Space X's Unexpected Turn Toward an IPO: The AI Data Center Revolution

Elon Musk spent years telling investors that SpaceX would go public only after establishing a permanent human settlement on Mars. That timeline kept slipping. Mars remained a distant dream. But something changed recently, and it's forcing one of the world's most secretive companies to reconsider its entire financial strategy.

The Wall Street Journal reported that Musk is now actively pushing SpaceX toward a public offering, potentially by July 2025. The reason isn't a sudden breakthrough in Martian colonization. Instead, it's something far more immediate and economically compelling: AI data centers in orbit.

This shift represents a fundamental pivot for SpaceX. For nearly two decades, the company focused on becoming a space transportation company. Launch rockets, deploy satellites, cut costs per kilogram to orbit. That mission succeeded brilliantly. SpaceX's Falcon 9 became the world's most reliable rocket. Starlink grew into a global satellite internet network. The company achieved what seemed impossible: reusable rockets that actually worked.

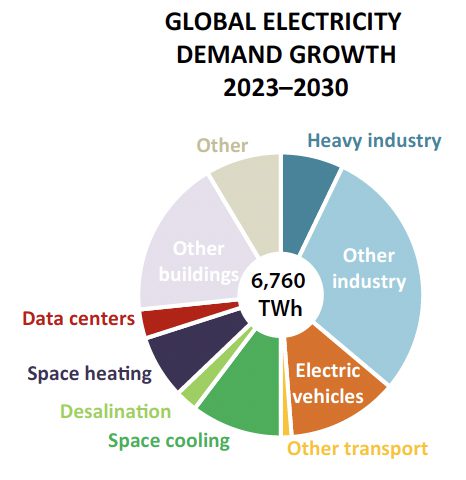

But the AI boom changed everything. Suddenly, the bottleneck wasn't getting to space. It was getting computing power. Data centers consume staggering amounts of electricity. They require vast amounts of water for cooling. They generate heat that strains local power grids. They take up enormous amounts of land. And despite all that infrastructure, they still have fundamental physical limitations.

Orbit, though, offers something different. Lower latency in certain applications. Potential thermal advantages in a vacuum. And perhaps most importantly to Musk, a new revenue stream that could dwarf anything SpaceX currently does. An AI data center company operating in space could be worth far more than a rocket company. That's the calculation driving this sudden change in strategy.

Musk runs both SpaceX and xAI, his artificial intelligence startup. The connection matters. XAI has been playing catch-up to OpenAI and Google in the AI arms race. A successful orbital data center would give xAI a unique competitive advantage. More fundamentally, it would help Musk consolidate control over a critical piece of AI infrastructure. Money flows between xAI and SpaceX. Orders go to SpaceX for launches. Data flows through xAI's networks. It's a vertically integrated advantage in an industry where such integration increasingly defines winners and losers.

This story matters because it reveals how space is being transformed from a government domain and distant dream into infrastructure for earthly commerce. The space industry is becoming less about exploration and more about utility. Less about flags planted on distant worlds and more about practical solutions to computational problems. Less romantic, perhaps, but far more economically significant.

Let's unpack what this IPO actually means, why it's happening now, what the technical challenges are, and what it signals about the future of both space and computing.

The Mars Promise That Wasn't (Yet)

For years, SpaceX's public stance on going public was remarkably consistent. Musk promised an IPO would happen, but only after the company achieved something major on Mars. This wasn't random messaging. It was calculated philosophy.

Musk built his entire vision around becoming a multiplanetary species. That meant Mars. Going public would require quarterly earnings reports, investor conference calls, and constant pressure to show short-term profits. That kind of pressure, Musk argued, would corrupt the long-term mission. You can't build a civilization on another planet while worrying about beating Wall Street's quarterly expectations.

It made sense philosophically. It also happened to be extremely convenient. SpaceX was wildly profitable. The company didn't need public capital markets. Staying private meant Musk could make unpopular decisions without shareholder approval. He could take moonshot risks. He could move capital around however he wanted. He could pursue ideas that wouldn't make sense to investors focused on quarterly returns.

But Mars remained far away. SpaceX developed the Starship rocket, an enormously ambitious fully reusable system designed to carry 100+ people to Mars. The company conducted test flights. Each one was expensive and often ended in explosions. Progress happened, but it was slow, messy, and expensive. A Mars landing with humans? Realistically, that's a decade or more away. Maybe two decades. Maybe it never happens at all, which is the kind of thing investors really don't like to hear.

Meanwhile, the world changed. AI exploded from a research curiosity into a trillion-dollar industry. Suddenly, everyone needed more computing power. Training large language models required vast arrays of GPUs. Running inference at scale required clusters of accelerators. Data centers became the new oil rigs. Control over data center infrastructure became as valuable as oil fields once were.

Musk, watching this unfold, recognized an opportunity that didn't require Mars. It required space, but not Mars specifically. It required orbit. And SpaceX was perfectly positioned to exploit that opportunity. The company already knew how to launch things reliably. It already had launch cadence. It already had lower costs than competitors. All it needed was capital to develop the hardware and infrastructure to make orbital data centers real.

Hence the IPO reversal. Mars could wait. Immediate, near-term space infrastructure was suddenly worth more than the decades-long promise of red planet colonization.

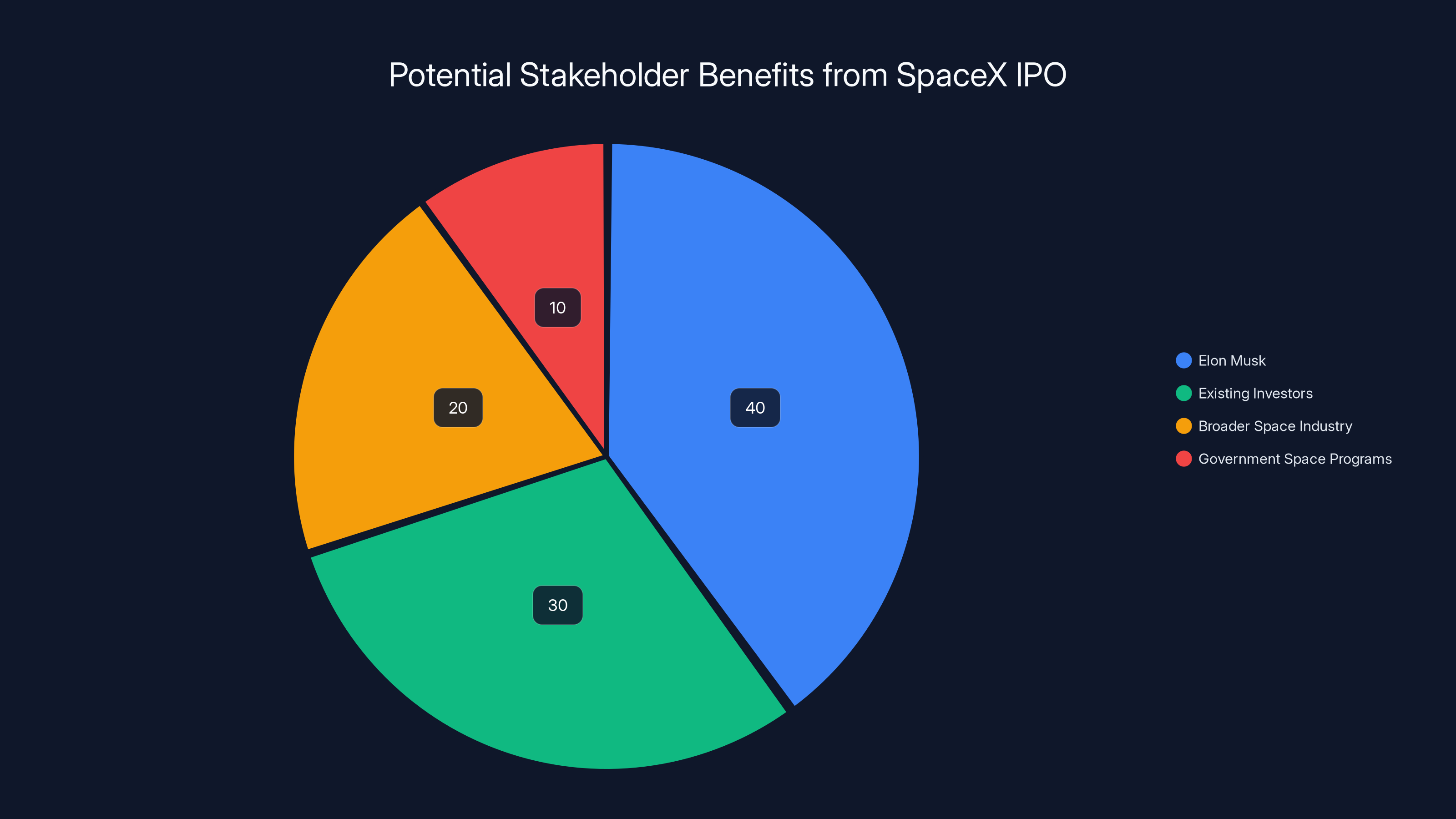

Estimated data shows Elon Musk and existing investors as the primary beneficiaries of a SpaceX IPO, with significant impact on the broader space industry and government programs.

Why AI Data Centers Can't Stay on Earth (Allegedly)

The case for orbital data centers rests on specific technical arguments. Some are convincing. Some are speculative. All of them matter for understanding why Musk is willing to abandon the Mars narrative.

Power Consumption and Grid Strain

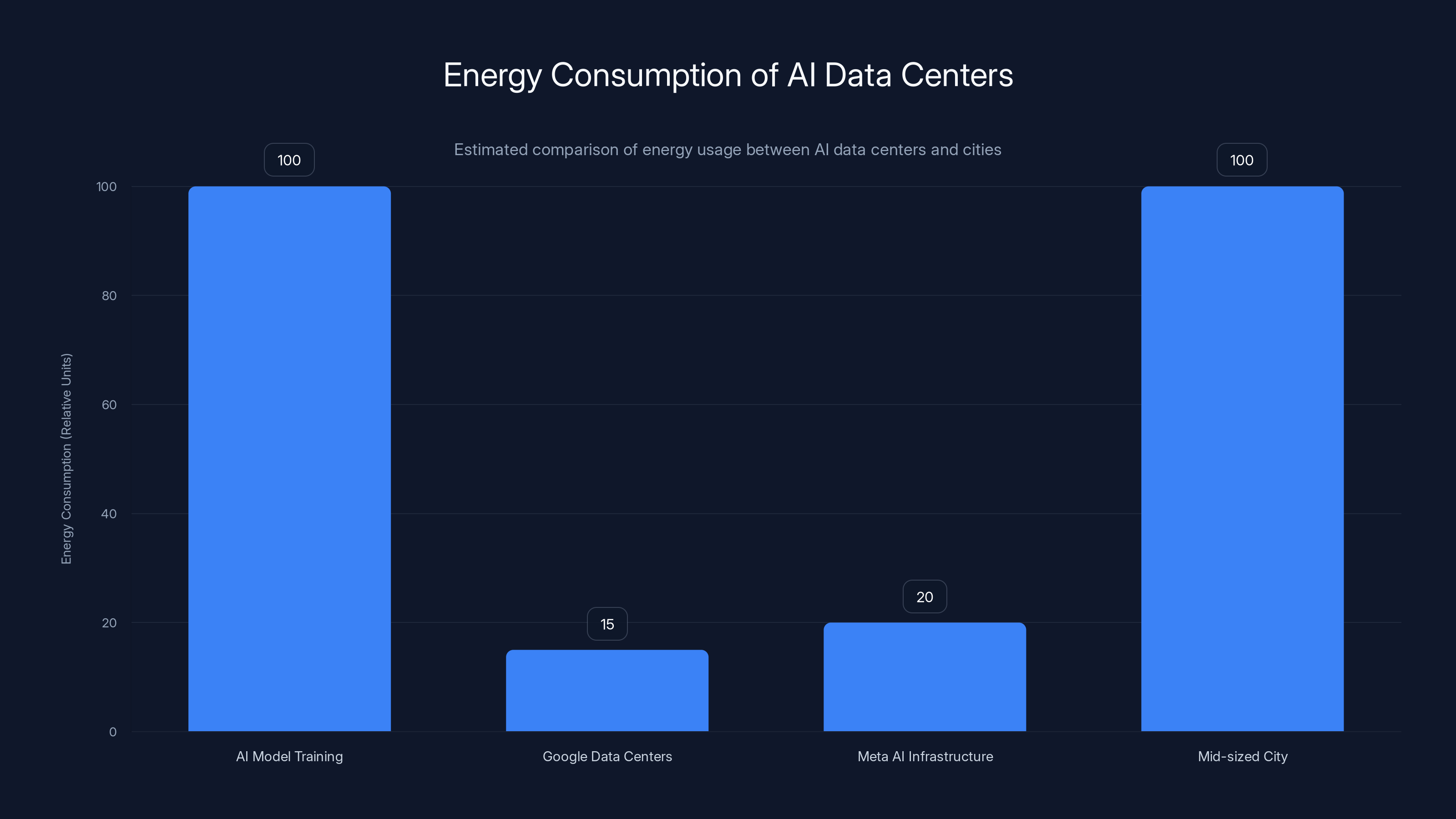

Data centers are power hungry in ways most people don't fully appreciate. A single large data center can consume as much electricity as a mid-sized city. Google's data center portfolio uses roughly 15% of the company's total energy budget. Meta's AI infrastructure demands more power every quarter. Both companies are scrambling to find clean energy sources and locations with cheap electricity.

The problem compounds when you're training cutting-edge AI models. A single run of training a large language model can consume as much electricity as hundreds of homes use in a year. When you multiply that across dozens or hundreds of training runs, you get numbers that start stressing power grids.

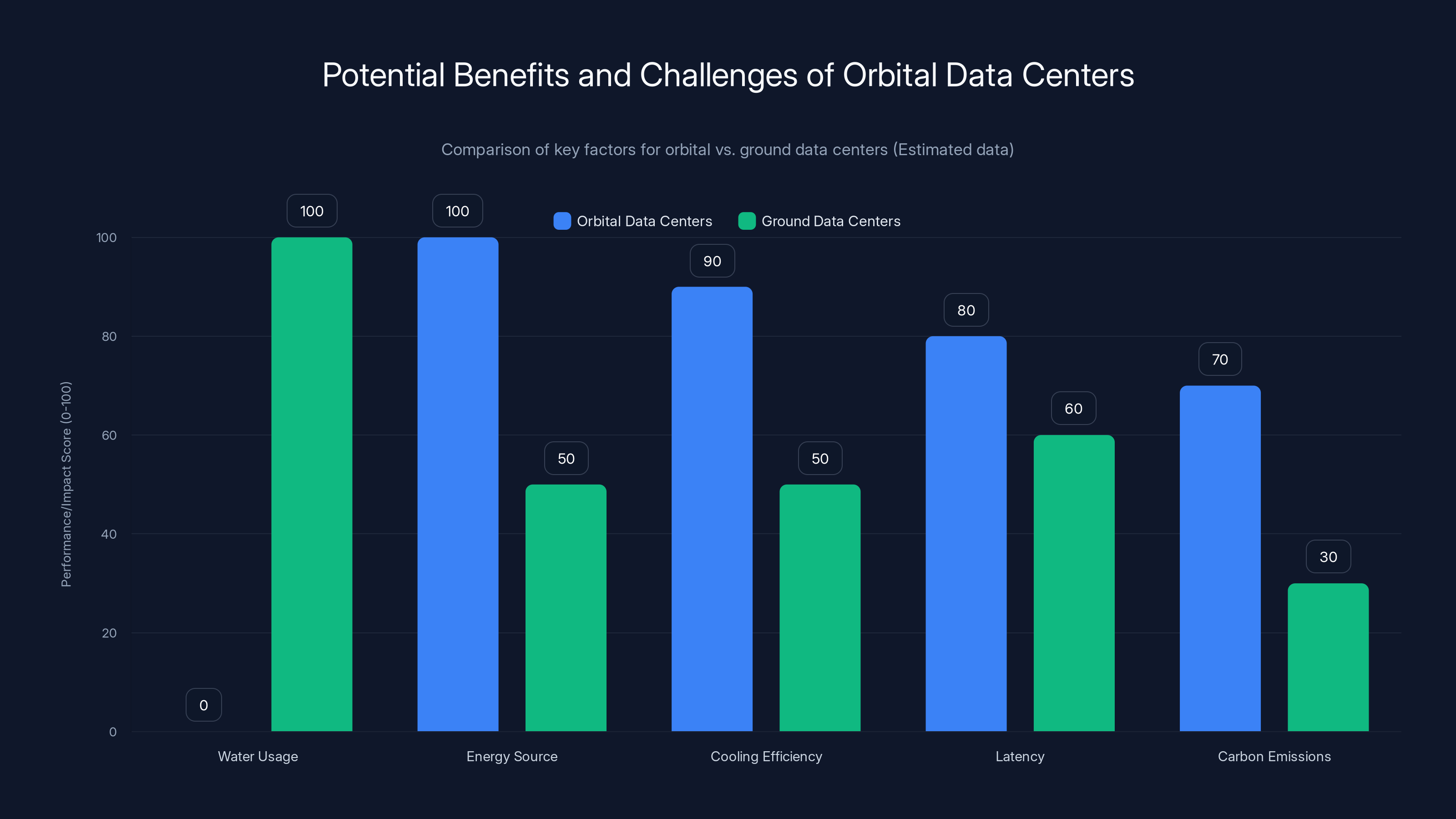

Orbit offers a potential solution. The sun shines constantly above the atmosphere. No clouds, no dust, no seasonal variation. Solar panels in orbit could theoretically capture far more energy per unit area than ground-based solar. That energy could power computational hardware without any grid connection at all. The power comes directly from the sun.

Of course, the logistics are nightmarish. You need to launch solar panels to orbit. You need to deploy them. You need to transmit the power somehow (wireless power transmission remains experimental). But the potential advantage is real: infinite power from the sun, no grid connection required, no infrastructure strain on Earth.

Thermal Management in Vacuum

Computers generate heat. The more powerful the computer, the more heat it produces. Data centers spend enormous amounts of money on cooling systems. Liquid cooling, air conditioning, water chillers. The exhaust heat often goes straight into the environment, creating localized hot spots that can damage ecosystems.

In space, there's no air to carry heat away. But there is radiation. Heat radiates away into space as infrared radiation. In theory, you could design hardware that dissipates heat directly through radiation into the vacuum. No cooling system needed. No water consumption. Just passive radiative cooling.

This is speculative. We haven't built computer systems specifically optimized for radiative cooling in vacuum. But the physics is sound. It could work. And if it does, it eliminates one of the biggest operational costs of modern data centers.

Latency Advantages

This argument is more contentious. Latency is the time it takes for data to travel from point A to point B. In ground-based data centers, latency is measured in microseconds or milliseconds, depending on distance. In space, distances are larger, so you'd expect latency to be worse, not better.

But there are specific use cases where orbital data centers might actually improve latency. High-frequency financial trading, for instance, wants the fastest possible connections. Satellites in geostationary orbit are about 22,000 miles up. That's far enough to introduce measurable latency. But Starlink satellites are in low Earth orbit, only about 350 miles up. For certain applications, an orbital data center could be closer to the customer than a ground-based data center thousands of miles away.

More speculatively, orbital data centers could enable what some call "edge computing at scale." Computation happens closer to the user, reducing latency and improving responsiveness. For real-time AI applications (autonomous vehicles, robotics, real-time translation), this could matter.

Again, this is mostly theoretical. Real data centers have built-in advantages from colocating with telecom infrastructure and power sources. But the latency argument isn't nonsensical. It's just unproven.

Regulatory Escape

This is the argument nobody wants to say out loud, but it's real. Data centers face increasing regulatory scrutiny. Environmental regulations limit power consumption. Water regulations limit cooling water usage. Labor regulations apply to on-site staff. Tax authorities want a piece of the revenue.

Orbital data centers would face no environmental regulations. No water regulations. No labor laws (nobody lives there). And the tax situation is murky at best. SpaceX could argue that its orbital data center is international airspace, subject to no nation's taxes. That's probably not true legally, but the argument doesn't sound completely ridiculous.

Musk didn't get wealthy by respecting regulations he disagrees with. The idea of a data center that could operate entirely outside regulatory jurisdiction probably appeals to him deeply.

Orbital data centers offer significant advantages in water usage and energy sourcing, but face challenges in carbon emissions due to rocket launches. Estimated data.

The Competition: Google, Blue Origin, and the Space Data Center Race

SpaceX isn't alone in pursuing this idea. This is a competitive space (pun intended), and it's heating up fast.

Google's Orbital Data Center Ambitions

Google announced plans to put a data center in orbit. The company began working with partners to develop hardware and infrastructure. Test launches were scheduled for 2027. Google already manages the world's largest AI infrastructure. Adding orbital capacity would give it unmatched computational reach.

Google doesn't have its own rocket company, which puts it at a disadvantage. It would need to pay SpaceX or another launch provider to deliver its hardware to orbit. That's expensive. That's a relationship dependency. For Musk, pursuing an orbital data center means having total control over the supply chain. Google is pursuing it, but through partnerships and existing launch providers.

Blue Origin and Jeff Bezos

Jeff Bezos, Musk's other major competitor in the space industry, has also suggested that orbital data centers make sense. Blue Origin hasn't made as bold a commitment as Google or Musk, but Bezos clearly sees the opportunity.

Blue Origin develops New Shepard (suborbital flights) and New Glenn (orbital heavy-lift rocket). New Glenn is supposed to compete directly with Falcon 9. If Blue Origin can develop its own orbital data center, it could potentially offer launch services, on-orbit assembly, and data center operations as one integrated service.

But Blue Origin is years behind SpaceX in launch cadence and reliability. New Glenn hasn't flown yet. Blue Origin can talk about orbital data centers, but SpaceX can actually execute them.

Sam Altman and Stoke Space

Sam Altman, CEO of OpenAI, recognized a different angle on the same problem. OpenAI needs computational power. Lots of it. Altman has been exploring a partnership with Stoke Space, a relatively young rocket company trying to develop a reusable orbital rocket.

The idea isn't to build a data center in space (at least not explicitly), but to create infrastructure that can support one. More fundamentally, it's about not being dependent on SpaceX for launch services. If Altman could control his own access to space, he'd have more leverage and less dependency.

This reveals something important about the orbital data center race: it's not just about computation. It's about independence. Every major AI player wants to avoid depending on Elon Musk. The problem is, Musk controls the only reliable, cost-effective way to get to orbit right now. Whoever can solve that problem gets leverage over everyone else.

The Technical Challenge: Building a Data Center in Space

Talking about orbital data centers is easy. Building one is absurdly difficult. Let's walk through the actual engineering challenges.

Launch and Deployment

First, you need to get hardware to orbit. SpaceX's Falcon Heavy can lift about 70,000 pounds to low Earth orbit. A typical data center might weigh millions of pounds. You'd need hundreds of launches to get everything up there. That's doable but expensive. SpaceX would be launching for itself, which creates an interesting conflict of interest (higher launch prices = higher revenue for SpaceX, higher costs for the data center), but it's still achievable.

More complex: assembling the data center in orbit. Individual components arrive on separate rockets. They need to be docked together, connected, tested. This requires either robotic systems or astronauts. SpaceX is developing Starship, which could eventually carry people, but that technology remains unproven. Robotic assembly is more realistic in the near term but requires developing new capabilities.

Thermal Management

As mentioned earlier, cooling in space is theoretically elegant but practically complex. Computer hardware generates heat. That heat needs to go somewhere. In space, heat dissipates through radiation. But you need to design the entire system around radiative cooling from the ground up. Radiators need to point toward empty space. Heat pipes need to move thermal energy efficiently. The whole system needs to be optimized for an environment humans have never built a data center in.

Malfunction becomes catastrophic. On Earth, if a cooling system fails, you power down the data center, fix the problem, power back up. In orbit, if your thermal system fails, your hardware burns up or shuts down, and you can't easily access it to fix it. You'd need to launch a repair mission. That's expensive and slow.

Power Generation and Distribution

Solar panels provide power. But solar panels degrade over time, especially in space where they're exposed to radiation and micrometeorites. You'd need to replace them periodically. You'd need redundancy. If one solar panel fails, others need to cover the load. The power distribution system needs to be reliable and efficient. Power conditioning, voltage regulation, distribution to thousands of individual servers. It all needs to work perfectly in an environment where maintenance is nearly impossible.

Wireless power transmission from Earth is another option being explored. Beam power from ground-based lasers or microwave transmitters to space-based receivers. This is even more experimental than radiative cooling. It works in theory. Whether it works at the scale required for a data center is completely unknown.

Redundancy and Reliability

Data centers on Earth have multiple redundancies. Multiple power supplies, multiple cooling systems, multiple network connections. You can take equipment offline for maintenance and repair. In orbit, you don't have that luxury. You can't easily replace a failed server. You can't easily upgrade to new hardware. Everything needs to be designed with failure in mind, with multiple backups and graceful degradation.

Data center customers expect "99.99% uptime" or better. That's 52 minutes of downtime per year. In orbit, achieving that with current technology seems nearly impossible. You'd need incredible reliability, redundancy, and probably some way to quickly replace failed components.

Network Connectivity

A data center in orbit needs to talk to the Internet. That means satellite links or laser links to ground stations. SpaceX's Starlink satellite network could theoretically handle this. But there are limits on bandwidth. The latency through a satellite link adds delay. Multiple round trips (user to ground station, ground station to data center, back through satellite, back to user) add up quickly.

These problems are solvable, but they're real. They're the reason nobody's done this before. SpaceX claims to have made some kind of breakthrough last year, but the company hasn't revealed what that is. That's suspicious. Either the breakthrough is extremely valuable (worth keeping secret), or it's not that impressive (better to keep quiet and let expectations build).

Google's IPO raised

The x AI Angle: Why Musk Needs Both Companies

This brings us to the real reason Musk is pursuing this aggressively: xAI needs a competitive edge, and orbital data centers could provide it.

xAI is behind OpenAI in virtually every metric that matters. OpenAI has more funding, more capable models, more users, more revenue, more market dominance. xAI released Grok, which is functional but not state-of-the-art. It's losing the race.

Musk could solve this by dumping more money into xAI. He could hire better researchers, acquire smaller AI companies, build bigger models. But that just means fighting OpenAI on OpenAI's turf. That means competing on research, on engineering talent, on raw computational resources.

Orbital data centers offer a different approach: competing on infrastructure. If SpaceX can build cheap orbital data centers, xAI gets cost advantages in training and running large models. If orbital data centers work as theorized, they might offer latency advantages, thermal advantages, power advantages. xAI could run models that competitors can't afford to run. It could run faster inference. It could train models more cheaply.

More speculatively, orbital data centers could enable new types of AI systems. Real-time, low-latency AI running on edge devices connected to orbital infrastructure. Global AI services with inherent redundancy and resilience. Entirely new business models we haven't imagined yet.

From this perspective, the IPO isn't about SpaceX at all. It's about xAI. The IPO is the financing mechanism to build infrastructure that benefits xAI. SpaceX becomes a subsidiary that supports the parent company's (Musk's) bigger AI ambitions.

This is how modern tech monopolies work. Vertical integration. Control of the supply chain. One company makes the infrastructure, another company uses it, both companies benefit, competitors get squeezed.

The Environmental Argument: From Bad to Worse?

Here's where things get complicated. The entire pitch for orbital data centers includes environmental benefits. No water consumption. No grid strain. No land use. Clean power from the sun.

But there's a massive asterisk there: getting the hardware to orbit requires rockets. Rockets burn fuel. Falcon 9 launches produce carbon emissions. SpaceX claims Falcon 9 is relatively efficient compared to other rockets, but it's still rocket propulsion. A single Falcon 9 launch produces roughly 400-500 tons of CO2.

To build an orbital data center, you'd need hundreds of launches. That's potentially hundreds of thousands of tons of CO2 just to get the hardware up there. Then you'd need ongoing launches for maintenance, repair, and upgrades. And then you need to deorbit the data center at end of life, which probably requires more launches.

Environmentalists have pointed out that this is greenwashing. The orbital data center appears clean because the carbon emissions happen during launch, not during operation. But the total carbon footprint could easily exceed that of a ground-based data center.

Musk's response is probably that the carbon can be offset. SpaceX is developing vehicles powered by methane, which is renewable methane produced from captured carbon. Eventually, rocket launches could be carbon-neutral. But that's a future technology. Right now, launching an orbital data center would produce enormous amounts of carbon.

The water argument is more compelling. Data centers use staggering amounts of water. Microsoft's data center in Wisconsin uses 1.7 million gallons per day. An orbital data center would use zero. If we're actually facing water scarcity in many parts of the world, that's genuinely significant.

But the water concern doesn't apply everywhere. Water scarcity is regional. Building a data center in water-rich regions doesn't create the same environmental conflict. The obsession with orbital data centers might obscure simpler solutions: building data centers in places with abundant water and clean energy.

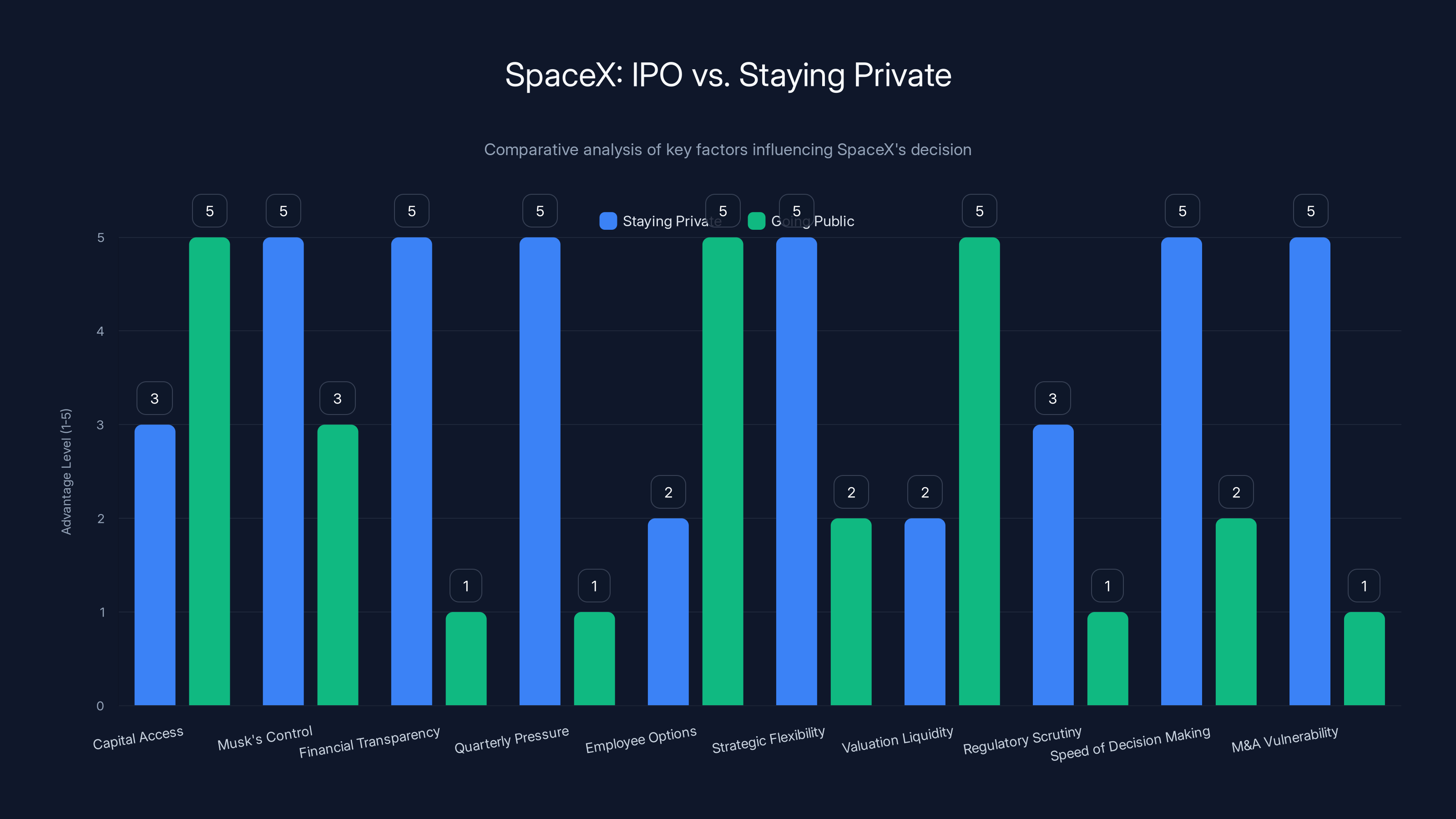

The chart compares SpaceX's potential advantages of staying private versus going public. While staying private offers more control and flexibility, going public provides unmatched capital access. (Estimated data)

Investment Implications: What IPO Means for Different Stakeholders

SpaceX going public would be one of the biggest IPOs in tech history. The company is probably worth well north of

Existing Investors

Current SpaceX investors (venture capital firms, sovereign wealth funds, and Musk himself) would see valuations in black and white. Right now, SpaceX's value is whatever the most recent funding round said it was. After an IPO, the market decides. If the stock pops, those investors make massive returns. If it doesn't, they're disappointed.

Musk is probably the biggest beneficiary. He owns a majority stake in SpaceX (around 50%). An IPO that values the company at

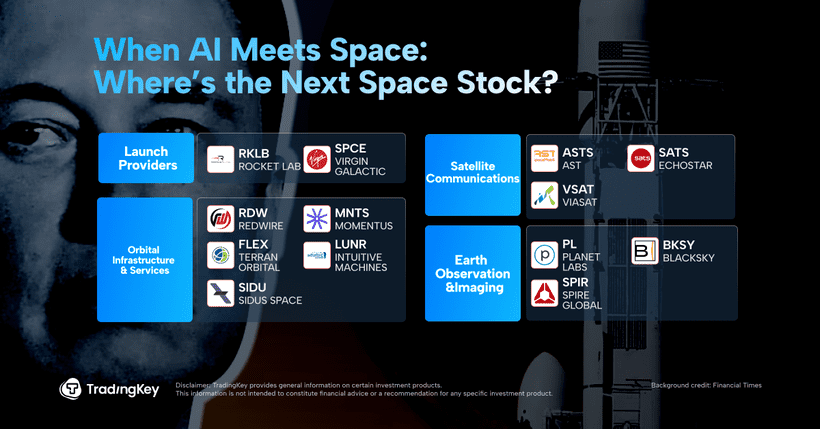

The Broader Space Industry

A SpaceX IPO would validate the space industry as a venture class. Right now, space companies are niche. Blue Origin, Rocket Lab, Relativity Space, and dozens of others exist, but they're not public companies. An IPO from SpaceX, the most successful space company ever built, would say: space is a legitimate industry, worth tracking as a separate sector.

That would unleash capital. It would make it easier for other space companies to raise money. It would create competition. It would probably drive innovation faster than we'd see otherwise. And it would probably drive down launch costs even further, making space more accessible to everyone.

Government Space Programs

NASA and other government space agencies would face an interesting situation. SpaceX would be a public company with quarterly earnings pressure. That could push SpaceX to prioritize profitable missions over high-risk exploration missions. On the other hand, it might push SpaceX to innovate faster to beat competitors.

The net effect is unclear. Public companies are hungry for revenue. Space exploration doesn't pay. Satellite launches do. Data center launches would. Government scientists might find it harder to get access to SpaceX's launch infrastructure if data center missions are more profitable.

Customers and Users

For Starlink customers, a SpaceX IPO probably doesn't change much. For data center customers (assuming this goes through), pricing would probably reflect the company's need to generate shareholder returns. That might mean higher prices than if SpaceX remained private and Musk could subsidize the business with profits from launches.

The Timeline: July 2025 and the Race Against Google

According to reporting, Musk wants to complete an IPO by July 2025. That's ambitious. That's less than a year away (from the time of reporting). Preparing a company for IPO typically takes 6-12 months minimum. You need audits, SEC filings, banker selection, roadshows, legal work.

For a company as unusual as SpaceX, with operations in space and military/government contracts, the process could be even longer. The SEC might want extra scrutiny. DoD might have concerns about a space company going public. Other nations might object to SpaceX having access to additional capital.

The July timeline probably won't hold. It might slip to late 2025, or even 2026. But the target date reveals the urgency. Musk wants to move fast. Why the rush?

Google's announced timeline for orbital data center test launches is 2027. If Musk wants to beat Google to having an operational orbital data center, he needs to start spending capital now. The IPO funding lets him do that. The earlier he goes public, the earlier he can start spending, the earlier he can claim dominance in orbital infrastructure.

It's a race. And in tech races, whoever gets there first often wins, even if later competitors build better products.

AI data centers and model training consume energy comparable to mid-sized cities, highlighting the strain on power grids. Estimated data.

Technical Breakthroughs: What Space X Claims to Have Solved

Wall Street Journal reporting indicated that SpaceX made some kind of breakthrough related to orbital data centers last year. The company has been cagey about what this is.

Speculation ranges across several possibilities. One suggestion is that SpaceX figured out how to do on-orbit assembly more efficiently. Maybe they developed robotic systems that can dock components and establish data connections autonomously. That would reduce the need for astronauts or expensive launch complexity.

Another possibility is a breakthrough in thermal management. Maybe SpaceX has designed radiators or heat pipes that work better than expected in vacuum. Maybe they've demonstrated that radiative cooling actually works at the scale needed for a data center.

A third possibility is power generation. Maybe SpaceX has developed better solar panels, or figured out wireless power transmission, or solved some other power-related challenge that seemed insurmountable.

Without more information, it's just guessing. But the fact that SpaceX claims to have solved something suggests they believe the rest of the engineering is doable. They wouldn't pursue an IPO unless they had confidence in the technical feasibility.

Of course, they also wouldn't reveal the breakthrough. If you're first mover in orbital data centers, you don't want competitors copying your innovations. Better to keep it secret, go public, raise capital, build the infrastructure, and dominate before anyone realizes what you've done.

Regulatory Considerations: Government Reactions and International Issues

SpaceX going public raises regulatory questions at multiple levels.

SEC Filings and Financial Transparency

SpaceX would need to disclose financial information. The company is remarkably secretive about its financial performance. Going public means ending that secrecy. Revenue, profit margins, customer lists, operational costs: all would become public. Some of that information is currently known through leaks and regulatory filings. Some of it is genuinely secret.

Musk probably hates the idea of that transparency. But it's the price of accessing public capital markets.

Defense Department Concerns

SpaceX has significant defense contracts. The company launches reconnaissance satellites for the NSA and NRO. It has contracts with the Space Force. SpaceX has access to classified information.

Making SpaceX public means some of that information could potentially be disclosed (though obviously classified information stays classified). It means foreign entities could own shares of SpaceX. It means the company would need to follow SEC rules and corporate governance rules that might conflict with national security interests.

The government could object. Congress could pass restrictions. This might slow down or complicate an IPO. Or it might not; SpaceX has proven pretty good at navigating regulatory complexity.

International Legal Issues

SpaceX launches from US territory. It launches satellites that operate globally. And increasingly, it would operate infrastructure in orbit that serves customers worldwide.

Orbital law is complicated. Officially, space is the common heritage of mankind, and no nation can claim sovereignty over orbit. But in practice, nations assert control. The US, Russia, China, and Europe all have space agencies and interests. An American company operating data centers in orbit creates international legal questions.

For instance, if a SpaceX orbital data center experiences a cyberattack, which nation's laws apply? If the data center collides with debris and damages another nation's satellite, which nation pays for it? These are genuinely unsettled questions.

Estimated data suggests financial transparency poses the highest challenge for SpaceX's IPO, followed by defense contracts and international legal issues.

Comparisons to Previous Tech Megadeals: Historical Context

SpaceX's IPO, if it happens, would be historically significant. But it's useful to look at comparable tech IPOs to understand scale.

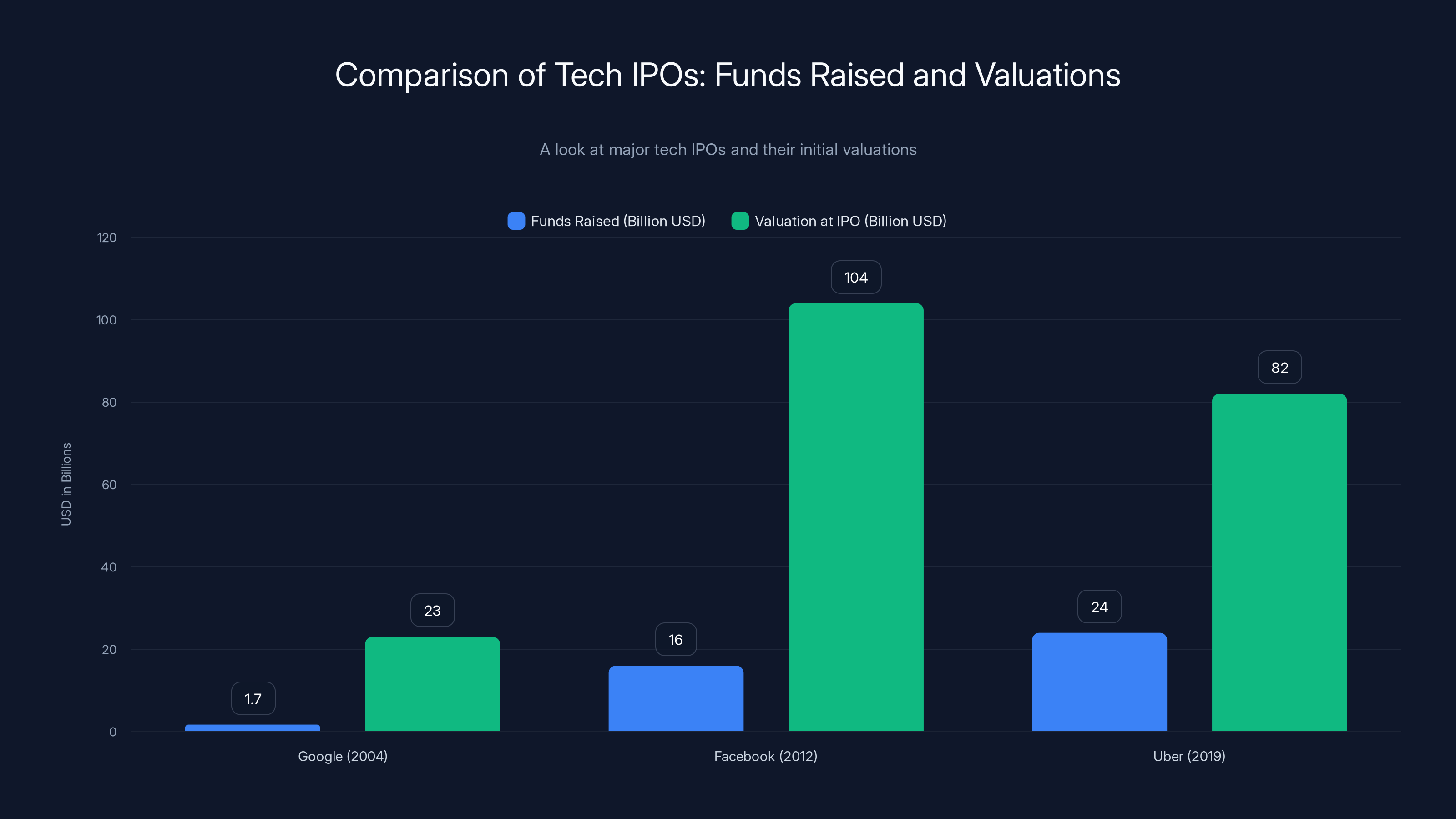

Google IPO (2004): Raised about

Facebook IPO (2012): Raised about

Uber IPO (2019): Raised about

The pattern here is interesting. Older tech IPOs (Google) have returned much more than newer ones (Uber). This could mean Google was undervalued, or it could mean the space for tech growth was bigger back then, or it could mean recent IPOs just haven't had time to mature.

SpaceX would be the largest IPO ever in the space industry by orders of magnitude. It would set a precedent. How the market values space infrastructure, data centers, and long-term moonshot projects would become clearer.

The Broader Implications: Where Space Goes Next

Beyond just SpaceX, an IPO and the pursuit of orbital data centers signals something larger about humanity's relationship with space.

For most of history, space was a government domain. Only nations with vast resources could build rockets and launch missions. The Space Race of the 1960s was about national pride and Cold War competition. Landing on the moon was geopolitical victory.

Private space is newer. SpaceX and Blue Origin pioneered commercial spaceflight. Satellite companies like Starlink and Amazon's Project Kuiper are commercializing orbit. Other companies are selling suborbital flights (Virgin Galactic, Blue Origin), mining operations (Axiom), and tourism.

Orbital data centers represent the next evolution: infrastructure in space that serves commercial purposes. Not exploration. Not tourism. Utility. Just like power plants, internet servers, and water treatment facilities serve us on Earth, data centers in orbit would serve us from space.

This changes the equation. It means space becomes economically essential, not just symbolically important. It means private companies will compete fiercely for orbital real estate and resources. It means governments will need to regulate activities in space in ways we haven't had to before.

It also means that control of space infrastructure becomes control of critical technology. Whoever provides data centers in orbit has enormous leverage over everyone else's AI capabilities. That's Musk's endgame, probably. Control the infrastructure, control the technology, control the future.

Whether that's good or bad depends on what Musk does with that power. History suggests billionaires with monopolies usually do something we regret. But that's a future concern. For now, the race is on.

How This Affects Other Space Companies

If SpaceX goes public and successfully pursues orbital data centers, what happens to competitors?

Blue Origin would face pressure to accelerate New Glenn development and announce its own data center plans. Bezos has the resources to compete, but SpaceX has a massive head start in execution.

Rocket Lab would probably position itself as a provider of targeted missions and components rather than compete head-to-head. The company could launch specialized sensors or repair modules to support orbital data centers.

Relativity Space, which uses 3D printing to manufacture rockets, could find opportunities in producing replacement components for orbital data centers. On-orbit manufacturing becomes more important if your data center is too far away to easily service.

Planetary Labs and other Earth observation companies might find reduced launch prices and more available launch capacity if SpaceX is busy with its own data center launches. Or they might find less capacity available if SpaceX prioritizes its own missions. Either way, market dynamics shift.

Smaller launch providers like Axiom, Axiom Space (not the same as Axiom), and Orbcomm might find new opportunities in supporting orbital data center infrastructure. Or they might get squeezed by SpaceX's dominance.

The net effect is consolidation pressure. SpaceX going public makes it a bigger, better-capitalized competitor. That makes it harder for smaller players. Some consolidate with bigger partners. Some find niche markets. Some fail.

Challenges Musk Will Face Post-IPO

If SpaceX goes public, Musk immediately faces new constraints.

Quarterly Earnings Pressure: This is the big one. Publicly traded companies need to report earnings every quarter. Analysts set expectations. Beat expectations and stock rises. Miss expectations and stock falls. This pressure could push SpaceX toward short-term profit maximization rather than long-term dreams.

Board of Directors: Musk would need to appoint a board. That board would have fiduciary duty to shareholders. They could potentially override Musk on major decisions. Musk hates answering to boards (see: his conflicts with Twitter's board before he owned it). This is going to be a constant friction point.

Employee Equity: SpaceX employee options would suddenly become valuable. Employees with vested options could cash out. That might reduce long-term motivation. Or it might attract new talent. Either way, the dynamics change.

Shareholder Activism: Once there are public shareholders, activist investors could emerge. They could push for different strategies, higher dividends, different management. SpaceX might be targeted by groups pushing for environmental responsibility, or labor rights, or other causes.

Vulnerability to Acquisition: A public SpaceX could theoretically be acquired. Not likely, given Musk's control stake, but possible. That possibility creates pressure to maintain stock price and profitability.

The x AI Connection: Potential Conflicts of Interest

Here's a potential issue nobody's fully discussed: if SpaceX becomes public, how do you avoid conflicts of interest with xAI?

Suppose SpaceX launches its orbital data center for a 50% cost premium compared to competitors. Suppose SpaceX charges xAI a special price because Musk runs both companies. Public shareholders would rightly complain. They'd say SpaceX is subsidizing a competitor's private company. That's not allowed under corporate law.

Musk could solve this by taking xAI public too. Then both companies are public, competing fairly (theoretically). But that means subjecting xAI to the same quarterly earnings pressure and board oversight that SpaceX faces.

Alternatively, Musk could restructure so SpaceX is completely independent of xAI. But then xAI loses access to preferential data center pricing. That defeats the whole purpose.

This is a real constraint that nobody talks about much. Going public solves the capital problem but creates governance problems that might prevent Musk from actually using the orbital infrastructure as strategically as he wants.

Comparison Table: Space X IPO vs. Staying Private

Let's look at the actual trade-offs:

| Factor | Staying Private | Going Public |

|---|---|---|

| Capital Access | Limited to private investors | Unlimited from public markets |

| Musk's Control | Complete | Diluted but probably majority |

| Financial Transparency | Secret | Full disclosure |

| Quarterly Pressure | None | Intense |

| Employee Options | Hard to deploy | Easy to deploy |

| Strategic Flexibility | Maximum | Constrained by fiduciary duty |

| Valuation Liquidity | Illiquid (hard to sell) | Highly liquid |

| Regulatory Scrutiny | Moderate | Intense |

| Speed of Decision Making | Fast | Slow (board approval needed) |

| M&A Vulnerability | Protected | Exposed |

Looking at this table, it's clear why Musk might be hesitant. But the capital access advantage is huge. Raising $50-100 billion on public markets is simply impossible as a private company. If orbital data centers require that much spending, the IPO becomes necessary.

What Could Go Wrong: Risks to Watch

Orbital data centers are speculative. A lot could go wrong.

Technical failure: The radiative cooling might not work as expected. Thermal management could prove harder than anticipated. Power generation from space might face unforeseen challenges. On-orbit assembly might be unreliable. If the core technology doesn't work, the entire premise collapses.

Economic failure: Even if the technology works, it might be too expensive to operate. Launch costs might not come down enough. Maintenance and repair might be so expensive that ground-based data centers remain cheaper. The whole economic case could evaporate.

Competition: Blue Origin might develop its own orbital data center. Google might solve it first. By the time SpaceX's is operational, competitors might already own the market.

Regulatory rejection: Governments might prohibit data center operations in orbit. Environmental groups might mount opposition. International pressure might force restrictions. This is less likely than technical failure, but possible.

Market downturn: If the IPO happens during an economic recession or a tech sector pullback, SpaceX stock could crater. That affects both the company's valuation and its ability to raise future capital.

Catastrophic failure: A launch accident that destroys expensive hardware. A collision with debris in orbit. A cyberattack on orbital data centers. These could set back the project by years or decades.

None of these are certainties. But they're risks worth considering before investing.

The Long-Term Vision: Space as Infrastructure

If orbital data centers succeed, what's next?

Solar power stations in orbit beaming energy to Earth. Manufacturing facilities in microgravity producing medicines or materials impossible to make on the ground. Mining asteroids for precious metals and rare earth elements. Hotels and tourism destinations. Medical facilities designed to use space conditions for treatment. The list goes on.

Each of these is speculative. Some might never happen. But if orbital data centers prove that putting infrastructure in space is economically viable, they open the door to everything else.

Musk's vision of humanity becoming a multiplanetary species might actually happen, but not in the way he originally imagined. Instead of Mars colonies, it might be orbital infrastructure first, then lunar bases, then eventually Mars. The path is economics-driven rather than exploration-driven.

From a civilization perspective, that's interesting. It means the next major frontier isn't Mars anymore. It's space-based infrastructure serving Earth. And the first company to dominate that infrastructure probably dominates a huge chunk of the global economy.

That's what SpaceX is positioning for. That's what the IPO is about. That's why it matters.

FAQ

What is Space X's reasoning for going public?

SpaceX has spent nearly two decades promising an IPO would only happen after establishing a human presence on Mars. That timeline has repeatedly slipped, and Mars remains a distant goal. The company now wants to pursue orbital data centers for AI companies, which requires billions of dollars in capital that only a public IPO can provide efficiently. Additionally, the IPO would help Musk's xAI startup compete more effectively in the AI industry by providing access to space-based computational infrastructure.

How would orbital data centers actually work in space?

Orbital data centers would rely on space-based advantages that ground facilities can't access. Solar panels in orbit capture uninterrupted sunlight to generate power without grid dependency. Computer heat dissipates through radiation directly into space's vacuum, eliminating expensive cooling systems that consume massive amounts of water on Earth. For certain applications, low Earth orbit proximity could reduce latency. However, the technical challenges remain enormous: launching equipment to orbit, assembling systems thousands of miles above Earth, managing reliability when maintenance is impossible, and transmitting data back to ground networks all present complex engineering problems.

What are the environmental benefits of orbital data centers?

Orbital data centers would eliminate water consumption (data centers currently use millions of gallons daily for cooling), reduce strain on electrical grids (particularly critical as AI demands grow), and operate on solar power with no local environmental impact. However, a major caveat exists: launching hardware to orbit requires hundreds of rocket launches that produce significant carbon emissions. Whether the operational benefits outweigh the launch-phase emissions remains debated, though SpaceX argues that transitioning to renewable rocket fuel could eventually make the process carbon-neutral.

Who else is pursuing orbital data centers?

Google has announced plans for orbital data center test launches scheduled for 2027, though the company lacks its own rocket company and depends on external launch providers. Jeff Bezos and Blue Origin have suggested orbital data centers make strategic sense. OpenAI's Sam Altman has explored partnerships with Stoke Space, a rocket company, to reduce dependency on SpaceX for launch services. None of these competitors are as far along as SpaceX, which already operates the world's most reliable rocket and has potentially solved critical technical challenges.

How does this IPO benefit x AI?

Musk runs both SpaceX and xAI. If SpaceX builds orbital data centers with cost advantages from renewable solar power, superior thermal management, and reduced water needs, xAI could access this infrastructure at preferential pricing or terms. This would give xAI computational advantages over competitors like OpenAI and Google, potentially allowing larger model training, faster inference, and lower operational costs. It's a form of vertical integration where infrastructure control translates into competitive advantage in AI development.

What's the timeline for Space X's IPO?

Musk reportedly wants to complete the IPO by July 2025, though this timeline may slip given the complexity involved. The urgency relates to Google's announced 2027 timeline for orbital data center test launches. By going public and raising capital quickly, SpaceX can begin development sooner and potentially achieve operational orbital infrastructure before competitors. The SEC approval process, combined with national security reviews required for a space company with defense contracts, could extend the timeline to late 2025 or 2026.

What technical breakthrough did Space X claim to achieve?

The Wall Street Journal reported that SpaceX made a breakthrough related to orbital data centers last year, but the company hasn't disclosed specifics. Speculation centers on improved on-orbit assembly techniques using robotics, major advances in radiative cooling systems that function at data center scale, innovations in wireless power transmission, or breakthroughs in space-rated solar panel efficiency. The vagueness is intentional; SpaceX won't reveal proprietary advantages before going public and raising capital.

What happens to Space X's original Mars mission after going public?

Mars colonization likely becomes lower priority than orbital data center development, at least in the near term. Public companies face quarterly earnings pressure that private companies don't. Profitable missions (commercial launches, data center operations) will be prioritized over long-term exploration projects that generate revenue losses. This doesn't mean Mars work stops completely, but it probably faces reduced resources and attention. Starship development continues because SpaceX uses Starship for its own launches, but purely exploratory missions are deprioritized in favor of commercial revenue generation.

What are the main risks to orbital data center success?

Technical risks include radiative cooling not functioning as designed at required scale, thermal management complexity exceeding predictions, power generation falling short, and on-orbit assembly proving unreliable. Economic risks involve launch costs remaining too high to make orbital operations cheaper than Earth-based facilities, maintenance expenses being prohibitive, and the whole concept being more expensive than projected. Competitive risks mean Google or Blue Origin might develop superior solutions first. Market risks include recession impacting the IPO timing, stock market dynamics, or demand for AI services declining. Regulatory risks could involve government restrictions on space-based data centers.

Conclusion: The Next Era of Space Infrastructure

Elon Musk's reported push to take SpaceX public represents more than just a corporate restructuring. It signals that space is transforming from a domain of government exploration and Musk's personal moonshot ambitions into critical infrastructure for earthly commerce and technology competition.

For eighteen years, Musk promised that SpaceX would remain private until humanity had established a foothold on Mars. That promise reflected a philosophical stance: long-term vision matters more than quarterly earnings. But the AI revolution changed the calculation. Suddenly, controlling computational infrastructure in orbit became more economically valuable than pursuing Mars colonization. The timeline shifted.

An IPO would solve SpaceX's capital problem, raising tens of billions of dollars necessary to develop orbital data centers. It would validate the space industry as a venture sector. It would pressure SpaceX toward short-term profitability over long-term exploration. It would expose Musk to board oversight and shareholder activism. It would create regulatory complications and potentially conflicts of interest with xAI.

But the capital advantage is massive. And if orbital data centers work at all, they represent an enormous business opportunity. Control orbital infrastructure and you control a critical piece of global AI development. Whoever builds the first operational orbital data center gets first-mover advantage. That's probably worth the constraints of being public.

The race is on. Google targets 2027. Blue Origin is watching. OpenAI is finding alternatives. And Musk wants to complete a SpaceX IPO by July 2025 to fund a project that could fundamentally reshape how humanity handles computation.

Whether this succeeds or fails, it represents a genuinely novel moment in human history. For the first time, we're seriously building infrastructure in space for practical earthly purposes, not for exploration or symbolism. Space is becoming utility. Infrastructure follows investment. And investment follows whoever can provide compelling returns.

SpaceX going public is just the beginning. The real story is what happens next.

Key Takeaways

- Elon Musk is pushing SpaceX toward a public IPO by July 2025, abandoning the Mars colonization requirement that previously blocked going public

- The real driver is orbital AI data centers, which would provide computational advantages through solar power, radiative cooling, and reduced environmental impact

- SpaceX claims to have solved a critical technical breakthrough, though details remain secret to preserve competitive advantage

- Google targets 2027 for orbital data center tests, creating urgency for SpaceX to go public and fund development before competitors gain ground

- Musk's control of both SpaceX and xAI creates vertical integration opportunities but governance complications if SpaceX becomes public

- An IPO of $150-200 billion would be the largest space industry IPO ever, validating space infrastructure as a venture sector

- Technical challenges remain enormous: on-orbit assembly, radiative cooling at scale, power generation, maintenance in space, and data transmission back to Earth

- Environmental benefits include zero water consumption and reduced grid strain, though launch emissions must be weighed against operational savings

Related Articles

- Tesla's Dojo3 Space-Based AI Compute: What It Means [2026]

- How Grok's Deepfake Crisis Exposed AI Safety's Critical Failure [2025]

- Nvidia Vera Rubin AI Computing Platform at CES 2026 [2025]

- Haven-1 Commercial Space Station: Assembly, Launch Timeline & Future Impact 2027

- Dr. Gladys West: The Hidden Mathematician Behind GPS [2025]

- Threads Overtakes X on Mobile: What This Means for Social Media [2025]

![SpaceX IPO 2025: Why Elon Musk Wants Data Centers in Space [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/spacex-ipo-2025-why-elon-musk-wants-data-centers-in-space-20/image-1-1769017184676.png)