Tesla's $243M Autopilot Verdict Stands: What the Ruling Means [2025]

Introduction: A Landmark Decision That Won't Go Away

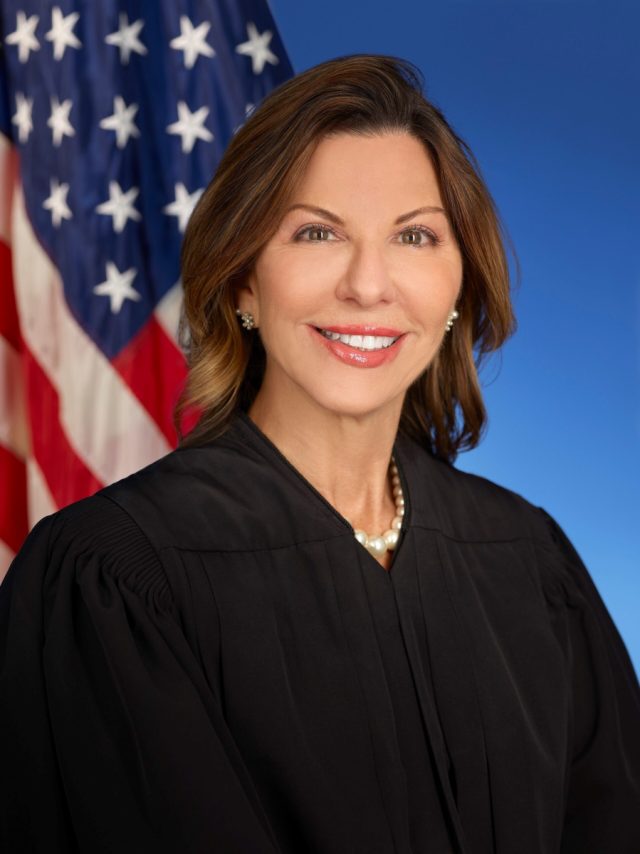

In February 2026, a federal judge delivered news that Tesla didn't want to hear. The company's attempt to overturn a $243 million verdict related to a fatal Autopilot crash went nowhere. Judge Beth Bloom's decision was blunt: Tesla's arguments were recycled, already considered, and ultimately unconvincing, as reported by CNBC.

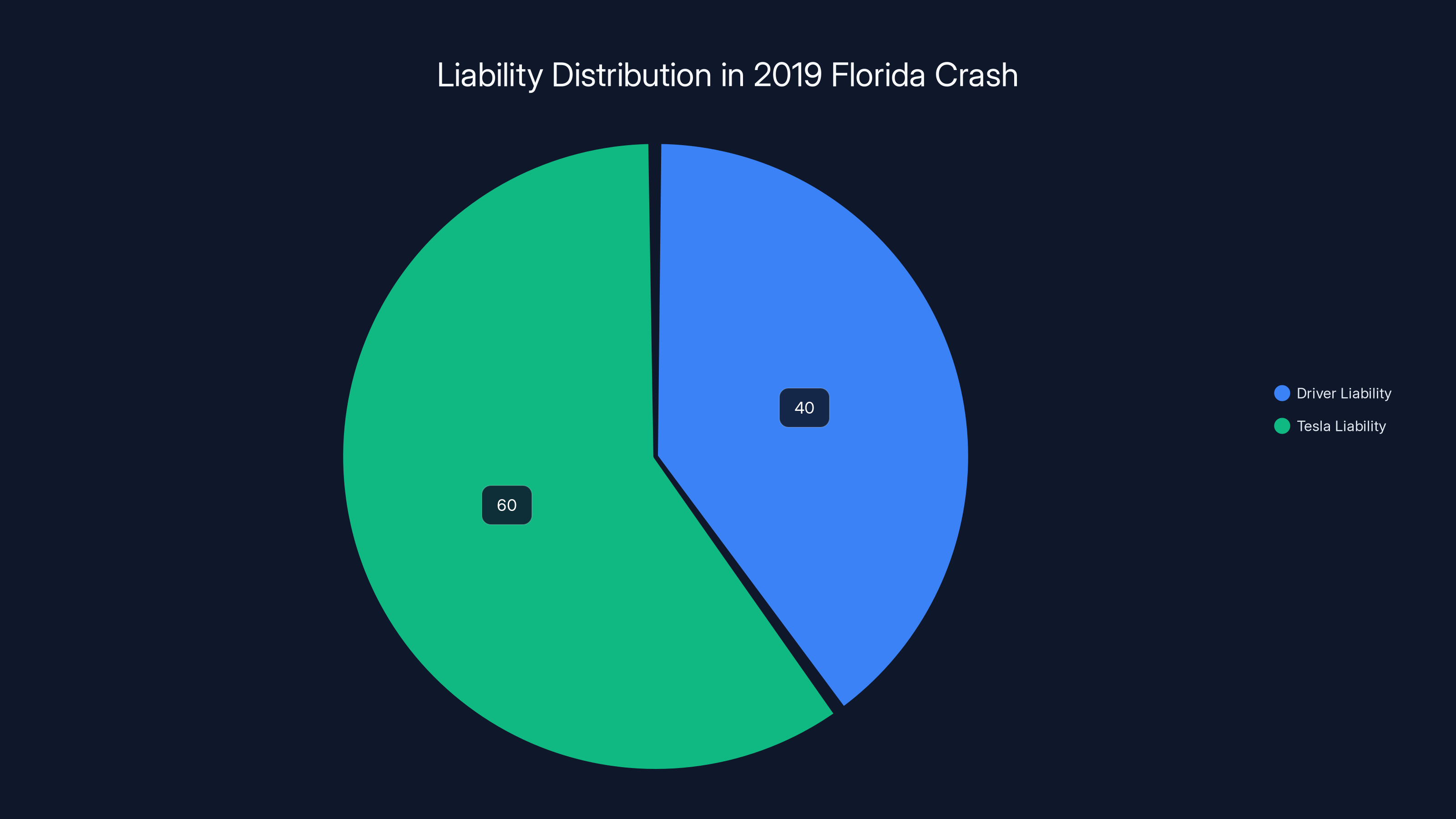

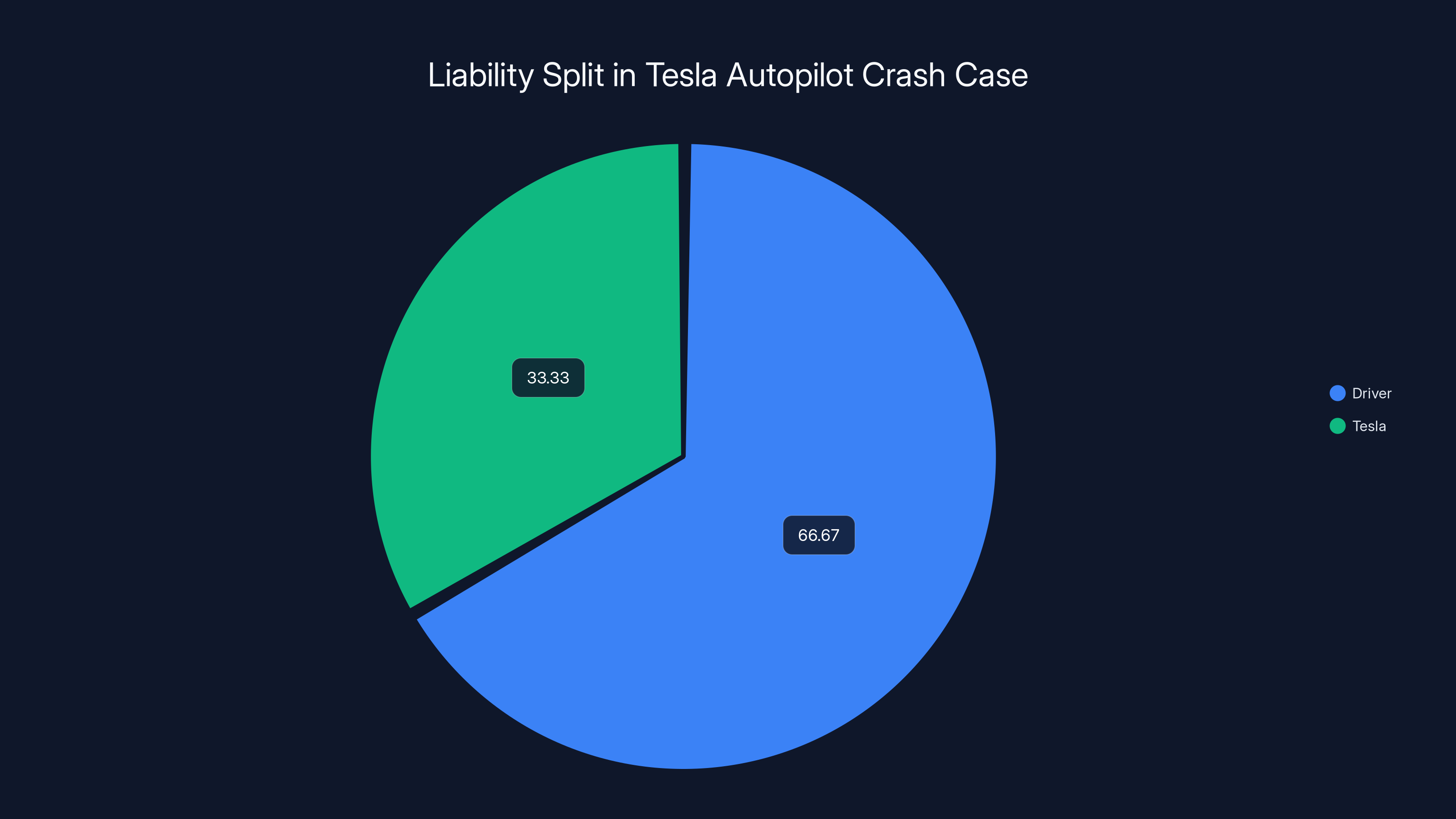

Here's what actually happened. Back in August 2025, a jury found that Tesla shared responsibility for a 2019 crash in Florida that killed 27-year-old Naibel Benavides and critically injured Dillon Angulo. The jury split liability two-thirds to the driver, one-third to Tesla. Then came the kicker: punitive damages were assessed against Tesla alone. This wasn't a minor liability ruling. This was a statement that Tesla's marketing, engineering, or both, had crossed a line, as detailed by Electrek.

Now, with the appeal attempt denied, the verdict stands. And that matters far beyond one lawsuit.

The ruling carries massive implications. It signals to courts nationwide how they should think about autonomous driving features. It suggests that companies can't hide behind driver responsibility when their marketing or technology creates dangerous expectations. It opens the door to future litigation. And it puts pressure on Tesla and every automaker to take a hard look at how they label, test, and deploy driver assistance systems.

Why does this verdict resonate across the industry? Because the legal standard being set here isn't about Tesla alone. It's about whether companies building semi-autonomous systems can be held liable when those systems contribute to crashes. For years, automakers claimed driver assistance features were tools, not replacements for human drivers. The jury essentially said: if your marketing suggests otherwise, or if your technology encourages bad behavior, you share the blame.

This deep dive explores what the verdict actually means, why it matters beyond Tesla, and where autonomous driving liability is heading. We'll look at the technical details of Autopilot, the legal implications, industry responses, and what regulators are likely to do next. By the end, you'll understand why one jury verdict in Florida might reshape how self-driving cars get built and sold.

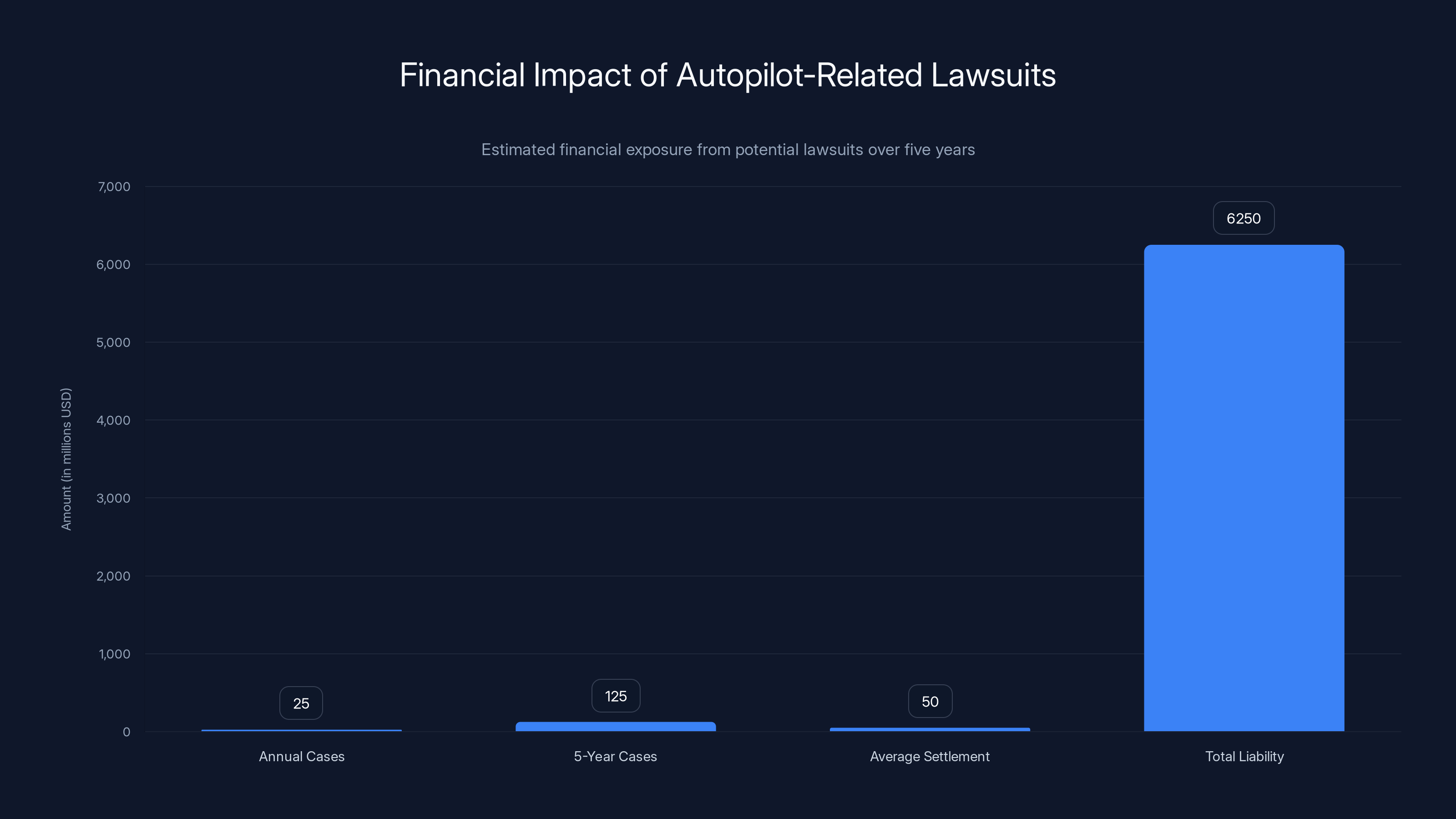

Estimated data suggests Tesla could face

TL; DR

- Judge denied Tesla's appeal: The $243M verdict stands with no new arguments or controlling law to overturn it

- Liability split: 2/3 driver, 1/3 Tesla: Jury found Tesla partially responsible for fatal 2019 Autopilot crash

- Punitive damages significant: Only Tesla faced punitive damages, signaling intentional negligence or recklessness

- Marketing matters legally: The verdict suggests liability depends partly on how features are marketed and labeled

- Industry implications major: Other automakers now face elevated risk in similar litigation involving driver assistance systems

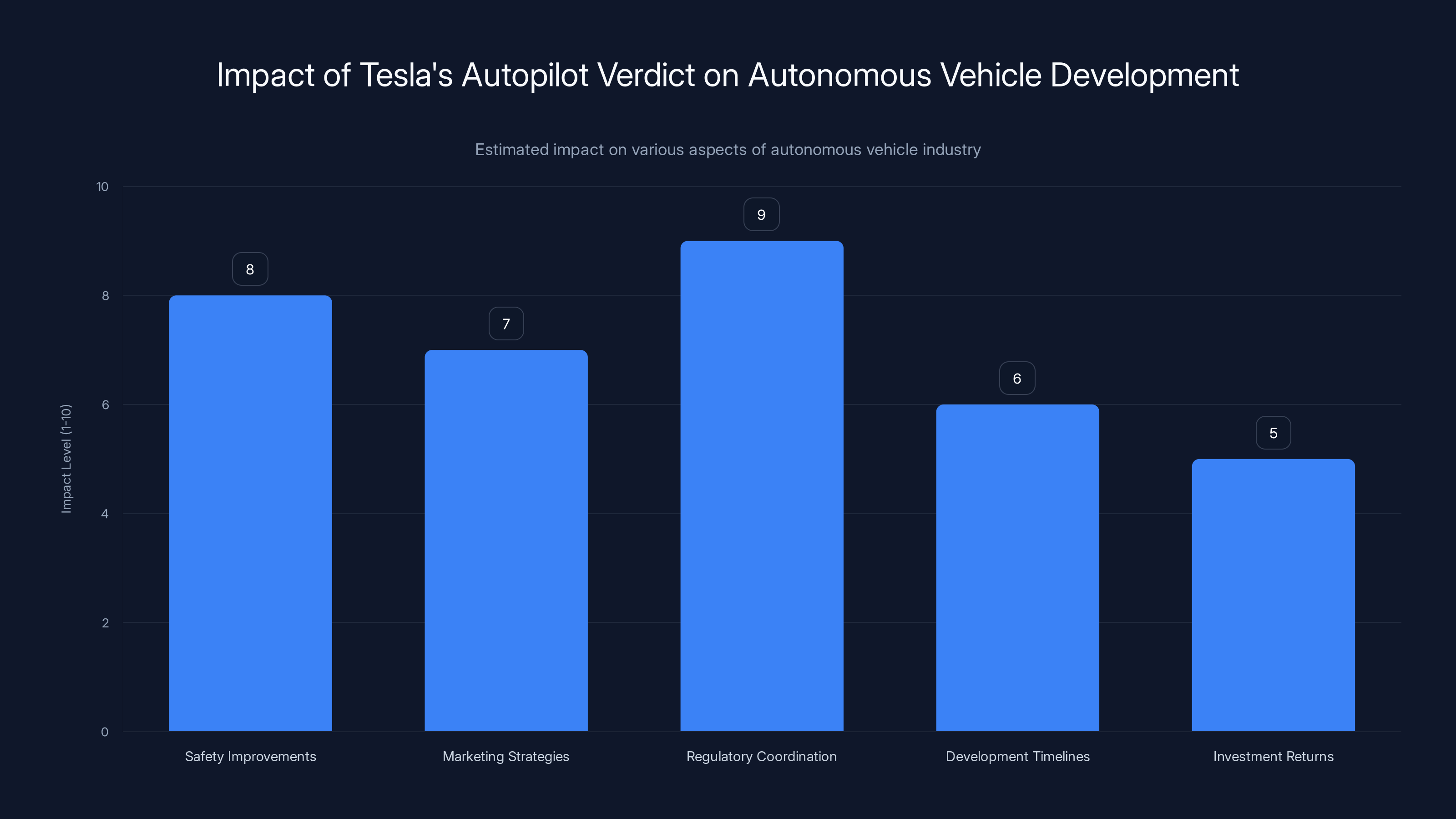

The Tesla Autopilot verdict is expected to significantly influence safety improvements and regulatory coordination in the autonomous vehicle industry. Estimated data.

The 2019 Florida Crash: Understanding the Underlying Facts

Before diving into legal arguments, let's understand what actually happened on that road in Florida three years ago.

In May 2019, a Tesla Model 3 traveling on a divided highway in Delray Beach, Florida, crashed into a concrete barrier. The vehicle was operating under Autopilot. The crash was severe. Naibel Benavides, the driver, was killed. Dillon Angulo, a passenger, suffered critical injuries.

The immediate question was simple: Why did the car hit the barrier? Was the driver negligent? Was the car malfunctioning? Was the feature itself dangerously designed? Or was it some combination of all three?

Investigation revealed the driver had engaged Autopilot on a divided highway where the feature wasn't designed to operate safely. The road conditions included a concrete barrier dividing lanes. The vehicle didn't stop or avoid the barrier. Instead, it crashed directly into it at highway speed.

But here's where it gets legally interesting. The jury didn't simply blame the driver for misusing the feature. They assigned significant liability to Tesla. Why? The evidence suggested that Autopilot's design and marketing created dangerous conditions. The feature lacked adequate safeguards to prevent misuse. The marketing materials suggested capabilities the system didn't reliably possess, as noted by OpenTools.

This distinction is crucial. Many driver assistance crashes result from driver error alone. Juries assign 100% liability to the driver and move on. This jury didn't do that. They found Tesla had contributed materially to the conditions that led to the crash.

The evidence presented to the jury included data about Autopilot's actual capabilities versus its marketed capabilities. It included information about similar crashes. It included expert testimony about whether the system was adequately designed to prevent misuse on divided highways. And it included an examination of how Tesla marketed Autopilot to consumers.

Judge Bloom's Decision: Why the Appeal Failed

Tesla's legal team didn't give up after the verdict. They filed a motion asking Judge Beth Bloom to overturn the jury's decision. This is standard procedure. Most verdicts get challenged. Most challenges fail.

But Judge Bloom's language in denying the motion reveals something important about how courts are viewing these cases. She didn't just say no. She pointed out that Tesla was re-litigating arguments it had already lost.

Quote from the decision: "The grounds for relief that Tesla relies upon are virtually the same as those Tesla put forth previously during the course of trial and in their briefings on summary judgment — arguments that were already considered and rejected."

That's a judicial face-palm. Tesla wasn't bringing new evidence. It wasn't presenting new legal theories. It was essentially saying the same things to a different decision-maker, hoping for a different outcome.

Judge Bloom continued: "Furthermore, Tesla does not present additional arguments or controlling law that persuades this Court to alter its earlier decisions or the jury verdict."

Translated: You've already lost this argument. You're losing it again. Moving on.

This matters because it signals that courts aren't sympathetic to Tesla's position. The judge clearly reviewed the evidence and arguments thoroughly. She clearly believed the jury verdict was reasonable given the evidence. And she clearly wasn't willing to substitute her judgment for the jury's.

In legal terms, this means the burden on appeal is extremely high. Tesla would need to show that no reasonable jury could have reached this verdict. They'd need to demonstrate legal error by the judge. They'd need something concrete and compelling.

They had none of that.

The jury assigned 60% liability to Tesla for the crash, highlighting issues with Autopilot's design and marketing. Estimated data based on case insights.

The Liability Split: Why One-Third Tesla Matters

The jury assigned two-thirds liability to the driver and one-third to Tesla. That ratio deserves close attention.

In crash liability cases, juries are instructed to assign percentages based on comparative negligence. Each party's conduct is evaluated. The percentage assigned reflects that party's contribution to the accident.

Two-thirds driver, one-third Tesla suggests the jury believed the driver bore primary responsibility for misusing the feature. That makes sense. The driver engaged Autopilot where it wasn't designed. The driver failed to maintain control. The driver didn't respond when they should have.

But one-third Tesla? That's the interesting part. The jury determined that Tesla's actions, inactions, or system design contributed materially to the crash. What could justify that assessment?

Several things likely came into play. First, Autopilot's failure detection and disengagement systems didn't prevent the dangerous scenario. Second, the marketing of Autopilot may have created unrealistic expectations about the feature's capabilities. Third, Tesla didn't implement adequate safeguards to prevent misuse on divided highways or in the specific conditions of this crash, as highlighted by MLQ AI.

Consider this analytically. If Autopilot had a feature that detected divided highways and refused to engage, this crash might never have happened. If the marketing clearly stated "This feature will disengage if you're not actively monitoring the road," driver behavior might have been different. If the system included geographic or speed-based limitations, the risk would have been lower.

Tesla implemented none of these measures. That's not necessarily negligent in isolation, but combined with other factors—the marketing, the lack of safeguards, the knowledge of similar incidents—it crosses a threshold.

The one-third assignment reflects a sophisticated legal analysis. The jury didn't say Tesla was equally responsible. They said the driver was clearly the primary actor. But they also said Tesla's conduct was material enough to warrant significant liability.

Punitive Damages: The Verdict Within the Verdict

Here's the part that really stung Tesla: punitive damages were assessed against Tesla but not against the driver.

Punitive damages aren't meant to compensate victims. They're meant to punish defendants for egregious conduct and deter similar conduct in the future. They're only awarded when a defendant's actions show recklessness, intentional misconduct, or gross negligence.

The jury's decision to assess punitive damages against Tesla alone is significant. It suggests the jury believed Tesla's conduct went beyond simple negligence. It suggests intentionality or at least reckless disregard for safety.

What could justify that conclusion? The evidence likely included communications about Autopilot capabilities. It likely included knowledge of previous incidents or complaints. It likely included analysis of whether Tesla knew the marketing was overstating the system's abilities, as discussed by New York Post.

Punitive damages verdicts are often reduced on appeal. Judges frequently find that juries were swayed by emotion rather than law. But Judge Bloom didn't reduce them. She let them stand. That signals the trial evidence supported the damages from a legal perspective.

For Tesla shareholders and executives, this is particularly consequential. Punitive damages suggest a pattern of problematic conduct, not just one bad decision. They suggest systemic issues in how the company markets and deploys its autonomous features.

Indeed, the fact that punitive damages were assessed against the corporate entity, not the driver, reinforces the court's view that this was about organizational behavior, not individual error.

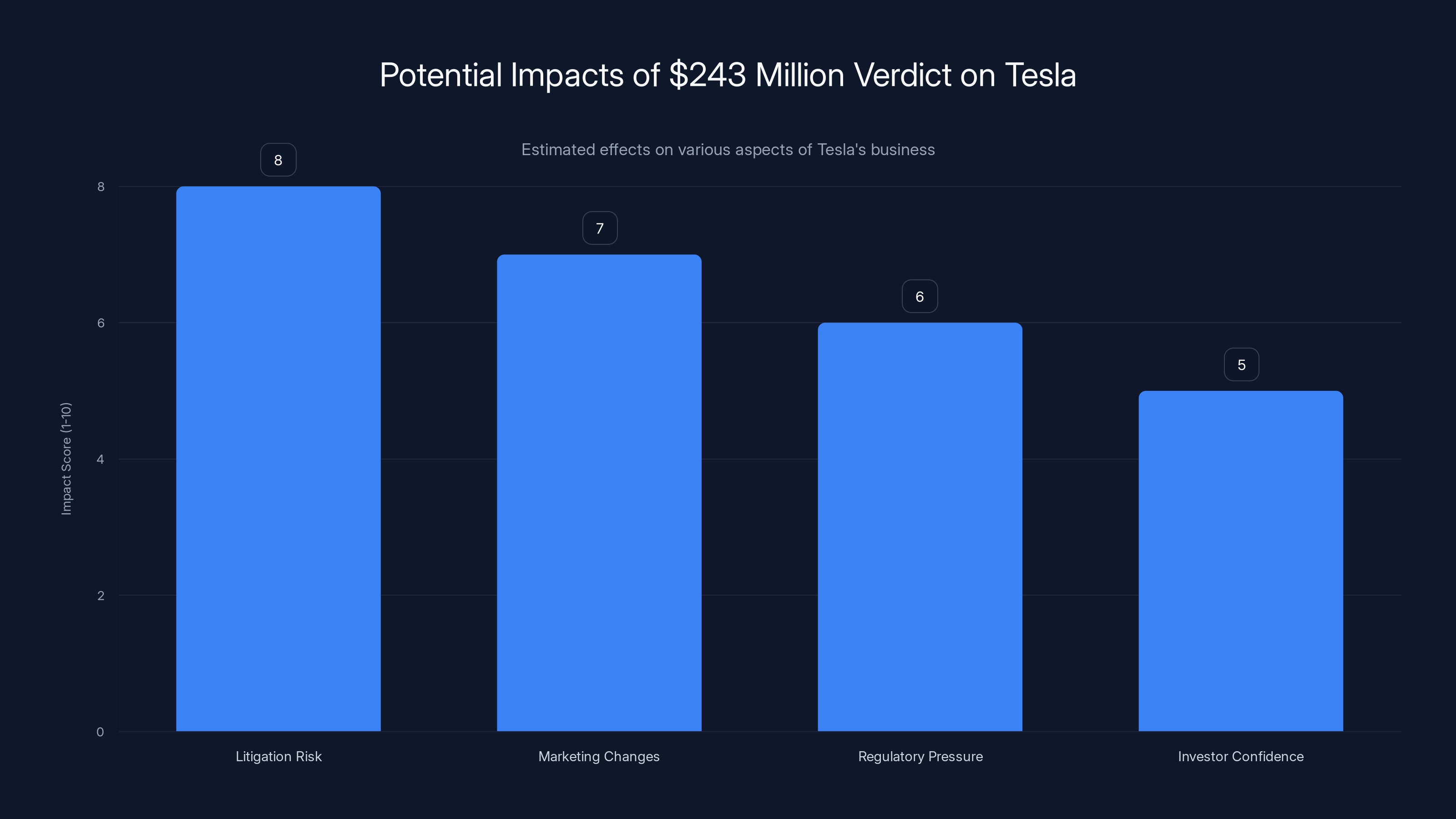

Estimated data suggests litigation risk and marketing changes are the most impacted areas for Tesla following the verdict. Regulatory pressure and investor confidence are also significantly affected.

Autopilot's Actual Capabilities vs. Marketing Claims

To understand why the jury held Tesla partially liable, we need to examine what Autopilot actually does versus what Tesla claims it does.

Autopilot is a driver assistance system, not a self-driving system. That's the official description. The system handles acceleration, braking, and steering under specific conditions. But it requires active driver supervision. The driver must be ready to take control at any moment.

That's the technical reality. But what about the marketing reality?

Tesla has marketed Autopilot with language like "The future of driving," "Autosteer," and claims about it handling highway driving. In promotional videos, Teslas appear to drive themselves with minimal driver input. These presentations suggest a level of autonomy that exceeds the system's actual capabilities.

Specifically, Autopilot has known limitations. It can disengage unexpectedly in certain conditions. It can miss obstacles or lane markings. It performs poorly in fog, heavy rain, or at night. It doesn't reliably detect stationary objects like barriers or stopped vehicles.

The 2019 crash involved a stationary barrier. Autopilot failed to detect it and failed to disengage before impact. This is exactly the scenario the system is known to struggle with.

The jury had access to data comparing Tesla's marketing claims with third-party testing of Autopilot's actual performance. That data showed gaps. The marketing suggested capabilities that the system didn't reliably deliver.

Moreover, Tesla's own documentation warned drivers that Autopilot required constant supervision and could fail unpredictably. But the marketing emphasized the autonomy rather than the supervision requirement.

For consumers like the driver in this case, the disconnect creates a problem. You see marketing suggesting the car can drive itself. You read the fine print saying you have to watch it constantly. Most people believe what the marketing shows, not what the disclaimer says.

The jury essentially found that Tesla had a responsibility to bridge that gap—either through better training, clearer warnings, or better system safeguards. Tesla didn't bridge it. That contributed to the crash.

The Legal Standard: Comparative Negligence and Autonomous Systems

Understanding the verdict requires knowing the legal framework courts use for these cases.

Most states, including Florida, use comparative negligence doctrine. This means multiple parties can contribute to an accident, and liability is assigned proportionally based on each party's contribution.

Compare this to older legal standards where if you were even slightly negligent, you couldn't recover damages. Comparative negligence is more nuanced. It asks: how much did each party contribute?

For autonomous and semi-autonomous vehicle cases, this creates interesting questions. When a crash involves both driver error and system limitations, who bears more responsibility?

Traditionally, the assumption has been: the driver always bears primary responsibility. You chose to use the feature. You had the duty to supervise it. If something went wrong, you should have been paying attention.

But that logic breaks down if the system is designed or marketed in ways that encourage inattention. If the marketing says the car handles highway driving, and the system is sophisticated enough that it can handle some scenarios, drivers rationally come to trust it more than they should.

This verdict suggests courts are starting to account for that dynamic. If a company markets a feature in ways that create unrealistic expectations, and that marketing contributes to dangerous driver behavior, the company bears some responsibility for the resulting crash.

Legal scholars call this the "duty to warn" or "design defect" doctrine. Companies have a duty to design products safely and to warn users of risks. When companies fail at both, liability follows.

In the Tesla case, the court seems to have found both. Autopilot wasn't designed with adequate safeguards for the conditions in which it was used. And Tesla's marketing didn't adequately warn of the risks.

This legal standard is now on the books in Florida. Other states will watch how it develops. And companies building autonomous systems need to pay attention.

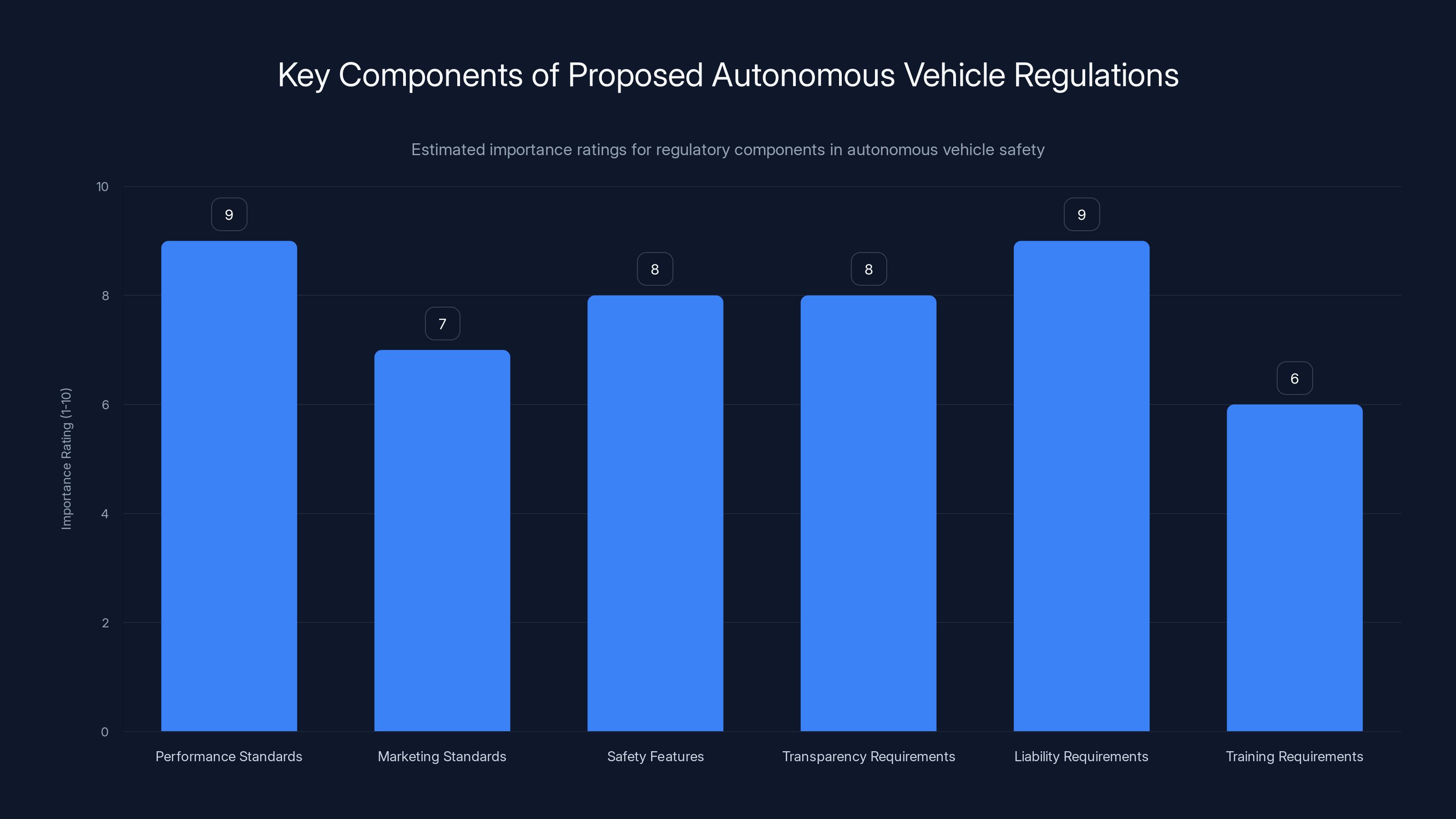

Performance and liability requirements are rated highest in importance for autonomous vehicle regulations, reflecting their critical role in ensuring safety and accountability. Estimated data.

What This Means for Tesla's Business

On the surface, a $243 million verdict seems manageable for a company worth hundreds of billions. Tesla can absorb this hit.

But the long-term implications are more serious. First, this verdict opens the door to future litigation. Plaintiffs' lawyers now have a roadmap. They know they can hold Tesla partially liable for Autopilot crashes by showing that marketing overstates capabilities and safeguards are inadequate.

There are hundreds of Autopilot-related crashes annually. Most don't result in litigation. But some will. And each will cite this precedent.

Second, the verdict pressures Tesla to make actual changes to how it markets and deploys Autopilot. Simply claiming to offer "driver assistance" doesn't protect you if the marketing suggests something more autonomous. The company will need to either improve the system or improve the honesty.

Third, there are regulatory implications. The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration has been investigating Autopilot for years. This verdict provides legal context for whatever standards NHTSA eventually creates. It suggests regulators should be skeptical of company claims about autonomous capabilities and should require better safeguards and warnings, as discussed by Electrek.

Fourth, investor confidence takes a hit. Companies building autonomous systems face new liability exposure. Insurance costs will increase. Development costs will increase. Timeline pressures to bring features to market will face legal constraints.

For Tesla specifically, the verdict suggests the company needs to revise Autopilot. Not necessarily retire the feature, but make it safer and market it more honestly. That costs money. That delays other projects.

Internally, the verdict probably triggers extensive reviews of Autopilot's training, testing, and deployment procedures. Legal departments will re-examine marketing materials. Engineering teams will look for design improvements. Product teams will reconsider feature rollout strategies.

All of this stems from one jury verdict. That's the power of precedent and liability law.

Industry Implications: The Broader Autonomous Driving Landscape

Tesla doesn't operate in a vacuum. Every automaker is developing driver assistance features. Many are pursuing higher levels of autonomy. This verdict affects all of them.

First, it establishes that marketing matters legally. Companies can't make claims about autonomous capabilities that exceed actual system performance and then hide behind liability waivers. If the marketing creates expectations, the company shares responsibility for what happens when those expectations aren't met.

Second, it establishes that design matters. Companies have a duty to implement safeguards that prevent dangerous misuse. A feature that only works in certain conditions needs to recognize when those conditions change and disengage safely.

Third, it establishes that companies can face punitive damages, not just compensatory damages. That's a game-changer. It means one bad crash can cost hundreds of millions, not just the damages to victims. It means juries can punish conduct they find egregious.

Look at what other companies are doing in response. General Motors, Ford, and others are being more cautious in their marketing of autonomous features. They're using terms like "co-pilot" instead of claiming the car drives itself. They're requiring more driver engagement before enabling features. They're implementing geographic limitations and performance thresholds, as noted by Phoebe Wall Howard.

Waymo, which operates fully autonomous vehicles in limited geographies, operates under different rules. The vehicles are supervised remotely. The deployment is controlled. The liability equation is clearer.

Traditional automakers developing Level 2 or Level 3 autonomy—where human supervision is required—are caught in the middle. They want to market compelling features. But they need to avoid liability. This verdict tips the scales toward caution.

Insurance companies are also responding. Coverage for autonomous features is becoming more expensive and more restrictive. That increases the cost of deployment. It slows innovation.

Regulatory bodies internationally are taking note. The European Union, Japan, and China are developing standards for autonomous vehicle marketing and testing. This verdict informs those discussions. It shows that American courts expect companies to deliver on their marketing claims and implement adequate safeguards.

The jury assigned 66.67% liability to the driver and 33.33% to Tesla, indicating shared responsibility for the crash due to both driver misuse and Tesla's marketing of Autopilot.

Regulatory Response and Future Standards

The verdict comes amid growing regulatory scrutiny of Autopilot and similar features.

The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration has been investigating Tesla Autopilot for years. The agency has received hundreds of complaints about unexpected disengagement, phantom braking, and crashes. The investigation has been ongoing without producing definitive conclusions.

This verdict might change that trajectory. It suggests that regulators don't need to wait for definitive causation to act. If a feature creates dangerous expectations and lacks adequate safeguards, that's enough grounds for action.

NHTSA could respond in several ways. It could issue guidance requiring all driver assistance features to include certain safeguards. It could establish standards for marketing autonomous capabilities. It could require independent testing before features are deployed widely.

International regulatory bodies are watching too. The United Nations Economic Commission for Europe develops standards adopted by most countries outside North America. Those bodies are considering rules for autonomous vehicle testing, performance standards, and cybersecurity.

This verdict will inform those discussions. It suggests that voluntary industry standards aren't enough. Government mandates might be necessary.

Likely regulatory responses include:

- Mandatory safeguards: Features must disengage if the driver isn't paying attention

- Performance thresholds: Features can only be marketed if they meet minimum reliability standards

- Clear labeling: Marketing must honestly represent what the feature does

- Driver training: Users must complete training before enabling autonomous features

- Liability insurance requirements: Companies must maintain adequate insurance for autonomous features

These standards would increase the cost of developing and deploying autonomous features. But they'd also reduce liability risk and improve public safety.

Tesla and other automakers are likely lobbying against heavy regulation. They'll argue that innovation requires flexibility. But this verdict makes that argument harder to sustain. Courts have decided that liability is on the table. Regulation might seem like the lesser evil.

The Role of Expert Testimony and Technical Analysis

The verdict didn't happen by accident. It resulted from compelling evidence presented at trial.

The trial likely featured expert testimony on several topics. How does Autopilot actually work? What are its limitations? How does it compare to competing systems? What did Tesla know about its limitations? How did Autopilot perform in the specific conditions of the crash?

Experts for the plaintiff (the crash victims' legal representatives) probably included engineers who had tested Autopilot or similar systems. They likely demonstrated that Autopilot couldn't reliably detect stationary barriers. They probably showed that the system disengaged in specific scenarios and that drivers weren't always warned before disengagement.

They likely compared Tesla's marketing claims to the system's actual capabilities, highlighting gaps. They probably cited other crashes involving similar circumstances.

Experts for Tesla probably argued that the driver bore primary responsibility for misusing the feature. They likely emphasized that Autopilot documentation and warnings clearly stated the feature required active supervision. They probably argued that no reasonable system can prevent all misuse.

They might have argued that the crash was a singular event, not indicative of systemic problems. They probably tried to minimize the significance of marketing claims versus technical documentation.

Juries often find plaintiff experts more credible when the evidence is this compelling. The gap between marketed capabilities and actual performance was probably stark. Comparisons to similar crashes were probably damning. Technical analysis of what safeguards could have prevented this crash was probably persuasive.

Expert testimony is crucial in these cases because most jurors don't understand autonomous systems. They need experts to explain how the technology works, what it can and can't do, and how it compares to industry standards.

As these cases proliferate, we'll see a class of expert witnesses develop—people who specialize in autonomous vehicle safety and liability. Their testimony will shape how juries view these cases. Companies will invest heavily in finding sympathetic experts. Plaintiffs will develop counterarguments.

The battleground of autonomous vehicle liability will increasingly be fought in the testimony of engineers and safety experts, not just in courtroom arguments.

Insurance and Financial Implications

A $243 million verdict has massive financial implications, but not just for the amount itself.

First, consider insurance. Tesla likely carries liability insurance that covers some portion of this judgment. But the amount might exceed policy limits. Or the insurer might dispute coverage, arguing that certain losses aren't covered under the policy.

Vehicle manufacturers typically carry product liability insurance. Coverage often includes damages and sometimes punitive damages. But coverage is typically capped at tens or hundreds of millions—not open-ended.

If the judgment exceeds coverage, Tesla pays the difference from corporate funds. On a $243 million verdict, that's significant.

But the real financial pressure comes from precedent and litigation risk. If Tesla faces hundreds of similar lawsuits—and it likely will—the financial exposure multiplies. Even if each case settles for less than $243 million, the cumulative effect is enormous.

Consider the math. If there are 500 Autopilot-related crashes annually in the US, and 5% result in litigation, that's 25 cases per year. Over five years, that's 125 cases. If each settles for an average of

That changes how companies think about autonomous features. The financial pressure alone might force Tesla to make significant changes.

Insurance costs will also increase. As insurers reassess the risk profile of autonomous features, they'll charge more to cover that risk. Companies will pass those costs to consumers through higher vehicle prices. That reduces demand for autonomous features.

Stock prices can be affected too. Investors care about litigation risk and liability exposure. A verdict like this suggests that Tesla's autonomous vehicle program is riskier than previously thought. That affects how analysts value the company.

Long-term, the financial implications might be the most important aspect of this verdict. It changes the economics of autonomous vehicle development. Features that seemed profitable become loss-making when you account for litigation costs.

Comparing to Other Autonomous Vehicle Litigation

Tesla's Autopilot isn't the only autonomous feature under legal scrutiny. Understanding how this case fits into the broader landscape is important.

Uber's self-driving car program faced significant liability after a pedestrian was struck and killed in 2018. The case highlighted the challenge of deploying autonomous vehicles in complex urban environments. It led to increased scrutiny and eventual scaling back of Uber's autonomous efforts.

Waymo, Google's autonomous vehicle company, operates under stricter controls. Its vehicles are fully autonomous but operate in limited geographies with extensive testing. The company has been more cautious about deployment, which has reduced liability exposure.

General Motors' Super Cruise feature operates under different assumptions. It requires attention monitoring. It's limited to highways. Marketing emphasizes that it's not fully autonomous. That positioning provides some liability protection.

Ford's Blue Cruise follows a similar approach.

The difference between these approaches and Tesla's is telling. Tesla markets Autopilot as more capable than it really is and deploys it more broadly. That creates more liability exposure.

Lidar-based systems used by Waymo generally perform better than camera-only systems like Tesla's Autopilot. That potentially affects liability. If your system reliably detects obstacles, your liability for crashes involving missed obstacles decreases.

Tesla's camera-only approach is less expensive but less reliable. The cost savings are potentially offset by increased liability exposure.

As autonomous systems mature, we'll see litigation establish clear liability standards for different approaches. Camera-only systems will likely face higher liability than lidar-based systems. Fully autonomous systems will face different liability than driver-supervised systems.

This verdict contributes to that emerging framework. It's one data point in how courts evaluate autonomous vehicle liability. Future verdicts will refine the standard.

Public Perception and Trust in Autonomous Vehicles

Beyond the legal and financial implications, this verdict affects public trust in autonomous vehicles.

Autonomous vehicle adoption requires consumer trust. People need to believe the technology is safe. When crashes happen and courts find companies liable, trust erodes.

Media coverage of this verdict reinforces concerns about Autopilot. It emphasizes that the feature contributed to a fatal crash. It highlights the gap between marketing claims and actual capabilities. It raises questions about whether autonomous features are ready for widespread deployment.

Surveys show that public trust in autonomous vehicles is already fragile. A significant portion of Americans say they wouldn't buy a car with autonomous features. This verdict gives those concerns legal validation.

Further, the verdict becomes a narrative. The story is: company markets autonomous feature misleadingly, crashes result, company is held liable, company is punished with punitive damages. That narrative is powerful and shapes how people think about these technologies.

For companies developing autonomous features, rebuilding that trust is challenging. It requires being more cautious in marketing, more transparent about limitations, and more aggressive in implementing safeguards.

Tesla's brand has historically benefited from innovation hype. The company is seen as pushing boundaries. But that narrative has downsides. It can lead to overstatement of capabilities. This verdict is a reckoning for that approach.

Moving forward, autonomous vehicle companies will need to balance innovation with responsibility. That means marketing that's accurate, systems that are reliable, and transparency about limitations.

The public will be watching. One verdict isn't enough to change perception permanently, but it's a start. Multiple similar verdicts will reinforce the message that companies can be held liable for autonomous vehicle crashes.

Future Legal Battles: What's Coming Next

This verdict is unlikely to be the last major autonomous vehicle lawsuit.

Tesla faces multiple other investigations and potential lawsuits related to Autopilot. Regulators are examining the feature. Plaintiff attorneys are researching potential cases. If this verdict stands through appeals, it will encourage more litigation.

We're likely to see:

- More Autopilot cases: Similar crashes will be litigated using this verdict as precedent

- Cases against other automakers: Once the legal standard is established, plaintiffs will pursue similar cases against General Motors, Ford, and others

- Regulatory investigations: NHTSA and international bodies will use this verdict to justify stricter regulations

- Class action suits: Groups of Autopilot owners might sue Tesla for misrepresentation regarding the feature's capabilities

- Product recalls: Regulators might mandate changes to how Autopilot is deployed or marketed

Appeals are always possible. Tesla could appeal to a higher court. But as discussed, the legal hurdles are high. The verdict would need to be clearly erroneous or based on misinterpretation of law. Judge Bloom's reasoning seems sound legally.

If appeals fail, this verdict becomes settled law in Florida. It might influence how other states handle similar cases, though each state interprets law differently.

For Tesla, the strategic question is whether to fight these cases or settle them. Fighting establishes that the company will defend its position. Settlement suggests the company wants to move past liability. Each approach has downsides and benefits.

Settlement is often cheaper than litigation, even at the verdict amount. It also allows Tesla to control the narrative. But it sets expectations for future settlements. Claimants will demand similar amounts.

Fighting is more expensive in the short term but potentially cheaper long-term if Tesla wins. But each loss reinforces the liability narrative.

Likely, Tesla will pursue a mixed strategy: settle cases with strong evidence against it, fight cases where liability is less clear, and lobby for regulatory standards that provide liability protection.

Regulatory Frameworks: Building Better Standards

Beyond litigation, regulators need to respond to autonomous vehicle safety concerns.

The current approach is relatively hands-off. Automakers self-regulate. NHTSA conducts periodic reviews. Safety standards exist, but they haven't been updated significantly for autonomous systems.

This verdict suggests that approach is insufficient. If companies can develop and deploy autonomous features without clear regulatory oversight, liability litigation is likely. Better proactive regulation might prevent both crashes and lawsuits.

What should regulations include?

Performance standards: Features must meet minimum reliability thresholds before deployment. Testing should be standardized and verified by independent parties.

Marketing standards: Claims about autonomous capabilities must be accurate and supported by testing. Disclaimers must be clear and prominent.

Safety features: Mandatory safeguards like driver attention monitoring, quick disengagement, and geofencing based on system capabilities.

Transparency requirements: Companies must disclose performance data, limitations, and incidents to regulators.

Liability requirements: Companies must maintain adequate insurance and financial reserves for potential liability.

Training requirements: Users must be trained on feature capabilities and limitations before enabling autonomous features.

Implementing these standards would increase development costs. But it would also reduce liability exposure and improve public safety.

Regulators globally are moving in this direction. The EU is considering mandatory standards. Japan is developing testing protocols. China is establishing performance requirements.

The US is slower to respond. But this verdict might accelerate that process. It shows that without regulatory standards, courts will fill the vacuum. That creates uncertainty and unpredictability.

Companies often prefer regulations to litigation. Clear standards allow them to know what's expected. Litigation creates uncertainty and escalating costs.

Expect to see increased regulatory activity around autonomous vehicles in the next few years. NHTSA will likely issue new guidance or standards. Congress might pass legislation. States might adopt their own rules.

Tesla and other automakers will try to shape these standards through lobbying and engagement with regulators. Environmental and safety advocates will push for stricter standards. The result will likely be more prescriptive rules than exist today.

The Engineering Perspective: What Autopilot Needs

From an engineering standpoint, what changes would make Autopilot safer?

First, driver attention monitoring is essential. The system should track whether the driver is paying attention. If not, it should disengage gradually, warning the driver first.

Current Autopilot has limited attention monitoring. It's one reason it's limited to certain road types and conditions. Better attention monitoring would expand the scenarios where the feature could operate safely.

Second, better obstacle detection is crucial. Autopilot relies primarily on cameras. That's less reliable than lidar-based systems for detecting stationary obstacles.

Upgrading the sensor suite would improve reliability. This might mean adding lidar, radar, or other sensors. It would increase cost but improve safety and reduce liability.

Third, geographic and scenario limitations are important. The system should recognize when it's operating outside its design envelope and disengage.

A divided highway with concrete barriers is a scenario where Autopilot is known to struggle. The system could be programmed to disable itself on such roads. That would prevent misuse without relying entirely on driver judgment.

Fourth, predictive maintenance is valuable. The system should alert drivers before potential failures. If a sensor is degrading or weather conditions are poor, the system should warn the driver that Autopilot might not function reliably.

Fifth, over-the-air updates allow Tesla to fix issues and improve performance without recalls. This is actually one of Tesla's advantages. The company can push improvements to the entire fleet quickly.

Tesla should use this capability more aggressively to address safety concerns. As issues are discovered, fixes should be deployed rapidly.

Sixth, data transparency is important. Tesla collects vast amounts of driving data. That data could be analyzed to identify failure modes and fix them proactively.

Currently, Tesla shares minimal data with researchers and regulators. More transparency would improve public trust and help identify issues before they cause crashes.

Implementing these changes would make Autopilot significantly safer. Some, like attention monitoring and geofencing, are relatively straightforward software improvements. Others, like upgraded sensors, require hardware changes.

The cost of these improvements would be modest relative to the liability exposure. A few hundred dollars per vehicle for better sensors and software is worth it if it prevents $243 million verdicts.

Conclusion: A Turning Point for Autonomous Vehicle Liability

The judge's refusal to overturn Tesla's $243 million Autopilot verdict marks a significant moment in autonomous vehicle law and regulation.

For years, the assumption was that autonomous features were experimental tools users employed at their own risk. Companies emphasized driver responsibility. If you misused the feature, it was your fault.

This verdict challenges that assumption. It says that companies bear responsibility for how they design and market autonomous features. If the marketing encourages dangerous use, if the system lacks adequate safeguards, if the company knows about limitations but doesn't adequately warn users, liability follows.

That's a seismic shift. It means autonomous vehicle development is no longer just an engineering challenge. It's also a legal and regulatory challenge.

Tesla will continue developing Autopilot. The verdict won't kill the feature. But it will change how Tesla approaches development and deployment. More cautious marketing. More aggressive safety improvements. More coordination with regulators.

Other automakers are watching closely. The verdict sets a precedent for how courts will evaluate similar features. That changes the cost-benefit analysis of autonomous features. It makes some features uneconomical. It accelerates development of features with better safety profiles.

Regulators are also paying attention. The verdict shows that without government standards, courts will establish liability rules through litigation. Some regulators might prefer to establish rules proactively, before major accidents and verdicts accumulate.

Investors in autonomous vehicle companies should update their risk models. The liability exposure is higher than previously thought. Development timelines might extend as companies implement additional safety features. Returns on autonomous vehicle investments might be lower due to regulatory costs.

Public trust in autonomous vehicles will face headwinds from this verdict. The narrative of a company overselling capabilities and facing legal consequences is powerful. Rebuilding trust requires demonstrating that companies take safety seriously and that autonomous features actually work as promised.

Ultimately, this verdict isn't really about one crash or one company. It's about the emerging legal and regulatory framework for autonomous vehicles. How will society balance innovation with safety? When should autonomous features be permitted? How much responsibility do companies bear for crashes involving their systems?

This verdict provides answers to some of those questions. And those answers will shape the future of autonomous driving for years to come. Companies, regulators, and the public are all learning to think differently about these technologies. That's uncomfortable but necessary.

Autonomous vehicles represent tremendous potential. They could reduce crashes, improve mobility, and create new capabilities. But they also create new risks and new questions about responsibility and liability.

This verdict reflects society asking hard questions about those tradeoffs. The outcome might slow autonomous vehicle deployment. It might increase costs. But it will ultimately result in safer, more trustworthy systems.

That's worth the cost.

FAQ

What was the original Tesla Autopilot crash that led to this verdict?

In May 2019, a Tesla Model 3 driving on Autopilot crashed into a concrete barrier on a divided highway in Delray Beach, Florida. The driver, Naibel Benavides, was killed, and passenger Dillon Angulo was critically injured. The crash investigation revealed that Autopilot failed to detect the stationary barrier and failed to disengage before impact, leading to questions about the system's design and Tesla's marketing of its capabilities.

Why did the judge deny Tesla's appeal of the verdict?

Judge Beth Bloom found that Tesla's arguments for overturning the verdict were essentially the same arguments the company had already presented during trial and in previous summary judgment motions. The judge stated that Tesla presented no new evidence or controlling law that would justify changing the jury's verdict, making the appeal legally insufficient to overturn the jury's decision.

How was liability split between the driver and Tesla in this case?

The jury assigned two-thirds liability to the driver and one-third to Tesla. This comparative negligence split recognized that while the driver bore primary responsibility for misusing Autopilot, Tesla shared liability for inadequate safeguards and marketing that may have created unrealistic expectations about the feature's capabilities and reliability.

What are punitive damages and why did Tesla face them?

Punitive damages are awarded to punish defendant conduct and deter future misconduct, beyond compensating the victims. The jury assessed punitive damages against Tesla alone, suggesting they found Tesla's actions demonstrated recklessness or intentional misconduct regarding how Autopilot was marketed and how safely the feature was deployed, going beyond simple negligence.

What does this verdict mean for other Autopilot crashes?

This verdict establishes legal precedent that companies can be held partially liable for autonomous vehicle crashes if their marketing overstates capabilities or if their systems lack adequate safeguards. Future Autopilot crash litigation will likely reference this verdict, potentially making it easier for plaintiffs to establish Tesla's liability in similar cases.

How will this verdict affect Tesla's Autopilot marketing and development?

The verdict will likely force Tesla to revise how it markets Autopilot, using more conservative language and clearer warnings about the system's limitations. The company may also need to invest in additional safety features like better driver attention monitoring, improved obstacle detection, and geographic limitations to prevent misuse in scenarios where Autopilot is known to fail.

What regulatory changes might result from this verdict?

The verdict could accelerate NHTSA and international regulatory action on autonomous vehicle standards. Regulators may implement mandatory safety features, marketing standards requiring accurate capability claims, mandatory driver training, performance testing requirements, and liability insurance minimums for companies deploying autonomous features.

How does this verdict compare to other autonomous vehicle litigation?

Like Uber's 2018 autonomous vehicle pedestrian fatality case, this verdict shows courts will hold companies liable for autonomous vehicle incidents. However, unlike some competitors that use lidar-based systems with better obstacle detection or fully autonomous vehicles in controlled environments, Tesla's camera-only Autopilot deployed broadly across many road types faces higher liability exposure.

Could Tesla successfully appeal this verdict to a higher court?

Higher-level appeals face very high hurdles. Tesla would need to show legal error by the judge or that no reasonable jury could reach this verdict. Judge Bloom's reasoning appears legally sound, and the evidence supporting Tesla's partial liability seems substantial, making successful appeal unlikely though not impossible.

What should consumers know about using Autopilot after this verdict?

Consumers should understand that Autopilot, despite its marketing, is not a fully autonomous system and requires active driver supervision at all times. The verdict reinforces that the system has significant limitations, particularly with stationary obstacles, and that disengagement can happen unexpectedly. Users should never rely on Autopilot to fully control the vehicle in any situation.

Key Takeaways

- Judge denied Tesla's appeal with clear reasoning: company recycled failed arguments with no new evidence or legal theory

- Jury verdict split liability 2/3 driver, 1/3 Tesla, signaling companies share responsibility for dangerous autonomous features

- Punitive damages assessed only against Tesla suggest legal system views company conduct as reckless, not merely negligent

- Verdict establishes that marketing claims about autonomous capabilities create legal liability if they exceed actual system performance

- Industry-wide implications: other automakers will revise autonomous feature marketing and increase safety investment to reduce litigation risk

Related Articles

- Tesla Dodges 30-Day License Suspension in California [2025]

- Autonomous Vehicle Safety: What the Zoox Collision Reveals [2025]

- Tesla's Cybercab Launch vs. Robotaxi Crash Rate Reality [2025]

- Waymo's Remote Drivers Controversy: What Really Happens Behind the Wheel [2025]

- Senate Hearing on Robotaxi Safety, Liability, and China Competition [2025]

- Waymo Robotaxi Strikes Child Near School: What We Know [2025]

![Tesla's $243M Autopilot Verdict Stands: What the Ruling Means [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/tesla-s-243m-autopilot-verdict-stands-what-the-ruling-means-/image-1-1771611149682.jpg)