Microsoft Office Vulnerability: How Russian State Hackers Exploited It in 48 Hours

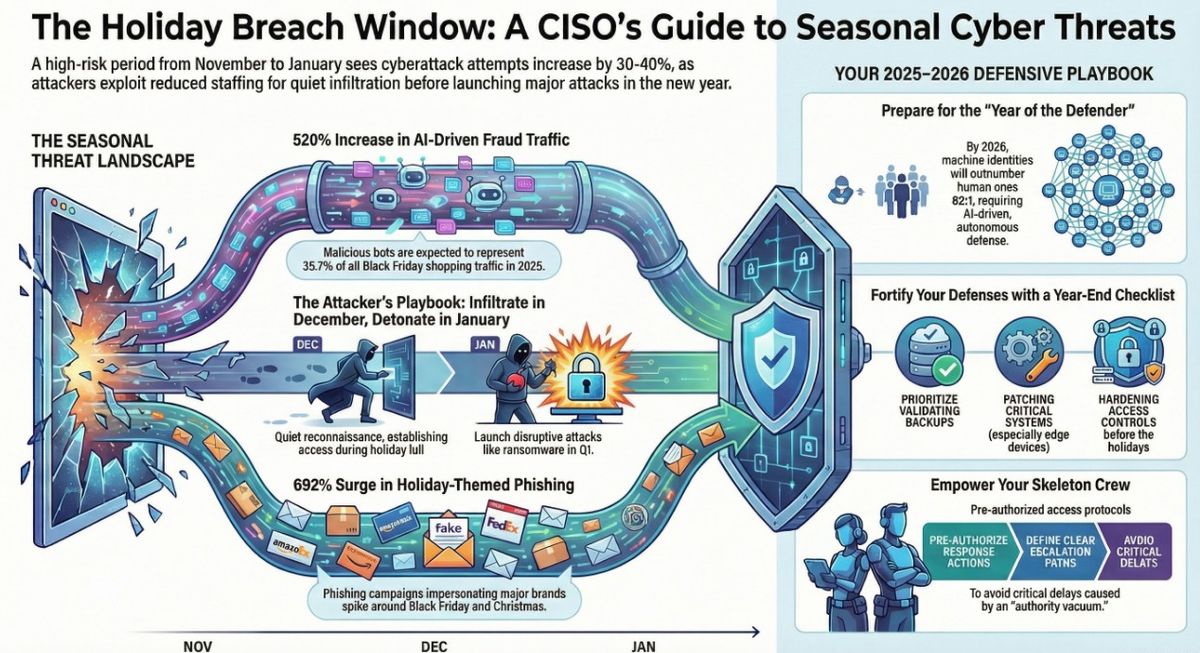

Here's something that keeps security professionals up at night: the best hackers don't wait. They move fast, and they move smart.

In late January 2026, Microsoft released an urgent, unscheduled security patch for a critical vulnerability in Office. Less than two days later, Russian state-backed hackers were already weaponizing it. Not in labs. Not in controlled tests. In actual attacks against real targets: diplomatic missions, defense ministries, and maritime organizations across Eastern Europe and beyond.

This isn't theoretical threat modeling. This is how modern cyber warfare actually works.

The vulnerability, tracked as CVE-2026-21509, gave attackers the ability to execute arbitrary code on victim machines just by sending a specially crafted email. The window between patch release and active exploitation was so narrow it might as well have been invisible. By the time most organizations even knew a patch existed, the attackers had already reverse-engineered it, built sophisticated exploits, and deployed them against targets that mattered: government agencies, transportation networks, diplomatic infrastructure.

What happened next reveals something crucial about cybersecurity in 2026: the traditional assumptions about patch timing, detection, and defense have completely broken down.

The threat group behind these attacks, known by multiple names including APT28, Fancy Bear, and Forest Blizzard, demonstrated technical sophistication that went far beyond simply exploiting a code vulnerability. They built a multi-stage infection chain designed to be invisible to endpoint protection, used encrypted payloads that existed only in memory, deployed novel backdoors that had never been seen before, and routed command-and-control traffic through legitimate cloud services that most networks allow through their firewalls.

They didn't just exploit a vulnerability. They orchestrated a targeted intelligence-gathering campaign with military precision.

TL; DR

- APT28 exploited CVE-2026-21509 within 48 hours of Microsoft's patch release, targeting defense, diplomatic, and maritime organizations across 9 countries

- The attack used two never-before-seen backdoors (Beard Shell and Not Door) designed to evade detection by hiding code execution in memory and legitimate cloud services

- The infection chain was multi-staged and encrypted, using fileless techniques that left minimal forensic artifacts on disk

- Not Door specifically monitored email to exfiltrate sensitive government communications and classified information

- The campaign lasted 72 hours with at least 29 distinct phishing lures, primarily targeting Eastern European defense ministries (40%), transportation operators (35%), and diplomatic entities (25%)

- The vulnerability window closed in under 48 hours, highlighting how rapidly state actors can weaponize zero-days

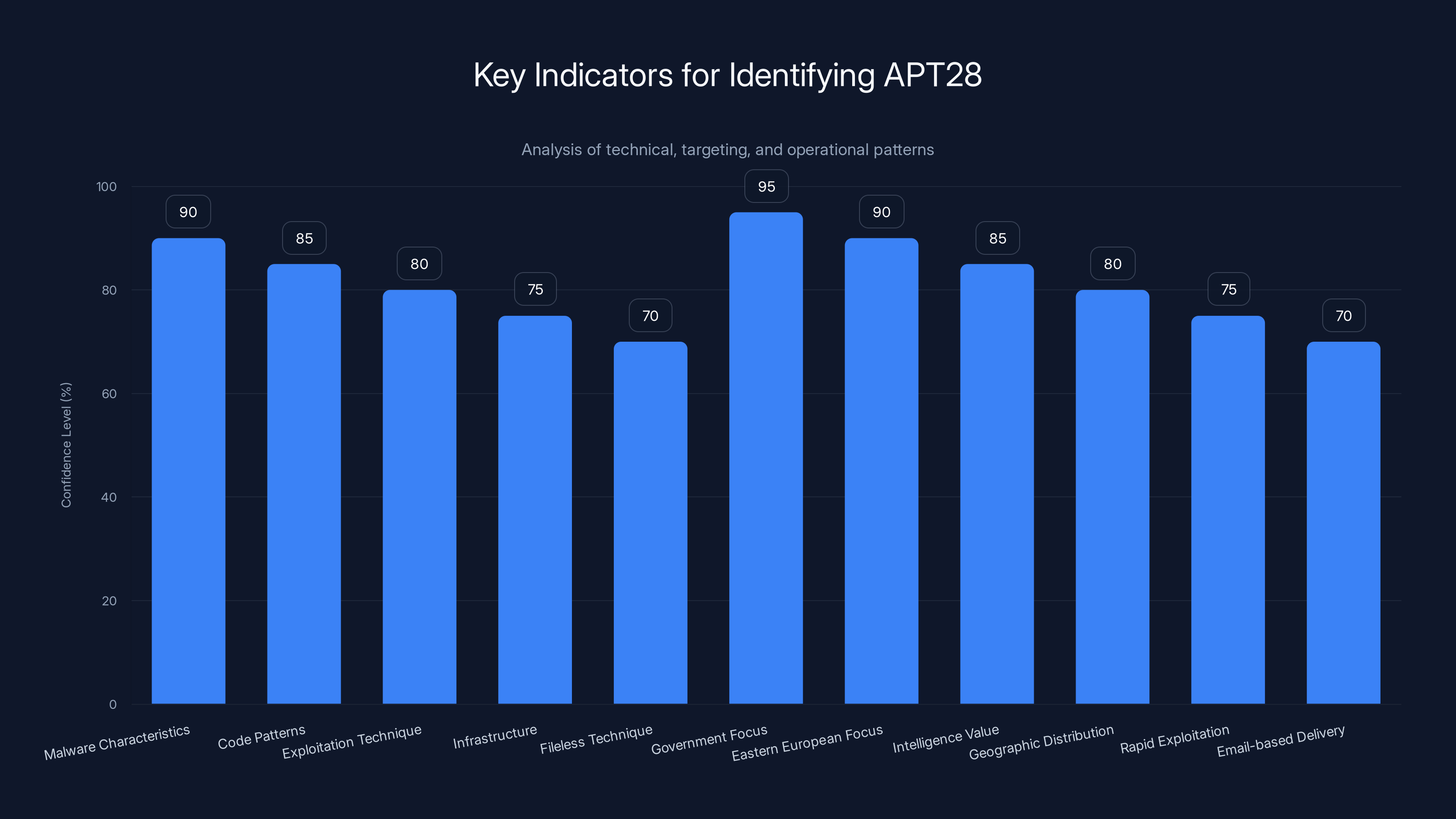

Security researchers identified APT28 with high confidence by analyzing multiple indicators, including malware characteristics and targeting patterns. Estimated data based on typical confidence levels.

Understanding CVE-2026-21509: The Vulnerability Itself

The technical details matter here, because understanding what went wrong helps explain why the exploitation was so effective.

CVE-2026-21509 is a remote code execution vulnerability in Microsoft Office. The specific mechanism involved how Office processes certain file types and embedded content. Without getting too deep into the weeds, the vulnerability allowed an attacker to craft a malicious Office document that, when opened, would execute code with the same privileges as the user who opened it.

On the surface, this sounds like a fairly standard vulnerability. Office has had exploitable issues before. The difference here is execution: the vulnerability required minimal user interaction, the exploit was reliable (worked consistently across different system configurations), and the attack surface was massive (anyone with an email account could receive the malicious document).

Microsoft's patch, released late in January, fixed the underlying code issue. But here's the critical problem: once a security patch is released, the details of what was fixed become apparent to sophisticated attackers through a process called "reverse-engineering the patch."

When Microsoft releases a patch, they're essentially announcing: "We fixed a security problem in this specific file, in this specific function, on this specific date." Skilled vulnerability researchers can compare the patched version to the unpatched version, identify exactly what changed, and work backward to understand the original vulnerability.

For attackers with significant resources, the time from patch release to exploitation can be measured in hours, not weeks or months.

Why This Vulnerability Was Critical

The severity of CVE-2026-21509 came down to several factors that made it uniquely dangerous.

First, it required no special configuration. It wasn't hidden behind an obscure setting that only affected certain deployments. It was a default vulnerability in standard Office installations.

Second, the initial access vector was familiar and trusted. The attack came via email from compromised government accounts in various countries. Recipients saw emails from colleagues, government agencies, and organizations they recognized. This wasn't an obvious phishing attack from some random domain. It was from legitimate accounts, discussing legitimate work.

Third, and most importantly, it required only one user action: opening an email attachment or clicking a link. In security terminology, this is called a "single-click" or "zero-click" vulnerability depending on the specific mechanism. Users open emails all day. They've been trained to recognize phishing. But when the email comes from a colleague's real account, discussing work topics relevant to their job, the social engineering component becomes incredibly effective.

Fourth, the vulnerability gave attackers code execution with the same privileges as the user. In many organizations, even standard users have significant access: they can read sensitive emails, access network shares, install software, and communicate with external systems. For diplomatic or defense organizations, this level of access is a serious problem.

The combination of these factors made CVE-2026-21509 a top-tier threat. Microsoft's decision to release an emergency patch rather than waiting for the next monthly security update reflected the understanding that this vulnerability was being actively exploited in the wild.

The Technical Attack Surface

Understanding the attack surface helps explain why this vulnerability was so easy to weaponize.

Office documents aren't simple text files. They're complex, compressed XML-based formats that can contain embedded objects, scripts, external links, and dynamic content. This complexity, while useful for functionality, creates a large number of potential vulnerabilities.

The specific attack vector for CVE-2026-21509 involved how Office handles certain embedded objects during the parsing process. The vulnerability wasn't in a feature that Office users would typically need or notice. It was in the underlying machinery that processes documents.

This means defenders couldn't simply turn off the feature or adjust a security setting. The feature was required for normal Office functionality. The only mitigation was applying the patch.

For IT teams managing large organizations, this created an immediate dilemma: patch immediately and risk disruptions, or delay patching and accept the risk of exploitation. Some organizations chose to disable Office macros or restrict email attachment types as temporary mitigations. But these were band-aids, not solutions.

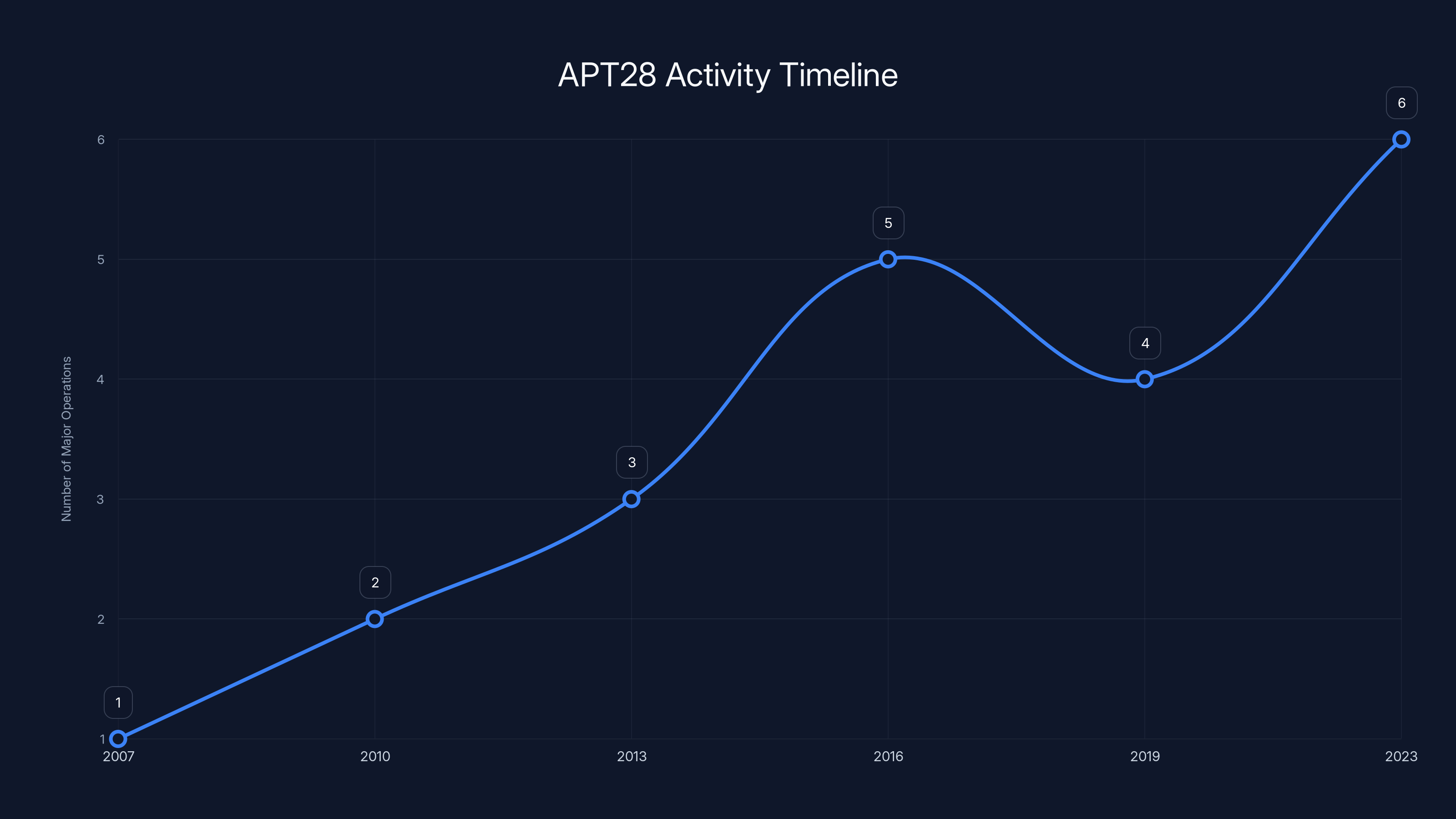

APT28 has been involved in a growing number of significant cyber operations over the years, with notable spikes in activity during key geopolitical events. Estimated data based on historical reports.

APT28: The Threat Actor Behind the Attacks

APT28 isn't a random group of hackers operating from a basement. This is a state-sponsored threat group with decades of operational history, significant resources, and demonstrated technical sophistication.

The group goes by many names: Fancy Bear, Sednit, Forest Blizzard, Sofacy, and officially APT28 in security research. Despite the different names, the technical fingerprints, targeting patterns, and operational methods are consistent enough that security researchers confidently attribute these attacks to the same group.

APT28 is believed to be operated by Russia's GRU, the Russian military intelligence agency. This attribution comes from technical analysis, targeting patterns, and in some cases, public statements by U. S. government officials and allied intelligence agencies.

The group has been active since at least 2007, which means we're talking about nearly two decades of continuous operations, evolution of tactics, and refinement of techniques.

Historical Context and Past Operations

APT28 didn't suddenly appear in January 2026 with sophisticated code and advanced tradecraft. They developed these capabilities over years of operations.

The group is known for targeting government agencies, military organizations, defense contractors, diplomatic missions, and political organizations. They've been blamed for attacks on the Democratic National Committee during the 2016 U. S. presidential election, intrusions into NATO and European defense agencies, and espionage against Georgian and Ukrainian governments.

Their historical targets reveal their primary objective: gathering intelligence on geopolitical competitors. They target defense ministries to understand military capabilities and doctrine. They target diplomatic missions to read classified communications. They target transportation and logistics operators because understanding supply chains and infrastructure is valuable intelligence.

PATTERN: Notice that the January 2026 attacks followed this exact targeting pattern. The group wasn't randomly spraying attacks hoping to hit any target. They were deliberately targeting the types of organizations that would have intelligence value to a state sponsor.

Known Capabilities and Tools

Over the years, security researchers have documented APT28's tool kit, operational patterns, and technical capabilities.

The group is known for using custom malware, stolen credentials, phishing campaigns, watering hole attacks, and zero-day exploits. They've demonstrated the ability to compromise networks, maintain persistent access, exfiltrate large amounts of data, and establish command-and-control infrastructure that's difficult to take down.

They're proficient with legitimate tools, using operating system features and built-in utilities to move laterally within networks and avoid triggering security alerts. This technique, called "living off the land," means defenders can't simply watch for suspicious tools. The attackers are using the organization's own legitimate software.

APT28 has also demonstrated the ability to develop novel exploits and zero-day vulnerabilities. While they sometimes purchase or acquire zero-days through other means, they've also shown the capability to discover vulnerabilities independently and weaponize them.

Their tradecraft is sophisticated but not always perfect. There have been operational security failures, mistakes that allowed attribution, and instances where their tools or tactics were documented and shared with the security community. But overall, APT28 operates at the level of a well-funded state intelligence agency with access to significant technical expertise.

Operational Security and Sophistication

What's notable about the CVE-2026-21509 exploitation is how operationally sophisticated the entire campaign was.

First, they used previously compromised email accounts from legitimate government organizations. This gave them trusted sending addresses and context about relevant work being discussed. It's not just "click here and get pwned." It's "here's an email that looks like it's from a government colleague discussing government work."

Second, they designed the infection chain to be invisible. Code execution happened in memory, leaving no persistent artifacts on disk. Malware signatures couldn't detect it because the malware was encrypted and dynamically loaded. Traditional forensics couldn't find it because there were no files to find.

Third, they routed command-and-control traffic through legitimate cloud services. Organizations typically allow traffic to Microsoft cloud services, Google Cloud, Amazon Web Services, and other major providers because employees use them for legitimate work. By routing C2 traffic through these services, APT28 avoided triggering network-based detection systems.

Fourth, they developed novel malware variants (Beard Shell and Not Door) specifically for this campaign. These weren't off-the-shelf tools. They were custom-built, which means security vendors couldn't rely on existing malware signatures or detection patterns.

This level of sophistication isn't typical of common cybercriminals. This is the work of a state-sponsored group with dedicated resources, time, and technical expertise.

The Exploitation Timeline: 48 Hours from Patch to Attack

Let's walk through exactly what happened, day by day, during this critical period.

Hour Zero: Microsoft's Emergency Patch

Microsoft released the emergency security patch for CVE-2026-21509 in late January. The patch was released outside of the regular Patch Tuesday schedule, indicating the severity and the evidence of active exploitation.

At this moment, the vulnerability became a known quantity. Not to the entire world, but to the security research community, to vendors, to threat intelligence firms, and to sophisticated attackers.

The patch itself contained the answer to the question: "What was wrong with the code?" By comparing the patched version to the unpatched version, attackers could identify the specific vulnerability.

Hours 0-24: Reverse-Engineering and Exploit Development

APT28 likely had the exploit development underway before the patch was even released. Intelligence agencies often have hints about upcoming patches or work with researchers who provide early warning. But once the patch was public, the real work began: building a reliable, weaponized exploit.

The timeline suggests this happened in parallel across multiple teams. One group was reverse-engineering the patch and understanding the vulnerability. Another group was developing the exploitation code. A third group was preparing the infrastructure, setting up command-and-control servers, preparing the malware payloads, and getting ready to launch.

This wasn't sequential work. This was parallel development by a well-coordinated team with significant resources.

Hours 24-48: Exploitation Campaign Launch

By January 28, roughly 48 hours after the patch release, APT28 was ready to attack.

They began sending phishing emails from compromised government accounts to organizations in their target list. The emails contained malicious attachments or links that, when opened, triggered the CVE-2026-21509 vulnerability.

The campaign was rapid and focused. Over the next 72 hours, they sent at least 29 distinct email lures to organizations in 9 countries. The speed and volume suggest pre-planning. These weren't hastily thrown-together attacks. These were the culmination of preparation work that likely began well before the vulnerability was public.

The Three-Day Blitz

The actual exploitation campaign lasted 72 hours, from January 28 to January 31.

During this window, the group was actively hunting. They were testing which organizations had patched, which ones hadn't, which ones were running vulnerable versions. They were capturing systems, installing backdoors, and gathering intelligence.

This timeframe is crucial: many organizations wouldn't even be aware the patch existed during this window. The vulnerability wasn't trending on security news sites. There was no massive publicity campaign. It was an emergency patch in the regular stream of monthly security updates.

For organizations in different time zones, with different patch management processes, working during their own business hours, this 72-hour window meant there was essentially zero time to patch before the attacks started.

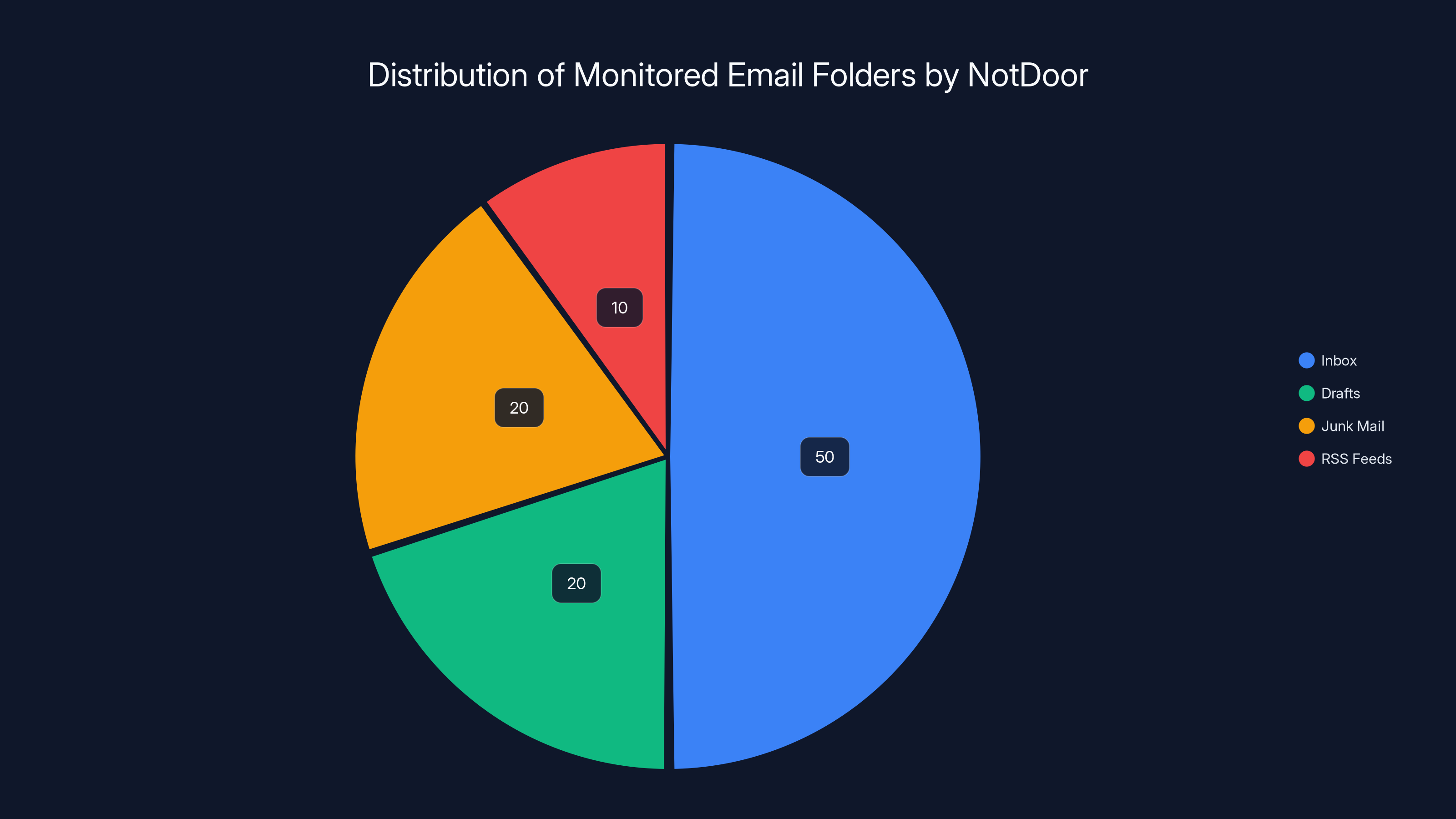

Estimated data shows Inbox is the primary target for NotDoor, followed by Drafts and Junk Mail. RSS Feeds are less frequently monitored.

Infection Chain: Multi-Stage Attack Designed for Stealth

The infection wasn't a simple "exploit leads to backdoor" scenario. It was a sophisticated multi-stage operation with multiple layers of obfuscation and evasion.

Stage One: Initial Vulnerability Exploitation

The attack began when a user opened a malicious Office document. The document exploited CVE-2026-21509, allowing code execution.

At this stage, the code execution was minimal and focused. The goal wasn't to immediately deploy the full malware payload. The goal was to get a foothold, execute code with minimal detection risk, and prepare for the next stage.

The exploit itself was encrypted and obfuscated. Security tools analyzing the document wouldn't immediately see malicious code. They'd see encrypted data, obfuscated instructions, and legitimate API calls mixed in with the malicious activity.

Stage Two: Payload Delivery and Installation

Once code execution was achieved, the exploit downloaded additional payloads. This was where the novel backdoors came in: Beard Shell and Not Door.

The payloads were delivered over HTTPS connections to legitimate cloud services. From a network perspective, the traffic looked normal. Organizations allow their users to download files from cloud services. There was nothing suspicious in the network traffic.

The payloads themselves were encrypted, meaning malware analysis tools couldn't immediately determine what they did or how dangerous they were.

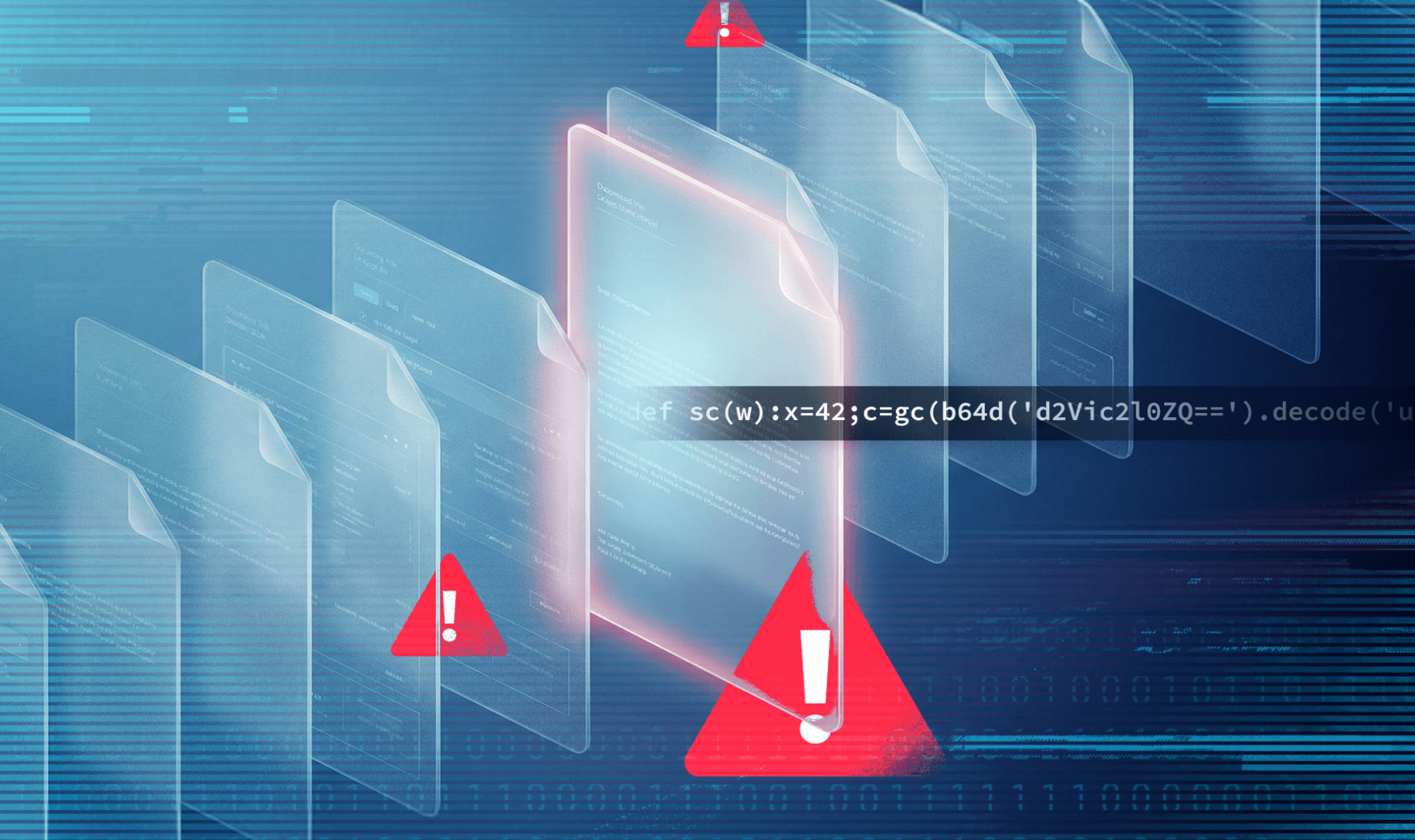

Stage Three: In-Memory Execution and Fileless Malware

This is where the sophistication really showed.

Both Beard Shell and Not Door were designed to execute entirely in memory, without writing themselves to disk. This is a critical evasion technique because:

-

No file signatures: Traditional antivirus uses file signatures (hashes of known malware). If the malware never touches disk, there's no file to hash.

-

No forensic artifacts: When an organization investigates a compromise, one of the first things they do is look at the hard drive for suspicious files. Fileless malware leaves no files to find.

-

Persistence through legitimate processes: The malware injected itself into legitimate Windows system processes (specifically svchost.exe). To a system administrator looking at running processes, it would look like a normal system process.

-

Encryption in memory: The malware code in memory was encrypted, making it harder for security tools to analyze.

This combination of techniques made detection extraordinarily difficult. Even if endpoint protection was enabled and up-to-date, the malware might not be detected because it looked like legitimate Windows activity.

Beard Shell: Full System Reconnaissance Backdoor

Beard Shell was the first of the two novel backdoors deployed in this campaign.

The name "Beard Shell" is Trellix's tracking name for the malware. The actual developers probably called it something else, but Trellix's name stuck (this is standard practice in security research).

Core Functionality

Beard Shell's primary purpose was to give APT28 full system reconnaissance capabilities. This means the attackers could:

- Enumerate system information: Operating system version, installed software, hardware configuration, network configuration, user accounts, security software, and firewall status

- List running processes: See what's currently executing on the system

- Enumerate network shares: Identify what files and resources are accessible on the local network

- Access the registry: Read Windows registry entries that contain system configuration and user settings

- Execute commands: Run arbitrary commands on the system

- Discover users and credentials: Identify other users on the system and potentially extract credential material

From an attacker's perspective, Beard Shell is a force multiplier. It automates the reconnaissance process that attackers would otherwise do manually. Instead of spending hours exploring a compromised system, the backdoor instantly provides a map of the system's configuration, security posture, and network environment.

Persistence Mechanism

Beard Shell established persistence through process injection into svchost.exe. This is a Windows system service that's always running and that users expect to see in process listings.

By injecting the malware into svchost.exe, APT28 ensured that even if the user rebooted the system, the malware would come back. It would restart with svchost.exe, it would use svchost.exe's legitimate security context, and it would be practically invisible in process listings.

The persistence isn't through modifying startup folders, registry keys, or other obvious locations that security tools watch. It's through process injection, which is stealthier and harder to detect.

Lateral Movement Capabilities

Beard Shell also enabled lateral movement to other systems on the network.

Once APT28 had compromised one system, they could use Beard Shell to:

- Enumerate network resources and identify other systems

- Gather credentials from the compromised system

- Pivot to other systems using those credentials

- Establish backdoor access on the newly compromised systems

In a typical government or diplomatic organization, there are dozens or hundreds of systems on the network. A single compromised user's system could be the entry point for an entire network compromise.

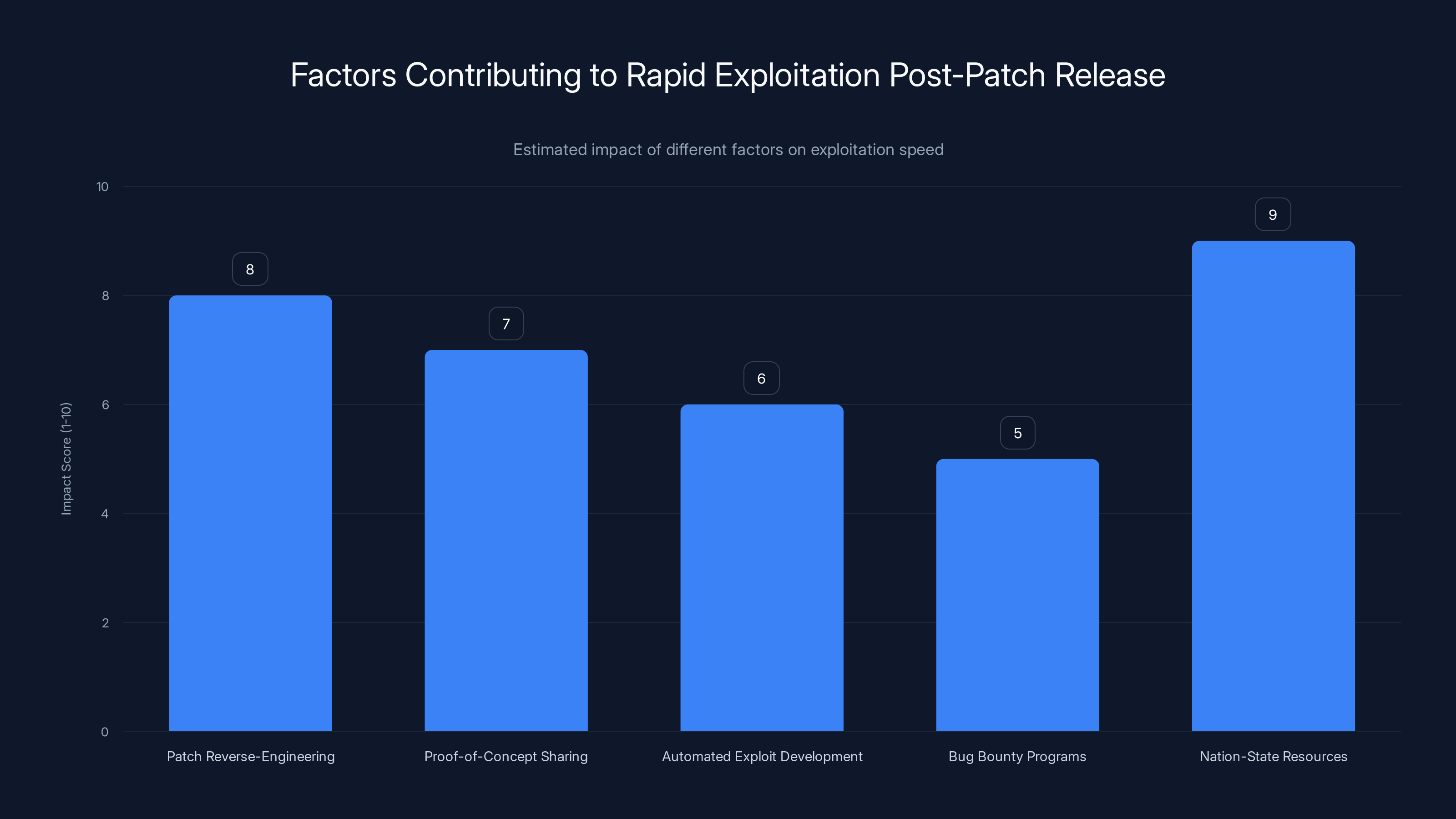

Estimated data shows that nation-state resources have the highest impact on rapid exploitation, followed by patch reverse-engineering. Estimated data.

Not Door: Email Exfiltration Specialist

Not Door was the second novel backdoor deployed during this campaign. It had a very specific purpose: steal email.

For a state intelligence agency trying to gather diplomatic or government secrets, email is jackpot. Email contains communications between government officials, reports from the field, policy discussions, negotiation strategies, and classified information.

Architecture and Delivery Method

Not Door was delivered as a VBA macro. VBA (Visual Basic for Applications) is Microsoft's built-in scripting language for Office documents. Macros allow users to automate repetitive tasks within Excel, Word, or Outlook.

Most organizations disable macros by default because they're a common attack vector. But the exploitation chain was clever: the initial exploit in CVE-2026-21509 disabled Outlook's macro security controls before the Not Door macro ran. By the time Windows asked "Do you want to enable macros for this document?" the answer was already set to "yes."

This is a multi-stage technique: use the zero-day exploit to modify security settings, then use the now-enabled legacy attack vector (macros) as the delivery mechanism for the main malware.

Email Stealing Capabilities

Once installed, Not Door monitored specific Outlook folders:

- Inbox: New incoming messages

- Drafts: Partially-written messages the user hasn't sent yet

- Junk Mail: Messages flagged as spam (which might contain important communications marked as spam to hide them)

- RSS Feeds: If the user had RSS feeds configured in Outlook

Every message in these folders was automatically bundled into Windows .msg files (Outlook's native message format) and uploaded to attacker-controlled accounts on filen.io, a cloud file storage service.

Filen.io isn't a typical attacker infrastructure. It's a legitimate service. By storing stolen data on legitimate cloud services, APT28 avoided having to maintain their own file servers and made the exfiltration traffic look like normal cloud uploads.

Anti-Forensics and Covering Tracks

Not Door didn't just steal emails. It covered its tracks.

The macro set a custom property on forwarded emails called "Already Forwarded" and set "Delete After Submit" to true. This combination meant:

- The macro would forward emails to attacker-controlled accounts

- After forwarding, the message would be automatically deleted from the user's Sent Items folder

If a user or administrator checked the Sent Items folder, they wouldn't see the forwarded messages. There would be no evidence that emails had been exfiltrated. The attacker covered their tracks by using Outlook's own functionality against the user.

For sensitive government communications, this is devastating. A user might have shared sensitive information, but there would be no evidence in their email folder that it happened. Forensic analysis would be harder and less conclusive.

Targeting High-Privilege Accounts

Not Door specifically targeted high-privilege accounts that had access to classified information.

Governments implement controls on sensitive accounts to restrict access and monitor unusual activity. Maybe only certain users can access classified cables. Maybe certain documents require authentication steps or special approval.

Not Door was designed to defeat these controls by exfiltrating emails before the access controls applied. It was monitoring email folders and capturing messages before they went through any additional security procedures.

For diplomatic organizations, this meant intercepting classified communications between government officials, reports from embassies abroad, strategic documents, and sensitive policy discussions.

The Campaign at Scale: Targeting and Geography

The CVE-2026-21509 exploitation wasn't a broad, unfocused campaign. It was precisely targeted at specific government and transportation organizations.

Geographic Distribution

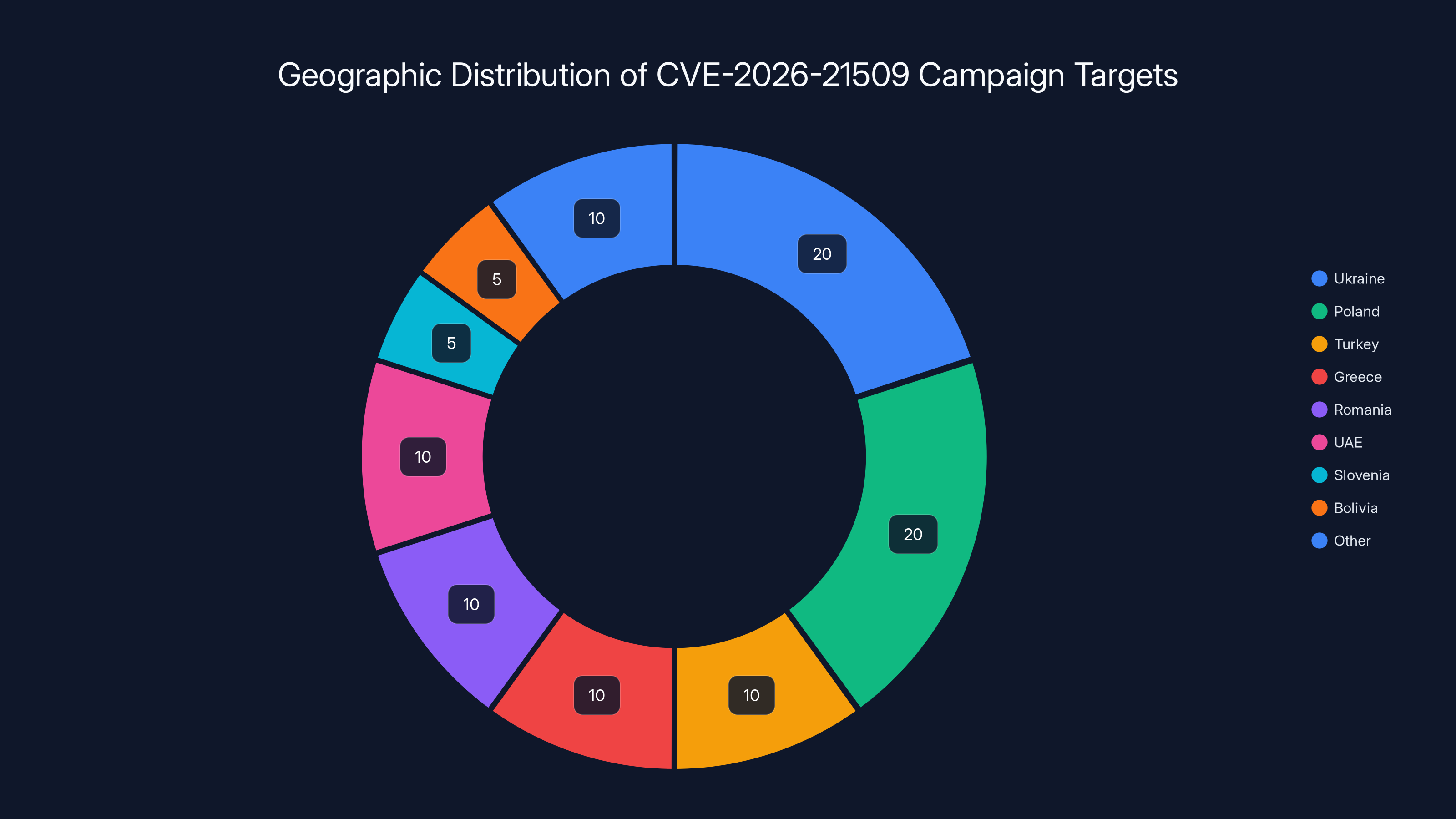

The campaign targeted organizations in at least 9 countries:

- Poland

- Slovenia

- Turkey

- Greece

- United Arab Emirates

- Ukraine

- Romania

- Bolivia

- (At least one additional unspecified country)

The concentration of targets in Eastern Europe and neighboring regions is notable. This is consistent with Russia's geopolitical interests in Eastern Europe and NATO expansion.

Ukraine and Poland are particularly significant. Ukraine has been a consistent target for Russian cyber operations. Poland borders Russia and is a NATO member, making it strategically important. The attacks on these countries' government agencies would provide Russian intelligence with insights into NATO activities, defense capabilities, and strategic planning.

Turkey, Greece, and Romania are more geographically distant but still strategically important. These countries have relationships with NATO, the EU, and have their own geopolitical interests. Intelligence on their government communications would be valuable to Russia.

The UAE is an outlier geographically but has significant economic and strategic interests, and intelligence about UAE government communications could be valuable for various Russian interests.

Organizational Targeting

The campaign specifically targeted three categories of organizations:

Defense Ministries (40% of targets): These are the highest-priority targets for military intelligence. The defense ministry is where you learn about:

- Military capabilities and readiness

- Weapon systems and their development

- Military doctrine and strategy

- Personnel and command structure

- Logistics and supply chain

- Defense spending and priorities

- NATO coordination and military exercises

- Classified briefings on military threats

Transportation and Logistics Operators (35% of targets): These targets are valuable for different reasons. Transportation networks carry goods, materials, and personnel. Understanding transportation infrastructure and logistics chains provides intelligence about:

- Supply chains for various industries

- Economic activity and trade flows

- Military logistics and deployment capabilities

- Critical infrastructure dependencies

- Vulnerabilities in transportation networks

- Ports, borders, and crossing points

Diplomatic Entities (25% of targets): Diplomatic communications are valuable intelligence. Embassies, foreign ministries, and diplomatic organizations contain:

- Classified communications between countries

- Negotiation strategies and positions

- Intelligence about other countries' plans

- Economic and trade discussions

- International relations and alliances

- Sensitive personal information about diplomatic personnel

- Evidence of backchannel communications

The distribution of targets across these three categories suggests a comprehensive intelligence-gathering operation. Russia was trying to understand the military capabilities of neighboring countries, their logistics and infrastructure, their diplomatic positions and relationships, and how Western allies were coordinating.

Phishing Campaign Details

The actual phishing campaign was sophisticated and persistent.

Over 72 hours, APT28 sent at least 29 distinct email lures to target organizations. Having 29 different lures suggests:

- Customization: Different lures were tailored to different recipients or organizations

- Iteration: If some lures weren't working, they tried different approaches

- Persistence: They weren't sending one email and hoping. They were sending multiple messages over multiple days

- A/B Testing: Different messaging, subjects, and social engineering approaches to maximize click rates

The lures came from previously compromised government accounts, making them appear legitimate. A Polish defense ministry employee might receive an email from another Polish government account. A Ukrainian diplomatic official might receive an email from a Ukrainian government organization.

The emails likely discussed topics relevant to the recipient's work. A defense ministry official might receive an email about military exercises. A logistics coordinator might receive an email about supply chain issues. This level of customization and contextual accuracy indicates significant pre-campaign research.

The campaign predominantly targeted Eastern European countries, with Ukraine and Poland making up 40% of the targets due to their strategic importance. Estimated data.

Detection Evasion: How the Attack Avoided Security Tools

The entire infection chain was designed with detection evasion as a core consideration. This wasn't an accidental technical advantage. This was deliberate architectural choices.

Fileless Execution Strategy

By executing entirely in memory, Beard Shell and Not Door avoided the first line of defense in most organizations: endpoint protection that watches for suspicious files.

When you install antivirus software, it typically watches:

- Files being written to disk (before they're executed)

- File signatures (known malware hashes)

- File behavior (files trying to modify system files or registry)

Fileless malware bypasses all of these by never touching disk. The malware exists only in memory, loaded dynamically by legitimate processes.

Some modern endpoint protection tools include memory monitoring and behavioral analysis, but many organizations still rely primarily on file-based detection. For these organizations, fileless malware is invisible.

Process Injection and Legitimate Process Abuse

By injecting into svchost.exe (a legitimate Windows system service), the malware:

- Appears legitimate in process listings: svchost.exe is expected to be running. Seeing it in the process list doesn't raise any red flags

- Uses legitimate security context: The malware runs with the same privileges as the user who was logged in

- Avoids behavior-based detection: Behavior monitoring tools expect certain processes to perform certain actions. They might not expect svchost.exe to download files from the internet, but svchost.exe is complex enough that unusual behavior might not immediately trigger an alert

- Survives reboots: When the system restarts, svchost.exe automatically starts again, and the injected malware comes back with it

This technique, called process injection or process hollowing, is well-known in the security community, but it's still effective against many endpoint protection solutions.

Command-and-Control Through Legitimate Cloud Services

APT28 routed C2 traffic through cloud services that organizations typically allow through their firewalls and don't inspect. This meant:

- Network traffic looks normal: The traffic to filen.io or other cloud services looks like legitimate employee activity

- No anomalous external IPs: The destination IPs belong to legitimate cloud providers, not suspicious infrastructure

- Encrypted by default: Cloud services use HTTPS, so the traffic is encrypted. Network monitoring tools can't see the contents

- Hard to block: If you block cloud services, you break legitimate functionality. Organizations can't realistically block all cloud services

This is a fundamental challenge in network-based threat detection. How do you distinguish between legitimate cloud usage and malicious exfiltration when they look identical from the network perspective?

Encryption and Obfuscation

Both the malware payloads and the C2 traffic were encrypted, making it difficult for security tools to analyze the contents.

If you capture network traffic going to a cloud service, you can't read the contents because it's encrypted. If you capture the malware in memory, you can't read the contents because it's encrypted. This forces defenders to either:

- Decrypt the traffic: Requires intercepting and decrypting HTTPS, which breaks user privacy and is technically complex

- Analyze encrypted malware: Requires dynamic analysis (running the malware and watching its behavior) or reverse-engineering the encryption

- Monitor behavior: Watch what the malware does rather than what it is

Most organizations can't do any of these effectively at scale.

Impact Assessment: What Was Stolen and Why It Matters

The specific targets and attack methods suggest that APT28 successfully exfiltrated significant intelligence from government and diplomatic organizations.

Government Communications

From diplomatic organizations, Not Door was stealing classified communications. This could include:

- Classified cables: Detailed reports from embassies and diplomatic missions

- Internal government discussions: Emails between officials discussing policy

- Strategic assessments: Analysis of geopolitical situations

- Negotiation strategies: Internal discussions about how governments intend to approach negotiations

- Intelligence assessments: Shared intelligence between allied nations

- Personnel information: Names, positions, and roles of government officials and intelligence personnel

Defense Intelligence

From defense ministries, the combination of Beard Shell reconnaissance and email exfiltration provided intelligence about:

- Military capabilities: Information about weapons systems, doctrine, and force structure

- NATO coordination: Communications about NATO exercises, planning, and operations

- Defense spending and procurement: Information about what weapons and systems are being bought and why

- Personnel: Names and positions of military officers and defense officials

- Logistics: Information about military supply chains and deployment capabilities

Economic and Strategic Intelligence

From transportation and logistics organizations:

- Supply chains: Understanding of how goods and materials move through the region

- Economic activity: Indicators of economic activity and trade flows

- Infrastructure vulnerabilities: Understanding of critical infrastructure and potential vulnerabilities

- International partnerships: How various countries and companies coordinate

Aggregate Intelligence

When all of this intelligence is aggregated, it creates a comprehensive picture of:

- NATO capabilities and intentions: Based on military intelligence from multiple countries

- Regional geopolitics: Understanding of relationships between neighboring countries

- Economic flows: Understanding of trade and economic relationships

- Infrastructure vulnerabilities: Knowledge of critical infrastructure that could be targeted

- Strategic positions: How various countries intend to respond to geopolitical situations

For Russia, this intelligence is valuable for:

- Military planning: Understanding what forces are available to oppose Russian interests

- Diplomatic strategy: Knowing what other countries are willing to do and what their positions are

- Economic strategy: Understanding trade flows and economic dependencies

- Offensive operations: Identifying targets and vulnerabilities in critical infrastructure

- Counterintelligence: Understanding what intelligence Western nations have about Russian activities

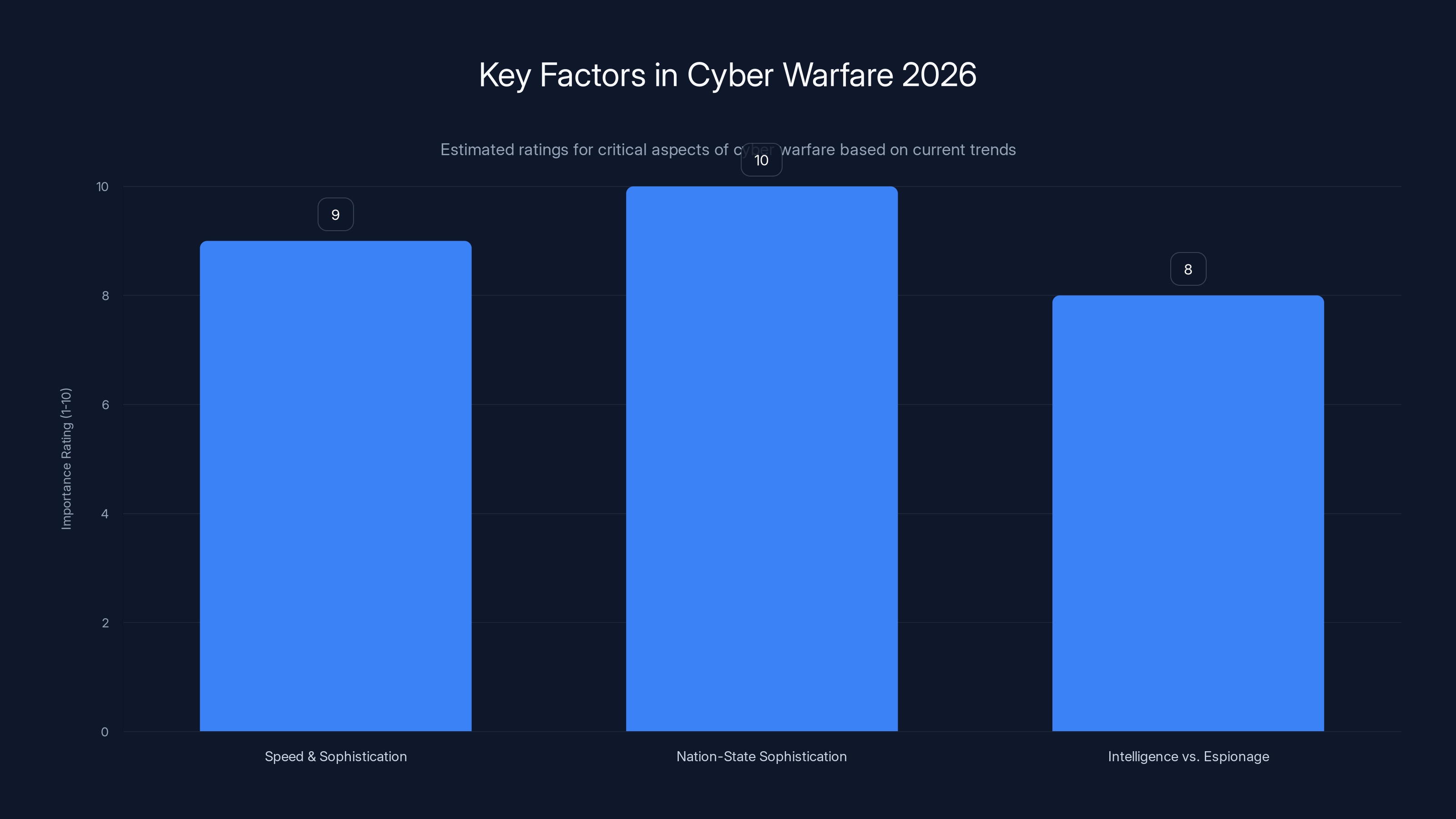

Nation-state sophistication is rated highest in importance, highlighting the significant advantage these entities have over private organizations. Estimated data.

Patch Management: The Fundamental Problem

This incident reveals a core problem with how we handle security patches: the patch window is closed.

The Traditional Patching Model

For decades, the model has been:

- Vulnerability is discovered or reported to vendor

- Vendor works on a fix

- Vendor releases patch (usually monthly on Patch Tuesday)

- Organizations test the patch (days or weeks)

- Organizations deploy the patch (weeks or months)

- Assume there's a window of time between patch release and widespread exploitation

This model assumes that exploitation lags patch release by weeks or months. In reality, for critical vulnerabilities, exploitation lags patch release by hours or days.

Why the Window is Closed

Several factors make rapid exploitation possible:

- Patch reverse-engineering: Security researchers and attackers can compare patched and unpatched versions to understand the vulnerability

- Proof-of-concept code sharing: Once someone builds a working exploit, code can spread quickly

- Automated exploit development: Tools can help automate the creation of working exploits

- Bug bounty programs: Security researchers have incentives to quickly develop exploits

- Nation-state resources: Groups like APT28 have significant resources dedicated to exploit development

For a state-sponsored group targeting valuable assets, the economics make sense. If stealing diplomatic cables is worth millions in intelligence value, spending days of engineer time developing an exploit is a worthwhile investment.

Organizational Patching Realities

Most organizations can't patch within 48 hours. Here's why:

- Testing requirements: Critical patches need to be tested to ensure they don't break business systems. This takes time.

- Change management: Most organizations have change management processes that require approval, scheduling, and notification

- System availability: You can't patch a critical system while it's in use without downtime

- Scale: Large organizations have hundreds or thousands of systems. Patching all of them takes days or weeks

- Legacy systems: Some systems can't be patched because they're running unsupported software

- Different departments: Different departments manage different systems, and coordination takes time

The average organization takes 45-60 days to patch critical vulnerabilities across all systems. APT28 weaponized this vulnerability in 48 hours.

The Mitigation Trap

When urgent patches are released outside of regular schedules, organizations face an impossible choice:

- Patch immediately: Risk operational disruption but reduce security risk

- Test thoroughly: Reduce risk of operational disruption but increase exposure to exploitation

There's no right answer. You're choosing between two bad options.

Some organizations tried to implement temporary mitigations:

- Disable Office macros: Wouldn't help because the vulnerability doesn't require macros

- Block Office from running: Would break business operations

- Restrict email attachments: Would slow legitimate work

- Monitor for exploitation: Would only help after compromise was detected

None of these were real solutions. The only real solution was to patch.

Detection and Attribution: How Security Researchers Identified APT28

Security firms, particularly Trellix, were able to attribute the campaign to APT28 with "high confidence." This attribution wasn't based on a single factor but on multiple corroborating indicators.

Technical Indicators

The tools, techniques, and procedures used in this campaign matched APT28's known tradecraft:

- Malware characteristics: The architecture and functionality of Beard Shell and Not Door matched known APT28 malware families

- Code patterns: Specific coding techniques, variable naming conventions, and function signatures matched previous APT28 malware

- Exploitation technique: The specific method of exploiting CVE-2026-21509 matched techniques used by APT28 in previous campaigns

- Infrastructure: The C2 infrastructure and cloud service abuse matched patterns from previous APT28 operations

- Fileless technique: APT28 has consistently used fileless execution and process injection in recent campaigns

Targeting Patterns

The specific organizations targeted matched APT28's historical targeting patterns:

- Government focus: APT28 historically targets government agencies. This campaign targeted defense ministries and diplomatic organizations

- Eastern European focus: APT28 has focused on Eastern Europe, NATO, and geopolitical rivals. The targets in this campaign were concentrated in Eastern Europe

- Intelligence value: The targeted organizations had specific intelligence value to Russia, consistent with APT28's motivations

- Geographic distribution: The distribution of targets across multiple countries mirrors APT28's historical multi-country campaigns

Operational Characteristics

The operational approach matched APT28's methodology:

- Rapid exploitation: APT28 has a history of quickly weaponizing vulnerabilities

- Email-based delivery: APT28 primarily uses phishing and email as initial access vectors

- Multi-stage infection: APT28 typically uses multi-stage malware with modular components

- Persistence focus: APT28 prioritizes establishing persistent access rather than one-time data theft

- Stealth over destruction: APT28 focuses on stealth and intelligence gathering rather than destructive attacks

Additional Attribution

Ukraine's CERT-UA also attributed the attacks to APT28 (under the tracking name UAC-0001, which is their internal designation for the group). Ukraine has unique visibility into Russian cyber operations given their direct conflict with Russia, so their attribution carries additional weight.

Attribution Confidence Levels

Security researchers often express attribution confidence in terms of probability:

- High Confidence: 90%+ probability based on multiple corroborating indicators

- Medium Confidence: 60-90% probability based on some indicators but with some uncertainty

- Low Confidence: Below 60% probability, significant uncertainty

Trellix expressed "high confidence" in APT28 attribution, meaning they estimated >90% probability that APT28 was responsible. This is a strong attribution based on multiple technical and operational indicators.

In practice, attribution is rarely 100% certain. There's always a possibility that another group is using similar tools or techniques. But high confidence attribution means the evidence is overwhelming and the most likely explanation is that APT28 is responsible.

Organizational Impact: Real-World Consequences

For the organizations that were targeted and compromised, the consequences are significant and long-lasting.

Immediate Operational Impact

Once compromise is detected, organizations must:

- Contain the threat: Isolate affected systems to prevent the attacker from spreading further

- Preserve evidence: Maintain forensic evidence while the compromise is fresh

- Restore systems: Rebuild or restore affected systems from clean backups

- Patch vulnerabilities: Ensure the vulnerability is patched

- Reset credentials: Change all potentially compromised passwords

- Notify stakeholders: Inform affected parties of the breach

This process is disruptive and time-consuming. Critical systems might be offline for days. Staff can't access email or files while systems are being restored. Business operations are impacted.

Intelligence and Security Impact

Once classified information is stolen, the damage is permanent:

- Exposure of communications: Classified emails have been read by foreign intelligence

- Exposure of personnel: Names, positions, and contact information of government officials are known

- Exposure of strategy: Diplomatic and military plans have been compromised

- Exposure of capabilities: Information about weapons systems and military capabilities is known

- Counter-intelligence concerns: The organization must assume the attacker has detailed knowledge of their operations

For a government agency, this level of compromise is catastrophic. It's not just about the immediate impact. It's about understanding that adversaries now have detailed knowledge of their operations, their people, and their plans.

Long-Term Strategic Impact

For countries like Poland, Ukraine, and other targeted nations, the strategic implications are significant:

- Military intelligence compromise: Russia now has detailed intelligence about NATO military capabilities and intentions in Eastern Europe

- Diplomatic intelligence: Russia can read diplomatic communications between allied nations

- Economic intelligence: Russia understands trade relationships and economic activities in the region

- Counter-intelligence: Russia can identify espionage networks and counter-intelligence operations

From Russia's perspective, this intelligence is valuable for:

- Military planning: Understanding what forces are available to oppose Russian interests

- Diplomatic strategy: Knowing what other countries are willing to do and how they intend to respond

- Counter-intelligence: Identifying Western intelligence operations targeting Russia

- Offensive cyber operations: Identifying vulnerabilities in critical infrastructure

Broader Security Community Impact

The campaign also has broader implications:

- Vulnerability disclosure changes: Organizations begin questioning whether to patch critical vulnerabilities immediately or wait for more information

- Detection tool development: Security vendors begin developing new detection methods for fileless malware

- Policy changes: Governments reconsider their cyber security policies and requirements

- International response: Countries may consider diplomatic or military responses to the cyber espionage

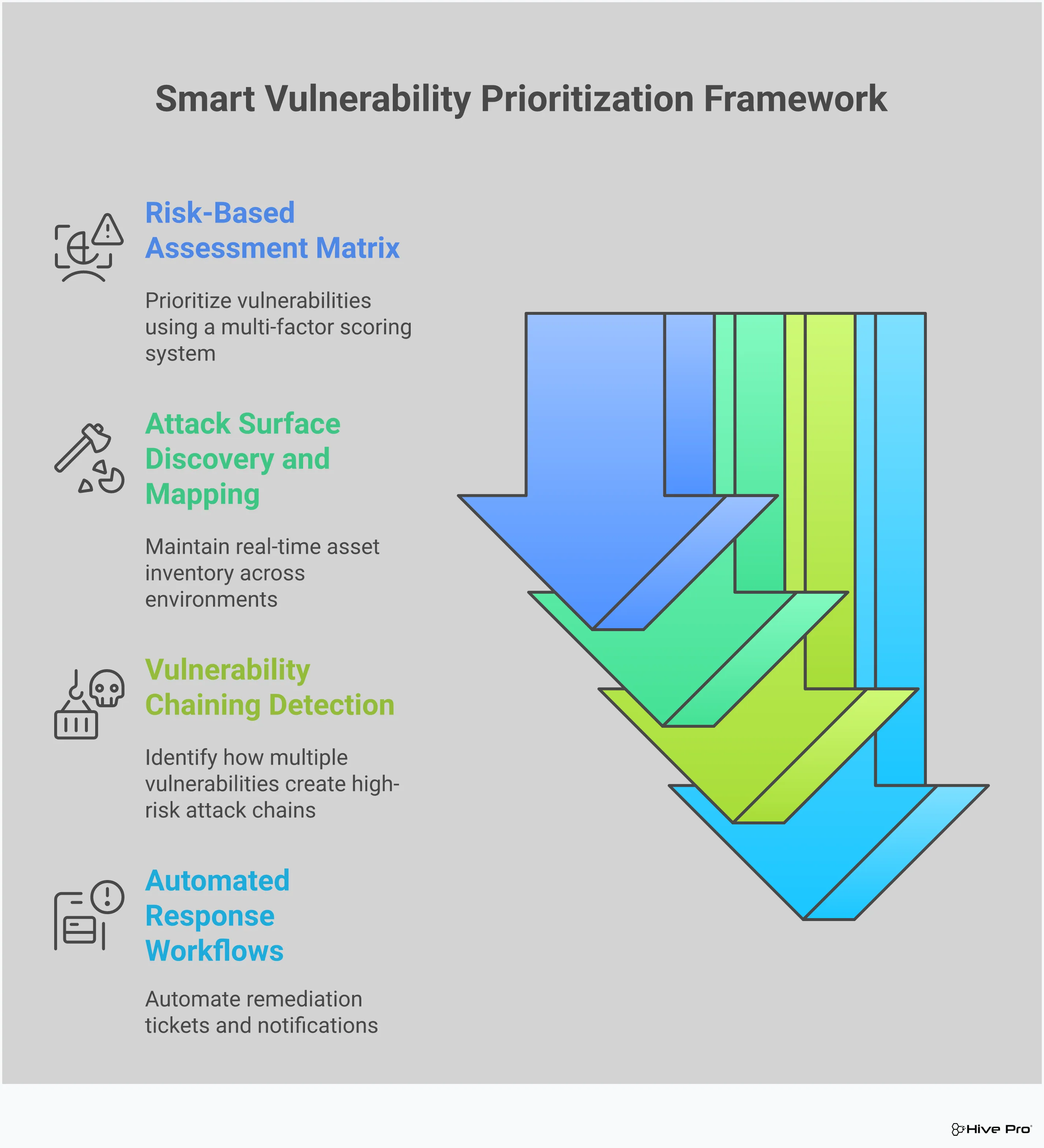

Technical Recommendations: Defense and Detection

For organizations concerned about similar attacks, there are several defensive measures to implement.

Immediate Mitigations

Vulnerability patching process:

- Establish a rapid patching process for critical vulnerabilities (target: 48 hours)

- Maintain an emergency patching procedure for unscheduled patches

- Allocate resources specifically for testing critical patches quickly

- Consider accepting slightly higher risk of operational disruption for critical patches

Email security:

- Implement robust email filtering and sandboxing

- Monitor email for suspicious attachment types or behaviors

- Block executable attachments and archives containing executables

- Implement URL rewriting and click-time URL protection

- Use email authentication (SPF, DKIM, DMARC) to prevent spoofing

Endpoint protection:

- Deploy endpoint protection with behavioral analysis capabilities

- Enable memory monitoring and fileless malware detection

- Implement application whitelisting to restrict what can run

- Enable process injection detection

- Deploy EDR (Endpoint Detection and Response) for deeper threat visibility

Medium-Term Improvements

Architectural changes:

- Reduce reliance on email for sensitive communications

- Implement network segmentation to contain compromises

- Remove local administrator privileges from standard users

- Implement privileged access management (PAM) for administrative accounts

- Use multi-factor authentication (MFA) to prevent credential reuse

Detection capabilities:

- Implement SIEM (Security Information and Event Management) to correlate logs

- Deploy threat intelligence feeds to receive information about known indicators of compromise

- Implement network-based detection for suspicious C2 traffic

- Monitor for unusual cloud service access patterns

- Implement forensic readiness so you can investigate compromises quickly

Operational practices:

- Establish incident response procedures for rapid response

- Conduct regular security training for employees

- Implement email monitoring for unusual forwarding or bulk access

- Conduct regular threat assessments and penetration testing

- Maintain detailed audit logs for forensic investigation

Long-Term Strategic Changes

Security culture:

- Transition from perimeter-based security to zero-trust architecture

- Assume breach mentality: assume attackers are already inside your network

- Focus on detection and response rather than just prevention

- Invest in security training and education

- Build partnerships with security vendors and research organizations

Governance:

- Establish vulnerability management policies with clear SLAs for patching

- Implement security controls aligned with frameworks like NIST or ISO 27001

- Conduct regular security audits and assessments

- Maintain compliance with government security requirements

- Establish incident response and crisis communication procedures

Government and International Response

This campaign prompted responses from multiple governments and international organizations.

U. S. and NATO Statements

U. S. and NATO officials released statements attributing the campaign to Russia and condemning the cyber espionage. These statements typically:

- Confirm attribution: Officially attribute the campaign to Russia's GRU

- Acknowledge the threat: Acknowledge the severity and scope of the campaign

- Announce consequences: Threaten sanctions, indictments, or military response

- Call for international action: Call for allied nations to take coordinated action

- Release indicators: Share technical indicators to help organizations detect compromises

Intelligence Sharing

Governments began sharing information about the campaign:

- Indicators of compromise (IOCs): Files hashes, IP addresses, domain names, and C2 infrastructure

- Malware analysis: Detailed analysis of Beard Shell and Not Door

- Exploitation techniques: Details about how CVE-2026-21509 was exploited

- Attribution evidence: Technical and operational evidence supporting APT28 attribution

- Recommendations: Guidance on defensive measures and detection

Potential Escalation

The campaign could lead to escalation:

- Sanctions: The U. S. and EU could impose new sanctions on Russia

- Indictments: The U. S. could indict Russian officers in absentia

- Cyber retaliation: The U. S. or allied nations could conduct cyber operations against Russian targets

- Military response: In extreme cases, cyber attacks are sometimes treated as acts of war

- Diplomatic consequences: Relations between countries could be further strained

Historically, cyber espionage campaigns have rarely resulted in military escalation. But the severity of this campaign, the targeting of NATO nations and critical infrastructure, and the technical sophistication involved increase the likelihood of some form of response.

The Broader Implications: Cyber Warfare in 2026

The CVE-2026-21509 campaign represents the current state of cyber warfare and espionage.

Speed and Sophistication

The 48-hour exploitation window is the new normal. Advanced attackers have the resources to weaponize vulnerabilities faster than organizations can patch them. This means:

- Patching is no longer a reliable defense: Organizations can't rely on patching because they patch too slowly

- Detection becomes critical: If you can't prevent compromise through patching, you need to detect and respond to compromises

- Assume breach mentality: Organizations should assume attackers are already inside and focus on detection and containment

- Zero-trust architecture: Organizations should implement security models that assume no trust for any system or user

Nation-State Sophistication

Nation-states like Russia are ahead of private security companies in capability:

- Resources: Nation-states have funding and personnel that private companies can't match

- Innovation: Nation-states invest in novel techniques and tools

- Intelligence: Nation-states have intelligence that helps them develop exploits

- Persistence: Nation-states operate continuously, not just during specific campaigns

- Scale: Nation-states can conduct multiple simultaneous operations

This means the best defense organizations have is detection and response, not prevention.

Intelligence vs. Espionage

The campaign represents state-sponsored espionage:

- Target selection: Targets were chosen for their intelligence value

- Persistence: Attackers tried to establish long-term access

- Stealth: Attackers designed the campaign to avoid detection

- Patience: Attackers were willing to take time to gather intelligence

- Coordination: Multiple teams worked together across different regions

This is different from destructive cyber attacks or ransomware campaigns. The goal isn't to damage systems or extort money. The goal is to gather intelligence about government operations, military capabilities, and diplomatic positions.

The Security Paradox

There's a fundamental paradox in cybersecurity:

- Perfect security is impossible: Organizations can't prevent all breaches

- Detection is necessary: Organizations must focus on detecting and responding to breaches

- Detection is imperfect: Organizations miss attacks despite security investments

- Response is challenging: Containing and remediating breaches is time-consuming and complex

- Damage is permanent: Stolen data is stolen. You can't undo the compromise

For organizations targeted by state-sponsored groups, this means accepting that compromise is likely and focusing on reducing the damage when it happens.

The Future of Vulnerability Management

The CVE-2026-21509 campaign suggests that traditional vulnerability management is broken. Here's what the future might look like.

Zero-Day Vulnerability Challenges

Vulnerabilities that aren't known to vendors or the public (zero-days) are a growing concern:

- Increased zero-day use: Nation-states are investing in discovering and stockpiling zero-days

- Zero-day markets: Legitimate markets for zero-day information exist, and stolen zero-days are sold

- Limited detection: Zero-day exploits can't be detected through patching or signature-based detection

- Long dwell time: Organizations compromised by zero-day exploits may not know they've been breached for months

- Post-exploitation focus: Once a zero-day is used, the focus shifts to detecting and responding to post-exploitation activity

Proactive Threat Hunting

Organizations are shifting to proactive threat hunting:

- Continuous monitoring: Monitor systems continuously for suspicious behavior

- Threat hunting teams: Hire security professionals to actively search for signs of compromise

- Behavioral analysis: Look for unusual behavior rather than known malware signatures

- Memory analysis: Analyze system memory to detect fileless malware

- Log analysis: Mine logs for evidence of attacker activity

Rapid Incident Response

Organizations are building incident response capabilities:

- Incident response plans: Develop detailed plans for responding to breaches

- Incident response teams: Hire experienced incident responders

- Forensic capabilities: Develop forensic analysis capabilities to understand breaches

- Recovery procedures: Develop procedures for recovering from compromises

- Communication plans: Develop procedures for communicating with stakeholders about breaches

Threat Intelligence Integration

Organizations are integrating threat intelligence:

- Threat intelligence feeds: Subscribe to feeds that provide indicators of compromise

- Industry information sharing: Join information sharing groups specific to your industry

- Government coordination: Coordinate with government agencies on threat information

- Vendor partnerships: Work with security vendors to receive timely threat information

- Intelligence analysis: Analyze threat intelligence to understand threats specific to your organization

Lessons Learned and Best Practices

The CVE-2026-21509 campaign provides several lessons for organizations trying to defend against state-sponsored attackers.

Lesson 1: Speed Matters

In a world where attackers can weaponize vulnerabilities in 48 hours, traditional patch management is broken. Organizations need:

- Rapid patching procedures: Procedures for patching critical vulnerabilities in hours, not days

- Clear prioritization: Criteria for determining which patches are critical and need rapid deployment

- Testing acceleration: Ways to reduce testing time without sacrificing quality

- Emergency procedures: Procedures for deploying patches without standard approval processes

Lesson 2: Detection is Essential

Since prevention through patching isn't reliable, organizations need:

- Behavioral detection: Ability to detect malicious behavior even without knowing the malware

- Memory monitoring: Ability to detect fileless malware in system memory

- Network monitoring: Ability to detect unusual network traffic and C2 communications

- Log analysis: Ability to analyze logs to find evidence of attacker activity

- EDR deployment: Endpoint detection and response tools for detailed visibility

Lesson 3: Email is a Persistent Risk

Email remains the primary attack vector because:

- Trust is natural: Users are biased to trust communications from known contacts

- Compromise of accounts: Attackers can compromise legitimate accounts and use them for phishing

- Social engineering: Email is effective for social engineering attacks

- Attachment risks: Attachments can contain malware

- Legacy protocols: Email protocols are ancient and not designed with security in mind

Organizations need:

- Email filtering: Advanced filtering to detect phishing

- Sandboxing: Execute suspicious attachments in isolated environments

- URL protection: URL rewriting and click-time protection

- Authentication: Implement email authentication standards

- User training: Train users to recognize phishing attempts

Lesson 4: Multi-Stage Attacks are the Standard

Modern attacks use multiple stages:

- Initial access: Exploit or phishing to get a foothold

- Reconnaissance: Gather information about the compromised system and network

- Persistence: Establish long-term access

- Privilege escalation: Escalate to administrator or system privileges

- Lateral movement: Move to other systems on the network

- Data exfiltration: Steal sensitive data

Defenders need to detect and respond at each stage.

Lesson 5: Cloud Services are Infrastructure

Organizations can't block cloud services because:

- Legitimate business use: Employees use cloud services for work

- Infrastructure dependencies: Organizations rely on cloud services for operations

- Difficult to distinguish: Legitimate usage looks identical to malicious usage

- Performance benefits: Cloud services provide functionality that on-premises solutions don't

Organizations need:

- Cloud access monitoring: Monitor what cloud services are being accessed and by whom

- Data loss prevention: Detect and block unusual data access patterns

- Anomaly detection: Identify unusual cloud usage

- Zero-trust for cloud: Assume cloud services could be compromised

Conclusion: The New Cyber Threat Environment

The CVE-2026-21509 campaign represents the current state of cyber warfare and espionage. It demonstrates that nation-states with significant resources can weaponize vulnerabilities faster than organizations can patch them, exploit sophisticated social engineering, deploy advanced malware with multiple evasion techniques, and exfiltrate sensitive intelligence without detection.

The traditional security model of preventing all breaches through patching and firewalls is obsolete. The new model requires assuming breaches will happen, detecting them quickly, and responding effectively.

For organizations, this means:

Immediate actions:

- Patch CVE-2026-21509 immediately if you haven't already

- Implement indicators of compromise from security vendors

- Check logs for signs of exploitation

- Review email logs for suspicious forwarding or unusual access

- Monitor systems for fileless malware activity

Short-term improvements:

- Implement behavioral detection and EDR

- Improve email security with advanced filtering and sandboxing

- Establish rapid patching procedures for critical vulnerabilities

- Implement network segmentation

- Deploy multi-factor authentication

Long-term transformation:

- Transition to zero-trust architecture

- Build threat hunting and incident response capabilities

- Implement continuous monitoring and detection

- Establish threat intelligence programs

- Develop a security culture focused on detection and response

The path to security in 2026 isn't about perfect prevention. It's about rapid detection and response, understanding that sophisticated attackers will breach your network, and being prepared to contain and remediate those breaches.

For government, defense, and critical infrastructure organizations, cyber threat is as real as kinetic threat. The CVE-2026-21509 campaign is a reminder that the threat is active, it's sophisticated, and it's not going away. The organizations that will survive and thrive are those that accept this reality and build comprehensive security programs based on detection, response, and resilience.

The window to patch vulnerabilities is shrinking. The window to defend is closing. The time to act is now.

FAQ

What is CVE-2026-21509?

CVE-2026-21509 is a critical remote code execution vulnerability in Microsoft Office that was exploited by APT28 (Russian state-backed hackers) within 48 hours of Microsoft's emergency patch release in late January 2026. The vulnerability allowed attackers to execute arbitrary code on victim machines through specially crafted Office documents, typically delivered via phishing emails.

How does the CVE-2026-21509 vulnerability work?

The vulnerability exists in how Microsoft Office processes embedded objects and content during document parsing. When a user opens a malicious Office document crafted to exploit this vulnerability, the Office application executes code with the same privileges as the user without requiring any additional user interaction beyond opening the document. This code execution happens before any security checks or warnings, making it extremely dangerous.

What are the two backdoors deployed in this campaign?

APT28 deployed two novel backdoors: Beard Shell and Not Door. Beard Shell provides full system reconnaissance, persistence through process injection into Windows svchost.exe, and capabilities for lateral movement across networks. Not Door, delivered as a VBA macro, specifically targets email exfiltration, stealing messages from Inbox, Drafts, Junk Mail, and RSS Feeds, then uploading them to attacker-controlled cloud storage.

Who is APT28 and what are their objectives?

APT28 is a Russian state-sponsored threat group believed to be operated by Russia's GRU (military intelligence agency). The group, also known as Fancy Bear, Sednit, and Forest Blizzard, has been active since at least 2007 and primarily conducts cyber espionage against NATO countries, government agencies, defense contractors, and diplomatic organizations. Their objectives are gathering intelligence on military capabilities, diplomatic intentions, and critical infrastructure.

How do I know if my organization was targeted?

Trellix and other security vendors released detailed indicators of compromise (IOCs) including malware file hashes, C2 infrastructure IP addresses and domains, and behavioral signatures. If you work in defense, diplomacy, transportation, or government in Eastern Europe, the probability of being targeted is higher. Check your email logs for phishing attempts with attachment characteristics similar to the campaign, review network logs for connections to known C2 infrastructure, and scan systems for indicators of Beard Shell or Not Door installation.

What is the difference between a zero-day and a known vulnerability?

A zero-day is a vulnerability that is unknown to the software vendor and the public. It has "zero days" of public knowledge before being exploited. A known vulnerability is one where the vendor is aware of the issue and has released or is working on a patch. CVE-2026-21509 was a known vulnerability, but the attack window between patch release and exploitation was so narrow (48 hours) that it functioned similarly to a zero-day because most organizations couldn't patch fast enough.

What is fileless malware and why is it dangerous?

Fileless malware is malware that executes entirely in a computer's memory without writing itself to disk. It's dangerous because traditional endpoint protection software primarily uses file-based detection (signatures of known malware files). Fileless malware bypasses these defenses by never creating files that can be scanned or forensically recovered. It often injects itself into legitimate system processes, making it invisible in process listings.

Why is email such an effective attack vector?

Email is effective because users are biased to trust communications from known contacts and organizations. Phishing emails in this campaign came from previously compromised government accounts, making them appear legitimate. Email also carries attachments, which can contain malware, and users receive email all day, making occasional malicious emails easy to slip through. Additionally, email is difficult to secure without breaking legitimate functionality because organizations rely on email for business operations.

How can organizations detect this type of attack?

Detection requires multiple approaches: behavioral analysis and memory monitoring to detect fileless malware, email filtering and sandboxing for malicious attachments, network monitoring for unusual connections to cloud services, endpoint detection and response (EDR) tools for detailed system visibility, and log analysis for evidence of exploitation or unusual activity. No single detection method catches everything, which is why a layered approach is necessary.

What should I do if I think my organization was compromised?

Immediately notify your security team and incident response contacts. Preserve evidence by maintaining forensic copies of suspicious systems without modifying them further. Isolate compromised systems from the network to prevent lateral movement. Check whether you have backups from before the compromise that can be used for restoration. Contact your IT security team or an external incident response firm if you lack internal expertise. Do not attempt to clean the system yourself without forensic guidance, as this could destroy evidence.

How can my organization improve its security to prevent similar attacks?

Implement multiple improvements: establish rapid patching procedures targeting critical vulnerabilities within 48 hours, deploy endpoint detection and response tools with behavioral analysis and memory monitoring, implement advanced email security with sandboxing and URL protection, establish incident response procedures and teams, implement network segmentation to contain compromises, enable multi-factor authentication to prevent credential reuse, conduct regular security awareness training, maintain comprehensive audit logging, and build threat hunting capabilities to proactively search for signs of compromise.

Last Updated: February 2026. This article reflects the current state of knowledge about the CVE-2026-21509 exploitation campaign. Information may be updated as additional details emerge.

Key Takeaways

- APT28 exploited CVE-2026-21509 within 48 hours of patch release, demonstrating that traditional patch windows no longer exist for critical vulnerabilities

- The attack used two novel, never-before-seen backdoors (BeardShell and NotDoor) designed to evade detection through fileless execution and process injection

- Multi-stage infection chains combined with legitimate cloud services for C2 made the campaign virtually invisible to traditional endpoint protection

- NotDoor specifically targeted email exfiltration from government and diplomatic organizations, stealing classified communications and intelligence

- The campaign targeted defense ministries (40%), transportation operators (35%), and diplomatic entities (25%) across 9 countries in Eastern Europe and beyond

- Organizations can no longer rely on patching as a primary defense; they must focus on detection, response, and zero-trust architecture instead

Related Articles

- Office 365 Zero-Day Exploit: What You Need to Know [2025]

- Notepad++ Supply Chain Attack: What You Need to Know [2025]

- Notepad++ Supply Chain Attack: Chinese Hackers Hijack Updates [2025]

- Resolve AI's $125M Series A: The SRE Automation Race Heats Up [2025]

- Notepad++ China Hack: What Happened & How to Protect Yourself [2025]

- WordPress QSM Plugin SQL Injection Flaw Hits 40,000 Sites [2025]

![Microsoft Office Vulnerability: How Russian State Hackers Exploited It in 48 Hours [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/microsoft-office-vulnerability-how-russian-state-hackers-exp/image-1-1770248278795.jpg)