Waymo's School Bus Problem: What the NTSB Investigation Reveals [2025]

Waymo has a school bus problem, and it's getting serious.

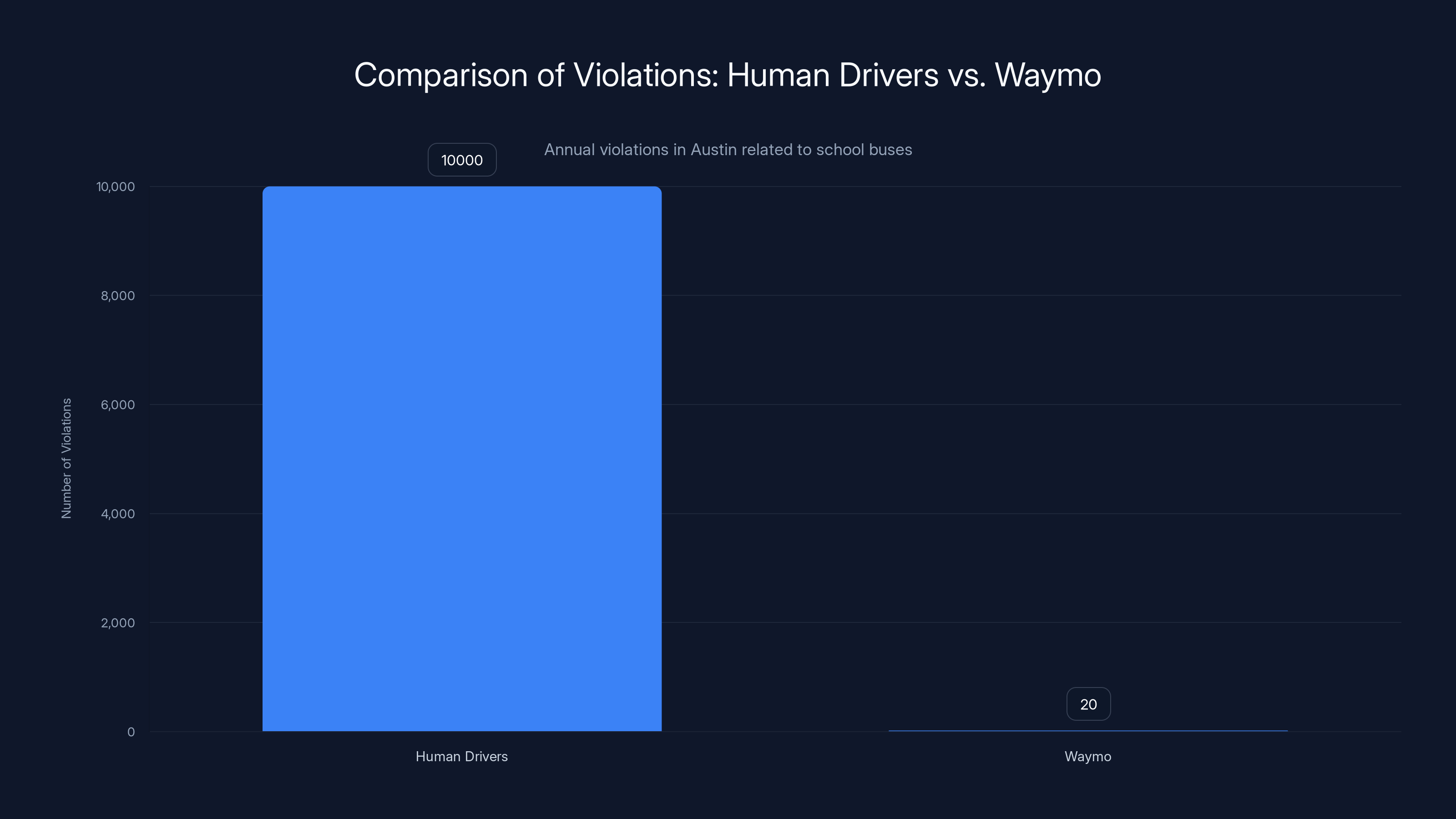

The National Transportation Safety Board opened an official investigation after Waymo robotaxis illegally passed stopped school buses more than 20 times in Austin, Texas alone. This isn't a theoretical concern or a minor edge case. Kids are getting off buses. Drivers are following traffic laws. And autonomous vehicles are breaking them.

But here's what caught my attention: Waymo's own safety officer claimed their vehicles are "superior to human drivers" around school buses. Yet human drivers aren't getting investigated by the NTSB. That disconnect matters. A lot.

This investigation reveals something uncomfortable about autonomous vehicle development in 2025. We've built systems smart enough to navigate city streets, handle traffic lights, and operate in multiple states simultaneously. Yet they can't reliably recognize a school bus with flashing red lights and a stop sign.

That's not a technological challenge. That's a testing and validation problem.

TL; DR

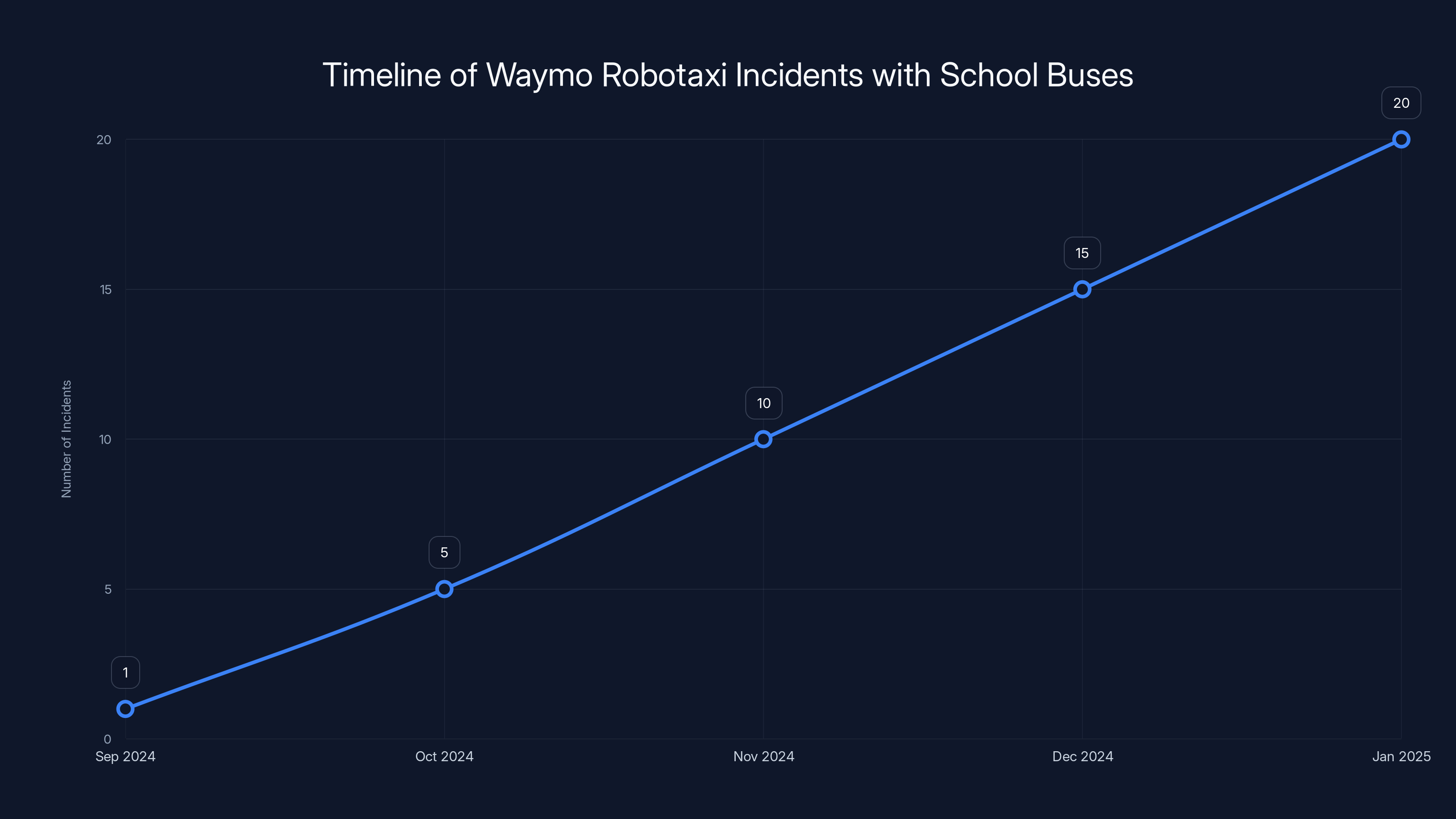

- NTSB opened formal investigation: Over 20 documented cases of Waymo robotaxis passing stopped school buses in Austin, Texas

- Second investigation running parallel: NHTSA's Office of Defects Investigation launched a similar probe in October, before NTSB involvement

- Software updates haven't fixed it: Waymo issued a recall in December 2024, but incidents continued afterward

- Safety claims versus reality: Waymo claims superior safety performance, but the incidents and investigations suggest otherwise

- Bottom line: The gap between what autonomous vehicles claim they can do and what they actually do safely is narrowing—but in the wrong direction

The timeline illustrates the increase in documented Waymo robotaxi incidents with school buses, highlighting a significant rise in late 2024. Estimated data based on reported incidents.

The Incident Timeline: How Waymo's School Bus Problem Escalated

The first major incident happened in September 2024 in Atlanta, Georgia. A Waymo robotaxi pulled out of a driveway and crossed directly in front of a stopped school bus, passing perpendicular to the vehicle while children were exiting. Waymo later claimed the vehicle couldn't detect the stop sign or flashing lights.

That's already a problem statement right there. Stop signs on school buses are reflective orange and red, highly visible during daylight hours. Flashing red lights are a standard traffic control device. If a vehicle can navigate complicated urban intersections but can't register these signals, something is fundamentally broken in the perception or decision-making system.

Waymo responded with what they called a "software update" to address "this particular scenario." This phrasing is important. They didn't say they fixed school bus detection broadly. They fixed that specific scenario. That's like a surgeon saying they successfully operated on that particular patient's heart, so hearts are solved now.

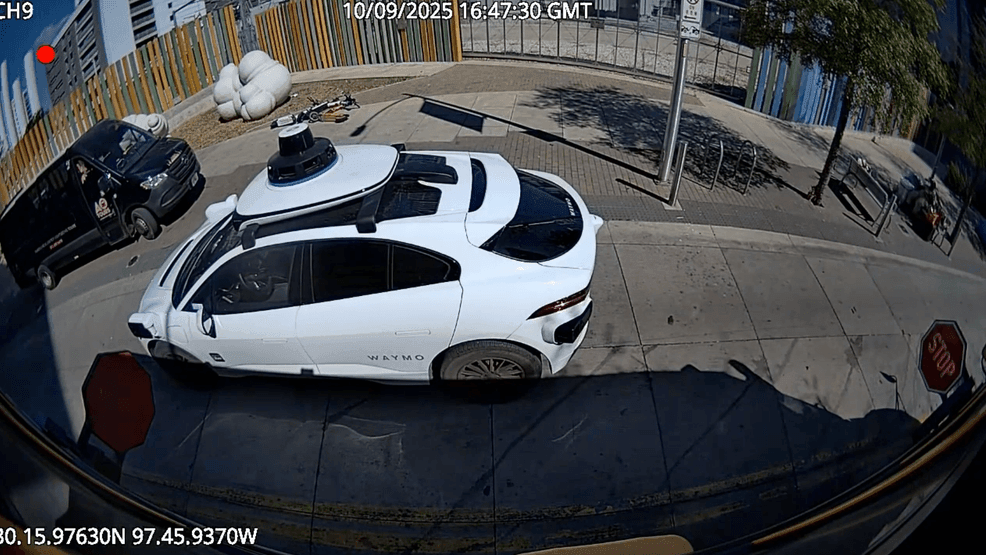

But even as Waymo was patching the Atlanta incident, their vehicles were passing school buses in Austin. Local news outlet KXAN obtained footage from school bus dashboard cameras showing multiple Waymo robotaxis making the same illegal maneuver repeatedly. These weren't fringe cases or unusual traffic conditions. These were straightforward scenarios: a bus is stopped, lights are flashing, children are boarding or exiting.

The pattern became undeniable. Between the Atlanta incident in September and the NTSB's announcement in January, Waymo encountered the same problem in at least two states, across multiple vehicles, despite claiming to address it. The December software recall didn't stop the behavior either.

This escalation timeline matters because it shows a company playing catch-up on a safety issue that should have been caught during development, not on public roads with real children present.

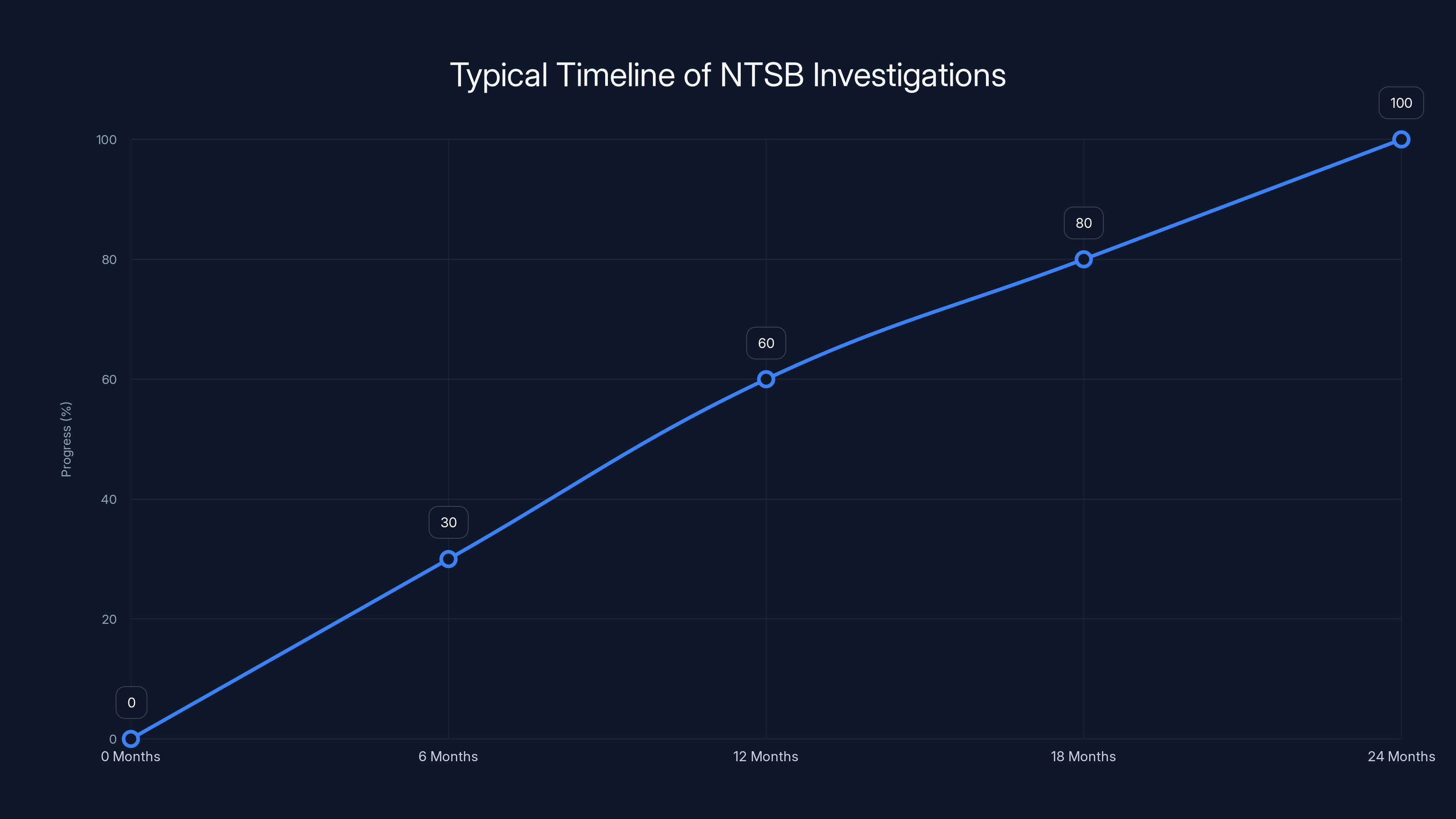

NTSB investigations are thorough, often taking 12-24 months to complete. This ensures detailed analysis and comprehensive findings. Estimated data.

Why the NTSB Investigation Matters More Than You Think

People often confuse the NTSB with the NHTSA. They sound similar and both deal with transportation safety, but they operate completely differently.

The NHTSA is a federal regulatory agency. They set standards, enforce rules, issue fines, and can mandate recalls. When NHTSA opens an Office of Defects Investigation, companies take it seriously because there are legal and financial consequences. NHTSA can force changes.

The NTSB doesn't have that authority. They can't issue fines or penalties. They can't force recalls, though companies often comply with recommendations. What the NTSB does instead is deep investigation. They go to sites, interview people, examine systems, identify root causes, and publish findings. Their reports become the permanent record of what happened and why.

So when the NTSB announces they're investigating Waymo, what they're really saying is: "We're going to understand exactly why this happened, and we're going to tell the world what we find."

That's actually more valuable than you might think. An NTSB investigation isn't just about the company being investigated. It establishes precedent and expectations for everyone else in the industry. If the NTSB determines that school bus detection failures stem from inadequate testing, every other autonomous vehicle company operating in the US has to worry that they'll be next.

The timeline matters here too. The NTSB says they'll publish a preliminary report within 30 days, with a detailed final report in 12 to 24 months. That's not fast. But it's thorough. The NTSB investigation into Boeing's 737 MAX crashes took months. The Tesla Autopilot investigations took similar timeframes. These boards don't rush.

Which means Waymo is living with this cloud of uncertainty for the next year or more. Every incident gets scrutinized. Every software update is examined. Every city council meeting where someone brings up the investigation becomes a moment of vulnerability.

The Technical Problem: Why Can't Autonomous Vehicles Recognize School Buses?

This is where the investigation gets interesting, because the technical failure reveals something about how autonomous vehicles actually work versus how they're marketed.

A school bus is one of the most distinctive vehicles on the road. They're oversized, bright yellow (or orange in some regions), have large stop signs on the sides, and flash bright red lights when stopped. The visual signal is unmistakable to human drivers. A 5-year-old can learn to recognize a school bus.

So why can't Waymo's vehicles?

The answer involves a cascade of problems in how autonomous vehicles perceive their environment. Waymo uses a combination of cameras, lidar (laser-based detection), and radar to build a 3D model of the world. Each sensor has limitations. Cameras can be fooled by glare or unusual lighting. Lidar works well at night but struggles in bright sunlight. Radar detects motion but has lower resolution.

But here's the bigger issue: autonomous vehicles aren't looking for "school buses." They're looking for patterns. The system identifies objects that match learned patterns from training data. If the training data didn't include enough examples of school buses in various lighting conditions, weather, angles, and positions relative to the vehicle, the system won't recognize them reliably.

Waymo's Atlanta incident is instructive. The company claimed the vehicle "couldn't see the stop sign or flashing lights." That's a direct statement that their perception system failed to detect two of the most distinctive safety indicators for this situation. The stop sign failure is particularly damning because it suggests their system failed to recognize a standard regulatory device that's been in use for decades.

There's also a decision-making layer separate from perception. Even if the vehicle detects a stopped school bus, it has to decide what action to take. The decision tree should be straightforward: "School bus is stopped, therefore I stop." But what if the vehicle's planning system had conflicting priorities? What if it detected a forward path that looked clear and didn't weight the school bus signal heavily enough in its decision-making algorithm?

This is where testing becomes critical. Autonomous vehicle companies test in simulation, on closed tracks, and then on public roads. But simulation is only as good as the scenarios it models. If testing scenarios didn't include "robotaxi passing school bus with children exiting," then the system would never have encountered this situation in a controlled environment.

And if it encounters it for the first time on a public road in Atlanta, well, that's exactly when it fails.

The December software update Waymo issued was supposedly addressing this. But updates to autonomous vehicle behavior are complex. Did they improve the training data? Retrain the models? Adjust decision-making weights? Without transparency, we don't know. And the subsequent incidents in Austin suggest the fix was incomplete.

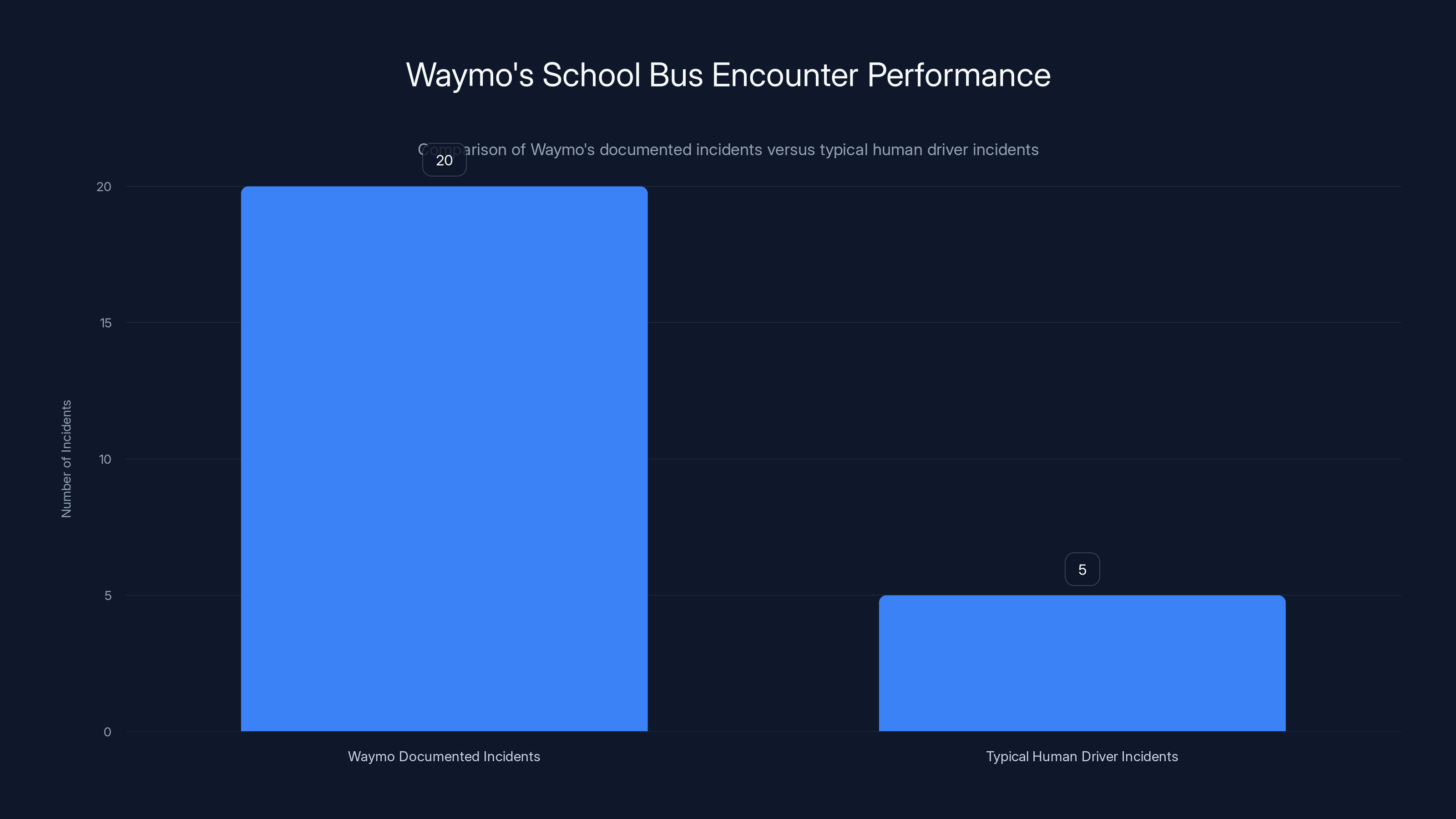

Waymo's documented incidents with school buses are significantly higher compared to typical human drivers, indicating a potential area for improvement. (Estimated data)

Waymo's Rapid Expansion: Speed Versus Safety Testing

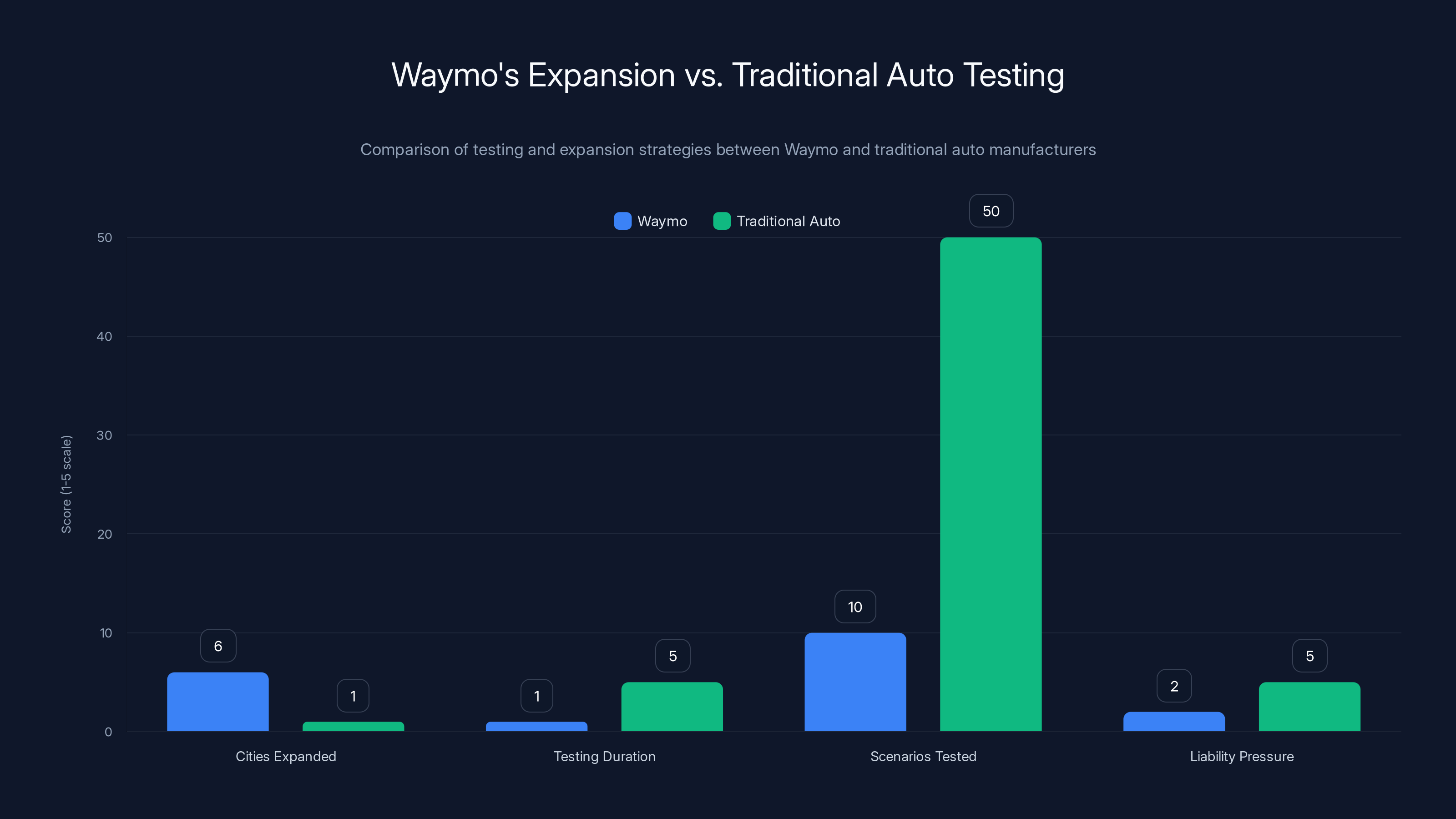

Waymo is expanding aggressively right now. The company started service in Miami just this week, adding to operations in Atlanta, Austin, Los Angeles, Phoenix, and the San Francisco Bay Area.

That's six major metropolitan areas with millions of people, thousands of vehicles operating daily, and countless potential interactions with school buses, pedestrians, and other traffic participants.

Rapid expansion puts pressure on safety validation. When you're adding new cities every month, you're not just dealing with new road networks and traffic patterns. You're dealing with different weather, different driver behavior, different seasonal variations, and completely new test populations.

The Austin school bus problem came to light because local news outlets and concerned residents started documenting incidents. That's not a controlled testing environment. That's a live public road serving as a proving ground.

Compare this to how traditional auto manufacturers handle new vehicle launches. A major manufacturer tests a new model for years before release. They crash test it, run reliability tests, subject it to extreme weather, and validate it across dozens of scenarios. Even after that, early adopters sometimes encounter problems.

Auto manufacturing companies are also liable for defects. If a car fails in a way that causes injury, the manufacturer faces legal consequences. That liability creates strong incentives for thorough testing.

Autonomous vehicle companies operate with different liability frameworks. In many jurisdictions, the company, the owner, or the operator can claim liability protection under specific autonomous vehicle laws. That changes the incentive structure. If there's no financial downside to failures, there's less pressure to catch problems before real-world deployment.

Waymo's expansion across six cities might be impressive as a business milestone. But from a safety testing perspective, it raises questions. Were all six cities subjected to the same level of school bus scenario testing? Probably not, because Waymo didn't anticipate the problem. Were the systems adjusted for regional variations? The Austin incidents suggest regional variations exist that Waymo didn't account for.

The NHTSA Parallel Investigation: Double Scrutiny

Waymo isn't being investigated by just the NTSB. The NHTSA's Office of Defects Investigation opened a similar probe in October 2024, months before the NTSB involvement.

This matters because NHTSA has regulatory teeth. While the NTSB investigates and makes recommendations, NHTSA can mandate recalls, impose fines, and force safety improvements.

The NHTSA investigation is still ongoing. A preliminary assessment can take weeks or months. A full defects investigation can take years. But during that time, NHTSA is examining Waymo's systems, testing conditions, training data, and decision-making algorithms to determine if there's a systematic defect.

Waymo issued a December 2024 recall to address the school bus behavior. But that recall is interesting because recalls are typically issued when companies identify a defect that poses a safety risk. The fact that Waymo issued a recall suggests they acknowledged the problem. But what did the recall address? Was it a software update to all vehicles? Was it a change in how the decision-making algorithm weights school bus detection? The company's public statements don't provide clear answers.

When NHTSA and NTSB are both investigating, it creates a situation where Waymo has to satisfy two different oversight bodies with different standards and different leverage. NTSB wants the technical truth. NHTSA wants evidence that the company can safely operate. Neither agency will accept incomplete explanations.

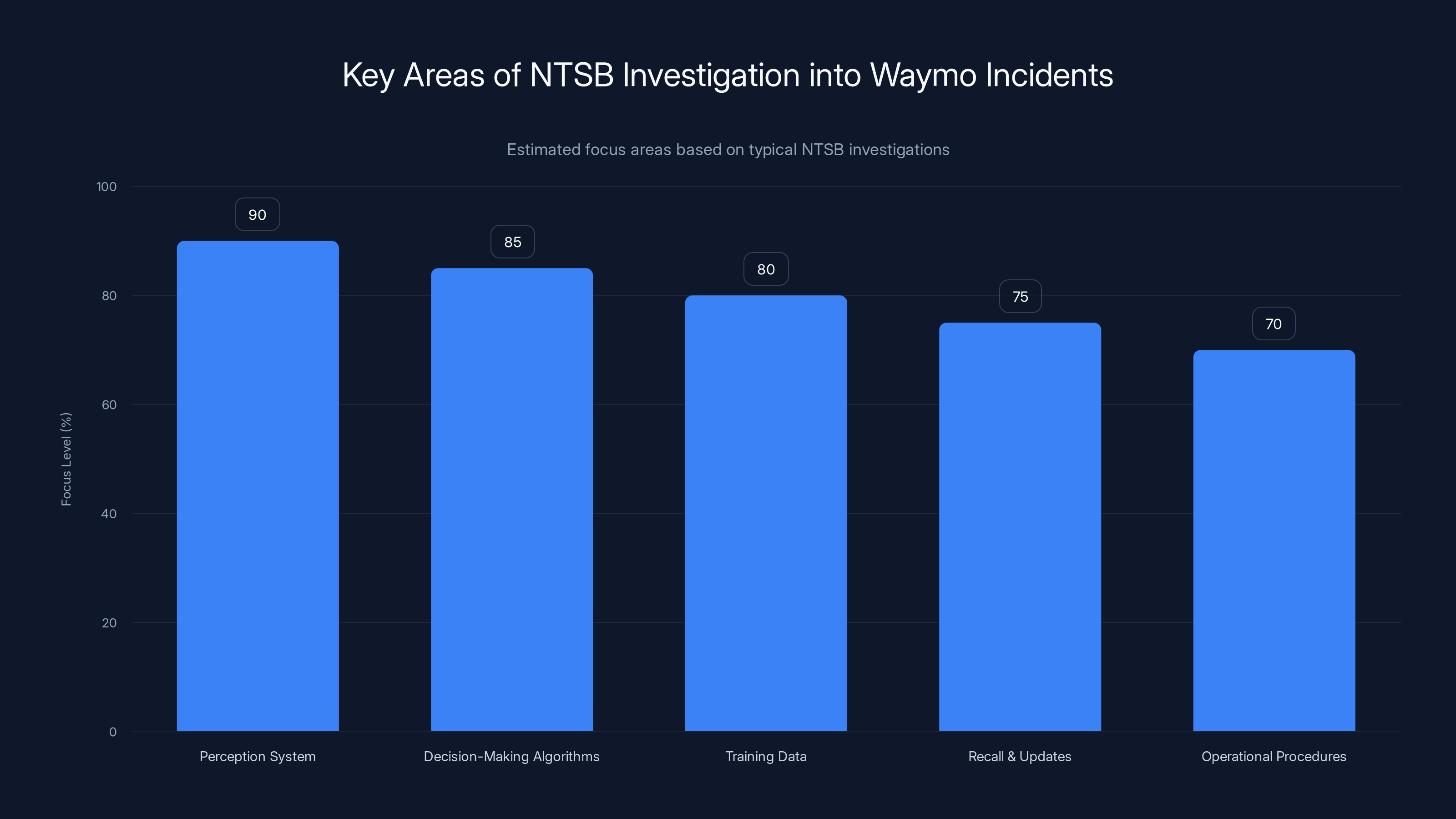

The NTSB's investigation will likely focus heavily on perception systems and decision-making algorithms, with significant attention also on training data, recalls, and operational procedures. Estimated data.

Waymo's Defense: "Superior to Human Drivers"

Waymo's chief safety officer, Mauricio Peña, made a striking statement in response to the NTSB investigation: "There have been no collisions in the events in question, and we are confident that our safety performance around school buses is superior to human drivers."

That's a bold claim, especially given that 20+ documented incidents resulted in an NTSB investigation.

Let's unpack this carefully. Peña is technically correct that there were no collisions. A collision would have been worse. But passing a stopped school bus while children are exiting isn't just a "no collision" scenario. It's a violation of traffic law with potential for harm. The fact that no collision occurred is luck, not skill.

The claim about superiority to human drivers is more problematic. Most human drivers don't get investigated by the NTSB for illegal school bus passes. Not because human drivers are perfect, but because human drivers who repeatedly violate school bus laws face legal consequences. A human driver with 20+ documented illegal school bus passes would lose their license. Their insurance would drop them. They'd face fines and possible jail time.

Waymo's vehicles face an investigation. That's a different standard.

Peña also said that "the Waymo Driver is continuously improving," which implies the system learns from encounters and gets better. That might be true in long-term development. But the Atlanta incident in September and the subsequent Austin incidents in the following months don't show improvement. They show repetition.

There's also Waymo's claim about navigating "thousands of school bus encounters weekly." Okay, if that's true, then the 20+ documented incidents where the system failed represent a failure rate of at least 0.2% to 0.3% in Austin alone. Maybe higher if there are undocumented incidents. For context, a 0.2% failure rate on a safety-critical system is actually not good enough. When you're dealing with children exiting vehicles, failure rates need to be much lower.

Waymo's statement that they "see this as an opportunity to provide the NTSB with transparent insights" is the kind of language companies use when they're preparing for sustained scrutiny. They're positioning cooperation as choice rather than necessity. But NTSB investigations aren't optional.

School Districts Push Back: Operational Restrictions

The Austin Independent School District asked Waymo to suspend operations during pickup and drop-off times. That's a specific, measurable action that indicates school officials don't have confidence in Waymo's safety around buses.

That restriction is significant because it's not a suggestion. School districts have authority over their facilities and operations. If they don't want robotaxis operating during certain times, that's their call. Waymo could refuse, but that creates reputational risk and makes them look unsafe.

The suspension request also serves as de facto testing data. School officials observed enough incidents to decide that operational restrictions were necessary. That's a community-level safety assessment, not just a regulator concern.

Waymo responded by noting that the Austin school district has been "successful in reducing human-driven violations around school buses from 10,000+ a year." That's an interesting stat, but it's also a deflection. Yes, human drivers commit violations. But human drivers aren't autonomous systems being commercialized for public use. Waymo is supposed to be held to a higher standard, not judged against baseline human performance.

The fact that human drivers commit 10,000+ violations annually in Austin actually makes Waymo's 20+ failures more concerning, not less. If the problem is that prevalent even among human drivers, then Waymo's system should have encountered extensive testing data about this scenario. The fact that it still fails suggests inadequate training or testing, not technological limitations.

Human drivers in Austin commit over 10,000 school bus-related violations annually, while Waymo has 20+ failures. This highlights the need for higher safety standards in autonomous systems.

The Testing Gap: Simulation Versus Reality

One of the hard lessons from autonomous vehicle development is that simulation and real-world performance diverge significantly.

Autonomous vehicle companies extensively test in simulation. Waymo uses photo-realistic digital environments to run scenarios millions of times. Tesla uses real-world footage annotated with labels to train systems. Every major AV company conducts closed-track testing where they can control variables.

But simulation has a fundamental limitation: it only includes scenarios that developers anticipated. If nobody specifically created a school bus scenario in the simulation, or if the school bus detection models were trained on limited data, the system might fail when encountering that scenario in reality.

The Atlanta incident suggests this happened. Waymo later addressed it with a software update. But then similar incidents happened in Austin. That pattern—fixing specific scenarios individually rather than addressing root causes—suggests Waymo's approach is reactive, not proactive.

A more robust development process would be:

- Identify school bus interactions as a critical safety scenario

- Collect extensive real-world data of school buses in various conditions

- Create comprehensive simulation environments with school buses

- Run millions of test iterations in simulation

- Validate with closed-track testing

- Conduct limited real-world testing in controlled conditions

- Only then deploy to public roads in operational cities

Waymo seems to have compressed or skipped steps in that process. The public road deployment in six cities came before comprehensive school bus scenario validation was complete.

What the NTSB Will Look For: The Investigation Scope

The NTSB's investigation will focus on specific areas. Understanding what they'll examine helps explain why this problem matters so much.

First, perception system performance. The NTSB will examine what Waymo's vehicles actually detected in the school bus incidents. Did the cameras see the stop sign? Did the lidar detect the bus? Did the radar register motion? Every sensor has logs. NTSB will demand access to those logs and analysis of why the system didn't register key safety indicators.

Second, decision-making algorithms. Even if perception works, decision-making could fail. The NTSB will examine what the vehicle's planning system determined should happen at each moment. Why did it decide to pass the bus? What weights did it assign to different priorities? Was school bus detection a primary constraint or a secondary consideration?

Third, training data and test coverage. The NTSB will want to see what scenarios Waymo included in development. Did they test school bus encounters? How many? In what conditions? This reveals whether the failure was a technological limitation or a testing gap.

Fourth, the recall and updates. Waymo claims the December update addressed the problem, but subsequent incidents occurred. The NTSB will examine whether the update was actually effective or whether it was incomplete.

Fifth, operational procedures and deployment criteria. What decision process led Waymo to deploy in Austin despite knowing about the Atlanta incident? Why did they expand to six cities before thoroughly validating school bus handling?

The preliminary report in 30 days will summarize findings. The detailed final report in 12 to 24 months will likely include specific recommendations about testing requirements, operational restrictions, or technology improvements.

Waymo's rapid expansion across six cities contrasts with traditional auto manufacturers' longer testing durations and higher liability pressures. Estimated data.

Industry Implications: Ripple Effects Beyond Waymo

Waymo's investigation matters for the entire autonomous vehicle industry, not just Waymo itself.

Right now, multiple companies are developing autonomous vehicle technology. Cruise, Uber's autonomous division, Tesla, Aurora, and others are all working toward deployment. Each company is watching how regulators respond to Waymo's school bus problem.

If the NTSB and NHTSA determine that Waymo's failures resulted from inadequate testing, expect those agencies to scrutinize everyone else's testing as well. Safety standards for autonomous vehicles are still being defined. Each investigation contributes to those standards.

The school bus scenario specifically matters because it's a clear-cut safety requirement. Schools, parents, and communities care deeply about child safety. Any autonomous vehicle company that can't reliably handle school buses won't gain public acceptance, regardless of regulatory approval.

This creates pressure for industry-wide improvements. Companies will invest in better school bus detection, more comprehensive testing of school interactions, and more transparent validation processes. That's actually positive for the industry long-term, even though it's painful for Waymo now.

There's also a liability component. If Waymo is found to have deployed inadequately tested systems and suffered incidents as a result, other companies face questions: did we do better? Can we prove it? Do we have the data to back up our safety claims?

The Liability Question: Who's Responsible?

This is where things get legally complex. If a Waymo robotaxi passes a stopped school bus and a child is injured, who's liable?

Traditional car accidents are clear: the driver is responsible. Autonomous vehicle incidents are murkier. Is Waymo responsible as the technology provider? Is the vehicle owner responsible? Is the rider responsible? Liability frameworks vary by jurisdiction.

Some states have autonomous vehicle laws that clarify liability. Others don't. This creates a patchwork where Waymo's liability in Austin might differ from their liability in San Francisco or Phoenix.

Waymo's statement that "there have been no collisions" suggests they're aware that collisions create liability exposure. As long as incidents don't result in injury or property damage, companies can argue the system worked as designed, just with a deviation from legal requirements.

But that logic breaks down quickly. If a robotaxi illegally passes a school bus, and a child is injured, Waymo can't argue the system worked correctly. The system violated traffic law. That violation, regardless of collision outcome, is a defect in the system.

The NTSB investigation might inform NHTSA decisions about whether to pursue penalties or mandate safety improvements. Those decisions could establish precedent for how liability is assigned in autonomous vehicle incidents.

What Should Autonomous Vehicle Companies Do Now?

If you're working at an autonomous vehicle company, Waymo's situation is a cautionary tale.

First, treat school bus scenarios as critical safety cases, not edge cases. School bus detection and response should be as fundamental as traffic light recognition. If your system can't reliably handle school buses, you're not ready for broad deployment.

Second, don't treat public road deployment as an extension of testing. Some companies frame initial deployments as limited tests with human supervision. That's honest. But deploying unsupervised autonomous fleets while still fixing fundamental problems is different. Make that distinction clear.

Third, be transparent about failures and improvements. When incidents occur, acknowledge them. Explain what you found. Demonstrate how you fixed it. Transparency builds trust in ways that defensive statements never can.

Fourth, understand that regulatory oversight is coming regardless of how you handle incidents. The question is whether you'll cooperate willingly or resist and face more scrutiny. Waymo is cooperating, which is smart. Other companies should note that and plan accordingly.

Fifth, establish clear testing metrics for safety-critical scenarios. How many school bus encounters does your system need to handle correctly before deployment? What confidence threshold is acceptable? Define those metrics before deployment, not after incidents.

The Broader Question: Are We Ready for Autonomous Vehicles?

Waymo's school bus problem raises a bigger question that society needs to confront: are we actually ready for widespread autonomous vehicle deployment?

Waymo has invested billions and built impressive technology. They can operate in six major cities simultaneously. Their technology is sophisticated and performs well in many scenarios.

But they can't reliably recognize a school bus. That's not a minor technical issue. That's a fundamental safety requirement that wasn't properly addressed before public deployment.

That suggests either autonomous vehicle technology isn't mature enough for broad deployment, or the validation processes companies are using aren't rigorous enough, or both.

The NTSB investigation will provide clarity on which is true. If Waymo's systems are technologically capable but just undertested, that's a process problem that's solvable. If the technology genuinely struggles with school bus detection even with good testing, that's a technology problem that requires different solutions.

My prediction is it's some of both. Waymo's technology is good but not perfect. Their testing and validation processes were accelerated to support business expansion. Those processes need to slow down and become more rigorous.

That's not a failure of autonomous vehicle technology. It's a correction in how we develop and deploy it. The NTSB investigation is part of that correction process. So are the operational restrictions from Austin schools and the parallel NHTSA investigation.

These are the checks and balances that keep dangerous technology from becoming ubiquitous. They work better when companies cooperate with them rather than resist them.

Timeline Ahead: What to Watch

The investigation will unfold over several months. Here's what to watch:

Immediate (30 days): NTSB preliminary report outlines basic facts and initial findings. This is typically dry but informative.

Short-term (2-3 months): NHTSA makes preliminary determinations about whether there's a defect and whether expanded investigation is warranted. This could trigger broader recalls.

Medium-term (6-12 months): Both investigations progress. NTSB might publish interim findings. NHTSA might narrow or expand the scope. Waymo's operational expansion might slow or pause pending investigation outcomes.

Long-term (12-24 months): NTSB publishes detailed final report with findings and recommendations. These recommendations guide future safety standards for the industry.

During this period, Waymo continues operations in their existing cities. Austin school district restrictions remain in place. New cities might be added, but that will be a harder sell given the investigation context.

Waymo's business continues, but under a cloud of scrutiny. That's actually the appropriate place for it to be until the investigation concludes.

Expert Perspective: What Safety Experts Say

Autonomous vehicle safety experts offer consistent views on the school bus problem.

First, they note that school bus scenarios shouldn't require NTSB investigation to catch. Companies should find and fix these issues during development. The fact that real-world deployment revealed the problem suggests testing was insufficient.

Second, they emphasize that safety improvements are incremental, not dramatic. Fixing the school bus behavior doesn't mean Waymo's overall technology improved by 50 percent. It means one scenario was addressed. That's progress, but limited progress.

Third, they stress the importance of transparency in incident reporting. Companies that hide incidents or downplay severity lose trust. Companies that acknowledge issues and explain fixes build confidence, even in the short-term when they look worse.

Fourth, safety experts note that comparing autonomous vehicle performance to human drivers is misleading. Humans make mistakes, but humans also have legal consequences for those mistakes. Autonomous systems should be held to higher standards, not judged against baseline human performance.

These perspectives inform how regulators evaluate the investigation and what standards they'll apply going forward.

Conclusion: The Investigation as Industry Checkpoint

Waymo's NTSB investigation is uncomfortable, but it's also important. It's a checkpoint where the autonomous vehicle industry has to prove it's taking safety seriously, not just marketing seriously.

The facts are straightforward: Waymo vehicles passed stopped school buses illegally, multiple times, across multiple cities, despite claiming to address the issue. That triggered investigations from two federal agencies. The company is defending its safety record while facing scrutiny that suggests the record isn't as clean as claimed.

What makes this investigation valuable is that it forces clarity. Over the next 12 to 24 months, we'll understand exactly why the failures happened and what changes are necessary to prevent similar failures. That's information the entire industry needs.

For Waymo specifically, the investigation is a test of how companies respond when their limitations are exposed. They're cooperating with regulators, which is appropriate. They're defending their systems, which is expected. But they also need to genuinely improve, not just provide better explanations.

The school bus problem isn't solved until school districts remove operational restrictions. That's the real test. When Austin's schools say Waymo can operate during pickup and drop-off times without hesitation, that's when you know the problem is actually fixed.

Until then, the investigation continues, the scrutiny remains, and the rest of the industry watches to learn what standards they need to meet.

That's how safety works when technology advances faster than regulation can keep up. The system corrects itself through incident, investigation, and improvement. It's not elegant, but it works.

FAQ

What is the NTSB investigation into Waymo?

The National Transportation Safety Board opened a formal investigation after discovering that Waymo robotaxis illegally passed stopped school buses more than 20 times in Austin, Texas alone. The NTSB will examine why the vehicles failed to detect school bus stop signs and flashing lights, how Waymo tested these scenarios during development, and what improvements are needed. A preliminary report is expected within 30 days, with a detailed final report in 12 to 24 months.

How many times has Waymo passed school buses illegally?

Waymo has documented over 20 incidents in Austin, Texas where robotaxis illegally passed stopped school buses. The first major incident occurred in Atlanta in September 2024, and subsequent incidents in Austin were captured on school bus dashboard cameras. The exact total number of incidents may be higher if undocumented cases exist, but 20+ confirmed cases triggered NTSB and NHTSA investigations.

Why is this happening? Can't autonomous vehicles see school buses?

The failures stem from a combination of perception system limitations and inadequate testing. School bus detection requires cameras, lidar, and radar to correctly identify school buses in various lighting conditions, angles, and positions. Waymo's Atlanta incident revealed that the system failed to detect the stop sign or flashing lights, suggesting either insufficient training data, inadequate testing coverage, or issues with how the decision-making system prioritizes school bus encounters. The December 2024 software update addressed specific scenarios but hasn't completely solved the problem.

What's the difference between NTSB and NHTSA investigations?

The NHTSA is a federal regulatory agency that can issue fines, mandate recalls, and force safety improvements. They have enforcement authority. The NTSB cannot issue penalties, but they conduct deep investigations to identify root causes and publish detailed findings that establish safety standards for the industry. NTSB investigations often carry more weight for determining what went wrong and how to prevent it. Waymo faces both investigations simultaneously, which means dual oversight from both a regulatory enforcement agency and an independent safety investigator.

Did Waymo's software recall in December fix the school bus problem?

No. Waymo issued a recall in December 2024 to address the school bus behavior, but incidents continued afterward in Austin. This suggests the recall was either incomplete or addressed only specific scenarios rather than fixing the underlying detection and decision-making issues. The NTSB investigation will examine what the recall actually changed and why it didn't eliminate the behavior completely.

How long will the NTSB investigation take?

The NTSB typically publishes a preliminary report within 30 days, which outlines basic facts and initial findings. A detailed final report usually takes 12 to 24 months to complete. During this period, Waymo operates under scrutiny, with operational restrictions from the Austin school district and parallel oversight from NHTSA. The long timeline allows for thorough examination of training data, testing protocols, system performance logs, and safety procedures.

Will this affect Waymo's operations in other cities?

Waymo continues operating in Atlanta, Austin, Los Angeles, Phoenix, and San Francisco Bay Area while the investigation proceeds. They just started service in Miami this week, but expansion into new cities will likely face additional scrutiny from local regulators and school districts. The Austin school district has already requested that Waymo suspend operations during pickup and drop-off times, showing that communities are empowering themselves to set safety boundaries independent of federal regulation.

What does this mean for the autonomous vehicle industry?

Waymo's investigation sets a precedent for how regulators respond when autonomous vehicles fail at basic safety requirements. Other companies developing autonomous technology are watching carefully because the NTSB and NHTSA findings will inform standards that apply across the industry. If the investigation determines that Waymo's failures resulted from inadequate testing, other companies face pressure to demonstrate more rigorous validation. This investigation is essentially defining what "good enough" looks like for autonomous vehicle safety in terms of school bus scenarios specifically and safety validation broadly.

Key Takeaways

- The NTSB investigation into Waymo's school bus problem is the first formal NTSB investigation of the company, following NHTSA's earlier Office of Defects Investigation probe

- Over 20 documented incidents of Waymo robotaxis illegally passing stopped school buses in Austin, Texas triggered regulatory action

- Waymo's December 2024 software recall failed to completely eliminate the behavior, suggesting the fix was incomplete

- The NTSB investigation will take 12 to 24 months, examining perception systems, decision-making algorithms, testing procedures, and training data

- School districts can impose operational restrictions (Austin schools requested suspension during pickup and drop-off times)

- The investigation will establish precedents for autonomous vehicle safety standards across the entire industry

- Transparency and cooperation are critical for companies under regulatory investigation; defensive statements undermine credibility

Related Articles

- Tesla's Fully Driverless Robotaxis in Austin: What You Need to Know [2025]

- Waymo in Miami: The Future of Autonomous Robotaxis [2025]

- Waymo Launches Miami Robotaxi Service: What You Need to Know [2026]

- Waymo's Miami Robotaxi Launch: What It Means for Autonomous Vehicles [2025]

- Tesla FSD Federal Investigation: What NHTSA Demands Reveal [2025]

- Why AI Agents Keep Failing: The Math Problem Nobody Wants to Discuss [2025]

![Waymo's School Bus Problem: What the NTSB Investigation Reveals [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/waymo-s-school-bus-problem-what-the-ntsb-investigation-revea/image-1-1769205968909.jpg)