Why The Supreme Court's Tariff Ruling Won't Lower Car Prices—And What Actually Matters

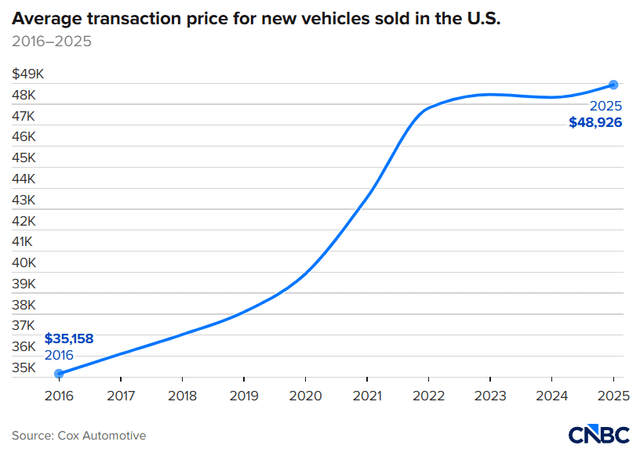

It's never been more expensive to buy a new car in America. The average transaction price for a new vehicle hit

So when the Supreme Court made headlines by ruling against certain tariffs, you might've thought relief was coming. Maybe car prices would finally start trending downward. Maybe that EV you've been eyeing would become attainable again. Here's the thing though: the ruling doesn't change much. Not for cars, anyway. Not for your wallet.

The automotive industry sits at this bizarre intersection of politics, trade law, supply chain complexity, and raw economics. When you zoom out and look at why cars cost what they do today, tariffs are just one piece of a much larger, messier puzzle. And a lot of that puzzle isn't going anywhere, regardless of what the courts decide.

Let's break down what actually happened, why it matters less than the headlines suggest, and what's really keeping car prices so stubbornly high.

The Supreme Court Ruling: What Changed and What Didn't

On Friday, the Supreme Court did something that surprised a lot of people who follow trade policy closely. It basically said the president can't use a particular law—the International Emergency Economic Powers Act, or IEEPA—to slap tariffs on countries just because the trade deficit is big. That's a meaningful legal constraint on executive power as reported by SCOTUSblog.

The Trump administration had been pretty aggressive with IEEPA. They used it to justify tariffs on a bunch of countries around the globe, claiming these huge trade deficits were some kind of national security emergency. They also used it to apply tariffs on Canada, China, and Mexico, calling migration and drug flows emergencies that justified trade restrictions. The Court basically said: no, that's not how this works. You can't stretch "national emergency" to mean "trade deficit." That's a real limit on presidential authority as noted by Cato Institute.

Here's where it gets important for cars though: those IEEPA tariffs? They weren't even the main tariffs affecting the automotive industry. Most of the damage comes from a completely different law that's still fully in effect. We're talking about Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962. That's old law. Like, Kennedy-era old. It allows the president to apply tariffs on imports that "threaten to impair" national security.

Under Section 232, the administration put 15% tariffs on cars built in Europe, Japan, and South Korea. These remain fully in effect post-Supreme Court ruling. The same goes for tariffs on steel, aluminum, and copper—all the raw materials that go into making cars. These came under Section 232 as well. So when you look at what's still hitting the auto industry hard, the Supreme Court ruling barely touched it.

It's a bit like telling someone their house is on fire, then spraying one room with a garden hose while the rest of the structure burns. Technically you did something, but the problem persists.

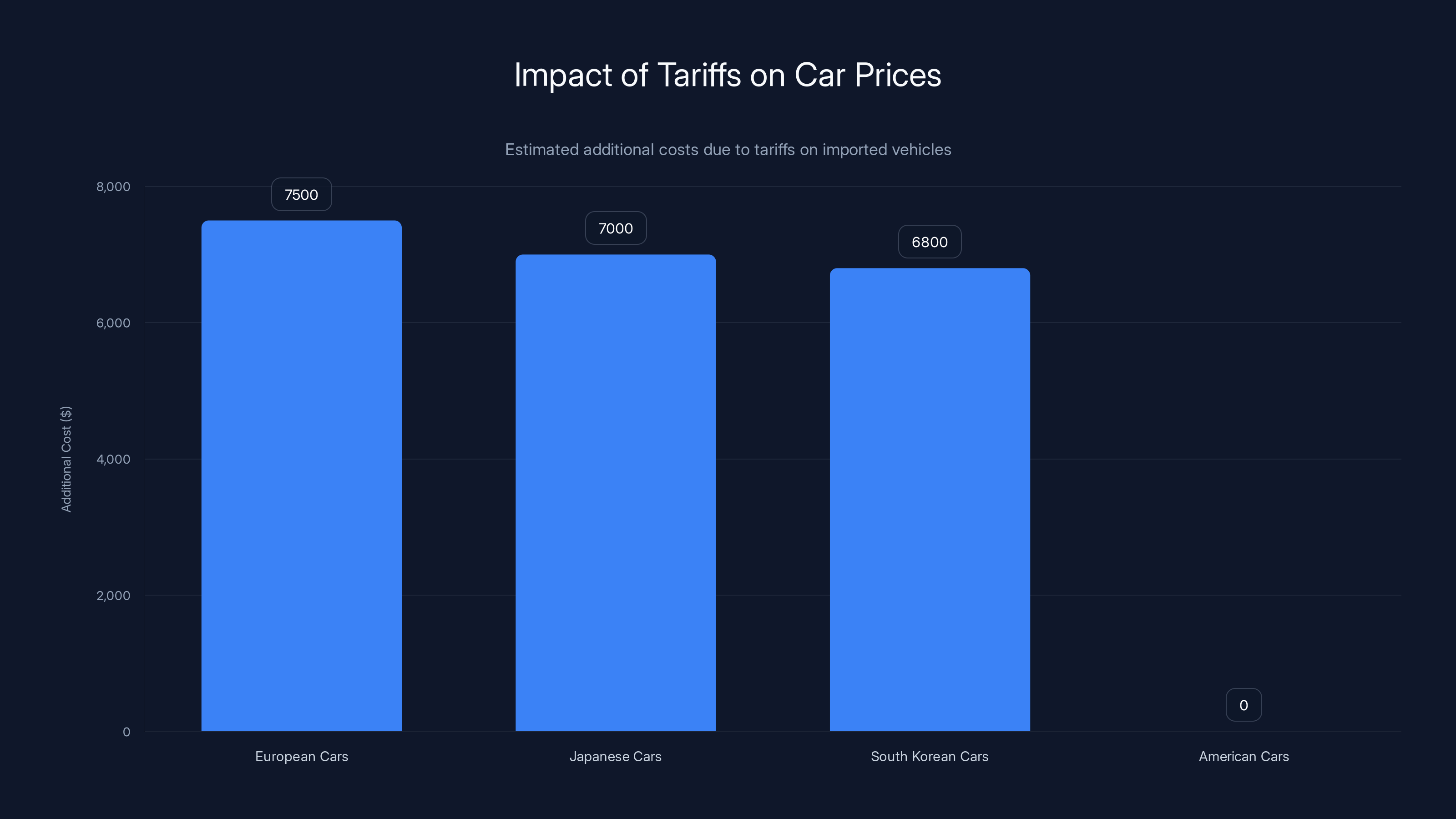

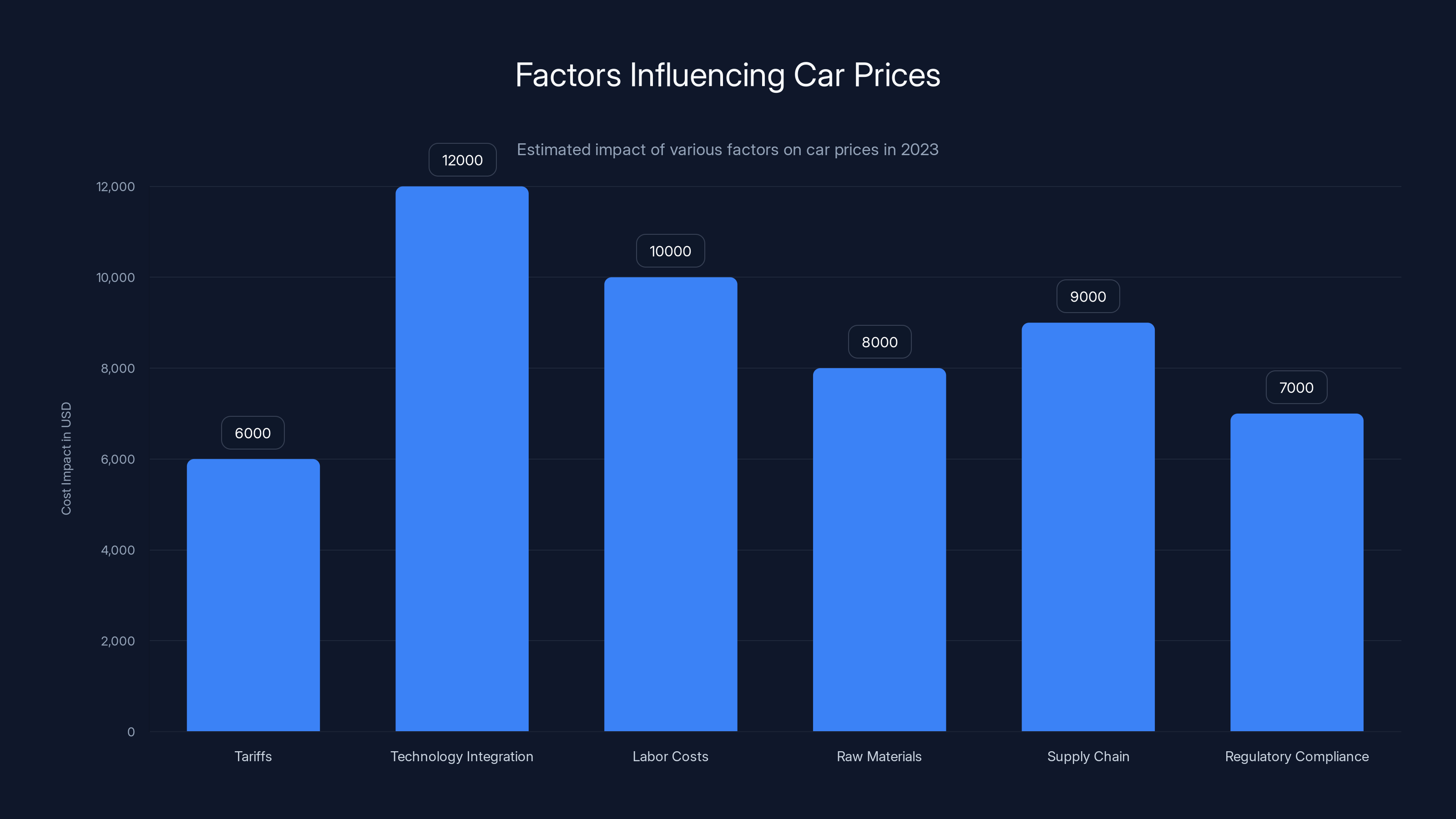

Estimated data shows that tariffs can add

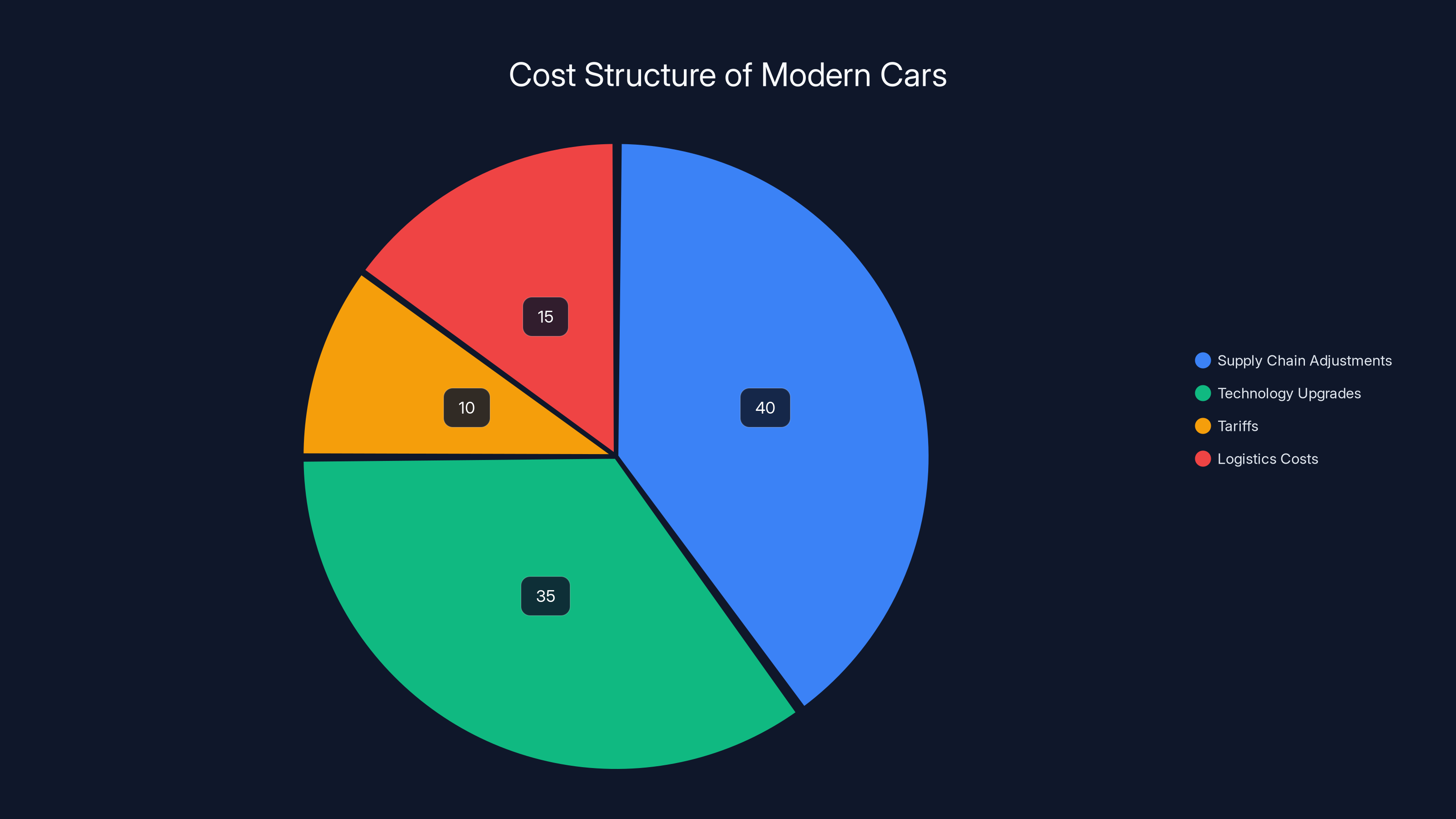

The Real Cost Structure of Modern Cars

Here's what industry analysts keep pointing out: tariffs are real. They matter. But they're not the main reason a new car costs $10,000 more than it did five years ago. That's not some minor rounding error. That's a fundamental shift in the entire cost structure of vehicle production.

Let's talk about what's actually pushing prices up. Start with the supply chain. The pandemic broke global manufacturing in ways that are still reverberating. Semiconductor shortages particularly hammered the auto industry. You can't make a modern car without chips—lots of them. Engines need chips. Infotainment systems need chips. Climate control systems need chips. Anti-lock braking systems need chips. When chip supplies dried up, automakers had to choose: either shut down production lines or pay premium prices for the chips they could source. Most chose the latter.

That shortage phase is technically over, but the scars remain. Parts suppliers restructured their operations. Shipping and logistics costs stayed elevated. Some manufacturers diversified their supply sources, which sometimes means higher costs initially. The supply chain is more resilient now, but resilience isn't free.

Then there's the technology factor. Cars today aren't the cars of 2019. They're packed with features that didn't exist back then. Advanced driver assistance systems—that's technology that makes a car more expensive. Bigger infotainment screens with wireless connectivity. Sophisticated battery management systems if it's a hybrid or EV. Thermal management systems for battery packs. Over-the-air update capabilities. These aren't luxury add-ons anymore; they're standard equipment.

Let's be concrete. A typical new car in 2019 might've had a 7-inch touchscreen in the center console. Today's base models often come with 8-inch, 10-inch, or larger screens with full smartphone integration. That costs more. It weighs more. The wiring harnesses are more complex. The software integration is more elaborate. Multiply that kind of upgrade across dozens of systems in a vehicle, and you're looking at thousands of dollars in added cost per car.

Raw materials costs haven't gone down either. Steel prices have remained elevated compared to the 2015-2019 period. Aluminum prices fluctuate but haven't returned to historical lows. Labor costs have gone up significantly. The UAW struck a major deal that increased wages for workers, and those costs get passed through to consumers. Battery materials—lithium, cobalt, nickel—spiked when demand for EVs surged, even though prices have come down from their peaks according to Yale's Budget Lab.

All of this—supply chain resilience costs, technology additions, raw materials, labor—these are structural issues. They're not tariffs. They're not regulatory. They're just the cost of making cars in 2025.

The Automakers' Pricing Strategy: Absorbing vs. Passing Through

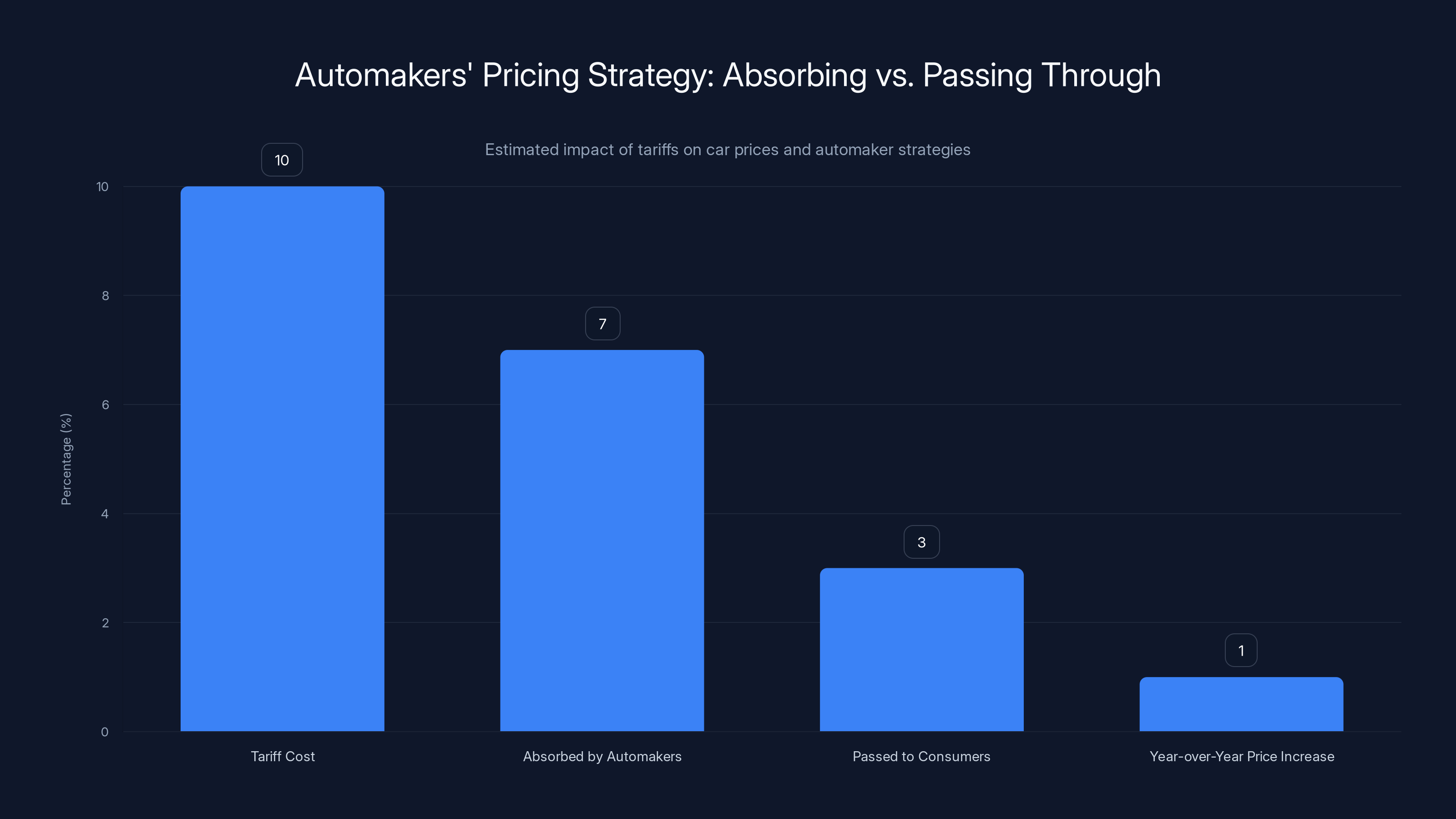

Here's something really interesting that industry analysts have noticed: automakers haven't passed on as much of the tariff cost to consumers as you'd expect. They've been absorbing some of the hit themselves. This is partly strategic and partly because they have to.

Why? Because car demand is price-sensitive. You hit people with a $2,000 tariff-driven price increase, and they don't say "okay, I'll pay it." They say "you know what, I'll keep my 2015 Honda Accord for another two years." Or "maybe I'll lease instead of buy." Or "maybe I don't need a new car after all." Automakers know this. They've modeled the elasticity. They understand that beyond a certain price point, you lose sales volume, and volume matters.

So instead of full pass-through, manufacturers have been eating part of the cost. They've done this partly through efficiency improvements, partly through supplier negotiations, and partly just by accepting smaller margins. Jessica Caldwell from Edmunds made the point that prices have only gone up 1% year-over-year recently, despite ongoing tariff pressures. That's actually remarkable when you think about all the other cost pressures.

But here's the catch: "for now" is the operative phrase. Caldwell and other analysts note that if tariffs stay in place and costs keep building, automakers won't be able to sustain this indefinitely. You can only absorb so much before your business model breaks. If they have to choose between accepting margins of 3% instead of 6%, versus losing market share to imports that are suddenly much cheaper, they'll start shifting costs to consumers.

This is the real threat that the Supreme Court ruling doesn't address. Even with some IEEPA tariffs off the table, the Section 232 tariffs remain. That's still pressure. And the longer that pressure persists, the more it will flow through to prices.

Automakers are absorbing 7% of the tariff costs, passing only 3% to consumers, resulting in a 1% year-over-year price increase. Estimated data based on industry analysis.

Section 232 and National Security: The Legal Framework That Stays

To understand why the Supreme Court ruling doesn't help consumers much, you need to understand Section 232 and how it's different from IEEPA.

Section 232 dates back to 1962. It was designed to let the president protect domestic industries when imports threatened to undermine national defense capacity. The logic was: if we're dependent on foreign steel, and a war breaks out, and suddenly we can't access that steel, we're vulnerable. So the law lets the president apply tariffs to protect domestic capacity.

Here's the thing about Section 232: the "national security" bar is incredibly low and incredibly broad. It's not a technical definition. It's more like a general principle that the president can invoke. And courts have historically given the president wide latitude in determining what constitutes a national security threat.

Why does this matter? Because the Trump administration interpreted Section 232 to apply to automobiles, steel, aluminum, copper, and various other imports. Those tariffs are still there. The Supreme Court ruling doesn't touch them because Section 232 is a different legal authority than IEEPA.

This is actually pretty important from a policy perspective. It means that even if future administrations wanted to roll back tariffs, they'd need Congressional action or a different Supreme Court ruling or a dramatic interpretation shift. Section 232 authority is broad. It's been tested. It's been upheld.

For car buyers, this translates to: the tariffs that actually affect your car purchase are probably staying. The Supreme Court didn't swing an axe at the tariff regime. It tweaked one part of it. The main structure remains.

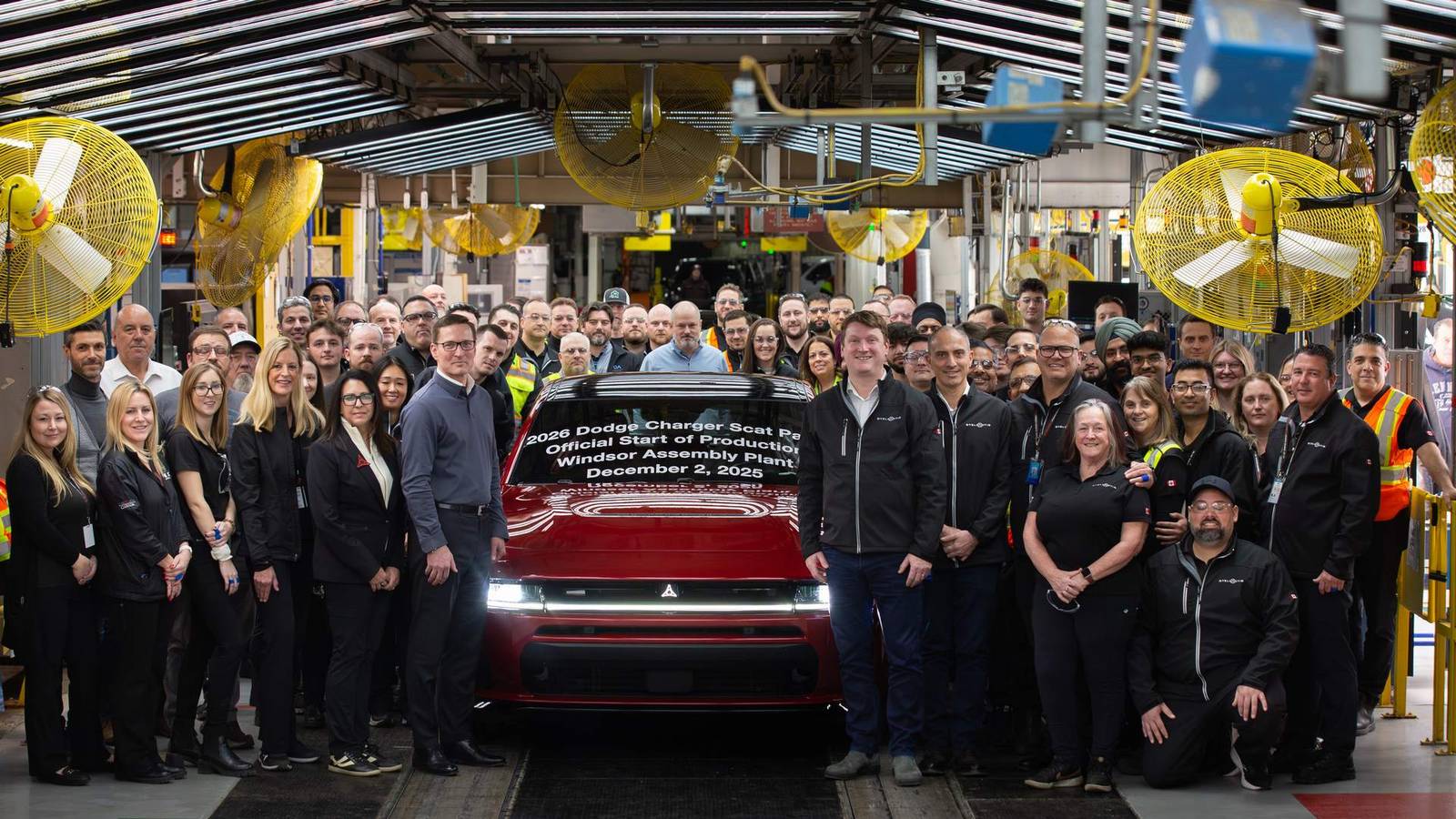

European and Japanese Manufacturers: Who Gets Hit Hardest

When you look at which automakers are most affected by the tariffs that remain, the pattern is clear. It's the imported stuff. European cars face 15% tariffs. Japanese vehicles face the same. South Korean cars too. That's BMW, Mercedes, Audi, Volkswagen, Volvo, Jaguar from Europe. Toyota, Honda, Subaru, Mazda, Nissan from Japan. Hyundai and Kia from South Korea.

What does a 15% tariff do? Let's do some math. If a car costs

Now, manufacturers have options. They can absorb it. They can pass it through to consumers. They can move production. Some European manufacturers have plants in the United States—that helps. BMW makes X-models in South Carolina. Mercedes has a plant in Alabama. When you can shift production to the US, the tariff doesn't apply. But that's expensive to do quickly. And it only works if you have existing capacity.

Japanese manufacturers have been more aggressive about US production. Honda, Toyota, Nissan all have significant American manufacturing footprints. But shifting all production to the US takes time and capital. In the meantime, if you're importing significant numbers of vehicles from your Japanese or European plants, you're paying the tariff.

This is where the tariff regime actually does influence prices in visible ways. You might see a European luxury vehicle become

Here's the strategic implication: tariffs actually make American-made vehicles more price-competitive relative to imports. That might sound good for US manufacturers, but it also means less competition, less price pressure, and potentially higher prices across the board.

The EV Factor: How Tariffs Affect Electric Vehicle Adoption

One of the most interesting dynamics in automotive tariffs is how they affect the EV transition. The Biden administration actually pushed hard on tariffs affecting Chinese EV manufacturers and battery components. The Trump administration has continued that, sometimes even escalating it.

Why? Because EV battery manufacturing is competitive globally, with China holding significant advantages. Chinese battery makers can produce cells more cheaply than American and European manufacturers. If you want to encourage domestic battery production, you apply tariffs to Chinese batteries. This makes domestic batteries more price-competitive by comparison.

But here's the challenge: this pushes up EV prices. Electric vehicles already cost more than gas-powered cars, largely because batteries are expensive. A typical EV battery pack costs

The result? EVs become less affordable. And affordability is critical to EV adoption. You need price parity with gas vehicles, or at least close to it, for mass adoption to happen. Tariffs that target battery components move in the opposite direction.

Some analysts argue this is actually intentional policy—that protecting domestic battery manufacturing justifies higher EV prices in the short term to build long-term capacity. But from a consumer perspective, it means the EV transition gets more expensive, which slows adoption.

The Supreme Court ruling doesn't directly address battery tariffs because those primarily come from Section 232 authority and other trade provisions, not IEEPA. So tariffs on battery components stay in place, keeping EV prices elevated.

This has real implications. If your plan was to switch to an EV but expected prices to come down with this Supreme Court ruling, you're going to be disappointed. EV prices will likely remain under upward pressure from tariffs for the foreseeable future.

Supply chain adjustments and technology upgrades are the primary contributors to the $10,000 increase in car prices over five years. Estimated data.

Supply Chain Resilience: The Hidden Cost Nobody Talks About

Here's something that doesn't make headlines but genuinely affects car prices: manufacturers have spent enormous resources making supply chains more resilient since the pandemic. That costs money, and that money shows up somewhere.

After 2020-2021 when semiconductor shortages crippled production, automakers learned a painful lesson: just-in-time inventory is fragile. You need buffer stock. You need redundant suppliers. You need geographic diversity. Building resilience means higher costs.

Why? Because resilience means carrying extra inventory. It means qualifying multiple suppliers for the same component, which reduces economies of scale. It means building or maintaining manufacturing capacity that isn't always running at full capacity. It means paying for supply chain visibility software and logistics coordination.

I'll be honest: most of this cost is invisible to consumers. You don't see a line item on a window sticker that says "supply chain resilience fee:

This cost doesn't go away with the Supreme Court ruling. In fact, if anything, ongoing tariff uncertainty makes automakers want stronger supply chain resilience, not weaker. So they're probably spending more on resilience, not less.

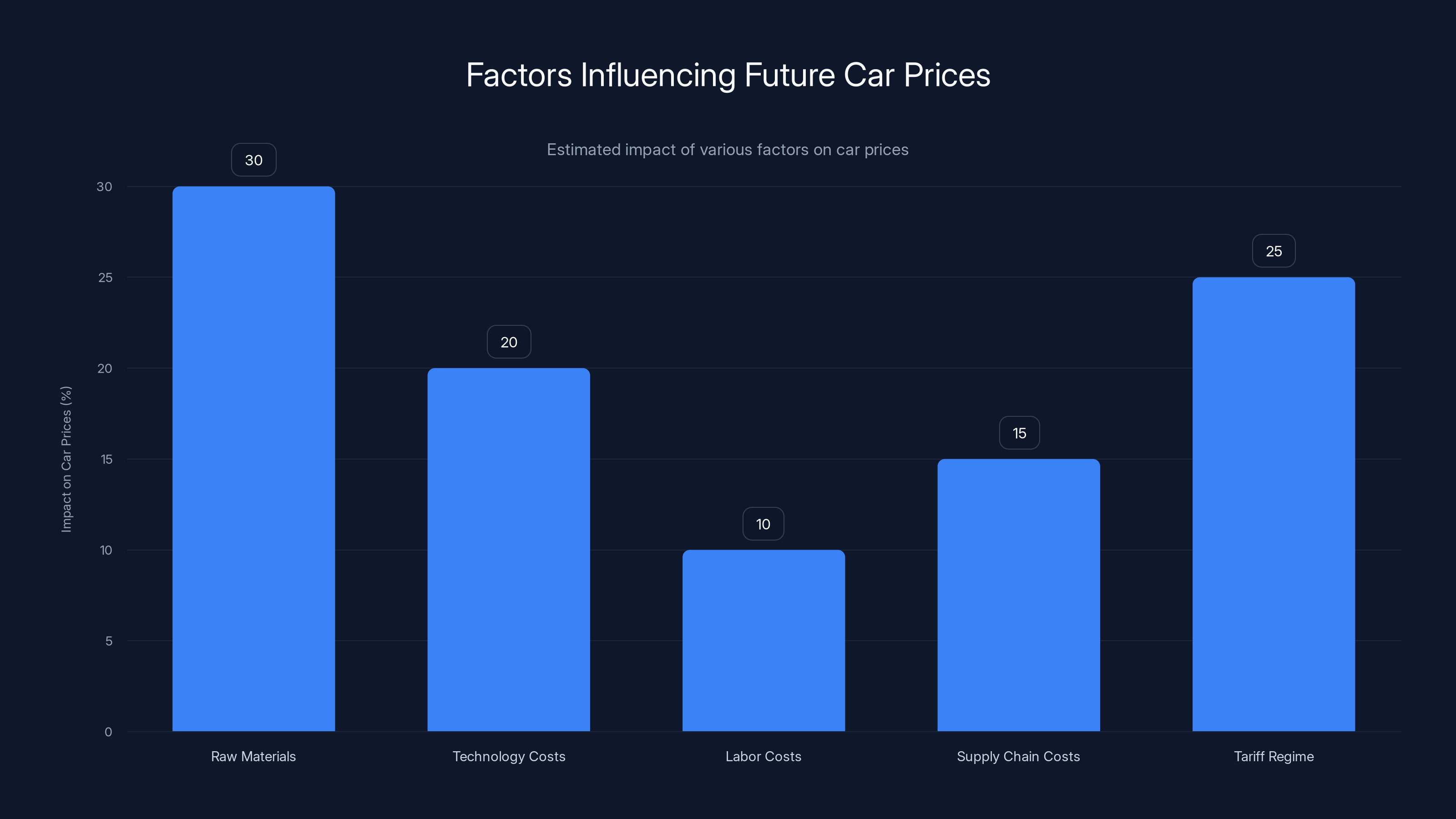

Raw Materials Markets: The Commodity Factor

Let's talk about what's happening in commodity markets because it directly affects car prices and it's something that has nothing to do with tariffs.

Steel and aluminum prices spiked during the pandemic and recovery. They've cooled since then, but they're still elevated compared to the 2015-2019 baseline. Lithium prices specifically spiked like crazy when EV demand ramped up. They've come down, but they're still higher than they were.

These aren't tariff-driven price increases. These are supply-and-demand dynamics. You had surging EV demand. Lithium mining didn't immediately scale to match. Prices went up. Manufacturers locked in long-term contracts at elevated prices. Those contracts are still running.

Meanwhile, rare earth materials used in EV motors face their own supply dynamics. Geopolitical tensions around the Middle East affect oil prices, which affects petrochemicals, which affects plastics and other materials in cars. These are global market forces that tariffs don't control.

The Supreme Court ruling doesn't change any of these commodity dynamics. So even if tariffs came down, you'd still have higher raw materials costs baked into car prices.

Labor Costs and the UAW: A Structural Price Driver

In late 2023, the United Auto Workers union struck a landmark deal with Detroit automakers. The deal was significant: substantial wage increases, faster progression to top wages, job security provisions, and the right to strike over plant closures.

Why does this matter for car prices? Because labor is a major cost component of vehicle manufacturing. The average labor cost per vehicle is somewhere in the

How much did labor costs go up? The UAW deal included wage increases of roughly 25% over the four-year contract. That's substantial. For automakers, this translates to higher per-vehicle costs. They can offset some of it through productivity improvements, but you can't improve productivity 25% overnight.

So some of the price increase you see in new vehicles is attributable to higher labor costs. And this is a structural change, not a temporary one. Wage agreements don't get reversed. Once workers get paid more, that becomes the new baseline.

Now, you could argue this is justified—that auto workers deserve higher wages, that the previous agreements were too low, that workers deserve to share in the productivity gains of the industry. Those are all reasonable arguments. But the point is: this is another cost driver that's completely independent of tariffs and completely unaffected by the Supreme Court ruling.

Estimated data: Raw materials and tariff regime changes could have the largest impact on reducing car prices, while technology and supply chain improvements also contribute significantly.

Technology Integration: The Software Cost That's Eaten Hardware

One of the biggest changes in cars over the past five years is the explosion of software and computing capability. A modern vehicle is basically a computer on wheels with some wheels attached.

That costs money. More than you might think. The infotainment system in a modern car—the central display, the processing power, the connectivity, the integration with your phone—this is an expensive subsystem. It's not like the stereo and navigation system in a 2015 car. It's a full computing platform.

Then you have all the driver assistance systems. Automatic emergency braking. Lane keeping assistance. Adaptive cruise control. Blind-spot detection. These all require cameras, radar, lidar in some cases, and sophisticated processing. These systems have become baseline equipment in most vehicles because of regulatory pressure and consumer expectations.

Battery management systems in hybrid and electric vehicles are remarkably complex. They need to monitor hundreds of individual cells, manage temperature, optimize charging, communicate with the motor and other systems. This is custom silicon in many cases, not off-the-shelf stuff.

Additionally, over-the-air update capability—the ability to download software updates remotely—requires backend infrastructure that didn't exist before. It requires security systems, authentication, server capacity. That all costs money.

How much? It's hard to get exact numbers because manufacturers don't break it out, but estimates suggest

Again, this is completely independent of tariffs. It doesn't go away with the Supreme Court ruling. It's structural.

Regulatory Compliance: Emissions and Safety Requirements

Governments around the world have been tightening emissions requirements and safety standards. In the United States, fuel economy regulations are getting more stringent, pushing automakers toward lighter vehicles or electrification. Safety regulations constantly add new requirements—higher crash test standards, new protective elements, advanced braking systems.

Each of these adds cost. To hit fuel economy targets, automakers invest in lighter materials, which are more expensive. To meet safety standards, they add reinforcement, airbags, sensors. These aren't optional extras. They're required by law.

The impact? Another

Again, the Supreme Court ruling doesn't touch this. Regulatory compliance is entirely separate from trade policy.

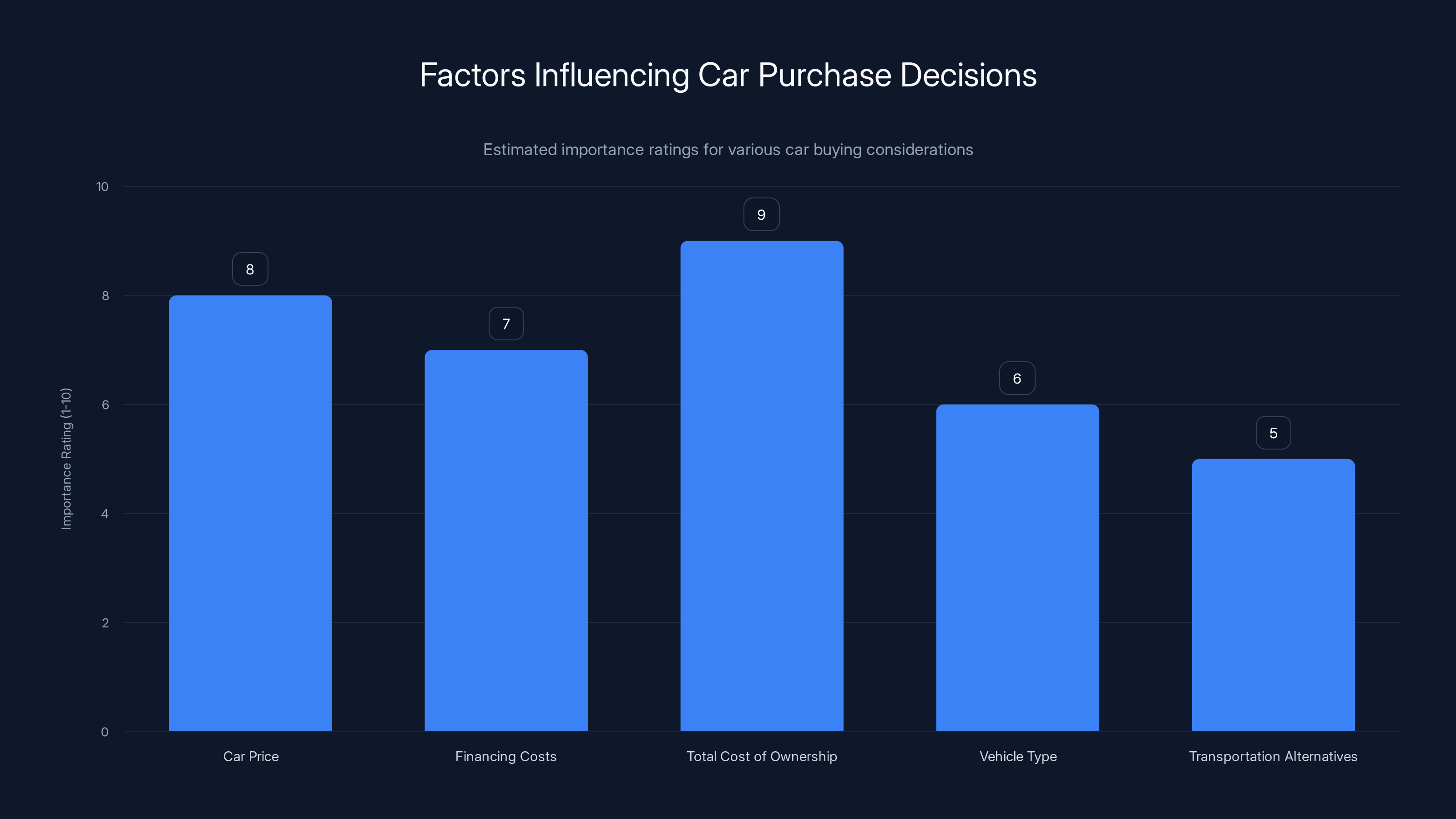

Dealer Economics: The Margin Question

One interesting question is whether dealers are taking advantage of tight market conditions to inflate margins. The answer is: somewhat, but it's more complex than that.

During the pandemic shortage period, when inventory was scarce, dealers absolutely captured some extraordinary margin. People were paying above MSRP. Dealers were adding packages and features whether customers wanted them or not. Times were very good.

As inventory has normalized, that dynamic has changed. Dealers now compete more aggressively on price. But there's still underlying constraint: they can't compete on price if their wholesale cost is high. If a dealer buys a car for

What they can do is get more aggressive on financing rates, extended warranties, and service packages. But on the vehicle price itself, they're somewhat constrained by wholesale costs.

Have dealer margins expanded compared to historical norms? Yes, somewhat. But the bigger story is that wholesale costs have risen due to all the factors we discussed—tariffs, materials, labor, technology, compliance. Dealer margins are probably a

This bar chart estimates the importance of various factors when making car purchase decisions. Total cost of ownership and car price are rated highest, indicating their critical role in decision-making. (Estimated data)

Global Market Dynamics: What's Happening Elsewhere

It's worth noting that high car prices aren't an American-only phenomenon. Cars are expensive globally. In Europe, cars cost more now than they did five years ago. In Japan, prices have risen. In China, prices are actually coming down somewhat because of competition and local manufacturing.

Why does the global context matter? Because it tells you something important: the main cost drivers are global, not tariff-specific. Supply chain disruption affected everyone. Raw materials prices affected everyone. Labor cost inflation affected everyone. Technology cost increases affected everyone.

Tariffs add a layer on top of these global dynamics, but they're not the foundation. The foundation is global. This is important because it suggests that even in countries with no tariffs on imported cars, prices have still risen significantly.

The Path Forward: What Realistically Comes Next

Let's be clear about what the Supreme Court ruling means for car prices going forward. It removes some IEEPA-based tariffs, which is real, but the main tariff regime stays. Section 232 tariffs remain. These are the big ones affecting the automotive industry.

Automakers will probably continue their strategy of absorbing some tariff costs while slowly passing others through to consumers. They'll continue investing in supply chain resilience. They'll continue navigating raw materials markets. They'll continue implementing technology that consumers expect.

Prices will probably continue gradual increases, but not dramatic ones. The Supreme Court ruling might enable some modest relief in a few specific areas, but the overall trajectory remains upward because the underlying cost structure hasn't fundamentally changed.

What could realistically bring prices down? Several things:

First, raw materials commodities would need to decline significantly. Lithium at

Second, technology costs would need to come down. This could happen if infotainment systems, battery packs, and driver assistance systems are produced at scale in more efficient ways. This is happening, but gradually.

Third, labor cost growth would need to moderate. This is unlikely given the new UAW contracts, but could happen if efficiency improvements offset wage growth.

Fourth, supply chain costs would need to normalize further. This is happening but slowly. Freight costs have normalized but are still elevated. Logistics complexity hasn't gone away.

Fifth, the tariff regime would need to end. This requires either new administrations making different trade policy choices, or legislative action, or major shifts in how Section 232 is interpreted. None of this is guaranteed.

Most likely scenario? Car prices stay elevated. You might see modest price decreases in a few segments where tariff reductions matter most. You might see slower price growth in the near term. But that $20,000 affordable car? It's not coming back anytime soon.

Implications for Different Car Buyers

Different buyers are affected differently by this situation. Let's break it down:

Budget-conscious buyers: You're in the most difficult position. Affordable cars barely exist anymore. Your options are limited to used vehicles, base models with minimal features, or considering a ride-sharing or leasing arrangement instead of purchase.

EV shoppers: You were hoping for price reductions that probably aren't coming soon. EVs remain premium-priced due to tariffs, battery costs, and technology. The trajectory might improve over five years, but not immediately.

Luxury buyers: You're least affected by tariffs as a percentage of purchase price. A

Fleet buyers: You're acutely aware of costs and might shift to used vehicles or extend replacement cycles to avoid the current high prices. This is actually affecting fleet economics industry-wide.

Imported car buyers: If you specifically want a European or Japanese car, tariffs hit you hardest. You might consider brands that produce locally—if you want a Japanese car, many Japanese brands have American manufacturing options that face lower tariff impact.

Structural cost factors such as technology integration and labor costs significantly outweigh tariffs in influencing car prices. Estimated data based on industry insights.

Why Media Coverage Matters Here

One thing to note: the Supreme Court ruling got significant media coverage as a win against tariffs. "Court Limits Presidential Tariff Power" makes a good headline. What's less covered is that the ruling's actual impact on car prices is minimal because the main tariffs affecting cars come from a different law that wasn't ruled on.

This matters because if you've been following the news, you might think car prices are coming down. They're not. The legal situation on tariffs has slightly improved, but the economic situation on car prices hasn't changed materially.

This kind of gap between headline and actual impact is pretty common in policy news. A court ruling is newsworthy. Implementation details are less so. But for car buyers, the implementation details matter more than the headline.

The Broader Economic Context

Zoom out even further and car prices aren't happening in isolation. They're part of a broader context of inflation and economic adjustment post-pandemic.

Inflation was high in 2021-2022. It's come down but hasn't fully normalized to pre-pandemic levels. Interest rates are higher than they were, which affects auto financing costs. Consumer credit has tightened somewhat. Wages have grown in many sectors, but not uniformly.

Cars are one of the biggest purchases most people make. They're sensitive to financing costs, interest rates, and overall economic sentiment. Even if car manufacturing costs came down, you'd still see elevated prices if financing costs are high or consumer confidence is low.

So the Supreme Court ruling, while legally significant, is a relatively small factor in a much larger economic picture.

Taking This Information and Making Decisions

If you're shopping for a car, here's what this analysis means practically:

Accept that prices are high. Don't wait for a major price drop because one isn't coming anytime soon. High car prices are the reality you're shopping in.

Consider your actual needs. Do you need the newest technology, or would an older model satisfy your transportation needs? Do you need premium power and performance, or would a base model work? Clarifying needs helps you find value.

Explore all vehicle types. Don't assume new is your only option. Used vehicles, lease returns, certified pre-owned—these options have very different economics.

Focus on financing costs. Shopping interest rates matters as much as shopping vehicle prices. A 1% difference in APR on a

Think about total cost of ownership. Purchase price is one factor. Insurance, maintenance, fuel/electricity, depreciation—these matter too. A cheaper vehicle that's expensive to insure and maintain might cost more overall.

Consider transportation alternatives. Public transit, bike, ride-sharing, car-sharing services—these might be more cost-effective than vehicle ownership depending on your location and needs.

The Supreme Court ruling tells you something about the legal landscape around tariffs. It tells you less about your actual options when you go to a dealership.

Final Analysis: The Bigger Picture

The Supreme Court's decision is legally interesting and represents a real constraint on presidential power under IEEPA. That matters from a constitutional perspective. It also means some tariffs will be unwound, which is real relief for some industries and consumers.

But car buyers shouldn't expect major price reductions. The tariffs that matter most for cars—Section 232 tariffs on imported vehicles, steel, and aluminum—remain fully in effect. These are substantial tariffs that cost consumers real money.

Beyond tariffs, the cost structure of modern vehicles has fundamentally changed. Technology costs more. Compliance costs more. Labor costs more. Raw materials cost more. Supply chains are more resilient but also more expensive to maintain. These aren't temporary phenomena. They're structural.

So here's the honest assessment: car prices were high before the Supreme Court ruling. They'll probably stay high after it. You might see modest relief in specific segments or markets, but the broad pattern of expensive cars likely persists.

For consumers, this is frustrating. For analysts, it's a reminder that headline-grabbing court decisions don't always translate to immediate economic relief for regular people. The legal system and the economic system operate on different timescales and respond to different pressures.

Your best move? Stop waiting for prices to come down. Instead, focus on finding the best value available in the current market, which is different from finding the cheapest car.

FAQ

What exactly did the Supreme Court rule about tariffs?

The Supreme Court ruled that the president cannot use the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA) to impose broad tariffs simply because of large trade deficits. The decision limits the president's ability to declare "national emergencies" for trade purposes, though it doesn't eliminate tariff authority under other laws like Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act.

Why don't the Supreme Court's tariff restrictions apply to car tariffs?

Most tariffs affecting the automotive industry come from Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act, not from IEEPA. Section 232 remains fully intact after the Supreme Court ruling. The 15% tariffs on cars from Europe, Japan, and South Korea, as well as tariffs on steel and aluminum, all come from Section 232 authority and are therefore unaffected by this decision.

When will new car prices start decreasing?

Significant price decreases aren't likely in the near term. While the Supreme Court ruling removes some tariffs, the broader cost structure of vehicles—including materials, technology, labor, and supply chain complexity—remains elevated. Modest price slowdowns might occur, but a return to 2019 pricing levels would require fundamental changes in multiple cost factors simultaneously, which is unlikely in the next 1-2 years.

How much do tariffs add to the cost of a car?

For imported vehicles, tariffs can add

Which automakers are most affected by tariffs that remain in place?

European manufacturers like BMW, Mercedes, Audi, and Volkswagen, along with Japanese manufacturers like Toyota, Honda, Nissan, and Japanese luxury brands, face the most significant tariff impact because their vehicles are primarily imported. South Korean brands like Hyundai and Kia are similarly affected. American manufacturers and those with significant U. S. production capacity face lower tariff impact.

Are electric vehicles exempt from these tariffs?

No, EVs are not exempt from Section 232 tariffs. Both traditional EVs and plug-in hybrids face the same 15% tariffs if imported. Additionally, tariffs on battery components and materials add to EV costs. This has slowed EV adoption somewhat since electric vehicles are already more expensive than gas-powered alternatives due to battery costs.

What's more important than tariffs for current car prices?

Several factors exceed tariffs in impact: technology costs (infotainment, driver assistance, connectivity systems add

Could new administrations change Section 232 tariffs?

Yes, but it would require either a new president choosing not to invoke Section 232 authority, which is discretionary, or Congressional action to restrict or modify Section 232 itself. Given the broad historical deference courts have given to Section 232 interpretations, legislative action would likely be necessary for fundamental restrictions. This isn't imminent in either major party's agenda.

What should car buyers do given this situation?

Expect that car prices will remain elevated rather than declining soon. Focus on finding value within the current market rather than waiting for major price drops. Consider used vehicles, which have normalized faster than new vehicles. Evaluate whether you truly need new technology or if an older model meets your needs. Shop financing rates carefully, as APR differences impact total cost more than minor purchase price variations. Consider transportation alternatives if they're available in your area.

How do car prices compare globally to the United States?

Cars are expensive globally. Prices have increased in Europe, Japan, and most developed markets over the past five years, though the specific drivers vary by country. China is actually seeing some price decreases due to intense domestic competition and local manufacturing. This global pattern suggests the main cost drivers are structural and global—supply chain disruption, materials costs, technology integration—rather than tariff-specific, which is why removing some tariffs won't dramatically change the overall price picture.

TL; DR

-

Supreme Court ruling only partially affects auto tariffs: The decision limits presidential power under IEEPA but leaves Section 232 tariffs (the main ones hitting cars) fully in effect. Tariffs remain a

8,000 cost factor on imported vehicles. -

Structural cost factors dominate: Technology integration, labor costs, raw materials, supply chain resilience, and regulatory compliance add far more to car prices than tariffs alone. These factors aren't going away soon.

-

**Average new car prices hit

20,000" has effectively disappeared from the market. -

Automakers absorbing some costs, but can't indefinitely: Currently absorbing about 1% of tariff costs annually, but analysts warn this can't continue forever. Eventually more costs flow to consumers.

-

Bottom line: Don't expect meaningful car price reductions from this ruling. Prices will likely stay elevated due to structural cost factors that are independent of trade policy.

Key Takeaways

- The Supreme Court ruling eliminates IEEPA tariff authority but leaves Section 232 tariffs fully intact, meaning auto tariffs remain at 15% for imported vehicles

- Average new car prices hit $48,576 in 2025, up 33% from 2019, driven primarily by technology costs, labor increases, and raw materials inflation rather than tariffs alone

- Technology integration (infotainment, driver assistance, connectivity) adds 4,500 per vehicle in new cost compared to 2019 baseline vehicles

- Automakers currently absorb about 1% of tariff costs through margin compression, but can't sustain this indefinitely if tariff pressures continue

- Affordable vehicles under $20,000 have essentially disappeared from the market; buyer options are limited to used vehicles, base models, or leasing alternatives

Related Articles

- Supreme Court Rules Trump's Tariffs Illegal: What This $175B Decision Means [2025]

- Nvidia's AI Chip Strategy in China: How Policy Shifted [2025]

- How Davos Became Silicon Valley's Mountain Summit [2025]

- How Trump's Tariffs Are Creeping Into Amazon Prices [2025]

- How BYD Beat Tesla: The EV Revolution [2025]

- Trump's 25% Advanced Chip Tariff: Impact on Tech Giants and AI [2025]

![Why The Supreme Court's Tariff Ruling Won't Lower Car Prices [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/why-the-supreme-court-s-tariff-ruling-won-t-lower-car-prices/image-1-1771634184260.jpg)