The Super Bowl Meets Silicon Valley: When Tech Money Crashes the Game

Super Bowl LIX is rolling into Levi's Stadium in Santa Clara, California this Sunday, and it's not just about football anymore. The convergence of the NFL's biggest spectacle with the world's tech capital has created something unprecedented: a collision of cultures where billionaires, venture capitalists, and Fortune 500 CEOs are bidding six figures just to sit in the stands.

What makes this particular Super Bowl different isn't the game itself. The matchup between the Patriots and Seahawks will determine a champion, sure. But the real story is happening in the luxury boxes and VIP suites, where some of the world's most powerful tech leaders are making statements about market dominance, corporate power, and the strange economics of a world where attendance at a sporting event costs more than a year of tuition at most universities.

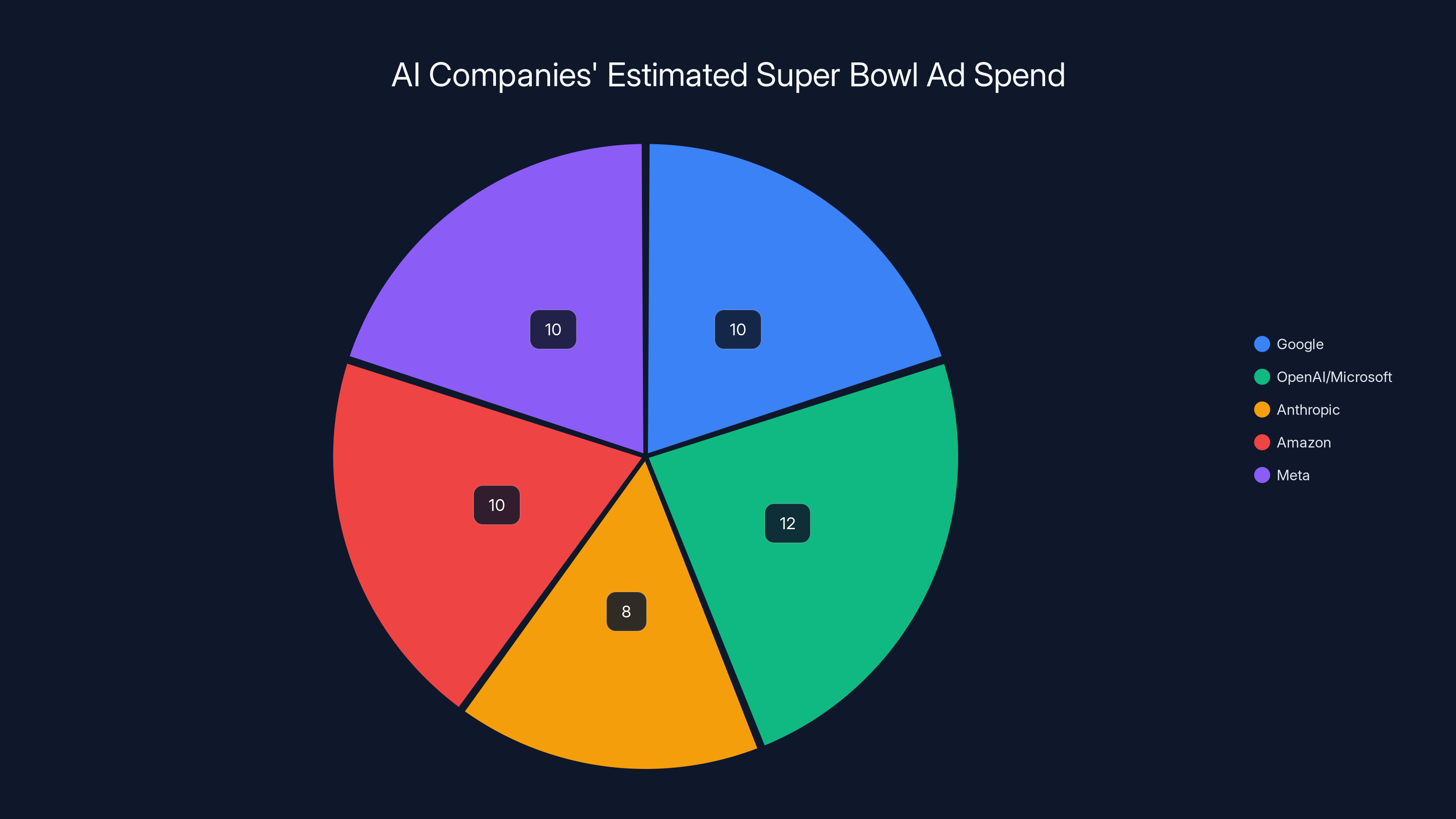

YouTube CEO Neal Mohan will be there. So will Apple's Tim Cook, who's become a fixture at the Super Bowl halftime show since Apple Music began sponsoring it years ago. Google, OpenAI, Anthropic, Amazon, and Meta are all spending millions on competing advertisements, each betting their AI narrative resonates better than the others. These aren't just corporations buying ad slots. They're making cultural statements about the future of technology, competition, and who owns the conversation around artificial intelligence.

But perhaps the most revealing observation came from venture capitalist Venky Ganesan of Menlo Ventures, who told the New York Times something that captures the absurd economics of tech wealth colliding with sports culture: the Super Bowl in Silicon Valley is basically "tech billionaires who got picked last in gym class paying $50,000 to pretend they're friends with the guys who got picked first." He added, with disarming honesty, "And for the record, I, too, was picked last in gym class."

That single quote reveals something profound about modern tech culture. These aren't athletic titans or fitness enthusiasts. They're engineers, entrepreneurs, and investors who spent their formative years not making varsity teams, but instead building the digital infrastructure that now underwrites the global economy. Now they have more money than they could ever spend, and Super Bowl tickets—priced at an average of nearly

This year's Super Bowl represents a turning point in how technology intersects with American culture. The game is no longer just about entertainment. It's become a proxy war for AI dominance, a stage for corporate posturing, and a visible reminder of the massive wealth concentration in Silicon Valley.

TL; DR

- **Average Super Bowl ticket prices hover near 50,000, making attendance predominantly accessible only to the ultra-wealthy tech elite

- Tech CEOs dominate the VIP contingent, with YouTube's Neal Mohan, Apple's Tim Cook, and leaders from Google, OpenAI, Anthropic, Amazon, and Meta all expected to attend

- Tech companies spent heavily on competing AI advertisements, signaling an ongoing arms race for AI market dominance and consumer mindshare

- Venture capitalists like Menlo Ventures' Venky Ganesan are leveraging Super Bowl attendance as a networking opportunity, particularly given their massive bets on companies like Anthropic

- This represents the third Super Bowl in Bay Area history, with the event highlighting the region's concentration of wealth and power in the technology sector

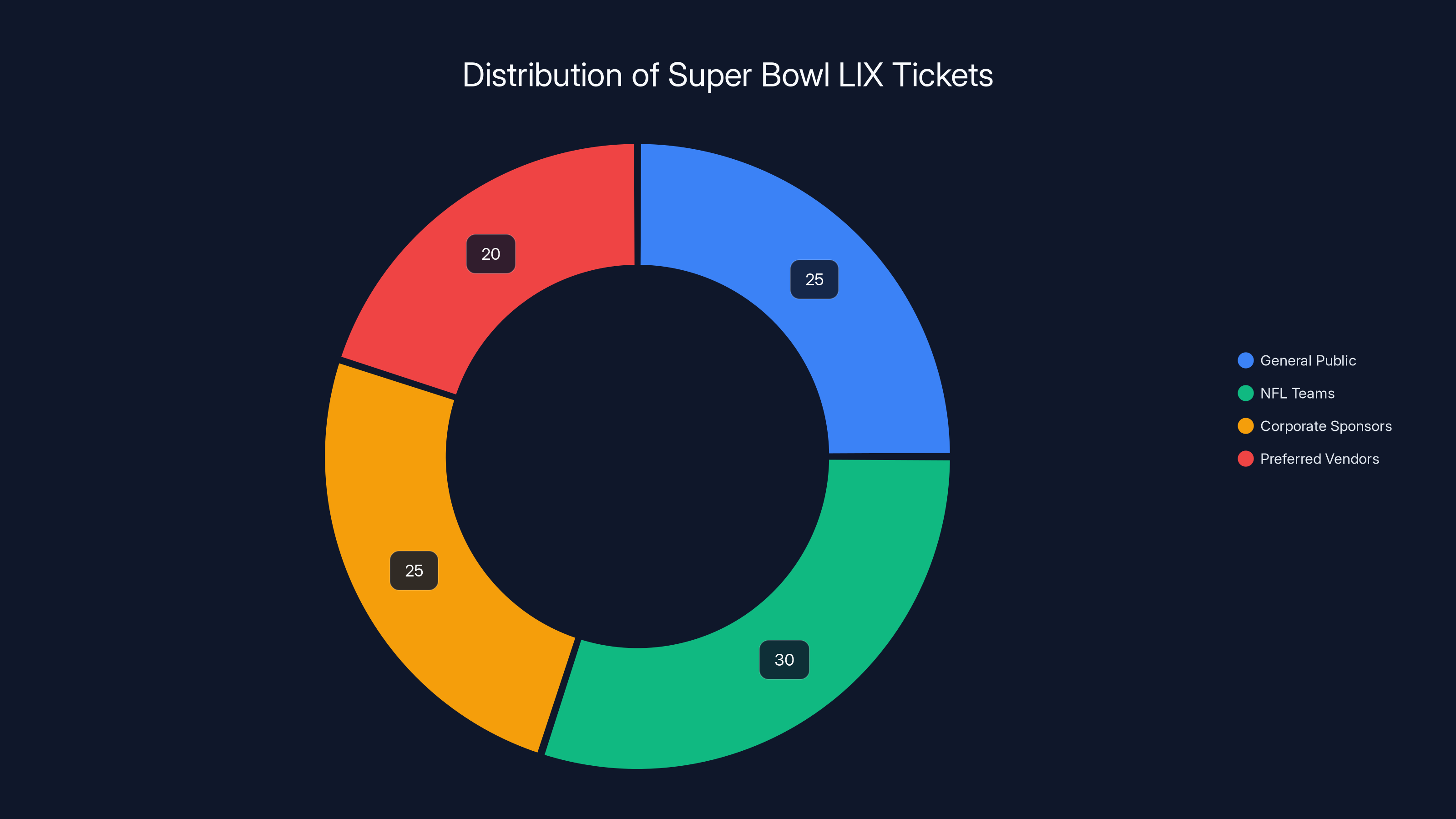

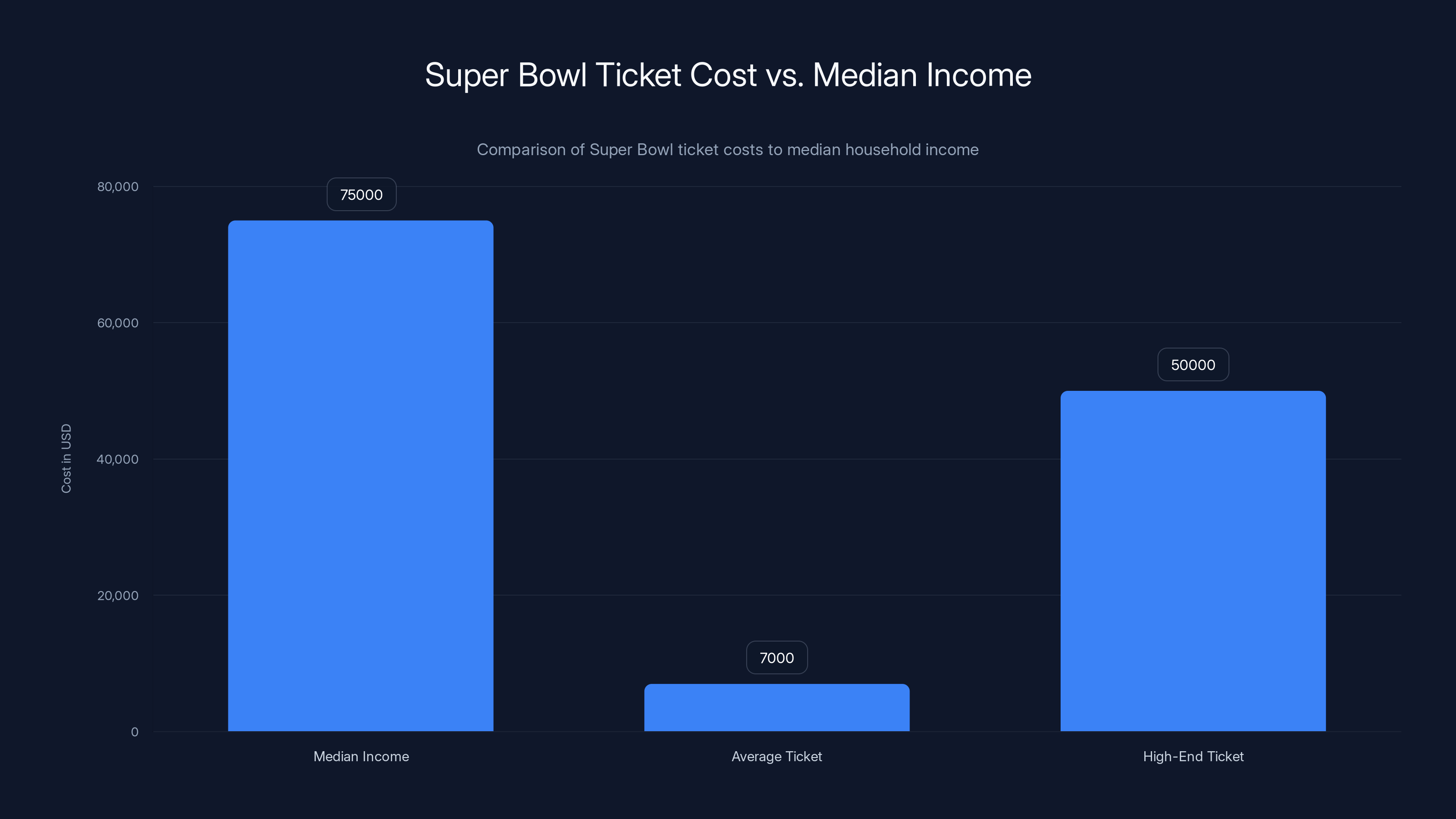

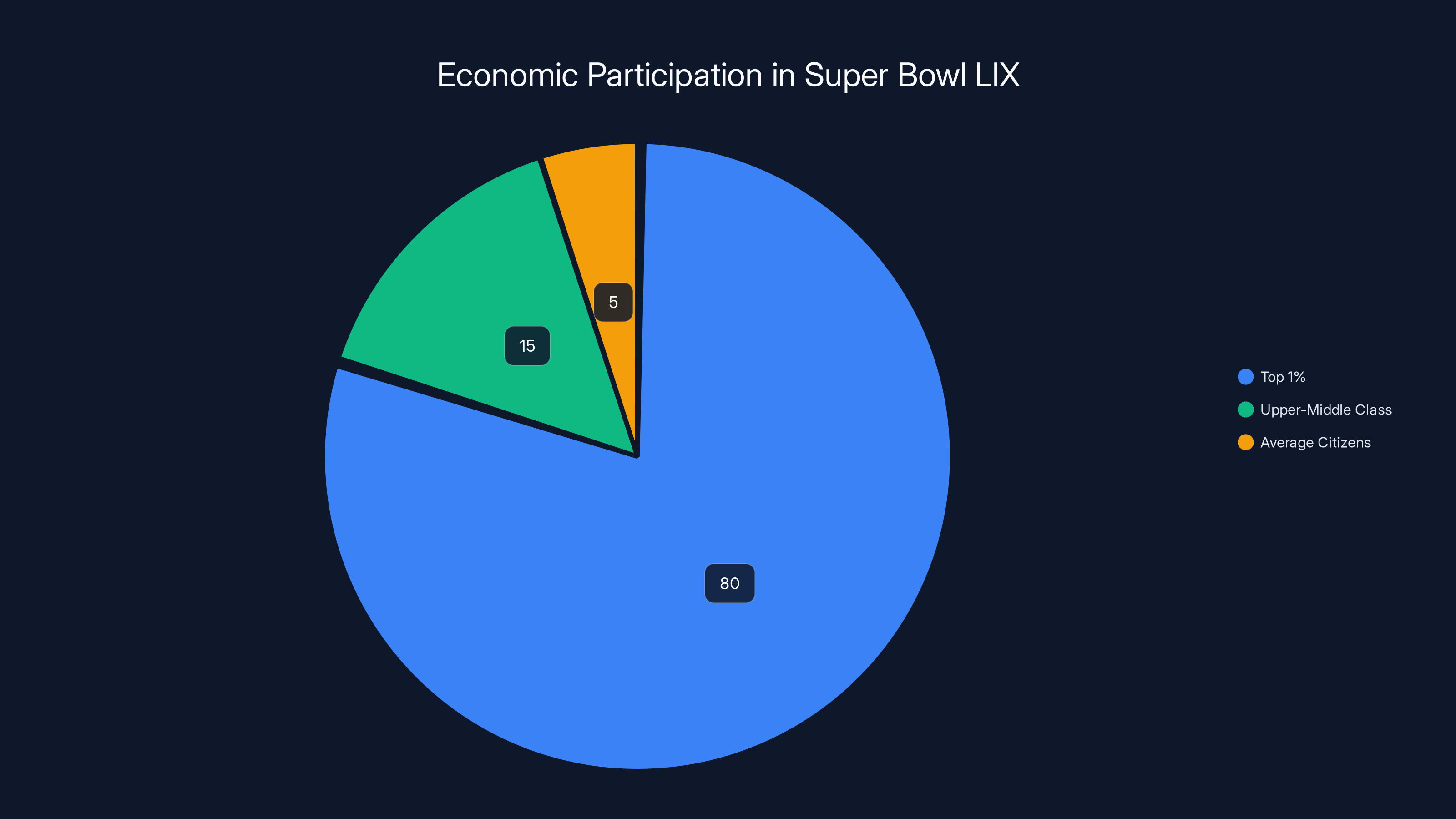

Only 25% of Super Bowl LIX tickets are available to the general public, highlighting the exclusivity and economic stratification of the event. Estimated data.

The Economics of Super Bowl Attendance: Why Billionaires Pay Six Figures for a Game

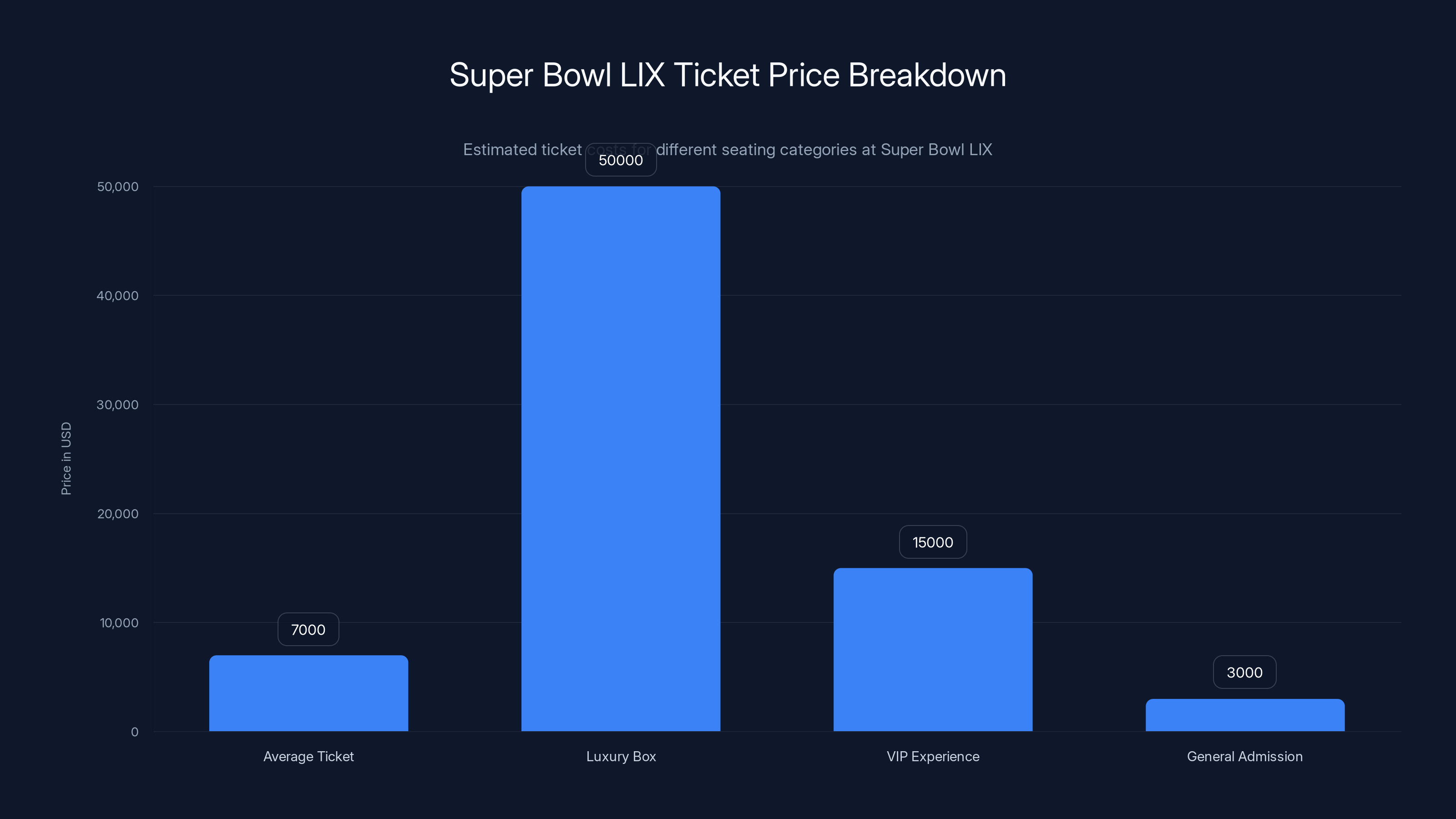

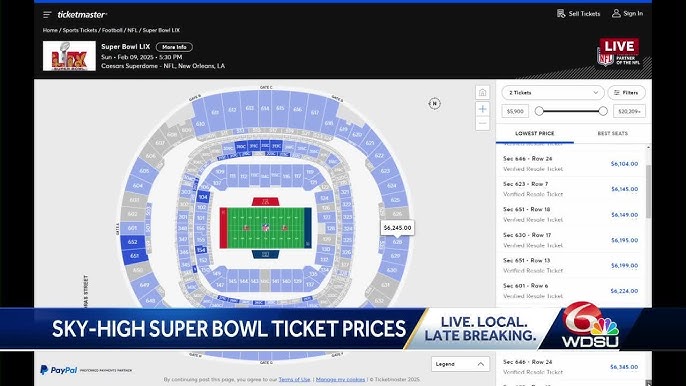

Let's talk about the actual numbers, because they're staggering. The average Super Bowl LIX ticket is going for approximately

But the real premium seats? The ones in the luxury boxes with catering, climate control, and private viewing areas? Those are hitting $50,000 and beyond. For a single ticket. For a single game.

Here's what this means economically: only the top 1% of wealth earners in the United States can casually afford to attend Super Bowl LIX. When you factor in travel, accommodations at five-star hotels in Silicon Valley (which are running

The NFL distributes Super Bowl tickets in a specific way that's worth understanding. Only about 25% of available tickets go to the general public. The rest are distributed directly to NFL teams, corporate sponsors, and preferred vendors. This means that even if you have $7,000 burning a hole in your pocket, you're competing for just a quarter of the available supply. The remaining 75% are already spoken for by organizations and corporations with direct NFL relationships.

For the Seattle Seahawks fans traveling from Washington State, this is especially frustrating. The Seahawks have won just one Super Bowl in franchise history (Super Bowl XLVIII against the Denver Broncos after the 2013 season), while the New England Patriots have won six championships, all during the Tom Brady era. Seahawks fans represent the largest single geographic group of ticket buyers at around 27% of all purchases, yet they're still constrained by limited availability and inflated pricing.

But here's the thing that really matters: for tech billionaires and venture capitalists, the cost is irrelevant. These are people who make millions per day passively. Menlo Ventures set up a

Super Bowl LIX ticket prices range from

Why Tech CEOs Actually Care About Super Bowl LIX: It's Not Just About Football

You might think tech leaders like Tim Cook and Neal Mohan attend the Super Bowl because they love football. Some probably do. But the real reason these executives are flying down to Silicon Valley this weekend is far more strategic.

First, there's the brand association angle. Apple's multi-year sponsorship of the Super Bowl halftime show has positioned the company as a cultural institution, not just a technology company. When your brand is associated with 115 million viewers watching the same moment simultaneously, that's worth incalculable amounts in marketing value. Tim Cook has understood this better than most tech leaders. By showing up consistently at Super Bowls, he's signaling that Apple is about more than just selling phones and computers. It's about culture, entertainment, and the mainstream experience.

Second, there's the dealmaking opportunity. Venture capitalists and tech CEOs spend the entire year in board meetings, investor calls, and product reviews. Super Bowl weekend in Silicon Valley offers something rare: a moment where everyone is in the same location, everyone is relaxed (well, as relaxed as billionaires get), and conversation can drift from business into the human realm. Venky Ganesan's comment about gym class dynamics captures this perfectly. The Super Bowl provides permission to have conversations that wouldn't otherwise happen in a formal business context.

Third, and most importantly, there's the AI war. Google, OpenAI, Anthropic, Amazon, and Meta are spending millions on competing advertisements during the Super Bowl. These aren't just commercials. They're statements about the future. Each company is essentially saying to 115 million Americans: "Our AI is the one you should trust." This is a proxy war for consumer mindshare that will play out over the next 5 to 10 years.

When Tim Cook sits in a luxury box at Levi's Stadium while Apple's competitors are spending tens of millions on ads trying to convince America that their AI is better, he's not just watching football. He's watching a competition unfold in real-time. He's observing how the market is reacting to competing narratives. He's making notes about which messaging resonates.

Moreover, many of these CEOs have homes within an hour of Levi's Stadium. Google is headquartered in Mountain View, just 20 minutes away. OpenAI has offices in San Francisco. Anthropic is in San Francisco. Meta's Bay Area operations are extensive. Amazon's Andy Jassy splits time between Seattle (where Amazon is headquartered) and Santa Monica, making him the only major tech CEO who's not geographically local. For the others, attending the Super Bowl isn't a travel burden. It's a Sunday afternoon in their hometown, enhanced with billionaire-level VIP access.

The Anthropic-Menlo Ventures Connection: Why This Super Bowl Matters for AI

To understand why venture capitalists like Venky Ganesan are so invested in Super Bowl LIX, you need to understand what's happening in the AI investment space.

In summer 2024, Menlo Ventures made a monumental bet. The firm set up a

Why? Because Anthropic is likely to close a

This is why Ganesan's attendance at the Super Bowl matters. He's not just watching a football game. He's part of an ecosystem that's betting trillions of dollars on AI becoming the foundational technology of the next decade. Every conversation he has with other tech executives, every observation about competing AI narratives, every piece of intelligence he gathers about market sentiment feeds back into Menlo's investment strategy.

The venture capital world operates on information asymmetry. The investors with the best intelligence, the best relationships, and the best understanding of emerging trends make the best returns. Super Bowl LIX, with all of its tech elite in close proximity for the first time this year, is basically a conference where the currency is information and the stakes are measured in billions.

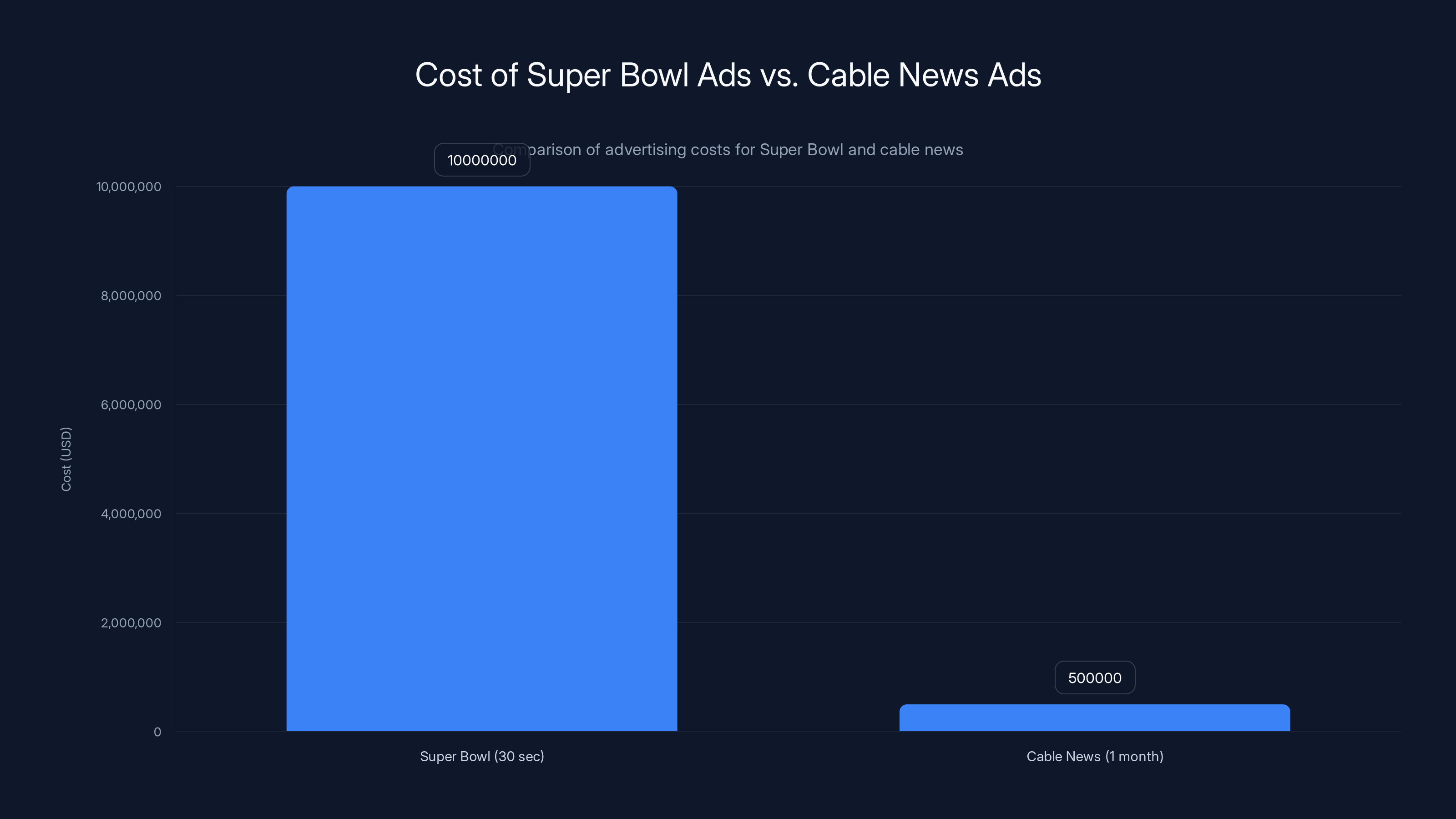

Estimated data shows major AI companies spending between

The Battle for AI Market Dominance: Super Bowl as Corporate Theater

Let's be direct: the Super Bowl is becoming a theater for the AI wars.

Google is running ads showcasing Gemini's capabilities. OpenAI (via Microsoft, which is a primary investor) is showcasing Chat GPT's latest features. Anthropic is positioned as the "safety-first" alternative in the AI space, emphasizing responsible AI development. Amazon is pushing Amazon Q, its enterprise AI assistant. Meta is promoting its Llama language models and AI integration across its platforms.

Each of these companies will spend an estimated

What's happening here is a competition for narrative control. In the early stages of a transformative technology, whoever wins the narrative often wins the market. IBM won the narrative about mainframes in the 1960s and 70s. Microsoft won the narrative about personal computers in the 1990s and 2000s. Google won the narrative about search in the 2000s. Apple won the narrative about smartphones in the 2010s.

Now, multiple companies are competing to win the narrative about AI. They understand that the consumer perception of AI will shape adoption rates, regulatory approaches, and ultimately, market size. If consumers believe Google's AI is safer, Google wins. If they believe OpenAI's Chat GPT is more capable, OpenAI wins. If they believe Anthropic's Claude is more trustworthy, Anthropic wins.

The Super Bowl, with its massive audience and concentrated cultural attention, is where these narratives get tested at scale.

What makes this year different from previous Super Bowls is the intensity of the competition. There isn't a dominant player like there was with smartphones (Apple) or search (Google). The AI market is genuinely contested. OpenAI has a first-mover advantage with Chat GPT, but it's facing aggressive competition from Google, Anthropic, and others. The outcome is still genuinely uncertain.

This uncertainty is exactly why executives are willing to pay $50,000 for a ticket and spend a weekend in Silicon Valley. They want to be where the conversation happens. They want to understand how other players are positioning themselves. They want to make connections with investors, competitors, and potential partners who might matter in the next phase of the AI revolution.

Silicon Valley's Third Super Bowl: Historical Context and What It Means

Super Bowl LIX is only the third time the Bay Area has hosted the championship game. Understanding the previous two occasions provides important context.

The first was in 1985 at Stanford Stadium, the original football facility at Stanford University. The San Francisco 49ers defeated the Miami Dolphins 38-16 in a game that's largely forgotten by casual fans but looms large in franchise history. This was during the height of the 1980s tech boom, when Silicon Valley was establishing itself as the global center for computing innovation. Personal computers were becoming mainstream. Apple was challenging IBM's dominance. The Xerox Alto and Alto II had demonstrated revolutionary GUI capabilities. The context of that Super Bowl was a region ascending into technological prominence.

The second Bay Area Super Bowl was 10 years ago at Levi's Stadium itself, when the Denver Broncos defeated the Carolina Panthers 24-10. By this point, Silicon Valley's dominance was complete. Google was a decade-old company already reshaping how humans access information. Facebook was approaching a billion users. Apple had launched the iPhone just 8 years prior and was in the process of revolutionizing mobile computing. Cloud computing was emerging as a paradigm shift. The second Super Bowl in Silicon Valley reflected a region at peak confidence, hosting the championship game in what would become the spiritual home of the Bay Area's tech community.

Now, in 2025, we're at the third Super Bowl in the region. But the context is completely different. Silicon Valley is no longer just confident about its technological superiority. It's dealing with existential questions about AI, regulation, inequality, and its role in shaping global power structures.

The evolution across these three Super Bowls tells a story about technological progress, wealth concentration, and the changing nature of power in America. In 1985, Silicon Valley was rising. In 2015, it was dominant. In 2025, it's mature, wealthy, and somewhat anxious about whether it can maintain its technological leadership in an era of AI-driven competition from other regions and nations.

The average Super Bowl ticket costs nearly 10% of the median annual household income, highlighting economic inequality. Estimated data.

The Geography of Tech Wealth: Why Your Location Matters When You're Worth Billions

One of the most overlooked aspects of Super Bowl LIX is what it reveals about how ultra-wealthy tech executives organize their lives geographically.

The fact that most major tech CEOs live within an hour of Levi's Stadium is not accidental. It's the result of decades of infrastructure development, real estate concentration, and economic clustering. Google is headquartered in Mountain View. Apple's headquarters is in Cupertino, about 20 minutes away. Nvidia is in Santa Clara, literally across the street from Levi's Stadium. Facebook (Meta) is in Menlo Park, about 30 minutes away. OpenAI and Anthropic both have major offices in San Francisco, about 45 minutes away depending on traffic.

This geographic concentration means that attending the Super Bowl isn't a major travel undertaking for these executives. It's a local event. Tim Cook could literally drive to Levi's Stadium in 20 minutes from Apple Park. This transforms the Super Bowl from a special, once-a-year pilgrimage into just another Bay Area social event, albeit one that happens to have 115 million television viewers.

But contrast this with Andy Jassy, Amazon's CEO. Jassy splits his time between Seattle (where Amazon is headquartered) and Santa Monica (where Amazon also has significant operations). For him, traveling to the Super Bowl in Silicon Valley is an actual inconvenience. He's the only major tech CEO who doesn't have a home base within an hour of the stadium. This geographic distance is revealing. It suggests that Amazon, while certainly a major tech player, hasn't invested in the same concentrated Bay Area real estate presence that other companies have.

The geography of tech wealth is also tied to the cost of living in Silicon Valley. A modest single-family home in Palo Alto or Cupertino costs

This has profound implications for innovation, regulatory influence, and political power. When tech leaders live in the same neighborhood, send their kids to the same schools, and frequent the same restaurants, they develop shared perspectives and mutual interests. This can lead to innovation clustering and economic growth, but it can also lead to regulatory capture and skewed political priorities.

The Psychology of Billionaire Networking: What Really Happens in the Luxury Boxes

Venky Ganesan's quote about "tech billionaires who got picked last in gym class" paying $50,000 to pretend they're friends with the guys who got picked first is worth unpacking psychologically.

There's a real dynamic at play here. Many of the most successful tech leaders were not the popular kids in school. They were the nerds, the outsiders, the kids who spent lunch alone writing code instead of playing sports. Steve Jobs. Bill Gates. Mark Zuckerberg. Elon Musk. These figures famously struggled with conventional social hierarchies. They found success by opting out of those hierarchies entirely and creating new ones where the skills that were irrelevant in gym class (technical ability, abstract thinking, persistence) became the most valuable traits imaginable.

Now, decades later, these same people have become richer and more powerful than anyone who ever got picked first in anything. They've inverted the social hierarchy. In the world of technology, being picked last in gym class is actually a positive predictor of success. It suggests an outsider mentality, an unwillingness to conform, and a drive to build new systems rather than succeed within existing ones.

But there's a psychological component here. Deep down, some of these billionaires probably still feel that outsider status. They've achieved beyond anyone's wildest dreams, but they're still the kids who spent Friday nights alone coding rather than at parties. The Super Bowl, packed with celebrities, athletes, and mainstream cultural figures, represents a rare moment where they can sit shoulder-to-shoulder with the people who "got picked first" in the conventional sense.

Yet here's the twist: at Super Bowl LIX, the tech billionaires are not second-class citizens. They're the ones with $50,000 tickets. They're the ones with private suites. They're the ones whose attendance matters to the event's prestige. In this inversion, they've won. They've bought their way into the in-crowd in the most literal sense possible.

This also explains why venture capitalists like Ganesan are so invested in being present. VC returns depend partially on dealmaking. The best deals happen in rooms where relationships have been built over years. The Super Bowl is a rare moment where otherwise separate power networks collide. An entrepreneur looking for Series B funding might find themselves in an elevator with the exact partner they need. A CEO might overhear a conversation that reveals what a competitor is planning. Information flows differently in social settings than in formal business environments.

Super Bowl ads can cost up to $10 million for 30 seconds, significantly more than a month's worth of cable news ads, highlighting the unique reach and cultural impact of the event. Estimated data.

The Seahawks Advantage: Why Fan Geography Matters in Ticket Economics

Twenty-seven percent of all ticket buyers are coming from Washington State to support the Seattle Seahawks. This is the largest single geographic group traveling to the game, yet it's worth understanding why this matters and what it reveals about sports economics and fan loyalty.

The Seahawks have a complicated Super Bowl history. They've won just one championship in franchise history: Super Bowl XLVIII after the 2013 season, when they defeated the Denver Broncos 43-8 in a game that's remembered as one of the most lopsided championship contests ever played. For Seahawks fans, that single victory happened over a decade ago. They want another one.

The New England Patriots, by contrast, have won six Super Bowls, all during the Tom Brady era (2001-2019). This dominance has created a different fan psychology. Seahawks fans are desperate. Patriots fans, even when their team is having a down year, have recent memories of excellence.

Ticket economics reflect fan desperation. When you haven't won a championship in 11 years, you're willing to pay premium prices to see your team get another shot. Seahawks fans represent a more desperate, more committed demographic of ticket buyers. This shows up in the data. They're 27% of all ticket purchases despite being from a less populous region than some other fan bases.

Shopping for Super Bowl tickets from Washington State also reveals something about the economics of NFL fandom. Most Seahawks fans earn significantly less than Silicon Valley tech workers. A $7,000 average ticket price represents a much larger percentage of their annual income. Yet they're buying anyway. This is fandom as sacrifice. It's a statement that the Super Bowl, the chance to see your team play for a championship, is worth any financial burden.

This geographic distribution of fans also matters for local economies. Seattle's economy will see a significant boost from fans spending money in preparation for the game. Flights from Seattle to San Francisco/Bay Area will be packed during Super Bowl week. Hotels will be fully booked. Restaurants will be crowded. Money flows from Seattle to Silicon Valley in a way that it rarely does during the regular season.

The Corporate Arms Race: Why Companies Spend Millions on 30-Second Spots

Let's talk about the actual economics of Super Bowl advertising, because they're genuinely wild.

A single 30-second Super Bowl commercial costs approximately

Why would any company pay this much? Because the Super Bowl is the only remaining moment in American culture where over 100 million people watch the same thing at the same time. In an era of streaming fragmentation, where audiences are scattered across Netflix, Disney+, TikTok, YouTube, and countless other platforms, the Super Bowl represents a rare moment of shared attention.

For a company trying to launch a new product, establish a new brand positioning, or showcase a major technological advancement, reaching 115 million people in a single moment is almost priceless. You cannot replicate that reach any other way. You could run ads on cable news, streaming platforms, and social media for months and not reach the same number of people with the same level of attention.

Moreover, Super Bowl ads have become cultural events themselves. People watch the Super Bowl partially to see the ads. There's genuine cultural discussion about which ads are the best, which ones are funny, which ones are touching. This meta-layer of attention means that the value of a Super Bowl ad extends beyond the initial viewing. The ad will be discussed, shared, and replayed on social media for weeks afterward.

For AI companies specifically, Super Bowl advertising serves an additional strategic purpose. These companies are trying to convince mainstream audiences (not just tech-savvy early adopters) that their AI is safe, useful, and trustworthy. A Super Bowl ad allows them to reach suburban parents, grandparents, and other demographic groups who rarely think about AI but will be affected by its development over the next decade. The ad serves as a reassurance that smart people are working on making sure AI is developed responsibly.

What's fascinating about this year's Super Bowl is the intensity of the AI-specific advertising. Google, OpenAI, Anthropic, Amazon, and Meta are essentially betting billions on the idea that capturing mindshare in 2025 will translate into market dominance in 2026 and beyond. They're investing in narrative control now, before most consumers have strong opinions about which AI platform they prefer.

The return on investment for Super Bowl ads is notoriously difficult to measure. Companies spend millions and then spend additional millions trying to figure out if it was worth it. Some studies suggest Super Bowl ads generate decent ROI for consumer brands like beer and cars. But for B2B companies or enterprise software companies, the ROI is murkier. That's why many major tech companies don't advertise during the Super Bowl in most years. The audiences don't align perfectly with their target customers.

But AI is different. AI is poised to affect everyone, from business professionals to teenagers to retirees. For the first time, a major tech innovation has potential mass-market relevance. This justifies the massive Super Bowl advertising spend.

Estimated data shows that the top 1% dominate attendance at Super Bowl LIX, highlighting economic inequality as average citizens are largely excluded.

The Future of Super Bowl Tech Attendance: Will This Trend Continue?

The influx of tech money into Super Bowl LIX raises a critical question: is this a permanent shift in how the tech industry intersects with sports, or is it a temporary phenomenon specific to this particular year?

There are arguments in both directions. On one hand, there are clear incentives for tech executives to attend major cultural moments. Super Bowls will always be massive cultural events. The streaming wars mean that TV audiences might be fragmenting in some areas, but the Super Bowl remains genuinely massive and genuinely countercultural in an age of fragmented media.

On the other hand, the Bay Area hosting the Super Bowl is a unique circumstance. If the Super Bowl had been held in Miami or Las Vegas, we might not have seen this concentration of tech leadership. The geographic proximity matters. If the next Super Bowl with significant tech company participation is held in Detroit, Dallas, or another non-tech hub, we might see a different pattern of attendance.

There's also the question of whether

Moreover, the current Super Bowl attendance pattern reflects the peculiar concentration of tech wealth in 2025. If wealth becomes more distributed across regions over time, or if the center of tech innovation shifts away from Silicon Valley, the composition of Super Bowl attendees will change.

What seems likely is that Super Bowl attendance will remain a status symbol for tech leaders, at least in the near term. The nexus of football, culture, and massive global attention is rare. Tech leaders will continue to view Super Bowl attendance as a valuable networking opportunity and a way to signal cultural sophistication alongside technical excellence.

The Inequality Question: When a Single Ticket Costs More Than Median Income

Here's the uncomfortable truth beneath all of this: Super Bowl LIX represents a stark visualization of economic inequality in America.

The median household income in the United States is approximately

For a billionaire tech executive, a $50,000 Super Bowl ticket is a rounding error. It's less than what they earn in the time it takes to attend the game. The financial pain of Super Bowl attendance is zero. The opportunity cost is negligible.

This creates a weird dynamic where Super Bowl has become an exclusively elite experience. In past generations, it was possible for a middle-class family to save up and attend the Super Bowl as a special, once-in-a-lifetime event. That's no longer realistic. The price point has moved beyond the reach of all but the wealthiest Americans.

This isn't a moral judgment. It's an economic observation. Markets allocate goods to those who can afford them. If demand for Super Bowl tickets exceeds supply, prices rise. If only the wealthy can afford them, then only the wealthy will attend. This is how markets work.

But it's worth noting because it illustrates something broader about modern America: the ultra-wealthy and the rest of the country are experiencing increasingly different realities. They don't go to the same restaurants. They don't fly on the same airlines. They don't vacation at the same places. And now, they don't even attend the same Super Bowls.

There's also a legitimacy question here. If the Super Bowl becomes exclusively an event for the ultra-wealthy and their networks, does it retain the same cultural significance? Part of what makes the Super Bowl special is the sense that "everyone" is watching. But if "everyone" watching doesn't include the vast majority of Americans who can't afford tickets, does that change the nature of the event?

Sports have historically served as a great equalizer in American culture. A billionaire and a factory worker could both buy tickets and sit a few rows apart, united in their fandom. That's becoming impossible. The barrier to entry has become so high that it now separates people by economic class in a way that feels fundamentally at odds with sports' traditional role as a democratic pastime.

The AI Investment Landscape: Why Venky Ganesan and Menlo Ventures Matter

To fully understand the significance of Menlo Ventures' attendance at Super Bowl LIX, you need to understand the broader AI investment landscape in 2025.

Anthropic is not just another AI startup. It's a company founded by some of OpenAI's earliest and most talented researchers. Dario and Daniela Amodei, the company's founders, left OpenAI because they believed the company should prioritize AI safety research more heavily. They took a significant portion of OpenAI's best talent with them.

Four years later, Anthropic is on track to close a

Menlo Ventures recognized this opportunity early. The

This is significant because it reveals how the venture capital world actually works. It's not purely meritocratic. It's not even purely about which company has the best technology. It's about which company has the best relationships, the best ability to attract capital, and the best strategic positioning.

Anthropic has all three. The company has attracted talent from OpenAI, Google, and other leading AI labs. It's raised $20 billion in a single round, signaling extraordinary investor confidence. And it's positioned itself as the "responsible AI" company in a market where AI safety is becoming an increasingly important concern.

Venky Ganesan's attendance at Super Bowl LIX isn't just personal. It's professional. He's there to observe, listen, and gather intelligence about the AI market's future direction. He's there to strengthen relationships with other investors who might participate in future Anthropic rounds. He's there to understand how the competitive landscape is shifting and how Menlo should adjust its investment strategy accordingly.

This reveals something important about how power operates in Silicon Valley. You don't just make money by being smart. You make money by being in the right room at the right time with the right people. Super Bowl LIX is one of those moments.

A New Era of Corporate Theater: What Super Bowl LIX Signals About Tech's Future

Super Bowl LIX in Silicon Valley represents more than just a sporting event. It's a crystallization of several trends that will shape technology and society over the next decade.

First, it signals the increasing politicization of technology. When Google, OpenAI, Anthropic, Amazon, and Meta all run competing Super Bowl ads, they're not just competing on product features. They're competing on which company Americans trust more. They're competing on narrative and brand positioning. They're essentially asking, "Who do you want to shape the future of artificial intelligence?"

Second, it reveals the extreme wealth concentration in Silicon Valley and the tech industry more broadly. The fact that these companies are willing to spend

Third, it demonstrates the increasing importance of AI as a strategic priority. If we had been talking about Super Bowl LV in 2020, AI wouldn't have been a primary focus. Smartphones, cloud computing, and e-commerce would have been the topics. In 2025, AI dominates. Every major tech company is positioning around AI. Every competitive battle is being fought in the AI space.

Fourth, it shows how corporate competition increasingly plays out in cultural spaces. In previous decades, technology companies competed in tech publications, industry conferences, and specialized media. Now they compete during the Super Bowl, in mainstream culture, for the attention of everyday Americans.

Finally, it suggests that we're in a moment of genuine uncertainty about AI's future. If one company had decisively won the AI war, the others wouldn't be spending tens of millions on Super Bowl advertising. The fact that all of them are spending suggests that the market is genuinely undecided, and each company believes it still has a chance to win.

FAQ

What is the significance of holding Super Bowl LIX in Silicon Valley?

Super Bowl LIX in Silicon Valley represents the intersection of technology industry dominance and American popular culture. It's the third time the Bay Area has hosted the Super Bowl (1985 and 2015 being the previous occasions), and this year's game carries heightened significance because of the AI industry's prominence. The event serves as both a cultural moment for mainstream audiences and a strategic networking opportunity for tech executives, investors, and entrepreneurs who recognize the Super Bowl as a rare moment of concentrated attention and relationship-building opportunity.

Why do tech executives like Tim Cook and Neal Mohan attend Super Bowl games when they could watch on television?

Tech executives attend the Super Bowl for multiple strategic reasons beyond entertainment. First, it provides exclusive networking opportunities with other high-powered executives, investors, and business leaders in concentrated proximity. Second, it offers visibility and cultural credibility, signaling that tech companies are integrated into mainstream American culture, not just technical communities. Third, it allows executives to observe competitors' strategies in real-time through advertising placements and positioning. Finally, for Tim Cook specifically, Apple's sponsorship of the halftime show makes Super Bowl attendance a strategic brand reinforcement activity. For venture capitalists like Venky Ganesan, attendance provides intelligence-gathering opportunities crucial to investment decision-making.

How much do Super Bowl tickets actually cost, and who can afford them?

Average Super Bowl LIX ticket prices are approximately

What's the connection between venture capital firms like Menlo Ventures and Super Bowl attendance?

Venture capital firms like Menlo Ventures attend major cultural events like the Super Bowl to gather intelligence, strengthen relationships with other investors and entrepreneurs, and assess market sentiment around emerging technologies. Menlo's $100 million co-investment fund with Anthropic, combined with its participation in multiple Anthropic funding rounds, makes attendance strategically important. The Super Bowl provides a casual networking environment where Venky Ganesan can observe how the AI market is positioning itself competitively and strengthen relationships that might matter for future funding participation. In venture capital, information asymmetry and relationship depth often determine investment returns, making Super Bowl attendance a calculated business investment despite its high cost.

Why are tech companies spending tens of millions on Super Bowl advertisements about AI?

Tech companies are spending approximately $7-10 million per 30-second Super Bowl commercial to reach 115 million viewers in a single moment. This represents the only remaining opportunity in American media to achieve mass-market reach in an era of streaming fragmentation. For AI companies specifically, Super Bowl advertising serves the strategic purpose of reaching mainstream audiences (not just tech-savvy early adopters) and establishing trust and credibility around their AI products. Companies like Google, OpenAI, Anthropic, Amazon, and Meta understand that consumer perception of AI safety and trustworthiness will shape adoption rates and regulatory approaches. Super Bowl advertising allows them to control the narrative about AI development and position their specific company as the responsible, trustworthy choice in an emerging technology category where most consumers haven't yet formed strong opinions.

What does Super Bowl attendance reveal about economic inequality in America?

Super Bowl LIX starkly visualizes America's wealth concentration and economic inequality. The average ticket price of

How does Anthropic's 20 billion funding round impact the broader AI market competition?

Anthropic reaching a

What historical context do the previous Bay Area Super Bowls provide?

The Bay Area has hosted the Super Bowl twice previously: in 1985 at Stanford Stadium (when the 49ers defeated the Dolphins) and in 2015 at Levi's Stadium (when the Broncos beat the Panthers). Each Super Bowl reflected different phases of Silicon Valley's technological dominance. The 1985 Super Bowl occurred during the early personal computer boom when Apple was challenging IBM's mainframe dominance. The 2015 Super Bowl happened during peak tech confidence, with Google and Facebook approaching total market dominance. The 2025 Super Bowl occurs during an era of transition, where AI's transformative potential is recognized but not yet settled. The progression across these three events reveals Silicon Valley's evolution from rising technology hub to globally dominant power center to contemporary anxious wealth concentration.

Conclusion: Understanding Power in the Age of AI

Super Bowl LIX in Silicon Valley serves as a revealing window into how power, wealth, and technology intersect in contemporary America. The convergence of tech billionaires, venture capitalists, and mainstream audiences creates a moment where business and culture collide in illuminating ways.

Venky Ganesan's observation about "tech billionaires who got picked last in gym class paying $50,000 to pretend they're friends with the guys who got picked first" captures something true about the psychology of tech wealth. These are largely outsiders who've become insiders. They've inverted traditional hierarchies through technological innovation and built industries worth trillions of dollars. Now they're asserting their cultural power by participating in America's most iconic sporting event.

But the Super Bowl also reveals uncomfortable truths about 2025 America. Economic inequality has reached such extremes that the Super Bowl has transformed from a democratized cultural event into an exclusively ultra-wealthy privilege. The average citizen has been priced out entirely. Even upper-middle-class professionals find attendance impossible. Only the top 1% can participate.

Simultaneously, the Super Bowl serves as a strategic battleground for AI market dominance. When companies spend

The AI companies competing at Super Bowl LIX understand something crucial: in the early stages of transformative technologies, whoever controls the narrative often controls the market. IBM won with mainframes. Microsoft won with personal computers. Google won with search. Apple won with smartphones. Now, multiple companies are competing to win with AI. The outcome will reshape the global economy and determine trillions of dollars in value creation.

What happens at Super Bowl LIX—which companies advertise successfully, which executives show up, which relationships are strengthened in casual conversations between plays—will matter for the next decade of technology development. The game itself will be forgotten within weeks. But the networking, the competitive positioning, and the market intelligence gathered during Super Bowl weekend will influence AI investment decisions, strategic partnerships, and regulatory approaches for years to come.

That's why billionaires are willing to pay $50,000 to sit in a stadium. It's not really about football. It's about power, positioning, and the future of technology.

Run on, Super Bowl LIX. The real game is happening in the luxury boxes.

Key Takeaways

- Average Super Bowl tickets cost 50,000, making attendance an exclusively ultra-wealthy privilege

- Tech CEOs like Tim Cook and Neal Mohan use Super Bowl attendance for strategic networking and competitive intelligence gathering

- Tech companies are spending tens of millions on Super Bowl advertising to win the AI market narrative and consumer mindshare

- Menlo Ventures' $100 million co-investment fund with Anthropic reveals how venture capital orchestrates strategic positioning in emerging technology categories

- Super Bowl LIX represents a visible crystallization of tech industry wealth concentration and widening economic inequality in America

Related Articles

- Epstein's Silicon Valley Network: The EV Startup Connection [2025]

- Why Loyalty Is Dead in Silicon Valley's AI Wars [2025]

- How Elon Musk Is Rewriting Founder Power in 2025 [Strategy]

- Reddit's Acquisition Strategy for 2025: Why Adtech & AI Matter [2025]

- Tech Elites in the Epstein Files: What the Documents Reveal [2025]

- The 'March for Billionaires' Against California's Wealth Tax [2025]