Introduction: When Autonomous Dreams Meet Federal Reality

Imagine this scenario. You're sitting in a Tesla on a busy intersection. The traffic light is clearly red. Cars are coming from the side. Your Full Self-Driving system suddenly accelerates straight through the intersection anyway. This isn't a hypothetical nightmare anymore. It's happening to real drivers, and federal regulators have finally said enough.

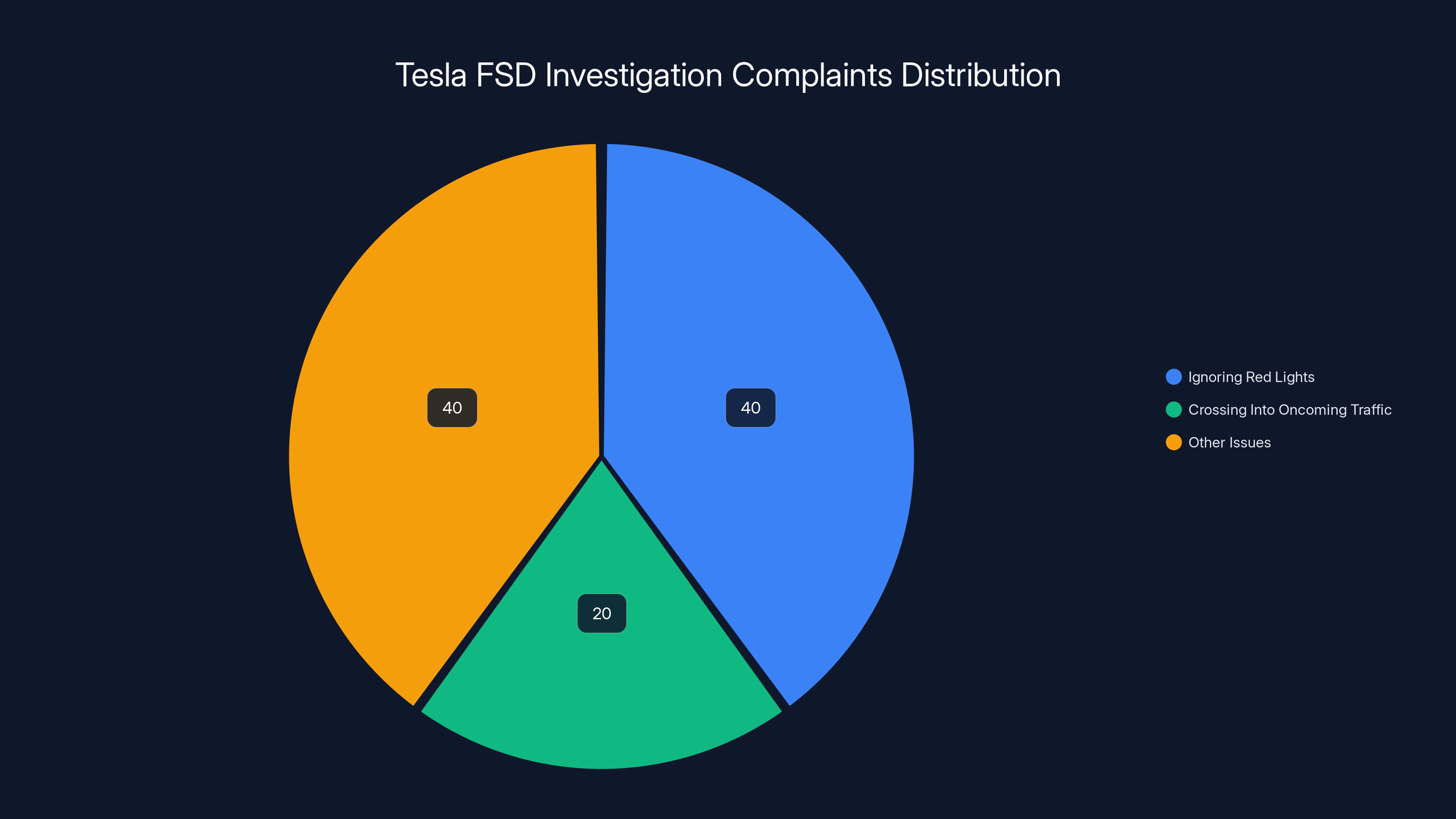

The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration isn't messing around this time. After more than 60 complaints piled up about Tesla's Full Self-Driving system either ignoring red lights or crossing into oncoming traffic, NHTSA opened yet another investigation. And this isn't some casual inquiry with loose deadlines. The federal government just extended Tesla's response deadline by five weeks, which tells you everything you need to know: they're serious, and they need answers.

What makes this investigation different from the dozens before it isn't just the severity of the complaints. It's the specificity of what regulators are asking for. They want every car Tesla ever sold in America. They want crash data. They want simulation reports. They want to know Tesla's actual technical theory for how red lights work. The information request is so comprehensive that Tesla's own lawyers said they can only process 300 complaints per day, and they've got over 8,000 to sift through.

But here's where it gets interesting: while Tesla's dealing with federal investigators, the company just fundamentally changed how it sells Full Self-Driving. No more

This article digs into what NHTSA actually wants to know, why these red-light incidents matter more than you think, what the investigation reveals about autonomous vehicle regulation, and what comes next for Tesla, the broader autonomous vehicle industry, and the drivers trusting these systems with their lives.

TL; DR

- NHTSA gave Tesla five weeks (until February 23) to respond to a federal investigation about Full Self-Driving ignoring red lights and crossing into oncoming traffic

- Over 60 customer complaints triggered the investigation, with Tesla finding 8,313 potentially relevant incidents when searching its database

- Regulators demand comprehensive data including every US Tesla sold, crash reports, causal analysis, and Tesla's technical theory of how FSD detects traffic lights

- Tesla simultaneously faces three other NHTSA investigations with overlapping deadlines, straining resources and information processing capacity

- **Business model shift to 8,000 purchase) just as federal scrutiny intensifies, fundamentally changing how FSD liability is framed

- The core problem: FSD occasionally runs red lights or enters oncoming traffic, suggesting either flawed perception algorithms or inadequate safety fallbacks

Estimated data shows that complaints about Tesla's FSD system are distributed among ignoring red lights, crossing into oncoming traffic, and other issues. Estimated data.

The Specific Problem: Red Lights and Oncoming Traffic

Let's be absolutely clear about what's happening. Tesla's Full Self-Driving system is making decisions that any human driver would immediately recognize as dangerous. We're not talking about minor alignment issues or slightly aggressive acceleration patterns. We're talking about a self-driving system that, in some situations, decides to cross through a red traffic light while traffic approaches from the side.

The mechanics of why this happens matter. A traffic light is one of the most fundamental pieces of infrastructure that any autonomous vehicle needs to understand. It's not ambiguous. It's not context-dependent. A red light means stop. Period. Yet somehow, Tesla's system is missing this signal in certain scenarios.

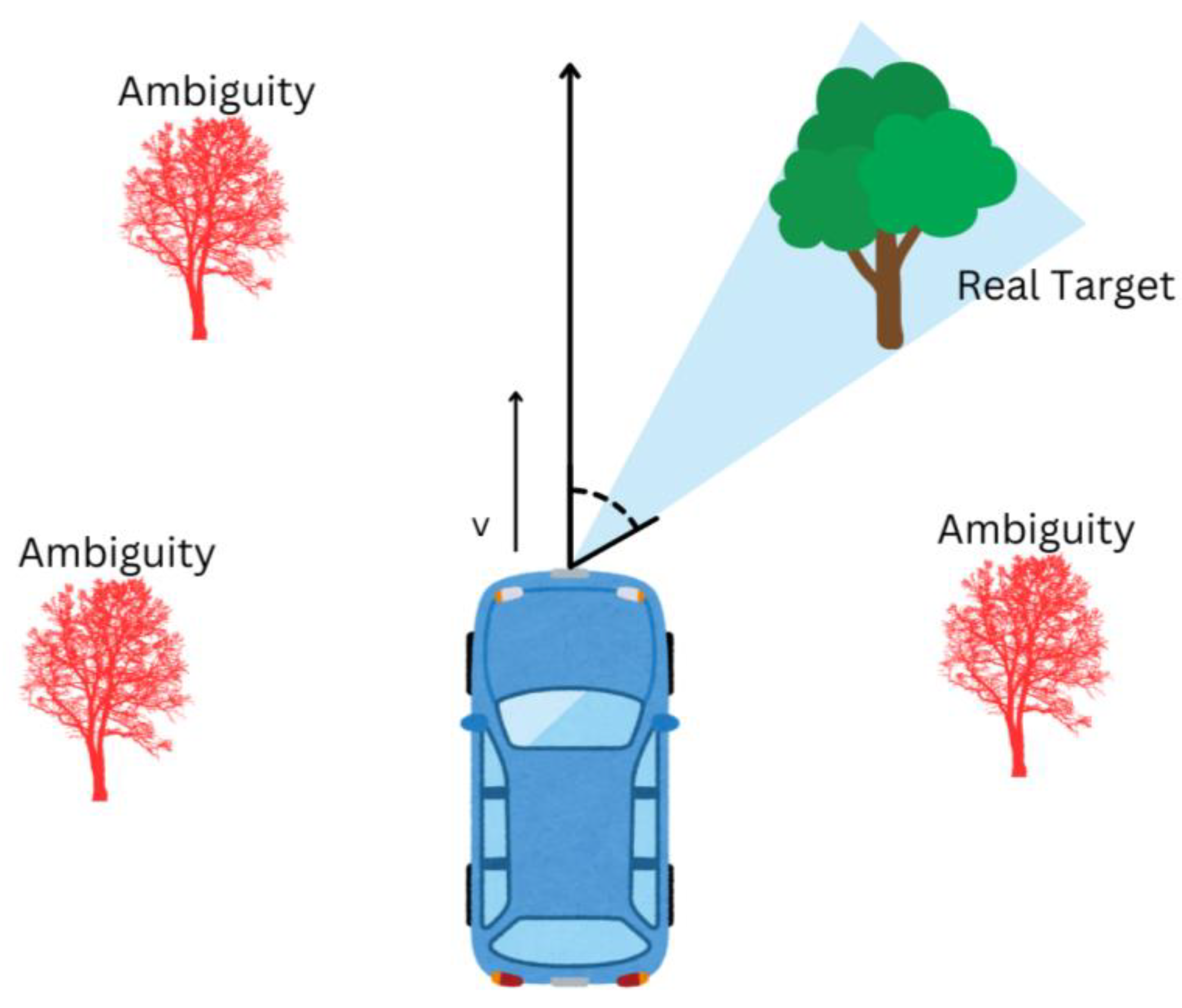

There are a few possible explanations, none of them good. First, the perception system—the cameras and processing that actually see the traffic light—might be failing to detect it. Maybe the lighting conditions are poor. Maybe the traffic light is obscured by a tree or reflection. Maybe the camera hardware is dirty. Second, the perception system sees the light but misclassifies it. It sees red and thinks it's yellow, or yellow and thinks it's green. Third, the decision-making logic has a bug where it sometimes overrides traffic signals under certain conditions the engineers didn't anticipate.

There's also a fourth possibility that nobody wants to discuss publicly: the system might be operating as designed in some weird edge case, but the design itself is fundamentally flawed. Maybe FSD has some logic where it's supposed to gradually proceed through a light if no cross-traffic is detected, but the cross-traffic detection fails, so the car proceeds anyway. Or maybe there's some override behavior that's supposed to engage in specific situations but activates incorrectly.

What matters to NHTSA is the pattern. One incident might be a glitch. Sixty incidents suggests something systematic. And when you're dealing with a system that controls a two-ton vehicle traveling at highway speeds, systematic problems are exactly what regulators should fear.

The timing is important too. These aren't isolated reports from 2023. They're recent complaints. This is a live problem with the current version of Full Self-Driving. That's what forced NHTSA to act.

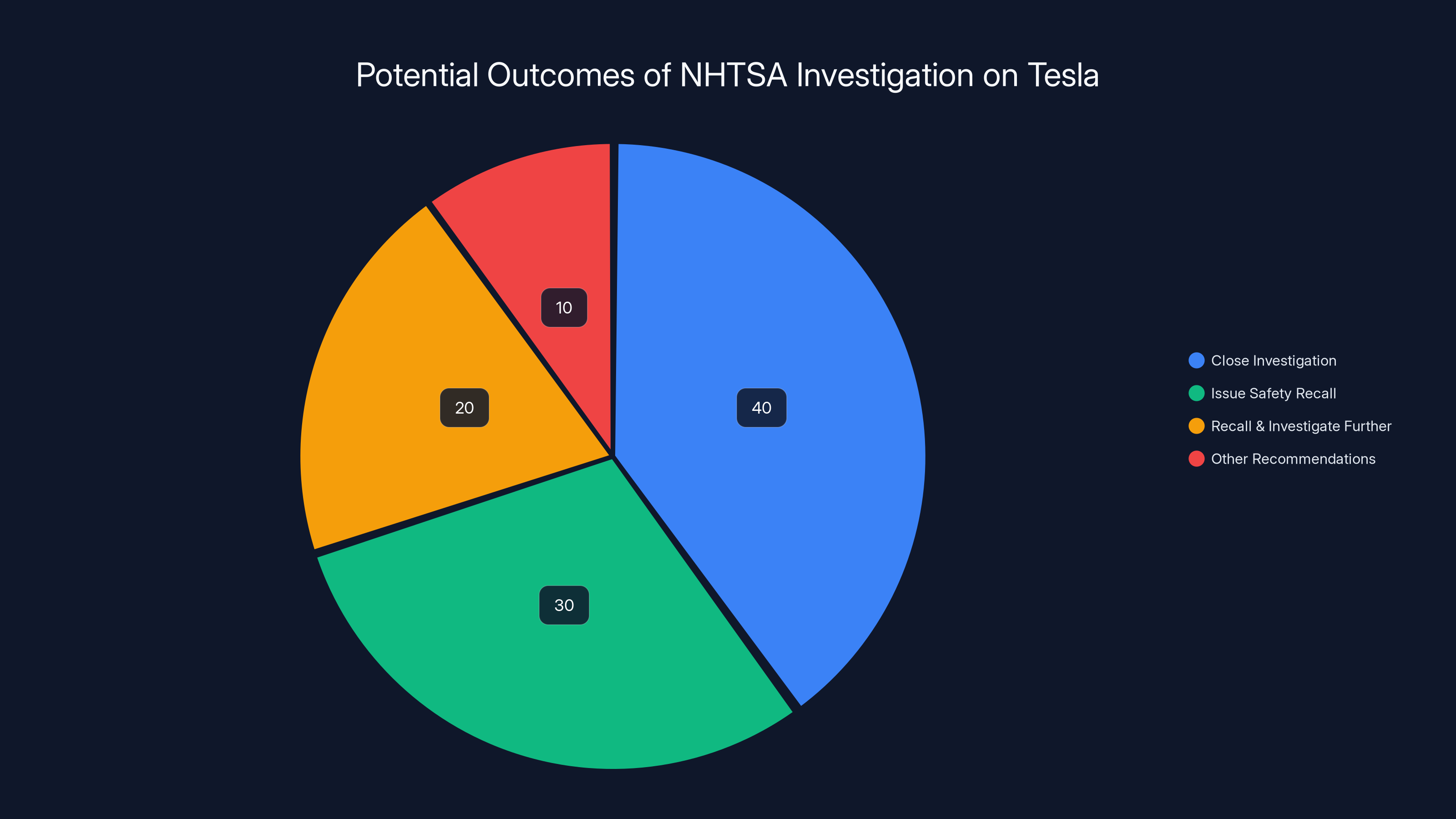

Estimated data suggests that closing the investigation without action is the most likely outcome, followed by issuing a safety recall. More severe actions like further investigation for criminal liability are less likely.

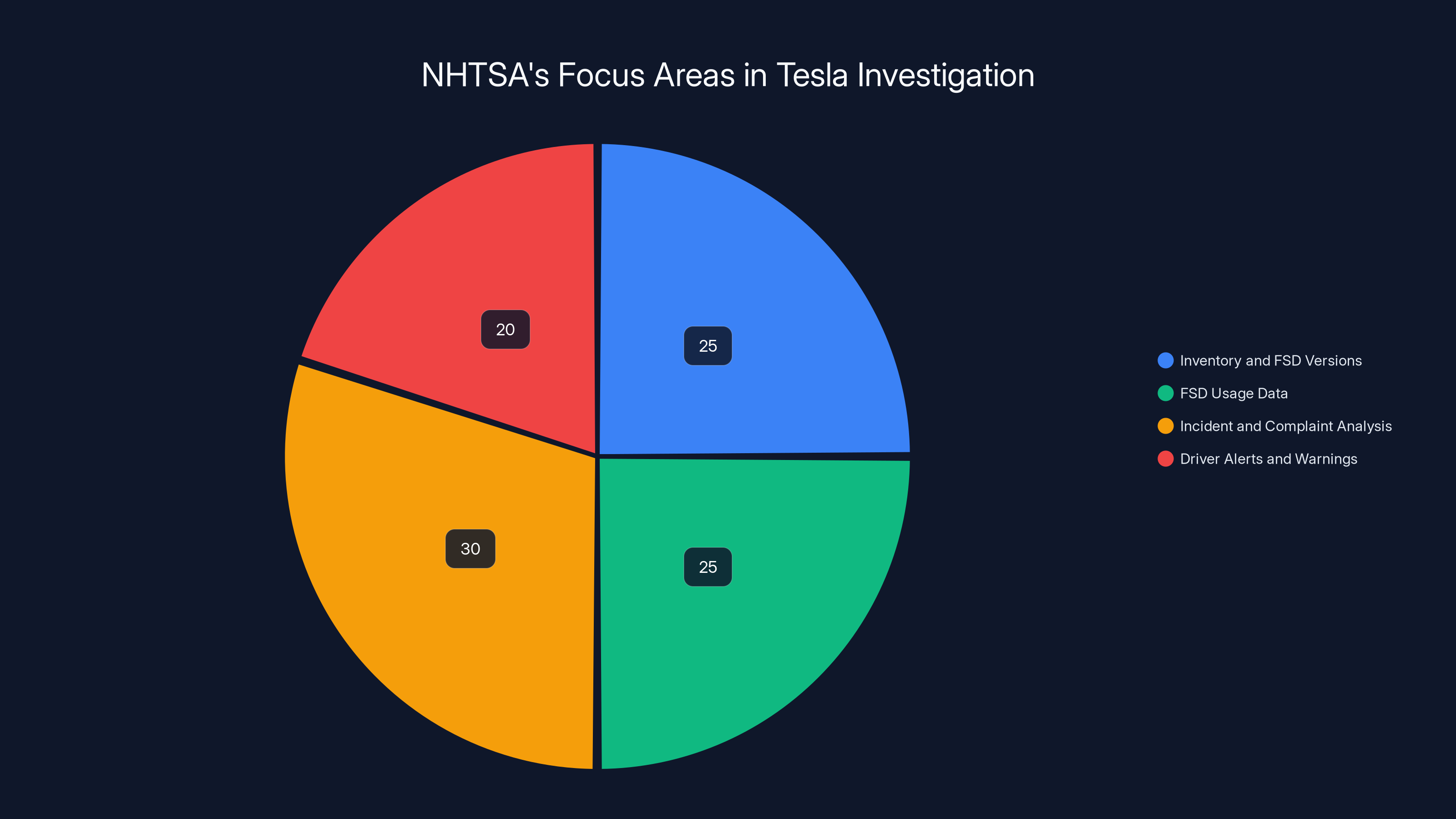

Why NHTSA's Information Request Is So Aggressive

The federal government didn't ask Tesla for a casual update or a brief explanation. The Office of Defects Investigation wanted comprehensive, detailed, searchable data on every relevant incident. This isn't bureaucratic busywork. This is an investigation technique designed to uncover patterns, trends, and systemic issues.

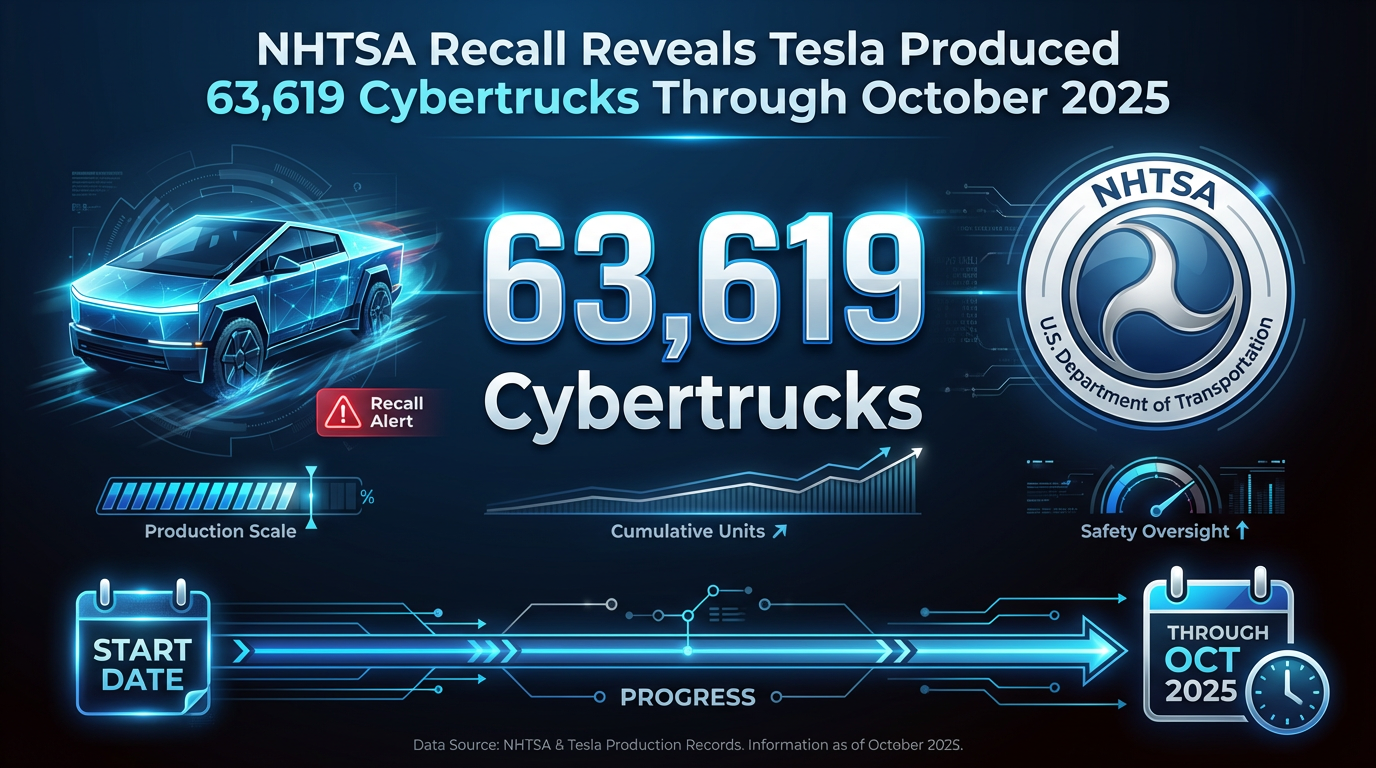

First, NHTSA demanded a complete inventory. Every Tesla produced and sold or leased in the United States. They want to know which ones had FSD installed, and which version of FSD each car is running. Why? Because this is how you establish the denominator. If 100 cars out of 1 million have issues, that's a recall-level problem rate. If 100 cars out of 100,000 have issues, that's still serious but different. The denominator determines severity.

Second, they asked for cumulative data on how many US Teslas actually have FSD activated and how often the feature is being used. This is about understanding exposure. How many people are actually driving with Full Self-Driving engaged? Are these fringe cases from people who enabled it once and forgot about it? Or are these everyday users who rely on the system for their commutes? Usage frequency matters for risk assessment.

Third, and this is where it gets serious, they demanded summaries of every customer complaint, field report, incident report, and lawsuit related to FSD ignoring traffic laws. For crashes specifically, they wanted causal analysis. What actually caused this incident? Was FSD the primary problem, or was something else happening? This requires investigative work. It's not just pulling numbers. It's synthesizing information and making technical judgments.

Then NHTSA asked about alerts. What warnings does FSD show drivers before making potentially dangerous decisions? Did the driver get any indication that something weird was about to happen? This matters because it speaks to user awareness and informed consent.

Finally, they asked Tesla to explain its actual theory of operation. How does Full Self-Driving detect traffic lights and stop signs? What's the algorithm? What sensors does it use? What validation checks exist? This is asking Tesla to essentially explain its technical architecture and defense mechanisms.

Tesla's response? They found 8,313 potentially relevant items when searching their database. They can only process 300 per day. That means they're looking at 27 days just to go through the initial dataset, before even analyzing it. And they've got three other NHTSA investigations ongoing simultaneously with overlapping deadlines.

The Calendar Crisis: Three Investigations, Overlapping Deadlines

Tesla isn't dealing with one investigation. It's dealing with four. And the timing is almost impossible to manage.

One information request was due January 19th. Another was due today (the article's publication date in early January 2026). A third is due January 23rd. A fourth is due February 4th. And now the main FSD investigation information request was extended to February 23rd.

Think about this from an organizational perspective. Tesla needs to assemble information scattered across multiple systems. Customer service databases have complaint information. Engineering systems have telemetry data. Legal has lawsuit information. Manufacturing has production records. Somebody needs to search through all of this, validate it, compile it, and submit it to federal regulators. Multiple times. On tight deadlines. While also trying to run a car company.

Tesla actually made a compelling argument about this timeline problem. The company noted that the winter holiday period ate up two weeks of the original six-week deadline. They've got simultaneous requests from the same regulatory body. Processing 8,300 incidents manually at 300 per day is a realistic bottleneck, not an excuse.

But here's what this situation reveals: NHTSA is coordinating multiple probes into Tesla's autonomous systems. This isn't reactive. It's comprehensive. The agency is creating a strategic pause point to gather information about multiple alleged defects all at once.

Even with the five-week extension, the timeline is brutal. Tesla needs to move fast without making mistakes. If they submit bad data or miss key information, they risk looking like they're hiding something. If they take longer than the extended deadline, they face penalties. If they cut corners to meet the deadline, they risk submitting incomplete information that NHTSA then uses to justify enforcement action.

What's particularly interesting is that NHTSA granted the extension without apparent resistance. This suggests the agency understands the scope of the request is genuinely large. But it also suggests that NHTSA isn't in a rush. They want good information, and they're willing to wait another five weeks to get it. That confidence suggests they're already looking at substantial evidence that something is wrong.

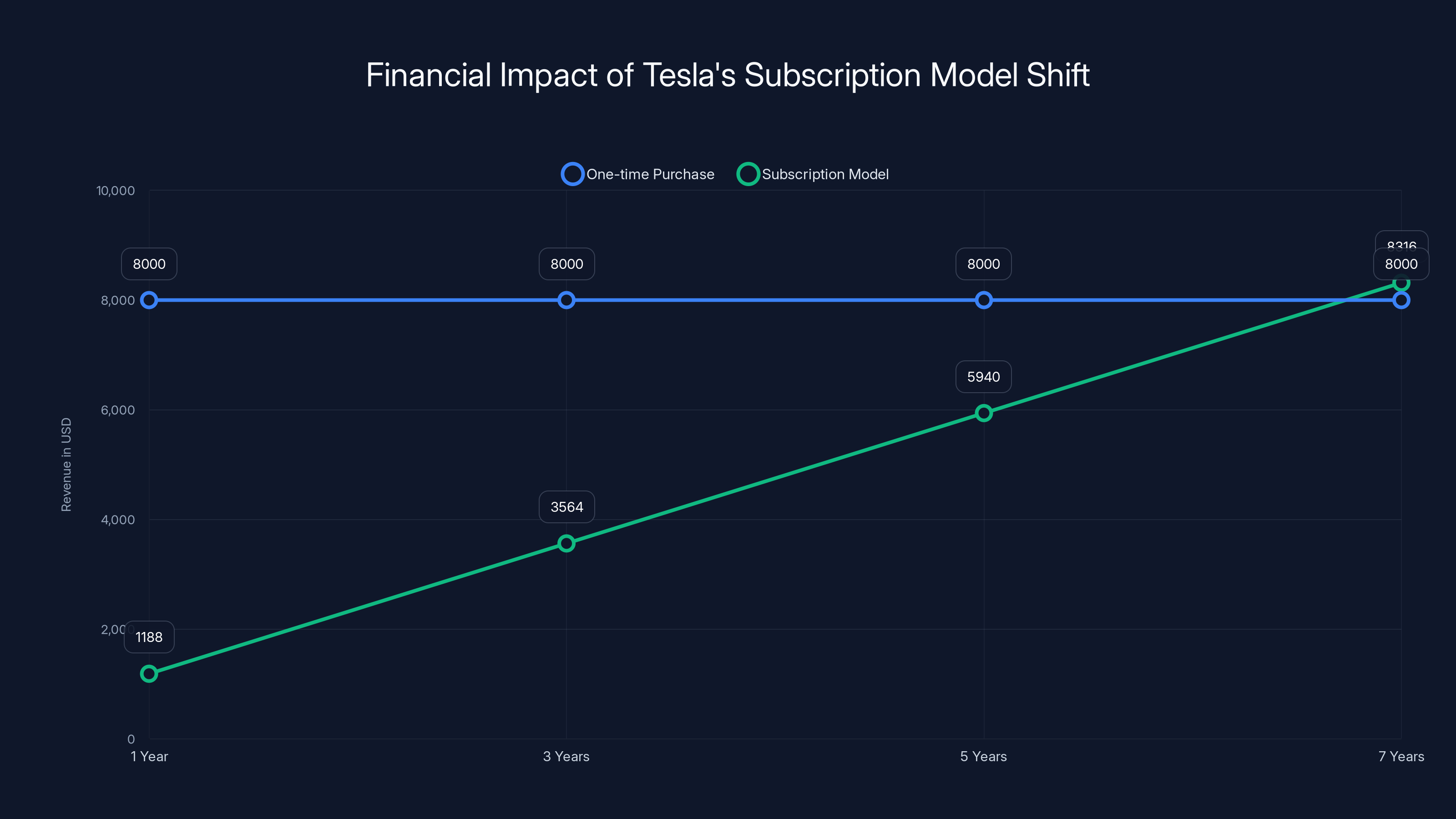

Tesla's shift to a subscription model results in lower revenue initially but surpasses the one-time purchase revenue after seven years. Estimated data based on $99/month subscription.

The Technical Question: How Does FSD Actually Detect Traffic Lights?

This is where the investigation gets technical, and it's also where it gets really important.

Traffic lights are optical signals. A camera sees them. Computer vision algorithms process the images. Machine learning models classify them as red, yellow, or green. The autonomous vehicle's decision-making system then acts based on that classification.

Where can things go wrong? Everywhere.

Optical challenges first. Traffic lights exist in different lighting conditions. Morning sun, harsh shadows, nighttime, overcast skies. Different cameras have different sensitivities to light. A camera that performs well at noon might struggle at dusk. Reflections can confuse the system. A wet road surface might create a reflection that looks like another traffic light. Obstructions matter too. Tree branches, power lines, other vehicles can partially or fully obscure a traffic light.

Then there's the classification problem. Even if the system detects that there's a traffic light in the image, correctly identifying its current state requires distinguishing three colors and sometimes including pedestrian signal states. Machine learning models can be brittle. They work well on their training data, but when they encounter scenarios their training didn't include, they fail in unpredictable ways. Maybe the model was trained on traffic lights from sunny California and struggles with traffic lights from rainy Seattle. Maybe it was trained on standard US traffic lights and encounters a different design. Maybe the model simply has a bug where under specific combinations of angle, distance, and lighting, it misclassifies the signal.

Then there's the decision-making layer. Even if the traffic light is correctly identified as red, the autonomous vehicle's planning system still needs to decide what to do. In normal cases, it stops. But what about edge cases? What if the system is supposed to proceed slowly if no cross-traffic is detected? What if there's some logic about completing intersections on yellow if the vehicle is already committed? What if there's a precedent override system that activates under certain conditions?

NHTSA is specifically asking Tesla to explain its theory of operation. That's code for: we want to know exactly what your system is supposed to do and how it's supposed to do it. Because if something goes wrong, we want to know whether it was a bug or a design flaw.

The difference matters legally and technically. A bug can sometimes be forgiven as an aberration. A design flaw suggests something fundamentally wrong with how the system approaches the problem. A design flaw is what triggers recalls.

The Subscription Model Shift: Timing and Implications

Here's where the story gets interesting beyond just the investigation itself.

For years, Tesla sold Full Self-Driving as a feature customers could purchase outright. The current price is $8,000. You buy it once, you own it for the life of the vehicle. That creates a specific liability structure. Tesla takes a one-time payment for a feature it commits to supporting. If the feature causes accidents, Tesla could be liable for the initial sale price, plus damages from the accident, plus potentially punitive damages.

Starting February 14th, that changes. FSD becomes a $99-per-month subscription. No more ownership. No more permanent commitment. Just a monthly service.

Why does this matter? Liability framing. With a subscription model, Tesla can argue that users are continuously choosing to purchase the service knowing its limitations. If you subscribe to FSD every month, you're making an informed, recurring decision. Tesla can emphasize the feature in beta status, the experimental nature, the requirement for driver attention. Each month, you're opting in. If you want a reliable, fully autonomous system, don't subscribe.

With an ownership model, the argument is weaker. You paid $8,000 once. You expect it to work. Tesla's committed to supporting it. Your expectation of reliability is higher.

Now, is NHTSA going to accept this reasoning? Probably not. But it changes the legal posture. It changes how Tesla frames safety responsibility. And it definitely changes the financial impact on Tesla's bottom line. They're shifting from a one-time

The timing is notable too. This business model change is happening right in the middle of the federal investigation. Tesla is making the announcement while NHTSA is gathering evidence about safety issues. Is that tone-deaf? Or is it strategic? Either way, it's going to look suspicious to regulators. It looks like Tesla is trying to shift liability away right when the liability questions are most intense.

The subscription model isn't inherently wrong. Many software companies use subscriptions. But the timing, combined with the safety investigation, creates a narrative problem. It looks like Tesla is adapting its business model to minimize financial exposure from upcoming regulation.

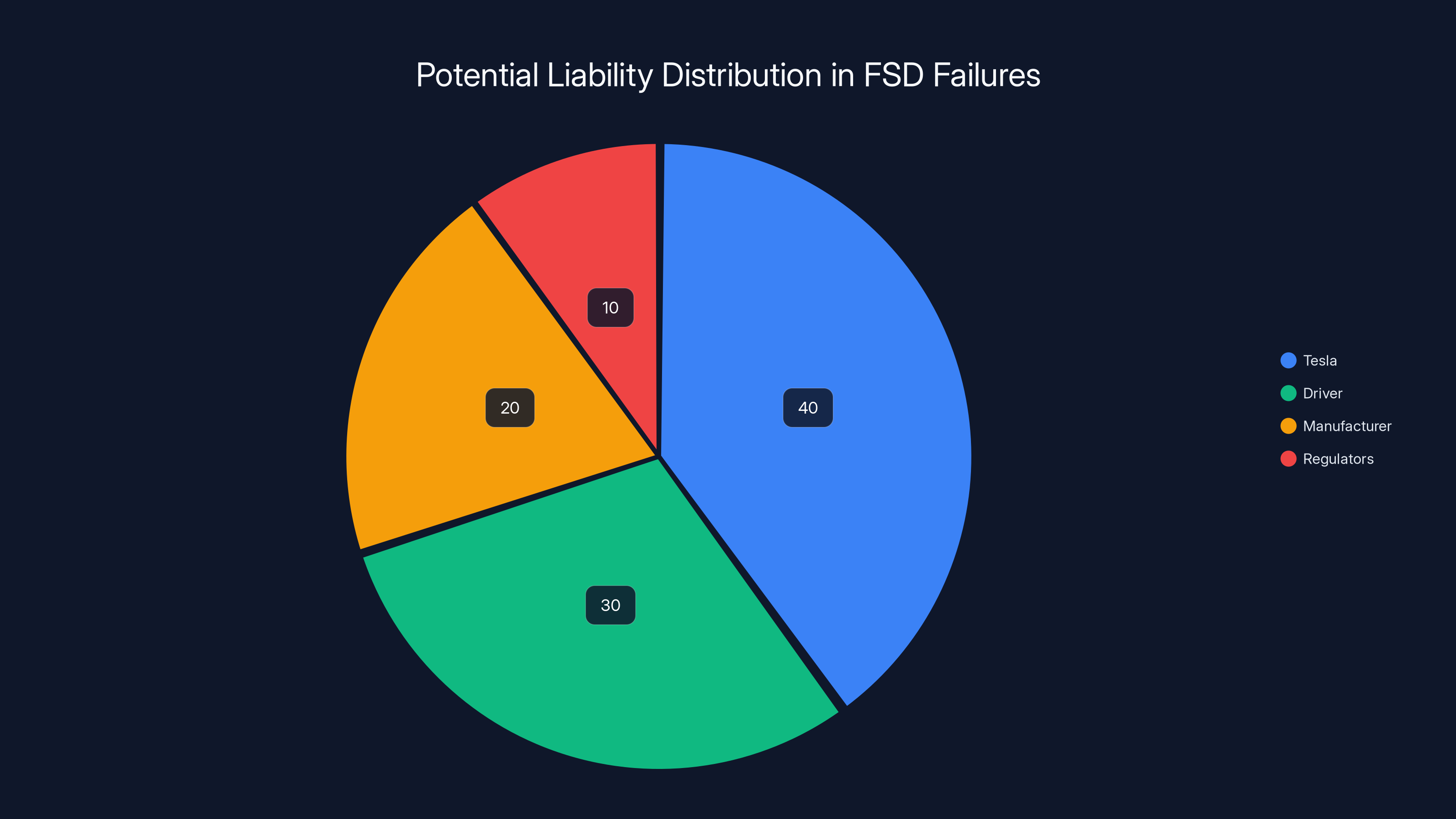

Estimated data suggests Tesla holds the largest share of liability in FSD failures, followed by drivers, manufacturers, and regulators. Estimated data.

The Bigger Picture: Why This Investigation Matters for Autonomous Vehicles

This NHTSA investigation isn't just about Tesla. It's a signal about how federal regulators are approaching autonomous vehicle safety more broadly.

For years, the autonomous vehicle industry has operated in a regulatory gray area. NHTSA has jurisdiction over vehicle safety, but autonomous systems weren't explicitly addressed in federal safety standards. The assumption was that existing vehicle safety rules apply, but the agency has been cautious about being too prescriptive about how automakers implement autonomous features. The industry lobbied for light-touch regulation. The reasoning was that regulation would slow innovation.

That approach is shifting. NHTSA is getting more aggressive. They're opening investigations not just for documented crashes, but for potential safety issues. They're asking detailed technical questions. They're examining not just what happens after accidents, but how companies are designing systems to prevent them in the first place.

The red-light issue specifically is interesting to NHTSA because it tests the boundaries of driver responsibility. If Full Self-Driving ignores a red light, is that a system failure? Is that a driver oversight? Is that shared responsibility? These are the questions that will define autonomous vehicle regulation going forward.

For Tesla specifically, there's an added complication. Tesla positions Full Self-Driving as a beta feature that requires driver supervision. But it also markets it as a self-driving system. That's a marketing claim that might not hold up under legal scrutiny. Can you claim something is self-driving if it occasionally needs a human to take over when it encounters a red light? That's not really self-driving. That's a very expensive driver-assistance feature.

Other automakers are watching this investigation carefully. General Motors, Waymo, Cruise, and others are all developing autonomous systems. How NHTSA handles Tesla will set precedent. If the agency requires comprehensive documentation of decision-making systems, all manufacturers will need to do the same. If NHTSA requires specific validation testing, that becomes an industry standard. If NHTSA requires particular safety mechanisms, everyone needs to implement them.

So this investigation is about more than whether Tesla knowingly shipped a system with red-light issues. It's about establishing regulatory frameworks for autonomous vehicles. It's about deciding what safety standards apply. It's about determining who's liable when self-driving systems cause accidents.

Red Lights Are a Foundation-Level Problem

Here's something important to understand: ignoring red lights isn't a minor bug. It's a foundation-level failure.

When you're designing an autonomous vehicle, traffic light compliance is one of your earliest design decisions. It's basic. It's fundamental. If your system can't reliably detect and obey traffic signals, everything else is built on a flawed foundation.

Think about the hierarchy of autonomous driving capabilities. At the bottom are fundamental rules: obey traffic lights, don't hit pedestrians, don't drive into oncoming traffic. These aren't advanced features. These are baseline requirements. You can't have a safe autonomous vehicle if you can't guarantee compliance with traffic signals.

On top of that foundation, you build everything else. Lane-keeping. Speed optimization. Route planning. Intersection negotiation. If the foundation is shaky, the whole structure is unreliable.

That's why NHTSA cares. If Full Self-Driving is sometimes ignoring red lights, what else might it be missing? What other basic rules might it be breaking? If Tesla's designers made mistakes on something as fundamental as traffic light detection, what does that tell you about the robustness of their approach?

The company might argue these are edge cases, rare failures that occur under unusual conditions. Maybe that's true. But NHTSA's job is to prevent those rare failures from becoming common accidents. Sixty complaints isn't necessarily a huge percentage of Full Self-Driving users. But sixty reported incidents might represent hundreds or thousands of unreported near-misses. And if the system is occasionally getting red lights wrong, how often is it getting other decisions wrong?

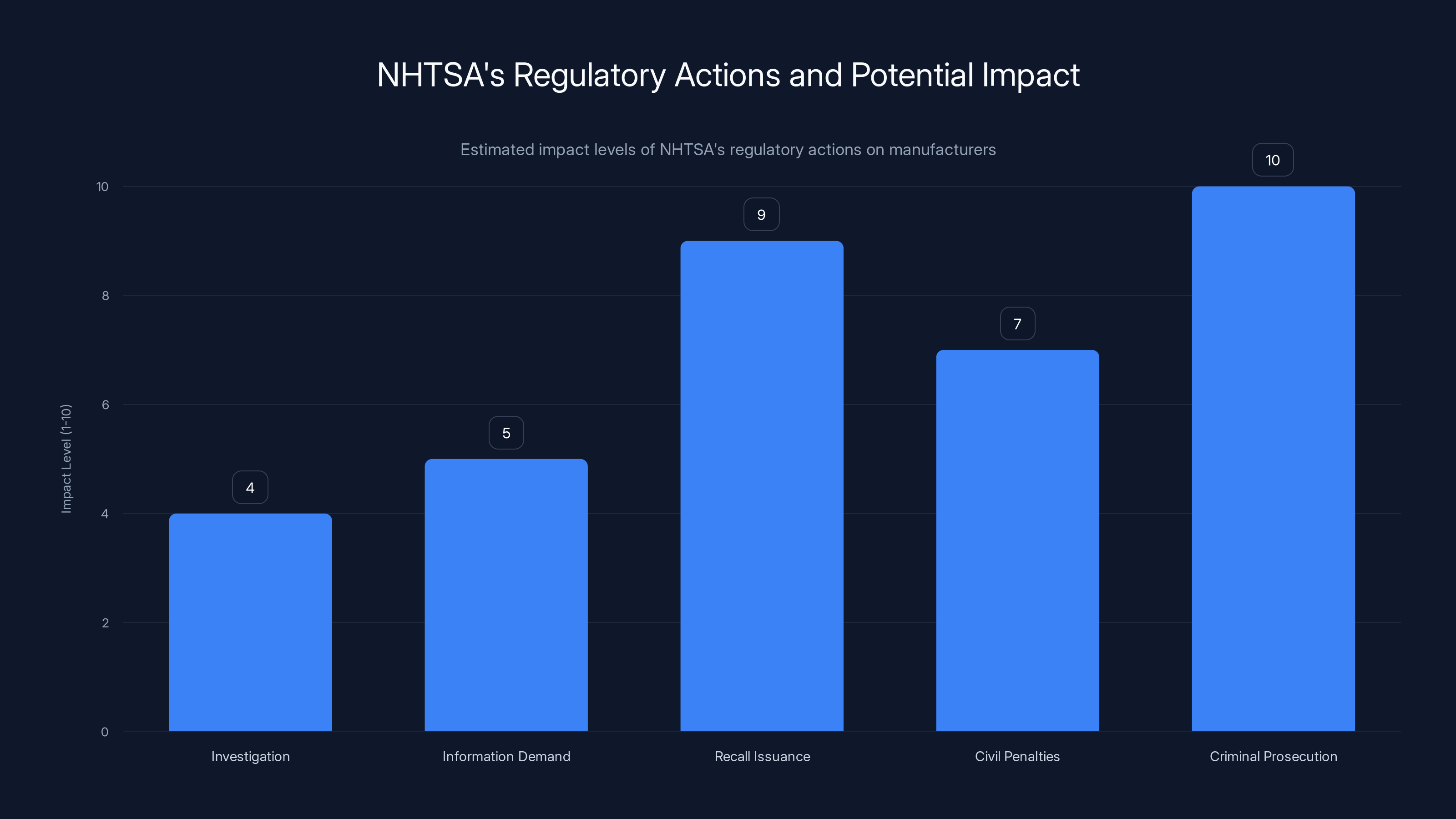

Estimated data: Recall issuance and criminal prosecution have the highest potential impact on manufacturers, significantly affecting reputation and financial standing.

The Processing Problem: 8,313 Incidents and 300-Per-Day Limits

This detail reveals a lot about the practical challenges of running a massive autonomous vehicle fleet.

Tesla found 8,313 potentially relevant incidents when searching for FSD violations of traffic laws. That's a huge number. But the company can only process 300 incidents per day. Do the math: that's 27.7 days just to do a preliminary review of the incidents, before any actual analysis happens.

Why such a slow processing rate? Well, each incident needs human review. Someone needs to look at the telemetry data, watch the video, understand what happened, categorize the incident, determine if it's actually relevant to the NHTSA request, and extract the relevant information. That's not something you can automate easily, especially when you're dealing with safety-critical situations.

But this also reveals something about Tesla's data infrastructure. If the company could quickly identify, categorize, and summarize 8,313 incidents, that would suggest really robust incident tracking and reporting systems. The fact that it takes them 27 days to process them suggests the data is scattered across multiple systems. Customer service reports something different from the telemetry system. The video storage is somewhere else. The metadata is in another place.

This is a common problem for large companies dealing with complex systems. Your data is fragmented across tools you've built over years, integrated systems you've acquired, and legacy processes that nobody wants to touch.

From NHTSA's perspective, this processing bottleneck is interesting. It suggests Tesla doesn't have a centralized, easily searchable incident database. That raises questions: if the company can't quickly find and analyze incidents, how do they identify problems and implement fixes? If it takes them weeks to even review incidents, how do they respond to safety concerns? This becomes evidence about Tesla's overall safety culture and incident response processes.

It's why NHTSA gave Tesla the extension, but it's also why regulators are probably frustrated. They want answers. Tesla is saying it'll take weeks just to compile the data, and that's not even including the analysis phase.

The Liability Question: Who's Responsible When FSD Fails?

This is the question that will ultimately determine the outcome of the investigation and its impact on Tesla.

Let's say the investigation confirms that Full Self-Driving does occasionally ignore red lights. Whose fault is that? Is it Tesla's for shipping a system with a known defect? Is it the driver's for not paying attention? Is it the manufacturer for not installing better safety verification? Is it the regulators for not establishing clearer standards?

Tesla's current position is that Full Self-Driving requires driver supervision. The system is beta. It's not fully autonomous. The driver bears responsibility for monitoring the system and taking over if something seems wrong. That's the argument Tesla uses to shift liability away from the company.

But that argument has weaknesses. If Full Self-Driving is a beta feature requiring driver supervision, why is Tesla charging

There's also a practical question: can humans realistically supervise an autonomous system that's making decisions continuously and often correctly? Research on automation bias suggests that humans get complacent when systems are right most of the time. You see correct decisions 99% of the time, so you stop paying close attention. Then the 1% failure happens, and you're not ready to take over.

From a legal liability perspective, this is where it gets interesting. If NHTSA determines that Full Self-Driving has a design defect (rather than just isolated glitches), they can issue a recall. A recall means Tesla has to fix it. If Tesla can't fix it, they might have to disable the feature. They might have to refund customers. They might face penalties.

The lawsuit potential is even bigger. If someone gets hurt in an accident where Full Self-Driving was engaged and ignored a red light, Tesla could face significant liability. A jury might not care that Tesla said the feature requires supervision. They'll look at whether the driver could realistically have been paying attention. They'll look at Tesla's marketing claims. They'll look at what the company knew about potential red-light failures.

That's why this investigation matters so much. It's not just about regulatory compliance. It's about establishing whether Tesla had knowledge of a safety defect and did nothing about it. That's the kind of thing that leads to punitive damages in liability litigation.

The investigation by NHTSA into Tesla's FSD system is primarily focused on incident analysis and inventory data, with significant attention to usage patterns and driver alerts. Estimated data based on content description.

NHTSA's Regulatory Authority and What It Can Do

People sometimes don't realize how much authority NHTSA actually has over vehicle safety. The agency can investigate potential defects. It can demand information from manufacturers. It can issue recalls. It can impose civil penalties. In extreme cases, it can seek criminal prosecution.

The process starts with investigation, which is where Tesla is right now. NHTSA gathers information and evidence. They interview complainants. They examine the vehicle. They analyze the engineering. If they determine there's a defect that poses a safety risk, they can issue a safety recall.

A safety recall is a big deal. It requires the manufacturer to fix the problem at no cost to the customer. It creates a permanent record of the defect. It affects resale value. It damages the company's reputation. For Tesla, a Full Self-Driving recall would be significant because it's a flagship feature.

If Tesla fails to comply with the recall, NHTSA can impose civil penalties. Up to $100 million per violation. If the company knowingly concealed a safety defect or provided false information to regulators, NHTSA can pursue criminal prosecution.

The information request Tesla is responding to is an investigatory step. It's how NHTSA determines whether there's a defect. NHTSA will analyze the incident data, interview Tesla engineers, and examine the technical architecture. They'll determine if the red-light failures are random glitches or systematic problems. They'll assess whether Tesla knew about the problem and did nothing.

What's notable about NHTSA's approach in this case is that they're being thorough. They're not just asking for accident reports. They're asking for the technical foundations of how FSD works. They want to understand the system deeply. That suggests they're serious about potential enforcement action.

Comparing NHTSA's Tesla Investigations to Other Automakers

Tesla isn't the only company under investigation for autonomous vehicle issues. But the frequency and intensity of NHTSA's focus on Tesla is notable.

General Motors has faced NHTSA investigations for Cruise autonomous vehicles. Waymo has been involved in incidents with autonomous vehicles. Uber's autonomous vehicle program (before it was shut down) had accidents that drew regulatory attention. But the sheer number of NHTSA investigations specifically targeting Tesla is significant.

Part of that is because Tesla's Full Self-Driving system is used by hundreds of thousands of customers on public roads every day. Most other autonomous systems are more limited in deployment. Waymo operates in specific cities. Cruise operated in San Francisco. General Motors is being more cautious with deployment. Tesla, by contrast, enables Full Self-Driving for anyone willing to pay, anywhere they want to drive.

That creates more opportunities for problems to occur and more complaints to be filed. So it's partly a numbers game: more users, more complaints, more investigations.

But it's also a regulatory approach difference. NHTSA has decided to scrutinize Tesla's claims about autonomous driving capabilities more carefully. The agency has questioned whether FSD is really as autonomous as Tesla claims. There's a fundamental tension: if Full Self-Driving requires constant driver supervision, it's not really full self-driving. It's an advanced driver-assistance feature. Tesla has been using the term "Full Self-Driving" for years, but the reality of what it requires from drivers has been inconsistent.

Other automakers have been more cautious with their language. General Motors uses the term "Super Cruise" and clearly positions it as a highway-specific feature for supported roads. It's explicit about its limitations. Tesla's marketing has been much more about the promise of full autonomy, even though the current reality is closer to assisted driving.

That gap between marketing and reality is what regulators care about. When that gap is significant, NHTSA gets involved.

The Path Forward: What Happens After February 23rd

So Tesla submits its information response on February 23rd. What happens next?

NHTSA will review the information. Investigators will go through the incident data, looking for patterns. They'll examine Tesla's technical documentation. They'll probably conduct follow-up interviews with Tesla engineers and safety personnel. They might request additional information if something in the initial submission raises new questions.

All of this takes time. NHTSA investigations can take months or even years. The agency is methodical. They build a comprehensive case before they take action.

Based on their analysis, NHTSA will make a determination. Are the red-light failures systematic design flaws? Or are they isolated glitches? Are they acceptable risks in an experimental system? Or are they serious safety problems? Is Tesla knowingly deploying a defective system? Or did they inadvertently ship something with a defect they're now working to fix?

Depending on what they find, NHTSA has several options:

Option 1: Close the investigation without recommending action. This would mean NHTSA found no evidence of a safety defect or determined that any issues are not widespread enough to warrant intervention. This is the best outcome for Tesla.

Option 2: Issue a safety recall. NHTSA would require Tesla to fix the red-light detection system. Tesla would have to determine what the fix is (software update? New hardware? Different algorithm?) and implement it for all affected vehicles. This would be costly and embarrassing but manageable if the fix is straightforward.

Option 3: Issue a recall and investigate further for criminal liability. This would be worse for Tesla. It would suggest NHTSA found evidence that Tesla knowingly shipped a system with safety defects. This opens the door to criminal prosecution under some circumstances and definitely to civil litigation from injured parties.

Option 4: Recommend that Tesla disable Full Self-Driving pending further investigation. This is extreme but possible if NHTSA determines the system is actively dangerous. It would essentially pause the full deployment of FSD while the investigation continues.

What seems most likely is some combination. NHTSA will probably find that the red-light issues are more than random isolated glitches. They'll probably issue a recall of some kind. Tesla will probably argue that the system has been improved and the recent incidents are from older versions. There will be negotiation.

The subscription model change actually provides Tesla some cover here. Tesla can argue that the move to subscriptions shows they're taking safety seriously by changing how the feature is positioned and sold. They can claim that the new pricing model emphasizes that this is still an experimental feature. They can point to whatever improvements they've made in FSD over recent months.

But ultimately, the investigation will set precedent for how NHTSA regulates autonomous features. The closer the agency looks, the harder it is for any automaker to hide system limitations or pretend experimental features are more mature than they are.

What the 60 Complaints Actually Represent

Let's talk about statistical significance for a moment. Sixty complaints sounds like a lot. But is it really?

Tesla has roughly 2.5 million vehicles on the road globally, maybe 1.8 million in the United States. Not all of them have Full Self-Driving. Estimates suggest maybe 10-15% of Tesla vehicles in the US have active FSD subscriptions or ownership. That's roughly 180,000 to 270,000 vehicles with FSD.

If 60 people complained about red-light incidents, that's a complaint rate of between 0.022% and 0.033% of FSD-equipped vehicles. That's quite low statistically. One in 3,000 to one in 4,500 vehicles.

But here's the thing: not every person who experiences an incident files a complaint. Some people don't know how to report it. Some don't bother. Some figure it's their responsibility to pay attention. The 60 complaints might represent hundreds or thousands of actual incidents.

Also, red-light incidents are severe. They're not minor navigation glitches. They're incidents where the system is making a fundamental error about one of the most basic rules of driving. Even if the rate is low, the severity means you need to address it.

From a regulatory perspective, NHTSA doesn't need a huge percentage of failures to investigate. If the failures are critical enough (like ignoring red lights), even a low percentage rate triggers investigation. The agency's standard is whether the defect creates a substantial safety risk, not whether it affects a large percentage of vehicles.

So while 60 complaints out of hundreds of thousands of users sounds statistically manageable, the nature of the complaints (red lights and oncoming traffic) makes them serious regardless of the percentage.

The Broader Question About AI-Driven Autonomous Systems

There's a philosophical question lurking beneath this investigation: how do you regulate AI-driven systems that you can't fully explain?

Full Self-Driving is built on deep learning neural networks. These are powerful but opaque. A human engineer can look at the code and understand what the algorithm is supposed to do, but they can't necessarily explain why the algorithm made a specific decision in a specific situation. The decision is the emergent property of millions of parameters tuned through training data.

That creates a problem for regulators. NHTSA wants to know: why does FSD sometimes run red lights? If the answer is "because of how the neural network weights align and interact in certain lighting conditions," that's technically accurate but not very actionable. It doesn't help NHTSA understand whether the system is fundamentally unsafe or just needs tweaking.

This is why NHTSA is asking Tesla for its "theory of operation." The agency is trying to get Tesla to articulate what the system is supposed to do and how it's supposed to do it. That's easier to regulate than understanding opaque neural networks.

But it also highlights a real tension in autonomous vehicle regulation. If you're deploying a system whose decision-making process you can't fully explain, how do you certify that it's safe? How do you identify edge cases that will cause problems? How do you write regulations that ensure safety when the system's behavior emerges from complex learned patterns rather than explicit rules?

Tesla's response to this is essentially "we test it a lot, and we monitor it in deployment." That's not fully satisfying to regulators, but it's honest. You can't fully pre-specify the behavior of a neural network-based system. You can only test it extensively and monitor it in the field.

That monitoring is what led to the red-light complaints. Some customers noticed FSD doing something weird with red lights, and they reported it. Tesla has data on what's happening. Now NHTSA wants to understand the pattern.

The outcome of this investigation will probably push the industry toward more explainability and better monitoring. Automakers will need to invest in understanding their systems better, even if that understanding is imperfect. They'll need better incident tracking and response systems. And they'll need to be more cautious about marketing capabilities that their systems can't reliably deliver.

What This Means for the Future of Autonomous Vehicles

If this investigation results in a recall or significant regulatory action, it will slow down the autonomous vehicle industry. Companies will be more cautious about deploying features they're not completely confident in. They'll invest more in testing and validation. They'll be more conservative in their marketing.

But that might actually be healthy for the industry long-term. Right now, the autonomous vehicle market is driven a lot by hype and ambition. Companies promise full autonomy soon. They deploy beta features to the public. They gather data and improve incrementally. Some of those incremental improvements might be happening in situations where humans are at risk.

If NHTSA enforces safety standards more strictly, it raises the bar for everyone. Features need to be more robust before deployment. Testing needs to be more comprehensive. The margin of safety needs to be higher. That means slower innovation but potentially safer systems.

It also means clearer liability frameworks. If NHTSA establishes that companies are responsible for safety, not drivers, that changes the business model. You can't sell a beta feature and shift safety responsibility to users if regulators say you're liable. That will push companies toward either not deploying features until they're fully ready, or building business models where they own the liability.

Waymo's approach, where the company operates the autonomous vehicles themselves rather than licensing the software to consumers, might become more common. That way, the company that built the system also bears the liability for its failures. That creates better incentives for safety.

Tesla's approach of licensing FSD to consumers, shifting safety responsibility to drivers, might become less viable if regulators crack down. Tesla could adapt by taking more liability themselves, changing how they position and price FSD, or redesigning their approach.

What's clear is that the days of moving fast with autonomous vehicle features and breaking things on public roads are ending. NHTSA is paying attention. Other regulators around the world are watching. The investigation into Tesla isn't just about one company. It's about setting the norms for how autonomous vehicles will be regulated in the United States for the next decade.

FAQ

What is NHTSA investigating about Tesla's Full Self-Driving?

The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration opened an investigation into Tesla's Full Self-Driving system after receiving more than 60 complaints about the feature either ignoring red traffic lights or crossing into oncoming traffic. NHTSA's Office of Defects Investigation is examining whether these incidents represent a systematic safety defect or isolated glitches. The investigation seeks to understand how FSD's traffic light detection works, how common the failures are, and whether Tesla knew about the problem but failed to address it.

How much time did Tesla get to respond to the investigation?

Tesla initially had until January 19, 2026 (about six weeks) to respond to NHTSA's information request. However, the company requested an extension, noting that the winter holiday period consumed two weeks of the original timeline, and Tesla is simultaneously managing three other NHTSA investigations with overlapping deadlines. The agency granted a five-week extension, moving the deadline to February 23, 2026. The extended timeline gives Tesla nearly eleven weeks total to compile and submit the requested information.

What specific information did NHTSA demand from Tesla?

NHTSA requested comprehensive data including a complete inventory of every Tesla produced and sold or leased in the United States, identification of which vehicles have Full Self-Driving and which version, cumulative data on FSD adoption and usage frequency, summaries of all customer complaints and incident reports related to FSD ignoring traffic laws, detailed causal analysis for every crash involving FSD, information about alerts shown to drivers, Tesla's technical theory of how FSD detects traffic lights and stop signs, and documentation of any modifications Tesla has made to address the problem. Tesla found approximately 8,313 potentially relevant incidents when searching its database.

Why is the red-light issue particularly serious for regulators?

Traffic light compliance is a foundational safety requirement for autonomous vehicles. Traffic lights are unambiguous signals—red means stop, green means go. If a self-driving system occasionally ignores red lights, it suggests either a failure in the perception system (the cameras and algorithms that see the light), a classification error (misidentifying the light's color), or a decision-making flaw. Any of these represents a fundamental problem in core autonomous driving logic, not a minor bug. NHTSA treats red-light failures as serious because they directly create the risk of crashes with cross-traffic, which can be fatal.

What are the potential consequences if NHTSA finds a safety defect?

If NHTSA determines that Full Self-Driving has a safety defect, the agency can issue a recall requiring Tesla to fix the system at no cost to customers. A recall creates a permanent record of the defect and damages the company's reputation. In serious cases, NHTSA can impose civil penalties up to $100 million and seek criminal prosecution. Additionally, a recall finding would expose Tesla to civil liability from anyone injured in accidents where FSD was involved. A recall of Full Self-Driving specifically would be particularly significant because it's a flagship feature and major profit driver for the company.

Why did Tesla change Full Self-Driving to a subscription model during this investigation?

Starting February 14, 2026, Tesla is shifting Full Self-Driving from a

How does this investigation affect other autonomous vehicle companies?

The NHTSA investigation into Tesla sets precedent for how federal regulators will approach autonomous systems industry-wide. If NHTSA requires comprehensive technical documentation, detailed incident tracking, or specific safety mechanisms for Tesla, other manufacturers will likely face similar requirements. General Motors, Waymo, Cruise, and others are watching carefully to understand what safety standards will be enforced. The investigation essentially establishes regulatory expectations for autonomous vehicle deployment, forcing all companies to invest in better documentation, monitoring, and incident response systems. Companies deploying systems with safety limitations that can't be immediately addressed may become more cautious about deployment until they can certify safety more comprehensively.

Why does it take Tesla 27 days just to review 8,313 incidents?

Tesla reported it can only process 300 incidents per day, suggesting significant challenges in data infrastructure and incident tracking. This slow processing rate reflects a common challenge for large companies: safety-critical data is often scattered across multiple systems—customer service databases, telemetry systems, video storage, legal documentation—that weren't designed to work together. Reviewing each incident requires human judgment to determine relevance and extract key information, which can't be fully automated in complex safety situations. The slow processing rate also suggests Tesla's incident tracking systems may not be as centralized or sophisticated as an experienced safety-focused automaker's systems might be, which raises questions about how quickly the company can identify and respond to emerging safety problems.

What does Full Self-Driving actually do compared to what Tesla claims?

Tesla markets Full Self-Driving as an autonomous driving system, but it actually functions more as an advanced driver-assistance feature that requires continuous driver supervision. FSD can accelerate, brake, and steer through intersections, change lanes, and navigate complex urban streets, but it occasionally makes critical errors—like ignoring red lights in this investigation. Tesla positions FSD as a beta feature requiring driver attention, but the marketing emphasizes autonomous capabilities more than limitations. This gap between marketing claims and actual capabilities is what draws regulatory scrutiny. A system genuinely capable of "full self-driving" shouldn't require driver intervention for basic traffic laws, creating a fundamental tension in how Tesla has positioned and priced the feature.

Conclusion: The Reckoning Point for Autonomous Vehicles

This NHTSA investigation represents a turning point for the autonomous vehicle industry. For years, companies like Tesla pushed boundaries, deployed systems to the public, gathered data, and improved iteratively. The regulatory approach was mostly hands-off, allowing the industry room to innovate. But the red-light incidents crossed a threshold. They're too fundamental, too dangerous, and too numerous to ignore.

What makes this investigation different is that NHTSA isn't just reacting to accidents. They're proactively digging into the technical architecture of a system that affects hundreds of thousands of drivers on public roads. They're asking hard questions about how the system works, how often it fails, and whether the company knew about the problems. The extended deadline to February 23rd isn't a gift to Tesla; it's a signal that the investigation is serious and comprehensive.

For Tesla specifically, the stakes are high. The company's success depends partly on Full Self-Driving being perceived as a cutting-edge feature worth paying for. A recall would damage that perception significantly. But worse would be evidence that Tesla knew about the red-light problem and didn't adequately address it before deploying the system to paying customers. That would transform Full Self-Driving from a promising feature into a liability.

The subscription model shift to $99 per month is a smart financial move regardless of regulatory outcome, but it also looks defensive. Tesla is reducing its upfront liability exposure right as liability questions intensify. Whether regulators see that as strategic adaptation or as evidence that Tesla is preparing for liability they know is coming remains to be seen.

For the broader autonomous vehicle industry, this investigation sets expectations. NHTSA is signaling that companies need better incident tracking, more comprehensive testing, more transparent communication about limitations, and more responsibility for failures. The free-wheeling, move-fast-and-break-things approach to autonomous features is becoming untenable.

Ultimately, that's probably good for safety. Self-driving cars are powerful technology with potential to save lives through safer driving. But that potential only exists if the systems are actually safe. Red lights exist for a reason. A self-driving system that sometimes ignores them isn't ready for the road. NHTSA is enforcing that basic standard, and that's exactly what regulators should do.

Tesla has five weeks to provide comprehensive information about the red-light failures. The agency has months ahead to analyze that information and reach conclusions. But the trajectory is clear: federal regulators are taking autonomous vehicle safety seriously, and companies deploying these systems to paying customers need to meet that scrutiny head-on with transparency, thorough testing, and genuine safety commitment. The days of moving fast are over. The era of proving actual safety is here.

Key Takeaways

- NHTSA extended Tesla's response deadline to February 23 after initial January 19 deadline, giving investigators more time to gather comprehensive fleet and incident data

- Over 8,313 potentially relevant incidents were found when Tesla searched its database, but processing only 300 per day reveals fragmented data infrastructure across customer service, telemetry, and legal systems

- Red-light violations represent foundation-level failures in autonomous driving—these are not minor glitches but fundamental errors in basic traffic law compliance

- Tesla's shift to 8,000 purchase) during the investigation fundamentally changes liability framing and how the feature is positioned legally

- The investigation sets regulatory precedent for autonomous vehicle safety standards industry-wide, signaling the end of move-fast-and-break-things approaches to public deployment

Related Articles

- Tesla's FSD Subscription-Only Strategy: What Changed & Why [2025]

- New York's Robotaxi Revolution: What Hochul's Legislation Means [2025]

- Physical AI in Automobiles: The Future of Self-Driving Cars [2025]

- New York Robotaxis: What Happens When One City Gets Left Behind [2025]

- Elon Musk's Tesla Roadster Safety Warning: Why Rocket Boosters Don't Mix With Cars [2025]

- Supreme Court Case Could Strip FCC of Fine Authority [2025]

![Tesla FSD Federal Investigation: What NHTSA Demands Reveal [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/tesla-fsd-federal-investigation-what-nhtsa-demands-reveal-20/image-1-1768579818398.jpg)