Singapore's Telecom Crisis: UNC3886 Breaches All Four Major Carriers

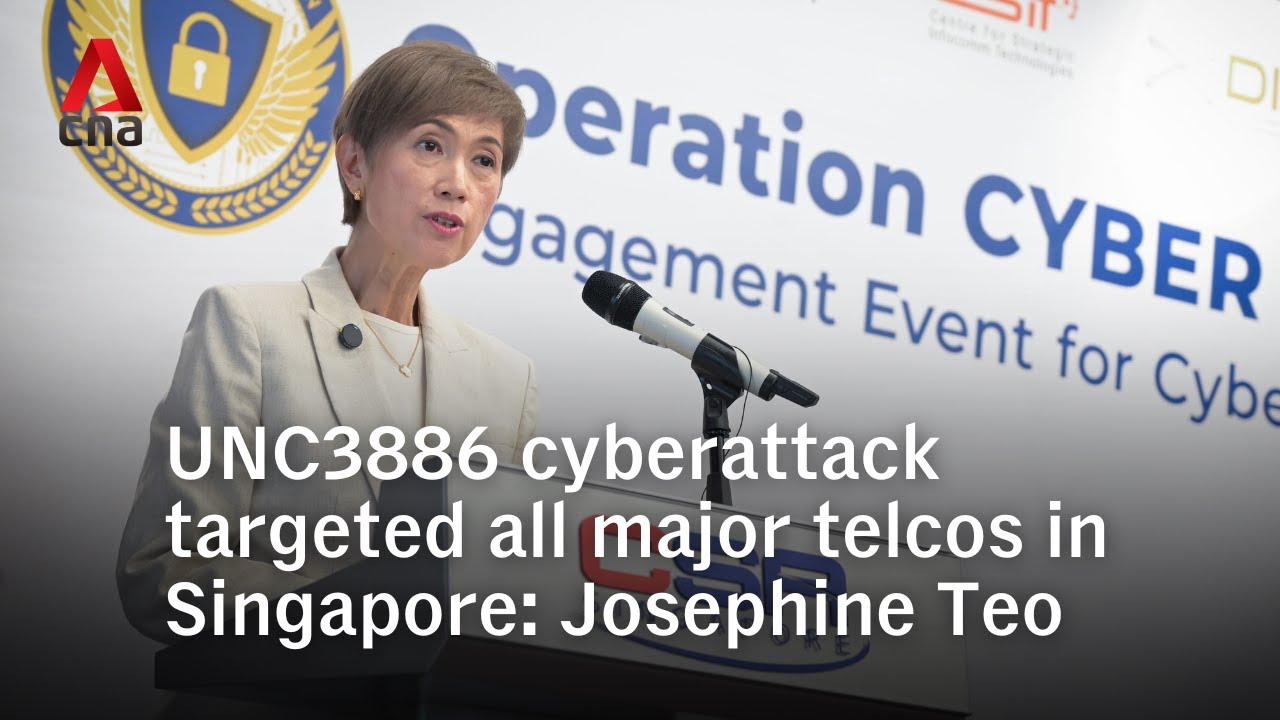

In mid-July 2025, Singapore's cybersecurity authorities uncovered something deeply unsettling. Every single one of the nation's four largest telecommunications companies had been infiltrated by the same group of state-sponsored Chinese hackers. Not one breach. Not two. All four, simultaneously targeted by the same sophisticated adversary.

The threat actor behind the campaign is a group called UNC3886, a Chinese state-sponsored operation with a documented history of targeting critical infrastructure across multiple countries. This wasn't a fishing expedition or opportunistic attack. Investigators described it as "deliberate, targeted, and well-planned," using some of the most advanced exploitation techniques in the hacker's toolkit.

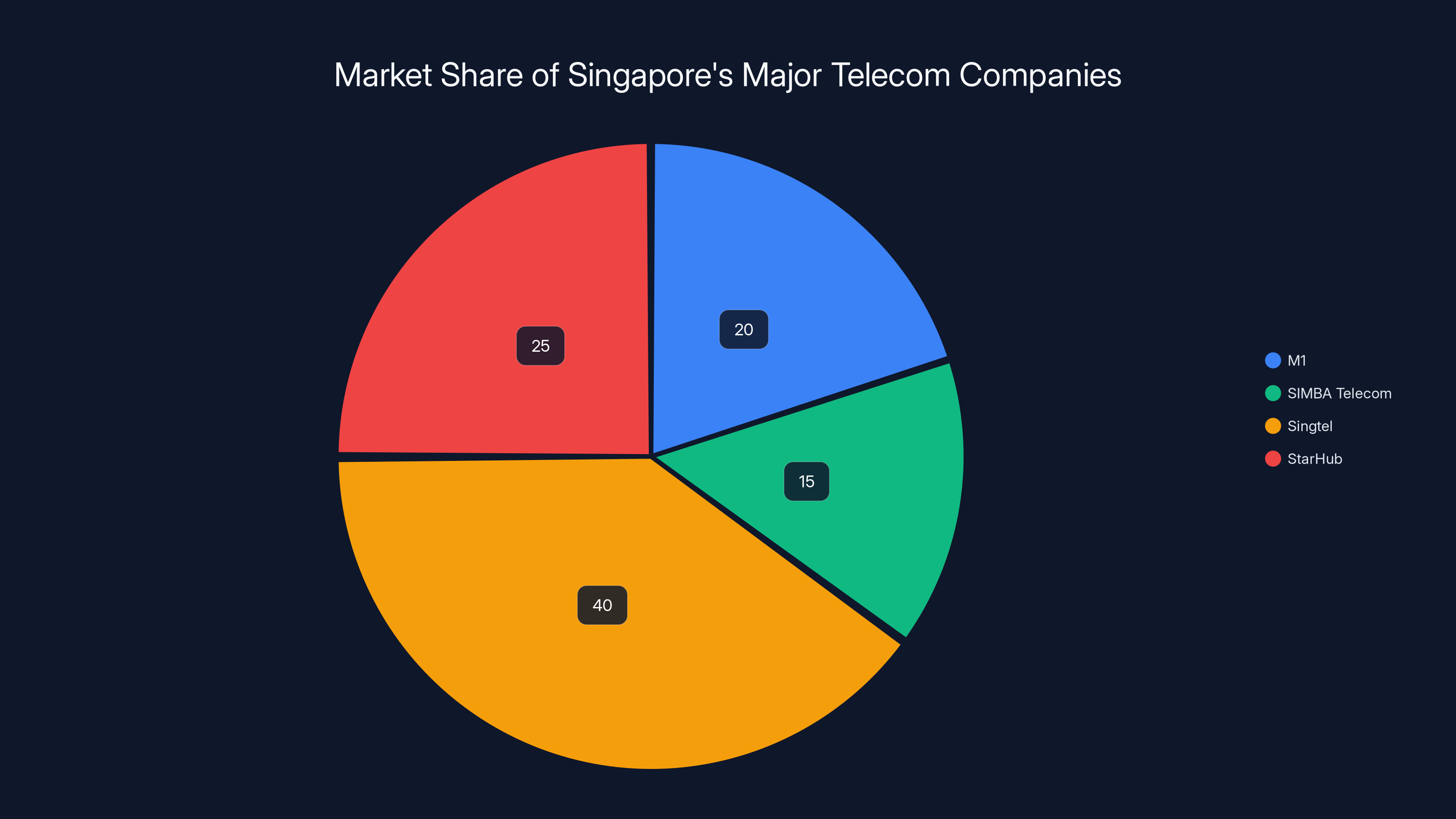

The four companies hit were M1, SIMBA Telecom, Singtel, and Star Hub. Together, they control the vast majority of mobile and fixed-line telecommunications traffic in Singapore. If an attacker wanted to monitor communications, intercept calls, or gather intelligence on the nation's digital infrastructure, breaching all four would be the ultimate prize.

But here's what makes this case unusual: despite gaining deep access into these critical systems, the attackers largely failed. No customer data was stolen. No services went down. No sensitive government communications were intercepted. Singapore's government reported that while UNC3886 managed to "gain unauthorized access into some parts of telco networks," they "did not get far enough to have been able to disrupt services."

Still, the fact that they got in at all is terrifying. Because it proves that even in a nation with some of the world's most sophisticated cybersecurity defenses, state-sponsored actors can breach critical infrastructure. The only question is whether they'll succeed next time.

TL; DR

- All Four Carriers Hit: UNC3886 simultaneously targeted Singapore's four largest telecom providers (M1, SIMBA Telecom, Singtel, Star Hub) in a coordinated state-sponsored campaign

- Sophisticated Exploitation: Attackers used advanced techniques including zero-day firewall vulnerabilities and rootkit malware to breach critical systems

- Limited Damage: Despite gaining unauthorized access, no customer data was exfiltrated, services remained operational, and Singapore contained the threat

- Attribution Clarity: Intelligence agencies attribute the attack to Chinese state-sponsored actors with high confidence, though China denies involvement as expected

- Broader Pattern: This represents the latest in a series of Chinese cyberattacks targeting global telecom infrastructure, including similar campaigns in the US and Taiwan

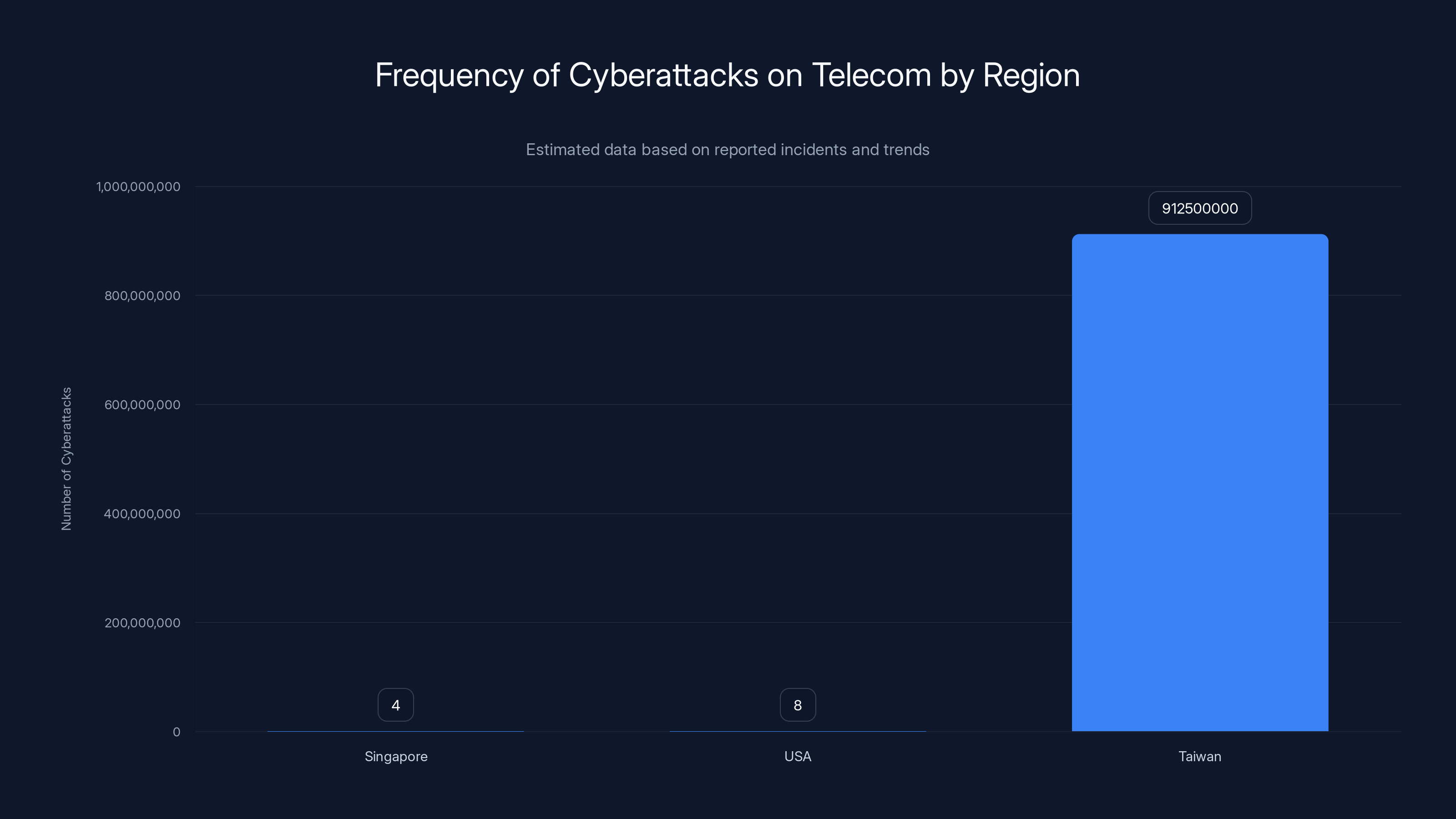

Estimated data shows Taiwan faces the highest number of cyberattacks, with over 2.5 million attempts daily, compared to the targeted attacks in Singapore and the USA.

The Attack Timeline: When Silent Intrusions Became Public Knowledge

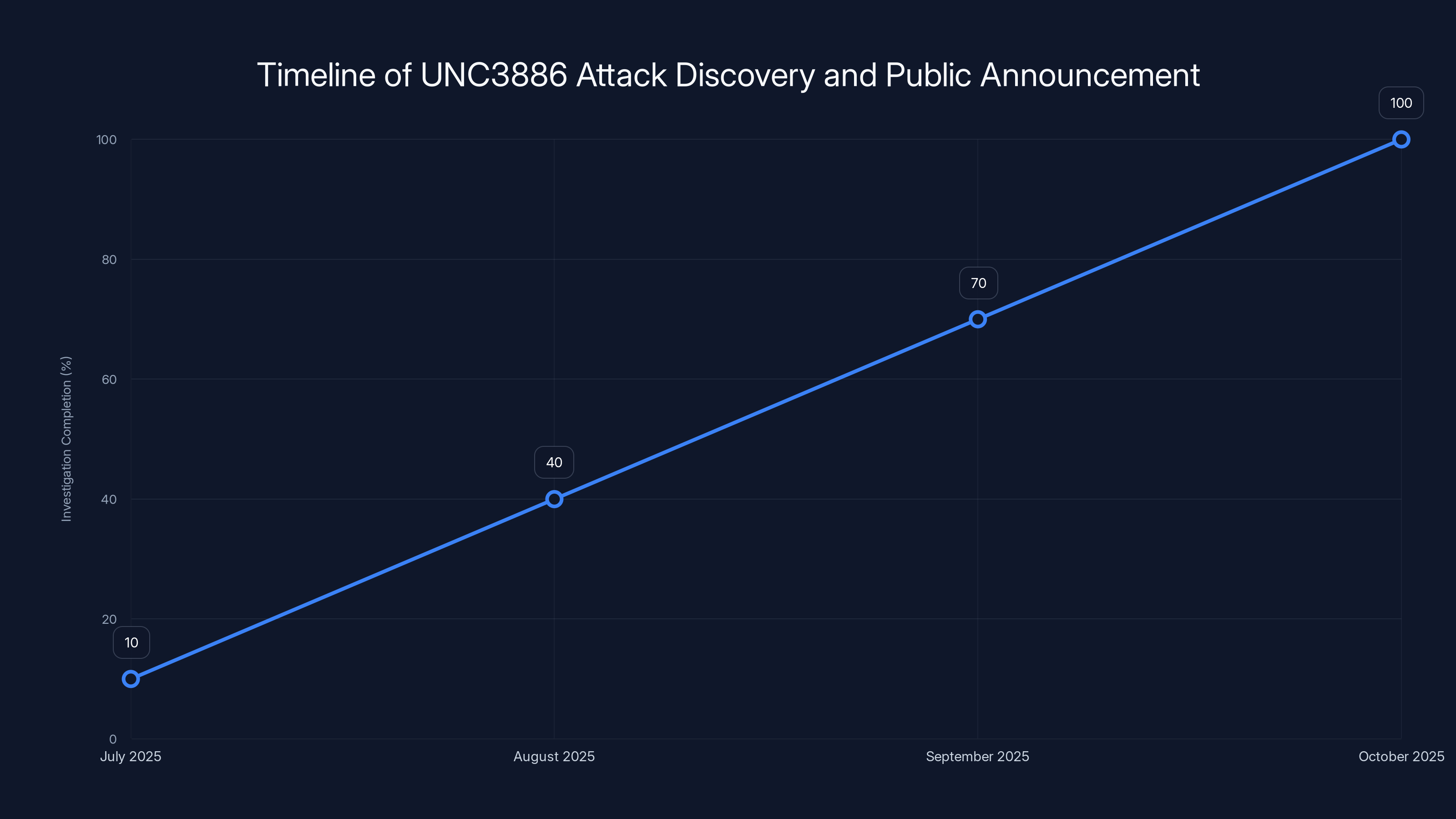

The discovery of the UNC3886 campaign didn't happen overnight. The first suspicious activity was detected in mid-July 2025, but Singapore's Cyber Security Agency (CSA) made a deliberate strategic choice not to immediately publicize the breach.

This wasn't a cover-up. It was operational security. By keeping the attack quiet during the initial investigation phase, Singapore's authorities could work with the telecom companies to trace the full extent of the intrusions, identify how the attackers got in, and begin implementing countermeasures without the attackers knowing they'd been detected.

The reasoning is sound: if UNC3886 knew that Singapore was onto them, they'd immediately cover their tracks, delete their access paths, and disappear into the digital shadows. They'd learn from their mistakes and come back even more prepared next time. So the CSA waited, investigated, and only went public once they'd gathered enough intelligence to understand what happened.

This timeline matters because it shows Singapore treating the breach as an ongoing threat, not a historical incident. The investigation itself took weeks. The attacks had been happening, undetected, for some period before July. Once discovered, it took additional time to map out the full scope across all four carriers.

When the news finally broke, it wasn't from a nervous press release. Singapore's government released detailed technical analysis, attribution confidence levels, and specific information about the attack vectors used. This transparency, even while maintaining operational security around ongoing countermeasures, signaled confidence in their understanding of what happened.

The timing also matters geopolitically. Singapore sits at one of the world's most important strategic chokepoints, sitting between China and Western allies, with major sea lanes and digital corridors flowing through its territory. Any access to Singapore's telecommunications infrastructure gives an attacker unprecedented insight into regional intelligence, business communications, and government operations.

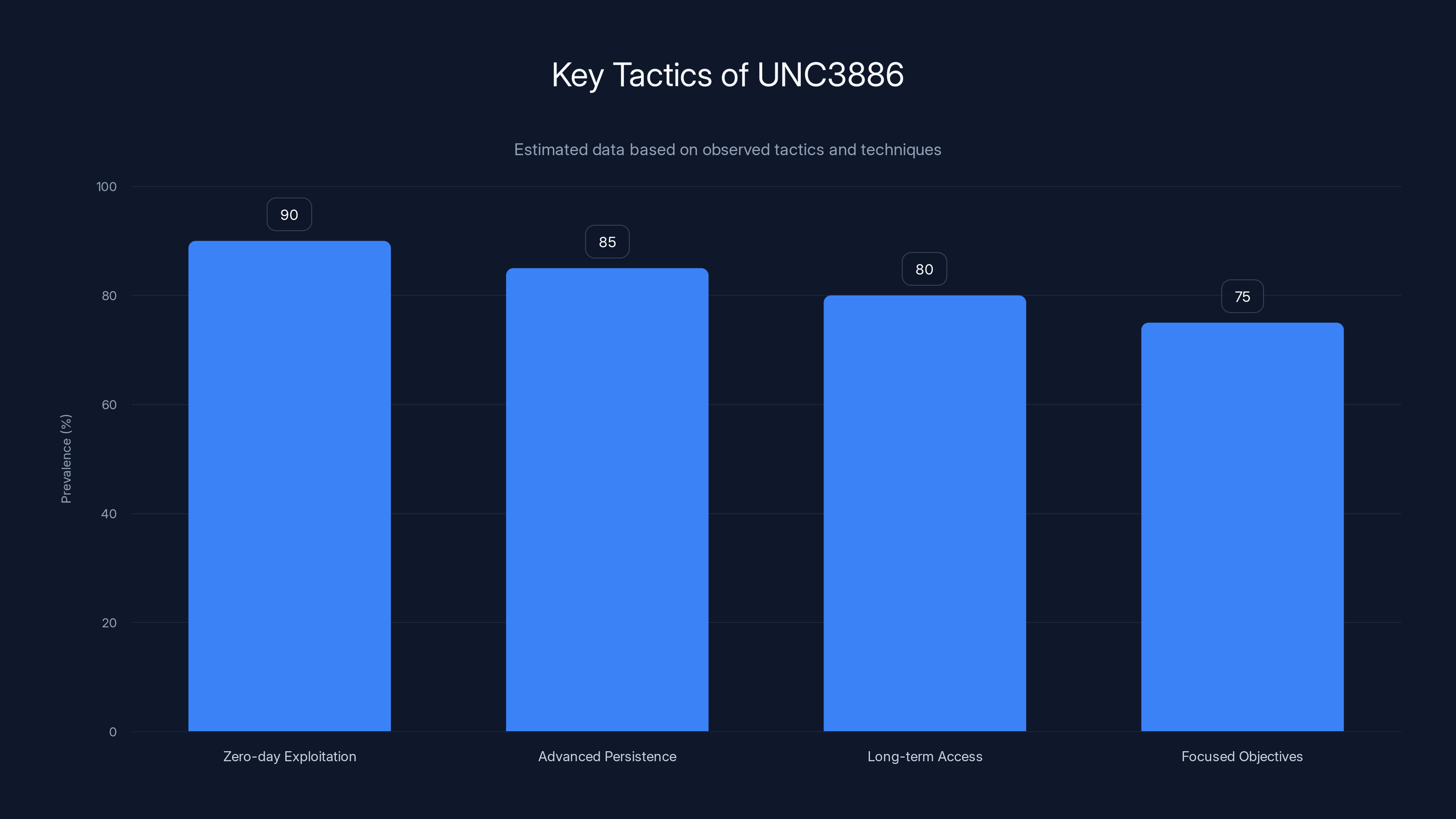

UNC3886 employs highly sophisticated tactics, with zero-day exploitation being the most prevalent. Estimated data reflects typical usage patterns.

Understanding UNC3886: The Chinese State-Sponsored Threat Actor

UNC3886 isn't a random hacking group cobbled together from the dark corners of the internet. The designation "UNC" stands for "Uncategorized," a naming convention used by Mandiant (Google Cloud's elite threat intelligence division) for threat actors they've observed but not yet fully classified into existing tracked campaigns.

What we know about UNC3886 paints a picture of a highly resourced, extremely sophisticated operation. The group has been observed targeting telecommunications infrastructure globally, with a particular focus on countries of strategic importance to China. They're known for:

- Zero-day exploitation: Using previously unknown vulnerabilities before vendors can patch them

- Advanced persistence techniques: Deploying rootkits and other tools designed to survive security measures and system reboots

- Long-term access: Maintaining presence in target networks for extended periods without detection

- Focused objectives: Not ransoming data or causing chaos, but gathering intelligence and maintaining access

The attribution to Chinese state-sponsored actors is based on multiple factors. The operational security practices mirror those used by China's Ministry of State Security (MSS). The targeting patterns align with known Chinese strategic interests. The tools and techniques match previous Chinese cyber operations. And the sophistication level required to execute this attack rules out simple cybercriminals or hacktivist groups.

China, as expected, has not acknowledged involvement and has denied the allegations. This follows the established pattern: any accusation of Chinese cyberattacks is met with categorical denial, regardless of evidence. But within the cybersecurity and intelligence communities, there's little doubt about who's behind UNC3886.

What's particularly notable is that UNC3886 is distinct from other Chinese cyber operations targeting telecom. They're not the same group as Salt Typhoon, which hit at least eight major US telecom carriers in December 2024. The distinction matters because it suggests China is operating multiple sophisticated teams, each potentially working on different objectives or targeting different regions. It's not a single campaign, but a coordinated strategy.

The Attack Vectors: How Hackers Broke Into Four Carriers Simultaneously

Gaining access to a single telecommunications network is extraordinarily difficult. Getting into four simultaneously, in a coordinated fashion, requires understanding the technical architecture of each carrier, identifying vulnerabilities in their defenses, and exploiting them before the companies know they're under attack.

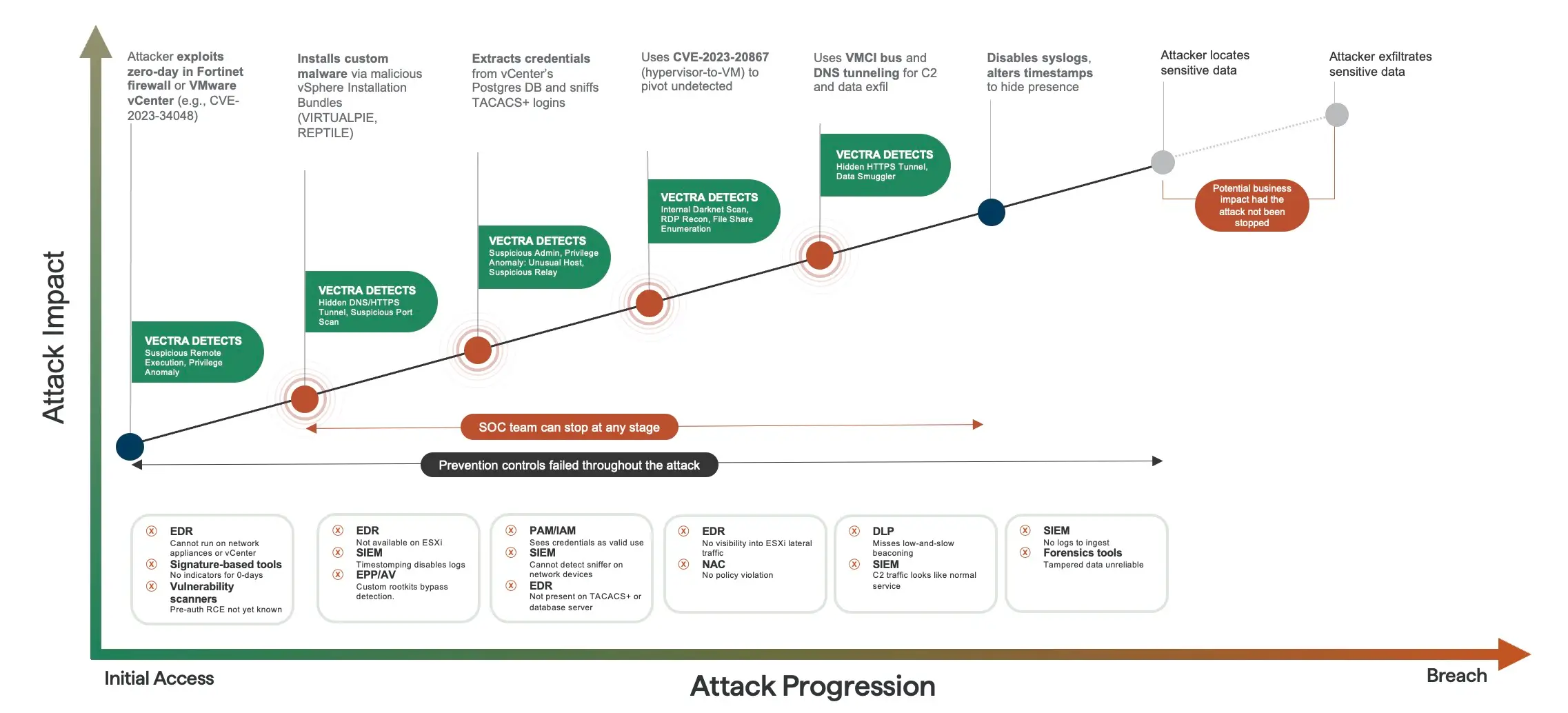

UNC3886 used several key attack vectors:

Zero-Day Firewall Vulnerabilities

The primary entry point was through zero-day exploits in firewall systems. These are vulnerabilities that neither the firewall vendors nor the telecom companies knew about. Zero-days are the holy grail of hacking because they work reliably, before defenders can patch them.

Most firewalls are perimeter security devices, positioned between the internal network and the internet. They're literally the first line of defense. If you can break through a firewall with a zero-day, you're already inside the network's outer defenses, and you can begin moving laterally toward more valuable targets.

The specific firewalls targeted weren't disclosed by Singapore's government, but evidence from the investigation suggested widespread use of commercial firewall solutions across Singapore's telecom sector. UNC3886 likely discovered a vulnerability in one of these systems, weaponized it, and then deployed it against all four carriers in rapid succession.

Rootkit Installation and Persistence

Once inside the network, the attackers needed to maintain access without being detected. They deployed rootkits, which are pieces of malware that run at the operating system level, giving attackers god-like access to compromised systems.

Rootkits are sophisticated because they're designed to hide from security tools. Traditional antivirus software runs in user-space, meaning it exists at a lower privilege level than the rootkit. A well-designed rootkit can literally hide from the tools trying to detect it, making it nearly invisible to standard security monitoring.

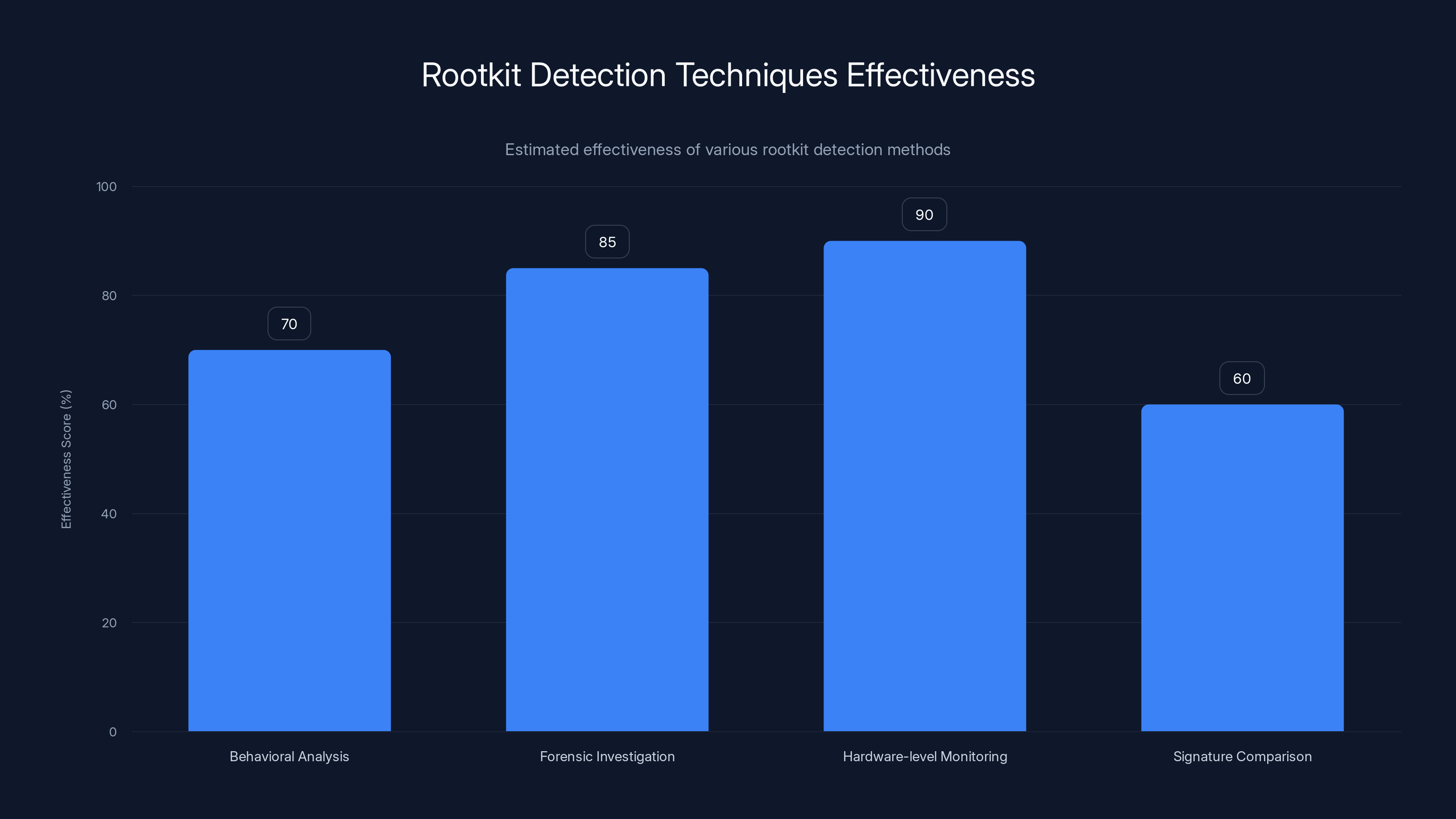

This is why the discovery of these rootkits was significant. Singapore's defenders likely found them through behavioral analysis or forensic investigation of suspicious network activity, not through traditional malware detection. Finding a rootkit means finding something designed specifically to remain hidden, which indicates your defenders are quite good.

Lateral Movement Within Networks

Once inside, UNC3886's operatives would have used their rootkit access to:

- Map the internal network architecture

- Identify which systems handle what functions

- Find and exploit additional vulnerabilities in internal systems

- Move toward high-value targets like billing systems, call records, and customer databases

This is where Singapore's defense worked. The attackers could move laterally, but they couldn't get to the most sensitive systems. In one instance, they managed to access critical systems but "did not get far enough to have been able to disrupt services." This phrasing suggests they got close to command-and-control systems or service infrastructure, but not quite there.

Advanced Reconnaissance

Before launching attacks, UNC3886 likely conducted extensive reconnaissance on each carrier. This would have involved:

- Scanning for open ports and services

- Researching publicly available information about network architecture

- Testing for known vulnerabilities

- Probing defenses to understand detection capabilities

- Possibly using information from previous breaches to understand industry-standard telecom configurations

The fact that all four carriers were hit simultaneously suggests this reconnaissance was comprehensive. You don't compromise four large organizations at once without knowing exactly how to break into each of them.

Hardware-level monitoring is estimated to be the most effective method for detecting rootkits, followed by forensic investigation. Estimated data.

The Impact Assessment: What Didn't Happen (And Why That's Important)

Here's what makes this breach unusual in the landscape of major cyberattacks: the attackers didn't accomplish their objectives, at least not the obvious ones.

No customer data was stolen. Singapore is incredibly privacy-conscious, and a major telecom data breach would trigger international outcry. If customer records, payment information, or personal details had been exfiltrated, we'd be hearing about identity theft and fraud notifications across Southeast Asia. Instead, there's been nothing.

No services were disrupted. All three carriers' customers continued making calls, sending texts, and using data. There were no outages attributed to the attack. No degradation of service quality. For customers, the attack might as well not have happened.

No sensitive government communications were intercepted. Singapore maintains secure government networks that operate separately from commercial telecom infrastructure. While UNC3886 got into the telcos, there's no indication they breached government-specific security measures.

But here's the critical bit: the absence of these dramatic impacts doesn't mean the attack was unsuccessful. It means the attack had different objectives.

Telecommunications companies sit at the intersection of everything. Phone calls flow through their infrastructure. Text messages are routed through their systems. Internet traffic passes through their connections. Call records show who called whom, when, and for how long. Metadata from these systems can be extraordinarily valuable for intelligence purposes.

A state-sponsored actor interested in signals intelligence doesn't necessarily care about stealing customer credit card numbers. They care about:

- Identifying targets of interest: Who in Singapore is calling whom? Which government officials, business leaders, or military officers have contact with foreign entities?

- Establishing persistent monitoring: Once inside the infrastructure, can they intercept specific calls or messages of interest?

- Understanding network architecture: How does Singapore's communications infrastructure work? What are the choke points? Where can leverage be applied?

- Maintaining future access: Plant tools that will continue to work even after this particular attack is discovered

From this perspective, a "failed" attack where the intruder gets in but doesn't steal obvious data might actually be a successful intelligence-gathering operation. The attacker learns the layout of the land, installs persistent monitoring tools, and prepares for future operations.

This distinction is crucial for understanding why Singapore treated this seriously and transparently, rather than quietly patching and moving on.

The Broader Context: Chinese Attacks on Global Telecom

UNC3886's attack on Singapore's four carriers isn't an isolated incident. It's part of a pattern of Chinese state-sponsored attacks on telecommunications infrastructure globally.

Salt Typhoon's US Campaign

In December 2024, just seven months before the Singapore attack, the US detected a massive cyber operation against American telecommunications companies. The threat actor, tracked as Salt Typhoon, had breached at least eight major US telecom carriers.

Salt Typhoon's campaign followed a similar playbook: gain access through initial exploits, maintain persistence through advanced tools, and position themselves for long-term intelligence gathering. US agencies linked the operation to China's Ministry of State Security, with high confidence.

The implications were staggering. The US government later acknowledged that Salt Typhoon's access could theoretically have enabled the interception of phone calls, the collection of text messages, and the gathering of massive amounts of metadata about American communications. Critically, some of the compromised telecom systems stored call records in plain text, meaning an attacker with system access could read them directly.

Taiwan's Continuous Barrage

Meanwhile, Taiwan has been under virtually constant cyber assault from China. In 2025 alone, Taiwan's cybersecurity agencies reported over 2.5 million cyberattacks per day originating from China. While most of these are automated probes and scanning attempts, a substantial subset represents sophisticated attacks against critical infrastructure.

Taiwan's geography and geopolitical situation make it an obvious intelligence target for China. Nearly everything Taiwan does digitally is of interest to Beijing. Banking systems, government communications, military networks, power infrastructure, and manufacturing facilities all represent high-value targets.

The Pattern Recognition Problem

What ties these incidents together isn't just that they're all attributed to China. It's the sophistication, the scale, and the focus on telecommunications infrastructure specifically. Across the US, Taiwan, and Singapore, Chinese state-sponsored actors are pursuing the same strategic objective: access to telecommunications infrastructure that would enable mass surveillance, intelligence collection, and potential disruption of critical services.

This represents a fundamental shift in cyber warfare strategy. Rather than destructive attacks (ransomware, data theft, service disruption), the focus is on persistent, stealthy access that enables intelligence gathering without alerting defenders.

Telecommunications infrastructure is the logical target because it's foundational. Everything depends on communications. Armies coordinate through phones. Businesses conduct transactions over networks. Governments issue orders electronically. Intelligence agencies conduct surveillance digitally.

For a great power trying to project influence or prepare for potential conflict, controlling or accessing a nation's telecommunications infrastructure is more valuable than controlling a single bank or a single government agency. It's the ultimate intelligence collection platform.

Estimated data shows Singtel holds the largest market share among Singapore's telecom companies, followed by StarHub, M1, and SIMBA Telecom. Estimated data.

Singapore's Response: Coordination and Transparency

How Singapore handled the UNC3886 disclosure reveals something about how mature cybersecurity governance works at the national level.

The Cyber Security Agency's Role

Singapore's Cyber Security Agency (CSA) is responsible for protecting the nation's critical information infrastructure. They're the equivalent of the US Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA), but for Singapore. When the CSA detected the attack, they immediately began coordinating with the four affected telecom companies.

This coordination is critical. In most countries, there's a natural tension between government agencies and private companies. Companies are reluctant to admit they've been hacked because it damages reputation and stock price. Governments want companies to report breaches so they can understand threats. Singapore's approach seems to have overcome this tension, at least in this case.

The CSA worked with each carrier to investigate the scope of the breach, understand the attack vectors, implement containment measures, and develop remediation plans. The agency held information close during this process, not publicizing anything until they had a clear picture.

The Public Statement

When Singapore did go public, the announcement was detailed and specific. Rather than vague warnings, the CSA released:

- The name of the threat actor (UNC3886)

- The nature of the vulnerabilities exploited (zero-day firewall exploits, rootkits)

- The scope of the attack (all four major carriers)

- The outcome (limited access, no data exfiltration, no service disruption)

- Confirmation that ongoing countermeasures were in place

This level of transparency serves multiple purposes. It signals to Singapore's citizens and international partners that the government understands the threat and is managing it. It provides actionable intelligence to other nations' security agencies who may also be targets. It demonstrates that Singapore has the forensic capability to investigate state-sponsored attacks.

It also implicitly signals to China that Singapore knows exactly what happened. There's no ambiguity that allows for plausible deniability. Singapore's message was clear: we know you attacked our telecom infrastructure, we've contained the threat, and we're telling the world about it.

Industry Coordination

Beyond the government response, Singapore's telecom companies immediately began implementing security upgrades. The specifics aren't public, but likely measures include:

- Patching the zero-day vulnerabilities in firewall systems

- Removing rootkits and other persistent threats

- Implementing enhanced network monitoring and behavioral analysis

- Hardening critical systems to resist lateral movement

- Deploying incident response tools and security personnel

- Increasing collaboration with government cybersecurity agencies

The fact that all four carriers faced the same threat actually creates an opportunity for industry-wide improvement. The carriers can share threat intelligence with each other, coordinate on security improvements, and implement industry standards for detecting similar attacks in the future.

The Technical Deep Dive: How Firewalls Get Compromised

To understand why a zero-day firewall vulnerability is so dangerous, you need to understand what firewalls do and where they sit in network architecture.

Firewall Architecture Basics

A firewall is essentially a traffic cop for networks. It sits at the boundary between your internal network and the internet, examining every packet of data that flows through it. The firewall has rules that determine which traffic is allowed and which is blocked.

A typical rule might look like: "Allow TCP port 80 (web traffic) from the internet to the web server on 10.0.1.5, but block everything else." The firewall enforces these rules for every single packet.

The problem with firewalls is that they're complex software. Modern firewalls might have millions of lines of code, handling hundreds of different protocols, examining traffic at multiple layers (network layer, transport layer, application layer), and performing deep inspection of packet contents.

Complex software has bugs. Some of those bugs are security vulnerabilities. A zero-day firewall vulnerability is a bug that:

- Allows an attacker to bypass normal firewall rules

- Works without requiring any authentication

- Doesn't trigger security alerts or logs

- The vendor doesn't know about (zero-day)

Imagine a traffic cop with a security flaw in their logic. They're supposed to stop anyone without proper authorization, but due to a mistake in their processing, certain types of traffic with a specific format can slip through. An attacker who discovers this flaw can craft traffic that looks like something the firewall allows, but actually contains malicious content.

The Exploitation Process

UNC3886's exploitation of zero-day firewall vulnerabilities likely followed this process:

- Discovery: Researchers working for China's state-sponsored cyber operation discover a vulnerability in a widely-used firewall

- Weaponization: The researchers create exploit code that reliably triggers the vulnerability

- Testing: The exploit is tested in controlled environments to ensure it works

- Deployment: Operators begin scanning the internet for potential targets running vulnerable firewalls

- Exploitation: The exploit is launched against Singapore's telecom companies

- Initial access: The exploit creates a foothold inside the network

- Expansion: From this foothold, operators deploy additional tools (rootkits, remote access tools, persistence mechanisms)

The window of vulnerability can be months or even years. The vendor doesn't know about the bug, so they're not developing a patch. The organization using the firewall has no idea their defense is compromised. The attacker maintains access, gathering intelligence, until someone discovers the breach through other means (security research, incident investigation, etc.).

Why Firewall Vulnerabilities Are Critical

The reason the Singapore attack focused on firewall exploitation is clear: firewalls are the first line of defense. If you can get through the firewall, you're already inside the network's perimeter defenses. From there, other security measures (antivirus, endpoint detection, network monitoring) become your secondary challenges.

Moreover, firewall vulnerabilities are particularly valuable for state-sponsored actors because they're reusable. Discover one zero-day in a commercial firewall, and you can exploit it against every organization using that product. A single vulnerability might affect thousands of targets globally.

This is why software vendors take firewall security extremely seriously. The vendors of commercial firewalls maintain rapid response teams ready to develop patches the moment a vulnerability is discovered. But until that discovery, the vulnerability remains exploitable.

The investigation of the UNC3886 attack progressed over several months, with public disclosure occurring once a comprehensive understanding was achieved. Estimated data.

Rootkits: The Invisible Persistence Tool

Once UNC3886 broke through the firewall, they deployed rootkits to maintain access. Understanding what rootkits do explains why their discovery was such a significant part of the investigation.

How Rootkits Work

A rootkit is malware designed to hide. The name comes from "root" (the administrator account in Unix systems) and "kit" (a toolkit). A rootkit gives attackers root-level access while remaining invisible to security tools.

The classic approach to invisibility is running at a higher privilege level than the tools trying to detect the rootkit. On a Linux or Windows system:

- User-level programs (like antivirus software) run with limited permissions

- Kernel-level rootkits run at the operating system level, above user-level programs

A kernel-level rootkit can intercept calls from antivirus software to the file system. When the antivirus asks "is this file infected?", the rootkit can lie and say "no" without actually checking. The antivirus has no way to know it's being deceived because the rootkit is running at a higher privilege level.

This is why finding a rootkit requires sophisticated detection techniques:

- Behavioral analysis: Looking for unusual network connections, system calls, or process behavior that might indicate a rootkit

- Forensic investigation: Analyzing system logs, memory dumps, and file system metadata to spot inconsistencies

- Hardware-level monitoring: Some systems can detect rootkits by monitoring the CPU and memory at a level the rootkit can't intercept

- Comparison with known signatures: If you've seen a similar rootkit before, you might recognize its characteristics

The Persistence Problem

Rootkits solve the persistence problem. An attacker who breaks into a system through a firewall vulnerability might only have that one entry point. If the exploit is patched, that entry point closes. The attacker is locked out.

But if the attacker can install a rootkit before the vulnerability is patched, they maintain access indefinitely. Even if the firewall is patched, the rootkit continues running inside the network, giving the attacker persistent access.

This is why finding and removing rootkits is such a critical part of incident response. You can't just patch the vulnerability and hope the attacker is gone. You have to find every persistent tool they've installed, remove it, and verify they don't have any other way back in.

Singapore's discovery of rootkits in the compromised systems indicates they had to do deep forensic investigation. Finding a rootkit means finding something designed specifically not to be found, which requires either luck or extremely sophisticated detection capabilities.

The Intelligence Value: What China Probably Wanted

While we'll never know exactly what UNC3886 intended because they were discovered before completing their objectives, we can infer from their actions and from similar Chinese cyber operations what they were probably after.

Call Metadata and Communications Patterns

Telecommunications companies maintain massive databases of call records. Even if the content of calls is encrypted, the metadata is often stored in plain text:

- Who called whom

- When the call occurred

- How long the call lasted

- Which cell towers were used (for mobile calls)

- Geographic location data (from cell tower triangulation)

This metadata is extraordinarily valuable for intelligence purposes. If you can access a complete database of call records for an entire country, you can build social network maps showing who interacts with whom. You can identify foreign diplomats and agents based on who they call. You can spot espionage networks by looking for unusual communication patterns.

China is extremely interested in understanding Singapore's internal political structure, business relationships, and any foreign intelligence operations conducted from Singapore. Access to call metadata would provide unprecedented insight into all of these areas.

Text Messages and Communications Content

Older telecommunications infrastructure stored SMS messages in plain text in some systems. While modern systems increasingly use encryption, a state-sponsored attacker with root access to telecom systems might be able to:

- Read SMS messages before they're encrypted

- Access stored messages in backup systems

- Decrypt messages if they can obtain encryption keys from compromised systems

For intelligence agencies, being able to read text messages sent by specific targets is incredibly valuable. Military officers, government officials, and intelligence personnel all use phones. Their text messages contain intelligence.

Long-Term Surveillance Capability

Beyond immediate intelligence gathering, access to telecom infrastructure enables long-term surveillance. Once rootkits are in place, a patient attacker can:

- Monitor specific phone numbers of interest

- Intercept calls to/from specific targets

- Collect information on all communications involving certain keywords or patterns

- Build intelligence on foreign operations in Singapore

This capability wouldn't be used for petty cybercrime. It would be reserved for the highest-value targets: government officials, military personnel, foreign intelligence officers, and significant business figures.

Network Architecture Intelligence

Beyond communications content, a state-sponsored attacker inside telecom infrastructure gains invaluable knowledge of how the network operates:

- How systems are connected

- Where critical nodes exist

- What security measures are in place

- How redundancy and failover are handled

- Where vulnerabilities might exist in other systems

This knowledge could be invaluable if there's ever a conflict between China and Singapore (or between China and Singapore's allies). Knowing the critical infrastructure inside out makes it possible to disrupt services with surgical precision.

China has consistently denied accusations of cyberattacks from 2015 to 2024, maintaining a pattern of denial regardless of the evidence presented. Estimated data based on documented incidents.

Defensive Implications: What This Teaches Us About Cybersecurity

The Singapore attack provides several lessons for how critical infrastructure should defend against state-sponsored threats.

The Limits of Perimeter Defense

The attack demonstrates that no perimeter is truly impenetrable to a well-resourced state-sponsored actor with zero-day exploits. Singapore's telecom companies presumably had security best practices in place, but a zero-day vulnerability defeats those practices by definition.

This argues for a defensive strategy that assumes breaches will happen, rather than betting everything on preventing breaches. This is the concept of zero-trust security: assume attackers are already inside, and verify every access request.

Network Segmentation Saves Lives

The fact that UNC3886 got inside but couldn't reach the most critical systems suggests that Singapore's telcos had implemented network segmentation. Rather than one big, flat network where someone with root access anywhere can access anything, critical systems are isolated in separate network segments with controlled access points.

When the attackers gained root access to some systems, network segmentation prevented them from immediately moving to critical infrastructure. They had to find ways to cross segment boundaries, and apparently failed before being detected.

This is a crucial defensive technique that's often neglected because it's complex and expensive to implement and maintain. But as this attack shows, it's one of the few defenses that actually works against sophisticated, well-resourced attackers.

Detection Matters More Than Prevention

Singapore's authorities detected the UNC3886 campaign through some form of investigation (behavioral analysis, forensic investigation, or intelligence sharing). The attack was discovered before the attackers completed their objectives.

This suggests that detection and response capabilities matter more than absolute prevention. You won't prevent all breaches, especially if state-sponsored actors are targeting you. But if you can detect and respond quickly, you minimize damage.

This requires:

- Sophisticated monitoring: Tools that can spot unusual patterns in network traffic and system behavior

- Skilled analysts: People who understand what normal looks like and can spot anomalies

- Rapid response procedures: Defined processes for containing incidents, preserving evidence, and removing attackers

- Information sharing: Coordination with government agencies and other organizations to gain visibility into broader threats

Critical Infrastructure Needs Government Support

Telecom companies are private businesses, but their infrastructure is critical to national security. This attack illustrates why private companies alone can't defend against state-sponsored threats.

UNC3886 had resources that only governments have: time (to discover zero-days), funding, and intelligence (about Singapore's telecom infrastructure). No private company can match those resources.

This suggests that critical infrastructure needs government support in the form of:

- Threat intelligence sharing: Governments should share information about detected threats with operators

- Assistance with incident response: Government cybersecurity agencies should have authority and ability to assist with major incidents

- Standards and requirements: Regulations should mandate security practices proven effective against state-sponsored threats

- Regulations: Some defense mechanisms (like network segmentation) are too expensive for companies to implement voluntarily but critical for national security

Singapore's transparent response to this attack, with government coordination and public disclosure, seems to reflect this understanding.

The Geopolitical Dimension: Why Singapore Matters

To understand why China would target Singapore's telecom infrastructure, you need to understand Singapore's geopolitical significance.

Singapore sits at the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula, controlling the Strait of Malacca, one of the world's most critical sea lanes. Approximately one-third of all maritime trade passes through the strait. It's narrower than you might think—just 800 kilometers at its widest point.

This strategic location makes Singapore a crucial node for:

- International trade: Ships carrying goods from Europe to Asia mostly pass through the strait

- Energy security: Most Asian countries import oil through the strait

- Intelligence gathering: Anyone monitoring the strait can observe global commerce and military movements

- International finance: Singapore is one of Asia's largest financial hubs

- Technology and innovation: Singapore hosts major regional headquarters for technology companies

From China's perspective, understanding what happens in Singapore—what communications occur, who meets with whom, what intelligence agencies operate there—is strategically crucial.

Singapore also maintains diplomatic relationships across the Asia-Pacific region in ways that make it valuable as an intelligence collection point. Foreign diplomats, military officers, and intelligence personnel coordinate regional activities through Singapore. Access to their communications would be extraordinarily valuable.

Moreover, Singapore is home to significant foreign military presence. The US Navy regularly operates from Singapore. European forces maintain presence there. Understanding what these foreign militaries are doing in the region would be highly valuable intelligence for China.

Other Nations' Telecom Infrastructure: Are They Safe?

The Singapore attack raises an obvious question: if UNC3886 can break into Singapore's four carriers, how many other countries are currently being compromised without public knowledge?

The US Experience

The US didn't even know about Salt Typhoon's breach of American telecom carriers until late 2024, months after the intrusion began. This suggests that even the world's most technologically advanced nation, with significant government funding for cybersecurity, can be compromised without immediate detection.

If American telecom carriers were being spied on without their knowledge for months, how many other countries are in the same situation right now?

The Vendor Vulnerability Cascade

Here's what's terrifying: if the firewall vulnerabilities exploited in Singapore affect widely-used commercial products, those same vulnerabilities could affect telecom carriers in dozens of countries. A zero-day that works against Singtel probably also works against carriers in:

- Thailand, Malaysia, and other Southeast Asian nations

- European countries using the same vendor products

- The United States, Canada, Australia, and other Western nations

- Potentially anywhere commercial firewalls are used

Once a vulnerability is discovered (as Singapore's CSA discovered these), it gets patched. But there might be a window of weeks or months where the vulnerability is public, Chinese attackers have adjusted their techniques to account for the patch, and other nations are still vulnerable.

The Attribution Lag Problem

Even when attacks are detected, attribution takes time. Singapore probably could only go public because they'd definitively attributed the attack to UNC3886. But most countries might detect suspicious activity without being certain of attribution, making it harder to respond or share intelligence.

This creates a time lag where:

- Attacker compromises a system (Day 0)

- Defender eventually detects the compromise (Day 30-180)

- Defender investigates to determine attribution (Day 30-360)

- Defender responds and/or goes public (Day 90-400+)

- Other nations learn from the disclosure and check their own systems

By the time other nations learn that such attacks are possible, China might already be inside their infrastructure.

Lessons for Private Companies Operating Globally

While the Singapore attack focused on telecommunication infrastructure, the lessons apply to any critical infrastructure company: banking, energy, transportation, healthcare, etc.

Assume You're Targeted

If you operate critical infrastructure or store valuable data, assume state-sponsored actors have already tried to break in. They might not have succeeded yet, but assume they will eventually succeed unless you're defending specifically against state-level threats.

This changes your defensive posture from "prevent breaches" to "minimize damage from breaches that will happen."

Implement Defense in Depth

Don't rely on any single defense. The Singapore carriers had firewalls, but firewalls alone were insufficient. They apparently had network segmentation (which prevented catastrophic damage) and detection capabilities (which found the attack).

Defense in depth means:

- Multiple layers of defense so compromising one layer doesn't compromise everything

- Redundancy so if one defense fails, backups are in place

- Diversity so a single zero-day doesn't defeat all defenses simultaneously

- Detection capabilities that work even when preventative defenses fail

Invest in Detection and Response

You won't prevent state-sponsored attackers indefinitely. But you can minimize damage by detecting breaches quickly and responding effectively.

This requires:

- Monitoring at scale: Tools that can analyze terabytes of network data looking for anomalies

- Skilled security personnel: People who understand your systems deeply enough to spot unusual behavior

- Incident response playbooks: Documented procedures for what to do when a breach is detected

- Forensic capability: Ability to understand what happened, how attackers got in, and what they did

- Threat intelligence sharing: Participation in industry groups and government programs that share threat information

Prioritize Network Segmentation

Network segmentation apparently saved Singapore's carriers from catastrophic damage. Even though attackers got inside, segmentation prevented them from reaching the most critical systems.

Implementing network segmentation is expensive and complex, but against state-sponsored threats, it's one of the few defenses that actually works.

Develop Government Relationships

Singapore's carriers apparently have strong relationships with the government's Cyber Security Agency. When the attack happened, they coordinated on investigation and response.

For critical infrastructure companies, developing relationships with government cybersecurity agencies is essential. Governments have intelligence, resources, and authority that companies don't have alone. And governments have interest in protecting critical infrastructure because it's critical to national security.

The Attribution Question: How Do We Know It Was China?

Singapore's government attributed the attack to Chinese state-sponsored actors with high confidence. But how do we know? What's the basis for such attribution?

Technical Indicators

Attribution is based on multiple factors:

- Tools used: The malware and exploits employed might match tools previously used by known Chinese groups

- Target selection: The choice of targets (Singapore's telecom infrastructure) aligns with Chinese strategic interests

- Operational security practices: How the attackers structured their operations might match known Chinese patterns

- Timing and coordination: The coordinated simultaneous attack on all four carriers matches Chinese capability and operational patterns

- Infrastructure used: The servers, botnets, or proxies used to conduct the attack might be traceable to Chinese infrastructure

Intelligence Information

Government agencies also have classified intelligence:

- Signals intelligence: Intercepted communications between operators

- Human intelligence: Information from spies or informants

- Cyber intelligence: Tracing attacks back to their sources

Much of this intelligence is classified and never publicly disclosed. Singapore's attribution is based partly on evidence they can discuss publicly and partly on classified intelligence they cannot disclose.

The Confidence Spectrum

Attribution is not binary. Intelligence agencies work on a confidence spectrum:

- Low confidence: We think it might be China, but we're not very sure

- Medium confidence: Available evidence points to China, but could possibly be someone else

- High confidence: Multiple independent lines of evidence all point to China

- Very high confidence: We have direct evidence (like intercepted communications or informant information)

Singapore apparently assessed high confidence in the attribution to UNC3886 / Chinese state-sponsored actors. They're not certain, but confident enough to publicly accuse China.

Why Attribution Matters

Attribution shapes response. If the attack was by a lone hacker, response might be arrest and prosecution. If the attack was by criminals, response might be sanctions and law enforcement cooperation. If the attack was by a state-sponsored actor, response is typically diplomatic (public accusation, international statements) and defensive (helping other nations protect themselves).

Accurate attribution is crucial because incorrect attribution could lead to misplaced blame and inappropriate response.

China's Expected Response and Denial

When Singapore attributed the attack to Chinese state-sponsored actors, China's response was predictable: categorical denial. "We categorically deny the accusations," Chinese officials or spokespeople would state, adding that accusations of Chinese cyberattacks are politically motivated and unsubstantiated.

This pattern repeats for almost every Chinese cyberattack accusation:

- 2015: China accused of hacking OPM (Office of Personnel Management), stealing 21 million security clearances. China denied it.

- 2020: China accused of Salt Typhoon campaign against US telecom carriers. China denied it.

- 2024: China accused of hacking multiple US telecom carriers and German government. China denied it.

The denial doesn't reflect uncertainty about Chinese involvement. It reflects a strategic choice to deny responsibility regardless of evidence. The denial serves several purposes:

- Preserves plausible deniability: Even though intelligence agencies believe China is responsible, the formal denial provides political cover for any nations that want to downplay the attack

- Supports the narrative: From China's perspective, admitting to attacks would undermine their narrative that they're a responsible global citizen

- Reduces consequences: If everyone knows you're hacking but you deny it, you can maintain diplomatic relationships while still conducting operations

- Tests international response: The denial indicates how seriously other nations will treat the accusation

Unlike criminal prosecution where guilt must be proven beyond doubt, international attribution is about preponderance of evidence. Multiple US intelligence agencies conclude China's responsible. Singapore's government concludes China's responsible. The cybersecurity community broadly agrees. But China can still deny with impunity because there's no international court that can enforce a judgment.

The Evolution of Telecommunications Hacking

The UNC3886 attack represents the evolution of a trend: state-sponsored actors increasingly targeting telecommunications infrastructure. Understanding this evolution provides context for the attack.

Phase 1: Incident Responsiveness (Pre-2010)

Early state-sponsored cyberattacks focused on immediate objectives: stealing data, disrupting services, or gathering intelligence on specific targets. Attacks were tactical rather than strategic.

Phase 2: Infrastructure Exploration (2010-2018)

As nations realized how critical telecommunications infrastructure was, state-sponsored actors began exploring and mapping it. These weren't always attacks; they were reconnaissance missions understanding how infrastructure worked, where vulnerabilities existed, and how to access it.

Phase 3: Persistent Access (2018-2023)

State-sponsored actors shifted from gathering intelligence through attacks to establishing persistent, hidden access. The goal became less about stealing data immediately and more about maintaining long-term access for future intelligence gathering or disruption capability.

Salt Typhoon's campaign against US carriers exemplifies this phase: long-term, stealthy access established through zero-day exploits and rootkits.

Phase 4: Global Scale Campaigns (2024-Present)

The most recent phase involves coordinated, massive-scale campaigns simultaneously targeting critical infrastructure in multiple nations. Rather than one major attack per year, there are dozens of major campaigns happening concurrently.

UNC3886's simultaneous targeting of all four Singapore carriers, combined with Salt Typhoon's parallel campaign against US carriers, suggests we're in a phase where multiple state-sponsored teams are conducting synchronized campaigns.

This might reflect:

- Confidence in capability: State-sponsored actors are confident enough in their tools and techniques to deploy them at scale

- Competition: Multiple state-sponsored actors are conducting campaigns simultaneously, suggesting either competition for intelligence or independent operations

- Preparation for conflict: Establishing access and understanding infrastructure might be preparation for potential future conflicts

Future Outlook: What Comes Next?

If Singapore's attack is any indication, the future of critical infrastructure security involves state-sponsored actors with:

- Advanced exploitation capability: Zero-day vulnerabilities in critical systems

- Sophisticated persistence tools: Rootkits and other mechanisms for maintaining access

- Coordination: Multiple simultaneous campaigns against multiple targets

- Strategic patience: Willing to spend months or years inside networks gathering intelligence

What changes will this drive?

Regulatory Evolution

Expect governments to implement stricter regulations on critical infrastructure security. Singapore will likely require specific security measures for telecom companies. Other nations will follow.

Regulations will likely mandate:

- Network segmentation

- Enhanced monitoring and detection

- Incident reporting requirements

- Regular security assessments and audits

- Coordination with government security agencies

Technology Evolution

Security technology vendors will develop new approaches to detect persistent threats:

- Memory forensics: Tools that detect suspicious activity in system memory where rootkits hide

- Behavioral analysis: Machine learning systems that spot unusual patterns indicative of compromise

- Hardware-level monitoring: Chips and firmware that can detect even kernel-level threats

- Zero-trust architecture: Systems designed assuming breaches will happen and verifying every access

Defensive Strategy Evolution

Organizations will shift from "prevent breaches" to "detect and respond to breaches." This requires different investments:

- Fewer perimeter defenses (which clearly don't work against state-sponsored actors)

- More internal detection and monitoring

- Faster incident response

- More information sharing

- Better threat intelligence

Conclusion: The New Normal of Telecom Security

Singapore's discovery of the UNC3886 campaign targeting all four of its major telecom carriers represents a inflection point in the conversation about critical infrastructure security. It's not that state-sponsored cyberattacks on infrastructure are new—they've been happening for years. It's that this time, a nation has been transparent about it, providing details about how the attack worked and what it means.

The attack succeeded in breaking into the network through zero-day firewall exploits and installing rootkit persistence tools. But it failed in its ultimate objective because Singapore had implemented defensive measures (network segmentation, detection capabilities) that limited damage.

The attack also succeeded in another way: it gathered intelligence about Singapore's telecommunications infrastructure, which will inform future operations. The knowledge gained from being inside the network is valuable even if immediate intelligence collection failed.

For other nations' telecommunications carriers, the message is clear: you're being targeted right now. State-sponsored actors are probing your infrastructure, looking for vulnerabilities. Most likely, some of you already have undiscovered breaches. The question isn't whether you'll be attacked, but whether you'll detect the attack before the attackers complete their objectives.

This necessitates a fundamental shift in how critical infrastructure approaches security. It's not enough to have good firewalls and antivirus software. You need to assume breaches will happen and design systems that minimize damage when they do. Network segmentation, detection capabilities, incident response procedures, and government coordination are now table stakes for critical infrastructure operators.

Singapore's transparent response, coordinated government action, and rapid disclosure of attack details provides a model for how nations should handle such incidents. Transparency about threats enables other nations to protect themselves. Coordinated response between government and private sector enables effective defense. Rapid disclosure demonstrates competence and gives confidence to international partners.

As state-sponsored cyber operations continue to evolve and scale, expect more incidents like the Singapore attack to emerge. The question is whether the security community will learn from Singapore's experience and implement the defensive measures necessary to protect critical infrastructure from sophisticated, well-resourced, patient adversaries who are already inside.

The first step is acknowledging that state-sponsored actors are a permanent fact of life for critical infrastructure. The second step is building defenses designed specifically to counter that threat. Singapore's experience provides both the warning and the road map.

FAQ

What is UNC3886 and why is it significant?

UNC3886 is a Chinese state-sponsored threat actor tracked by Mandiant that specializes in targeting telecommunications infrastructure globally. The designation "UNC" stands for "Uncategorized," meaning it's been observed conducting sophisticated attacks but hasn't been fully classified into existing campaign designations. UNC3886 is significant because it represents a well-resourced, patient attacker willing to invest months in infrastructure reconnaissance and long-term access establishment. Its attack on Singapore's four major telecom carriers simultaneously demonstrates capability and coordination that only state-sponsored operations possess.

How did UNC3886 breach Singapore's telecom carriers?

UNC3886 used zero-day vulnerabilities in commercial firewall systems to breach the perimeter defenses of Singapore's telecommunications carriers. Once inside the network, operators deployed rootkit malware to establish persistent, hidden access. The attack was coordinated across all four major carriers simultaneously, suggesting extensive reconnaissance and preparation. The sophistication of the exploit and persistence tools indicates this was a well-planned, deliberate campaign rather than opportunistic hacking.

Why didn't the attack cause more damage?

While UNC3886 gained unauthorized access and deployed persistent tools, Singapore's carriers had implemented network segmentation that prevented the attackers from reaching the most critical systems. Additionally, Singapore's cybersecurity agencies detected the campaign before the attackers could complete their intelligence gathering objectives. The combination of detection and defense-in-depth architecture meant the attackers couldn't move from initial compromise to critical system compromise. This demonstrates that while zero-day exploits can defeat perimeter defenses, they're not sufficient to compromise well-defended critical infrastructure.

How are state-sponsored cyberattacks attributed?

Attribution is based on multiple factors including the tools and techniques used, target selection patterns, operational security practices, timing of attacks, and intelligence gathered from various sources. Security researchers match attack signatures against known threat actors. Government agencies supplement technical analysis with classified intelligence including signals intelligence and human intelligence. Attribution works on a confidence spectrum rather than absolute certainty. Singapore's attribution of the attack to Chinese state-sponsored actors represents high confidence based on multiple independent indicators aligning with known Chinese capabilities and strategic interests.

What should other telecom carriers do in response?

Other telecommunications carriers should assume they may already be compromised and implement defensive measures specifically designed to counter state-sponsored threats. This includes network segmentation to limit lateral movement, enhanced monitoring to detect persistent threats, regular security assessments and penetration testing, incident response procedures, and coordination with government cybersecurity agencies. Carriers should also implement zero-trust security architecture assuming breach inevitability rather than focusing entirely on breach prevention. Finally, participation in threat intelligence sharing with peer organizations and government agencies provides visibility into threats facing the industry.

Why is telecommunications infrastructure such a valuable target?

Telecommunications infrastructure is foundational to modern civilization. It carries all communications including phone calls, text messages, and internet traffic. Access to telecom infrastructure enables mass surveillance of communications, interception of calls and messages, and gathering of metadata showing communication patterns. For intelligence agencies, telecommunications infrastructure represents the ultimate intelligence collection platform. Additionally, understanding and potentially disrupting telecom infrastructure provides capability for influencing regional conflicts or power projection.

How does this attack compare to Salt Typhoon's US campaign?

Both UNC3886 and Salt Typhoon are Chinese state-sponsored operations targeting telecommunications infrastructure, but they appear to be distinct groups with different campaigns. Salt Typhoon breached at least eight US telecom carriers in 2024, establishing persistent access similar to UNC3886's methods in Singapore. The parallel timing of these campaigns suggests either coordinated strategy or competition for intelligence assets. Both campaigns followed similar playbooks of using zero-day exploits and rootkits to establish persistent, stealthy access. The simultaneous emergence of multiple major campaigns suggests state-sponsored cyber operations against critical infrastructure are accelerating globally.

What does this mean for countries without Singapore's security capabilities?

For nations with less developed cybersecurity capabilities, the Singapore attack is a clear warning that state-sponsored actors are actively targeting critical infrastructure globally. Most countries likely have less sophisticated detection and response capabilities than Singapore, meaning breaches might go undetected for longer periods. This argues for international assistance programs helping developing nations improve critical infrastructure security, threat intelligence sharing to provide visibility into global threats, and diplomatic pressure on state-sponsored actors. Countries should also prioritize foundational security measures like network segmentation and incident response procedures even if they can't match Singapore's detection capabilities.

Is there any way to prevent zero-day exploits?

No, zero-day exploits are unknown vulnerabilities by definition, meaning they can't be prevented through patching. However, prevention can be managed through defense-in-depth approaches that don't rely on a single line of defense. Network segmentation limits damage even if a zero-day is exploited. Detection capabilities can spot unusual behavior indicating zero-day exploitation even without knowing the specific vulnerability. Diversity of tools and technologies means a single zero-day won't defeat all defenses simultaneously. Security best practices, incident response procedures, and threat intelligence sharing all help minimize damage from zero-day exploitation even when prevention is impossible.

What was Singapore's government role in defending against this attack?

Singapore's Cyber Security Agency (CSA) coordinated investigation and response with the four affected telecom carriers. The CSA was responsible for detecting the attack, understanding its scope, implementing countermeasures, and assisting carriers with remediation. The government's role extended beyond technical response to include public communication about the threat, attribution to Chinese state-sponsored actors, and diplomatic messaging to international partners. This coordination between private carriers and government agencies appears to have been crucial to effective response. The model of government support for critical infrastructure defense is increasingly seen as essential for countering state-sponsored threats.

Key Takeaways

- UNC3886 simultaneously targeted all four of Singapore's major telecom carriers using zero-day firewall exploits and rootkit malware

- Despite gaining unauthorized access, attackers failed to exfiltrate data or disrupt services thanks to network segmentation and detection capabilities

- State-sponsored cyberattacks on telecom infrastructure are escalating globally, with parallel campaigns in the US and Taiwan suggesting coordinated strategy

- Detection and response capabilities matter more than breach prevention when facing state-sponsored threats with access to zero-day exploits

- Singapore's transparent response and government coordination provide a model for how nations should defend critical infrastructure against persistent, sophisticated adversaries

Related Articles

- SmarterTools Ransomware Breach: How One Unpatched VM Compromised Everything [2025]

- BeyondTrust RCE Vulnerability CVE-2026-1731: What You Need to Know [2025]

- Microsoft Office Vulnerability: How Russian State Hackers Exploited It in 48 Hours [2025]

- AI Security Breaches: How AI Agents Exposed Real Data [2025]

- Modern Log Management: Unlocking Real Business Value [2025]

- Claude Opus 4.6 Finds 500+ Zero-Day Vulnerabilities [2025]

![Singapore's Telecom Crisis: UNC3886 Breaches All Four Major Carriers [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/singapore-s-telecom-crisis-unc3886-breaches-all-four-major-c/image-1-1770813403110.jpg)