Introduction: When Presidential Power Hits a Wall

Last month, something extraordinary happened in American politics. A sitting president issued what he called a "pardon" for a woman sitting in a Colorado prison. The announcement came across Truth Social with characteristic flair: "Tina is an innocent Political Prisoner," the post read. Harsh language. Strong sentiment. The kind of declaration that would normally set legal wheels in motion.

Except nothing happened. The woman stayed in her cell. No legal machinery kicked into gear. No federal agents rushed to Colorado. The pardon, it turned out, was essentially theater.

Welcome to the Tina Peters case: the collision between presidential ambition and constitutional reality. It's a story about election denial, state versus federal power, political pressure, and the surprising limits of even the most aggressive executive branch. It's also a window into how conspiracy theories get weaponized, how they become rallying cries, and what happens when powerful people decide someone deserves special treatment based on ideology rather than law.

Tina Peters wasn't a major figure before 2021. She was a county clerk in Mesa County, Colorado, working in election administration. Thousands of people do similar work across the country, managing voter rolls, training poll workers, maintaining the unsexy machinery that makes democracy function. But Peters took a different path. And that path has led her to a medium-security women's prison in Pueblo, Colorado, where she's currently serving time for a scheme that still reverberates through election denial circles.

What makes this case interesting isn't just Peters or her legal fate. It's what it reveals about the Trump administration's willingness to pressure states, about the elevation of election deniers into martyr status, and about how far constitutional boundaries actually stretch when a president is determined to test them. Colorado's governor, Jared Polis, has resisted that pressure so far. But he's also signaled willingness to consider clemency. If he grants it, the message would be clear: election deniers with powerful allies can expect mercy from sympathetic executives, regardless of conviction details.

Let's start with what actually happened.

The Mesa County Breach: How It Started

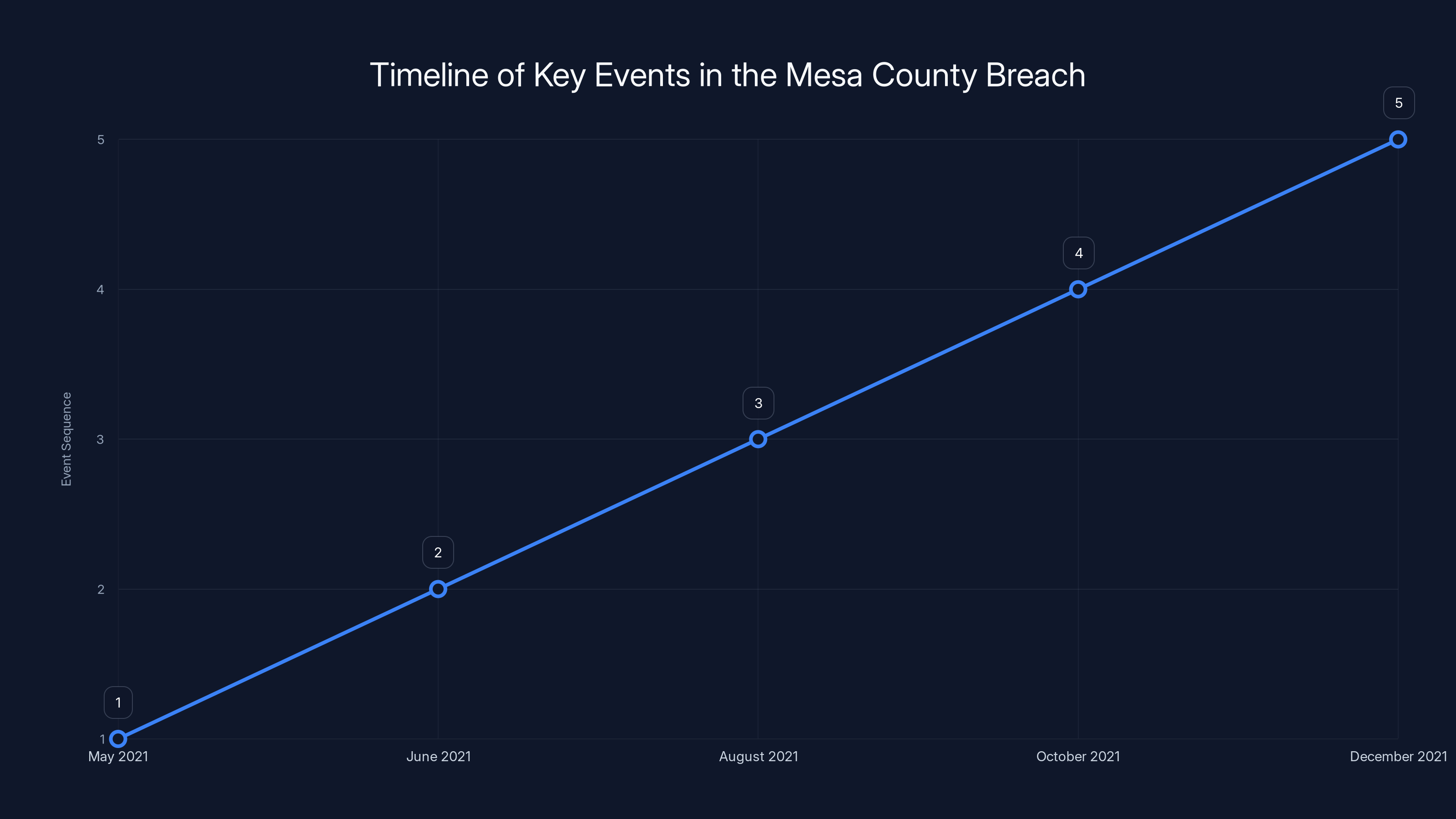

May 2021 feels like ancient history in election denial circles, but it's when this story ignited. Peters made a choice that would define her career and land her in prison: she allowed someone unauthorized access to Colorado election equipment.

The person she allowed in was Conan Hayes, a former professional surfer who'd become entangled with Mike Lindell's election fraud conspiracy circles. Hayes used credentials that didn't belong to him—someone else's credentials that Peters facilitated him using—to watch a software update of Mesa County's election management system. This wasn't some minor breach. Election management systems are the infrastructure that counts votes. They're protected for good reason. Unauthorized access, even to watch an update, crosses serious legal and operational lines.

Why did Peters allow this? She claimed then, and claims now, that she was concerned about election security. She believed—without evidence—that the 2020 election had been stolen from Trump. She thought if she could get someone inside the system, they might find proof. She was wrong about the underlying claim. Elections officials across the country, including those appointed by Trump himself, verified that 2020 was secure. Trump's own Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency called it "the most secure election in American history."

But in conspiracy theory circles, evidence is secondary to narrative. After Hayes obtained the data from Mesa County's election systems, it found its way online. Ron Watkins, a prominent QAnon promoter, published it. The Gateway Pundit, a website steeped in conspiracy content, amplified it. Election deniers seized on it as vindication, as proof that the election had been rigged, as evidence that the system was corrupt.

Hayes was never charged with a crime. He'd simply been the physical access point, the surfer who followed instructions. Peters, who actually made the decision to let him in, was the one the system pursued.

The charges came in March 2022, more than nine months after the breach. By that point, Peters had already decided to run for Colorado Secretary of State—essentially the state's top election official. It's worth pausing on that decision. Peters had just breached election equipment. She'd allowed unauthorized access. She was now running for the position that would oversee all elections in Colorado. The audacity or the conviction in her own righteousness is striking, depending on your view.

She lost that election, badly. In the Republican primary, she came in fourth place, losing by over 88,000 votes. Then she questioned the results. She demanded a recount, convinced that the primary results were themselves rigged. The recount added 13 votes to her total. She still lost, by a wider margin. That loss, incidentally, came in June 2022, with charges pending against her.

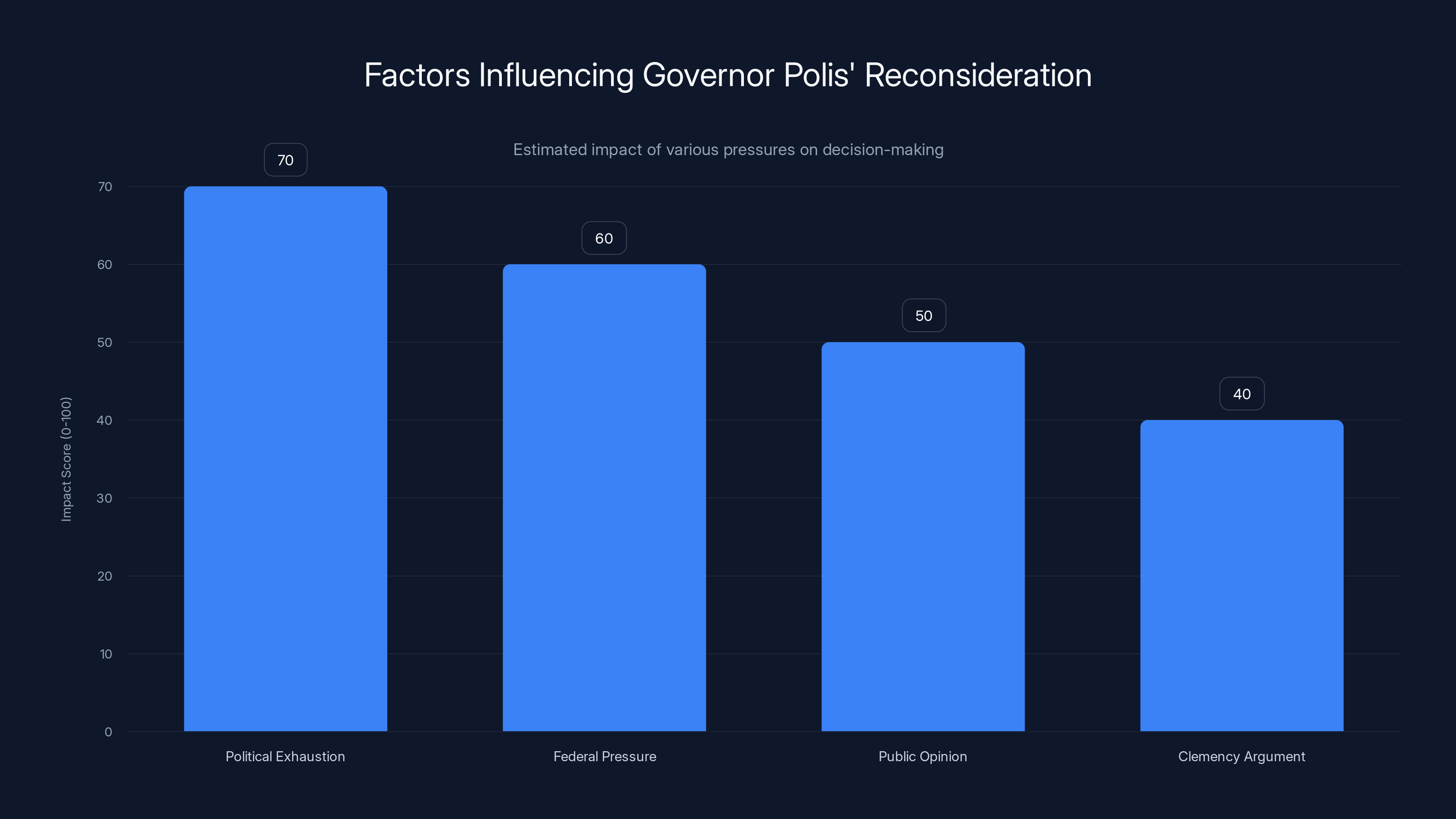

Estimated data suggests political exhaustion and federal pressure are significant factors influencing Governor Polis' reconsideration of Peters' case.

The Conviction: What the Charges Actually Were

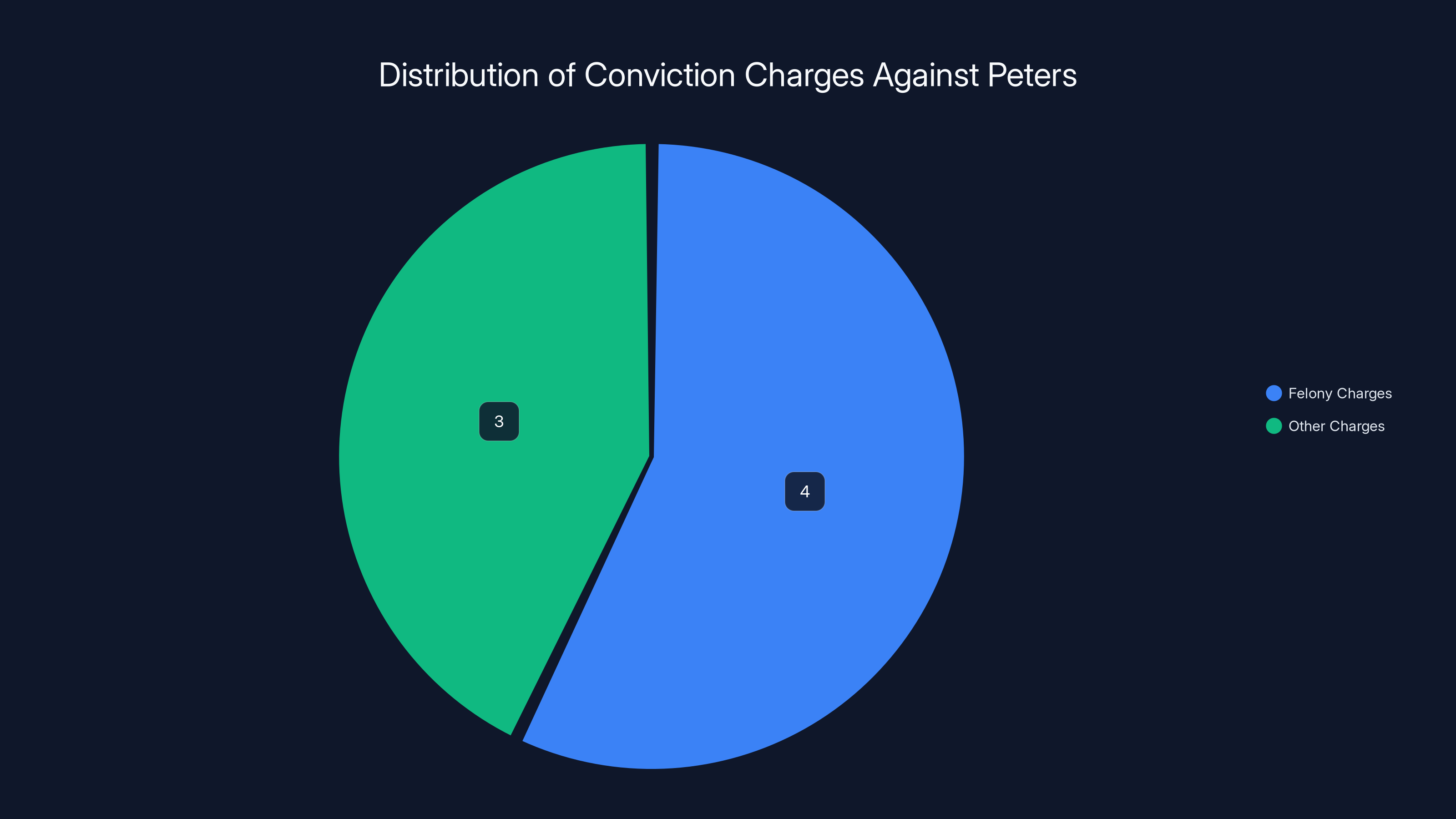

In August 2024, after a trial, Peters was convicted on seven of the ten charges she faced. Four of those were felonies. Let's be specific about what she was convicted of, because the details matter when discussing whether this was political persecution or legitimate prosecution.

She was convicted of: illegally accessing a computer system, attempting to affect the outcome of an election, computer crime, conducting an unlawful scheme concerning elections, violation of computer access statutes, and other election-related offenses. These aren't abstract charges. These are crimes directly tied to the action she took: giving someone unauthorized access to election equipment.

The prosecution didn't need to prove she intended to actually change votes. They needed to prove she acted with intent to affect the election outcome and that she knew she didn't have authorization to give someone else system access. Both of those things appear on the record. She gave Hayes access. She knew he wasn't authorized. She did it expecting it would uncover election fraud.

At her sentencing hearing in October 2024, the judge offered a scathing assessment. Matthew Barrett, the district judge, looked at Peters directly and said: "You are no hero. You're a charlatan who used and is still using your prior position in office to peddle snake oil that's been proven to be junk time and time again."

The judge sentenced her to nine years in prison. She was remanded immediately to La Vista Correctional Facility, a medium-security women's prison in Pueblo. She'd have to serve that full sentence before becoming eligible for parole in September 2028.

Since her incarceration, Peters has maintained her innocence. She hasn't shown remorse. She hasn't acknowledged wrongdoing. She continues to present herself as someone fighting for election integrity, someone persecuted for questioning election systems. That narrative plays perfectly to her supporters. It plays terribly to anyone evaluating whether reducing her sentence makes sense from a criminal justice perspective.

The Martyr Industrial Complex: How Peters Became a Hero

The moment Peters was arrested, something shifted in how she was discussed in election denial circles. She wasn't a former county clerk who'd made a questionable decision. She became a martyr. A victim. Someone persecuted for asking the right questions.

This transformation didn't happen organically. It was encouraged by influential figures in the election denial community. Steve Bannon, the former Trump adviser, started campaigning for her release almost immediately. Michael Flynn, the disgraced former national security adviser, joined in. Online, in conspiracy forums, in right-wing media, Peters was reframed. She went from being someone who'd breached election systems to being someone bravely standing up to a corrupt election establishment that was trying to silence her.

The irony is thick. Peters is in prison not because she questioned elections, but because she took action that crossed legal lines while claiming to investigate election security. She didn't get convicted for her beliefs. She got convicted for her actions: unauthorized computer access and attempting to affect election outcomes. But in the martyr narrative, this distinction disappears. She's a hero being silenced.

This framing is powerful because it contains a kernel of legitimate grievance. People do disagree about election security. Questions about how voting systems work aren't inherently illegitimate. The problem is that Peters didn't just ask questions. She acted on false beliefs, breached secured systems, and allowed unauthorized access. When those facts are inconvenient to a narrative, they simply get reframed or omitted.

Why does this matter? Because when someone becomes a martyr in a political movement, their actual conduct matters less than what they represent. Peters represents the election denial movement's claim that they're being persecuted for challenging the 2020 results. She's exhibit A in the argument that the system is rigged against people asking the right questions. Freeing her would validate that entire narrative.

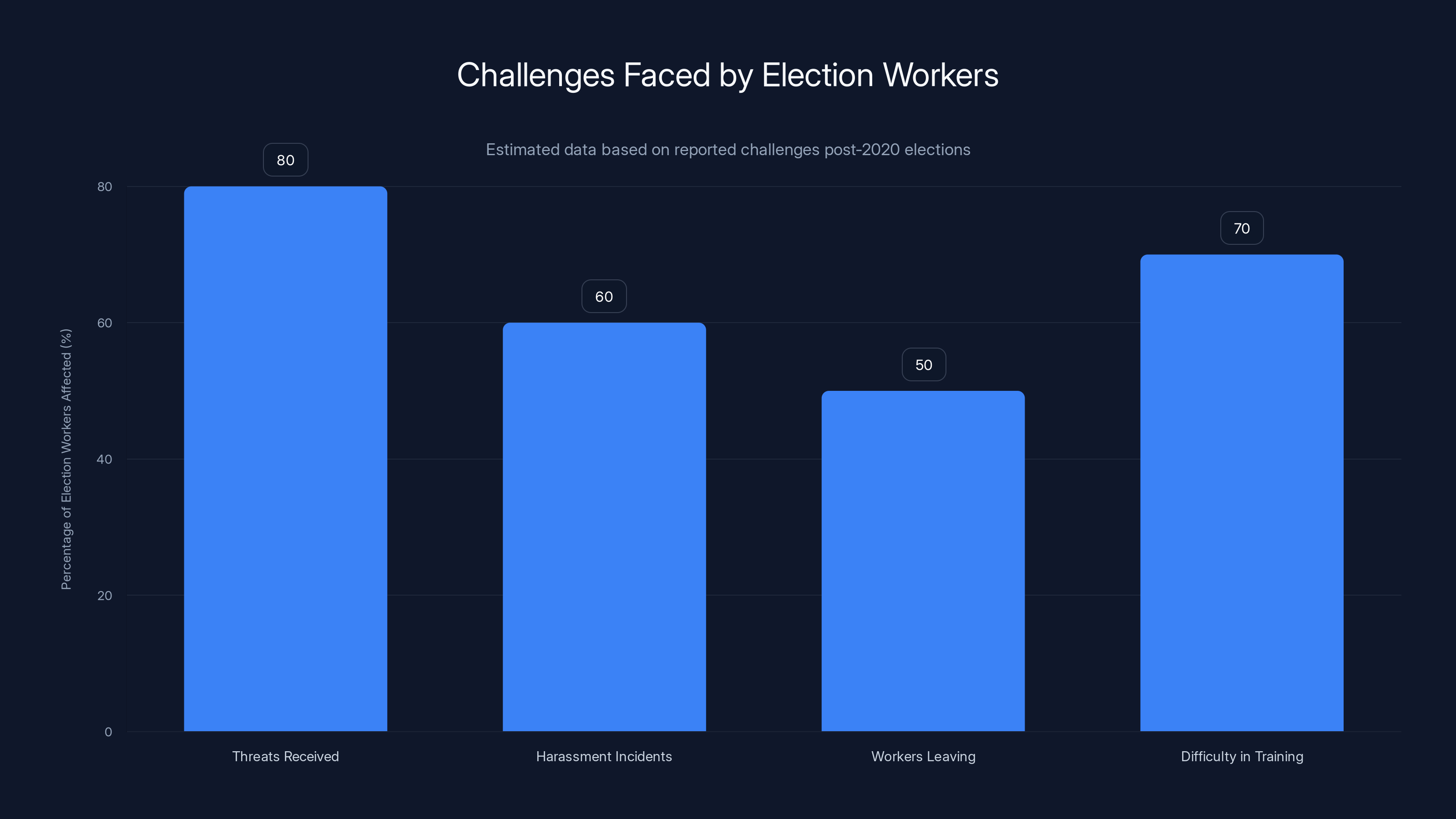

Estimated data suggests that a significant percentage of election workers have faced threats and harassment, leading to increased difficulty in retaining and training new workers. (Estimated data)

Trump's Interest: When Did This Become a Federal Issue?

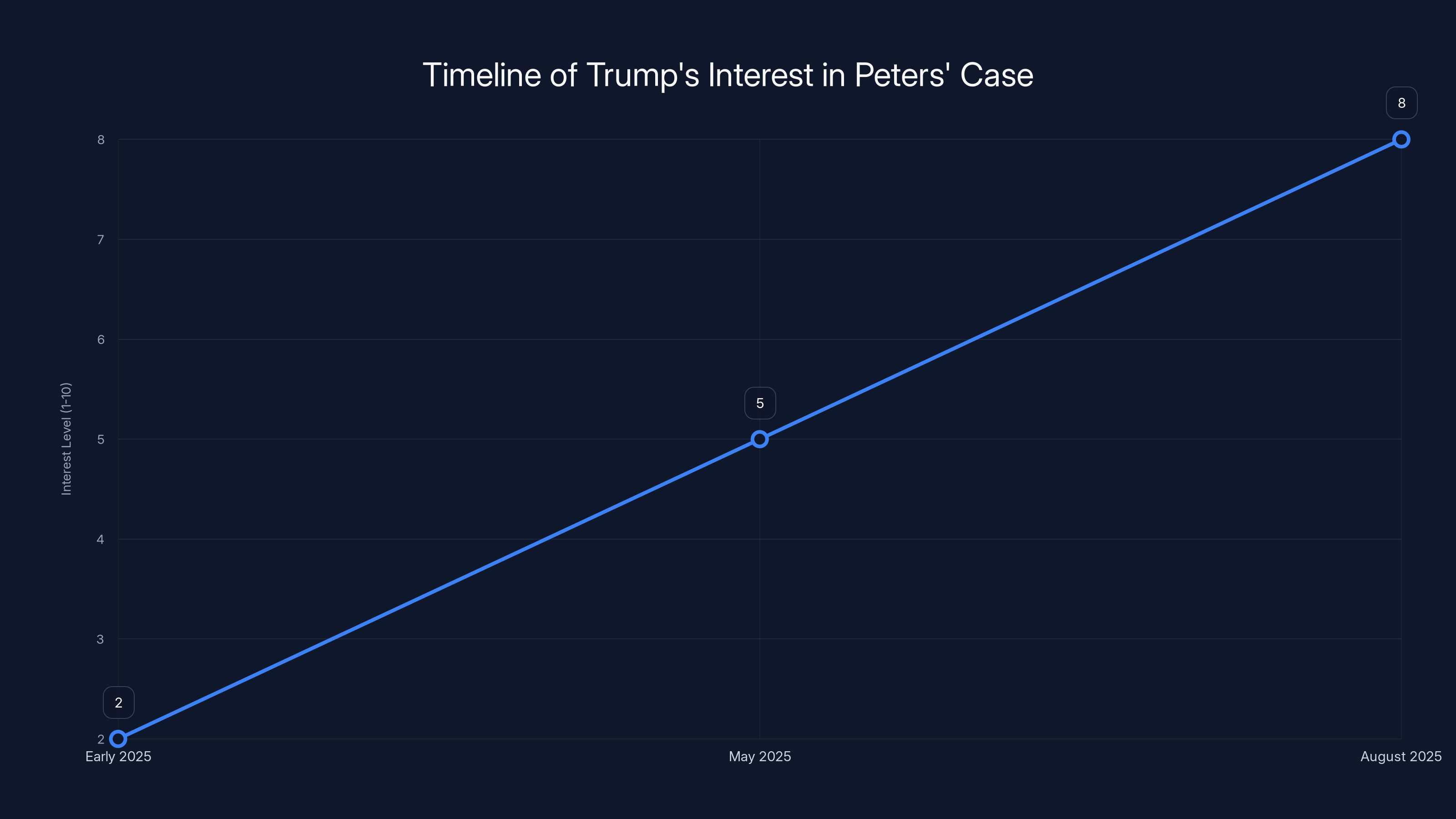

For the first couple of years after Peters' arrest, Trump appeared largely uninterested in her case. He had other battles to fight. January 6 consumed his attention. Legal cases against him mounted. Peters was a state-level issue involving a Colorado election clerk. It wasn't on his radar.

That changed in early 2025, around the time Trump's administration began staffing up after his return to office. Suddenly, the Department of Justice announced it was reviewing Peters' conviction. The timing is worth noting. This announcement came just weeks after Trump had publicly criticized Colorado Governor Jared Polis for hanging an unflattering portrait of Trump in the State Capitol. Polis had actually allowed artists to submit portraits; Trump objected to which one was selected. It was a minor political spat, the kind that happens between state and federal leaders. But Trump doesn't forget slights.

Then came the Truth Social posts. In May, Trump posted about Peters for the first time, using language borrowed from the martyr narrative: "Tina is an innocent Political Prisoner being horribly and unjustly punished." He called it "Cruel and Unusual Punishment." He blamed the "Radical Left Democrats" for what he characterized as a cover-up of alleged 2020 election crimes.

Trump's rhetoric here is important. He's not arguing that Peters' conviction was legally questionable. He's making a political argument: that she's being punished because she challenged the 2020 results, that the system is persecuting her for her beliefs. He's taking the martyr narrative and amplifying it from the highest platform available.

Then in August, Trump repeated the call for Peters' release, this time adding a threat. If Peters wasn't freed, he'd take "harsh measures" against Colorado. It's a remarkable statement: the president of the United States threatening a state unless it releases a woman convicted by state courts of breaching election systems.

What's unclear is whether Trump simply didn't understand the constitutional limitation on his pardon power, or whether he was willing to bluff and pressure a state regardless. The "pardon" he issued was legally meaningless. Peters can't accept a federal pardon for a state conviction. It doesn't work that way constitutionally. But the announcement created the appearance of action. It signaled to the election denial community that Trump was fighting on their behalf, even if the legal mechanism was illusory.

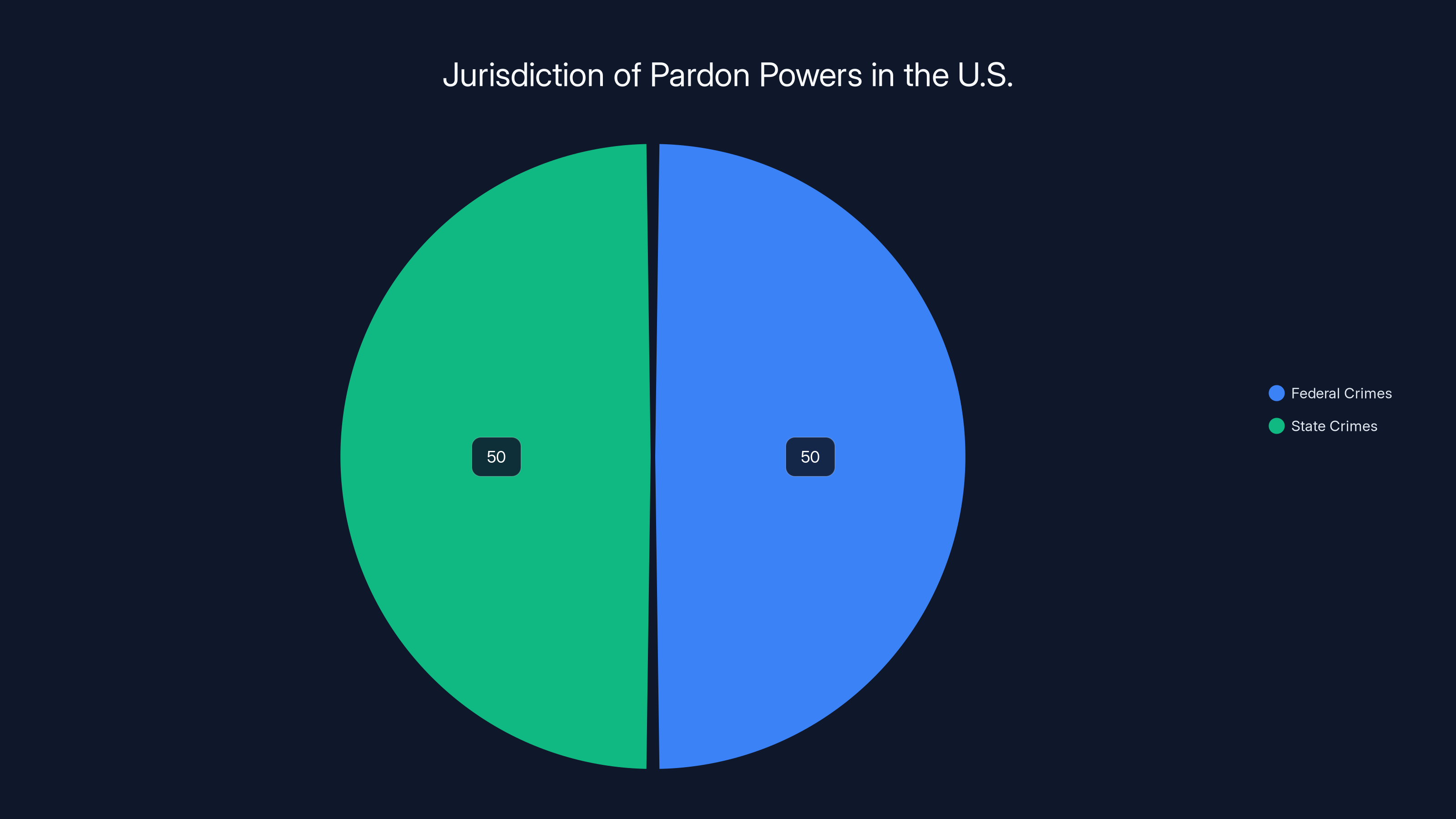

The Constitutional Puzzle: Why Trump Can't Actually Pardon Her

This is where the case becomes genuinely interesting from a constitutional perspective. The United States has two separate justice systems: federal and state. They operate independently. They have different laws, different prosecutors, different courts, different executives.

Presidents have pardon power under the Constitution, but only for federal crimes. This was established at the nation's founding and has remained consistent for over two centuries. Presidents can't pardon state crimes because they don't have jurisdiction over state courts. That authority rests with governors.

Peters was convicted in Colorado state court under Colorado state law. She committed state crimes: illegal computer access under Colorado law, election interference under Colorado law. A federal pardon is literally powerless to affect a state conviction. It's like a California governor trying to pardon someone convicted in Florida. It doesn't work. There's no legal mechanism for it to work.

Yet Trump issued a "pardon" anyway, on Truth Social, in the same format he uses for federal pardons. It's a theatrical move, one that suggests either profound misunderstanding or deliberate misleading. His supporters interpreted it as Trump taking action on Peters' behalf. Legally, it accomplished nothing.

What Trump can actually do is pressure Colorado's governor to commute Peters' sentence. That's the actual mechanism. Only Colorado can release Peters, and only through its executive clemency process. Governors have authority to commute sentences, to grant pardons, to show mercy. Polis has that power. Trump doesn't, not in any legal sense.

But Trump has other levers. He can use the presidency to apply pressure. He can threaten federal funding. He can relocate federal facilities. He can sic agencies on the state. In September 2025, Trump announced he was moving Space Command from Peterson Space Force Base in Colorado to Redstone Arsenal in Alabama. The timing is notable: this came months into his pressure campaign on Peters' case.

Was the Space Command relocation directly caused by the Peters case? Trump hasn't explicitly said so. But the sequence is telling. Pressure on Peters. Colorado doesn't yield. Federal facility gets relocated. The message is clear: disagree with Trump on this and there are consequences.

Polis' Dilemma: Why the Governor Is Reconsidering

Jared Polis is a Democrat. He's an experienced politician who knows how to navigate pressure. But the pressure campaign on the Peters case is intense and multifaceted. From the Right, figures like Bannon and Flynn are campaigning for her release. From Trump himself, there are explicit threats. From the election denial movement, there's constant amplification of the Peters-as-martyr narrative.

Polis' initial response was to hold firm. He acknowledged that he takes clemency requests seriously, but he also signaled that Peters' case didn't merit special treatment. He pointed to her lack of remorse, her continued promotion of election denial narratives, her refusal to accept the legitimacy of her conviction.

But over time, Polis began signaling that he was reconsidering. He asked his team to review Peters' clemency application "just like any other." The word "reconsidering" started appearing in reporting. Polis began sounding less certain.

Why might a Democratic governor commute the sentence of an election denier who continues promoting false claims about 2020? Several reasons might factor in. First, political exhaustion. The pressure campaign is relentless. Holding firm requires constantly defending the decision against attacks. Commuting the sentence would make the pressure stop.

Second, federal pressure. If Trump is genuinely willing to weaponize the presidency—relocating military facilities, investigating state officials, cutting federal funding—the costs of resistance accumulate. What's worth more: standing firm on principle, or avoiding further federal retaliation?

Third, public opinion within Colorado might shift. If the election denial movement succeeds in reframing Peters as a martyr, if they convince Colorado voters that she's being persecuted, political pressure on Polis could mount. Voters are a different kind of pressure than presidential threats.

Fourth, there's a genuine clemency argument to be made, even if it's not the strongest one. Peters has served roughly 14 months of a 9-year sentence. She's in a medium-security facility without serious incident. Commuting her to time served could be justified as proportional mercy, even if the underlying crimes were serious.

The danger, according to Colorado's top election official Jena Griswold, is the message commutation would send. If Peters walks free after breaching election systems and pushing election denial narratives, what's the message to others considering similar actions? What does it signal to election workers across the country who are already facing harassment and threats? These are the questions keeping officials in Colorado up at night.

Estimated timeline showing the progression of events from the initial breach in May 2021 to the subsequent dissemination of data and legal consequences.

The Election Workers' Perspective: What's at Stake

Election administration is a grinding, underpaid, often thankless job. People who work in election offices are custodians of democracy. They train poll workers, verify voter rolls, secure voting equipment, count ballots, certify results. It's technical work, administrative work, absolutely essential and utterly unglamorous.

Then came 2020 and the election denial movement. Suddenly, election workers became targets. They received threats. Their personal information was posted online. Some faced harassment at their homes. The job, which had been obscure and quiet, became dangerous.

Tina Peters and cases like hers are part of what created this environment. Peters' actions—allowing unauthorized access to election systems—fed narratives about election fraud and corruption. Even though investigations found no evidence of widespread fraud, even though judges found the claims baseless, even though Trump's own officials certified the elections, the narrative persisted. And it put election workers in the crosshairs.

Jena Griswold, Colorado's Secretary of State, has been clear about her concerns. If Peters is released after serving less than two years of a nine-year sentence, what message does that send? It signals that election deniers with political support face minimal consequences. It emboldens others to push similar narratives, to take similar actions. It demoralizes election workers who are trying to do their jobs amid harassment.

This isn't abstract concern. Election workers across the country have reported increased threats since 2020. Some have left the profession. Training new workers has become harder. The job has become less attractive. Now, with midterm elections coming in November 2026, the stakes are higher than ever. Election administrators need to know that breaching systems, even in the name of "election security," carries real consequences.

The Federal Pressure Campaign: Tools Available to Trump

Trump can't pardon Peters. But what can he do? The federal government has significant leverage over states. Federal funding, federal facilities, federal investigations, federal prosecutions of state officials—the toolkit is extensive.

The Space Command relocation is one example. It's not a trivial move. Space Command oversees critical military satellite operations. Relocating it from Colorado to Alabama eliminates federal spending, federal jobs, and federal presence in Colorado. The decision is ostensibly based on military readiness assessments, but the timing relative to the Peters pressure campaign is suspicious.

The Department of Justice review of Peters' conviction is another tool. If the DOJ finds problems with the conviction—an unlikely outcome given the trial record, but theoretically possible—it could file appeals or seek other remedies. The federal government doesn't have direct authority to overturn a state conviction, but it could make life difficult for Colorado through legal challenges or investigations.

Federal funding threats are another option. There are numerous federal grants, programs, and funding mechanisms that flow to states and localities. The administration could threaten to withhold funding if Colorado doesn't grant Peters clemency. This has been done before in other contexts, and while there are legal limits to how far this can go, it's a powerful lever.

The administration could also investigate Polis or other Colorado officials for alleged wrongdoing. True or not, an investigation would create headline noise, distract from governing, force defensive legal spending. It's a classic pressure tool.

What Trump is essentially doing is testing the boundaries of presidential power. Can a president pressure a state to release a state prisoner? How much pressure is too much? What combination of threats and inducements will work? Peters' case is the laboratory for these questions.

The Legal Question: Can Presidents Pressure States?

There are genuine constitutional questions here that legal scholars disagree on. Presidents have significant power, especially in foreign affairs and military matters. But power over criminal justice is more limited, especially when it involves state courts and state systems.

The Constitution divides power between federal and state governments. States maintain sovereignty over their own criminal justice systems. The Tenth Amendment reserves powers not delegated to the federal government to the states. Criminal justice, historically, has been a state function. Federal criminal law exists, but it's limited to specific areas: interstate commerce, federal crimes, crimes on federal property.

Can a president threaten to relocate a military base to pressure a governor on a state criminal case? This is genuinely unresolved. There's no Supreme Court precedent directly on point. The closest analogies involve the government conditioning federal funding on certain state actions, which has some limits but significant allowed scope.

The Trump administration appears to be operating under the theory that yes, the president can use all available federal tools to pressure states on whatever issues he chooses. Polis appears to be operating under the theory that no, there are limits, and the boundaries should be tested in court if necessary.

If Polis were to challenge Trump's pressure tactics in court, it would be a fascinating constitutional case. A state could argue that the president is unconstitutionally interfering with state sovereign functions. The administration could argue it's using lawful executive authority. The courts would have to draw lines about what kinds of pressure are permissible.

This hasn't happened yet. Instead, we have pressure and resistance, but not litigation. Polis is holding firm so far, though he's signaled enough flexibility that Peters' supporters believe a commutation remains possible.

Peters was convicted on seven charges, with four being felonies. This highlights the severity of her actions and the legal implications.

The Pardon Explosion: Context for Peters' Case

On Trump's first day back in office in January 2025, he issued a breathtaking wave of pardons and commutations. Nearly 1,600 people convicted or charged in connection with January 6 Capitol riot received pardons or commuted sentences. The breadth and scope were extraordinary.

Among those pardoned were Rudy Giuliani allies, proud members, militia organizers, people convicted of assaulting police officers. The message was clear: the president's supporters would face no consequences, even for serious crimes. Anyone who fought for Trump on January 6 could expect mercy.

That pardon wave accomplished something. It signaled to Trump's base that he's willing to use his power to protect allies. It traumatized democracy advocates who saw serious convictions overturned. It raised questions about the purpose and legitimacy of the criminal justice system if political loyalty can erase consequences.

The Peters case is different because it's not federal. But it's part of the same logic. Trump wants to project an image of protecting his supporters, even in cases where he lacks direct authority. With the January 6 pardons, he had authority and used it. With Peters, he lacks authority but is pressuring to get the same result.

This creates a concerning precedent: political loyalty plus federal pressure plus presidential determination can apparently override state criminal justice decisions. If that becomes the norm, it fundamentally changes the relationship between federal and state power, and between the presidency and criminal law.

Election Denial and Its Consequences: The Broader Context

Tina Peters is one person. But she's a symptom of something larger. The election denial movement didn't start with her, and it won't end with her. She's simply the person who took specific action based on false beliefs about 2020.

The 2020 election was litigated extensively. Courts rejected nearly every challenge to election integrity. Trump's own Attorney General said there was no widespread fraud. His own campaign officials certified the elections. Republican election officials across the country, including in critical states, certified the results. Election security experts found the election was secure.

Yet the election denial narrative persisted. It didn't matter that the evidence contradicted it. Peters believed it anyway. So did millions of other Americans. Belief in election fraud became a core part of Republican identity, even as evidence mounted that the claims were false.

Peters' breach of election systems was one attempt to "prove" that fraud occurred. There were others. Some people tried to access voting machines. Some tried to "audit" voting data. Some claimed to find irregularities and demanded recounts. Almost all of these efforts either found nothing substantive or were rejected by courts.

But the narrative kept spreading. Each failed attempt to prove fraud was reinterpreted as evidence of a cover-up. Each court rejection became proof of a rigged system. The movement developed immunity to contradictory evidence. It's a closed epistemic bubble where any fact that contradicts the belief is evidence of deeper conspiracy.

Peters is valuable to that movement because she apparently chose to risk her career and freedom to investigate claims she believed in. Whether she actually discovered anything is irrelevant. What matters is that she tried, that she was willing to act on her convictions. That makes her a martyr in the movement's narrative, someone worth defending.

But releasing her based on that narrative would be a victory for election denial. It would demonstrate that the movement can bend the judicial system through political pressure and the elevation of adherents to martyr status. It would show that conviction for crimes related to investigating election fraud can be overturned if you have high-level supporters.

What Colorado Election Officials Fear

Jena Griswold and other Colorado election officials have articulated clearly what they fear. A commutation for Peters would:

First, embolden election deniers to take more aggressive action. If someone who breaches election systems faces minimal consequences, the barrier to taking similar action drops significantly. More breaches, more unauthorized access, more attempts to "investigate" fraud could follow.

Second, demoralize election workers. These are people who chose a career in civil service to manage voting systems. They're already facing harassment and threats. Seeing someone imprisoned for election system breach released after minimal time would send a message that the system doesn't protect them.

Third, undermine election integrity efforts. Election officials spend significant energy on security, access control, verification procedures. These are all designed to prevent unauthorized access like Peters facilitated. If that breach carries minimal consequences, those security efforts are undermined.

Fourth, create precedent for future breaches. Other election officials considering similar actions would see Peters as a cautionary tale, but one where the caution is minimal. If she's released, the message is: try to access election systems, get caught, claim you were investigating fraud, get supported by election denial celebrities, and clemency is likely.

These fears are not abstract. They're grounded in real risks. Election security is not a partisan issue. Democrats and Republicans both benefit from secure elections, from knowing that ballots are counted accurately, from having confidence in results. Allowing political pressure to override criminal consequences for election system breaches threatens that security.

Trump's interest in Peters' case escalated significantly from early 2025 to August 2025, coinciding with political events and public statements. Estimated data.

The Clemency Process: What Options Exist

Colorado's governor has several options in response to requests for clemency. Understanding these options helps explain why Polis is in a difficult position.

First is outright pardon, which would erase the conviction entirely. Peters could petition for this, and Polis could grant it. It would mean the crime is forgiven, the conviction expunged. This would be the most generous outcome for Peters, the one that would most validate the election denial narrative. It's also the most controversial option from the perspective of election officials.

Second is commutation, reducing the sentence without erasing the conviction. Peters would remain a convicted felon, but she'd be released or her sentence would be reduced. This is what some are calling for: acknowledge that 9 years is a long sentence, reduce it to time served (roughly 14 months) or another amount, and release her. It keeps the conviction on record but shows mercy on punishment.

Third is conditional clemency, releasing Peters but with conditions. She could be released on the condition that she stops promoting election denial narratives, stops claiming the 2020 election was stolen, stops participating in election denial activities. Theoretically, this would accomplish the release while limiting the political damage. Realistically, it would be unenforceable and Peters would likely violate it publicly anyway.

Fourth is clemency based on her record in prison. If Peters had shown genuine remorse, participated in rehabilitation programs, expressed regret for her actions, there would be a legitimate clemency case based on redemption. But she hasn't. She continues to maintain innocence, continues to promote election denial narratives. She's basically unchanged from the person who breached election systems.

Polis hasn't publicly committed to any of these options. He's maintained that he's reviewing her application like he would anyone else's. But his signals suggest openness to some form of clemency. The question is which form, and what concessions he might extract.

The Threat to Election Administration: Why This Matters Beyond Peters

If Peters is released based on political pressure rather than legitimate clemency grounds, it sends a signal that election administration is a political battlefield where criminal consequences can be negotiated away.

Election administration attracts a certain type of person: detail-oriented, rule-following, civically minded individuals who want to contribute to democracy's functioning. It's not a lucrative field. It doesn't attract people seeking power or wealth. It attracts people who believe in democratic institutions.

That's changing. As election administration becomes politicized, as election officials become targets of abuse, as their decisions face constant litigation and attack, fewer people want the job. In some states and counties, finding election officials is becoming difficult. The work is being abandoned for less stressful careers.

If Peters' release signals that breaching election systems has minimal consequences, especially if the person breaching claims they're investigating fraud, it accelerates this exodus. Who wants to work in election administration if your systems can be breached and you have no support from the criminal justice system?

Conversely, if Peters remains incarcerated, it sends a message: breaching election systems is a serious crime with serious consequences, regardless of your stated motivations. That message matters. It deters future breaches. It supports election workers trying to do their jobs. It maintains the integrity of the infrastructure that counts votes.

The Constitutional Precedent: What Happens Next

We're in uncharted waters. Trump is testing how far he can push his power. Polis is resisting but signaling flexibility. The courts aren't involved, so there's no judicial check. The outcome of this case will establish precedent, whether formal or informal, for how much federal pressure can be applied to states over criminal justice.

If Polis grants clemency, it suggests that sustained federal pressure, coupled with political support from Trump's base, can overcome a governor's resistance. Future governors would learn that resisting a president is costly, that federal consequences are real, and that compromise is easier.

If Polis doesn't grant clemency, it suggests that states do retain authority over their criminal justice systems, that federal pressure has limits, that governors can stand firm without federal retaliation becoming overwhelming. But even if Polis holds, the Space Command relocation sends a message: resistance costs something.

Either way, we're establishing precedent for how presidential power relates to state criminal justice. That precedent will matter for future cases, future pressure campaigns, future attempts to override state decisions based on federal pressure.

Presidents can only pardon federal crimes, while state crimes fall under the jurisdiction of state governors. Estimated data.

What Election Deniers Are Actually Asking For

When election deniers advocate for Peters' release, what exactly are they advocating? Are they making a case for criminal justice reform? Are they saying 9 years is too long a sentence? Are they arguing the crime wasn't serious?

Or are they asking for something else: recognition that investigating election fraud should be treated differently than other crimes, that political loyalty matters, that challenging election results should be protected even if it involves breaching election systems?

The framing matters. If they're making a criminal justice reform argument, that's a different conversation than if they're asking for election-related crimes to be treated as political expression rather than actual crimes.

Based on how they discuss Peters, it seems to be the latter. She's a martyr not because 9 years is a harsh sentence, but because she challenged elections, questioned the system, threatened the election denial narrative by getting caught and prosecuted. The crime itself is secondary to the political narrative.

This is concerning because it suggests that what election deniers want is immunity for investigation-related actions based on election fraud beliefs, no matter how unfounded those beliefs are. It would mean people could breach election systems, access unauthorized data, attempt to interfere with election operations, all under the justification of investigating fraud, with confidence that they'd face minimal consequences if they had political support.

That's not a viable approach to criminal justice. It's not justice. It's impunity for political supporters, with different rules depending on ideology.

The State of Election Security Post-Peters

Two things are true simultaneously. Election systems are generally secure, especially compared to pre-2020. States have invested significantly in improvements, backups, paper ballots, audits, and security measures. The 2024 election proceeded smoothly without major security incidents.

But vulnerabilities remain. Systems are aging in some jurisdictions. Funding is inconsistent. Training is uneven. And perhaps most importantly, security through obscurity—the idea that election systems are secure because they're not well-known—has ended. Election denial narratives have made election systems a target. People are actively trying to breach them, either to "investigate" fraud or to cause actual disruption.

Tina Peters breached election systems with relatively simple credentials. The fact that she was caught and prosecuted is good. But it also shows that unauthorized access is possible, that a person with legitimate access can facilitate unauthorized access, that the systems aren't perfectly locked down.

Going forward, election security depends on multiple things: strong technical controls, trained officials, clear protocols, and one more thing: confidence that breaching systems carries serious consequences. Peters' prosecution was necessary for that deterrence. Releasing her would undermine it.

The Midterms: Why Timing Matters

The next major election is November 2026, when midterm elections will be held. That's less than two years away. Election officials are already preparing, setting up polling places, training workers, testing equipment.

If Peters is released before then, it sends a signal into that preparation process. It tells election deniers that federal pressure can overturn convictions. It tells potential Peters-followers that the risks are manageable. It tells election workers that their protection from illegal access to systems is weaker than they thought.

Alternatively, if Peters remains incarcerated, it tells everyone that breaching election systems has real, lasting consequences. That clear message matters for the next election.

Election officials are already stressed. They're managing increased security needs, facing harassment, dealing with conspiracy narratives. They don't need the additional stress of knowing that the person convicted for breaching systems might be released due to federal pressure.

The Broader Erosion of Norms: Where This Leads

The Peters case is one specific instance of a broader pattern: testing whether rules apply equally or whether political power can override consequences.

When a president pardons 1,600 supporters convicted of attacking the Capitol, what message does that send? When a president issues a meaningless "pardon" for a state prisoner as a political gesture, what does that convey? When a president relocates military installations as retaliation for not releasing a state prisoner, what precedent does that establish?

The message is: rules are conditional. Justice is conditional. Accountability is conditional on political power and proximity to the president. If you're a Trump supporter, different rules apply. If you're attacking democracy in service of the right narrative, you might face conviction, but that conviction might be overturned through political pressure.

That's not how rule of law works. Rule of law means everyone is subject to the same rules, regardless of politics. It means conviction and punishment are determined by courts applying law, not by political pressure campaigns. It means state courts maintain autonomy over state crimes.

If that erodes sufficiently, you don't have rule of law. You have rule of men, where power determines consequences rather than law.

Peters' case is one test of whether that erosion is happening. If she walks free due to federal pressure and political support, the answer is yes. If she remains incarcerated despite that pressure, the answer is no, the system is still holding.

Conclusion: When Presidential Power Meets Its Match

Tina Peters sits in a Colorado prison not because she asked questions about elections, but because she took action based on false answers to those questions. She allowed unauthorized access to election systems. She attempted to prove a narrative that investigations have repeatedly shown to be false. She was convicted by a jury, sentenced by a judge, and is now serving time.

She's also become a symbol. To her supporters, she's a martyr, someone willing to challenge a corrupt system, someone persecuted for asking the right questions. To election officials, she's a cautionary tale of what happens when you breach systems and a warning of what erosion looks like.

The Trump administration is testing whether presidential power extends to overturning state convictions through pressure. It's a question that doesn't have a clean legal answer. Technically, the president can't pardon state crimes. Practically, the president has significant leverage over states. The pressure campaign is designed to find the boundary and push past it.

Colorado's governor is at the fulcrum. He can grant clemency and signal that political pressure works. He can refuse and signal that state criminal justice remains insulated from federal pressure. He's signaled flexibility, perhaps hoping it reduces pressure. But his actual decision will matter enormously.

If Peters is released, it won't be a victory for criminal justice reform or proportional sentencing. It will be a victory for election denial, a signal that you can breach election systems, claim you're investigating fraud, get supported by powerful people, and walk free. It will demoralize election workers and undermine election security.

If she remains incarcerated, it signals that there are limits to presidential power, that state courts maintain authority over state crimes, that rule of law still has meaning. It protects the foundation that election administration stands on.

The case ultimately reveals something important about American power: it's not absolute. A president can pressure, threaten, relocate military installations, and mobilize political movements. But there are still constitutional limits, still federalism, still boundaries. Those boundaries are weaker than they used to be, more negotiable than they should be. But they still exist.

In Peters' case, they're holding. So far.

FAQ

What crime did Tina Peters actually commit?

Peters allowed Conan Hayes, someone who was not authorized, to use someone else's credentials to access Colorado election management systems. She was convicted on seven of ten charges, including four felonies: illegal computer access, attempting to affect election outcomes, computer crimes, and violations of election access laws. She didn't change votes or manipulate systems; she enabled unauthorized access to protected election infrastructure.

Why can't Trump just pardon Tina Peters?

Trump's pardon power only extends to federal crimes. Peters was convicted in Colorado state court under Colorado state law, making this a state matter entirely outside federal jurisdiction. A presidential pardon cannot overturn state convictions. Trump issued what he called a "pardon" on Truth Social, but it has no legal effect. Only Colorado's governor can grant clemency for state convictions.

What is the difference between a pardon and commutation?

A pardon forgives a crime and removes the conviction from the record entirely. Commutation reduces the sentence but keeps the conviction intact. If Colorado's governor commutes Peters' sentence, she could be released but would still be a convicted felon. If he grants a pardon, the conviction would be erased, which is what the election denial movement is actually pushing for.

Has Trump threatened Colorado in other ways besides Space Command?

Trump has indicated DOJ interest in reviewing Peters' conviction, mentioned federal funding implications, and made general threats of "harsh measures" against Colorado if Peters isn't released. The Space Command relocation is the most tangible action so far, though Trump hasn't explicitly linked it to the Peters case. The timing relative to his pressure campaign is notable.

Why would election officials care about Peters being released?

Election officials fear that releasing Peters would signal that breaching election systems carries minimal consequences, especially for someone claiming to investigate fraud. This could embolden future attempts at unauthorized access and demoralize election workers already facing harassment. It would also potentially create a precedent where election denial narratives could override criminal accountability.

What message would Peters' release send about the 2020 election?

It wouldn't change the factual record about the 2020 election, which was secure. But it would send a political message that challenging elections, even through illegal means, can result in minimal consequences if you have political support. To the election denial movement, it would be interpreted as vindication of their narrative that the system is rigged against them and that persecuting Peters is proof.

Is Colorado legally required to consider clemency for Peters?

No. Clemency is a discretionary executive power. Governors don't have to grant it to anyone. While legal tradition suggests governors should consider clemency applications and have established processes for review, actually granting clemency is entirely optional. Polis could reject Peters' application entirely, and legally, nothing could be done about it.

What would proportional sentencing for Peters' crime actually look like?

That's debatable. Some argue that unauthorized computer access should carry shorter sentences than 9 years. Others argue that attempting to affect election outcomes through breach of election systems is serious and deserves lengthy sentences. There's a legitimate debate about whether 9 years is proportional. But that debate should happen in courts based on law, not through federal pressure campaigns.

Could Peters' case set precedent for how federal and state power interact?

Yes. If sustained federal pressure forces a state to release a state prisoner, it establishes a precedent that presidents can essentially override state criminal justice through pressure and leverage. If the state successfully resists, it reinforces federalism principles. Either outcome would be legally and politically significant, especially for future cases involving political figures or crimes.

Why hasn't the courts gotten involved in this dispute?

Courts are generally reluctant to get involved in executive decisions about clemency. There's an established principle that clemency is a core executive function with minimal judicial review. Polis would have to bring a case against Trump or vice versa, and courts are unlikely to intervene in clemency decisions unless there are extraordinary circumstances like clear constitutional violations.

This article represents an analysis of public information about the Tina Peters case, the Trump administration's response, and the implications for election administration and presidential power. It's designed to explain the case's significance and the constitutional questions it raises for readers unfamiliar with the details.

Key Takeaways

- Trump cannot legally pardon Tina Peters because she was convicted in state court—only Colorado's governor can grant clemency for state crimes

- Peters breached election management systems using unauthorized credentials, enabling a former Trump official to access protected election infrastructure

- Colorado election officials fear releasing Peters would signal that breaching election systems carries minimal consequences, potentially emboldening future unauthorized access

- Trump has used federal leverage including Space Command relocation to pressure Colorado governor Polis, testing limits of presidential power over state criminal justice

- The case establishes precedent for whether sustained federal pressure can override state criminal convictions, with implications for federalism and election security

Related Articles

- Minnesota ICE Coercion Case: Federal Punishment of Sanctuary Laws [2025]

- Why Minnesota Can't Stop ICE: The Federal Authority Problem [2025]

- Why ICE Masking Remains Legal Despite Public Outcry [2025]

- ICE Judicial Warrants: Federal Judge Rules Home Raids Need Court Approval [2025]

- How DHS Keeps Failing to Unmask Anonymous ICE Critics Online [2025]

- State Attorneys General Fight Trump: The Last Constitutional Check [2025]

![The Tina Peters Paradox: Trump's Pardon Powers Don't Work Here [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/the-tina-peters-paradox-trump-s-pardon-powers-don-t-work-her/image-1-1769618390744.jpg)