The Bizarre Protest That Isn't Really a Joke

You'd think someone was pranking the internet when a website popped up advertising a "March for Billionaires" in San Francisco. The tagline alone makes it sound like performance art: "Vilifying billionaires is popular. Losing them is expensive."

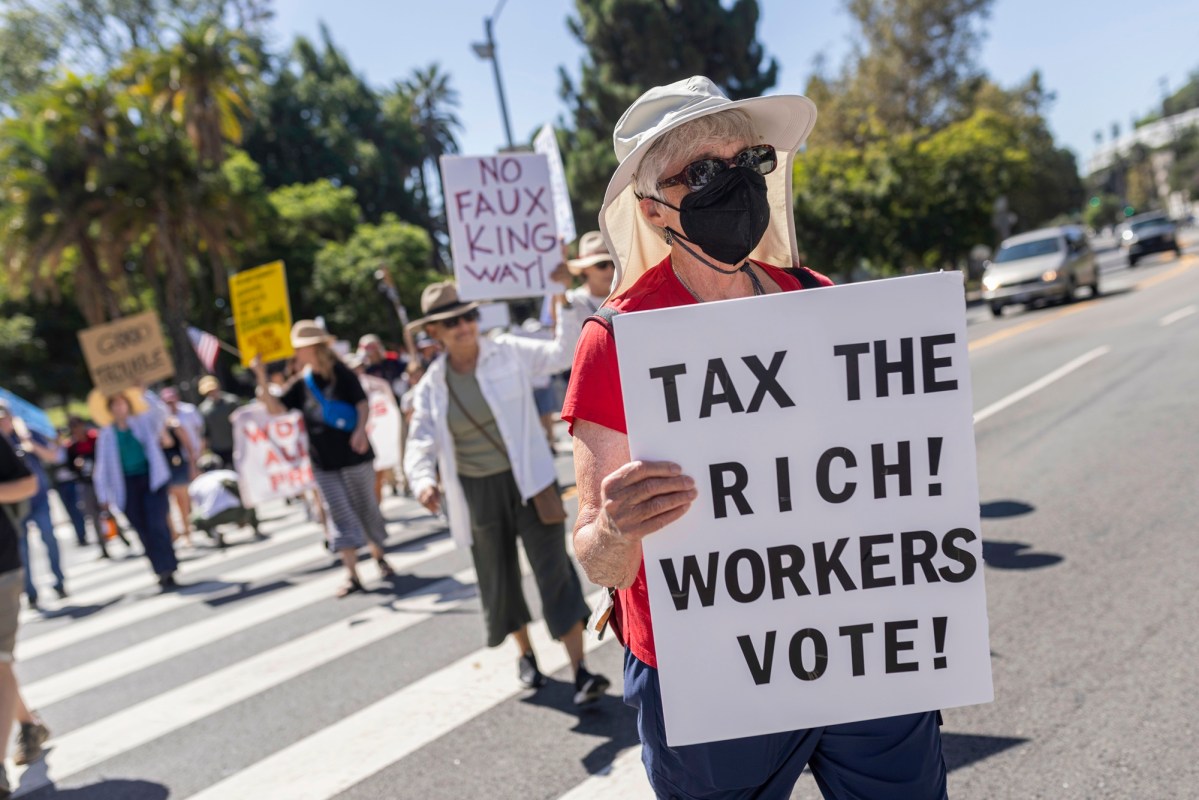

But here's the thing. It's real. And it's happening because California's proposed wealth tax has triggered something you rarely see from the startup world: organized, public, unapologetic resistance from tech founders.

Derik Kaufmann, founder of AI startup Run RL (which went through Y Combinator), decided to stop complaining online and actually organize a physical protest. When reporters from the San Francisco Examiner tracked him down, he confirmed it straight: the march is scheduled, it's not a hoax, and he's personally organizing it with no corporate backing.

What started as a private frustration among tech elites has escalated into something more visible, more contested, and frankly more awkward for everyone involved. Because here's the uncomfortable reality: Kaufmann told TechCrunch he doesn't actually expect any billionaires to show up. He figures maybe a few dozen people will attend.

So why organize it at all? And what does this tell us about the relationship between California's tech industry and state government in 2025?

The answers matter more than you'd think.

Understanding California's Billionaire Tax Proposal

Let's start with what everyone's actually fighting about: the Billionaire Tax Act.

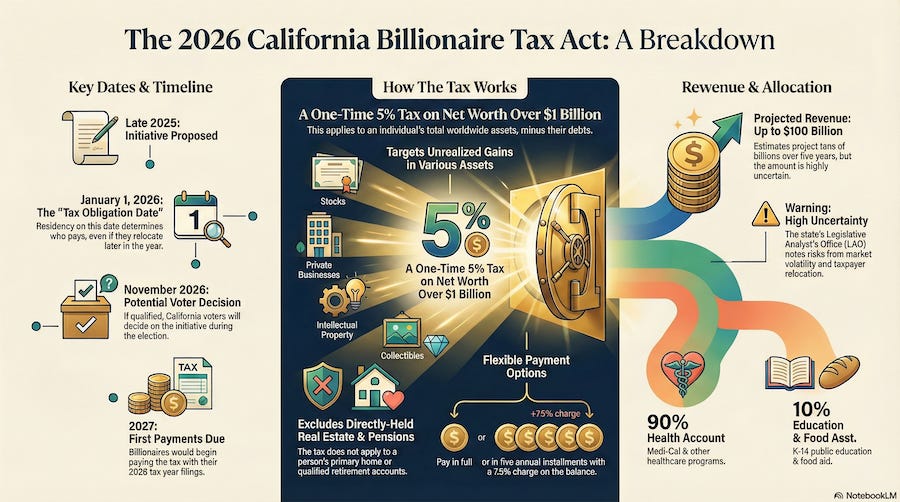

The proposal is straightforward in its mechanics but genuinely complex in its implications. It would impose a one-time 5% tax on the total wealth of any California resident worth over $1 billion. That's not income. That's total assets. Your house, your stock portfolio, your private company shares—all of it gets valued and taxed.

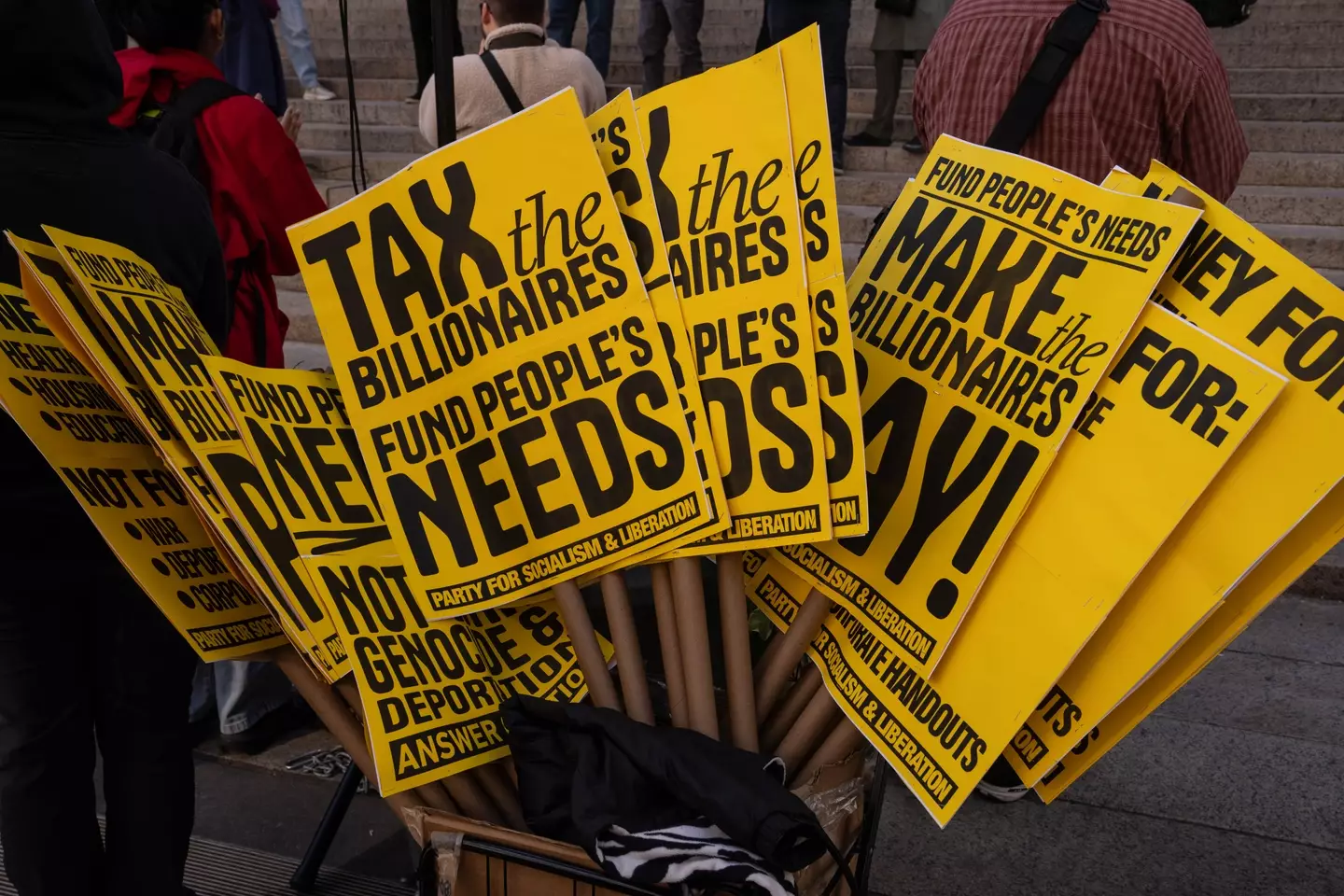

Support from major unions like SEIU (Service Employees International Union) frames it as a funding mechanism for public services and offsetting recent federal funding cuts. The argument is appealing at face value: billionaires have historically avoided meaningful taxation through legal structures and capital gains loopholes. A wealth tax hits them where traditional income taxes don't.

But implementation is where things get messy.

The first problem is valuation. How do you price a private company? Startup founders often have nearly all their wealth tied up in equity that hasn't been publicly valued. A founder holding 40% of a company you think is worth

The second problem is liquidity. A founder might be paper-rich but cash-poor. They'd need to sell stock or take loans to pay the tax. Selling equity in their own company means giving up control. Taking loans means incurring debt. Both scenarios are actually terrible for running a startup.

Kaufmann made this specific argument in his conversation with TechCrunch: "It hits startup founders whose wealth is only on paper. They would be forced to liquidate shares on potentially unfavorable terms, incurring capital gains taxes and giving up control."

He also cited an interesting historical precedent. Sweden implemented a comprehensive wealth tax in 1947. They abandoned it in 2007 after it became clear the wealthy were simply leaving. When they did, capital fled the country. Today, Sweden has 50% more billionaires per capita than the United States—partly because they reformed their tax code to be competitive.

That's the real fear driving the tech resistance: not that billionaires will be slightly poorer, but that they'll move.

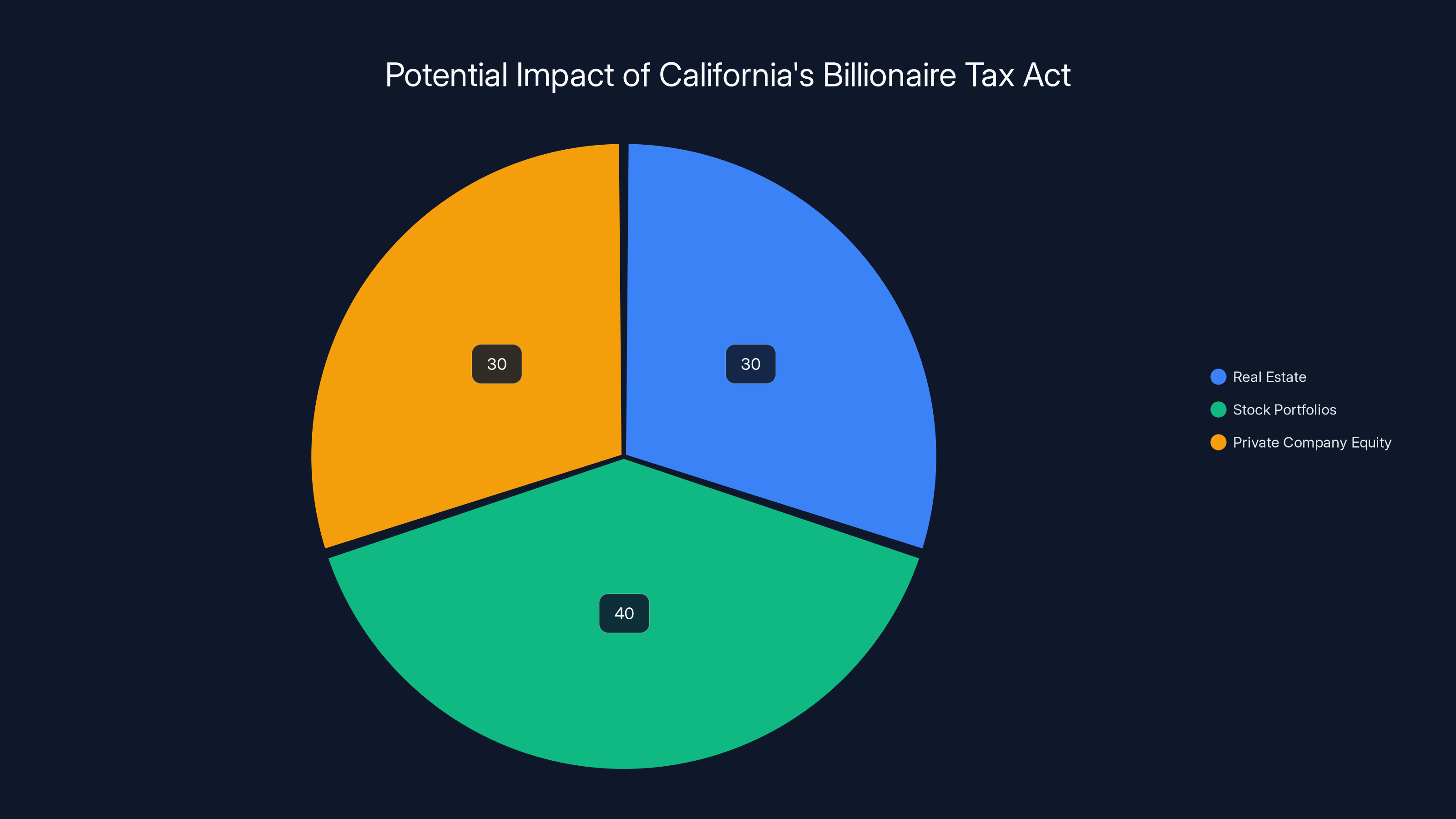

Estimated data shows the Billionaire Tax Act would equally impact real estate and private company equity, with stock portfolios slightly more affected.

Why Tech Leaders Are Actually Terrified

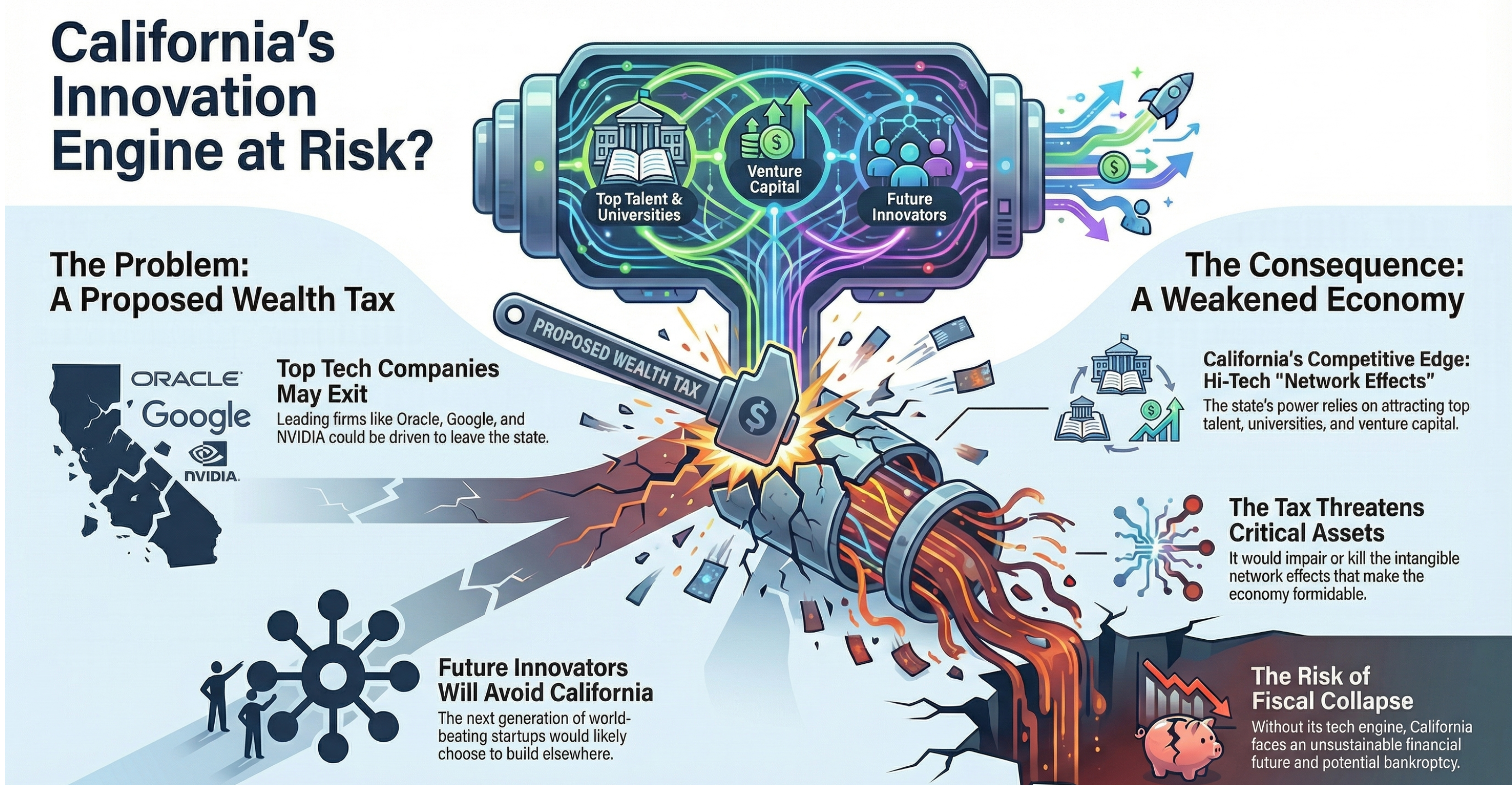

This isn't about billionaires defending their yachts. It's about how California's tax policy affects the entire startup ecosystem.

Here's the cascading logic that keeps founder circles up at night:

If the wealthiest 1% of residents face a 5% wealth tax, some will leave. History suggests this is a rational response—not just vindictiveness, but straightforward financial incentive. A founder worth

When wealthy people leave, they take their capital and influence with them. That matters for startups because successful founders become angel investors, board members, and mentors for the next wave. The network effects that made Silicon Valley possible start degrading.

Second-order effect: reduced tax revenue contradicts the whole premise of why the tax was proposed. You can't fund public services with a tax that causes capital flight. Both Sweden's experience and more recent analyses suggest this was a real problem.

Third-order effect: the brain drain. Senior engineers follow founders. Successful startups relocate headquarters. The region's advantage compounds.

Kaufmann's concern wasn't abstract theoretical economics. He was protecting the ecosystem that enabled his own company to exist.

Estimated data shows that stock portfolios and private company shares would contribute significantly to the tax revenue. Real estate also plays a crucial role.

The Weird Politics of Protesting in Your Own Interests

Here's where this gets genuinely awkward for everyone involved.

America's cultural narrative around billionaires is pretty negative right now. Extreme wealth concentration, regulatory capture, tax avoidance—these are real concerns that resonate across political demographics. So when Kaufmann organized the "March for Billionaires," the immediate reaction online was ridicule.

One social media user captured the instant skepticism: "I can't imagine billionaires marching in the street."

But that's exactly why Kaufmann had to be so explicit about what he was doing. He couldn't position this as "protecting startups" or "preserving California's tech economy." Those frames also generate pushback from people who think California's wealth concentration is itself the problem.

So he named it literally: March for Billionaires. Own the framing. Don't hide behind euphemisms.

Was it effective? That depends on your metric. The march got media attention. Kaufmann got quoted by TechCrunch, the San Francisco Examiner, and probably other outlets. That's amplification. But amplifying an unpopular position is a two-way street.

The underlying political reality: Governor Gavin Newsom has already stated he'd veto the bill if it passed the legislature. So the tax almost certainly won't become law. Kaufmann is protesting a bill that's functionally dead.

Which raises another question entirely: what's the actual purpose of the march?

Why Organize a Protest That Probably Won't Matter

If the governor will veto it anyway, why spend the effort?

A few possibilities:

Signal to the legislature. Even if Newsom vetoes, showing organized opposition might discourage legislators from wasting political capital on a doomed bill. Public protests create media narratives. Those narratives influence how lawmakers think about costs and benefits.

Establish a pattern. This is the first such proposal. If it's defeated decisively, similar proposals in future years face higher thresholds. Kaufmann and others are trying to make sure California's political class knows that tech industry mobilization around tax policy is now normal.

Pressure from below. Not every legislative proposal that will be vetoed deserves executive veto. Some require public pressure to kill in the legislature itself. By organizing a march, Kaufmann might be trying to shift the legislative calculus.

Founding narrative. Let's be honest: organizing a protest—especially one this provocative—is memorable. Kaufmann gets founder credibility for taking a stand. That's useful if you're trying to raise a Series A or build a certain public reputation.

None of these are wrong motivations. But they're useful to keep in mind when evaluating whether the march is what it claims to be.

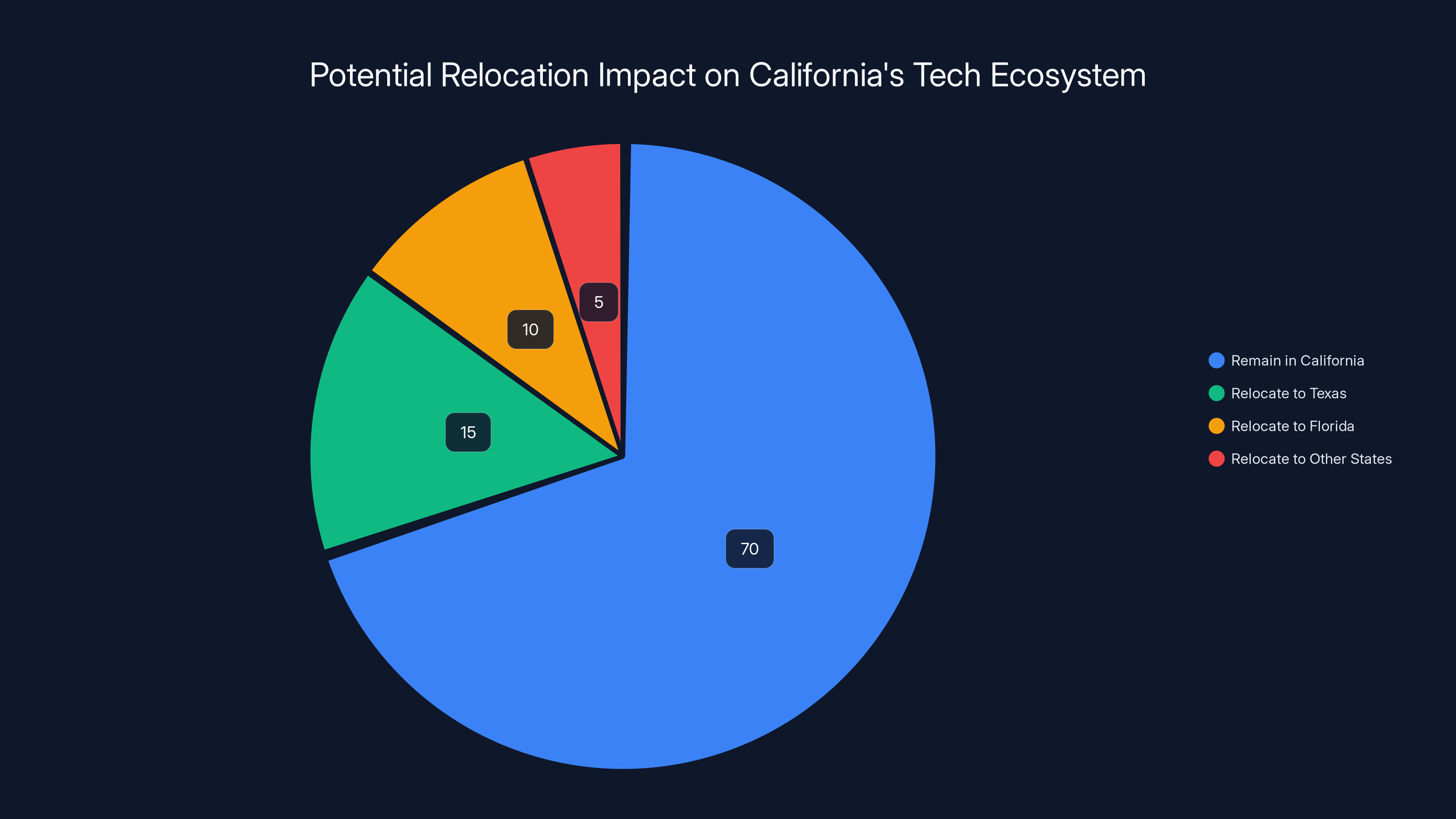

Estimated data suggests that if 20% of tech founders relocate, California's tech ecosystem could significantly change, with Texas and Florida being popular destinations.

The Historical Context: Wealth Taxes That Failed

Kaufmann wasn't inventing the Sweden reference. It's a real policy test case that economists across the ideological spectrum reference.

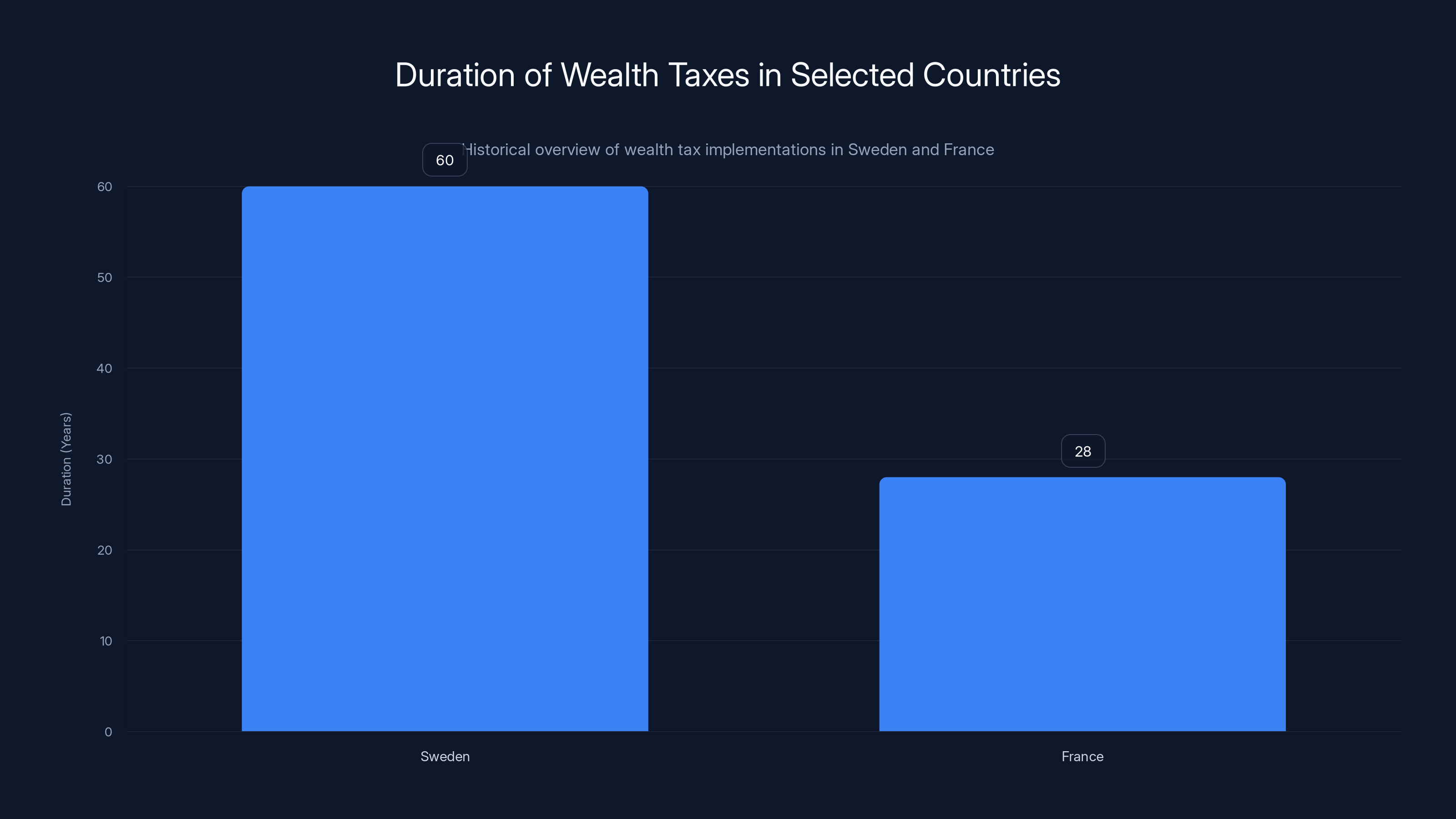

Sweden's wealth tax lasted 60 years (1947-2007). During that time, capital flight became progressively worse. Assets that couldn't leave (real estate) stayed. Assets that could (stocks, bonds, business ownership) relocated. By the early 2000s, the tax was estimated to be raising negative revenue when you factored in capital flight costs.

Other countries tried it too. France had a wealth tax from 1989 to 2017. It was repealed after economic analysis showed that wealthy residents were leaving faster than the tax was generating revenue. The wealth tax literally made France poorer in absolute terms, not just for billionaires.

There are maybe 3-4 countries worldwide that successfully maintain wealth taxes. Most of them are small, geographically contained nations where capital flight is harder. None of them are tech hubs competing for global talent and capital.

So Kaufmann's historical references weren't cherry-picked. They're the actual precedent. And that precedent suggests: comprehensive wealth taxes on paper assets tend to fail spectacularly because they trigger capital flight.

California's specific proposal might address some of the valuation issues that sank other wealth taxes. But it doesn't solve the fundamental problem: if you make it expensive to be a billionaire in California, billionaires will leave.

That's not an opinion. That's historical pattern.

The Tech Industry's Larger Exodus Threat

We're not just talking about this one tax proposal. We're talking about a years-long pattern of tech leadership threatening to leave or actually leaving California.

Elon Musk relocated Tesla and Space X operations out of California. Numerous founders have claimed they're moving to Texas, Florida, or other lower-tax jurisdictions. The narrative has become standard: California is becoming unaffordable, overtaxed, and hostile to business.

Now, that narrative isn't entirely true. California still dominates in venture funding, still has the densest cluster of talented engineers, still produces the most unicorn startups. But perception shapes reality in capital allocation.

If even 10% of influential founders genuinely relocate, the network effects degrade. If 20% leave, it becomes a different ecosystem entirely.

So the Billionaire Tax isn't isolated political theater. It's one more pressure point in a longer argument about whether California remains the default home for ambitious tech founders or becomes just one hub among several.

That's why Kaufmann organized the march. Not because $100 million in taxes is personally devastating. But because he's thinking about what the ecosystem looks like if the costs of being in California keep rising and the tax burden keeps increasing.

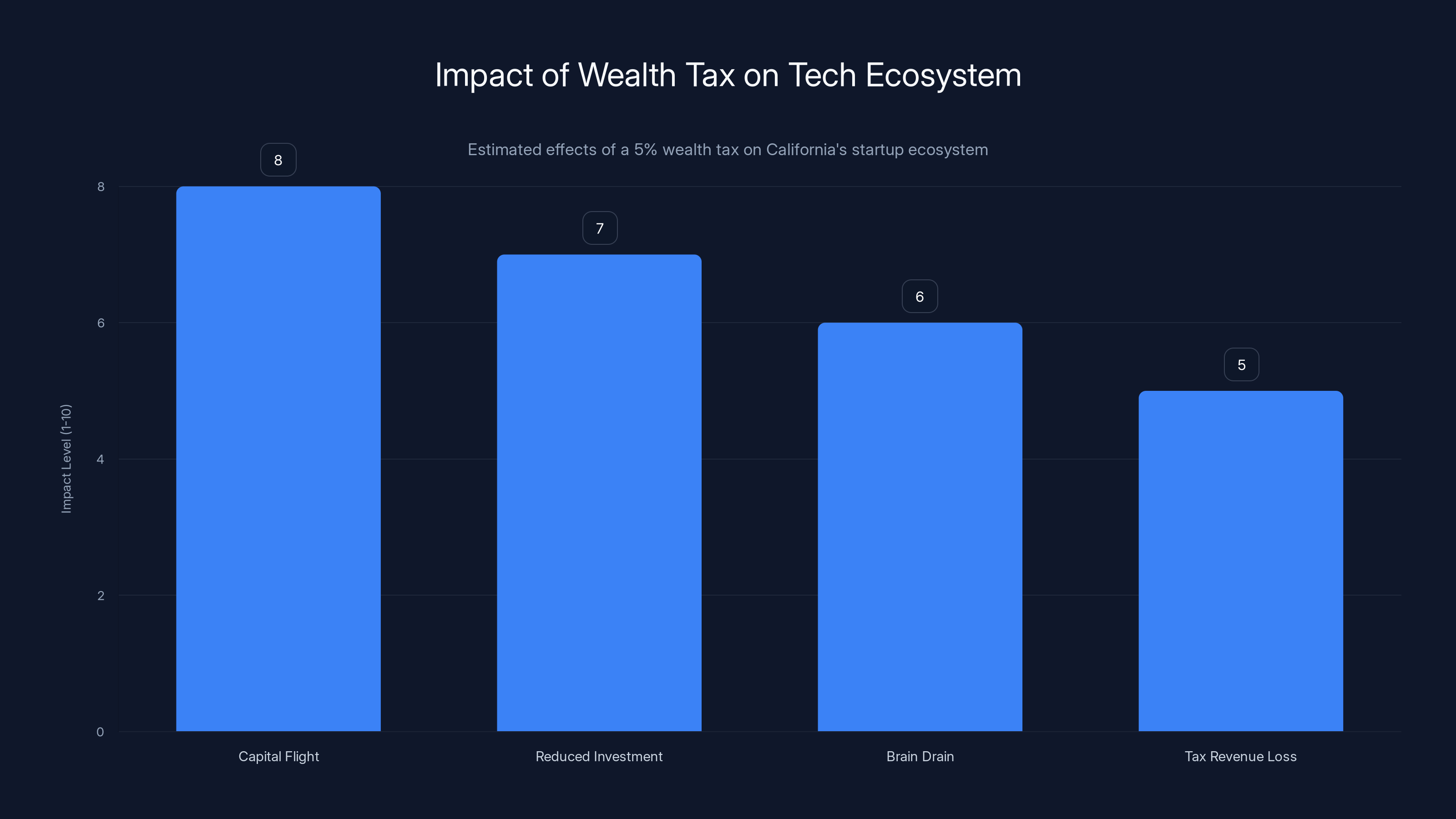

A 5% wealth tax could significantly impact California's startup ecosystem by causing capital flight, reducing investment, and leading to brain drain. (Estimated data)

The Logistics of a Protest Nobody Expects

Here's the funny part of this whole situation: Kaufmann was honest about what to expect.

He told TechCrunch he expected "a few dozen attendees." Maybe fewer. Probably not any actual billionaires (his words).

So the march, if it happened, would be hundreds of people at most. Possibly fewer. In a city of 815,000 people, that's invisible noise.

But scale isn't the point. Media attention is. If 50 people show up and it gets covered by TechCrunch, the Examiner, and local news, the march has amplified its message far beyond attendee count.

That's modern protest strategy. You don't need 100,000 people to influence the narrative if you're targeting the right audience (venture capitalists, tech founders, journalists who cover startups) and doing something unprecedented enough to be newsworthy.

A march for billionaires by a 20-something founder is inherently newsworthy because it's weird and it's honest about its intentions. That honesty—refusing to disguise wealth-protection advocacy as something more noble—is what makes it media-effective.

Deeper Issues: The Startup Valuation Problem

Kaufmann's core argument about valuation and liquidity deserves more serious analysis than it usually gets.

When a startup founder's net worth is calculated, most of their value is in restricted stock with no liquid market. There's no traded price. No daily valuation. Just estimates.

If the IRS needs to value a private company for inheritance tax purposes, they use comparables: what did similar companies sell for? But those comps are imperfect, especially for pre-revenue startups or companies in novel categories.

Now imagine a wealth tax that needs annual revaluations. A startup founder's "wealth" could swing 30-50% year to year based on fundraising, major customer wins, or failed pivots. Would the tax burden adjust retroactively? Would there be appeals processes? Would founders need to hire valuation specialists annually?

The administrative complexity is genuinely non-trivial. And the more complex it becomes, the more it favors wealthy people who can afford sophisticated accounting and legal help. Which kind of defeats the progressive purpose of the tax.

Kaufmann raised this concern explicitly: "Additionally, there's no precedent for this sort of comprehensive wealth tax in the US."

He's right. The U.S. has never successfully implemented a national wealth tax. Most states that tried—like Ohio and Indiana with net worth taxes—abandoned them after they generated minimal revenue.

Sweden and France implemented wealth taxes for 60 and 28 years respectively, but both faced significant capital flight issues leading to their repeal.

The Veto Guarantee That Changes Everything

Here's the key detail that most coverage doesn't emphasize enough: Governor Newsom has already said he'll veto the bill if it passes.

That's not a maybe. That's not a strong signal. That's a commitment.

So technically, the entire battle is already decided. The bill can pass the legislature unanimously and it still dies. Newsom has essentially told his party: don't bother.

Given that, what does the "March for Billionaires" actually accomplish?

It hardens positions. It makes it harder for moderate legislators who might have voted yes under different circumstances to do so now, because they don't want to be associated with billionaire-friendly activism. It establishes that there is organized opposition, which changes the calculus for future proposals.

But it also invites mockery. It makes the tech industry look like it's whining. And it centers billionaires in a conversation that many people think should be about inequality and public services.

From a pure strategic standpoint, if you're opposing this tax, you probably don't want your most visible supporter to be someone literally organizing a march with "billionaires" in the name.

The Broader Context: Tech vs. State Government

This specific tax proposal sits within a much larger story about the relationship between California's tech industry and state government.

For decades, that relationship was symbiotic. Tech created jobs and tax revenue. California reinvested in education, infrastructure, and research. The Valley's success depended on public universities (Stanford, Berkeley, Caltech) producing engineers. State investments in early-stage research supported venture capital returns.

But that relationship has degraded. Tech companies feel over-taxed. California feels like tech's growth has driven up housing costs, created inequality, and left public services underfunded. Both sides have legitimate grievances.

The Billionaire Tax is one expression of that tension. It says: tech has benefited from California. Now California needs money. Contribute.

The opposing view says: tech's taxation and regulation is already burdensome. Making it worse drives innovation and capital elsewhere.

Neither side is entirely wrong. And Kaufmann's march is just the visible expression of a much deeper structural problem.

How Other Founders Are Responding

Kaufmann is not alone in opposing the tax. But he's unusual in being so public and so literal about it.

Most tech leaders are working through lobbying channels. The California Chamber of Commerce, various industry associations, and venture capital groups are all running sophisticated campaigns against the bill.

Those campaigns involve research reports, testimony before legislative committees, private meetings with lawmakers, and media strategy. They're well-funded and professional.

Kaufmann's march is the opposite: grassroots, visible, honest about its intentions, and potentially embarrassing to the broader tech industry.

Some founders probably appreciate it. Others probably wish he'd let the professional lobbyists handle it. Organizing a march that admits it won't have many attendees is a weird flex.

But that weirdness might actually be the point. In a saturated media environment where everyone is trying to spin narratives, blunt honesty can be more effective than polished PR.

The Role of Media and Narrative

The March for Billionaires wouldn't exist as a story without media coverage. TechCrunch, the Examiner, and presumably other outlets gave it attention.

Why? Because it's weird. Because it's topical (wealth tax debate is active). Because Kaufmann is honest rather than defensive about what he's doing.

That media attention amplifies the message far beyond what a few-dozen-person march could accomplish alone. Thousands of people learn about the core argument (wealth taxes cause capital flight, valuation is hard, founders get squeezed) because reporters thought the story was interesting enough to cover.

So the march functions as a media event first, an actual public gathering second.

That's how modern activism works. The most effective protests are the ones that create narratives interesting enough to spread.

Looking Forward: What Happens Next

The march was scheduled to occur after the initial reporting. Whether it actually happened, what attendance looked like, and what coverage it generated—that data would tell us a lot about how effective Kaufmann's gamble was.

But we can predict some outcomes:

Short-term: The Billionaire Tax either dies quietly in committee or passes and gets vetoed by Newsom. Either way, it doesn't become law.

Medium-term: California's relationship with tech continues to be strained. More rhetoric about wealth inequality. More rumors of founder exodus. More lobbying battles.

Long-term: The underlying problem remains unsolved. California needs revenue. Tech claims over-taxation limits growth. Some founders and companies will leave. The state's competitiveness for tech talent and capital will gradually diminish, or California will find ways to remain attractive despite higher taxes.

Kaufmann's march is just one data point in that longer trajectory. It might matter more than expected because it normalizes public tech industry activism around tax policy. Or it might become a footnote—a weird protest that happened in 2025 when California had a wealth tax proposal.

The Startup Founder Perspective

There's something important to understand about why a 20-something founder would organize a protest against a tax he himself might not even be subject to (depending on Run RL's valuation).

It's not primarily self-interest. It's ecosystem thinking. Founders understand that their success depends on the infrastructure around them. Remove that infrastructure—make it expensive to operate, make talent leave, make capital relocate—and your own startup becomes harder.

So when Kaufmann organized the march, he wasn't just defending billionaires. He was defending the ecosystem that enabled his startup to exist.

That's not a selfish motivation. It's actually a reasonable way to think about policy. Ask yourself: how does this policy affect the system I depend on?

In this case, the answer from the tech industry was: it affects it badly. Enough to organize a visible protest, even if that protest is awkward and probably won't change the outcome.

Conclusion: The March That Probably Won't Change Anything But Might Change Everything

Derik Kaufmann organized a "March for Billionaires" in protest of California's proposed Billionaire Tax Act. He'll probably get a few dozen attendees. He definitely won't get any actual billionaires. Governor Newsom will almost certainly veto the bill anyway. So in purely transactional terms, the march accomplishes nothing.

But that frames it too narrowly.

What the march actually does is make tech industry opposition to wealth-focused taxation visible, explicit, and impossible to ignore. It shifts the narrative slightly. It establishes that this is something worth organizing around. It creates media coverage and plants ideas in people's heads about whether comprehensive wealth taxes actually work.

Those might be small effects. But in politics and culture, small narrative shifts compound.

More fundamentally, the march represents a moment when California's tech industry—or at least portions of it—decided that remaining quiet about tax policy was no longer acceptable. Previous generations of tech founders and investors tried to avoid political visibility. This generation is more willing to risk ridicule to advocate for policies they believe in.

Whether that's healthy civic participation or whether it's a billionaire class consolidating political power is a question everyone has to answer for themselves.

But the fact that we're asking it is itself interesting. A 20-something founder organizing a march for billionaires was impossible five years ago. Now it's just a weird Tuesday in San Francisco.

That tells you something about how much the politics of tech have shifted.

FAQ

What is California's Billionaire Tax Act?

The Billionaire Tax Act is a proposed one-time 5% tax on the total wealth of California residents worth over $1 billion. It would apply to assets including real estate, stock portfolios, and private company equity. The legislation is backed by unions like SEIU and is intended to fund public services and offset federal funding cuts.

Why did Derik Kaufmann organize the March for Billionaires?

Kaufmann organized the march to publicly oppose the Billionaire Tax Act, which he believes would harm the startup ecosystem. He argues the tax would force founders to liquidate shares at unfavorable terms, incur capital gains taxes, and lose control of their companies. He also cited Sweden's experience, where a wealth tax led to capital flight and was abandoned after 60 years.

Would the tax actually affect startup founders differently than other wealthy people?

Yes. Startup founders often have nearly all their wealth in restricted private company equity with no public market valuation. The tax would require annual valuations of private companies—which is administratively complex and subject to disputes. Founders would face significant pressure to sell equity to pay taxes, potentially losing control of their companies in the process.

Has Governor Newsom said he'll support or veto the bill?

Governor Newsom has already stated that he would veto the bill if it passes the legislature. This makes the bill's passage highly unlikely, even if it clears the legislative process. His veto position was declared before the bill was formally considered.

What's the historical precedent for comprehensive wealth taxes?

Sweden implemented a comprehensive wealth tax in 1947 and abandoned it in 2007 after it became clear wealthy residents were leaving the state. Similar taxes in France, Ohio, and Indiana also failed due to capital flight and minimal revenue generation. The United States has never successfully implemented a national wealth tax.

Who actually planned to attend the March for Billionaires?

Kaufmann told TechCrunch he expected "a few dozen attendees" and that he wasn't aware of any actual billionaires planning to attend. The march was more about generating media attention and making public the tech industry's opposition to the tax than about creating a massive physical gathering.

Key Takeaways

- Derik Kaufmann, Y Combinator founder of RunRL, organized a real March for Billionaires against California's proposed 5% wealth tax on residents worth over $1 billion

- The tax would force startup founders to liquidate restricted equity at unfavorable terms, incurring capital gains taxes and losing company control

- Governor Newsom has already stated he would veto the bill, making the march's actual policy impact minimal but its narrative significance substantial

- Historical precedent from Sweden, France, and other countries shows comprehensive wealth taxes trigger capital flight and generate minimal revenue

- The march represents growing willingness of tech founders to engage in public, visible activism around tax policy—a shift from previous generations' quieter lobbying

Related Articles

- Why Loyalty Is Dead in Silicon Valley's AI Wars [2025]

- Epstein's Silicon Valley Network: The EV Startup Connection [2025]

- How Elon Musk Is Rewriting Founder Power in 2025 [Strategy]

- Reddit's Acquisition Strategy for 2025: Why Adtech & AI Matter [2025]

- EU's TikTok 'Addictive Design' Case: What It Means for Social Media [2025]

- The ARR Myth: Why Founders Need to Stop Chasing Unrealistic Growth Numbers [2025]

![The 'March for Billionaires' Against California's Wealth Tax [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/the-march-for-billionaires-against-california-s-wealth-tax-2/image-1-1770428131568.jpg)