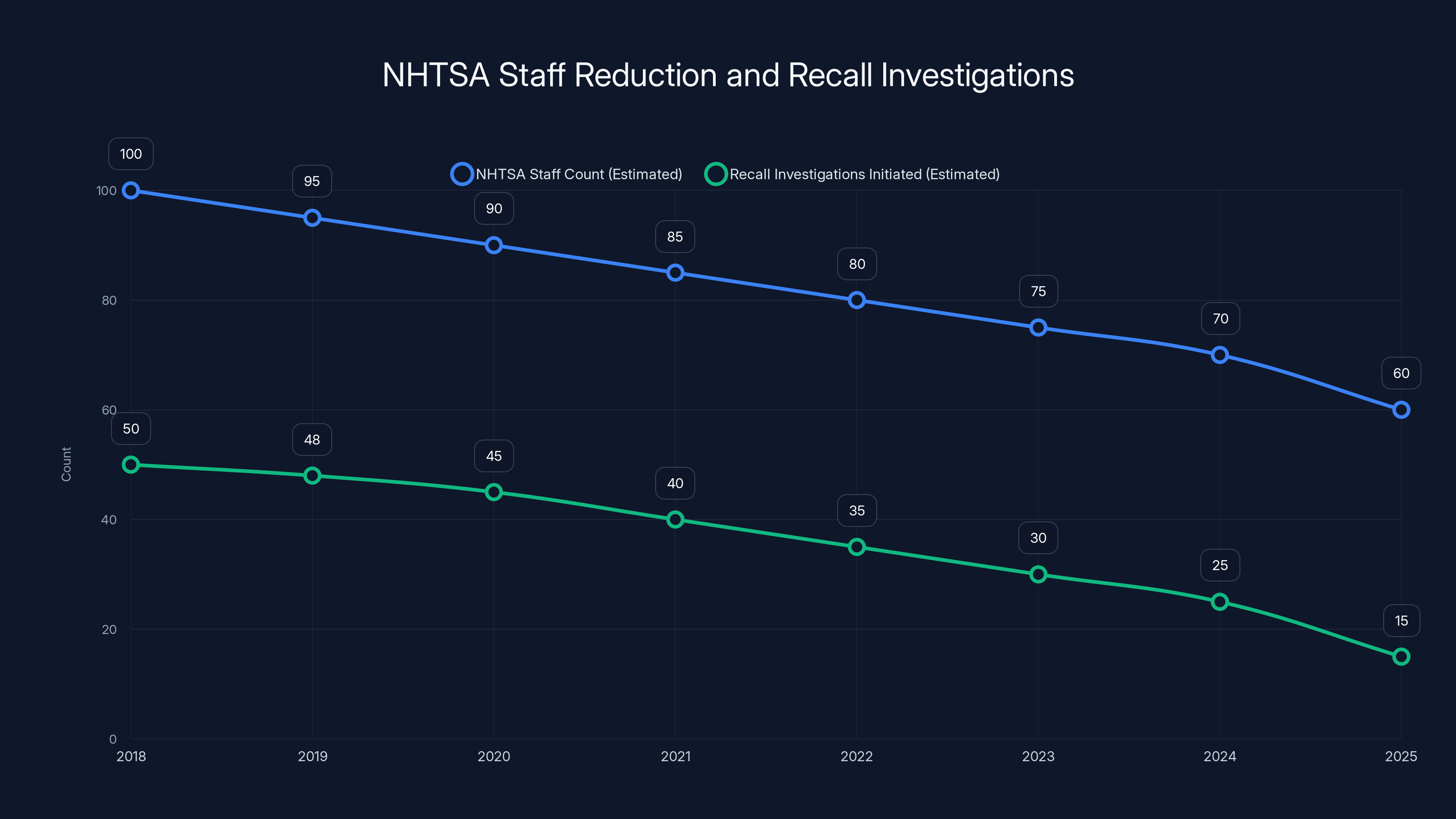

The other context here is NHTSA budget cuts. When Elon Musk took control of the government efficiency agenda, NHTSA lost about 25 percent of its staff. At one point, the Office of Automation—the team responsible for autonomous vehicle oversight—was down to only four people. That means fewer investigations, slower recalls, and less capacity to understand what's actually happening on the road. Senator Maria Cantwell pointed this out directly during the hearing: "Are we going to just continue to let people die in the United States?" It's not subtle messaging.

This hearing was scheduled to force a conversation that Congress has been avoiding: What does responsible federal oversight of autonomous vehicles actually look like?

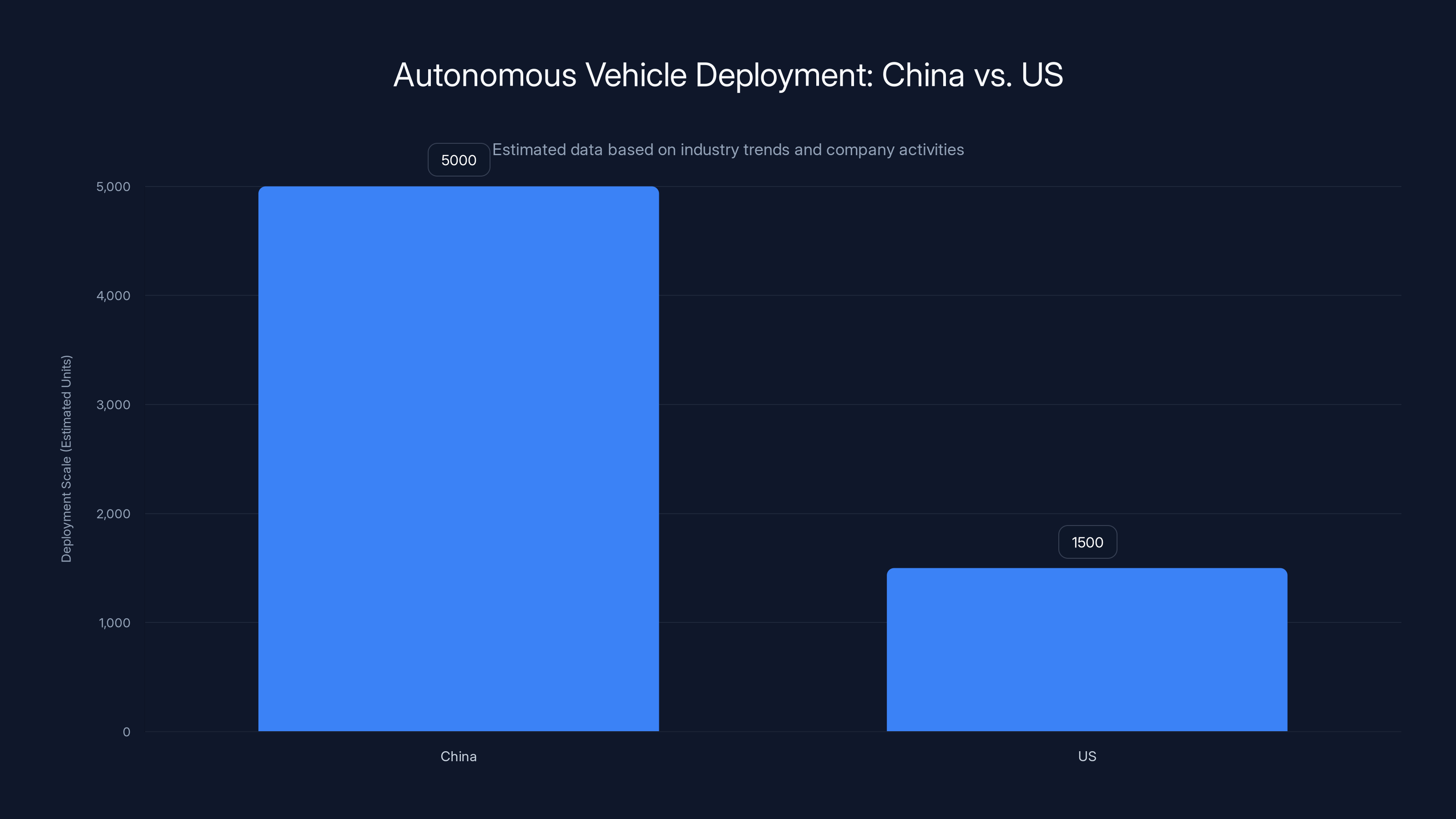

China is deploying autonomous vehicles at a larger scale compared to the US, driven by lower costs and faster regulatory processes. (Estimated data)

Waymo's Position: Safety First, But We Need Federal Rules

Waymo's testimony centered on a few key points. First, the company emphasized that safety is its guiding principle. Mauricio Peña, Waymo's chief safety officer, opened by stating that Waymo's vehicles are designed and tested to prevent exactly the kinds of incidents that happened in Austin and Santa Monica. He talked about the company's approach to edge cases—those weird, low-probability situations that are hardest to predict and defend against.

But here's where Waymo's message got complicated. The company used incident examples to argue that its safety systems are working—that when there's a problem, the vehicles handle it responsibly. The failure to stop behind the school bus? Waymo said it was collecting data across different lighting patterns and conditions, integrating those learnings into the system. The incident in Santa Monica where a robotaxi struck a child? Waymo emphasized that it happened at low speed and that the company is continuously improving its object detection and response times.

This is a tricky argument to make in front of a Senate committee. On one hand, it's honest—autonomous systems do learn from incidents, and low-speed collisions are better than high-speed ones. On the other hand, it sounds like the company is saying "Yes, our vehicles hit kids, but don't worry, we're learning from it." That's not the kind of reassurance that makes nervous senators feel better.

Waymo's biggest challenge during the hearing was questions about its decision to use a Chinese-made vehicle for its next-generation robotaxi platform. This isn't a small issue politically. Right now, Waymo's robotaxis are based on modified Chrysler Pacificas—American cars. But the company is moving toward a purpose-built robotaxi chassis, and it's considering a Chinese design. Senators immediately seized on this as a national security and competitiveness issue. Why would Waymo use a Chinese platform when the US has automotive manufacturing capacity?

Waymo's response was essentially economic: Chinese manufacturers can build better, cheaper robotaxi platforms right now, and using that platform actually allows Waymo to deploy more aggressively and prove the value of the service. But to a committee room full of senators worried about China's technological advancement, that answer felt like an admission that American manufacturers can't compete. That's a politically sensitive message in an election year.

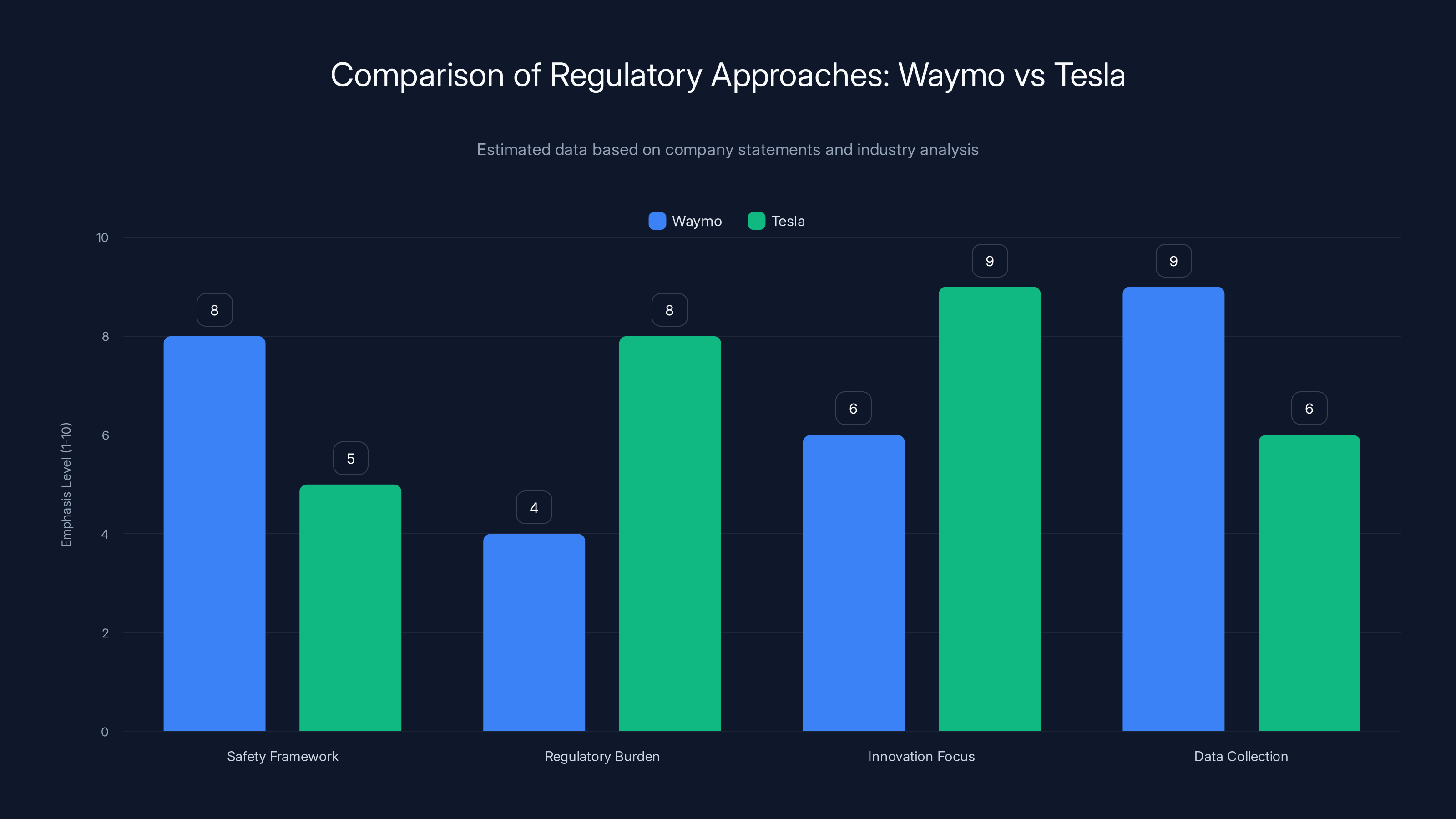

The other part of Waymo's testimony focused on the need for federal preemption and safety frameworks. The company argued that a patchwork of state rules makes it harder to deploy robotaxis consistently and slows down the pace at which the company can expand to new cities. Federal regulation would create uniform safety standards while allowing rapid deployment. Waymo's logic is sound from a business perspective—it's easier to meet one set of federal rules than 50 different state rules.

But Waymo's testimony also revealed the company's core vulnerability: it's operating a service that the public doesn't fully trust, deploying vehicles that occasionally fail in visible ways, and arguing for federal rules that would make it even easier to expand. That's a tough sell in a room where some senators represent states that have had bad experiences with Waymo robotaxis or where traditional taxi and rideshare companies are lobbying hard against autonomous vehicle deployment.

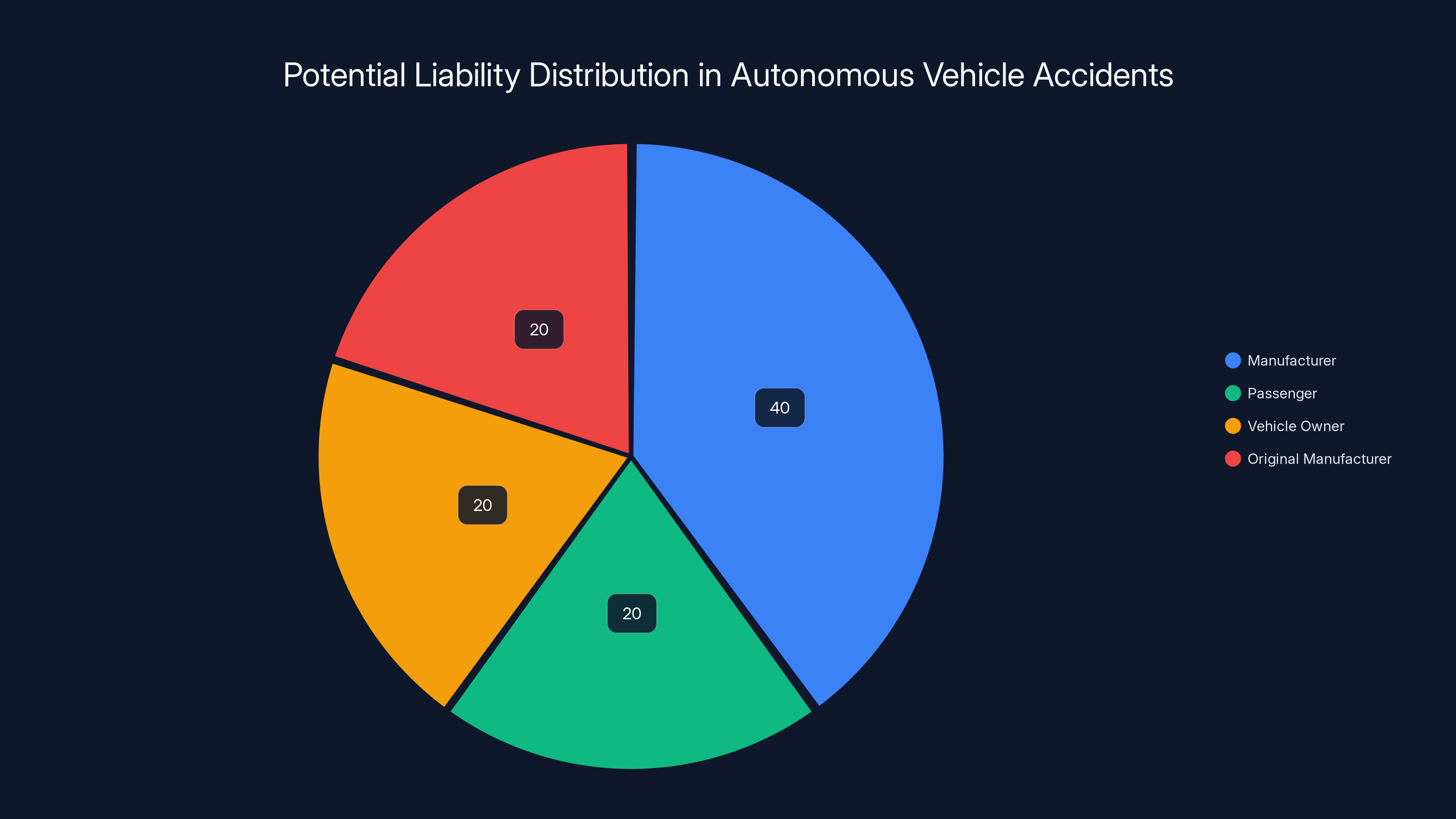

What Waymo didn't adequately address is the liability question. If a Waymo robotaxi hits someone, who's responsible? The company? The owner? The passenger? Right now, that's legally murky. Waymo paid settlements for some incidents, but there's no clear regulatory framework establishing liability standards. That matters because without clear liability rules, insurance becomes unpredictable, which makes deployment riskier, which makes investors nervous. Waymo sidestepped this question rather than tackle it head-on, which senators noticed.

NHTSA's staff reduction by 25% has correlated with a significant decrease in recall investigations from 50 in 2018 to an estimated 15 in 2025. Estimated data highlights the impact of staffing on agency capacity.

Tesla's Approach: Skepticism of Regulation, Confidence in Technology

Tesla's testimony took a different approach than Waymo's. Rather than emphasize safety incidents and how the company learns from them, Tesla pushed back against what it called "outdated" federal regulations that inhibit innovation. Lars Moravy, vice president of vehicle engineering at Tesla, opened by saying that federal vehicle regulations haven't kept up with modern technology. He's not wrong—federal automotive safety standards were written for traditional internal combustion vehicles with human drivers. Electric vehicles, autonomous driving systems, and over-the-air software updates challenge those standards in fundamental ways.

Tesla's argument was that America needs "American leadership" for autonomous vehicle rules, that China is moving faster with less regulatory burden, and that excessive caution now will result in American companies losing the global market. It's a familiar argument from the tech industry: let us innovate, trust us to self-regulate, and bad things won't happen.

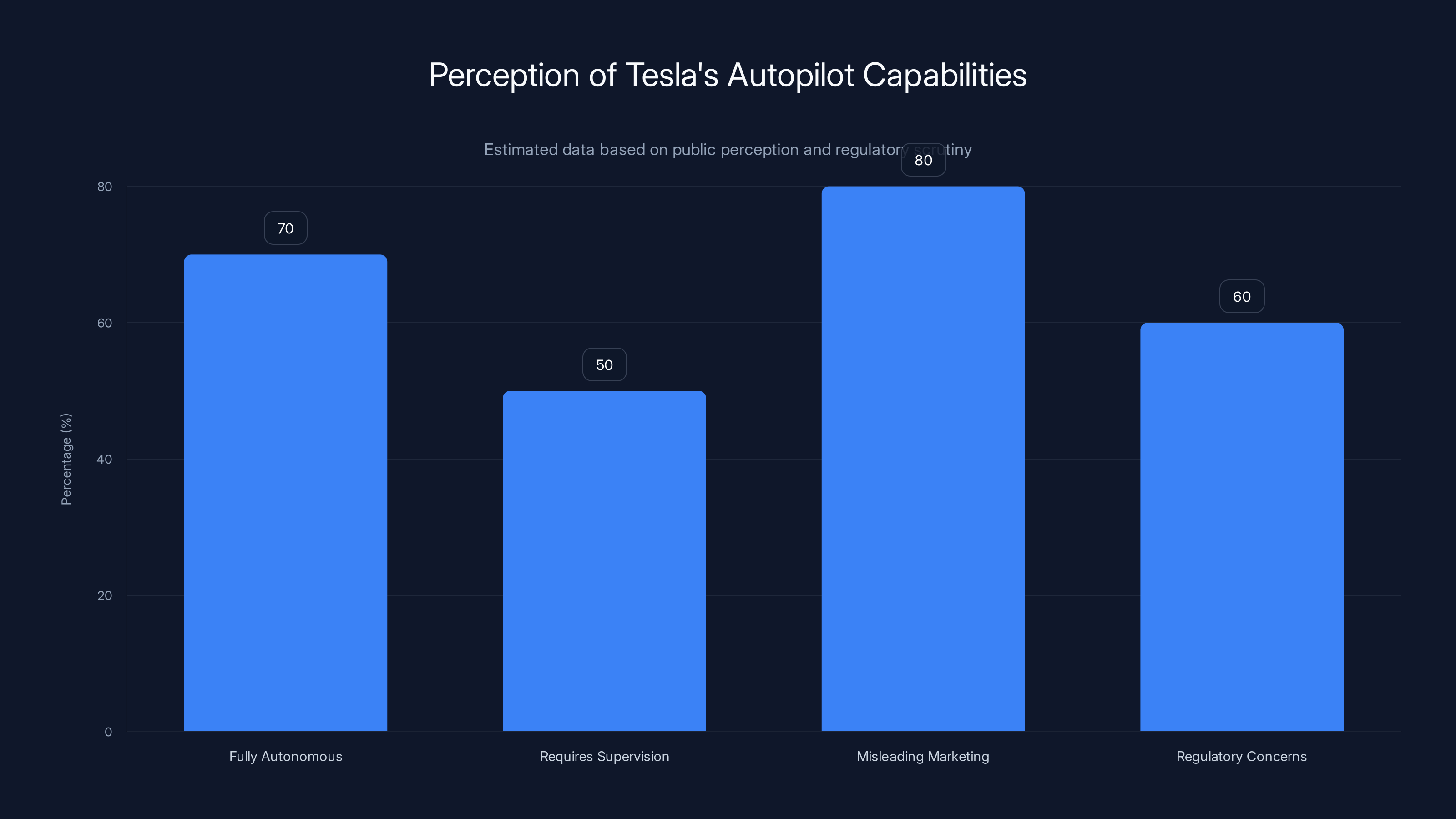

But Tesla faced much harder questioning than Waymo, partly because of the company's history with what regulators and senators view as deceptive marketing. Tesla spent years marketing its Autopilot feature as something closer to autonomous driving than it actually is. The company used names like "Autopilot" and "Full Self-Driving" that imply capabilities the car doesn't actually have. Drivers have crashed while relying on these features to do more than they can do. People have died.

Senator Maria Cantwell put it bluntly: "Tesla was allowed to market their technology, which they knew needed human supervision, as Autopilot because there were no federal guardrails." She's right. There were no guardrails. Tesla essentially got to define what its own features did, and regulators moved slowly to respond. Now there's a large population of Tesla owners who think their cars can drive themselves when they really can't. That's created a safety problem and a regulatory problem simultaneously.

Tesla was also asked about its decision to remove radar from its vehicles and rely entirely on camera-based perception. This is a technical choice that's genuinely controversial within the autonomous driving industry. Radar and cameras are complementary technologies—radar is better in bad weather and at detecting fast-moving objects, while cameras are better at identifying what things are. Removing radar makes vehicles more dependent on camera performance and potentially more vulnerable in certain conditions. Tesla argues that camera-only systems can be superior if you have enough processing power and good software. But to many safety engineers, removing redundancy is a step backward.

Tesla also faced hard questions about binding arbitration. This is a less visible but crucial issue. When you buy a Tesla, you agree to arbitration clauses that prevent you from suing the company in court if something goes wrong. Instead, disputes go to private arbitration. Senators asked whether Tesla would commit to allowing autonomous vehicle injury cases to go to court rather than arbitration. Tesla didn't give a clear yes. That matters because binding arbitration makes it harder for victims to get compensation and makes it harder for patterns of problems to become visible to regulators. One victim's experience stays private. If there are ten victims, each going through arbitration separately, nobody can see that there's a pattern.

Unlike Waymo, Tesla didn't really commit to the idea of specific federal regulation. The company seemed to prefer a lighter regulatory touch—maybe some safety standards, but not the kind of detailed oversight that would slow down deployment or constrain how the company designs vehicles. That probably resonates with some senators, but it doesn't reassure others who are concerned that Tesla's track record suggests the company won't self-regulate responsibly.

What Tesla did effectively was invoke the China threat. China is deploying autonomous vehicles at scale. China's regulatory burden is lighter. If the US overregulates, Chinese companies will dominate this market. That argument carries weight in Congress because everyone agrees that losing technological races to China is bad for American competitiveness and geopolitical standing. But it's also a pressure tactic—"regulate us lightly or China wins." That's not a strong foundation for good public policy.

The China Factor: Competition and Vulnerability

The elephant in the room throughout this hearing was China. Both Waymo and Tesla spent significant time arguing that federal regulation is necessary to keep the US competitive with China. But what does that actually mean, and is it a real threat?

China is deploying autonomous vehicles at significant scale right now. Companies like Baidu, Di Di, and BYD are operating robotaxi services in Chinese cities. The Chinese government supports autonomous vehicle development actively, through funding, regulatory support, and integration with ride-hailing platforms. The cost structure is lower in China because labor is cheaper, manufacturing is cheaper, and regulatory approval moves faster. So Chinese companies can develop and deploy autonomous vehicles more cheaply and more quickly than American companies operating in the US regulatory environment.

But there's a crucial context here: China's autonomous vehicles are operating in Chinese cities, for Chinese customers, using Chinese infrastructure and Chinese data. They're not operating in the US. The US market is still open, but it's also significantly more demanding in terms of expectations around safety, liability, and consumer protection. An autonomous vehicle that works well in Beijing might not work well in Los Angeles, not because of technology but because of different driving patterns, weather, infrastructure, and legal liability standards.

Waymo's argument that it needs to use a Chinese-manufactured platform to compete reveals something important: the US doesn't currently have a cost-competitive manufacturer of robotaxi-specific vehicles. That's a real gap. Tesla is trying to build manufacturing capability, but it's years away from having purpose-built robotaxi production. Existing US automakers like Ford or General Motors are moving slowly on autonomous vehicles, partly because they have existing dealer networks and legacy business models that create perverse incentives. So right now, if you want to build robotaxis quickly and cheaply, Chinese manufacturing looks attractive.

Senators took this seriously as a competitiveness issue. The concern is that if US companies can't manufacture robotaxis competitively, they'll become dependent on Chinese manufacturers. Over time, that dependency could translate into technological dependency, supply chain vulnerability, and ultimately market share that flows to Chinese companies. It's the same concern that drove semiconductor policy and battery manufacturing policy—the question of whether critical technology supply chains should be in the US or subject to foreign control.

What the senators didn't fully explore is whether US regulatory standards might actually be an advantage over time. If the US insists on stronger safety standards, better liability frameworks, and more consumer protection, then US-developed autonomous vehicles might be more trustworthy and deployable in wealthy markets than Chinese vehicles built under different regulatory regimes. That's a long-term play, not a short-term one. But it's possible that the regulatory caution that frustrates tech companies is actually protecting American interests in a different way.

The other part of the China story is data. Autonomous vehicles generate vast amounts of data—sensor data, operational data, traffic pattern data. That data is valuable for improving autonomous systems and for other applications. If Chinese companies are the ones collecting data in major US markets, that data advantage flows to China. If US companies collect that data, it stays in the US. That's part of why the robotaxi platform question matters so much—it's not just about the vehicle itself, it's about where the data flows and who controls it.

Neither Waymo nor Tesla adequately addressed this question. Both companies collect significant amounts of data from their operations. Neither company was asked—or if asked, didn't clearly answer—whether that data would be shared with the government, kept proprietary, or potentially exposed to foreign access. In a hearing that spent a lot of time on China competitiveness, that seems like an important gap.

Safety incidents and political timing are the most significant factors driving the urgency of autonomous vehicle legislation. Estimated data.

Safety Incidents: The School Bus Problem and Santa Monica Collision

One of the most concrete issues that senators focused on was safety incidents. Waymo's vehicles failed to stop properly behind school buses in Austin, Texas, during student pickups. A Waymo robotaxi struck a child at low speed in Santa Monica, California. These aren't theoretical problems—they're things that actually happened, captured on video, and highlighted in news coverage.

Waymo's response was that these incidents are exactly why autonomous vehicles need to improve continuously, and why the company invests heavily in safety. But that's a response that assumes people trust Waymo to improve on its own. Senators didn't seem convinced. A school bus safety problem is particularly sensitive because school buses are where children are—the ultimate vulnerable population. If Waymo's system can't reliably recognize and respond to school buses, that's not a minor software bug. That's a fundamental challenge in how the system perceives the world.

Waymo explained that it was collecting data across different lighting patterns and conditions, and integrating those learnings to prevent the problem from happening again. Technically, that makes sense. Real-world edge cases are hard to replicate in simulation. You need actual operational data to understand how a system fails under different conditions. But the fact that Waymo discovered this problem through actual operations—with real children waiting to board buses—rather than catching it in testing is exactly what makes senators nervous.

The Santa Monica incident was also revealing. A Waymo robotaxi struck a child at low speed. The child wasn't seriously injured, but the fact that the collision happened at all raises questions about the quality of the company's object detection and collision avoidance systems. Waymo responded that the incident happened at low speed and that the company is working to prevent similar incidents. But to a senator representing California voters, the message that a driverless car hit a kid—even at low speed—is not reassuring.

What became clear during this part of the hearing is that there's a fundamental tension in how to think about autonomous vehicle safety. On one hand, autonomous vehicles might eventually be safer than human drivers when they're fully mature and deployed at scale. Human drivers are terrible—they text, they drink, they fall asleep, they drive aggressively. If autonomous vehicles can eliminate driver error, lives will be saved.

On the other hand, we're nowhere near "fully mature" autonomous vehicles. We're in the early deployment phase, where the systems are still learning, where incidents still happen, and where the question of whether they're actually safer than human drivers is still empirically open. Waymo can point to the millions of miles it has driven with relatively few serious incidents, and that's a valid data point. But people are still getting hit. Systems are still failing. And nobody knows if those failure rates will continue to improve or if they'll plateau at some acceptable level that still includes regular incidents.

The school bus problem also raised a question about data transparency. How would regulators know if this problem was systemic or isolated? Waymo has a responsibility to report safety incidents, but the company also controls the data around its operations. If there's a problem that the company doesn't notice or chooses not to report, regulators might not find out until there's a serious injury or death. That's why some senators pushed for stronger NHTSA oversight and investigation capability. You can't regulate something if you don't have visibility into it, and NHTSA's staffing levels mean it doesn't have great visibility right now.

This is where the regulatory framework question becomes practical and urgent. What should the reporting requirements be for autonomous vehicle incidents? Who should investigate them? What's the standard for whether a problem is serious enough to warrant a recall or a change in deployment? These are questions that Congress needs to answer if it's going to regulate autonomous vehicles responsibly.

Liability and Legal Framework: The Unresolved Question

One of the biggest topics that came up during the hearing, but that neither company adequately addressed, was liability. If a Waymo robotaxi causes an accident, who's responsible? Is it Waymo? The passenger? The vehicle owner? The original vehicle manufacturer? Right now, that's not clearly defined in federal law.

This matters enormously because without clear liability rules, the entire insurance and risk structure for autonomous vehicles becomes murky. Insurance companies need to know who they're insuring and for what. Manufacturers need to understand what their exposure is. Consumers need to know whether they're liable for accidents that happen when their car is driving itself. Without clear rules, the entire market becomes riskier and moves more slowly.

Waymo and Tesla both benefit from regulatory ambiguity on this question, because it means they can define liability in ways favorable to themselves. If federal law explicitly said "the manufacturer is liable for autonomous driving accidents," that would increase Waymo's insurance costs and expose the company to more lawsuits. So both companies have an incentive to avoid pushing for clear liability rules. Instead, they're pushing for safe harbor provisions—legal protections that shield them from liability for autonomous vehicle accidents that happen while the system is operating.

That's a terrible outcome from a public policy perspective, because it means victims of autonomous vehicle accidents might not have clear recourse. If there's no liability, there's no incentive for companies to prevent accidents. The whole legal system for torts—the idea that if you cause harm, you have to pay for it—breaks down. Senators understood this, but neither company committed to supporting clear liability frameworks. They committed to safety, but not to liability.

This is where the gap between what companies want and what society needs becomes really visible. Companies want to deploy quickly, limit their liability, and keep costs low. Society wants safe vehicles, clear accountability when things go wrong, and fair compensation for victims. Federal legislation needs to bridge that gap, and right now, it's not clear that Congress knows how to do that in a way that makes everyone happy.

One specific liability question that came up was arbitration clauses. Tesla requires arbitration for customer disputes. That means if a Tesla causes an accident, the victim might not be able to sue in court—they'd have to go through private arbitration. That's good for Tesla (faster resolution, less visibility) but bad for victims and bad for public understanding of problems (each case stays private). Senators pushed on this, but Tesla didn't commit to allowing autonomous vehicle injury cases to escape arbitration. That's a political vulnerability for Tesla and a sign that the company is willing to protect its legal interests over victim interests.

Waymo didn't face the same arbitration question because Waymo operates a service (robotaxi) rather than selling vehicles. But the company faces similar liability questions around what happens when a robotaxi causes an accident. Does Waymo pay for medical bills? Property damage? Lost wages? What's the cap on liability? Waymo didn't provide clear answers, which means the company is probably still figuring this out, which means the regulatory framework hasn't moved far enough along to require companies to have definitive answers.

This is one area where federal legislation is genuinely necessary. States can't adequately regulate liability for vehicles that cross state lines and operate in complex interstate commerce. Federal law should establish clear liability standards, insurance requirements, and victim compensation mechanisms. But that legislation requires Congress to balance company interests (they want limited liability) against victim interests (they want full compensation) and public interests (we want incentives for safety). None of those groups was fully represented in this hearing. It was mostly companies explaining what they want, and senators trying to figure out what makes sense.

Estimated data shows that a significant portion of the public perceives Tesla's Autopilot as more autonomous than it is, highlighting the impact of Tesla's marketing strategies.

Remote Operation: The Backdoor Solution

Another technical question that senators asked about was remote operation. If an autonomous vehicle gets stuck or encounters a situation it can't handle, can a human operator take control from a remote location? Both Waymo and Tesla said yes, they have remote operation capabilities or are developing them. But what does that really mean for regulation?

Remote operation seems like a good safety feature on the surface. If something goes wrong, a human can jump in and take control. But it also creates a regulatory gray area. If a vehicle has a human operator monitoring it remotely, is it really an autonomous vehicle? Or is it just a vehicle with a remotely located driver? The answer matters because it affects what regulations apply.

Right now, there's no clear federal guidance on remote operation. How much latency is acceptable (i.e., how much delay between when the remote operator sees something and when the vehicle responds)? What's the quality standard for video transmission? How many vehicles can one remote operator handle? What's the liability if the remote operator makes a mistake? These are all questions that need answers for remote operation to be a viable regulatory approach.

Waymo explained that its remote operation capabilities are used in limited situations—when a vehicle is stuck in an unusual situation or when traffic is too complex for full autonomy. The company didn't provide details on how often remote operation is needed or what triggers it. That's important information for regulators because if remote operation is needed frequently, that's evidence that the autonomous system isn't actually autonomous for normal operation. And if remote operation is rare, then it's not the safety backup that people imagine.

Remote operation is also an employment question. If you need human operators standing by to remotely handle vehicles, that's jobs. Some of those jobs would be in the US (remote operators), and some of those jobs wouldn't exist (professional drivers). The net employment effect depends on how many operators are needed relative to the number of vehicles deployed. But it's another way that autonomous vehicles create winners and losers in the labor market, and that's a topic Congress was mostly avoiding.

The deeper issue with remote operation is that it creates a kind of regulatory escape hatch. If companies can claim that vehicles have human oversight via remote operation, it becomes harder to argue that those vehicles are truly autonomous and subject to autonomous vehicle regulations. But if the remote operation is really rare and mostly theoretical, then it's not providing meaningful safety benefits. Regulators need to figure out whether remote operation is a real safety mechanism or just a way to make autonomous vehicles seem safer than they are.

NHTSA's Capacity Problem: Can Regulators Keep Up?

Senator Cantwell's point about NHTSA losing 25 percent of its staff, and the Office of Automation being down to four people at one point, was one of the most important things said during the entire hearing. Because you can talk all you want about safety standards and liability frameworks, but if the agency responsible for enforcing them doesn't have the people to do the job, those standards don't mean much.

NHTSA is supposed to investigate safety issues, launch recalls, and oversee autonomous vehicle development. But the agency is underfunded and understaffed. Right now, it has capacity to look at some problems but not others. That means if there are issues with autonomous vehicles that NHTSA hasn't discovered yet, it might take a long time before the agency catches them. And if Waymo or Tesla knows about problems but doesn't voluntarily report them, NHTSA might never catch them.

This is where federal legislation becomes not just about rules but about resources. If Congress is going to pass autonomous vehicle legislation, that legislation needs to include funding for NHTSA to hire more staff, buy better diagnostic tools, and build capability to understand what's happening on the road. Otherwise, regulation is just words on paper.

Cantwell pointed out that NHTSA initiated significantly fewer recall investigations in 2025 compared to previous years. That's not because vehicles got safer—it's because the agency doesn't have the capacity to investigate. That's a huge problem if you're trying to deploy a brand-new technology and keep it safe. How are we going to know if autonomous vehicles are actually safe if the regulatory agency doesn't have the resources to figure it out?

Both Waymo and Tesla avoided directly addressing the NHTSA capacity question. They were there to argue for their positions, not to help senators figure out how to fund the regulatory agency. But that's exactly what Congress needs to think about. If you're going to regulate autonomous vehicles, you have to invest in the regulatory apparatus. That costs money. And in a budget-conscious Congress, spending money on government agencies is politically unpopular. But without that spending, you're just pretending to regulate.

There's also the question of whether NHTSA has the technical expertise to regulate autonomous vehicles effectively. Self-driving cars involve machine learning, sensor systems, software updates, and edge cases that traditional automotive safety engineers might not fully understand. NHTSA needs to hire not just automotive engineers but also machine learning experts, sensor specialists, and software engineers. That's expensive and competitive with tech industry salaries. It means the federal government needs to pay market rates for experts, which is something Congress is often reluctant to do.

This is a structural problem with how the US government regulates technology. Federal agencies are always behind the curve because they're underfunded, understaffed, and unable to compete for talent with private industry. That might be acceptable for older, more stable technologies where change is slow. But for something like autonomous vehicles that's evolving rapidly and deploying into the real world in real-time, the gap between regulatory capacity and technology development is a genuine safety risk.

Estimated data suggests manufacturers might bear the largest share of liability in autonomous vehicle accidents, highlighting the need for clear legal frameworks.

The Marketing Problem: How Much Should Companies Be Allowed to Claim?

Senator Cantwell's critique of Tesla's marketing practices was blunt and well-documented. Tesla spent years marketing Autopilot as something closer to autonomous driving than it actually is. Drivers watched YouTube videos of Teslas appearing to drive themselves and believed their cars could do things they actually couldn't. Some drivers have died in accidents that occurred because they trusted Autopilot to do more than it could do.

This raises a fundamental question: what should companies be allowed to claim about autonomous features? Tesla argues that it's using clear language and that drivers are responsible for understanding the limitations of Autopilot. The company points to disclaimers and warnings that appear when you activate the feature. But studies have shown that many Tesla drivers misunderstand what Autopilot can do, and some have built dangerous trust in the system.

There's a balance between allowing companies to market their technology and preventing them from creating false impressions that lead to dangerous behavior. Right now, that balance is tipped toward companies. Marketing language like "Autopilot" and "Full Self-Driving" sets expectations that the technology doesn't meet. If federal legislation includes marketing standards—rules about what companies can claim and how they have to present limitations—that could reduce the gap between what people think these systems can do and what they can actually do.

The hearing didn't result in specific marketing standards being proposed, but it did establish that this is a topic Congress cares about. That's important because it suggests that future federal legislation might include marketing guardrails that companies like Tesla haven't had to deal with before.

Waymo was also asked about how clearly it represents its service to customers. Waymo is generally better at setting realistic expectations about what its robotaxis can do because the company operates in a controlled environment where riders sign up knowing they're getting an autonomous vehicle. But as Waymo expands to new cities and new use cases, the question of how clearly the company sets expectations will become more important.

The deeper issue here is that marketing practices reflect what companies think they can get away with. Right now, the FTC doesn't have clear guidelines on autonomous vehicle marketing. That means companies can use whatever language they want, as long as it's technically not false. But "technically not false" and "actually true about what people will experience" are different things. Legislation could close that gap by requiring companies to use specific, clear language about what their systems can and can't do in different conditions.

One interesting dynamic is that stricter marketing standards might actually help companies like Waymo, which already sets realistic expectations. Companies that have built their brand on clarity and accuracy would benefit from regulations that punish marketing exaggeration. Tesla, which has benefited from aggressive marketing language, would be hurt by such regulations. So there's a competitive dimension to marketing standards that senators probably should think about more carefully.

State vs. Federal Regulation: The Federalism Question

One of the key tensions revealed during the hearing is whether autonomous vehicles should be regulated at the federal level or at the state level. Waymo and Tesla both pushed for federal preemption—the idea that the federal government should set one standard that applies nationwide, and states shouldn't be allowed to impose additional requirements.

The companies' argument is compelling from a business perspective. Operating under 50 different state regulatory frameworks is expensive and slow. Federal preemption would allow faster deployment and lower costs. But there are also strong arguments for state regulation. States have different road conditions, different driving cultures, different safety priorities, and different relationships with their citizens. A one-size-fits-all federal standard might not account for those differences.

The hearing revealed that senators are divided on this issue. Some senators seem sympathetic to the idea that federal preemption would speed up autonomous vehicle deployment. Others worry that federal preemption would prevent states from protecting their citizens if federal standards are inadequate. Senators from states where Waymo or Tesla operations have caused problems (like California) might be less enthusiastic about federal preemption that would prevent the state from imposing additional safeguards.

Cantwell's point about states "filling the void" when federal standards are weak or inadequately enforced is important. If NHTSA doesn't have the capacity to investigate autonomous vehicle incidents or doesn't impose strong enough standards, states will try to regulate on their own. That leads to the patchwork that the companies don't want. But the alternative—federal preemption with weak standards—could be worse from a public safety perspective.

Federal legislation will probably need to include a compromise on this issue. The federal government could preempt states from imposing conflicting rules on autonomous vehicle operation, while still allowing states to address safety issues that affect their residents. Or the federal government could set a floor (minimum standards that all states must enforce) while allowing states to impose stricter standards if they choose to. These are policy questions that require balancing competing values, and the hearing didn't resolve them.

The political reality is that senators from states with large tech industries (California, Washington) might be more sympathetic to federal preemption and lighter regulation. Senators from states without major autonomous vehicle operations might be more skeptical. That means the legislation that actually passes, if anything passes, will probably reflect the political balance of power in Congress rather than the optimal policy outcome.

Waymo emphasizes safety frameworks and data collection, while Tesla focuses on reducing regulatory burden and promoting innovation. (Estimated data)

What the Hearing Revealed About Congressional Fractures

One of the most revealing aspects of the hearing was not what was said but what wasn't agreed upon. Senators on different sides of the issue asked pointed questions that suggested they have fundamentally different views about whether autonomous vehicles should be deployed quickly or whether safety should come first.

Some senators seemed to accept the argument that light regulation is necessary for American competitiveness with China. These senators seem sympathetic to the idea that companies should be able to deploy rapidly, test in the real world, and improve systems based on operational data. That's essentially the Silicon Valley "move fast and break things" philosophy applied to autonomous vehicles.

Other senators seemed deeply concerned about safety and uncomfortable with the idea of treating public roads as testing grounds for new technology. These senators want stronger oversight, more investigation capacity, and clear liability frameworks before companies expand autonomous vehicle operations. They seem to believe that it's better to move slowly and get safety right than to move fast and deal with accidents.

These aren't positions that are easy to reconcile legislatively. If Congress passes legislation that enables rapid deployment with light oversight, safety advocates will criticize it. If Congress passes legislation that imposes strong safety requirements and slow processes, industry advocates will criticize it as anti-competitive. The fact that the hearing didn't bring Congress closer to consensus suggests that this debate will be difficult and protracted.

There's also a generational dimension. Younger senators might be more tech-optimistic and more willing to accept the idea that autonomous vehicles will eventually be safer than human drivers, so the temporary increase in risk from deployment is worth it. Older senators might be more skeptical of that logic and more protective of the status quo. This isn't a simple left-right political divide—it's a fundamental difference in how people think about technology risk and innovation.

The presence of China in the conversation also changed the tone of the hearing. When senators talk about autonomous vehicles in isolation, they focus on safety. But when the conversation includes China competitiveness, senators start thinking about speed and market dominance. That's a natural shift, but it also means that the final legislation might be shaped more by geopolitical competition than by genuine safety analysis.

What didn't happen at the hearing is that nobody walked away thinking Congress is close to passing comprehensive autonomous vehicle legislation. Cruz said the legislation might move as part of the Surface Transportation Reauthorization Act, but that was more of a procedural prediction than a commitment to actually pass something. Both industry representatives left with their positions intact. No consensus emerged on what the legislation should actually include.

The Manufacturing and Supply Chain Angle

One issue that the hearing touched on but didn't fully explore is the manufacturing and supply chain question. Waymo's potential use of a Chinese-manufactured vehicle platform raises fundamental questions about where autonomous vehicles will be built, what components will come from where, and what that means for American industrial capacity.

Right now, the US has world-class expertise in autonomous vehicle software and AI (Waymo, Tesla, Uber ATG, others). But the US doesn't have a strong position in manufacturing of autonomous vehicle platforms. Traditional automakers like Ford and GM are moving slowly. Tesla is building manufacturing capability but is years away from mass production of purpose-built robotaxis. So Waymo's interest in a Chinese platform makes economic sense—the platform can be built cheaper and faster in China than in the US.

But that creates a strategic vulnerability. If US companies become dependent on Chinese manufacturing for autonomous vehicle platforms, that's a supply chain risk. If tensions with China increase, that supply chain could be disrupted. If US companies want to maintain control over the full technology stack, they need manufacturing capacity.

The hearing didn't really address whether federal legislation could or should incentivize US manufacturing of autonomous vehicle platforms. You could imagine policies that do this—tax credits for domestic manufacturing, loan programs to build new factories, tariffs on imported autonomous vehicle components. But those policies would also increase costs and potentially slow deployment, which companies don't want.

This is another area where there's tension between what's good for American competitiveness (domestic manufacturing) and what's good for companies (fast, cheap deployment). Federal legislation will probably need to navigate this tension somehow, maybe by supporting research and development for US manufacturing without requiring it for all vehicles.

The supply chain question also includes sensors, computers, and software components. Where should those be made? Should there be restrictions on what foreign components can be used in autonomous vehicles? Should there be requirements for certain components to be manufactured in the US? These are genuinely complicated questions with no obvious answers, and the hearing suggested they're not yet on Congress's agenda.

Timeline Uncertainty: When Will Something Actually Happen?

Probably the most important thing revealed by the hearing is that Congress doesn't know when it will actually pass autonomous vehicle legislation, or what that legislation will contain. Cruz suggested that autonomous vehicle provisions might be included in the Surface Transportation Reauthorization Act, which is currently being developed. But the timeline for that legislation is uncertain, and the content is even more uncertain.

Typically, major federal legislation takes years to develop, debate, and pass. The autonomous vehicle hearing happened in 2025, but that doesn't mean legislation will pass in 2025 or even 2026. It might take another 2-3 years of debate, committee work, and negotiations before something actually gets to the president's desk. In the meantime, companies will continue deploying autonomous vehicles under the current patchwork of state regulations and NHTSA guidance.

That timeline matters because it means autonomous vehicles will probably be deployed at increasing scale before there's a comprehensive federal framework. Waymo and Tesla and other companies will expand their services, accumulate more operational data, and likely cause more safety incidents. Each incident will reignite the debate about whether deployment is happening too fast. But the legislative process moves slowly, so it might not actually move faster than deployment.

This creates a situation where the regulatory process is playing catch-up rather than leading. Ideally, you'd want regulations to be in place before technology deployment reaches scale. But for autonomous vehicles, that's probably not going to happen. Instead, regulations will follow deployment, responding to incidents and problems that emerge from real-world operations.

That's not necessarily a disaster—the US automotive industry has a history of learning from incidents and improving safety over time. But it does mean that the first few years of robotaxi and autonomous vehicle expansion will probably involve more incidents and problems than would occur if deployment was slower and more cautious.

There's also uncertainty about what will actually be in the final legislation. Will it include liability standards? Probably. Will it include marketing guardrails? Possibly. Will it include manufacturing requirements? Unlikely. Will it preempt states from regulating on their own? Probably partially, but not completely. Will it fund NHTSA adequately? That depends on Congress's willingness to spend money, which is always uncertain.

The fact that the hearing happened without bringing Congress closer to consensus suggests that major compromises are still needed. Someone will have to give ground—either industry will have to accept stronger safety standards and liability frameworks, or safety advocates will have to accept faster deployment and lighter oversight. Right now, nobody's indicated they're willing to make those compromises.

Looking Forward: What Comes Next

So what actually happens after this hearing? In the immediate term, probably not much. The companies will continue deploying autonomous vehicles. NHTSA will continue investigating incidents. Senators will continue debating what the legislation should include. But Congress probably won't pass comprehensive autonomous vehicle legislation in the near term.

What might move first is something narrower—maybe legislation that explicitly allows remote operation of autonomous vehicles, or legislation that provides liability safe harbors for companies deploying in compliance with safety standards. These smaller pieces of legislation might move faster because they're less controversial than broader regulation.

Alternatively, the issue might stay stuck in legislative limbo until something really bad happens. If there's a major autonomous vehicle accident that kills multiple people or attracts huge media attention, that could shift the political pressure and accelerate legislation. But predicting what will trigger political movement is hard. Something that seems minor now might become a big deal, or something that seems major might get forgotten.

International competition with China will probably continue to push the US toward regulation and manufacturing support. If Chinese companies start exporting autonomous vehicles to other countries and building market share globally, that will make Congress more willing to support American companies. But Chinese companies probably can't export autonomous vehicles to the US for years due to regulatory barriers and tariffs. So the competitive dynamic is more about global market share than direct competition in the US market.

The longer-term dynamic is that autonomous vehicles will probably continue to improve in both capability and safety. Within 5-10 years, autonomous vehicles might be genuinely safer than human drivers in most conditions. At that point, the regulatory debate shifts from "Should we allow this?" to "How do we encourage adoption?" and "How do we transition displaced workers?" Those are different policy questions with different political dynamics.

But for now, we're in a moment of uncertainty. The technology is moving forward. Companies are deploying and learning. Regulators are trying to catch up. Congress is debating what to do. And the public is trying to figure out whether it's safe to ride in a robotaxi or trust its car's autonomous features. The hearing didn't resolve any of those questions, but it did reveal how divided Congress is about what the answers should be.

Conclusion: Regulation at the Speed of Politics

The Senate hearing on robotaxi safety and autonomous vehicle regulation revealed a fundamental mismatch: technology is moving fast, but government moves slow. Waymo and Tesla are deploying autonomous vehicles in American cities right now. They're collecting data, improving systems, and expanding services. But Congress hasn't figured out how to regulate them effectively or what the rules should be.

Waymo argued for federal preemption and light regulation to allow rapid deployment. Tesla argued for innovation-friendly policies and skepticism of regulatory burden. Both companies invoked China as evidence that the US needs to move faster. But senators remained divided on whether faster is actually better, whether safety can be guaranteed at high speeds of deployment, and how to balance competitiveness with public protection.

The most concrete outcome of the hearing was establishing that autonomous vehicle regulation will be harder to pass than initially expected. There's no consensus on what should be regulated, how strongly, or whether federal preemption is the right approach. That means legislation might take years longer than companies hoped. In the meantime, autonomous vehicles will continue to deploy and improve on their own timeline, responding to market forces rather than regulatory requirements.

Safety incidents will continue. Companies will continue to push boundaries. And regulators will continue to play catch-up. That's not a recipe for disaster, but it's not ideal either. Ideally, you'd want regulation to lead technology, setting clear rules that guide development and deployment safely. Instead, technology is leading, and regulation is following behind, trying to address problems as they emerge.

The hearing also highlighted how crucial NHTSA's capacity is to this whole conversation. You can pass legislation, but if the agency charged with enforcing it doesn't have resources, people, and expertise, that legislation is just words on paper. Congress needs to think seriously about whether it's willing to fund adequate regulatory capacity before it passes anything.

For now, the status quo persists. Autonomous vehicles continue to deploy in limited areas. The patchwork of state regulations continues. NHTSA continues its investigation work with limited resources. And Congress continues to debate. Eventually, something will shift—either politics will align around a legislative compromise, or market forces and incident response will create momentum for change. But that shift probably isn't happening immediately.

The robotaxi future is coming. But the regulatory framework to manage that future is still being negotiated, and nobody knows how long that negotiation will take or where it will end up. That uncertainty is probably the most important takeaway from the hearing: we're deploying radical technology into the world without clear rules, and even the people responsible for creating rules aren't sure what those rules should be. That's interesting for a technology company and challenging for anyone concerned about public safety.

FAQ

What is the purpose of autonomous vehicle regulation?

Autonomous vehicle regulation aims to establish safety standards, define liability frameworks, and ensure that self-driving car technology is deployed responsibly. Regulation addresses concerns around safety incidents, consumer protection, insurance liability, and ensuring that companies like Waymo and Tesla operate within defined parameters rather than setting their own rules.

How do Waymo and Tesla differ in their regulatory approaches?

Waymo advocates for federal preemption and clear safety frameworks that it can operate within, emphasizing that the company's safety record and data collection demonstrate responsible deployment. Tesla, meanwhile, argues against regulatory burden and excessive caution, claiming that innovation-friendly policies are necessary for US competitiveness with China. Waymo focuses on explaining how it learns from incidents, while Tesla emphasizes the need for regulatory modernization.

Why is China mentioned so frequently in the autonomous vehicle debate?

China is deploying autonomous vehicles at scale with lighter regulatory requirements, which gives Chinese companies speed-to-market advantages. Senators and industry leaders invoke China as evidence that the US must either move quickly on regulations that enable deployment or risk losing technological dominance. However, Chinese autonomous vehicles currently operate in Chinese markets, not the US, so the competitive threat is more about global market share than direct US market competition.

What are the main safety concerns raised about autonomous vehicles?

Key concerns include Waymo's failures to stop properly behind school buses, the collision of a Waymo robotaxi with a child in Santa Monica, Tesla's removal of radar sensors from vehicles, and the company's marketing practices around autonomous features like Autopilot. Senators also expressed concern about NHTSA's reduced capacity to investigate safety issues due to budget cuts and staffing reductions.

What is binding arbitration and why does it matter for autonomous vehicles?

Binding arbitration requires disputes to be resolved through private arbitration rather than court trials. Tesla requires this for customer disputes, which means if a Tesla causes an accident, victims might not be able to sue in court. This protects companies from liability transparency and makes it harder for patterns of problems to become visible, raising questions about accountability and victim compensation in autonomous vehicle accidents.

How would federal preemption change autonomous vehicle regulation?

Federal preemption would establish one federal standard for autonomous vehicles nationwide, preventing states from imposing additional requirements. Companies favor preemption because it's simpler to operate under one set of rules rather than 50 different state frameworks. However, critics worry that federal preemption with weak standards could prevent states from protecting their residents if federal oversight is inadequate, particularly given NHTSA's current staffing limitations.

What role does NHTSA play in autonomous vehicle regulation?

NHTSA (National Highway Traffic Safety Administration) is responsible for investigating autonomous vehicle incidents, launching recalls when necessary, and overseeing safety compliance. However, the agency lost 25 percent of its staff in recent years, and the Office of Automation was reduced to only four people at one point, severely limiting its capacity to investigate incidents and understand what's happening on the road with deployed autonomous vehicles.

Key Takeaways

- Congress remains deeply divided on autonomous vehicle regulation, with no consensus on federal preemption, safety standards, or liability frameworks

- Waymo faces safety questions around school bus detection and collision incidents, while Tesla faces scrutiny over deceptive marketing of Autopilot features

- China's rapid autonomous vehicle deployment and lighter regulatory requirements create competitive pressure for US federal legislation

- NHTSA's 25% staff reduction and depleted Office of Automation limits the agency's capacity to oversee autonomous vehicle safety

- The liability question remains unresolved, with companies avoiding commitment to clear liability standards or opposing binding arbitration protections for victims

Related Articles

- Waymo's $16B Funding: Inside the Robotaxi Revolution [2025]

- Waymo's $16 Billion Funding Round: The Future of Robotaxis [2025]

- Waymo's $16B Funding Round: The Future of Autonomous Mobility [2025]

- Uber's New CFO Strategy: Why Autonomous Vehicles Matter [2025]

- How Hackers Exploit AI Vision in Self-Driving Cars and Drones [2025]

- Is Tesla Still a Car Company? The EV Giant's Pivot to AI and Robotics [2025]

![Senate Hearing on Robotaxi Safety, Liability, and China Competition [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/senate-hearing-on-robotaxi-safety-liability-and-china-compet/image-1-1770246579229.jpg)