Tech CEOs on ICE Violence, Democracy, and Trump [2025]

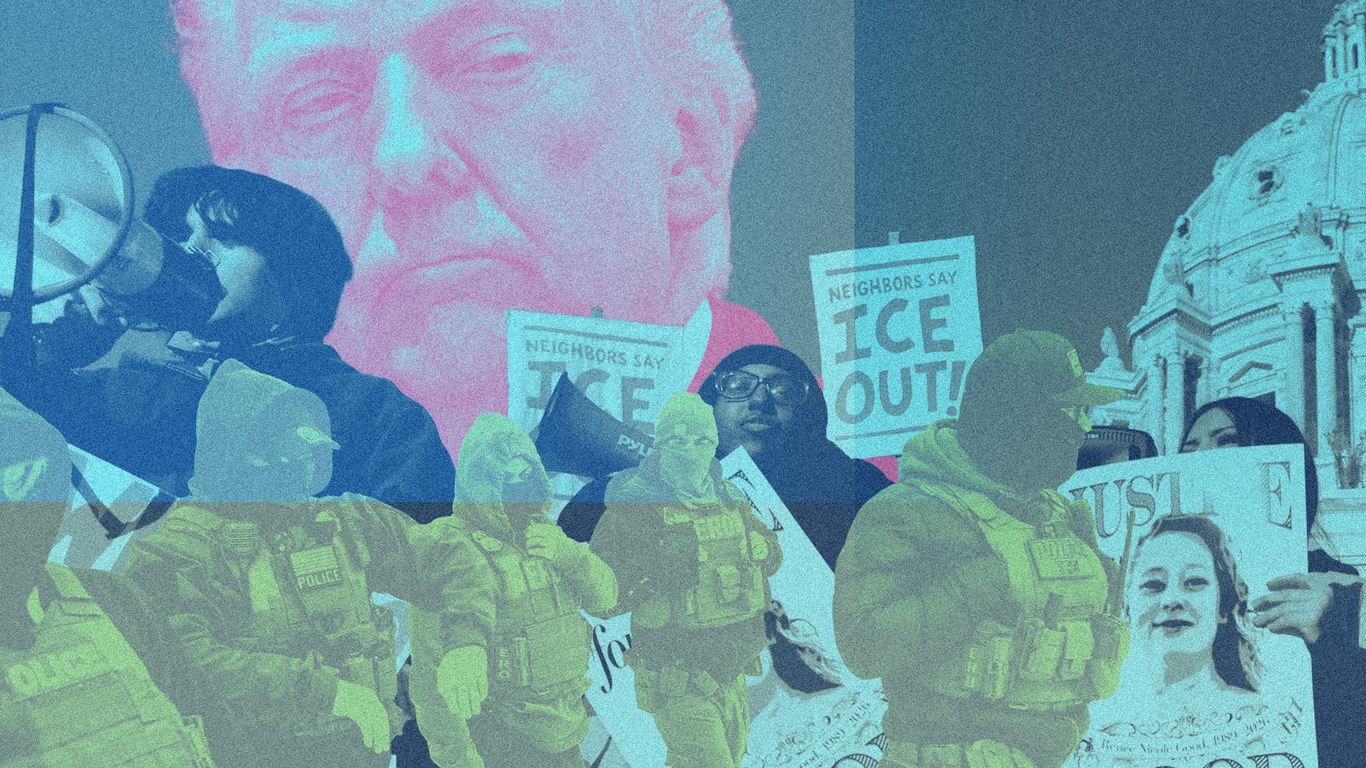

When violence erupts on American streets, tech leaders usually stay quiet. It's safer that way. But in January 2026, something shifted. Anthropic's Dario Amodei spoke publicly. Open AI's Sam Altman sent an internal message that leaked. Apple's Tim Cook penned an email to staff. All three condemned what happened in Minneapolis. All three also praised Trump. That contradiction—the tension between speaking out and staying close to power—defines how tech leadership navigates crisis in 2025 and beyond.

This wasn't a normal news cycle. Minneapolis saw Border Patrol agents kill U.S. citizens. Videos circulated online showing the violence. Tech workers mobilized. They demanded action from their CEOs. They wanted public statements. They wanted contract cancellations. They wanted real pressure on the White House. Some CEOs responded. Others didn't. And the ones who did? They balanced their criticism with compliments to the president whose administration enabled the very violence they condemned.

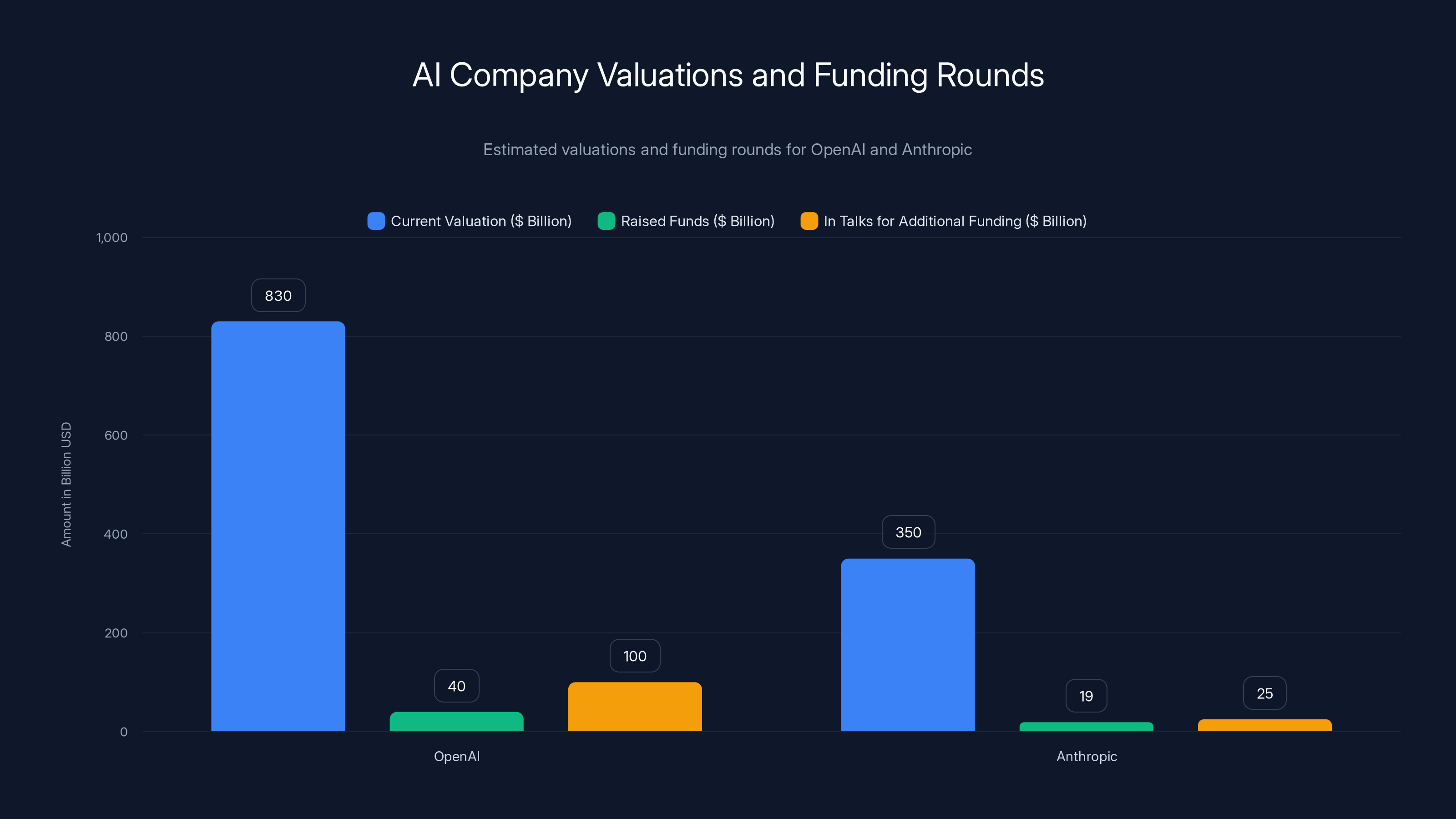

That balance tells you everything about modern corporate politics. Tech leaders understand something voters sometimes forget: the government can help you or hurt you. The Trump administration had positioned itself as AI-friendly. Open AI had just raised billions at astronomical valuations. Anthropic was scaling rapidly. Google, Microsoft, Meta—all benefiting from deregulation and pro-business policies. Speaking truth to power feels good. It also costs money.

So what actually happened? What did these CEOs say, and what does it reveal about corporate responsibility, democratic values, and the price of doing business in America? The real story goes deeper than the headlines. It's about the gap between what leaders say privately and what they're willing to say publicly. It's about how far someone will go to protect their company's interests. And it's about whether speaking against violence while praising the president means anything at all.

Let's break down what happened, why it matters, and what it says about the future of tech leadership.

The Minneapolis Incident and the Tech Worker Uprising

On a Monday night in late January 2026, NBC News aired an unusual segment. Dario Amodei, CEO of Anthropic, appeared on camera. He wasn't there to talk about new AI models or company announcements. He was there because something terrible had happened in Minneapolis, and someone needed to say it out loud.

Border Patrol agents had killed U.S. citizens in Minnesota. The violence was documented on video. Tech workers—the people who build the products that matter to these companies—watched the footage and felt something their bosses didn't immediately feel: they felt compelled to act.

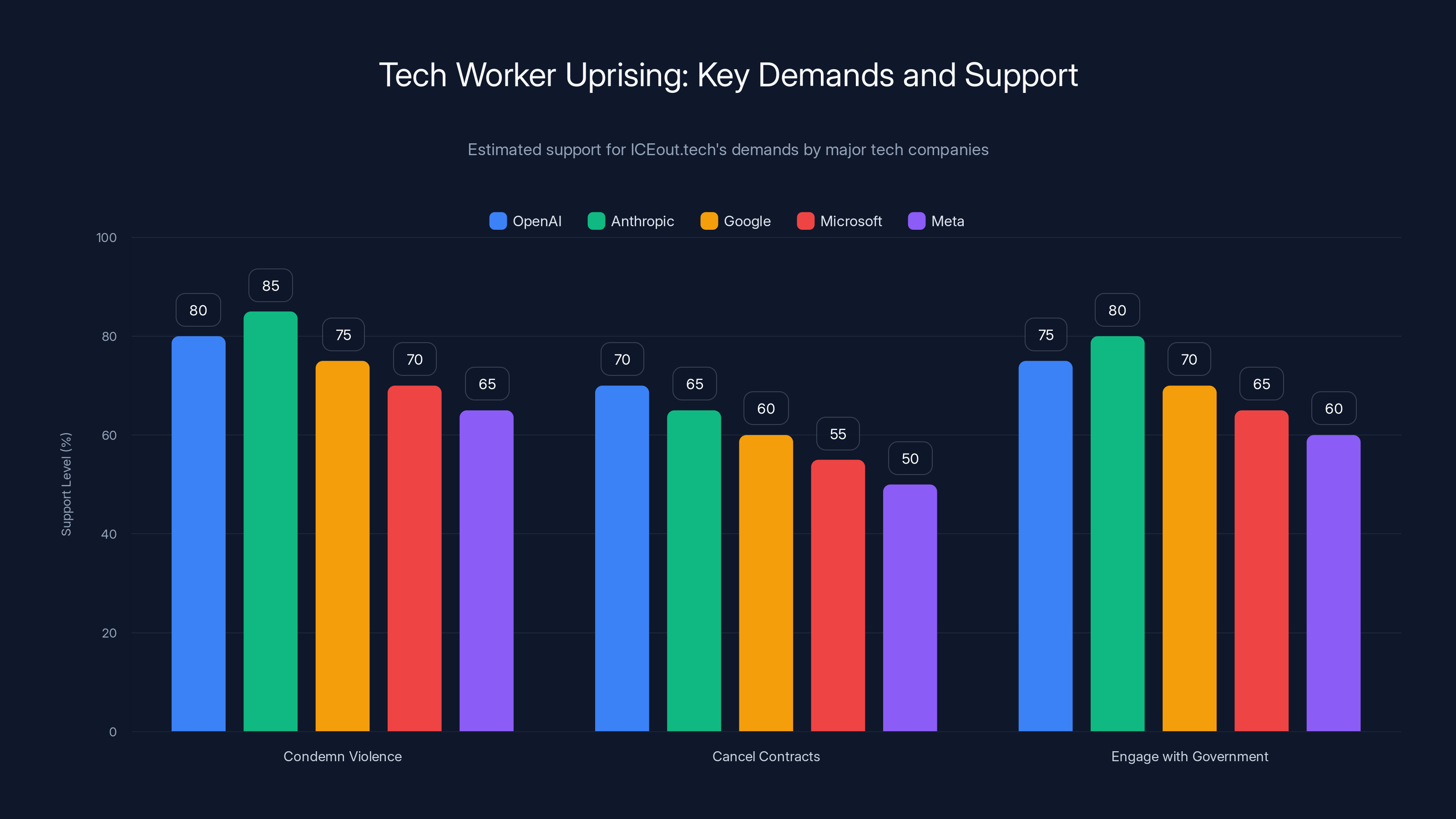

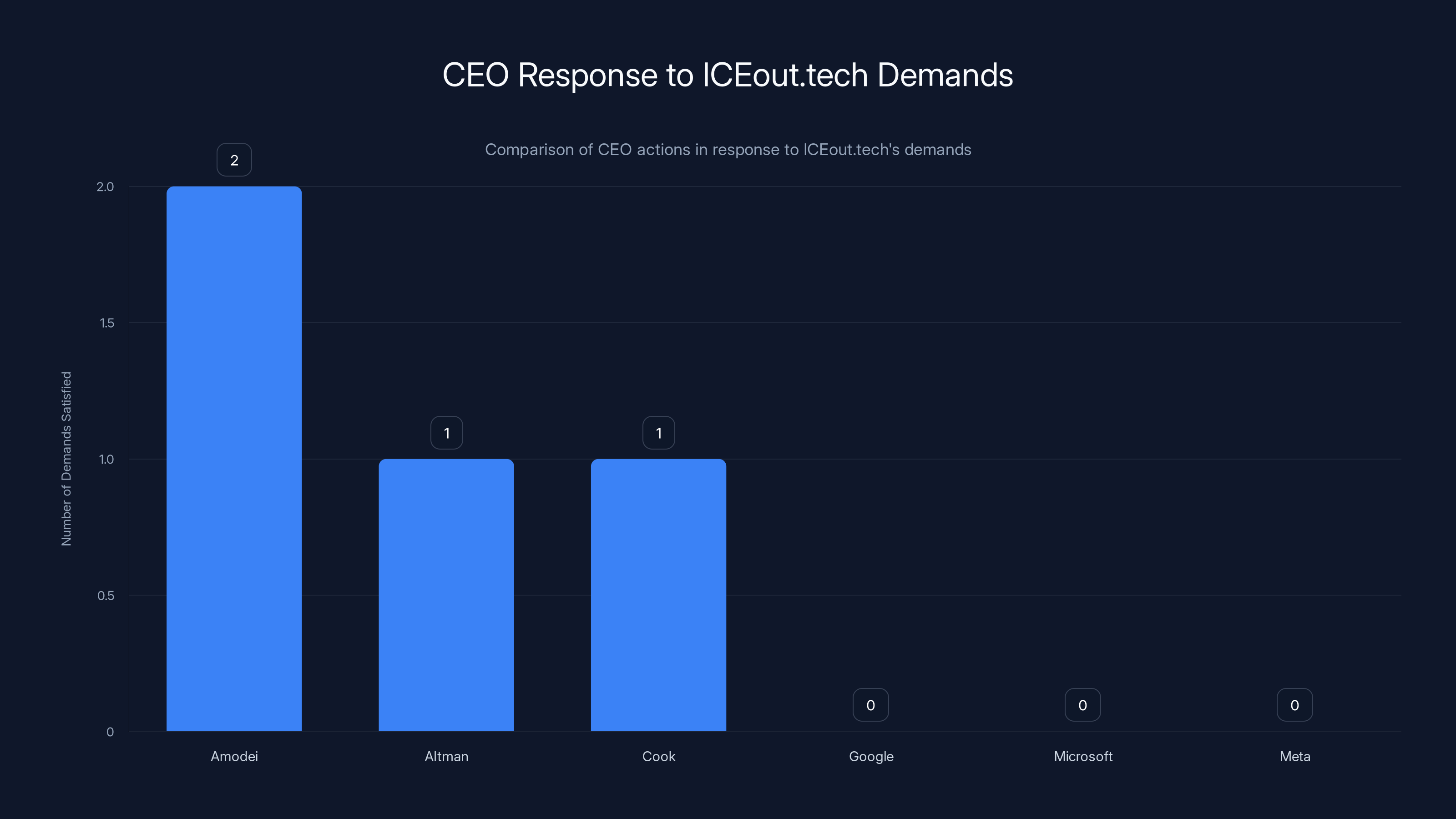

Within days, an organized group calling themselves ICEout.tech had mobilized. They created an open letter. They demanded that tech CEOs do three specific things. First, publicly condemn the violence. Second, cancel all company contracts with Immigration and Customs Enforcement. Third, call the White House and demand change. The letter spread quickly through tech company Slack channels, email lists, and internal networks. Employees at Open AI, Anthropic, Google, Microsoft, and Meta all saw it. Many signed it.

This was significant because tech workers rarely flex this kind of organizational muscle. They usually stay focused on their jobs. But Minneapolis changed that. The images of violence, the knowledge that federal agents were using tactics that felt authoritarian, the realization that their own companies might be helping ICE with technology or contracts—all of it combined to create pressure from inside the organization.

ICEout.tech's letter was specific and measurable. It wasn't vague calls for "corporate responsibility." It was demanding action items. Cancel contracts. Make statements. Engage with government. The group's identities remained anonymous, but their demands were crystal clear. And they had leverage they'd never had before: they had employee energy and moral momentum.

Tech workers understood something their CEOs sometimes forget: public sentiment matters. If your employees think you're complicit in something ugly, that affects everything—recruitment, retention, company culture, media coverage. The open letter weaponized that knowledge.

The pressure wasn't coming from outside activists or media. It was coming from inside. From the people building the products. That made it different. That made it harder to ignore.

Dario Amodei made the strongest public statement condemning ICE violence, while others like Tim Cook and Sam Altman communicated internally. Google, Microsoft, and Meta made no statements.

Dario Amodei Goes Public: The Anthropic Response

Dario Amodei made a choice that many CEOs wouldn't make. He said yes to the NBC interview. He went on camera. And he didn't hide.

On NBC, Amodei focused on something most corporate statements avoid: he tied the Minneapolis violence directly to democracy. He said Anthropic has no contracts with ICE. He said we need to defend democratic values at home, not just abroad. He posted on X, calling out "the horror we're seeing in Minnesota" directly and by name.

That's not the typical CEO response to social pressure. The typical response is to issue a carefully-worded statement through PR, something that acknowledges concerns while protecting the company from liability. Something a lawyer would approve. Something that doesn't antagonize the government.

Amodei didn't do that. He went on television. He used the word "horror." He made it personal and political, not corporate and neutral.

But here's where it gets complicated. Amodei also praised Trump. On NBC, he applauded Trump's "consideration" to allow Minnesota authorities to conduct an independent investigation into the shootings. He framed this as the right thing. He positioned Trump as listening, as being open to the right outcome.

That framing matters. It suggests Trump was reluctant to allow an investigation but Amodei convinced him. It suggests Trump deserves credit for doing the minimum—allowing an investigation into the killing of U.S. citizens. It ties Amodei's statement about democracy to praise for the president whose administration enabled the violence in the first place.

Daniela Amodei, Dario's sister and Anthropic's president, also posted on LinkedIn. She said she was "horrified and sad" by what happened. She said "what we've been witnessing over the past days is not what America stands for." Her post was personal and emotional. It read like someone genuinely disturbed by the violence, not a PR statement.

The Anthropic response was stronger than most. Dario went public. Daniela spoke emotionally. The company stated it had no ICE contracts. But the praise for Trump complicated the message. It's one thing to condemn violence and commend investigation. It's another to praise the president while condemning his administration's actions. That contradiction is the story.

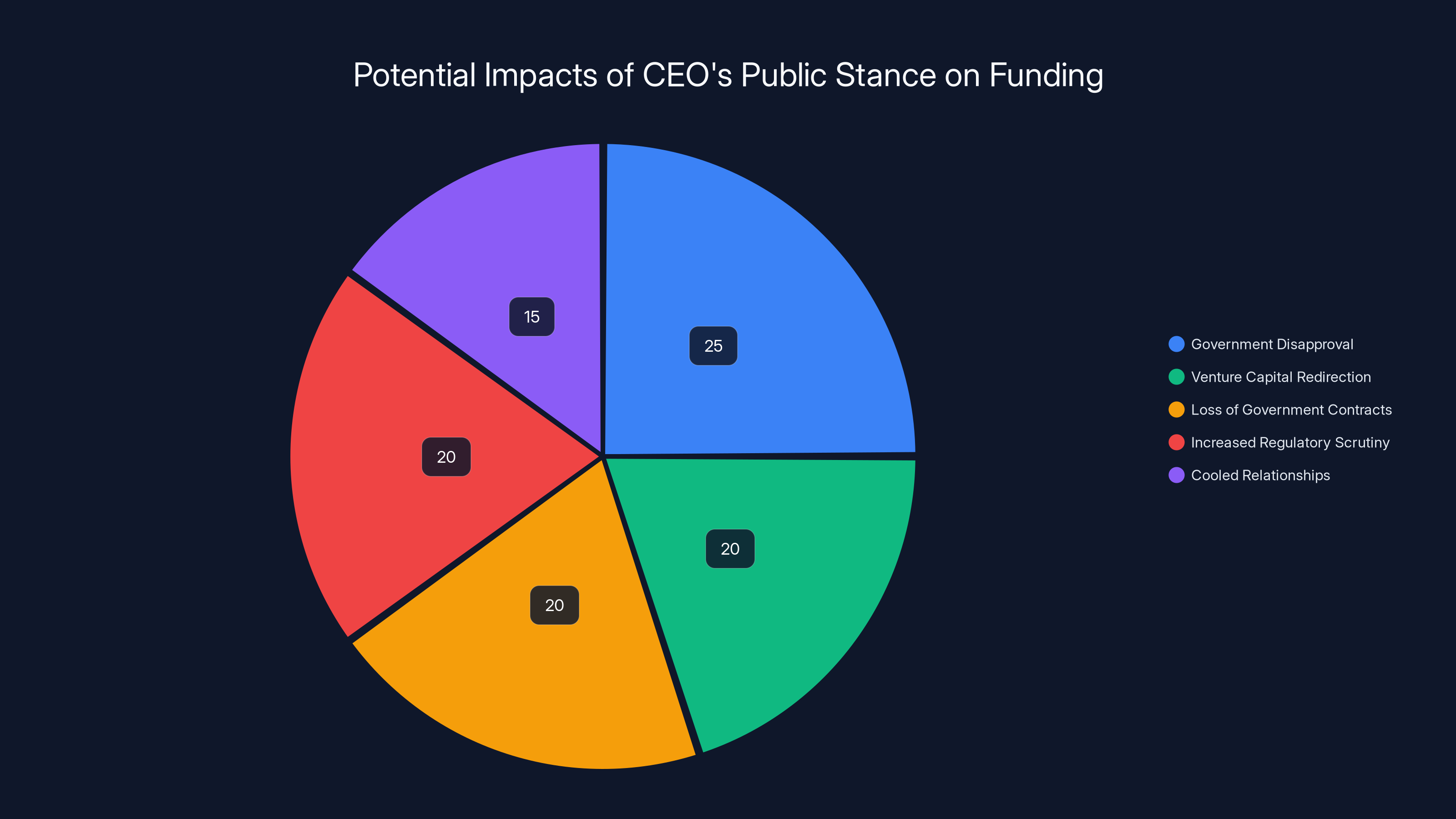

Estimated data shows that government disapproval and venture capital redirection are significant risks if a CEO takes a strong public stance against the administration.

Sam Altman's Leaked Internal Message: The Open AI Contradiction

Sam Altman didn't go on television. Instead, he sent an internal Slack message to Open AI employees. The message leaked to the New York Times. That's how we know what he really said.

"What's happening with ICE is going too far." That's how he started. Direct. Simple. Clear criticism.

He continued: "Part of loving the country is the American duty to push back against overreach. There is a big difference between deporting violent criminals and what's happening now, and we need to get the distinction right."

That's a smart formulation. It accepts the premise that some deportation is legitimate. It even accepts Trump's framing that violent criminals should be deported. But it draws a line. It says there's a difference between the administration's stated goal and what's actually happening. It says the tactics have crossed a line.

Altman also wrote that he was "encouraged by Trump's more recent responses." He said he hopes Trump, "a very strong leader," will "rise to this moment and unite the country." He wrote that Open AI would "try to figure out how to actually do the right thing as best we can, engage with leaders and push for our values, and speak up clearly about it as needed."

Notice what's happening here. Altman is using the language of hope and possibility. He's assuming Trump can be influenced. He's positioning Trump as a "very strong leader" who might be persuaded to do the right thing. He's treating this as a problem of communication, not structure. If Trump just understands the issue better, Altman seems to be saying, he'll change course.

But here's the problem. This message was internal. It only leaked because an employee sent it to a reporter. Altman didn't choose to speak publicly. He chose to speak privately to his employees. That's a different kind of leadership move. It's saying the right things to your team while staying quiet publicly. It's managing internal morale while avoiding external controversy.

J. J. Colao, a PR expert and signatory on the ICEout.tech letter, criticized Altman for this approach. Colao said Altman was trying to "have it both ways." He was condemning ICE violence while calling Trump a "very strong leader," as if the president bears no responsibility for the violence his own administration carried out.

Colao's critique is sharp. You can't separate Trump from ICE violence. ICE operates under the president's executive orders and policy direction. Praising Trump while condemning ICE is like praising a conductor while condemning the orchestra. It doesn't make logical sense.

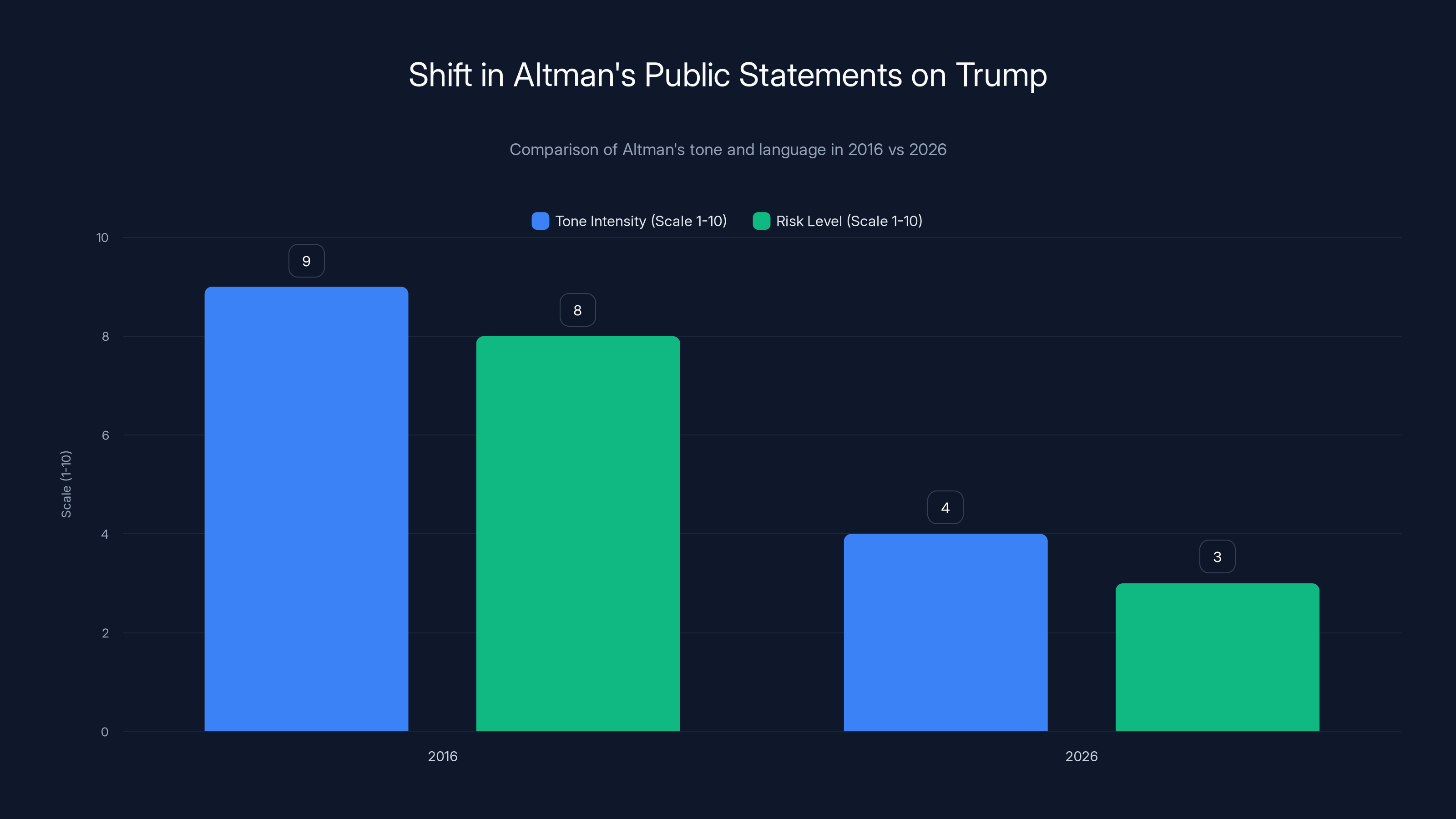

Altman has a history here. In 2016, before Trump's first presidency, Altman wrote a blog post calling Trump a demagogue, a hate-monger, and irresponsible "in the way dictators are." He compared Trump to 1930s Germany. It's chilling writing. Prophetic, maybe. And now, ten years later, Altman is calling the same person a "very strong leader" and hoping he'll rise to the moment.

What changed? Not Trump. The same person is in office. What changed is Open AI. In 2016, Altman was building a nonprofit research lab. In 2026, he's running a for-profit company worth hundreds of billions of dollars. He's dependent on regulatory approval, government cooperation, and business-friendly policies. The Trump administration is delivering on those fronts. That changes what you're willing to say about the person in charge.

Tim Cook's Email and the Optics Problem

Tim Cook took a middle approach. He sent an email to Apple employees. Like Altman's message, this leaked—first to Bloomberg. In the email, Cook said he was "heartbroken by the events in Minneapolis."

He also said he'd had a "good conversation" with President Trump and appreciates "his openness to engaging on issues that matter to us all."

Here's the complication: while Cook was writing this message expressing heartbreak over ICE violence, he was also attending an exclusive screening of a documentary about Melania Trump, the First Lady. Apple employees noticed. They were reportedly angry about the optics.

It's a perfect microcosm of the broader contradiction. You're expressing concern about violence. You're praising the president. You're attending social events with the president's family. All at the same time. All while your company ostensibly opposes the violence and the policies enabling it.

Apple, unlike Anthropic, never made a public statement. The email leaked. That was the only way it became public. Apple didn't volunteer the information. Apple didn't speak to the press. Apple didn't position itself as condemning the violence. The company only responded when forced to by a leak.

Cook's email is softer than Amodei's statement and softer than Altman's internal message. It uses emotional language ("heartbroken") but takes no concrete action. It doesn't mention contracts. It doesn't demand investigations. It just says Cook feels bad and appreciates Trump's openness.

That's the safest possible position. You're on record as opposing the violence. You're also not antagonizing the president. You've covered yourself with your employees and the media. But you've also committed to nothing. No company action. No public pressure. No risk.

OpenAI and Anthropic are leading AI companies with significant valuations and funding rounds, influenced by the current administration's policies. Estimated data based on available information.

The Silence of Google, Microsoft, and Meta

While Amodei, Altman, and Cook were issuing statements, three other major tech companies stayed completely silent. Google, Microsoft, and Meta made no statement at all, public or private. At least, not that became public.

ICEout.tech specifically called out these companies. The organizers said they were "glad to hear" from Open AI and Anthropic but frustrated that Google, Microsoft, and Meta had "remained silent despite calls all across the industry."

This silence is its own kind of statement. It says: we're not engaging with this issue. We're not taking a position. We're not responding to employee pressure. We're going to stay quiet and hope the conversation moves on to the next news cycle.

That strategy sometimes works. Sometimes silence is safer than speech. If you don't say anything, you can't be criticized for what you said. You can't be accused of hypocrisy. You can't be challenged on whether you're living up to your own stated values.

But silence also has costs. It alienates employees who expect leadership during crisis. It opens the company to accusations of complicity. It suggests the company cares more about protecting profits than defending democracy. And it fails the test that ICEout.tech was applying: what are you actually doing about this?

The contrast is revealing. Anthropic and Open AI, the AI-focused companies most dependent on government cooperation, were the most vocal. Apple, already struggling with its image on human rights, took the middle ground. Google, Microsoft, and Meta—massive companies with massive regulatory complexity—said nothing.

Size and regulatory exposure matter. The bigger your company and the more regulated your industry, the more you have to lose by taking a public stand against the government. That's the practical calculus that drives corporate behavior.

The Contract Question: Do Tech Companies Actually Work with ICE?

Amodei made a specific claim: Anthropic has no contracts with ICE. That's an important data point because it means Anthropic can speak out without being hypocritical. They're not profiting from the very system they're criticizing.

But what about the other companies? Open AI didn't claim to have no ICE contracts. Apple didn't claim to have no ICE contracts. Google, Microsoft, and Meta didn't address the question at all.

The contract question matters because it reveals the real tension. If your company is providing technology to ICE, then condemning ICE violence while profiting from ICE technology is a contradiction. It's not enough to say you oppose the violence. You have to actually stop enabling it.

The tech industry has this pattern. Companies contract with government agencies. Employees object. Companies issue statements about values. Employees ask: then why are you still taking the contract? Companies say: we're working on it. Or: the technology is neutral. Or: we need to be at the table influencing policy.

ICEout.tech understood this. Their demands included: cancel contracts. That's the real test. It's not whether you condemned the violence in a statement. It's whether you stopped profiting from the system that enabled the violence.

We don't know if any of these companies actually have ICE contracts. The information isn't public. Companies aren't required to disclose government contracts. And when they do disclose contracts, the details are often redacted for "security reasons."

That opacity is part of the problem. Tech workers at these companies might know whether their company works with ICE. The public probably doesn't. And the companies have strong incentives to keep it that way.

Estimated data shows varying levels of support for ICEout.tech's demands among major tech companies, with the highest support for condemning violence. Estimated data.

The Valuation Question: Why Trump Matters to Tech Leaders

Here's the financial reality that explains everything. Open AI had just raised at least

These aren't normal numbers. They're escaping gravity. They're based on assumptions about AI's future, deregulation, and favorable government treatment. They're based on a belief that this administration will enable rapid scaling and expansion.

The Trump administration is AI-friendly. It's deregulation-friendly. It's friendly to large corporations with government contracts. If you're a tech CEO trying to reach a $1 trillion valuation, the current administration is helping you get there.

Now, what happens if you aggressively attack that administration? What happens if you go on television and call out the president's policies as authoritarian? What happens if you position yourself as an opponent of the administration's values?

You risk losing access. You risk losing regulatory favor. You risk antagonizing a government that can speed up your funding rounds or slow them down with scrutiny. You risk making deals harder and taking longer. You risk the whole valuation architecture collapsing.

That's not a conspiracy theory. That's how power works. Tech leaders understand this intuitively. It's why they walk the line. They condemn the specific violence while praising the leader responsible for the policy enabling that violence. They express concern while avoiding confrontation. They signal opposition while protecting access.

The math is simple. For a

The workers understand this too. That's why they mobilized. They know their CEOs have economic incentives to stay quiet. That's why they created external pressure. That's why they organized. Because the internal incentives point the wrong direction.

What Amodei Actually Said About Democracy

Go back to what Amodei emphasized. He said we need to "defend our own democratic values at home." He focused on preservation of democracy, not just policy disagreement.

That's a different framing than Altman's. Altman talked about the difference between deporting criminals and what's happening now. He made a policy argument. Amodei talked about democracy itself. He made a structural argument.

Democracy, in Amodei's formulation, means the government doesn't kill citizens without due process. It means independent investigation when that happens. It means there are checks on power. It means citizens can push back against overreach.

That's a stronger argument than Altman's pragmatic middle ground. But it's also partially contradicted by Amodei's praise for Trump, whose policies arguably threaten the democratic norms Amodei claims to care about.

Still, Amodei went further than most. He made a case that's tethered to principle rather than just policy preference. He said this isn't just about immigration tactics. It's about whether America remains a functioning democracy where the government can be held accountable.

That case matters. It's the kind of case that, if you truly believed it, would make you do more than issue a statement. It would make you take action. It would make you willing to risk the valuation, the funding round, the access.

But Amodei didn't go that far. None of them did.

Altman's public statements on Trump show a significant shift from a high-intensity, high-risk tone in 2016 to a more subdued and pragmatic tone in 2026. Estimated data.

The History: Altman's 2016 Blog Post

Samuel H. Altman, in 2016, wrote something remarkable. He titled it "Trump" and posted it on his personal blog. Here's what he said.

"[Trump] is not merely irresponsible. He is irresponsible in the way dictators are. To anyone familiar with the history of Germany in the 1930s, it's chilling to watch Trump in action."

He called Trump a "demagogic hate-monger." He said Trump dangles the lie of safety from outsiders as a distraction from lack of actual policy. He said Trump has "no serious plan for how to restore economic growth."

It's brutal writing. It's the kind of writing that comes from genuine conviction, not strategic calculation. Altman took risk by writing it. He said as much. He could have been attacked. He probably was attacked, actually. But he put his name on it.

That was Altman in 2016, when Open AI was a nonprofit and he had less to lose.

Now compare that to his 2026 internal message. Trump is a "very strong leader" who might rise to the moment. Open AI will "try to figure out how to actually do the right thing" and "engage with leaders and push for our values."

The language has softened completely. The tone has shifted from moral clarity to pragmatic hope. The analysis has changed from structural critique (this person is authoritarian) to tactical assessment (this leader might respond to pressure).

Why? Because in 2016, Altman didn't have $830 billion in valuation on the line. In 2026, he does. Because in 2016, Open AI was a nonprofit. In 2026, it's a for-profit company dependent on investor returns. Because in 2016, the AI industry wasn't getting massive government support and deregulation. In 2026, it is.

Altman didn't change his principles. He just changed the calculation of what he could afford to say. That's a very human response to power and money. It's also a depressing one if you were hoping tech leaders would be different.

The Employee Pressure Campaign: ICEout.tech

ICEout.tech's strategy was simple and effective. They made specific demands. They organized around those demands. They made it clear to CEOs what they needed to do to satisfy their employees.

The demands were:

- Publicly condemn ICE violence.

- Cancel all company contracts with ICE.

- Call the White House and demand policy change.

That's a graduated scale of pressure. The first is cheap (just talk). The second costs money (lose a contract). The third risks access (antagonize the administration).

Different CEOs satisfied different levels of the demands. Amodei satisfied levels one and two (public statement, claimed no ICE contracts). Altman satisfied level one, sort of, but only in a leaked internal message, not publicly. Cook satisfied level one, sort of, but only through a leaked email. Google, Microsoft, and Meta satisfied none of the demands.

ICEout.tech understood that employees were the leverage point. Tech workers have market power. It's hard to hire and retain talented engineers if your company is seen as complicit in violence. So ICEout.tech mobilized that power.

Their organizing was sophisticated. They stayed anonymous (which protects individual employees). They used official company channels (Slack, email) to spread the letter. They created a separate website (ICEout.tech) that wasn't tied to any single company. They stayed focused on specific, measurable demands.

That's how you organize inside a company. You can't overthrow a corporation from inside. But you can make leadership uncomfortable. You can make the reputation cost of inaction exceed the reputation cost of action. You can shift the calculation.

It worked partially. Some CEOs felt the pressure and responded. Others ignored it and faced the consequences of silence. And all of them had to engage with the reality that their employees cared about this and were willing to organize around it.

That's significant. For most of the history of tech, employees have been politically quiet. They've stayed focused on work. They haven't organized. ICEout.tech shows that changing. It shows employees willing to mobilize around values, not just compensation and benefits.

Amodei satisfied the most demands, while Google, Microsoft, and Meta did not satisfy any. Estimated data based on narrative.

The Valuation Risk Calculation

Let's do the math on what's at stake. Open AI is raising

If a CEO takes a very strong public stand against the administration, what happens to that funding round?

It's not certain, but it's plausible that:

- Government officials might signal disapproval to major investors

- Venture capitalists focused on government contracts might invest elsewhere

- Access to government contracts for the company might disappear

- Regulatory scrutiny might increase

- Relationships with government officials that facilitate funding might cool

None of these effects are guaranteed. But they're possible. And if you're trying to close a $100 billion round, you don't want them possible.

Now, what's the cost of staying silent or offering mild criticism while praising the president?

- Some employees might be unhappy (but you issue an internal message to manage morale)

- Some people might criticize you on Twitter (but Twitter noise is temporary)

- Your reputation might suffer with some constituencies (but those constituencies probably aren't your investors)

- You might face some media scrutiny (but the news cycle moves fast)

The cost is real but manageable. It's not zero. But it's way less than the cost of actually antagonizing the administration.

So the calculation makes sense from a business perspective. From a moral perspective, it's harder to defend. But business is what we're talking about here. Business is what drives decision-making.

Maybe that's fine. Maybe we shouldn't expect CEOs to be martyrs. Maybe it's reasonable to protect your company and its investors while still speaking out against violence. Maybe the approach these leaders took—condemn the violence, praise the leader—is the reasonable middle ground.

Or maybe it's a cop-out. Maybe standing up for something means actually standing up, not hedging your statement with compliments to the person responsible for the problem.

That's the debate these statements create.

What Does Corporate Responsibility Actually Mean?

ICEout.tech's demands were built on an assumption: that tech companies have responsibility not just to shareholders and employees, but to the broader public. That assumption is increasingly contested.

One view is that corporations are accountable primarily to shareholders. You make money for shareholders within legal bounds. You don't break laws. Beyond that, you're not responsible. You're not a government, you're a business.

Another view is that corporations, especially large ones with significant influence, have broader responsibility. They have the power to shape policy, culture, and outcomes. With that power comes responsibility for how power is used. If your company's technology is used for surveillance or enforcement, you have responsibility for that usage.

Tech leaders often try to split the difference. They say their technology is neutral and can be used for good or bad purposes. They say they have responsibility for how their employees are treated and what they're asked to do. They say they participate in policy debates and try to influence policy toward what they see as right. But they say they can't control what governments do.

That's a reasonable position. It's also a self-interested one. It gives you all the upside (profit, influence, scaling) without the downside (responsibility for outcomes).

What ICEout.tech was demanding is: take responsibility for your role in the system. If you benefit from government contracts, you have responsibility for what that government does. If your technology enables government action, you have responsibility for that action. If you have influence you can use to change policy, you have responsibility to use it.

That's a higher bar. It's also maybe the bar we should have.

The Contradiction Between Values and Business

This whole situation reveals something important: there's a deep contradiction between the values tech companies claim to hold and the business incentives they actually follow.

Open AI's mission statement includes language about ensuring AI is beneficial to humanity. Anthropic's founding was built around the principle of AI safety. Apple's brand is built on privacy. Google's original motto was "don't be evil." Meta, the Facebook company, has positioned itself as connecting people.

All of these missions could be interpreted to require taking a strong stand against government violence, authoritarian action, and human rights violations. All of them could be interpreted to require refusing to profit from systems that enable that violence.

But none of them do, actually. Because following that interpretation all the way would cost money. It would limit growth. It would require turning down contracts and relationships that are profitable.

So what happens instead? The companies develop language that lets them claim to hold their values while not actually following them through. They say they "engage with policy." They say they're "working on" various issues. They say they have "no comment" on specific situations.

It's not hypocrisy exactly. It's more like values inflation. You claim to value democracy or human rights or privacy, but you define those values in ways that don't actually conflict with making money.

That works until something specific happens—like ICE violence in Minnesota—that makes the contradiction too obvious to ignore. Then you have to make a choice. You can follow your values (which costs money). You can follow your business incentives (which compromises your values). Or you can try to do both (which usually means your statement will be contradictory).

Most CEOs choose option three. They condemn the violence while praising the leader. It's the option that lets you eat your cake and have it too.

The Media's Role in Framing the Story

Notice what happened with the media coverage of these statements. When Amodei spoke publicly on NBC, it was covered as him taking a stand. When Altman's internal message leaked, it was covered as him being forced to respond. When Cook's email leaked, it was covered as him being pressured.

But the framing depends on what gets published. If Altman and Cook had successfully kept their statements internal, there would have been no coverage. No one would know what they said. There would just be silence from those companies, which would look like they don't care.

The leaks forced them to be on record. And once they're on record saying these things internally, the question becomes: why not say it publicly?

Amodei chose to say it publicly. That's a different kind of leadership. It's saying: I'm willing to stand by this statement with my name on it in public. I'm not hiding behind an internal message that might leak.

That doesn't mean Amodei's statement is perfectly consistent or morally complete. It's still complicated by praise for Trump. But it is more exposed, more vulnerable to criticism, more honest in a way.

The media covered this in a fairly straightforward way. Here's what these leaders said, here's what they mean, here's what's interesting about the contradictions. The media didn't, as far as I know, break news by independently investigating whether these companies actually have ICE contracts. The media didn't go back through history and analyze whether these companies had previously taken different positions.

The media mostly just reported what the leaders said and let readers draw conclusions.

What Happens Next?

So what actually changes because of these statements? Does Anthropic really cancel ICE contracts (it claimed to have none)? Does Open AI actually follow through on "engaging with leaders" to push for change? Does Apple actually use its access to Trump to pressure him on immigration?

History suggests: probably not much. Statements like these usually mark the end of corporate response, not the beginning. You make a statement. You take the pressure off. You move on. The original problem remains unchanged.

The Minneapolis violence was real. The government action that enabled it was real. The policy that created ICE and deployed it in cities was real. All of that continues regardless of what CEOs say in NBC interviews or leaked internal messages.

Maybe the hope is that if Trump actually feels pressure from tech leaders, he might moderate the ICE approach. Amodei's statement seemed to suggest that hope. But Trump ran on aggressive immigration enforcement. That's his policy. It's what got him elected (or re-elected, in this case). It's not something he's going to abandon because the CEO of Anthropic asked nicely.

Maybe the point is to build employee morale, signal that the company's leadership cares, and try to retain talent. That's a legitimate goal. Employees who feel their company is just a profit machine and doesn't care about their values will leave. So managing morale matters.

Maybe the point is to signal to the general public that the tech company is a good actor, that it cares about the right things, that it's different from other corporations. That signal matters for brand, for customer relations, for government relations.

All of those are real functions of a CEO statement on a controversial issue. None of them are the same as actually solving the problem.

What would actually solving the problem look like? It would probably require:

- Refusing government contracts that violate human rights

- Using platform/technology to resist government violence

- Funding legal defense for people targeted by government action

- Recruiting and supporting political pressure on the administration

- Building alliances with other companies and civil rights organizations

None of these companies are doing that. Amodei got closest with the public statement and claimed contract cancellation. But even Amodei isn't going to war with the administration. He's just signaling disapproval while keeping the door open.

That's probably realistic. That's probably the most you can expect from corporate leaders managing companies worth hundreds of billions of dollars. But it's also why saying "we're working on it" and "we're engaging with policy" sometimes feels hollow. Because working on something and engaging in policy often means not actually solving the problem.

The Broader Context: Tech and Power in 2025

This situation doesn't exist in a vacuum. It's part of a larger story about tech companies and their relationship to government power.

For the first two decades of tech's existence, tech companies were insurgent. They were fighting against established power. Microsoft fought IBM. Google fought Yahoo and early search engines. Facebook fought My Space. Apple fought the established computer industry.

Even when they became powerful, they often positioned themselves as outsiders. As rebels. As different from traditional corporations. As driven by founders with missions, not just by shareholders seeking profit.

Some of that was real. Some of it was marketing. But it shaped the culture. It shaped how founders and employees thought about what they were building.

Now we're in a different era. Tech companies are the established power. They have more influence over information than newspapers. They have more data than governments. They have more capital than most countries. They're not insurgents anymore. They're the establishment.

And like most establishment powers, they want to protect what they have. They want favorable government treatment. They want light regulation. They want access to power.

That changes everything. When you're insurgent, you can afford to challenge power. When you're established, you want stability. You want predictability. You want the people in power to like you.

The Trump administration is friendly to tech, especially on deregulation and AI policy. That's worth hundreds of billions of dollars in future value. It's worth maintaining that relationship. It's worth being careful about how hard you push back on the administration's actions.

So we get these statements. Condemnation of violence paired with praise for the leader responsible for the policy enabling that violence. It's the statement that lets you claim to care while protecting your interests.

That's probably the new normal for tech CEOs. Unless the business calculation changes—unless there's so much employee pressure or reputational cost that speaking out clearly becomes profitable—we'll keep seeing this pattern.

The Role of Employee Activism

One of the more interesting aspects of this situation is how much pressure came from employees rather than external activists. Normally, pressure on corporations comes from outside: consumer boycotts, shareholder activism, media criticism, NGOs.

But ICEout.tech's power came from inside. From employees organizing. From people who could choose to quit if the company wasn't aligned with their values. From people whose daily labor makes the company function.

That inside pressure is harder to dismiss than outside pressure. A consumer boycott is easy to ignore if the market doesn't respond. An NGO criticism is easy to ignore if media doesn't amplify it. But employee activism? That affects hiring, retention, productivity, and culture. That's harder to ignore.

We're seeing more of this. We saw it during the Dragonfly (Google in China) debates. We saw it during the Google AI and weapons controversy. We saw it during various labor organizing efforts. Employees are increasingly willing to organize around values and not just compensation.

That might be the most important shift in this whole situation. Not what the CEOs said, but that employees felt empowered to demand that the CEOs say something.

If that pattern continues—if employee activism becomes a normal and effective pressure tool—then CEOs will face constant tension between business incentives and employee values. That might actually force them to take stronger stands on controversial issues.

Or it might just result in more sophisticated corporate communications that sound like they're taking a stand while actually protecting business interests. We'll see.

Lessons for Future Corporate Leadership

If you're a CEO reading this situation, what does it teach you?

First: you can't ignore employee pressure on values issues. Silence looks like complicity. Your employees will organize, and their organizing will become public. Better to engage with the issue than to hope it goes away.

Second: if you do engage, be consistent. Don't praise the leader while condemning the leader's policies. It looks like you're trying to have it both ways, which you are, which makes it look cynical.

Third: be aware that your historical statements will be used to judge your current statements. If you wrote a blog post in 2016 calling someone a dictator, don't call that same person a "strong leader" in 2026. People notice. It looks like your principles changed because your business situation changed.

Fourth: understand what your company actually does and what it might be complicit in. If you don't know whether you have ICE contracts, find out. If you do have them and you're condemning ICE violence, that's a contradiction you need to address.

Fifth: separate your statements for different audiences. Your employees need one thing (assurance that you care about values). Your investors need another (assurance that you're managing risk). Your government relationships need another (assurance that you're not hostile). Don't try to do all three in one statement.

Sixth: if you can't take a real stand because the business risk is too high, admit that. Say: "We care about this issue, but we're not willing to take action that might hurt our business." At least that's honest. It's better than saying you care and then doing nothing.

Seventh: understand that every CEO's historical positions matter. You're building a reputation across decades. If you want to be seen as someone with principles, you have to maintain consistency. If you flip positions when the business calculation changes, people will know. They'll remember your 2016 blog post. They'll reference it in 2026 when you say something different.

The Future of Corporate Responsibility

Where does this go from here? What does corporate responsibility look like in the coming years?

One scenario: Tech companies become more like traditional corporations. They care about government relations. They care about being seen as good corporate citizens. But they're fundamentally profit-maximizing entities. They take calculated positions on social issues that serve their interests. They manage political relationships carefully. They speak out on issues where speaking out is profitable and stay quiet on issues where it costs money.

That's probably the most likely scenario. It's the direction we're already moving.

Another scenario: Employee activism forces companies to take stronger positions. If enough talented people care about values and are willing to organize around them, companies have to choose between losing that talent and actually following through on their stated values. That could create real change.

That's less likely because it requires sustained pressure over time, and because companies get better at managing employee activism (better internal communications, better incorporation of employee demands without real change, better messaging).

A third scenario: The definition of corporate responsibility expands beyond statements to actual accountability. Companies can't just say they care about democracy or human rights; they have to prove it through actions and outcomes. That would require legal or regulatory change, which is hard to achieve.

Most likely is scenario one with elements of two. You'll get some companies taking stronger positions because of employee pressure. You'll get most companies doing the minimum necessary to manage employee relations while protecting business interests. And you'll get ongoing tension between what companies claim to value and what they're actually willing to do.

That tension is probably healthy. It keeps the question alive. It keeps companies from becoming completely amoral. It keeps employees and citizens able to point to the gap between stated values and actual behavior.

But it also means don't expect corporate CEOs to be the vanguard of social change. Expect them to move carefully, to hedge their bets, to try to maintain relationships with power while signaling opposition to bad things. That's what we saw with Amodei, Altman, and Cook. That's probably what we'll keep seeing.

FAQ

What prompted the CEO statements about ICE violence in Minneapolis?

Border Patrol agents killed U.S. citizens in Minneapolis, and the violence was documented on video. Tech workers, organized as ICEout.tech, circulated an open letter demanding that their CEOs take three specific actions: publicly condemn the violence, cancel all company contracts with ICE, and call the White House to demand policy changes. The employee organizing pressure forced some CEOs to respond, though primarily through public statements (Amodei) or leaked internal messages (Altman and Cook).

How did the CEOs' statements differ from each other?

Dario Amodei of Anthropic made the strongest public statement on NBC News, specifically condemning the "horror" in Minnesota while emphasizing the importance of defending democratic values at home. He also stated that Anthropic has no ICE contracts. Sam Altman of Open AI sent an internal Slack message stating "What's happening with ICE is going too far," but only internal employees saw it until it leaked to the New York Times. Tim Cook of Apple sent an internal email expressing that he was "heartbroken," but made no public statement and was criticized for attending a Melania Trump documentary screening hours after the violence. Google, Microsoft, and Meta made no statement at all.

Why did the CEOs praise Trump while condemning ICE violence if Trump's administration is responsible for ICE policy?

The CEOs' statements appear to reflect a business calculation. Open AI was raising

Did Sam Altman's 2016 statements about Trump contradict his 2026 message?

Yes, significantly. In 2016, Altman wrote that Trump was "irresponsible in the way dictators are" and compared watching him to 1930s Germany. He called Trump a "demagogic hate-monger." In 2026, Altman described Trump as a "very strong leader" and expressed hope that he would "rise to this moment." The shift reflects how Altman's personal circumstances changed: in 2016, Open AI was a nonprofit with less to lose; in 2026, it was a for-profit company with hundreds of billions in valuation riding on favorable government treatment.

What does ICEout.tech demand from tech companies on government contracts?

ICEout.tech's demands were specific and graduated: first, public condemnation of ICE violence; second, cancellation of all company contracts with ICE; and third, direct calls to the White House demanding policy changes. The group understood that the first demand was relatively cost-free (just words), while the second required losing revenue, and the third required antagonizing the administration. By making these demands explicit, ICEout.tech forced CEOs to choose which level of commitment they were actually willing to make.

Why did Google, Microsoft, and Meta remain completely silent on this issue?

These companies faced greater regulatory complexity and had more extensive government contracts than Anthropic or Open AI. The larger and more regulated your company, and the more dependent you are on government relationships, the more you have to lose by taking a public stand against the administration. Silence allows these companies to avoid antagonizing the government while also avoiding accusations of explicit complicity. However, this approach has costs too: it alienates employees who want leadership during crises and opens the companies to accusations of caring only about profit.

What role did employee activism play in forcing CEO responses?

Employee activism was the primary driver of CEO responses. Unlike external criticism from NGOs or media outlets, which companies can often ignore, internal employee pressure affects hiring, retention, productivity, and culture. ICEout.tech understood that tech workers have market power and used internal company channels (Slack, email) to spread the open letter. The combination of organized pressure, leaked internal emails, and employee organizing made it impossible for CEOs to ignore the issue completely, though they could control the nature and visibility of their response.

How do CEO statements on controversial issues affect company valuations and funding?

There's no direct evidence that speaking out against government violence damages valuations, but CEOs perceive a risk that strong criticism of the administration could affect funding rounds, regulatory relationships, or government contract opportunities. This perceived risk is what drives the balancing act: condemn the specific violence while praising the leader. The $100+ billion funding rounds that Open AI and Anthropic are pursuing make CEOs particularly cautious about antagonizing the administration, even when they disagree with specific policies.

What does this situation reveal about the contradiction between stated corporate values and actual business behavior?

Tech companies claim to value democracy, human rights, and privacy, but these values often conflict with business incentives for growth, government relationships, and investor returns. When faced with a crisis like ICE violence, companies try to satisfy both through statements that condemn violence while praising leadership. This approach allows them to claim alignment with employee values while protecting business interests. The gap between stated values and actual actions suggests that corporate responsibility statements should be evaluated based on concrete actions (cancelled contracts, policy changes) rather than verbal commitments.

What accountability exists if tech companies have government contracts they don't publicly disclose?

Very little accountability currently exists. Tech companies are not required to publicly disclose government contracts, and when they do, details are often redacted for "security reasons." This opacity means employees and the public often don't know whether their company is working with agencies like ICE. Some companies, like Anthropic in this case, claim to have no ICE contracts, but this information cannot be independently verified without corporate transparency. This lack of disclosure undermines accountability and allows companies to benefit from government relationships while avoiding public scrutiny of what those relationships entail.

How might employee activism change corporate behavior on values issues in the future?

If employee activism continues to be effective—as it was with ICEout.tech and previous campaigns like Dragonfly—it could force companies to take stronger stands on values issues. Unlike consumer boycotts or shareholder activism, which can be managed or ignored, employee activism directly affects daily operations. Companies might eventually face a choice between taking real action on values (cancelling problematic contracts, refusing government relationships) or losing talented people to competitors who will. However, companies also get better at managing activism through better communication and strategic concessions that address employee concerns without fundamental change. The outcome will likely vary by company and will depend on how sustained the activist pressure remains.

Key Takeaways

- Employee activism through ICEout.tech forced tech CEOs to respond to ICE violence, but with different levels of commitment: Amodei went public, Altman and Cook only internal, Google/Microsoft/Meta silent

- CEOs balanced criticism of ICE violence with praise for Trump despite his administration's responsibility for ICE policy, revealing business calculations around massive funding rounds and government relationships

- Sam Altman's statements shifted dramatically from 2016 (calling Trump a dictator) to 2026 (calling him a strong leader), reflecting how business circumstances change the political positions CEOs are willing to take publicly

- The contradiction between stated corporate values (democracy, human rights, privacy) and actual business incentives (profit, government relationships, growth) shapes how companies respond to political crises

- Employee activism has emerged as more effective pressure tool than external activism because it directly affects hiring, retention, and company culture, forcing leadership to engage with values-based demands

Related Articles

- ChatGPT 5.2 Writing Quality Problem: What Sam Altman Said [2025]

- Pornhub's UK Shutdown: Age Verification Laws, Tech Giants, and Digital Censorship [2025]

- Golden Dome Missile Shield: How Trade Wars Block Allied Defense Plans [2025]

- Northwood Space Lands 50M Space Force Contract [2026]

- GDC 2026 Immigration Crisis: Why International Developers Are Staying Home [2025]

- Palantir's ICE Contract: The Ethics of AI in Immigration Enforcement [2025]

![Tech CEOs on ICE Violence, Democracy, and Trump [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/tech-ceos-on-ice-violence-democracy-and-trump-2025/image-1-1769613120405.jpg)