Introduction: The Great Memory Shuffle

Something shifted in the memory market last year, and most people didn't notice until their RAM prices jumped or stock dried up. Micron, one of the world's largest memory manufacturers, quietly retired its consumer-facing Crucial brand to focus on enterprise DRAM and storage for AI infrastructure. The move triggered immediate backlash from DIY PC builders, content creators, and anyone who's ever upgraded their own laptop.

Here's the thing: this isn't just about Crucial disappearing. It's a symptom of something much bigger happening in the semiconductor industry. Enterprise AI is consuming more memory than ever before, data centers are hoarding capacity, and the traditional consumer market is getting starved for inventory. When a company like Micron makes a calculated bet that enterprise revenue is worth more than consumer loyalty, it sends ripples across the entire PC ecosystem.

I started digging into this after noticing RAM prices creeping back up in early 2025, even though we were supposed to be in a supply surplus. Turns out, the surplus was never really for consumers. It was earmarked for servers, data centers, and AI acceleration clusters long before it hit retail shelves.

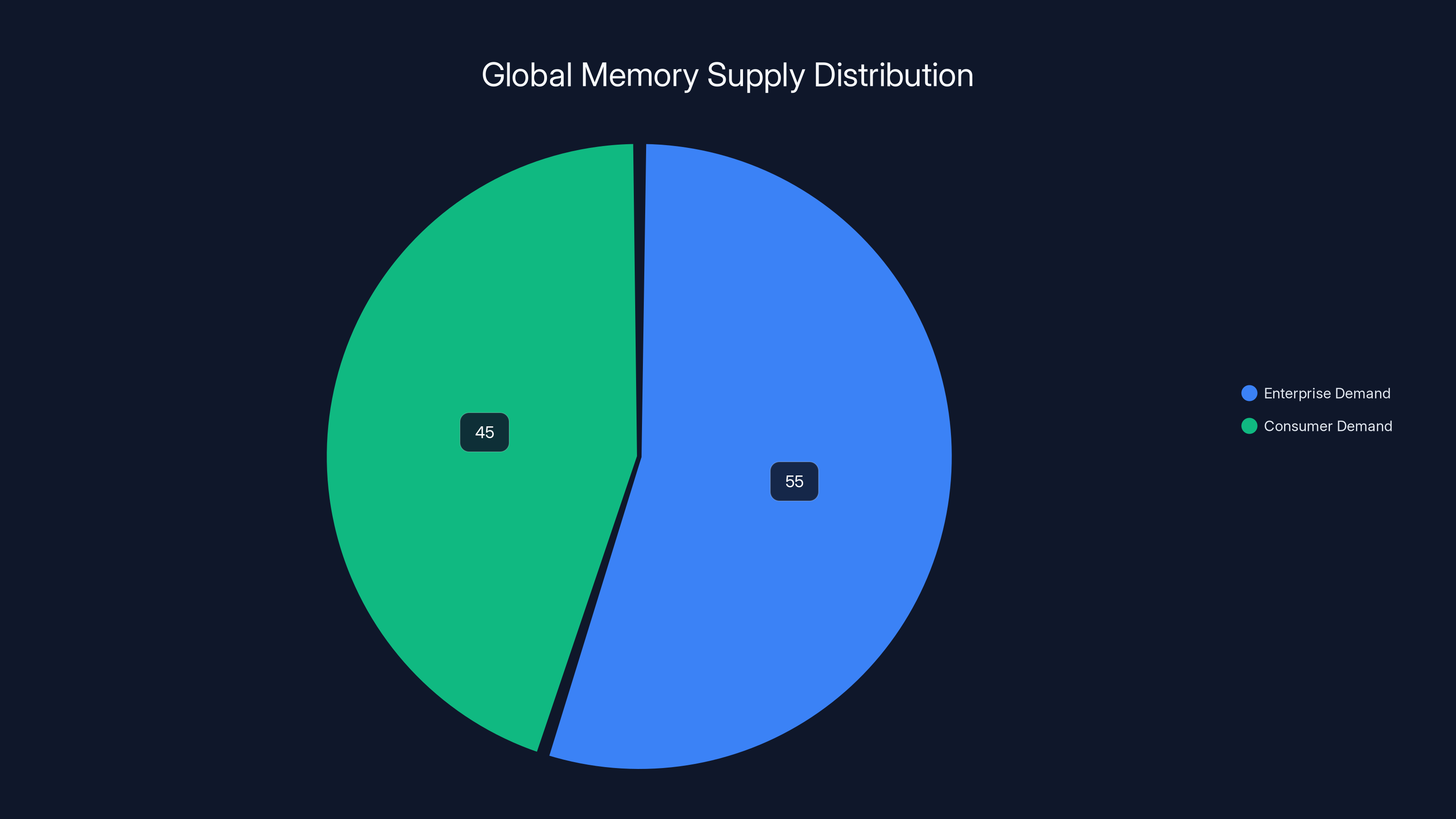

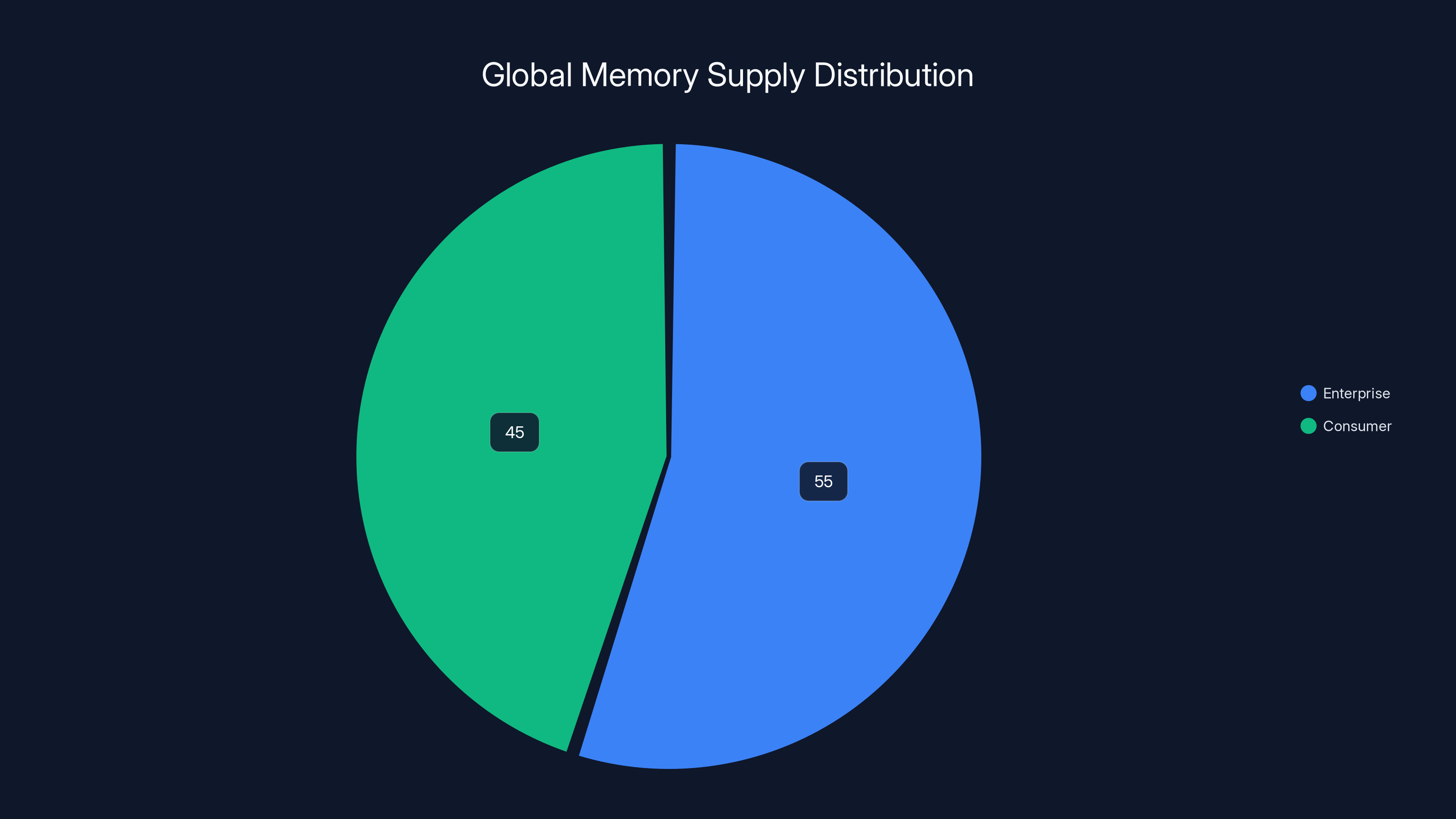

Micron's VP of Marketing, Christopher Moore, recently broke the company's silence on this strategy, insisting that Micron isn't abandoning consumers entirely. But the numbers tell a different story. Enterprise now accounts for 50% to 60% of global memory supply. That's not a sideline anymore. That's the main event. Consumers got relegated to whatever's left.

This article digs into what Micron's pivot actually means: for your next laptop upgrade, for gaming PC builders, for pricing through 2028, and for the broader shift toward AI-first manufacturing. Because here's the reality—understanding why RAM is expensive isn't just about knowing the numbers. It's about understanding how decisions at the C-suite level directly impact your ability to build or upgrade a computer without breaking the bank.

TL; DR

- Micron retired the Crucial consumer brand to focus 50-60% of production on enterprise DRAM, leaving consumer channels undersupplied

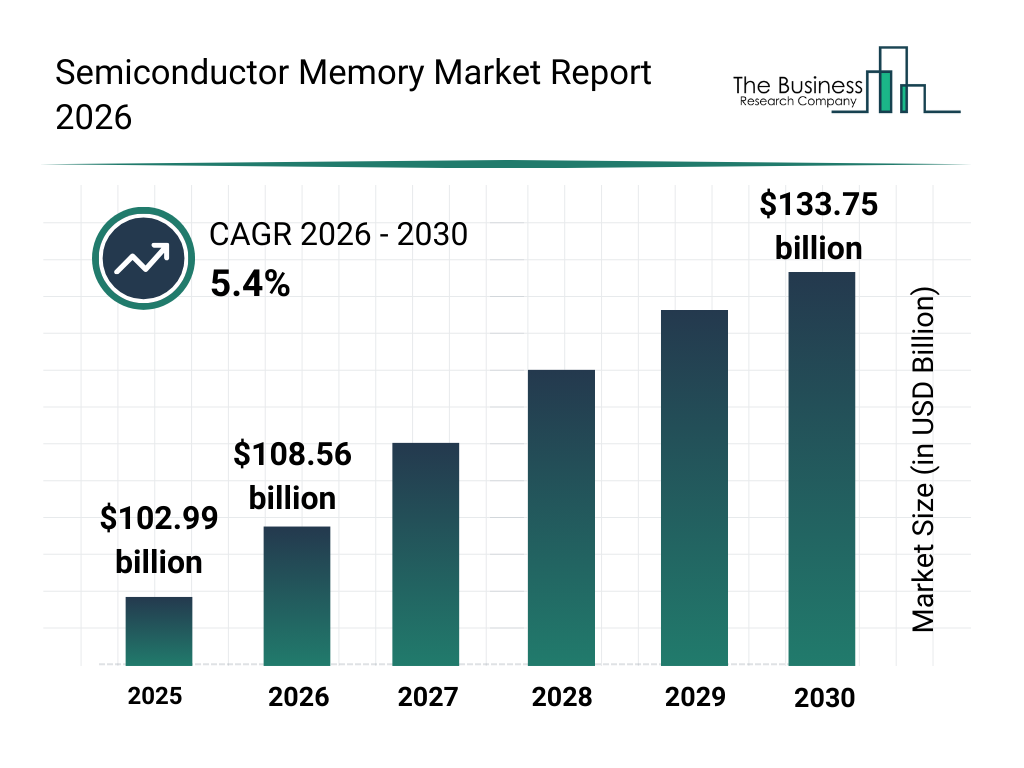

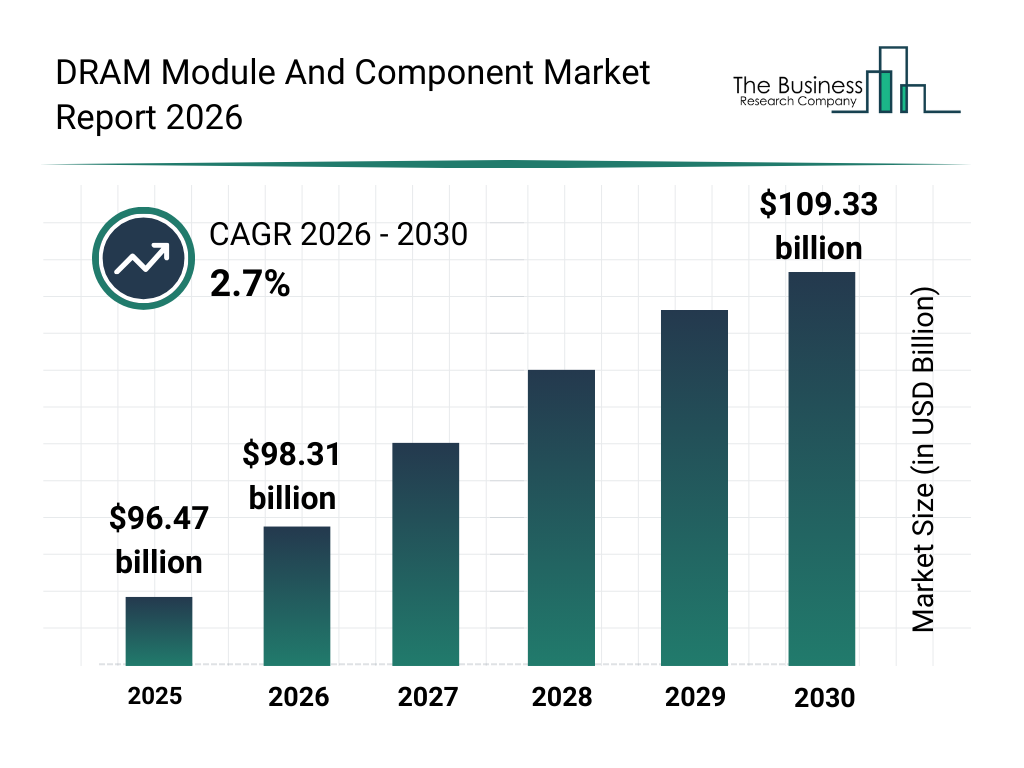

- New manufacturing capacity won't materialize until 2028, meaning DRAM shortages and elevated prices will persist for years

- Enterprise AI demand has fundamentally restructured the memory market, with data centers consuming historically unprecedented memory volumes

- DIY builders and laptop upgrades face constrained supplies while OEM partnerships with Dell and Asus ensure corporate customers get priority access

- This isn't unique to Micron—the entire industry is prioritizing enterprise, forcing consumers to adapt to a seller's market

Enterprise demand consumes approximately 55% of global memory supply, highlighting its priority over consumer segments. Estimated data.

The Memory Market's Quiet Transformation

The memory market didn't crash overnight. It transformed gradually, then suddenly. For the past two years, we've been watching a fundamental restructuring of who gets DRAM and when. Micron's decision to retire Crucial wasn't reckless. It was strategic. It was also the moment when the PC building community realized they weren't the priority anymore.

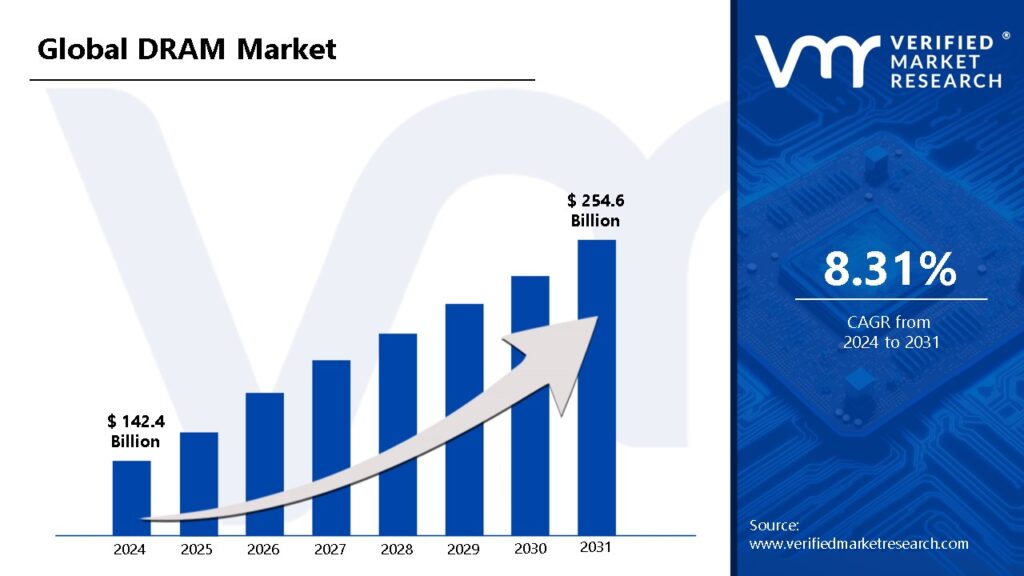

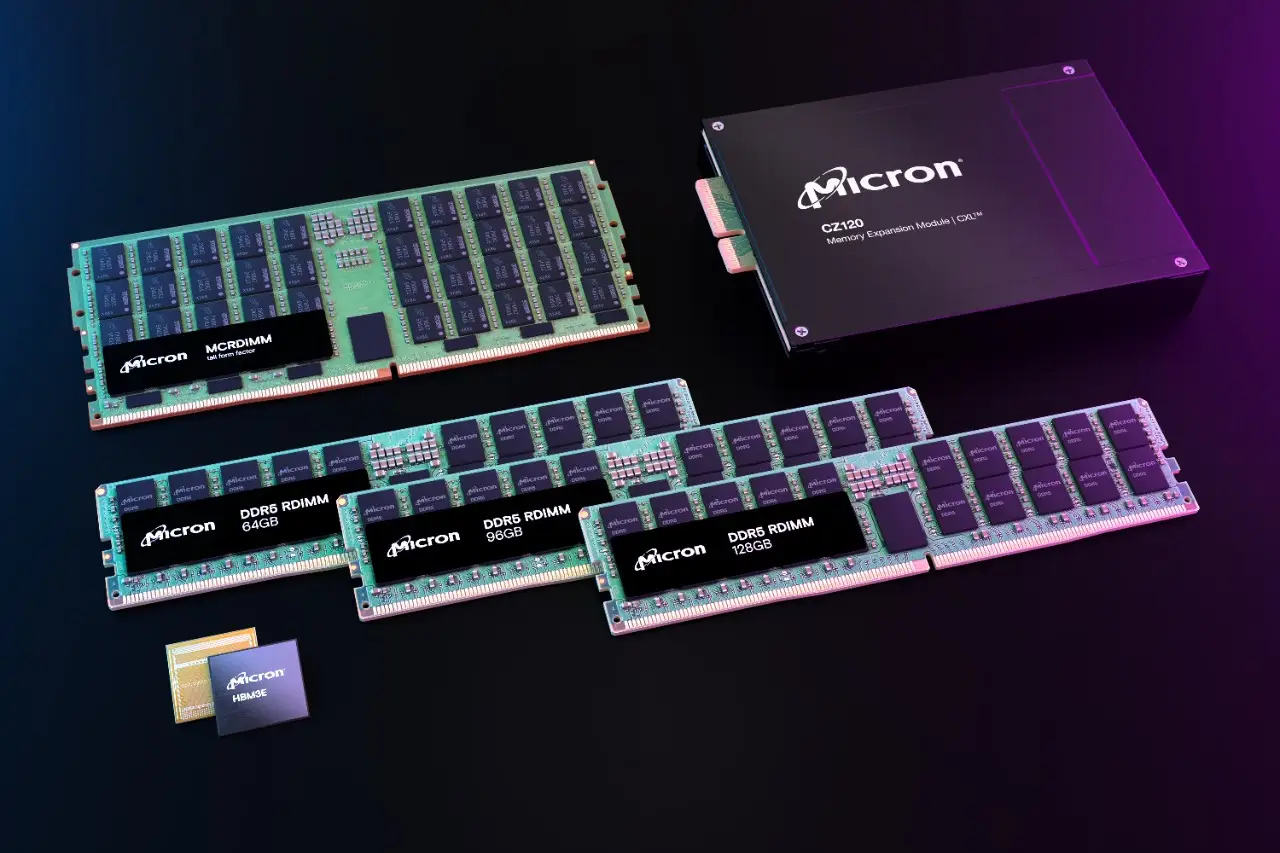

To understand why Micron made this move, you need to understand what happened to enterprise demand. Starting around 2023, AI infrastructure became the most capital-intensive computing challenge in human history. Every major tech company—OpenAI, Google, Meta, Microsoft—started building out massive data centers to train and run large language models. These facilities don't need a few gigabytes of RAM. They need terabytes of DRAM deployed across clusters of thousands of GPUs.

A single data center running state-of-the-art language models might consume more memory than entire regional PC markets. That's not hyperbole. That's the actual scale we're talking about.

Micron recognized this trend early and made a business decision: enterprise revenue is more predictable, larger in absolute terms, and comes with long-term contracts that guarantee minimum purchase volumes. Consumer memory is fragmented across thousands of retailers, requires constant price competition, and generates thinner margins. From a shareholder perspective, the choice was obvious.

But Micron isn't alone in this calculation. Samsung, SK Hynix, and Kioxia have all been quietly shifting capacity toward enterprise and data center use cases. The entire DRAM market is experiencing the same gravitational pull toward AI infrastructure. When every major supplier makes the same strategic choice simultaneously, it creates a structural shortage for everyone else.

The Crucial retirement was just the most visible sign of this shift. It's the moment when a major brand, trusted by millions of PC builders, simply ceased to exist as a consumer product line. If you've been building PCs for a decade, Crucial was probably your default choice. Now it's gone.

Enterprise DRAM Consumption: The 50-60% Reality

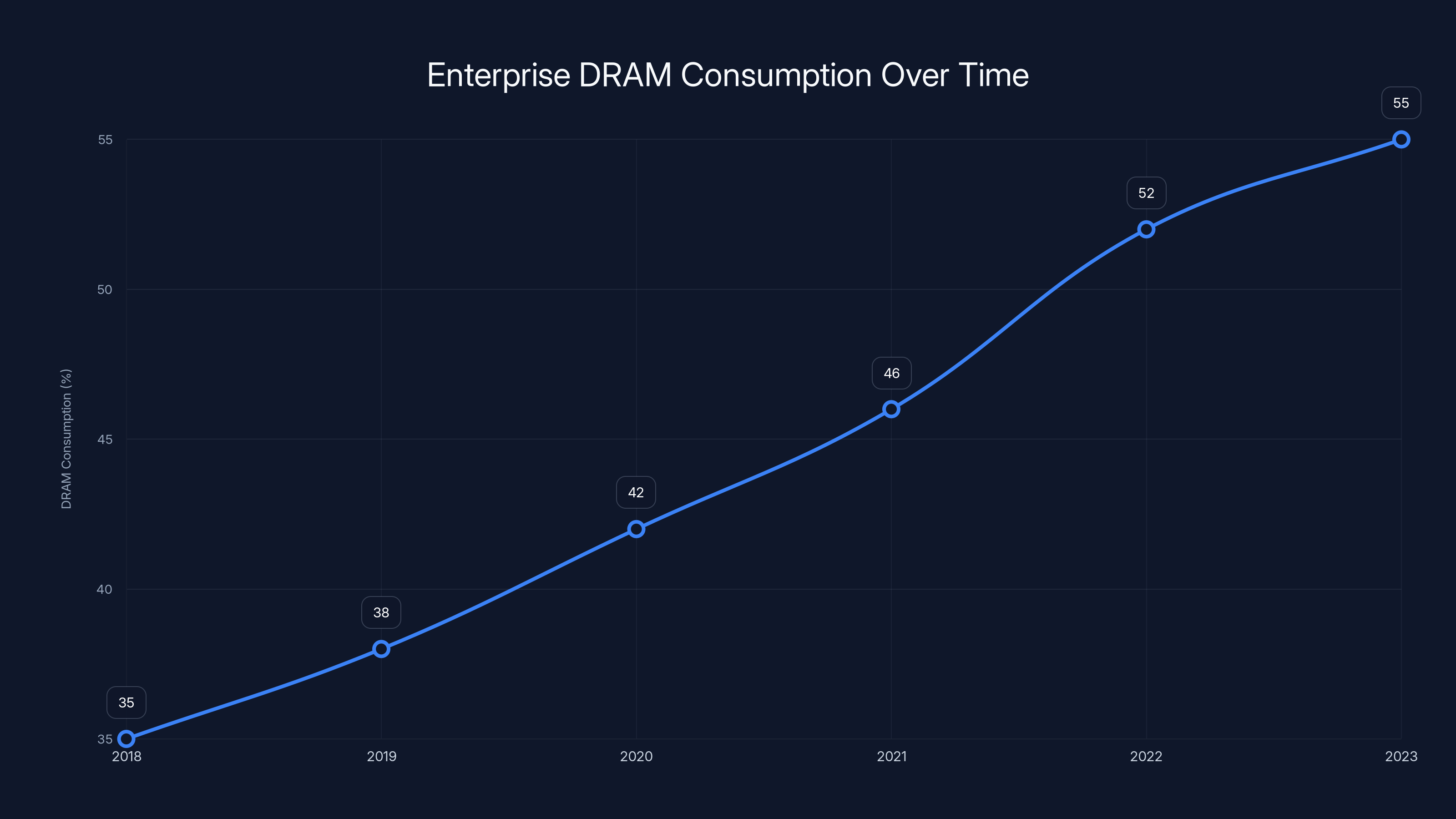

Let's talk about the actual numbers, because they're staggering. Christopher Moore, Micron's VP of Marketing, stated plainly that enterprise now consumes 50% to 60% of global memory supply. That's the highest proportion in history. To put this in perspective, just five years ago, enterprise was consuming closer to 35% of supply.

What changed? AI happened. Specifically, large language models happened.

Training a single model like GPT-4 requires enormous amounts of DRAM for several reasons. First, you're loading massive parameter sets into memory. Modern large language models have hundreds of billions of parameters. Storing, accessing, and updating these parameters requires gigantic amounts of fast memory. Second, you're running inference at scale, which means serving queries from thousands of concurrent users. Each inference request needs its own working memory space.

Then there's the data movement problem. Modern AI workloads are bottlenecked by how fast you can move data between memory and computation units. More memory bandwidth means better performance. So data centers don't just want more DRAM—they want DRAM with specialized high-bandwidth interconnects, which requires custom engineering and even higher price points.

Micron and other suppliers have responded to this demand by dedicating production lines specifically to enterprise DRAM. These aren't consumer modules you'd find in retail channels. They're specialized products with custom packaging, higher reliability requirements, and longer qualification cycles. Once a data center commits to a specific memory architecture, switching costs are enormous. That creates lock-in, which means enterprise customers get preferential treatment.

Here's the catch: building a memory chip for enterprise takes similar time and manufacturing resources as building a memory chip for a consumer laptop. But the enterprise version generates 2-3x the revenue per unit. When you're running a manufacturing facility at full capacity, the math becomes obvious. You prioritize whatever generates the most revenue per square centimeter of fab space.

The Cannibalization Problem

There's a technical constraint that makes this problem worse: switching DRAM production between different market segments is expensive and time-consuming. Micron can't simply reprogram their fabs to make consumer DRAM one week and enterprise DRAM the next. Each product line requires specific equipment configurations, different process parameters, and careful optimization.

Switching between production types requires several days of downtime, equipment recalibration, and waste from failed parts during the transition. In an industry with razor-thin margins and massive fixed costs, every hour of downtime is expensive. This creates a disincentive to maintain diverse product portfolios. It's more efficient—and more profitable—to specialize.

Micron's decision to concentrate production on enterprise segments is therefore both a strategic choice and an economic inevitability. Once you start down that path, going back becomes progressively harder.

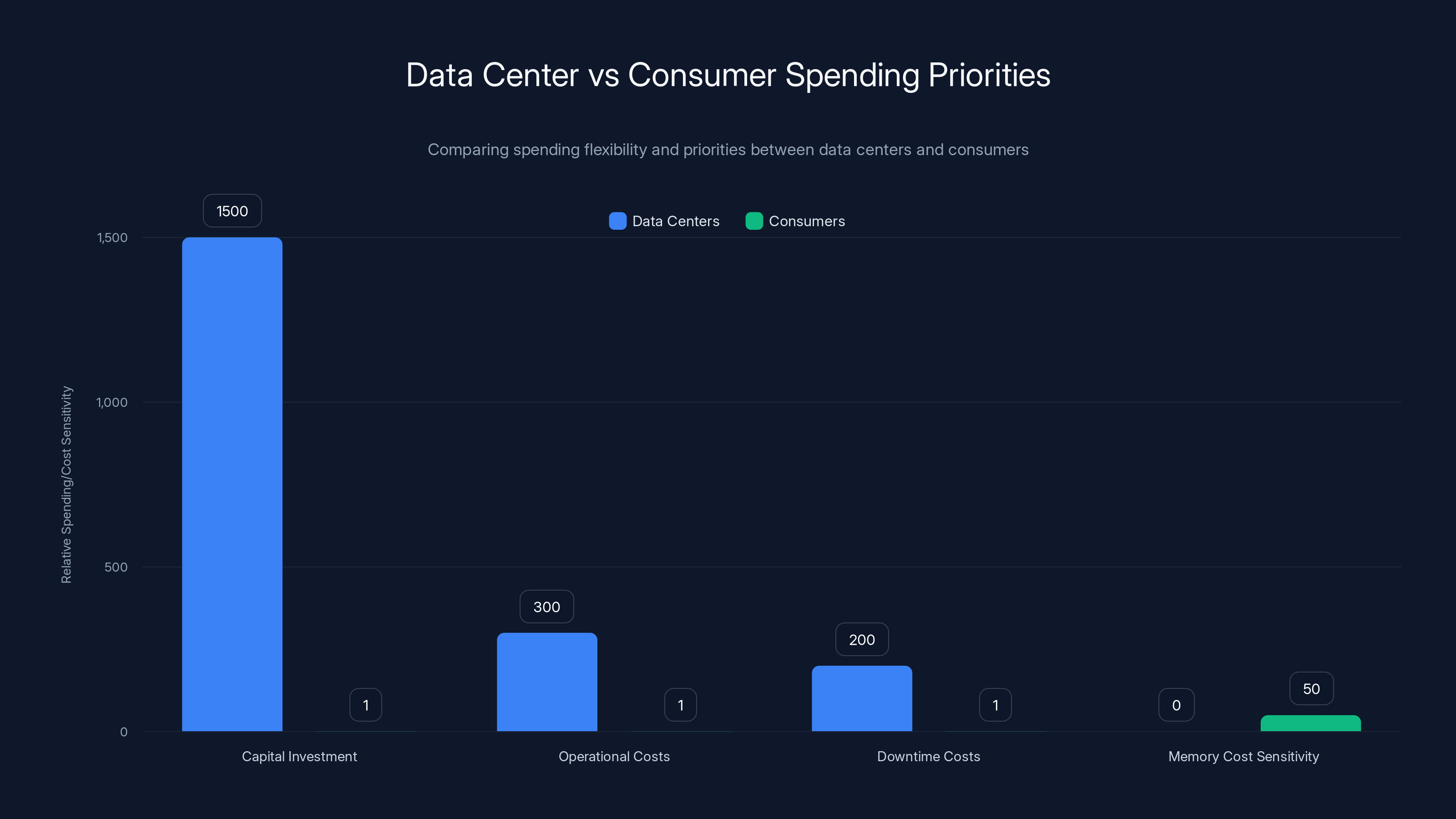

Data centers have significantly higher capital and operational costs and are less sensitive to memory price increases compared to consumers. Estimated data.

Why Micron Retired the Crucial Brand

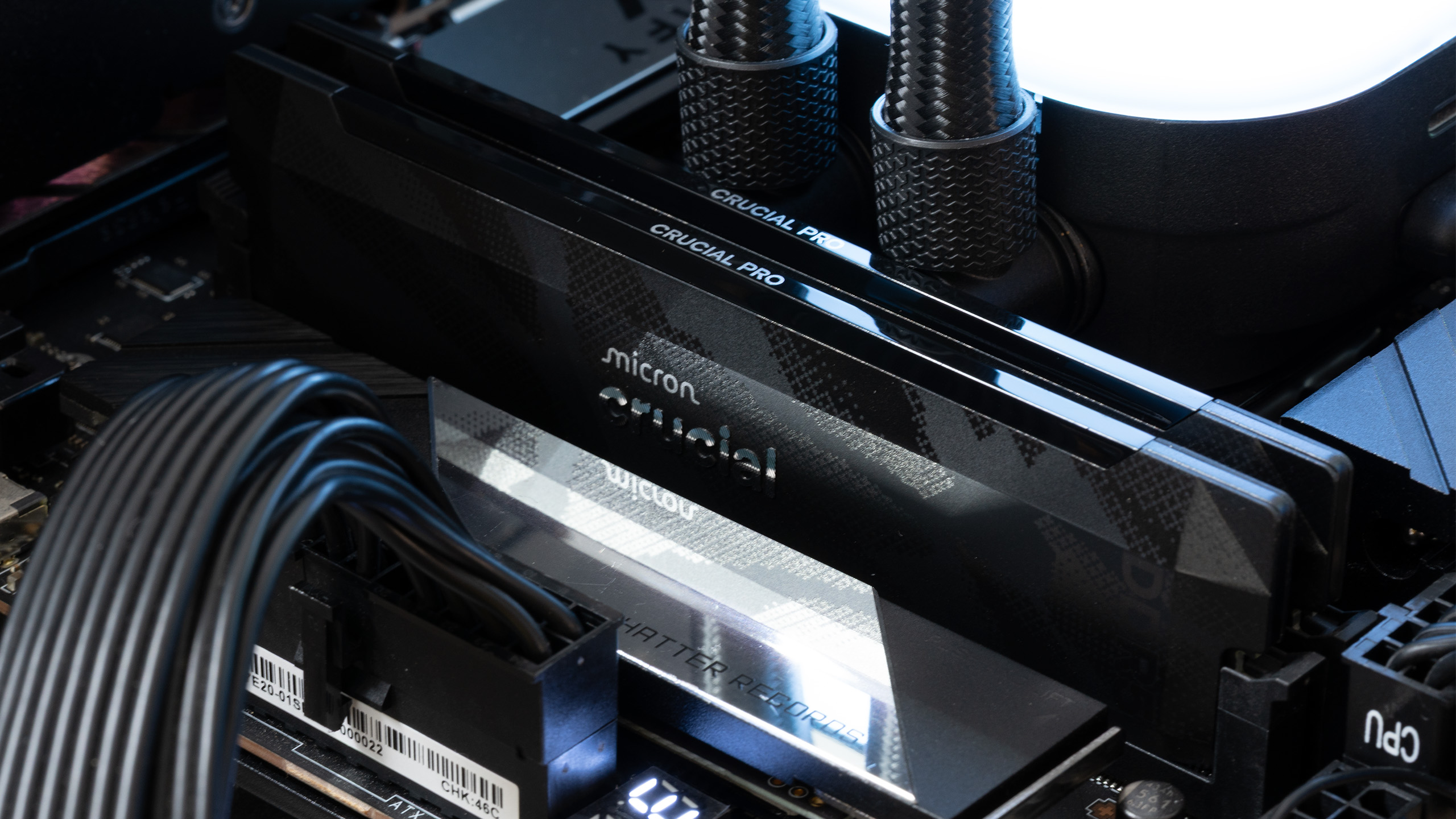

The Crucial brand wasn't just a product line. It was Micron's most direct connection to the consumer market. Crucial SSDs and RAM modules were found in budget gaming builds, enthusiast systems, and mainstream laptops. For DIY builders with limited budgets, Crucial was the reliable option that didn't cost as much as Samsung but didn't skimp on quality.

Killing it was genuinely significant. It meant Micron was willing to sacrifice brand loyalty and market presence in exchange for production focus and margin optimization.

Micron's official narrative is that Crucial is being retired but consumers will still be served through OEM channels and partnerships. Moore emphasized that major PC manufacturers like Dell and Asus will continue receiving memory and storage modules from Micron. This is technically true, but it misses the real impact on consumer choice and pricing.

When consumers buy a Dell or Asus laptop, they don't choose the exact memory specification. The OEM does. They negotiate volume pricing with suppliers and build memory according to their own specifications. The individual consumer has zero leverage. If Micron is supplying Dell, Micron sets the price, and Dell passes it along.

But DIY builders have agency. They shop for price, they compare specs, they wait for sales. When Crucial was available as a retail SKU, it created competitive pressure on pricing across the entire consumer segment. Samsung and Kingston had to stay competitive. Retailers had to maintain selection.

With Crucial gone and production shifted to enterprise, that competitive pressure evaporates. DIY builders are left choosing between premium brands like Corsair and G. Skill, or lower-tier brands with weaker reliability track records. The middle ground—solid performance, reliable brand, competitive pricing—is shrinking.

Production Capacity: The 2028 Promise

Micron is investing heavily in future capacity. The company is building a new facility in Boise, Idaho (the ID1 fab) and has announced plans for a massive $100 billion megafab in New York. On paper, this should solve the supply problem. In reality, it won't help anyone for years.

Here's why: semiconductor fabs take forever to build and qualify. The Idaho facility was announced years ago and still hasn't reached full production. The New York megafab is even further from reality. Moore himself acknowledged that meaningful production from these facilities won't materialize until 2028 at the earliest. That's three years away. For an industry moving at current speeds, three years is an eternity.

Between now and 2028, Micron will be running its existing fabs at maximum capacity, optimized for enterprise revenue. Consumer supply will be constrained. Prices will stay elevated. The situation will likely get worse before it gets better.

There's also a complicating factor: by the time these new fabs come online in 2028, the market may have shifted again. AI workloads might become more memory-efficient. New architectures might reduce memory requirements. Competing suppliers might have expanded their own capacity. The demand that justifies this investment today might be partially satisfied by other manufacturers two years from now.

So Micron's investment in future capacity is hedging against uncertainty. But for consumers dealing with elevated prices in 2025, 2026, and 2027, these future promises feel hollow.

The Qualification Bottleneck

There's another constraint most people don't consider: customer acceptance and qualification. Before Micron can sell a new memory product to enterprise customers, those customers need to test it, certify it, and integrate it into their systems. This process can take months or even years.

Data centers can't just plug in new memory and hope for the best. They need reliability testing, compatibility verification, and integration with their existing infrastructure. A single bad batch of memory can knock a data center offline, costing millions in lost revenue. So customers are conservative about adopting new products.

Micron will have to go through this qualification process with their major enterprise customers before production ramps up. That adds another 12-18 months of buffer time before the new fabs contribute meaningfully to supply.

The Adjustment Cost for Consumers

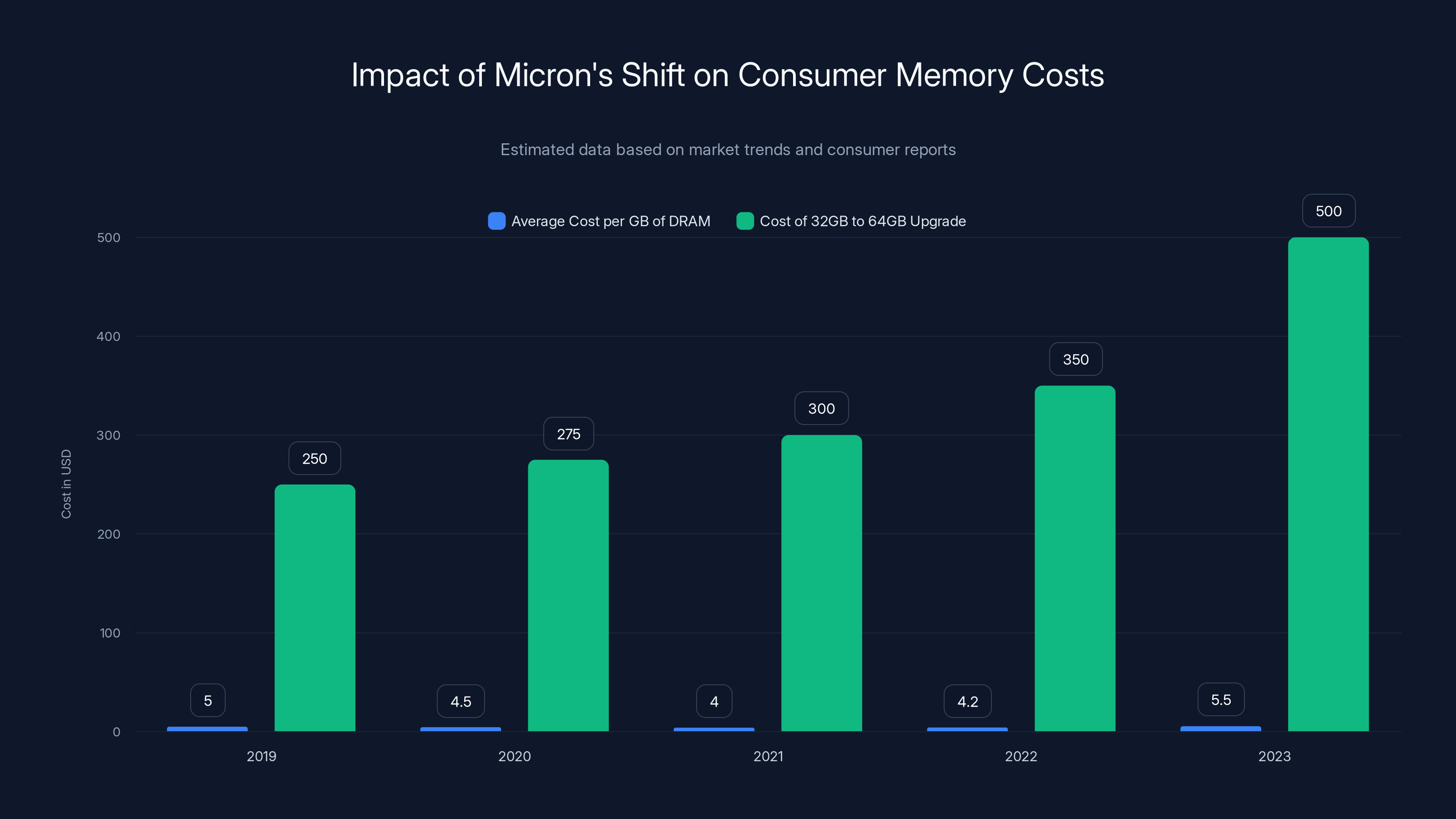

Micron's pivot has tangible costs for consumers, and they're worth quantifying. First, there's the direct price impact. Enterprise memory commands premium pricing because it requires higher reliability standards, better thermal management, and custom qualification. When a larger portion of total supply goes to enterprise, the average price of all memory goes up.

Second, there's the product selection problem. Consumers used to have dozens of options at each price point. Now that pool is shrinking. Budget options are disappearing. The enthusiast tier is consolidating around fewer brands. Choice is collapsing.

Third, there's the upgrade penalty for older systems. If you built a PC three years ago and want to upgrade from 16GB to 32GB, you're now facing new hardware constraints. The exact same memory type that was cheap in 2022 is now rare or unavailable. You might be forced to upgrade an entire system when you only wanted to upgrade memory.

For laptop buyers, the situation is slightly better because OEMs absorbed some of the shock through volume partnerships. But even OEMs are feeling pressure. A typical laptop that cost

For content creators and gamers who need high-capacity memory systems (64GB, 128GB), the situation is worse. Premium memory brands are the only option, and prices are steep. A professional upgrading from 32GB to 64GB might spend

Memory prices vary significantly by region, with the United States and Western Europe having more stable and lower prices compared to India and emerging markets. (Estimated data)

Industry-Wide Dynamics: It's Not Just Micron

Before you blame Micron entirely, understand that this shift is industry-wide. Samsung, SK Hynix, Kioxia, and Intel (through its partnership with SK Hynix) are all making similar strategic choices. Every major memory supplier is prioritizing enterprise and data center segments.

This isn't a conspiracy. It's simple economics. When demand for a product exceeds supply by a huge margin, price-insensitive buyers (data centers with billion-dollar infrastructure budgets) will outbid price-sensitive buyers (individual consumers and small businesses) every single time.

Data centers are literally willing to pay whatever it costs to get the memory they need. They can't operate without it. A $10 difference in memory cost per server is noise compared to the value of having servers operational and generating revenue.

Consumers, by contrast, can postpone upgrades. They can buy less memory than they want. They can switch to older hardware. They have flexibility that enterprises don't have. So from an economic perspective, it makes sense to serve the inflexible, high-paying customers first and let consumers get whatever's left.

China and other emerging manufacturers have been trying to build capacity to serve consumer segments, but they're years behind on technology and process node. By the time they can produce competitive memory, the market conditions might have shifted again.

So Micron's pivot is rational, predictable, and happening across the entire industry. The real question is: how do consumers adapt?

OEM Partnerships: The Hidden Advantage

Micron's claim that consumers are still being served through OEM partnerships is technically accurate but strategically important. When you buy a pre-built Dell, Asus, Lenovo, or HP system, you're getting memory that Micron negotiated specifically for that OEM.

These partnerships create interesting market segmentation. OEMs get priority access to supply in exchange for volume commitments and long-term purchasing agreements. Individual consumers get squeezed in between.

But OEM partnerships also mean you're limited in your choices. You can't configure unlimited memory, pick specific brands, or optimize for your exact use case. You get what the OEM decided to include, with limited upgrade options.

This creates an opportunity for manufacturers like Dell and Asus. They can market their systems as being optimized for memory performance and availability, while DIY builders face constraints. It subtly shifts purchasing decisions toward pre-built systems and away from custom builds.

DRAM Type Specialization and Capacity Constraints

There's a technical detail that exacerbates consumer supply constraints: different DRAM types require different production processes and equipment.

Consumer DRAM typically comes in standard densities like 4GB, 8GB, 16GB, and 32GB modules. Enterprise DRAM might come in 64GB, 128GB, or higher capacity modules designed for server applications. A manufacturing line optimized for enterprise density produces very different volumes than one optimized for consumer modules.

When Micron adjusted production to emphasize enterprise, they shifted their equipment and process parameters to favor high-capacity modules. This reduced their ability to produce standard consumer capacities efficiently.

Moore acknowledged this directly: "Adjusting production for different DRAM sizes can reduce overall output." What this means in plain English: if Micron wants to produce 64GB enterprise modules, they can't also efficiently produce 16GB consumer modules on the same line. They have to choose.

Given that enterprise modules generate more revenue per unit, the choice is obvious. Consumer modules get squeezed out not because of conspiracy, but because of manufacturing reality.

This is why Crucial retirement makes financial sense. Maintaining a diverse consumer product line across multiple capacity points requires production complexity. Simplifying to high-capacity enterprise products reduces complexity and increases per-unit revenue.

The average cost per gigabyte of DRAM has increased significantly since Micron's shift, impacting consumers with higher upgrade costs. Estimated data based on market trends.

The Pricing Outlook Through 2028

Let's be honest about what's coming: DRAM prices are staying elevated for years.

Micron's own timeline—meaningful new production by 2028—suggests that consumer constraints will persist through 2027. But there's no guarantee prices will drop even after new capacity comes online. Here's why:

First, enterprise demand for AI infrastructure is still growing. New data centers are being built constantly. Existing data centers are expanding. The demand isn't peaking—it's still accelerating. So even with new capacity, enterprise will probably absorb most of it.

Second, memory manufacturers have learned to enjoy higher prices. Profit margins in the memory business are better with elevated pricing than they were in the old competitive environment. Once companies get used to higher margins, they're reluctant to compete them away. Prices might stabilize at current levels even after supply increases.

Third, there's always geopolitical risk. Supply chain disruptions, trade restrictions, or manufacturing incidents can reduce supply unpredictably. These risks create a permanent risk premium on memory pricing.

For consumers, the practical implication is this: budget for elevated memory costs through 2027 and maybe beyond. If you're planning a significant PC upgrade or system build, it's worth doing sooner rather than later, assuming you have the budget. Waiting for prices to drop probably means waiting indefinitely.

DIY Builder Market: Adaptation and Alternatives

DIY PC builders are being forced to adapt to a fundamentally different market. You can't build a system the way you did five years ago. The market has changed. Supply has changed. Pricing has changed.

Here's what's actually available right now:

Premium Brands (Higher Prices, Better Availability): Corsair, G. Skill, Kingston, and Samsung still have consumer product lines and maintain reasonable availability. They're not getting the same allocation as enterprise suppliers, but they're producing for the DIY market. Expect to pay 15-25% premiums over historical pricing.

Smaller Brands (Budget Pricing, Uncertain Quality): Brands like Patriot, Teamgroup, and PNY fill the budget segment. They're cheaper, but quality variance is higher. You might get a reliable product or you might get something that fails after two years.

Gray Market and Liquidation Stock: Occasionally, liquidated data center inventory or overstock from regional markets appears on the secondhand market at discounted prices. These are usually reliable (data center equipment is robust) but lack warranty coverage and might have limited lifespan remaining.

None of these options is ideal. All require compromise compared to the Crucial option that used to exist—reliable brand, competitive pricing, good availability.

Enterprise Priorities: Why Data Centers Always Win

Understanding why enterprise always wins in supply crunches requires understanding the economics of data center operations.

A hyperscale data center (the kind that runs cloud services, AI models, or streaming platforms) might have a capital investment of

When a data center needs memory to stay operational, it's not a luxury—it's a necessity worth unlimited spending. If memory costs increase 50%, the data center pays it. The data center operator will literally never be price-sensitive in the way a consumer is.

Consumers, by contrast, have flexibility. You can postpone a PC upgrade. You can buy less memory than you want. You can live with slower performance. You have options.

From an economics and game theory perspective, suppliers should absolutely prioritize the inflexible, high-value customers (data centers) over the flexible, price-sensitive customers (consumers). That's just rational behavior.

Micron, Samsung, and every other memory supplier is simply being economically rational. They're serving the customers who are willing to pay the most and have the least flexibility. That's called capitalism.

For consumers, this is frustrating but ultimately not surprising. We're experiencing the natural outcome of AI infrastructure being more valuable than consumer computing.

Enterprise DRAM consumption has increased significantly from 35% in 2018 to an estimated 55% in 2023, driven by AI and large language models. Estimated data based on trends.

Laptop Market Impact: OEM Insulation vs. DIY Exposure

Laptop buyers have better insulation from these supply constraints than desktop builders because OEMs negotiate volume allocations. If you're buying a Dell or Lenovo laptop, you're probably getting reasonable memory specs because Dell has contracts in place.

But this insulation comes with costs. You can't upgrade memory in most modern laptops without buying a new system or paying for expensive professional service. You're locked into whatever the OEM decided at purchase time.

Five years ago, you could buy a laptop with 8GB and upgrade to 16GB later for $100. That upgrade path is mostly closed now. Soldered memory is the default on everything except high-end workstations.

So consumers face a dilemma: accept memory limitations in exchange for lower upfront cost, or pay for a fully-configured system from the start. The middle ground—good specs, upgradeability, and reasonable cost—is vanishing.

For content creators, video editors, and professionals, this is particularly painful. Professional work demands more memory, but professional laptops are expensive. And by the time you get enough memory configured in, the price is punishing.

Gaming and High-Performance Computing Segments

Gamers are experiencing this supply crunch acutely because gaming systems need high-capacity memory setups, and gaming-focused memory brands are not insulated from enterprise competition.

A typical gaming system from five years ago had 16GB of memory. A modern gaming system needs 32GB minimum, often 64GB for content creators who also game. That's 4x the memory for the same performance tier.

Memory brands that target gamers—Corsair, G. Skill, Kingston—are all feeling enterprise pressure. They're allocating some production to gaming, some to enterprise, and trying to maximize revenue. Gaming memory gets features like RGB lighting and custom cooling, which adds cost and reduces margins compared to enterprise modules.

Gaming communities have been hit particularly hard by Crucial's retirement because Crucial memory was often the best price-to-performance option. Without that option, gamers are choosing between premium gaming brands (Corsair, G. Skill) at high prices or non-gaming brands with fewer features.

Content Creation and Professional Workflows

Content creators—video editors, 3D artists, photographers, data analysts—are getting squeezed from both directions: enterprise is consuming memory they need, and consumer options are shrinking.

A professional video editing workstation needs 64GB minimum. 3D rendering systems often need 128GB or more. These aren't gaming rigs. These are production equipment where memory is central to workflow efficiency.

Memory costs directly impact the economic viability of freelance creative work. If memory costs are elevated, a freelancer needs to charge more for projects to maintain margins. That makes them less competitive. It's a real economic headwind.

Some studios are responding by moving to cloud-based workflows where memory infrastructure is hosted by AWS, Google Cloud, or similar providers. This offloads the hardware cost problem but creates new dependencies and latency issues.

For independent creatives, the options are worse. You can't efficiently move professional content creation to the cloud because of bandwidth and latency constraints. You need local hardware. And local hardware is expensive right now.

This is subtle but important: elevated memory costs are quietly changing the economics of creative work, shifting advantages toward studios and companies that can absorb hardware costs, and disadvantaging individuals and small teams.

Enterprise now accounts for approximately 55% of global memory supply, overshadowing the consumer market. Estimated data based on industry trends.

Geographic Variations and Regional Supply Chains

Memory supply is not evenly distributed globally. Some regions experience tighter constraints than others based on local OEM demand and regional manufacturing capacity.

North America and Western Europe have relatively stable supply through major OEMs like Dell, HP, and local system integrators. Parts of Asia experience different constraints based on regional demand patterns. Emerging markets sometimes face severe shortages because they're lower priority for manufacturers.

This creates arbitrage opportunities and complicates pricing comparisons. Memory that costs

For most consumers, this geographic complexity is invisible. But it underlies why global memory pricing isn't perfectly synchronized and why supply improvements might happen at different rates in different regions.

Manufacturers like Micron operate globally but optimize locally. They'll prioritize supply to regions that generate the most revenue, which generally means North America and Western Europe before Asia-Pacific.

Competitive Dynamics: Samsung, SK Hynix, and Others

Micron isn't the only major memory supplier, though it's one of the big three. Samsung and SK Hynix are also reshaping their portfolios.

Samsung has been investing heavily in both consumer and enterprise segments but is also prioritizing high-end enterprise memory. SK Hynix, which is deeply embedded in Chinese and Korean manufacturing, is also shifting toward enterprise but with different regional priorities.

Kioxia (formerly Toshiba Memory) produces NAND flash memory primarily, which is used in SSDs, but has different dynamics than DRAM.

Intel exited the standalone memory business but maintains partnerships with SK Hynix for specialized products.

The competitive landscape is complex. No single supplier dominates DRAM, but the top three (Micron, Samsung, SK Hynix) control about 95% of the global market. When all three shift strategy simultaneously, the entire market shifts.

There's no competitive counterweight. Smaller suppliers or potential entrants don't have the resources to build capacity quickly enough to serve emerging demand.

Alternative Technologies and Emerging Solutions

As memory constraints tighten, alternative technologies are getting more attention.

Hybrid Storage-Memory Systems: Some workloads are moving toward architectures that use fast NVMe SSDs as extended memory, swapping data between DRAM and SSD as needed. This is slower than pure DRAM but reduces peak memory requirements. It's not ideal for all workloads, but it's viable for some data center scenarios.

Emerging Memory Types: Research into Phase Change Memory (PCM), Resistive RAM (Re RAM), and other next-generation memory technologies is accelerating. These could eventually provide alternatives to DRAM. But we're probably 5-10 years away from commercial viability at scale.

Software Optimization: Some workloads are being rewritten to use less memory through more efficient algorithms and data structures. This is always beneficial, but there are limits to how much you can optimize. You can't create memory out of nothing.

Cloud Migration: More workloads are moving to cloud infrastructure where hardware constraints are someone else's problem. AWS, Google Cloud, and Azure manage their own memory supply chains and can absorb costs more efficiently than individual enterprises.

None of these are silver bullets. But collectively, they're reducing demand pressure slightly and creating alternative paths forward.

Timeline: What to Expect Year by Year

Let's map out the realistic timeline for memory market evolution.

2025 (Now): Enterprise demand remains high. Consumer supply remains tight. Prices stay elevated. Crucial brand is fully phased out. Pre-built systems have better availability than DIY components.

2026: Enterprise AI deployments continue accelerating. No meaningful new capacity comes online. Consumer alternatives (Corsair, G. Skill) develop stronger positions in budget and gaming segments. Price pressure moderates slightly as demand growth slows slightly, but prices don't drop significantly.

2027: Micron's Idaho facility reaches higher production levels (though not full capacity). First signs of supply stabilization appear in enterprise segment. Consumer segment still constrained but less severely. Prices stabilize at current levels rather than continuing to increase.

2028 and Beyond: Micron's new facilities begin meaningful production. Market normalizes gradually. Prices may decline slightly as competition increases, but expect new equilibrium to be higher than pre-2023 levels. Enterprise permanently maintains larger share of production capacity.

This isn't speculation. This is based on publicly disclosed timelines and industry patterns.

Strategic Responses: What Companies and Consumers Can Do

Given this outlook, what are the smart moves?

For Consumers Planning Upgrades:

- Do it sooner rather than later if you have the budget

- Buy pre-built systems from OEMs if you need a new computer (better supply access)

- Consider premium memory brands that maintain inventory (Corsair, G. Skill)

- Avoid waiting for prices to drop—they probably won't

- Budget 25-30% more for memory than you would have two years ago

For Content Creators and Professionals:

- Consider cloud-based workflows where applicable to offload hardware costs

- Evaluate studio versus independent work economics given elevated hardware costs

- Invest in optimization—less memory usage through better software is now a competitive advantage

- Build redundancy into systems since memory is expensive

For Small Businesses:

- Lock in volume agreements with suppliers now if possible

- Evaluate cloud migration versus capital investment in local hardware

- Plan hardware refreshes carefully since upgrade costs are higher

For DIY Enthusiasts:

- Accept that the community-driven DRAM market you knew is changing

- Build systems now if you've been planning to

- Join online communities sharing alternative sources and deals

- Don't expect nostalgia-driven solutions—companies are optimizing for profit, not for user preference

The Broader Implications: What This Reveals About Tech Industry Priorities

Micron's strategy reveals something fundamental about the tech industry's current priorities. Enterprise infrastructure for AI is now worth more than consumer computing. This isn't controversial—it's economically rational.

But it has implications. It means the innovation cycle is optimizing for data center efficiency, not consumer experience. It means manufacturers will continue to shift resources toward enterprise. It means consumer computing might see a period of stagnation while enterprise racing forward.

For individuals who just want a reliable upgrade path for their personal computers, this is frustrating. You're not the target customer anymore. You're the residual demand that gets served with whatever capacity remains.

That's not malice. It's just economics. Enterprise data centers are where the profit is, so that's where manufacturers focus.

Understanding this helps you make better decisions. Stop expecting memory prices to normalize quickly. Stop waiting for ideal upgrade windows. Make decisions based on current availability and cost, not future promises.

The memory market of 2025 is different than the memory market of 2015. It's more concentrated on enterprise. It's less consumer-focused. And it's going to stay that way for years.

FAQ

Why did Micron retire the Crucial brand?

Micron retired Crucial to simplify production and focus resources on higher-margin enterprise memory. The consumer DRAM and SSD market requires competing on price and maintaining diverse product portfolios across different capacities. Enterprise memory generates more revenue per unit and allows Micron to optimize manufacturing around fewer product types. With enterprise demand consuming 50-60% of global memory supply and data centers willing to pay premium prices, the business case for maintaining a consumer brand became weak.

Will Crucial memory ever come back?

It's unlikely in the near term. Micron's strategic pivot is focused on enterprise for at least the next 3-5 years. After 2028, when new manufacturing capacity comes online, Micron might reconsider consumer segments, but there's no public indication this is planned. Once brand infrastructure is dismantled, rebuilding it requires significant investment in marketing and channel relationships. It's easier for Micron to serve consumers through OEM partnerships than to rebuild an independent consumer brand.

When will memory prices drop?

Don't expect significant price reductions until 2028-2029 at the earliest, and even then, drops might be modest. Enterprise demand for AI infrastructure is still accelerating and will likely absorb most new capacity. Memory manufacturers have also learned to accept higher margins at current price points. Price stability is more likely than significant declines. If you're waiting for a "crash" in memory pricing similar to past cycles, you'll probably be disappointed.

Is it better to buy a pre-built computer or build my own right now?

Pre-built systems from major OEMs (Dell, HP, Lenovo, Asus) have better memory supply access through volume agreements and might offer better value than DIY builds when accounting for component prices. However, you sacrifice customization and upgradeability. If you want specific features or plan to upgrade later, DIY is still viable but expect higher memory costs. The decision depends on your specific needs and how much you value customization versus cost and availability.

What memory brands should I buy if Crucial isn't available?

Corsair, G. Skill, Kingston, and Samsung maintain strong consumer product lines and have reasonable retail availability. They're more expensive than Crucial was, but they offer reliability and warranty coverage. Budget brands like Patriot and PNY are cheaper but have higher quality variance. For gaming or professional work, Corsair and G. Skill dominate. For general-purpose upgrades, Kingston offers good middle-ground pricing and reliability.

How will this affect laptop upgrades?

Most modern laptops use soldered memory that can't be upgraded by users, so the memory market shift affects laptop buyers at purchase time, not later through upgrades. OEMs have secured memory supply through volume agreements, so new laptops generally have adequate specs. However, if you need to buy a laptop with higher memory configuration to future-proof it, you'll pay premium prices. The upgrade-later strategy that worked five years ago is no longer viable for most systems.

Is the enterprise AI demand really that large?

Yes. A single data center running advanced language models can consume terabytes of memory. When a company like Meta or Google is building dozens of such facilities, the total memory consumption exceeds entire regional PC markets. This shift from consumer-focused memory markets to enterprise-focused markets is real, measurable, and unprecedented in the industry.

What about memory for gaming systems?

Gaming system memory requirements have doubled (from 16GB to 32GB standard) in the past five years, exactly when supply has tightened. Gaming memory brands like Corsair and G. Skill are available but expensive. RGB lighting and custom cooling add cost. If you're building a gaming system now, budget

Will other manufacturers fill the gap Micron left?

Partially, but not quickly. Samsung and SK Hynix have similar enterprise priorities and aren't focused on consumer segments either. Smaller manufacturers or potential new entrants lack the capital and technology to build capacity at scale quickly. The industry structure means Micron's exit from consumer focus likely signals a long-term shift, not a temporary phase. Competition from other manufacturers will happen gradually over years, not months.

Should I buy extra memory now as a hedge against future price increases?

If you have budget available and confidence you'll use the memory, yes. Supply constraints are likely to persist through 2027, and prices are more likely to stay flat or increase slightly than to decrease. Buying quality memory now and putting it in long-term storage is a reasonable hedge given the market outlook. Just ensure you understand the compatibility requirements for your specific system before purchasing.

Conclusion: Accepting the New Reality

Micron's strategic pivot from consumer memory to enterprise AI infrastructure is one of the most significant shifts in the PC market in years. It's not unique to Micron—it's happening across the entire memory industry. And it's reshaping what consumers can reasonably expect from memory pricing and availability for years to come.

The simple version of the story is this: AI infrastructure is more valuable than personal computers right now, so manufacturers are optimizing for AI infrastructure. Data centers will pay whatever it costs, while consumers have flexibility and can postpone upgrades. From a business perspective, serving data centers makes sense.

For consumers, this means accepting some hard truths. DRAM prices are staying elevated through at least 2027. Consumer product options are shrinking. Supply will remain tight. The upgrade paths that used to exist are disappearing as manufacturers consolidate around enterprise priorities.

But it's not all doom. Pre-built systems remain relatively available because OEMs negotiated volume supply agreements. Memory from quality brands like Corsair and G. Skill is still available at retail, even if it's expensive. Used or refurbished enterprise memory is entering the market as a budget option. These aren't ideal substitutes for what Crucial offered, but they're available.

The key is accepting the new market reality and making decisions accordingly. Stop waiting for prices to drop. Stop expecting Crucial to return. Stop banking on supply normalizing quickly.

Instead, make upgrades when you need them, not when you wish you could. Choose pre-built systems if you need flexibility. Accept that premium brands are now the default option. Budget for higher memory costs. Understand that enterprise will remain the priority for several more years.

Micron and other manufacturers aren't being malicious. They're being rational. They're following profit incentives where they lead. That's capitalism in action. And it means the memory market of 2025 and beyond will look fundamentally different than it did five years ago.

The consumer PC market didn't disappear. It just became less important than AI infrastructure. Living in a world where that's the economic reality is going to require different expectations and different strategies.

For anyone building or upgrading a computer in 2025, that's the context you're working in. And understanding it might be the most valuable information you can have.

Key Takeaways

- Enterprise DRAM now consumes 50-60% of global memory supply, fundamentally restructuring how manufacturers allocate production capacity away from consumers

- Micron's Crucial brand retirement signals a permanent shift toward high-margin enterprise segments, not a temporary supply constraint

- New manufacturing capacity won't materialize meaningfully until 2028, extending consumer supply constraints and elevated prices for at least three more years

- Pre-built systems from major OEMs have better supply access than DIY components, making custom builds less economical in the current market

- Memory prices are likely to stabilize at current elevated levels rather than decrease, requiring consumers to adjust budgets and purchasing strategies permanently

Related Articles

- Taiwan's $250B US Semiconductor Investment: What It Means [2026]

- Trump's 25% Advanced Chip Tariff: Impact on Tech Giants and AI [2025]

- RAM Price Hikes & Global Memory Shortage [2025]

- China's Technological Dominance: The Chinese Century Explained [2025]

- The End of Cheap Phones: Why Prices Are Rising 30% in 2025

- PC Sales Downturn 2026: Why Memory Prices Are Skyrocketing [2025]

![Micron's AI Memory Pivot: What It Means for Consumers and PC Builders [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/micron-s-ai-memory-pivot-what-it-means-for-consumers-and-pc-/image-1-1768511335460.jpg)