Introduction: When Wealth, Power, and Technology Collide

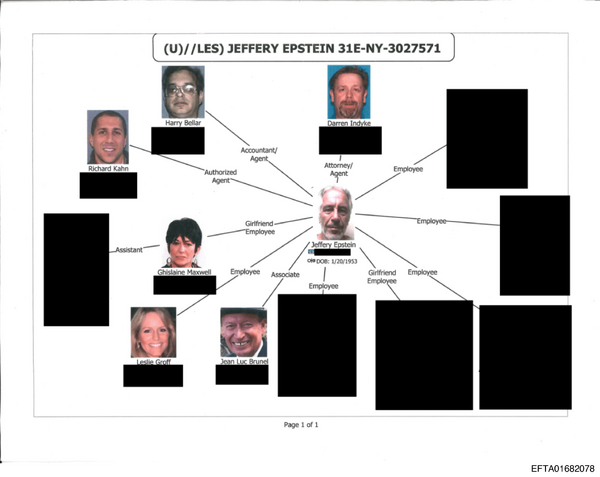

The tech industry has always operated on a simple premise: money finds opportunity. But what happens when that money comes from sources we later discover are deeply troubling? Last week, the Department of Justice released 3 million documents related to Jeffrey Epstein, and buried within thousands of pages of correspondence were emails revealing something the industry rarely discusses openly: how closely Epstein was connected to Silicon Valley's most ambitious ventures.

This isn't just another story about a wealthy financier backing startups. It's about how the electric vehicle boom of the 2010s attracted capital from everywhere—including sources that should have been scrutinized far more carefully. The documents show a mysterious businessman named David Stern pitching Epstein on investing in some of the most prominent EV startups of that era: Lucid Motors, Faraday Future, and Canoo.

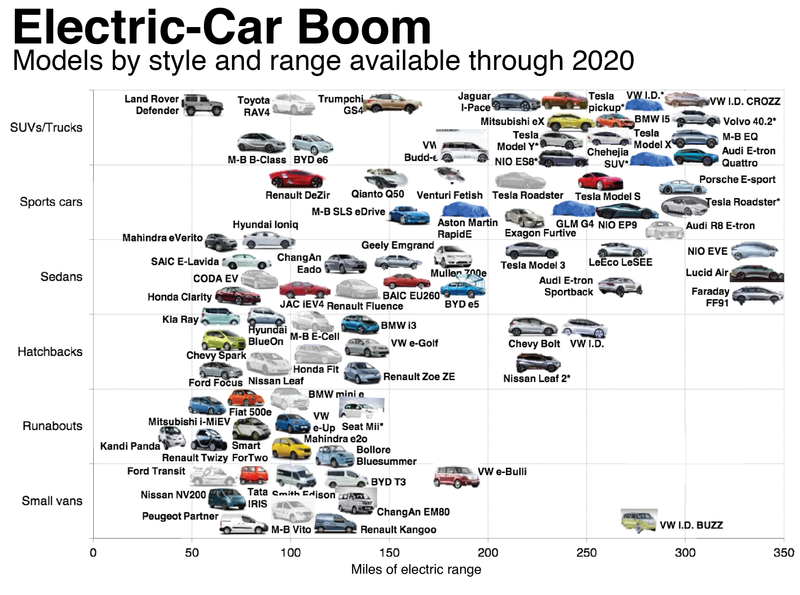

At the time, the stakes felt enormous. Electric vehicles were poised to reshape transportation. Tesla had proven the market existed. Google was developing self-driving cars. Legacy automakers were panicking. And startups were raising hundreds of millions of dollars to chase what many believed would be the next trillion-dollar industry.

But here's what's striking about these newly released documents: they reveal not just a financial relationship, but a window into how wealth and influence operate in the startup ecosystem. Stern had positioned himself as a connector—someone with access to Chinese capital, relationships with Prince Andrew, and seemingly everyone who mattered in the mobility space. Epstein was a check-writer with a hunger for deals and intelligence.

The documents paint a portrait of a relationship that lasted nearly a decade, starting in 2008 and continuing right up until Epstein's arrest in 2019. It's a relationship that exposes uncomfortable truths about due diligence, about how little we actually know about who funds startups, and about the ways that financial networks operate largely outside public view.

This article digs into what the newly released files tell us. It explores David Stern's background and how he became a connector between Silicon Valley and Epstein. It details the specific startup pitches, the failed deals, and what ultimately happened to the companies involved. And it asks harder questions about what this episode teaches us about startup funding, regulatory oversight, and the importance of knowing where capital actually comes from.

TL; DR

- David Stern, advisor to Prince Andrew, pitched Epstein on EV startups during the 2010s mobility boom, including Lucid Motors, Faraday Future, and Canoo

- The relationship lasted nearly a decade, with Epstein describing Stern as his "china contact" and Stern calling Epstein his "mentor"

- Lucid ultimately raised over $1 billion from Saudi Arabia's PIF in late 2018, not from Epstein; Faraday received investment from Chinese real estate firm Evergrande

- These disclosures reveal how little was known about Epstein's actual connections to high-profile tech ventures during his active years before arrest in 2019

- The documents expose gaps in startup due diligence regarding investor backgrounds and financial source verification

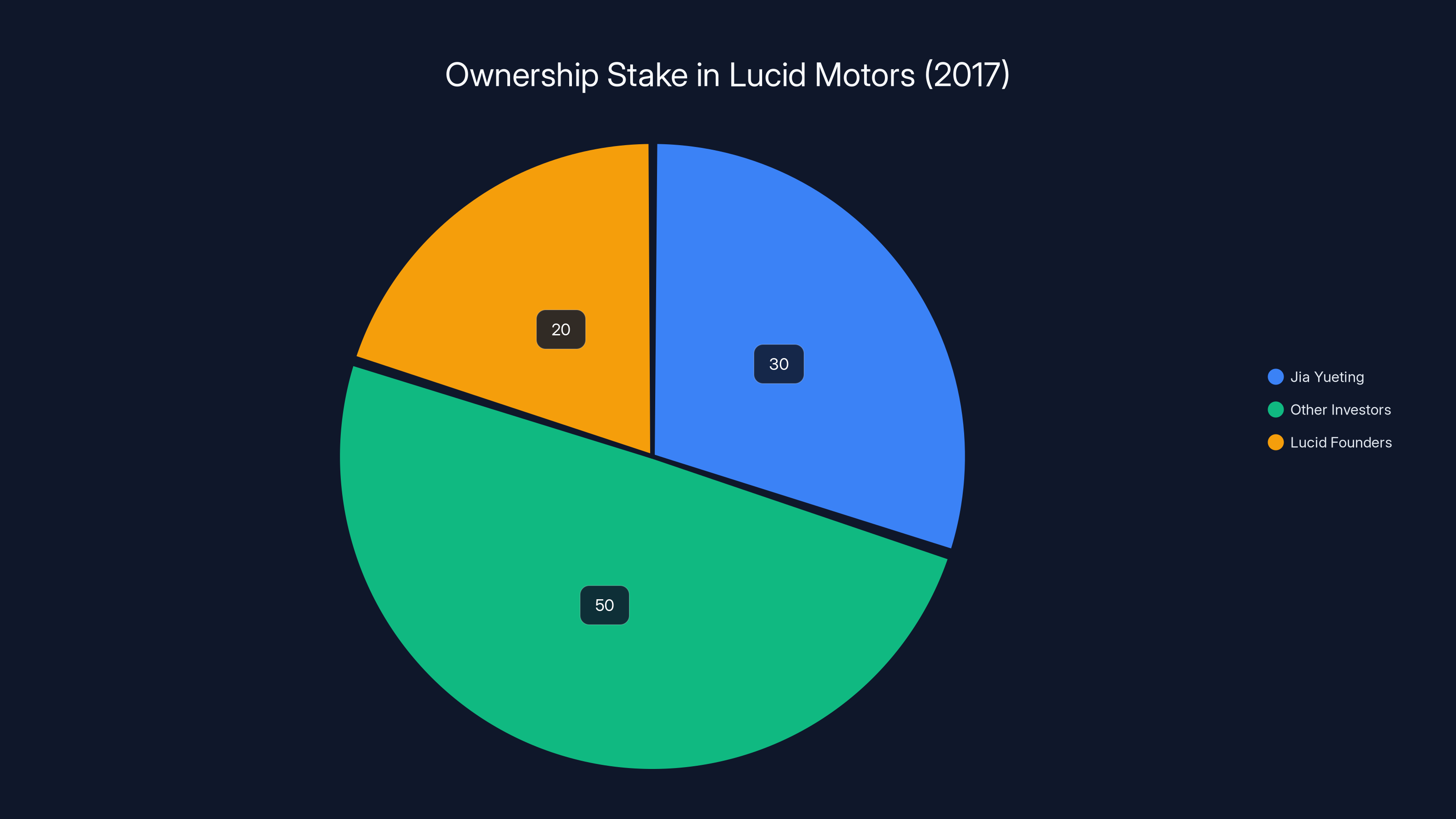

In 2017, Jia Yueting held a significant 30% stake in Lucid Motors, creating a blocking position that complicated new investment rounds. Estimated data.

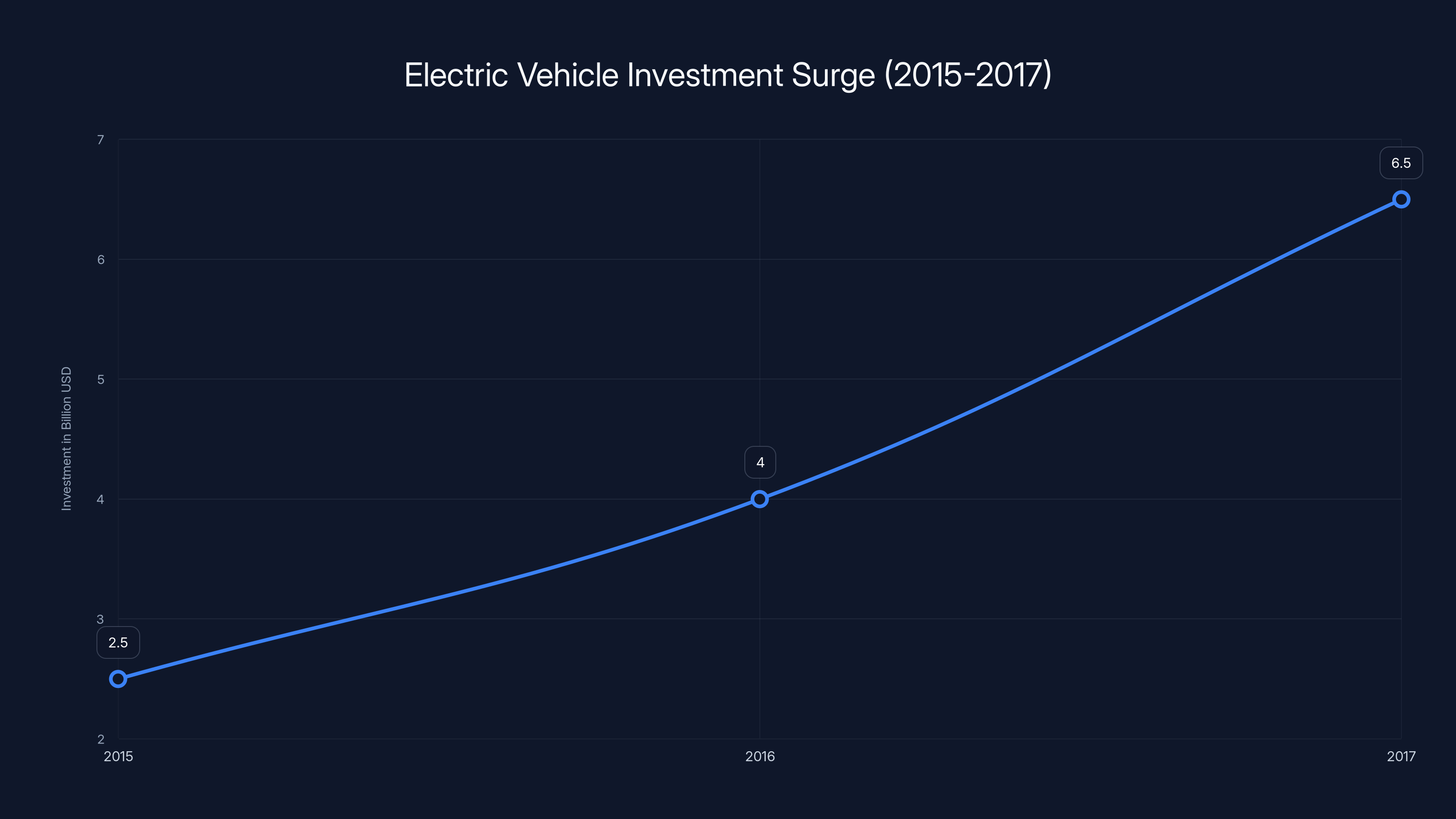

The Electric Vehicle Gold Rush of 2015-2017

To understand why Stern was pitching EV startups to Epstein, you need to understand the fever that gripped Silicon Valley in the mid-2010s. Electric vehicles had transitioned from curiosity to inevitability in the minds of most tech investors and entrepreneurs.

Tesla had done something previously thought impossible: build a luxury car that was also electric, make it desirable, and actually turn a profit on it. The Model S, launched in 2012, wasn't just a technical achievement. It was a statement that electric vehicles could be better than their gas-powered alternatives, not just environmentally superior but genuinely more fun to drive.

Google's self-driving car project was advancing rapidly. Reports of autonomous vehicles successfully navigating city streets sparked a new wave of imagination. If cars could drive themselves, what else might be possible? The convergence of electrification and automation suddenly seemed like it could reshape not just transportation but entire cities.

Traditional automakers were terrified. They'd spent decades building expertise in internal combustion engines. Their supply chains, manufacturing processes, and organizational structures were all optimized for a technology they now had to abandon. Meanwhile, a startup with fewer than 10,000 employees was eating their lunch.

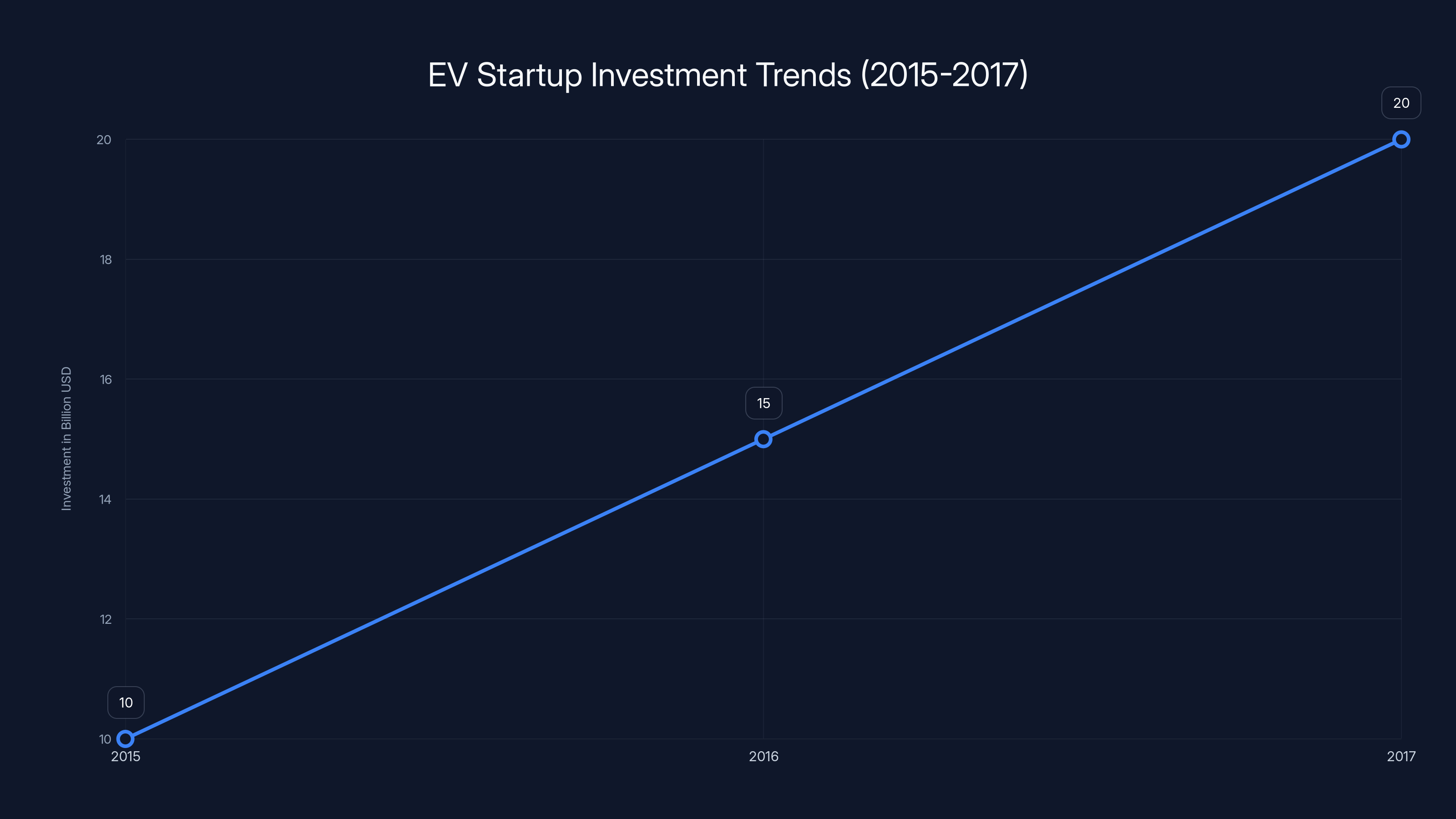

This created what venture capitalists call "white-hot" sector dynamics. When the market believes something is inevitable, capital flows like water. Venture firms were raising multi-billion dollar funds dedicated exclusively to mobility. Entrepreneurs were pitching not just cars but entire ecosystems: charging networks, autonomous systems, new manufacturing techniques.

Lucid Motors epitomized this moment. The company was founded in 2007 by engineers who'd previously worked at Tesla and BMW. By 2017, the company had built stunning concept cars and was preparing to launch its first production vehicle, the Lucid Air. It was pure technological ambition: a sedan that would outperform everything on the market, with revolutionary battery technology and stunning design.

Faraday Future was another high-profile player. Founded in 2014 by Jia Yueting, who'd built a media and real estate empire in China, Faraday had raised over $1 billion and was building a massive manufacturing facility in Nevada. The company was promising electric vehicles that would leapfrog Tesla's technology.

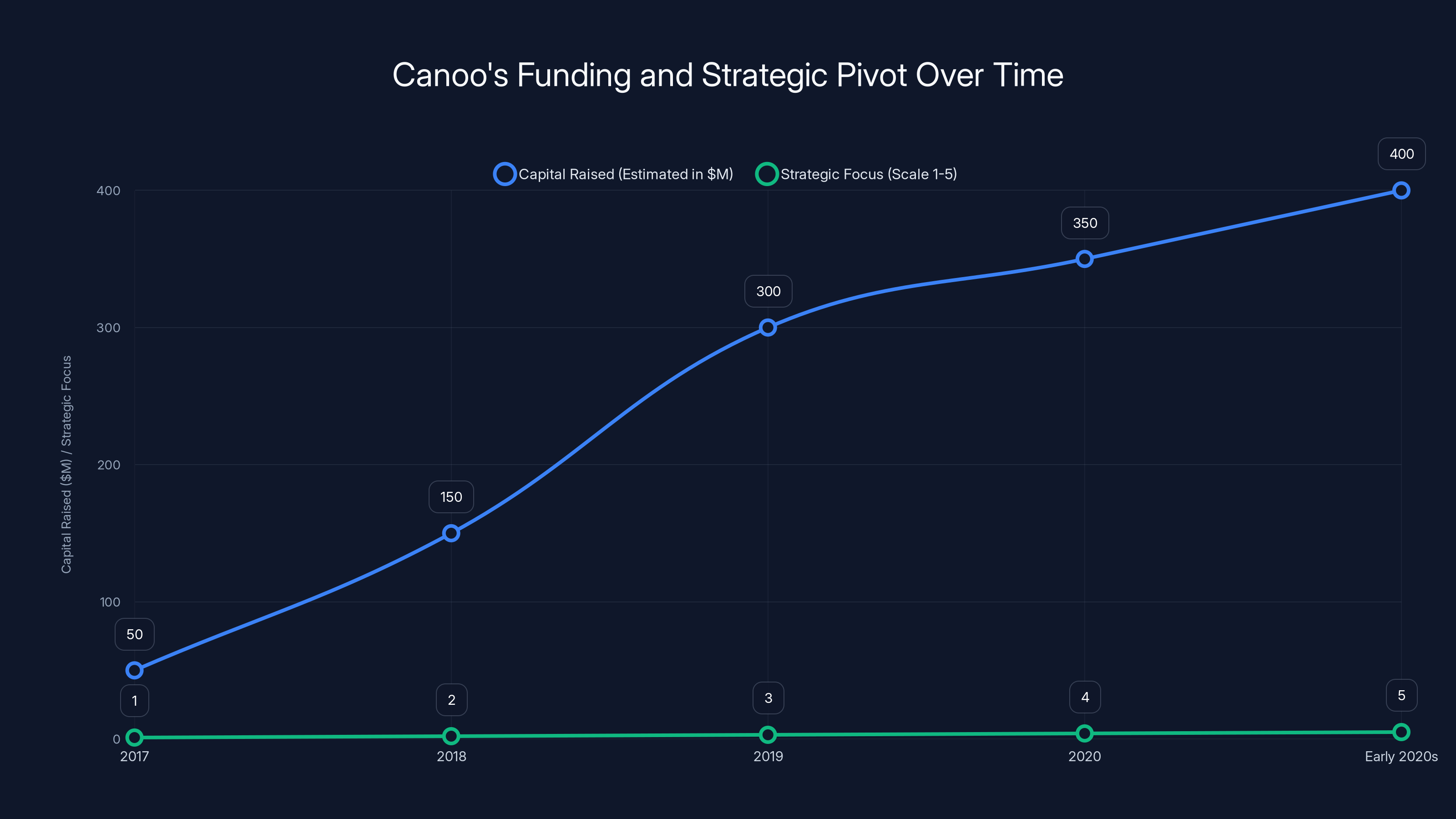

Canoo, founded in 2017, was taking a different approach. Instead of trying to beat Tesla at its own game, Canoo was focused on subscription-based vehicle services and a modular platform that could underpin multiple vehicle designs.

All three of these companies were desperately hunting for capital. Building cars is expensive. Really expensive. You need factories, tooling, supply chains, thousands of employees. The capital requirements are unlike software or even most hardware startups. A Series D round for an EV company wasn't

This is where David Stern saw opportunity.

David Stern: The Ghost in the Network

There's very little about David Stern visible on the public internet. His LinkedIn profile, if one exists, isn't easily accessible. He has no Wikipedia page. Before the DOJ released these documents, most people interested in tech or venture capital would have no idea who he is. This is unusual for someone who apparently had access to billionaires and business leaders across multiple continents.

What we know about Stern comes primarily from two sources: the emails released by the Department of Justice and a pitch deck for his fund AGC Capital, which is included in the documents. Together, they paint a picture of a man who understood how to position himself as a connector—someone who could bridge Chinese capital with Western opportunities, who had access to royalty, and who understood emerging technologies.

According to his own biography in the AGC Capital pitch deck, Stern is German. He attended the University of London in the late 1990s and also studied at Shi-Da University in China. These weren't random choices. The timing and selection of schools suggest a deliberate strategy: learn in London, learn in China, and position himself as someone who could work between the two ecosystems.

His professional path reinforces this interpretation. He served as chairman of Millenium Capital China, the Chinese subsidiary of Millennium Capital Partners. Before that, he worked for Siemens, where he negotiated industrial joint ventures with Chinese state-owned enterprises. He also spent time in Deutsche Bank's Shanghai office. Finally, he started a company called Asia Gateway in 2001 that positioned itself as an advisor to "blue chip companies, Chinese enterprises as well as the Chinese government in growth strategies and investments."

This background gave Stern something valuable in the mid-2010s: relationships with powerful and wealthy Chinese businessmen who had suddenly accumulated enormous wealth and were hungry for investment opportunities. It gave him credibility in conversations with Western entrepreneurs who believed China represented the future.

One of Stern's connections was particularly notable. Through his work in China, he apparently developed a relationship with Li Botan, who was the son-in-law of one of the four most senior leaders in China under Hu Jintao (Xi Jinping's predecessor). Li was tremendously connected in Beijing financial circles. Later, Li would become a founding investor in Canoo, specifically working with Stern.

But at some point in the mid-2000s, Stern's ambitions expanded beyond advising companies. He wanted to run his own fund. He wanted to manage capital himself. And to do that, he needed major investors. This is likely how he first approached Jeffrey Epstein.

Estimated data shows a significant increase in EV market investments from 2015 to 2017, reflecting the high interest and abundant capital in the sector during this period.

How Stern Met Epstein: The First Pitch

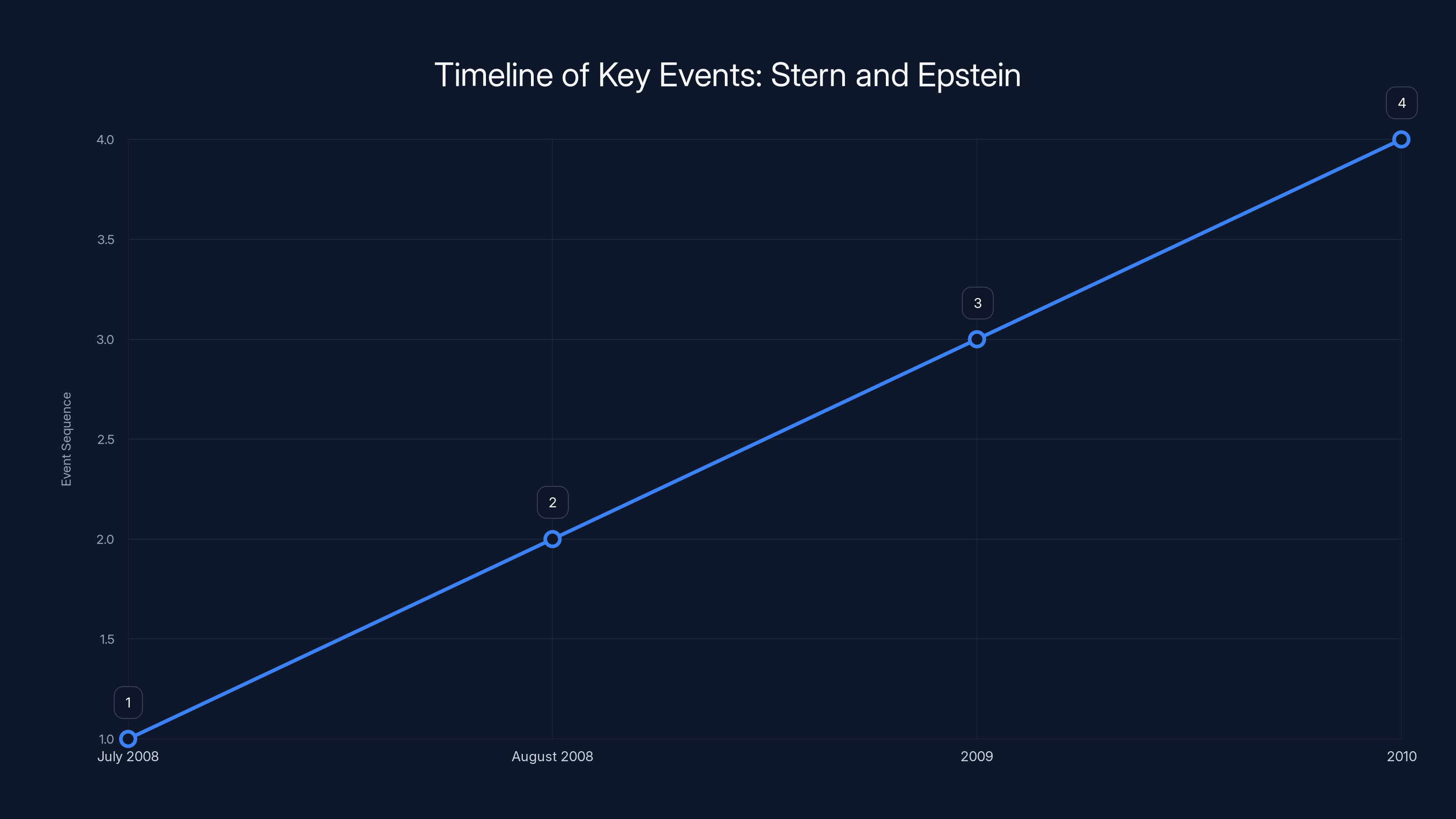

The documents don't explicitly say how Stern was introduced to Epstein. Stern himself didn't respond to detailed questions about this, according to reporting. But the first documented email in the DOJ files shows Stern reaching out in 2008, which is a significant date.

In August 2008, Stern was trying to raise capital for AGC Capital, his fund designed to take advantage of China's continued economic boom. The global financial crisis was underway—Lehman Brothers had just collapsed a month earlier, credit markets were frozen, and most investors were terrified. It was possibly the worst time to be raising a fund.

Yet Stern apparently had the audacity (or desperation) to approach Epstein. His pitch was straightforward: China was the future, his fund would capitalize on that, and Epstein should invest.

What happened next is interesting. Epstein had just pleaded guilty one month earlier, in July 2008, to soliciting a minor for prostitution in Florida. He'd negotiated a plea deal that allowed him to avoid federal charges and register as a sex offender. The scandal was contained, largely because of legal maneuvering and what many observers described as preferential treatment from the legal system.

By the time Stern approached him, Epstein was publicly disgraced but privately still managing his fortune and maintaining relationships. The fact that Stern approached him at this moment suggests either remarkable boldness or remarkable ignorance about what was happening in the news.

Whatever the case, Epstein apparently decided to engage with Stern. Over the next year, the two developed what seemed to be a productive relationship. Stern would pitch ideas. Epstein would respond with feedback, sometimes harsh, sometimes supportive. The dynamic evolved from transactional to something more personal.

By 2010, in one particularly revealing email, Prince Andrew himself referred to Stern as a "ghost," someone who seemed to exist in spaces between institutions but wasn't fully present in any of them. This was intended as a criticism—Andrew seemed concerned that Stern was too difficult to pin down, too evasive about his actual capabilities and results. But the description was oddly accurate. Stern was a ghost—visible when he needed to be, invisible otherwise.

Yet he'd somehow positioned himself as director of Pitch@Palace, Prince Andrew's startup contest. He was close enough to British royalty to be photographed at official events. He was connected to major Chinese businessmen. And he had Epstein's ear.

The Lucid Motors Pitch: Ford, Saudi Arabia, and a Blocking Position

By 2017, Lucid Motors was at an inflection point. The company had spent nearly a decade in development. It had built phenomenal prototypes. The technology was legitimate. But moving from prototype to actual production required something the company didn't have: more capital than anyone had raised for a car company before.

Lucid needed a Series D. It was targeting over $400 million. The company believed Ford would lead the round—Ford had the strategic interest, the capital, and the credibility to bring other investors along.

Then complications emerged. Jia Yueting, the founder of Faraday Future, had been buying shares in Lucid quietly. By 2017, he'd accumulated around 30% ownership. This was a dramatic conflict of interest. Jia was building his own electric vehicle company, and he now controlled a blocking stake in Lucid Motors. He could theoretically prevent any major decisions Lucid wanted to make, including raising new capital on terms he didn't approve.

Why had Jia done this? The most obvious explanation was leverage. By controlling Lucid, Jia could potentially negotiate with the company, potentially merge the two companies, or potentially extract concessions. It was a bold, arguably desperate move by someone who was watching Faraday burn through capital rapidly.

This is where David Stern saw an opportunity. If he could bring in another investor with enough capital and enough independence from the Jia situation, he could potentially break the logjam. Ford could proceed. Lucid could raise its Series D. Everyone wins.

Except Stern's proposed solution was to bring in Jeffrey Epstein.

In emails written in 2017, Stern wrote to Epstein with urgency: "Ford will likely be lead in $400m Series D in Lucid. Big strategic move." Stern explained that Jia Yueting "has massive cash issues" at Faraday and needs to "sell now to make payroll for his other business."

The implication was clear: Epstein could swoop in, potentially buy out or pressure Jia's position, and position himself as a major shareholder in what promised to be the next Tesla. It was a credible pitch because the market conditions made it believable. Lucid's technology was real. The need for capital was real. The opportunity seemed genuine.

But here's what ultimately happened: Lucid closed its Series D in late 2018, and the lead investor was Saudi Arabia's sovereign wealth fund, the Public Investment Fund (PIF). The round raised over $1 billion. There's no indication that Epstein's capital was involved.

Epstein may have been interested. He may have considered it. But ultimately, Lucid's future was determined by Middle Eastern oil wealth, not by Epstein's networks. The PIF had different strategic objectives—diversifying Saudi Arabia's economy away from oil dependency—and the capital to move at massive scale.

Faraday Future: The Collapsing Dream

Faraday Future represented ambition at its most extreme. Founded by Jia Yueting in 2014, the company aimed to build electric vehicles that would not just compete with Tesla but decisively outperform them. The company raised over $1 billion—an astonishing achievement for a startup with no revenue and no manufacturing experience.

Jia had made his fortune in China through Le Eco, a streaming and entertainment company that attempted to be the Chinese version of Netflix, Amazon Prime, and YouTube combined. At its peak, Le Eco was valued at $9 billion. Jia had the wealth to fund his automotive dreams, or so it seemed.

Faraday's Nevada factory was supposed to be revolutionary. The company was hiring top talent from Tesla and other automakers. The design of its first vehicle, the FF91, was genuinely stunning—a futuristic electric SUV that looked like nothing else on the road. On paper, Faraday looked like it could actually challenge Tesla's dominance.

But by 2017, the reality was catching up. Jia's wealth was increasingly tied to Le Eco's valuation, which was collapsing as the company burned cash. Faraday was consuming hundreds of millions of dollars annually with no revenue and no clear path to profitability. The factory, while impressive, was massively over-budget and behind schedule.

This is when Jia apparently decided to take a controlling stake in Lucid Motors. It was a bizarre move that suggests desperation. Perhaps he thought he could somehow merge the two companies. Perhaps he wanted leverage to negotiate with Lucid's investors for some kind of partnership. Perhaps it was simply the move of someone watching his entire empire crumble and trying anything to regain control.

David Stern, noting these "massive cash issues," apparently pitched Faraday itself to Epstein as an investment opportunity. The logic would have been straightforward: Faraday has real technology, real manufacturing capability, and just needs more capital to get through the critical next 18 months. An injection of capital could stabilize the company and position it as a major EV player.

But Faraday's problems were deeper than capital. They were organizational. They were about execution. And ultimately, they reflected the challenges of building a car company from scratch with a founder whose previous business was collapsing.

In late 2017, Faraday received investment from Evergrande, a massive Chinese real estate conglomerate. Evergrande invested heavily in the company and took a significant stake. For a moment, it seemed like Faraday might actually survive and thrive. But Evergrande's capital ultimately couldn't overcome the fundamental problems. By 2019, Faraday was essentially dead, having built only prototypes and never successfully producing a single vehicle.

There's no evidence that Epstein's capital was ever involved in Faraday. But the pitch was apparently made.

During the Electric Vehicle Gold Rush of 2015-2017, venture capital investment in EV startups surged, reflecting the high investor confidence in the sector's potential. (Estimated data)

Canoo: Chinese Capital Meets Silicon Valley

Canoo represented a different approach to the EV opportunity. Founded in 2017 by Tom Niedenthal and other designers who'd worked on Volkswagen's ID. Buzz concept vehicle, Canoo believed the future wasn't about building the world's best car. It was about building a modular platform that could underpin multiple vehicle types and offering them through a subscription service rather than ownership.

It was an interesting thesis, especially if you believed that ownership of vehicles might decline, that autonomous driving would arrive quickly, and that consumers wanted flexibility rather than permanent commitment. But it was also a thesis that required capital on an enormous scale—you still needed to build factories, develop the platform, produce vehicles.

Canoo's funding structure is particularly interesting because it reveals the networks Stern had developed. The company's founding investors included David Stern himself and Li Botan, Stern's connection to high-level Chinese capital.

According to emails included in the DOJ files, Epstein was pitched on Canoo as well. The company seemed like a more attractive opportunity than Faraday, which was already struggling. Canoo had fresh founders, a novel business model, and the backing of Chinese capital.

In a 2018 message included in the files, Epstein stated that he had no "direct" or "indirect" interest in Canoo. The specific language—distinguishing between direct and indirect investment—suggests he may have considered it but decided against it. Or perhaps he was being asked to take a position and declined.

Canoo's trajectory is instructive. The company did receive substantial capital and did build a manufacturing facility. But it was never able to achieve significant vehicle sales or profitability. By the early 2020s, the company had essentially pivoted to focusing on commercial vehicles rather than consumer cars. It struggled to differentiate itself in a market increasingly dominated by Tesla and legacy automakers who were now taking electrification seriously.

The subscription model that Canoo believed in never materialized as a major consumer preference. Vehicle ownership remained the norm. And the company's modular platform, while innovative, didn't provide a decisive competitive advantage.

The Nature of the Stern-Epstein Relationship

What's most striking about the documents is not the specific investment pitches but the nature of the relationship between Stern and Epstein. It wasn't transactional. It was personal and deeply hierarchical.

To Stern, Epstein was "my mentor, and I do what he tells me." This is the language of profound deference. Stern was not Epstein's equal. He was someone seeking Epstein's approval, guidance, and capital. When Epstein criticized him for poor deal preparation, telling him his "first grade is an F," Stern apparently accepted the rebuke without significant pushback.

To Epstein, Stern was "my china contact." This is the language of utility. Epstein valued Stern not as a friend or partner but as a tool. Stern provided access to Chinese capital, to Chinese businessmen, to investment opportunities that Epstein couldn't access directly.

This dynamic reveals something important about how Epstein operated in the wider financial world. He wasn't a simple predator confined to specific contexts. He was someone whose wealth and connections allowed him to participate in seemingly legitimate financial activities—venture capital, international investing, business deals.

The relationship lasted nearly a decade, from approximately 2008 to 2018 or later. During this entire period, Epstein was a registered sex offender. The 2008 plea deal had required him to register. He was aware of this status. The world was aware of this status, at least in outline form. Yet his financial networks continued, his business relationships persisted, and people continued to pitch him investment opportunities.

This speaks to a fundamental failure of due diligence in the venture capital world. When someone pitches an investment to a wealthy financier, how thoroughly do they investigate that person's background? Do they verify sources of funds? Do they investigate whether the person has faced legal problems that might make the capital problematic?

The documents don't show that Lucid Motors, Faraday Future, or Canoo ever actually accepted Epstein's capital. So this may ultimately be a story about pitches made but not executed. But it's a story that raises serious questions about the ecosystem within which those pitches occurred.

Who Actually Invested: The Successful Funding Rounds

To understand what the Epstein pitches mean, it's worth looking at who actually won these investments when Stern's pitches apparently didn't convert.

Lucid Motors, as mentioned, ultimately raised over $1 billion in its Series D from Saudi Arabia's Public Investment Fund. The PIF was actively diversifying Saudi Arabia's economy, investing in technology, energy, and transportation. For the PIF, backing Lucid made sense. It was backing not just a company but a new industrial future.

The PIF's investment proved problematic in different ways. By 2022, Saudi Arabia's involvement in Lucid became controversial due to geopolitical considerations, human rights concerns, and changing US policy toward Saudi Arabia. But in 2018, when the PIF backed Lucid, it seemed like a straightforward strategic investment.

Faraday Future, as mentioned, received investment from Evergrande. Evergrande was and is one of China's largest real estate companies, with massive capital reserves. Jia Yueting apparently convinced Evergrande that backing Faraday was a way to diversify into new industries and position Evergrande as a global player.

Evergrande's investment in Faraday was one of several bets the conglomerate was making. As a company, Evergrande eventually faced massive financial difficulties in the early 2020s, partially due to bad investments including Faraday.

Canoo ultimately raised capital from multiple sources, including strategic investments from Hyundai and others. The company sought to position itself as a technology partner to established automakers rather than as a competitor.

The point is that each of these companies found capital. The investments came from sovereign wealth funds, international conglomerates, and strategic partners. Whether these turned out to be good investments is another question—most didn't generate returns. But capital was available, and these companies accessed it.

The question is whether Epstein's capital, if it had been deployed, would have made a difference. Would it have changed outcomes? Probably not. Capital was plentiful in the EV space. The challenge wasn't finding money. It was execution. It was building cars that people wanted to buy at prices that made economic sense.

This timeline highlights the sequence of events from Epstein's guilty plea in July 2008 to the evolving relationship with Stern by 2010. Estimated data based on narrative context.

The Broader EV Startup Landscape: 2015-2020

To contextualize the Stern-Epstein pitches, it's worth understanding the broader landscape of EV startups during this period. There were dozens of companies attempting to build electric vehicles. Some were serious technical endeavors. Others were more hype than substance. All of them needed capital.

The startups that actually succeeded in building and delivering vehicles to customers were rare. Tesla was clearly the leader, but even companies like Nissan (with the Leaf) and Chevy (with the Bolt) had achieved meaningful scale. But these were either part of established automakers or, in Tesla's case, had solved the fundamental challenges of building cars at scale.

Most of the venture-backed EV startups struggled. Lucid, despite raising $1+ billion and connecting with Saudi Arabia's future vision, spent years behind schedule and over budget bringing its first vehicle to market. When the Lucid Air finally arrived in 2021, it was a superb car, but the company couldn't achieve profitability.

Faraday never built more than a handful of prototypes. Canoo pivoted multiple times, never finding a market that wanted its core vision. Nio, a Chinese startup, has been more successful, but even Nio has struggled with profitability despite raising billions.

This context matters because it suggests that Epstein's capital would not have been a game-changer. The challenges facing EV startups were not primarily financial. They were technical, manufacturing-related, market-related, and organizational. Throwing more capital at the problem didn't solve it.

What the Documents Reveal About Epstein's Financial Networks

The newly released documents shed light on something that had been largely opaque: Epstein's actual financial activities and investments during the years before his arrest. Epstein was known to be wealthy, valued at somewhere between

The documents show someone who was actively engaged in investing, who had reasonable business acumen, and who was willing to take risks on emerging opportunities. He wasn't just a money manager in the traditional sense. He was an investor with opinions, with preferences, and with the confidence to tell people when he thought they were wrong.

But the documents also show someone whose wealth gave him access that perhaps should have been denied. The tech industry, at least in 2017-2018 when these pitches were happening, apparently didn't run comprehensive background checks on potential investors. Or if it did, those checks didn't surface the information that Epstein was a registered sex offender or prevent the pitches from happening.

This raises uncomfortable questions about due diligence in the venture capital world. When you're raising capital, do you investigate the sources of that capital? Do you ask about potential investors' backgrounds? Do you consider the reputational or financial risks of taking capital from someone with a controversial past?

The venture capital world likes to think of itself as meritocratic and forward-looking. Capital is capital, the logic goes. The source doesn't matter if the business is sound. But this episode suggests that perhaps the source should matter more than it typically does.

Due Diligence Failures: The Uncomfortable Questions

This story raises a critical question that the startup world often avoids: Who is funding what, and should we actually care?

In most venture capital transactions, the focus is on the company's technology, market potential, team capability, and financial projections. The investor is largely taken at face value. If they have capital and are willing to invest, the assumption is that they've been through enough other deals that their money is legitimate.

But this assumption breaks down when you look at cases like Epstein's. Here was someone making investment pitches to some of the most technologically sophisticated startups in the world. Those startups were raising hundreds of millions of dollars. Their leadership teams included Harvard MBA graduates, Stanford engineers, and industry veterans. Yet apparently none of them ran sufficient background checks to surface the obvious fact that their potential investor was a registered sex offender.

Or perhaps they did, and they decided it didn't matter. That's also possible, and maybe even more concerning. The venture capital world can be remarkably cavalier about sources of capital, especially when capital is abundant.

The documents don't show that Lucid, Faraday, or Canoo actually engaged with Epstein directly. Stern was making the pitches. But presumably, someone at these companies would have researched who Epstein was before considering his capital. Would that research have changed anything?

We don't know. The documents don't provide that level of detail. But it's a question worth asking.

Canoo's capital raising efforts increased significantly from 2017 to the early 2020s, alongside a strategic pivot from consumer to commercial vehicles. (Estimated data)

The Role of Intermediaries: Why Stern Mattered

David Stern's role in this story is particularly interesting because it illustrates how financial networks operate through intermediaries. Stern wasn't an investor himself (though he apparently had some stake in Canoo). He was a connector, a facilitator, someone who could bridge worlds that didn't naturally connect.

Stern brought several things to the table. First, he had access to Chinese capital and Chinese businessmen, which was extremely valuable in the 2010s when many Western investors were trying to figure out how to tap into Chinese wealth. Second, he had connections to Prince Andrew and the British royal family, which lent him credibility and suggested he moved in rarefied circles. Third, he apparently had a relationship with Epstein that allowed him to pitch opportunities to a man with hundreds of millions of dollars to invest.

This is a common pattern in venture capital and private equity: the intermediary. Someone who knows everyone, who can connect two parties that wouldn't otherwise meet, who can explain one world to another. Intermediaries extract value from these connections. Sometimes they take a fee. Sometimes they take an equity stake. Sometimes they get intangible benefits like relationship capital.

But intermediaries also obscure. When Stern was pitching EV startups to Epstein, he was positioned as a neutral party. He was explaining market opportunities, not necessarily endorsing specific companies. But he had skin in the game—at least in Canoo, which had invested in and which lists him as a founder.

This creates conflicts of interest that aren't always transparent. Stern was presumably taking a fee from Epstein for bringing deals to him. He was also potentially benefiting from those investments if they succeeded. He was also positioning himself as valuable to the EV companies by potentially connecting them with capital.

Who was Stern primarily trying to serve? Probably himself. This is not necessarily nefarious. People in business often have multiple interests. But it's important to understand the incentives at play.

The Prince Andrew Connection: How Royalty Met Tech

One of the most striking aspects of this story is David Stern's position as director of Pitch@Palace, Prince Andrew's startup contest. This event ran for several years and was designed to provide entrepreneurs with access to pitch to Andrew and potentially other royal family members and wealthy individuals.

Pitch@Palace was not a venture capital fund. It was more of a networking event, a way for Andrew to position himself as engaged with innovation and entrepreneurship. The event attracted actual entrepreneurs pitching real companies. But it also gave Andrew (and, through him, Stern) visibility into what was happening in the startup world.

The Prince Andrew connection is worth dwelling on because it reveals how interconnected these worlds were. Andrew was a royal family member with investments and interests in various industries. Stern was his advisor and director of Pitch@Palace. Epstein was a financier who had a relationship with Andrew. These weren't separate bubbles. They overlapped significantly.

Andrew's connection to Epstein has been extensively documented and investigated. What these documents show is that the connection extended beyond personal friendship into the realm of business and investments. Epstein wasn't just someone Andrew knew socially. Epstein was someone who was apparently interested in the same business opportunities that the startup world was pursuing.

This is important context because it suggests that the tech industry was not isolated from broader networks of wealth and power. When startups were raising capital, they were operating in a world where capital came from many sources, including people who had significant legal and personal baggage.

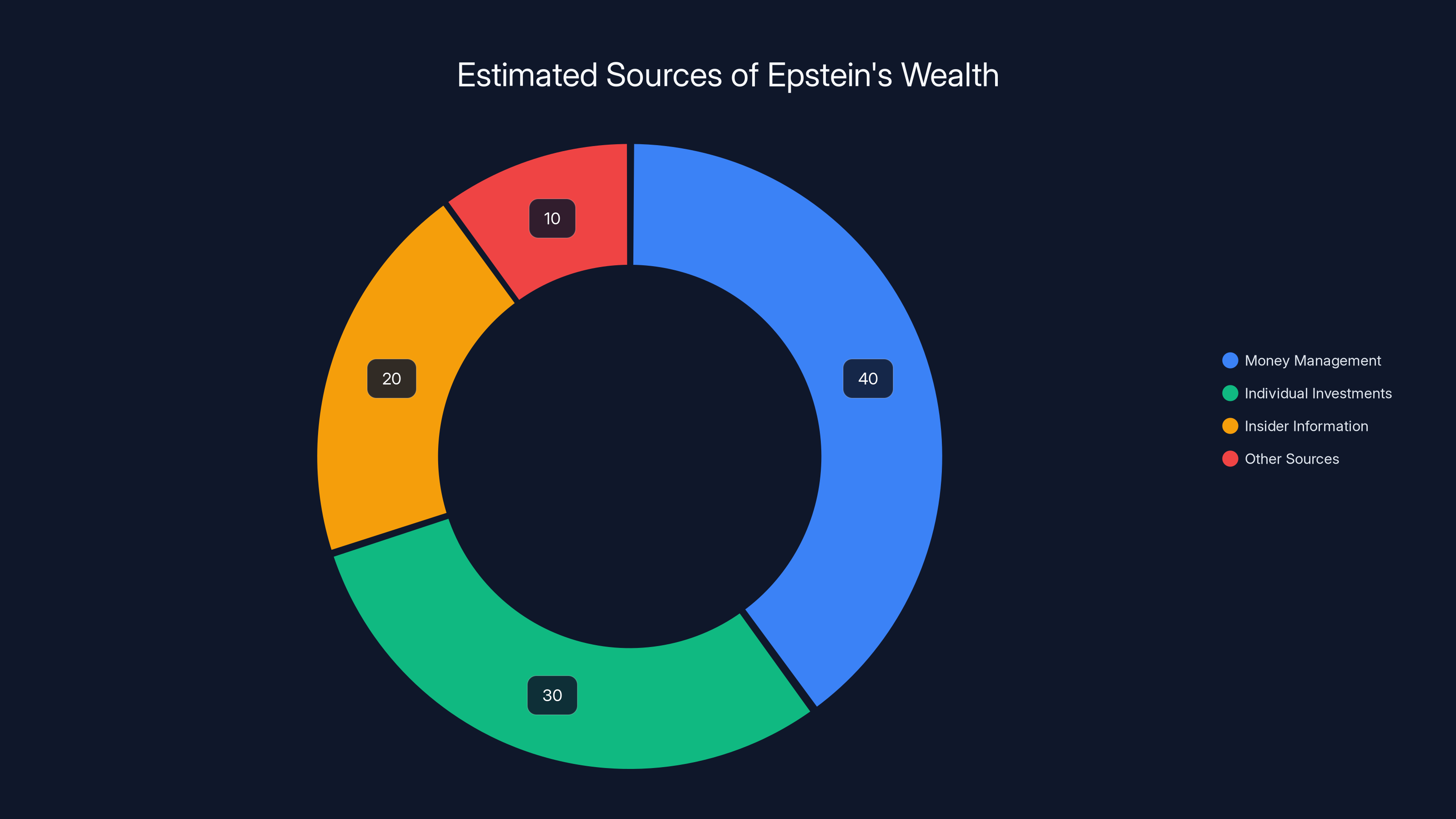

Epstein's Wealth: How Much, Where From, and Where It Went

The Epstein documents raise questions about the origins and disposition of his wealth. Epstein was primarily known as a financier—someone who managed money for wealthy clients. But where did his own wealth come from?

Historical reporting suggests that Epstein made significant gains from his work as a money manager, particularly in the 1980s and 1990s. He apparently had a good track record of investment returns, which allowed him to accumulate substantial capital. He also allegedly benefited from connections and information asymmetries that gave him advantages in certain deals.

But Epstein was not primarily a venture capitalist. He didn't run a fund. He made individual investments and bets. The documents show him pitching various business opportunities, including the EV startups, but also negotiating other deals.

What happened to Epstein's wealth after his arrest and death in 2019 is a different story, involving his estate, litigation, and settlements. But during his lifetime, and particularly during the 2015-2018 period when he was apparently interested in EV startups, his capital was actively deployed in the market.

The question of how much wealth actually derived from potentially problematic sources—whether from his money management business, from insider information, or from other means—is something that investigators and journalists continue to grapple with. The documents released by the DOJ provide some insight but don't fully answer the question.

What's clear is that someone with significant financial resources and significant legal baggage was operating in the startup ecosystem, pitching investments to companies that would eventually reshape transportation. Whether he would have actually deployed capital in any of these companies remains unclear.

Estimated data suggests Epstein's wealth primarily came from money management (40%) and individual investments (30%), with insider information and other sources contributing less.

What Actually Happened: The Non-Outcomes

One of the most interesting aspects of this story is what didn't happen. Stern pitched Epstein on Lucid Motors, Faraday Future, and Canoo. As far as the available documents show, Epstein didn't invest meaningfully in any of them.

Lucid went on to raise from Saudi Arabia's PIF. Faraday received investment from Evergrande. Canoo found capital from other sources and strategic partners. None of these companies ultimately required Epstein's capital. All of them found other investors.

This raises the question: Why were these pitches even made? If Epstein was ultimately not going to invest, what was the point?

One explanation is that Stern was doing what intermediaries do: exploring every possibility, keeping clients aware of opportunities, maintaining activity and engagement. Even if an investment doesn't happen, the conversation itself has value. It keeps Stern positioned as someone with access to investment opportunities. It reminds Epstein that Stern is actively working on his behalf.

Another explanation is that these pitches were opportunistic. Stern saw companies struggling to raise capital and approached Epstein, hoping he might be interested. If the capital came through, great. If not, no harm done. There's no indication that anyone at Lucid, Faraday, or Canoo ever actually engaged seriously with Epstein's potential participation.

A third explanation is that Epstein was genuinely interested in some of these opportunities but ultimately decided against them. The documents do show him engaging thoughtfully with business proposals, sometimes asking good questions, sometimes criticizing inadequate preparation. Perhaps after due consideration, he concluded that EV startups, for all their promise, weren't where he wanted to deploy capital.

Whatever the case, the non-outcomes matter. This is a story about pitches made but not executed. It's a story about networks and connections that existed but didn't ultimately reshape outcomes. In that sense, it's perhaps less dramatic than it might initially appear. But it's still revealing about how wealth, power, and investment opportunity intersect.

The Broader Implications: Capital and Scrutiny

These documents have implications that extend beyond the specific companies and people involved. They raise broader questions about how capital flows in the startup ecosystem and what kinds of scrutiny actually happens.

The venture capital industry prides itself on merit-based evaluation. The best ideas get funded. The best teams win. Capital flows to the most promising opportunities. The ideology is Darwinian: the market will sort things out.

But this story suggests that in reality, capital is more about networks, relationships, and opportunities than pure meritocracy. Stern had relationships that allowed him to pitch Epstein on investments. Those relationships existed because of previous work, previous connections, and previous successes in bridging different financial worlds.

The companies being pitched to didn't necessarily select Epstein as an investor. Instead, Stern brought the opportunity to them. They could accept or decline. In these cases, they apparently declined. But the fact that the pitch happened at all suggests a lack of scrutiny.

Modern startup funding is better about this than it was in 2017. Serious startups now conduct extensive due diligence on major investors. They verify sources of funds. They check backgrounds. They consider reputational risks. But at the time these pitches were happening, such scrutiny was less universal.

The broader implication is that startup founders and investors should always know where capital is coming from and understand the background of people they're doing business with. Not because the business world needs to be moralistic or because past legal problems should automatically disqualify someone from investing. But because understanding these connections and networks matters for good decision-making.

The EV Industry in Hindsight: Winners and Losers

As of 2024-2025, we can look back at the EV startup wave of the 2010s and see how things actually turned out. The narrative has evolved considerably from what it was in 2017.

Tesla, the original disruptor, is now the profitable incumbent. The company faces competition, yes, but it controls a commanding market share and has demonstrated the ability to produce vehicles profitably at scale. Legacy automakers like Ford, GM, Volkswagen, and others have now substantially committed to electric vehicles. The market is moving the way many predicted it would.

But the venture-backed startups largely haven't succeeded. Lucid Motors has delivered vehicles but struggles with profitability and scaling. Faraday Future never successfully produced vehicles. Canoo similarly has not found a path to profitability. Nio has done better than many others, but even Nio has faced significant challenges.

Several other startups funded during this era have also struggled or failed: Fisker went bankrupt and was revived; Karma has remained a tiny player; XPeng and Li Auto have found traction in China, but have not dominated globally.

The lesson seems to be that while the market prediction was correct (EVs would become dominant), the venture capital bet on startups to drive that transformation was largely incorrect. The real transformation has been driven by established automakers and Tesla, not by the dozens of venture-funded startups.

This doesn't mean the venture capital was wasted. Some of the technology developed by failed startups was absorbed by larger companies. Some of the founders went on to start other successful companies. But from a pure investment return perspective, most venture investors who backed EV startups in the 2015-2020 period did not achieve meaningful returns.

In that context, Epstein's apparent disinterest (or inability to achieve actual investments) in these companies is perhaps not such a loss. The capital that did flow into companies like Lucid ultimately came from sources like Saudi Arabia's sovereign wealth fund, which has the deep pockets to weather the long timelines and challenges of building an automaker from scratch.

Privacy, Opacity, and the Epstein Files

The release of these documents by the Department of Justice represents a broader trend toward transparency about Epstein's actual activities and connections. For years, much of what Epstein did was opaque. He operated in private, his relationships known only to him and his associates.

The documents that have been released over the past few years have gradually revealed the extent of his networks. These documents show connections to universities, to financial institutions, to politicians, and now to prominent tech startups. Each release has expanded our understanding of how embedded Epstein was in certain circles.

But even with these releases, significant opacity remains. The documents show pitches being made, but they don't show all the details of what actually happened. They show relationships, but not always the full nature of those relationships. They reveal names and connections, but not always the full context.

This is partly due to redactions for privacy and legal reasons. It's partly because some records simply don't exist or were destroyed. But it's also inherent in the nature of private financial dealings. Much of what happens in the world of wealthy individuals, big money, and investment opportunities is not documented in ways that become public.

The release of these documents is important for understanding how financial networks operate and how someone with Epstein's background could maintain access to high-level business opportunities. But it's also important to recognize that what's revealed is probably just the tip of the iceberg. For every email that's been released, there were probably hundreds that are still private.

Lessons for the Startup Ecosystem

What should startup founders and investors take from this episode?

First: Know who you're taking capital from. This seems obvious, but apparently it wasn't universal practice in 2017. Do your own background research. Ask questions. Verify sources of funds. Consider whether taking capital from certain sources could create reputational or legal risks.

Second: Understand the incentives of intermediaries. When someone brings you an investment opportunity, understand what they're getting out of it. Are they taking a fee? Do they have stakes in other companies? Are they trying to build a relationship with the potential investor? Understanding incentives helps you evaluate whether the pitch is genuinely in your interest or primarily in the intermediary's interest.

Third: Capital is necessary but not sufficient. Companies like Lucid Motors raised billions of dollars and still couldn't achieve profitability or scale. Capital is important, but execution is ultimately what matters. Be thoughtful about how much capital you actually need and what specific milestones you need to achieve with each funding round.

Fourth: The startup world is not isolated from broader power networks. Money comes from somewhere. It's tied to people with histories, motivations, and sometimes problematic backgrounds. Understanding these connections matters for good decision-making.

Fifth: Due diligence is bidirectional. While startups worry about investor due diligence (will this investor help us or harm us?), investors should also be conducting due diligence on startups. And startups should be thinking about whether they're comfortable with the sources of capital they're accessing.

FAQ

What was David Stern's role in the EV startup ecosystem?

David Stern was a businessman and advisor to Prince Andrew who positioned himself as a connector between Chinese capital and Western investment opportunities. He apparently had relationships with wealthy Chinese businessmen and access to Jeffrey Epstein's capital, which he leveraged to pitch various EV startups on investment opportunities. Stern served as director of Pitch@Palace, Prince Andrew's startup contest, and was listed as a founding investor in Canoo.

Why did Stern pitch Epstein on EV startups specifically?

The EV market in the 2015-2017 period was exceptionally hot. Capital was abundant, valuations were high, and the market believed electric vehicles represented the future of transportation. Stern, positioning himself as an investor facilitator, apparently sought to connect Epstein with these opportunities. Whether Stern received fees for brokering deals or had other motivations is not entirely clear from the available documents.

Did Epstein actually invest in any of the EV startups that were pitched to him?

Based on the available documents, there is no evidence that Epstein invested meaningfully in Lucid Motors, Faraday Future, or Canoo. Lucid ultimately raised from Saudi Arabia's Public Investment Fund. Faraday received investment from China's Evergrande. Canoo found capital from other strategic investors. Epstein stated in a 2018 message that he had no direct or indirect interest in Canoo.

What does this episode reveal about startup funding practices in the 2010s?

The episode suggests that due diligence on investor backgrounds was less rigorous than it arguably should have been. A registered sex offender was apparently able to pitch investment opportunities to some of the most sophisticated tech startups in the world without those companies systematically investigating his background. This raises questions about how thoroughly startups vetted potential investors and considered reputational and legal risks.

How has Epstein's involvement with Lucid, Faraday, and Canoo affected those companies?

The companies ultimately found capital from other sources and were not dependent on Epstein's capital. However, these documents have created retrospective questions about due diligence and about what other companies or individuals may have been connected to Epstein. For the companies involved, the primary impact is likely reputational: they're now associated with someone with a deeply problematic history, even if they never actually did business with him.

What was the relationship between Stern and Epstein?

According to the documents, Stern viewed Epstein as his mentor and apparently deferred to him significantly in business matters. Epstein viewed Stern primarily as a tool to access Chinese capital and business opportunities. The relationship lasted approximately a decade, from around 2008 to 2018. Epstein criticized Stern's work quality at times, and Stern accepted the criticism without apparent pushback, suggesting an imbalanced relationship.

Why were these new documents released by the Department of Justice?

The documents were released as part of a broader disclosure of records related to the Epstein investigation and prosecution. The release was made public in February 2025 and included 3 million pages of documents. The release was intended to increase transparency about Epstein's activities and connections, though some documents were redacted for privacy and security reasons.

What ultimately happened to the EV startups mentioned in the documents?

Lucid Motors remains operational as of 2025 but has struggled to achieve profitability despite raising over $1 billion in capital. Faraday Future never successfully produced vehicles at scale and is essentially defunct. Canoo pivoted multiple times and has not achieved profitability or significant market presence. None of the three has become a Tesla competitor or a transformative force in automotive.

Conclusion: When Networks Fail to Connect

The story of David Stern pitching Jeffrey Epstein on EV startups is fundamentally a story about networks that exist but don't fully connect. Stern had access to capital and capital seekers. Epstein had capital and apparently had interest in deploying it. The EV startups needed capital desperately. All the pieces seemed aligned for deals to happen.

But the deals didn't happen, at least not with Epstein's capital. Instead, the companies found other sources of funding. The outcome wasn't dependent on Epstein's participation. The market moved forward without him.

What these documents reveal is less about the specific investments and more about how financial networks operate. They show that someone with a deeply problematic background could maintain access to high-level business opportunities. They show how intermediaries like Stern operate to connect different worlds. They show how abundant capital in certain sectors can create opportunities for deal-making that might not otherwise exist.

The broader implication is that startup founders and investors should understand the sources of capital and the backgrounds of people involved in financial deals. This isn't about moralism or judgment. It's about making informed decisions and understanding the networks and incentives at play.

The EV startup boom of the 2015-2020 period ultimately didn't produce the dominant players that many people predicted it would. That story is often attributed to market forces, execution challenges, and capital requirements. But it's also a story about due diligence, about knowing who you're dealing with, and about understanding where capital actually comes from.

For the next generation of startup founders and investors, the lesson is straightforward: do your research. Understand incentives. Know who you're taking money from or giving money to. The startup ecosystem works best when these relationships are transparent and when all parties understand what they're actually involved in.

The Epstein files provide an uncomfortable but important reminder that not all capital is equally suitable, and not all relationships are equally aligned with long-term success.

Key Takeaways

- Newly released DOJ documents show David Stern pitched Jeffrey Epstein on investing in major EV startups like Lucid Motors, Faraday Future, and Canoo during the 2015-2018 period

- The Stern-Epstein relationship lasted nearly a decade, with Stern describing Epstein as his 'mentor' and Epstein valuing Stern as his 'china contact' for accessing wealthy Chinese businessmen

- Despite the pitches, there is no evidence Epstein invested meaningfully in any of these companies; Lucid raised from Saudi Arabia's PIF, Faraday from Evergrande, and Canoo from other strategic investors

- The episode reveals significant gaps in startup due diligence regarding investor backgrounds, with startups apparently not systematically investigating the backgrounds of potential major investors

- Most venture-backed EV startups from this era ultimately failed to achieve profitability or scale, suggesting that Epstein's capital would likely not have changed outcomes in any of these companies

Related Articles

- Why Loyalty Is Dead in Silicon Valley's AI Wars [2025]

- How Elon Musk Is Rewriting Founder Power in 2025 [Strategy]

- Reddit's Acquisition Strategy for 2025: Why Adtech & AI Matter [2025]

- SNAK Venture Partners $50M Fund: Digitalizing Vertical Marketplaces [2025]

- The Jeffrey Epstein Fortnite Account Conspiracy, Debunked [2025]

- Why Samsung's Galaxy S26 Faces Massive Hype Crisis [2025]