NASA's SLS Rocket Problem: Why the Costliest Booster Flies So Slowly

Some problems are so obvious that ignoring them becomes its own kind of statement. NASA's Space Launch System rocket is one of those problems.

For over a decade, critics pointed at the same issue. The rocket was too expensive. It flew too rarely. The combination made every launch feel less like routine spaceflight and more like launching an experimental prototype. Yet NASA kept quiet about it, deflecting questions with technical jargon and budget updates. Then, in early 2025, something shifted.

After the Artemis II mission's latest delay caused by yet another hydrogen leak at the ground interface, NASA Administrator Jared Isaacman did something remarkable. He acknowledged reality.

"The flight rate is the lowest of any NASA-designed vehicle, and that should be a topic of discussion," Isaacman posted online. It sounds like a small thing. It's not. It's an admission that the rocket's core architecture contains a fundamental design flaw that no amount of engineering can fix without rebuilding the entire system.

But what led to this moment? How did the most powerful rocket ever built by NASA become trapped in a cycle of delays, cost overruns, and barely-concealed disappointment? And what does it mean for the future of human spaceflight?

TL; DR

- The SLS costs over $30 billion and has been in development for 15 years with just one successful launch to date

- Hydrogen leak problems persist at ground interfaces despite three years of supposed fixes between Artemis I and Artemis II missions

- Flight rate is catastrophically low at roughly one mission every 3-5 years, making operations expensive and risky

- NASA finally admitted the problem publicly after repeated delays forced the conversation beyond internal discussions

- Commercial alternatives exist but political commitment to SLS remains strong despite performance and cost concerns

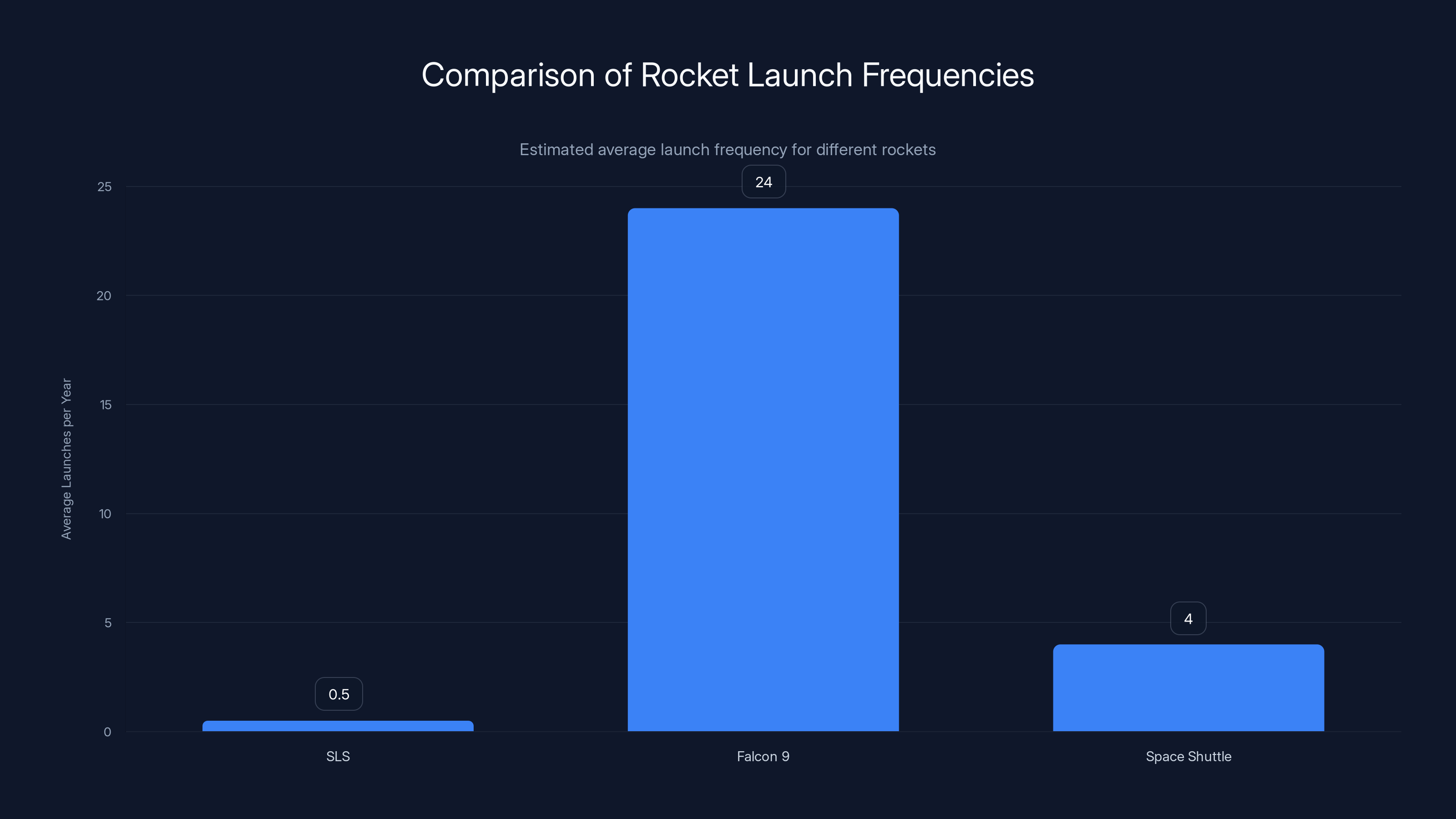

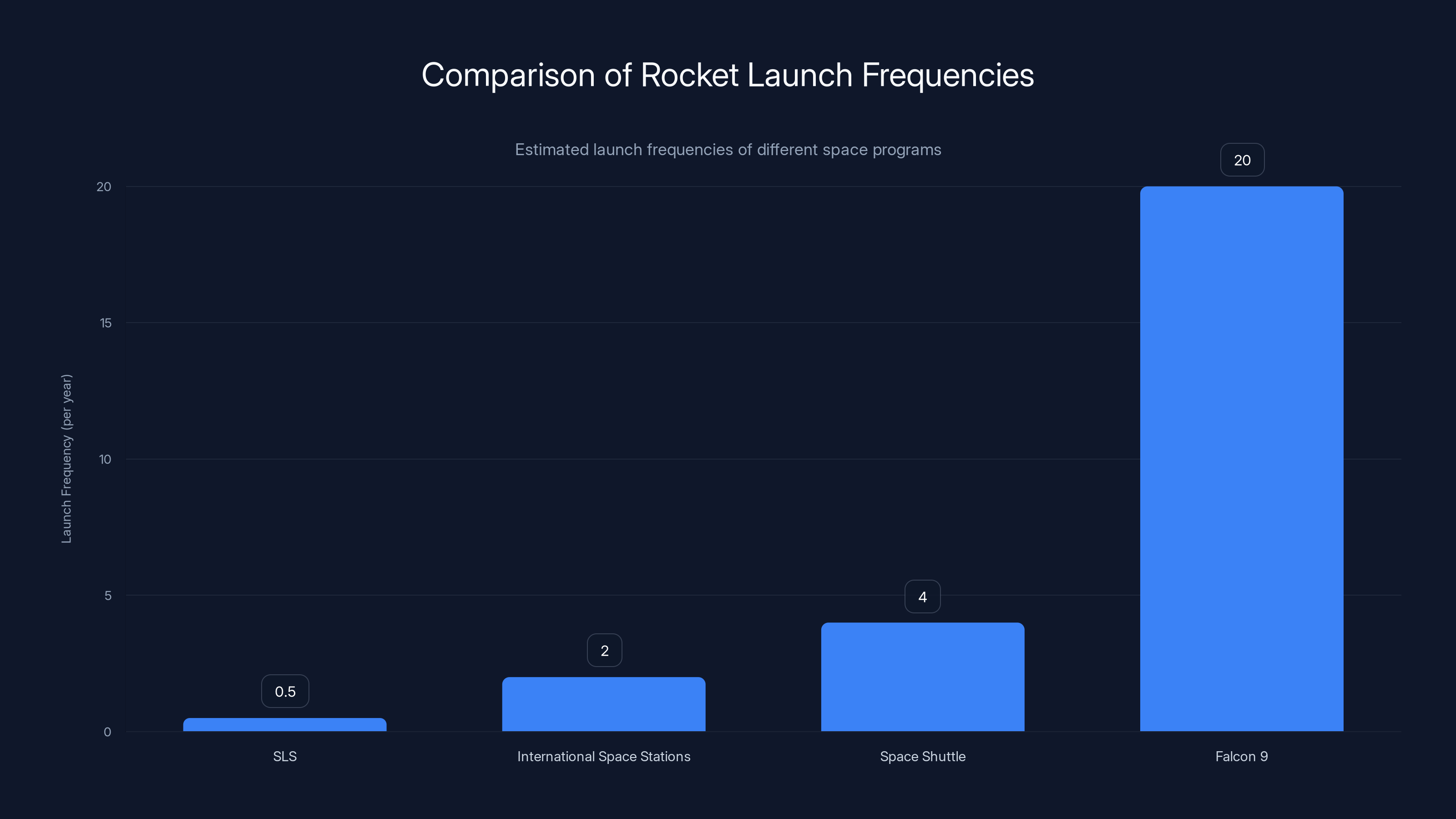

The SLS has a significantly lower flight rate, estimated at one launch every 2-5 years, compared to Falcon 9's multiple monthly launches. Estimated data.

The Arithmetic of Disappointment: Tracking SLS Costs and Timeline

Numbers tell stories, and the SLS story starts with a really big one. Thirty billion dollars. That's the amount American taxpayers have invested in the Space Launch System since 2011, when NASA decided to retire the Space Shuttle and build something new.

Think about what that means. Thirty billion dollars could fund roughly 150,000 teachers for a year at the median U.S. salary, as reported by Idaho Ed News. It could house about 400,000 homeless individuals for twelve months, according to California's recent data. It could build 600 miles of modern highway. Instead, it bought a single rocket that has achieved one successful flight.

That one flight happened on November 22, 2022. That's over three years ago. In commercial spaceflight, that would constitute a catastrophic failure rate. A company launching once every 1,095 days would be out of business. Yet for NASA's signature deep-space rocket, it's considered normal.

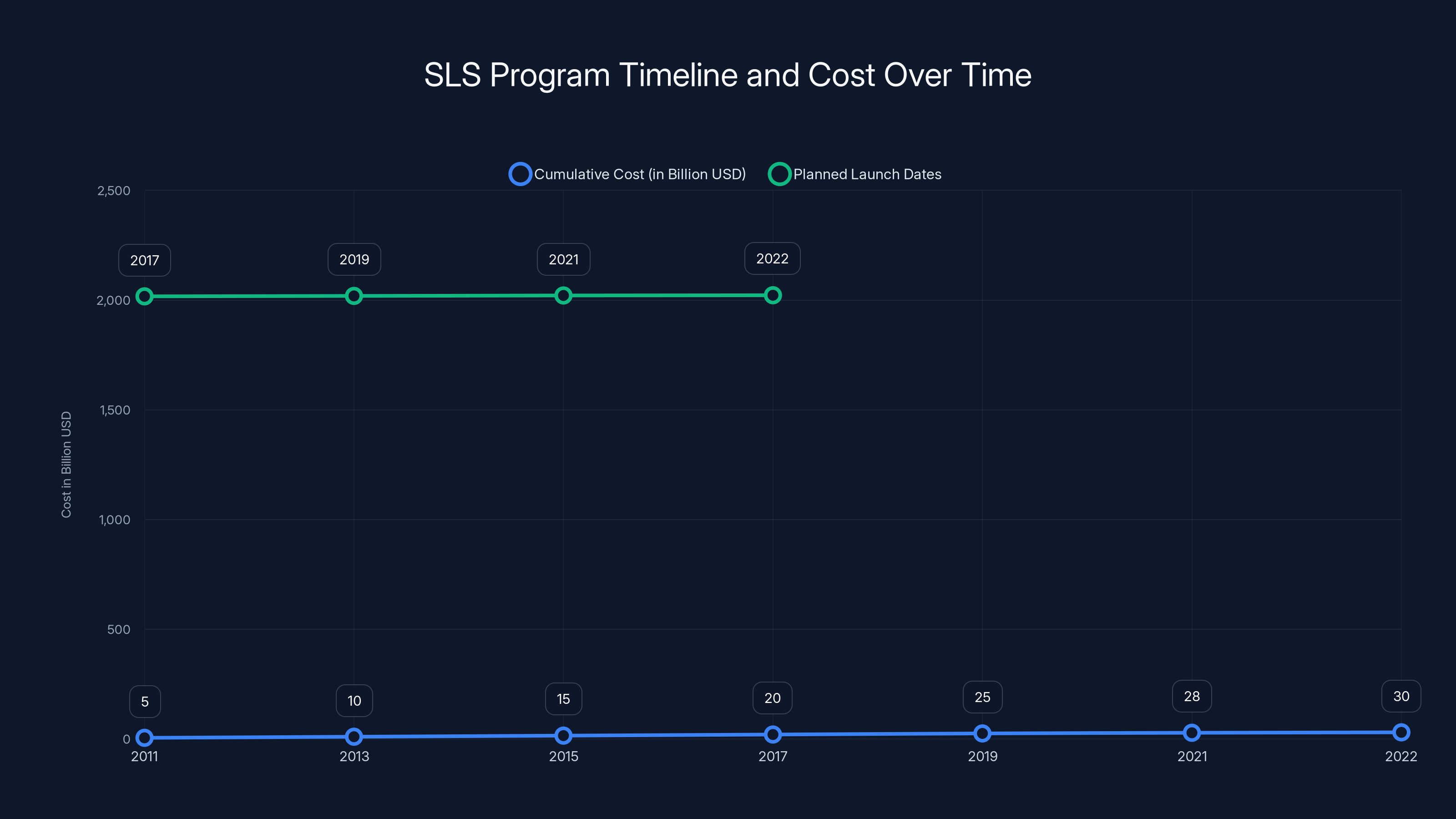

The program officially began around 2011, though NASA had been conceptualizing heavy-lift vehicle designs since the early 2000s. Originally called Ares V within the Constellation program, it was supposed to launch by 2017. Then 2019. Then 2021. The estimates kept moving, each delay accompanied by budget increases and technical challenges that everyone had supposedly already solved.

When Artemis I finally flew in 2022, it was supposed to demonstrate that the vehicle worked well enough for human flight. The mission was flawless from an operational standpoint. The rocket performed beautifully. But the path to the pad told a different story.

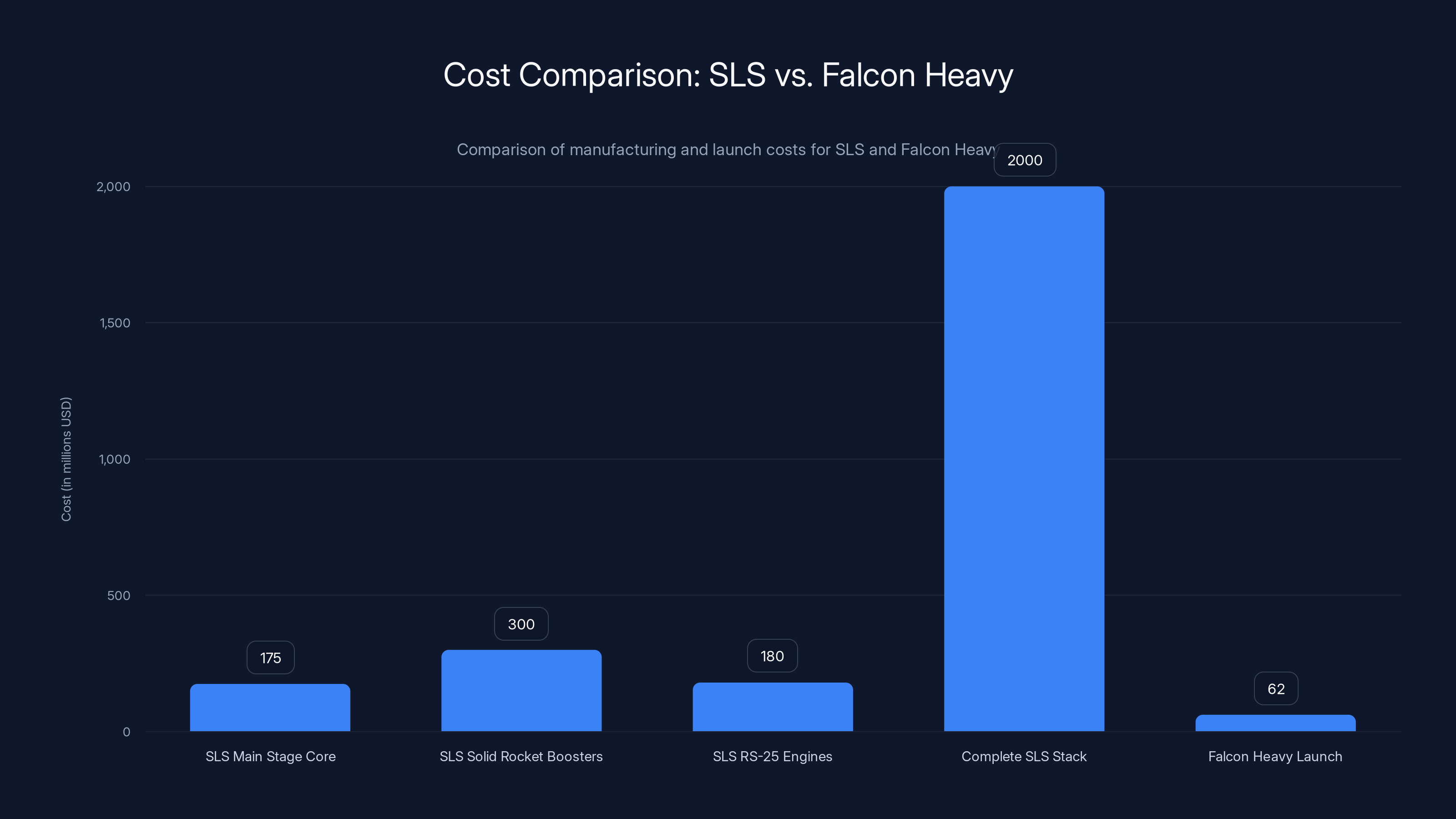

The SLS components and complete stack are significantly more expensive than a Falcon Heavy launch, highlighting the economic challenges NASA faces with hardware scarcity.

The Leak That Keeps On Leaking: Ground Systems and Hydrogen Physics

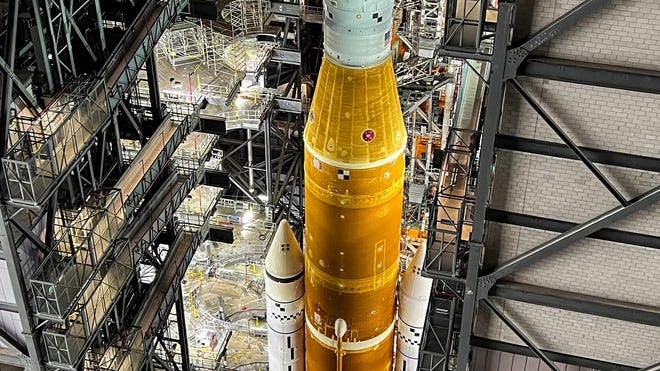

When NASA engineers rolled the Space Launch System to the launchpad in March 2022 for fueling tests, they expected a straightforward process. Fill the rocket with liquid hydrogen, perform checks, unfill it, repeat. Instead, they discovered a problem that would consume nearly four months and reveal something deeply troubling about the vehicle's design.

Liquid hydrogen is exotic stuff. At minus 253 degrees Celsius, it's far colder than anything most engineers work with on Earth. The molecule itself is tiny, just two atoms of hydrogen bound together. That small size means it leaks through gaps that would stop other liquids. It's also extremely energetic, which is why NASA wants it: the exhaust from burning hydrogen and oxygen produces tremendous thrust.

But that same energetic nature means hydrogen demands respect. Seal problems that might be minor with kerosene become critical with hydrogen. The interfaces where ground equipment connects to the flight vehicle are particularly tricky. These connections involve multiple seals, various materials, and thousands of small variables. When liquid hydrogen flows through, every imperfection becomes an opportunity for leakage.

NASA conducted wet dress rehearsal tests starting in March 2022. The first three tests were scrubbed before fueling was complete. Tests four and five had problems. Test six reached within 29 seconds of engine ignition before NASA aborted it. Test seven occurred in late August during what was nominally the first actual launch attempt. Still scrubbed. Test eight happened a week later. Also scrubbed. Only on test nine, in November 2022, did the vehicle actually take off.

Nine attempts. Seven months. Dozens of hydrogen leaks. Engineers working countless hours troubleshooting a problem that hadn't been solved during the design phase. The rocket flew, but the path to flight revealed cracks in the vehicle's architecture.

Then came the question that nobody wanted to ask: why hadn't this problem been fixed by now?

Three Years and Nothing Changes: The Artemis II Rehearsal Failure

NASA had three years between Artemis I's successful launch and the planned Artemis II mission. Three years to solve a hydrogen leak problem that had defined the previous launch campaign. Three years to improve ground systems, to test components more thoroughly, to understand why seals and valves kept failing.

When NASA rolled Artemis II to the pad in January 2025 and began its first wet dress rehearsal test, expectations were cautious optimism. The engineers had undoubtedly learned something. Surely the problem had been mitigated, if not eliminated.

Then the leak appeared. At the main hydrogen interface, the exact same location where problems had occurred on Artemis I. The leak wasn't catastrophic initially, but it was persistent. NASA tried standard mitigations. They reduced the hydrogen flow rate, letting the very cold liquid enter more slowly. They paused the flow, hoping seals would warm up and re-seat themselves. These techniques had worked during the Artemis I campaign. They worked again on Artemis II.

For several hours, the team kept pushing through troubleshooting procedures. They got the vehicle fully fueled. They began the countdown, running about four hours behind schedule. Everything seemed to be falling into place. Then, near the critical final stages of the countdown, the leak spiked again. Hydrogen started flowing through gaps more rapidly. The automatic abort sequence kicked in. The test ended at roughly T-minus 5 minutes.

March became the new target date for launch. More wet dress rehearsal tests would happen in the interim. Astronauts would wait. The moon would stay right where it was. Another delay added to a list that now stretched longer than many relationships.

What's remarkable isn't that the leak happened. It's that it happened at all. After three years of supposedly aggressive component-level testing, after engineers understanding exactly what they'd done wrong the first time, the problem persisted.

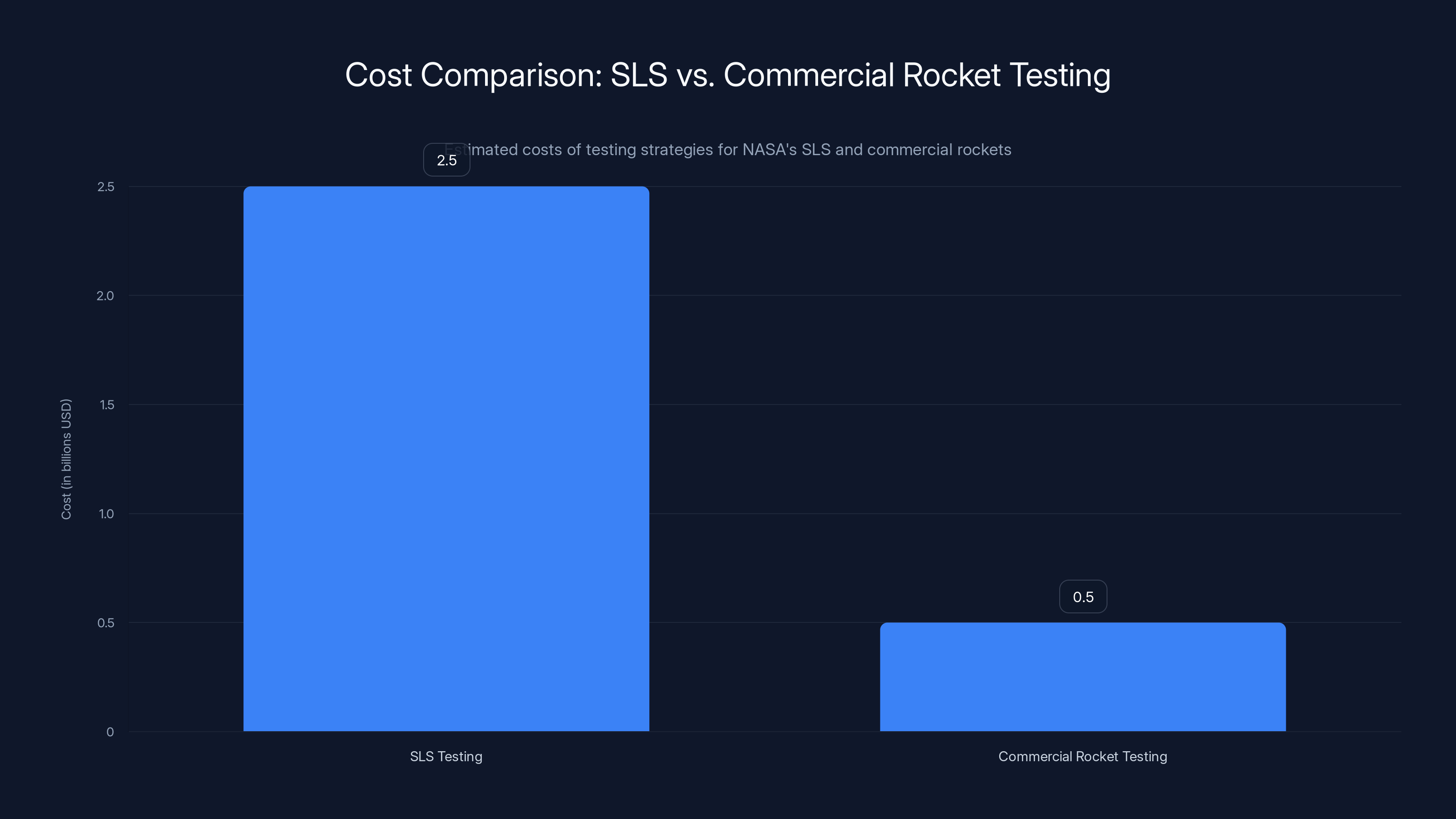

Estimated data shows that SLS testing is significantly more expensive than commercial rocket testing, primarily due to the high cost of building and testing full-scale hardware.

Why Three Years of Testing Didn't Solve This

When John Honeycutt, chair of the Artemis II Mission Management Team, was asked directly why the leak problem hadn't been solved, his answer was revealing. "After Artemis I, with the challenges we had with the leaks, we took a pretty aggressive approach to do some component-level testing with some of these valves and the seals," he said. They understood the behavior better now. They'd improved installation procedures on both the flight side and ground side interfaces.

Then he added something that cuts to the heart of the issue: "But on the ground we're pretty limited in how much realism we can put into the test."

This is the constraint that breaks the entire SLS architecture. Component-level testing means removing pieces and testing them in labs. It means running hydraulic simulations and reviewing design documents. It does not mean building duplicate hardware and repeatedly fueling it like you'll do on launch day. It doesn't mean practicing the exact procedure with the exact equipment at the exact location where missions actually happen.

Commercial rocketry solved this problem decades ago. Companies build test tanks and test stands specifically for practicing procedures. Space X maintains facilities dedicated to tanking tests. They fuel vehicles that never fly, just to understand how everything behaves under operational conditions. They run the same procedures dozens of times before flight, catching problems in environments where failures don't delay billion-dollar missions.

Why doesn't NASA do this with SLS? The answer is straightforward: money. A single SLS vehicle costs over

So instead, NASA chose an operational strategy that ensures every single test is high-stakes and every failure carries major consequences. This sounds backwards because it is backwards. It's an optimization for cost in a way that creates expense everywhere else.

The Flight Rate Problem: Why Occasional Flying Makes Everything Harder

The real issue isn't hydrogen. Hydrogen is solvable. The real issue is that SLS flies so infrequently that every launch becomes an experimental mission rather than an operational procedure.

Consider what happens with routine operations. When Space X launches a Falcon 9 rocket, ground crews follow established procedures they've executed hundreds of times. New procedures are tested extensively before being implemented. Engineers understand how the hardware behaves. Problems are rare because experience irons out the kinks.

With SLS, the situation is inverted. The crew rolling the vehicle to the pad for Artemis II hadn't done this since November 2022. The engineers conducting the wet dress test hadn't done this since Artemis I. The procedures had been reviewed, sure, but they hadn't been practiced. The team hadn't built the operational muscle memory that prevents mistakes.

When you're practiced, you catch small problems before they become big ones. When you're not practiced, you catch them during test failures.

NASA estimates SLS will launch roughly once every 2-3 years at best, if everything goes according to plan. That's slower than international space stations launch. It's slower than Space Shuttle launched during its most conservative operational periods. It's slower than just about any rocket in history with the possible exception of early Apollo hardware during development phases.

At that flight rate, mission costs explode. Infrastructure has to be maintained between flights. Teams have to be kept together and trained even when there's nothing to do. Contracts remain open for months between missions. This is expensive in ways that aren't always obvious in budget documents.

More importantly, at that flight rate, operational margins compress. Reliability improves through familiarity. You don't get familiarity from flying once every three years. Every launch becomes a learning experience. Every launch surface new problems that should have been caught during the extensive test campaign but weren't because you've never actually done the procedure before under real conditions.

NASA has understood this problem for over a decade. Critics pointed it out starting around 2015. The Space Shuttle, despite its flaws, flew about 5-6 times per year at its peak. Even the aging Space Shuttle program achieved a higher operational cadence than the newest, most advanced heavy-lift vehicle NASA has ever built.

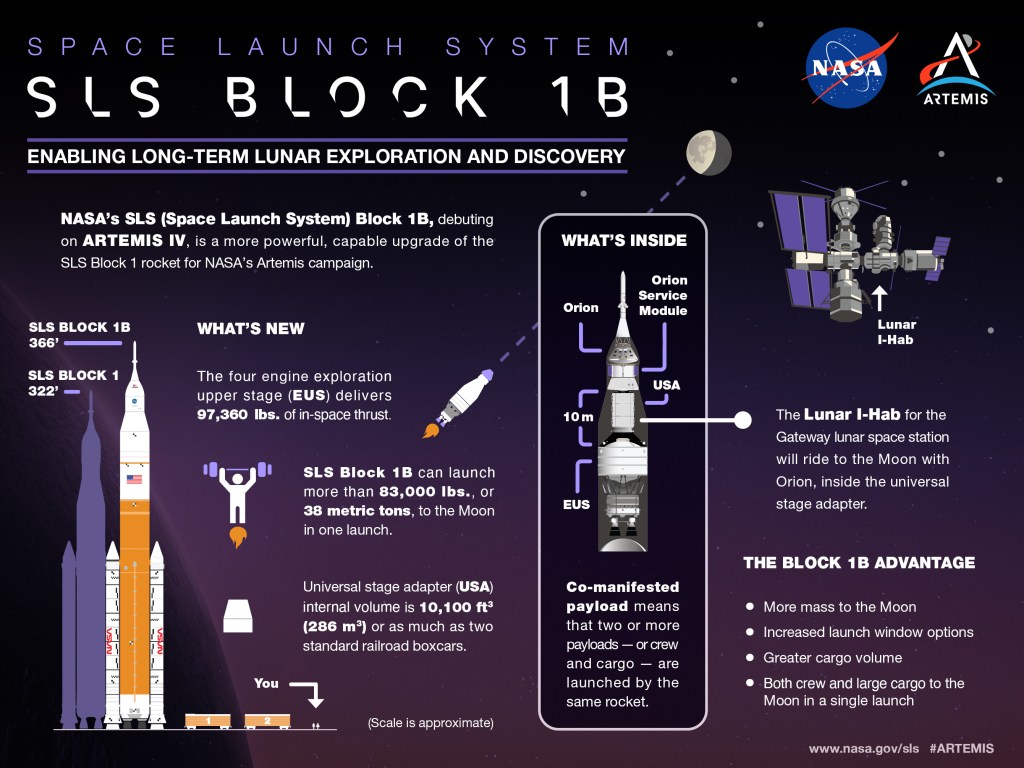

The SLS program has cost over $30 billion, taken 15 years, and achieved a low flight rate of one mission every 3-5 years, highlighting significant challenges. Estimated data.

The Hardware Poverty Problem: Why You Can't Build Test Articles

Behind the flight rate problem sits another, deeper issue: hardware scarcity. SLS components are manufactured by contractors scattered across the country. A single Main Stage Core, the central engine unit, costs around

A complete SLS stack runs over $2 billion. That's not an estimate. That's the actual cost to manufacture the hardware, not including launch operations, ground system development, or mission management.

For context, Space X charges $62 million for a Falcon Heavy launch, which is three times the lift capacity of SLS. The entire vehicle costs a few hundred million at most. The difference in cost per kilogram to orbit is so stark that it breaks economic models. SLS cannot be justified on price performance alone. It exists because Congress built it into law and NASA's budget, not because it makes financial sense.

Given that cost structure, NASA can't afford to build test hardware the way commercial programs do. You don't build duplicate billion-dollar vehicles to practice procedures. You test components, you run simulations, you review procedures. But you don't actually fuel and test the full stack except during mission-critical moments.

This is a design constraint that no amount of engineering can overcome. You either accept a lower flight rate, or you accept operational risk. NASA chose to accept operational risk, which is why we get hydrogen leaks at critical moments and teams scrambling to troubleshoot problems that should never have made it to the pad.

The solution would require either dramatically increasing SLS production to build more vehicles, which would cost tens of billions more, or fundamentally changing the rocket's architecture to be cheaper to manufacture. Neither option is politically viable. Building more SLS vehicles is unsustainable. Redesigning after 15 years and $30 billion invested is unthinkable.

So NASA is stuck with a system that's expensive to operate, slow to fly, and prone to problems because it doesn't accumulate operational experience.

The Politicization of Spaceflight: Why SLS Still Exists Despite Its Problems

Here's what's remarkable: NASA has alternatives. Space X's Falcon Heavy could lift Artemis-class payloads to lunar trajectory. Blue Origin is developing New Glenn, a heavy-lift vehicle with Artemis-compatible capabilities on a faster timeline. Other commercial providers are pursuing various heavy-lift approaches.

Yet SLS remains the official vehicle for Artemis, and Congress has written this mandate into law. Why? Because SLS is distributed across multiple Congressional districts in multiple states. Work happens in Utah (Solid Rocket Boosters), Louisiana (Main Engines), Mississippi (Booster assembly), Alabama (core stage assembly), and Florida (integration and launch). This geographic distribution means members from both parties have reasons to support continued funding.

It's political support masquerading as technical necessity. The rocket exists not because it's the best solution but because it was the easiest political solution 15 years ago. Now that legacy is costing taxpayers billions annually and delaying the return of humans to the moon.

NASA Administrator Isaacman's recent public acknowledgment of the flight rate problem is significant precisely because it breaks the taboo around saying that SLS might not be ideal. He didn't say the program should be cancelled. He just said the flight rate issue should be discussed. In NASA culture, where the agency has been united in defending SLS against criticism, this was genuinely noteworthy.

It suggests that even people deeply embedded in the system recognize the inefficiencies. Whether that translates into actual program changes remains to be seen. The momentum behind SLS is enormous, and scrapping a 15-year-old program with $30 billion invested would require something approaching a political earthquake.

The SLS program has seen escalating costs, reaching $30 billion by 2022, with multiple launch delays from its initial planned date in 2017. (Estimated data)

Ground Systems: Infrastructure as a Cost Multiplier

Launch complex 39B at Kennedy Space Center was originally built for Space Shuttle. Modifying it for SLS required enormous investment. The Exploration Ground Systems project, which handles all ground support for SLS, has itself become a substantial program.

The Mobile Launcher, a massive structure that holds the rocket vertical and moves it to the pad, cost over a billion dollars to develop. The Launch Control Center renovations, the cryogenic fuel distribution systems, the water suppression systems, the environmental controls—all of this had to be built or heavily modified to support SLS.

This infrastructure isn't reusable if SLS goes away or gets replaced. It's specific to this rocket's unique configuration, its height, its fuel requirements, its operational procedures. That's another hidden cost of the program—not just the rocket itself, but all the stuff that has to be built to launch it.

Other programs might use the same facilities. Space X expressed interest in Kennedy Space Center. But the SLS-specific infrastructure represents sunk cost that only SLS can leverage. It's another lock-in that makes the program harder to cancel despite its inefficiencies.

The Artemis Architecture Mismatch: One Rocket for Everything

SLS is designed to be everything to everyone, which means it's optimized for nothing. It's the only heavy-lift rocket currently in the NASA stable, so it has to handle lunar missions, deep space missions, and theoretically Earth-orbit missions. This drive to be universal compromises efficiency in every specific application.

Commercial space companies specialize. Space X has Falcon 9 for medium lift and Falcon Heavy for heavy lift. They're optimizing each for its specific mission. NASA built one vehicle to handle all missions, which resulted in compromises throughout.

The SLS-Orion combination is overpowered for Earth orbit missions and underpowered for some deep-space scenarios. It's expensive to operate for anything because it's so expensive to manufacture. A company that spent

That's essentially what's happening with Artemis. Each crewed mission represents enormous vehicle production costs, enormous ground system costs, and enormous overhead. The cost per mission is stratospheric compared to alternatives that are becoming available.

The SLS is estimated to launch only once every 2-3 years, significantly less frequently than other programs like Falcon 9, which launches around 20 times a year. Estimated data.

Timeline to Artemis II: When Will Humans Actually Go?

As of early 2025, NASA is targeting no earlier than March for Artemis II. That's four crewed astronauts going around the moon without landing, testing the Orion capsule in a deep-space environment, as reported by CNN.

Following successful Artemis II flight, Artemis III would launch the first humans to lunar surface since 1972. That mission is currently scheduled for 2026 or later, depending on how Artemis II goes. Some observers predict 2027 or 2028 based on the historical pattern of delays.

So we're looking at four humans potentially touching lunar soil in 2026 at the absolute earliest, more likely 2027 or 2028, representing roughly 50+ years after the last lunar landing. The Artemis program would have taken 15+ years from concept to landing, not counting all the prior years of Constellation program development that led to SLS.

Commercially, Space X is pursuing lunar landing missions that might achieve uncrewed surface operations by 2026-2027, with crewed missions by the late 2020s, using vehicles they developed in parallel with and at lower cost than SLS. That's not intended as a criticism of Artemis—government programs operate under different constraints. But it does highlight the relative pace and efficiency of approaches.

What Actually Goes Wrong: Beyond Hydrogen Leaks

Hydrogen leaks are the immediate problem, but they're symptoms of larger design and operational challenges. The complexity of integrating so many components from so many contractors, across so many systems, all designed to work together reliably at high temperatures and pressures, is inherently difficult.

Add in the constraint that you can't practice often, and problems are inevitable. Every launch is somewhat experimental. The team is rusty. Procedures that worked last time might not work this time because they've been sitting around for years gathering dust, and contractors have cycled through personnel and processes.

This is why commercial spaceflight companies that can afford to launch frequently and accept occasional failures are actually building more reliable systems. Reliability through iteration beats reliability through theoretical analysis every time, if you can afford the iteration.

NASA can't afford the iteration with SLS because each iteration costs billions. So they're stuck with theoretical understanding, which has consistently failed to predict how the hardware actually behaves under operational conditions.

What Comes After SLS: The Future of Heavy-Lift Spaceflight

Blue Origin's New Glenn rocket is under development and could enter service by 2027-2028, offering heavy-lift capability and much higher flight rates. Space X's Starship, if it fulfills its promise, will offer even greater lift capability at dramatically lower cost. Other competitors are pursuing various approaches.

SLS will remain NASA's lunar rocket for the foreseeable future, but the competitive landscape is changing. If alternative vehicles achieve the reliability and flight rates that SLS cannot, NASA's commitment to SLS might eventually look outdated.

The fundamental question is whether the agency can afford to maintain multiple heavy-lift vehicles, or whether budget realities will eventually force consolidation around cheaper, faster-flying alternatives.

The Broader Implications: What Delays Mean for Space Exploration

Every delay to Artemis II is a delay to Artemis III. Every delay to Artemis III is a delay to everything downstream. Commercial companies relying on NASA purchases of services are affected. International partners contributing to Artemis Gateway infrastructure have to adjust timelines. The entire deep-space exploration agenda that depends on Artemis becomes more expensive as timelines slip.

Inflation affects program costs. Teams become dispersed. Contractors pivot to other work. When you finally fly, you're not flying with the ideal team because some members have moved on. Some specialized expertise has been lost. The organization has to be rebuilt.

This isn't unique to SLS. Any program with long gaps between flights faces similar challenges. But programs that fly more frequently can cycle through teams and expertise while maintaining momentum. Programs that fly every few years lose that momentum with each delay.

It's another hidden cost of low flight rates. Not just operational inefficiency, but institutional inefficiency that compounds over time.

Acknowledging Reality: What Isaacman's Comments Really Mean

When Isaacman said the flight rate was "the lowest of any NASA-designed vehicle" and should be "a topic of discussion," he wasn't making an idle observation. He was breaking with decades of NASA orthodoxy that defended SLS against external criticism.

For years, NASA leadership argued that the program was on track, performing as expected, and critics were unfair or uninformed. Isaacman, coming from a commercial spaceflight background, apparently decided that diplomatic deflection was less important than honest assessment.

It's a small crack in a large dam, but it matters. If the agency's own leadership acknowledges the flight rate problem, then the conversation can shift from "is there a problem?" to "what do we do about it?" Those are very different discussions.

The "what do we do" question is harder to answer because the options are limited. You can't change the flight rate without redesigning the rocket. You can't redesign the rocket without Congressional approval. You can't get Congressional approval without understanding that changing it serves the program's long-term interests.

That's a lot of steps, and each one is politically difficult. But Isaacman's comments suggest that at least some people in NASA leadership are thinking about it.

The Path Forward: What Needs to Change

Solving the SLS problem doesn't require building a better rocket. It requires changing how NASA approaches heavy-lift spaceflight. That might mean:

1. Accepting commercial alternatives for some missions. Not every NASA deep-space mission needs the absolute highest lift capability. Some could be accomplished with commercial heavy-lift vehicles, freeing SLS for missions that truly require its capabilities.

2. Building for higher flight rates. This might mean increasing production of SLS components, accepting that cost-per-launch will remain high but flight frequency will improve. Higher frequency would improve operational experience and reliability.

3. Accepting that SLS might not be the optimal solution long-term. If Starship or New Glenn mature faster than expected, NASA might transition to different vehicles for certain mission classes. This would require flexibility that Congress hasn't historically granted.

4. Treating SLS as a deep-space architecture component rather than the entire solution. Perhaps SLS launches infrastructure components, while commercial vehicles handle other mission elements. This would increase SLS's value within a broader ecosystem.

None of these are easy choices politically or programmatically. But they're the kinds of choices that acknowledge reality rather than trying to defend the status quo.

Conclusion: Acknowledging Elephants, Solving Problems

The Space Launch System exists because Congress wanted a heavy-lift vehicle and NASA needed to employ contractors across multiple districts. That's not a criticism of anyone involved—it's how government spaceflight programs have historically worked. Accepting political reality doesn't mean accepting poor performance, though.

NASA Administrator Isaacman's acknowledgment that flight rate is a problem worth discussing represents a shift in how the agency is willing to talk about SLS publicly. It's a small shift, but in a culture that historically defended every aspect of the program, it matters.

The hydrogen leaks are just the most visible symptom of a deeper architectural problem: a rocket that costs so much to build and maintain that it can't fly frequently enough to accumulate the operational experience that would make it reliable and efficient.

Fixing the leaks is possible. Better seals, improved installation procedures, more careful testing. NASA will probably fix them, and the Artemis II launch will eventually happen. But fixing the flight rate problem requires accepting that the current architecture has fundamental limitations, and that no amount of engineering can overcome those limitations.

That's a harder conversation than debating hydrogen seal specifications. But it's the conversation that NASA leadership is now willing to have, which suggests that at least some people in the agency understand that problems acknowledged are problems that can eventually be addressed.

Until someone in authority says the elephant is in the room, the conversation stays about the furniture arrangement. Isaacman just said the elephant is in the room. What happens next will determine whether that acknowledgment becomes the beginning of meaningful change or just another press statement filed away in the archives of space program history.

FAQ

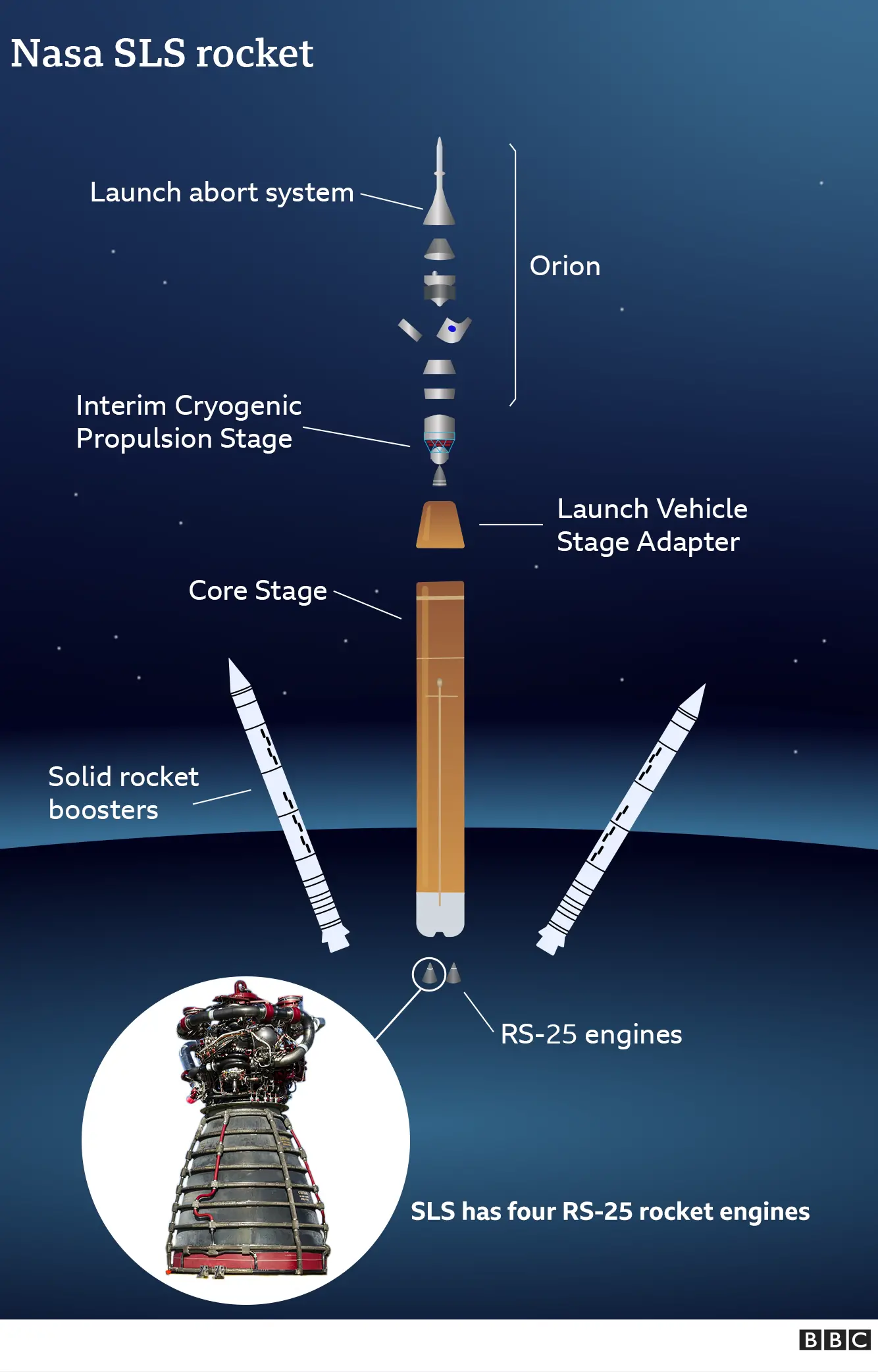

What is the Space Launch System rocket?

The Space Launch System (SLS) is NASA's super-heavy-lift launch vehicle, designed to send Orion spacecraft to the Moon and beyond. It's the most powerful operational rocket ever built, capable of lifting 70,000 kilograms to lunar orbit. The rocket uses four RS-25 liquid hydrogen engines on its core stage, supplemented by two Solid Rocket Boosters on its first stage, producing approximately 8.8 million pounds of thrust at liftoff. After 15 years of development and over $30 billion in investment, SLS achieved its first crewed test flight with Artemis I in November 2022.

Why does SLS have hydrogen leak problems?

Liquid hydrogen is extremely cold at minus 253 degrees Celsius, making it an exceptionally unforgiving propellant. The hydrogen molecule is tiny, allowing it to escape through microscopic gaps that would contain other liquids. The primary leak issues occur at ground-to-flight interfaces where ground support equipment connects to the rocket's fuel systems. These interfaces involve multiple seals, thermal gradients, and pressure cycling that create complex conditions where even minor misalignments or material degradation can cause leaks. NASA's ground systems weren't specifically designed for SLS's hydrogen handling requirements, leading to compatibility problems between legacy Kennedy Space Center infrastructure and the new vehicle. The cold temperature also causes materials to behave differently than at room temperature, complicating seal design and installation procedures.

What does flight rate mean, and why is SLS's so low?

Flight rate refers to how frequently a vehicle launches, typically expressed as missions per year or average days between launches. SLS has an extremely low flight rate, with estimates suggesting one mission roughly every 2-5 years. This is extraordinarily slow for a modern rocket—for comparison, Space X's Falcon 9 launches multiple times monthly, and even the legacy Space Shuttle program achieved 4-5 launches annually. SLS's low flight rate results from several factors: extreme manufacturing costs ($2+ billion per vehicle) limiting production, Congressional resistance to increasing costs, and limited demand for missions requiring SLS's specific capabilities. The low flight rate creates cascading problems including reduced operational experience, higher overhead costs per mission, technical team attrition, and worse reliability precisely because familiarity improves performance.

How much has SLS cost taxpayers?

NASA has invested over

When will Artemis II launch with astronauts?

As of early 2025, NASA targeted no earlier than March for the Artemis II mission, though additional delays remain possible. Artemis II will carry four astronauts around the Moon without landing, testing Orion capsule performance in deep space. The mission has been delayed multiple times, with the most recent delays related to SLS ground system issues and hydrogen leak challenges. Following a successful Artemis II flight, Artemis III would attempt the first crewed lunar landing since 1972, currently targeted for 2026 or later. Given the historical pattern of delays, many observers predict lunar landing missions won't occur until 2027 or 2028. The delays represent roughly 50+ years between the last crewed lunar landing (1972) and the next one.

What are NASA's alternatives to SLS?

Several commercial and governmental alternatives exist or are under development. Space X's Falcon Heavy currently operates and has demonstrated heavy-lift capability, though specialized Artemis missions require particular architectures. Blue Origin is developing New Glenn, expected to provide heavy-lift capability by 2027-2028 with anticipated higher flight rates and lower per-mission costs. Space X's Starship, still in development, promises even greater lift capacity at dramatically lower operational costs if it achieves design goals. United Launch Alliance is developing an upgraded version of the Delta IV Heavy. These alternatives offer different trade-offs in capability, cost, availability, and schedule, but none have NASA's political mandate for Artemis missions the way SLS does. Commercial vehicles increasingly offer more frequent launches and lower per-mission costs, though they're less specialized for the Artemis architecture than SLS.

Why doesn't NASA just fix the hydrogen leak problem?

NASA is actively working to fix the leak issues, employing techniques from Artemis I campaigns including flow rate adjustments, pause-and-warm procedures, and improved seal specifications. However, perfect fixes require understanding that extends beyond component-level testing. Commercial rocket programs solve this by building test articles and practicing procedures repeatedly with full hardware and ground systems before flight missions. SLS's extreme cost structure prevents this approach: each vehicle costs $2+ billion, making test articles economically unfeasible. Instead, NASA conducts component testing and procedural analysis but cannot practice the full operational sequence with high frequency. This limitation means every actual countdown is somewhat experimental, making leak problems more likely. The deeper fix would require either increased production enabling test article construction (costly) or accepting that full operational understanding must come through careful analysis supplemented by learning through early missions.

What is the Artemis program, and how does SLS fit into it?

Artemis is NASA's program to establish sustainable human lunar presence, beginning with the circumlunar Artemis I (crewed) and Artemis II (crewed) missions using SLS and Orion, followed by surface landing missions (Artemis III and beyond). SLS serves as the launcher for Artemis missions, providing the heavy-lift capability needed to send Orion spacecraft and lunar systems to lunar orbit. The program also includes the Gateway, a planned lunar orbit station providing logistics and habitation for surface missions. SLS is central to Artemis because it's the only vehicle currently in NASA's inventory with sufficient lift capacity and the political mandate for lunar missions. However, the program's architecture is now being reconsidered as commercial alternatives mature, potentially allowing some components to launch on commercial vehicles while SLS remains dedicated to crewed spacecraft and critical infrastructure.

Is SLS better or worse than commercial alternatives?

SLS excels in raw lift capacity and specialization for deep-space missions, offering capabilities that existing commercial vehicles cannot match. However, it underperforms on cost efficiency, flight rate, and operational reliability. Cost-per-kilogram to orbit vastly favors emerging commercial vehicles like Falcon Heavy and future systems like New Glenn and Starship. SLS's extreme cost structure means it can only be justified for missions requiring maximum capability and payload flexibility. For many potential missions, commercial vehicles offer better value through lower cost, more frequent availability, and more mature operational procedures. The comparison isn't a matter of technical superiority in one direction—SLS is technically sophisticated and capable, but it solves problems differently than commercial approaches, often accepting higher cost in exchange for maximum capability and reduced schedule risk for critical missions.

Conclusion: The Reckoning Arrives

The Space Launch System represents both the best and worst of how NASA approaches spaceflight. At its best, it's a remarkable engineering achievement: a vehicle capable of tremendous performance, designed to support deep-space exploration, built by the finest engineers and contractors America can assemble. At its worst, it's a cautionary tale about how political momentum, cost escalation, and architectural decisions made years ago can lock a program into a trajectory that becomes increasingly difficult to change.

NASA Administrator Isaacman's public acknowledgment that flight rate deserves discussion is significant not because he revealed anything new—critics have been pointing this out for a decade—but because it signals that the agency's internal conversation is shifting. The conversation can now move from "SLS performs as designed" to "SLS performs as designed, but the design has fundamental limitations."

That's progress, albeit slow. Real change in government spaceflight typically moves at glacial pace, constrained by Congressional timelines, budget cycles, and political calculation. But at least now the discussion is honest. The elephant in the room has been acknowledged. What happens next will depend on whether that acknowledgment becomes the beginning of meaningful architectural evolution or just another talking point in the endless debate about how America should organize its spaceflight efforts.

For astronauts waiting to reach the Moon, the question isn't entirely academic. Delays aren't just budget items on spreadsheets. They're years of waiting. For a nation that hasn't put humans on the Moon in over five decades, every delay feels consequential. The SLS will eventually fly again. Astronauts will eventually travel beyond Earth orbit. The Moon will wait. But the window for establishing American leadership in cislunar space isn't infinite. How quickly NASA can address its launch systems' limitations might ultimately matter more than how powerful those systems are.

Key Takeaways

- SLS has consumed $30+ billion over 15 years with just one successful launch, while commercial alternatives achieved similar capabilities with fraction of cost

- Hydrogen leak problems persist three years after Artemis I despite supposed aggressive component testing, revealing the cost constraints prevent realistic full-system testing

- Flight rate of 1 mission every 3-5 years is catastrophically low for any modern rocket, making every launch experimental and operational costs astronomical

- NASA Administrator Isaacman publicly acknowledged the flight rate problem for first time, breaking with agency tradition of defending SLS against criticism

- Artemis lunar landing missions now projected for 2027-2028 or later, representing 55+ years since last crewed lunar surface activity

Related Articles

- Artemis II Wet Dress Rehearsal: NASA's Final Test Before Moon Launch [2025]

- NASA Artemis 2 Launch Delayed to March: What the Hydrogen Leak Means [2025]

- Blue Origin Pauses Space Tourism for NASA Lunar Lander Development [2025]

- Blue Origin Pauses Space Tourism to Focus on Moon Missions [2025]

- SpaceX Starship V3 Test Flight: What the Mid-March Launch Means [2026]

- Blue Origin's New Glenn Third Launch: What's Really Happening [2026]

![NASA's SLS Rocket Problem: Why the Costliest Booster Flies So Slowly [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/nasa-s-sls-rocket-problem-why-the-costliest-booster-flies-so/image-1-1770217874843.jpg)