Taiwan's $250 Billion Semiconductor Trade Deal: How It Reshapes Manufacturing and Global Supply Chains [2025]

In early 2025, the US and Taiwan finalized a trade agreement that will fundamentally reshape how semiconductors get made, where they're produced, and who controls the most critical piece of modern technology infrastructure. The deal is big. We're talking

But here's the thing: this isn't just about making more chips in America. It's a geopolitical chess move wrapped in economic policy, a response to years of supply chain chaos, and a recognition that whoever controls semiconductor production controls the future.

Let me break down what just happened, why it matters, and what comes next.

TL; DR

- $250 billion upfront investment from Taiwanese companies into US semiconductor production capacity

- $250 billion in government credit guarantees from Taiwan supporting the semiconductor industry and supply chain

- Tariff deal: Reciprocal tariffs cut from 20% to 15%, with exemptions for pharmaceuticals, aircraft, and critical materials

- TSMC already positioned: Taiwan's largest chipmaker commits additional expansion in Arizona

- The incentive: Build in America or face 100% tariffs—that's the message from US Commerce Secretary

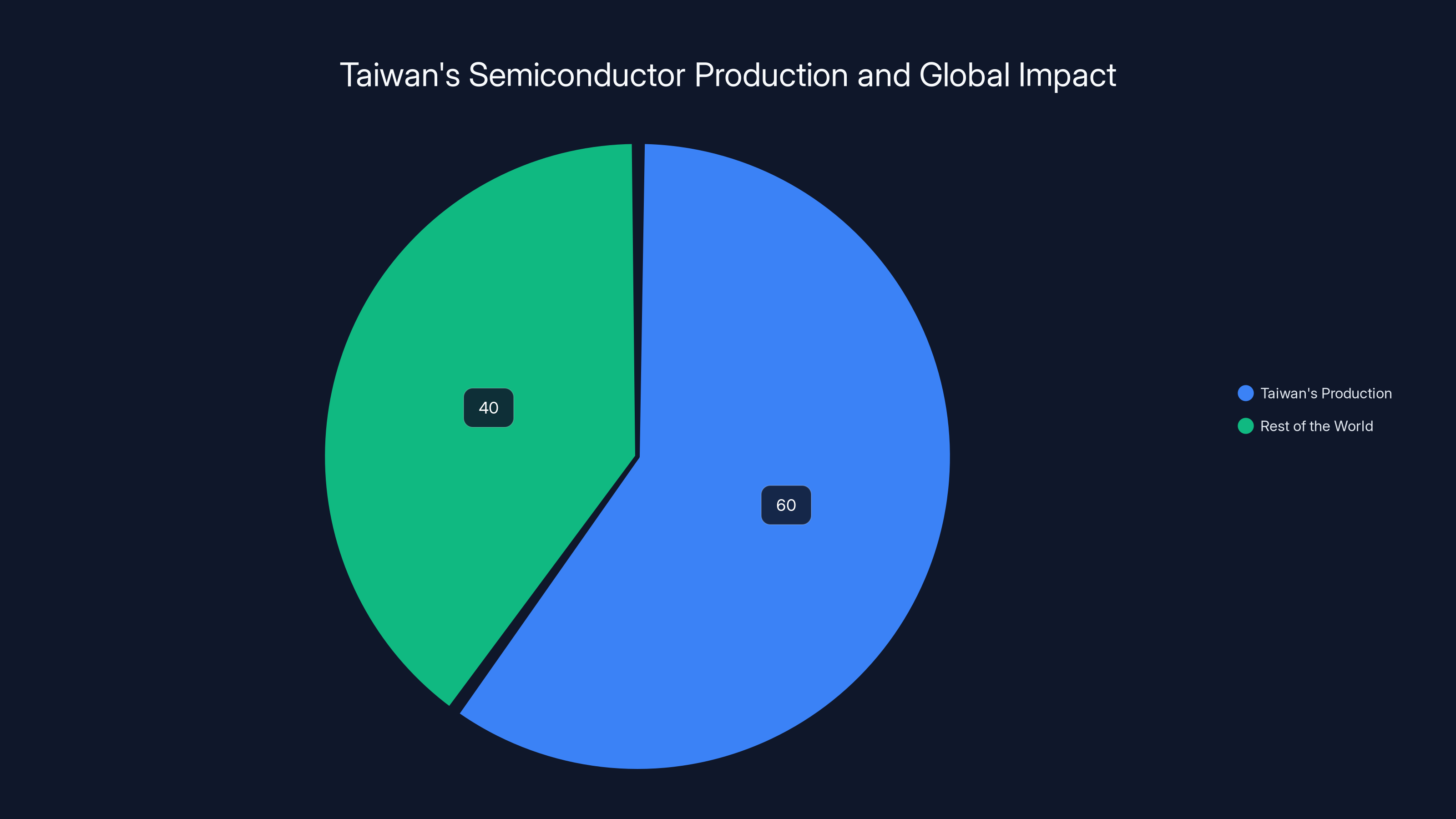

- Bottom Line: The US is making a play to onshore 40% of Taiwan's semiconductor supply chain within the next decade

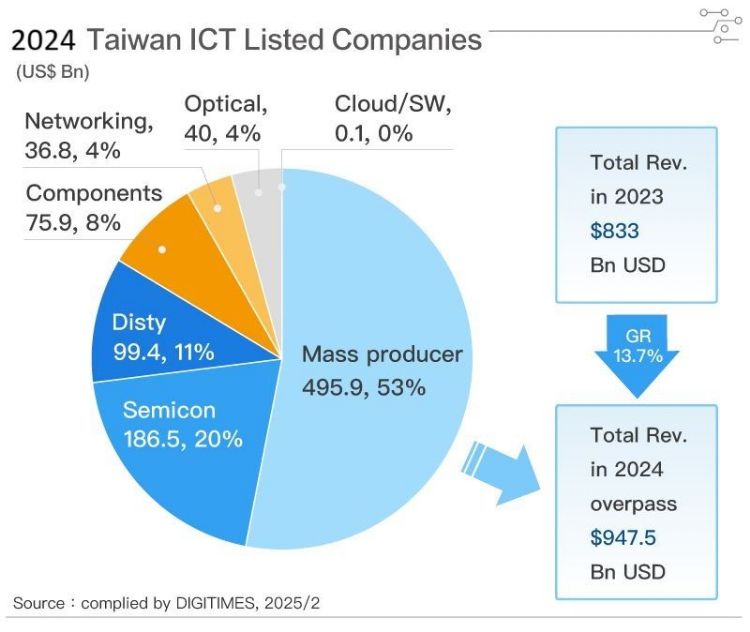

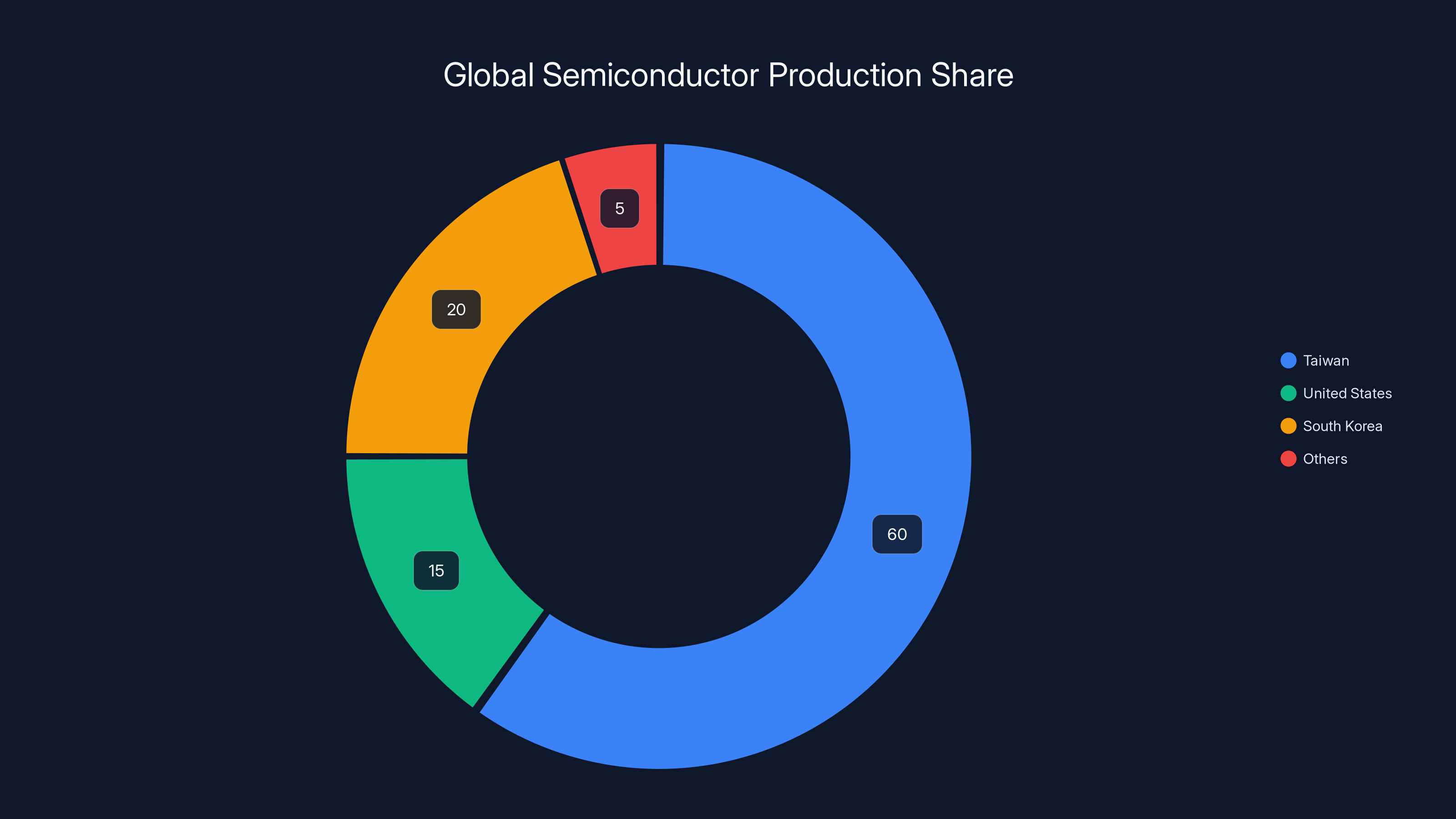

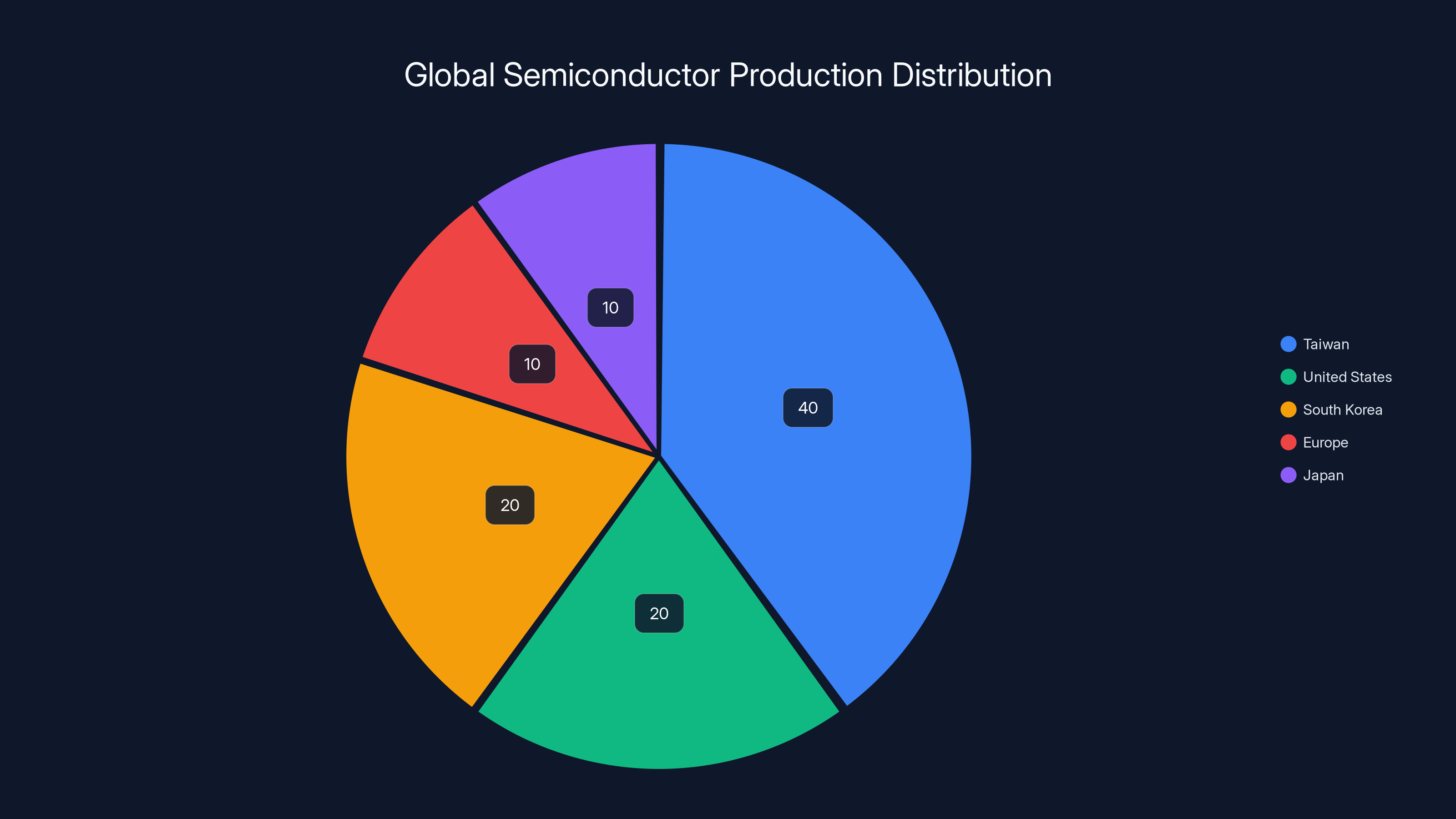

Taiwan currently produces over 60% of the world's advanced chips. The US aims to increase its share through new investments and partnerships, potentially shifting the balance over time. Estimated data.

Understanding the Core Deal: What Taiwan and the US Actually Agreed To

When government officials announce a "$250 billion trade deal," most people's eyes glaze over. Let's make this concrete.

The agreement between the US Department of Commerce and Taiwanese businesses isn't some vague handshake. It's structured around hard commitments:

Taiwanese companies pledge at least $250 billion in direct capital investment into US semiconductor production facilities. This isn't money that flows to the government or funds education initiatives. This is money building fabs, hiring workers, establishing supply chains, and creating infrastructure.

Taiwan's government adds another $250 billion in credit guarantees. Think of this as backup financing. If a Taiwanese semiconductor company wants to expand in Arizona or Ohio, Taiwan's government is essentially saying, "We'll guarantee the loan so you can borrow at better rates." This dramatically reduces financial risk for companies making massive bets on US operations.

In return, Taiwanese businesses get a better tariff deal. Previously, reciprocal tariffs sat at 20%. Under the new agreement, they drop to 15%. That might sound like a small difference—it's not. For a company moving billions into US factories, every percentage point matters on margins.

But there's a carve-out clause that reveals what Washington really cares about. Generic pharmaceuticals, aircraft components, and certain unavailable natural resources get exempted entirely from reciprocal tariffs. Translation: "We want you to bring chip manufacturing, not everything else."

There's also the Section 232 framework adjustment. Taiwanese companies with US production facilities can import larger amounts of components without triggering duties. This matters because modern chip fabs don't operate in isolation—they need constant imports of specialized materials, precision equipment, and rare inputs. Removing friction here makes US production more competitive.

Taiwan accounts for an estimated 60% of global semiconductor production, highlighting its critical role in the industry. Estimated data based on industry reports.

Why Taiwan Is Making This Move: The Geopolitical Reality

Taiwan didn't volunteer to pour $500 billion into US semiconductor expansion out of the goodness of corporate hearts. Multiple pressures converged to make this happen.

First, supply chain fragility became impossible to ignore. During the pandemic, semiconductor shortages cascaded through every industry. Automakers shut down assembly lines. Gaming consoles sold out. Data centers couldn't expand. Everyone learned that depending on a single island for 60% of global chip production is precarious.

Taiwan gets it. TSMC, the dominant manufacturer, understood that diversification wasn't optional—it was existential. A Taiwan Strait conflict, a natural disaster, or even aggressive tariffs could cripple them. Operating US facilities insulates them against these risks.

Second, tariff threats became real. The previous US government explicitly discussed tariffs. The current administration is more aggressive. Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick didn't mince words: "If they don't build in America, the tariff's likely to be 100 percent." When faced with a choice between 15% reciprocal tariffs and potential 100% tariffs on all imports, the math is straightforward. Building in the US is the rational move.

Third, market access is the real prize. Chip manufacturing depends on complex supply chains, but demand is concentrated in North America, Europe, and developed Asia. Having production facilities in the US doesn't just mean lower tariffs—it means proximity to customers, faster delivery, and the ability to negotiate with US government agencies (which increasingly prefer domestic sourcing).

Fourth, Taiwan's government sees this as strategic. A stronger US-Taiwan economic relationship means a stronger US commitment to Taiwan's security. Investment in America creates political ties. TSMC becoming embedded in the US economy means the US has a vested interest in Taiwan's stability.

TSMC's Arizona Expansion: The Anchor of the Deal

Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) is the company that makes this deal real. They're not a startup—they're the foundry that produces chips for Apple, Qualcomm, Nvidia, AMD, and basically every major semiconductor design company on Earth.

Back in 2020, TSMC announced a $12 billion investment in Arizona. This was novel at the time. TSMC's entire identity was built around concentration in Taiwan, where they had perfected manufacturing over decades. But they moved anyway.

Now, with this new trade agreement, that Arizona commitment is morphing into something much larger. Reports indicate TSMC is already preparing additional expansions beyond the original $12 billion commitment. The new deal provides the economic framework making this expansion rational.

Why Arizona specifically? A few reasons stand out.

Phoenix has existing tech infrastructure. Intel's major fab presence in the state means experienced engineers, supply chain relationships, and a proven ecosystem for semiconductor manufacturing. TSMC isn't starting from zero.

Water access matters. Chip manufacturing is water-intensive. Arizona's position near the Colorado River and existing water allocation frameworks made it viable. Texas is also emerging as an alternative for future expansions, partly for similar reasons.

Federal incentives layer on top of the tariff deal. The CHIPS Act (the Bipartisan Innovation Law) provided direct subsidies and tax breaks for US semiconductor manufacturing. TSMC's Arizona facilities already qualified for hundreds of millions in federal support. This trade agreement adds another layer of incentives.

Political will is real. Arizona has a long history of tech manufacturing and a state government actively courting advanced industries. The local political environment supports expansion.

Here's the timeline math: TSMC's original Arizona facility was scheduled to come online in 2023. A second facility was planned for 2024-2025. With this new agreement, third and potentially fourth facilities are now being discussed. We're talking about capacity to produce some of the world's most advanced chips (3-nanometer nodes and below) on US soil by 2027-2028.

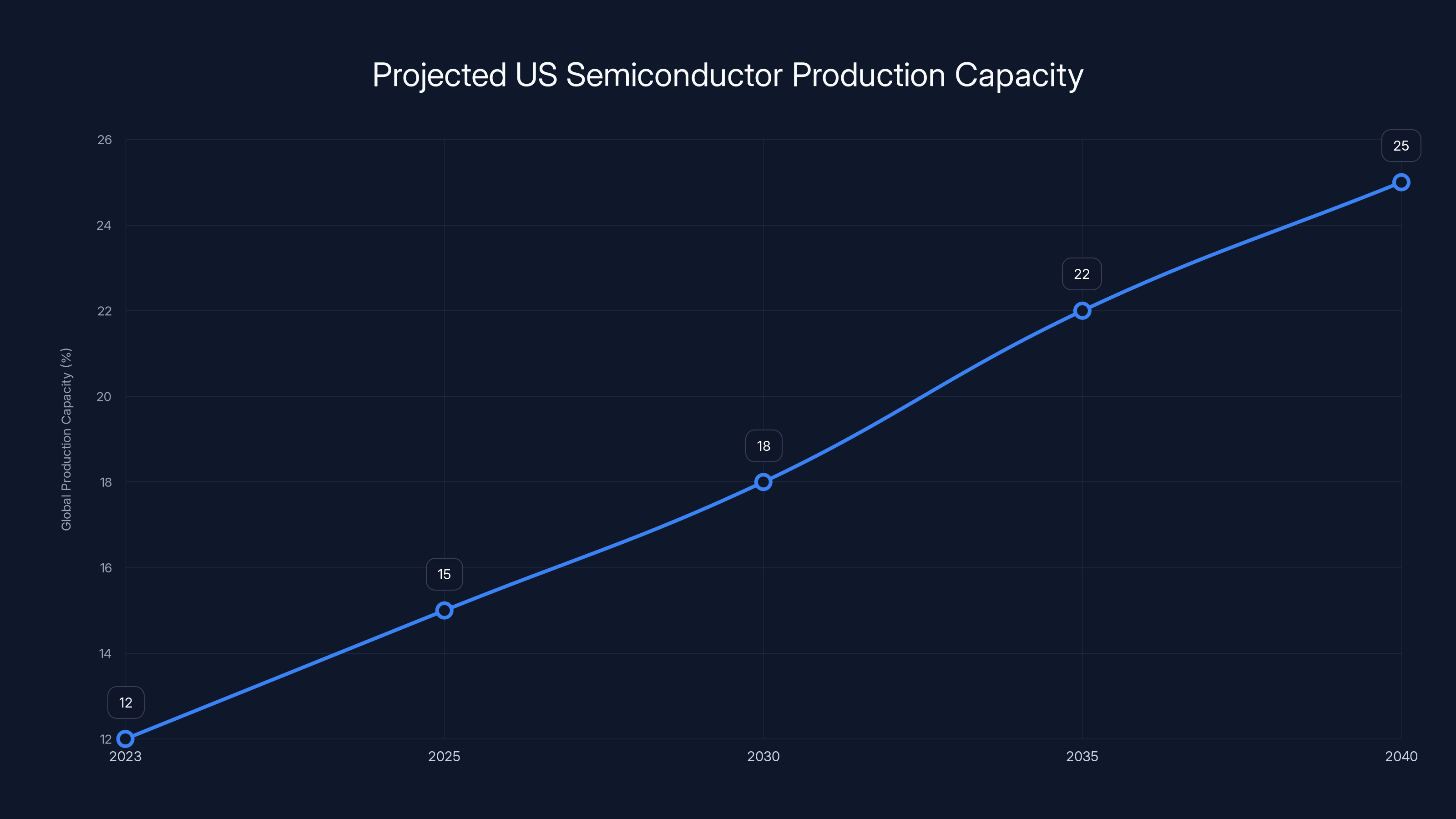

The US is projected to increase its share of global semiconductor production from 12% in 2023 to 25% by 2040, driven by strategic investments and trade deals. Estimated data.

The 40% Onshoring Target: Ambition and Reality

Commerce Secretary Lutnick articulated an explicit goal: the US wants to bring 40% of Taiwan's semiconductor supply chain stateside.

Let's unpack that number, because it's both ambitious and somewhat misleading.

What 40% means: Taiwan's semiconductor supply chain isn't just fabs producing chips. It includes design software, materials suppliers, testing facilities, packaging operations, and logistics. Moving 40% of this ecosystem means not just chip manufacturing, but entire categories of support infrastructure.

Is 40% realistic? The honest answer is: partially. Some pieces will move relatively easily. Advanced chip design has already been partially diversified—companies like Qualcomm (US) and ARM (British, but with strong US presence) do design work globally. Foundry services (the actual manufacturing) are the hard part. TSMC controls maybe 55% of the global foundry market. Moving 40% of Taiwan's foundry capacity to the US would require TSMC expansion plus attracting other players like Samsung or Media Tek to invest in US facilities.

Samsung is already making moves. South Korea's biggest chipmaker has announced US fab investments. Media Tek and other Taiwanese manufacturers haven't committed at the same scale as TSMC, but the tariff incentives could change that.

The timeline matters. Lutnick isn't saying 40% by next year. These projects take 5-7 years from groundbreaking to full production. The 2025-2032 timeframe is realistic for major supply chain shifts.

Why 40% and not 100%? This reveals the real US strategy. Policymakers know you can't move everything. Taiwan's existing ecosystem took decades to build. Climate, geology, labor availability, and supply chain density all favor Taiwan. The US is aiming for enough redundancy to prevent catastrophic supply shocks, not total independence.

How Tariffs Work as Incentives: The Economics of the Squeeze

Understanding tariffs is key to understanding why this deal works.

The baseline scenario (without this deal): A Taiwanese semiconductor company manufactures chips in Taiwan and exports them to the US. Under reciprocal tariff frameworks, these imports face a 20% duty. If the chips cost

The incentive structure: A 20% tariff is painful but not devastating for high-margin products like chips. But the threat goes higher. Lutnick's comment about "100 percent" tariffs is credible. If a company ignores opportunities to invest in US production, subsequent tariff rates could escalate dramatically. This creates a powerful economic incentive to shift operations.

The deal sweetens the pot: With the new agreement, reciprocal tariffs drop to 15%. Now the

Let's do the math on a hypothetical fab expansion:

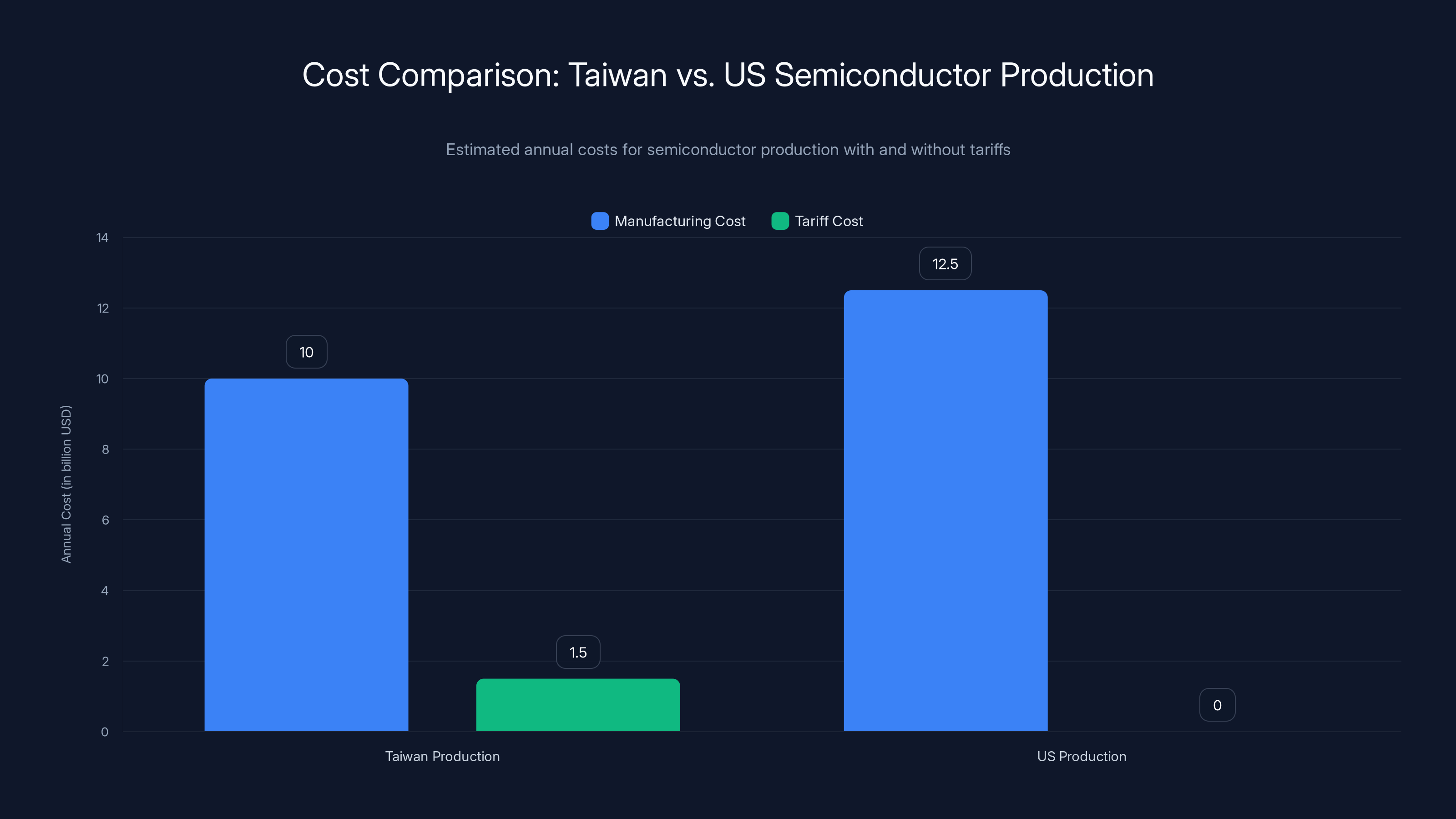

Taiwan-based production:

- Manufacturing cost: $10 billion per year to operate

- Export tariff (15%): $1.5 billion per year

- Total annual cost: $11.5 billion

US-based production:

- Manufacturing cost: $12.5 billion per year (30% higher due to wages, real estate, operational overhead)

- Export tariff: $0

- Total annual cost: $12.5 billion

In this model, even with significantly higher US costs, the tariff elimination makes US production only marginally more expensive. Add in the $250 billion in credit guarantees (reducing financing costs), and US production becomes the rational choice.

The volume effect: This math gets better at scale. TSMC's massive Arizona facility will eventually produce billions of dollars in chips annually. A $1-2 billion annual tariff savings justifies enormous upfront capital investments.

Even with higher manufacturing costs in the US, eliminating tariffs makes US production only slightly more expensive than Taiwan. Estimated data highlights the economic incentive to shift operations.

Supply Chain Resilience: Why Redundancy Became a National Priority

The 2021-2022 semiconductor shortage wasn't just an inconvenience. It was a wake-up call that exposed fundamental vulnerabilities in modern industrial systems.

During the pandemic, chip fabrication didn't stop entirely in Taiwan. TSMC kept running. But demand surged everywhere simultaneously. Everyone wanted work-from-home equipment, gaming consoles, new cars, servers for cloud computing. Supply couldn't meet demand anywhere in the world.

The US automotive industry was particularly hammered. When chip supplies tightened, manufacturers had to halt production lines. General Motors, Ford, and others reported billions in lost revenue because they couldn't source enough semiconductors. This wasn't academic—it was real economic damage.

The national security angle accelerated the response. Defense systems, missile guidance, encrypted communications, and military aircraft all depend on semiconductors. Having Taiwan as the sole source for critical chips created geopolitical risk. If US-Taiwan relations deteriorated, or if military conflict erupted in the Taiwan Strait, the US military could find itself unable to produce next-generation systems.

This drove the CHIPS Act (2022), which provided $52 billion in federal subsidies and tax breaks for domestic semiconductor manufacturing. But subsidies alone don't create capability. You need companies willing to invest, expertise to execute, and sustained commitment. Taiwan's deal changes that equation.

Geographic redundancy reduces systemic risk. If 60% of global chip production concentrates in one island, a single disruption cascades everywhere. A natural disaster, military event, or pandemic lockdown cripples the global economy. With 20-30% of production in the US and another 15-20% in South Korea, and the remainder distributed across Europe and Japan, supply chains become resilient. One disruption doesn't break the system.

The reality is complex though. Even with US production expansion, advanced chips still require materials from other countries. Rare earth elements come from China and Myanmar. Precision equipment comes from Netherlands (ASML makes the crucial lithography machines). Specialty gases and chemicals come from Japan and Germany. True supply chain independence is impossible. But reducing dependency on any single point of failure is achievable.

The Section 232 Import Framework: Reducing Friction for Manufacturers

Section 232 is a less-known but crucial part of this deal. It relates to "national security" import regulations that allow the US to impose tariffs on specific categories of goods.

Historically, Section 232 was used for things like steel and aluminum—materials deemed critical for military production. The logic was: if the US doesn't produce enough domestic steel, and war disrupts imports, the country can't manufacture tanks or ships. That's a genuine national security concern.

Under Trump's first administration and continuing into 2025, Section 232 expanded to cover semiconductor manufacturing equipment. The reasoning: if fabs require specialized equipment and materials, and those supplies get disrupted, US chip production grinds to a halt.

The adjustment in this Taiwan deal addresses exactly this friction. Taiwanese companies with US production facilities get higher import thresholds without triggering Section 232 duties. This matters because:

Advanced fabs import constantly. A single TSMC fab uses thousands of tons of specialized materials annually. Photoresists (light-sensitive chemicals), rare gases, ultra-pure silicon, and precision parts all come from global suppliers. Building US fabs while maintaining Taiwan's import restrictions would create an impossible situation—you're setting up production but can't import the stuff needed to run it.

The carve-out acknowledges reality. US semiconductor production depends on global supply chains. The deal doesn't pretend otherwise. Instead, it recognizes that Taiwanese companies investing heavily in US operations should get preferential treatment on imports. It's an incentive aligned with the actual economics of manufacturing.

This cascades throughout the ecosystem. When TSMC imports more materials and equipment, suppliers expand US operations too. Dutch equipment makers hire US engineers. Japanese material suppliers set up US distribution centers. The semiconductor industry isn't just one company—it's a complex ecosystem, and this deal encourages more of that ecosystem to establish US operations.

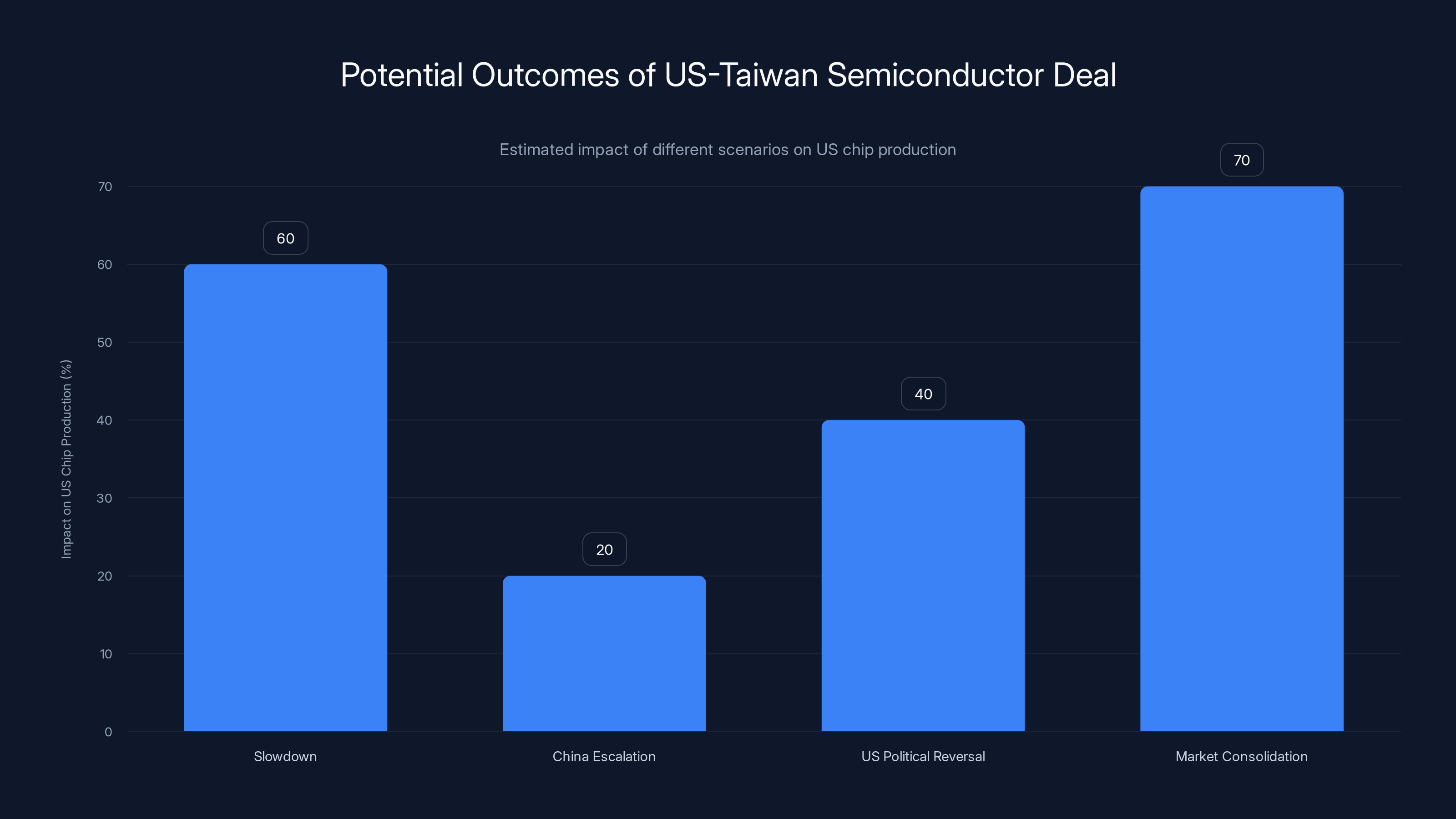

Estimated data shows varying impacts on US chip production under different scenarios, with 'Market Consolidation' having the highest potential production but increased dependency on TSMC.

Tariff Exemptions and Carve-outs: Reading Between the Lines

The deal explicitly exempts certain categories from reciprocal tariffs: generic pharmaceuticals, aircraft components, and unavailable natural resources.

This reveals what the US government actually cares about and where it's willing to negotiate.

Generic pharmaceuticals: The US faced drug shortages during the pandemic. Many generic drugs come from Taiwan and India. Applying tariffs to generic medications would increase healthcare costs and face domestic political opposition. Exempting them was a no-brainer.

Aircraft components: Commercial aviation is vital to US economic interests. Boeing and Airbus source many components globally, including from Taiwan. Tariffing aircraft parts would increase plane prices and potentially harm the aviation industry and its workers.

Unavailable natural resources: This is diplomatic cover. Taiwan doesn't have many natural resources the US can't source elsewhere. But including this exemption signals flexibility and prevents future disputes about what qualifies.

What's NOT exempted: Notice that semiconductors, advanced materials, and tech equipment stay within the tariff framework. The US is saying: "We'll make deals on some things, but not on the core electronics and advanced manufacturing that drive future competitiveness." This is strategic prioritization.

The Competitive Landscape: How Samsung and Intel Fit In

TSMC dominates foundry services globally. But they're not alone, and this deal affects the broader competitive landscape.

Samsung's position: Samsung is South Korea's chip giant and the second-largest foundry player globally. Samsung has already announced significant US fab investments separate from the Taiwan deal. They're expanding in Texas. Why? Samsung understands that wherever manufacturing happens, supply chains and customers follow. If chip production moves to the US, Samsung doesn't want to be left out.

Samsung's advantage: South Korea has a free trade agreement with the US, predating this Taiwan deal. Samsung already gets favorable treatment. But Samsung also recognizes that having a Taiwanese competitor (TSMC) dominating US production capacity would be strategically disadvantageous. So Samsung is racing to expand in Texas and potentially Arizona too.

Intel's transformation: Intel, the American chip giant, spent decades as a design-and-manufacturing integrated company. But Intel's manufacturing has fallen behind. Their fabs produce chips at older process nodes (14nm, 10nm) while TSMC and Samsung race ahead with 3nm and 5nm production.

Intel is now pivoting toward foundry services—essentially competing with TSMC. They're expanding fabs in Arizona, Ohio, and other states, partly with CHIPS Act funding. The Taiwan deal doesn't directly help Intel compete with TSMC for Taiwanese business. But it creates massive demand for advanced chip production in the US. Intel, with its Arizona fabs and ambitions in foundry, could capture some of this demand.

Media Tek and other players: Media Tek, another Taiwanese chip company, might eventually expand US operations. So could smaller Taiwanese semiconductor firms. The deal creates the economic incentive structure; now it's about which companies actually execute.

Estimated data shows a strategic distribution of semiconductor production to enhance supply chain resilience, reducing reliance on any single region.

Labor, Skills, and Workforce Development: The Human Factor

Here's something trade agreements rarely discuss directly: you need skilled people to run fabs.

TSMC's Arizona facility hired over 5,000 workers. These weren't all minimum-wage jobs. Fabs need process engineers, maintenance technicians, materials scientists, and experienced managers. The skills required took Taiwan decades to develop.

The challenge: Arizona has tech talent (Intel's presence helped establish that), but there's not a deep bench of experienced fab workers. TSMC will have to train people from scratch in many cases. This requires time and investment beyond the capital costs of buildings and equipment.

Taiwan's advantage: Taiwan trained generations of semiconductor workers. That expertise isn't easily transferable. TSMC will likely send experienced Taiwanese managers and engineers to Arizona to lead and mentor the local workforce. Some will stay long-term; others will train successors and return to Taiwan.

The broader opportunity: If chip manufacturing establishes deep roots in the US, future generations of American engineers will have career paths in the industry. Universities in Arizona, Ohio, Texas, and other states will add relevant degree programs. This creates a virtuous cycle where local talent becomes available, reducing reliance on imported expertise.

It's a multi-decade transformation. The trade deal provides the economic framework, but the actual skill development and cultural integration take 10-20 years. Companies don't hire experienced fab workers—they develop them internally through years of training.

Timeline and Reality: When Does This Actually Happen?

Government announcements and economic agreements often have timelines that diverge from reality. So when does TSMC's expanded Arizona presence actually come online?

The committed facilities: TSMC's first Arizona fab was announced in 2020, construction began in 2021, and it was supposed to start producing in 2023. Real-world delays pushed this to late 2023 and into 2024. This facility is now ramping production. A second facility followed a similar timeline—announced in 2021, construction in 2022, production starting in late 2024.

The new expansion: With this 2025 trade deal, TSMC is discussing additional facilities. These have not been formally announced as of early 2025, but industry reports indicate discussions are underway. If announced in 2025, these facilities could begin construction in 2026-2027, with production starting in 2029-2030 at the earliest.

**The

What success looks like: By 2030, TSMC and possibly other Taiwanese firms will operate multiple advanced fabs in the US, producing cutting-edge chips (3nm and below) at meaningful scale. This doesn't require moving all of TSMC's operations to the US—just enough to demonstrate commitment and reduce US dependence on Taiwan.

Risks to the timeline: Supply chain disruptions, chip market downturns, geopolitical changes, or changes in US government policy could all accelerate or delay these timelines. If the US changes administrations and tariff policies shift, the economic incentives evaporate. If a major recession hits, chip demand plummets and new fab investments might pause. These are real scenarios that could derail the plan.

Geopolitical Implications: Taiwan, China, and US Strategy

This trade deal exists within a much larger geopolitical context. The elephant in the room is China.

China's concern: China views Taiwan as a renegade province that should ultimately unify with mainland China. The US view is more complicated—the US doesn't officially recognize Taiwan as an independent nation (due to agreements with China), but it's committed to Taiwan's democracy and prosperity under the Taiwan Relations Act.

Semiconductor supply chains are at the center of this tension. China desperately wants advanced chip manufacturing capability. The US and allies have maintained export controls preventing China from accessing the most advanced chip design tools and manufacturing equipment. Taiwan, positioned between these superpowers, has benefited from playing multiple sides.

What this deal signals: The US is making a bet that reducing Taiwan's economic dependence on the US while increasing Taiwan's economic integration with the US through manufacturing partnerships strengthens the relationship. If TSMC and other Taiwanese companies have massive operations in Arizona, Arizona politicians and US business leaders have a vested interest in Taiwan's stability. Investment creates political ties.

China's response: China will likely increase attempts to woo Taiwanese companies with incentives. China will also accelerate its own semiconductor development programs. But China's lacking in semiconductor equipment (dominated by European and Japanese companies that respect US export controls) and design tools (Nvidia's CUDA, Qualcomm's architectures, etc.). Closing this gap takes a decade or more.

The strategic depth: By establishing semiconductor manufacturing in the US, Taiwan increases its leverage with the US. Taiwan becomes not just a security issue—it becomes an economic issue. Protecting Taiwan protects US jobs, US technical capability, and US economic interests. This transforms Taiwan from a strategic liability into a strategic asset.

Economic Impact: Jobs, Investment, and Multiplier Effects

When TSMC invests $12 billion in Arizona, the ripple effects extend far beyond the company itself.

Direct jobs: A TSMC fab employs roughly 3,000-5,000 workers depending on automation level and production scale. These are high-wage jobs (average $100K+ annually for technical roles). Multiply this across multiple fabs: 3-4 facilities means 10,000-15,000 direct jobs.

Indirect and induced jobs: For every direct job in manufacturing, economic research suggests 2-3 additional jobs are created in supporting industries. Suppliers, logistics, food services, real estate, and professional services all grow to support fab workers. The multiplier effect could result in 30,000-45,000 total jobs across multiple fabs and their ecosystem.

Regional economic growth: Arizona's economy will shift. Phoenix and surrounding areas will see:

- Increased commercial real estate demand (office parks, hotels, restaurants)

- Higher wages for technical workers

- More venture capital flowing to chip-adjacent startups

- Greater demand for specialized equipment suppliers

- Tax revenue increases for state and local governments

Ohio, Texas, and other states with fab investments will see similar effects.

Supply chain development: Current US suppliers of fab materials and equipment will expand. Companies will build new facilities. Entirely new suppliers might emerge to serve the fabs. This creates a circular economic stimulus.

Timing of benefits: The full economic impact won't hit immediately. Construction jobs start in 2026-2027. Fab employment comes in 2028-2030. Full operational capacity and supply chain integration extends to 2035+. But the commitment is being made now, which drives investor confidence and smaller investments today.

Challenges and Obstacles: This Doesn't Happen Automatically

The deal sounds great on paper. But actually executing is a different matter. Multiple challenges could derail or slow execution.

Environmental regulations: Chip fabs are water-intensive and produce chemical waste requiring careful management. Arizona is water-stressed. EPA regulations are strict about chemical discharge. TSMC will face environmental reviews, local opposition, and potential restrictions. Building a fab in Arizona takes not just capital but environmental approval.

Skilled labor shortage: The US has experienced workforce shortages in technical fields for years. Finding 10,000-15,000 skilled fab workers (when the entire US semiconductor workforce is roughly 120,000) requires massive training investment. TSMC will compete with Intel, Samsung, and other tech companies for the same talent pool.

Political volatility: The deal is dependent on US government support. If administrations change, tariff policies shift, or geopolitical relations with Taiwan change, the incentives evaporate. Taiwanese companies making massive long-term bets need policy certainty. Recent US political swings create real uncertainty.

Supply chain dependencies: Even with US fabs, chip production depends on importing materials and equipment. If China restricts exports of critical materials, or if geopolitical tensions escalate, Taiwanese companies might hesitate to invest further in the US.

Economic cycles: Chip demand is cyclical. If the industry enters a downturn while major fab expansions are underway, return on investment plummets. Taiwanese companies might reduce new investments. This happened somewhat in 2023, when chip demand fell and companies paused fab expansion plans.

The Taiwan Strait question: This is the elephant in the room. If military conflict erupts in the Taiwan Strait, or if China invades Taiwan, everything changes. Taiwanese companies might lose assets or face restrictions on US operations. The deal assumes a status quo that isn't guaranteed.

Alternative Scenarios: What If This Doesn't Work?

Let's consider scenarios where the deal doesn't produce its intended results.

Scenario 1: Slowdown and Partial Commitment

Taiwanese companies invest in the US, but less than the full

Scenario 2: China Escalation

China invades Taiwan or creates a military blockade in 2027-2028. Taiwanese companies halt US expansion. Assets in Taiwan become inaccessible. The deal collapses. The US is left with partially built fabs and incomplete supply chains. This is a worst-case scenario with massive geopolitical consequences.

Scenario 3: US Political Reversal

A future US administration reduces tariffs on Chinese electronics or changes CHIPS Act incentives. The economic rationale for Taiwanese investment evaporates. Companies pause US expansion. Existing facilities remain but no new ones are built. This is less catastrophic than Scenario 2 but means the US fails to achieve meaningful supply chain independence.

Scenario 4: Market Consolidation

TSMC becomes so dominant in US production that other chip companies are squeezed out. Intel's fabs can't compete. Samsung focuses on South Korea. By 2035, the US has advanced chip production, but it's concentrated with TSMC. This creates a different vulnerability—dependence on a Taiwanese company rather than multiple sources.

None of these scenarios invalidate the deal's strategic logic. But they highlight that execution, geopolitics, and market dynamics will all influence outcomes.

The Broader Context: Why Now? Why This Scale?

Trade deals don't emerge randomly. Understanding why this deal happened now requires looking at broader trends.

Post-pandemic supply chain anxiety: The 2020-2021 pandemic exposed how fragile global supply chains are. Companies, governments, and economists all became obsessed with resilience. This deal is a manifestation of that anxiety.

US-China competition: The US views competition with China as the defining geopolitical challenge of the coming decades. Semiconductors are central to this competition. Keeping Taiwan prosperous, secure, and aligned with US interests is a core strategic priority.

Taiwan's demographics: Taiwan's population is aging and growing slowly. Labor availability will tighten. Some manufacturing becoming less viable in Taiwan over time. Taiwan's government welcomes overseas investment to maintain employment and economic growth.

TSMC's maturity: TSMC is mature and hugely profitable. They can afford to invest $20+ billion annually in new capacity. The company is large enough that geographic diversification is strategic, not risky.

US government willingness to use tariffs: Tariffs became a mainstream policy tool again in the 2020s. Reciprocal tariffs, Section 232 adjustments, and targeted tariffs on semiconductors are no longer controversial—they're standard policy. This creates the incentive structure the deal depends on.

Alignment across stakeholders: US workers want advanced manufacturing jobs. Taiwanese companies want reduced tariffs. Taiwan's government wants deeper US ties. Arizona and other states want economic development. All these interests aligned, making the deal possible.

Looking Forward: The Next 10 Years

If the deal executes as intended, here's what the semiconductor landscape looks like in 2035:

US manufacturing capacity: The US produces 20-25% of global advanced semiconductors (up from roughly 12% currently), with additional capacity for older nodes. This is concentrated in Arizona, Ohio, and Texas with TSMC, Intel, and Samsung operating multiple facilities.

Taiwan remains central: Taiwan still produces 40-45% of global semiconductors. Taiwan's fabs remain the most advanced and efficient. Taiwan has become more of a hub for chip design, specialized manufacturing, and advanced R&D.

South Korea expands: Samsung expands its US footprint and maintains strong production in South Korea. South Korea becomes a more important hedge against Taiwan-focused supply chain vulnerabilities.

Supply chain redundancy: Semiconductors are no longer a single point of failure. Disruption in Taiwan affects global supply chains but doesn't disable them. Alternative sources exist for most chips.

New vulnerabilities emerge: As manufacturing disperses, new vulnerabilities appear. Rare materials, precision equipment, design tools, and other parts of the ecosystem become bottlenecks. Managing these new vulnerabilities becomes the focus.

Economic impacts: The US sees the promised job creation, wage growth, and investment. Arizona and Ohio transform into tech hubs. But costs are higher—US production is more expensive than Taiwan production, costs are passed to consumers and companies, and ultimately this is managed through tariff structures and subsidies.

FAQ

What exactly is the Taiwan semiconductor trade deal?

The deal is an agreement between the US Department of Commerce and Taiwanese businesses committing Taiwanese companies to invest at least

Why is this deal important for the semiconductor industry?

The semiconductor industry depends on complex global supply chains, with Taiwan currently producing over 60% of advanced chips globally. This deal fundamentally shifts where manufacturing happens. TSMC and other Taiwanese companies will establish multiple US fabs producing cutting-edge chips. This reduces the industry's vulnerability to Taiwan-specific disruptions (military conflict, natural disasters, political change) while establishing redundancy in global chip production. For the industry, it means more localized production, closer customer relationships, and new partnerships between American and Taiwanese companies.

How does this affect chip prices?

The immediate effect is unlikely to be dramatic price decreases. US manufacturing is more expensive than Taiwan manufacturing due to higher labor costs and operational overhead. These costs are partially offset by tariff eliminations and subsidies, but US-produced chips will generally cost 5-15% more than identical chips produced in Taiwan. However, the deal creates supply security benefits—companies can access chips without worrying about Taiwan-specific disruptions, which is worth a premium. Over 20-30 years, as US manufacturing scales and automation increases, cost differentials should narrow.

Will TSMC stop producing chips in Taiwan?

No. TSMC will remain a major manufacturer in Taiwan. This deal expands US operations without reducing Taiwan operations. TSMC has committed to continued investment in Taiwan while adding US capacity. In fact, by diversifying geographically, TSMC becomes stronger—less vulnerable to any single location's disruption. Taiwan remains central to TSMC's operations, particularly for advanced manufacturing where their expertise is most concentrated.

How long will it take for these new fabs to produce chips?

From formal announcement to first production typically takes 3-5 years. TSMC's first Arizona facility was announced in 2020 and began limited production in 2023. A second facility followed. For new facilities announced in 2025, construction would begin in 2026-2027, with production starting in 2029-2030. Full operational capacity and volume production require additional time—2-3 years after first production. So realistically, new TSMC fab capacity from this deal starts producing in late 2029 and ramps fully by 2033-2035.

What does this mean for China and semiconductor competition?

This deal is explicitly designed to reduce China's access to advanced chips and chip manufacturing expertise. By keeping Taiwan prosperous and aligned with the US, and by establishing semiconductor production in the US, the deal reduces China's leverage. China has been attempting to develop its own advanced chip manufacturing but faces restrictions on importing key equipment and design tools (due to US export controls). This deal essentially bets that the US will maintain and enforce these controls while building sufficient domestic capacity to avoid being dependent on unreliable suppliers.

Could this deal fall apart?

Yes, for several reasons. Political changes in the US could reverse tariff policies. Military conflict in the Taiwan Strait could disrupt everything. Chip market downturns could make investments less attractive. Environmental regulations could slow fab construction. Supply chain disruptions (especially equipment from Netherlands or Japan) could delay projects. Skilled labor shortages could make US operations less competitive. The deal is a strategic commitment, but execution depends on multiple variables remaining stable. A 5-10 year horizon is fairly robust; 15-20 year timelines face higher uncertainty.

How does this compare to other countries' semiconductor strategies?

Europe is pursuing its own chip manufacturing expansion with the European Chips Act, targeting European production capacity of 20% globally. South Korea continues aggressive Samsung investment. Japan maintains leading positions in materials and equipment. Taiwan remains focused on maximizing advanced manufacturing. The US approach is distinctive: using tariffs as incentives to attract foreign manufacturers while also subsidizing domestic companies (Intel). This creates a hybrid approach—partner with foreign firms while building domestic capability. It's more pragmatic than Europe's approach and more direct than previous US policy.

What should business leaders know about this deal?

If your company depends on semiconductors, start diversifying suppliers. US-produced chips will increasingly be available from established fabs, reducing Taiwan dependence risk. If you're in Arizona, Ohio, or Texas, the semiconductor expansion will drive economic activity—consider supply chain positioning and workforce development. If you're in countries like Netherlands or Japan that supply equipment or materials, US fab expansion creates new customers and opportunities. If you're investing in semiconductor companies, US policy and tariff structures are now core to investment theses—these aren't just economic decisions anymore, they're geopolitical ones.

Conclusion: A Decade of Transformation Begins

The $250 billion Taiwan-US semiconductor trade deal marks the beginning of a historic reorientation of global chip manufacturing. For the first time in decades, the US is making credible commitments to developing advanced semiconductor manufacturing capability on its own soil. Taiwan is investing hundreds of billions to establish redundancy beyond its island. The geopolitical message is clear: chip supply chains will be less concentrated, less vulnerable, and more distributed globally.

This transformation doesn't happen overnight. The first few years will be construction, hiring, and infrastructure development. By 2030-2032, meaningful US production of advanced chips will be online. By 2035-2040, US semiconductor production could account for 20-25% of global capacity for advanced chips—a transformative shift from today's roughly 12%.

What makes this different from previous attempts to onshore manufacturing: the incentives actually align. TSMC and other Taiwanese companies benefit from lower tariffs and government support. US workers benefit from high-wage manufacturing jobs. US companies benefit from domestic supply security. Taiwan benefits from deepening US economic ties. Even China, ironically, might benefit long-term by losing some semiconductor leverage over the US (making US-China relations less fragile).

But challenges remain. Political volatility, geopolitical tensions, supply chain disruptions, labor shortages, and environmental constraints could all derail execution. The deal assumes a relatively stable world order where Taiwan remains independent, the Taiwan Strait doesn't escalate militarily, and US policy remains consistent across administrations. Any of these assumptions could break.

What's certain is that semiconductors have become a critical strategic asset. Countries and companies that control manufacturing, design, and materials have outsized influence. This trade deal represents the US recognizing this reality and making concrete moves to ensure it remains competitive. Taiwan is betting that its success depends on partnerships beyond its island. Companies in the semiconductor ecosystem are positioning themselves for a more distributed, less fragile supply chain.

The next decade will reveal whether this ambitious vision translates to reality or becomes another unfulfilled government promise. Either way, the semiconductor industry is entering a period of profound transformation.

This analysis is based on publicly available information from government announcements, corporate disclosures, and industry reporting. Actual results will depend on implementation timelines, geopolitical developments, and market conditions. The semiconductor industry is fast-moving; policy and business strategy should incorporate regular monitoring of developments as the deal executes.

Key Takeaways

- Taiwan and US signed a 250B direct business investment with $250B government credit guarantees

- TSMC is positioned to expand Arizona operations significantly, bringing advanced chip production to the US with 3-5 year timelines for new facilities

- Tariff reductions from 20% to 15% plus Section 232 import adjustments create powerful economic incentives for Taiwanese companies to establish US manufacturing

- The deal targets onshoring 40% of Taiwan's semiconductor supply chain to the US, reducing dependence on single-location production

- Geopolitical benefits include strengthening US-Taiwan economic ties, reducing supply chain vulnerability, and establishing manufacturing redundancy

Related Articles

- Taiwan's $250B US Semiconductor Investment: What It Means [2026]

- Micron's AI Memory Pivot: What It Means for Consumers and PC Builders [2025]

- US 25% Tariff on Nvidia H200 AI Chips to China [2025]

- Micron Kills Crucial Brand: What It Means for RAM Consumers [2025]

- Samsung AI Chip Boom Drives Record $13.8B Profits [2025]

- AMD Radeon GPU Price Increases Coming in 2025