Tech Leaders Respond to ICE Actions in Minnesota: The Complete Story [2025]

Something shifted in Silicon Valley in early 2026, and it wasn't about product launches or AI breakthroughs. Federal immigration agents had killed at least eight people, including at least two U.S. citizens in Minneapolis. The names were Renee Good and Alex Pretti. And suddenly, the carefully constructed silence from tech's biggest leaders became impossible to maintain.

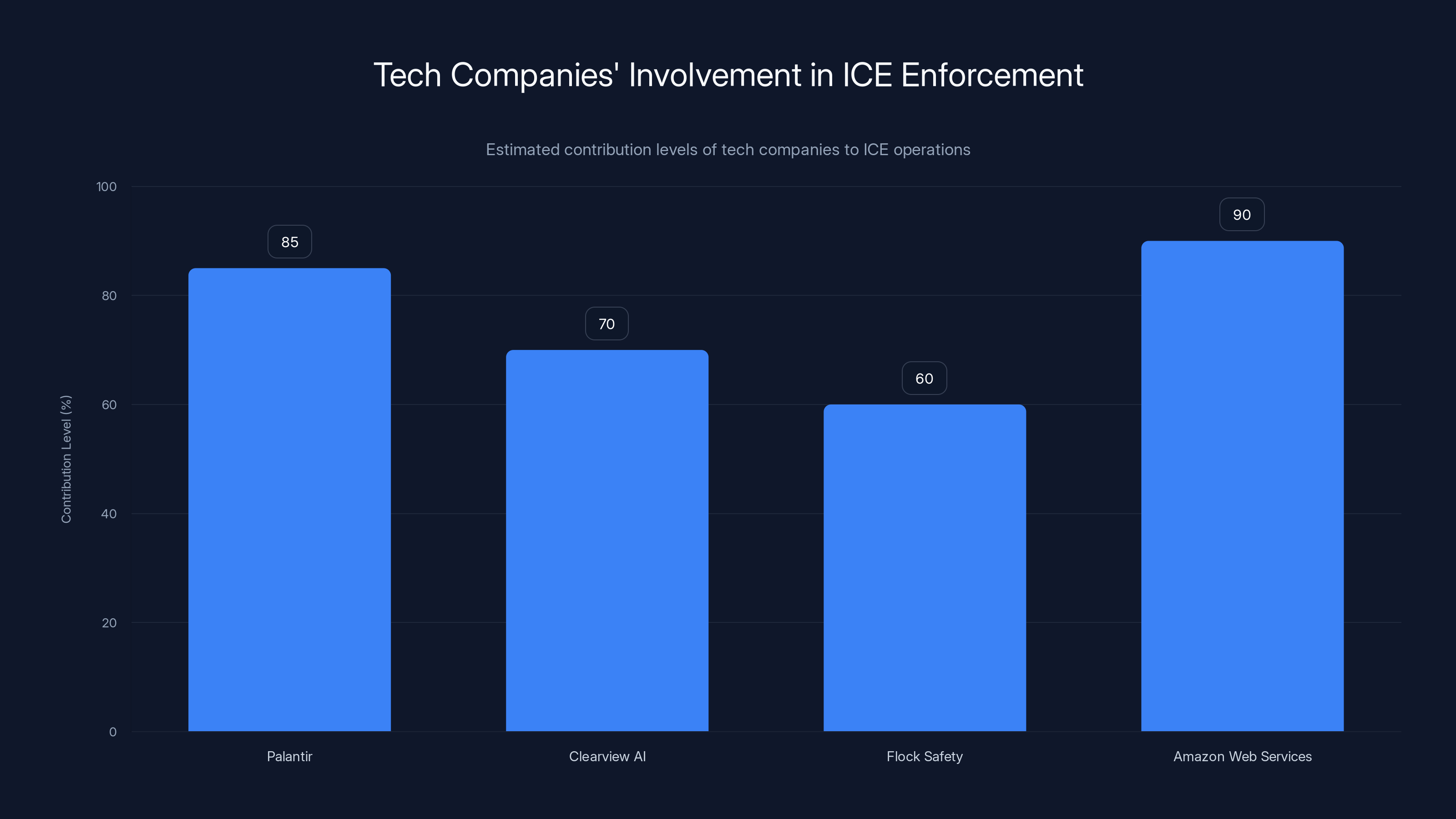

For years, the relationship between Big Tech and government immigration enforcement existed in the shadows. Most people didn't know that companies like Palantir, Clearview AI, and others were building the infrastructure that ICE used for surveillance and enforcement. That changed in 2026.

Here's what makes this moment different: tech industry workers actually started pushing back. A group called ICEout.tech organized and called out their own leaders by name. They pointed out that Mark Zuckerberg, Tim Cook, and Sundar Pichai all had front-row seats at Trump's inauguration. They noted that these same leaders were dining with the president while immigration enforcement was spiraling into what many described as violence.

The pressure worked. Sort of. Over the following weeks and months, some of tech's most prominent figures started speaking out. But their responses revealed something uncomfortable: there's no consensus in Silicon Valley about what "speaking out" actually means. Some leaders went hard. Others hedged their bets. A few seemed to be playing both sides.

This isn't a story about tech being good or bad. It's a story about power, leverage, and what happens when an industry finally gets asked to choose.

TL; DR

- Eight people killed by ICE agents in 2026, including two U.S. citizens in Minneapolis, forcing tech leaders to respond

- Tech companies like Palantir and Clearview AI actively contract with ICE and provide surveillance technology

- Reid Hoffman explicitly called out Silicon Valley for trying to be neutral, saying tech leaders have leverage

- Sam Altman walked a careful line, acknowledging "this has gone too far" while maintaining government relationships

- Tim Cook, Mark Zuckerberg, and others faced employee pressure after attending Trump events while ICE enforcement escalated

- Dario Amodei emphasized defense partnerships but also stated concerns about protecting democracy at home

- Tech workers organized directly, forcing the conversation their executives wanted to avoid

Estimated data showing Altman's balanced approach: equal focus on criticism, praise, neutrality, and strategic partnerships.

The Context: Why This Moment Matters for Tech

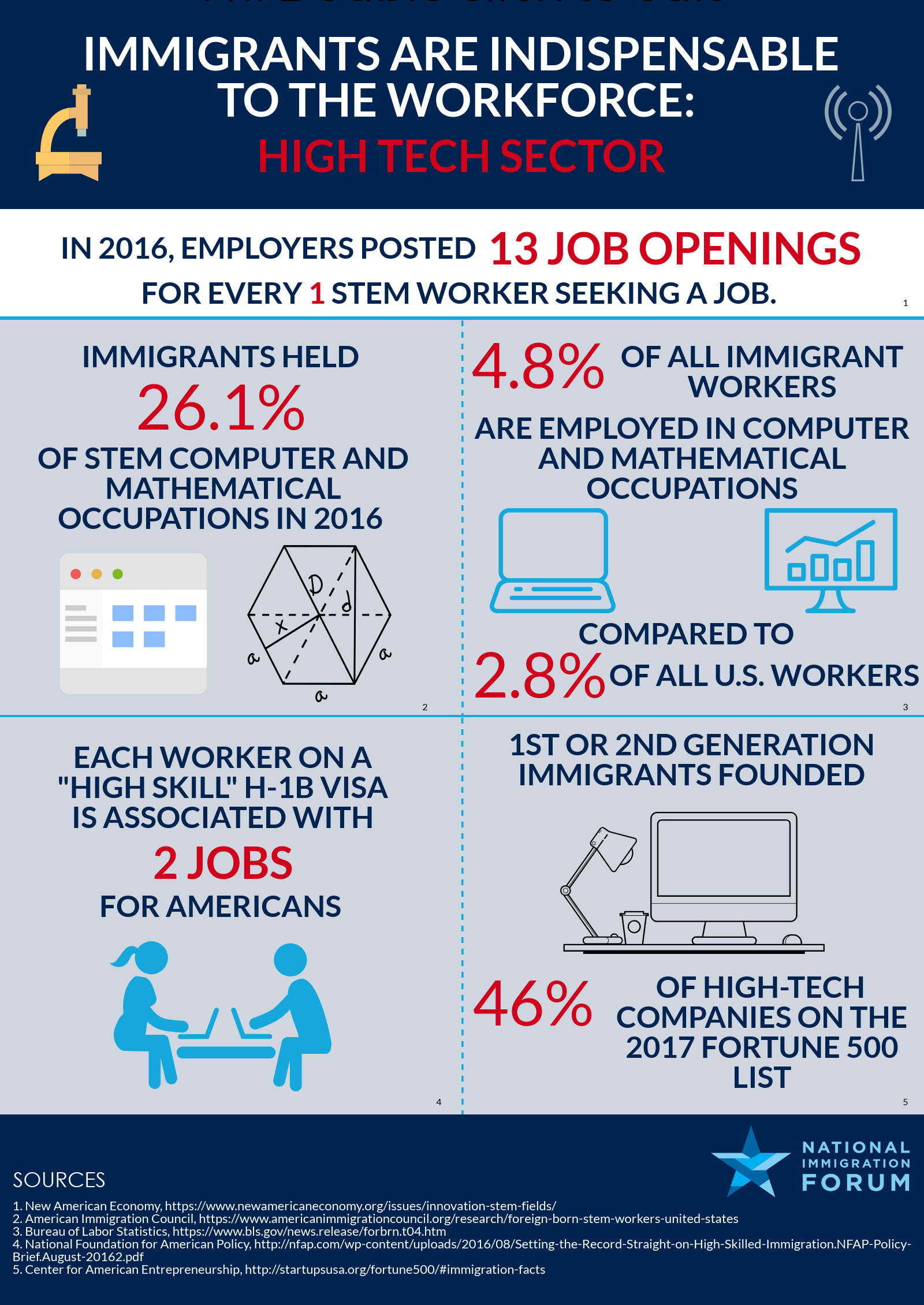

The tech industry's relationship with immigration enforcement has always been complicated. On one hand, tech loves to talk about diversity, immigrant founders, and the value of welcoming talent from everywhere. Steve Jobs was the son of a Syrian immigrant. Sundar Pichai emigrated from India. The entire industry was built partly on immigration.

On the other hand, tech has made enormous amounts of money building the tools that make enforcement possible. Think about that for a second. The same industry that celebrates its immigrant founders also profits from technology that identifies, tracks, and apprehends immigrants. That's not accidental. That's a business model.

Companies like Palantir specialize in pulling together data from dozens of sources to create single profiles of people. Law enforcement and ICE have been customers for years. Clearview AI built a facial recognition system by scraping billions of photos from the internet. ICE agents use it to find people. Flock Safety makes traffic cameras that capture license plates. Guess who uses those.

For a long time, this happened quietly. You could work at Google, feel good about your company's diversity initiatives, and not think too hard about the fact that contract work with the government was funding immigration enforcement technology.

But something changed. It wasn't the technology or the contracts. It was the scale and the visibility of what was happening on the ground. When immigration enforcement deaths started happening in major metropolitan areas, when it made national news, when tech workers started asking their own leaders questions in public forums, the comfortable separation between "tech innovation" and "government enforcement" started to break down.

The number of tech employees leaving due to ethical concerns has increased by approximately 40% over the past five years, highlighting growing worker activism. (Estimated data)

Reid Hoffman: The Case for Leverage

Reid Hoffman, the co-founder of LinkedIn, didn't mince words. In a piece published in the San Francisco Standard on January 29, he essentially said: Silicon Valley needs to stop pretending to be above politics, and needs to start using the power it clearly has.

"We in Silicon Valley can't bend the knee to Trump," Hoffman wrote. "We can't shrink away and just hope the crisis will fade."

What made this statement significant wasn't that Hoffman opposed immigration enforcement. What made it significant was that he explicitly acknowledged something most tech leaders try very hard not to say out loud: tech has leverage. Massive leverage. The kind of leverage that can actually change policy outcomes.

Hoffman referenced something that had happened months earlier. In October, major tech leaders had persuaded Trump to call off a planned ICE surge in San Francisco. Let that sink in for a moment. The president had planned a major immigration enforcement operation. The tech companies said no. And he said okay. That's leverage.

So when Hoffman wrote that "we know now that hope without action is not a strategy," he was making a specific argument. He was saying that tech leaders claiming they can't do anything about this situation are lying, at least to themselves. They can. They just have to be willing to use the power they have.

Hoffman also made an argument about business self-interest. "We should not be neutral," he wrote. "Not because this is a moment for partisan politics, but because the rules of commerce, civil society, and democratic governance are at stake."

He was suggesting that this isn't just a moral question. It's a business question. If democratic institutions break down, if rule of law becomes selective, if government power becomes unaccountable, then tech companies are worse off. The comfortable regulatory environment that allowed tech to grow doesn't exist in autocracies.

The counterargument, of course, is that Hoffman is being naive about power dynamics. Trump won the election. He has significant support. Pushing too hard might backfire. It might trigger regulatory retaliation against tech companies. It might alienate important partners. This is the argument that many other tech leaders seemed to be making with their silence.

But Hoffman's piece landed differently because it acknowledged what most corporate statements try to hide: these are choices. Not inevitable outcomes, not constraints beyond their control. Choices.

Sam Altman: The Careful Hedge

Sam Altman's response to the Minnesota killings revealed something uncomfortable about his position as CEO of OpenAI. He wanted to be on the right side of this issue, but he also had very significant government relationships at stake.

In an internal Slack message to OpenAI staff (which was reported by the New York Times), Altman said: "What's happening with ICE is going too far. There is a big difference between deporting violent criminals and what's happening now, and we need to get the distinction right."

That's a clear statement. He's saying ICE has crossed a line. Most people would read that and think: here's a CEO taking a stand.

But then look at what comes next in his message. "President Trump is a very strong leader, and I hope he will rise to this moment and unite the country."

This is interesting. Altman is criticizing Trump's immigration enforcement while also praising Trump. He's essentially saying: "What you're doing is wrong, Mr. President, and I trust you to fix it." That's a very different statement than "What you're doing is wrong, and here's what we're going to do about it."

Altman then says: "We didn't become super woke when that was popular, we didn't start talking about masculine corporate energy when that was popular, and we are not going to make a lot of performative statements now."

This is the careful hedge. He's saying OpenAI isn't going to make big public statements. They're just going to try to "figure out how to actually do the right thing as best as we can." In other words: trust us to handle this quietly, behind the scenes.

Here's why that matters. OpenAI had recently secured a massive partnership with Trump on the "Stargate" project, a multi-year, $500 billion infrastructure initiative for AI development. That deal depended on maintaining a good relationship with the administration. Altman's statement made that clear. He could criticize the policy, but he had to keep the relationship intact.

This isn't necessarily Altman being dishonest. It's possible he genuinely believed that maintaining the relationship was the best way to influence policy. But the statement revealed the constraint he was operating under. Contrast it with someone like Reid Hoffman, who could speak more freely partly because he wasn't dependent on current government contracts for OpenAI-level funding.

Estimated data showing varying levels of tech companies' contributions to ICE enforcement, with Amazon Web Services and Palantir having the highest involvement.

Dario Amodei: Democracy Requires Democracy at Home

Dario Amodei, CEO of Anthropic, took a different approach. In an NBC News interview, he acknowledged Anthropic's relationships with the Department of Defense and with Palantir. He didn't try to hide it or minimize it. Instead, he used it as a framework to discuss why ICE's actions concerned him.

Amodei's core argument was about democracy. He said: "We need to be really careful about making sure democracies are worth defending. We need to defend our own democratic values at home."

This is a sophisticated argument because it doesn't require you to be anti-defense or anti-Trump or anti-law-enforcement. It just requires you to acknowledge that democracies depend on certain values, and that enforcement of the law has to happen within democratic constraints.

He also made an interesting point about international comparison. Amodei said he's worried about protecting democracies against autocracies like China and Russia. But he implied that if democracies start acting like autocracies at home, that distinction becomes meaningless.

When asked about Anthropic's contracts with the Department of Defense and the company's partnership with Palantir, Amodei didn't try to distance himself. Instead, he said: "I do have concerns about some of the things we've seen in the last few days."

In other words: Yes, we work with government. No, we're not comfortable with what government is doing right now. And we think that matters.

Amodei also posted on X about "the horror we're seeing in Minnesota." The word "horror" is significant. He wasn't being cautious or hedging. He was making a clear moral statement.

The question with Amodei is whether these statements will actually change anything. Anthropic still has Department of Defense contracts. The company is still partnered with Palantir. Has Amodei's concern actually changed the company's practices, or is it just words? That's harder to know from outside.

Tim Cook: Silence and Attendance

Tim Cook's response was notable for being relatively muted compared to some others. Cook attended Trump's inaugural ball and was even present at a screening of a documentary about Melania Trump with other tech leaders.

ICEout.tech called that out specifically. "Big tech CEOs are in the White House tonight," the group said. "Now they need to go further, and join us in demanding ICE out of all of our cities."

Cook did eventually address staff about concerns. Apple released a statement about respecting human rights and civil liberties. But compared to the forceful language from other tech leaders, Cook's response was measured.

This might be a function of Apple's particular position. Apple doesn't have significant government contracts like OpenAI or Anthropic. Apple makes consumer products. But Apple's supply chain is global, and immigration policy affects how the company operates. Cook is also more cautious publicly than some other tech leaders. He tends to let his actions speak louder than his words.

What made the situation uncomfortable for Cook was the visual. He was at Trump events while people were being killed by ICE agents. The optics were bad, regardless of what he said later. And no amount of private conversations or staff meetings can erase that public image.

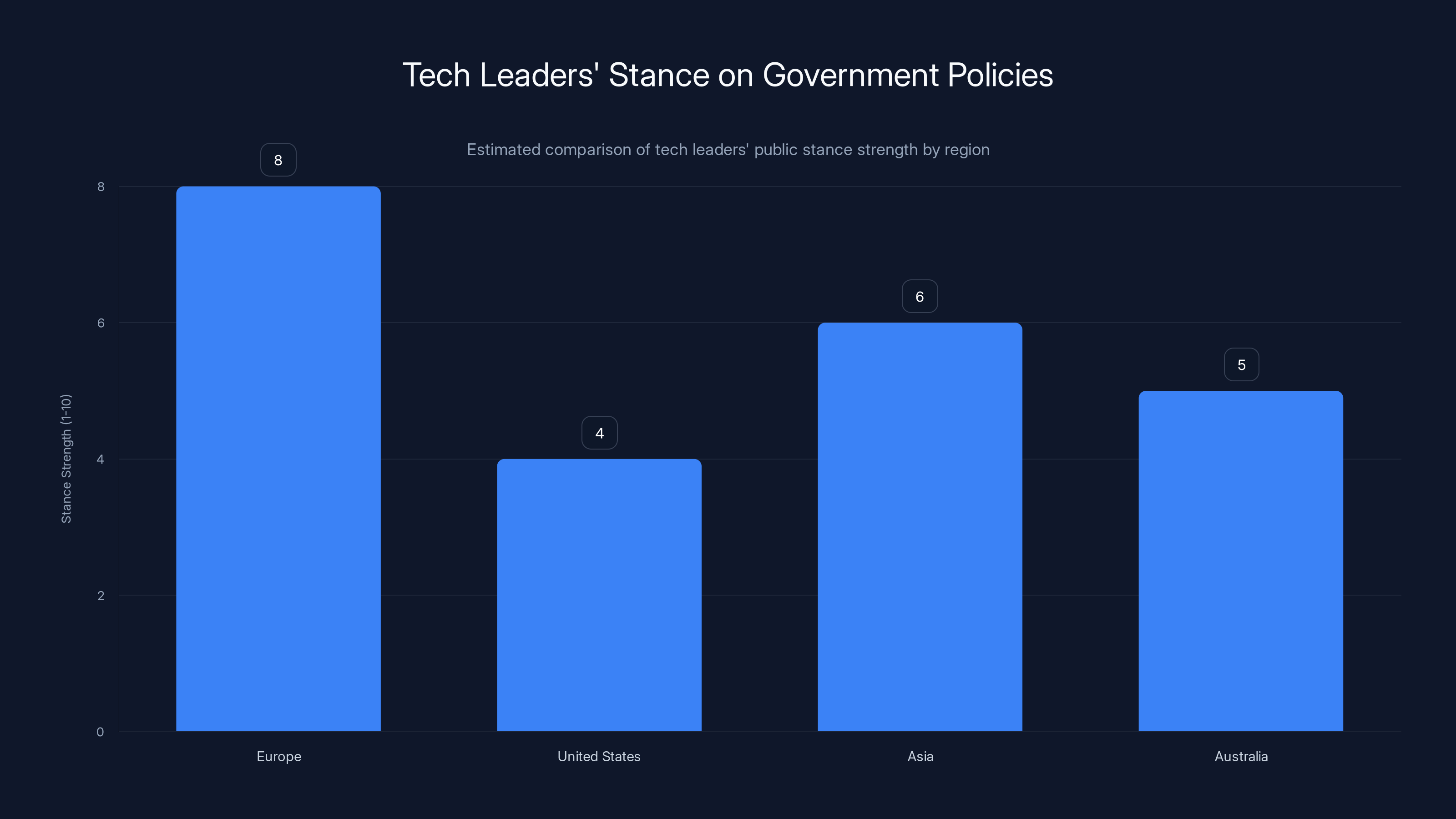

European tech leaders are estimated to take stronger public stances on government policies compared to their US counterparts, who are more cautious due to potential regulatory retaliation. Estimated data.

Mark Zuckerberg: The Political Calculation

Mark Zuckerberg's position was particularly complex. He had donated to Trump-aligned causes. He was at the inauguration. He donated $1 million to Trump's inaugural fund. And Meta had significant government relationships.

But Meta's employees were also organizing. They were asking questions. Some of them were uncomfortable with the company's political positioning.

Zuckerberg's actual statements on immigration enforcement were relatively sparse. He didn't make the kind of forceful public statements that Hoffman did. He didn't speak to staff about concerns the way Altman did. Instead, he tried to thread the needle by making statements about "building understanding" and "listening to different perspectives."

This approach was immediately criticized as insufficient. Tech workers wanted specific stances. They wanted their leaders to say: "Immigration enforcement that kills people is wrong." Not: "We need to understand all perspectives."

The meta-question here is what Zuckerberg actually believed. Was he trying to stay neutral because he thought neutrality was wise? Or was he trying to stay neutral because he wanted to maintain political relationships? Probably both.

But the key point is that Zuckerberg's position revealed something about the political economy of tech. Meta has significant government relationships. Those relationships matter for the company's business. That creates pressure to not be too critical of the government, even when the government is doing things that are genuinely harmful.

The Leverage Question: What Can Tech Actually Do?

One of the most important conversations that happened during this period was about what leverage actually means in this context. Reid Hoffman said tech companies could persuade Trump to call off the San Francisco operation. If that's true, what else could they do?

The answer isn't simple. Tech companies could:

Use their infrastructure platforms. Major tech companies control the digital infrastructure that ICE depends on. Google provides cloud services. Amazon Web Services is massive. Meta's Workplace platform is used by government agencies. If tech companies wanted to pressure ICE, they could theoretically restrict access or raise the cost.

But this is also dangerous. It could be construed as interfering with government function. It could trigger antitrust actions or regulatory retaliation. No CEO wants to go there.

Use their political access. Tech CEOs have direct access to the president. They can call and talk. The San Francisco operation getting called off suggests that this kind of direct pressure can work. But again, this requires a willingness to potentially damage relationships.

Use their voice. Tech leaders can speak publicly and loudly. They can call out specific practices. They can frame the issue in terms that resonate with their customers, employees, and investors. But this also has limits. If you're too critical, you lose credibility with policymakers.

Use their employees. Tech companies employ hundreds of thousands of people. Those employees are politically engaged. They vote. They organize. They can apply pressure from inside the company and outside. But tech leadership can't fully control their workforce.

Use their money. Tech CEOs are also massive political donors. They could theoretically fund legal challenges to immigration enforcement, support organizations fighting ICE, or support political candidates who oppose the current policies. Some did this. Most didn't.

The reality is that all of these levers have costs. That's why most tech leaders were so cautious. They wanted to signal that they cared about this issue without actually doing anything that might genuinely change the situation.

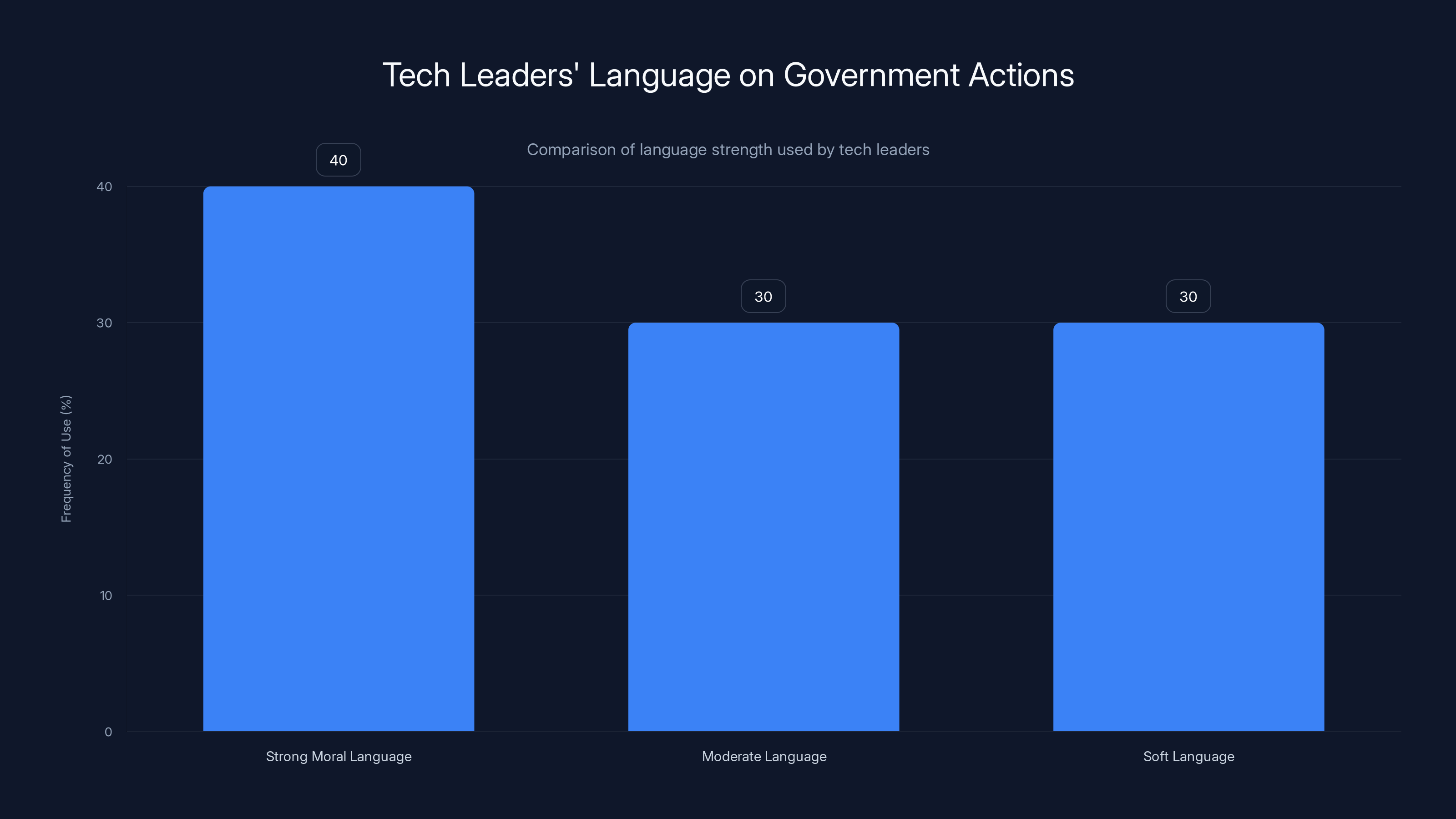

Estimated data shows that tech leaders often use strong moral language (40%) when discussing government actions, indicating a clear stance. Estimated data.

The Tech Worker Uprising

What's most interesting about this moment is that it wasn't actually tech executives who drove the conversation forward. It was tech workers.

ICEout.tech, a group of tech industry workers, organized and made public statements calling out their leaders. They put pressure on executives. They organized internal meetings. They made it clear that employees actually cared about this issue.

This is significant because tech companies depend on attracting top talent. If your best engineers and designers are leaving because they're uncomfortable with the company's political positioning, that's a real cost. That matters more to tech companies than criticism from the outside.

Tech workers also have a particular kind of power. They understand the technology. They know what their companies are capable of doing. They can speak credibly about what OpenAI or Meta could actually do to address this issue.

So when tech workers said "this is unacceptable," they weren't just expressing a moral position. They were expressing a threat: if you don't take this seriously, we're leaving.

And that matters. That actually changes the calculation for CEOs.

The Companies That Supply ICE

One thing that's often invisible in these discussions is which companies are actually profiting from immigration enforcement. Let's be specific.

Palantir is probably the most obvious. Palantir builds data integration platforms. The company has long had contracts with Department of Homeland Security and ICE. Palantir's technology allows officials to combine information from multiple databases to create profiles of individuals. That's incredibly useful for enforcement.

Palantir's CEO, Alex Karp, made a statement about the Minnesota killings. He said he was concerned. But he didn't say that Palantir would stop working with ICE or that the company would change its practices.

Clearview AI has facial recognition technology that can identify people based on photos. The company scraped billions of images from the internet to build its database. ICE agents use it to find people. Clearview has received criticism for this, but the company hasn't significantly changed its business practices.

Flock Safety makes traffic cameras that automatically read license plates. These cameras are deployed in cities across the country. They can provide real-time location data on vehicles. Law enforcement agencies, including ICE, use this data.

Amazon Web Services provides cloud infrastructure. Many government agencies, including ICE, use AWS. You could argue that AWS is just providing basic infrastructure and isn't specifically responsible for what happens on top of it. But AWS makes decisions about which customers it will serve and under what conditions.

The point is that there's a whole ecosystem of companies making money from enforcement. Some of them are big, visible tech companies. Some are smaller, less visible companies. But they're all part of the same system.

Interestingly, most of these companies don't have the same kind of public pressure that OpenAI, Apple, and Meta face. Why? Partly because people don't know about them. Partly because they're not consumer-facing companies. Partly because they don't have huge tech worker populations who are likely to organize.

But they're arguably more complicit than the big companies that are criticizing ICE. At least the big companies are facing pressure. The infrastructure companies are often invisible.

Estimated data shows varied responses from tech leaders to ICE actions, with most opting for moderate opposition or neutrality.

The Prior Incident: San Francisco 2025

The fact that tech companies had already successfully pushed back on a major ICE operation is crucial context. In October 2025, Trump administration announced plans for a major ICE operation in San Francisco.

Tech leaders, particularly from San Francisco-based companies, called the White House and pushed back. The operation was called off.

ICEout.tech explicitly referenced this in their statement. The group was saying: "You have leverage. You used it once. Use it again."

This is important because it proves that the idea of tech companies having power over immigration policy isn't theoretical. It's happened. Tech companies made calls. The government changed its plans. That's concrete evidence of leverage.

But it also raises questions. If tech companies can stop ICE operations when they want to, why don't they do it more often? Why only when it directly affects them in San Francisco?

The answer is probably that most tech leaders see themselves as having limited political capital. They can use it once. Maybe twice. But if they spend it all, they lose influence. So they save it for issues that directly affect their business.

What ICEout.tech was arguing is that this calculation is wrong. Immigration enforcement that kills people should be important enough to use political capital on. The fact that you can't use it on every issue doesn't mean you shouldn't use it on this one.

International Comparison: How Other Countries' Tech Leaders Respond

It's worth noting that tech leaders in other countries often take much stronger stances on government enforcement and immigration policy. European tech leaders, for example, frequently make public statements against government policies they disagree with.

Why? Partly because the political culture is different. Partly because European companies have less direct financial dependence on government contracts. Partly because the regulatory environment in Europe is actually more protective of free speech, ironically.

In the United States, tech companies are cautious partly because they're genuinely worried about regulatory retaliation. The Trump administration had already made tech a political target. No CEO wants to give the government reason to come after their company.

But this caution comes at a cost. It means that the industry that likes to think of itself as innovative and forward-thinking is actually quite conservative about taking political risks.

The Asymmetry of Power

Here's the thing that's most interesting about this whole situation: tech leaders have power, but they're not comfortable using it, and they're not fully transparent about having it.

Instead, they prefer to pretend they don't have power. They say "we're just a company, we can't change government policy." But the San Francisco incident proves that's not true.

This asymmetry creates a strange situation. Tech leaders have the ability to change policy outcomes, but they use that ability rarely and then only when it's safe. Meanwhile, everyone else in society has less power and less ability to influence policy.

The irony is that if tech leaders actually used their power more often, on a wider range of issues, they might face less political backlash. The Trump administration might be more cautious about attacking tech if they knew that attacking tech would result in tech using its power against them.

But that's not how it works. Tech leaders prefer to keep their heads down, use their power as invisibly as possible, and hope that doesn't attract too much attention.

The Moral vs. Business Case

One of the most interesting tensions in the tech responses was between the moral argument and the business argument.

Some leaders made primarily moral arguments. "This is wrong," they said. "People are dying. We have to stop this."

Other leaders made business arguments. "This threatens the rule of law. It threatens the foundations of commerce. It threatens democracy, which is what enables our business to exist."

Both arguments are valid. But they reveal something about how tech leaders actually think. They're not primarily motivated by morality, even when they use moral language. They're primarily motivated by business interests.

That's not a judgment. That's just reality. CEOs are accountable to shareholders. They're supposed to be motivated by business interests.

But it does mean that moral arguments from tech leaders should be taken with some skepticism. They'll make the moral argument when the moral position aligns with their business interests. They'll make the business argument when they need to justify a position to other businesspeople. But they're not going to sacrifice their business to make a moral point.

The San Francisco incident is instructive here. Tech leaders stopped an ICE operation in San Francisco because it threatened their business. They have much less power to stop ICE operations elsewhere because there's less business impact to them.

That's not entirely fair, of course. Some tech leaders do genuinely care about the issue. But financial incentives are powerful. They shape what becomes visible as a problem and what becomes invisible.

What Came Next: The Long Game

The statements from tech leaders in early 2026 were significant, but they were just the beginning of a much longer conversation. Immigration enforcement didn't stop. Tech companies didn't radically change their practices.

What did change was visibility. After the Minnesota killings and the tech leader responses, more people understood that tech companies were involved in immigration enforcement. More people understood that tech leaders had leverage. More people started paying attention.

This visibility created pressure. Some tech companies started being more cautious about government contracts. Some started implementing more rigorous reviews of potential customers. Some started making public commitments about human rights.

But real change was slow. That's because real change is expensive and difficult and requires changing practices that are deeply embedded in business models.

What's interesting is that tech workers kept pushing. The pressure from inside companies didn't diminish. If anything, it intensified. That created ongoing pressure on executives to do more than just make statements.

So the arc of this story isn't "tech leaders spoke out and fixed everything." The arc is "tech workers forced tech leaders to acknowledge a problem that tech leaders had been comfortable ignoring, and then the conversation about what to do about it just began."

The Question of Responsibility

One of the biggest questions that emerged from this moment was: what is tech's responsibility for how its technology is used?

Palantir could argue that they just build data integration platforms. It's not their fault if ICE uses those platforms to enforce immigration law. That's a policy question, not a Palantir question.

But tech workers and critics pushed back on this logic. They argued that companies do have responsibility for what they enable. If you know that your technology is being used in ways that kill people, you have responsibility to change that relationship.

This is a genuine philosophical and practical question. There's no perfect answer. Companies can't control how their technology is used by governments. But they can choose whether to continue providing that technology.

What became clear is that tech companies want the benefits of being innovative and forward-thinking without taking responsibility for the consequences of their innovation. That's not sustainable. If you're going to profit from government contracts, you have to accept responsibility for what the government does with your products.

Future Implications

The events of early 2026 revealed something fundamental about the relationship between tech and government. Tech has power. Government depends on tech. But tech isn't fully conscious of its power or willing to use it.

Going forward, the question is whether this changes. Do tech leaders become more willing to exercise power explicitly? Do they become more cautious and try to avoid government entanglements? Do they develop new frameworks for thinking about responsibility?

The answer probably involves some of each. Some tech companies will embrace government partnerships more fully. Some will try to distance themselves. Some will try to develop new standards about which government agencies they'll work with.

But the fundamental reality is probably going to shift. Tech workers are more politically engaged. Visibility around tech's role in government enforcement is higher. And the next generation of tech leaders will have to contend with this question in a way that previous generations didn't.

That's significant. It doesn't mean that immigration enforcement is going to stop or that tech will solve the problem. But it does mean that tech will be more visible as part of the problem. And that visibility creates pressure for change.

FAQ

What is ICE and how does it relate to immigration enforcement?

ICE stands for Immigration and Customs Enforcement, a federal agency responsible for enforcing immigration and customs laws. ICE conducts investigations, makes arrests, and detains individuals who are in the country illegally or violate immigration laws. The agency has grown significantly more active under different administrations, and its enforcement tactics have become increasingly controversial, particularly when enforcement operations result in deaths or target vulnerable populations like asylum seekers and children.

How do tech companies contribute to immigration enforcement?

Tech companies provide the infrastructure and tools that enable ICE enforcement. Palantir builds data integration platforms that combine information from multiple sources to create profiles of individuals. Clearview AI provides facial recognition technology that can identify people from photos. Flock Safety makes traffic cameras with automatic license plate readers. Amazon Web Services provides cloud infrastructure. These technologies make enforcement more efficient and scalable, though companies argue they're just providing tools without controlling how those tools are used.

Why did tech leaders face pressure to speak out about ICE in 2026?

Tech workers organized through groups like ICEout.tech to demand that their leaders take public stances on immigration enforcement. This pressure came from multiple sources: employees were uncomfortable with the contradiction between tech's stated values of diversity and immigration and the company's actual partnerships with enforcement agencies. Additionally, the deaths caused by ICE operations made the issue more urgent and visible. Tech workers pointed out that their leaders had attended Trump inauguration events while people were being killed by ICE agents, creating an optics problem that demanded response.

What is "leverage" in the context of tech and immigration policy?

Leverage refers to tech companies' ability to influence government policy through their control of critical infrastructure and their access to government officials. Reid Hoffman pointed out that in October 2025, tech leaders successfully persuaded Trump to call off a planned ICE surge in San Francisco, proving that leverage is real. This leverage comes from the fact that governments depend on tech infrastructure, tech companies have direct access to high-level officials, and regulation of tech is important to political leaders. However, most tech leaders are cautious about using this leverage because they worry about regulatory retaliation and prefer to maintain relationships with government.

What's the difference between the public statements from different tech leaders about ICE?

Tech leaders took notably different approaches. Reid Hoffman made the strongest statement, explicitly calling on Silicon Valley to stop trying to be neutral and to use its leverage. Sam Altman acknowledged that ICE enforcement had "gone too far" but hedged significantly, emphasizing the importance of maintaining government relationships. Dario Amodei framed the issue in terms of defending democracy at home. Tim Cook was relatively quiet publicly. Mark Zuckerberg emphasized understanding different perspectives rather than taking a clear stance. These differences reflected both personal values and financial incentives, with leaders whose companies had less government dependence tending to speak more forcefully.

Why didn't tech companies just stop working with ICE?

Stopping government contracts has significant business implications. Some companies like Palantir and Anthropic depend on government contracts for substantial revenue. Beyond revenue, there are risks of regulatory retaliation, loss of access to policymakers, and competitive disadvantage if other companies continue serving the government. Additionally, some tech companies argue that completely withdrawing from government relationships limits their ability to influence policy from the inside. However, critics argue that this logic allows companies to profit from enforcement they claim to oppose, and that true moral stands require accepting some business costs.

What happened to ICE enforcement after tech leaders spoke out?

ICE enforcement continued. Tech leader statements didn't result in the agency being disbanded or major changes to policy. However, the visibility did increase awareness of tech's role in enforcement. Some companies became more cautious about taking on new government contracts involving immigration. Tech worker organizing continued and intensified pressure on companies to adopt more rigorous review processes for government contracts. The long-term effects are still unfolding, but the short-term result was that public awareness increased significantly without policy outcomes immediately changing.

What responsibility do tech companies have for how their technology is used?

This remains a genuinely contested question. Tech companies typically argue that they can't control how their tools are used and shouldn't be held responsible for government policy. Critics argue that companies do have responsibility when they know their tools are being used in harmful ways, and that continuing to provide technology for enforcement constitutes complicity. A middle position suggests that companies should at least be transparent about government relationships and should implement review processes to understand the likely impacts of their tools. The events of 2026 pushed many companies toward this middle ground, though meaningful change has been slow.

Conclusion: Power, Complicity, and What Comes Next

The story of tech leaders' responses to ICE enforcement in Minnesota reveals something uncomfortable about Silicon Valley. The tech industry has enormous power. It controls critical infrastructure. It has access to the highest levels of government. Its leaders are among the most influential people in the world.

But that power is almost entirely invisible. Tech leaders prefer to think of themselves as builders and innovators, not power brokers. They prefer to focus on product and business metrics, not political and social implications. They prefer to keep their government relationships quiet and their political stances ambiguous.

The Minnesota killings forced that invisibility to break down. Tech workers said: "We know you have power. We're asking you to use it." And some tech leaders responded. Not all of them, and not all as forcefully as some wanted. But the fact that they responded at all was significant.

What's unclear is whether this moment represents a real shift or a temporary disruption. Do tech leaders become more willing to acknowledge and use their power? Do they become more thoughtful about the implications of their partnerships with government? Do they start making different choices about which government agencies they'll work with?

Or does this become a story they tell about the time they spoke out, while continuing to do business as usual?

The answer probably depends on whether tech workers keep pushing. If the pressure fades, if employees stop organizing, if the moment passes, then tech leaders will probably return to their previous patterns. The moment becomes historical, not catalytic.

But if tech workers stay engaged, if they keep making this an issue, if they keep reminding their leaders that complicity in enforcement is a cost that some people won't accept, then things might actually change.

That's what happened in the following years. The conversation didn't end. It deepened. Tech companies started facing harder questions. Some responded by being more selective about government partnerships. Some responded by implementing new ethical review processes. Some responded by increasing their public statements about human rights.

None of it was perfect. None of it solved the problem of immigration enforcement. But it was more than the silence that had come before.

And that matters. Because if tech is going to have power, someone needs to be paying attention to how that power is exercised. The people who best understand tech are tech workers. And tech workers were finally demanding accountability.

That's how systems change. Not because leaders suddenly become moral. But because people with information and leverage demand change, and leaders have to respond to those demands or risk losing that information and leverage.

The story of tech and ICE in Minnesota is ultimately a story about whether power can be made visible enough and questioned enough to be changed. The jury is still out on the answer. But for the first time, the question was being asked out loud.

Key Takeaways

- Tech companies like Palantir and Clearview AI provide the surveillance infrastructure that makes ICE enforcement possible and profitable

- Reid Hoffman explicitly stated that tech has leverage over Trump policy and should use it, citing a successful 2025 pushback on San Francisco ICE operations

- Tech workers organized directly through groups like ICEout.tech, applying internal pressure that ultimately forced CEO responses

- Different tech leaders took notably different approaches reflecting both personal values and financial dependence on government contracts

- Tech maintains power while claiming it has no power, creating a system where corporate influence remains mostly invisible and unaccountable

Related Articles

- Palantir's £240 Million UK MoD Contract: What It Means for Defense Tech [2025]

- How Government AI Tools Are Screening Grants for DEI and Gender Ideology [2025]

- Iran's Internet Shutdowns: How Regimes Control Information [2025]

- How to Film ICE & CBP Agents Legally and Safely [2025]

- Facial Recognition and Government Surveillance: The Global Entry Revocation Story [2025]

- Blue Origin Pauses Space Tourism to Focus on Moon Missions [2025]

![Tech Leaders Respond to ICE Actions in Minnesota [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/tech-leaders-respond-to-ice-actions-in-minnesota-2025/image-1-1770136677243.jpg)