Introduction: The Visionary Nobody Paid Attention To

While Silicon Valley in the early 1980s was obsessed with disk drives, GUIs, and debating whether anyone would actually want a mouse, a 25-year-old Japanese software designer named Sunao Takatori was describing a future that feels unsettlingly familiar in 2026. In May 1984, Alexander Besher, then a contributing editor at Info World, flew to Japan to meet Takatori, who had just grown his software company Ample Software from ¥1 million in revenue to ¥100 million in a single year. Besher's article described Takatori as "weirder than Bill Gates, Gary Kildall, Mitch Kapor, and Steve Wozniak put together." That weirdness, when you look back four decades later, wasn't strangeness at all. It was prescience.

Takatori predicted AI companions that would greet users "with sincere feelings." He envisioned portable computers without keyboards or monitors. He imagined smart homes with computing built into walls. He talked about systems that could understand human emotion. And he developed a deliberate methodology for training his intuition to see technological futures that others couldn't yet conceptualize.

The remarkable thing? He wasn't wrong. Not once. Today, as we navigate a world of voice assistants, smartphones, AI companions, and homes connected by invisible networks, Takatori's 1984 predictions read like someone describing our present day to us from the past. This article explores how one Japanese software designer developed a framework for technological foresight so effective that it remained accurate across four decades, and what his approach teaches us about innovation, intuition, and the future of human-computer interaction.

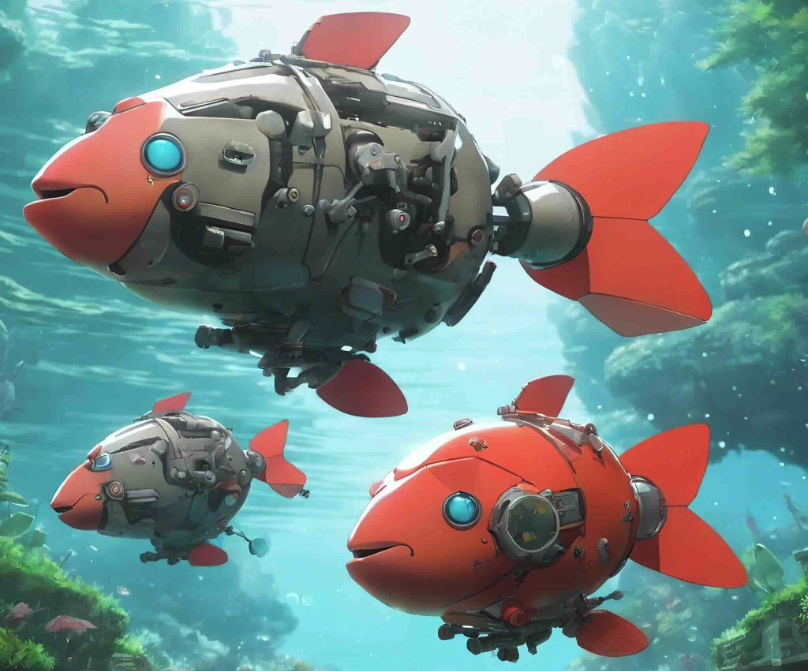

Takatori's story matters now more than ever. As AI becomes increasingly embedded in everyday life, his insistence on designing for human emotion, not just functionality, feels prophetic. His commitment to training intuition through unconventional exercises like walking "on all fours" from Shibuya to Shinjuku to see the world through a dog's eyes sounds eccentric until you realize that multimodal AI—systems trained to understand vision, language, emotion, and context simultaneously—is exactly what we're building today.

TL; DR

- Takatori predicted AI companions in 1984 when most computers couldn't manage basic file systems

- He envisioned smartphones without keyboards nearly three decades before iPhone eliminated physical keyboards

- Smart homes were his obvious future while others debated whether computers belonged on desks

- His methodology for foresight was deliberate and trainable, not mystical—involving perspective shifts and emotional AI design

- Bottom Line: A largely forgotten Japanese engineer saw our technological present more clearly than the celebrated visionaries of Silicon Valley

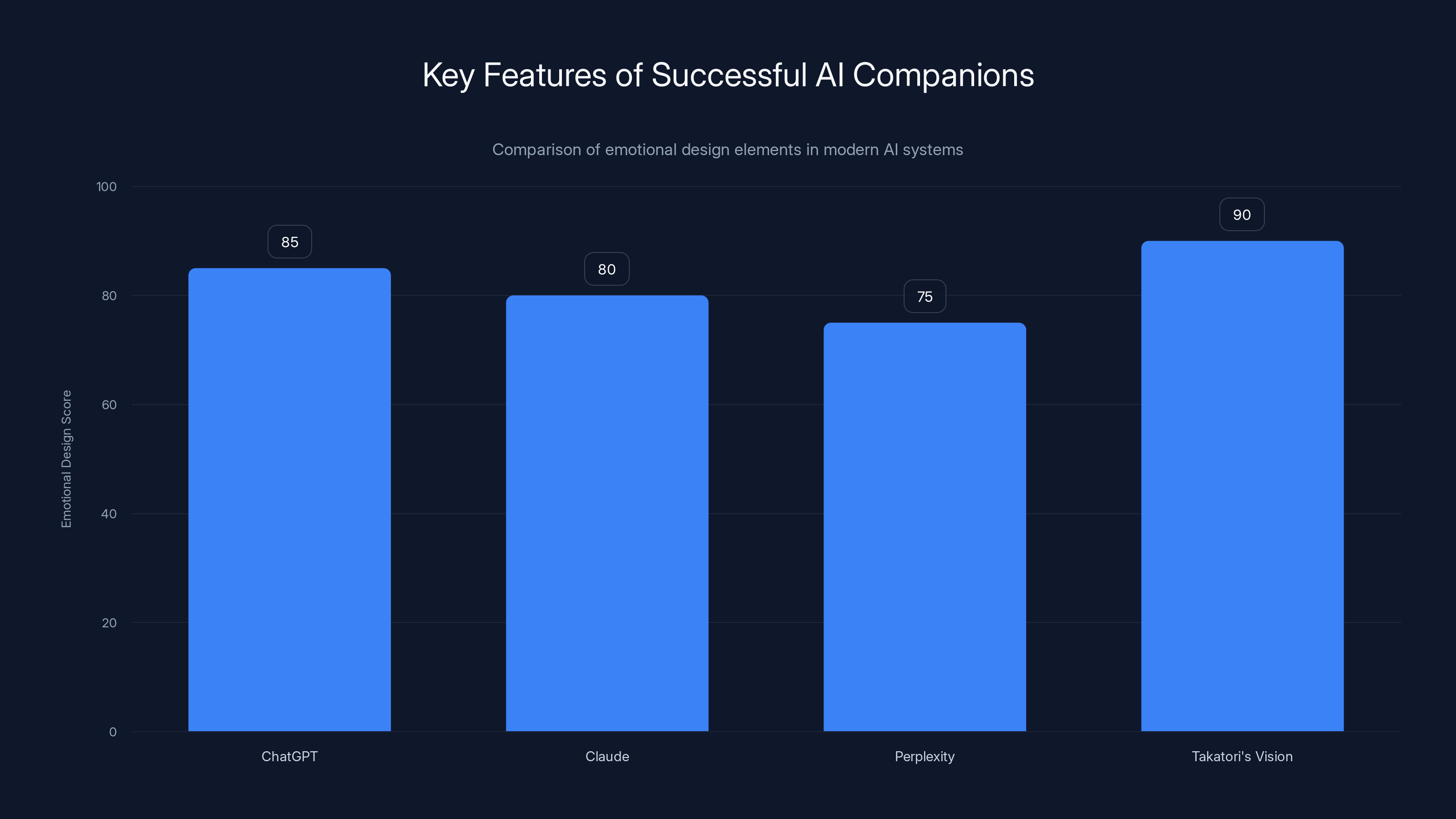

Estimated data suggests that AI systems with strong emotional design, like ChatGPT and Claude, excel in user engagement by creating a sense of understanding and trust.

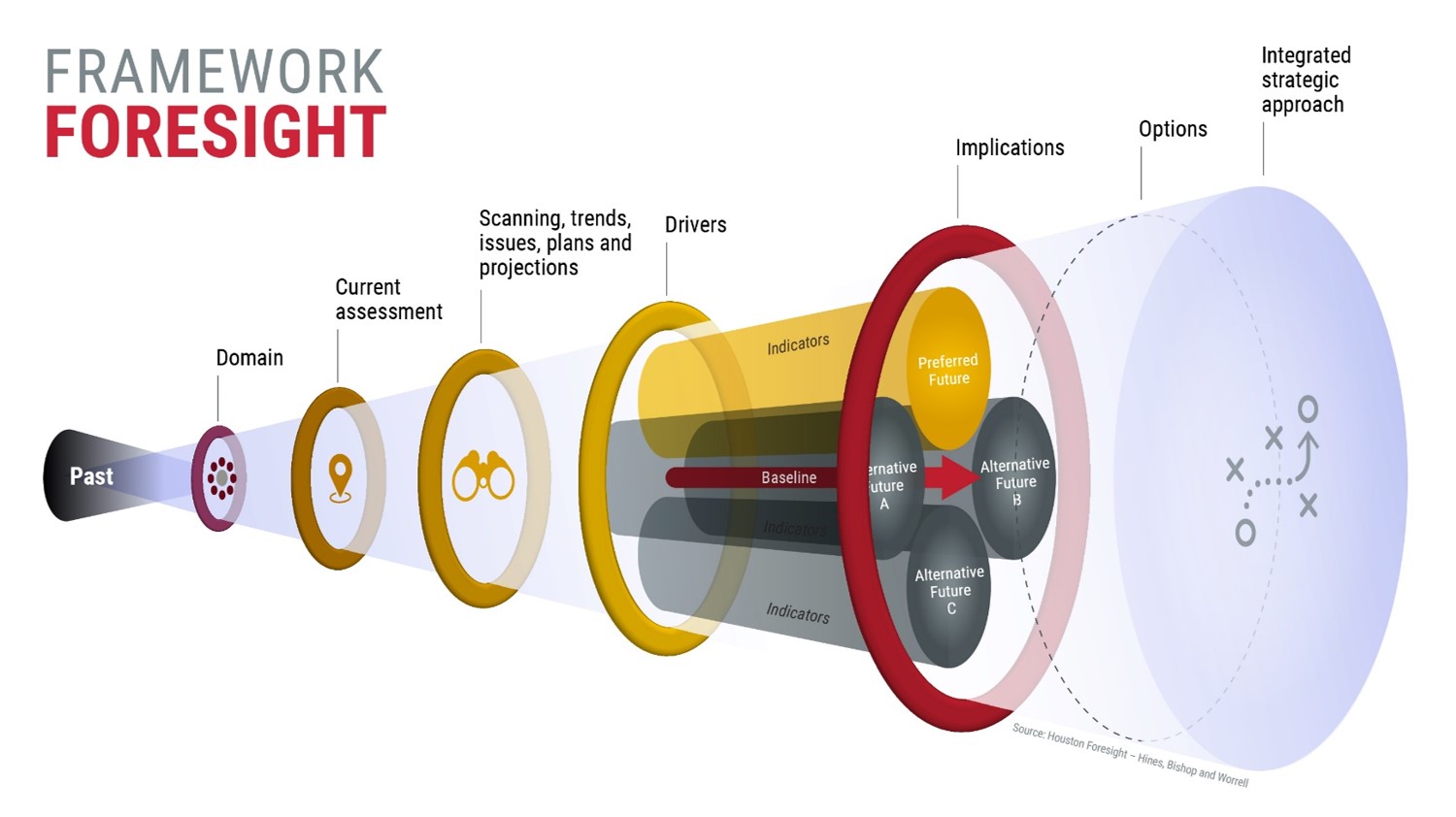

The Sixth Sense: A Framework for Technological Foresight

Takatori didn't believe in conventional wisdom. He believed in sixth sense. When Besher asked Takatori how he could predict technological futures so accurately, Takatori explained that "the five senses convey only a partial reality." This wasn't mysticism dressed up in technological language. This was a deliberate epistemic position: that empirical observation alone—watching what exists now—creates a fundamental blindness to what's possible.

Instead, Takatori trained himself to rely on intuition that he deliberately cultivated. "I can see the changing trends of the industry," he said. "I sometimes can visualize the next generation of computers in vivid colors as if the images are a fast-motion picture on a color TV screen."

But how do you train intuition about computers when computers are new? Takatori's answer was counterintuitive. You step outside human consciousness entirely.

Training Intuition Through Non-Human Perspective

Takatori's most famous (and strangest-sounding) practice involved literally training himself to perceive the world through non-human sensory frames. He didn't do this as metaphor or exercise. He did it as serious cognitive training.

"A car appears as if it were a gigantic and distorted building," he explained in 1984. "I now see the world through a dog's eyes. Everything I see, even pebbles and discarded chewing gum stuck on the road, has a unique and interesting appearance. It's a lot of fun to take a walk from Shibuya to Shinjuku on all fours at a dog's eye level."

This sounds absurd. It is absurd. It's also exactly what modern neuroscience tells us builds novel cognitive frameworks. When you force your brain to process information through an alien sensory hierarchy—where pebbles matter as much as buildings, where the world's geometry shifts radically—you're literally rewiring how your brain prioritizes information. You're building a new attention model.

Then there was the dolphin. "I am swimming in the ocean," Takatori said. "Only my eyes are sticking out of the water. I'm now familiar with the dolphin's vision. I'm extremely pleased with this discovery. Then I wonder how I can express the world as seen from different visual points."

What Takatori was describing sounds like preparation for multimodal AI—training systems to interpret the world through different sensory frames simultaneously, each with different priorities and perception thresholds. Modern AI models like GPT-4o and Claude 3.5 do exactly this: they're trained on text, images, video, and audio, each modality reweighting what matters.

Takatori was 40 years ahead on this.

Why Perspective Shift Matters for Design

Takatori understood something that most engineers of his era didn't: that technology designed from a single sensory frame would feel incomplete to humans who live in multiple sensory frames simultaneously. A computer that only processes text can't understand context. A system that only sees images can't understand narrative. A device that only hears voice can't detect emotional subtext.

What Takatori called the "sixth sense" was really a deliberately trained capacity to think in multiple frames at once. He forced himself to see like a dog, to perceive like a dolphin, to imagine how "invisible entities" would experience his software. This made him uniquely equipped to design systems that could accommodate human complexity.

You see this in his insistence on emotional AI. In 1984, when computers were logical machines, Takatori was arguing that computers needed to "greet the user with sincere feelings." This wasn't sentiment. It was a design principle: that humans experience technology emotionally, and software that ignores emotion isn't actually meeting human needs.

When modern AI systems fail despite technical sophistication, it's often because they optimize for the wrong frame. A customer service bot that's technically correct but emotionally tone-deaf. A recommendation algorithm that's statistically accurate but contextually blind. Takatori would have called these failures what they were: insufficient perspective shifts during design.

The Practice of Deliberate Alienation

What makes Takatori's approach distinctive is that it's trainable. He didn't claim to be specially gifted. He claimed that perspective-shifting could be practiced like any skill.

"If I discover something new in the process, then somehow I would like to convey it in order to share the experience with others," Takatori said. "I believe that software is the best means to express such a discovery."

This is a design philosophy. Takatori believed that systematic perspective-taking—deliberately experiencing the world through frames radically different from your own—would generate insights that single-perspective analysis couldn't touch. And more importantly, that these insights could be embedded in software.

Modern product teams essentially rediscovered this practice. User research, persona development, accessibility testing—these are all systematized perspective-shifts. Takatori was doing this alone, through physical practice, in 1984.

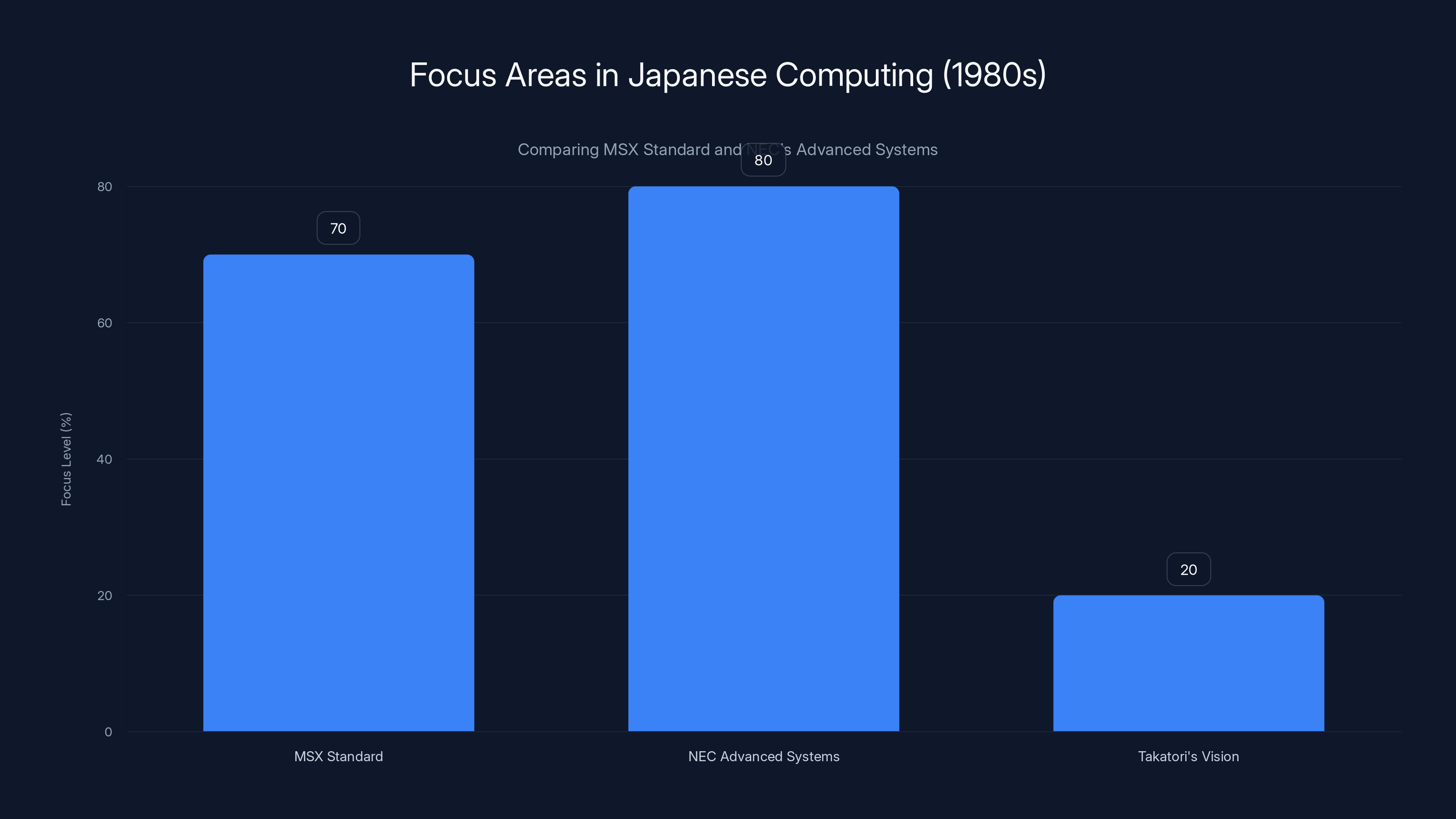

In the 1980s, Japan's computing industry focused heavily on consumer computing and advanced systems, with less emphasis on emotional AI, as envisioned by Takatori. (Estimated data)

Predicting Personified Computers: The AI Companion Vision

When Takatori talked about "personified computers," he meant something very specific: AI systems with emotional depth, not just computational power.

In 1984, this was not a mainstream prediction. The dominant narrative was that computers would become faster, more powerful, increasingly logical. Takatori inverted this. He predicted that the real transformation would be emotional. Computers wouldn't become more rational. They'd become more human.

"Unless a computer has personified features like greeting the user with sincere feelings, it shouldn't be called an educational device," Takatori said.

Consider what this means. In 1984, we were debating whether computers should have windows or command lines. The idea that a computer's primary function was to make the user feel welcomed, understood, genuinely attended to—this was foreign. Computers were tools. They did things. They didn't have relationships with users.

The Emotional Interface Revolution

Takatori predicted that the future of computing wasn't about faster processors or more storage. It was about the quality of the relationship between human and machine. This is why his prediction of "personified" AI matters.

Today, the most successful AI products aren't the ones with the best algorithms. They're the ones that create a sense of understanding. ChatGPT didn't win because it's technically superior to alternatives. It won partly because it feels like someone is listening to you. Claude developed a reputation for thoughtfulness. Perplexity built trust through transparency (showing sources). These are emotional design choices.

Takatori understood this in 1984. He saw that the future wouldn't be populated by faster calculators. It would be populated by systems that understood human needs emotionally. A computer that greeted you with sincerity. That remembered what mattered to you. That adapted not just to your behavior, but to your feelings.

This is exactly what modern AI companions aim to do. ChatGPT's personality was deliberately designed to be helpful, harmless, and honest—emotional parameters, not just functional ones. Anthropic's Claude was trained using Constitutional AI, which includes emotional and ethical dimensions. These aren't afterthoughts. They're core to the product.

Takatori saw this before anyone else articulated it.

The Portable Computer Without Keyboards

Takatori made another specific prediction that shows remarkable foresight: "a portable, yet not necessarily mobile personal computer without keyboards and monitors."

Stop and think about that prediction in 1984.

In 1984, portable meant the Osborne 1: a 25-pound machine with a 5-inch screen and disk drives. It was technically mobile, but nobody would call it portable. The idea of a computer without a keyboard or monitor wasn't just uncommon. It was barely conceptualized.

Yet this is exactly what smartphones became. Devices that are portable (fit in your pocket), not necessarily mobile (used while stationary), without traditional keyboards or separate monitors. Just a screen that responds to touch and voice.

Takatori predicted this 23 years before the iPhone. More impressively, he understood the category difference. "Portable, yet not necessarily mobile"—he recognized that the revolutionary device wouldn't be something you carry while moving. It would be something you carry everywhere, then use wherever you stop.

This is the smartphone. Not a computer that moves with you (mobile), but a computer that's with you (portable), that you interact with wherever you are. The distinction is subtle but profound, and Takatori made it explicit in 1984.

The Integration of Telephone, Television, and Database

Takatori made one more crucial prediction that's worth examining closely: "Eventually polarization will take place after a period during which the functions of the telephone, TV, and analogical database are assimilated."

What he's describing is the convergence of three distinct technologies into unified systems. Telephone (communication), TV (media), and database (information) converging into single devices. This is exactly what smartphones accomplished. They're phones, they're screens for video and media, they're databases of information you carry with you.

But Takatori saw something else: that after this convergence, the market would split. "One polarity represents innovative stationary computers such as those which will be built into the wall." This is the smart home—computational power embedded in infrastructure. "The other polarity will be the personified computers (AI), which will start to develop at a rapidly accelerating pace."

Takatori predicted both the infrastructure layer (computing in walls) and the agent layer (personified AI). He understood that convergence doesn't mean everything becomes one device. It means devices differentiate into specialized categories: embedded systems and conversational agents.

Look at the actual market today. We have smart home ecosystems (Alexa, Google Home, Apple Home). We have portable AI systems (ChatGPT, Claude, Perplexity). We have embedded computing (chips in everything). Takatori's polarization prediction was exactly right.

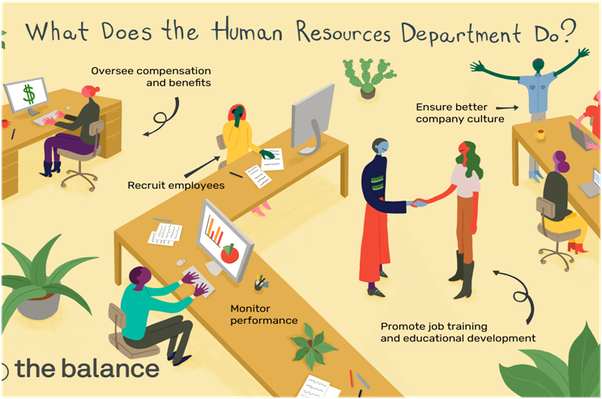

The Japanese Computing Ecosystem: A Parallel Path

While Takatori was developing his theories about AI and emotional computing, Japan's broader technology industry was pursuing a very different strategy. This distinction matters because it shows how one visionary could be almost completely ignored by both the Western tech industry and his own national ecosystem.

The MSX Standard and Consumer Computing

In the early 1980s, Japan was invested in a different computing vision: the MSX standard. Developed by a consortium including Philips, Yamaha, and others, MSX was meant to be a universal home computer standard, much like how VCRs had become universal video players.

MSX machines could be integrated into televisions. They could run cartridges. They were designed for consumers, not professionals. In some ways, MSX anticipated the console-based computing that would eventually dominate consumer gaming (Nintendo, PlayStation, Xbox). But it was never positioned as a platform for AI or emotional computing.

Takatori's vision was almost orthogonal to this. While Japan's industry was building consumer computing infrastructure, Takatori was predicting that the real future was in making computers that understood people emotionally.

NEC's Advanced Systems

Takatori actually worked with NEC, one of Japan's computing giants. NEC was developing advanced systems like the PC-9801, which was technically sophisticated—but still designed around conventional interfaces: keyboards, monitors, file systems.

NEC's approach represented the engineering consensus: faster, more capable machines. Takatori's approach represented something different: machines designed around human emotion and non-standard interfaces.

It's telling that even while working with Japan's most advanced technology companies, Takatori's vision of emotional, personified AI didn't dominate the market. The industry bet on infrastructure and capability. Takatori bet on human-centered design and emotional intelligence.

Plum-Colored Machines and Experimental Hardware

Besher's reporting captured a Tokyo overflowing with experimental hardware. MSX TV sets. Plum-colored machines with cartridges. Advanced systems. Japan was exploring multiple paths simultaneously.

But the path that actually dominated—both in Japan and globally—was the path of raw computational power and standardization. The PC market (Intel-based, Windows-driven in the West) and eventually the mobile market (iOS and Android) won, not because they were emotionally intelligent, but because they became standardized, capable platforms.

Takatori's insights about emotional AI and personified computers were largely correct, but they took decades to manifest. They didn't dominate in 1984 or 1994 or even 2004. Only now, in the era of large language models and AI assistants, are they becoming practical.

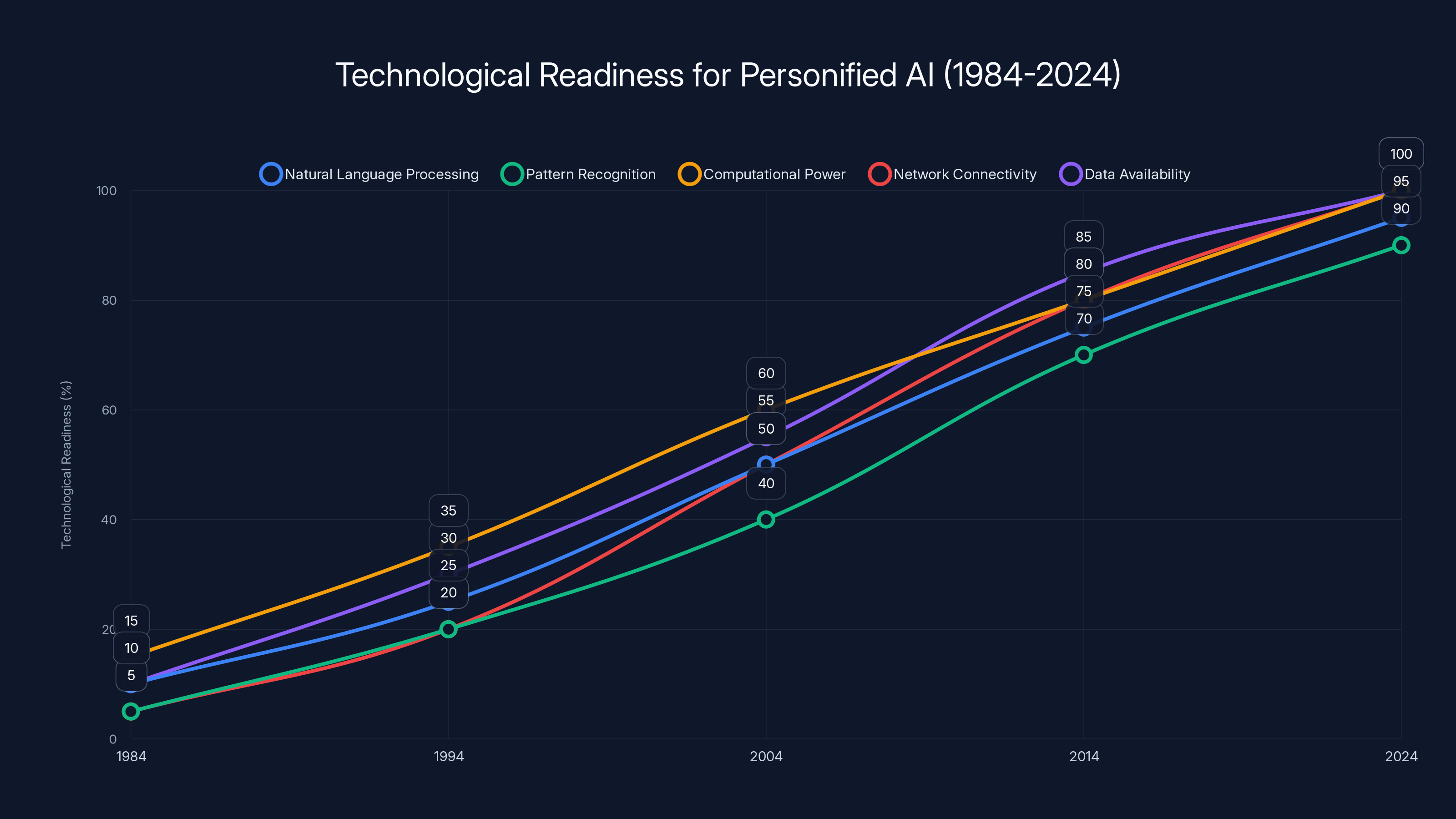

Estimated data shows the gradual readiness of technologies needed for personified AI from 1984 to 2024. Takatori's vision was ahead of its time, with necessary technologies only becoming viable decades later.

Why Takatori Was Ignored: The Paradigm Timing Problem

Here's the crucial question: if Takatori's predictions were so accurate, why did he become essentially forgotten in the history of computing?

The answer reveals something important about innovation cycles: being right too early is sometimes indistinguishable from being wrong.

The Infrastructure Prerequisite Problem

Takatori was predicting personified AI in 1984. But personified AI requires:

- Natural language processing at scale

- Pattern recognition sophisticated enough to detect emotion

- Computational power cheap enough to run in consumer devices

- Network connectivity to train and update systems

- Data about human preferences and language at massive scale

None of these prerequisites existed in 1984. Natural language processing was in its infancy. Pattern recognition was decades away from the deep learning revolution. Consumer computing was limited to 64KB or 512KB of RAM. Internet was academic. Digitized text databases were primitive.

Takatori could see the destination clearly. But the path to get there required technologies that wouldn't exist for 20, 30, even 40 years. In a very real sense, he was seeing a world he couldn't build.

The Credibility Paradox

Takatori's vision was so far ahead of its time that it became difficult for others to take seriously. When someone predicts something 40 years in advance, and most of your contemporaries are debating whether the prediction is even theoretically possible, it's hard to maintain credibility as a practical engineer.

Bill Gates could be taken seriously predicting faster personal computers. Takatori predicting that computers would understand emotions and greet users with sincerity sounded like science fiction. It was science fiction. It just happens to be the science fiction that became reality.

The Wrong Geographic Context

Takatori was also working in Japan, not Silicon Valley. The American tech industry has structural advantages in setting narratives: it's where venture capital concentrated, where magazines like Info World were read by engineers, where the media landscape amplified certain stories and ignored others.

Takatori's work was translated and reported by Info World, but then largely forgotten in the Western narrative. Meanwhile, Japanese computing companies pursued their own path. Neither ecosystem fully adopted or developed Takatori's vision because the infrastructure didn't exist to make it practical.

It took the 2010s—when GPUs enabled deep learning, when data became abundant, when networks were ubiquitous—for the conditions to exist where Takatori's vision could actually be built. By then, he was a historical footnote.

Multimodal AI: Takatori's Sixth Sense Made Practical

Now, in the 2020s, Takatori's vision of the sixth sense is being realized through multimodal AI. These are systems trained to interpret the world through multiple sensory modalities simultaneously, each with different priorities and perceptual thresholds.

How Multimodal Systems Work

When Takatori trained himself to see like a dog, then like a dolphin, then like an "invisible entity," he was developing multiple concurrent perceptual frames. Modern multimodal AI does something mathematically similar.

A system like GPT-4V (GPT-4 with vision) doesn't just process images. It processes images and text simultaneously, with an attention mechanism that can weight between modalities. It can look at a diagram and read text describing it, integrating both sources of information into a more complete understanding.

Eleven Labs' voice cloning system similarly integrates audio characteristics, linguistic patterns, emotional tone. It's not just processing voice. It's understanding voice through multiple concurrent frames.

Meta's recent work on multimodal foundation models does exactly what Takatori predicted: trains a single system to understand images, video, audio, and text as co-equal inputs, each with their own perceptual importance.

Emotional Intelligence in AI

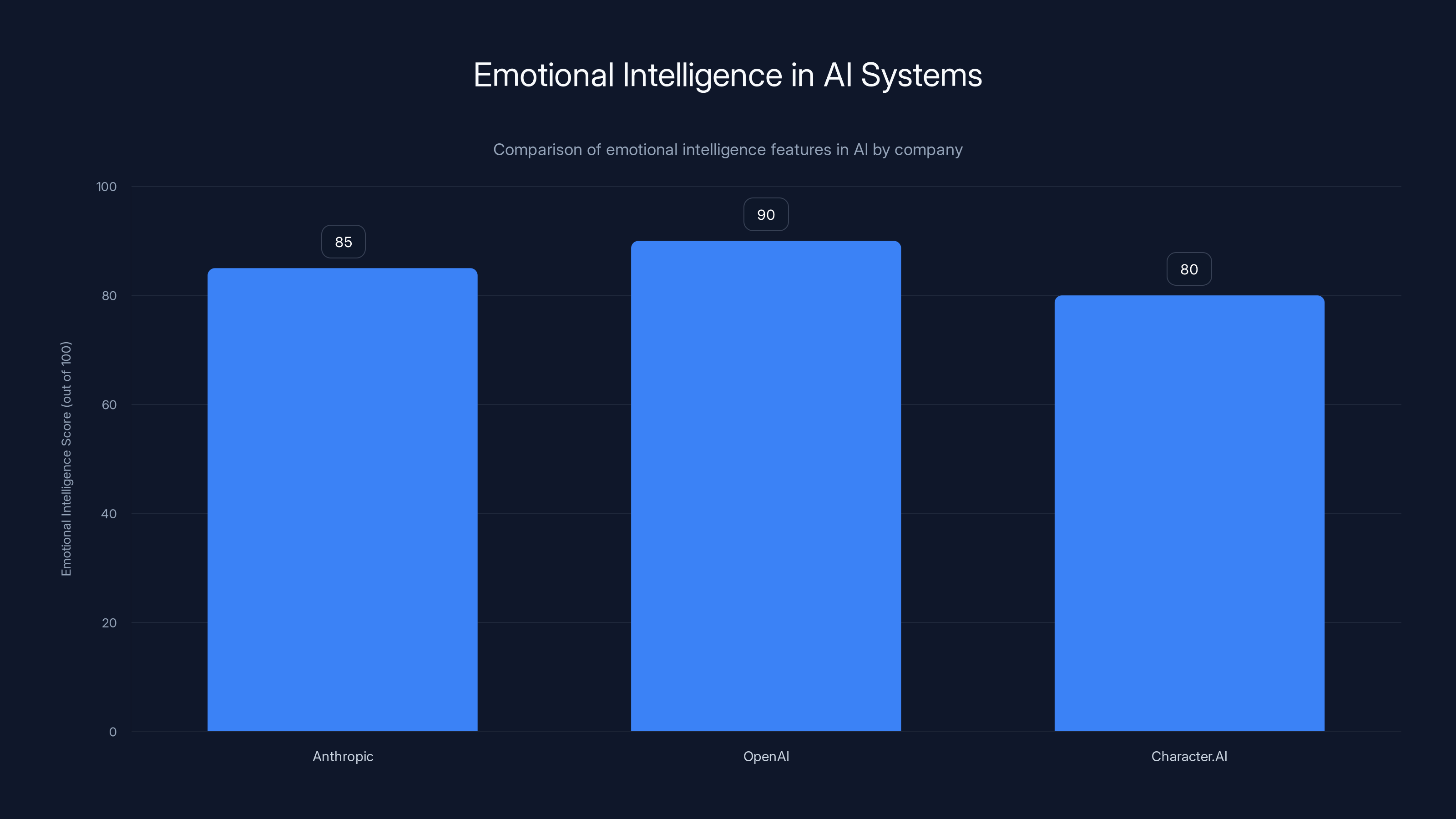

Takatori predicted that computers would need to "greet the user with sincere feelings." Modern AI companies are implementing this through different approaches:

- Anthropic's Constitutional AI: Claude is trained to be helpful, harmless, honest, and harmless in ways that reflect emotional understanding

- OpenAI's personality design: ChatGPT's tone and style were deliberately chosen to feel approachable and understanding

- Character.AI and similar systems: Explicitly training conversational AI to develop personality and emotional consistency

These aren't just making AI seem more human. They're implementing systems that actually model emotional understanding. A system that recognizes you're frustrated, adjusts its tone, remembers your preferences, and treats your concerns seriously—this is what Takatori meant by personified computing.

OpenAI leads in emotional intelligence with a score of 90, followed by Anthropic and Character.AI. Estimated data based on qualitative descriptions.

The Smartphone as Personified Device

Takatori's vision of "a portable, yet not necessarily mobile personal computer without keyboards and monitors" became the smartphone. But the smartphone isn't just a prediction-come-true. It's the infrastructure enabling his broader vision of personified computing.

From Tool to Companion

The smartphone started as a tool (a phone you could access email on). It became a companion (a device that knows your calendar, your preferences, your patterns). Modern smartphones with AI assistants are moving toward Takatori's vision of systems that greet you with understanding and adapt to your emotional state.

Siri started as functional ("set a timer"). It's becoming more contextual. Your phone learns when you usually want music, notices when you're driving, understands that "call Mom" might be urgent or routine depending on time and context.

This is personification through software. The device doesn't just process commands. It understands intent and emotion.

The Home Integration

Takatori predicted both portable computers (smartphones) and "stationary computers built into walls" (smart homes). The smartphone became the control interface for the home. Your iPhone or Android device controls your lights, your thermostat, your security—the embedded computing Takatori foresaw.

But there's a deeper integration happening. Smart home systems are becoming increasingly personified. Alexa and Google Home don't just control devices. They're developing personalities, learning your preferences, understanding your household's patterns and routines.

Takatori envisioned this complete integration: portable systems that are personified, embedded systems that are personified, all coordinated in your environment.

The Lesson: Training Your Sixth Sense

Beyond the specific predictions, Takatori's methodology offers something valuable for anyone trying to anticipate technological futures: the sixth sense can be trained.

Deliberate Perspective-Taking

Takatori's approach was systematic. He literally practiced seeing the world through non-human perspectives. This wasn't meditation or mysticism. It was cognitive practice.

Modern teams can apply this principle without the Shibuya-crawling-on-all-fours drama:

- Adversarial thinking: How would someone hostile to your product use it? What vulnerabilities would they find?

- Accessibility testing: How would someone with different abilities interact with this? What does their perspective reveal about design assumptions?

- Ethnographic research: Observe how actual people, in their own contexts, interact with technology. Don't just interview them; watch them.

- Future scenarios: Write out detailed narratives of how your product might be used in five years. Make them vivid. What breaks? What exceeds expectations?

- Cross-disciplinary input: Bring in perspectives from fields that seem unrelated. How would a novelist think about this? A musician? An architect?

Each of these is a practice in perspective-shifting. They're training your sense for what's coming.

Emotion as Design Parameter

Takatori insisted that emotional understanding was foundational, not optional. Most of the software engineering of his era treated emotion as aesthetic (nice interface colors) rather than functional.

Modern AI is rediscovering this. Emotion isn't decoration. It's information. A user who's frustrated is different from a user who's confused, which is different from a user who's bored. A system that can distinguish these emotional states and respond appropriately is more useful than a system that just processes commands.

Multimodal Thinking

Takatori trained himself to think in multiple sensory frames simultaneously. Modern product design does this through different mechanisms:

- Accessibility requirements: Force you to think about how a product works for someone who can't see, hear, or move in typical ways. This rewires how you think about the product.

- Localization: Adapting for different languages and cultures forces you to recognize how meaning changes across contexts.

- Device diversity: Designing for phone, tablet, desktop, watch, etc., forces you to think about what the core function actually is, separate from any specific interface.

- Multimodal interfaces: Voice, touch, gesture, gaze—each modality reveals different aspects of the problem.

When you force yourself to think through all these frames simultaneously, you develop intuition about what actually matters versus what's interface-specific.

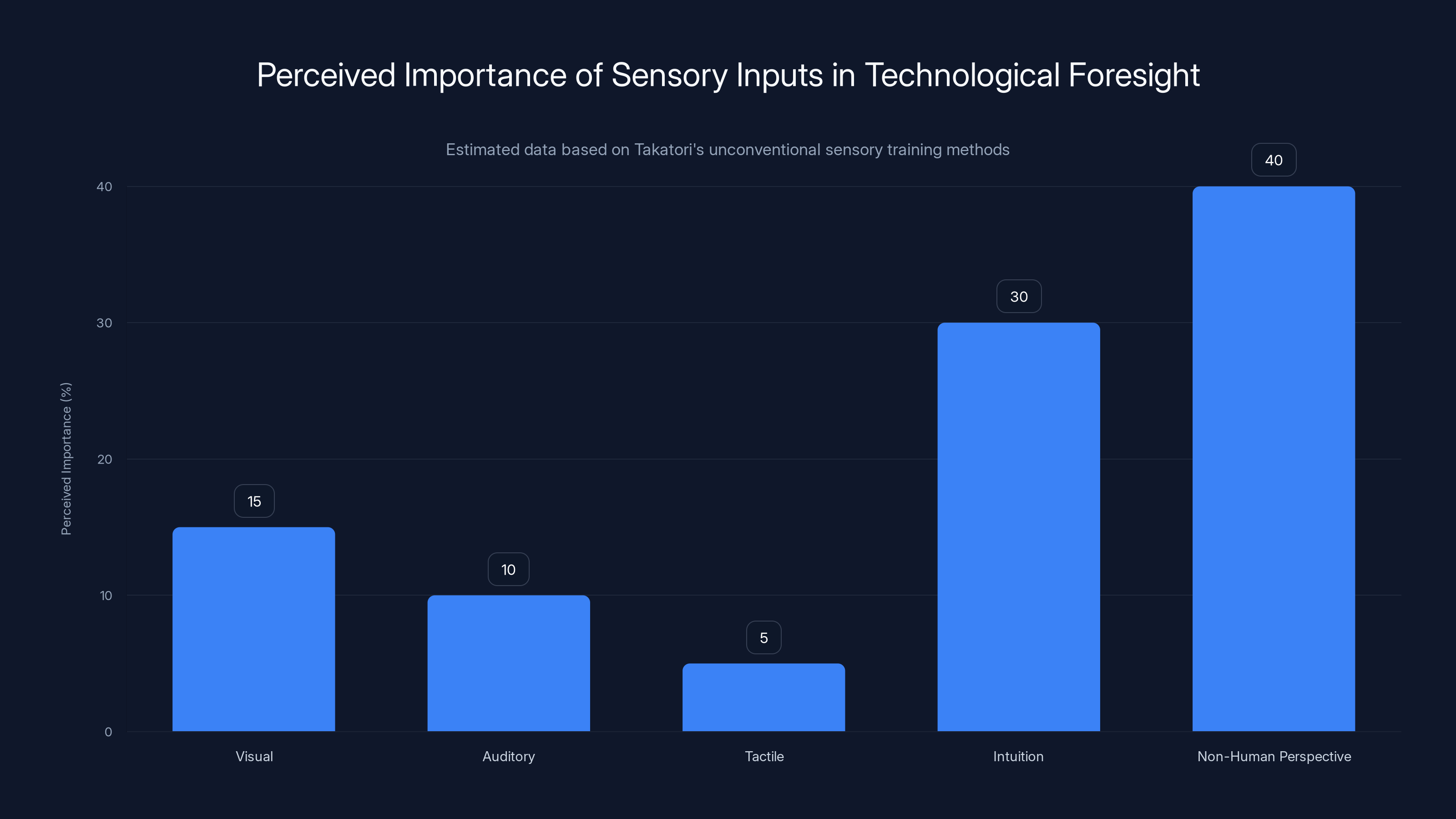

Takatori's approach emphasizes non-human perspectives and intuition over traditional sensory inputs, suggesting a unique framework for technological foresight. Estimated data.

The Evolution From Prediction to Reality: 1984 to 2026

1984: The Prediction Era

Takatori's vision was specific but unable to be implemented. The technologies didn't exist. The infrastructure didn't exist. Even the conceptual frameworks for thinking about these problems were absent.

But he saw clearly that three things had to happen:

- Computers needed to become portable (not just mobile)

- Computers needed to become emotionally intelligent

- Computing needed to embed into physical environments

All three required solving the natural language problem first. You can't have emotional intelligence without understanding language. You can't have useful personification without conversation. You can't make computers portable and intuitive without moving beyond keyboard interfaces.

1994-2004: The Infrastructure Building Phase

During the 1990s and 2000s, the infrastructure for Takatori's vision was being built:

- Networks became ubiquitous (internet expansion)

- Computing power became cheap (Moore's Law acceleration)

- Data became digitized (text databases, image libraries)

- Early machine learning emerged (neural networks being researched)

- Smartphones appeared (though not yet with AI)

But the crucial missing piece remained: natural language understanding at scale. Without it, emotional intelligence was impossible.

2012-2026: The Deep Learning Revolution

The deep learning revolution changed everything. Starting with AlexNet in 2012, then progressing through GPT-2, GPT-3, and beyond, systems finally achieved natural language understanding sophisticated enough to approach what Takatori envisioned.

Now, in the 2020s, all of Takatori's predictions have become practical:

- Portable AI devices: Every smartphone runs a personified AI assistant

- Embedded computing: Smart homes, wearables, cars—computing is in the walls

- Emotional intelligence: Modern AI systems understand context, adapt tone, remember preferences

- Natural interfaces: Voice, multimodal input—no keyboards required

Takatori's vision isn't theoretical anymore. It's your daily reality.

What's Still Missing

There's one Takatori prediction we haven't fully implemented: the seamless integration of all three. We have portable personified devices, we have embedded computing, we have emotional AI. But they don't yet work as a unified system the way Takatori imagined.

Your phone has personality, but your smart home is usually dumb (you control it, it doesn't adapt to you). Your Alexa device has personality but limited personification (it can't learn from you the way it should). Integration across all your devices is clunky.

The next phase of Takatori's vision is exactly this integration: a unified system where your personified AI companion understands your entire environment, learns your preferences across all devices, and coordinates everything from your phone to your home to your car.

We're in the middle of building this right now.

Lessons for Modern Builders: Applying Takatori's Methodology

Takatori's approach offers something valuable for anyone building technology today. His framework for foresight is systematic and learnable.

Start With Human Needs, Not Technology

Takatori didn't start by asking "what can computers do?" He started by asking "what do humans need?" His answer was emotional understanding. Everything else flowed from that.

Modern product development often inverts this. We start with a technology (neural networks, blockchain, whatever) and ask how to apply it. Takatori would have been skeptical of this approach.

The practical lesson: before you build, articulate what human need you're solving. Not the feature. The need. What's the emotional or existential problem someone has? That becomes your design north star.

Practice Perspective-Taking Deliberately

Takatori trained his sixth sense. He didn't assume it would develop naturally. He set aside time to think from different perspectives, to see through non-human sensory frames, to imagine futures vividly.

You can apply this in your work:

- Weekly futures writing: Spend an hour writing a detailed scenario of how your product/service might be used in five years

- Adversarial review: Bring in someone skeptical and let them pick apart your assumptions

- Cross-disciplinary conversations: Talk to people from completely different fields about your problem

- Ethnographic observation: Actually watch people use your product in their real lives, without them knowing what you're watching for

Each of these is practicing perspective-shift. Each one makes your intuition about the future sharper.

Build for Emotion, Not Just Function

Takatori insisted that computers needed to greet users "with sincere feelings." This isn't luxury. It's essential.

When you design a system, consider:

- Tone: Does it sound like it's listening to you?

- Memory: Does it remember you? Your preferences? Your context?

- Adaptation: Does it change based on your mood, your situation?

- Respect: Does it treat your time, privacy, and preferences with genuine care?

These aren't nice-to-have. They're what differentiate systems that work from systems that feel like chores.

Think in Multiple Modalities

Takatori forced himself to think through multiple sensory frames. Modern design should do this systematically:

- Mobile first, then desktop, then wearable

- Voice first, then touch, then gesture

- Text first, then images, then video

- For different ability profiles: visual, auditory, motor, cognitive

Each modality reveals something different about your problem. When you've thought through all of them, your understanding becomes more complete.

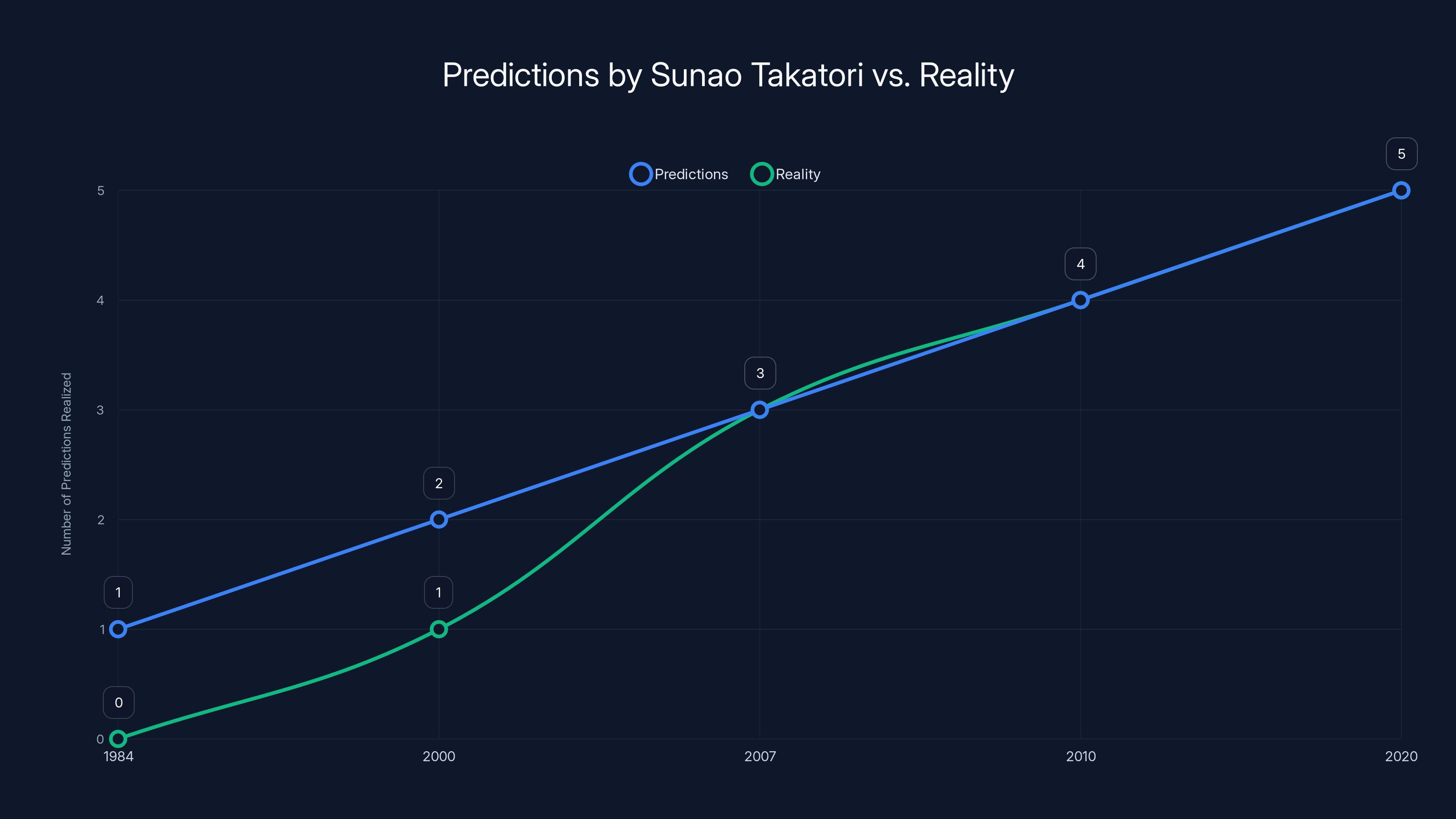

Sunao Takatori's predictions about technology, such as smartphones and AI, were remarkably accurate, with many becoming reality decades later. Estimated data.

The Takatori Moment: When Prophecy Becomes Present

There's a specific moment when a long-range prediction stops being interesting history and becomes immediate relevance. That moment is now.

Takatori predicted that the future would have personified computers that understood emotion, portable devices without keyboards, embedded computing, and AI companions. We now have all of these. But we're not yet good at them. We're at the beginning of integration.

The question Takatori would ask now: "What's the next version of emotional intelligence in computing? What will personified AI look like when it's not just conversational, but deeply integrated into every part of our lives?"

His methodology suggests the answer. Develop the sixth sense through deliberate practice. Imagine vividly how people will want to interact with technology five years from now. Don't start with the technology. Start with the human need. Make emotion and understanding foundational, not optional.

Takatori showed us how to think about computing's future. Now we're finally in the era where his thinking can become fully real. The question is whether we'll have the wisdom to implement it the way he envisioned.

Conclusion: The Vindication of the Sixth Sense

Sunao Takatori wasn't magical. He wasn't a prophet with mystical insight. He was methodical. He trained his intuition the way an athlete trains their body.

He walked through Tokyo on all fours to see like a dog. He swam in the ocean to perceive like a dolphin. He imagined invisible entities and thought about how they'd experience his software. These weren't eccentric hobbies. They were training exercises for the part of the mind that sees possibilities others miss.

In 1984, when most computing visionaries were predicting faster machines and better interfaces, Takatori predicted that the real future was about emotional intelligence and personification. He predicted portable computers without keyboards. He predicted embedded computing in homes. He predicted AI companions that would greet you with sincere feelings.

He was right about all of it. And the vindication is complete now that we've finally built the infrastructure to make his vision real.

But here's what matters most: Takatori's methodology is replicable. The sixth sense isn't mystical. It's trainable. It requires perspective-taking, emotional design thinking, multimodal analysis, and the discipline to imagine futures vividly and specifically.

Anyone building technology today can apply his framework. Start by understanding what humans actually need emotionally. Practice thinking from radically different perspectives. Design for emotion as a core function, not decoration. Think multimodally. Train your intuition deliberately.

Do that, and maybe in 40 years, your predictions will be half as accurate as Takatori's. That would be an extraordinary achievement.

The Japanese engineer who nobody paid attention to in 1984 understood our world in 2026 better than the celebrated visionaries of Silicon Valley. His vindication is now complete. The question is: what will we build with this lesson?

FAQ

Who was Sunao Takatori and why does he matter?

Sunao Takatori was a Japanese software designer and founder of Ample Software who, in 1984, made remarkably accurate predictions about the future of computing. He predicted personified AI, smartphones without keyboards, smart homes, and emotional intelligence in computers decades before these became reality. He matters because his methodology for technological foresight was systematic and replicable, and because his predictions have proven more accurate than those of more celebrated Silicon Valley figures.

What did Takatori mean by his "sixth sense"?

Takatori's "sixth sense" wasn't mystical. It was a deliberately trained capacity to perceive technological possibilities through multiple sensory and cognitive frames simultaneously. He trained it by practicing perspective-shifts: seeing the world through a dog's eyes, perceiving like a dolphin, imagining how invisible entities would experience his software. This forced his brain to develop new attention models and integration patterns that generated insights about future technologies.

How did Takatori predict smartphones 23 years before the iPhone?

Takatori specifically predicted "a portable, yet not necessarily mobile personal computer without keyboards and monitors." This description perfectly matches smartphones: devices that are portable (fit in your pocket), not necessarily mobile (used while stationary), without traditional keyboards or separate monitors, controlled through touch and voice. He understood the category definition more precisely than most people did even after smartphones existed.

What was Takatori's vision for AI and emotional intelligence?

Takatori believed that computers would eventually need to "greet the user with sincere feelings" and understand human emotion to be truly useful. He predicted that AI would become increasingly "personified"—not just functional, but capable of emotional understanding, memory of user preferences, and appropriate emotional adaptation. Modern AI assistants like ChatGPT and Claude are implementing exactly this vision.

How does Takatori's multimodal thinking relate to modern AI?

When Takatori trained himself to perceive through multiple sensory frames (dog vision, dolphin perception), he was developing what modern AI calls multimodal understanding: systems that process text, images, audio, and video simultaneously with different perceptual weights. GPT-4o, Claude 3.5, and modern foundation models do mathematically what Takatori practiced cognitively. He was 40 years ahead on the conceptual framework for multimodal intelligence.

Why was Takatori ignored if his predictions were so accurate?

Takatori's vision was about 30-40 years ahead of the infrastructure needed to implement it. Natural language processing, deep learning, computational power, and networked data—all prerequisites for personified AI—didn't exist in 1984. Additionally, he was working in Japan, not Silicon Valley, so the American tech narrative didn't amplify his work. Being right too early is sometimes indistinguishable from being wrong, since the predictions can't be implemented in real-time.

How can I apply Takatori's methodology to my own work?

Takatori's system was: (1) Start with human emotional needs, not technology, (2) Practice perspective-taking deliberately through structured exercises, (3) Design emotion as a core function, not decoration, (4) Think multimodally—through voice, text, images, and different ability profiles, (5) Train your intuition through vivid, specific future scenarios. None of this requires special gifts. All of it is trainable.

What's the difference between Takatori's vision and what we have now in 2026?

We now have all the individual components Takatori predicted: portable personified devices (smartphones), embedded computing (smart homes), emotional AI assistants. What we're still building is the seamless integration of all three into a unified system that works together intuitively. That's the next phase of his vision, and we're in the middle of implementing it now.

How does Takatori's approach differ from Silicon Valley visionaries like Jobs or Gates?

Jobs and Gates predicted the future of computing from within the computing paradigm (faster machines, better interfaces, more capability). Takatori predicted the future by stepping outside human-centered thinking entirely. He imagined how AI might understand the world, not how humans might use machines more efficiently. This perspective shift gave him a more accurate view of what would eventually matter.

Final Thoughts

The world Takatori imagined in 1984 has largely arrived. What remains is the deeper question: now that we have the technology, will we build it with his wisdom about emotion, empathy, and the importance of training our intuition about human needs? That's the choice we face in 2026.

Key Takeaways

- Sunao Takatori predicted personified AI, smartphones without keyboards, and smart homes in 1984, decades before they became reality

- His methodology for developing the sixth sense was systematic and trainable: perspective-shifting, emotional design thinking, and multimodal analysis

- Takatori trained his intuition by deliberately adopting non-human sensory frames, effectively developing multimodal perception 40 years before multimodal AI became standard

- Modern AI systems implementing emotional intelligence, voice interfaces, and integrated smart home ecosystems are all fulfilling Takatori's 1984 vision

- The lesson for modern builders: start with human emotional needs, practice perspective-taking deliberately, and design emotion as a core function, not decoration

Related Articles

- AI Chatbot Dependency: The Mental Health Crisis Behind GPT-4o's Retirement [2025]

- Voice: The Next AI Interface Reshaping Human-Computer Interaction [2025]

- AI Glasses & the Metaverse: What Zuckerberg Gets Wrong [2025]

- Why Gen Z Is Rejecting AI Friends: The Digital Detox Movement [2025]

- UniRG: AI-Powered Medical Report Generation with RL [2025]

- Google's Hume AI Acquisition: The Future of Emotionally Intelligent Voice Assistants [2025]

![Sunao Takatori's 1984 Vision: The Japanese Visionary Who Predicted AI, Smartphones, and Smart Homes [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/sunao-takatori-s-1984-vision-the-japanese-visionary-who-pred/image-1-1770392538184.png)