The Geothermal Blind Spot Nobody's Talking About

You probably don't think about geothermal power very often. If you do, you're imagining Iceland. Or maybe that one time you visited Yellowstone and saw steam vents shooting out of the ground. But here's what keeps energy engineers up at night: we're sitting on enough untapped geothermal resources to power roughly 10% of the United States, and we're completely missing it.

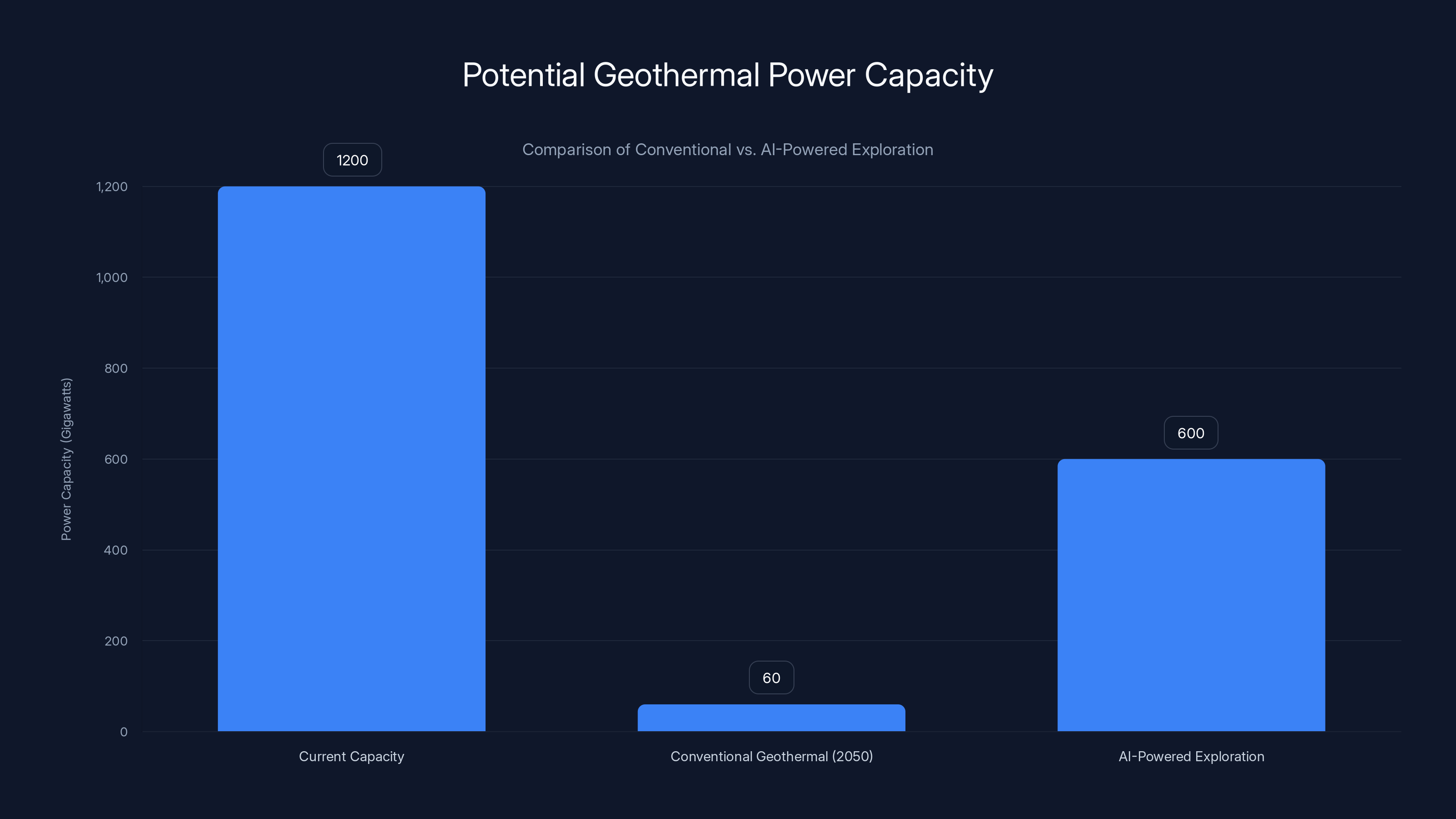

The numbers are staggering. The Department of Energy estimates geothermal could generate 60 gigawatts by 2050. That's substantial. But experts working in the space think that number drastically underestimates what's actually available. Some researchers believe the real potential is closer to a terawatt—that's 1,000 gigawatts. For context, the entire United States generates about 1,200 gigawatts total. We're talking about a resource that could potentially supply power at a scale most people can't conceptualize.

The frustrating part? We're not talking about science fiction technology. We're not waiting for some breakthrough that might happen in 20 years. The tools exist today. The knowledge exists. The only thing missing is the will to look in the right places.

Conventional geothermal—the kind that taps into naturally fractured hotspots—has been essentially stagnant for over a decade. It produces about 4 gigawatts in the United States. Compare that to other renewable sources. Wind generates roughly 150 gigawatts. Solar is approaching 100 gigawatts. Geothermal barely moves the needle. That's not because geothermal is inherently limited. It's because we've been looking for it in all the wrong places.

The real breakthrough isn't coming from fancy drilling techniques or exotic engineering. It's coming from artificial intelligence applied to exploration. Companies like Zanskar are using machine learning to find geothermal resources that exist but have been invisible to traditional exploration methods. They're resurrecting power plants that were abandoned as unprofitable. They're discovering entirely new sites. And they're doing it at a pace that suggests the next decade could transform how we think about geothermal energy entirely.

Why Conventional Geothermal Has Been Overlooked for 20 Years

The story of geothermal exploration is a story of flawed assumptions. For decades, energy companies looked for geothermal resources the same way you'd look for buried treasure. Find the obvious landmarks. Dig there. It worked, sometimes. But it left 95% of the actual resources invisible.

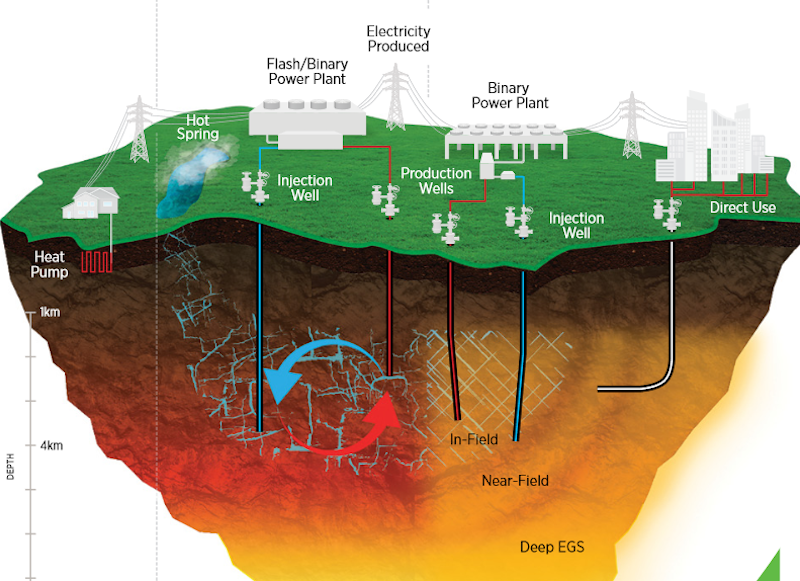

Traditional exploration relied on surface clues. Hot springs? That's a sign. Geysers? Definitely drill there. Volcanoes? Promising area. The problem is that these visible indicators are the exception, not the rule. The vast majority of hot rock formations deep underground show absolutely no surface expression. They're silent. They're hidden. They're easy to miss if you're not looking specifically for them.

This approach worked well enough in the 1970s and 1980s when geothermal was first being developed seriously in the U. S. But it hit a wall. After you've found all the obvious sites, what then? The natural answer would be to develop better exploration methods. Instead, the industry basically gave up. Geothermal capacity in the United States has grown less than a gigawatt in the last decade.

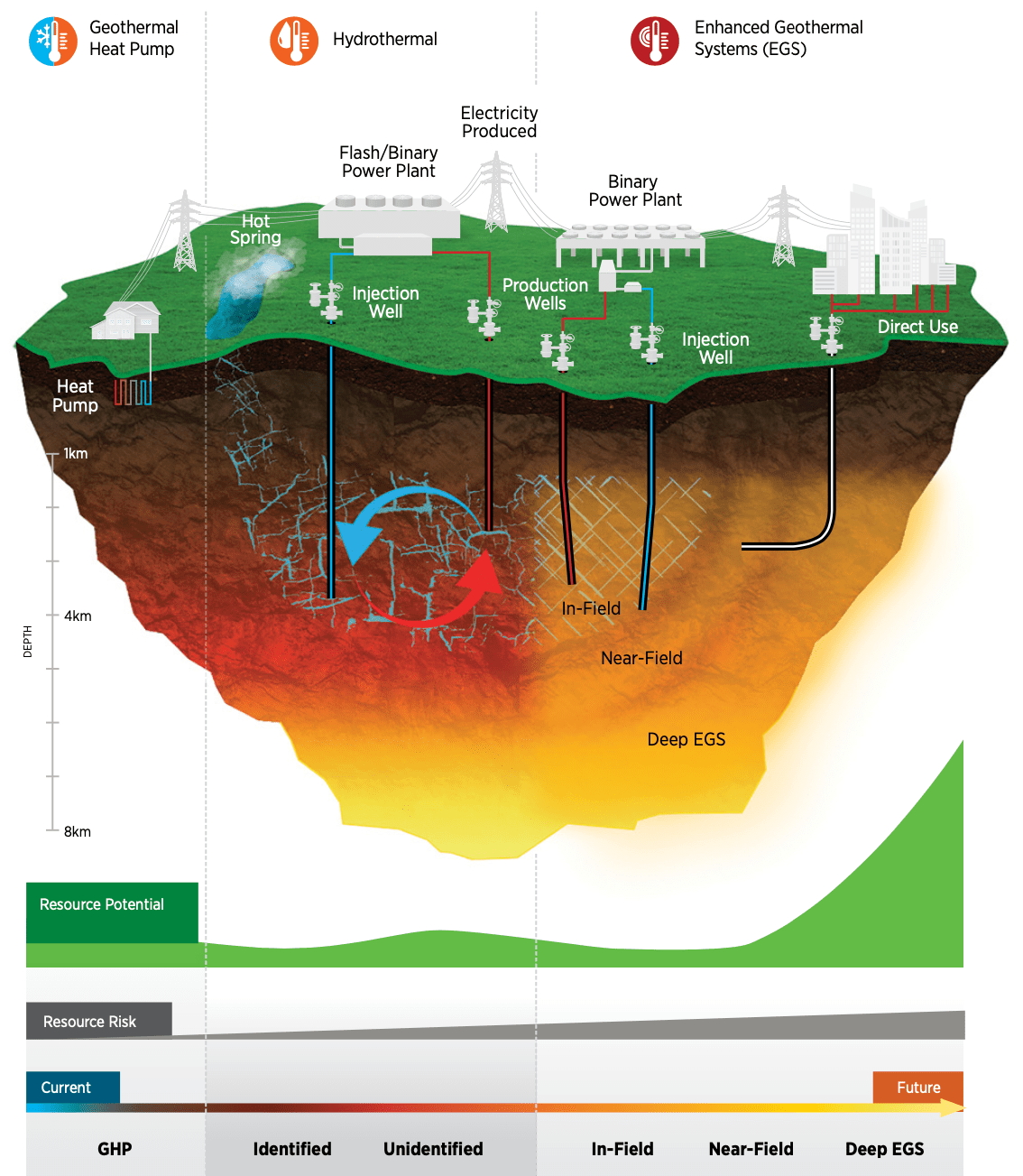

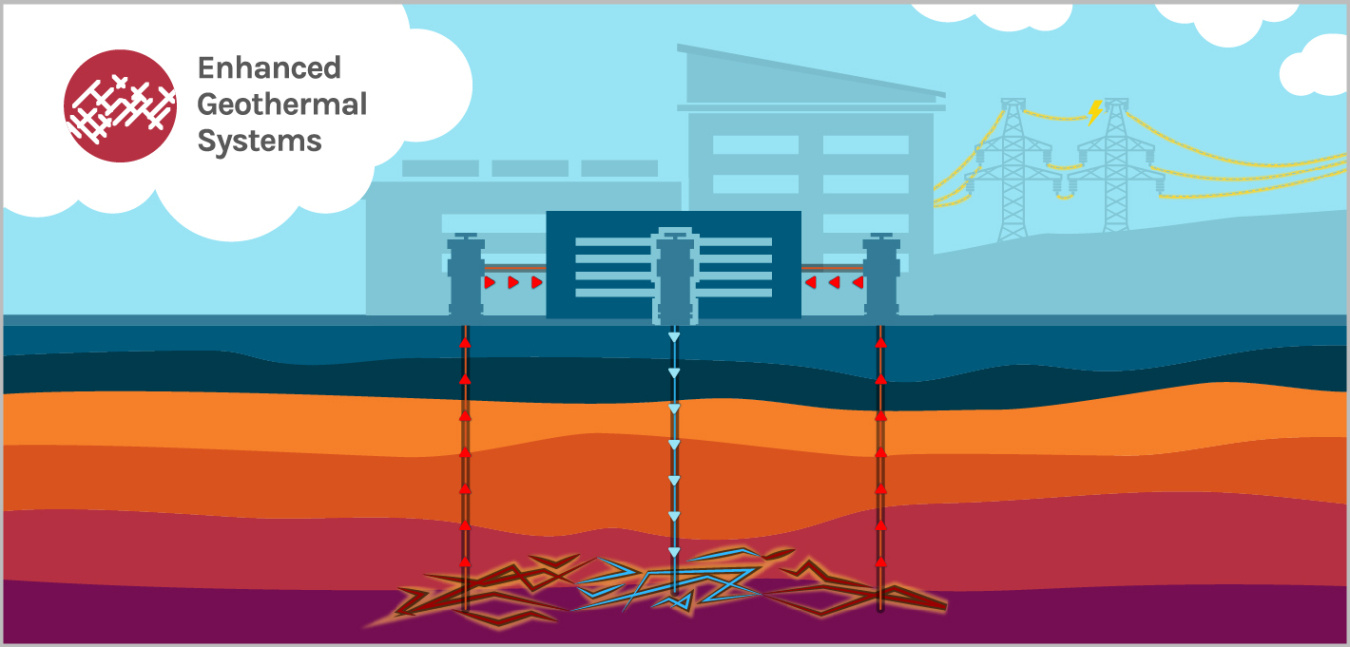

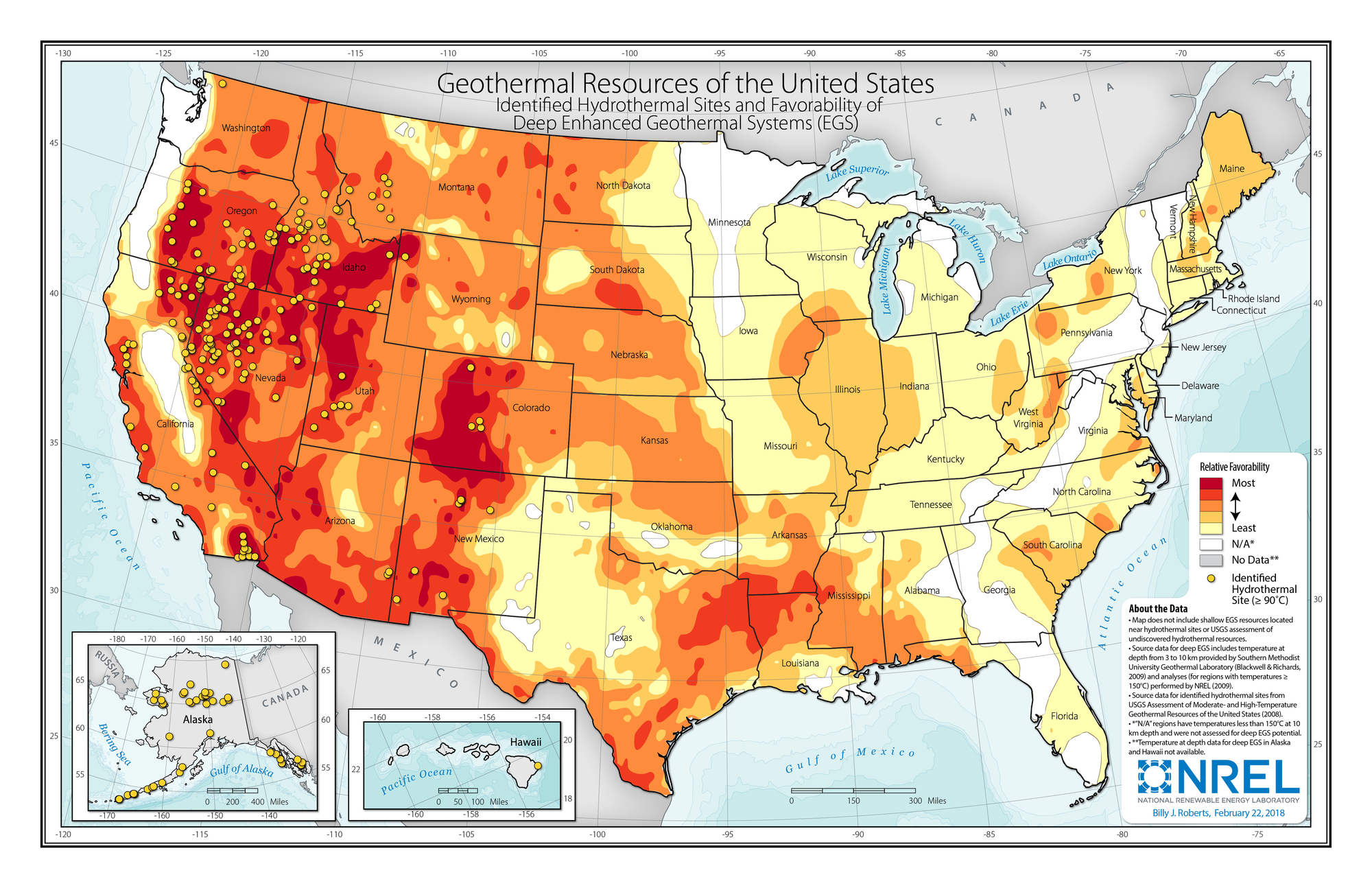

The conventional wisdom became: geothermal is geographically limited. It only works in places like California, Nevada, Utah. End of story. This assumption became so entrenched that it shaped policy, investment decisions, and research priorities. Enhanced geothermal systems—which use hydraulic fracturing to create artificial reservoirs—became the industry darling because they promised to overcome these geographic limitations. Companies poured resources into EGS. Universities built research programs around it. Venture capital followed.

All of this was reasonable. EGS does have enormous potential. But in focusing on the next breakthrough, the industry completely abandoned the proven technology that was already working in front of their faces. It's like spending billions developing better railroads while ignoring the highways that already exist.

The geographic reality also played a role. Yes, the U. S. West has the highest concentration of geothermal potential. But that doesn't mean it's limited to obvious locations. The Basin and Range Province, which stretches across Nevada, Utah, California, and Oregon, is riddled with geothermal resources. Most have never been properly surveyed. Some were discovered accidentally when oil and gas companies drilling for other resources hit hot rocks instead.

Think about that for a second. We're finding geothermal energy by accident. Not through systematic exploration, but through random drilling campaigns aimed at finding something else entirely. That's an indictment of how unsophisticated our geothermal exploration methods have been.

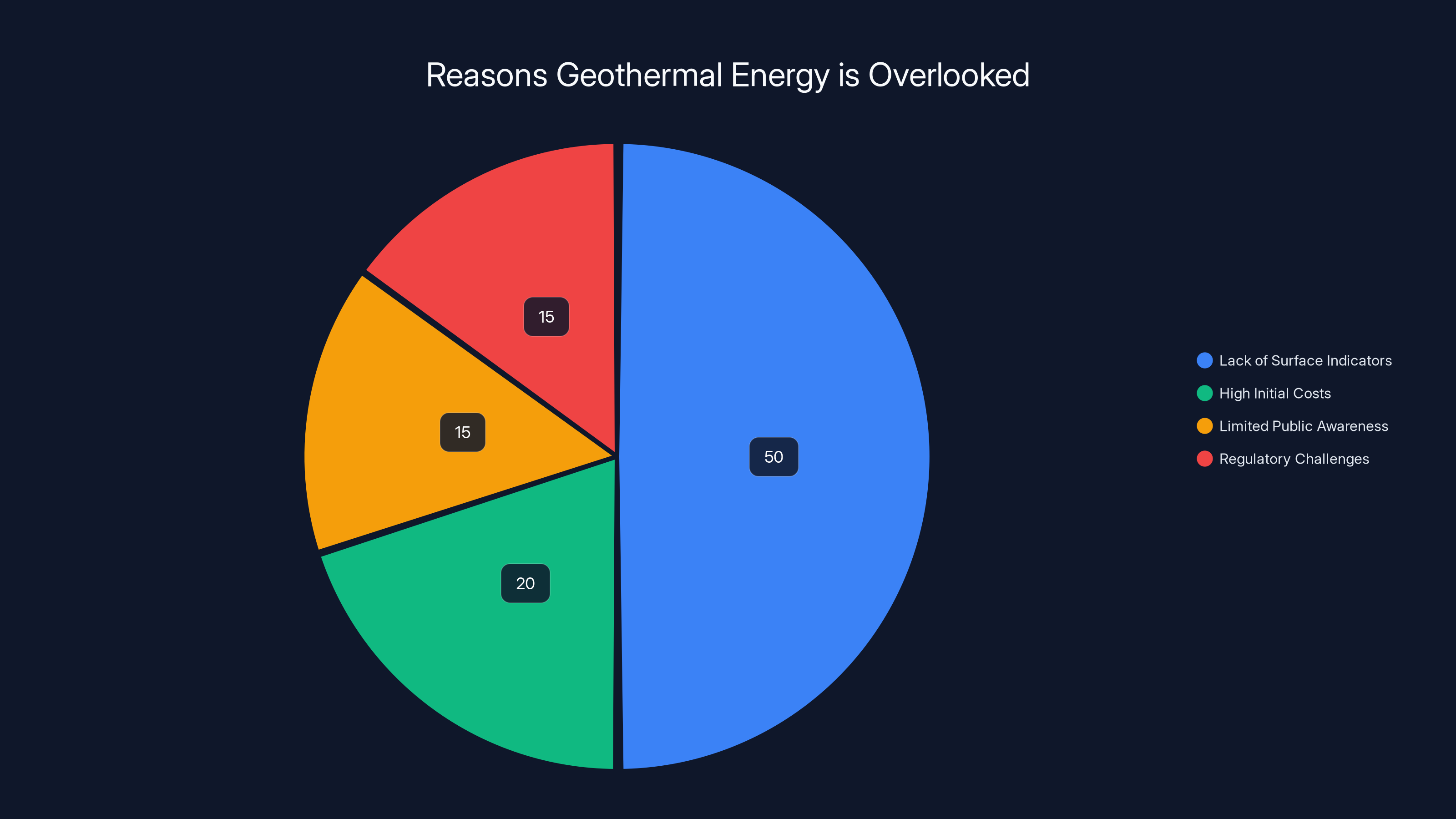

Lack of visible surface indicators is the primary reason geothermal energy has been overlooked, accounting for an estimated 50% of the issue. Estimated data.

The AI Revolution: Making the Invisible Visible

Here's where it gets interesting. Machine learning doesn't care about conventional wisdom. It doesn't have preconceptions about where geothermal resources should exist. It can look at massive datasets—geological surveys, temperature measurements, rock composition, seismic data, drilling records from oil and gas operations—and find patterns that human geologists would miss.

The approach starts with supervised machine learning. You feed the algorithm data from known geothermal sites. You include features about what those sites have in common: specific rock types, certain seismic signatures, particular gravitational anomalies, magnetic field characteristics. Then you feed it data from regions where no geothermal resources have been discovered, and the algorithm flags areas that share similar characteristics.

It's statistical pattern matching on steroids. The algorithm is essentially saying: "Based on everything I know about places we found geothermal before, these other areas look similar. You should probably check them out."

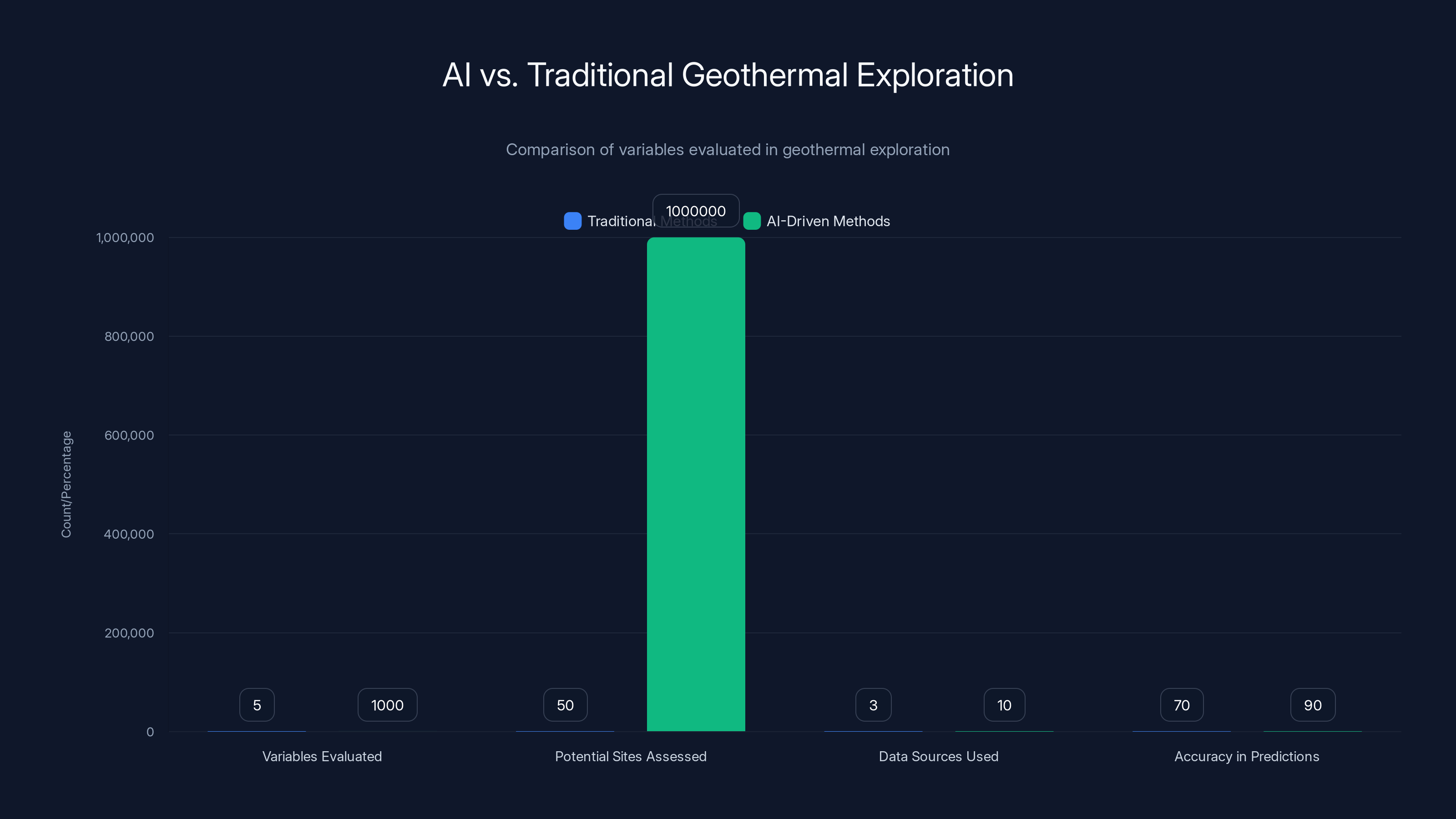

But here's what makes this genuinely different from previous exploration efforts: the algorithm can weigh thousands of variables simultaneously. A geologist looking at maps might identify a few promising areas. An AI system can evaluate millions of potential sites, scoring each one based on hundreds of geological and geophysical characteristics.

Companies like Zanskar take this one step further. After identifying promising sites, they apply a technique called Bayesian evidential learning to reduce uncertainty. This is where it gets technical, but the concept is straightforward: you build a set of initial assumptions about what a resource might look like. Then you use data to test those assumptions, calculating probabilities for different scenarios.

The real magic happens when data is missing. In geothermal exploration, you often don't have complete information. You might have temperature data but no pressure data. You might know the rock type but not the fracture density. Zanskar built a geothermal simulator to fill in these gaps. Rather than making guesses, they simulate thousands of possible scenarios and use the actual data they have to narrow down the most likely ones.

The practical result? They've gone from a success rate of "sometimes we get lucky" to "we found something valuable at 3 out of 3 sites we examined." That's a 100% success rate on recent exploration. The company's leadership has stated that they have enough potential sites in their pipeline to support at least a gigawatt of generating capacity. At current growth rates, that's roughly 25 times the geothermal capacity that came online in the entire last decade.

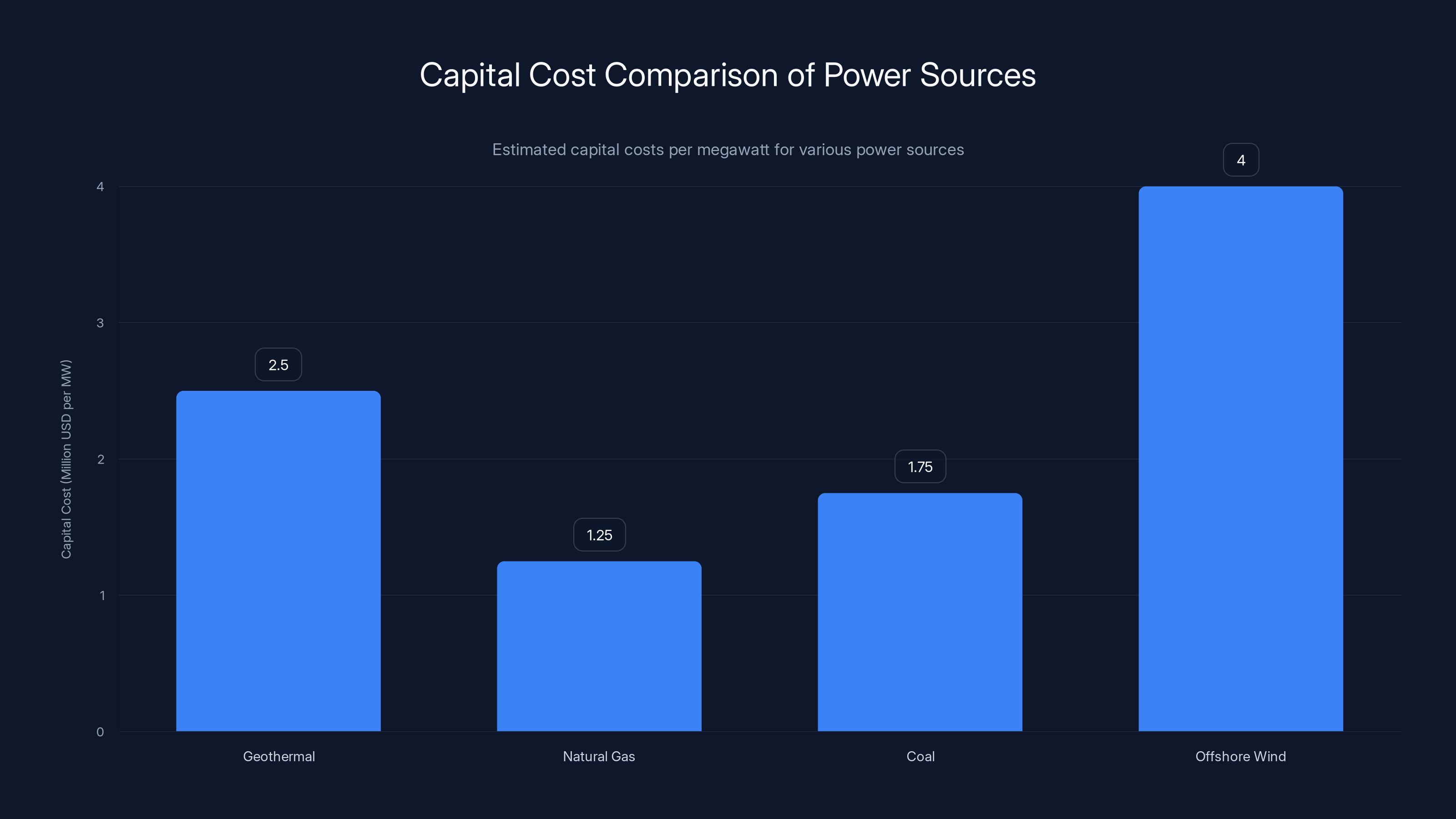

Geothermal power has a higher capital cost than natural gas but is competitive with coal and cheaper than offshore wind. Estimated data.

Case Study: Resurrection of an Abandoned Power Plant

One of Zanskar's early successes illustrates exactly how this approach works in practice. They identified an area in New Mexico where geothermal power had been developed decades earlier. The original operators had extracted what they thought was possible and then abandoned the site when production declined. The power plant sat dormant.

Using their AI-powered exploration, Zanskar found evidence of additional geothermal resources at the same location. Not tiny amounts, either. They discovered over 100 megawatts of potential capacity that hadn't been previously identified. This wasn't a new discovery from scratch. It was recognizing missed opportunity right next to an existing infrastructure that was already built and waiting.

This is crucial because it illustrates one of the largest economic advantages of their approach. Building new energy infrastructure is expensive. Land permits, grid connections, regulatory approval—it all takes years and costs billions. At this New Mexico site, much of that infrastructure already existed. The power plant was there. The transmission lines were there. The permitting history existed. Zanskar could potentially bring this dormant capacity back online dramatically faster and cheaper than developing a greenfield site.

Moreover, the economics of operating a power plant improve when you can squeeze more production from existing infrastructure. Geothermal plants have exceptionally low operating costs—once you've drilled the wells and built the plant, you can generate electricity continuously, 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, for decades. The capital cost gets amortized over a much longer asset life if you're producing more power from the same infrastructure.

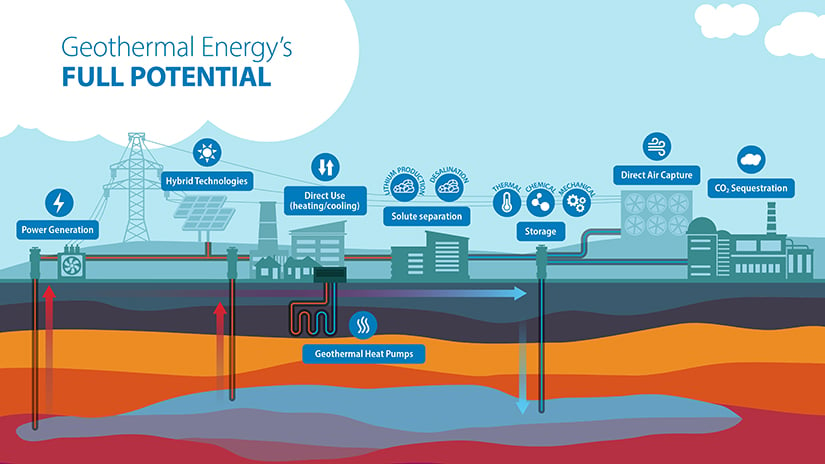

The New Mexico case also demonstrates something important about geothermal's practical advantage: it can integrate into existing grids without the intermittency issues that plague solar and wind. This isn't a theoretical advantage. Grid operators deal with real constraints. Solar and wind require energy storage or backup capacity because the sun doesn't always shine and the wind doesn't always blow. Geothermal runs constantly. From a grid operator's perspective, it's fundamentally more valuable than intermittent sources, assuming the economics work out.

The Discovery of New Sites: Beyond Traditional Boundaries

The New Mexico story is impressive, but the real proof of concept comes from Zanskar discovering entirely new geothermal sites that traditional exploration methods would have missed.

They've identified two new locations with over 100 megawatts of combined potential. These weren't located in the obvious hotspots that everyone knew about. They were found in regions where previous conventional wisdom suggested geothermal resources were limited or nonexistent. This is significant because it suggests that the true geographic scope of viable geothermal development is much larger than the industry currently believes.

The implications are enormous. If new sites keep appearing in unexpected locations, it means the geothermal resource base is distributed across the western U. S. far more broadly than previously understood. That changes the economic calculations. It means geothermal capacity could be added in more locations, supporting grid stability in different regions.

What's particularly interesting is that these discoveries happened relatively quickly, with a relatively small team using modern tools. Zanskar hasn't been working on this for decades. They've been applying modern AI and computational methods to geothermal exploration for a few years. And they're already outpacing the discovery rate of the conventional industry by orders of magnitude.

If this trend continues—if AI-powered exploration accelerates the discovery of new sites—then the financial case for geothermal development improves dramatically. Venture capital has poured roughly $2 billion into geothermal companies over the past five years. Most of that went toward enhanced geothermal systems technology development. But if conventional geothermal exploration suddenly becomes much more effective, those projects become far more economically attractive to investors.

This is where the venture capital money becomes relevant. Zanskar's Series C fundraising round brought in $115 million. That's substantial funding for an exploration-stage company, but it's not massive in the context of energy infrastructure development. However, this funding isn't just for exploration. It's backing the pipeline of projects they've identified.

AI-driven geothermal exploration evaluates significantly more variables and potential sites than traditional methods, leading to higher prediction accuracy. Estimated data.

Understanding the Terawatt Potential: The Math Behind the Claim

When Zanskar's founders talk about a terawatt-scale opportunity, they're making specific mathematical claims about what's actually out there. Let's break down where that number comes from.

First, understand that a terawatt is an enormous amount of power. The entire United States generates about 1,200 gigawatts on average. A terawatt equals 1,000 gigawatts. So Zanskar is saying that geothermal could theoretically represent nearly the entire current electrical generation capacity of the country. That sounds impossible until you do the math.

The calculation works like this. The Earth generates heat through radioactive decay deep in the crust. That heat flows toward the surface constantly. In most places, it flows so slowly that it's not useful for power generation. But in certain areas, you have hot rock at accessible depths with water to move the heat and extract it.

The Department of Energy calculated that conventional geothermal could provide 60 gigawatts by 2050. That's based on assumptions about discovery rates and development timelines using historical methods. But Zanskar's founders argue that this calculation dramatically underestimates the available resource because it assumes the current discovery rate would continue.

If, instead, modern AI-powered exploration discovers an order of magnitude more sites than previously estimated—going from thousands of potential locations to tens of thousands—then the resource base expands proportionally. And if you can extract more power from each site using modern drilling techniques than older technology allowed, you multiply that again.

Let's use a simplified calculation. Suppose conventional geological surveys have found and documented perhaps 100 significant geothermal locations across the western U. S. If AI-powered exploration can identify 10 times that many previously unknown sites—which isn't unreasonable given that 95% of geothermal systems show no surface expression—you're suddenly looking at 1,000 viable locations. If each of those averages 1 megawatt of capacity (a conservative estimate for developed geothermal resources), you're at 1,000 megawatts or 1 gigawatt.

Now multiply again: if modern drilling techniques can extract more power from each site, perhaps 2-5 times more than historical average, you're looking at 2-5 gigawatts from these newly discovered sites. Scale that across the western U. S., and you start approaching the terawatt range—especially if you eventually expand beyond the West.

This isn't magic math. It's recognizing that we've been massively undercounting the resource because our exploration methods were inadequate. Better exploration methods reveal more resources. Better extraction methods produce more power from each resource. The combination compounds.

The Technology Stack: AI, Simulation, and Field Validation

Understanding Zanskar's approach requires understanding the complete technology stack they've built. It's not just machine learning; it's machine learning integrated with domain expertise, physical simulation, and rigorous field validation.

The first layer is data aggregation. They're pulling together datasets from multiple sources: historical drilling records, seismic surveys, temperature logs, gravity measurements, magnetic surveys, rock composition data, and more. Some of this data is public—published in geological surveys and academic papers. Some comes from partnerships with companies that have conducted exploration. The diversity of data sources matters because each dataset reveals different aspects of subsurface conditions.

The second layer is the machine learning models themselves. Zanskar trains supervised learning models on known geothermal sites. The algorithm learns: "When we see this combination of seismic signature, gravity anomaly, temperature pattern, and rock type, there's usually geothermal potential." It's learning patterns from success cases.

But here's where they diverge from standard data science. They don't just feed all this into a neural network and trust whatever predictions come out. Geothermal exploration has physical constraints. You can't just drill anywhere based on ML predictions. You need to understand the underlying geology.

So the third layer is the Bayesian evidential learning system. This is where domain expertise gets baked in. Rather than treating predictions as binary (yes/no, drill here/don't drill here), BEL calculates probability distributions. It quantifies uncertainty. It identifies which types of additional data would most reduce that uncertainty.

The fourth layer is the geothermal simulator. When gaps exist in the available data, rather than guessing or making simplified assumptions, Zanskar simulates thousands of plausible scenarios. Each scenario models how heat would flow through different rock types, with different water circulation patterns, at various depths and temperatures. The simulation constrains these scenarios using whatever actual data they have. The result is a probability distribution of what's actually happening underground at a given site.

Only after all this analysis do they make the recommendation to send a team for field validation. And field validation means actually drilling test wells—not deep production wells, just shallow wells that can confirm or refute the predictions. This is crucial because it creates a feedback loop. Every successful prediction and every unsuccessful prediction gets fed back into the machine learning models, making them continuously more accurate.

AI-powered exploration could potentially increase geothermal capacity to 600 gigawatts, a tenfold increase over conventional estimates for 2050. Estimated data.

Why Traditional Geothermal Companies Missed This Opportunity

You might wonder: if this is so obvious, why didn't existing geothermal companies do this years ago?

The answer is depressingly simple. Traditional geothermal companies were treating geothermal as a mature industry. They had worked out how to drill wells, build power plants, and operate geothermal facilities. Their competitive advantages were in execution, not exploration. They had teams of drilling engineers and plant operators, but they didn't have machine learning researchers.

Moreover, the venture capital funding model didn't align with geothermal exploration. Venture capitalists want to fund companies building new technology—something that didn't exist before that they can patent and protect. Applying machine learning to geothermal exploration is clever, but it's not fundamentally new in the sense that the underlying geothermal resource exists. It's just that nobody found it before.

Traditional venture capitalists have been more excited about enhanced geothermal systems, which genuinely do represent new technology. EGS uses hydraulic fracturing to create artificial heat exchangers in hot rock formations. It's novel. It's patentable. It could potentially unlock geothermal resources in places without natural convection. It's the kind of "moon shot" technology that venture capitalists love.

But here's the problem with focusing entirely on technology moonshots: sometimes the boring, proven approach that nobody's properly explored yet creates more near-term value. Conventional geothermal is proven technology. The barrier to expanding it wasn't some missing scientific breakthrough. It was just that nobody had looked carefully enough for the resources.

Zanskar's founders recognized this gap. They understood that machine learning has transformed many industries by enabling better pattern recognition and prediction. Why not geothermal? Why not apply these tools to the boring, proven technology that's been stagnating?

The Capital Structure: Why $115 Million Changes the Game

Zanskar's Series C funding round brought in $115 million led by Spring Lane Capital. That's a substantial amount of capital, and understanding where it goes reveals a lot about how the company plans to execute.

In venture-backed geothermal companies, capital typically goes to three places: exploration and drilling, infrastructure development, and operating costs. For Zanskar, that Series C funding represents a massive acceleration in the pace at which they can move from "we've identified promising sites" to "we're developing geothermal power."

Think about the timeline for drilling a geothermal well. From decision to drill, you're looking at months of permitting, weeks of on-site preparation, and then weeks of drilling itself. Each well can cost millions. You might drill multiple test wells at a single site before committing to production wells. Multiple that by dozens of sites in their pipeline, and you're talking about tens of millions of dollars just on drilling costs.

The capital structure of the funding round is also revealing. Spring Lane Capital led the round, but the syndicate includes institutional investors like Clearvision Ventures, Lower Carbon Capital, and Munich Re Ventures. The inclusion of Munich Re Ventures is particularly significant. Munich Re is the world's largest reinsurer. They have enormous experience assessing risk in energy and infrastructure projects. Their participation signals that sophisticated risk investors see real merit in Zanskar's approach.

Union Square Ventures, another lead backer of Zanskar, has a track record of funding infrastructure and climate companies. The breadth of the syndicate—over a dozen different investment firms participated—suggests this isn't a bet from one firm. Multiple sophisticated investors have independently concluded that this is worth capital.

From a business model perspective, Zanskar faces an interesting challenge. They can't directly monetize exploration. You don't make money finding geothermal resources; you make money developing them into power plants and selling electricity. So what's their path to profitability?

Likely scenarios include: partnering with utilities or infrastructure companies to develop the sites they identify, receiving upfront payments or revenue sharing from partners, or potentially developing projects themselves if they can raise project-level financing. This is where reaching that 10-site confirmation milestone becomes crucial. Project finance investors—the massive institutional capital sources that fund infrastructure—typically require a pipeline of confirmed, de-risked projects before committing capital.

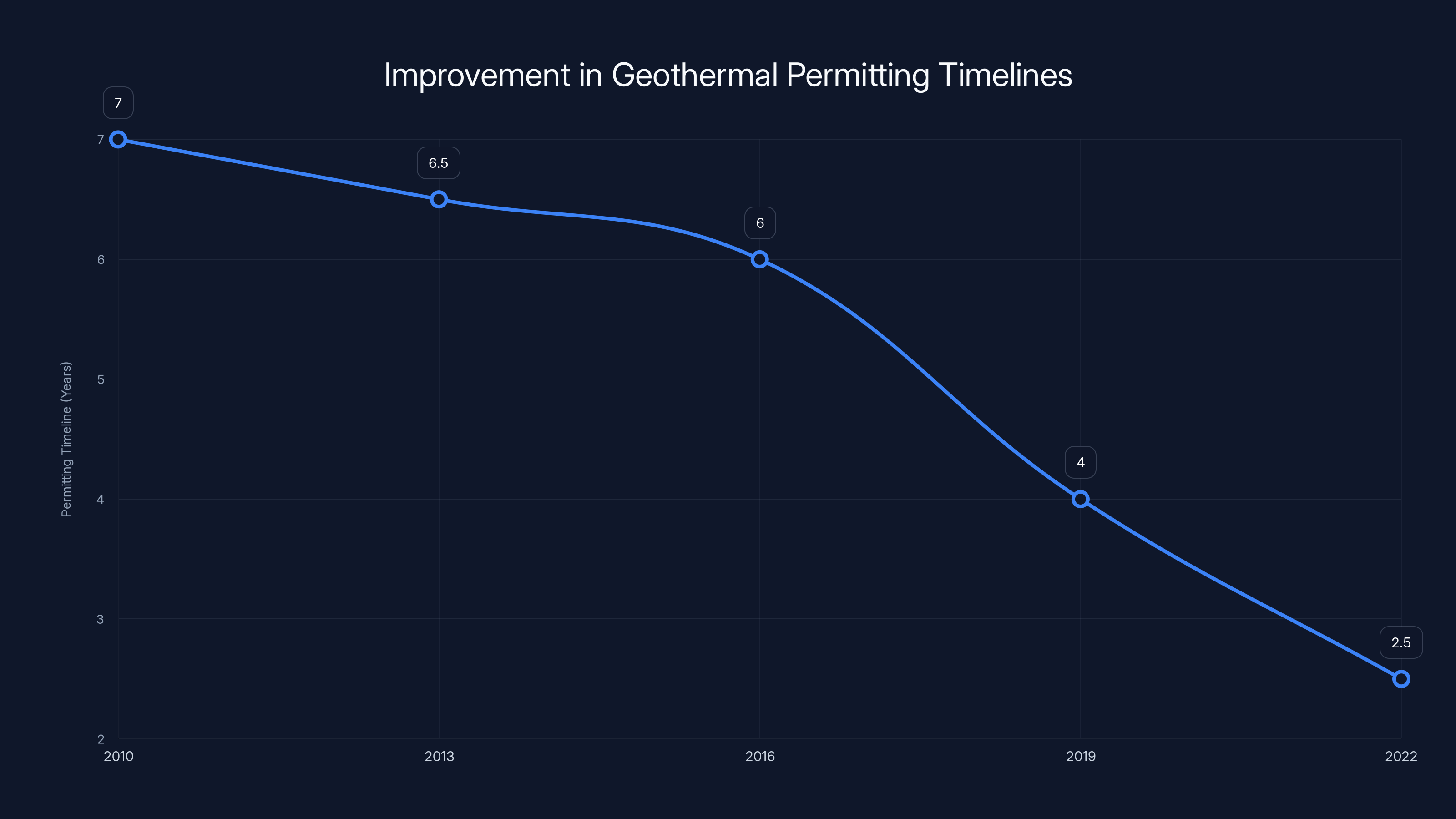

Estimated data shows a significant decrease in geothermal permitting timelines from 7 years in 2010 to approximately 2.5 years in 2022, thanks to streamlined processes and improved regulatory frameworks.

The Competitive Landscape: EGS vs. Conventional Geothermal

The geothermal energy space isn't just Zanskar. There are other companies pursuing different strategies, and understanding the competitive dynamics is important.

On one side, you have enhanced geothermal systems companies. Fervo Energy and Sage Geosystems are the two most notable EGS companies that have secured significant venture funding. Both are pursuing the same basic idea: use fracking technology to create artificial geothermal reservoirs. Fervo has demonstrated their technology at a demonstration plant in Texas. Sage is pursuing projects in various locations.

EGS has genuine advantages. It can work in more geographic locations because it doesn't depend on finding naturally fractured hot rock. In principle, you could do EGS almost anywhere with hot rock deep enough to be useful. This broader geographic applicability has attracted massive investment. The Department of Energy has allocated substantial funding toward EGS research and demonstration projects.

But EGS also has challenges. The technology is still being proven. Commercial-scale EGS plants don't yet exist. There are questions about cost, about whether you can achieve adequate heat extraction rates to justify the capital investment, about whether the reservoirs remain productive over decades. These are all solvable problems, but they're real problems. Every EGS demonstration plant teaches lessons that lead to design improvements.

Conventional geothermal, by contrast, is proven at scale. Hundreds of geothermal power plants operate worldwide, producing gigawatts of electricity reliably. The technology is mature. The plants operate at high capacity factors—averaging 70-90% uptime, compared to about 30% for solar and 35% for wind. The economics are well understood.

The innovation at Zanskar isn't technological; it's methodological. They're applying AI to find conventional geothermal resources more efficiently. This creates an interesting dynamic: Zanskar is probably a better near-term bet for adding geothermal capacity, while EGS companies are pursuing longer-term potential.

From a policy perspective, this matters. If you're a utility or a policymaker trying to add dispatchable renewable energy capacity over the next 5-10 years, Zanskar's approach gets you there faster. If you're thinking 20-30 years out and want to transform the long-term energy landscape, EGS might be more important. But for meeting near-term climate goals, conventional geothermal expansion via better exploration probably delivers more megawatts per invested dollar.

The "Valley of Death" Problem: Why This Funding Matters

Climate tech startups die in what industry observers call the "valley of death." They survive the startup phase, prove their technology works, and then hit a wall trying to scale up. The problem is that clean energy infrastructure requires massive capital, regulatory approval, and long development timelines. Venture capital is great for funding R&D and early-stage development. It's terrible for funding $500 million infrastructure projects.

Zanskar was at risk of hitting this valley. They'd proven their AI exploration approach worked. They'd made discoveries. But developing those discoveries into actual power plants requires capital that venture firms aren't comfortable deploying. Project finance—the institutional investors and infrastructure funds that typically back energy projects—are incredibly conservative. They want proven technology, predictable revenue, and management teams with track records.

Zanskar's Series C funding is specifically designed to cross this valley. By confirming at least 10 viable sites, they create a pipeline of de-risked projects that project finance investors can evaluate. Each confirmed site represents a discrete investment opportunity. Instead of project finance investors betting on Zanskar as a company, they're betting on specific geothermal projects with clear timelines and economics.

This is actually the smart way to structure a geothermal company. Proven, conventional geothermal projects can attract project finance at reasonable interest rates—often lower than venture capital returns expectation. Once you have a pipeline of projects, you can attract institutional capital that makes venture returns look expensive. This creates a path to profitability that doesn't depend on venture capital exiting at a premium valuation.

The challenge is getting through the valley. Getting from "we've found something" to "we have 10 confirmed, financeable projects" requires capital and time. If Zanskar had run out of money before proving this, they'd have been just another clean tech casualty. This funding round essentially guarantees they'll have the runway to prove it works.

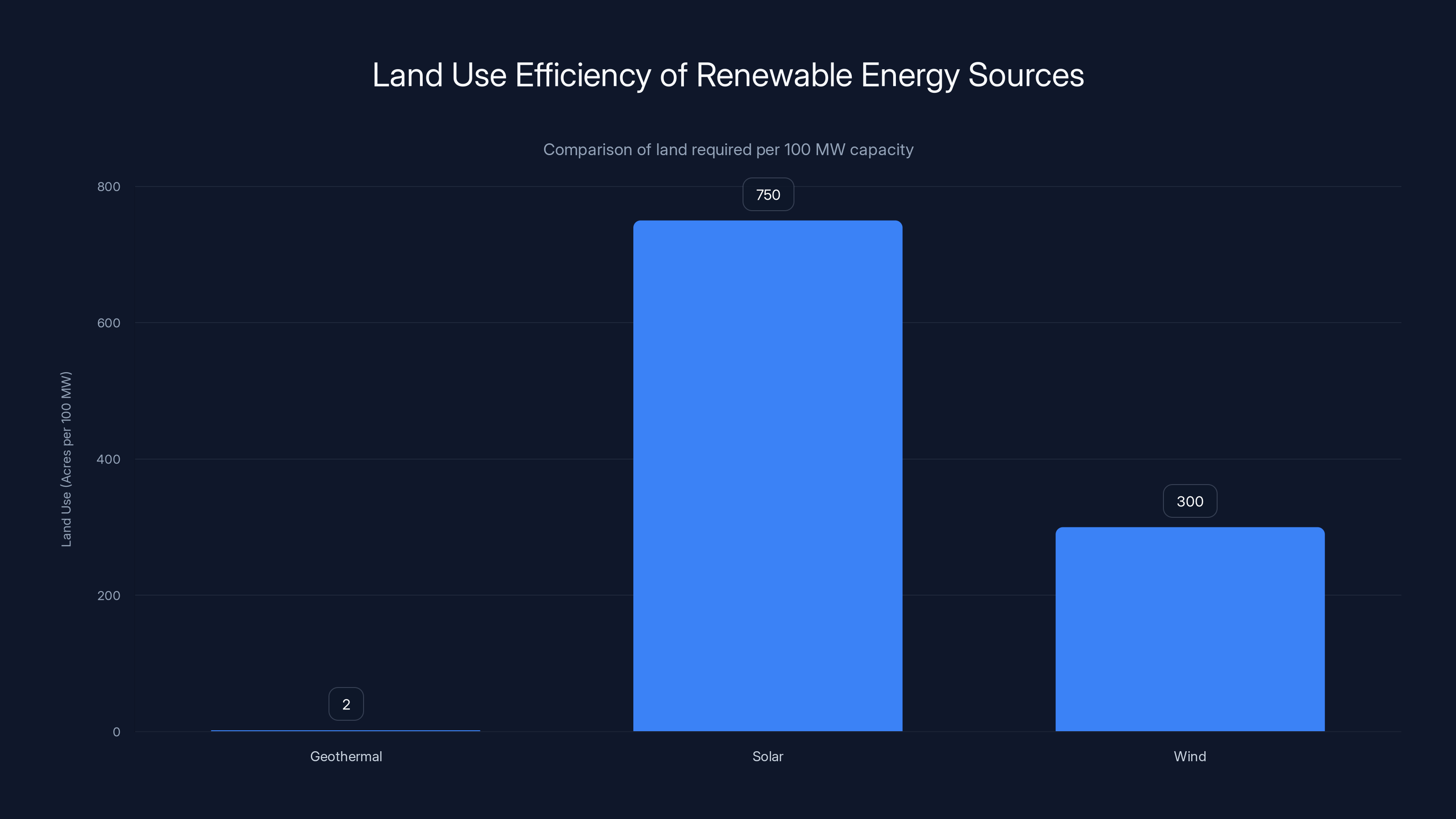

Geothermal power plants require significantly less land than solar and wind farms, with a footprint about 50 times smaller than solar per megawatt. Estimated data based on typical installations.

Regulatory and Permitting Landscape: The Often-Overlooked Barrier

One of the most underrated challenges in deploying geothermal energy isn't technical or financial. It's regulatory.

Geothermal development requires permits at multiple levels. You need permits to conduct exploration drilling. You need environmental impact assessments. You need permits to build power plants. You need grid interconnection agreements. In the western United States, you're often dealing with federal land—Bureau of Land Management (BLM) territory—which adds another layer of bureaucracy.

The good news is that permitting timelines for geothermal have actually improved over the past few years. Federal agencies have recognized the climate importance of geothermal and have streamlined processes. What used to take 5-7 years for BLM approval can now potentially happen in 2-3 years with proper preparation.

But here's where Zanskar's focus on conventional geothermal and existing sites provides an advantage. Many of the existing geothermal areas already have permitting history and environmental baseline data. The New Mexico site they're revitalizing already has decades of operating history and permitting precedent. That enormously simplifies the regulatory process for new development at the same location.

Furthermore, AI-powered exploration that produces high-confidence predictions can actually help with permitting. Environmental reviews are required before drilling, but if you can present compelling evidence about why a specific location has geothermal potential, you're likely to get more favorable consideration than if you're drilling based on less rigorous methodology.

The regulatory landscape also includes power purchase agreements—contracts between utilities and power generators that determine pricing and terms. Geothermal has an advantage here too. Utilities strongly prefer reliable, dispatchable power sources that they can depend on. Compared to solar and wind, geothermal is attractive to grid operators even if the cost per kilowatt-hour is slightly higher, because it provides predictability.

Grid Integration and the 24/7 Clean Energy Advantage

Here's something that often gets lost in climate discussions: having 100% renewable energy is harder than having 80% renewable energy plus some baseload power.

Solar and wind are intermittent. The sun doesn't always shine; the wind doesn't always blow. As renewables penetration increases, you face an increasingly acute problem: what powers the grid on a cloudy, calm day?

Various solutions exist: battery storage, pumped hydro, demand flexibility, geographic distribution of wind farms. But all of these add cost and complexity. A simpler solution: have some sources of dispatchable renewable power that you can turn on when needed.

Geothermal is exactly that. You can ramp production up or down based on grid demand. You can run at full capacity 24/7 or dial it back. This operational flexibility makes geothermal extraordinarily valuable from a grid operations perspective.

When utilities are planning their generation mix, they need: firm baseload power, peaking capacity, and mid-merit plants that fill gaps. Geothermal fits beautifully into the mid-merit category. It can provide capacity at whatever level the grid needs, whenever needed.

There's also the question of land use efficiency. Solar and wind require enormous land areas to generate equivalent power. Geothermal plants occupy small footprints. A 100-megawatt geothermal plant might occupy a few acres. A 100-megawatt solar farm might occupy 500-1,000 acres. For a resource-constrained region like the American West, where land use is politically contentious, geothermal's land efficiency is a major advantage.

Economic Modeling: The Real Cost of Geothermal Power

Let's talk about economics because this is ultimately what determines whether geothermal expansion actually happens.

Geothermal power has favorable economics compared to many other electricity sources, but the specifics matter. The capital cost of building a geothermal power plant is high—typically

But capital cost is only part of the equation. Operating costs matter too. Geothermal has exceptionally low operating costs—typically

The economic advantage of geothermal emerges when you calculate the levelized cost of electricity (LCOE)—the total cost per megawatt-hour accounting for capital costs, operating costs, and expected lifetime. For geothermal, with a 30-40 year plant lifespan and high capacity factors, LCOE typically comes out to $50-70 per megawatt-hour.

That's competitive with modern renewables plus storage, cheaper than nuclear, and often cheaper than natural gas when you account for carbon pricing in states with carbon markets.

But there's a crucial detail: this economics only works if exploration is cheap. If you have to spend $20 million on exploration to find each gigawatt of resources, that changes the math. If AI-powered exploration drops exploration costs by 80-90%, geothermal becomes dramatically more economically attractive.

This is where Zanskar's innovation creates real value. By making exploration cheaper and faster, they're improving the economics of every subsequent geothermal project. They're not building power plants themselves—that's not their business model. But they're reducing the cost and risk for everyone else developing geothermal.

Climate Impact: What Adding a Terawatt Really Means

To contextualize what terawatt-scale geothermal could mean for climate, let's do some basic math.

Electricity generation accounts for about 25% of U. S. greenhouse gas emissions. A terawatt of geothermal capacity running at 80% capacity factor would generate roughly 7,000 terawatt-hours per year of clean electricity. That's more than 50% more than U. S. electricity consumption today.

In carbon terms, replacing fossil fuel generation with geothermal at that scale would eliminate several hundred million tons of CO2 annually. For context, total U. S. energy sector emissions are roughly 6,500 million tons per year. So we're talking about maybe 5-7% of total energy emissions, just from geothermal.

That's not insignificant. It's not the entire solution to climate change. But it's a material piece of the puzzle. And it's baseload power—the kind of reliable, dispatchable electricity that's hardest to replace with renewable sources.

Moreover, if the terawatt potential is as real as Zanskar's founders believe, and if you can eventually expand beyond the U. S. West, the global implications are enormous. The western U. S. is geologically fortunate but not unique. Similar geothermal resources exist in other tectonically active regions around the world.

The global question becomes: if AI-powered geothermal exploration works as well in New Zealand, Chile, Iceland, Indonesia, and other geologically favorable regions as it does in Nevada, how much total global capacity could be unlocked? That's a scenario where geothermal genuinely moves from niche energy source to a meaningful contributor to global decarbonization.

Timeline Expectations: When Could This Scale?

One reasonable question: if this is so promising, when do we actually see gigawatts of new geothermal capacity coming online?

Timelines in energy infrastructure move slower than most people expect. Even moving very quickly, developing a geothermal project from identified site to producing power takes 3-5 years. That includes: confirming resources, permitting, financing, construction, and grid interconnection. You can't shortcut this process much.

So even if Zanskar identifies 50 sites in the next 3 years, actual production from those sites is probably 5-7 years out. The Company's interim goal of confirming 10 sites is designed to create a pipeline of projects that can be developed simultaneously, so that years 5-7 see multiple projects coming online in parallel.

But here's the realistic scenario. Over the next decade, if everything goes well:

- Year 1-2: Zanskar and competitors identify and confirm 20-30 new sites

- Year 3-4: Of these, perhaps half move to project finance stage and construction begins

- Year 5-7: First projects come online; new projects enter construction

- Year 7-10: Cumulative capacity ramps up significantly

By 2035, if this timeline holds, the U. S. could have 5-10 additional gigawatts of geothermal capacity online beyond current levels. That's not transformational, but it's meaningful. And it's achievable with existing proven technology and methods.

The really transformational scenario requires EGS also working and scaling, which is still uncertain. If both conventional geothermal expansion (via better exploration) and EGS development both succeed, then you could be looking at terawatt-scale deployment globally by mid-century.

The Road Ahead: What Needs to Happen for This to Work

For Zanskar and the broader conventional geothermal opportunity to actually materialize, several things need to happen.

First, the exploration needs to continue paying off. They've had great initial success, but they need to prove it wasn't a fluke. Finding 3 out of 3 sites is great. Finding 3 out of 10 and then improving from there is normal. They need to demonstrate consistent, reproducible success across different geologic provinces and conditions.

Second, they need to successfully transition from exploration company to a company that can coordinate project development. Even if they don't build power plants themselves, they need to partner effectively with utilities, infrastructure companies, and project developers. This requires business development and relationship management skills different from the technical skills needed for exploration.

Third, they need to secure project financing. This is perhaps the most important hurdle. Venture capital got them to the point of having a promising pipeline. Now they need to prove that utilities and infrastructure investors want to fund development of these sites.

Fourth, they need policy support. Tax credits for renewable energy, regulatory certainty on geothermal, streamlined permitting—all of these help. The current policy environment is reasonably favorable, but geothermal has historically been neglected compared to solar and wind. If policy swings, it could help or hurt.

Finally, they need the broader industry to adopt their approach. If only Zanskar is finding new geothermal sites while every other exploration company continues using old methods, the impact is limited. Real transformation requires the industry as a whole to adopt AI-powered exploration methodologies.

The good news is that there's economic incentive for this. Once Zanskar proves the approach works, competitors will emerge. The idea of using AI to find geothermal resources isn't proprietary in principle—it's just an application of existing tools to a specific problem. Other companies will copy it, improve it, and deploy it.

Geothermal's Role in the Broader Clean Energy Transition

Geothermal doesn't get the attention that solar and wind do. It's not as visually dramatic as a field of solar panels or a wind farm. But from an energy system perspective, it fills a critical role.

The challenge with transitioning to 100% clean electricity is that solar and wind are wonderful but intermittent. You need baseload power. You need something you can rely on at 2 a.m. when there's no wind and no sun. Your options are: nuclear (which is great but expensive and slow to build), hydroelectric (great but geographically limited), biomass (renewable but limited by sustainable fuel supply), battery storage (improving but expensive at scale), or dispatchable renewable sources like geothermal.

Geothermal is the most elegant solution because it's renewable, clean, reliable, and increasingly economical. The only barrier has been that we weren't looking for it carefully enough.

If Zanskar and companies like it successfully unlock the conventional geothermal potential, you suddenly have a significant source of reliable clean power that can be deployed wherever it exists. That doesn't solve the entire energy problem—you still need solar, wind, nuclear, and storage—but it makes the overall energy system more feasible.

From a grid operator's perspective, having 10% of generating capacity from reliable geothermal is valuable. It reduces the need for grid-scale storage. It reduces curtailment of renewable generation. It improves reliability and stability.

There's also a geographic dimension. The western U. S. is where most of the geothermal potential exists, but it's also where some of the strongest solar resources exist. A region that combines geothermal baseload with solar and wind for peak generation is approaching an optimal energy portfolio.

Conclusion: The Next Decade for Geothermal

The geothermal energy opportunity that Zanskar is pursuing represents something important: value from careful application of modern tools to proven but stagnating approaches.

We often think of energy innovation as requiring breakthrough technology. New forms of batteries, new nuclear designs, new ways to capture sunlight. Sometimes innovation is just looking more carefully at what's already working.

Conventional geothermal works. It's proven, reliable, scalable, and increasingly economical. The barrier was simply that we weren't finding enough resources. Applying AI to geothermal exploration removes that barrier.

If the company executes well, if the projects they identify get developed, and if other companies adopt similar approaches, the next decade could see a genuine resurgence in geothermal development. Not the transformational terawatt-scale deployment in 5 years that the most optimistic projections suggest, but meaningful growth. Perhaps doubling U. S. geothermal capacity by 2035. Perhaps reaching 10-15 gigawatts of new capacity from AI-identified sites.

That's not a small thing. That's the equivalent of building 10-15 large natural gas plants worth of reliable clean power. That's several percentage points of U. S. electricity supply. That's hundreds of millions of tons of CO2 that won't be emitted.

The capital is in place. The technology is proven. The market opportunity exists. The remaining question is execution. Can Zanskar deliver on the promise? Can they identify, finance, and develop projects at scale? Can they do it faster than the inevitable tide of regulatory and permitting complications?

Based on the early evidence and the quality of the capital behind them, the answer seems likely to be yes. The next 2-3 years will tell us whether geothermal's second act is actually beginning.

FAQ

What exactly is conventional geothermal power?

Conventional geothermal power harnesses naturally fractured hotspots deep underground where water or steam circulates through hot rock and can be accessed by drilling wells. Unlike enhanced geothermal systems that artificially create fractures, conventional geothermal taps into existing natural reservoirs that have been accumulating heat for millions of years. The heated water or steam is brought to the surface, used to drive turbines that generate electricity, and then reinjected back into the ground to maintain the system. This technology has been proven and operational worldwide for decades, with some plants operating continuously for 40+ years.

How does AI actually find geothermal resources?

AI discovers geothermal resources by analyzing massive datasets of geological, geophysical, and drilling information using supervised machine learning and Bayesian modeling. The algorithms learn patterns from known geothermal sites—identifying common characteristics like specific rock types, seismic signatures, temperature profiles, and magnetic anomalies—then apply those patterns to unexplored regions to identify areas with similar characteristics. The machine learning models calculate probability scores for each potential site, Bayesian analysis quantifies uncertainty, and specialized geothermal simulators fill data gaps by modeling thousands of plausible subsurface scenarios. Rather than relying on traditional exploration methods that only identify surface features, AI pattern recognition can identify the 95% of geothermal systems that show no visible surface expression.

Why has geothermal been overlooked for so long?

Geothermal has been overlooked because traditional exploration relied on visible surface features like hot springs, geysers, and volcanic activity to identify promising drilling locations. Since roughly 95% of geothermal systems lack these surface indicators, conventional exploration methods consistently missed the vast majority of available resources. Additionally, the energy industry focused its innovation efforts on enhanced geothermal systems (EGS) and other new technologies, treating conventional geothermal as a mature, stagnant sector. Investment capital flowed toward technological breakthroughs rather than methodological improvements in finding existing resources. The combination of limited exploration, historical underestimation of undiscovered resources, and focus on EGS innovation created a self-fulfilling prophecy where geothermal appeared to have limited potential simply because nobody was looking carefully enough.

What's the difference between conventional geothermal and enhanced geothermal systems (EGS)?

Conventional geothermal requires naturally fractured rock formations and naturally circulating hot water or steam that can be accessed by drilling. Enhanced geothermal systems use hydraulic fracturing (similar to oil and gas fracking) to artificially create fracture networks in hot rock formations that lack natural permeability, enabling geothermal extraction from a much broader geographic area. EGS is more flexible in terms of location since you can theoretically create the fractures anywhere you have hot rock deep enough, but the technology is still being demonstrated and proven at commercial scale. Conventional geothermal is proven, reliable technology but geographically limited to areas with natural convection. Both approaches have value; conventional geothermal can be expanded relatively quickly with existing technology, while EGS represents longer-term potential to transform geothermal deployment worldwide.

How much capacity could new geothermal exploration actually add?

Zanskar and industry experts believe that improved exploration could unlock 25-50 times more geothermal capacity than current levels across the United States, potentially reaching terawatt scale through a combination of identifying previously undiscovered sites and extracting more power from each site using modern drilling techniques. More conservatively, if improved exploration methods identify even 10-20 times more viable conventional geothermal sites than currently known, and each site generates 1-5 megawatts on average, you're looking at 10-100 gigawatts of additional U. S. capacity. The actual number depends on successful execution, project financing, and regulatory timelines, but even reaching just 5-10 additional gigawatts by 2035 would roughly double current U. S. geothermal capacity.

What does Zanskar's $115 million funding actually pay for?

Zanskar's Series C funding covers the costs of accelerating exploration, conducting test drilling at identified sites, building relationships with potential project partners, and de-risking projects sufficiently to attract project finance investors. Specifically, the capital goes toward continued AI model development and validation, field exploration teams, drilling operations for test wells, business development activities, and maintaining operations through the period until project development partners take over financing. The goal is to build a pipeline of 10+ confirmed, financing-ready projects that can be handed off to utilities and infrastructure developers who will fund the actual power plant construction. This bridges the "valley of death" where companies have proven their concept but aren't yet ready for the scale of capital required for infrastructure deployment.

When would new geothermal projects actually start producing electricity?

Project development timelines from confirmed geothermal site to producing power typically require 3-5 years for permitting, environmental review, detailed engineering, financing, and construction. This means that geothermal sites identified and confirmed today would likely begin generating power in 2027-2029 at the earliest. The more realistic scenario is staggered development where projects begin construction at different times, resulting in new capacity coming online gradually between 2028 and 2032. Existing proven sites that are being re-developed (like the New Mexico location Zanskar identified) can move faster, potentially producing within 2-3 years, since much of the permitting infrastructure and baseline data already exists.

How does geothermal's reliability compare to solar and wind?

Geothermal operates at 70-90% capacity factors—meaning it produces power at maximum or near-maximum capacity roughly 70-90% of the time. Solar averages about 25-30% capacity factor due to nighttime and cloud cover, while wind averages 35-45% depending on location. This means geothermal produces power much more consistently and reliably, making it extraordinarily valuable to grid operators who need dependable electricity supply. From a grid stability perspective, geothermal's 24/7 consistent production is worth more per megawatt than solar or wind, even if total installed capacity is smaller. This is why utilities actively seek geothermal resources—not as a replacement for renewables, but as essential baseload power that reduces the need for energy storage and backup capacity.

Use Case: Automate energy project reports and resource assessments with AI-powered document generation, saving your team hours on data compilation and analysis.

Try Runable For Free

Key Takeaways

- Conventional geothermal's potential has been drastically underestimated due to 95% of geothermal systems showing no surface expression, making them invisible to traditional exploration methods

- AI-powered exploration can find geothermal resources 25-50x more efficiently, potentially unlocking terawatt-scale capacity that could provide 10% of U.S. electricity generation

- Zanskar's $115M Series C funding validates the commercial viability of AI-driven geothermal exploration and addresses the critical 'valley of death' between venture funding and project finance

- Geothermal's 70-90% capacity factor dramatically exceeds solar (25-30%) and wind (35-45%), making it invaluable for grid reliability and baseload power requirements

- 3-5 year project timelines mean AI-discovered sites could begin producing electricity by 2027-2029, enabling gradual but meaningful capacity additions throughout the 2030s

Related Articles

- Climate Tech Investing in 2026: What 12 Major VCs Predict [2025]

- Type One Energy Raises $87M: Inside the Stellarator Revolution [2025]

- Offshore Wind Developers Sue Trump: $25B Legal Showdown [2025]

- Airloom's Vertical Axis Wind Turbines for Data Centers [2025]

- AI Data Centers & Carbon Emissions: Why Policy Matters Now [2025]

- UK Electric Car Campaign: 5 Critical Roadblocks the Government Ignores [2025]

![The Hidden Terawatt: Why 1TW of Geothermal Power Is Being Ignored [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/the-hidden-terawatt-why-1tw-of-geothermal-power-is-being-ign/image-1-1769002850221.jpg)