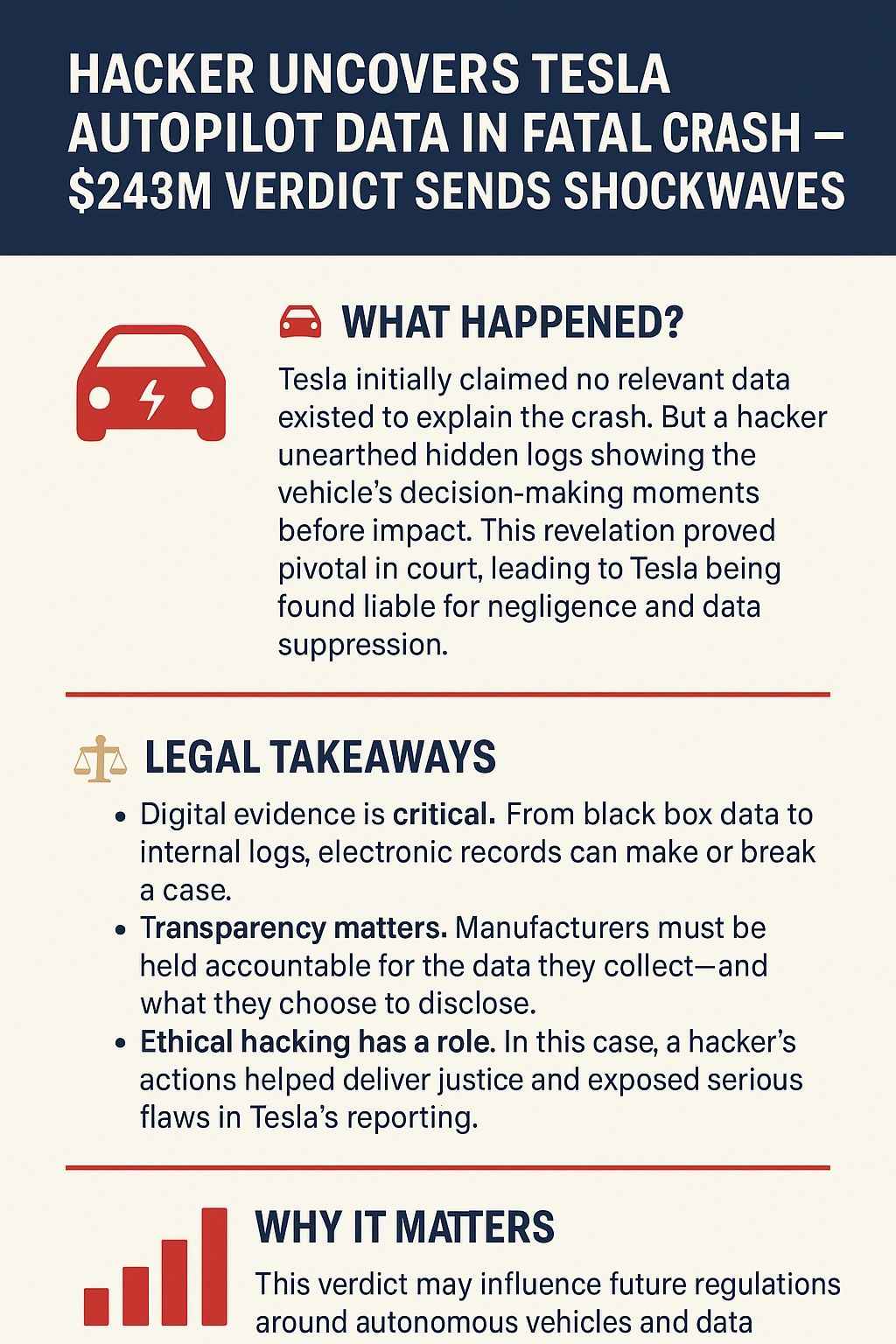

Tesla's $243 Million Autopilot Verdict: Legal Fallout & What's Next

Introduction: When Self-Driving Becomes Accountable

On a day in 2019 that nobody remembers the date of, a Tesla Model S driver bent down to pick up a dropped phone. That single moment of inattention set in motion a chain of events that would ultimately cost Tesla $243 million—and force the company to confront an uncomfortable question it's been dodging for years: who's responsible when Autopilot fails?

Federal Judge Beth Bloom's decision in August 2025 wasn't a shock to anyone who'd been watching the case unfold. She upheld the jury's verdict with a clear message: Tesla bears responsibility for the death of Naibel Benavides Leon and the severe injuries to Dillon Angulo. What makes this ruling particularly significant isn't the dollar amount (though that's substantial). It's what it signals about how courts now view self-driving features and the companies that market them, as noted by CNBC.

Tesla's response? Silence initially, followed by what insiders expect will be an appeal. The company's lawyers had already tried every defensive move in the playbook: blame the driver, claim the Autopilot system wasn't defective, argue that the Model S performed as designed. None of it stuck with the jury, and now it won't stick with Judge Bloom either, as reported by Electrek.

This case represents a turning point. For nearly a decade, Tesla has operated in a regulatory grey zone, deploying advanced driver assistance systems to millions of vehicles while maintaining they're not responsible for accidents. That era appears to be over. What happened in that courtroom in 2025 matters because it reframes how we think about autonomous technology liability, corporate accountability, and the actual safety of features marketed as "self-driving."

The question isn't whether Tesla will appeal (it will). The real question is whether this verdict signals a broader shift in how courts view autonomous vehicle manufacturers. Because if it does, the implications extend far beyond Tesla to every automaker betting on self-driving as their future.

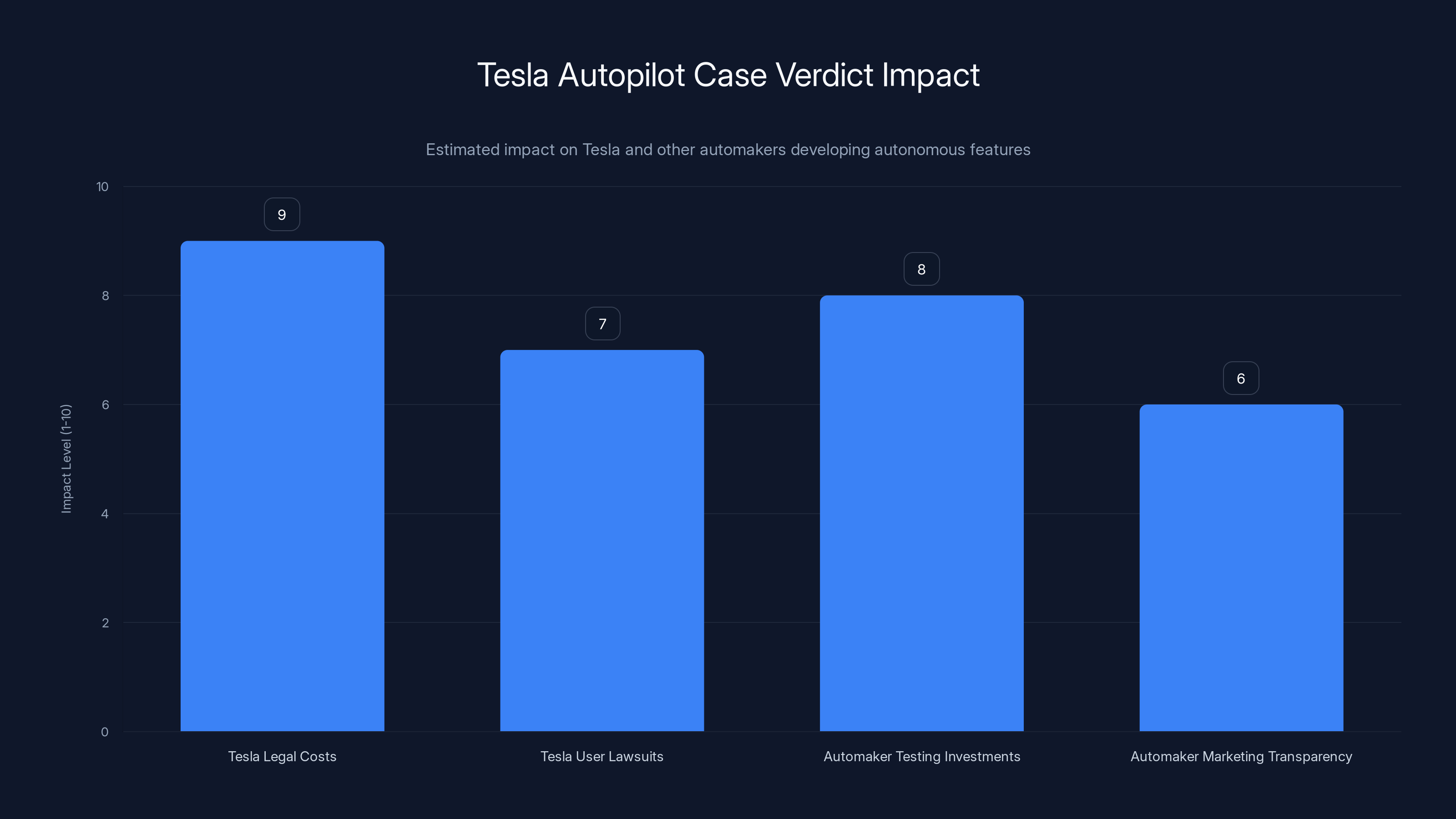

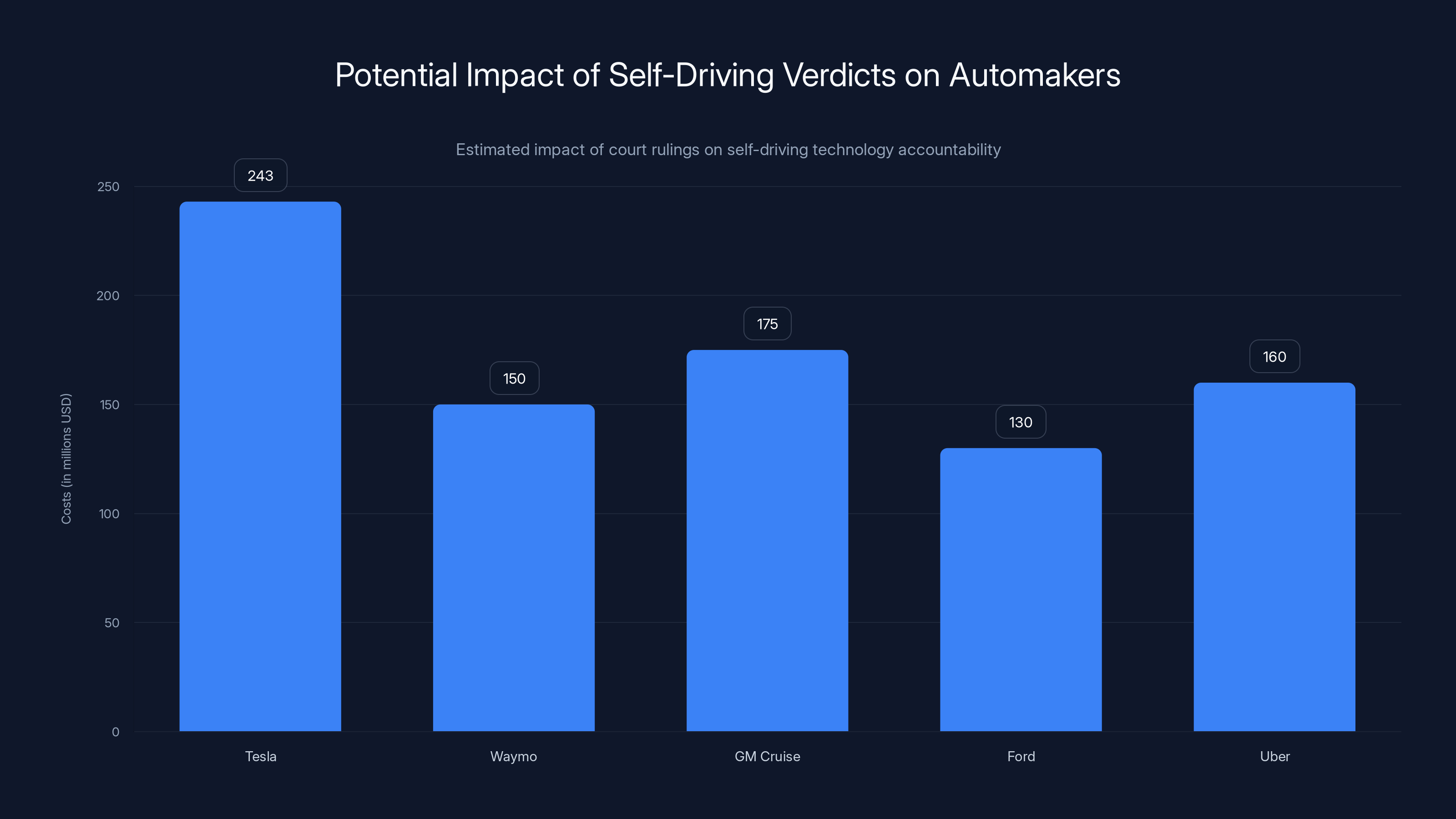

The Tesla Autopilot case verdict is expected to significantly impact Tesla's legal costs and user lawsuits, while prompting other automakers to increase investments in testing and marketing transparency. (Estimated data)

TL; DR

- $243 million verdict upheld: Federal Judge Beth Bloom rejected Tesla's motion to overturn the jury decision from August 2025, holding the company partially liable for a fatal 2019 Autopilot crash, as detailed by Reuters.

- Negligence established: The jury found sufficient evidence that Tesla's Autopilot feature was defective and inadequately warned users about its limitations.

- Appeal expected: Tesla's legal team is likely to challenge the decision with a higher court, extending this case for years.

- NHTSA investigations ongoing: Tesla simultaneously faces multiple federal investigations into both Autopilot and Full Self-Driving safety.

- Industry implications: This ruling could reshape liability standards across the autonomous vehicle industry and put pressure on regulatory frameworks.

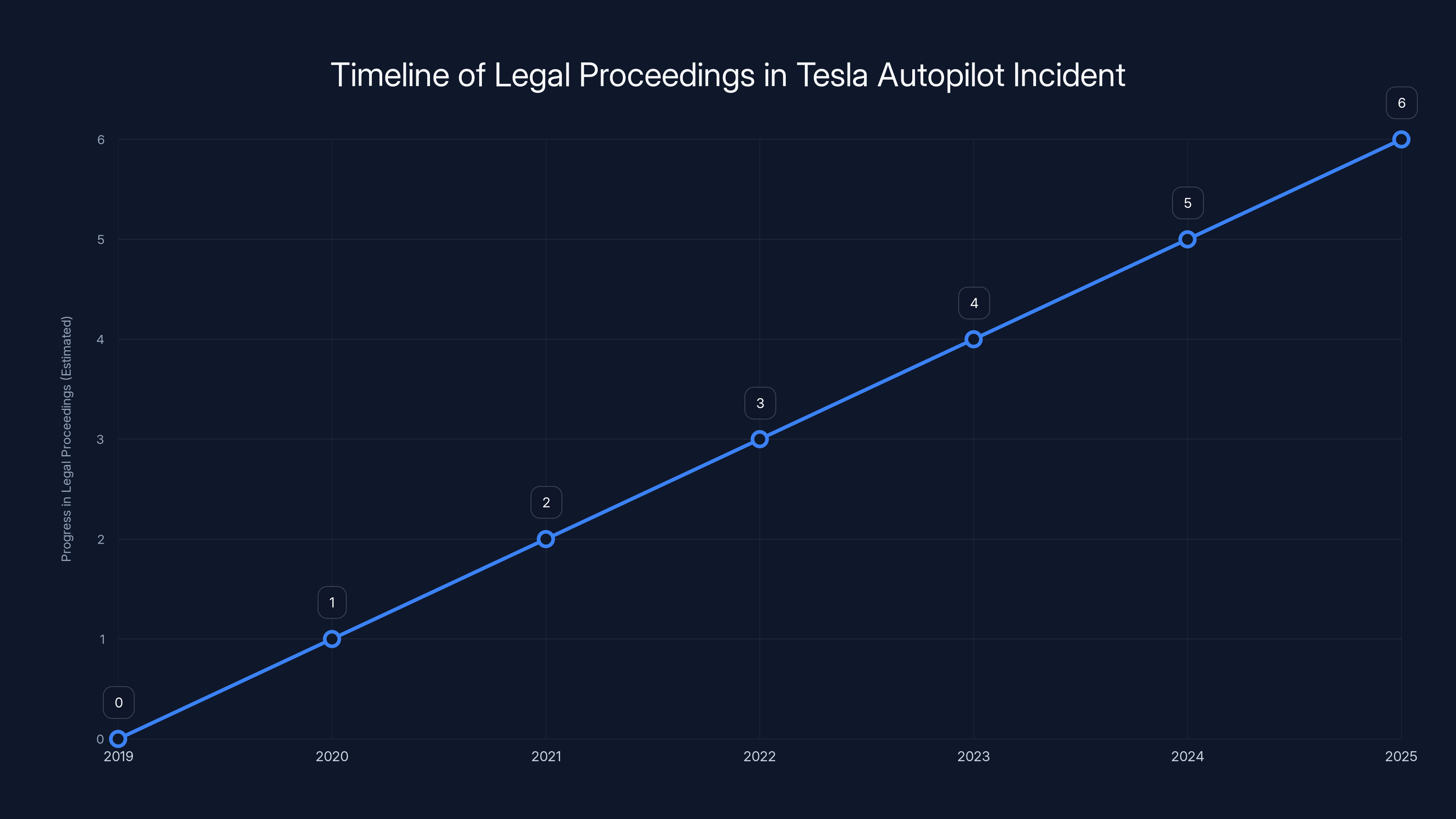

The legal proceedings took six years from the incident in 2019 to the verdict in 2025, highlighting the slow pace of legal challenges against major corporations. Estimated data.

The Incident: How a Dropped Phone Led to a $243 Million Verdict

The Moment Everything Changed

George Mc Gee was driving a Tesla Model S on a California highway. The precise details of his route don't matter as much as the one critical second where his attention shifted. He bent down to retrieve a dropped phone. In that moment, he represented something that Tesla's marketing materials had promised could be solved: human error. The Autopilot system was engaged. The car was handling things. Or so he believed.

What happened next wasn't a mechanical failure or a faulty component in the traditional sense. The Model S, running on Tesla's Autopilot software, failed to detect or properly respond to a stationary SUV parked on the shoulder of the highway. There were people standing near that vehicle. Two of them would suffer the consequences.

Naibel Benavides Leon was killed in the collision. Dillon Angulo sustained severe injuries. What makes this incident particularly relevant to a wider conversation about autonomous vehicles is that it wasn't some edge case—a completely unpredictable scenario that no system could handle. It was a stationary obstacle on a clear day. A parked vehicle on a shoulder. Something that any competent driver paying attention would see and avoid.

The Timeline: Years Between Incident and Justice

The crash happened in 2019. That's important context. By 2025—six years later—the case finally reached trial and produced a jury verdict. Judge Beth Bloom's recent decision to uphold that verdict came even later. This timeline matters because it illustrates how slowly the legal system moves when challenging major corporations. Tesla had years to prepare its defense, deploy its resources, and attempt to shape the narrative around self-driving safety.

During those six years, Tesla deployed Autopilot to millions more vehicles. The company continued marketing it as a safety feature. Elon Musk continued making claims about Full Self-Driving capability. All while litigation around a fatal failure of that same system was proceeding through the courts.

The jury verdict in August 2025 represented the first time a jury had found Tesla liable for a death involving Autopilot. That alone made it newsworthy. Judge Bloom's decision to uphold that verdict, rejecting Tesla's post-trial motions, made it consequential.

What the Evidence Showed

The jury didn't have to guess whether Autopilot worked in this scenario. They had evidence. The Model S wasn't operating at full capability when the crash occurred. The system had known limitations that Tesla either hadn't adequately disclosed or had actively downplayed in marketing materials.

Tesla's defense relied on a familiar argument: the driver was responsible. Mc Gee was the one who looked away. Mc Gee was the one who trusted Autopilot to maintain safety while retrieving a phone. By that logic, Tesla was merely providing a tool. What the driver chose to do with that tool wasn't the manufacturer's problem.

But here's where the case got interesting. Tesla's own documentation, marketing claims, and the way the feature was presented to users suggested it was more than just a tool. It was presented as capable of handling real-world driving scenarios, including maintaining safe distances and avoiding obstacles. If the feature couldn't reliably do those things, then there was a question about whether Tesla had breached its responsibility to be truthful about what Autopilot could and couldn't do.

The jury ruled in favor of the plaintiffs. Judge Bloom found that ruling justified by the evidence presented.

Judge Bloom's Decision: The Legal Foundation

Why The Judge Upheld The Verdict

Judge Beth Bloom's role wasn't to retry the case or second-guess the jury. It was narrower: did sufficient evidence exist to support the jury's verdict, and did the plaintiff present legal arguments that were sound? She found the answers to both questions to be yes.

This matters because post-trial motions give a defendant's attorneys a chance to essentially say to the judge: "Even if we lost with the jury, there's no way to interpret this evidence as supporting the verdict." It's a procedural safeguard. A judge can overturn a jury verdict if she finds that no reasonable jury could have reached that conclusion based on the evidence presented.

Bloom didn't find that here. She concluded that a reasonable jury, reviewing the same evidence, could absolutely find Tesla partially liable. The evidence supported the jury's findings. The legal theory was sound.

The Defect Argument

One of the key findings was that Autopilot was defective. This is specific legal language with important implications. A defective product is one that fails to perform as a reasonable consumer would expect or that poses unreasonable danger. The jury apparently found that Autopilot met one or both of these definitions.

Tesla had argued that the feature worked exactly as designed. The implicit argument was that if something works as designed, it can't be defective. But that logic only works if the design itself is adequate. If the design has inherent limitations that make it unreasonably dangerous, then the design itself is defective.

The jury's verdict suggested they found the design itself problematic. An Autopilot system that can't reliably detect stationary objects in clear weather is arguably not fit for the purpose Tesla implied in its marketing.

The Warning Issue

Tesla had also argued that even if Autopilot had limitations, it had provided adequate warnings to users. Judge Bloom didn't find this argument compelling either. The evidence suggested that Tesla's warnings were either inadequate or contradicted by other marketing materials that emphasized the capabilities of the system.

This is a critical finding. Liability for defective products can sometimes be mitigated if a manufacturer provides adequate warnings about known limitations. But those warnings have to actually be adequate. They have to be prominent, clear, and not contradicted by other messaging. The jury apparently found that Tesla's warnings about Autopilot failed on these counts.

The

The Victims: Human Cost Beyond The Numbers

Naibel Benavides Leon's Story

Benavides Leon died in the collision. He was standing outside his vehicle on a highway shoulder when the Model S, running on Autopilot, hit him. There's no ambiguity here. No scenario where this outcome was acceptable or foreseeable in a way that should excuse the manufacturer's responsibility.

The $243 million verdict didn't bring him back. It couldn't. But it represented the jury's finding that his death was a consequence of Tesla's negligence. That message matters to his family, to people who knew him, and to society's broader conversation about whether companies can profit from unsafe technology.

Dillon Angulo's Ongoing Injuries

Angulo survived but with severe injuries. The long-term consequences of that moment when Autopilot failed to detect a stationary vehicle will likely follow him for life. He'll potentially need ongoing medical care, rehabilitation, and will likely experience chronic pain or disability.

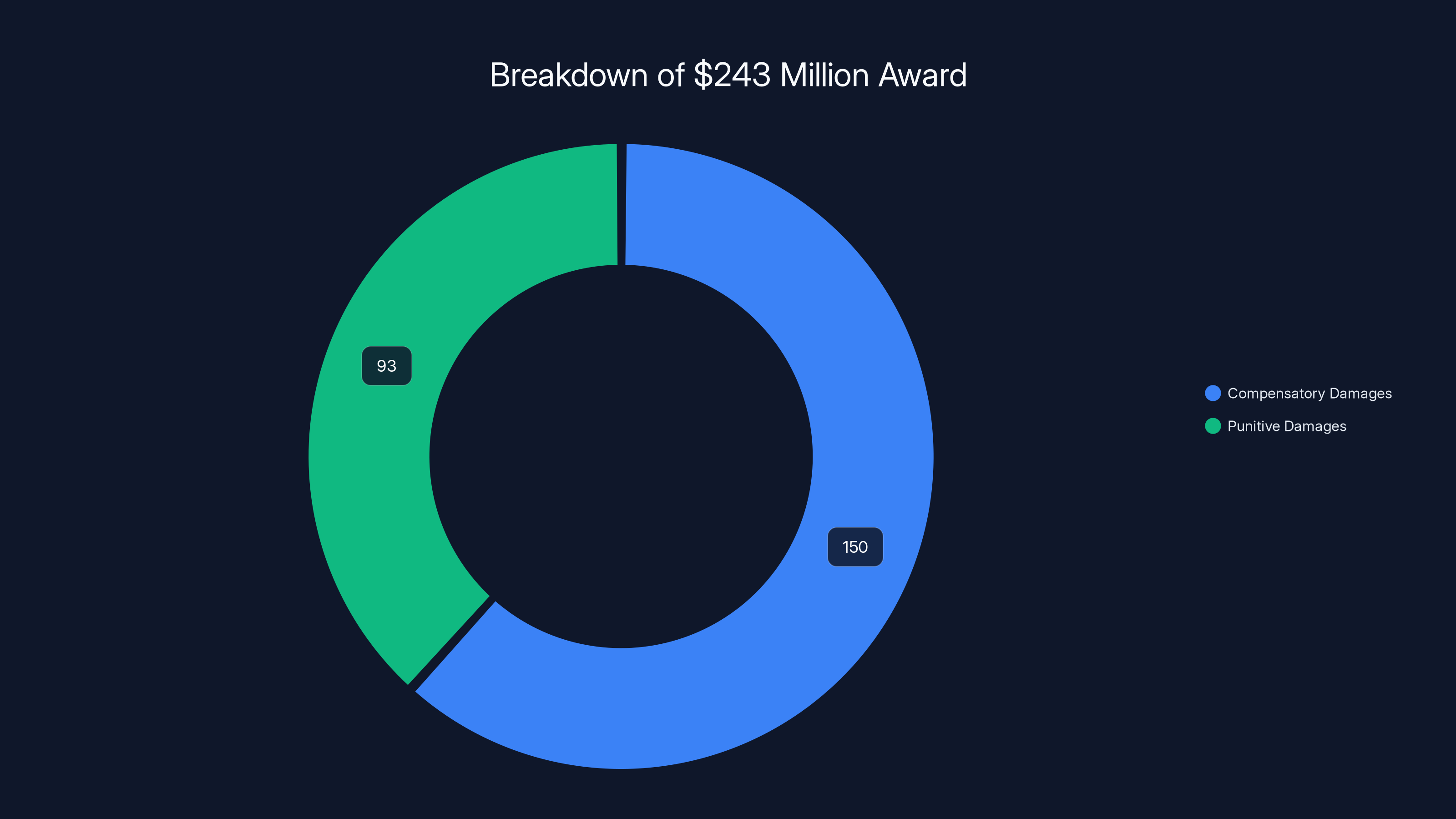

The jury award included compensatory damages for Angulo's injuries and punitive damages intended to punish Tesla for its conduct. The punitive damages component is significant. It signals that the jury believed Tesla didn't just make a mistake—they believed the company acted in a way that deserved punishment beyond simply compensating the victims.

Tesla's Legal Defense: What Didn't Work

Blame The Driver Strategy

Tesla's primary defense strategy focused on George Mc Gee. Yes, the Autopilot was engaged. Yes, the system failed to detect the parked vehicle. But Mc Gee was the one who looked away. Mc Gee was the one who assumed Autopilot could handle any situation. By accepting the feature, Mc Gee accepted responsibility for monitoring it.

The problem with this defense is that it assumes Autopilot was actually suitable for being monitored in the way Tesla implied. If you can only safely use Autopilot by never letting your attention waver for a second, then it's not much of an autopilot at all. It's a steering assist feature that happens to have a misleading name.

Moreover, driver fatigue and inattention are real. Designing a system under the assumption that every user will remain perfectly attentive is designing for failure. Good engineering accounts for human limitations. Tesla's Autopilot apparently didn't, at least not adequately enough to detect a stationary vehicle in clear weather.

The "Working As Designed" Argument

Tesla's lawyers argued that Autopilot functioned exactly as designed. No components failed. No software glitched. The system did what it was programmed to do. Therefore, it couldn't be defective.

This argument suffers from a logical flaw. A design can be inherently flawed even if every component functions perfectly. A car designed with brakes that can only stop 80% of the time might have perfectly functioning brake components—the design itself is still defective.

The evidence apparently showed that Autopilot couldn't reliably detect and respond to stationary obstacles. That's a design deficiency, not a component failure. Judge Bloom apparently agreed with the jury's interpretation.

Inadequate Warning Defense

Tesla also argued it had provided sufficient warnings about Autopilot's limitations. Users got disclaimers. The manual included cautionary language. But here's the thing about warnings: they only work if they're actually read and understood, and if they're not contradicted by other messaging from the company.

If Tesla's marketing materials emphasized the intelligence and autonomy of Autopilot, while fine-print warnings buried in manuals said not to trust it, the warnings are inadequate. The jury apparently found exactly this kind of contradiction. The marketing was too prominent relative to the warnings.

The appellate process for Tesla is estimated to take 2-3 years, with significant time allocated to each stage, particularly briefs submission and decision-making. Estimated data.

NHTSA Investigations: The Regulatory Pressure Building

Multiple Concurrent Investigations

The civil lawsuit isn't Tesla's only legal problem. The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) is conducting multiple investigations into both Autopilot and Full Self-Driving. These are separate from the jury verdict, but they're related in scope.

NHTSA has the power to issue recalls, mandate design changes, or impose fines. The agency represents government regulatory authority. A lawsuit represents private civil liability. Together, they create a vice-like pressure on Tesla to modify how it develops, markets, and deploys its autonomous features.

The investigations have examined crash data, user complaints, and whether Tesla's marketing claims match the actual capabilities of its systems. Some investigations have already resulted in recalls or driver monitoring software updates.

The Marketing Claims Problem

One consistent theme across NHTSA investigations and the civil lawsuit is that Tesla's marketing claims don't align with engineering reality. Full Self-Driving doesn't actually drive itself fully. Autopilot doesn't actually pilot automatically. These are driver assistance features with significant limitations.

Yet they're marketed using language that suggests capabilities they don't possess. NHTSA has been looking into whether this constitutes deceptive marketing. The jury verdict in the civil case suggests that at least one group of citizens already concluded Tesla had been misleading about its systems' capabilities.

Potential Regulatory Outcomes

NHTSA investigations could result in several outcomes. They might mandate specific driver monitoring capabilities. They might require more prominent warnings. They might impose fines. In extreme cases, they could mandate the disabling of features until they meet certain safety standards.

The jury verdict doesn't directly influence NHTSA's regulatory authority, but it does influence the political environment in which NHTSA operates. An agency is more likely to take aggressive regulatory action when there's already been a finding of civil liability by a jury.

The Appeal: Tesla's Next Move

Why Tesla Will Likely Appeal

Tesla hasn't commented publicly on Judge Bloom's decision, but the expectation among legal observers is that the company will appeal. Companies with the resources and stakes that Tesla has don't accept $243 million verdicts without fighting them through every available legal channel.

An appeal doesn't restart the case. It doesn't retry it with a jury. Instead, appellate courts review whether the lower court made legal errors. Did the judge properly instruct the jury? Did the trial procedure follow the law? Did the jury's verdict have sufficient evidentiary support?

Appealing also buys time. Even if Tesla ultimately loses in appeals court, that's years away. Years during which the company continues operating with these features, continues generating revenue from them, and continues deploying them to new vehicles.

What Arguments Might Work on Appeal

Tesla's appellate attorneys would likely focus on legal rather than factual issues. They might argue that jury instructions were improper. They might argue that certain evidence shouldn't have been admitted. They might argue that the verdict was inconsistent with prior case law on product liability.

One potential argument is that Autopilot isn't defective as a matter of law—it's a driver assistance feature, and driver assistance features by definition require driver attention. If a driver isn't paying attention, that's not the feature's fault. But this argument, while legally coherent, doesn't match the apparent concerns that animated the jury verdict. The jury seemed concerned specifically about whether Tesla had misrepresented Autopilot's capabilities, not about whether driver assistance features inherently require attention.

Appellate Timelines

If Tesla appeals, the appellate process will likely take 2-3 years minimum. Briefs take months to write. Oral arguments might not happen for over a year. Decisions take time after arguments conclude. During this entire period, the $243 million judgment remains a liability on Tesla's books, which affects the company's financial statements and investor perception.

Estimated data suggests that legal and compliance costs could rise significantly for automakers due to increased accountability in self-driving technology. Tesla's recent case highlights potential financial impacts.

Liability Versus Responsibility: The Philosophical Shift

What Does Liability Mean Here?

Legal liability means Tesla bears financial responsibility for the harms caused. That's distinct from legal responsibility for designing or building the car, though those often go together. Tesla is liable even though George Mc Gee was in control of the vehicle at the moment of impact.

This reflects a sophisticated legal theory: companies can be partially liable for accidents they didn't directly cause because they failed in their obligations regarding product design, marketing, or warnings. Tesla created a feature, marketed it in ways that exceeded its capabilities, and failed to warn adequately. That chain of decisions contributed to the harm.

The Defect-Based Framework

The verdict was structured around the idea that Autopilot is a defective product. That legal framework matters more than the dollar amount. Once a product is determined to be defective, manufacturers become liable not just to the specific victims in that case, but potentially to any victim harmed by that same defect.

This could have implications for hundreds of thousands of Tesla owners using Autopilot. If more crashes occur involving Autopilot's failure to detect obstacles, the precedent from this case will inform those lawsuits. Tesla might face a cascade of similar litigation.

Strict Liability Versus Negligence

The case was structured around negligence—Tesla failed to exercise reasonable care in designing, testing, or warning about Autopilot. That's distinct from strict liability, which doesn't require proving negligence, just that the product is defective.

If future cases succeed on strict liability grounds, Tesla's burden becomes even heavier. With negligence, a company might defend itself by showing it did everything it reasonably could. With strict liability, merely having the defect is enough.

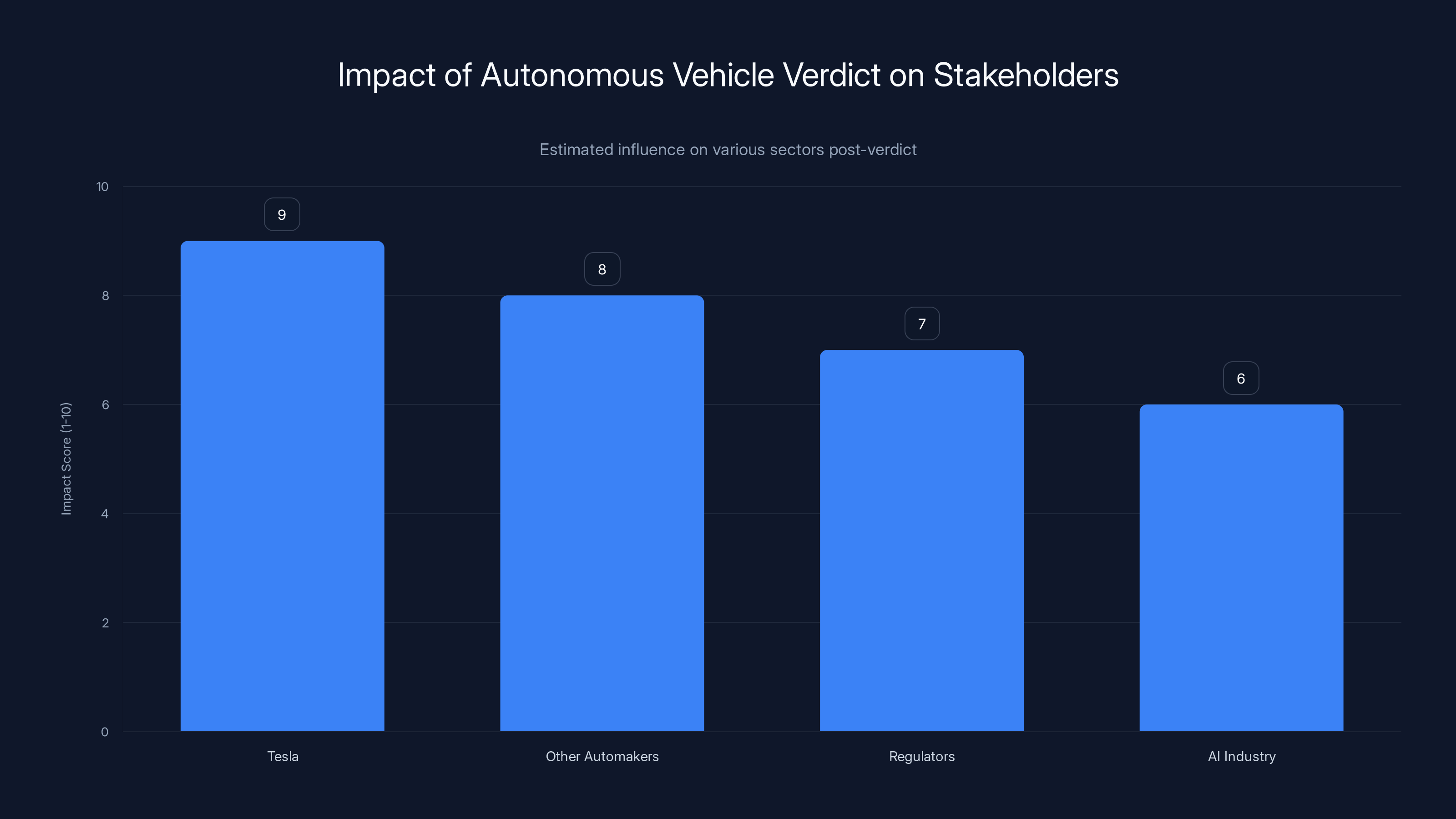

Industry Implications: What This Means For Other Automakers

The Autonomous Vehicle Liability Question

Every automaker developing autonomous or semi-autonomous features has been watching this case. The verdict doesn't directly affect them legally, but it signals how courts might treat similar disputes. If a manufacturer markets a self-driving feature that can't reliably handle common driving scenarios, they might be liable for resulting harms.

This verdict could accelerate development of more robust autonomous systems. It might also slow the rollout of features to consumers because companies will want more testing before exposing their systems to liability. Or it might push companies toward more conservative marketing claims.

Warning Labels Going Forward

We'll probably see more explicit warnings and limitations in the documentation for autonomous features across the industry. Companies will want to be able to point to clear warnings if accidents occur. But there's a tradeoff: the more prominent and cautious the warnings, the less attractive the feature becomes to consumers, and the less perceived value proposition.

Insurance and Risk

Insurance companies are already adjusting their models for autonomous features. They're more likely to charge higher premiums or include restrictions for vehicles using Autopilot or similar systems. Some insurance products might explicitly exclude coverage for accidents involving Autopilot. The verdict will likely accelerate these trends.

Regulatory Pressure Across the Sector

NHTSA and state regulators are likely to develop more specific standards for autonomous vehicle features. They might require certain safety thresholds before features can be sold. They might mandate specific warning protocols. The verdict doesn't force any of this, but it creates political momentum for it.

The $243 million verdict against Tesla significantly impacts various stakeholders, urging transparency and accountability in autonomous vehicle and AI technology. (Estimated data)

The Economics of The $243 Million Award

Breaking Down The Number

The $243 million verdict consists of compensatory damages and punitive damages. Compensatory damages cover actual harms: medical expenses, lost earnings, pain and suffering. Punitive damages are separate—they're intended to punish the defendant and deter similar conduct.

For a company like Tesla, which has annual revenues in the tens of billions, a $243 million judgment is material but not catastrophic. It won't bankrupt the company or force fundamental changes. But it's also not negligible. It's the kind of number that gets attention from investors and boards of directors.

Potential For Larger Awards

This is a single case involving one death and one severe injury. Tesla has deployed Autopilot to millions of vehicles over many years. If there's a systematic defect that causes additional crashes, there could be many more lawsuits. Class action lawsuits could potentially involve thousands of plaintiffs.

The cumulative liability could be substantially larger than $243 million. Some legal analysts have speculated that if Tesla faces hundreds of similar lawsuits and loses even a fraction of them, the total liability could reach billions.

Impact on Insurance Costs

Tesla's insurance premiums, particularly for product liability coverage, will likely increase substantially. The company might face difficulty finding insurers willing to provide coverage at any price for autonomous features. Some insurers might opt out of covering autonomous vehicle-related claims entirely.

Shareholder Implications

Tesla investors have been watching these cases with concern. A $243 million judgment is a negative event that affects the company's risk profile. Multiple similar judgments could affect Tesla's ability to maintain its valuation and investor confidence.

The Bigger Picture: Self-Driving Safety Standards

Current Regulatory Framework Gap

One reason cases like this matter is because there's still no comprehensive federal safety standard for autonomous vehicle features. NHTSA has some guidance, but it's not as specific as standards for traditional vehicle systems like brakes or airbags.

Without clear safety standards, companies have significant latitude in deciding how much testing to do before deploying features. They're constrained by legal liability and public relations concerns, but not by clear regulatory requirements.

The verdict doesn't create safety standards, but it does increase the liability risk for companies that deploy inadequately tested features. That's an indirect form of enforcement.

Testing and Validation Standards

There's an ongoing debate in the industry about what constitutes adequate testing for autonomous features. Miles driven? Accident rates relative to human drivers? Specific scenario performance? There's no consensus.

Tesla's approach has been to deploy features to customers and use real-world data to improve them. This is sometimes called "release and iterate." It's efficient from a development perspective, but it puts customers at risk during the iteration phase.

The verdict suggests that courts might not accept this approach indefinitely. Companies might need to achieve higher confidence levels before deploying, or they might face liability for problems discovered by customers.

The Human Baseline Problem

One common argument from autonomous vehicle companies is that their systems don't need to be perfect, just better than human drivers. Human drivers crash and kill people all the time. If autonomous systems do better, that's an improvement.

But the jury verdict suggests courts might not accept this argument uncritically. Even if Autopilot crashes less frequently than human-driven cars, if it crashes in ways that humans wouldn't—like failing to detect stationary obstacles—that might be grounds for liability.

Tesla's Safety Record: Context For The Verdict

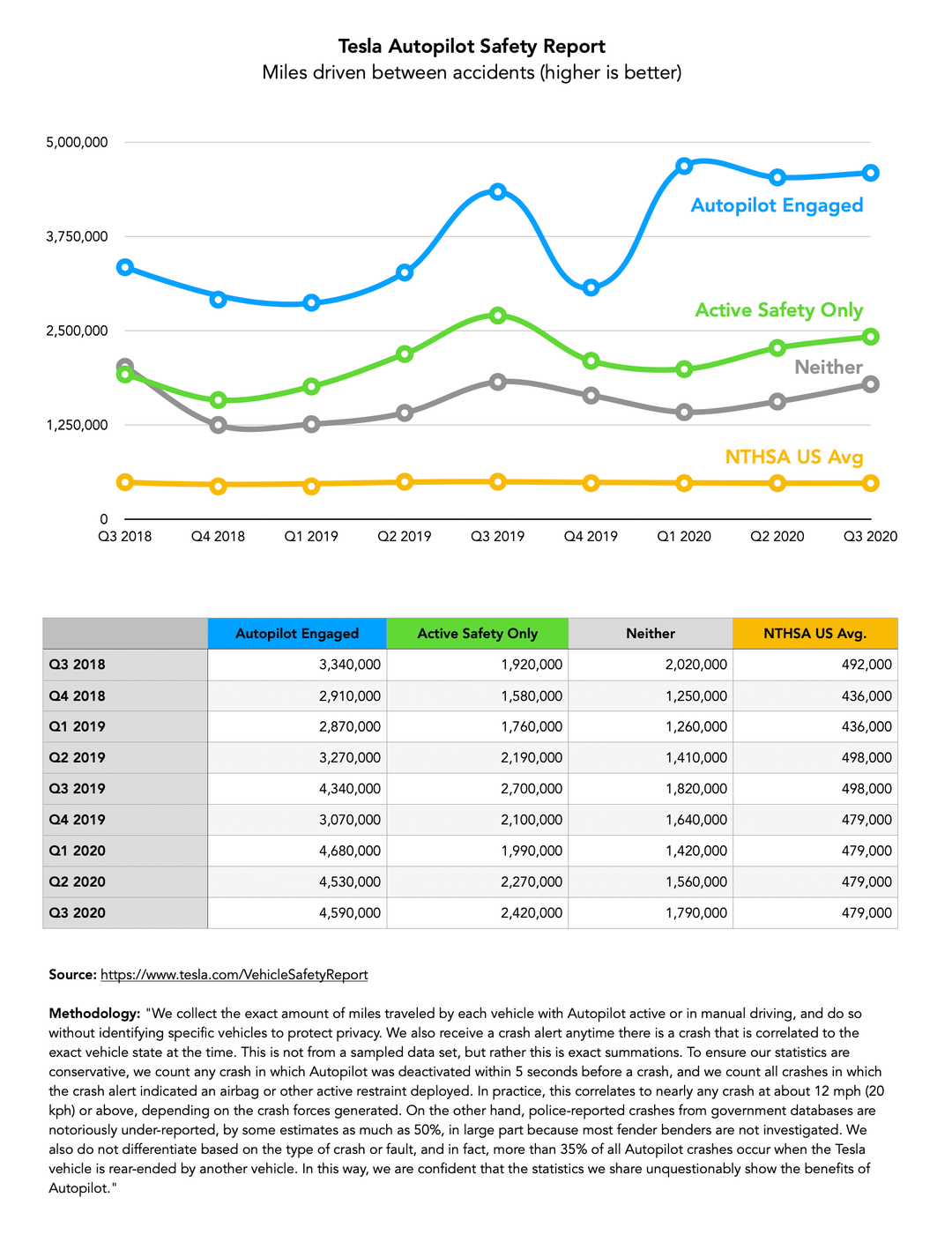

Crash Statistics and Autopilot Use

Tesla has publicly stated that Autopilot-equipped vehicles have lower crash rates than traditional cars. The company argues this demonstrates the safety benefits of its system. But crash statistics need context.

Autopilot is used on highways more than city streets. Highway driving is inherently safer than city driving. So comparing Autopilot vehicles to the general driving population involves different road types and conditions.

Additionally, even if Autopilot reduces crashes overall, if it fails in specific scenarios—like detecting stationary obstacles—that's still a design problem that might warrant liability.

Known Limitations and Failures

Tesla has experienced multiple issues with Autopilot over the years. The system has been known to fail in heavy rain, at dusk, and in situations with poor lane markings. NHTSA investigations have documented specific failure modes.

The company has made improvements, but the verdict reflects the jury's finding that these limitations were inadequately disclosed to users.

Tesla's Approach to Safety Updates

Tesla deploys software updates wirelessly to all its vehicles. This means safety improvements can be distributed quickly. But it also means the company can make significant changes without going through formal regulatory approval processes.

This flexibility is an advantage for correcting problems quickly, but it also means there's less formal oversight of the changes being made.

Market Reaction and Investor Sentiment

Stock Price Impact

When the jury verdict came down in August 2025, Tesla's stock price responded negatively, though the impact was relatively modest. Markets often anticipate major negative events before they happen, so by the time the verdict arrived, some of the bad news was already priced in.

Judge Bloom's decision to uphold the verdict likely had a smaller stock price impact than the original jury verdict, since it was largely expected.

Long-Term Investor Concerns

Investors are concerned about the potential for multiple similar suits. If this verdict stands and is used as a precedent, other victims of Autopilot failures might be emboldened to sue. Each successful lawsuit increases the total liability Tesla faces.

This is particularly concerning if there's a pattern of Autopilot failures in specific scenarios. Then you might have not just several individual lawsuits, but potentially a class action involving thousands of plaintiffs.

Insurance and Credit Implications

Tesla's insurance costs will rise. The company's credit rating might face pressure if liability concerns grow. These factors affect the company's ability to finance operations and capital investments.

Precedent and Future Cases

How This Case Will Influence Future Litigation

Tesla will likely face additional lawsuits from victims of Autopilot crashes. Plaintiffs' attorneys will cite this verdict as establishing that Autopilot has known limitations inadequately disclosed to users. This makes subsequent cases easier to win—the hard work of establishing liability has already been done.

Defendants in future cases might have to explain why their Autopilot failures are different from the failure in this case. If there's a pattern, it gets harder to claim each case is unique.

Application to Other Autonomous Features

Tesla also offers Full Self-Driving, a more advanced autonomy feature. This verdict could influence how courts treat Full Self-Driving if accidents occur. The liability framework established for Autopilot—defect based on inadequate disclosure of limitations—could apply to Full Self-Driving as well.

Other automakers might also face similar liability if their autonomous features have comparable limitations inadequately disclosed.

Class Action Potential

If Tesla owners who've purchased Autopilot feel they were misled about the feature's capabilities, they might pursue a class action for damages or refunds. This verdict doesn't establish that immediately, but it supports the legal theory that such a claim could succeed.

What's Next: Timeline and Possibilities

The Appeal Process

Tesla will likely file an appeal within a specific timeframe. Appellate courts move slowly, so years will pass before there's a final decision. During this period, the judgment stands unless stayed by the court, meaning Tesla has an ongoing liability on its books.

The appeal could result in affirmation of the verdict, reversal, or ordering a new trial. Most likely is affirmation—appellate courts typically defer to jury verdicts unless there's a clear legal error.

Potential Settlement Negotiations

While Tesla pursues its appeal, there's also the possibility of settlement negotiations. The company might decide that settling additional pending cases at a negotiated rate is more economical than fighting each one individually through appeal.

Settlement would give Tesla more certainty about its total liability while avoiding the unpredictability of additional jury verdicts.

Regulatory Changes

NHTSA investigations might result in regulations that require specific safety improvements to Autopilot. These could include better obstacle detection, improved driver monitoring, or more aggressive warnings.

Tesla could be forced to disable certain features until they meet new safety standards, or deploy substantial engineering resources to upgrade the system.

Market Evolution

Competitors like General Motors, Ford, and BMW are developing their own autonomous features. This verdict affects the entire market by raising the bar for liability. Companies will likely invest more in testing and validation before deploying, which slows but hopefully improves autonomous vehicle development.

The Broader Conversation: Accountability in the AI Age

Manufacturer Responsibility for AI Systems

Autopilot is powered by neural networks and machine learning. This raises the question of whether traditional product liability law applies to AI systems. You can't always predict how an AI system will behave in every scenario—that's the nature of machine learning.

But this verdict suggests courts are willing to hold manufacturers accountable for AI system failures anyway. The standard isn't that AI has to be perfect or perfectly predictable—it's that the manufacturer has to be honest about what the system can and can't do.

Marketing Versus Reality

One consistent theme across this case is the mismatch between how Tesla marketed Autopilot and what it actually does. This verdict reinforces that manufacturers can't hide behind technical accuracy while implying capabilities they don't possess.

As AI becomes more prevalent in consumer products, this principle will likely extend beyond vehicles. Companies developing AI systems need to be careful about marketing claims.

Corporate Accountability and Public Safety

The verdict represents the civil legal system attempting to create accountability for a large corporation. The jury decided that Tesla's choices regarding Autopilot design, testing, and marketing contributed to harm. That contribution justified liability.

It's a form of accountability that the regulatory system hadn't yet established. NHTSA hadn't mandated specific safety improvements before the jury reached its verdict. The civil system moved faster than the regulatory system.

FAQ

What was the verdict in the Tesla Autopilot case?

A federal jury found Tesla partially liable for a fatal 2019 crash involving Autopilot, awarding $243 million in compensatory and punitive damages to the victims' families. The jury determined that Tesla's Autopilot system was defective and that the company had inadequately warned users about the feature's limitations.

Why did the judge uphold the verdict?

Judge Beth Bloom determined that sufficient evidence existed to support the jury's findings. Tesla's arguments that the driver was solely responsible or that Autopilot worked as designed didn't overcome the evidence showing the feature had known limitations inadequately disclosed to consumers. The judge found no legal errors that would warrant overturning the jury verdict.

Will Tesla appeal the decision?

While Tesla hasn't formally announced plans, legal observers expect the company to appeal given the substantial financial stakes involved. An appeal doesn't restart the case but instead asks a higher court to review whether the trial judge made legal errors. The appellate process typically takes 2-3 years or more.

What does this mean for other Autopilot users?

The verdict establishes legal precedent suggesting that courts will hold Tesla liable for Autopilot failures that result from the system's defective design or inadequate warnings. Other Autopilot users harmed in similar crashes may be emboldened to pursue lawsuits, citing this verdict as establishing that Tesla bears responsibility for such failures.

How does this affect other automakers developing autonomous features?

The verdict signals that courts will scrutinize autonomous vehicle features and hold manufacturers accountable for misrepresenting their capabilities or failing to adequately warn about limitations. Other automakers developing similar features will likely invest more heavily in testing, validation, and transparent marketing to reduce their liability exposure.

What's the difference between the civil lawsuit and the NHTSA investigations?

The civil lawsuit is a private legal action between the victims and Tesla seeking monetary damages. NHTSA investigations are federal regulatory actions that could result in mandatory recalls, design changes, fines, or other regulatory enforcement. Both represent different accountability mechanisms operating in parallel.

Could there be a class action lawsuit against Tesla?

Potentially. If it can be shown that many Autopilot users were misled about the feature's capabilities, a class action for damages or refunds could be pursued. This verdict establishes the legal theory that Tesla made misleading claims about Autopilot, which would support a class action claim.

How much could Tesla's total liability ultimately be?

No one knows, but it could be substantial. This is a single case involving one death and one severe injury. If there's a pattern of Autopilot failures and similar lawsuits succeed, total liability could reach billions across multiple cases and potential class actions.

Will Autopilot be disabled or recalled?

Not based on this verdict alone. However, NHTSA investigations could result in mandated changes, recalls, or feature disabling if the agency finds the system poses unreasonable safety risks. Tesla might also voluntarily make improvements to avoid additional litigation.

What should Autopilot users know?

Autopilot is a driver assistance feature that requires continuous driver attention and monitoring. It's not a self-driving system despite its name. Users should understand its limitations, particularly regarding obstacle detection in various weather and lighting conditions, and should not treat it as a replacement for active driving.

Conclusion: A Reckoning With Autonomous Vehicle Reality

The $243 million verdict and Judge Bloom's decision to uphold it represent more than a judgment against Tesla. They represent a shift in how society views the claims made by autonomous vehicle companies. For nearly a decade, Tesla has operated in a regulatory and legal grey zone, deploying Autopilot to millions of vehicles while maintaining that the company wasn't responsible if the system failed.

That era has ended, at least in the courts.

What makes this case particularly significant is the clarity of the finding. It wasn't that Tesla's engineers did their best and the system failed anyway. It was that Tesla created a defective product and didn't adequately warn users about its limitations. That's actionable negligence that justifies liability.

The question now is whether Tesla's appeal will succeed. The company has substantial legal resources and a team of experienced attorneys. But appellate courts rarely overturn jury verdicts unless there's a clear legal error, and the legal theory here is sound. A manufacturer can be liable for not adequately disclosing the limitations of its safety-related features.

For other automakers watching this case, the message is clear: you need to be meticulous about testing autonomous features and transparent about their limitations. Marketing claims that exceed engineering reality will expose you to liability. Warnings buried in fine print while marketing emphasizes capabilities won't protect you.

For regulators, the verdict fills a gap the regulatory system hadn't yet addressed. NHTSA hadn't established specific safety standards that would have prevented Autopilot from being deployed. The civil litigation system did what the regulatory system hadn't: established accountability for inadequate safety measures.

For the broader AI industry, this case sends a message that extends beyond automotive. As AI becomes embedded in more products, manufacturers need to be truthful about what their AI systems can and can't do. They can't hide behind technical precision while implying capabilities they don't possess. Users need to understand real limitations, not marketing claims.

Tesla will likely spend years appealing this verdict. It might ultimately lose at every level, or it might find some basis for reversal. The journey isn't over. But the trajectory is clear: courts are now willing to hold autonomous vehicle manufacturers accountable for failures that stem from inadequate design or disclosure.

For George Mc Gee, Naibel Benavides Leon, and Dillon Angulo, this verdict won't undo what happened. But it establishes that Tesla bears responsibility for the choices it made regarding Autopilot. That's the minimum foundation for a society serious about autonomous vehicle safety.

The real test will be whether this verdict changes how Tesla develops and markets its autonomous features, and whether other manufacturers learn from it. Because the fundamental issue wasn't Tesla's engineering—it was Tesla's truthfulness about what its engineering actually provided. If future autonomous vehicle development prioritizes honest communication about limitations over aggressive marketing claims about capabilities, then this verdict will have served its purpose.

For now, Tesla faces the prospect of additional lawsuits, higher insurance costs, regulatory pressure, and investor concerns about long-term liability. The appeal process will take years. But the foundation of accountability has been established, and that changes everything about how autonomous vehicle development and deployment will proceed going forward.

Key Takeaways

- Federal judge upheld $243 million verdict against Tesla for fatal Autopilot crash, establishing manufacturer liability for defective autonomous features.

- Jury found Tesla's Autopilot was defective and that the company inadequately warned users about its real limitations versus marketing claims.

- The case sets legal precedent that companies can't hide behind technical accuracy while implying capabilities their AI systems don't actually possess.

- Tesla faces multiple concurrent NHTSA investigations into Autopilot and Full Self-Driving, representing both civil and regulatory accountability pressure.

- Industry-wide implications suggest autonomous vehicle makers must prioritize transparency about limitations and may face increased liability exposure for safety-related failures.

Related Articles

- Waymo Robotaxi Strikes Child Near School: What We Know [2025]

- Waymo's School Bus Problem: What the NTSB Investigation Reveals [2025]

- Tesla's $243M Autopilot Verdict Stands: What the Ruling Means [2025]

- Waymo's Fully Driverless Vehicles in Nashville: What It Means [2025]

- Tesla Electronic Door Handles: Deaths, Lawsuits, and Safety Concerns [2025]

- Waymo Robotaxi Hits Child Near School: What We Know [2025]

![Tesla's $243 Million Autopilot Verdict: Legal Fallout & What's Next [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/tesla-s-243-million-autopilot-verdict-legal-fallout-what-s-n/image-1-1771697145064.jpg)