The Verdict That Changes Everything for Rideshare Safety

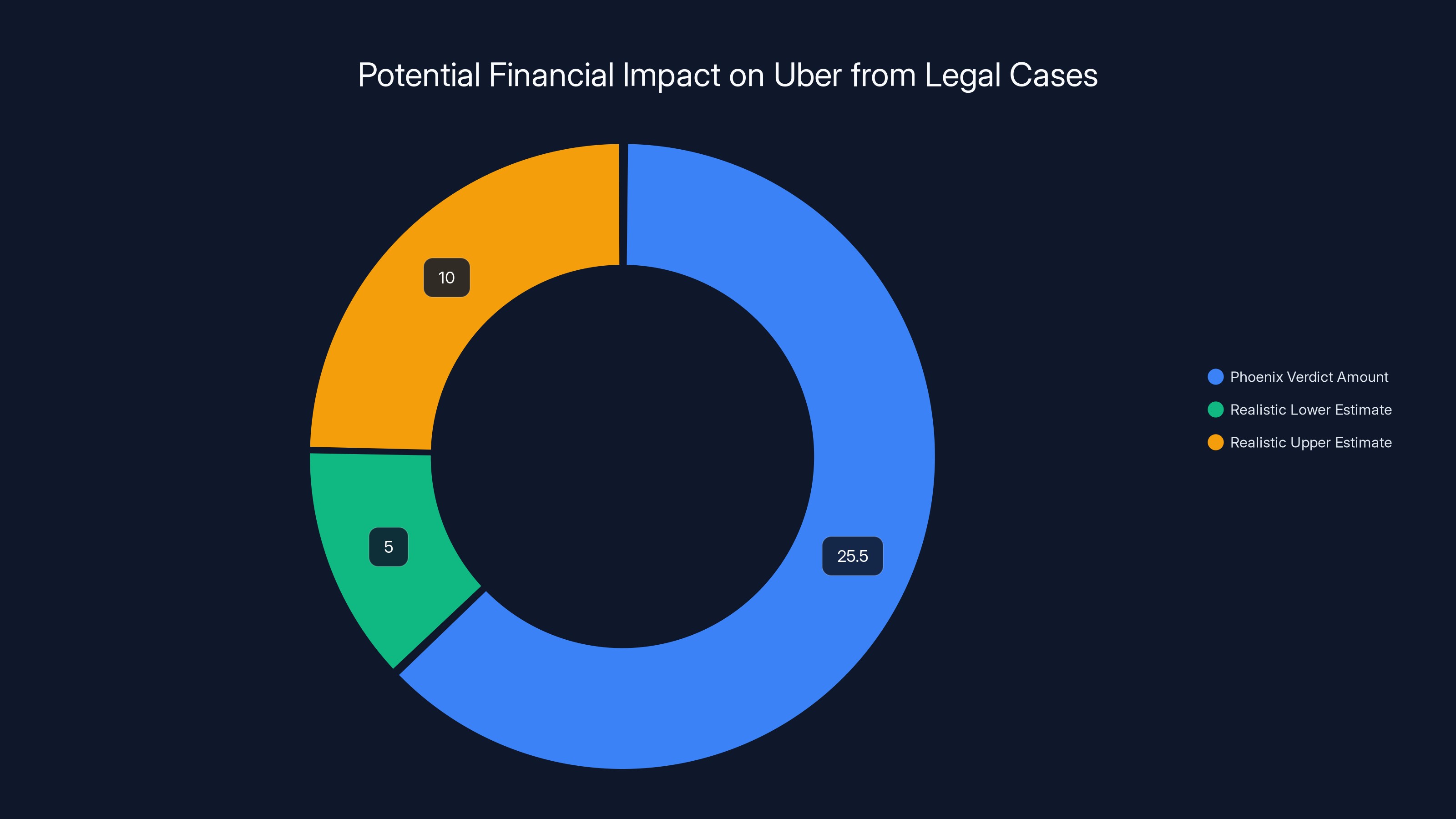

A federal jury in Phoenix just handed down a decision that sends shockwaves through the rideshare industry. They found Uber liable for the sexual assault of a passenger named Jaylynn Dean, who was raped by her driver in November 2023. The company was ordered to pay $8.5 million in damages. That's not just money—it's a legal precedent that could reshape how courts hold platforms responsible for driver conduct.

Here's why this matters so much: Uber has spent years arguing it can't be held liable for what drivers do on its platform. It's treated driver conduct like a third-party problem, not Uber's responsibility. This verdict contradicts that entire defense strategy.

The case was overseen by US District Judge Charles Breyer in Phoenix, who's also managing over 3,000 similar consolidated federal lawsuits against Uber. These cases all involve similar allegations: passengers assaulted by drivers, Uber claiming it's not responsible, and victims seeking justice.

Jaylynn Dean's case is the first to go to trial. It's what's called a "bellwether case"—the first one that sets the tone for all the others. Legal experts watch these cases carefully because judges often use the outcomes to decide how to handle similar ones.

Uber responded immediately, saying they'd appeal. Their spokesperson claimed the verdict "affirms that Uber acted responsibly," which is a pretty bold statement when a jury just found the opposite. But Uber has deep pockets and excellent lawyers. Appeals are coming.

The real question isn't whether Uber will fight this. They will. The question is whether this verdict survives appeal, and if so, what happens to those 3,000 other cases waiting in the wings.

Understanding the Legal Liability Question

For years, Uber and similar platforms have hidden behind what's called "platform immunity." The argument goes like this: we're just a technology platform connecting drivers and passengers. We're not employers. We're not dispatchers. We're not responsible for independent contractors' criminal acts.

Courts have been skeptical of this argument for a while, but it's held up more often than not. Uber has successfully used it to dodge liability in numerous cases. The company invests heavily in this legal position because if it fails, the financial exposure becomes enormous.

Jaylynn Dean's lawyers argued something different. They said Uber wasn't just passively hosting a marketplace—they actively selected drivers, set terms, controlled ratings, and profited from every ride. With that level of control comes responsibility for safety. Uber chose not to implement stronger safety measures, background checks, and accountability mechanisms when they had the power to do so.

The jury agreed. They found Uber negligent in rider safety. This is the pivotal distinction. The verdict doesn't say Uber committed sexual assault. It says Uber was negligent in preventing it.

What makes this significant is the standard applied. The jury essentially said: you had the power to prevent this harm, you knew these risks existed, and you failed to take adequate precautions. That's negligence in legal terms.

Uber's appeal will likely focus on whether a jury verdict can really change the company's liability status. Their lawyers will argue that federal law protects platforms from liability for user-generated content and user actions. This is getting into complex telecommunications law territory.

But here's the catch: Uber isn't just a neutral platform anymore. They control driver approval, set pricing, monitor behavior, and enforce standards. That control might actually undermine their immunity arguments.

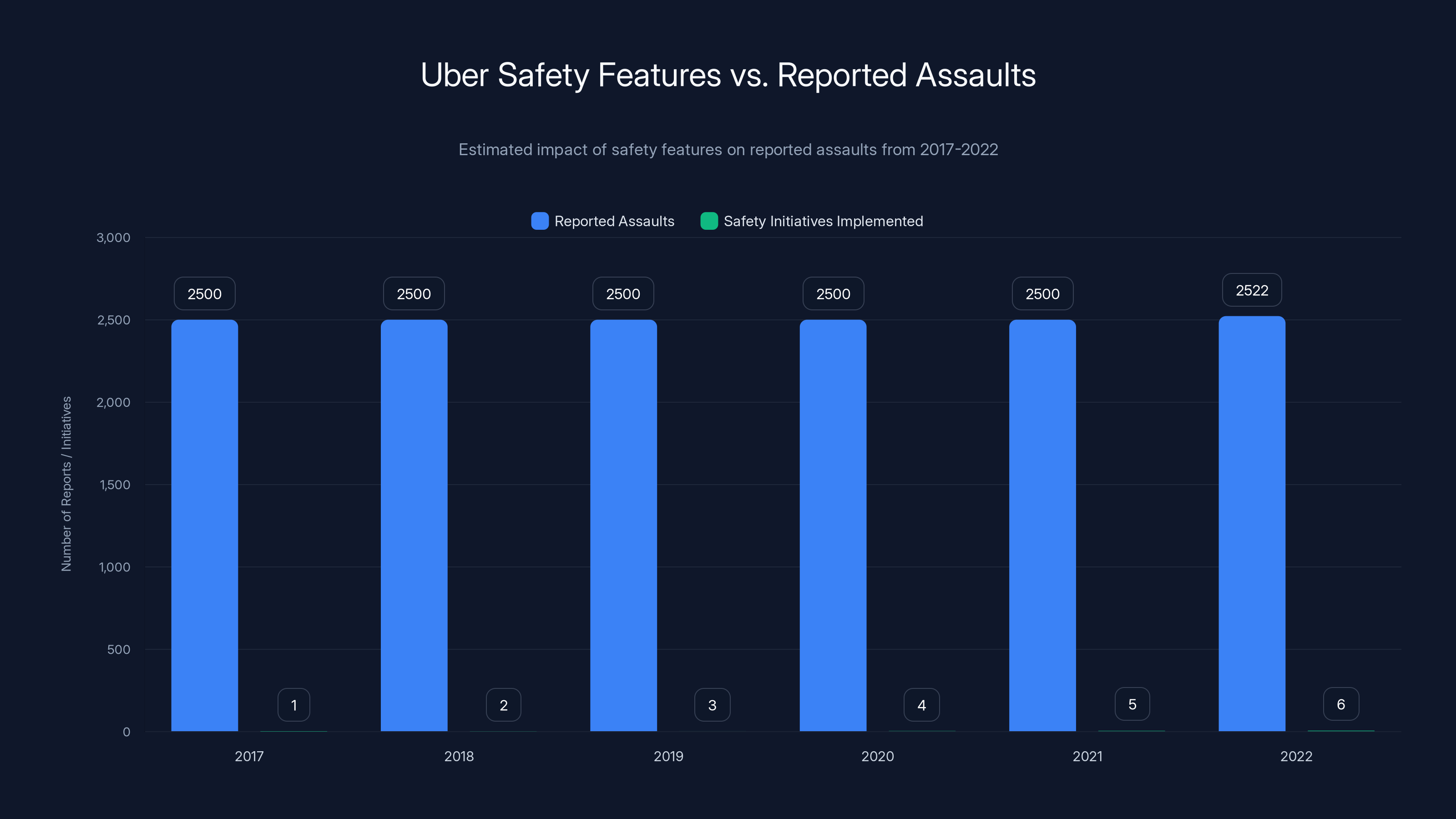

Despite implementing more safety features over the years, the number of reported assaults remained relatively constant. Estimated data based on available information.

The Safety Report Nobody Wanted to See

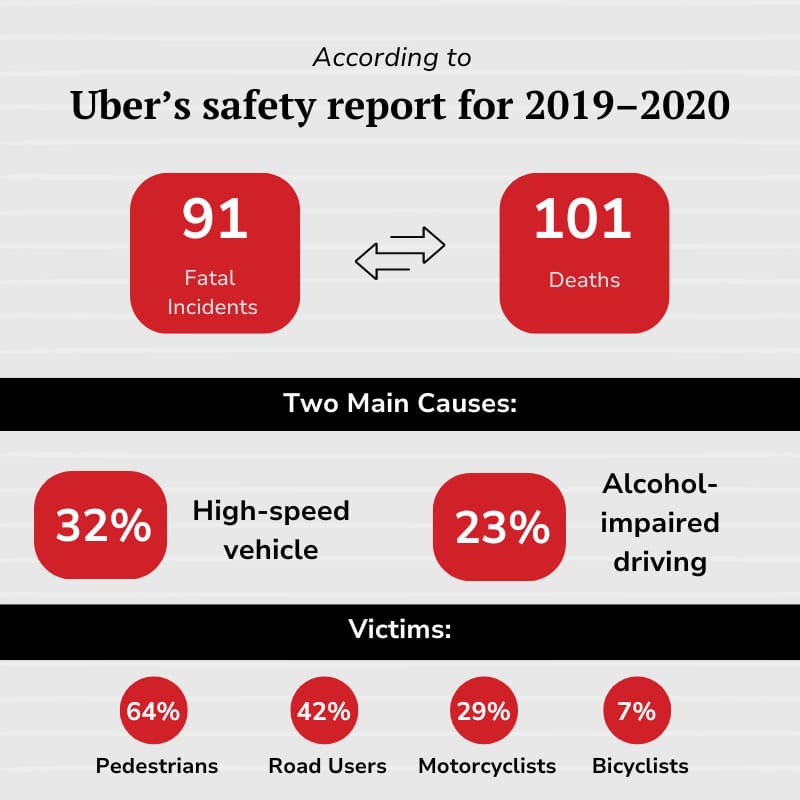

In 2024, Uber released a safety report covering 2017-2022. The timing felt strategic—after years of pressure from regulators and advocacy groups. The data inside was staggering.

12,522 reports of sexual assault across five years. Let that number sit for a moment. That's roughly 2,500 reports per year. If those numbers have held steady or grown, we're talking about thousands of assaults annually on Uber's platform.

The company's response? They pointed to safety initiatives they've implemented. Features like the Safety Toolkit, emergency contact alerts, and driver background checks. These are real features, and they might prevent some incidents. But they clearly haven't prevented most of them.

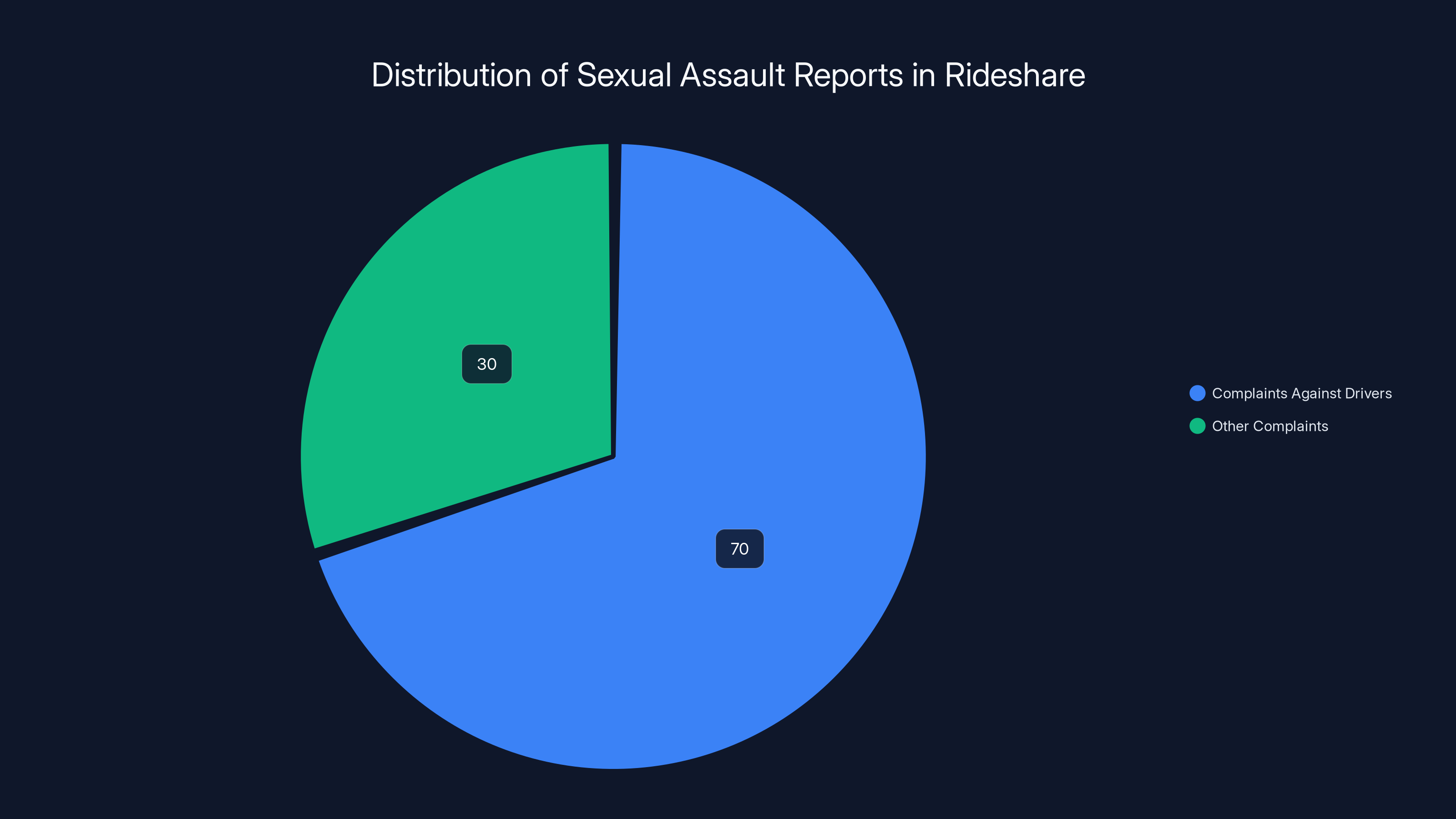

The "almost 70% of complaints against drivers" stat is important. This shows the problem isn't passengers assaulting each other primarily. It's drivers assaulting passengers. That's where Uber's responsibility becomes clear. They hire the drivers. They approve their background checks. They maintain their status on the platform.

When you compare Uber's safety infrastructure to what's technically possible, there's a gap. Real-time ride monitoring, mandatory panic buttons with dedicated emergency response teams, in-vehicle recording with consent, and more stringent background check protocols—these aren't new technologies. They're available.

The question becomes: did Uber choose not to implement stronger safety measures to save money? Or did they genuinely believe their current measures were sufficient? The jury apparently found the former more convincing.

According to Uber's safety report, 70% of sexual assault complaints were filed against drivers, highlighting a significant safety concern within the rideshare industry.

What Happened to Jaylynn Dean

Jaylynn Dean ordered an Uber to take her to a hotel in November 2023. Instead of a routine ride, she was assaulted by her driver. The trauma of that experience extends far beyond the physical assault. There's the psychological impact, the difficulty of coming forward, the legal process, and the public scrutiny that comes with being the first case of this kind.

Her case went to trial in Phoenix federal court. She testified about what happened. The driver's conduct. Uber's failure to prevent it. The jury heard her story and ruled in her favor.

That's the human element people sometimes miss in litigation discussions. Behind every lawsuit is a person whose life was changed by what happened to them. Dean had the courage to take this case public, which opened the door for the thousands of other cases waiting in the system.

Uber's initial statement after the verdict was dismissive. They said it "affirms that Uber acted responsibly." This sparked immediate backlash. How does a jury finding you liable affirm responsible behavior? The messaging was tone-deaf at best, insulting at worst.

The company has since adjusted its public statements, emphasizing their safety investments and commitment to rider protection. But actions speak louder than statements. If Uber truly prioritized safety, they might implement changes immediately rather than fighting the verdict.

The 3,000-Case Problem

This is where the Phoenix verdict gets interesting and terrifying for Uber simultaneously. There are 3,000+ similar cases consolidated in federal court, all overseen by Judge Charles Breyer.

These aren't random cases scattered across different jurisdictions. They're consolidated—all in one place, managed by one judge. This was a strategic move by attorneys to create consistency and efficiency in the legal process. It also creates leverage.

A bellwether verdict like the Phoenix case doesn't legally bind all the other cases. Each case stands on its own facts. But judges pay attention to how juries respond. Lawyers use early verdict outcomes to inform settlement discussions. Plaintiffs' attorneys gain confidence when early cases succeed. Defense attorneys reassess their positions.

If the $8.5 million verdict stands after appeal—and that's a big if—it could influence settlement discussions in thousands of other cases. Some defendants might settle rather than risk jury verdicts like the one in Phoenix.

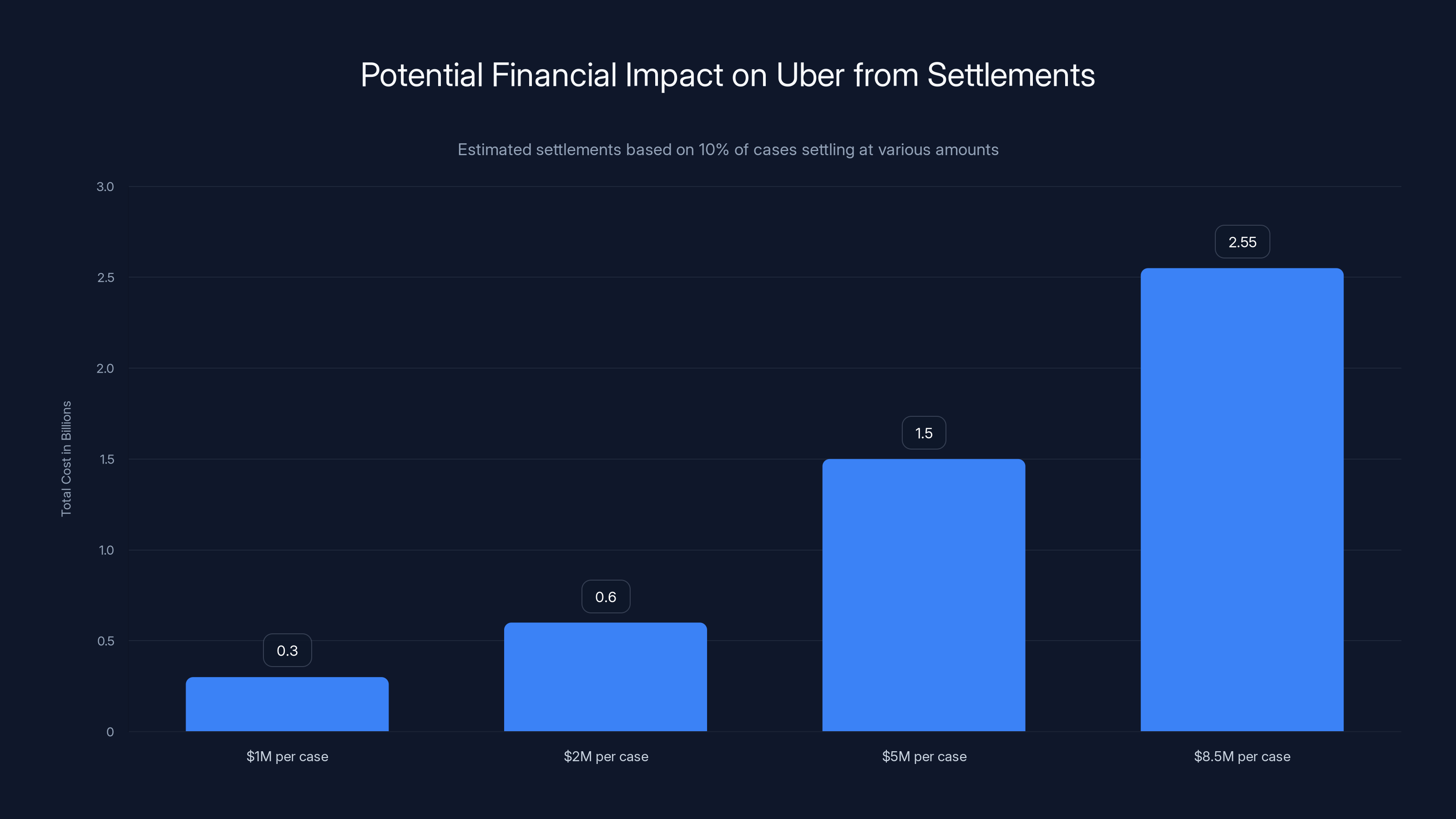

For Uber, the math is brutal. If even 10% of 3,000 cases settle for amounts anywhere near $8.5 million, you're looking at billions in liability. That's why appeals matter so much. Uber's entire defense strategy rests on overturning or significantly reducing this verdict.

But here's what makes this harder for Uber: juries don't always look kindly on mega-corporations fighting injury claims. There's a psychological element to litigation. Uber is enormously profitable and powerful. Victims are individuals harmed by the platform's failures. Juries see that imbalance.

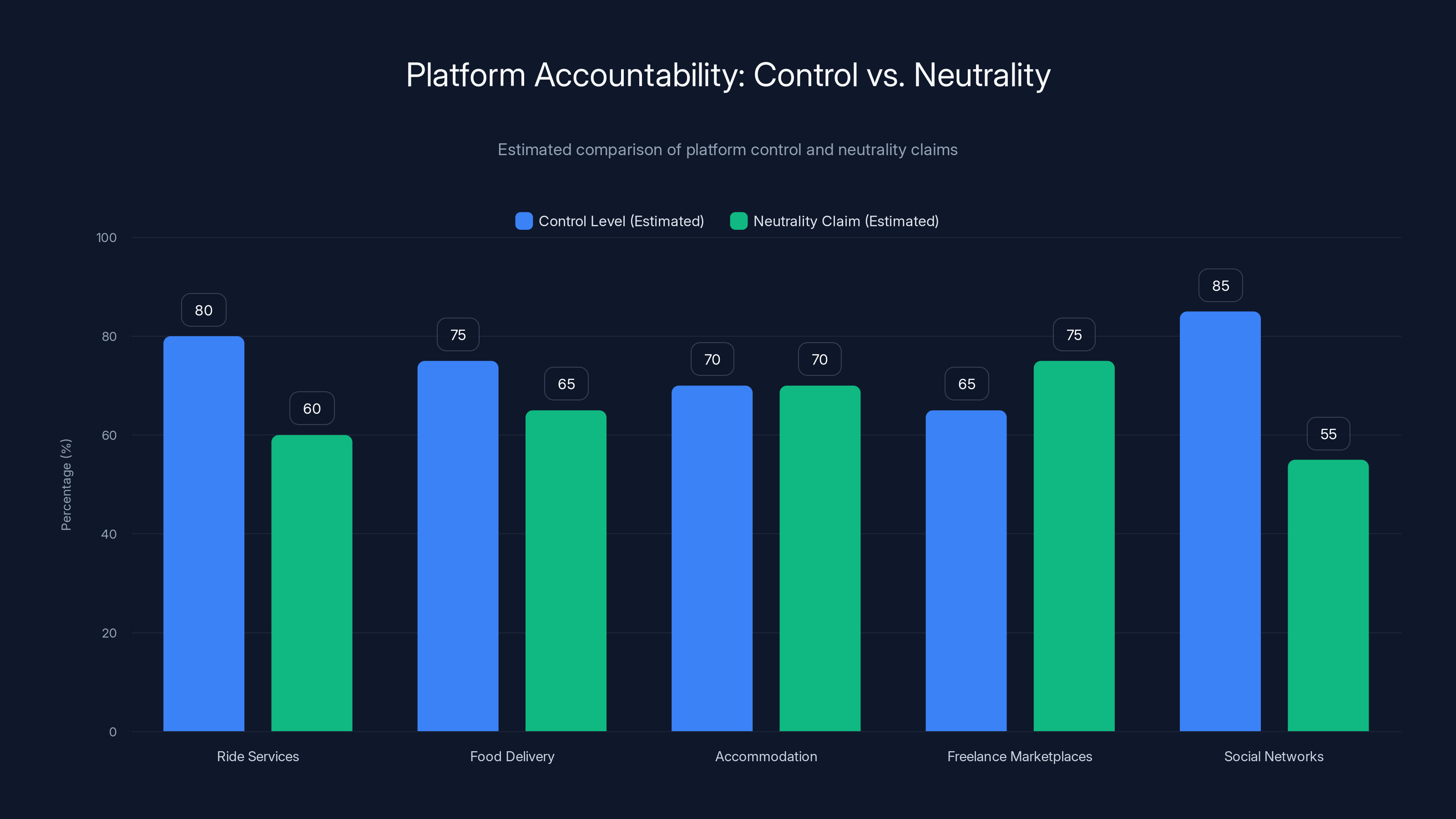

Estimated data shows that while platforms claim neutrality, their control over transactions and user interactions suggests significant responsibility. Estimated data.

Platform Liability vs. Corporate Responsibility

The legal theory at stake here extends beyond Uber. It affects all platforms that connect service providers with customers—everything from Task Rabbit to Instacart to Airbnb to Door Dash.

For decades, tech platforms relied on Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act. This law shields platforms from liability for content users create and upload. But the law was designed for different circumstances—websites hosting user reviews or message boards, not services where the platform actively matches, monitors, and profits from individual transactions.

The question courts are asking increasingly is: if you control the service, curate the providers, set the rules, collect payments, and monitor behavior, can you really hide behind platform immunity?

Uber wants to say yes. They're a technology platform, not a transportation company. They don't employ drivers; they have an independent contractor model. Therefore, they shouldn't be liable for driver misconduct.

The counterargument, which the Phoenix jury apparently accepted, is that Uber's control over the system is too extensive for them to claim liability immunity. They approve drivers. They rate drivers. They remove drivers. They set prices. They determine which requests drivers see. They handle payments. With that much control comes responsibility.

This tension will define rideshare regulation for the next decade. Can platforms operate as pure marketplaces with no responsibility for provider conduct? Or does active control over the marketplace mean they bear responsibility for what happens within it?

The Phoenix verdict suggests juries will find responsibility. But appeals courts might disagree. This is why the case will probably head to appellate courts, and potentially higher.

What Uber's Safety Initiatives Actually Do

Uber invests in safety features. They have legitimate reasons to do so—it makes their platform safer and more attractive to riders. But are these features sufficient? That's the question the jury found required improvement.

The company's Safety Toolkit includes emergency contact features, where riders can share their trip with trusted contacts. It includes an ability to report unsafe behavior during or after rides. It includes 24/7 support access. These are real features that have probably prevented harm in some cases.

Uber's background checks screen out drivers with serious criminal records. In most states, this includes felonies and certain misdemeanors. But background checks have significant limitations. They only catch documented crimes. Many assaults go unreported. Background checks don't predict future behavior.

The platform also uses ratings to identify problematic drivers. Low-rated drivers can lose access to the platform. But this reactive approach only works after incidents have already occurred. It's harm reduction, not prevention.

What's notably absent from Uber's safety toolkit: real-time ride monitoring by the company, mandatory in-vehicle cameras that Uber can access, dedicated emergency response teams trained specifically for assault situations, or mandatory rideshare insurance that covers assault.

Some of these features exist in certain markets or as pilot programs. But they're not universal. The question the jury seemed to be asking is: why not? If you have the technology, the resources, and the knowledge that assaults happen regularly on your platform, why not implement stronger protections?

Uber's answer likely comes down to cost and market competition. Adding more safety infrastructure costs money. It could slow rider response times or complicate the booking process. Competitors like Lyft might not implement the same features, creating a competitive disadvantage. These are business arguments, not safety arguments.

Juries don't usually find business arguments compelling when weighed against passenger safety.

If 10% of the 3,000 cases settle, Uber could face billions in liabilities depending on the settlement amount per case. Estimated data.

The Appeal and What's Next

Uber has promised to appeal the verdict. This is expected. The appeal will likely focus on whether the jury properly applied liability standards and whether the verdict is consistent with precedent.

Appellate courts apply a different standard than trial juries. Juries decide facts. Appellate courts review whether the law was applied correctly. Uber's attorneys will argue that even if the facts are true, the law doesn't support holding Uber liable.

They'll cite cases where platforms have successfully claimed immunity. They'll argue that independent contractor relationships shield companies from liability. They might argue that Uber's safety investments were reasonable, even if imperfect.

The plaintiffs' attorneys will counter that Uber's control over drivers and the platform goes beyond what immunity laws contemplate. They'll point to Uber's profit margin on every ride. They'll emphasize that Uber knew sexual assaults were happening and failed to strengthen protections.

The appellate process typically takes one to three years. During that time, all 3,000 other cases are likely paused, waiting to see if the verdict survives appeal. This is why bellwether cases take so long—they're not just about one victim's justice. They're about setting precedent for thousands of others.

If Uber loses on appeal, the options narrow. They could petition for a rehearing, request an emergency stay, or try to settle. A settlement would likely involve millions paid out to victims, some combination of strengthened safety features, and most importantly for Uber, a pause on the other 3,000 cases going to trial.

For context, when companies lose high-stakes litigation like this, settlements often include both monetary damages and injunctive relief—court orders requiring specific changes. Uber might have to implement certain safety features, hire an external safety officer, or submit to regular audits.

Rideshare Industry Implications

This verdict doesn't just affect Uber. Every rideshare company is watching. Lyft, the other major rideshare player in the US, faces similar liability exposure. So do smaller players like Sidecar, Juno, or regional services.

The verdict sends a signal to the entire industry: juries will hold you liable if you have power over your service but claim you bear no responsibility for safety failures. This could force rideshare companies to take safety more seriously across the board.

Companies might respond in several ways. Some will strengthen safety features proactively, hoping to prevent future incidents and avoid litigation. Others might increase insurance requirements or shift more liability to drivers. Some might settle existing claims quickly rather than risk jury trials.

Regulatory bodies are watching too. States and cities regulate rideshare operations. They've been pushing for stronger safety requirements for years. A verdict that holds companies liable for safety failures gives regulators ammunition to impose more stringent requirements.

We might see regulations requiring real-time ride monitoring, mandatory in-vehicle cameras, background check standards with no exceptions, insurance minimums, and assault response protocols. These aren't hypothetical—several cities have already proposed or implemented some of these requirements.

The verdict could accelerate regulatory trends significantly.

If Uber settled all 3,000 cases at the Phoenix verdict amount, it could face a

The Broader Question of Platform Accountability

The Uber case raises a question that extends far beyond rideshare: how much responsibility should digital platforms bear for what happens through their services?

You see this tension everywhere. Food delivery platforms, ride services, accommodation platforms, freelance marketplaces, social networks. They all connect buyers and sellers. They all claim to be neutral platforms. They all make billions while asserting they bear no responsibility for user conduct.

But as these platforms grow in influence and profitability, the liability question grows sharper. If you take 15-25% of every transaction, if you match parties, if you rate participants, if you remove problem users—can you really be neutral?

The Phoenix verdict suggests a jury thought not. They looked at Uber's control, Uber's profits, Uber's knowledge of safety issues, and Uber's failure to implement preventive measures. They concluded that companies with that level of control and profit can't hide behind neutrality arguments.

This framework could apply to other platforms. Food delivery companies that match drivers with orders, set pricing, monitor behavior, and profile users could face similar liability for driver misconduct. Accommodation platforms could face liability for host misconduct. Freelance platforms could face liability for contractor misconduct.

The difference in each case would be the specific facts—what did the company know, what control did they have, what preventive measures were available but not implemented? But the basic framework of holding platforms accountable for harm their services enable seems likely to hold.

For consumers, this could mean safer platforms in the long run. Companies forced to implement stronger safety measures might prevent more harm. But it could also mean higher costs—platforms might pass costs of safety improvements to users through higher prices or fees.

Lessons from Other Safety Litigation

The Uber case isn't the first time a company has faced massive liability for safety failures. Looking at how similar cases resolved offers insight into possible outcomes.

Taxi companies faced years of litigation over sexual assault before the rideshare boom. Hotels faced litigation over room security failures. Nightclubs faced litigation over security lapses leading to violence. In each case, companies initially fought liability, then gradually implemented better safety measures as legal pressure mounted.

These cases typically follow a pattern. Early verdicts go to plaintiffs. Companies appeal aggressively. Eventually, settlements emerge that include both monetary damages and injunctive relief requiring safety improvements. The injunctions often drive industry-wide changes because they become blueprints for regulation.

In the hotel industry, litigation over sexual assault led to improved door locks, better employee training, and security protocols. These changes didn't come from altruism. They came from companies facing liability realizing that prevention costs less than litigation.

The Uber case might follow a similar trajectory. If the verdict stands, we'll likely see:

- Aggressive appeals while still making safety improvements to manage PR damage

- Settlement talks with some subset of the 3,000 cases

- Introduction of new safety features across the platform

- Regulatory requirements tightening around background checks and monitoring

- Competitors implementing similar features to avoid similar liability

The timeline for all this could span five to ten years. The impact on rider safety could be significant, but only if the changes address root causes rather than just appearing to address them.

What Juries Actually Think About Tech Company Liability

Here's something important that legal analysts discuss: what do regular people—jurors—think about when they hear these cases?

Juries aren't impressed by Silicon Valley mythology about disruption and innovation. They're regular people who've used these services. Many have experienced safety concerns on rideshare platforms. They understand that companies have the ability to prevent harm.

When a jury hears that a company knew sexual assaults were happening at a rate of 2,500+ per year and chose not to implement stronger prevention measures, they see corporate negligence. They see a company prioritizing growth and profit over safety.

The Phoenix jury apparently reached that conclusion. They didn't buy Uber's argument that they're just a neutral platform. They looked at the company's control, knowledge, resources, and choices—and found them wanting.

This matters because it suggests juries in other similar cases might reach similar conclusions. Uber can't just argue technical immunity anymore. They have to convince juries that their safety efforts were reasonable. And 2,500+ annual assaults make that argument very difficult.

Future defendants will see this and potentially change their defense strategy. Rather than arguing they bear no responsibility, they might focus on arguing their safety measures were reasonable and that the plaintiff's case was an outlier. That's a more persuasive argument to jurors than claiming complete immunity.

The Economic Impact on Rideshare Economics

If Uber faces billions in settlement costs across the 3,000 cases, what happens to the platform's economics?

Uber is profitable. The company made billions in revenue last year. But rideshare markets are intensely competitive. Margins are tight. Adding billions in settlement costs and implementing more expensive safety measures affects the business model.

Uber might respond by raising prices for riders, reducing payments to drivers, or both. They might exit certain markets where liability exposure is highest. They might shift safety costs to drivers through insurance requirements or contract terms.

For riders, the impact could be negative initially—higher prices. For drivers, it could be mixed—lower payouts but also less liability if safety responsibility shifts more clearly to the company.

The longer-term impact depends on how thoroughly the liability question gets resolved. If companies accept responsibility for safety as part of their business model, they'll price for it. If they find ways to shift responsibility to drivers or regulators, costs might not increase as much.

But the precedent set by the Phoenix verdict suggests the courts increasingly expect platforms to bear responsibility for safety, which will eventually translate to higher platform costs and likely higher consumer prices.

Regulatory Response and Future Requirements

Governments are already thinking about how to respond to cases like Uber's. Some regulatory bodies were waiting for litigation to clarify liability before writing regulations. The Phoenix verdict gives them more confidence to act.

We'll likely see new regulations requiring:

- Mandatory background checks with specific standards (not just company discretion)

- Real-time monitoring of rides (GPS data, panic buttons)

- Insurance requirements covering assault and harm

- Dedicated response teams for safety emergencies

- Regular safety audits by third parties

- Driver training on safety protocols

- Transparent reporting of safety incidents

These regulations will increase operating costs for rideshare companies. But they'll also create a more level competitive field where all companies bear the same requirements. That might actually be preferable to facing unpredictable litigation outcomes.

Some cities are already moving in this direction. New York City has proposed specific rideshare safety requirements. California has considered broader regulations around gig economy safety. Federal regulators might eventually get involved if companies don't voluntarily improve safety to regulatory satisfaction.

The Uber verdict accelerates all these regulatory trends. It gives regulators evidence that voluntary company efforts aren't sufficient. Now they have legal grounds to mandate specific safety measures.

The Larger Conversation About Consumer Safety

Ultimately, the Uber verdict raises a question that extends beyond rideshare: what does the public expect from companies that control digital services?

People understand that absolute safety is impossible. No system prevents all harm. But people expect reasonable efforts. When a company knows that thousands of assaults happen on their platform annually and has the resources to implement stronger prevention measures but chooses not to, most people find that unreasonable.

The Uber case is about codifying that intuition into law. Companies can't claim immunity while they profit from control. They can't argue they're neutral while they curate, match, rate, and monitor. They have power, they make money, and therefore they have responsibility.

This could reshape how digital companies think about their platforms. It could mean better safety across the board. It could mean higher costs and friction in digital services. It could mean more regulation.

But the alternative—allowing companies with enormous control and profit to disclaim all responsibility for safety—is becoming increasingly untenable to juries and judges.

The Phoenix verdict signals that shift clearly.

Moving Forward: What Changes Are Coming

Based on litigation patterns and regulatory trends, several changes will likely unfold over the next few years:

First, Uber will appeal and likely face appeals through multiple levels. This process will take years. During that time, settlement discussions will accelerate. We'll probably see Uber settle a significant portion of the 3,000 cases for some combination of monetary damages and safety changes.

Second, Lyft and other rideshare companies will proactively implement stronger safety measures to avoid similar litigation. They'll invest in better monitoring, response teams, and insurance coverage.

Third, regulators will respond with mandated safety requirements. Some of these will track what smart companies implement voluntarily; others will go further.

Fourth, the precedent will extend to other platforms. Food delivery, accommodation, freelance work, and other platform-mediated services will face pressure to implement better safety measures.

Fifth, insurance markets will evolve to cover platform-mediated risks. This will add costs but also clarify responsibility.

Last, consumer expectations will shift. People will expect platforms to implement known safety measures. The standard of "reasonable care" will become more specific and stringent.

All of this takes years. But the Phoenix verdict marks a turning point. It says to platforms: you control these services, you profit from them, you have power over them. Therefore, you have responsibility for safety within them.

That principle, once established, changes everything about how digital platforms operate.

FAQ

What does it mean that Uber is liable for sexual assault?

The verdict means a jury found Uber negligent in rider safety. It doesn't mean Uber committed sexual assault—the driver did. It means Uber failed to take reasonable precautions to prevent a foreseeable harm despite having the power and resources to do so. This is a legal liability based on negligence, not direct criminal conduct by Uber.

Why does this verdict matter if there are 3,000 similar cases?

This is the first case to go to trial, which makes it a "bellwether case." Judges, lawyers, and other plaintiffs watch how juries respond to these first cases because they often influence how similar cases proceed. The verdict doesn't legally bind the other 3,000 cases, but it sends a powerful signal about how juries view Uber's responsibility for safety, which typically influences settlement discussions and jury behavior in subsequent trials.

Can Uber overturn the verdict in appeal?

Yes, Uber can appeal, and appeals courts might overturn or reduce the verdict. Appellate courts apply different legal standards than juries—they review whether the law was applied correctly, not just whether facts are true. Uber will argue that liability law doesn't support holding platforms responsible for driver conduct, but plaintiffs will counter that Uber's level of control over drivers means they can't hide behind platform immunity.

How much could Uber end up paying in total across all 3,000 cases?

If all 3,000 cases settled at the Phoenix verdict amount of

What safety features does Uber have, and why weren't they sufficient?

Uber offers emergency contact sharing, the ability to report unsafe behavior, 24/7 support access, and driver background checks. These features prevent some harm but don't prevent most sexual assaults. The jury apparently found these measures insufficient given that Uber knew of 12,500+ sexual assault reports over five years and had more advanced safety options available (real-time monitoring, mandatory cameras, dedicated assault response teams) that weren't universally implemented.

Will this verdict make rideshare safer?

Likely yes, but not immediately. The verdict will probably trigger changes over several years as companies implement stronger safety measures to avoid similar liability, regulators impose requirements, and settlements include safety improvements. However, the timeline is long—appeals take years, regulatory changes take time, and implementation takes additional time. Real safety improvements probably won't be widespread for three to five years.

Does this verdict affect other platforms like Door Dash, Airbnb, or Task Rabbit?

Indirectly, yes. The verdict establishes a legal principle that platforms with control over service providers can be held liable for foreseeable harms they fail to prevent. Other platforms that match users with service providers, rate participants, and profit from transactions could face similar liability arguments. However, each case depends on specific facts about what the company knew, what control they had, and what preventive measures were available.

What are Uber's main arguments in appeal?

Uber will likely argue that federal law shields platforms from liability for independent contractor actions, that jury verdicts shouldn't override platform immunity protections, that their safety efforts were reasonable, and that holding platforms liable for all foreseeable harms is economically impractical. Plaintiffs will counter that Uber's control over drivers exceeds what immunity laws contemplate and that companies profiting billions from services can't claim to be neutral platforms.

How does Uber's safety report impact the litigation?

The safety report showing 12,522 sexual assault reports over five years was devastating to Uber's liability defense. It established that the company knew sexual assaults occurred regularly on its platform. Combined with the ability to implement stronger preventive measures, this knowledge strengthened plaintiff arguments that Uber was negligent in failing to prevent or reduce assault rates more aggressively.

What happens to the other 3,000 cases while Uber appeals?

Most are likely paused pending the appeal outcome. Judges want to see if the verdict survives appeal before allowing similar cases to proceed to trial. This pause typically lasts one to three years. During this time, settlement discussions often accelerate as parties use the bellwether outcome to reassess case values and litigation risk. Some cases might eventually settle, others might proceed to trial if appeals change the legal landscape.

Key Takeaway: The Phoenix verdict marks a turning point in how courts view platform liability for safety. Companies that control digital services, profit from them, and know that harms occur will increasingly be held responsible for failing to prevent foreseeable harms, especially when they have the resources to do so. This principle will reshape rideshare safety, influence other platform businesses, and accelerate regulatory requirements across the digital economy.

Key Takeaways

- Federal jury found Uber liable for sexual assault, ordering $8.5 million damages—the first verdict in 3,000+ consolidated cases

- Uber's defense that it's a neutral platform with no liability responsibility for driver conduct was rejected by the jury

- The company's own safety data showed 12,522 sexual assault reports over five years, nearly 70% involving drivers assaulting passengers

- This bellwether verdict could influence thousands of pending cases and potentially cost Uber billions in total liability if similar outcomes persist

- The verdict signals to digital platforms that controlling services, profiting from them, and knowing harms occur creates responsibility to prevent those harms

Related Articles

- The SCAM Act Explained: How Congress Plans to Hold Big Tech Accountable for Fraudulent Ads [2025]

- Meta's "IG is a Drug" Messages: The Addiction Trial That Could Reshape Social Media [2025]

- Meta's Research Dilemma: Zuckerberg's Unsealed Emails Reveal Strategic Shift [2025]

- Meta Teen Privacy Crisis: Why Senators Are Demanding Answers [2025]

- How Right-Wing Influencers Are Weaponizing Daycare Allegations [2025]

- Grok's Deepfake Problem: Why AI Keeps Generating Nonconsensual Intimate Images [2025]

![Uber Liable for Sexual Assault: What the $8.5M Verdict Means [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/uber-liable-for-sexual-assault-what-the-8-5m-verdict-means-2/image-1-1770383159850.jpg)