The Next Generation of Music Discovery is Here

Remember iTunes? That hulking desktop application that seemed to own your entire digital life for nearly two decades? It was more than just software. It was a portal. You could buy songs, organize them, sync them to your iPod, and share what you were listening to with friends. It was messy, sure. It required actual curation. But it felt like yours.

Then streaming came along and flipped the script entirely. Spotify won. Apple Music followed. Amazon Music, Tidal, and YouTube Music carved out their niches. But something got lost in that consolidation. We traded ownership for convenience, curation for algorithms, and connection for isolation within walled gardens.

Now, there's a quiet revolution happening in music tech. A new breed of applications is emerging, built on what the industry is calling "vibe-coding." These apps use AI not to replace human taste, but to augment it. They sit on top of the existing streaming ecosystem, unifying music libraries across multiple services, turning social feeds into playlists, and letting music move freely between friends regardless of which subscription they use.

Parachord is one of the most promising examples of this shift. Built by J Herskowitz, a veteran of Spotify, LimeWire, and AOL Music, it's a new take on an old idea. Herskowitz actually built something like this before, back in 2011. It was called Tomahawk, and it was way ahead of its time. Now, with the help of Claude AI, he's rebuilding that vision for an era where AI can do in weeks what once took teams of developers months.

But here's what's really interesting: Parachord and apps like it aren't trying to compete with Spotify. They're not trying to replace your subscription. Instead, they're trying to solve a problem that the major streaming platforms have almost completely ignored. They're building for the music nerds, the tastemakers, the people who buy songs on Bandcamp, track their listening on Last.fm, and follow underground DJs on Bluesky.

This isn't a story about a new app. It's a story about how AI is enabling a new wave of independent developers to tackle problems that seemed impossible just five years ago. It's about how niche can be viable again. And it's about how the next iTunes might not come from Apple at all.

TL; DR

- Vibe-coding uses AI to build apps that augment human music taste without replacing personal curation or forcing algorithmic homogeneity

- Parachord unifies Spotify, Apple Music, and Bandcamp, allowing friends to share recommendations across service boundaries

- AI development tools like Claude Code enable solo developers to rebuild complex applications in weeks instead of months

- The music app market is fragmenting into micro-niches where niche audiences support indie apps that major platforms ignore

- Social music discovery is making a comeback through DJ feeds, Last.fm integration, and playlist sharing across platforms

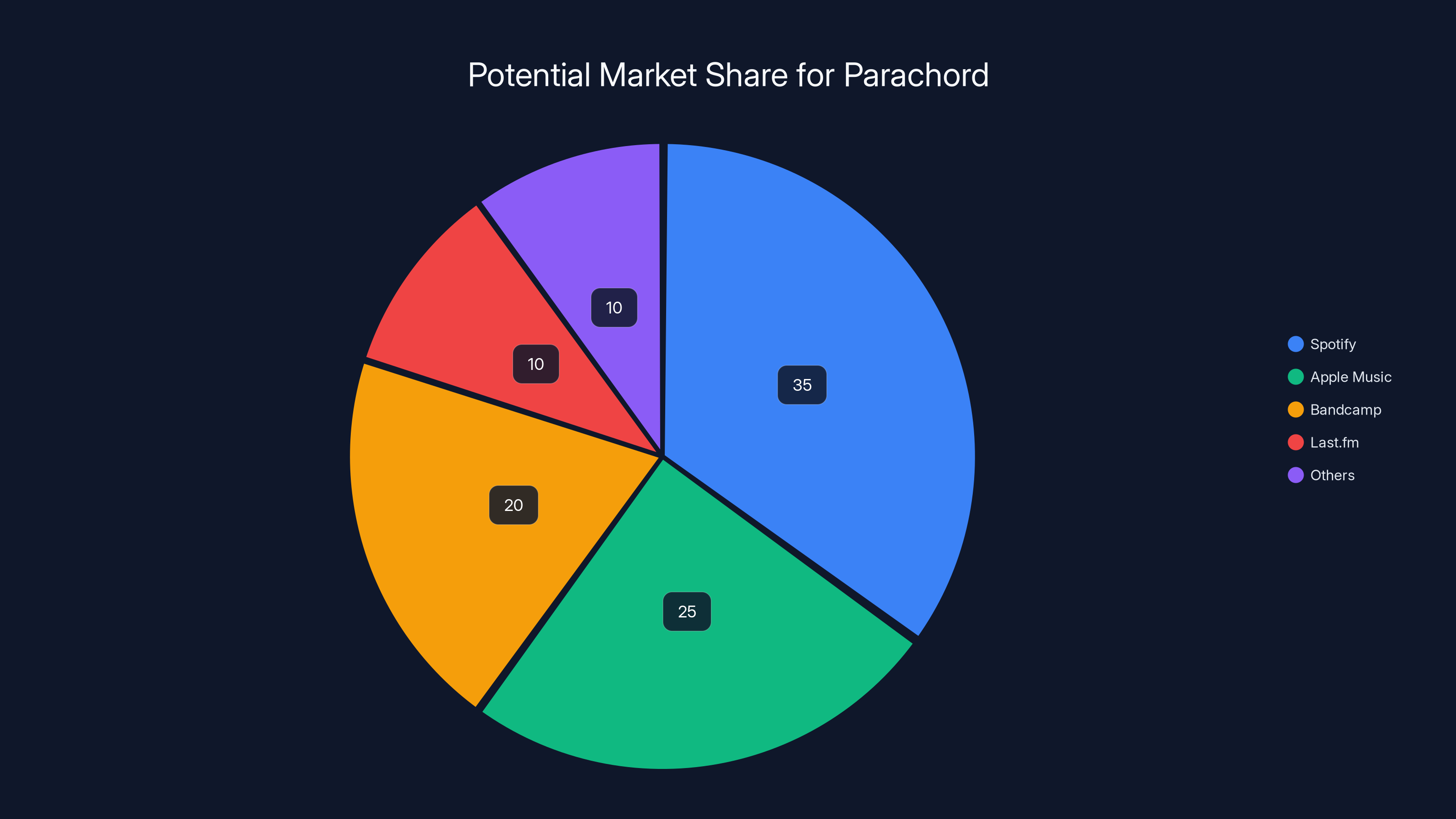

Estimated data suggests Spotify and Apple Music users make up the largest segments, with Bandcamp and Last.fm also significant. Estimated data.

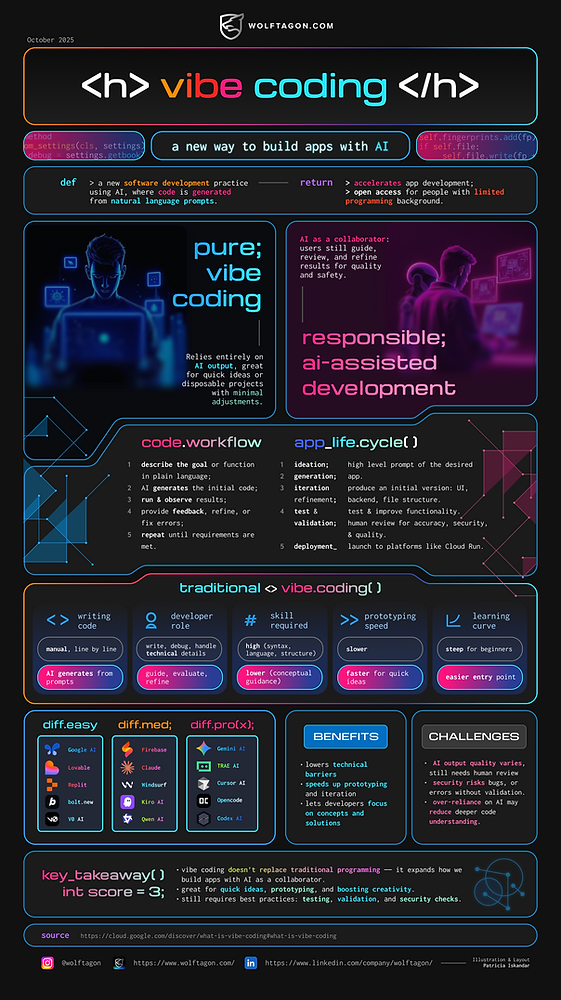

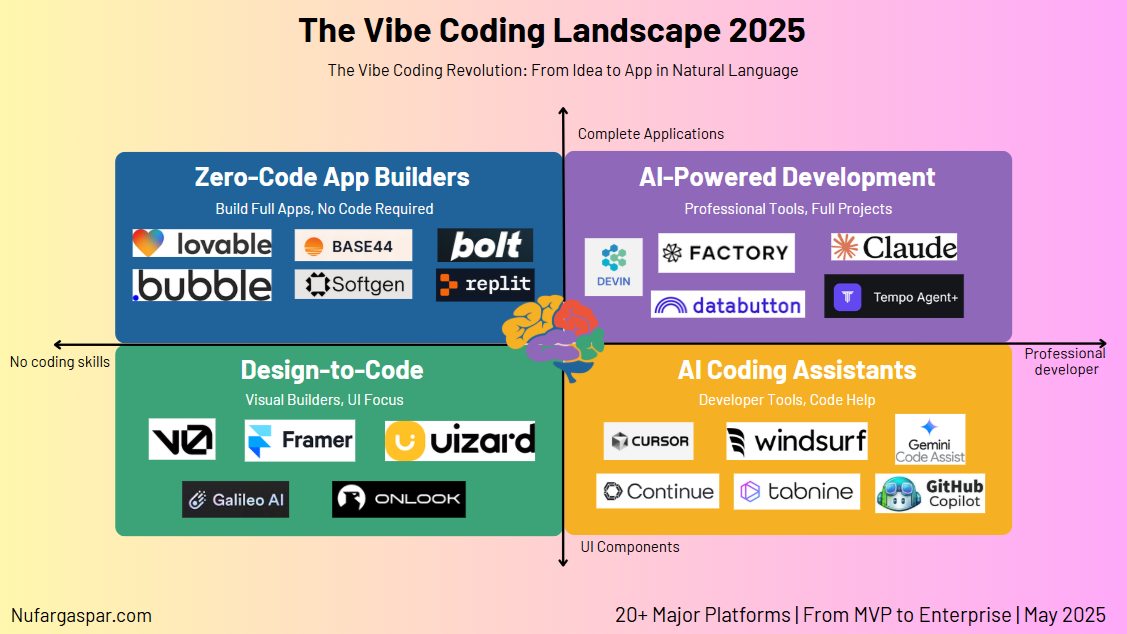

Understanding Vibe-Coding: What It Actually Means

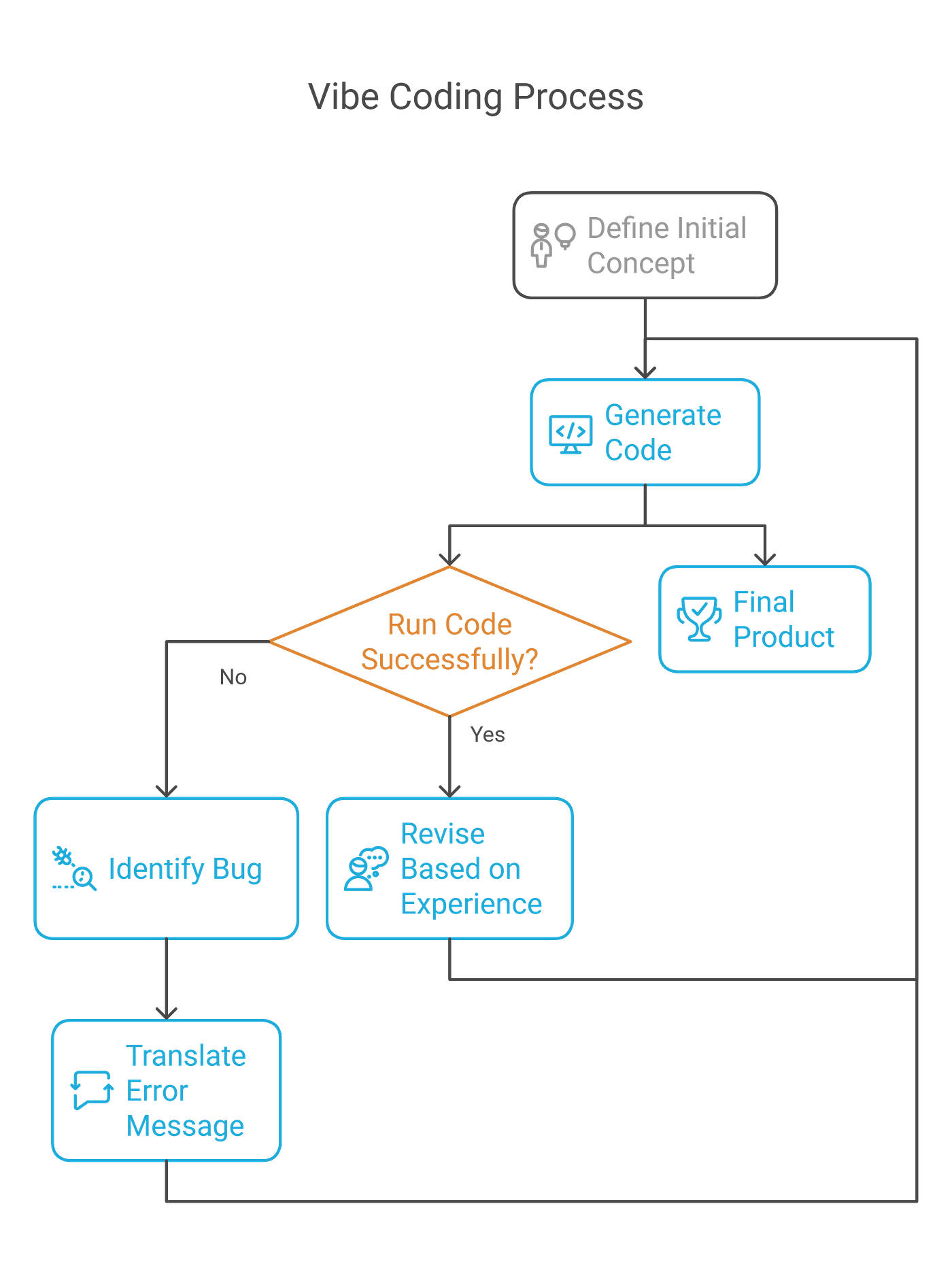

Let's be clear about something right off the bat. "Vibe-coding" isn't some mystical development philosophy. It's not about channeling creative energy or writing code while listening to lo-fi beats on YouTube. The term actually has a fairly practical origin, though it does capture something genuinely important about how modern development is shifting.

Vibe-coding refers to the practice of describing what you want to build to an AI, not by writing detailed specs or providing intricate technical documentation, but by describing the feeling or the vibe of the application. You give the AI an overall sense of what the app should do, show it examples, maybe point it at existing code, and let it fill in the details. It's less about top-down engineering and more about conversational, iterative building.

For the music app space specifically, this means something pretty powerful. A solo developer can describe what they want: "Make an app that brings together songs from Spotify and Bandcamp, lets me follow DJs on social media, and turns their posts into playlists." Then Claude, ChatGPT, or another AI assistant can start building against that vision. The developer doesn't need to know every library, every API endpoint, every data structure. They can learn as they go, asking the AI questions, refining the vision together.

The shift here is fundamental. For the past 15 years, building music software required serious resources. You needed a team of developers. You needed backend engineers, frontend engineers, maybe a machine learning specialist. You needed months of planning before a single line of code got written. The barrier to entry was so high that only well-funded startups or major tech companies could even attempt it.

Now? A product manager with no traditional coding experience can rebuild a complex music application in a few weeks, using nothing but AI and persistence. That's not hype. That's literally what happened with Parachord.

But vibe-coding doesn't work the same way for every project. It's particularly powerful for applications that are building on top of existing services, integrating APIs, and connecting disparate data sources. It's less useful for applications that require novel algorithms or cutting-edge machine learning. For music discovery apps, though, which are fundamentally about orchestration and integration, it's almost perfectly suited.

The History of Unified Music Apps: Why Tomahawk Mattered

To understand why Parachord is interesting, you need to understand Tomahawk. And to understand Tomahawk, you need to go back to 2011, a period in music history that feels almost quaint now.

Back then, the music streaming landscape was completely fragmented. There was Spotify, growing fast but still not available everywhere. Rdio was thriving in North America. Grooveshark was the wild west, operating in a legal gray area. Beats Music was just starting to take off. MOG was gaining traction. The idea that we'd eventually consolidate around two or three services seemed impossible.

Into this chaos, J Herskowitz and a small group of developers built Tomahawk. The genius of Tomahawk was its architecture. Instead of locking users into a single streaming service, Tomahawk used a plugin system. Need Spotify integration? There's a plugin. Want to pull from Rdio? There's a plugin for that too. The application itself was service-agnostic. It was a universal jukebox that could draw from whatever music sources were available.

Tomahawk did something else that was genuinely innovative: it turned music discovery into a social thing. You could follow other users, see what they were listening to, and their playlists would show up in your feed. If a DJ you followed added a new song, you'd see it. If a friend published a playlist, you could access it regardless of what streaming service they used. For music nerds, it was revelation.

The problem was revenue. Tomahawk had a fascinating idea, but no clear way to make money from it. Streaming services weren't incentivized to help a third-party app aggregate their catalogs. Ad revenue wasn't enough to sustain development. By 2015, the team needed to make a living, so Tomahawk gradually faded away.

But here's the thing: Tomahawk never fully died. As an open-source project, the code was published on GitHub. It just sat there, becoming increasingly outdated as APIs changed and dependencies rotted away. Most people forgot about it. Most projects would have been completely lost.

Then, about a year ago, Herskowitz had an idea. What if he looked at that old code, fed it to Claude Code, and asked it to understand what Tomahawk was trying to do and rebuild it for 2025? The answer surprised everyone: it worked.

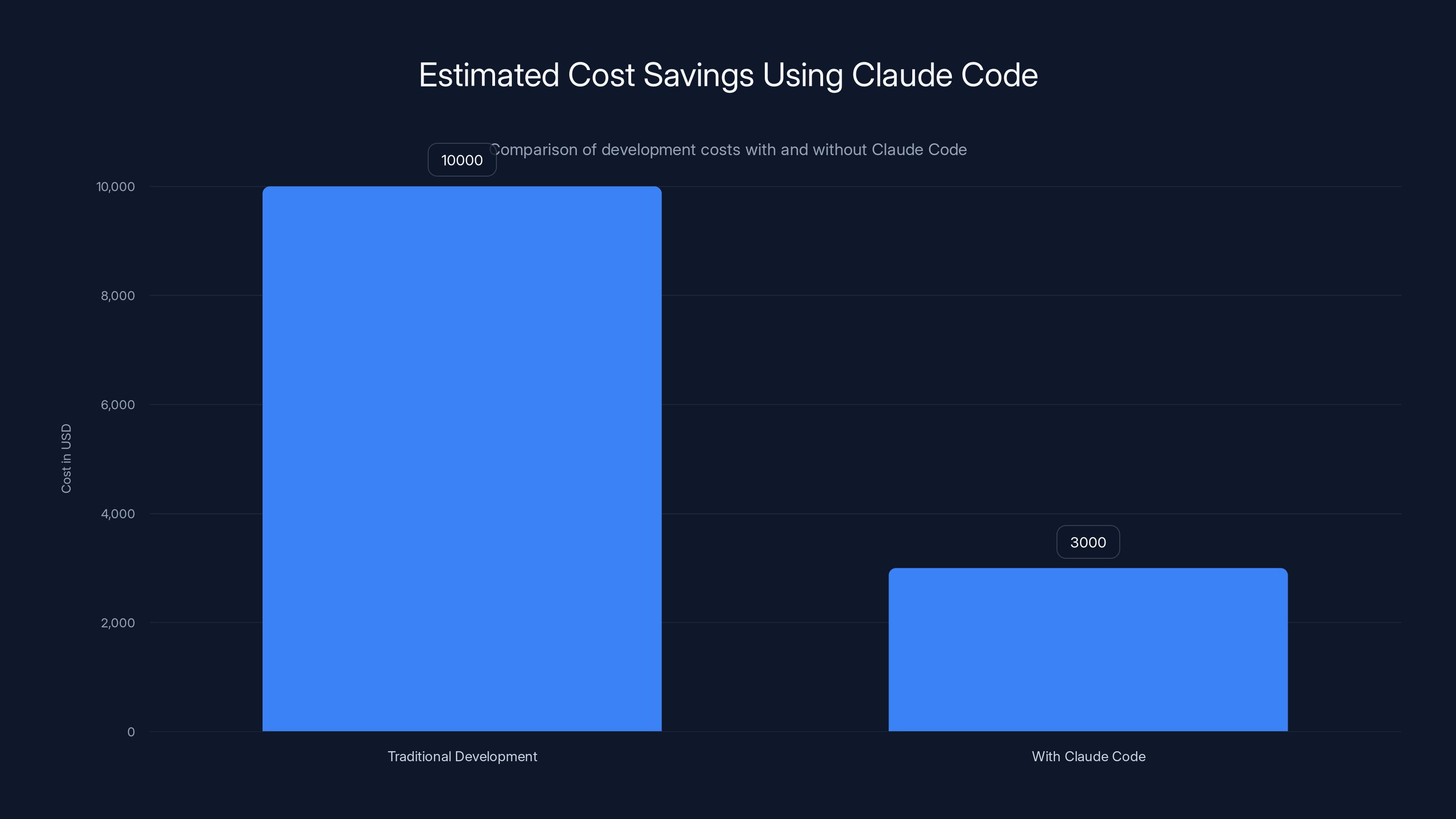

Using Claude Code for the project rebuild potentially saved around

How Claude Code Rebuilt a 15-Year-Old Project in Weeks

This is where things get weird and wonderful in equal measure. Herskowitz is a product manager by training. He's worked in music tech at major companies, but he doesn't consider himself a developer in the traditional sense. He knows business, he knows product, he knows music. But writing code? Not really his lane.

Yet he managed to rebuild Tomahawk and create Parachord. How? He used Claude Code, which is Claude's ability to read code, understand what it does, and help you modify or rewrite it.

The process sounds deceptively simple. Herskowitz pointed Claude at the Tomahawk repository on GitHub. He said something like: "Look at this. Understand what it does. Help me rebuild it for 2025." And Claude... mostly did. Not perfectly. Herskowitz had to guide it. He had to understand enough about what was happening to ask good follow-up questions. But the AI did the actual heavy lifting of reading old code, understanding its intentions, and creating something new that worked similarly but in a completely modern context.

This matters for a specific reason. Building a music app isn't like writing a blog post or creating a design mockup. It requires understanding API integrations, database schemas, event handling, state management, and dozens of other technical considerations. You can't just describe the vibe and hope for the best. You need actual, working code.

What Claude Code did was translate Herskowitz's understanding of what the app should do into actual working code, handling all those technical details in the process. When Herskowitz realized something wasn't quite right, he could ask the AI to explain why and help him fix it. It was almost like having a really smart junior developer paired with him, except the junior developer never got tired and could refactor entire subsystems when asked.

The economics here are worth dwelling on for a moment. Hiring even a junior developer costs at least

Does the app work perfectly? No. Herskowitz is the first to admit that it's still very experimental. But it works well enough to demonstrate that the vision is viable. And that proof of concept is worth far more than the money saved.

The Music Streaming Landscape in 2025: Winners and Losers

To understand why Parachord matters, you need to understand how completely the music streaming landscape has consolidated. And how that consolidation has left certain use cases almost completely unserved.

Spotify won. That's the basic fact. It's not the only streaming service, but it's the clear leader with over 500 million users and the most powerful discovery algorithms in the industry. Apple Music is second, with around 100 million users, mostly integrated into Apple's ecosystem. YouTube Music has captured a huge chunk of users because it's bundled with YouTube Premium. Amazon Music pulled in millions of Prime members. Tidal is still around, serving the hi-fi and artist-focused audio market.

But here's what happened in that consolidation: every service optimized for the 80/20 rule. They focused on giving the broad mass of users what they wanted. Good recommendations. Easy discovery. Familiar playlists and charts. Shuffle and repeat. The streaming equivalent of turning on the radio and letting whatever comes next wash over you.

What got left behind was the people who don't use streaming like that. The folks who buy individual songs on Bandcamp because they want to own them. The people who meticulously track their listening history on Last.fm because they're genuinely interested in their own musical patterns. The tastemakers who follow emerging artists on social media and want those discoveries to feed back into their music library.

Spotify's recommendation engine is powerful, but it's designed for Spotify data only. Apple Music users can't easily share playlists with Spotify users. Bandcamp purchases don't feed into any streaming recommendations at all. Last.fm data is almost completely isolated from actual music discovery. The music nerd who wants everything unified? Tough luck.

This is where Parachord comes in. It's specifically designed for the people that the major platforms don't optimize for. Not out of spite, but simply because optimizing for them isn't profitable at scale. But in 2024, it turns out, there are enough of these people, and the development tools have become cheap enough, that someone can build just for them.

How Parachord Actually Works: Unifying Music Across Platforms

So what does Parachord actually do? Understanding the specifics helps clarify why this matters.

At its core, Parachord is a music player and discovery application that sits on top of your existing streaming services. You connect your Spotify account, your Apple Music account, your Bandcamp collection, whatever you've got. Parachord then presents a unified interface to all of that music. But it doesn't just throw everything together in a big pile.

The first thing it does is solve the fundamental problem of music discovery across services. Let's say you follow a DJ on Bluesky. That DJ posts about a track they love. With Parachord, that post can be turned into a playlist automatically. The app searches across all your connected services to find that track and adds it. If it's not available on Spotify, it pulls from Apple Music. If neither has it, it pulls from Bandcamp. The track is added to a playlist that lives in Parachord, and you can listen to it on whatever service actually has it.

This solves a surprisingly common problem that major streaming services have completely ignored. Your friends use different services. Finding music that everyone can listen to together used to require email chains or shared links that often didn't work. With Parachord, you create a collaborative playlist. Your friend with Spotify adds a track. Your other friend with Apple Music adds a track. Everyone can listen, no matter what service they use.

The second thing Parachord does is integrate social music discovery directly. You can follow other users and see what they're listening to. You can see what songs they've marked as favorites. You can turn their favorite tracks into a playlist. This brings back the social layer that Tomahawk had, but with modern social platforms as the source. Follow a DJ on Bluesky? Parachord can scrape their recent posts, identify music references, find those tracks, and create a playlist from them.

The third thing Parachord does is use Last.fm data for smart recommendations. Last.fm is this wonderful service where music nerds have been obsessively tracking their listening for two decades. Parachord can pull that data and use it to generate recommendations. But here's where the AI aspect comes in: instead of recommending songs you've already listened to, it can use AI to recommend songs that fit your taste profile but are genuinely novel. It's personalization without algorithmic groupthink.

None of this is revolutionary on its own. But combined, it creates a music experience that the major platforms don't offer. It's opinionated. It's designed for people who care deeply about music. And crucially, it works in a way that respects the choices those users have already made about which services to use.

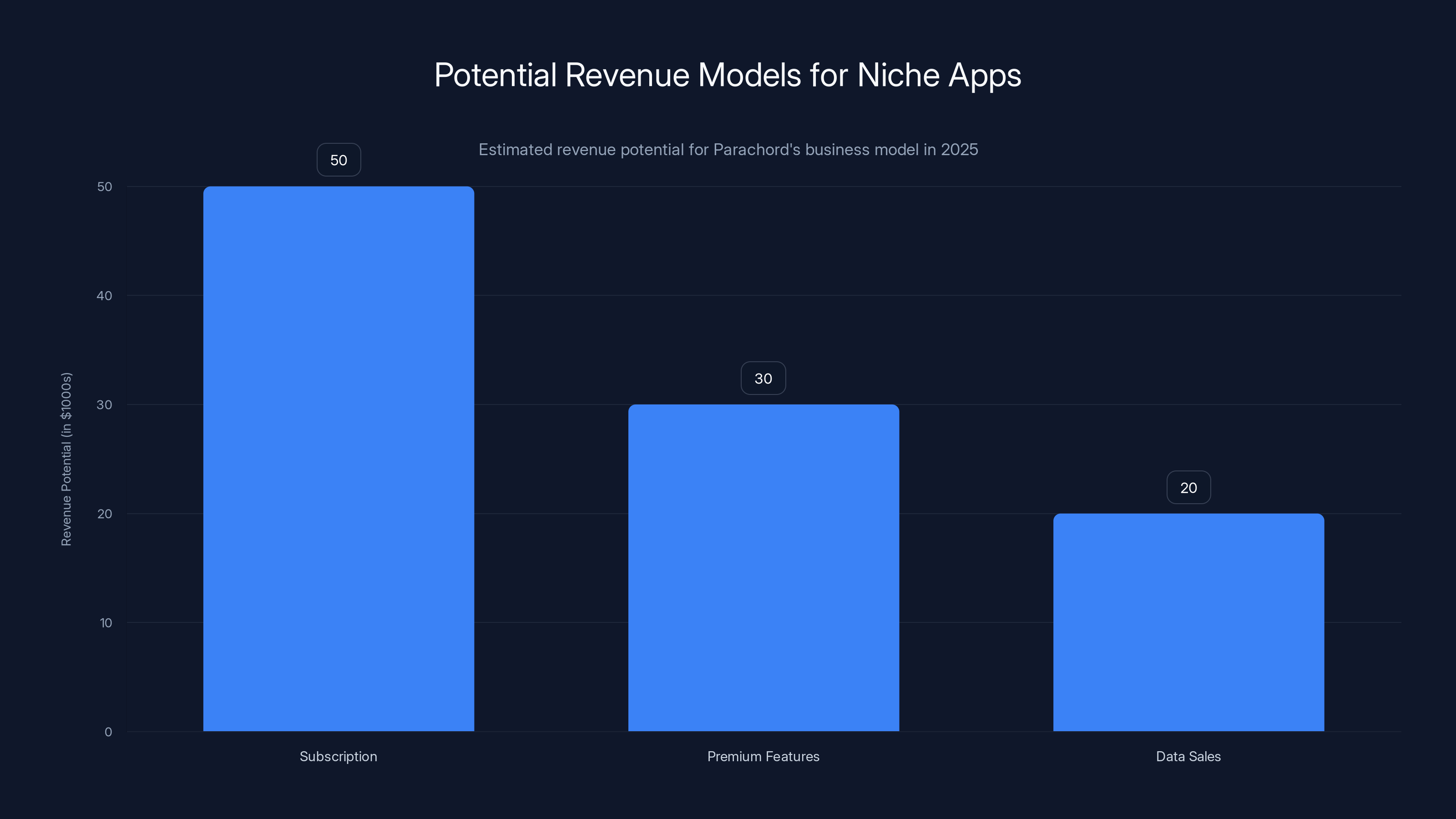

Estimated data suggests that subscription models could generate the highest revenue for niche apps like Parachord, followed by premium features and data sales.

The Economics of Niche Apps: Why Small Audiences Actually Work Now

Here's the question that killed Tomahawk: who pays for this? If you're not Spotify, if you're not Apple, if you don't have millions of users, how do you sustain development?

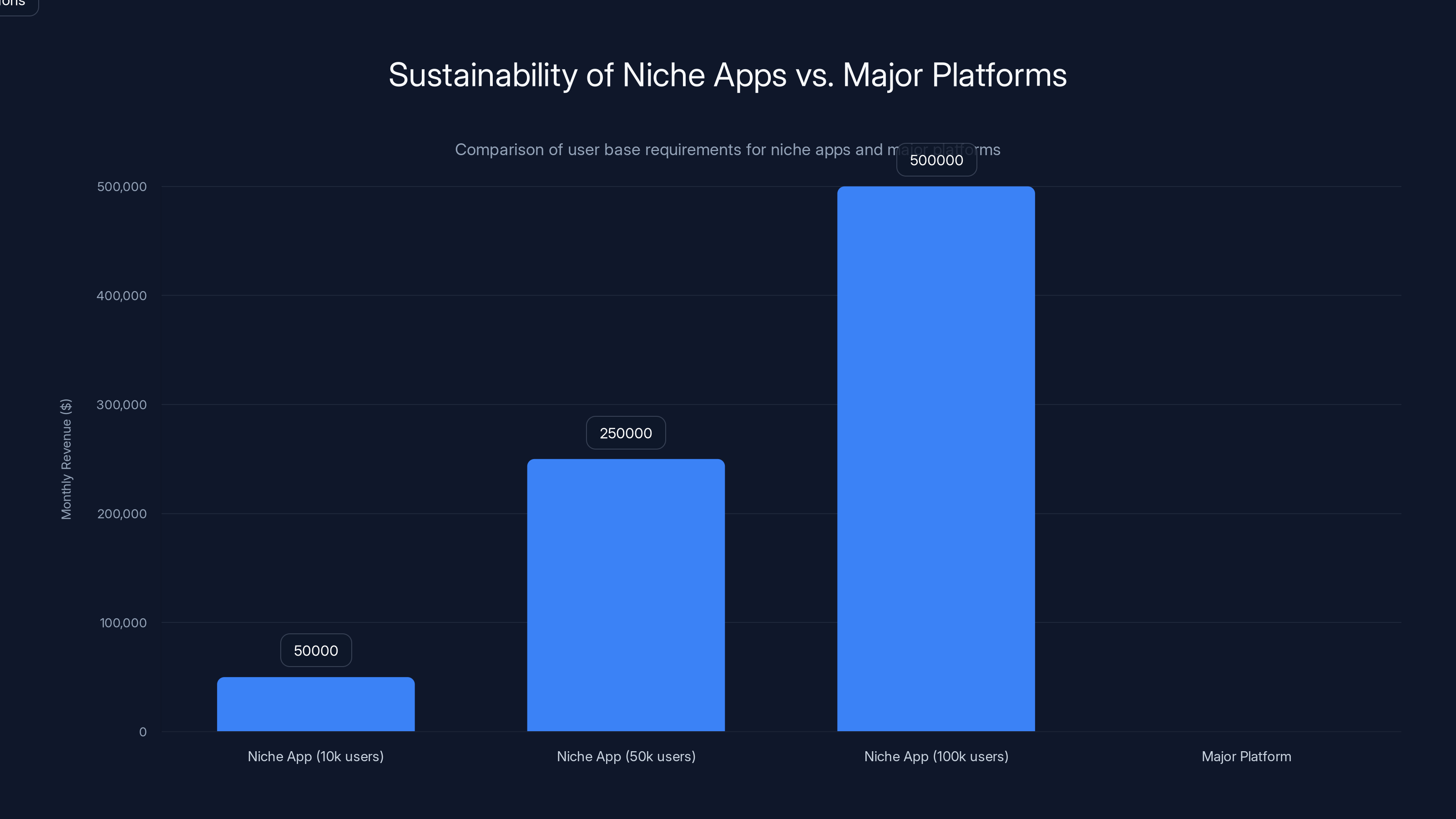

That's the wrong question for 2025. It's not about needing millions of users. It's about needing thousands of dedicated users. And the economics have shifted in ways that make that viable.

First, development costs have collapsed. As we discussed, Claude Code and similar tools mean one person can build what would have required a team a few years ago. That's a fundamental shift in the cost structure.

Second, infrastructure costs have become astonishingly cheap. You can run a music app backend on cloud services for a few hundred dollars a month, even at decent scale. In 2011, that would have cost thousands.

Third, distribution is free. There's no gatekeeper deciding whether your app is "important" enough to exist. You post it on GitHub, you put it on the web, you tell your friends. If people want it, they find it.

Fourth, and this is important, niche users are willing to pay for things that respect their specific needs. A music nerd who uses Bandcamp, Last.fm, and three different streaming services simultaneously will happily pay for an app that works the way they actually use music. They might not be willing to switch to yet another streaming service, but paying a small subscription for better tools? That's different.

The math works something like this. If Parachord gets 10,000 users and charges

Compare that to Spotify, which needs hundreds of millions of users just to exist. Spotify can't afford to optimize for small groups of music nerds because they're a rounding error in their user base. But Parachord can be 90% of its entire product.

Vibe-Coding Beyond Music: What This Means for Other Industries

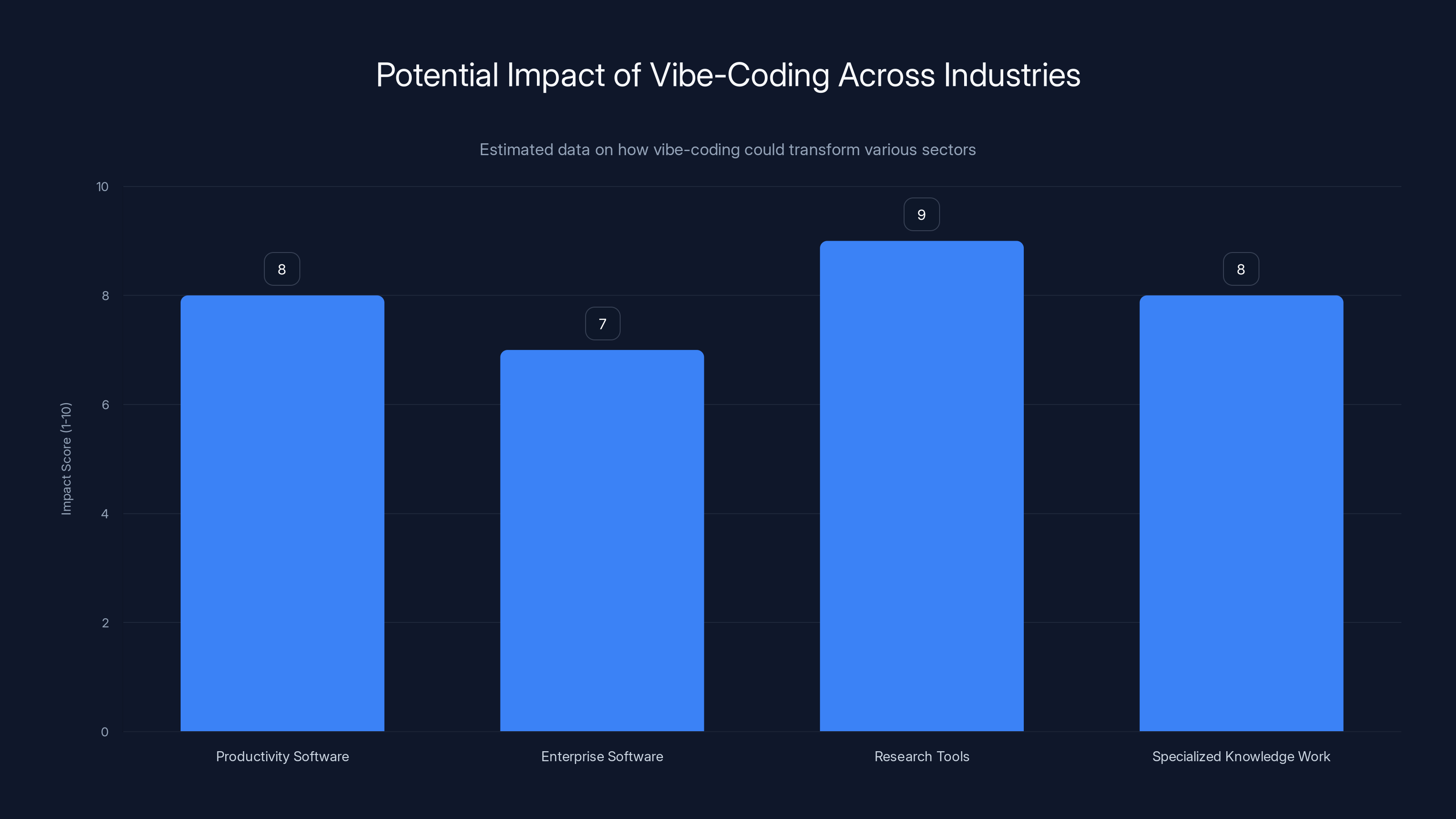

While Parachord is a music app, the implications of vibe-coding go much broader. This development pattern is starting to reshape how software gets built across multiple industries.

Consider productivity software. Most productivity tools are built for generic workflows. But professionals in specific fields have very specific needs. A freelance accountant needs something different from a freelance designer needs something different from a freelance writer. The big productivity platforms try to accommodate everyone with plugins and settings. But what if small teams could build tools specifically optimized for their niche?

With vibe-coding, a freelance accountant could partner with an AI to build exactly the tool they need, customized to how they actually work. Not a generic spreadsheet. Not accounting software designed for firms with dozens of employees. But a tool that works the way this specific person actually does accounting.

Or consider enterprise software. Most enterprise tools are massive, complex, and take months to implement. But what if companies could build custom tools that integrate with their specific tech stack? You point an AI at your existing systems, describe what you need, and get a working integration in weeks instead of months.

Or consider domain-specific tools for research, scientific work, or specialized knowledge work. Academics in niche fields struggle to find tools built for them. But the addressable market for those tools is sometimes only a few thousand people globally. That's way too small to justify traditional software development. But with vibe-coding, it becomes viable.

The fundamental shift is this: software development is becoming democratized. Not in the sense that anyone can now code, but in the sense that product managers, domain experts, and people with deep understanding of specific problems can now build the tools they need without hiring a development team.

That's genuinely transformative. It means we're likely going to see an explosion of domain-specific tools that are vastly better at their specific job than generic alternatives. It means niche use cases will finally get adequate solutions. It means the next generation of software might not come from Silicon Valley at all.

Music Recommendation Algorithms: Where Parachord Differs

Let's talk about recommendation algorithms, because this is where Parachord actually uses AI in a meaningful way that's different from how Spotify does it.

Spotify's recommendation engine works by analyzing patterns in your listening history. If you listen to a lot of indie rock, Spotify will recommend more indie rock. If your listening suggests you like melancholic singer-songwriters, Spotify will serve up similar artists. It's remarkably effective. Spotify's recommendation engine is probably the company's most valuable competitive advantage.

But there's a problem with that approach, especially for music nerds. If you're someone who's been meticulously tracking your listening on Last.fm for 15 years, you probably already know all the obvious recommendations. You've already found the obvious artists in your genre. You've already explored the obvious adjacent genres. What you actually want is something deeper. You want recommendations that are informed by your taste but that go in unexpected directions.

Parachord approaches this differently. It uses AI to analyze your Last.fm data not just to identify patterns, but to understand the specific dimensions of your taste. Why do you like certain songs? Is it the production style? The vocal timbre? The lyrical content? The historical context? The AI can be trained to make those distinctions.

Once it understands those dimensions, it can search for songs that are novel but still aligned with your tastes. It can find songs you've genuinely never heard before that match your taste profile in ways the Spotify algorithm wouldn't think to look.

There's another way Parachord uses AI that's interesting: collaborative filtering across service boundaries. Last.fm has tracked millions of users' listening habits for years. If you and another Last.fm user have similar taste profiles, and they've listened to something you haven't, that's a high-signal recommendation. Parachord can use AI to identify those patterns and surface recommendations based on them.

None of this is more "advanced" than Spotify's algorithm in a purely technical sense. Spotify has massive resources devoted to recommendation science. But it's optimized differently. Spotify optimizes for engagement and stickiness. Parachord optimizes for relevance to people who already know what they like.

This is the kind of thing that's hard to do at scale, but easy to do well for a niche audience. Spotify can't spend engineering resources on making recommendations better for the 0.1% of users who want obscure indie folk recommendations. But Parachord can make that its entire focus.

Niche apps can sustain themselves with as few as 10,000 users, generating $50,000 monthly, while major platforms require millions of users to achieve similar sustainability.

The Social Layer: Rediscovering Music Through Friends

One of the most underrated aspects of pre-streaming music culture was the social layer. You'd go to a friend's house, listen to their record collection, and discover new music. You'd watch MTV and find new artists. You'd read music magazines and get recommendations. Music discovery was inherently social.

Streaming flattened that. Instead of discovering music through friends, you discover it through algorithms. Spotify's "Discover Weekly" is generated just for you, based on your personal listening history and aggregate user behavior. It's powerful, but it's also isolating. You're not discovering music because your friend loves it. You're discovering it because a machine learning model thinks you'll like it.

Parachord tries to reconstruct that social layer. You can follow other users and see what they're listening to. You can follow tastemakers and musicians on social platforms like Bluesky. You can create collaborative playlists with friends. You can contribute to playlists that your friend started.

This matters because social recommendations are fundamentally different from algorithmic recommendations. When a friend recommends a song, there's context. There's relationship. There's often a story: "I heard this artist at a festival and was blown away" or "This song reminds me of when we drove cross-country" or "This is my new favorite song." That context makes the recommendation more meaningful.

Parachord is trying to bring back some of that context. When you follow a DJ on social media and Parachord turns their posts into playlists, you're getting recommendations through a social relationship, not an algorithm. When you create a collaborative playlist with friends, you're making music discovery a shared experience.

There's also something interesting happening with Bluesky and decentralized social platforms. Many music enthusiasts have migrated there from Twitter. They talk about music, share recommendations, follow DJs and musicians. Parachord taps into that energy and transforms it into actual music you can listen to.

This social approach is also more resilient to filter bubbles. Algorithmic recommendations can get stuck in patterns where you're only recommended variations on the same theme. When you're getting music recommendations from actual people you follow, and those people have diverse tastes, you're naturally exposed to more variety.

The Bandcamp Factor: Indie Music Needs Better Tools

Bandcamp gets special treatment in Parachord, and for good reason. Bandcamp has become the primary platform for independent musicians and music fans who actually want to support artists directly. But Bandcamp exists in a strange relationship with streaming services.

When you buy a song on Bandcamp, you own it. You get the files. You can use them how you want. But those files don't automatically integrate with your streaming experience. If you want to listen to a Bandcamp purchase on Spotify, you'd have to rip it to local files and upload it to Spotify, which is tedious and technically awkward.

Parachord unifies this. You can buy songs on Bandcamp, and Parachord will include them in your library. When you create a playlist that includes a Bandcamp purchase, everyone in the collaborative playlist can listen to it, regardless of their streaming service. It's treating Bandcamp not as an isolated silos but as part of your unified music library.

This matters because Bandcamp has become genuinely important to the music ecosystem. For many indie artists, Bandcamp is their primary revenue source. For music fans who care about artist compensation, Bandcamp is where they spend money instead of using streaming services that pay fractions of cents per play.

Bandcamp's existence creates a problem for music nerds. They're buying music there, but that music doesn't integrate with their streaming life. They end up maintaining two separate music libraries: the streaming stuff and the purchased stuff. Parachord attempts to eliminate that split.

There's another dimension to this: Bandcamp has become important culturally in certain music genres and communities. Electronic musicians, experimental artists, indie rock bands, hip-hop producers, lo-fi creators—many of them have moved to Bandcamp as their primary platform because it aligns with their values and actually pays them. Parachord's focus on Bandcamp signals that it understands this shift.

Last.fm Integration: Your Personal Music Database

Last.fm is this weird service that's been around for over 20 years. It's basically a music tracking service that scrobbles every song you listen to, building up a lifetime database of your music taste. It's not a streaming service. It's not a discovery tool. It's just a record.

For music nerds, Last.fm is invaluable. You can see what you listened to in 2008. You can identify your top artists by year. You can see trends in your taste. You can compare your music taste with friends. But it's pretty isolated. Last.fm data doesn't feed back into any major streaming recommendation engine.

Parachord integrates Last.fm data directly. This creates some interesting possibilities. The service can analyze your full listening history, not just recent activity. It can identify artists you've been listening to consistently over years. It can surface songs you might have loved but forgotten about. It can even do things like recommend songs similar to ones you loved in 2015 based on your current taste.

For someone who's been using Last.fm for a decade, having that data actually be useful in your music discovery is genuinely powerful. It's like unlocking a treasure trove of information that's been sitting dormant.

There's also a social component. You can see what other Last.fm users with similar taste profiles have listened to. You can find communities of people who share your specific combination of interests. Last.fm's social features are pretty limited, but Parachord can extend them by making recommendations based on what similar users are listening to.

Vibe-coding is poised to significantly transform industries by enabling customized tool development, with research tools and specialized knowledge work seeing the highest potential impact. Estimated data.

The Parachord Beta: What Exists Today

It's important to be clear about Parachord's current state. This isn't a finished product. Herskowitz is the first to admit that what's available now is experimental and unstable. There are bugs. There are missing features. It's not something your grandmother should try to use.

But that's actually fine. The existence of the beta is less about having a finished product and more about proving the concept works. Herskowitz has demonstrated that you can rebuild a complex music application in a few weeks with AI assistance. He's demonstrated that there's interest in this kind of music discovery tool. And he's demonstrated that even in its rough form, it's useful enough that people want to use it.

The beta is accessible to people who are interested in testing it, but it's not a mainstream product. Herskowitz is cautious about scaling too fast. He's learned from experience that the hard part isn't building the app—it's building a sustainable business and community around it.

What's interesting about the beta is what it says about viability. If Herskowitz had tried to raise venture capital for this, he would have been laughed out of the room. It's a niche product in a consolidate market. But because he could build it with AI assistance for minimal cost, he didn't need venture capital. He could just build it and see if people wanted it.

That's a fundamentally different way of developing software. It's not "get funding, build product, raise money again." It's "build, iterate, see what people think, refine." It's much more lean, and it opens the door to products that wouldn't have existed under the old financial model.

The Streaming Wars: Why Consolidation Happened

To understand why Parachord is necessary, you need to understand why the streaming market consolidated in the first place. And that story is about money, licensing, and the brutal mathematics of the music industry.

When streaming first arrived, there were dozens of services. The thinking was that different companies could compete on features, interface, or community. But the economics didn't work out that way. Music licensing is expensive. The big record labels demand guaranteed minimum payments, sometimes in the millions of dollars. You have to pay them upfront, before you have any users.

So the streaming companies competed on money, not features. Spotify spent billions acquiring exclusive licensing deals and exclusive content. Apple used Apple Music as a bundling incentive for Apple devices. Amazon used it as an incentive for Prime membership. YouTube Music captured users because they already use YouTube.

Smaller services couldn't compete in this arms race. Tidal tried to differentiate on hi-fi audio quality and artist payouts, but that wasn't enough. MOG got acquired. Rdio went bankrupt. Grooveshark had legal problems and shut down. By the early 2020s, the consolidation was basically complete. Spotify, Apple, Amazon, and YouTube essentially controlled the market.

Once the market was consolidated, the winners could stop competing on features and just optimize for engagement and retention. They could lower payouts to artists. They could use their scale to negotiate better licensing terms. They had no incentive to innovate. Why would they? What are you going to do, switch to the other streaming service that works basically the same way?

Parachord doesn't try to compete in that space. It's not trying to negotiate better licensing deals. It's not trying to be a better streaming service. Instead, it's working within the consolidated market to solve problems that the consolidated services have no incentive to solve.

The Sustainability Question: Can Niche Apps Actually Survive?

So here's the uncomfortable question: can Parachord actually succeed as a business? Is there a sustainable model for a niche music app in 2025?

The answer is probably yes, but with caveats. Parachord doesn't need millions of users to be viable. It needs thousands of dedicated users who will pay for the service. Music enthusiasts are exactly the kind of people who pay for tools that respect their specific needs.

There are a few possible revenue models. Subscription is the obvious one—$5-10 per month. That's viable if you have a few thousand paid users. There's also the possibility of premium features. A free tier that does basic stuff, and a pro tier with advanced features. There's even the possibility of selling data or insights to the music industry, though Herskowitz would likely be philosophically opposed to that.

The real question isn't whether the revenue exists. It's whether Herskowitz wants to build a business around this, and whether the regulatory environment will allow it. Music licensing is complicated. Using AI to scrape social media and turn posts into playlists might create legal questions. Integrating across multiple services could run into terms-of-service issues.

But these are obstacles that can be solved. They're not fundamental impossibilities. And the existence of viable revenue models plus proven demand plus low development costs equals a business that can work.

The bigger question is sustainability as a product, not just as a business. Will Parachord still work well if the APIs it depends on change? What if Spotify or Apple Music change their terms and no longer allow aggregator apps? What if social platforms start restricting scraping in ways that would break the DJ feed feature?

These are real risks. But they're risks that every integrator faces. And the agility that Parachord has—being built by a small team with AI assistance—actually gives it advantages in responding to changes. It can pivot faster than larger companies.

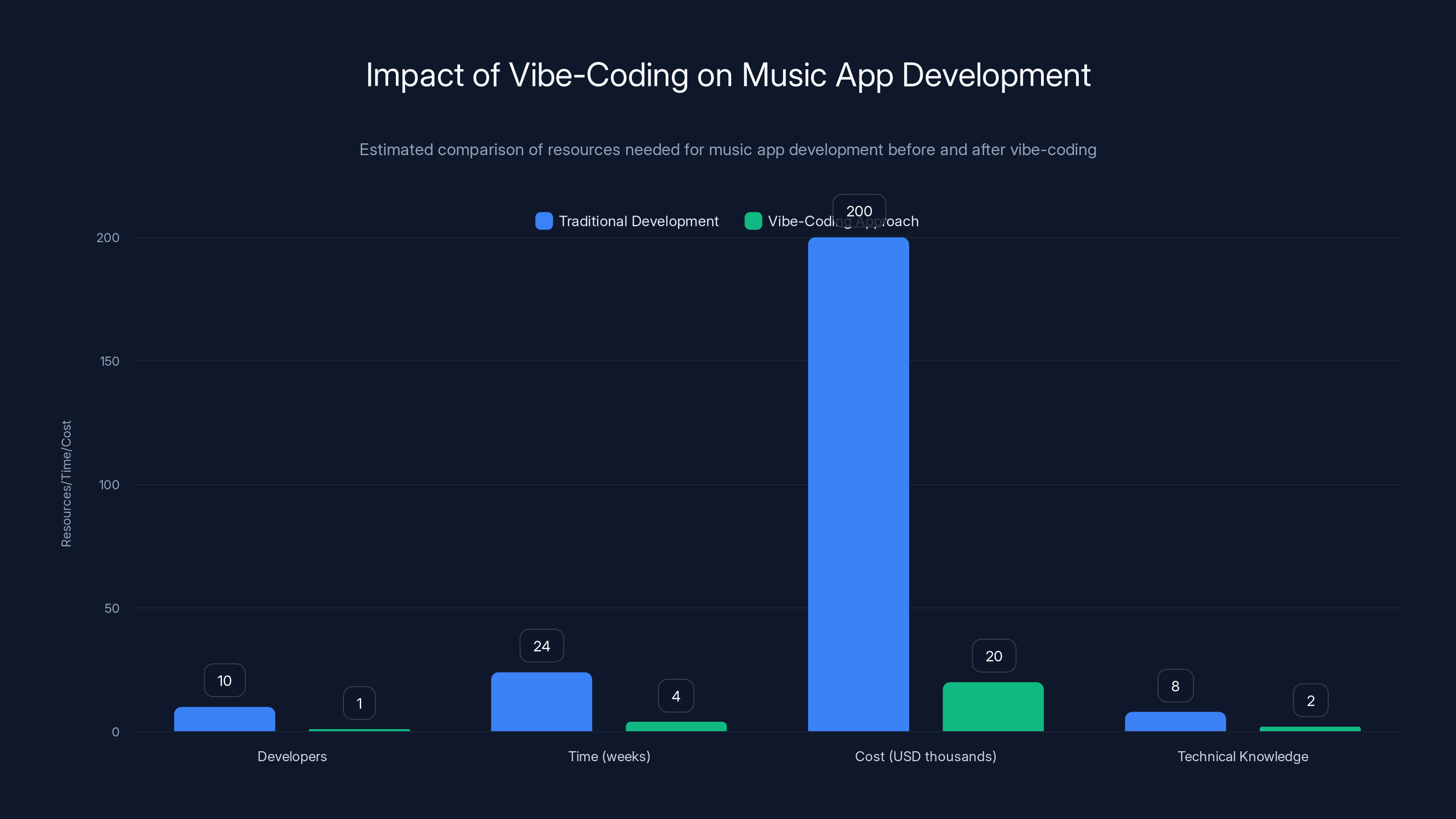

Vibe-coding significantly reduces the number of developers, time, cost, and technical knowledge needed for music app development. Estimated data.

What This Means for the Future of Music Apps

Parachord is important not because it's going to replace Spotify. It's not. Spotify is enormously popular and incredibly well-executed. What Parachord signals is that there's room in the market for alternatives that aren't trying to be everything to everyone.

We're likely going to see more apps like Parachord. Apps built for specific audiences with specific needs. Some will focus on jazz enthusiasts. Others will focus on electronic music. Some might focus on music discovery for DJs. Others might focus on community and social sharing. None of them will have tens of millions of users. But all of them can be viable businesses serving their specific communities.

This is a return to a pre-consolidation pattern. Back before Spotify, there were tons of music apps and tools. Different communities had tools built specifically for them. That diversity was actually valuable. You lost something when everything consolidated onto one or two platforms.

The resurrection of niche music apps would be good for the music ecosystem overall. It would be good for musicians because diverse platforms mean more ways to be discovered. It would be good for fans because they'd have tools that actually work the way they use music, instead of tools that work how the platform wants them to use it. And it would be good for innovation because niche apps can experiment in ways that massive platforms can't.

AI development tools are the enabler here. But the opportunity has always existed. It's the ability to build cheaply and quickly that's new. That capability is going to unleash a wave of specialized software across many industries, and music apps are just the beginning.

The Bigger Implications: Platform Fragmentation and User Choice

There's a larger story here about computing platforms and user choice. For the past 15 years, we've seen consolidation across almost every category of software. Social media consolidated onto Facebook, then fragmented again. Search is still Google. Email is Gmail, Outlook, and others, but not really competitive. Video is YouTube and Netflix. Music is Spotify, Apple, Amazon, and YouTube Music.

This consolidation brought benefits. Each of these consolidated platforms got really good at what they do. Spotify's recommendation engine is genuinely impressive. Apple's integration across devices is seamless. But the costs are real. You're locked into the platforms' choices about how you interact with content. You're subject to their algorithmic filtering. You're isolated from people using other services.

The emergence of aggregation and integration tools like Parachord suggests an alternative future. Not one where Spotify loses market share, but one where applications can exist on top of the consolidated platforms. Apps that let you move between services. Apps that aggregate content from multiple sources. Apps that let you define your own experience instead of accepting the platform's default.

This is the pattern that happened with the web. Multiple browsers let you access the same websites. Multiple email clients let you access Gmail, Outlook, and other services. The standardization of underlying protocols (HTTP, SMTP) allowed a whole ecosystem of tools to exist on top of them.

Music streaming could go in a similar direction. If there were open standards for music library data and recommendations, then we could see genuine competition in the application layer, even if Spotify, Apple, and Amazon controlled the underlying streaming infrastructure.

Parachord can't force that to happen. But its existence as a proof of concept that this kind of application can be built suggests that the underlying demand is there.

Building with AI: The Broader Software Development Shift

Let's zoom out and think about what Parachord's creation says about software development more broadly. We're in the middle of a fundamental shift in how software gets built, and it's worth understanding the implications.

For the past 50 years, software development has been a bottleneck. If you had an idea for an application, you needed to hire developers. Developers were expensive and in short supply. You needed to spend months on planning and specification before you could start building. You needed to manage a team. You needed to handle all the coordination and communication issues that come with teams.

AI is starting to remove that bottleneck. You can describe what you want to build. An AI can help you build it. You don't need perfect specifications. You don't need to understand all the technical details. You can learn as you go, asking the AI questions, refining your vision.

This is genuinely revolutionary. It means ideas that couldn't exist before—because they didn't have a big enough addressable market to justify hiring a development team—can now exist. It means expertise and execution are becoming decoupled. You don't need to be a programmer to build software anymore. You need vision and persistence. The execution can be handled by AI.

But this creates new challenges. If everyone can build software, how do you discover the good stuff? How do you know what to trust? If the barrier to entry disappears, do you get more innovation, or just more noise?

These are open questions. But Parachord suggests at least one answer: in a world where anyone can build, good products are still discovered through genuine need and community. Parachord got attention not because of marketing but because music nerds have been looking for something like it for over a decade. There's genuine demand.

Another implication: the economics of software companies change dramatically. If you don't need a team of developers, then you don't need to scale to massive user numbers to be profitable. This could be good—it means more diverse software serving more diverse communities. It could be bad—it means more fragmentation and potential for abandoned projects.

Potential Challenges and Limitations

It's worth being realistic about what Parachord faces. There are genuine challenges that could prevent it from succeeding, regardless of how good the product is.

First, there's the terms-of-service issue. Spotify, Apple Music, and other services have terms that might not allow applications like Parachord to exist. If you're connecting to their APIs and surfacing their data in your own application, you might be violating their terms. They could shut off access. They could send cease-and-desist letters. They could make changes to their APIs specifically to break aggregators.

Second, there's the music licensing question. Parachord itself isn't a music service—it doesn't store or stream music. But it's directing traffic and facilitating discovery across multiple licensed services. There could be licensing complications that aren't immediately obvious.

Third, there's the competition problem. Even if Parachord builds a great product for music nerds, Spotify or Apple could build a similar feature into their own apps. They have the resources and the user base. At that point, why would people use Parachord instead of using the feature built into their primary music service?

Fourth, there's the network effect problem. Music services are valuable because of the network they connect. The value of a music service increases as more people use it. Parachord doesn't have that advantage. It's an aggregator on top of existing services. It can't create the kind of network effects that draw people in.

Fifth, there's sustainability. We discussed this earlier, but it bears repeating. A few thousand users can support a niche app. But maintaining that product, fixing bugs, adding features, and responding to API changes requires ongoing engineering effort. Will Herskowitz's enthusiasm for the project sustain through the inevitable periods when it's not fun to work on?

These aren't insurmountable challenges. But they're real, and they're worth understanding if you're thinking about building something similar.

FAQ

What exactly is vibe-coding?

Vibe-coding is a development approach where you describe the general "vibe" or feeling of what you want to build to an AI, rather than providing detailed technical specifications. The AI then helps you implement it, handling technical details and iterations based on conversational feedback. It's particularly effective for applications that integrate existing services and APIs, like Parachord.

How does Parachord unify music from different streaming services?

Parachord connects to your accounts on multiple streaming services (Spotify, Apple Music, Bandcamp, Last.fm, etc.) and presents a unified interface. When you search for a song, it checks all connected services to find where it's available. You can create playlists that pull from multiple services, and the app will play tracks from whichever service has them. This allows friends using different services to share music easily.

Can I actually use Parachord today?

Parachord is still in early experimental stages. Beta builds are available for people interested in testing it, but it's not a finished product. There are bugs, missing features, and the interface is still being refined. It's designed for people who are comfortable with unstable software and want to help test the concept.

Why is Bandcamp integration important to Parachord?

Bandcamp has become the primary platform for independent musicians and fans who want to directly support artists. Parachord integrates Bandcamp purchases into your unified library, allowing songs you've bought to be part of your music collection alongside your streaming subscriptions. This eliminates the disconnect between purchased and streamed music.

How much would Parachord cost if it becomes a full product?

Parachord's creator hasn't announced final pricing, but similar niche apps typically cost $5-10 per month. The business model would likely be based on monthly subscriptions from dedicated users who find value in unified music discovery and social features. There could also be a free tier with limited functionality.

Is Parachord legal? Won't Spotify shut it down?

That's an open question. Parachord operates through official APIs and respects terms of service, but aggregator apps exist in a legally gray area. Streaming services could theoretically restrict access to their APIs. However, the existence of Last.fm and similar music tracking services suggests there's legal precedent for third-party music applications, at least if they follow platform guidelines.

How is Parachord different from Spotify?

Parachord isn't trying to replace Spotify. It's designed for music enthusiasts who use multiple services and want unified discovery. Spotify optimizes for broad appeal and algorithmic discovery for general audiences. Parachord optimizes for people who buy music on Bandcamp, track their listening on Last.fm, and follow DJs on social platforms. They serve different audiences with different needs.

Will other vibe-coded music apps emerge?

Likely yes. If Parachord succeeds in demonstrating that there's demand for niche music apps, we'll see others follow. Different creators might build apps optimized for specific music communities—jazz enthusiasts, electronic music producers, hip-hop fans, or other groups. The low development cost makes this viable in ways it wasn't five years ago.

What does this mean for Spotify's dominance?

Parachord doesn't threaten Spotify's core business. Most Spotify users are satisfied with the service and don't need additional tools. Parachord targets a small segment that wants functionality Spotify doesn't provide. It's more likely that we'll see a fragmented ecosystem where Spotify dominates for casual listeners, and niche apps serve specialized communities.

Can someone build a music app like Parachord today?

Yes, absolutely. If you understand the music niche you want to serve, you can describe it to an AI like Claude, and it can help you build an app. The development cost is minimal compared to traditional software development. The real challenge isn't building anymore—it's finding a sustainable business model and solving licensing/legal issues specific to music.

Conclusion: The Future of Music Software and Beyond

Parachord isn't going to dethrone Spotify. It's not going to revolutionize how billions of people listen to music. But it represents something genuinely important: proof that you don't need to be a massive corporation to build software that solves real problems for specific communities.

The music app market seemed dead. Every conceivable competitor had either been acquired, gone bankrupt, or been outmaneuvered by the consolidated platforms. The era of alternative music apps felt like it had passed. And then Herskowitz looked at an old project from 2011, fed it to an AI, and in a few weeks, created something that the industry thought was impossible: a new music app that works and that people actually want to use.

What makes this moment interesting isn't Parachord itself. It's what Parachord makes possible. It demonstrates that development constraints that seemed absolute ten years ago are no longer relevant. A solo product manager with no traditional coding experience can build complex software. That changes everything.

We're going to see this pattern repeat across software categories. Music discovery apps for niche communities. Productivity tools built for specific professions. Scientific software built by researchers for researchers. Integration tools that connect disparate services in ways the services themselves never will. None of these will be massive, venture-backed companies. Most will be small projects built by passionate people solving problems they care about.

Some of these projects will fail. Some will be abandoned. But enough will succeed that the software landscape of 2030 is going to look radically different from today's. Not because AI can build better software than humans. But because AI lets humans build software at all.

For music specifically, we might be entering a new era. Not a return to the days of iTunes, where one application dominated. But a return to diversity. Different apps for different communities. Apps that respect user choice instead of locking them in. Apps that work with the existing services instead of trying to replace them.

Parachord is just the first of what will probably be many. Watch this space. The future of music software is being built right now, one vibe-coded application at a time.

Key Takeaways

- Vibe-coding uses AI to democratize software development, enabling non-developers to build complex applications in weeks instead of months

- Parachord unifies music across Spotify, Apple Music, Bandcamp, and Last.fm, solving problems that consolidated platforms ignore

- Development costs have plummeted from 2,500 annually with modern AI tools, making niche apps economically viable

- The music streaming market consolidated completely around Spotify, but that created opportunity for specialized apps serving passionate music communities

- Social and human-driven music discovery is making a comeback through apps that integrate DJ feeds, Last.fm data, and collaborative playlists

Related Articles

- Apple Music's New Features vs Spotify: What Changed in 2025

- Sky TV Price Hike April 2025: HBO Max Changes and What You Should Do [2025]

- 4K TV Recorder with Freely Streaming: The Ultimate Guide [2025]

- Spotify & SeatGeek Integration: How Artists Sell Tickets [2025]

- AI Coding Agents Memory Problem: How Intelligent Rules Systems Fix Amnesia [2025]

- Laurie Spiegel on Algorithmic Music vs AI: The 40-Year Evolution [2025]

![Vibe-Coded Music Apps: How AI is Rebuilding the iTunes Future [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/vibe-coded-music-apps-how-ai-is-rebuilding-the-itunes-future/image-1-1771521246510.jpg)