Introduction: The Hidden Risk in Your Text Messages

Your phone buzzes. A text message arrives with a link promising to sign you into your favorite service. You click it without thinking twice. In that moment, you've likely handed over access to your personal information to a system so fundamentally broken that security researchers are calling it a widespread crisis affecting millions of people worldwide.

This isn't a theoretical problem buried in academic papers. Real services with millions of active users are doing this right now. We're talking about major platforms that people trust daily, companies that should know better. Yet they're sending authentication links through SMS in ways that expose social security numbers, bank account information, credit scores, and dates of birth to anyone willing to spend five minutes trying to guess the right URL.

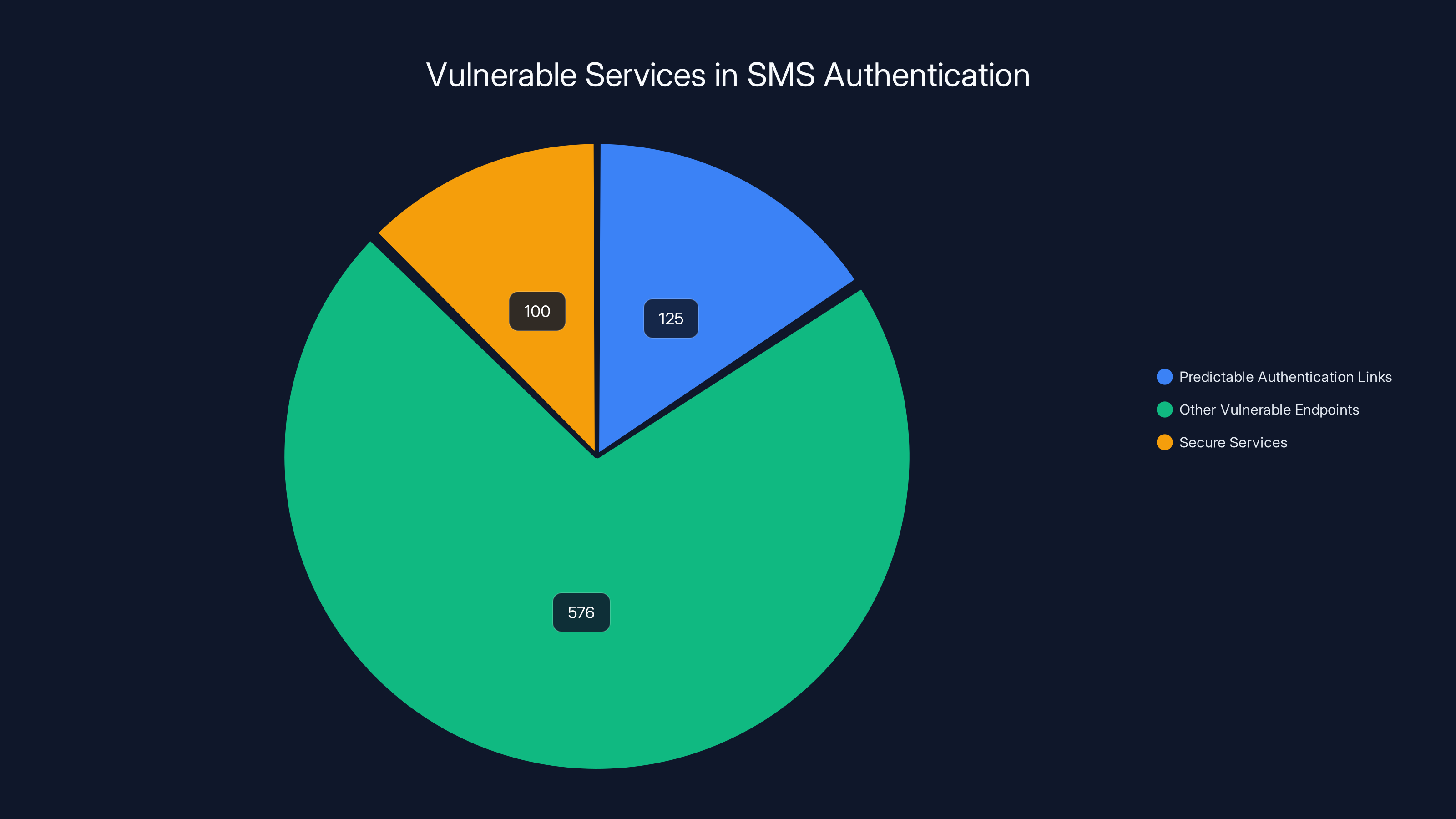

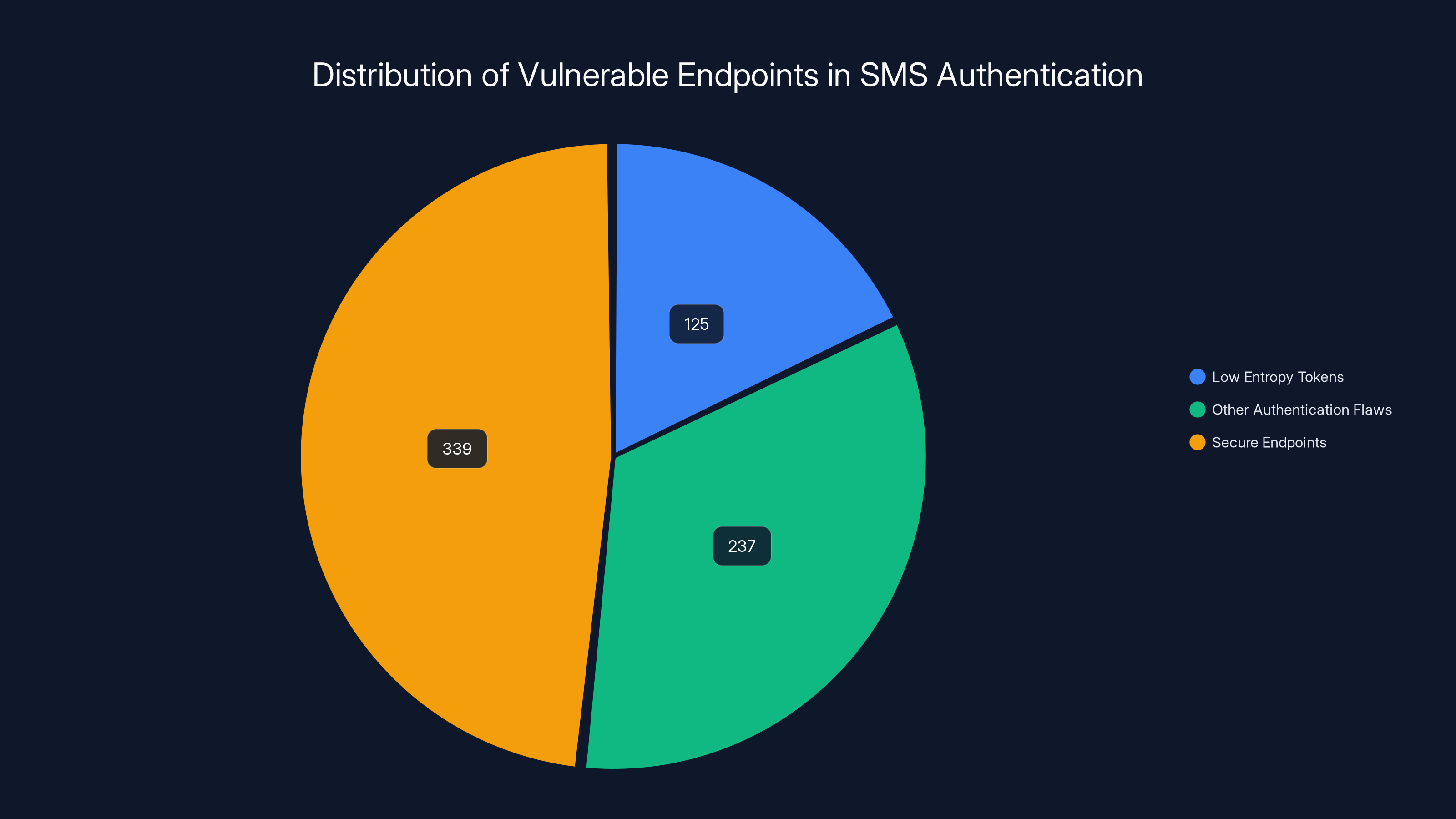

The scale of this vulnerability became clear in recently published research that examined over 33 million text messages sent to more than 30,000 phone numbers. The findings were staggering: researchers identified 701 endpoints from 177 different services that were actively putting users at risk. Of those, 125 services had authentication links so predictable that attackers could enumerate valid accounts by simply incrementing the security token. This isn't a bug in one service. It's a fundamental architectural flaw replicated across the entire industry.

What makes this particularly insidious is that the practice is popular precisely because it seems simple and user-friendly. No complicated passwords to remember. No authenticator apps to set up. Just a link in a text message. But that simplicity masks a catastrophic security failure that leaves you vulnerable to account takeover, identity theft, and fraud. The attackers don't need sophisticated hacking tools or years of cybersecurity expertise. They just need basic web knowledge and consumer-grade hardware.

The worst part? You probably can't protect yourself. The burden isn't on users to be more careful. The burden is on the services sending these links to stop doing it. And right now, many of them aren't.

TL; DR

- 175+ services expose sensitive data through weak SMS authentication links that can be enumerated or brute-forced

- Attackers need only basic web knowledge and consumer hardware to access accounts and steal personally identifiable information like SSNs and bank details

- Many links remain valid for days or months, providing extended attack windows with no additional authentication required

- Research identified 701 vulnerable endpoints from examining just a portion of SMS authentication traffic, suggesting the problem is far more widespread

- The solution lies entirely with service providers, not users, making immediate security reviews and authentication redesigns critical

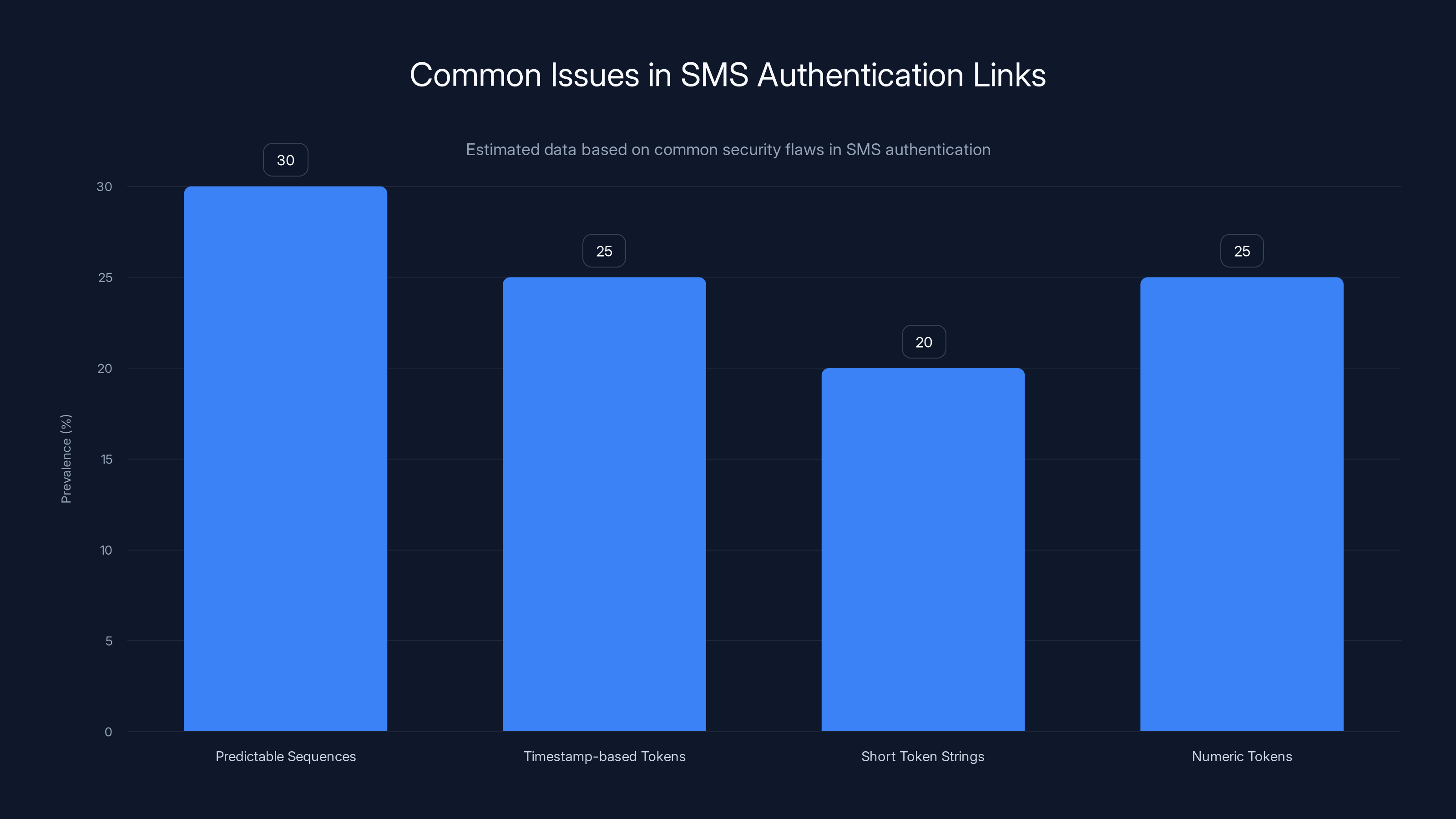

Estimated data shows that predictable sequences and numeric tokens are common issues in SMS authentication links, each accounting for about 25-30% of the problems.

How SMS Authentication Links Actually Work

Before we can understand why SMS authentication links are broken, we need to understand what they're supposed to do. The concept is straightforward: when you want to sign into a service without remembering a password, the service generates a unique link and sends it to your phone via SMS. Click the link, and you're authenticated. Simple. Elegant. Terrible.

In theory, the link contains a cryptographic token that's impossible to guess. This token proves that you received the message and clicked the link, so you must be the real account owner. The service generates a random 32-character string, embeds it in a URL, and sends it off. Each token should be unique and unpredictable. Each token should expire within minutes. Each token should be usable only once.

When implemented correctly, this approach actually works. The token is truly random, generated by a cryptographically secure random number generator. It's checked against a database on the backend to verify it hasn't been used before. The entire process is protected by TLS encryption when the link is clicked. It's a legitimate authentication method used by major services like Slack, GitHub, and Twitter.

But that requires the service to actually implement it correctly. And here's where everything falls apart.

Many services aren't using cryptographically secure random number generators. They're using predictable sequences. Some are generating tokens based on timestamps or user IDs in ways that can be reverse-engineered. Others are using such short token strings that the total number of possible combinations is small enough to brute-force in minutes. A service might generate a token like "ABC123" thinking it's random when an attacker can simply try "ABC124," "ABC125," "ABC126" and so on until they get a hit.

The research identified one particularly egregious example where a service was using only numeric tokens with low entropy. An attacker who received a valid authentication link could modify the token by a single digit and often gain access to another user's account. This isn't a clever attack exploiting an obscure edge case. This is basic enumeration that anyone with HTTP knowledge can perform.

Even when tokens are reasonably random, many services commit the next cardinal sin: they leave the tokens valid for far too long. Researchers found authentication links that remained valid for days, weeks, or even months after they were sent. This creates an extended attack window. An attacker who intercepts or gains access to an old text message can still use the link to compromise the account.

Some services make it even worse by not requiring any additional authentication after the token is validated. Once you click the link and the token checks out, you're logged in. Period. No confirmation email. No additional verification. Just full account access. If an attacker gets the link, they have the same access as you.

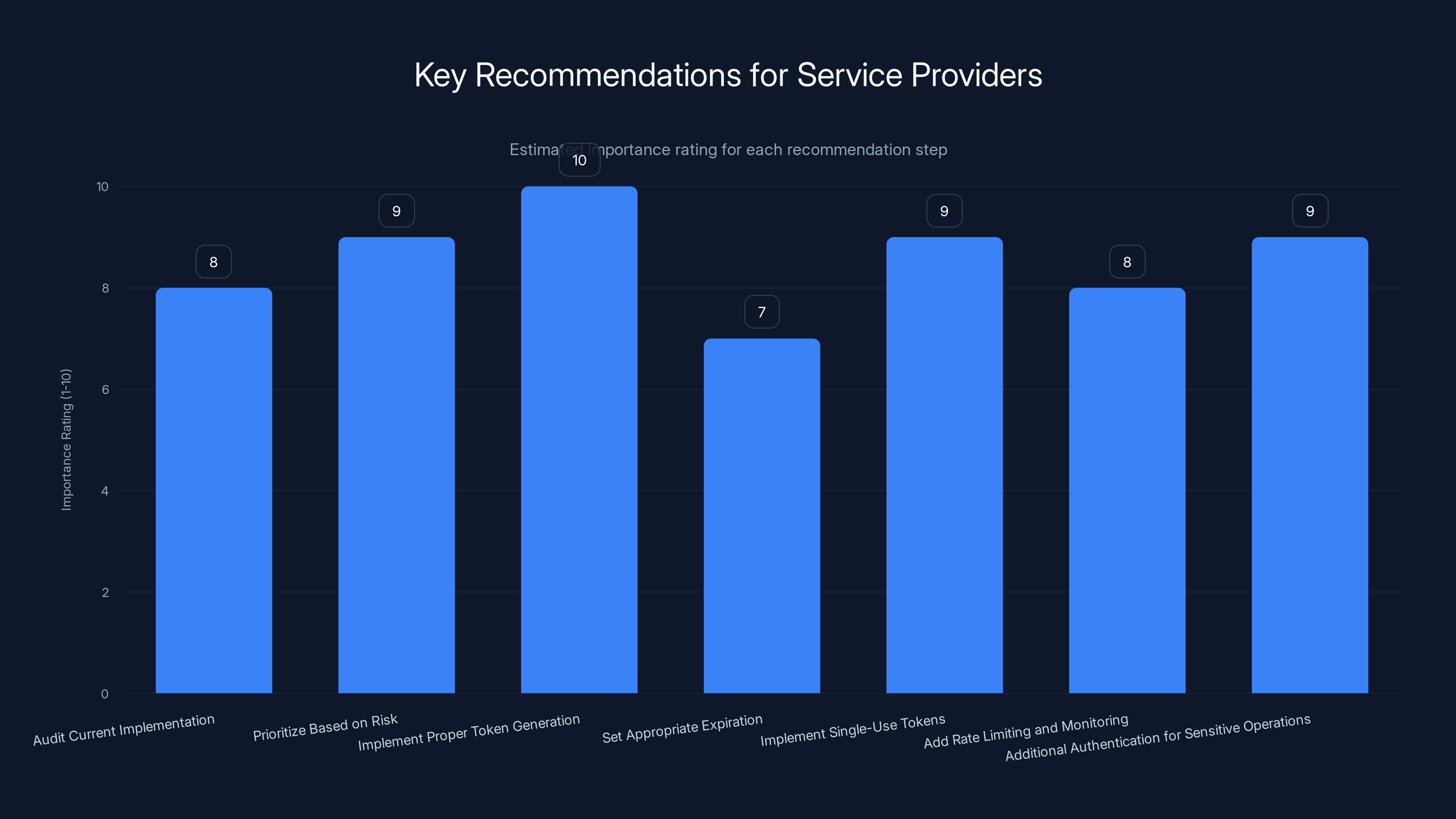

This bar chart estimates the importance of each recommendation step for service providers transitioning away from SMS link authentication. Implementing proper token generation is rated highest at 10, highlighting its critical role in security.

The Vulnerability Landscape: A Detailed Breakdown

The research behind this crisis examined SMS authentication across a limited but revealing window. Researchers accessed public SMS gateways—services that provide temporary phone numbers so people can receive texts without exposing their real numbers. These services exist primarily to protect privacy and prevent spam, but they also serve as a research lens into SMS authentication practices.

From 33 million text messages sent to over 30,000 phone numbers, researchers extracted 332,000 unique SMS-delivered URLs. These came from 701 endpoints across 177 different services. The scope is important: this isn't comprehensive. The researchers had ethical limitations and couldn't access SMS interception databases or capture the true scale of the practice. What they found was only the tip of the iceberg.

Of those 701 vulnerable endpoints, 125 services had tokens with such low entropy that attackers could enumerate valid URLs by modifying the token. Think about what this means. If you receive a link like service.com/auth/ABC123XYZ, an attacker can systematically try ABC123XYA, ABC123XYB, ABC123XYC until they find a valid user account. With proper automation, this takes minutes, not hours.

The enumeration attacks were often frighteningly effective. Researchers found that incrementing the token by even small amounts would grant access to different accounts. The token space was so small and predictable that attackers could systematically walk through thousands of valid accounts. One service used only numeric tokens, making it trivial to enumerate. Another used a sequential system where incrementing a number by 10 would jump to the next user account.

Beyond enumeration, 237 endpoints had other critical authentication flaws. Some allowed account access with no authentication beyond clicking the link. Others failed to implement proper session validation, meaning the token could be reused multiple times. Some endpoints didn't even log when tokens were accessed, leaving no audit trail of suspicious activity. A few particularly poorly designed services allowed attackers to enumerate tokens and then directly access backend APIs that returned sensitive user data.

The data exposed through these vulnerable endpoints included genuinely sensitive information. Researchers documented cases where they could access partially completed insurance applications containing financial details. In other cases, they could view complete user profiles with names, addresses, phone numbers, and account history. Some services exposed social security numbers. Others exposed bank account information, credit scores, and drivers license numbers.

One critical aspect of the research was the volume involved. These findings came from examining only a fraction of SMS traffic—specifically, traffic to temporary phone numbers from public SMS gateways. The actual scope of SMS authentication is far broader. Every service sending authentication links through SMS is a potential vulnerability. When researchers tried to estimate the true scale, they realized the data they had was likely a massive undercount.

Token Enumeration: When Incrementing Numbers Grants Account Access

Token enumeration is perhaps the most straightforward vulnerability because it requires almost no technical sophistication. The concept is simple: if tokens are predictable, you can guess them. The challenge for defenders should be making tokens truly random and non-enumerable. Yet many services fail at this fundamental task.

Here's how it works in practice. A user requests to sign in. The service generates a token and sends it via SMS. The token appears in a URL like auth.service.com/signin?token=ABC123. The user clicks it, the token is validated, and they're logged in. An attacker who receives a similar URL can try modifying the token: ABC124, ABC125, ABC126. Each time, the service receives the request, validates whether that token exists in the database, and if it does, grants access to the associated account.

With automation, an attacker can try hundreds or thousands of token variations per minute. If the service has a thousand active users and tokens are sequential, the attacker can enumerate all valid accounts in less than ten minutes. Even if there's no rate limiting or account lockout, the enumeration continues undetected.

One real example from the research illustrates how bad this can get. A service was using tokens based on sequential numbering combined with user IDs. An attacker who received a token for account 1000 could immediately deduce that account 999 and account 1001 had tokens with a predictable pattern. By analyzing a few captured tokens, an attacker could generate valid tokens for thousands of other accounts without ever needing to intercept more links.

Another particularly vulnerable service used only six-character alphanumeric tokens. While technically this provides about 2 billion possible combinations, in practice the service generated tokens sequentially from a much smaller pool. Researchers found that tokens were issued in a predictable order, and by capturing a few tokens over time, an attacker could project what tokens would be generated next and gain access to accounts before the legitimate users even received their links.

The scariest enumeration cases involved services where the token was derived from the username or email address. If you know someone's username, you can generate what their token should be. Researchers found services where the token was literally the MD5 hash of the email address. While MD5 isn't cryptographically secure, it's deterministic—hash the same email and you get the same token every time. Attackers don't even need to capture tokens; they can compute them offline.

What makes enumeration particularly devastating is that it's undetectable from the user's perspective. The attacker gains access to accounts without triggering the normal security alerts associated with login attempts. There's no notification that someone tried to access your account a hundred times. There's no account lockout. The service just silently processes each enumeration attempt and grants access to whoever has the token.

The fix for enumeration is theoretically simple: use cryptographically secure random number generation. Python has secrets module. JavaScript has crypto.getRandomValues(). Most languages have proper random libraries. Generate a token with sufficient entropy—at least 128 bits for security-critical applications. Use a proper random source, not the default seeded pseudo-random generators that many developers learn first.

Token enumeration can be exploited in minutes, while brute force attacks may take a few hours. Vulnerable links can be exploited almost instantly if a valid token is obtained. Estimated data.

Brute Force Attacks: When Entropy Is Catastrophically Low

When enumeration doesn't work because the tokens aren't sequential or predictable, attackers still have another option: brute force. If a token space is small enough, trying all possibilities becomes feasible even if each attempt is random. This is where entropy becomes critical.

Entropy measures how unpredictable something is. A coin flip has one bit of entropy. A random byte has eight bits. A random 16-byte string has 128 bits of entropy. For authentication links that must remain secure against brute force attacks, security professionals recommend at least 128 bits of entropy, often more for links that remain valid for extended periods.

Researchers found services using far less. One service was using tokens with only 40 bits of entropy. While 40 bits sounds reasonable (that's roughly a trillion possible combinations), it's actually brute-forceable. With consumer-grade hardware and modest cloud computing resources, an attacker can try a trillion combinations in a matter of hours. Another service was using only 32 bits of entropy—about 4 billion combinations. This can be exhaustively searched in minutes on modern hardware.

The vulnerability becomes worse when you combine low entropy with other factors. If tokens remain valid for days, the attacker has days to attempt brute force. If there's no rate limiting, the attacker can make millions of requests per second. Some services don't even log token validation attempts, so the attack leaves no evidence. Combine all these factors and a token with theoretically 40 bits of entropy becomes practically breakable.

One service researchers examined was using a token generator that appeared random but was actually seeded with the current timestamp. The attacker, knowing approximately when the token was generated, could reduce the effective entropy from 128 bits to about 20 bits—making it trivial to brute force. The developer had implemented randomness, but didn't understand how their random source worked, defeating the entire security model.

Brute force attacks are particularly insidious because they can be distributed. An attacker doesn't need to attack one service with all their computing power. They can distribute token guesses across multiple cloud servers, multiple IP addresses, making detection difficult. A service that sees one request per millisecond might dismiss it as normal traffic, but if that pattern repeats across thousands of tokens, it's clearly an attack.

The fix for low entropy requires understanding your threat model. How much entropy do you actually need? If tokens expire in five minutes, the attack window is narrow and slightly lower entropy might be acceptable. If tokens remain valid for months, you need high entropy. If there's no rate limiting, you need higher entropy than if you limit each IP to one attempt per second. Most security professionals recommend defaulting to 128 bits and not going lower without specific justification.

Yet many services were doing the opposite. They were using minimal entropy, keeping tokens valid for long periods, not implementing rate limiting, and storing no logs. This wasn't a flaw in a single authentication library. This was a pattern of security negligence across dozens of services.

Lack of Token Expiration: Attacks That Succeed Months Later

Imagine sending your house key to someone in a letter that gets intercepted. The security expert response would be to change your locks immediately. Yet many services are sending authentication tokens valid for months, providing attackers with extended windows to exploit leaked or intercepted messages.

Researchers found authentication links that remained valid for 30 days after generation. Some were valid for 90 days. A few were valid indefinitely. The reasoning behind these decisions is sometimes understandable—users forget to use links, drop their phones in water, run out of battery. But the security cost is enormous.

Token expiration directly impacts attack complexity. A token valid for five minutes creates an attack window that's measurably small. An attacker must work quickly. A token valid for 30 days allows leisurely enumeration or brute force. The attacker can work methodically, trying thousands of tokens over days or weeks. No urgency. No pressure.

Historical data amplifies this risk. SMS messages can be recovered from cloud backups, restored from old phones, discovered in data breaches of carriers or temporary SMS services. Researchers have previously discovered databases containing millions of historical SMS messages, including authentication links sent years earlier. If those links are still valid, old data breaches suddenly become new attack vectors.

This happened in 2019 when researchers discovered a database containing millions of stored SMS messages sent between a business and its customers over years. The database included usernames, passwords, university finance application links, authentication codes, discount codes, and job alerts. If any of those authentication links were still valid, attackers could have accessed those accounts years after the messages were sent.

The simplest fix for this vulnerability is straightforward: set aggressive token expiration. Five to ten minutes is reasonable for most use cases. The user sees the text, it's fresh in their mind, they click immediately. If they take longer, they can request a new link. Yes, this creates friction. But it dramatically reduces the attack surface.

But many services treated token expiration as an afterthought. The focus was on user convenience, not security. Request a link, use it anytime in the next month. No need to rush. It's more user-friendly. It's also more attacker-friendly. And attackers have more time and patience than most users.

The issue becomes compounded when you consider that token expiration must be enforced on the server side, not the client side. A link like service.com/auth/token?expires=2025-02-01 can't be trusted because the attacker can simply change the expiration to 2026-02-01. Tokens must be stored on the server with a server-side expiration timestamp. This requires database lookups on each authentication attempt, which some services treated as overhead to be minimized.

Research identified 125 services with predictable authentication links, highlighting a critical security flaw in SMS-based authentication. Estimated data.

No Additional Authentication: The Final Failure

Here's where the security model breaks down completely. Many services, after validating that a token is correct, grant full account access with no additional verification. No email confirmation. No security questions. No additional factor of authentication. Just full access.

Think about the threat model this creates. An attacker intercepts or discovers an authentication link. They click it. The service verifies the token is valid. The service logs them in. They now have complete access to the account. They can change the password. They can enable two-factor authentication in their favor. They can download all user data. They can execute transactions. They can do everything the legitimate account owner can do.

This becomes particularly dangerous when combined with other vulnerabilities. If a token can be enumerated, an attacker doesn't just get one account—they get many. If a token can be brute-forced, they can access accounts at scale. If tokens remain valid for months, the attacker has plenty of time to work. And with no additional authentication checks, every successful token validation results in immediate account compromise.

The research identified services where this failure was especially acute. One service allowed full account access through a token, and the account included API credentials for connecting to external services. An attacker could compromise one account and use its credentials to access the user's email, cloud storage, and connected applications. A single vulnerable link became a pivot point for accessing the entire digital life of a user.

Another service allowed full account access through a token and then allowed the attacker to change account details without any re-authentication. The legitimate owner could lose access to their account completely. They wouldn't know they'd been compromised until they tried to log in and found their password changed.

The security architecture that makes sense is layered. First, the token validates that you received the SMS. But then, there should be additional checks. Do you want to enable two-factor authentication on this login? Verify your email address? Answer a security question you set up previously? These additional factors don't need to be burdensome, but they should exist.

However, this adds friction. It means more steps before the user is logged in. It means more potential failure points. So services minimized these checks in pursuit of simplicity. The result is a system where anyone with a valid token has complete access.

The better approach is to design for different risk levels. New login from a new device, new location, new IP address? Maybe require additional authentication. Login from a familiar device that has logged in successfully many times before? Perhaps just the token is sufficient. This requires understanding user login patterns and maintaining state about devices, but the result is better security without excessive friction.

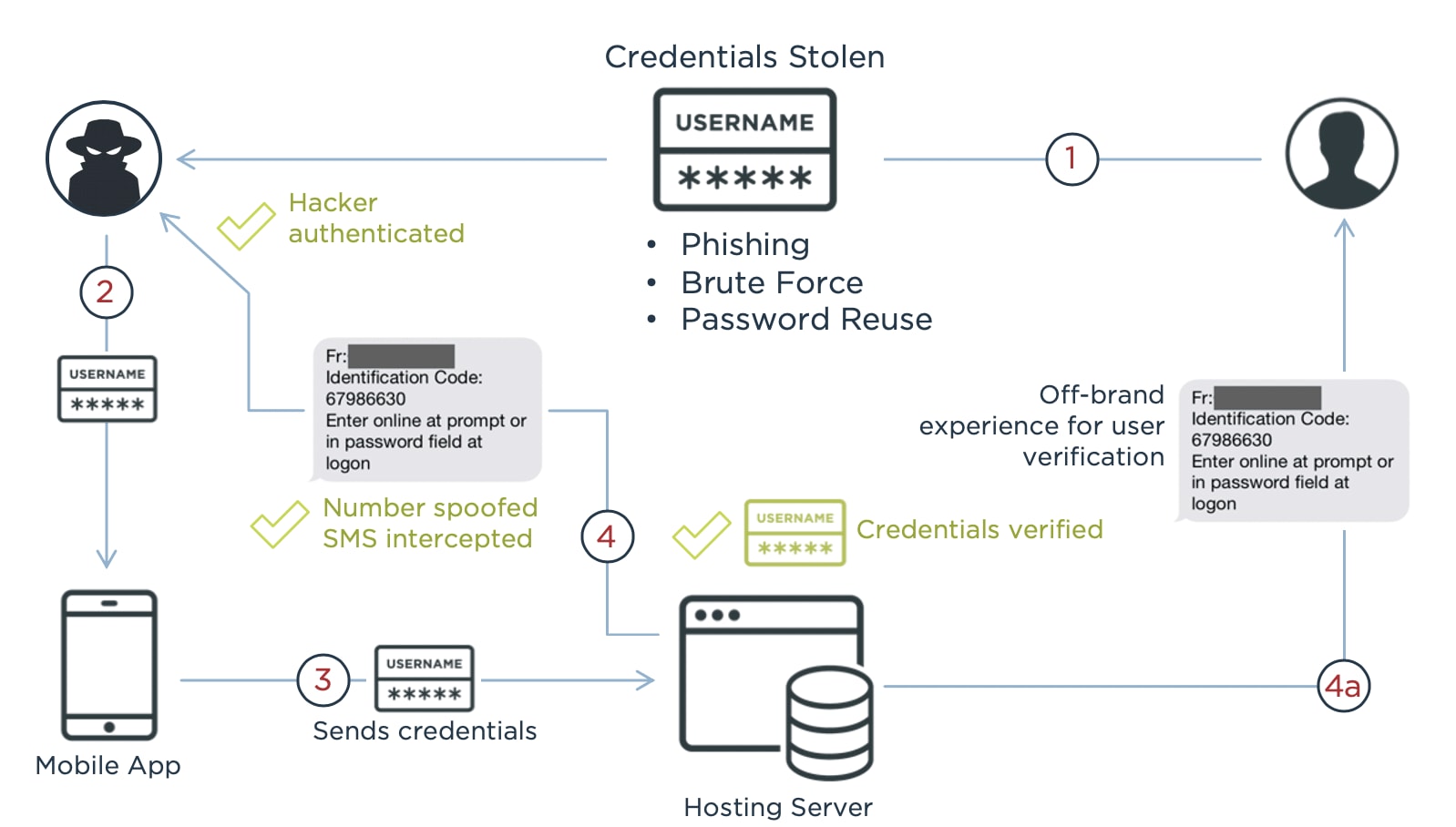

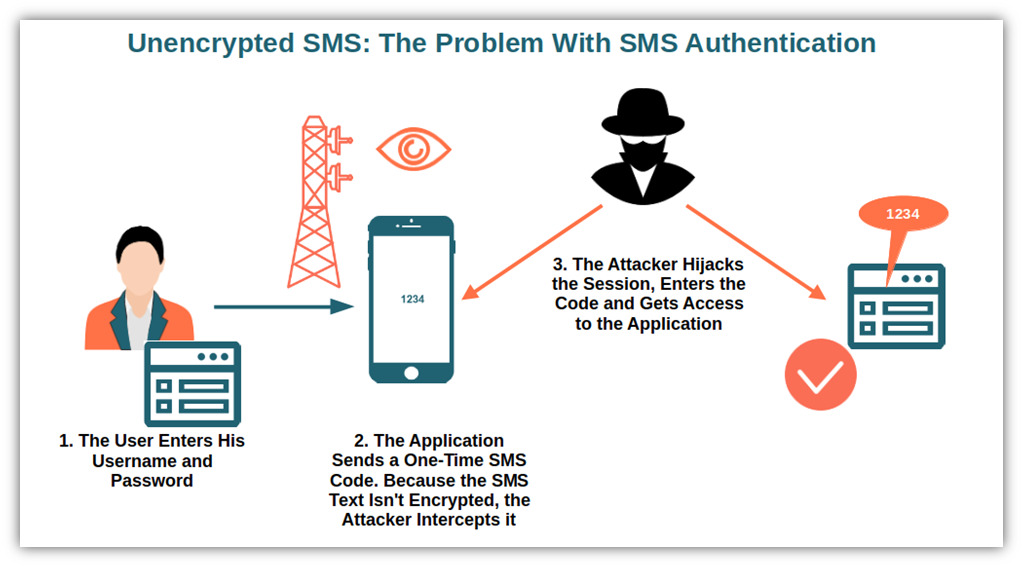

The Interception Vector: SMS Is Unencrypted and Insecure

Authentication links in SMS messages face an additional attack surface that links sent through other channels don't: SMS itself is fundamentally insecure. Text messages are transmitted in cleartext. They're stored unencrypted on devices and servers. They can be intercepted at multiple points along the transmission chain.

SMS traffic crosses through multiple network operators and intermediaries. The sending service connects to an SMS gateway provider. The gateway provider connects to your mobile carrier. Your carrier delivers the message to your phone. Each of these hops is a potential interception point. While the final segment to your phone is typically encrypted by the mobile carrier, the connections between carriers and gateways often are not.

Researchers have previously discovered vast databases of SMS messages stored with minimal security. In one famous case, a misconfigured Amazon Web Services bucket exposed millions of SMS messages, including authentication links and personal details like names and addresses. These weren't specifically targeted breaches—just exposed databases where companies stored SMS records with public access enabled.

Historically, researchers have found SMS databases from telecommunications companies, SMS gateway providers, and backup services containing complete records of billions of messages. These databases sometimes contained messages from years earlier, and if authentication links weren't expired, the messages represented active vulnerabilities.

The interception risk also applies to consumer devices. SMS messages are stored on phones with minimal security by default. If your phone is physically compromised, stolen, or forensically analyzed, an attacker can access your message history. Backups stored in cloud services might be compromised through weak credentials or account takeover. A breach of a backup service could expose millions of messages.

Compare this to authentication mechanisms that don't rely on SMS. A password exists only in the user's memory (ideally) or encrypted in a password manager. An authenticator app like Google Authenticator stores secrets locally on the device and generates time-based codes that don't transmit over SMS. Even email-based authentication links have the advantage that they arrive in a centralized email account where you have visibility into all of them.

The SMS vector introduces a third-party interception risk that other authentication methods don't have. Your carrier, the SMS gateway, other carriers, network equipment operators—all have potential access to the message. This isn't a theoretical risk. Researchers have documented real cases of SIM swaps, carrier employee compromise, and wholesale SMS interception.

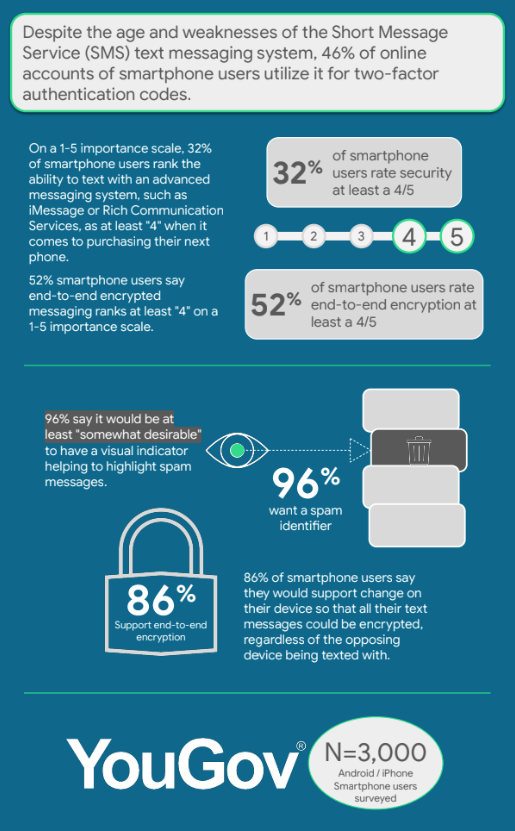

The security community has long recognized SMS's vulnerability. This is why regulations like PCI-DSS prohibit using SMS for account recovery on sensitive accounts. This is why many security professionals recommend moving away from SMS authentication entirely. Yet the practice persists because SMS remains nearly universal—even people without smartphones have it—and it feels simple.

The study found 125 endpoints with low entropy tokens and 237 with other critical flaws, highlighting significant vulnerabilities in SMS authentication systems. Estimated data.

Access Control Failures: When A Link Grants Too Much

Beyond the vulnerabilities with the tokens themselves, many services had fundamentally broken access control. A valid token might grant access not just to sign in, but to modify account data, access APIs, or retrieve sensitive information directly.

Researchers documented cases where clicking an authentication link granted access to the backend API used by the service's mobile app. An attacker with a valid token could make direct API calls to retrieve user data, modify user data, or even enumerate other users. The authentication link didn't just grant login; it granted an active API session.

Another vulnerability pattern emerged where authentication links granted access that persisted beyond a single session. The attacker could use the link to log in once, get redirected to the home page, and the attacker would be logged in as the user. But the token might also grant additional access through stored cookies or session tokens that themselves had no expiration. Even if the user later requested a password reset or realized their account was compromised, the attacker might retain access through the lingering session.

Some services had granular access control but failed to apply it correctly. An authentication link might grant access to read user profile information, which should be fine. But due to poor API design, reading user profile information also exposed API keys, authentication tokens for third-party services, or other sensitive data. The attacker didn't need specialized privilege escalation; the normal endpoint revealed everything.

Access control failures often occur because services don't properly separate authentication from authorization. Authentication answers the question: "Is this person who they claim to be?" Authorization answers: "What should this person be allowed to do?" Many services treated SMS link validation as granting full authorization. Once the token validates, the user has all access they need. This is incorrect.

The proper model uses separate concerns. An authentication link proves you received the SMS. This grants you a login session. The login session itself has limited scope—perhaps just the ability to change your password or view your profile. If you want additional capabilities, you provide additional authentication through a password or second factor. Different operations require different authorization levels.

Yet many services didn't implement this separation. They used authentication links as if they were equivalent to full account access. The result is that compromising a single token compromises the entire account.

The Real-World Implications: Who's Actually Affected

The research documented that vulnerable endpoints belonged to 177 services with millions of active users. These weren't obscure startups. They included well-known services that you likely use. The scale means that the average person probably has an account on at least one of these vulnerable services.

When researchers could determine user identity information from the vulnerable services, they found complete personal details. Insurance companies exposing partially completed applications with financial information. Utilities exposing account details and service addresses. Financial services exposing account information. E-commerce platforms exposing shipping addresses and purchase history.

The actual harm depends on what information the service holds. A vulnerable link to a game company might grant access to minimal user data. A vulnerable link to a financial services company might grant access to account numbers, transaction history, and personally identifiable information that can be used for identity theft.

Identity theft is a particular concern. Attackers who gain access to multiple accounts can collect pieces of personal information from each. A service might expose your name and address. Another might expose your date of birth and SSN. A third might expose your phone number and email. Collected together, this information is gold for identity theft and fraud.

The attackers who exploit these vulnerabilities range from simple fraudsters to organized crime. Small-time scammers might target specific high-value accounts. Larger operations might enumerate thousands of accounts, gain access to each, and harvest whatever data they find. The data gets sold on dark web markets for mere dollars per account, compounding the victim impact.

What makes the harm particularly insidious is that many victims never know they were compromised. If the attacker just looks around and doesn't change anything, the user sees no evidence of intrusion. By the time identity theft occurs or fraud is committed using stolen information, weeks or months have passed and the trail has gone cold.

Longer token validity periods significantly increase security risks, with indefinite tokens posing the highest risk. Estimated data based on typical security assessments.

Why Services Still Use SMS Authentication Despite Known Risks

Given these documented vulnerabilities, you might wonder why any service still uses SMS authentication. The reasons are complex and involve the interaction between user experience, perceived ease of implementation, and cost.

First, SMS authentication feels simple. Users understand it: you get a text, you click a link, you're logged in. No password to remember. No authenticator app to install. No security questions to set up. This perceived simplicity is enormously appealing to product teams trying to reduce friction in the signup and login flow.

The cost argument matters, too. Implementing password-based authentication properly requires password hashing, salting, stretching, and regular security updates as hashing algorithms improve. It requires sending password reset links and implementing secure password reset flows. It requires educating users about password security. SMS authentication, by contrast, outsources the heavy lifting to SMS gateway providers. The service just sends a message and validates a link.

There's also the accessibility argument. Not everyone uses smartphones that can run authenticator apps. Not everyone uses email. But virtually everyone can receive SMS messages. Building authentication that works for the broadest possible audience means supporting SMS.

The industry failed to address security properly because there were no consequences for the failures. A service with poor SMS authentication security faces no regulatory penalties, no liability, and no financial damage from the breaches. The users are harmed, but the service suffers only reputational damage if the breach becomes public. And many breaches never become public.

Finally, there was an assumption among service developers that SMS was inherently secure. After all, it's mediated by phone carriers and requires access to your actual phone. This assumption is wrong—SMS can be intercepted, SIM cards can be swapped, and phone numbers can be compromised. But the assumption persisted because carrier security is invisible to users.

The result of these converging factors is that services optimized for user convenience and perceived simplicity at the expense of actual security. They chose SMS links because they seemed easier, not because they were secure.

What Actually Secure Passwordless Authentication Looks Like

If SMS links are broken, what should services use instead? The security community has well-established alternatives, each with different trade-offs.

WebAuthn is the modern standard for passwordless authentication. It uses public-key cryptography where your device stores a private key and the service stores the public key. When you authenticate, your device signs a challenge from the server without ever transmitting the private key. Even if the server is compromised, attackers get only the public keys, which can't be used to impersonate users. WebAuthn is already built into modern browsers and supported by hardware security keys, phones, and laptops.

Time-based one-time passwords (TOTP) are more old-school but reliable. An app like Google Authenticator stores a secret that's synchronized between your device and the service. Every 30 seconds, both generate the same 6-digit code based on the current time. The code is valid only for those 30 seconds. An attacker who intercepts a code can't use it 30 seconds later. TOTP doesn't require any internet connection and works even if your authenticator app is offline.

Passkeys, standardized through FIDO2, combine the best of both worlds. Your device stores a key that proves your identity to the service. When you sign in, your device asks for biometric authentication or a PIN, then cryptographically signs the authentication request. The service never sees your biometric or PIN, just the signed proof that you authenticated on your device. This is what Apple's "Sign in with Apple," Google Passkey, and Microsoft Passwordless Sign-in implement.

All of these alternatives share common characteristics. They don't transmit secrets through SMS. They don't rely on URLs that can be guessed or intercepted. They use cryptography that can't be broken by enumeration or brute force. They have built-in mechanisms to prevent replay attacks and ensure authentication can't be forged.

The transition away from SMS authentication requires education. Services need to understand that simplicity doesn't mean insecurity. They need to implement proper alternatives. Users need to understand the new authentication flows. But the transition is already happening. Major services have implemented WebAuthn and Passkey alternatives. The security community is providing guidance. Standards are mature and well-documented.

The services that continue using only SMS authentication are betting that nobody will notice or care about the vulnerabilities. The research described here proves that assumption is wrong.

The Burden Falls on Service Providers

One of the most important findings from the research is who bears responsibility for fixing this problem. The researchers were explicit: the burden is on service providers, not users.

Users can't protect themselves by being more careful. You can't tell if an SMS link is using cryptographic tokens or sequential numbers. You can't check if it will expire in five minutes or five months. You can't verify that clicking the link grants only login capability or whether it grants API access too. The vulnerabilities are invisible to users.

Users also can't simply avoid services with vulnerable authentication because the research showed these were well-known services with millions of users. You might avoid one vulnerable service, but you probably use several. The breadth of the problem means opting out entirely isn't practical.

This is why the research authors emphasized that the burden is on service providers. They're the ones implementing the authentication. They're the ones responsible for security. They're the ones who have the knowledge and tools to fix it.

Service providers need to perform security reviews of their authentication flows. They need to audit how tokens are generated. They need to verify proper entropy. They need to implement appropriate expiration. They need to add additional authentication factors for sensitive operations. They need to remove unused authentication endpoints that create unnecessary attack surface.

The good news is that fixing these issues is straightforward. Use cryptographically secure random number generators. Generate tokens with sufficient entropy. Set appropriate expiration times. Implement rate limiting to prevent brute force. Log authentication attempts for security monitoring. These aren't complex or expensive changes. They're fundamental security practices that should be standard.

The bad news is that despite these issues being documented in research, some services haven't fixed them. This suggests either that security isn't a priority, or that fixing vulnerabilities in production authentication systems is complex because of dependent systems and backward compatibility concerns.

Regulatory and Compliance Implications

These vulnerabilities also create regulatory problems for service providers. Depending on the industry and jurisdiction, failing to properly secure authentication might violate compliance requirements.

Under the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), companies must implement appropriate technical and organizational measures to protect personal data. Weak authentication that leads to personal data breaches could violate GDPR requirements. The GDPR also requires that data breaches be reported within 72 hours and affected individuals notified.

The Payment Card Industry Data Security Standard (PCI-DSS) explicitly prohibits using SMS for certain types of authentication on payment accounts. If a payment processor is using SMS link authentication for account access, it's violating PCI-DSS requirements.

Under the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), healthcare organizations must implement strong authentication mechanisms. Weak SMS link authentication likely fails HIPAA security requirements.

Many financial regulatory frameworks similarly require strong authentication. The Securities and Exchange Commission, the Federal Reserve, and other financial regulators have issued guidance on authentication security. Weak SMS link authentication would fail these standards.

Beyond direct regulatory violations, there are liability concerns. If a service is compromised through these known vulnerabilities, and a user suffers harm, the service could face legal liability. The fact that these vulnerabilities are documented in published research means the service's failure to address them is arguably negligent.

Some services might argue that these regulatory requirements don't apply to them because they're not regulated by these specific agencies. But the regulatory landscape continues expanding. States are implementing their own data protection requirements. The Federal Trade Commission is increasingly aggressive about data security. The standard for "reasonable security" is continuously evolving, and it increasingly requires strong authentication mechanisms.

Services relying on SMS link authentication should proactively audit their implementation and move toward more secure alternatives. The cost of fixing vulnerabilities now is far less than the cost of addressing a breach and regulatory enforcement later.

The Future of Authentication: Where We Should Be Going

The authentication landscape is evolving rapidly. The password is gradually being phased out in favor of more secure alternatives. The research on SMS link vulnerabilities confirms what the security community has been saying for years: passwordless authentication is the future, but it has to be done correctly.

WebAuthn adoption is accelerating. Apple, Google, and Microsoft have all committed to implementing Passkey support across their platforms. The FIDO Alliance continues expanding certification of hardware and software that supports WebAuthn standards. Within five years, WebAuthn will likely be the default authentication method for mainstream web applications.

Push-based authentication, where a notification is sent to your trusted device asking you to approve the login, is also gaining adoption. This approach removes the vulnerability of tokens in URLs entirely. Instead, you approve login on a device you control. If your SMS is intercepted, the attacker can't use it because they don't have access to your phone to approve the notification.

Biometric authentication is becoming more reliable and prevalent. Face recognition on phones, fingerprint sensors, and even retinal scanners are improving. Biometric authentication can be integrated with cryptographic authentication using standards like WebAuthn to create a system where both the device and the biometric must match before authentication succeeds.

Contextual authentication, where the service evaluates the risk level of the login attempt and adjusts authentication requirements accordingly, is becoming more sophisticated. New device? Different location? Request additional authentication. Familiar device? Same location as usual? Maybe just the initial factor is sufficient. This allows security to scale with actual risk.

The trajectory is clear: away from shared secrets like passwords or SMS links, toward mechanisms that prove you control a specific device and biometric, or that you have a cryptographic key. These mechanisms are inherently more resistant to interception, enumeration, brute force, and other attacks that plague the current approaches.

The transition won't be instantaneous. Some users will be slower to adopt. Some services will lag in implementing modern authentication. But the direction is set. The era of SMS-based authentication is ending, not because it works well, but because better options exist and the security community is finally strong enough to enforce better standards.

Recommendations for Users: What You Should Do Right Now

While the burden is primarily on service providers, users can take some steps to reduce their risk from these vulnerabilities.

First, if you have a choice, use authentication methods other than SMS when they're available. Email-based authentication isn't perfect, but it's often slightly better than SMS because you have a record of all authentication emails in your inbox, making unauthorized logins more visible. Password plus a hardware security key or authenticator app is significantly more secure than SMS alone.

Second, monitor your account activity. Most services now provide a login history or device management page. Check it regularly. If you see logins from locations or devices you don't recognize, change your password immediately and check if the attacker made any account modifications.

Third, use password managers to create and store unique, strong passwords for every service. If one service's authentication is compromised and the attacker gains access, at least they won't be able to use your credentials to compromise other services.

Fourth, enable every security option the service offers. If the service offers two-factor authentication beyond SMS, enable it. If the service offers security keys, use them. If the service offers recovery codes, store them securely. Layered security means that even if one layer is compromised, others protect you.

Fifth, be cautious about clicking authentication links in unexpected contexts. If you didn't request the authentication link, don't click it. If you requested it an hour ago but just received it now, something might be wrong. If the link looks unusual or the domain is slightly different from what you expect, don't click it.

Sixth, report security issues to services when you find them. If you notice that authentication links appear to be sequential or easily enumerable, tell the service. Many services have security researcher policies that reward vulnerability reports.

Finally, consider whether you actually need an account with a service. If the service is optional and you're concerned about its security, simply not having an account is a form of protection. Your account can't be compromised if it doesn't exist.

Recommendations for Service Providers: What You Should Do

For services still using SMS link authentication, the path forward is clear, even if implementation is complex.

First, audit your current implementation. How are tokens generated? Are they using cryptographically secure randomness? What's the entropy of your tokens? How long are tokens valid for? Are tokens single-use or reusable? Can tokens be enumerated? Are there additional authentication checks beyond the token? Document all of this.

Second, prioritize based on risk. Services handling sensitive data should move away from SMS link authentication immediately. Services with minimal sensitive data can take a more measured approach. But all services should have a roadmap for deprecating this authentication method.

Third, implement proper token generation. If you're currently using predictable tokens, fix it immediately. Use your language's cryptographically secure random function. Generate tokens with at least 128 bits of entropy, preferably more. Test that tokens actually are random using statistical tests.

Fourth, set appropriate expiration. Five to ten minutes is reasonable for most use cases. If users regularly receive links and then wait to use them later, you might extend to 15 minutes. But anything longer than an hour is questionable from a security perspective.

Fifth, implement single-use tokens. Once a token is validated, immediately invalidate it. If the user needs to authenticate again, they request a new link. This prevents replay attacks and limits the window for attackers to use a compromised token.

Sixth, add rate limiting and monitoring. Log all token validation attempts, including failures. Alert on unusual patterns like many failed validations from a single IP. Implement rate limiting per IP to prevent brute force attacks. These measures should be logged and reviewable.

Seventh, implement additional authentication for sensitive operations. A user can sign in with a valid token. But if they want to change their password, add a trusted device, or view sensitive information, require additional authentication. This limits the damage even if a token is compromised.

Eighth, provide users with alternative authentication options. Offer email-based authentication, WebAuthn, TOTP, or passkeys. Users who want stronger security can choose it. Users who prefer simplicity can use SMS links. But don't make SMS the only option.

Ninth, sunset SMS link authentication. Set a timeline, perhaps 12-24 months out, when SMS link authentication will no longer be supported. This forces the migration but gives users time to adapt. Provide clear communication about why and what alternatives are available.

Tenth, engage security researchers. Implement a vulnerability disclosure policy. If researchers find issues, let them report privately instead of coordinating with you publicly. Fix issues quickly and thank researchers publicly once the issue is patched.

Implementing these changes requires effort and coordination. But they're all standard security practices that responsible service providers should implement regardless. The cost of fixing these issues now is minimal compared to the cost of a security breach.

FAQ

What exactly is an SMS authentication link?

An SMS authentication link is a URL sent to your phone that contains a cryptographic token. When you click the link, the service validates the token to confirm you received the SMS, then logs you into your account. It's designed as a passwordless authentication method, but many services implement it insecurely by using predictable tokens, long expiration times, or no additional verification requirements.

How can attackers exploit SMS authentication vulnerabilities?

Attackers can exploit these vulnerabilities in multiple ways. They can enumerate tokens by incrementing numbers in the URL to access other users' accounts. They can brute force tokens if the token space is too small. They can intercept SMS messages from misconfigured services or data breaches. They can request authentication links for accounts and wait for tokens to expire naturally while they work on breaking in. Each of these attacks requires only basic web knowledge and consumer-grade hardware.

Are these vulnerabilities found in major services?

Yes, the research identified 175+ services with millions of active users using vulnerable SMS link authentication. While the researchers couldn't identify all specific services for privacy reasons, they confirmed the vulnerabilities weren't limited to obscure startup services. Well-known services across insurance, utilities, financial services, e-commerce, and other categories were affected. Most people using the internet likely have accounts on at least one vulnerable service.

How long does it take for an attacker to exploit these vulnerabilities?

The time depends on the specific vulnerability. Token enumeration can succeed in minutes if the tokens are sequential. Brute force attacks on low-entropy tokens can succeed in hours using modern hardware. Attacking vulnerable links that don't require additional authentication can succeed immediately if the attacker has a valid token. Most of these attacks are faster than traditional password cracking and require no special equipment or extensive expertise.

Can I protect myself from these vulnerabilities?

You have limited ability to protect yourself because the vulnerabilities are in how services implement authentication, not in how you use services. You can't tell if a service is using predictable tokens or checking for proper authentication. You can't verify token entropy or expiration. You can monitor your accounts for suspicious activity and use strong, unique passwords, but the primary responsibility for fixing these vulnerabilities lies with service providers, not users.

Should I use SMS authentication at all?

If alternative authentication methods are available, use them. Email-based authentication, WebAuthn, TOTP apps, or passkeys are generally more secure than SMS links. But if SMS authentication is the only option and you trust the service, the risk of using it is outweighed by the benefit of having access to the service. Just ensure you monitor your account activity and use a unique password.

What will replace SMS authentication?

WebAuthn and passkeys are the future of passwordless authentication. These use public-key cryptography stored on your device to authenticate without ever transmitting shared secrets. Biometric authentication (fingerprint, face recognition) combined with cryptographic authentication is also becoming more prevalent. TOTP apps provide a more secure intermediate step that's already widely supported. These alternatives are more secure because they can't be enumerated, brute forced, or intercepted in the same ways SMS links can.

What should services do to fix this?

Services should audit their token generation, ensure tokens have sufficient entropy, set appropriate expiration times (5-10 minutes), use single-use tokens, implement additional authentication for sensitive operations, enable rate limiting, and log all authentication attempts. Many services should gradually migrate away from SMS link authentication toward more secure passwordless methods like WebAuthn or TOTP. This requires effort but uses standard security practices that any responsible service provider should implement.

Is SMS authentication illegal?

SMS authentication itself isn't illegal, but using it insecurely may violate regulatory requirements. PCI-DSS prohibits SMS authentication for payment card accounts. GDPR and other privacy regulations require appropriate security measures that weak SMS authentication may not satisfy. Services in regulated industries (financial services, healthcare, payment processing) should be particularly careful about SMS authentication implementation.

How many people are actually affected?

Based on the research examining a limited window into SMS traffic, at least millions of people have accounts on services vulnerable to these exploits. The researchers examined 33 million text messages and identified 175+ services. The true number of affected people is likely much higher because the research captured only a fraction of total SMS authentication traffic. Estimates suggest tens of millions of people could be at risk from these vulnerabilities.

Conclusion: The Path Forward

The research revealing these SMS authentication vulnerabilities represents a watershed moment for internet security. We have documentation of how hundreds of well-known services are implementing authentication in ways that are trivially exploitable at scale. We have proof that real users are being put at risk. We have clear evidence that the vulnerabilities can be fixed with straightforward changes. What we lack is urgency from service providers to actually implement those fixes.

The security community has provided warnings about SMS authentication for years. The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) deprecated SMS-based authentication back in 2016. Security researchers have published proof-of-concept attacks. Industry standards like WebAuthn and TOTP have matured and are ready for widespread deployment. The path forward has been clearly marked.

Yet the practice continues because it's profitable to ignore the vulnerabilities. Services continue using SMS links because they seem simple, feel user-friendly, and shift responsibility for security failures onto individual users or breach victims. The incentive structure doesn't reward security. It rewards user acquisition and retention. Until that changes, services will continue implementing insecure authentication.

What needs to happen is regulatory enforcement, industry pressure, and user awareness combining to make SMS link authentication untenable. If regulators clarified that weak SMS authentication violates data protection requirements, services would fix it immediately. If major platforms stopped accepting SMS-authenticated accounts, others would follow. If users understood the risks and demanded better security, companies would respond.

Individual users should take what protective measures they can, but understand that the responsibility is primarily on service providers. Use strong, unique passwords. Enable every security option the service offers. Monitor account activity. Choose services with better security practices when alternatives exist. Report vulnerabilities when you find them.

Service providers should treat this research as a wake-up call. Audit your authentication implementation. Fix the obvious issues immediately. Develop a roadmap to move away from SMS link authentication. Implement modern passwordless authentication methods. Engage with security researchers. Show your users that their security matters.

The future of authentication is passwordless, but it must be passwordless in a way that's actually secure. That future can't arrive soon enough. Until it does, millions of people remain imperiled by text messages they trust without knowing they shouldn't.

Key Takeaways

- 175+ major services use SMS authentication links with critical security flaws affecting millions of users

- Attackers can enumerate or brute-force tokens using basic web knowledge and consumer hardware in minutes to hours

- Many links remain valid for days or months, creating extended attack windows for account compromise

- Vulnerable endpoints expose social security numbers, bank account details, credit scores, and insurance information

- Users cannot protect themselves; the responsibility for fixing these vulnerabilities lies entirely with service providers who must implement secure token generation and modern passwordless authentication methods

Related Articles

- UStrive Security Breach: How Mentoring Platform Exposed Student Data [2025]

- Most Spoofed Brands in Phishing Scams [2025]

- 198 iOS Apps Leaking Private Chats & Locations: The AI Slop Security Crisis [2025]

- Best VPN Service 2026: Complete Guide & Alternatives

- Supreme Court Hacker Posted Stolen Data on Instagram [2025]

- LastPass Phishing Scam: How to Spot Fake Support Messages [2025]

![SMS Sign-In Links: A Critical Security Vulnerability Affecting Millions [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/sms-sign-in-links-a-critical-security-vulnerability-affectin/image-1-1769038653417.jpg)