Taiwan's $250B US Semiconductor Investment: What It Means for Global Tech [2026]

Last week, something genuinely significant happened in the semiconductor world, and it didn't involve a single product launch or breakthrough discovery. Instead, it was a massive bet on geography, geopolitics, and the future of where the world's most critical technology gets built.

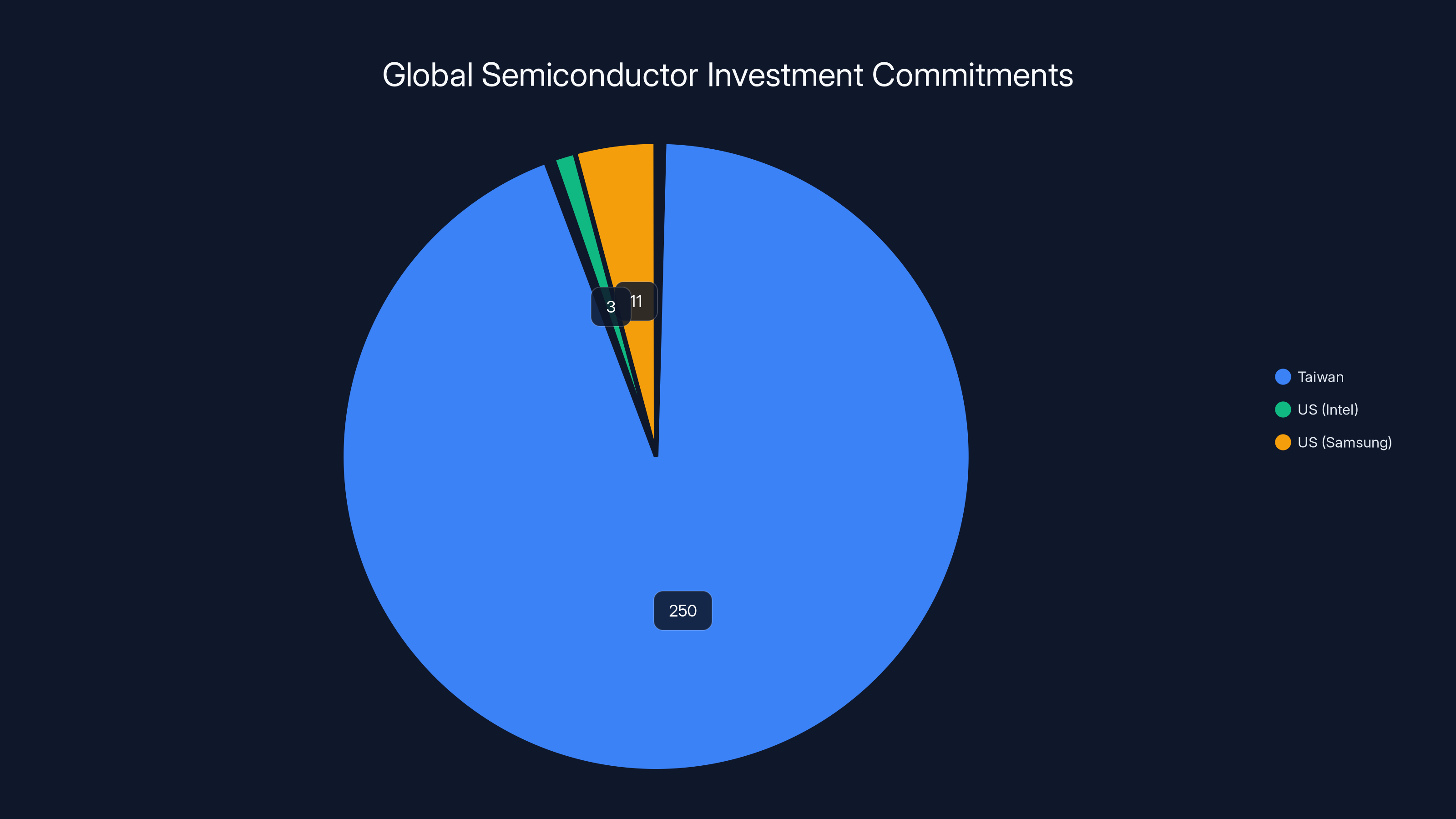

Taiwan just committed $250 billion to US semiconductor manufacturing. That's not a typo. Quarter. Trillion. Dollars.

For context, that's roughly what Intel spent building its entire global manufacturing empire over the past 30 years. It's more than the gross domestic product of 140 countries. It's the kind of money that doesn't move around lightly, which means someone believes deeply in what's happening here.

But here's the thing nobody's talking about clearly: this isn't really about semiconductors. Or rather, it is, but only on the surface. This deal is actually about power, supply chains, national security, and what happens when the world's semiconductor leader realizes it's sitting on one of the most dangerous economic vulnerabilities in modern history.

Let me break down what's actually happening, why it matters, and what comes next.

The Deal: What Taiwan Actually Committed To

On the surface, the numbers are straightforward. Taiwan's government and its semiconductor companies agreed to directly invest

So we're potentially talking about $500 billion in total capital movement from Taiwan to the United States.

The US side? The Trump administration is committing to invest in Taiwan's semiconductor, defense, AI, telecommunications, and biotech industries. No specific dollar amount was mentioned. Which is interesting. The US gets $500 billion in Taiwanese investment, Taiwan gets our commitment to "invest." That's diplomatic language for "we'll figure out what we owe you later."

The investments span semiconductors, energy, and AI production and innovation. That last part is crucial. This isn't just about fabs. It's about AI infrastructure, which means we're talking about not just chip manufacturing, but the entire ecosystem that's becoming economically fundamental.

Why Taiwan Did This (The Real Reasons)

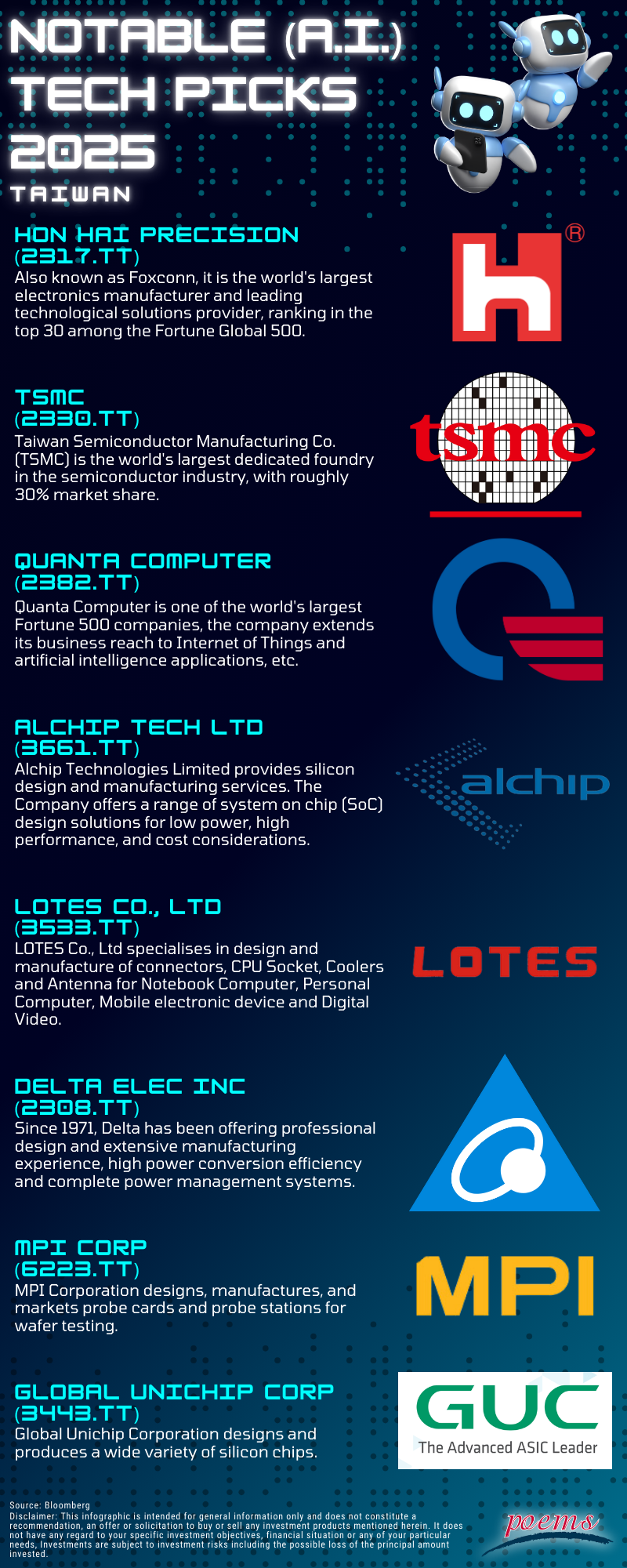

The easy answer is trade pressure. The Trump administration has been extremely clear about wanting to reshape global supply chains and bring manufacturing home. The administration published a proclamation the day before announcing this deal that practically screamed the strategy: only 10% of semiconductors are currently produced in the United States.

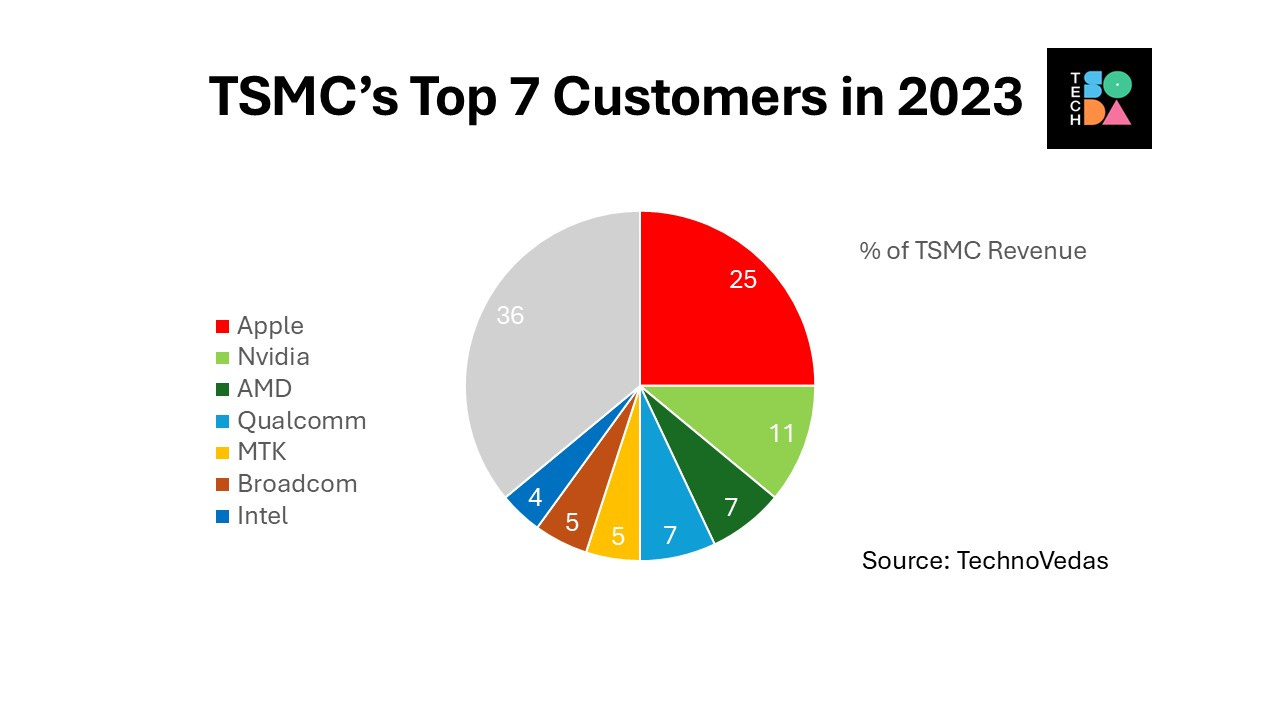

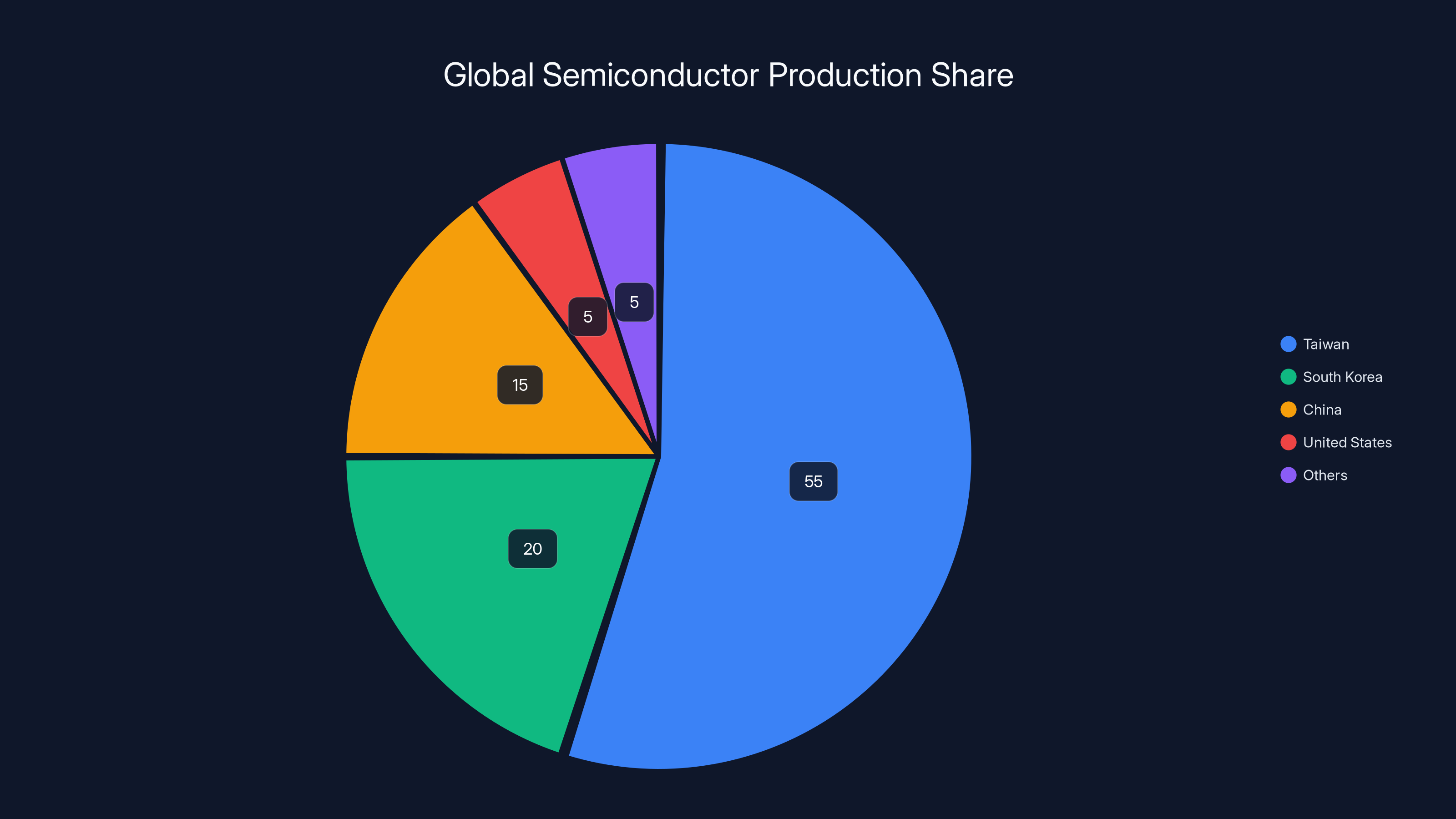

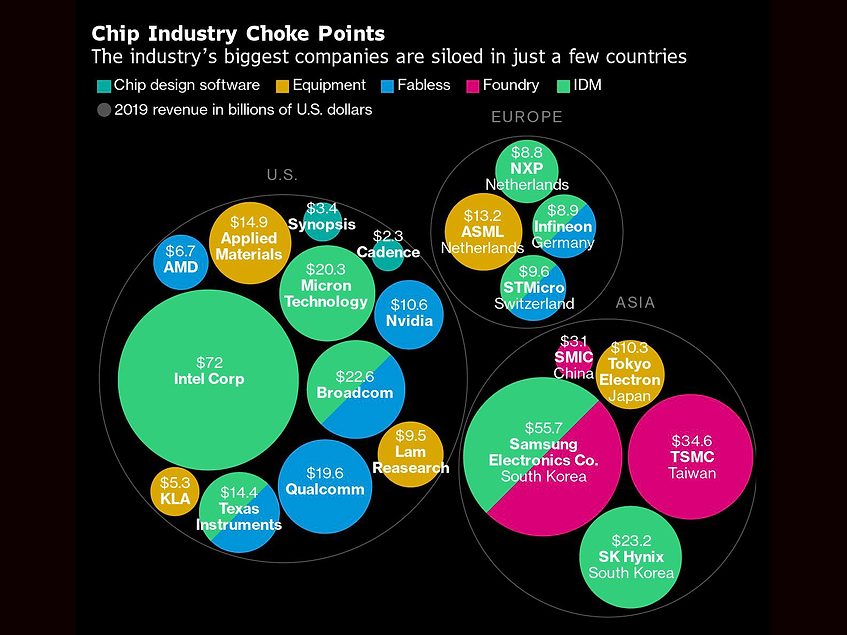

That's the vulnerability. All those chips powering everything from iPhones to military systems? They come from abroad. Taiwan produces more than half of the world's semiconductors. South Korea makes most of the rest. If you're a national security strategist, that's a nightmare scenario.

But the deeper reason Taiwan did this is actually self-preservation. Taiwan's entire economy depends on semiconductor exports. The US is the largest market for semiconductors globally. If the US decides to reshape its supply chain without Taiwan, Taiwan loses its biggest customer and its geopolitical leverage simultaneously.

By committing $250 billion to US manufacturing, Taiwan is essentially saying: "We're too important to cut out. We're investing in your security. We're part of your economic future. Don't rebuild your supply chain without us."

It's smart. Maybe brilliant. They're not just keeping their current business. They're entrenching it deeper into the US economy.

What the US Gets Out of This

Officially? Domestic semiconductor manufacturing capacity. A 25% tariff on advanced AI chips headed to China was announced simultaneously with this deal. The message is clear: the US is trying to decouple from foreign semiconductor dependence while simultaneously preventing Chinese access to cutting-edge chips.

But there's more. Every fab Taiwan builds in the US creates American jobs. Every semiconductor dollar spent domestically stays in the domestic economy. Every new facility represents intellectual property staying within US borders and subject to US law.

From a national security perspective, this is huge. If a war broke out with China tomorrow, the US would have domestic chip production capability. That's not something most countries can say. Taiwan can say it now in two places.

There's also the geopolitical message. By making this deal with Taiwan directly, the US is signaling that it recognizes Taiwan as an independent economic actor worthy of direct trade agreements. The US doesn't formally recognize Taiwan as a nation, but apparently it recognizes their ability to write $250 billion checks.

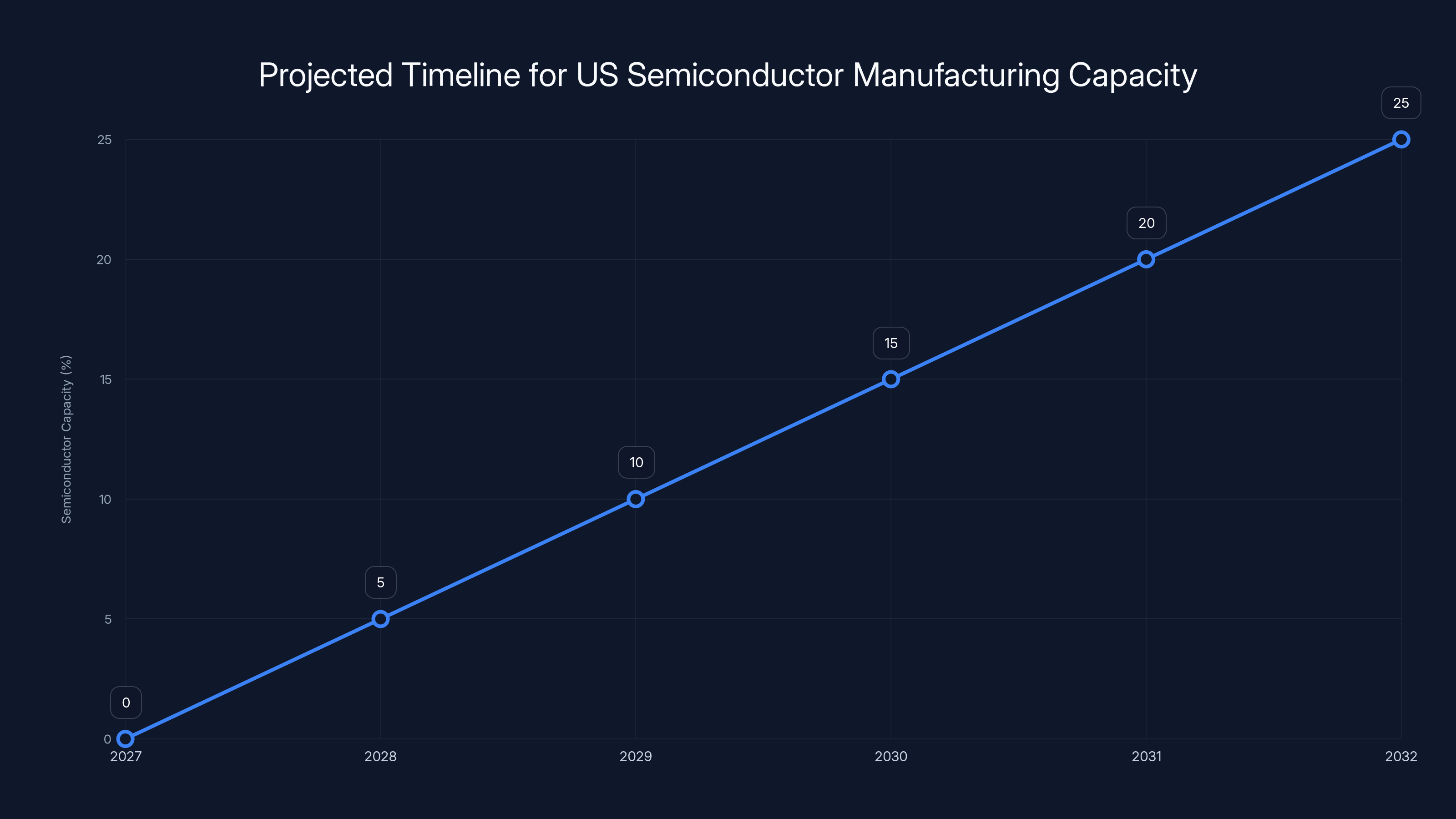

Estimated data shows US semiconductor capacity increasing from 2027, reaching meaningful levels by 2031. Estimated data.

The Semiconductor Supply Chain Problem

To understand why this deal matters, you need to understand just how broken and dangerous the current semiconductor supply chain actually is.

Right now, here's basically how it works: Taiwan and South Korea produce the vast majority of cutting-edge semiconductor chips. China produces mid-range chips but increasingly wants to move into high-end production. The US designs chips, owns the software ecosystem, and controls most of the chip design tools and semiconductor manufacturing equipment companies.

It's a globally distributed supply chain that assumes peace, frictionless trade, and no major geopolitical disruptions. None of those assumptions look good right now.

Taiwan's Concentration Risk

Taiwan produces more than half the world's semiconductors. More specifically, Taiwan produces the vast majority of cutting-edge, advanced semiconductors. If something happened to Taiwan, the global semiconductor market wouldn't just be disrupted. It would be destroyed.

My company relies on semiconductors. Your company relies on semiconductors. The military relies on semiconductors. The power grid relies on semiconductors. Your car relies on semiconductors. The global economy is fundamentally dependent on a small island producing more than half the world's chips.

That's not a supply chain strategy. That's a single point of failure in the global economy.

There are reasons for this, mostly economic. Taiwan has spent decades building expertise, attracting talent, and investing in facilities. The regulatory environment is relatively stable. The companies are brilliant. But from a risk management perspective, it's insane.

The US Manufacturing Gap

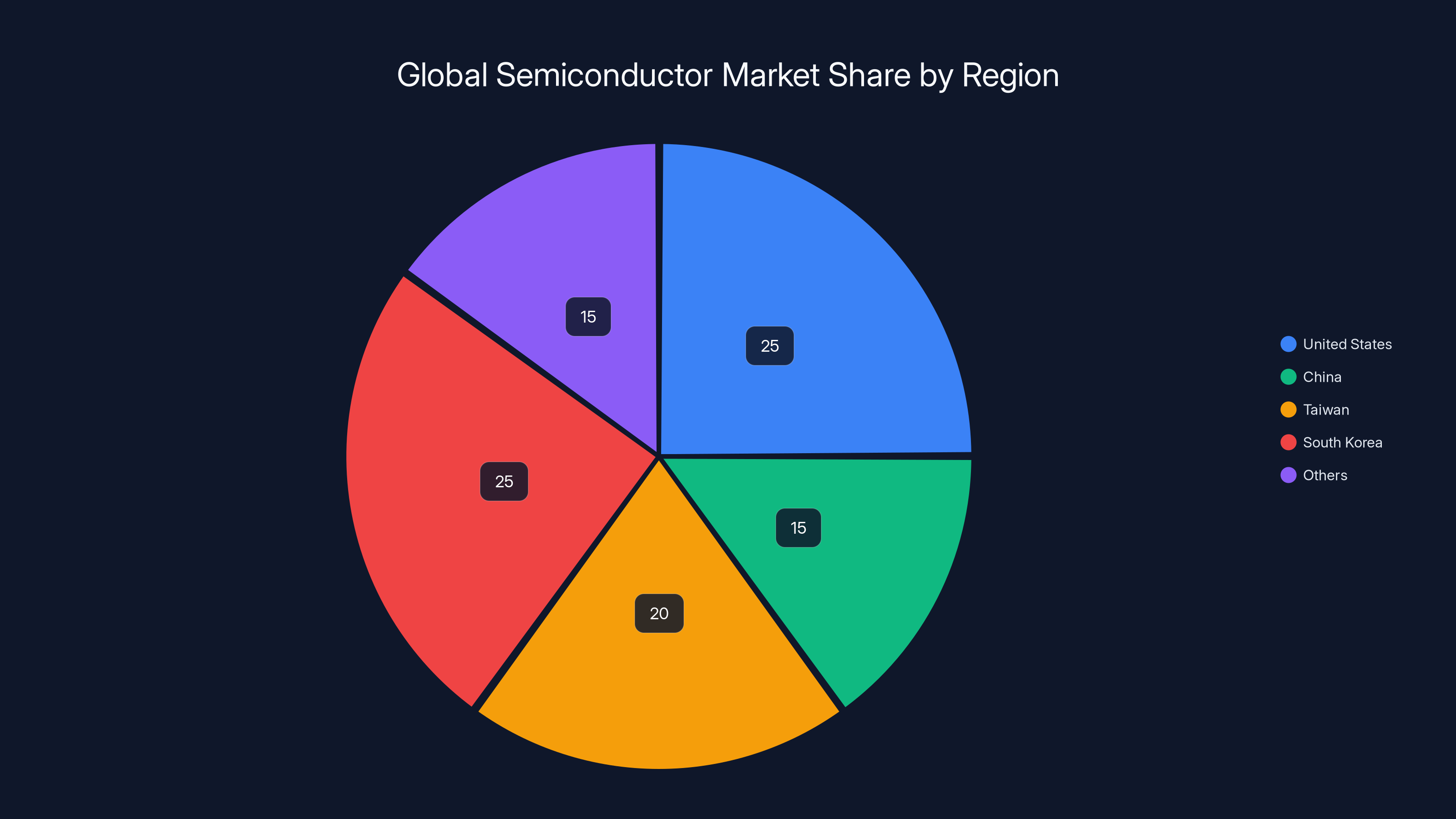

The US used to dominate semiconductor manufacturing. In the 1990s, America produced about 37% of the world's semiconductors. By 2023, that number had collapsed to around 10%.

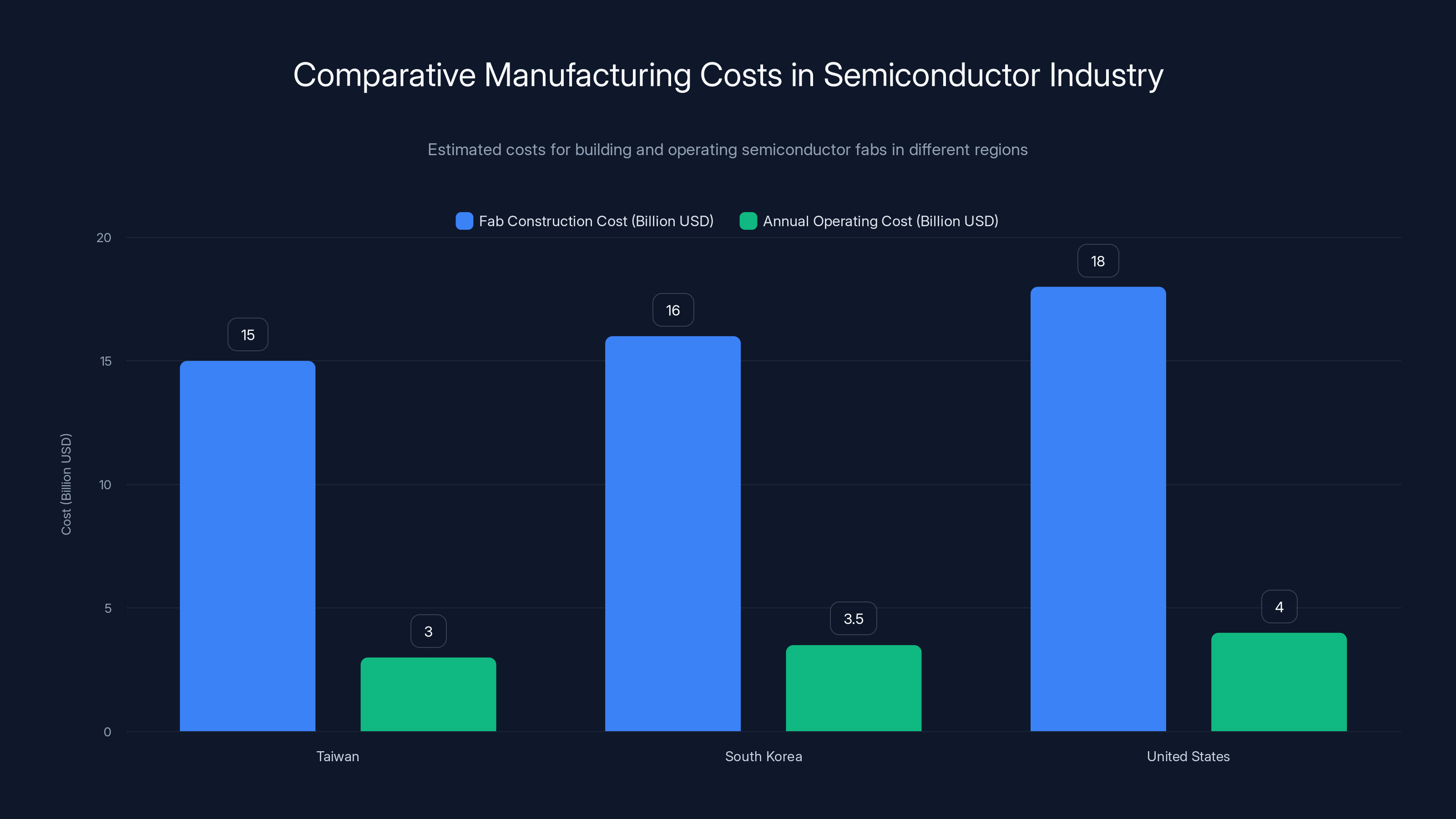

Why? Partly because companies found it cheaper to manufacture abroad. Partly because the US didn't invest in manufacturing capacity at the same rate as Taiwan and South Korea. Partly because building a modern semiconductor fab is phenomenally expensive, and US labor costs are significantly higher than in Asia.

But the real reason is that the US economy shifted toward design and software. Why manufacture chips in America when you can design them here, manufacture them cheaply abroad, and still capture most of the value?

That worked great until it didn't. Until the US realized it had surrendered control of something that's becoming more important to national security and economic power than oil ever was.

Why Semiconductors Matter Now More Than Ever

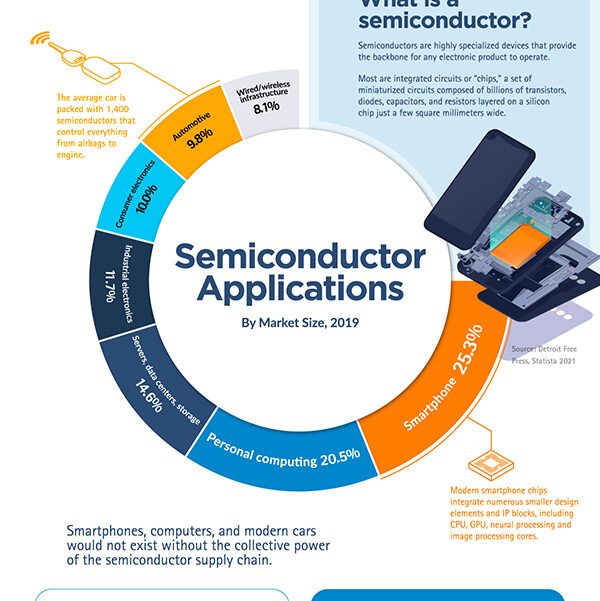

Semiconductors have always been important. But they've become critical in ways that would've been science fiction just ten years ago.

Artificial intelligence requires semiconductors. Specifically, it requires massive quantities of specialized semiconductors. NVIDIA's H100 GPUs, used in AI training, cost $40,000 per chip. Each one is a tiny monument to semiconductor sophistication.

Earth observation, satellite communications, autonomous vehicles, advanced manufacturing, military systems, critical infrastructure control, renewable energy systems, quantum computing research. It all depends on semiconductors.

But more importantly, whoever controls semiconductor production controls access to the future. If China can't get advanced chips because the US controls the supply, that's leverage. If the US can't get chips because Taiwan stops selling, that's vulnerability.

The China Question

Let's be direct. This entire deal is really about China.

The US imposed a 25% tariff on advanced AI chips headed to China. The semiconductor restrictions on Chinese companies have been getting tighter year after year. China has responded by investing billions into domestic semiconductor manufacturing, but they're behind.

This Taiwan deal is meant to accomplish several things simultaneously:

First, secure US access to the cutting-edge chips it needs for AI and military applications. Second, ensure China can't get those chips. Third, speed up US domestic manufacturing so the US is less dependent on Taiwan or South Korea if geopolitical tensions escalate.

It's a multi-layered strategy, and Taiwan's $250 billion investment is the foundation of it.

Taiwan produces over half of the world's semiconductors, highlighting a significant concentration risk in the global supply chain. (Estimated data)

What Taiwan Gets Out of This Deal

On the surface, Taiwan gets access to the world's largest market and gets to keep its largest customer dependent on Taiwanese innovation and investment.

But there's more strategic value here than just access. Taiwan gets something that's increasingly rare: relevance.

Taiwan's population is about 23 million. Its military is smaller than most of China's provinces. Its geographic position makes it vulnerable. But Taiwan's semiconductor industry makes it indispensable. This $250 billion investment doesn't just secure Taiwan's economic future. It signals that Taiwan is a permanent, essential part of the global semiconductor ecosystem.

It's hard to invade or significantly coerce a country that's building your economy's most critical infrastructure.

The Defense Angle

There's also a defense component here. By investing in US semiconductor manufacturing, Taiwan is investing in US military capability. Stronger US military capability means a stronger deterrent against Chinese aggression. It's not subtle, but it's effective.

The deal specifically mentions defense as an area where the US will invest in Taiwan. That could mean money flowing back to Taiwan's defense contractors, or it could mean protecting Taiwan's security interests more directly.

Either way, Taiwan is cementing itself as a security partner, not just an economic one. That's more stable long-term than pure economics.

The Timeline Problem

Here's where things get complicated. The deal doesn't specify a timeframe. $250 billion could be invested over 5 years, 10 years, or 30 years.

That matters enormously. If Taiwan invests

The Trump administration's proclamation mentions that tariffs will continue until trade talks with other countries are complete. That implies the Taiwan deal is just the beginning. There will be negotiations with South Korea, Japan, Europe, and probably others.

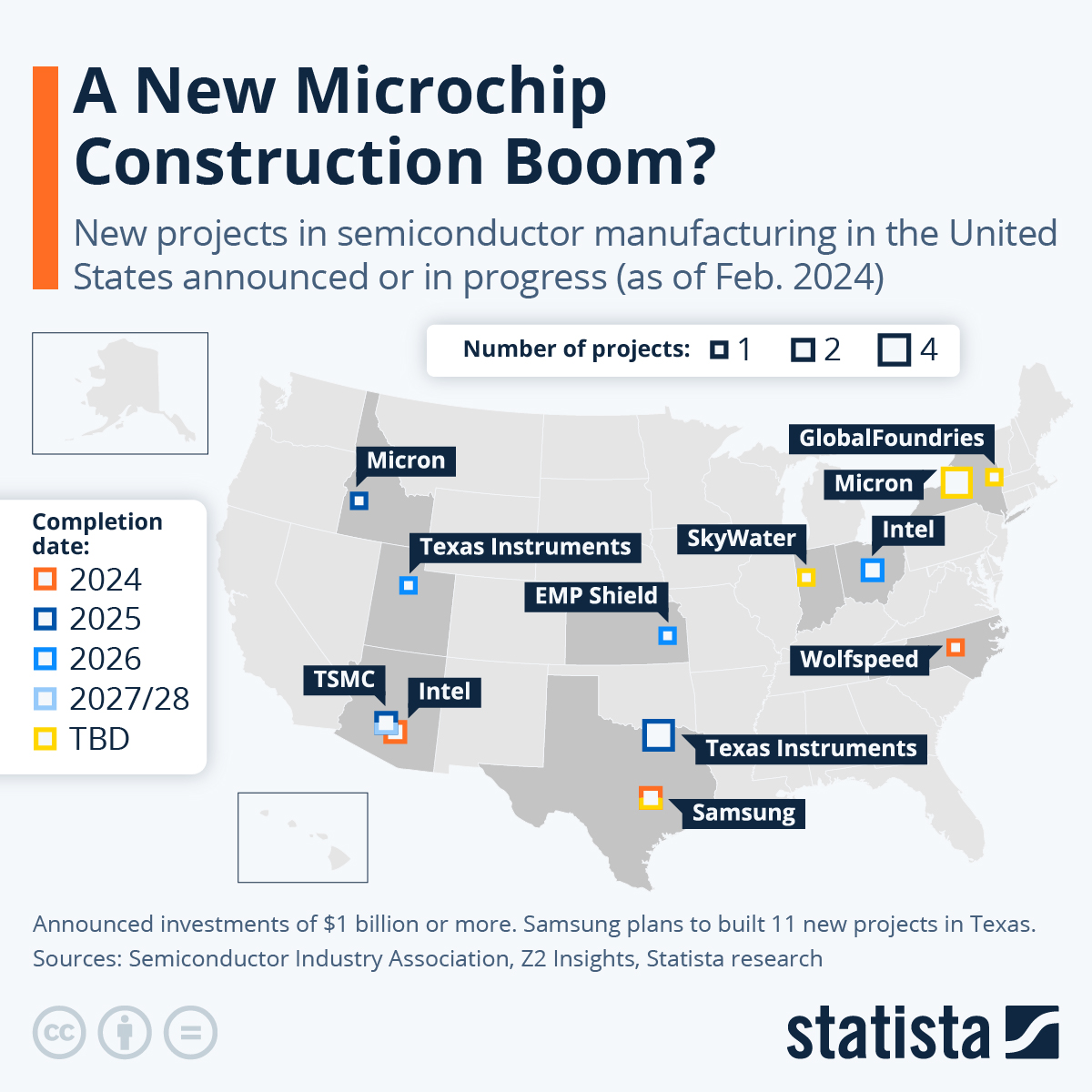

So the real timeline might look like this: negotiate with Taiwan (done), negotiate with others (ongoing), establish tariff framework (done), then invest and build.

That's probably a 3-5 year timeline to get significant US manufacturing capacity online. Which means 2029-2031 before we see real supply chain diversification.

How This Changes Global Semiconductor Manufacturing

If this actually happens, and the investments actually materialize at scale, the semiconductor manufacturing landscape transforms over the next decade.

Right now, the world's advanced semiconductor manufacturing is concentrated in three places: Taiwan, South Korea, and increasingly, China. This deal would add a fourth major player: the United States.

That's not the end of the game. But it's the beginning of the game changing significantly.

The Concentration Shift

Taiwan's share of global semiconductor manufacturing will probably stay dominant for at least another decade. They have the infrastructure, the expertise, the supply chain relationships, and the established customers.

But if US capacity increases from 10% to even 15-20% of global production, that's a fundamental shift. And if that capacity is concentrated on the most advanced, highest-value chips, the economic value shift is even more dramatic.

High-end chip manufacturing has higher margins than mass-production chips. So a US facility producing advanced AI chips and military-grade processors would be producing a disproportionate share of the semiconductor industry's profits.

The Ecosystem Impact

Building semiconductor fabs in the US doesn't just mean building fabs. It means building entire ecosystems.

You need suppliers for precision equipment. You need specialized chemicals. You need power infrastructure. You need transportation and logistics. You need skilled workers, which means you need technical education.

Each fab probably creates 3,000-5,000 direct jobs. But the indirect job creation is probably 2-3x that. You're talking about potentially 50,000-100,000+ jobs created across multiple industries if this investment actually happens at scale.

That's economically significant. It's also politically significant. Semiconductor manufacturing creates high-wage jobs in communities that need them. That votes in elections.

Taiwan has committed to a total of $500 billion in investments towards US semiconductor manufacturing, split evenly between direct investments and credit guarantees. Estimated data.

The Costs and Challenges

Here's where we need to be realistic. This deal sounds great, but executing it is brutally hard.

Manufacturing Cost Disadvantage

Semiconductor manufacturing is incredibly capital-intensive and operates on razor-thin margins. A modern fab costs

US labor costs are roughly 2-3x higher than in Taiwan or South Korea. Energy costs can be significantly higher depending on location. Regulatory compliance is more stringent, which means more expensive environmental controls.

Why would Taiwanese companies voluntarily move to a place where their costs are higher and their margins are lower?

That's where government incentives come in. The US has been offering tax breaks, grants, and subsidies for semiconductor manufacturing. The Biden administration's CHIPS Act included $52 billion in subsidies. There's probably more coming.

But subsidies don't change the fundamental economics. They just make it less painful. Every fab built in the US is operating at an economic disadvantage compared to the same fab in Taiwan.

Taiwan's committing to this anyway because the alternative—being cut out of the largest semiconductor market—is worse.

The Talent Problem

Building and running a semiconductor fab requires incredibly specialized talent. You need process engineers with years of experience. You need equipment specialists. You need quality control experts who understand the arcane complexities of sub-10-nanometer manufacturing.

Most of that talent is concentrated in Taiwan, South Korea, and to some extent, Europe. Building facilities in the US means recruiting people away from existing fabs or training new people in incredibly specialized skills.

That's possible but slow. You can't just hire 500 semiconductor engineers who don't exist yet. You have to train them, which takes years.

Which means the first wave of US fabs will probably be staffed significantly by imported talent from Taiwan. Which means the cost advantage is even smaller than the pure labor cost numbers suggest.

The Political Risk

Here's the thing about $250 billion deals: they take years to execute, and politics changes.

What if there's a different president in 2028? What if Congress changes? What if US tariff policy shifts and makes the economic case for US manufacturing weaker?

Taiwan is betting on US policy stability. That's a bet with significant downside risk.

Geopolitical Implications

Let's zoom out from the pure economics and think about what this deal means geopolitically.

Taiwan's Position

This deal cements Taiwan's position as a critical economic partner to the US. It's not formal diplomatic recognition—the US still doesn't officially recognize Taiwan as a nation. But it's something potentially more valuable: economic integration.

When two economies are deeply integrated, military conflict becomes economically devastating for both sides. Japan and Germany learned this painfully in the 20th century. By investing deeply in US semiconductor manufacturing, Taiwan is making military conflict between Taiwan and the US impossible, and making Chinese military action against Taiwan extraordinarily costly to the global economy.

That's powerful leverage.

The China Dynamic

China is watching this carefully. The US is implementing increasingly strict controls on advanced chip exports to China. This deal essentially codifies that strategy.

By ensuring the US has domestic semiconductor capacity and that Taiwan is aligned with the US, the strategy becomes sustainable long-term. The US can't be cut off from chips (because it's building them domestically and Taiwan is invested in that domesticity). China can be cut off from chips (because the entire Western semiconductor ecosystem is aligned against it).

That's a structural advantage that China can't easily counter. China can build fabs, but it's behind by roughly 5 years in advanced manufacturing. By the time China catches up, the global semiconductor ecosystem will have consolidated around US-aligned supply chains.

The Allied Network

This isn't just Taiwan investing in the US. South Korea is probably next. Japan might invest too. Intel has fabs in Europe and Ireland. Samsung has investments in multiple countries.

What's emerging is a parallel semiconductor supply chain that's explicitly aligned with Western allies and explicitly excludes China. It's not just economics. It's geopolitics.

What This Means for Tech Companies

If you run a tech company, this matters for several reasons.

First, US semiconductor costs might come down over the next 5-10 years as domestic capacity increases. That reduces your hardware costs. Or, because US fabs have higher costs, US semiconductors might cost more. The net effect depends on how much government subsidizes the difference.

Second, supply chain security becomes more possible. Instead of being dependent on Taiwan or South Korea for critical semiconductors, companies can source from the US. That's valuable if supply chain disruptions become more common, which they probably will as geopolitical tensions increase.

Third, if you're trying to build AI infrastructure or advanced computing, access to cutting-edge chips will probably become more constrained and more expensive as US policy tries to prevent Chinese access. The best chips will become increasingly politicized.

Companies building in the US will have advantages. Companies relying on Chinese chips, or Chinese companies themselves, will face increasing headwinds.

The semiconductor market is dominated by the US, Taiwan, and South Korea, with China investing heavily to increase its share. Estimated data.

The Investment Timeline and Execution

So when do we actually see this money move? That's the critical question.

The proclamation announced the deal, so presumably agreements are being finalized now. Taiwan would need to identify specific projects, secure internal approvals, and plan facilities.

A realistic timeline might be:

2026 (Now): Deal finalized, agreements signed, initial planning begins. Maybe $5-10 billion in initial commitments announced.

2027-2028: First facilities break ground. Environmental reviews, site preparation, equipment ordering. Maybe $30-50 billion spent.

2029-2031: First fabs come online. Initial production begins. Maybe another $100-150 billion spent.

2032+: Facilities reaching full capacity, additional fabs announced, supply chain integrating.

So we're probably looking at 2029-2031 before we see actual, meaningful changes to US semiconductor capacity. That's far enough away that political change is definitely a risk.

The Credit Guarantees Component

One part of the deal that hasn't gotten much attention is the $250 billion in credit guarantees from Taiwan.

That's potentially huge. It essentially means Taiwan is not just investing

Where does that money come from? Probably from Taiwanese banks, international banks, and potentially government-backed lending from Taiwan.

What does it mean? It means these projects can be financed even if they're not immediately profitable, because Taiwan is taking on the credit risk.

That's a massive signal of commitment. Taiwan is not just investing money it doesn't need to invest. It's putting its financial system behind these deals.

Comparison to Previous Supply Chain Moves

This isn't the first time a country has tried to build semiconductor manufacturing capacity.

Europe has been trying for years. They've invested billions, and they produce maybe 10% of the world's semiconductors. China has been investing for decades and is still significantly behind on advanced manufacturing.

What's different about the US approach is scale, government backing, and the fact that the world's most advanced chipmakers are investing.

When Taiwan's semiconductor companies are investing in US fabs, that's not just capital. That's expertise, relationships, supply chain knowledge, and intellectual property.

That makes success more likely than previous regional manufacturing attempts.

The US faces higher semiconductor manufacturing costs compared to Taiwan and South Korea, with fab construction and operation being significantly more expensive. Estimated data.

The Economic Impact on Taiwan

Here's an interesting question: if Taiwan invests $250 billion in the US, what does that mean for Taiwan's own economy?

Taiwan's annual GDP is roughly

In the short term, it means Taiwan is investing capital that could otherwise go to domestic infrastructure, education, or other investments. That has an opportunity cost.

But strategically, it might be the best investment Taiwan could possibly make. Why? Because it ensures Taiwan remains relevant and indispensable to the world's largest economy.

Countries with indispensable economies don't get invaded. That's worth paying for.

The Semiconductor Manufacturing Complexity

When people talk about semiconductor manufacturing, they usually oversimplify it. Let me dig into why this is so hard.

Modern semiconductor manufacturing operates at scales smaller than the wavelength of visible light. You're etching transistors that are 7 nanometers across. For reference, a human hair is 70,000 nanometers thick.

You're doing this with precision that would make a watchmaker weep. A contamination particle that's a few nanometers across can destroy an entire wafer. A temperature fluctuation of 0.1 degrees can ruin production.

The equipment used in these fabs is some of the most sophisticated machinery humans have ever built. ASML, a Dutch company, makes the machines that make the chips that do almost everything. Those machines cost hundreds of millions of dollars and take years to deliver.

And that equipment? It's often not sold to China, because the US has sanctions on it. So building fabs in America means getting this equipment. Building fabs in China means figuring out how to manufacture at scale without the best equipment in the world.

That's one of many reasons China is behind.

For Taiwan to invest in US fabs, they're not just hiring American workers. They're bringing over processes, equipment suppliers, technical expertise, and knowledge of supply chains that took Taiwan decades to develop.

That expertise leaving Taiwan is probably the most valuable thing in this deal, even more than the money.

The Tariff Strategy Connection

The same day this deal was announced, the Trump administration announced 25% tariffs on advanced AI chips headed to China.

These aren't independent events. They're connected parts of a strategy.

The tariff says: "If you want to sell advanced chips in the US market, you need to either be made in the US or made by our allies."

That creates economic pressure for manufacturing to move to the US or allied countries. Taiwan's investment is the response. If other countries follow (South Korea, Japan, potentially Europe), you end up with a completely restructured global semiconductor supply chain in 10 years.

It's a strategic use of tariffs combined with incentives (subsidies) to reshape international trade and manufacturing in a way that benefits the US.

It's also somewhat reminiscent of Cold War strategies where the US used economics to create an "allied bloc" that was economically integrated and separated from the "other side."

Except instead of dividing into two competing blocs, we're dividing into three: the US-led Western bloc with strong semiconductor capacity, a Chinese bloc trying to develop independent capacity, and everyone else trying to decide which bloc to align with.

Taiwan's $250 billion investment dwarfs US commitments, highlighting a major shift in global semiconductor manufacturing strategies. Estimated data based on announced commitments.

Risks and Uncertainties

Let's be honest about what could go wrong.

Political Risk

If the Trump administration is replaced by an administration that's less focused on reshaping supply chains, policy could shift. Taiwan's investing billions of dollars based on the assumption that US policy will stay roughly constant for at least a decade. That's a big assumption.

Economic Risk

Semiconductor manufacturing operates on thin margins. If there's a recession, or if chip demand drops, these investments could become uneconomical. Taiwan would have sunk $250 billion into fabs that are losing money.

That's unlikely, but possible. Semiconductor demand is pretty stable long-term, but there can be cycles.

Technical Risk

Building cutting-edge fabs in the US at scale is technically challenging. There's no guarantee these facilities will produce chips at the same cost and quality as fabs in Taiwan. If they don't, they'll be uncompetitive.

Execution Risk

Taiwan has the capability to execute this, but so much could go wrong. Environmental opposition to new fabs. Permitting delays. Supply chain problems. Labor shortages. Any of these could slow deployment.

The Long-Term Vision

If I had to guess at what policymakers are thinking long-term, it's probably something like this:

By 2035, the world's semiconductor manufacturing is diversified across the US, Taiwan, South Korea, and Europe. Advanced chips are made in politically aligned countries. China has developed significant domestic capacity but is still behind the cutting edge.

The US is less dependent on Taiwan for semiconductors because it's building its own. Taiwan is less vulnerable to Chinese coercion because it's deeply integrated into the US economy and has made the US more dependent on it.

India is becoming a secondary source for certain semiconductor types, as another geopolitically aligned ally.

China has achieved some advanced manufacturing but faces continued restrictions on access to the newest technology and equipment.

Semiconductor supply is more stable, more distributed, and more explicitly organized along geopolitical lines.

That's not a prediction. That's what seems like the logical endpoint of the strategy being implemented right now.

What You Should Be Paying Attention To

If you work in tech, semiconductors, manufacturing, or policy, here are the things to watch:

Specific fab announcements: When do the first US fabs get announced? How many? Where? That tells you if this is real or just talk.

Talent movements: Do semiconductor engineers start leaving Taiwan for the US? That indicates whether fabs are actually being staffed.

Equipment suppliers: Do semiconductor equipment suppliers start setting up operations in the US? That indicates whether the ecosystem is actually moving.

Geopolitical response from China: How does China respond to this? Do they accelerate semiconductor investment? Attempt different coercive strategies toward Taiwan?

Other countries' moves: Do South Korea, Japan, and Europe follow with their own investments?

Cost and performance data: Once US fabs start producing, do their chips cost more or less than Taiwan's? That determines if this is economically viable.

These are the real signals of whether this deal actually reshapes the global semiconductor landscape or remains mostly aspirational.

The Broader Implications for Global Supply Chains

This isn't just about semiconductors. It's about how global supply chains are going to work for the next couple of decades.

The era of pure "offshoring to the lowest cost place" seems to be ending. The new model is "offshore to politically aligned allies with reasonable costs."

That has enormous implications for manufacturing, for trade policy, for how countries align politically and economically.

It probably means supply chains become less efficient (because you're not always making things in the lowest-cost place), but more resilient (because you're not dependent on any single geopolitically unstable region).

It probably means higher prices for consumers (because manufacturing in politically aligned countries costs more than manufacturing in the cheapest places).

It probably means more regional manufacturing capacity, less global capacity concentration.

It probably means smaller countries become more strategically important (because their alignment matters more) and larger countries become less able to coerce others (because supply chains are more diversified).

In other words, it's a pretty fundamental restructuring of how global supply chains work.

Semiconductors are just the first domino in that restructuring.

What Taiwan's Investment Really Signals

At a deep level, Taiwan's $250 billion investment is a signal about how Taiwan sees the next decade.

It signals confidence in the US commitment to semiconductor manufacturing.

It signals belief that the US market will remain critical long-term.

It signals recognition that Taiwan's safest position is being deeply integrated into the US economy and the US security ecosystem.

It signals that Taiwan wants to be a permanent, structural part of the global semiconductor supply chain, not a temporary cheap manufacturer.

It signals that Taiwan is willing to trade geographic concentration risk for economic integration risk.

Most importantly, it signals that Taiwan thinks the current global order—where trade flows freely and Taiwan can sell to anyone—is ending. The new order is one where the world divides into aligned blocs, and Taiwan wants to be firmly in the US bloc.

That's what a quarter-trillion-dollar bet really communicates.

FAQ

What does Taiwan's $250 billion investment actually fund?

Taiwan's investment directly funds semiconductor manufacturing facilities (fabs), energy infrastructure needed to power those facilities, and AI production and innovation facilities. The

Why would Taiwan invest in US manufacturing when it already dominates globally?

Taiwan is investing to ensure continued access to the world's largest market and to entangle itself economically with the US in ways that make it geopolitically indispensable. By creating dependency on Taiwanese-built US infrastructure, Taiwan gains security and leverage that pure market dominance doesn't provide.

How long will it take to see actual US semiconductor manufacturing capacity increases?

Realistically, the first facilities will break ground in 2027-2028, with initial production coming online in 2029-2031. Full capacity production would take several years beyond that. So meaningful changes to US semiconductor supply won't be visible until roughly 2031 or later, depending on the pace of construction and startup.

Does this deal mean the US will become chip-independent?

No. Even with this investment, the US will likely produce maybe 15-20% of global semiconductors by 2030-2035, up from 10% today. Taiwan, South Korea, and Europe will still produce the majority. But the US will have domestic capacity for its most critical needs, reducing vulnerability.

How does this affect semiconductor prices for consumers?

Likely upward pressure in the short term (2-5 years) as US facilities are built and ramped. Medium-term (5-10 years), it depends on whether US fabs can compete on cost. If they remain more expensive than Taiwan, prices might stay elevated. If they achieve competitive costs, prices could stabilize or decline due to more competitive supply.

What happens to Taiwan's own semiconductor industry if they invest this much abroad?

Taiwan's domestic industry remains strong because this investment doesn't replace Taiwan's manufacturing. It complements it. Taiwan will continue running its own fabs for global markets while also having stakes in US production. It's diversification, not relocation.

Could this deal fall apart if US politics change?

It's possible. These agreements typically include penalties and dispute resolution, but a fundamentally different US administration could make the investments less attractive through changed tariff or subsidy policies. However, once construction begins, facilities completed have real economic value that can't easily be abandoned.

How does this compare to previous attempts to build semiconductor capacity outside Taiwan and South Korea?

Previous attempts (in Europe, China, other regions) lacked key components: committed investment by world-leading semiconductor companies, government subsidies at scale, and alignment with military/security interests. This deal includes all three, making success significantly more likely than previous efforts.

What does this mean for Chinese semiconductor ambitions?

It makes Chinese self-sufficiency in advanced semiconductors significantly harder. By aligning Western supply chains and restricting chip access through tariffs, China faces barriers that decades of domestic investment alone may not overcome. China can build fabs, but the cutting-edge equipment and knowledge it needs comes from countries now explicitly opposing its semiconductor development.

Will this deal affect semiconductor prices in other countries?

Unlikely to significantly impact pricing globally, since this investment expands total global capacity rather than constraining it. However, if geopolitical tensions increase and supply chains become explicitly segmented (Western vs. China), that could eventually create price variations based on which countries companies source from.

How much of this money is actually new capital versus just relocating Taiwan's existing investment plans?

That's unclear from the public announcements. Some of this money would likely have been invested somewhere anyway. But the magnitude of the commitment suggests much of it is new capital specifically allocated to the US rather than other projects Taiwan might have considered. The credit guarantees particularly suggest new commitments.

What's the realistic chance this deal actually happens at the scale announced?

Moderately high for core components, but lower for the full

The Bottom Line

Taiwan just made a massive bet on the future of US-Taiwan relations and global semiconductor supply chains. It's a $250 billion signal that Taiwan believes the world is restructuring along geopolitical lines, and that Taiwan's safest position is being deeply integrated into the US economy.

That's probably correct.

What happens next depends on whether the US actually executes. If it does, we're looking at the largest restructuring of global semiconductor manufacturing in decades. If it doesn't, Taiwan's wasted a lot of money on political goodwill.

Either way, the message is clear: the era of completely globalized, politically-neutral supply chains is ending. The future is geopolitically aligned supply chains, with countries choosing sides and integrating accordingly.

Semiconductors are just the beginning.

Key Takeaways

- Taiwan committed 250 billion in credit guarantees for US semiconductor manufacturing, representing the largest supply chain reshaping since globalization began.

- US semiconductor production has declined from 37% of global share in 1990 to just 10% today, creating a critical national security vulnerability that this deal directly addresses.

- Taiwan's investment is fundamentally a geopolitical move to entrench itself as economically indispensable to the US, securing its position against Chinese pressure.

- Realistic deployment timeline shows initial groundbreaking in 2027-2028, with operational US fabs coming online in 2029-2031, meaning meaningful supply chain changes won't appear for 3-5 years.

- US semiconductor manufacturing faces structural cost disadvantages (45-50% higher than Taiwan) that government subsidies will need to bridge for fabs to remain competitive long-term.

- This deal represents the beginning of a broader restructuring where global supply chains organize around geopolitically aligned blocs rather than pure economics and lowest-cost manufacturing.

Related Articles

- Trump's 25% Advanced Chip Tariff: Impact on Tech Giants and AI [2025]

- US 25% Tariff on Nvidia H200 AI Chips to China [2025]

- AMD Radeon GPU Price Increases Coming in 2025

- Why RAM Prices Are Skyrocketing: AI Demand Reshapes Memory Markets [2025]

- Nvidia's Upfront Payment Policy for H200 Chips in China [2025]

- Intel Core Ultra Series 3: The 18A Process Game Changer [2025]