Tik Tok's Epstein Files Obsession: Viral Theories, Institutional Distrust, and Digital Vigilantism [2025]

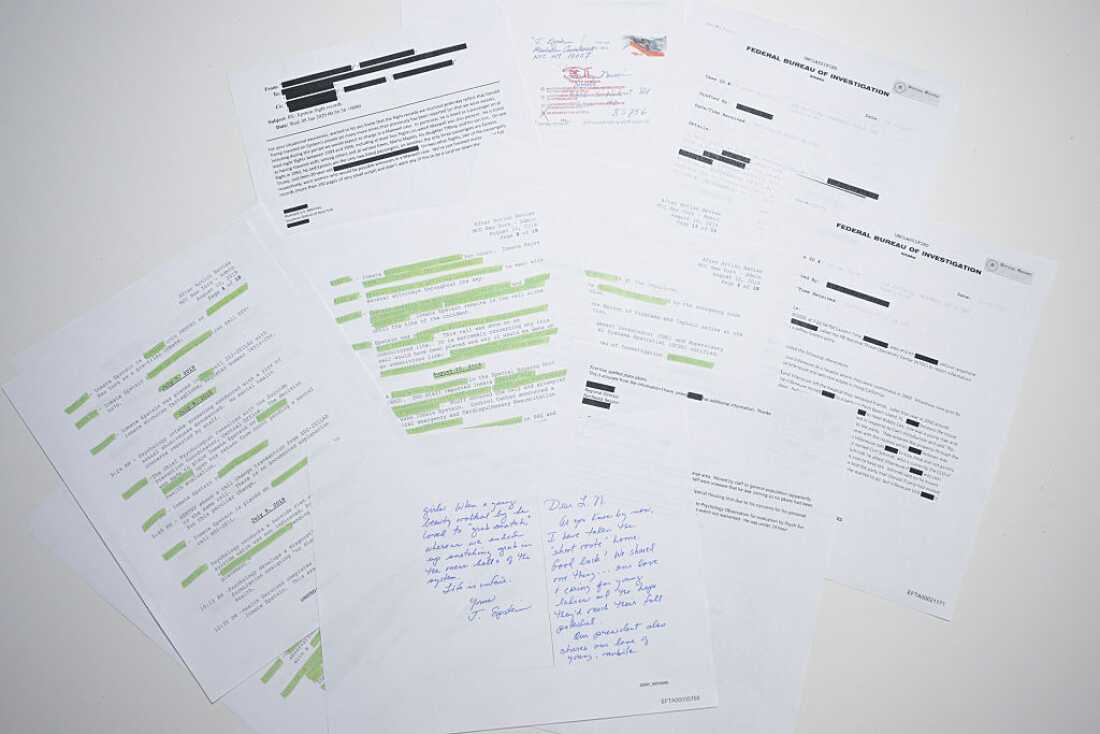

When the Department of Justice released over 3 million documents, images, and videos related to Jeffrey Epstein in January 2025, it wasn't lawyers, journalists, or law enforcement who first captured the public's imagination. It was Tik Tok creators. According to the Department of Justice, these documents were part of a massive release aimed at compliance and transparency.

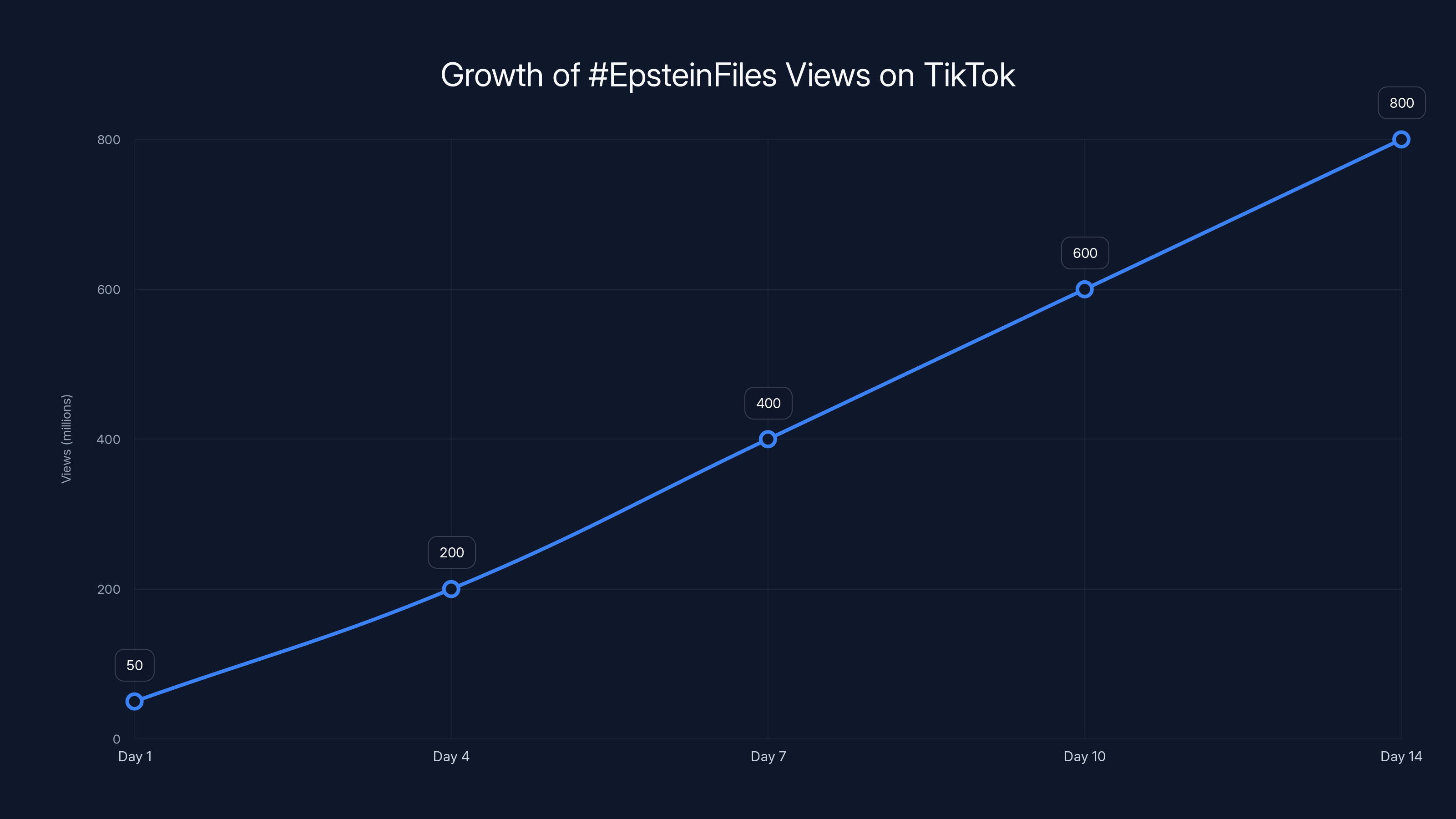

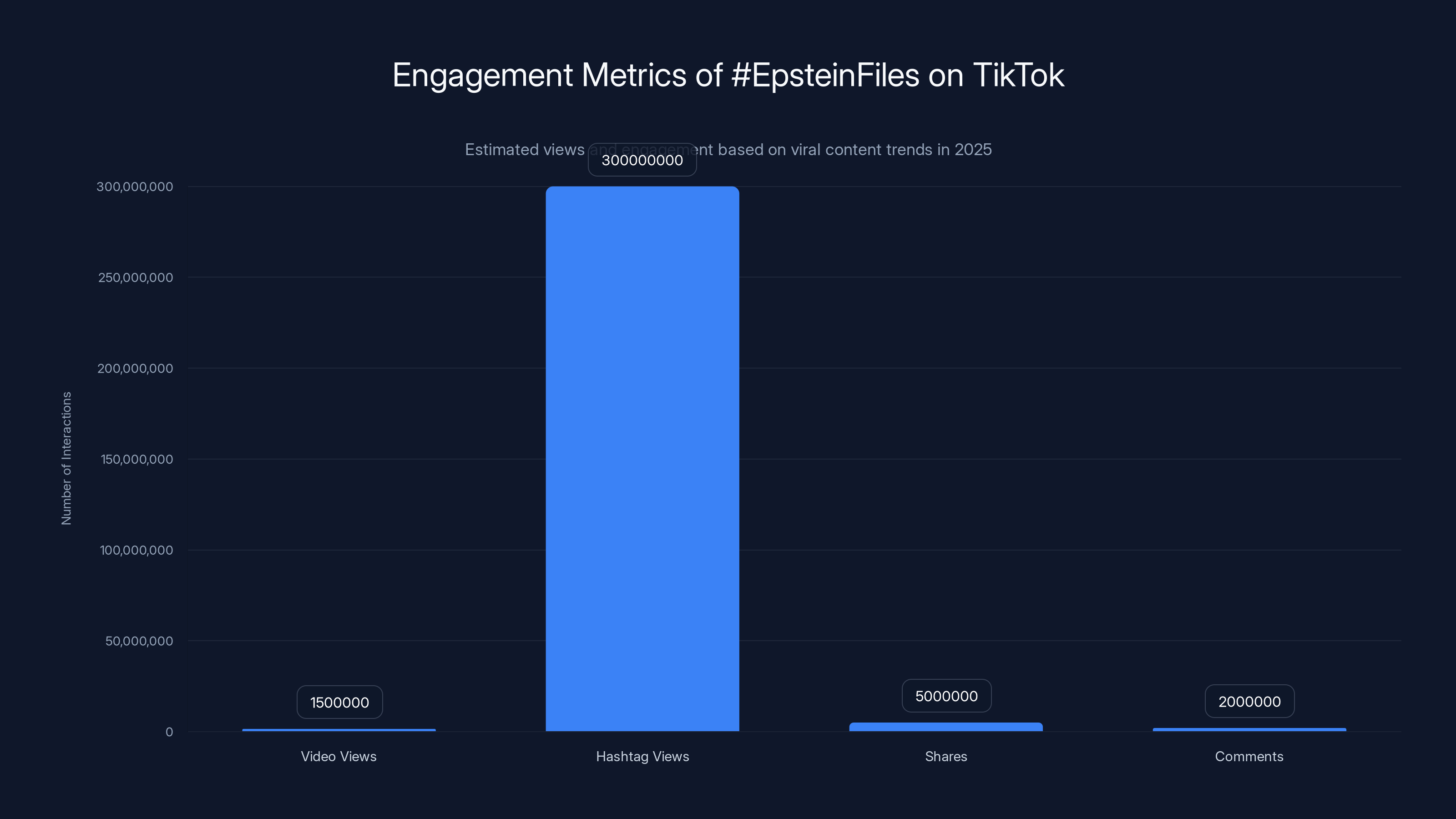

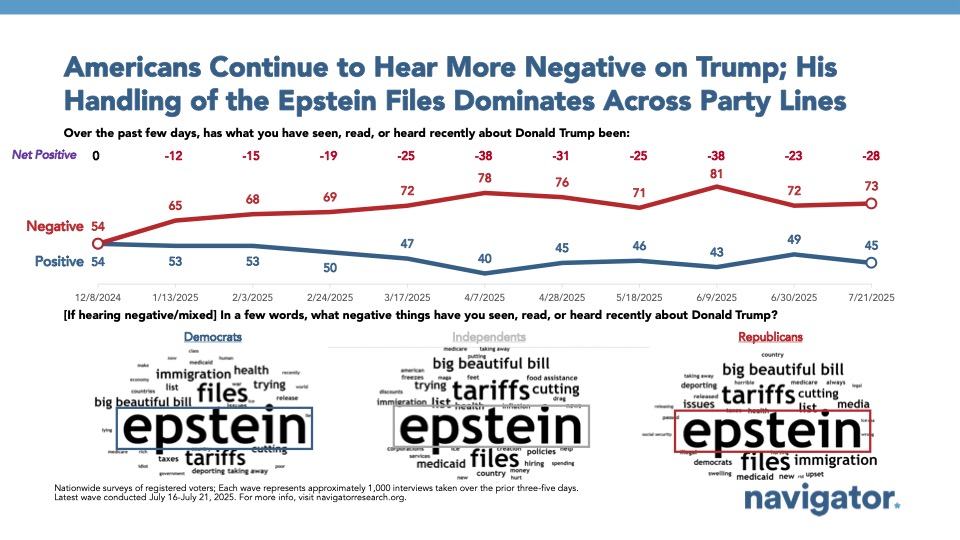

Within days, thousands of videos flooded the platform. Users compared redacted email timestamps to publicly available flight records. They cross-referenced names against news archives. They built elaborate theories connecting seemingly unrelated powerful figures through speculation, pattern-matching, and occasional wild leaps in logic. The hashtag #Epstein Files amassed hundreds of millions of views, with individual videos drawing 500,000 to 2 million views each.

This wasn't organic curiosity. It was algorithmic amplification meeting genuine public rage, mixed with the financial incentive structure of social media itself. Creators understood that Epstein content performed. It performed brilliantly. Outrage drives engagement. Conspiracy theories drive shares. The combination creates a viral cocktail that Tik Tok's algorithm practically cannot resist.

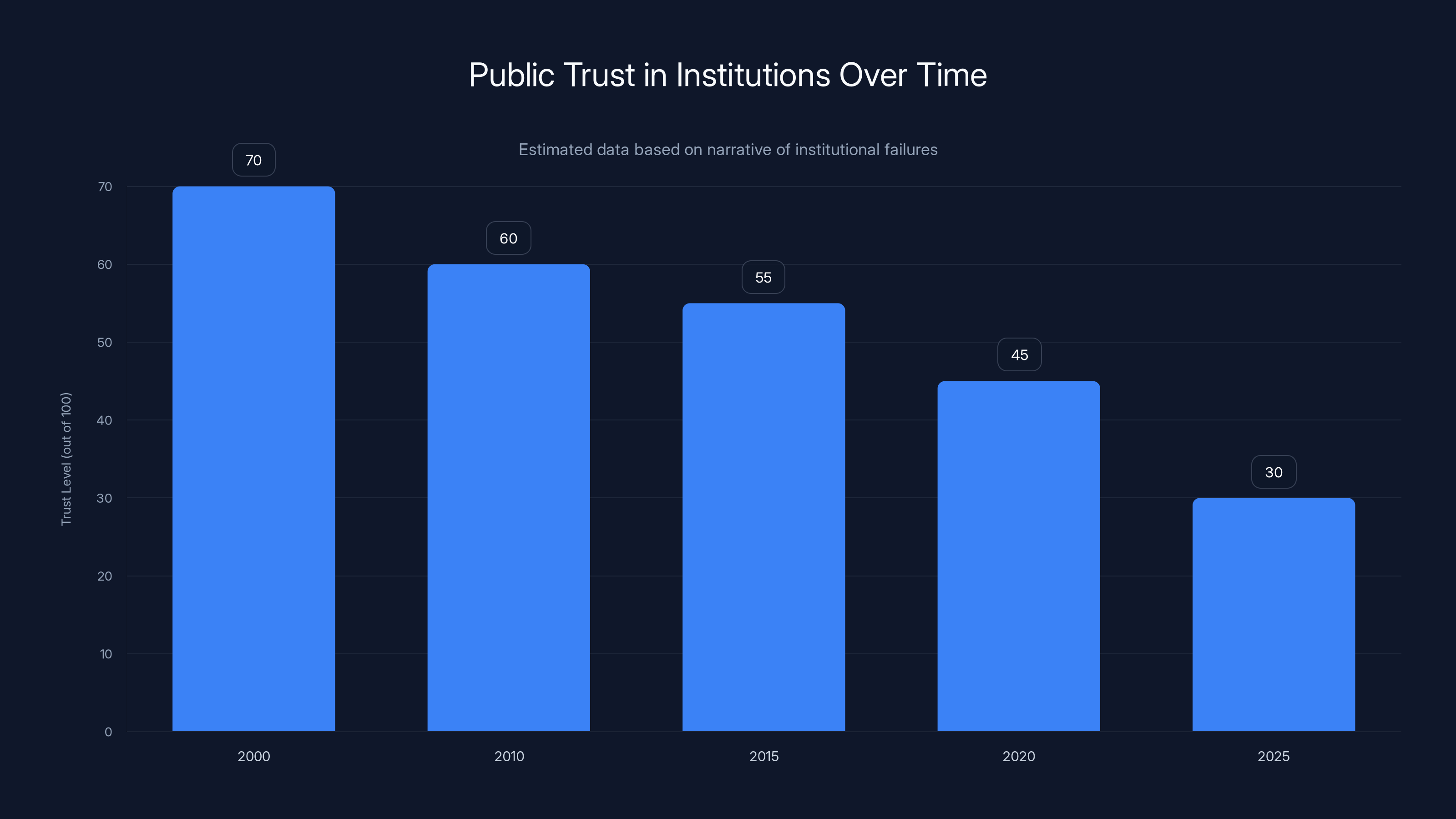

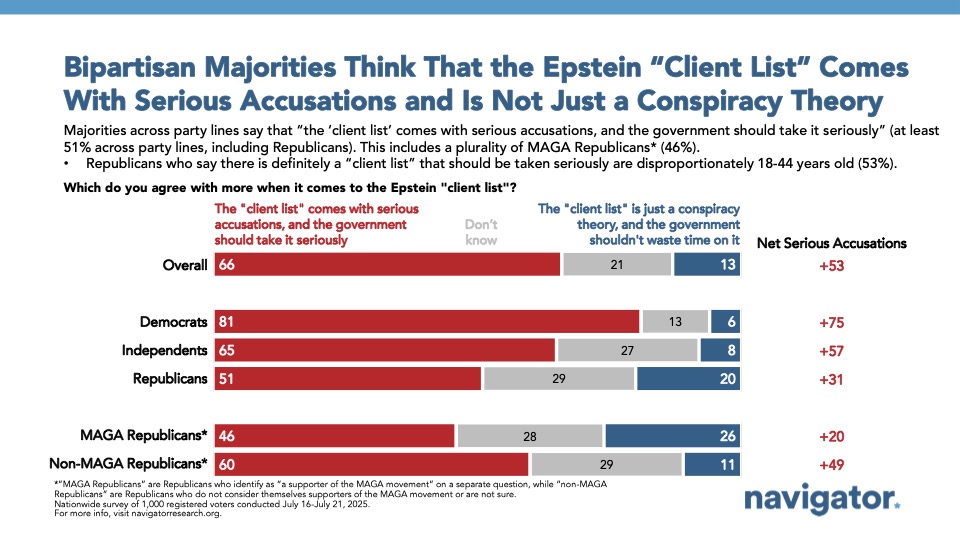

But here's the thing: beneath the spectacle lies something real. A legitimate distrust of institutions that have repeatedly failed victims. A justified anger at powerful people who apparently operated with impunity. And a growing sense that traditional channels of accountability—courts, Congress, mainstream media—move too slowly or not at all.

The Epstein files fiasco on Tik Tok reveals something darker about how digital platforms amplify both truth-seeking and misinformation simultaneously. It shows how institutional failures create vacuums that get filled by unverified theories. And it demonstrates how the economics of viral content can transform a genuine opportunity for accountability into a chaotic carnival of speculation.

Let's break down what's actually happening, why people are so invested, and what this means for the future of public discourse around high-stakes, consequential information.

TL; DR

- The Scale: Over 3 million Epstein documents triggered thousands of Tik Tok videos with hundreds of millions of combined views within weeks of release

- The Incentive: Creators earn engagement and followers by finding "connections" in redacted documents, even when evidence is paper-thin or entirely fabricated

- The Problem: Tik Tok's algorithm rewards sensationalism equally whether claims are verified or speculative, blurring lines between investigation and conspiracy

- The Reality: Some legitimate connections exist, but they're buried under mountains of baseless theories and unfounded speculation

- The Consequence: Institutional distrust combined with viral incentives creates a system optimized for engagement but fundamentally unreliable for actual accountability

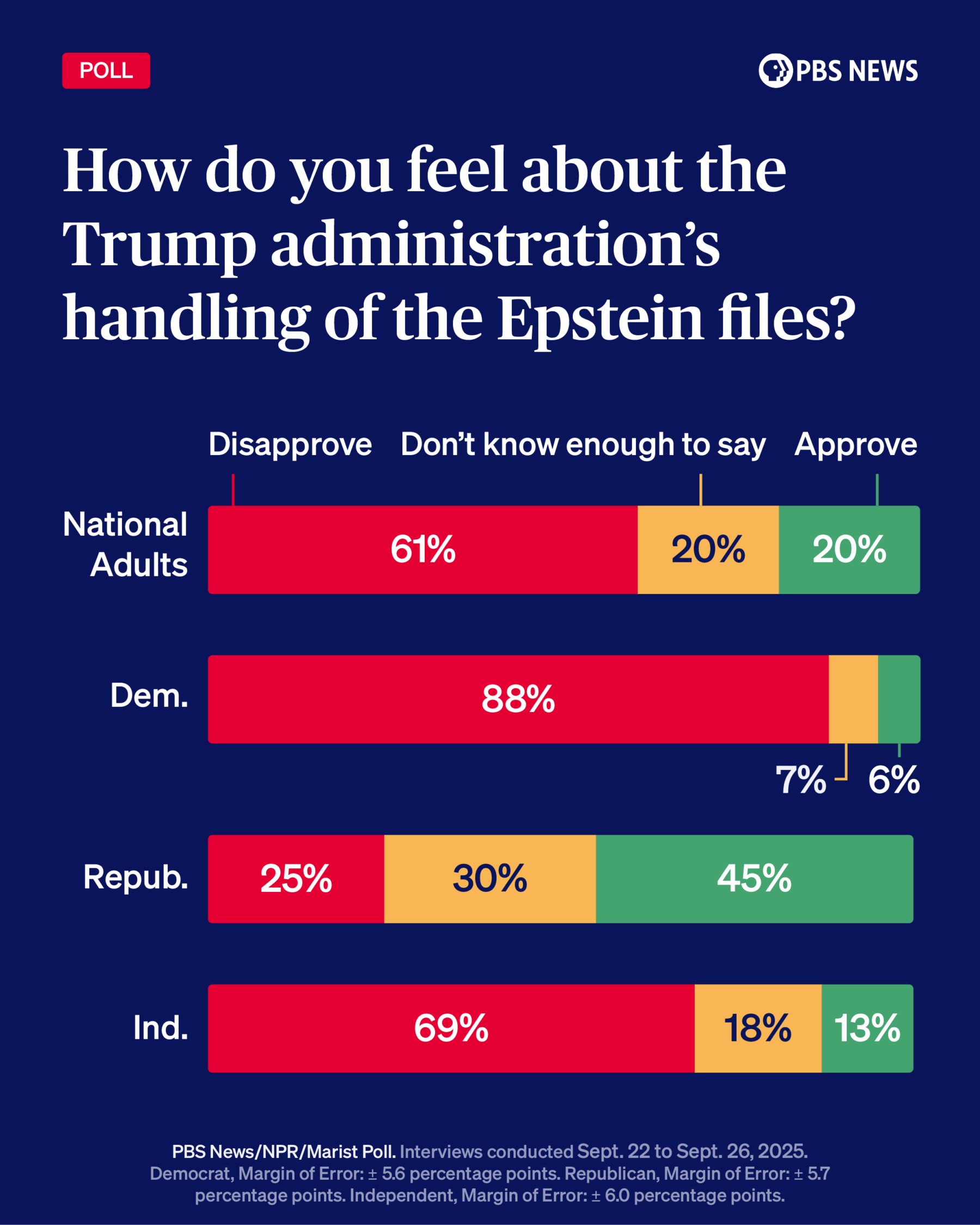

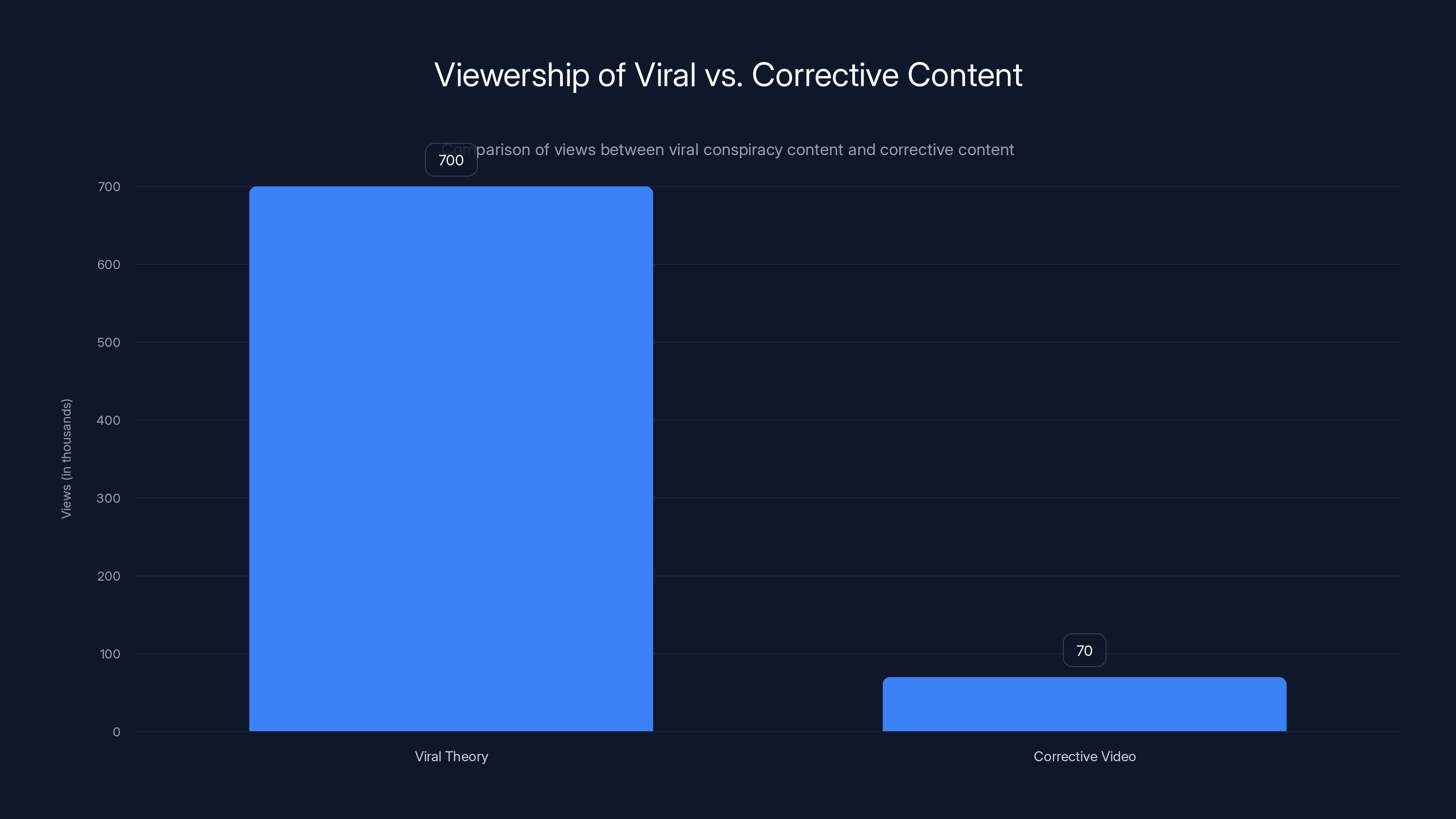

The viral theory video received 700,000 views, while the corrective video only garnered about 70,000 views, highlighting the challenge of spreading accurate information.

How the Epstein Files Became Tik Tok's Hottest Conspiracy Playground

The timing couldn't have been worse for accuracy. The Department of Justice's document release coincided with Tik Tok's absolute dominance as the platform where young people consume news, entertainment, and information. Unlike X (formerly Twitter) where context and debate happen in threads, or You Tube where long-form investigation can breathe, Tik Tok operates on 15-second to 10-minute clips. This format fundamentally constrains how complex information can be presented.

A Tik Toker can't meaningfully explain the context behind an email in 60 seconds. They can't walk through multiple interpretations of ambiguous data. They can't present counterarguments. What they can do is present a hypothesis, add some dramatic music, flash redacted documents on screen, and let their followers supply confirmation bias in the comments.

The first wave of Epstein content creators weren't conspiracy theorists in the traditional sense. Many were legitimate true-crime enthusiasts, journalists, and people interested in accountability. They genuinely believed they were crowdsourcing an investigation. Comments sections filled with users offering file numbers, highlighting specific passages, and collectively saying, "We are unredacting." There was almost a Wikipedia-meets-detective-agency vibe to it.

Then the algorithm did what it always does: it found what worked and doubled down. Videos about Epstein started getting recommended to millions of people who hadn't searched for them. The algorithm doesn't care if a theory is true. It cares if people watch, comment, share, and come back. And Epstein theories? They do all of that in spades.

Within two weeks, the #Epstein Files hashtag had accumulated over 800 million views. Individual creators who'd previously been niche true-crime accounts suddenly had 2 million new followers. Their engagement metrics skyrocketed. And here's the incentive problem: Tik Tok creators who posted careful, methodical analysis of the documents got decent traction. But creators who posted wild, sensational theories backed by circumstantial evidence? They got millions of views.

That's not a conspiracy on Tik Tok's part. That's just how engagement metrics work. The algorithm isn't designed to distinguish between "careful investigation" and "wild speculation." It's designed to maximize watch time and engagement. Speculation is just as engaging as verification. Sometimes more so.

The #EpsteinFiles hashtag rapidly gained popularity, accumulating an estimated 800 million views in just two weeks. Estimated data.

The Case Studies: What Actual Investigation Looks Like vs. What Goes Viral

To understand the problem, let's look at some specific examples. These show the difference between legitimate document analysis and the conspiracy theories that dominated the platform.

The Netanyahu Angle (Mostly Wrong, Went Massively Viral)

One of the earliest viral theories involved Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu. A Tik Tok creator found an email allegedly from Epstein that mentioned "torture" and included a timestamp that vaguely aligned with Netanyahu's public schedule. The creator then speculated that "torture" might refer to documented abuses of Palestinian detainees.

The video got close to 700,000 views. In the comments, thousands of people accepted this as evidence of some kind of connection.

Then another creator pushed back. They noted that Netanyahu had actually been in Jerusalem, not Beijing (where the email creator had placed him). They found the flight itinerary of British politician Peter Mandelson. They pointed out that Senator Lindsey Graham had visited Beijing during that period and had once used a Black Berry (the email signature mentioned Black Berry). So maybe it was Graham?

But the redacted email address belonged to none of them. It was Sultan Ahmed bin Sulayem, a Dubai-based shipping executive whose name had absolutely nothing to do with the original theory. The entire investigation was built on assumptions, circumstantial timing, and pattern-matching across unrelated datasets.

Did that matter? Millions of people had already watched the original video. The "debunking" video got maybe 10% of the viewership. The algorithm doesn't prioritize corrections over sensations.

The Redaction Detective Work (Actually Useful)

On the flip side, some creators actually did careful work. Journalists and amateur investigators cross-referenced redacted names with public databases. They matched "John D." with specific individuals by correlating the context clues in nearby unredacted emails. They found verifiable connections between Epstein and powerful figures—not through speculation, but through document analysis.

A few creators systematically reviewed the files and found several confirmed names. Jeffrey Epstein's contact with famous academics, politicians, and entertainers was documented. Some of these people had acknowledged their social connections to Epstein (which he'd aggressively cultivated). Others hadn't.

This work was real, and it was valuable. It added information. But it was also slower, less sensational, and got dramatically fewer views than the wild theories.

The Bill Gates Speculation Rabbit Hole (No Evidence, Millions of Impressions)

One of the most persistent theories involved Bill Gates. The speculation was that Gates had some unknown connection to Epstein, despite both Gates and Epstein being philanthropists and wealthy individuals who moved in overlapping circles. The "evidence" was circumstantial at best: Gates had donated to causes, Epstein knew people, therefore Gates must know things.

This theory probably started because Gates and Epstein had actually met. Epstein was involved in philanthropic circles. Gates was too. But the speculation went far beyond documented interactions. Tik Toks suggested Gates had covered up information, hidden knowledge, or been complicit in something nefarious.

There's zero verified evidence of this. But the theory got 40+ million impressions across multiple videos. And now, if you search for Gates + Epstein on Tik Tok, you get an alternate reality where this connection is treated as established fact.

The Institutional Failure That Started It All

None of this would be happening without a fundamental crisis of institutional trust. The Epstein files went viral on Tik Tok not because the platform is uniquely good at investigation, but because people had already given up on traditional institutions to deliver accountability.

The history of Epstein coverage is a catalog of institutional failure. ABC News killed an investigation by Amy Robach in 2019. The network claimed insufficient corroboration, but Robach was recorded saying the story was "quashed." Critics noted that The New York Times' initial coverage downplayed the scope of Epstein's network and the systemic enablement that allowed him to operate for decades.

Law enforcement wasn't much better. Palm Beach Police Chief Michael Reiter had investigated Epstein in the early 2000s. When journalist Julie K. Brown approached him in 2017 for her Miami Herald investigation, he was initially unresponsive. He'd been convinced that media had already squelched the story. It took Brown's persistence to get him to revisit the case.

That's the context. Mainstream media had repeatedly shown it would back away from Epstein stories. Law enforcement had shown it could be pressured or deterred. Congress had moved slowly. Justice had not been served.

So when the files were finally released in 2025, people didn't trust that traditional channels would adequately investigate them. They didn't believe that prosecutors would pursue every lead. They didn't expect the media to conduct comprehensive analysis. The reasonable conclusion, based on historical evidence, was that institutional accountability wouldn't come.

Therefore, the logic went, maybe crowdsourced investigation on Tik Tok could do what institutions couldn't. Maybe regular people, working collectively, could uncover what authorities wouldn't. It's not an irrational response to institutional failure. It's just an ineffective one.

But the incentive structure of social media is designed for this exact failure mode. When you combine genuine institutional distrust with algorithmic systems that reward sensationalism and engagement, you get thousands of videos making increasingly wild claims, all competing for views, all treated as equally valid by the platform's ranking system.

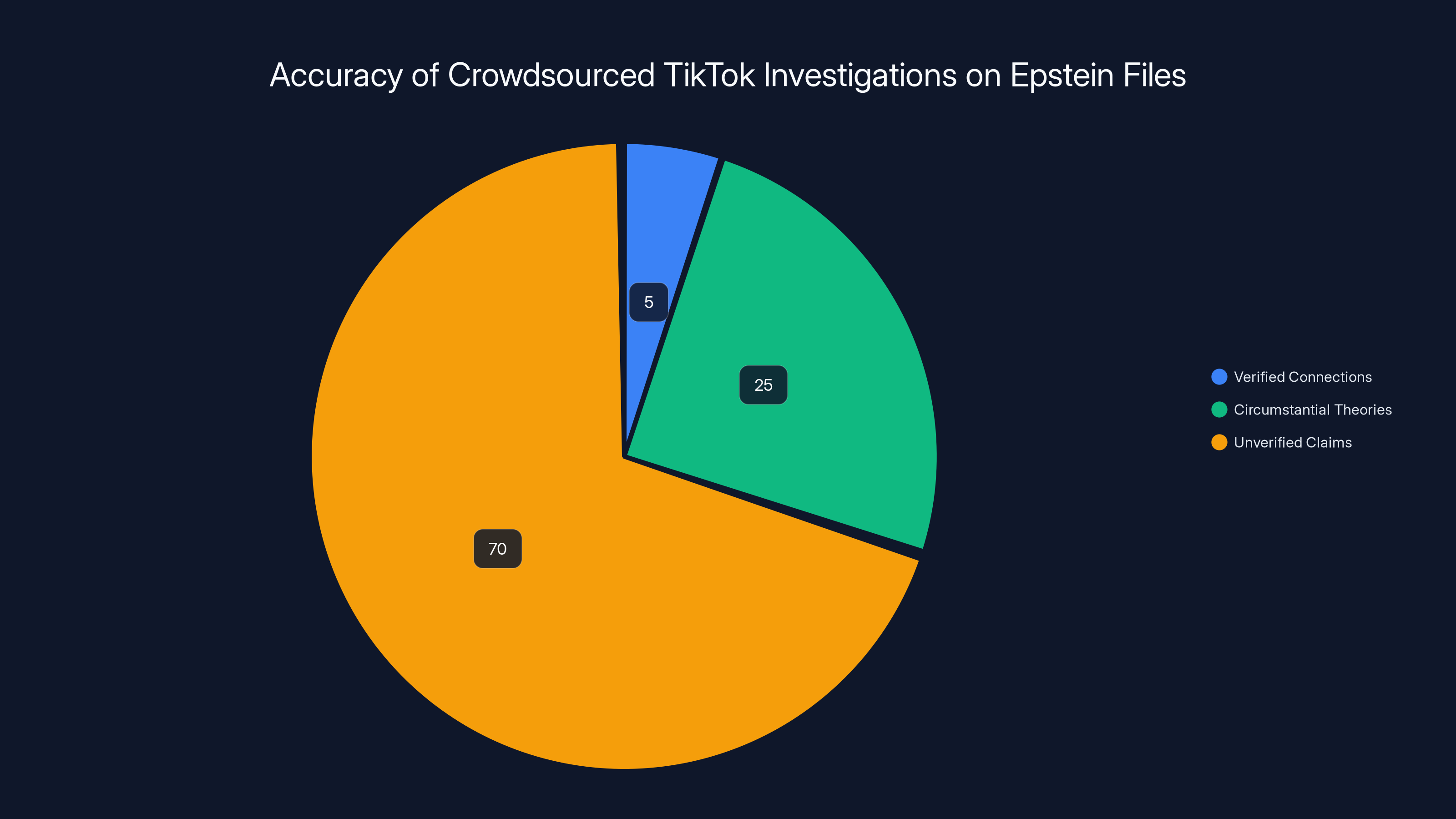

Estimated data suggests that a small portion of TikTok investigations into the Epstein files are verified, while the majority are based on unverified claims and circumstantial theories.

The Algorithm's Role: Engineering Engagement Over Accuracy

Let's be clear about something: Tik Tok's algorithm isn't sinister. It's not designed specifically to spread misinformation about Epstein. It's just doing what it's optimized for: maximizing engagement. And conspiracy theories are phenomenally engaging.

Conspiracy theories work because they're irresistible narratives. They offer:

- Pattern recognition: Your brain is wired to see patterns. A theory that strings together seemingly unrelated dots feels satisfying, even if the connections are spurious.

- Sense of agency: You're not helpless. You're part of the investigation. You matter.

- Community: Other people are searching too. You're not alone in your distrust.

- Constant novelty: There are millions of documents. There's always something new to find or reinterpret.

Tik Tok's algorithm learned that videos containing these elements got watch time. So it recommended more of them. It put them on the "For You Page" of people who'd never searched for them. It made creators who posted this content massively more successful than those who posted careful analysis.

This isn't unique to Epstein. The same dynamic played out with COVID conspiracy theories, election misinformation, and every other controversial topic that landed on Tik Tok. The platform's ranking system can't distinguish between a carefully verified claim and an unsubstantiated theory if both generate the same watch time and engagement.

What makes the Epstein case interesting is that it's harder to call this simply "misinformation." Some of what creators are doing is legitimate document review. Some is wild speculation. And the platform treats both identically.

Why People Believe Conspiracy Theories About Epstein

The psychology here matters. People aren't stupid or gullible for believing some of these theories. They're responding rationally to a history of institutional failure.

Consider what we actually know: Epstein operated for decades with apparent protection from multiple institutions. Powerful people were connected to him. Some of those connections were documented in the newly released files. The names are partially redacted, which means important information was deliberately withheld from public view.

In that context, the instinct to investigate the redactions is reasonable. The problem is that investigation without constraints, without methodology, and without peer review tends to produce conclusions that are more about what you want to believe than what the evidence actually shows.

Psychological research on conspiracy belief shows that people are more likely to accept conspiracy theories when:

- They distrust institutions: Obviously. We've covered this.

- They feel powerless: The Epstein case involves people so powerful they operated above the law for years. Investigating themselves gives people a sense of agency.

- They're part of a community: Tik Tok comment sections are communities. Finding "like-minded" people believing the same thing reinforces the belief.

- The narrative is coherent: Even if the evidence is weak, a theory that strings facts together feels more satisfying than admitting we don't know.

- Counter-evidence is available but unpersuasive: Someone proved the Netanyahu theory was wrong, but they had far fewer views. This actually increases belief in the original theory (backfire effect).

None of this makes the conspiracy theories true. But it explains why they spread so effectively. The platform's incentive structure + psychological factors + institutional distrust + millions of documents = a viral conspiracy factory.

The hashtag #EpsteinFiles garnered an estimated 300 million views, with individual videos averaging 1.5 million views, highlighting the viral nature of conspiracy content on TikTok. (Estimated data)

The Real Connections Buried in the Noise

Here's the thing that makes this mess so frustrating: there actually are real, documented connections in the Epstein files. Not the speculative ones. The actual connections that were already somewhat public or are clearly documented in the released materials.

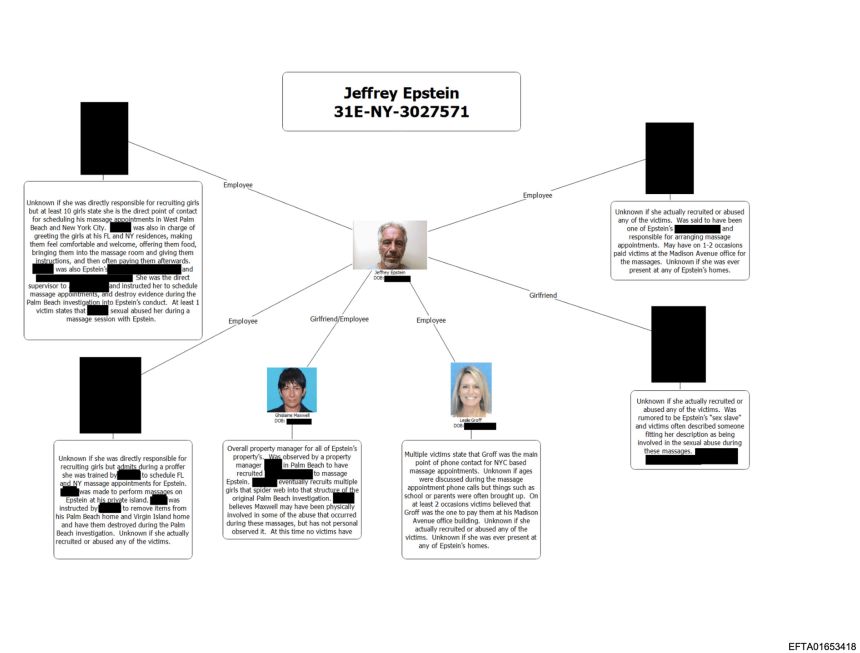

Epstein had documented relationships with legitimate powerful figures. Some of these relationships were social. Some involved business dealings. Some remain unexplained. The files reveal:

- Documentation of enablers: People who knew about Epstein's abuse and did nothing. Or worse, actively facilitated access to victims.

- A network of complicity: Not just Epstein himself, but an ecosystem of lawyers, accountants, property managers, and other professionals who made his operation possible.

- Systemic failures: Multiple institutions that knew or should have known and chose not to act.

These are the findings that actually matter for accountability. Not wild speculation about whether Bill Gates was secretly involved, but clear documentation of how a known abuser operated with apparent impunity for decades.

The problem is that these real findings are competing for attention with thousands of unsubstantiated theories. A careful analysis of Epstein's documented relationships with legal enablers gets 10,000 views. A wild theory that connects four unrelated people through circumstantial evidence gets 2 million views.

This isn't accidental. It's the logical outcome of how engagement-based recommendation algorithms work.

The Viral Mechanics: Why Engagement ≠ Truth

Let's talk about the mechanics of what makes Epstein content go viral specifically.

When you design an algorithm to maximize engagement (watch time, comments, shares, follows), you're not designing it to maximize truth. These are separate goals. Sometimes they align. Often they don't.

A Tik Tok about Epstein that says "I carefully reviewed 47 documents and found these three legitimate connections" is accurate but not particularly engaging. It doesn't trigger strong emotional responses. It doesn't make people feel like they're part of an investigation.

But a Tik Tok that says "I FOUND THE PROOF—they're hiding THIS NAME in the redactions and here's why it has to be [major public figure]" triggers everything. It's emotionally satisfying. It makes the viewer feel smart (they're getting "inside" information). It makes them feel part of something. They can comment, share, argue, find evidence to support or refute the theory.

The algorithm learns that the second type of video gets more engagement. So it shows more of the second type to more people. Creators see the metrics and learn that sensational theories outperform careful analysis. So they make more sensational theories.

This is called "algorithmic amplification of misinformation," and it's not unique to Tik Tok or Epstein. It's how engagement-based recommendation systems work across all platforms. But Tik Tok's algorithm is particularly aggressive because the entire business model is based on watch time.

The result is a platform where the most sensational, emotionally triggering content tends to surface first, regardless of accuracy. This creates a warped information environment where:

- Conspiracy theories spread faster than corrections: The original claim gets amplified. Corrections get buried.

- Volume feels like evidence: When thousands of people are making the same claim, it feels true even if they're all wrong.

- Community consensus replaces evidence: If everyone in your comment section believes something, your brain treats it as validated.

That's not how we should verify facts about high-stakes, consequential matters. But that's what Tik Tok's algorithm incentivizes.

Estimated data shows a decline in public trust in institutions over the years, highlighting the impact of repeated failures in accountability and transparency.

The Creator Economics: How Epstein Content Became a Career

We need to talk about money. Because ultimately, a lot of this behavior is driven by financial incentives.

Tik Tok creators can make money through several mechanisms:

- Creator Fund: Tik Tok pays creators based on video views and engagement

- Brand deals: Creators with large followings get paid by companies to promote products

- Affiliate links: Some creators earn commissions on products they link to

- Live gifts: Viewers can send virtual gifts during live streams, and creators get a cut

Epstein content creators aren't necessarily getting rich, but a creator with 100,000 followers posting daily Epstein analysis videos can make real income from Tik Tok's Creator Fund. More importantly, viral Epstein videos can quickly grow a creator's following, which opens up brand deal opportunities and sponsorships.

A creator might not set out to spread misinformation. They might genuinely be interested in the documents. But they quickly learn that sensational theories get more views than careful analysis. If you're monetizing views, you optimize for engagement. This doesn't require bad faith. It's just how incentives work.

Add to this the incentive of status and validation. A creator whose video goes viral gets thousands of followers, hundreds of thousands of views, and admiration from people who believe they've uncovered something important. That's intoxicating. The incentive to keep creating similar content is powerful.

This is why you see:

- Content farms: Some accounts post dozens of Epstein videos daily, each making slightly different speculative connections

- Series structures: Creators doing daily updates on "new finds," keeping their audience engaged and coming back

- Collaborative investigating: Different creators building on each other's theories, creating increasingly elaborate narratives

None of this requires deliberate conspiracy to deceive. It's just the rational response to Tik Tok's incentive structure. If you're a creator trying to build an audience, Epstein content works. So you make more of it.

How Legitimate Journalism Got Sidelined

Here's a parallel that deserves attention: while Tik Tok creators were making thousands of videos about the Epstein files, where were mainstream journalists?

The files were massive. Three million documents. But analyzing them takes time. It requires access to research databases, legal expertise, ability to contact sources for comment, and institutional backing to publish potentially defamatory claims about named individuals.

Tik Tok creators don't have these constraints. They also don't have these protections. They can post speculation with minimal liability because they're individuals operating on a platform that shields them.

Some legitimate news organizations did conduct Epstein file analysis. Investigative journalists reviewed documents, verified claims, and published findings. But these stories had to clear legal review. They had to verify sources. They had to be careful about what they claimed about named individuals. This made them slower, more cautious, and less sensational than Tik Tok videos.

The result was a massive credibility gap. Tik Tok had thousands of videos, millions of views, and a sense of real-time investigation happening. Journalists had carefully verified stories that were less sensational, published less frequently, and competing for attention against thousands of viral videos.

For many people, Tik Tok became the primary source of information about the Epstein files, even though:

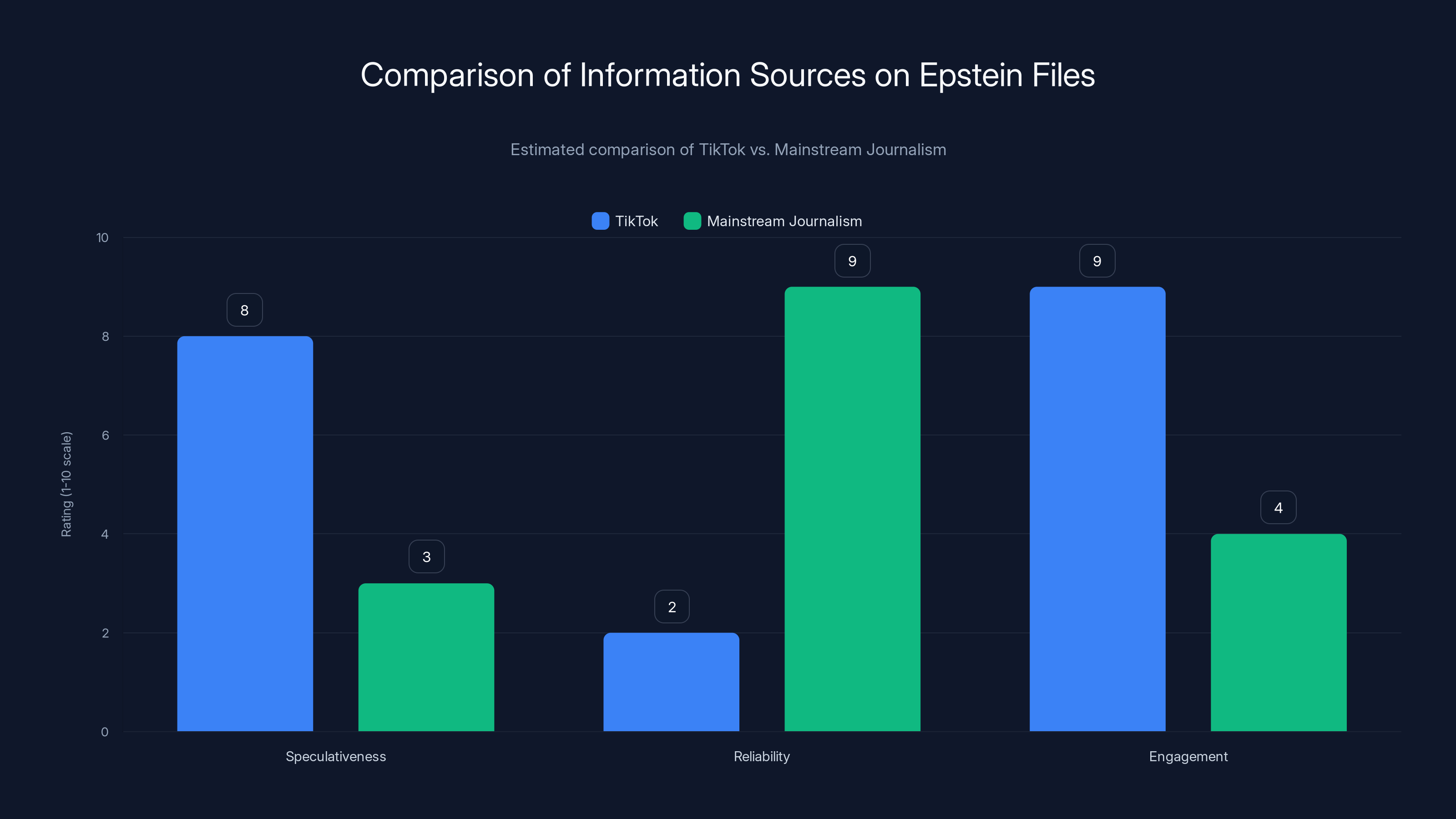

- It was more speculative: Tik Tok creators weren't constrained by editorial standards

- It was less reliable: No fact-checking, no editorial oversight, no corrections process

- It was more engaging: But engagement and accuracy aren't correlated

This isn't a new problem. It's been happening across social media for years. But the Epstein files case is particularly egregious because we're talking about high-stakes information (connections between powerful people and a documented abuser) and massive information advantage to the least reliable sources.

Estimated data shows TikTok excels in engagement but lacks reliability compared to mainstream journalism, which is more reliable but less engaging.

The Unredaction Fetish: Why People Believe They're Being Helpful

One phrase that appeared constantly in Epstein files Tik Toks was "we are unredacting." The sentiment was that by collectively analyzing the documents, the Tik Tok community could essentially recreate the redacted names. This was presented as a form of crowdsourced investigation, like a digital detective agency working toward accountability.

The logic is: if everyone tries to identify redacted names independently, eventually someone will get it right. And if millions of people have access to the documents, they'll notice patterns that institutional investigators might miss.

There's something almost noble about this impulse. But it fundamentally misunderstands how investigation works.

Legitimate investigation requires:

- Verification: Can you confirm the claim through multiple independent sources?

- Methodology: Are you using consistent standards for evidence across all claims?

- Humility: Are you open to being wrong? Can you change your mind if new evidence contradicts your theory?

- Expertise: Do you have domain knowledge that helps you understand what you're looking at?

Tik Tok's crowdsourced approach to unredaction had none of these. Instead, it had:

- Pattern matching: Finding apparent connections between unrelated data points

- Confirmation bias: Looking for evidence that supports your theory while ignoring contradictions

- Social proof: If other people believe it, it must be true

- Gamification: Making it fun and engaging to find "connections," regardless of validity

The result is that millions of people spent hours trying to identify redacted names with essentially no methodology for verification. They were applying pattern recognition to a system (the names and emails in the documents) that was specifically designed to be obscured. In that scenario, you're not doing investigation. You're playing detective in a game where wrong answers feel just as satisfying as right ones.

The Collateral Damage: Innocent People Caught in the Conspiracy Net

One of the most troubling aspects of the Epstein files Tik Tok phenomenon is how innocent people got caught up in the theories.

When millions of people are trying to identify redacted names, confirmation bias kicks in hard. Someone will suggest a name. Others will find circumstantial evidence that seems to support it (they were in the same city, they attended the same event, they know someone else in the documents). The video gets shared. The theory gets repeated across platforms.

Now, an innocent person has been publicly accused of involvement with Epstein, based on nothing more than circumstantial pattern-matching.

This isn't theoretical. It happened repeatedly. People who had absolutely nothing to do with Epstein found themselves featured in conspiracy videos. Their reputations were damaged by unfounded theories. The damage was often permanent—you can't un-hear thousands of people saying "I bet it's you" on the internet.

This is a real cost of unmoderated, crowdsourced conspiracy investigation. The people doing the investigating mean well (mostly). They're not trying to harm innocent people. But they're operating in a system that:

- Rewards sensational claims more than verified ones

- Makes it easy to spread accusations and hard to spread corrections

- Has no accountability for false claims

- Provides no recourse for people falsely accused

If I post on Tik Tok saying "I think Redacted Name X is actually [Innocent Person's Real Name]," and that gets 2 million views, there's no mechanism for me to correct it if I'm wrong. The innocent person has no recourse. They can't sue Tik Tok (Section 230 immunity). They can probably sue me, but finding and suing random people is expensive and impractical.

Meanwhile, the damage to their reputation is done and permanent.

Congress Reviewing the Files: Why Institutional Accountability Matters

While Tik Tok creators were generating millions of videos, Congress was also reviewing the Epstein files. This is worth paying attention to, because it's the institutional channel that actually matters for accountability.

Unlike Tik Tok creators, Congress has:

- Subpoena power: They can compel testimony and documents

- Legal authority: They can pursue charges if crimes are uncovered

- Expertise: They have investigative staff with relevant backgrounds

- Accountability: Their findings are public record and subject to scrutiny

This isn't to say Congress is infallible. It moves slowly. It's subject to political pressure. But it has actual power to create consequences, unlike Tik Tok creators.

The problem is that institutional investigation is slow and undramatic. Congress's reviews don't get shared millions of times on social media. They don't create the sense of real-time discovery that Tik Tok videos do. So while Congress is actually doing the work that could lead to accountability, Tik Tok is where the public attention is.

This creates a strange dynamic where the most sensational, least reliable source of information (Tik Tok) dominates public perception, while the most powerful, most reliable source (Congress) operates out of the spotlight.

The real question is whether the Tik Tok spectacle will pressure Congress to move faster and be more transparent. Or whether it will backfire by making actual investigation seem less urgent ("people are already investigating on Tik Tok") while making sensationalism seem more credible.

The Precedent Problem: What This Means for Future Document Releases

Let's think about what the Epstein files Tik Tok phenomenon means for the future. Because the government will likely release large document collections again. Maybe on Ukraine, classified operations, other high-stakes matters.

Now that we've seen what happens when millions of people with no verification methodology access complex documents, we know:

- The documents will get swarmed by creators optimizing for engagement

- Conspiracy theories will spread faster than verified analysis

- Innocent people may be falsely accused

- The signal-to-noise ratio will be terrible

- The actual valuable information will be buried under speculation

Governments could respond by being more restrictive about document releases. Or they could require better verification procedures before releasing massive dumps. Or they could fund institutional journalism and research to manage the information professionally.

What they probably shouldn't do is nothing. Because what we learned from Epstein is that massive document releases in the Tik Tok era require thinking about information flow, not just freedom of information.

Freedom of information is essential. But information without context, without verification, without methodology is just noise. And noise, distributed at scale through algorithmic systems, is indistinguishable from misinformation.

The Role of Distrust: Why People Don't Trust Institutions to Do This

We keep coming back to institutional distrust, because it's the root cause. People don't believe the FBI will adequately investigate. They don't believe Congress will take action. They don't believe the media will report comprehensively. So they take investigation into their own hands.

Sometimes that's the right instinct. If institutions are failing, sometimes you need to apply pressure from outside. Crowdsourcing can surface information that institutions miss.

But the Epstein files case shows the limits of crowdsourcing without methodology. It's good at generating engagement. It's terrible at generating truth.

What would actually help is more institutional resources dedicated to investigation. More journalists with time to spend on complex cases. More funding for legal investigation. More transparency from Congress about what they're finding.

Instead, what we got was a Tik Tok wildfire where engagement metrics replaced investigation standards.

The Misinformation Architecture: How Platforms Enable This

This isn't Tik Tok's fault specifically, though Tik Tok's algorithm is particularly aggressive about amplifying engagement. This is how all engagement-based platforms work. Facebook, X, Instagram, You Tube—they all face similar dynamics.

The problem is fundamental to the business model. Platforms make money from advertising, which is sold based on user attention. The more time users spend, the more ads they see, the more the platform can charge advertisers. So the algorithm optimizes for engagement.

Engagement is not a proxy for truth. It's correlated with emotional intensity—anger, surprise, validation, fear. Conspiracy theories hit all of these. So they get amplified.

This isn't what platforms set out to do. You Tube didn't design its algorithm to spread misinformation. But it designed it to maximize watch time. Misinformation is just very good at maximizing watch time.

The Epstein situation is interesting because it's where engagement-based amplification meets legitimate public interest. There's a real story here—Epstein abuse, institutional failures, questions about powerful people's connections. That legitimacy combined with algorithmic amplification creates a perfect storm.

The Path Forward: What Could Actually Work

So where does this go from here? How do we get accountability for what the Epstein files reveal without surrendering to conspiracy theories?

Better institutional capacity: Government could fund more investigators, more prosecutors, more forensic accountants to work through the documents with actual methodology. This is boring and slow but actually produces results.

Transparency about the investigation: Congress could publish regular updates on what they've found, what they're investigating, what they've ruled out. This would compete with Tik Tok speculation by providing an authoritative source.

Media investment: News organizations could assign teams to analyze the documents comprehensively. This requires money that many organizations don't have, but it's the alternative to crowdsourced chaos.

Platform changes: Tik Tok could de-amplify speculative content about ongoing investigations. Reduce the reach of claims about redacted names. Amplify verifiable findings from institutional investigators instead. This would require the platform to make moral choices that conflict with engagement optimization.

Media literacy: People could be taught to distinguish between crowdsourced speculation and verified investigation. This is hard because the distinction isn't obvious when both are on Tik Tok.

None of these are easy. They all require investment, institutional courage, and willingness to prioritize accountability over engagement.

But the alternative is what we got: millions of videos, millions of views, and essentially no progress toward actual consequences for anyone.

Conclusion: The Epstein Files Moment as a Test for Democracy

The Epstein files release and the subsequent Tik Tok explosion represent a moment of reckoning for how we handle information in the digital age.

On one hand, you have legitimate public interest, justified institutional distrust, and real questions that deserve investigation. On the other hand, you have algorithmic systems that amplify engagement over accuracy, incentives that reward sensationalism, and a format that makes careful analysis nearly impossible.

What happened wasn't unique to Epstein. We're going to see this pattern again: major document release → Tik Tok creators swarm → speculation spreads faster than verification → innocent people falsely accused → actual findings buried → institutional accountability stalled.

We need to figure out how to handle this before it becomes the default way we handle high-stakes information. Because right now, our system is optimized for engagement, not accountability. And in the Epstein case, those are directly opposed.

Some facts that matter: Epstein abused many people. Institutions failed those people. Questions about powerful people's connections are legitimate. But speculation isn't investigation. Engagement isn't truth. And a million people confidently wrong is still a million people wrong.

The Epstein files should lead to accountability. Whether it does depends on whether institutions step up or whether we accept Tik Tok as our primary source of truth on matters this consequential.

Given what we've seen, the outcome remains unclear.

FAQ

What exactly are the Epstein files?

The Epstein files refer to over 3 million documents, images, and videos released by the Department of Justice in January 2025, obtained from investigations into sex trafficking allegations against Jeffrey Epstein. They include emails, financial records, photographs, and other materials that detail Epstein's operation and his connections to various individuals. Despite heavy redactions protecting some names and personal information, the documents provide unprecedented insight into how Epstein operated and who may have been aware of or facilitated his activities.

Why did Tik Tok creators become so obsessed with analyzing these documents?

Tik Tok creators are drawn to the Epstein files for several converging reasons: the platform's algorithm rewards engagement regardless of accuracy, there's genuine public interest in accountability, the redacted documents create mystery that invites speculation, and creators can build large audiences and earn income from viral content about the topic. The combination of legitimate institutional distrust, the format of the documents (which creates investigative opportunity), and Tik Tok's incentive structure created a perfect storm for viral analysis videos.

How accurate is the crowdsourced investigation happening on Tik Tok?

Very little of the crowdsourced Tik Tok investigation has proven accurate. While some legitimate connections have been found through careful document analysis, the vast majority of viral theories are based on circumstantial pattern-matching, speculation, and confirmation bias rather than verified evidence. The platform's algorithm treats sensational theories identically to careful analysis in terms of distribution, so unverified claims spread just as quickly as verified ones. Professional investigators and journalists have verified that many widely-shared theories are entirely unfounded.

Can innocent people be harmed by false accusations on Tik Tok?

Absolutely. Multiple innocent people have been falsely identified as involved with Epstein based on coincidental connections or similarity to redacted initials in emails. These false accusations can damage reputations permanently since corrections rarely achieve the reach of original accusations. Tik Tok's Section 230 immunity means the platform can't be sued for false accusations posted by users, and creators typically face minimal consequences for spreading unverified theories about named individuals.

What does institutional distrust have to do with this phenomenon?

Institutional distrust is fundamental to why Tik Tok became the primary investigative channel. Historically, mainstream media has downplayed Epstein coverage (ABC News killed an investigation; the Times' initial coverage was less comprehensive than critics wanted), and law enforcement moved slowly or faced pressure to back away from cases. This justified skepticism about whether institutions would thoroughly investigate the files led people to crowdsource investigation themselves rather than wait for official channels to act.

Has the institutional investigation revealed anything important?

Congress is reviewing the files and has found documented connections between Epstein and various powerful figures, evidence of institutional enablers who knew about or facilitated his activities, and potential legal violations that may lead to charges or accountability. However, these institutional findings receive far less public attention than viral Tik Tok speculation, meaning the most reliable investigative work is competing for attention against the least reliable.

What should happen next with the Epstein files?

More institutional resources should be dedicated to investigation (additional prosecutors, investigators, and analysts), Congress should regularly publish transparent updates on what they've found, news organizations should assign teams to comprehensively analyze the documents, and Tik Tok should reduce algorithmic amplification of speculative content about redacted names. However, these changes would require abandoning engagement optimization as the primary metric, which no platform has voluntarily done.

Could this happen with future government document releases?

Yes. The Epstein files precedent suggests that any major document release in the Tik Tok era will likely follow a similar pattern: rapid creator swarming, algorithmic amplification of sensational theories, spread of false accusations, and institutional investigation happening in the background. Unless governments change how they release documents or platforms change their algorithms, expect this dynamic to repeat with other high-stakes information releases.

Use Case: Transform your research process with AI-powered document analysis and investigation tools that help you verify claims and organize findings efficiently.

Try Runable For Free

Key Takeaways

- Over 3 million Epstein files triggered thousands of TikTok videos with hundreds of millions of combined views within weeks, overwhelming institutional investigation efforts

- TikTok's algorithm amplifies sensational conspiracy theories equally with verified analysis because engagement (not accuracy) drives content distribution

- Institutional distrust stemming from historical media suppression and law enforcement delays motivated people to crowdsource investigation through TikTok rather than wait for official accountability

- While some legitimate document analysis occurred, the vast majority of viral Epstein content involved unverified pattern-matching and false accusations against innocent people

- Creator monetization incentives directly reward sensational theories over careful analysis, creating systematic pressure to produce engaging conspiracy content

Related Articles

- The Jeffrey Epstein Fortnite Account Conspiracy, Debunked [2025]

- Meta's Fight Against Social Media Addiction Claims in Court [2025]

- Government Censorship of ICE Critics: How Tech Platforms Enable Suppression [2025]

- Social Media Safety Ratings System: Meta, TikTok, Snap Guide [2025]

- Meta's Child Safety Crisis: What the New Mexico Trial Reveals [2025]

- Meta's Child Safety Trial: What the New Mexico Case Means [2025]

![TikTok's Epstein Files Obsession: Viral Theories, Institutional Distrust, and Digital Vigilantism [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/tiktok-s-epstein-files-obsession-viral-theories-institutiona/image-1-1771002807249.jpg)