Why Thinking Machines Lab Lost Its Co-Founders to Open AI: Lessons from Silicon Valley's Biggest AI Talent War [2025]

Last January, the AI industry watched something almost unthinkable happen. Barret Zoph, Luke Metz, and Sam Schoenholz, three of the most respected researchers in artificial intelligence, quietly walked away from Thinking Machines Lab—the startup they'd helped launch just months earlier with a

On the surface, it's a story about three talented people changing their minds. But dig deeper, and you'll find something far more revealing about how the AI industry actually works, why startup loyalty is fragile, and what it takes to compete for world-class talent in 2025.

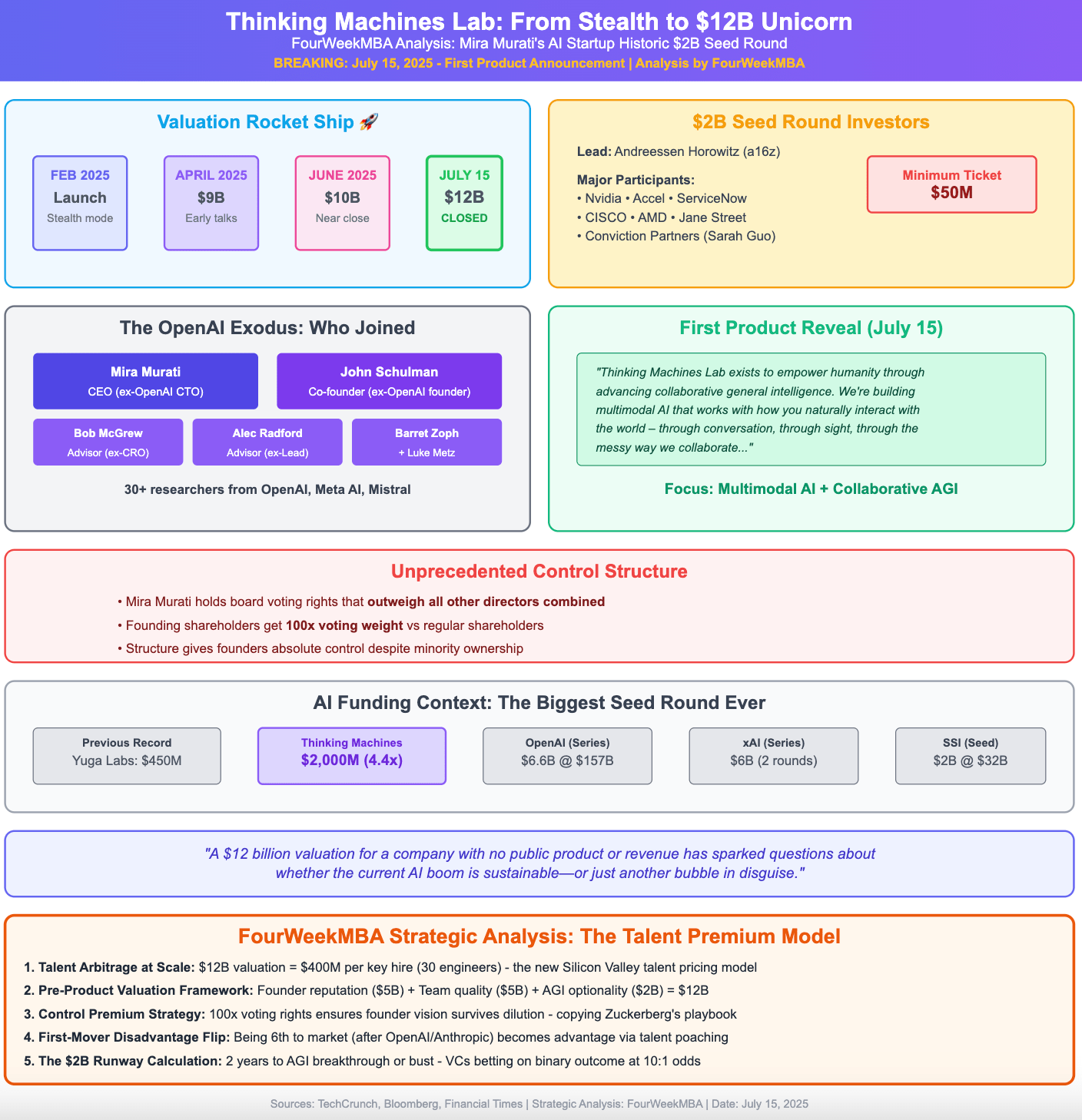

Mira Murati, who founded Thinking Machines as the former CTO of Open AI, had assembled what looked like an unstoppable team. These weren't junior researchers or fresh faces. Zoph had been VP of Research at Open AI and spent six years at Google as a research scientist. Metz had spent years on Open AI's technical staff building systems that power the platform today. Schoenholz had similar pedigree. The startup had backing from Andreessen Horowitz, Nvidia, AMD, Accel, and Jane Street—literally everyone who matters in AI infrastructure.

Yet here's what actually happened: A startup that looked bulletproof on paper cracked almost as soon as it launched. Two co-founders left. Another key researcher, Andrew Tulloch, had already departed for Meta. The narrative of an unstoppable AI startup founded by ex-Open AI talent suddenly looked fragile.

This isn't just interesting gossip from Silicon Valley. It's a case study in why startup success in AI is harder than people think, why founder alignment matters more than funding, and why the biggest players in AI can always pull back top talent. Here's what we actually learned from this moment.

The Setup: Why Everyone Thought This Would Work

When Thinking Machines Lab launched in February 2024, it felt inevitable. Mira Murati had left Open AI as CTO—a serious leadership role—suggesting she had something bigger in mind. She brought Barret Zoph and Luke Metz with her, two researchers who'd contributed to some of Open AI's most important work.

Zoph's background alone was a signal of seriousness. He'd spent six years at Google as a research scientist, working on large-scale machine learning. He then became VP of Research at Open AI, which means he was responsible for the direction of Open AI's technical roadmap. That's not a job you take lightly or leave casually. When he left Open AI for a startup, people paid attention.

Metz had equally impressive credentials. He'd worked on Open AI's technical staff for years, contributing to the systems that power the company's products. You don't walk away from that kind of responsibility unless you're convinced something bigger is coming.

Schoenholz brought similar expertise. Before joining Thinking Machines, he'd worked at Open AI in a technical capacity. His move signaled that Murati had convincing reasons to leave and had convinced others to do the same.

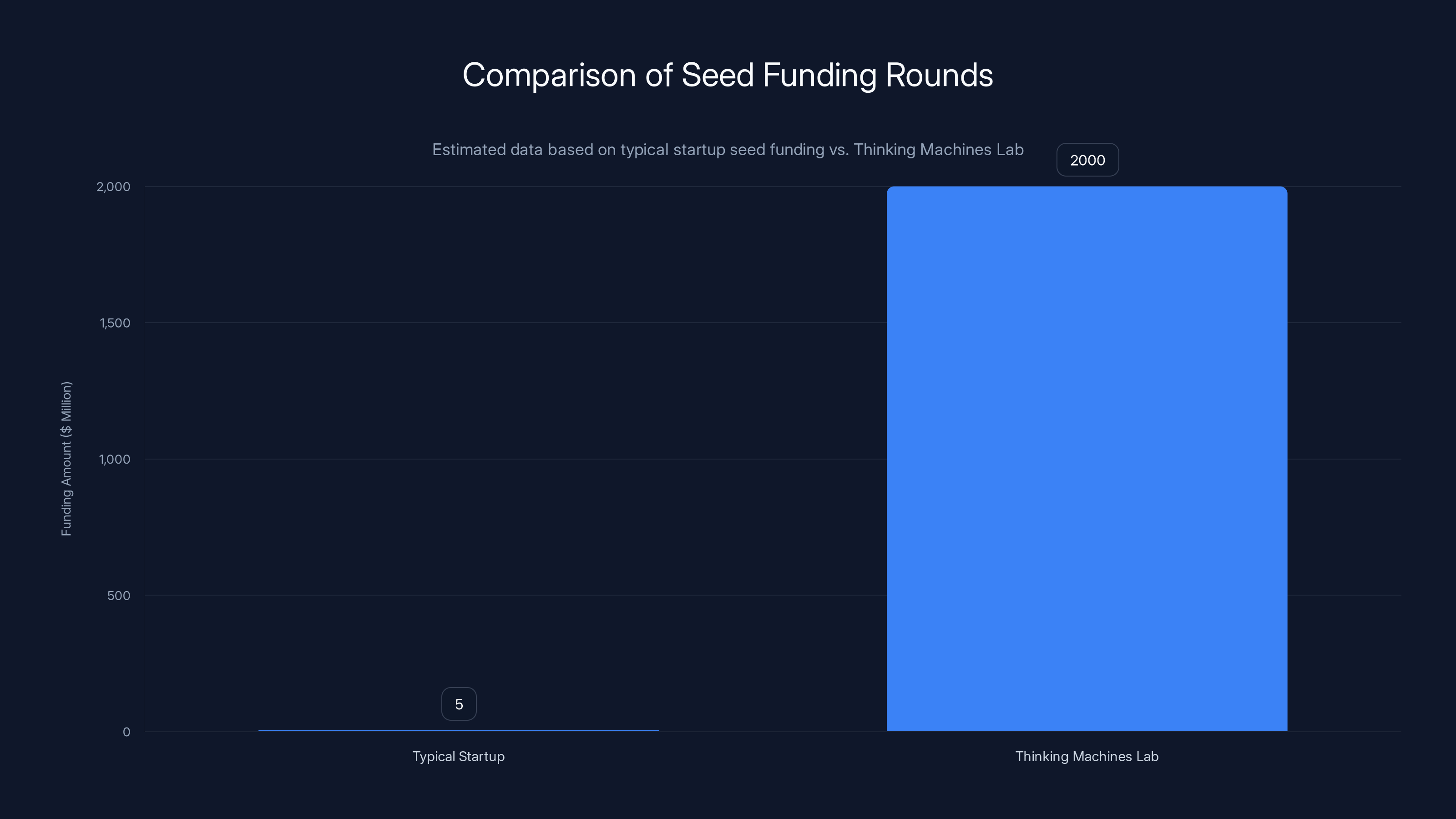

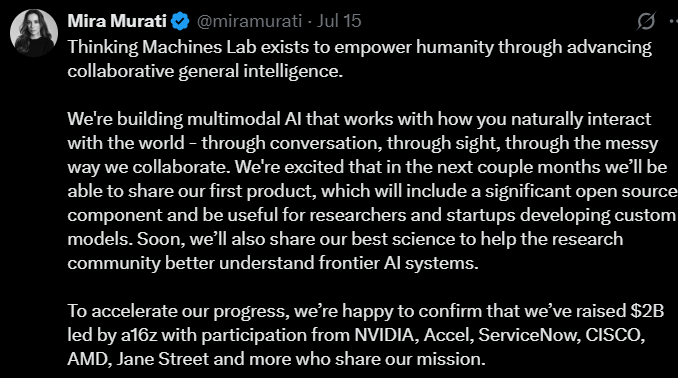

The funding round was absolutely massive for a startup that had only been operating for weeks. A

This wasn't typical Silicon Valley hype. This was institutional capital making a massive bet. Andreessen Horowitz doesn't lead a $2 billion round on speculation. Nvidia doesn't invest that much without serious conviction. AMD doesn't either. Jane Street, one of the world's most sophisticated trading firms, doesn't participate in meaningless bets.

So on paper, everything looked right. Great founders, proven track record, serious capital, an ambitious mission. What could possibly go wrong?

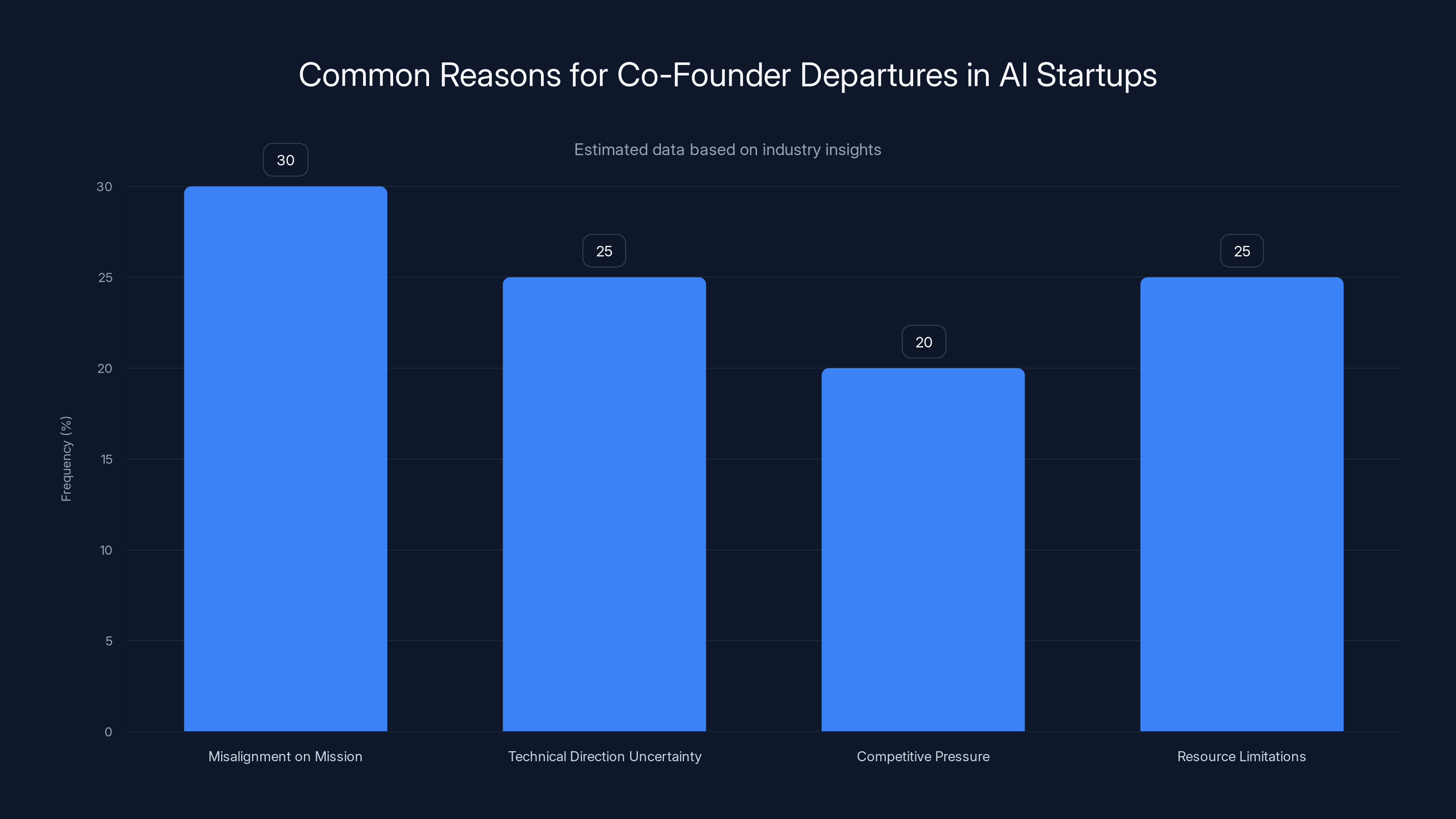

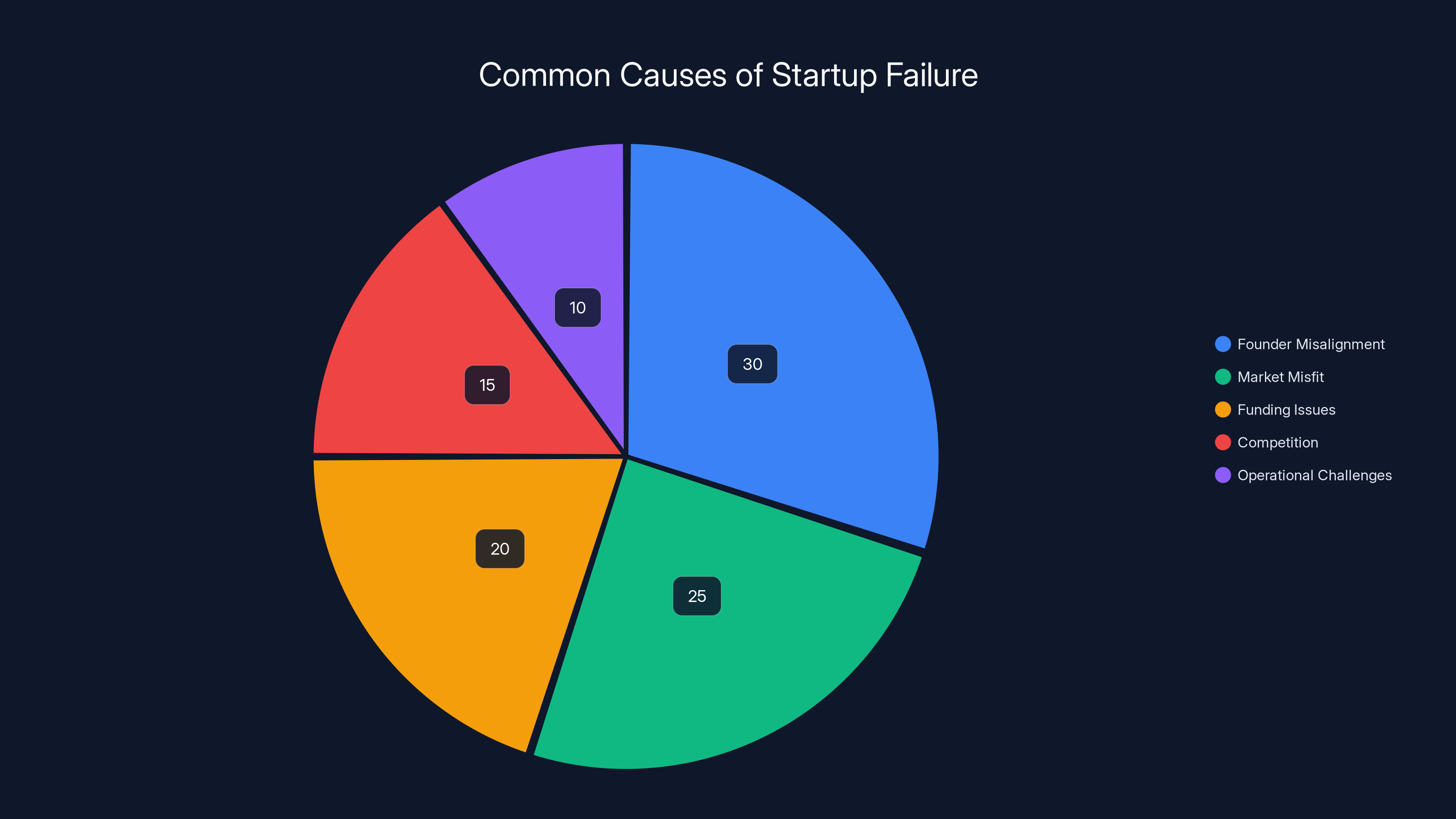

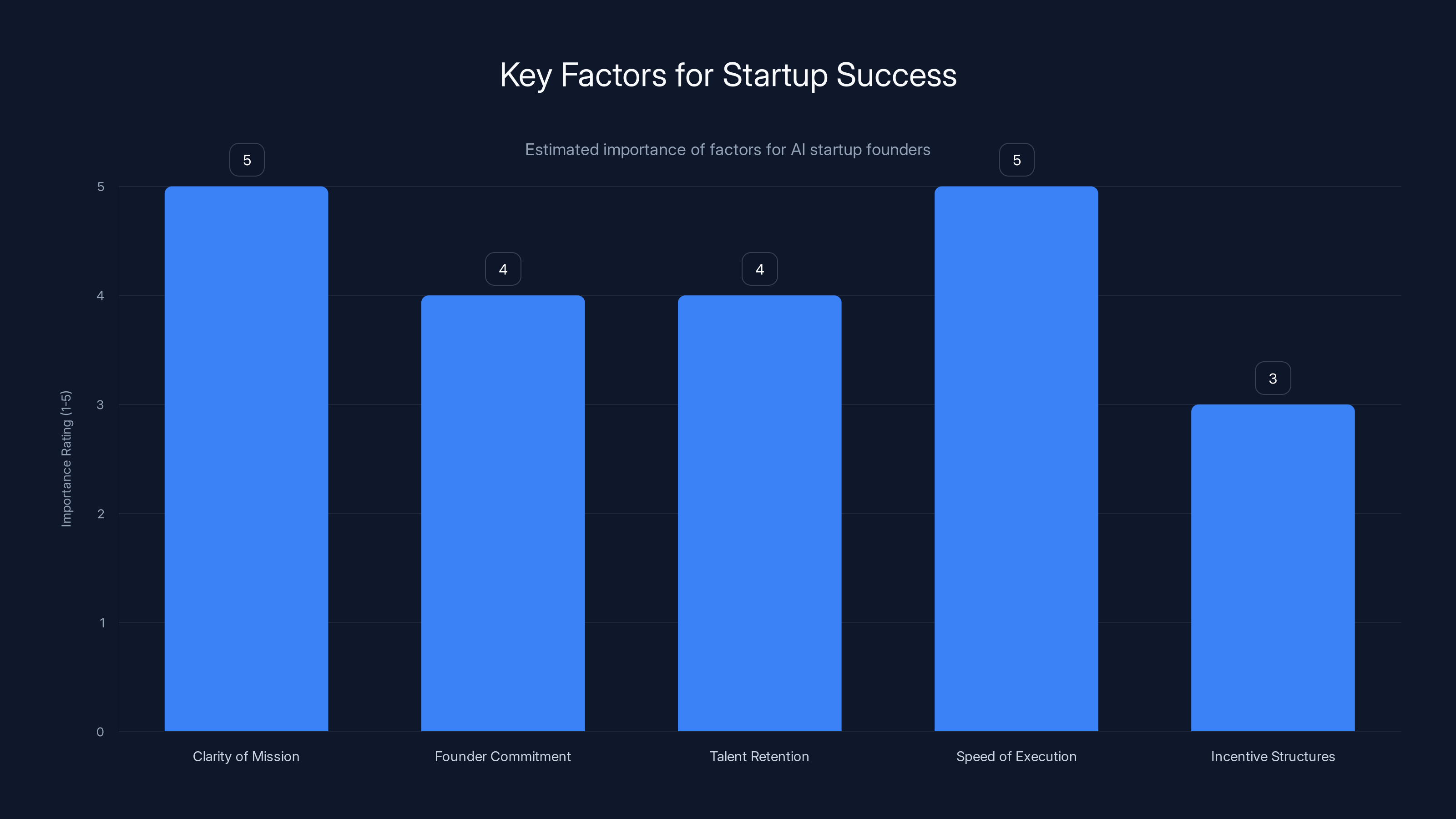

Misalignment on mission and technical direction uncertainty are leading reasons for co-founder departures in AI startups. Estimated data.

The Real Issue: Founder Alignment and Mission Clarity

Here's what typically kills startups, even ones with great funding and great people: the founders stop believing in the same thing.

When people join a startup, they're not joining just for money. Money at a successful startup comes later—years later, potentially. People join because they believe the founders have figured out something true about the world that the rest of the industry hasn't.

At Open AI, there's incredible clarity about the mission. Sam Altman has been unambiguous about what Open AI is trying to do: build artificial general intelligence safely and make sure it benefits humanity. People who work there might disagree with specific decisions, but they understand the mission.

At a new startup, especially one founded by people from an established company, there's often less clarity. Murati left Open AI to start Thinking Machines, presumably because she had a different vision of how to build advanced AI. But what exactly was that vision?

The public statements about Thinking Machines were vague. The company talked about focusing on AI safety and interpretability—concepts that sound good but are slippery. "We're building interpretable AI" can mean anything from automated theorem proving to better documentation tools. "We're focused on safety" could mean researching alignment, building better safeguards, or developing evaluation frameworks.

When co-founders don't align on the mission beyond the vague public statements, it creates friction. You might think you all agree on "building the best AI company," but after six months of actually trying to build that company, you realize you disagreed about what "best" means.

Zoph might have thought Thinking Machines would focus on frontier research—pushing the boundaries of AI capability. Metz might have thought it would focus on productization—taking existing capabilities and making them more reliable. Schoenholz might have thought it would focus on deployment—getting AI systems into production environments safely.

All three visions are reasonable. All three could generate enormous value. But if you're the only one who believes in your version of the mission, it's exhausting. You're fighting upstream constantly.

Meanwhile, Open AI is still there. Open AI has absolute clarity about mission. Open AI is still the most interesting place in the world to work on AI. And Open AI can offer something a new startup can't: momentum. Open AI has Chat GPT. Open AI has GPT-4 and GPT-4o and everything coming next. You don't get to influence an uncertain startup's direction. You get to influence the most powerful AI system in the world's development.

That's a hard pitch to turn down, especially if you're not 100% convinced about your startup's direction.

The Talent War: Why Open AI Could Reclaim Its People

There's a specific dynamic that plays out at successful, well-funded startups founded by ex-employees of an industry leader: the parent company always has the nuclear option to recall key talent.

Open AI is in a unique position in the AI industry. It's not just a big, successful company. It's the company that created the current wave of AI. GPT-4 changed the direction of the entire industry. That fact creates gravitational pull.

When Barret Zoph was VP of Research at Open AI, he was responsible for some of the most important technical decisions in AI history. Working on GPT-4, working on RLHF scaling, working on capability evaluations—these are the kinds of problems that define a generation of AI research.

When he left for Thinking Machines, did he have access to those problems? Probably not in the same way. Thinking Machines would have to build everything from scratch. The capital was there, the talent was there, but the institutional knowledge was not.

Open AI has something most startups can't replicate: the infrastructure, the compute, the data, and the institutional knowledge of how to actually build large language models at scale. That's not something you can hire your way into. You have to build it, and building it takes time.

So when Open AI came back and said, "We want you back, and we're going to give you real resources and real authority to work on important problems," Zoph had to ask himself: Is my startup going to move faster than staying at Open AI? Is the vision clearer? Am I more convinced of the mission?

And the answer, apparently, was no.

The Other Departures: A Pattern Emerges

Zoph and Metz weren't the only ones to leave. Andrew Tulloch, another co-founder, left to join Meta just a few months earlier. That's a critical signal that goes beyond individual circumstances.

Tulloch leaving for Meta suggests something important: the team wasn't unified around staying at this particular startup. If everyone had been convinced that Thinking Machines was the right bet, losing a co-founder to a competitor would be unusual. But losing two co-founders (Zoph and Metz to Open AI) and a third co-founder (Tulloch to Meta) within a year of launch suggests systemic issues.

When multiple co-founders leave a startup, it's rarely because they all independently decided to pursue other opportunities. It's usually because they lost faith in the vehicle. Maybe the technical direction changed. Maybe they realized the market opportunity wasn't as big as they thought. Maybe the team dynamics shifted. Maybe they got offered things they couldn't refuse.

What we know for certain is this: having two of your three co-founders leave within twelve months of founding is brutal. It's not just a loss of talent—though that's significant. It's a loss of credibility. It sends a message to the rest of the team, to investors, to potential customers, and to the rest of the industry that something isn't working.

Thinking Machines Lab's $2 billion seed round dwarfs typical startup funding, highlighting investor confidence. Estimated data.

Why This Matters: The Economics of AI Startups in 2025

Thinking Machines Lab isn't the first startup to lose key talent to a larger company. But the scale of this loss, and the speed of it, reveals something fundamental about how the AI market is actually structured right now.

The conventional wisdom in Silicon Valley is that startups win on focus and speed. Startups don't have bureaucracy. Startups can move faster. Startups can take bigger risks. All of that is theoretically true.

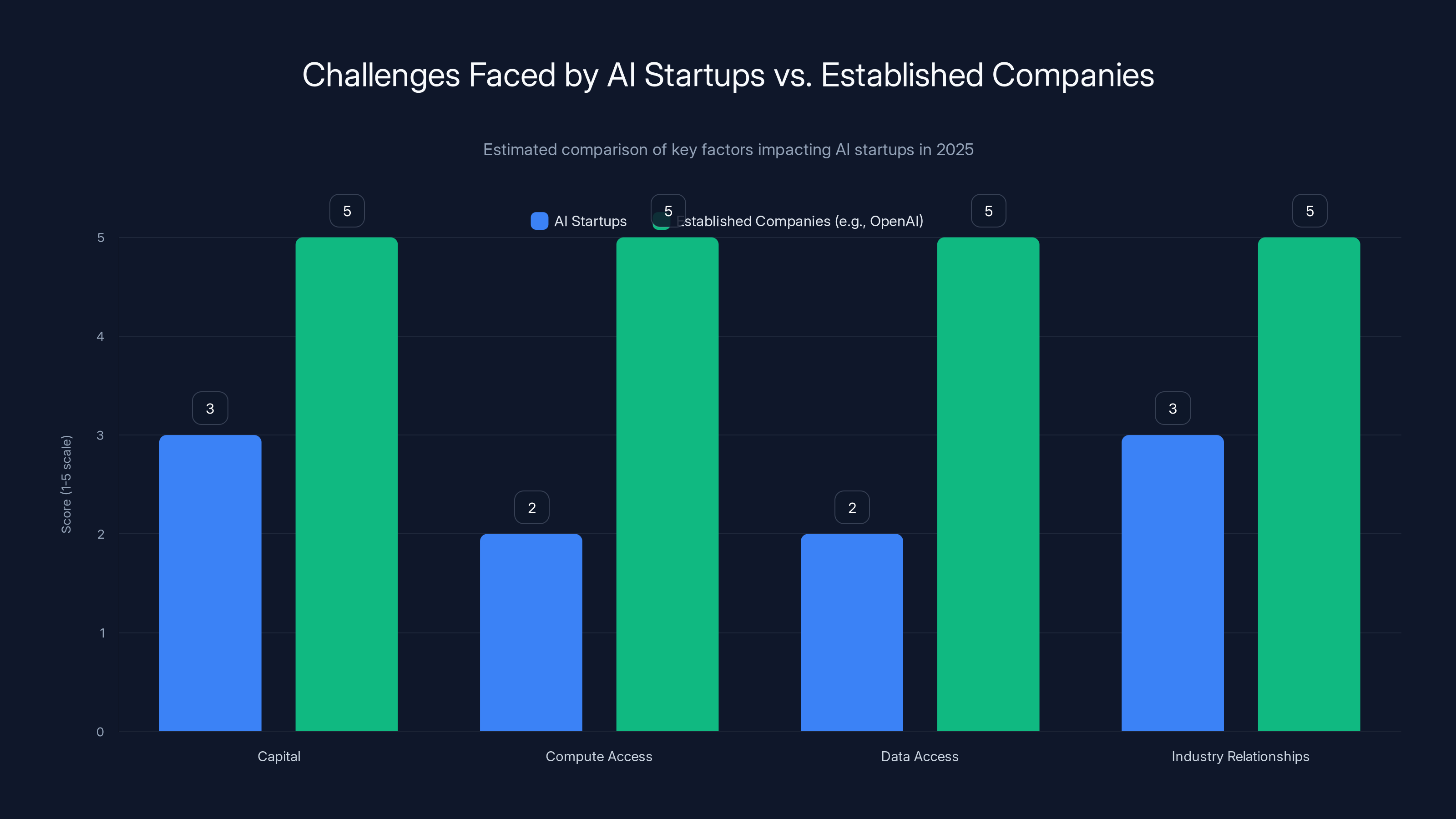

But in AI, there's a countervailing force: capital and compute concentration. Open AI has access to massive amounts of compute. The company has relationships with the world's largest companies. Open AI has an API with billions of dollars in annual usage. The data flowing into Open AI systems is constant and enormous.

A startup, no matter how well-funded, starts from zero on all of these dimensions. You have capital but not infinite capital relative to Open AI's resources. You have relationships but not the same tier of relationships. You have ambition but not momentum.

Building an AI company from scratch in 2025 requires you to answer fundamental questions: Do we build our own foundation models, or do we build on top of someone else's? If we build our own, can we get the compute? Can we train faster than Open AI, Claude, Gemini, etc.? Do we have access to the right data?

These aren't trivial questions. Training a competitive foundation model costs billions of dollars. You need access to cutting-edge chips (which are hard to get). You need to solve problems that the entire research community is trying to solve, but you're doing it with fewer resources and less institutional knowledge.

That's the position Thinking Machines was in. Despite the massive funding, it was starting from a disadvantageous position relative to Open AI. Zoph, Metz, and Schoenholz, who had been inside the machine at Open AI, probably realized this faster than most people would.

The Announcement: How It Went Down

The way this exodus happened is also telling. Murati announced Zoph's departure on social media. Just 58 minutes later, Fidji Simo, Open AI's CEO of Applications, announced that not just Zoph, but also Metz and Schoenholz were joining Open AI.

That timing is no accident. It suggests coordination. It suggests that Open AI and Thinking Machines Lab were in communication about this before it became public. The speed of the announcement—58 minutes—suggests that once the first departure was public, the other two were going to be public immediately anyway, so why not get ahead of it?

The language in Simo's announcement was diplomatic. "Excited to welcome Barret Zoph, Luke Metz, and Sam Schoenholz back to Open AI! This has been in the works for several weeks." That last sentence is doing a lot of work. "Several weeks" of planning suggests this wasn't an impulsive decision. This was something being discussed, negotiated, and planned for a significant amount of time.

So the people making the decision—Zoph, Metz, Schoenholz—had been thinking about this for weeks. They'd probably been having conversations with Open AI for weeks. They'd probably been discussing it among themselves. And then, at some point, they made the decision to announce it.

Murati's announcement notably made no mention of these departures. It only mentioned Zoph's departure, not the others. That's an interesting omission—it suggests Murati might not have known the full extent of what was about to happen.

What This Reveals About Startup Founder Incentives

Here's something important that often goes unsaid: Murati, Zoph, and Metz have fundamentally different incentive structures as co-founders.

Murati stepped down from the CTO role at Open AI to start this company. For her, the primary incentive is for Thinking Machines to succeed. Her brand is tied to this company. Her future credibility in the industry depends on this working out.

For Zoph and Metz, the incentives might be different. They left cushy jobs at Open AI to join a startup, which is brave. But if the startup isn't materializing the way they hoped, they're not penalized as heavily for leaving. They can go back to Open AI, still be in the game, still work on important problems. Their personal credibility isn't as damaged.

This is a classic problem with co-founder dynamics. The founder who gave up the most (Murati, who left a C-level role) is the most committed to the success of the company. The co-founders who came along for the ride have an easier path back to security.

That's not a moral judgment. It's just how incentives work. If you're Zoph and you've just spent six months realizing that the startup isn't moving as fast as you expected, or the technical direction is different from what you signed up for, you have good options. You can go back to Open AI. You'll be welcomed there. You'll get to work on important problems. You'll get paid well.

If you're Murati, you don't have that option. You've burned bridges at Open AI. You've staked your reputation on Thinking Machines. So you keep going, even if two of your three co-founders leave.

Building in the Shadow of Giants: The Structural Challenge

One of the hardest things about starting an AI company in 2025 is that you're building in the shadow of Open AI, Anthropic, Google, Meta, and others who are moving incredibly fast.

Open AI releases a new model every few months. They're constantly improving, constantly shipping, constantly innovating. When you're outside that loop, you feel it. Your best researchers probably spent years thinking about how to optimize training, how to scale inference, how to improve reasoning. They did that work inside Open AI. They built intuitions based on massive-scale systems.

When they come to your startup, they have to start from scratch building those systems. Or they have to be comfortable being behind. Neither option is appealing to world-class researchers.

This is why Anthropic has been more successful at retaining talent than Thinking Machines appears to be. Anthropic was founded by Dario Amodei and Daniela Amodei, who both left Open AI, but they had a deep technical vision. They had decided that scaling laws alone weren't going to get you to AGI. They believed in a different approach to safety and alignment. They had a clear story about why you should join them instead of staying at Open AI.

Thinking Machines' story was less clear. It was "build interpretable AI," which is good, but it's not as compelling as "here's the new paradigm for how to build AI safely and effectively."

Founder misalignment is estimated to account for 30% of startup failures, highlighting the importance of mission clarity. Estimated data.

The Role of Capital: Does Money Actually Solve This?

Thinking Machines had more capital than almost any startup has ever had. The $2 billion seed round is genuinely unprecedented. It's more money than most companies raise in their entire lifetime. It's enough capital to do basically anything.

But the exodus of co-founders shows something critical: capital doesn't solve for founder alignment or mission clarity. Money can buy engineers. Money can buy compute. Money cannot buy genuine belief in a mission.

In fact, capital can sometimes obscure problems. With massive funding, you can grow your team quickly, open multiple offices, pursue multiple technical directions. You can explore a lot of possibilities. But that exploration can also create confusion. Without clear direction from the founders, a well-funded startup can become a collection of different projects instead of a unified vision.

This might be part of what happened at Thinking Machines. With $2 billion in the bank, there was probably a lot of optionality. Do we build foundation models? Do we focus on safety research? Do we focus on applications? Do we focus on interpretability? With that much money, you can try to do all of it.

But when you're trying to do everything, you're not clearly doing anything. And when you're not clearly doing anything, it's hard for brilliant researchers to maintain conviction. They look around and think, "I could be here pursuing a vague mission, or I could go back to Open AI where the mission is crystal clear and we're moving at incredible speed."

The Momentum Problem: Why Existing Players Win

Open AI has momentum. It ships products that millions of people use. It has revenue. It has proof that its approach works. It's changing the world in real time.

Thinking Machines doesn't have that yet. It has potential. It has funding. It has talent. But it doesn't have proof of concept at scale.

This matters psychologically. When you work somewhere with momentum, every day feels like you're making progress. You see users adopting your product. You see the impact. You see your work mattering in real time.

When you work somewhere building toward something, with proof of concept coming later, every day feels a bit more uncertain. You're making progress in the abstract, but you don't have external validation.

For senior researchers like Zoph and Metz, momentum is worth a lot. They could have amazing career outcomes at Thinking Machines. But they could have amazing career outcomes at Open AI too, and Open AI already has the momentum.

When you're choosing between two paths, and one has momentum and one doesn't, the choice becomes easier, especially if both paths are professionally interesting.

The Signal to the Industry: What This Meant for Other AI Startups

When news broke that Zoph, Metz, and Schoenholz were going back to Open AI, it sent a specific signal through the AI startup ecosystem. The signal was: even with $2 billion in funding, even with world-class founders, even with top talent, you can lose co-founders to the big players within a year.

This affects recruiting. If you're a talented researcher thinking about joining an AI startup, and you see that two of three co-founders left a well-funded startup to go back to an incumbent, what does that tell you about the stability of working at startups?

It tells you that regardless of funding, regardless of branding, regardless of initial hype, the incumbents have tools to pull you back. They have compute. They have data. They have customers. They have momentum.

Some researchers will look at that and think, "I'd rather join Open AI directly and skip the startup phase." Others will think, "This is hard, but it's worth trying." But the calculus shifts. The case for startups gets harder.

This is why acquisitions and acquihires are common in tech. Big companies can always say, "Join our team at our company, and we'll solve the hard problem of distribution for you." Startups have to say, "Join our team and help us build something from scratch with less certainty about the outcome but potentially more upside." When the uncertainty gets too high, people choose the bird in the hand.

Lessons for Future Startup Founders

If you're starting an AI company and you want to recruit talent from the big players, what do you learn from what happened to Thinking Machines?

First: clarity of mission is non-negotiable. Your co-founders need to be aligned not just on the general idea but on the specifics. Are you building foundation models or applications? Are you focusing on safety or capability? Are you pursuing a different technical approach or a different business model? Get alignment on this before you fundraise.

Second: founder commitment matters. If any of your co-founders seem like they might leave, talk about it explicitly. Sometimes the right answer is for them to leave before you raise money. Better to find out early than after you've taken $2 billion in funding.

Third: you can't compete on talent retention with incumbents who have momentum. You have to give your team something they can't get at the big players. Usually, that's autonomy, equity upside, or a clear vision of how you're going to win. If you don't have one of those three things, you'll lose talent.

Fourth: build something fast. The faster you can show momentum, the faster you can retain people. If you can ship products, get customers, and demonstrate traction, it's much harder for people to leave. Momentum is contagious.

Fifth: consider the incentive structures. Some people will be more committed to the startup than others based on what they gave up to join. That's not a moral failing. That's just how humans work. Account for it in your team dynamics.

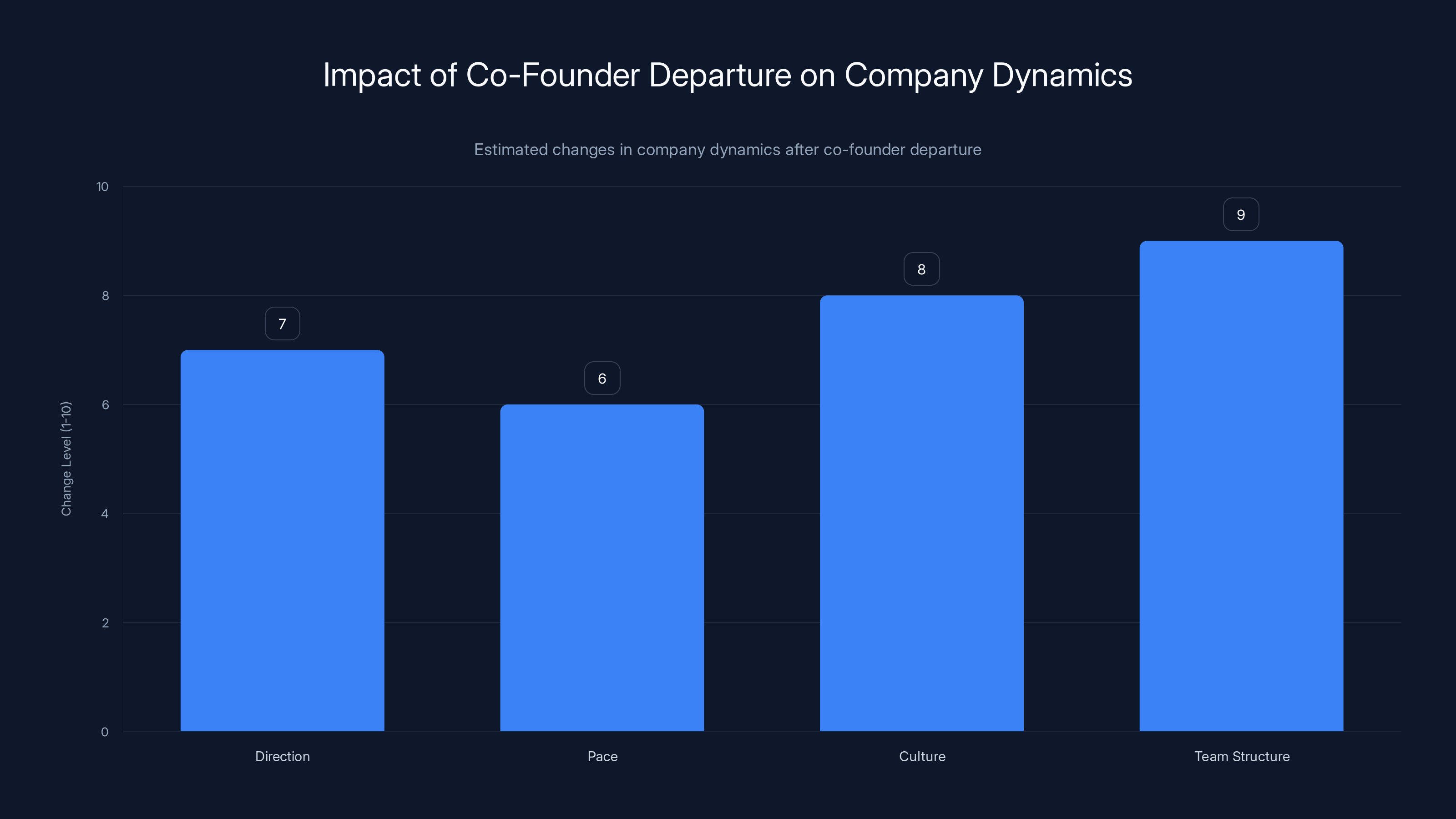

Estimated data shows significant changes in company direction, pace, culture, and team structure after co-founders' departure, indicating a major shift in company dynamics.

The Broader Trend: AI Talent Staying at Scale

The departures from Thinking Machines fit into a larger pattern in the AI industry: top talent increasingly stays at the companies that are already winning.

For a decade, the narrative was that top talent would leave Google and Facebook to start AI startups. Yann Le Cun stayed at Facebook. Ilya Sutskever stayed at Open AI, then founded SAFE. The story was that big companies were too slow to move fast.

But somewhere around 2023 and 2024, that narrative started to shift. Big companies realized they were losing talent to startups and decided to fight back. They doubled down on their technical missions. They gave more autonomy. They moved faster. They became better places to do cutting-edge AI work.

Meanwhile, startups realized that building AI from scratch is brutally hard. You need scale to compete. You need data. You need infrastructure. You need institutional knowledge.

So now the trend is reversing. Top talent that left the big players is slowly coming back. Not because they failed at the startups, but because the big players figured out how to keep them engaged and moving fast.

Thinking Machines is a data point in that trend. It's not the only one. But it's an important one because it happened so visibly and so quickly.

What Happened Next: The Aftermath

After Zoph, Metz, and Schoenholz left, Murati was left leading a company with a different team. The company still exists. It still has funding. It still has a mission. But it fundamentally changed shape.

This is an important point: companies can survive losing co-founders. But they change. The direction might shift. The pace might shift. The culture might shift. When you lose two of three co-founders, you're essentially building a new company with the same name and funding.

Murati presumably rebuilt the team. She presumably hired other excellent researchers. The $2 billion in funding is still there. The mission is still there. But the company operating in 2025 is not the company that was founded in 2024 with Zoph and Metz as co-founders.

That's not necessarily bad. Pivots happen. Teams change. Companies evolve. But it's a reset, and resets are expensive in time and momentum.

The Broader Context: Why AI Startups Are Hard

Zoph, Metz, and Schoenholz's departure from Thinking Machines isn't a failure of will or intelligence. These are brilliant people making a rational choice. It reveals something deeper: in 2025, building an AI startup is genuinely difficult because the incumbent players have become incredibly strong.

Open AI has Chat GPT. It has GPT-4. It has an API with billions in annual usage. It has access to the world's largest companies as partners. It has brand recognition. It has credibility. It has momentum.

Starting a company against that is a monumental task, even with $2 billion in funding. You're not competing on money. You're competing on vision, on execution speed, on ability to attract talent, on technical breakthroughs.

You can win at that competition—Anthropic is proof that you can. But it's not easy, and it requires genuine founder alignment and commitment.

Looking Forward: What Changes After This

The AI industry learned something from what happened to Thinking Machines. Future founders will be more careful about founder selection. Future co-founders will think harder about committing to startups. Future investors will ask harder questions about founder incentive alignment.

This is the kind of event that changes incentives at the margin. It won't stop people from starting AI companies. But it will make them think more carefully about whether they're truly aligned with their co-founders before they start.

It will also make big players like Open AI more confident that they can reclaim talent if needed. They have compute, they have momentum, they have products, and they have proof that their approach works. When key talent gets uncertain about a startup, Open AI is right there.

For the next generation of AI startups, the lesson is clear: you need to either move faster than the incumbents, or you need a genuinely novel technical or business approach that the incumbents can't replicate. Moving on capital alone isn't enough. Moving on talent alone isn't enough. You need conviction, alignment, and momentum.

Thinking Machines had capital. It had talent. It didn't have sustained momentum or absolute conviction from all co-founders. That gap was fatal to the original team configuration.

Estimated data shows that AI startups in 2025 face significant challenges compared to established companies like OpenAI, particularly in terms of compute and data access.

The Human Element: Why People Actually Leave Startups

Underlying all of this analysis is a simple human reality: people leave when they lose faith.

Zoph, Metz, and Schoenholz didn't leave Thinking Machines because they were passive-aggressive or because they got a financial offer they couldn't refuse (Open AI's compensation was probably comparable). They left because they probably lost faith that the company was going to achieve what they hoped it would achieve.

Maybe they realized the technical direction was wrong. Maybe they realized the market was smaller than they thought. Maybe they realized they weren't aligned with Murati on the vision. Maybe they realized they missed working on the cutting edge of AI capability at Open AI.

When senior people leave a company, it's almost always about one of those things. It's not about money. It's about faith.

This is why CEO messaging is so important. This is why alignment is so important. This is why vision needs to be clear and compelling. When your team loses faith in the vision, they'll leave, even if you have unlimited capital.

Murati faced a real challenge: how do you maintain faith in your team when key team members are losing faith themselves? It's a hard problem with no easy answer.

What Thinking Machines Learned: Rebuilding After Loss

After the departures, Thinking Machines had to rebuild. The company needed to answer questions: Are we still pursuing the same mission? Are we still going to be successful? Do we still have the team to execute?

The fact that Murati stayed and kept building suggests she still believed. But the shape of the company had changed. The team had changed. The narrative had changed.

Rebounding from something like this requires absolute clarity of vision and purpose. You have to say, "Here's why we're still going to win, and here's how we're going to do it." You have to be credible in that claim. And you have to execute relentlessly.

Some startups do this successfully. Some don't. It depends on founder conviction, on whether the underlying idea is sound, on whether you can rebuild momentum.

The Role of Timing: Being Early vs. Being Late

There's a timing element to all of this as well. Thinking Machines launched in early 2024. At that moment, generative AI was still incredibly hot. There was still a perception that the space was wide open, that there were multiple ways to win.

But by mid-2024, some of that narrative was starting to change. Open AI was clearly pulling ahead. Claude was becoming more formidable. Gemini was improving. The bar for success kept getting higher.

Zoph and Metz, who were inside Open AI, knew exactly how fast Open AI was moving. They probably realized that staying ahead of Open AI was going to be harder than they initially thought. At that point, the decision calculus shifts. Do you stay and fight against increasingly long odds, or do you go back to the company that's clearly winning?

Founder Optionality: A Feature or a Bug?

One interesting question is whether having optionality is good or bad for a startup. On one hand, optionality is good—you want founders who have choices, because it means they're choosing to be there out of conviction.

On the other hand, if optionality is too high, founders will leave when things get hard. And building a startup is always hard, especially early on.

Zoph, Metz, and Schoenholz probably had high optionality. They could have stayed at Open AI. They could have started their own thing. They could have joined other companies. That optionality is good in one sense—it means they're choosing to commit.

But it's also bad, because if things get hard and they lose faith, there's nothing keeping them there. No path dependence, no sunk costs, no obligation.

Murati, by contrast, had lower optionality. She'd left her CTO role. She'd burned bridges. She had to make the startup work. So she stays.

This suggests that future founders should think carefully about the optionality of their co-founders. Do they have real skin in the game? Have they made real sacrifices to join? Or are they still hedging their bets?

Clarity of mission and speed of execution are critical for AI startup success, followed by founder commitment and talent retention. Estimated data based on narrative insights.

The VC Perspective: What Investors Learned

Andreessen Horowitz, which led the funding round for Thinking Machines, is one of the most sophisticated investors in the world. They've seen startups succeed and fail. They know what founder alignment looks like. They know what momentum looks like.

The question is: should they have seen this coming? Should they have noticed that not all co-founders were equally committed?

It's possible that they did see warning signs and invested anyway, betting that the capital and the mission would be enough to make it work. It's also possible that they missed some signals.

Either way, this is probably a learning moment for investors. When evaluating AI startups founded by people from the big players, look hard at founder alignment. Look at what each founder gave up. Look at how committed they are. That information is more valuable than the funding round size or the valuation.

Comparing to Anthropic: Why Some Founders Stay

Anthropic is the obvious comparison here. Dario Amodei and Daniela Amodei also left Open AI. So did Chris Olah, Sam Mc Candlish, and others. But Anthropic has not experienced the kind of co-founder exodus that Thinking Machines did.

Why? The most obvious answer is that Anthropic had a clearer vision. They knew they were building a company focused on AI safety and alignment. They knew it would be difficult. They knew they were going against Open AI's scaling-first approach.

But they had absolute conviction in that vision. And they communicated it clearly. So when things got hard—and they did get hard—the co-founders stayed because they believed in the mission.

Thinking Machines had a mission, but it was less clear. "Interpretable AI" is good, but it's not as compelling as "build AI safely." It's not as galvanizing. It doesn't inspire the same kind of commitment.

This is a key lesson: your mission and vision need to be specific enough and compelling enough that co-founders will stay through the hard times. If your mission is vague, you'll lose co-founders when things get tough.

The Paradox of Well-Funded Startups

Here's a paradox worth noting: Thinking Machines was extremely well-funded. It had more capital than it knew what to do with. That capital should have made it more likely to succeed, not less.

But in some ways, the capital created problems. It created optionality for the team. It created multiple directions to pursue. It made it possible to avoid making hard choices about what the company's focus should be.

Startups with limited capital have to be laser-focused. Every dollar matters. Every hire matters. Every technical choice matters. There's no room for vagueness.

Startups with massive capital can be more exploratory. They can pursue multiple paths. They can hire broadly. But that exploration can become confusion. And confusion can cause people to lose faith.

This suggests that for founders, capital is a double-edged sword. You need enough to execute. But you don't necessarily benefit from more capital than you need. Constraints create focus. Unlimited capital can create drift.

What About the Remaining Team?

When Zoph, Metz, and Schoenholz left, there were other people at Thinking Machines. There were engineers, researchers, and staff. What happened to them?

Their experience probably shifted. They probably went from working at an exciting startup with massive funding and world-class co-founders to working at a startup that had lost two co-founders. That's a significant shift in identity and morale.

Some of them probably left. Some probably stayed and helped rebuild. The ones who stayed probably became more committed because they had to become, by necessity, more central to the company's mission.

This is one of the underexamined impacts of co-founder departures: the secondary effects on the rest of the team. It affects recruiting, it affects retention, it affects the narrative around the company.

The Narrative Shift: From Inevitable to Uncertain

Before the departures, Thinking Machines was framed as inevitable. It was the latest venture from a talented crew from Open AI. It had massive funding. It had a big mission. It was going to change the world.

After the departures, the narrative shifted. It became a cautionary tale. It became a demonstration of how hard startup building is. It became evidence that even massive capital and talented people can't guarantee success.

That narrative shift is important because narratives drive recruiting, drive customer interest, drive investor confidence. When the narrative shifts from "inevitable success" to "uncertain outcome," everything becomes harder.

This is why maintaining momentum is so critical for startups. Momentum drives narrative. Narrative drives recruiting. Recruiting drives execution. Execution drives momentum. It's a flywheel.

When you break the flywheel by losing co-founders, it takes real work to rebuild it.

Looking at the Broader AI Market

In context of the broader AI market, Thinking Machines' struggles reveal something important: the market for AI startups has consolidated. The winners (Open AI, Anthropic, and a few others) are pulling ahead. They're building momentum. They're becoming harder to compete against.

There's still room for AI startups, but that room is in specific niches: building on top of existing models, applications in specific verticals, infrastructure for specific use cases. The room for "build a general AI company from scratch" is shrinking.

This is a natural market dynamic. The most valuable segments consolidate. The frontier is always moving. But for startups, it means the path to victory is narrower than it was two years ago.

The Human Story: Why This Matters Beyond Business

Beyond the business analysis, there's a human story here. Murati took a real risk leaving Open AI. She put her reputation on the line. She convinced talented people to join her. She raised enormous capital.

Then two of her co-founders left, and she had to keep going. That's hard, psychologically and professionally.

Zoph, Metz, and Schoenholz also faced a hard choice. They'd joined a startup, which is risky. They'd worked for several months. Then they realized it wasn't the right fit, and they had to make the call to leave. That's also hard.

This is the human dimension of startup building that doesn't always make it into the narrative. It's not all about clever business strategy. It's about people making real choices with real consequences.

Lessons for People Considering Joining Startups

If you're thinking about leaving a stable job at a big company to join a startup, what do you learn from what happened to Thinking Machines?

First: founder alignment matters more than you think. Meet with all your co-founders. Do they agree on the mission? Do they seem committed? Are they willing to make sacrifices?

Second: clarity of mission is important. If the company's mission is vague, it's going to be hard to maintain conviction when things get hard.

Third: execution speed matters. The faster you can ship something real, the faster you can generate momentum and belief. If you're just strategizing and hiring for months without shipping, morale will erode.

Fourth: consider what you're giving up. If you're leaving a role with a lot of prestige or responsibility, you're giving up something real. Make sure the startup opportunity is worth it.

Fifth: keep your optionality in mind. If you have very high optionality (could easily go back to a big company), you might be more likely to leave if things get hard. Think about how committed you're really going to be.

What Happens Now: The Future of Thinking Machines

Thinking Machines still exists. It still has funding. It still has a mission. But it's a different company than the one that was founded in 2024.

The question going forward is whether Murati can rebuild the company, recruit new talent, execute on a vision, and create something valuable. Many startups have lost co-founders and gone on to succeed. It's not impossible.

But it is harder. It requires absolute conviction. It requires the ability to recruit and retain new talent. It requires the ability to generate momentum and show traction.

We don't yet know how that story ends. But what we do know is that the departure of Zoph, Metz, and Schoenholz changed the trajectory of the company in important ways.

The Broader Ecosystem Impact

Beyond Thinking Machines specifically, this exodus probably had effects on the broader AI startup ecosystem. It probably made some people think twice about leaving big companies to join startups. It probably made some investors more cautious about funding startups founded by ex-employees of big AI companies. It probably made some big AI companies more confident that they could retain talent if they needed to.

All of those effects ripple through the ecosystem and affect decision-making at the margin. Maybe not dramatically, but enough to matter.

FAQ

Why did Zoph, Metz, and Schoenholz leave Thinking Machines Lab?

While the exact reasons were never stated publicly, the departures likely resulted from misalignment on company mission, uncertainty about technical direction, or recognition that building competitive AI from scratch was more challenging than anticipated. These researchers had significant experience at Open AI and had access to compute, talent, and momentum that a startup couldn't match in the early stages. Their decision to return to Open AI suggests they felt greater conviction about that organization's path forward.

How common are co-founder departures in AI startups?

While co-founder departures happen regularly in startups across all industries, the simultaneous departure of two out of three co-founders within a year is unusual and notable. It typically signals deeper issues with founder alignment, mission clarity, or the viability of the initial thesis. In the AI space specifically, the phenomenon is becoming more common as startup founders realize that competing against well-established players like Open AI, Anthropic, and Google requires extraordinary execution and conviction.

What does this mean for other AI startups?

The Thinking Machines situation reveals that massive capital alone doesn't guarantee startup success, especially in AI where incumbents have significant advantages in compute, data, and institutional knowledge. Other AI startups can learn that founder alignment is more critical than funding size, that mission clarity must be specific and compelling, and that execution speed and early momentum are essential for maintaining team conviction through difficult periods.

Could Thinking Machines have prevented these departures?

Potentially, yes. Had Murati, Zoph, and Metz aligned more explicitly on technical direction and company strategy before fundraising, had they created mechanisms to surface and resolve disagreements quickly, or had they generated early momentum through shipped products, the outcome might have been different. Additionally, founder vesting schedules and lock-up periods could have created different incentives. However, no structure can overcome fundamental misalignment on vision and direction.

What does Open AI's ability to reclaim talent tell us about the company?

Open AI's successful recruitment of Zoph, Metz, and Schoenholz demonstrates the company's strong position in the AI market. It shows that Open AI has momentum, clear direction, access to exceptional compute resources, and the ability to offer work on cutting-edge problems that rival or exceed what a startup can offer. It also suggests that Open AI has maintained relationships with departed employees and can make compelling cases for their return, which reflects strong organizational culture and vision.

Should investors have seen this coming?

More cautious investors might have looked deeper into founder commitment and alignment before leading a $2 billion funding round. Red flags could have included differences in what each founder sacrificed to join, ambiguity in mission articulation, and the lack of early shipped products or traction. However, even sophisticated investors sometimes miss signals, and founder departures remain genuinely difficult to predict.

What happens to the $2 billion in funding?

The capital remains available to Thinking Machines to pursue its mission and rebuild its team. The loss of co-founders doesn't immediately consume the funding, though it does change how efficiently that capital can be deployed. Teams take longer to form, decisions may move more slowly, and recruiting becomes more challenging when a startup loses key founders.

How does this compare to Anthropic's experience?

Anthropic was founded by ex-Open AI employees but has not experienced significant co-founder departures. The key difference appears to be mission clarity and founder conviction. Anthropic had a clear, specific mission around AI safety and alignment that founders could articulate and rally around. Thinking Machines' mission around interpretability was less crystalline and perhaps less compelling to early team members when tested against the realities of execution.

Will Thinking Machines survive this setback?

Companies can and do survive the loss of co-founders. The question is whether Murati can maintain conviction, recruit excellent replacement talent, generate early momentum through shipped products, and create clarity around the company's mission and technical approach. It's not impossible, but it requires flawless execution and genuine belief in the vision from the remaining leadership.

What should future startup founders learn from this?

Future founders should prioritize founder alignment and mission clarity over capital size. They should think carefully about the opportunity cost each co-founder is accepting by joining. They should commit to shipping products and generating traction quickly rather than spending months hiring and strategizing. They should have explicit conversations about what happens if founders lose faith in the mission. And they should recognize that incumbents will always be able to offer compelling alternatives, so the startup's mission must be genuinely more compelling than what those incumbents can offer.

Key Takeaways

- Two co-founders (Zoph and Metz) departed Thinking Machines Lab within a year to rejoin OpenAI, along with another researcher (Schoenholz)

- The departure reveals that massive capital ($2 billion) alone cannot guarantee startup success if co-founders lack alignment on mission and vision

- Incumbent companies like OpenAI maintain gravitational pull through momentum, compute access, proven technical leadership, and clear organizational mission

- Founder commitment varies based on what each co-founder sacrificed to join, affecting likelihood they'll stay during difficult periods

- AI startups must generate early momentum through shipped products and crystal-clear mission statements to retain world-class talent against incumbent competition

- The parallel success of Anthropic (which retained co-founders despite being from OpenAI) demonstrates that clear vision and specific mission matter more than capital

Related Articles

- Over 100 New Tech Unicorns in 2025: The Complete List [2025]

- SandboxAQ Executive Lawsuit: Inside the Extortion Claims & Allegations [2025]

- Where AI Startups Win Against OpenAI: VC Insights 2025

- xAI's $20B Series E: What It Means for AI Competition [2025]

- Meta Acquires Manus: The $2 Billion AI Agent Deal Explained [2025]

- OpenAI's Head of Preparedness Role: AI Safety Strategy [2025]

![Why Thinking Machines Lab Lost Its Co-Founders to OpenAI [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/why-thinking-machines-lab-lost-its-co-founders-to-openai-202/image-1-1768444628323.jpg)