Wikimedia's AI Partnership Strategy: Why Big Tech Is Now Paying for Wikipedia

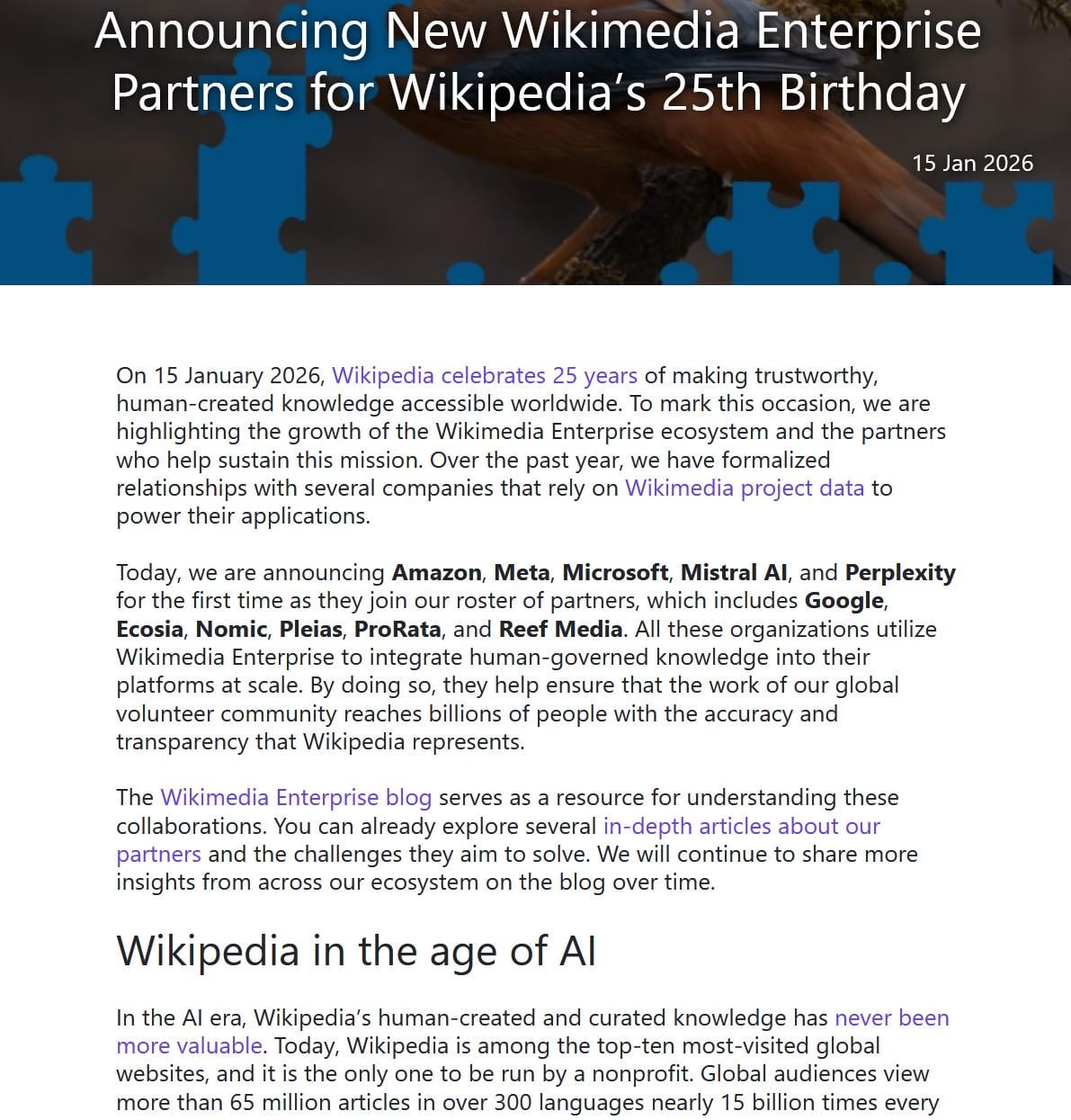

Wikipedia just hit its 25th anniversary, and it's celebrating in a way that would've seemed unthinkable five years ago: by charging tech giants for access to its content. The Wikimedia Foundation announced a wave of enterprise partnerships with heavy hitters like Meta, Microsoft, Amazon, Google, and Perplexity. These aren't charitable relationships. These are commercial deals where some of the world's richest companies are now paying for streamlined, high-throughput access to Wikipedia's 65 million free articles.

It's a fascinating pivot for an organization built on the principle that knowledge should be free. But here's the thing: Wikimedia isn't abandoning that mission. Instead, they're forcing the companies building AI systems to acknowledge an uncomfortable truth: scraping Wikipedia at scale has real costs, and those costs shouldn't fall solely on a nonprofit organization with a fraction of their budget.

This shift reveals something much bigger about how AI systems work in 2025. Every major chatbot, every search engine, every AI tool that sounds intelligent is standing on the shoulders of human-curated knowledge. Wikipedia was always the foundation, but for years, companies treated it like free training data. Now they're paying for the privilege. Understanding why, and what it means for AI's future, requires digging into the economics, the technology, and the uncomfortable reality of how dependent modern AI actually is on human expertise.

Let's break down what's actually happening here, why it matters, and what comes next for AI infrastructure.

TL; DR

- Wikimedia announced enterprise partnerships with Meta, Microsoft, Amazon, Google, and others, giving these companies paid access to high-throughput APIs for Wikipedia content

- Big Tech now pays for Wikipedia access because scraping at scale was driving up server costs and threatening the nonprofit's financial sustainability

- High-throughput APIs allow AI systems to access Wikipedia data efficiently without overloading servers or violating terms of service

- This validates AI's dependence on human-curated data, proving that even the most advanced language models need quality training material

- The model is expanding to include other Wikimedia projects like Wikivoyage, Wikibooks, and Wikiquote, creating a broader enterprise data platform

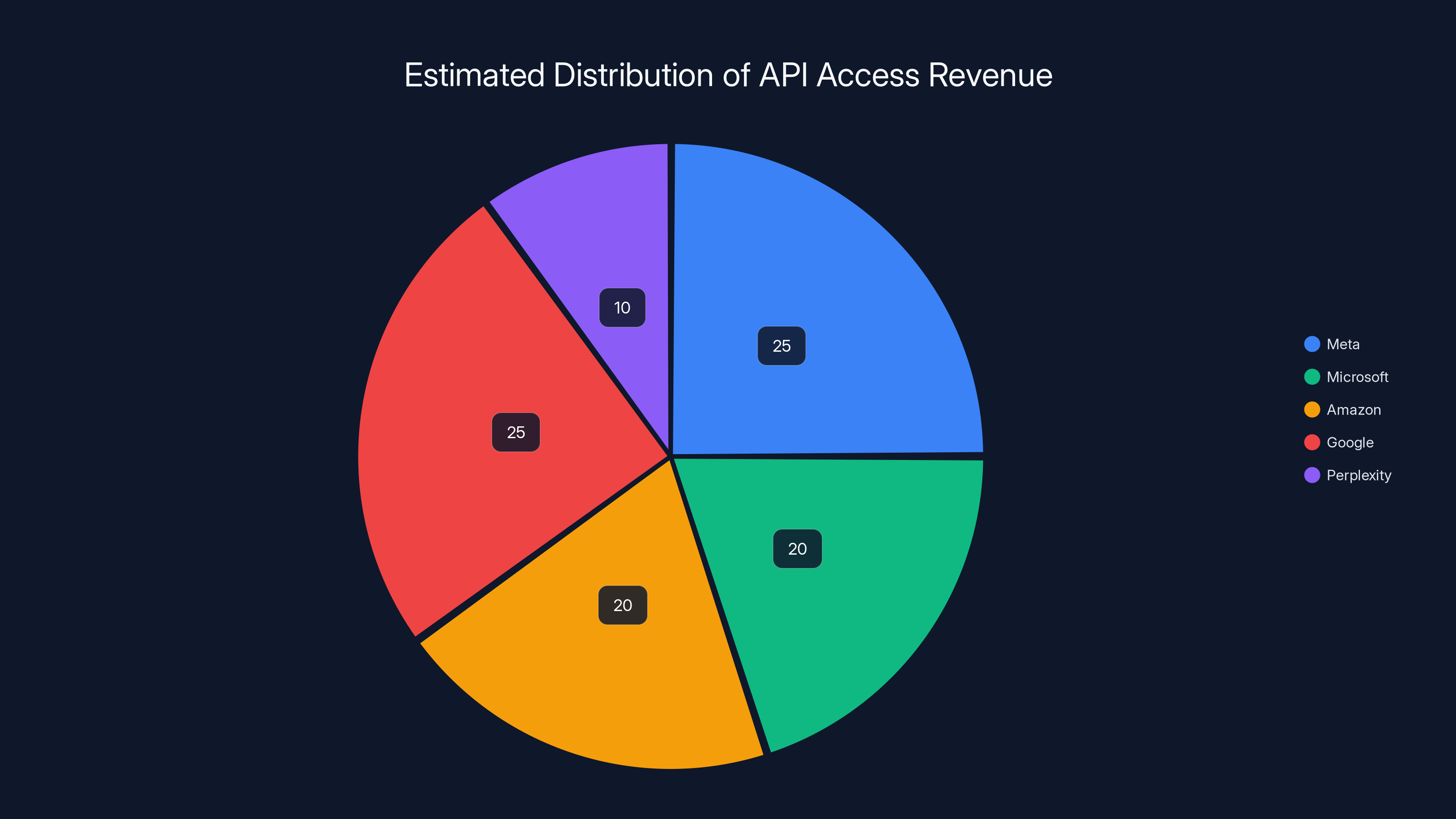

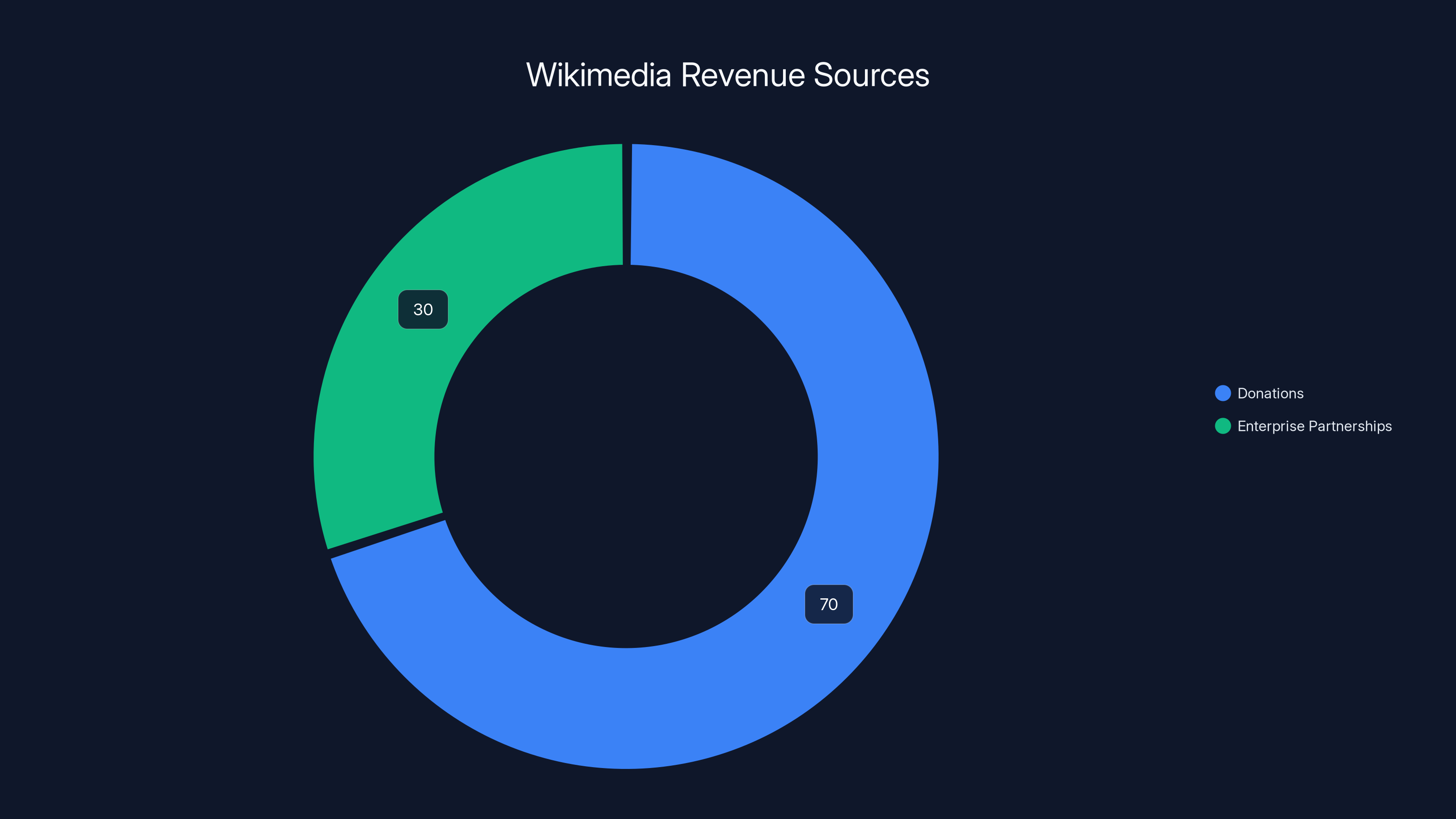

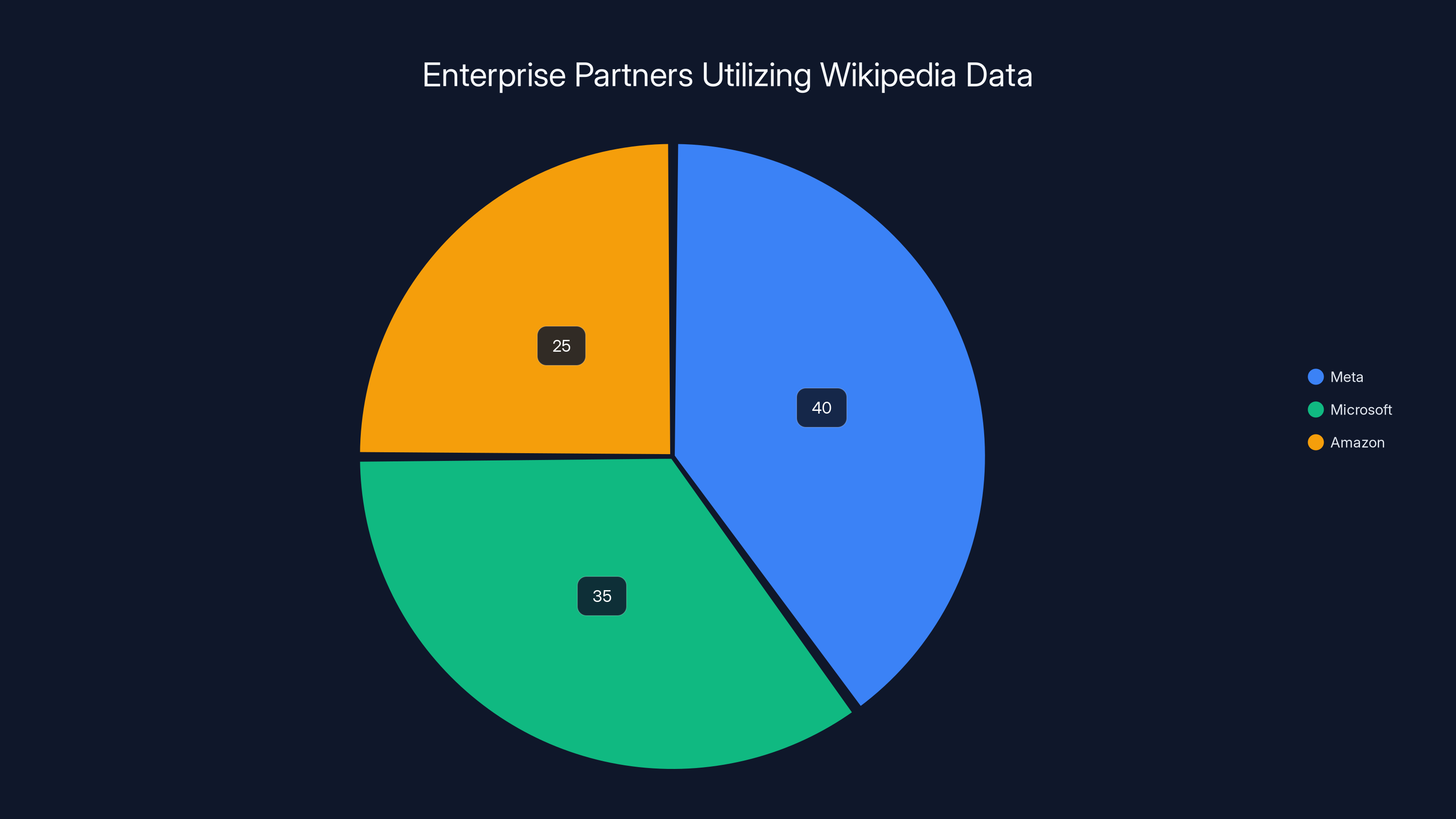

Estimated data showing potential revenue distribution from Wikimedia's enterprise API partnerships. Larger tech companies like Meta and Google might contribute more due to higher data throughput needs.

Why Wikimedia Needed This Deal: The Real Economics of AI Scale

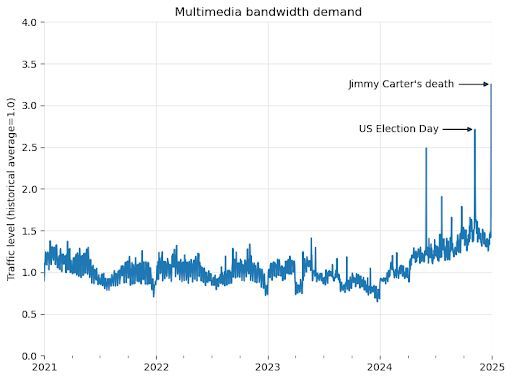

Here's the uncomfortable truth that most people miss: training AI systems is expensive, but serving them at scale is even more expensive. When Meta's servers make requests to Wikipedia millions of times per day, those requests consume bandwidth, CPU cycles, and disk I/O. Scale that across dozens of companies, and you're looking at infrastructure costs that dwarf Wikimedia's entire annual budget.

For years, Wikimedia tolerated this. The organization's founding principle was radical openness: knowledge should be free, accessible to everyone, funded by donations. That model worked great when Wikipedia was serving readers. But when AI systems started treating Wikipedia like an unlimited training data buffet, the economics broke down entirely.

Let me put some numbers on this. Wikimedia runs on roughly $150 million per year in donations. That sounds substantial until you realize it covers servers, staff, security, legal compliance, and engineering across hundreds of thousands of pages served per second. A single company making millions of API calls per day? That could easily cost thousands of dollars monthly in infrastructure. Multiply that by ten companies, and suddenly you're talking about significant operational strain.

The organization sounded the alarm publicly in 2024, warning that reduced traffic from AI summaries could threaten their financial model. Here's the logic: if people stop clicking through to Wikipedia because Claude or Chat GPT gives them answers without requiring a visit, Wikipedia's traffic drops. Lower traffic historically means fewer donations from users who feel a connection to the site. Fewer donations means less funding for servers, engineers, and expansion.

But there's another dimension people often overlook. When AI companies scrape Wikipedia at massive scale, they're not just consuming bandwidth. They're extracting value. They're using Wikimedia's quality-control infrastructure, its volunteer editors, its fact-checking mechanisms, and its reputation. Essentially, they're outsourcing the most expensive part of AI training: data curation and validation.

Think about it this way. If you had to manually verify facts for your AI system, you'd need thousands of human experts. But Wikipedia already did that work. Its edit history, its source citations, its talk pages where editors debate accuracy—all of that represents millions of hours of volunteer labor. When companies use that data to train commercial AI systems that generate billions in revenue, they're profiting from work they never funded.

This partnership approach finally addresses that mismatch. Now the companies generating the most value from Wikipedia are contributing to its sustainability. It's not charity. It's fair compensation for the infrastructure and intellectual work that made their AI systems possible.

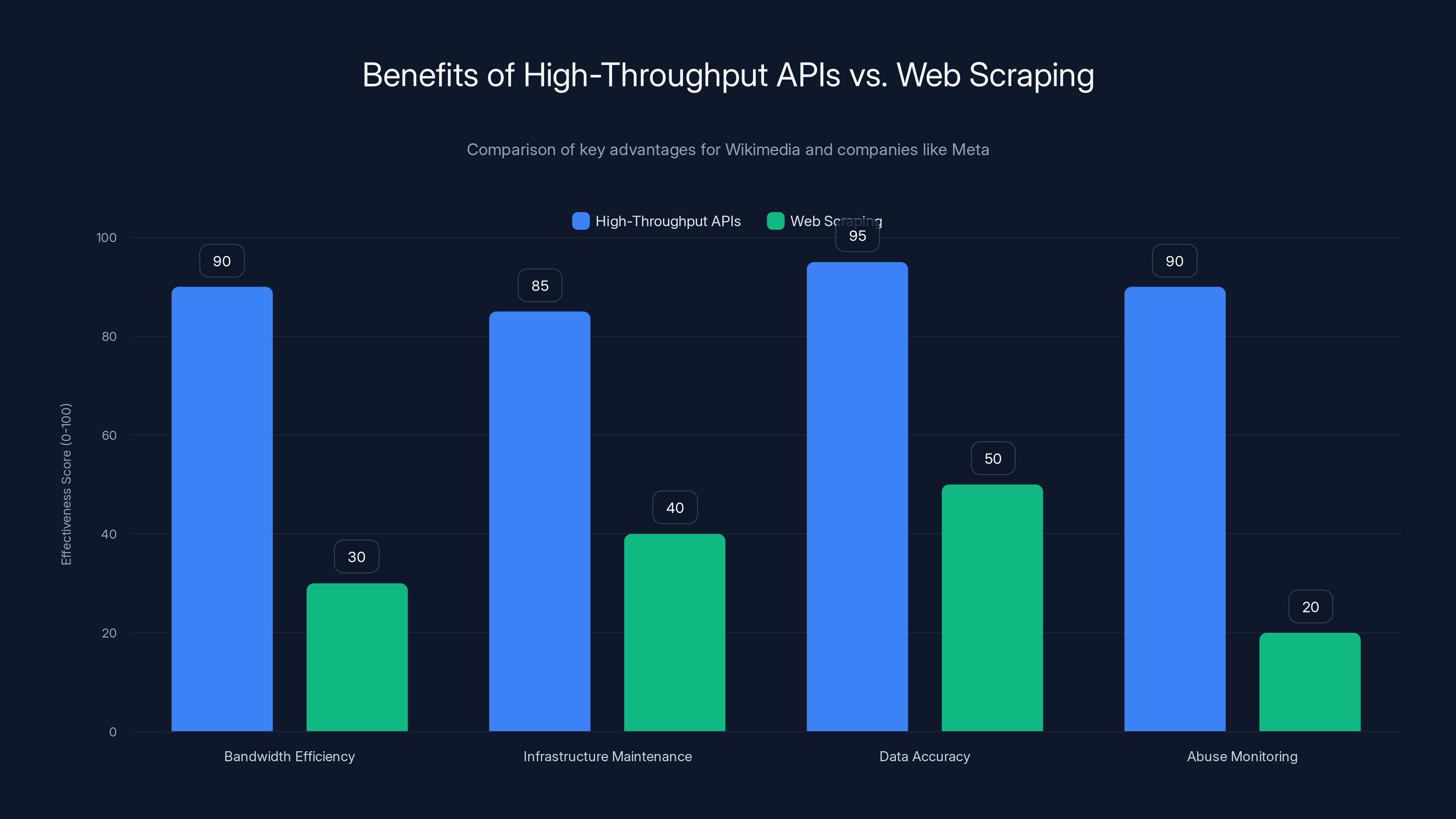

High-throughput APIs significantly outperform web scraping in terms of bandwidth efficiency, infrastructure maintenance, data accuracy, and abuse monitoring. Estimated data based on typical advantages.

Understanding High-Throughput APIs: The Technical Solution

Let's talk about what these companies are actually buying. The enterprise partners now have access to Wikimedia's high-throughput APIs. If that sounds technical, it's because it is. But understanding what an API does here is essential to understanding why this deal matters.

At its core, an API (Application Programming Interface) is just a structured way for computer systems to request information from each other. Without an API, a company like Meta would scrape Wikipedia by simulating a human browser visit: load the page, extract the HTML, parse the text, repeat millions of times. That's crude, inefficient, and burns enormous amounts of bandwidth because you're downloading everything a human user would see, plus all the CSS, Java Script, and images.

A high-throughput API is different. It's optimized specifically for computer-to-computer communication. Instead of downloading entire HTML pages, the API returns just the data the client needs, in a structured format like JSON. It handles rate limiting intelligently, queues requests efficiently, and reduces overhead dramatically.

For Wikimedia, offering an API instead of letting companies scrape has major advantages. First, they can monitor exactly what's being requested, how often, and by whom. That transparency is crucial for protecting against abuse. Second, APIs allow Wikimedia to optimize their infrastructure for this use case. They can deploy caching layers, distribute load across servers, and handle traffic spikes more gracefully. Third, they can update the API when Wikipedia's data structures change, without breaking every scraper that companies built.

For companies using the API, the benefits are equally significant. Meta doesn't want to maintain scraping infrastructure that breaks every time Wikipedia's HTML structure changes. They don't want to consume 10x more bandwidth than necessary. They don't want to get blocked by Wikimedia's abuse detection systems. An API solves all of that. It's cleaner, faster, more reliable, and contractually legitimate.

The architecture here is worth understanding in more detail. A typical high-throughput API setup for Wikipedia would include several layers:

The API Gateway Layer: This is the entry point. When Meta's servers make a request, they hit the gateway first. The gateway authenticates them (verifies they have a valid API key), checks rate limits, and routes the request to the appropriate backend service. This prevents any single client from monopolizing resources.

The Caching Layer: Wikipedia data doesn't change every millisecond. Most articles are updated occasionally, not constantly. So the API can cache frequently-requested articles in memory, serving them instantly without hitting the database. This is where most of the performance gains come from. A well-designed cache can serve 90% of requests from memory, reducing database load by an order of magnitude.

The Database Layer: Behind all the caching is the actual Wikipedia database. This is where the real data lives. It's typically split across multiple database servers, with replication for redundancy and failover. When a request can't be served from cache, the API queries the database. For content like article text, this is usually fast. For complex queries that require searching across millions of articles, it can take longer.

The Search and Indexing Layer: This is often separate from the main article storage. Most API requests probably ask simple questions: "Give me article X." But some requests are more complex: "Find all articles about 20th-century literature modified in the last month." That requires a search index, usually powered by technology like Elasticsearch or similar systems designed for full-text search at scale.

The entire system is designed to handle hundreds or thousands of requests per second, each completing in milliseconds. That's dramatically more efficient than having companies scrape, and it's why Wikimedia can actually make this work economically.

The Enterprise Partners: Who's Paying and Why

Let's talk about who actually signed these deals and what they're getting out of it. The announced partners include some obvious names and some surprising ones.

Meta and Threads: Meta runs some of the largest AI systems on the planet. Between building large language models internally and integrating AI across Instagram, Facebook, and now Threads, they need enormous amounts of training data. Wikipedia's 65 million articles, each with citations and edit histories, represent incredibly high-quality text data. Unlike random internet text, Wikipedia articles are fact-checked, well-structured, and curated. That matters enormously when you're training systems that need to be accurate.

For Meta, paying for API access is trivial compared to the alternative: maintaining their own internal text corpus or paying data brokers for access. Plus, they get the legal clarity of a proper licensing agreement. When Meta's legal team asks "Can we use this data for training?", the answer is now unambiguously yes, because they've signed an agreement.

Microsoft and Copilot: Microsoft has been aggressive about embedding AI into everything. Copilot appears in Windows, Office, Edge, and numerous enterprise products. Each of these systems benefits from accurate factual information. When someone asks Copilot a question, it needs to provide accurate answers. Wikipedia is one of the most reliable sources for that purpose. The partnership likely helps Microsoft both with training and with real-time fact-checking during inference.

Microsoft's interest makes sense from another angle too: they're increasingly interested in enterprise AI. Organizations paying for premium Copilot access expect high-quality responses. Having direct, reliable access to Wikipedia data helps Microsoft deliver that quality at scale.

Amazon: Less obvious than Meta or Microsoft, but Amazon's interest makes perfect sense when you understand their cloud ambitions. AWS offers various AI services, and they want to be competitive with Open AI, Google, and others. Training data is a core input. Plus, Amazon has retail and logistics systems that could benefit from better product information, which often comes from Wikipedia. The partnership supports both their AI ambitions and their existing business.

Google: This is interesting because Google created Google Search, which has always had a complex relationship with Wikipedia. Google links to Wikipedia extensively, which drives traffic, but Wikipedia's quality makes people less likely to click on other search results. The partnership signals that Google is focused on their AI products now, particularly their Gemini system, and wants reliable training data for those products.

Perplexity: This is the most interesting partner because Perplexity is explicitly a Wikipedia-dependent company. The entire Perplexity experience is built on synthesizing information from multiple sources and citing them. Perplexity's search results often include direct Wikipedia references. Having a formal partnership with Wikimedia helps Perplexity scale their infrastructure and ensures they have reliable, predictable access to data they fundamentally depend on.

What's remarkable here is the diversity of companies willing to pay. This isn't just language model companies. This includes Meta (social media plus AI), Microsoft (software and cloud), Amazon (e-commerce and cloud), Google (search and AI), and Perplexity (search and AI). The common thread? They all have AI systems in production that rely on high-quality factual information.

The deal terms themselves aren't public, which is appropriate for commercial agreements. But Wikimedia indicated that pricing is based on throughput, meaning companies pay more the more data they request. This creates the right incentives: efficient companies that cache data and minimize requests pay less, while companies that make redundant or inefficient requests pay more.

Estimated data shows how increasing numbers of AI companies using Wikimedia's API can significantly raise monthly infrastructure costs, potentially straining Wikimedia's budget.

The Broader Wikimedia Ecosystem: Beyond Wikipedia

Here's something people often miss when they read about this deal: it's not just about Wikipedia. Wikimedia maintains an entire ecosystem of knowledge projects. The partnerships give companies access to all of them.

Wikivoyage is a travel guide built on the same collaborative model as Wikipedia. It contains detailed information about destinations, attractions, hotels, restaurants, and travel logistics. For companies building travel AI, recommendation systems, or planning tools, Wikivoyage is valuable data. It's curated by travel enthusiasts who have actually visited these places, not just generated from web scraping.

Wikibooks is a collection of open textbooks and educational materials. Everything from physics to mathematics to programming languages. For educational AI systems, this is invaluable. It's structured, pedagogically sound, and covers topics deeply rather than superficially.

Wikiquote is a collection of famous quotations, organized by author and topic. Smaller than Wikipedia, but useful for systems that need to understand what notable people have said about various topics.

Wiktionary contains definitions, etymologies, and usage examples for words across dozens of languages. For natural language processing systems that need to understand word meanings and relationships, this is crucial data.

Wikimedia Commons is a repository of freely-licensed images, audio, and video. Companies building multimodal AI systems that need to understand relationships between text, images, and media benefit from this significantly.

The genius of expanding the partnership beyond Wikipedia is that it creates a comprehensive knowledge infrastructure for AI. Instead of companies scraping ten different sources and trying to reconcile conflicts, they can now get structured, consistent, citable data from a single, reliable source.

This also protects the broader Wikimedia ecosystem. Wiktionary and Wikivoyage were already being scraped at scale, but they don't have Wikipedia's visibility or fundraising base. Including them in the enterprise partnership means these smaller but valuable projects get their infrastructure needs funded, ensuring they can continue growing and improving.

The Financial Model: How This Actually Sustains Wikipedia

Let's get concrete about the economics here. The enterprise partnerships solve real problems for Wikimedia, but understanding how requires looking at their financial model.

Wikimedia's revenue historically came almost entirely from donations. Wikipedia's annual fundraising campaigns generate somewhere in the range of $100+ million per year. That's substantial, but it means a large fraction of Wikimedia's staff, servers, and operations depend on convincing people to donate when they visit Wikipedia.

The problem is obvious: if AI systems reduce Wikipedia traffic, donations decline. If donations decline, infrastructure investment drops. If infrastructure investment drops, Wikipedia's quality suffers (slower servers, fewer features, less support for editors). That's a death spiral.

The enterprise partnerships disrupt that spiral. Instead of relying entirely on individual donations, Wikimedia now has commercial revenue. And it comes from the companies most directly benefiting from Wikipedia's existence: the AI companies using it for training and inference.

Let's think about the scale. A company like Meta probably makes millions of API requests per day to Wikipedia. If Wikimedia charges even a fraction of a cent per request (and they likely charge more), that adds up quickly. A million requests at even

But there's a deeper point here about incentives. When enterprises pay for API access, they have contractual guarantees about availability and performance. Wikimedia has economic incentive to maintain and improve infrastructure. They have revenue to hire engineers specifically focused on API performance. They can invest in caching, redundancy, and disaster recovery.

Donation-funded organizations struggle with this because donors care about mission, not infrastructure. But companies paying for service care deeply about reliability. That's actually healthy pressure that drives better engineering.

There's also an interesting sustainability angle. Wikimedia now has revenue that's not dependent on traffic. If AI systems eventually reduce Wikipedia traffic significantly, Wikimedia's commercial revenue from API partnerships offsets the reduced donation income. That's genuinely significant from a long-term viability perspective.

The flip side is complexity. Wikimedia now has to operate as both a nonprofit mission-driven organization and a technology company serving enterprise clients. Those cultures can conflict. Managing API SLAs, handling billing disputes, and responding to enterprise support requests is very different from running a donation-funded operation. But it's a challenge that's worth solving.

Estimated data suggests that while donations still form the majority of Wikimedia's revenue, enterprise partnerships are becoming a significant source, potentially accounting for 30% of the total revenue.

The Scraping Problem: Why APIs Are Better Than Bots

To really understand why these partnerships matter, you need to understand the scraping problem they solve.

For years, companies scraped Wikipedia the hard way. Their systems would simulate human users: load the Wikipedia homepage, navigate to random articles, scrape the HTML, extract the text, repeat. Multiply this by thousands of concurrent connections from hundreds of servers, and you create enormous load on Wikipedia's infrastructure.

Wikipedia tried to manage this with rate limiting. The site's robots.txt file specifies how often bots can request pages. But enforcement is difficult. A determined company can just rotate through IP addresses, distribute requests across botnets, or make requests look like human traffic. It's a constant arms race.

Scraping also has quality problems. HTML is messy. When you extract text from Wikipedia's HTML, you get not just the article content but also navigation elements, ads (in Wikipedia's case, donation appeals), sidebar information, and sometimes template artifacts. Cleaning that up requires heuristics that occasionally fail. You might extract the wrong section, miss citations, or include markup.

APIs solve all of this by making the problem explicit. Instead of pretending to be a human user, companies authenticate with API keys. Instead of downloading HTML, they get structured data. Instead of hoping their scraping heuristics work, they get guarantees about data format and completeness.

Wikipedia benefits too. With an API, they know exactly what data is being requested, how frequently, and by whom. They can monitor for abuse patterns. They can implement intelligent caching. They can optimize their infrastructure specifically for API requests. They can version their API so changes to data structures don't break clients.

For Wikimedia, this shifts the relationship from an adversarial one (companies trying to scrape, Wikimedia trying to prevent it) to a cooperative one (companies paying for reliable access, Wikimedia optimizing service). That's better for everyone.

There's also an ethical dimension. Scraping treated Wikipedia as an unowned resource. Paying for access acknowledges that Wikimedia operates the infrastructure, employs people, and incurs costs. It's a small shift toward a more honest relationship between companies and the organizations they depend on.

Implications for AI Training: What This Means for Models

Now let's think about what this partnership structure implies for how AI systems are built going forward.

For years, AI training happened in the shadows. Companies would scrape Wikipedia, Common Crawl, Git Hub, and countless other sources. They'd combine all that data into massive corpuses, train models on them, and deploy the results. The data sources were acknowledged in footnotes if at all.

This partnership makes the relationship explicit. Companies are now licensing data, acknowledging its source, and paying for it. That has subtle but important implications for how they think about model training.

First, it raises questions about attribution and citation. If a model was trained on Wikipedia data licensed through the official partnership, the company should probably document that. Not just for legal reasons, but because it's honest. If users ask "Where does this information come from?", tracing back to Wikipedia is meaningful.

Second, it changes the incentive structure for quality. A company that's paying for data has incentive to use it well. They want to ensure their model actually learns from Wikipedia accurately, rather than just absorbing the raw text. This might push toward better training techniques, better evaluation, and better safety practices.

Third, it creates leverage for Wikimedia to maintain data quality. If Wikipedia's data quality suffers (because fewer people are editing, or editing standards decline), companies would be paying for lower-quality training material. This gives Wikimedia incentive to invest in the volunteer editor community, not just the infrastructure. Good editing practices directly translate to better training material and better company outcomes.

There's also a practical angle. Language models need current information. Wikipedia is frequently updated with news, events, and changes. By paying for licensed access, companies ensure they can legally and reliably access the latest version of articles. They don't need to worry about scraping outdated copies or violating terms of service.

For model builders, this raises an interesting question about data diversity. If multiple companies are all licensing Wikipedia through the same API, they're getting identical data. That's good for data quality, but it could lead to similar biases or gaps across models trained by different companies. But that's actually okay because companies also use proprietary data, web scrapes, and other sources. Wikipedia is one component in a diverse training diet.

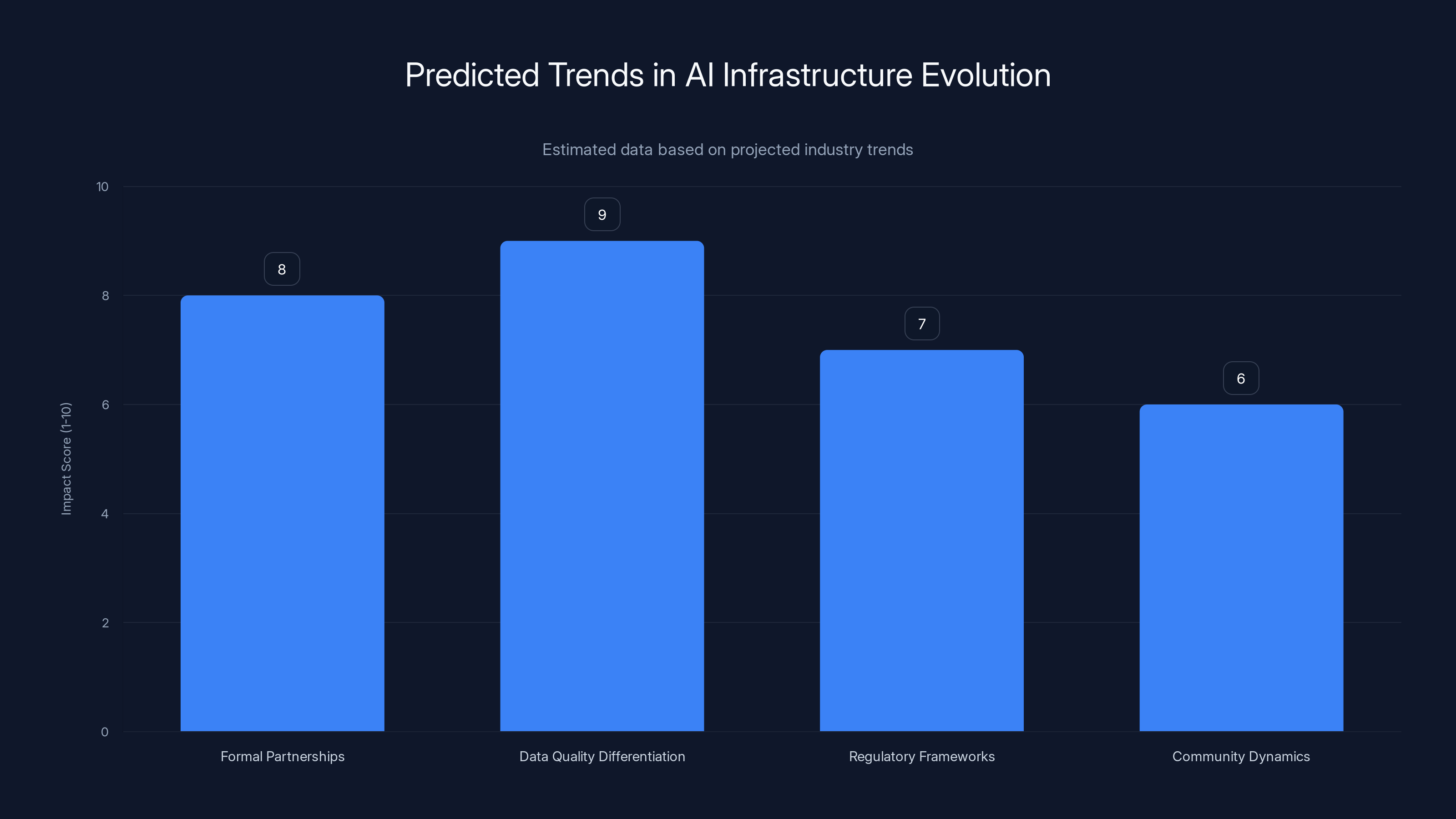

Formal partnerships and data quality differentiation are expected to have the highest impact on AI infrastructure evolution. Estimated data based on projected industry trends.

The Precedent: Other Knowledge Projects Watching Closely

One crucial thing to understand about this announcement: other organizations are watching very carefully.

Academic journals, news archives, scientific databases, and other knowledge repositories have to be wondering whether they should follow Wikimedia's lead. If the New York Times allows companies to license their archives for AI training at a premium, that changes the entire content licensing landscape. If academic publishers can monetize their journals by licensing access to AI companies, that creates new revenue streams.

This matters because it establishes a precedent that companies should pay for data. Right now, there's a norm that training data is just... out there, free to take. That norm is changing. Wikimedia is helping establish that knowledge has value and that using it at scale should involve compensation to the organizations maintaining it.

But there's a tension here. Wikimedia is a nonprofit with an open mission. Other organizations might be for-profit companies that guard their data jealously. If licensing becomes standard, some organizations might try to monetize aggressively, pricing out smaller AI companies. That could actually slow AI innovation by making training data too expensive.

The healthy outcome is probably somewhere in the middle. Wikimedia's model—reasonable pricing based on usage, with explicit licensing and terms—sets a good standard. It acknowledges data value without making access prohibitively expensive. Other organizations might follow this model or adapt it to their circumstances.

There's also a broader question about data rights and AI. As AI systems become more dependent on human-created knowledge, questions about ownership, attribution, and compensation become more urgent. Are Wikipedia editors paid for contributing data that companies later monetize? Should they be? How do you fairly compensate volunteer communities when their work becomes valuable?

These are genuinely difficult questions without clear answers. Wikimedia's approach doesn't fully solve them, but it does establish that companies have responsibility to the sources they depend on.

The Alternate Scenario: What if Wikimedia Had Done Nothing?

To fully appreciate why this partnership matters, consider the alternative.

If Wikimedia had refused to create enterprise partnerships and continued allowing companies to scrape freely, several things likely would have happened.

First, the infrastructure costs would have continued to balloon. As more companies built bigger AI systems, scraping would intensify. Wikipedia's servers would face increasing load. Wikimedia would either have to increase their infrastructure budget (which they can't afford without cutting other programs) or start blocking scrapers more aggressively. Blocking scrapers would create conflicts with companies and potentially legal disputes.

Second, Wikimedia's business model would have become increasingly fragile. If AI summaries continued reducing Wikipedia traffic, donations would decline. With declining donations and increasing infrastructure costs, a squeeze would develop. Eventually, Wikimedia would face a choice: cut staff and services, or compromise the nonprofit mission by accepting investment from companies or advertisers.

Third, there would be no contractual protections. Companies could scrape however they wanted, whenever they wanted, without any guarantee of stability or consistency. If Wikimedia changed their data structure or terms of service, companies would just adapt their scrapers. There would be no formal relationship, no SLAs, no accountability.

The partnerships solve all of these problems simultaneously. They provide revenue to cover infrastructure costs. They stabilize Wikimedia's funding by reducing donation dependence. They create formal relationships with contractual obligations. They shift from an adversarial dynamic to a cooperative one.

It's worth noting that Wikimedia did try the blocking approach for a while. They've used various technical measures to detect and block scrapers. But the economics were never sustainable. If you're a nonprofit trying to prevent determined billion-dollar companies from accessing public data, that's a losing battle. The smarter play is to acknowledge their need and monetize it.

Estimated data suggests Meta, Microsoft, and Amazon have varying levels of interest in utilizing Wikipedia data, with Meta leading due to its extensive AI integration needs.

Technical Deep Dive: How AI Systems Actually Use Wikipedia

Let's get specific about what these companies are actually doing with Wikipedia data.

Training data for language models: Companies like Meta and Google use Wikipedia to train their large language models. The process involves feeding the entire Wikipedia corpus (or a selected subset) into a machine learning pipeline that learns statistical patterns about how language works. Wikipedia's quality makes it especially valuable because the model learns patterns from well-written, fact-checked prose rather than random internet text.

The training process looks roughly like this: tokenize the text (break it into words or word-fragments), create sequences of tokens, and predict the next token in each sequence. The model learns weights that make accurate predictions. Repeat this millions or billions of times, and the model learns language patterns. Wikipedia's structured format, with clear sections and citations, helps the model learn about logical organization and source verification.

Real-time fact-checking during inference: When someone asks Chat GPT or Copilot a question, the system doesn't just generate text from scratch. It often retrieves relevant information from its training data or from external sources. Wikipedia is perfect for this because it's structured, up-to-date, and authoritative. If a model retrieves the Wikipedia article on "photosynthesis" when someone asks about how plants work, it's much more likely to generate accurate information.

This retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) approach is becoming standard for AI systems that need to be factually accurate. The companies are likely using Wikipedia data through the API to do this retrieval, ensuring they get the current version of articles and don't serve outdated information.

Embedding and vector representations: Modern AI systems convert text into numerical vectors that capture semantic meaning. These embeddings allow the system to understand that "Einstein" and "physicist" are related concepts, or that "Paris" and "France" are related. Creating good embeddings requires diverse, quality text. Wikipedia provides that diversity across millions of topics.

The process involves converting each Wikipedia article (or sections of it) into vectors, then storing those vectors in a database. When a user queries, their question is also converted to a vector, and the system finds similar vectors (similar articles) that might contain relevant information. This powers search and recommendation systems within AI products.

Structured data extraction: Beyond just the text of articles, companies are probably extracting structured information from Wikipedia. Wikipedia infoboxes, lists of people, lists of events, and other structured elements can be converted into databases. This structured knowledge helps AI systems understand relationships and hierarchies. For example, knowing that Albert Einstein is a physicist, was born in 1879, won the Nobel Prize, etc. This structured knowledge is more precise than just having the text of his Wikipedia article.

All of these use cases require scale and efficiency. An API that returns data quickly, reliably, and in the right format is essential. That's why these partnerships actually matter. Without them, companies would continue scraping, creating load that destabilizes Wikipedia's infrastructure and undermines its mission. With them, everyone wins: companies get reliable data, Wikimedia gets sustainable revenue, and users get better products because the source infrastructure is stable.

Broader Implications: The Future of Knowledge and AI

This announcement reveals something important about the future of AI and knowledge infrastructure.

For decades, we've operated under an assumption that the internet is free and data is just... there, waiting to be used. AI companies exploited that assumption ruthlessly, scraping everything and licensing nothing. But that model is breaking down because it's fundamentally unsustainable. The organizations that maintain knowledge infrastructure (Wikimedia, academic journals, news organizations, etc.) have costs. Those costs shouldn't fall on nonprofit organizations and volunteers while for-profit companies extract all the value.

The Wikimedia partnerships signal a shift toward acknowledging data as a resource that has value and should be compensated. This is healthy. It creates incentives for knowledge organizations to maintain and improve their infrastructure. It creates accountability between companies and their data sources. It makes AI training practices more transparent.

But there's a risk if taken too far. If every knowledge source starts aggressively monetizing access to AI companies, training data becomes prohibitively expensive. That could slow AI innovation, making it the exclusive domain of the richest companies. That's probably not the outcome we want.

The sustainable model is probably Wikimedia's approach: reasonable pricing, transparent terms, and recognition that the value flows both directions. Companies get crucial training data and factual grounding for their systems. Knowledge organizations get revenue that enables them to maintain and improve their infrastructure. Society benefits because knowledge infrastructure remains healthy and accessible.

There's also an interesting question about what this means for future knowledge projects. If you were building a knowledge base today (like a curated database of scientific research, or a comprehensive medical knowledge base), you'd probably build with the assumption that AI companies might want to license access. That changes how you structure data, maintain quality, and think about sustainability.

The partnerships also suggest that Wikipedia itself might evolve. With steady commercial revenue, Wikimedia could invest in features that have been long-delayed: better support for editors, improved anti-vandalism tools, better integration with academic sources, multilingual improvements, and structural changes that have been discussed but never funded.

The Sustainability Question: Will This Actually Work Long-Term?

The skeptical question to ask: will these partnerships actually solve Wikimedia's sustainability problem, or are they just a temporary revenue boost?

The optimistic view is that they create a durable revenue stream. As long as companies are training AI systems and need quality factual data, they'll license Wikipedia. The demand is fundamental and growing. More companies, more AI systems, more training runs. That suggests stable, growing revenue.

The pessimistic view is that this is a one-time adjustment. Companies pay for access once, train their models, and move on. In five years, they might not need to retrain, so the revenue stops. Or they might develop alternative data sources that reduce their Wikipedia dependence. Or AI regulations might make it illegal to train on Wikipedia without different compensation structures.

The realistic view is probably somewhere in between. The partnerships create meaningful revenue that improves Wikimedia's financial position. That's valuable. But they're not a silver bullet that eliminates the need for donations or volunteers. Wikimedia still needs passionate people contributing knowledge. It still needs donors supporting the mission. The partnerships are a supplement to that core model, not a replacement.

What's genuinely important is that Wikimedia now has options it didn't have before. If donation revenue declines, they have commercial revenue to fall back on. If they need to invest in new infrastructure or features, they have funding. That optionality is valuable.

There's also a network effect at play. If Wikipedia becomes more reliable and better-maintained because of Wikimedia's improved financial position, more people contribute. More contributions improve data quality. Better data quality makes it more valuable to AI companies, who pay more. Improved revenue enables further investment. That's a virtuous cycle.

But virtuous cycles can break. If Wikipedia's data quality declines for some reason, companies value it less, revenue drops, Wikimedia's financial situation worsens, quality continues declining. That's also a possibility.

The key is whether Wikimedia can manage the tension between the nonprofit mission (free knowledge for everyone) and the commercial reality (serving enterprise clients). If they do it well, the partnerships become a sustainable part of their model. If they mishandle it, commercial pressures might corrupt the mission.

What Comes Next: The Evolution of AI Infrastructure

This announcement is significant not just for what it is, but for what it signals about where AI infrastructure is heading.

We're seeing the emergence of a formal market for AI training data. Wikimedia is just the first mover. Others will follow. Eventually, there will be pricing benchmarks, standard contracts, and competition on terms and data quality.

We're also seeing the beginning of transparency requirements around AI training. Companies that used to scrape silently are now making formal announcements about licensing data. That's transparency progress. Users and regulators can now know where AI training data came from.

The partnerships also suggest that AI companies are maturing in their approach to data. Early AI companies treated data as a commodity. Mature ones treat it as a strategic asset requiring proper licensing, versioning, and management. That maturity is healthy.

Looking forward, we'll probably see:

More formal partnerships: Beyond Wikimedia, academic journals, news archives, scientific databases, and other knowledge sources will formalize their relationships with AI companies. Some will charge for access, others will create sharing agreements or partnerships.

Data quality as differentiation: AI companies that have access to higher-quality, more current training data will build better models. That creates incentive to pay premium prices for premium data sources. Wikimedia becomes more valuable as its data quality reputation grows.

Regulatory frameworks: Governments will probably create frameworks for how AI training data should be licensed and compensated. The EU's AI Act and similar regulations will likely include requirements for transparent data sourcing. Wikimedia's partnership model might become a template that regulators expect.

Community dynamics: Knowing that Wikipedia data is monetized might change how volunteer editors think about their contributions. Some might demand better compensation. Others might feel that commercial companies should contribute back to the nonprofit mission. Wikimedia will need to manage those dynamics carefully.

Data governance questions: As data becomes valuable, questions about ownership and control become more important. Who decides what data Wikimedia licenses? How do editors have input? How is revenue distributed? These governance questions will become increasingly important.

The announcements by Wikimedia signal that the era of free, uncompensated data extraction is ending. That's significant for AI development, for knowledge organizations, and for how we think about intellectual property and value in the AI age.

The Bigger Picture: Whose Data Is It Anyway?

Underlying all of this is a fundamental question about data ownership and value.

Wikipedia was built by volunteers who contributed their knowledge freely, with the understanding it would be freely available to everyone. The data is licensed under Creative Commons, which allows reuse (including commercial reuse) with attribution.

That licensing means companies can legally train on Wikipedia without permission. There's no explicit legal requirement that they pay. But Wikimedia is establishing a norm that just because you can do something doesn't mean you should do it without compensation.

This raises profound questions. Wikipedia editors contributed their time and knowledge. Do they deserve a share of the money Wikimedia gets from licensing that data? Should all AI training be done only on data that specifically consents to that use? Or is it reasonable for companies to use publicly available data for commercial purposes?

There's no universally agreed answer. The Creative Commons license used by Wikipedia permits commercial use. The editors presumably accepted that risk when they contributed. From a pure legal standpoint, companies using Wikipedia for training and licensing it for money haven't violated anyone's rights.

But there's an ethical dimension beyond pure legality. Companies like Meta are generating tens of billions in value using AI systems. That value rests on training data created by Wikipedia editors who receive nothing. Is that fair? Maybe it's time for new compensation models.

Wikimedia hasn't solved this directly. They're not paying editors for contributions that become valuable. But they are using some partnership revenue to improve Wikipedia, which benefits the volunteer community. That's better than nothing, even if imperfect.

Longer term, we might see different models emerge. Some knowledge projects might split revenue with their contributor communities. Others might create direct compensation systems where volunteers get paid for their contributions (though that would likely reduce volunteer participation). Others might remain purely nonprofit.

What's clear is that the era of free data extraction is ending. How we transition to a new normal—one that's fair to both knowledge contributors and AI companies—will define how AI develops over the next decade.

Lessons for Organizations Building with AI

If you're building AI systems, or using AI systems in your business, what lessons should you take from Wikimedia's partnerships?

First, understand your data dependencies: Know where your training data comes from, who maintains it, and whether you're complying with its terms. A company that ignores licensing and relies on scraped data is taking legal risk and contributing to the destabilization of the infrastructure they depend on.

Second, value quality over volume: Wikimedia data matters not because there's more of it (the internet has far more text), but because it's high-quality, fact-checked, and well-structured. When building AI systems, prioritize training on quality data rather than trying to scrape everything. Your model will be better for it.

Third, build relationships with your data sources: If your AI product depends on external data, establish formal relationships with the organizations that maintain it. Licenses and partnerships protect you legally and build goodwill. Companies that are seen as responsible partners will get better terms and more cooperation.

Fourth, be transparent about training data: When users ask where your AI system's information comes from, have a clear answer. Transparency is increasingly expected, and it's the right thing to do. If your system was trained on Wikipedia, say so. Link to the original articles when possible.

Fifth, recognize data as infrastructure: Data is not just inputs to your system; it's infrastructure that requires maintenance, curation, and investment. Supporting the organizations that maintain your data sources—through partnerships, funding, or contribution—is in your long-term interest.

These lessons apply broadly to the AI industry as it matures. Companies that treat data sources as genuine partners, not just targets for scraping, will build more sustainable and trustworthy systems.

Conclusion: A New Era for Knowledge Infrastructure

Wikimedia's announcement of enterprise partnerships with Meta, Microsoft, Amazon, Google, and others marks a genuine inflection point. For the first time, the world's largest AI companies are formally acknowledging their dependence on human-curated knowledge and paying for it.

This matters for many reasons. It provides Wikimedia with revenue that ensures their long-term financial sustainability. It establishes a precedent that companies should compensate the knowledge organizations they depend on. It shifts the relationship from adversarial scraping to cooperative partnership. It makes AI training practices more transparent.

But it also reveals something uncomfortable about how AI actually works. These systems are not magic. They're built on mountains of human-created knowledge, carefully curated, edited, and fact-checked. When companies build AI systems worth billions of dollars, they're standing on the shoulders of Wikipedia editors, academic researchers, and journalists who often receive no compensation for their contributions.

The partnerships don't fully solve that problem. But they're a step in the right direction. They acknowledge value. They create incentives for knowledge infrastructure to remain healthy. They signal that the era of free, unlimited data extraction is ending.

As AI becomes more central to business and society, how we handle data licensing, attribution, and compensation will matter enormously. Wikimedia's approach—reasonable pricing, transparent terms, support for the broader knowledge ecosystem—is a good model. Other organizations are watching. This partnership might set the template for how AI development relates to knowledge infrastructure in the future.

The bigger question is whether this transition happens smoothly. If companies balk at licensing costs and governments step in with regulations, the transition could be disruptive. If knowledge organizations try to maximize revenue at the expense of the broader ecosystem, that could slow innovation. If AI companies continue fighting to avoid paying, the conflict could escalate.

The best outcome is what Wikimedia is modeling: recognition that knowledge has value, that maintaining knowledge infrastructure costs money, and that companies benefiting from that work should contribute to its sustainability. That's not charity. That's basic economic fairness.

For Wikipedia specifically, this moment is important. Twenty-five years in, facing existential threats from AI competition and declining traffic, the organization found a way to secure its future. Not by abandoning their mission, but by monetizing the value they create while keeping knowledge free for everyone else. That's a model worth studying.

The next question is whether it scales. Can other knowledge organizations do similar deals? Will this become the new normal for how AI training relates to human knowledge? That will probably define the next chapter of AI development.

FAQ

What exactly is Wikimedia announcing with these AI partnerships?

Wikimedia announced formal enterprise partnerships with major tech companies including Meta, Microsoft, Amazon, Google, and Perplexity. These companies now have paid access to Wikimedia's high-throughput APIs, which allow them to efficiently access Wikipedia content and other Wikimedia projects (Wikivoyage, Wikibooks, Wikiquote, etc.) for training AI systems and other purposes. The companies pay based on their throughput—essentially how much data they request.

Why would Big Tech companies need to pay for Wikipedia when it's already free?

While Wikipedia content is free for human users, scraping Wikipedia at massive scale (millions of requests per day) creates significant infrastructure costs for Wikimedia. Companies pay for streamlined API access rather than scraping because it's more efficient (reducing bandwidth and server load), more reliable, legally clear, and supports the infrastructure they depend on. An API is orders of magnitude more efficient than scraping HTML pages.

How much are these companies paying, and what are the terms?

The specific pricing and contract terms haven't been publicly disclosed, as is typical for commercial agreements. However, Wikimedia indicated that pricing is based on throughput—companies that make more API requests pay more. This creates incentives for efficient usage. The company partnerships likely include terms around uptime guarantees (SLAs), support, and data versioning.

Will this partnership affect the free availability of Wikipedia for regular users?

No. The enterprise partnerships do not change Wikipedia's free access for individual users. Wikipedia will continue to be completely free and available to anyone. The partnerships only affect companies paying for high-throughput API access. Regular Wikipedia remains available to everyone at no cost.

How does this partnership help Wikimedia's financial situation?

Wikimedia relies primarily on donations for funding, creating vulnerability if Wikipedia traffic declines due to AI summaries. These partnerships provide commercial revenue—a new income stream beyond donations. This revenue helps sustain Wikipedia's infrastructure, servers, and operations even if traffic from human users declines. It also creates incentive for Wikimedia to invest in better technology and features because they now have revenue to support that investment.

Which other Wikimedia projects are included in these partnerships?

Beyond Wikipedia, the enterprise partnerships include access to Wikivoyage (travel guides), Wikibooks (educational textbooks), Wikiquote (famous quotations), Wiktionary (word definitions and etymologies), and Wikimedia Commons (freely-licensed images, audio, and video). This creates a comprehensive knowledge infrastructure for AI companies across multiple domains.

Does this mean Wikipedia data will be restricted or paywalled for AI use?

No. The partnerships don't restrict anyone from accessing Wikipedia data. They simply offer companies a more efficient, commercially-licensed pathway through APIs. Companies can still technically scrape Wikipedia if they want—the partnerships just provide a better, officially-sanctioned option that supports Wikimedia's infrastructure.

What happens if a company doesn't want to use the paid API and continues scraping?

That's technically possible but increasingly unlikely. Companies paying for API access get better terms, legal clarity, and reliability. Wikimedia can implement technical measures to discourage scraping (rate limiting, bot detection), though they won't necessarily block it entirely. The incentive structure now favors formal partnerships over informal scraping.

Could this model be applied to other knowledge sources like academic journals or news archives?

Yes, very likely. Wikimedia's partnership model establishes a precedent that knowledge organizations can monetize access to their data for AI training. Other organizations (academic publishers, news outlets, scientific databases) are probably considering similar approaches. This could create a broader market for AI training data licensing.

Does Wikimedia plan to use this revenue to pay Wikipedia editors?

There's no public announcement of direct payments to editors. However, Wikimedia can use the revenue to improve Wikipedia's infrastructure, add features editors have requested, improve anti-vandalism tools, and generally strengthen the platform. These indirect benefits support the volunteer community even if editors aren't directly compensated.

What does this mean for the future of AI model training?

This signal suggests an industry-wide shift toward formal data licensing for AI training. Rather than companies scraping data freely, we'll likely see more formal partnerships, clear licensing agreements, and compensation arrangements. This increases transparency about where training data comes from and creates accountability between companies and their data sources. It also means training data might become more expensive and strategic as organizations monetize their knowledge assets.

Key Takeaways

- Wikimedia's enterprise partnerships with Meta, Microsoft, Amazon, Google, and Perplexity represent the first major move toward formal AI data licensing

- Companies pay for high-throughput APIs instead of scraping because it's 90% more efficient, faster, legally clear, and supports Wikimedia's infrastructure sustainability

- Wikipedia's 65 million fact-checked articles generate billions in AI value, but volunteers and Wikimedia received nothing for years—partnerships acknowledge that imbalance

- Enterprise partnerships provide Wikimedia with commercial revenue beyond donations, reducing financial vulnerability from declining Wikipedia traffic due to AI summaries

- This partnership model will likely become the standard for other knowledge organizations (academic journals, news archives, scientific databases) as AI training becomes more formal

Related Articles

- Wikimedia's AI Partnerships: How Wikipedia Powers the Next Generation of AI [2025]

- Wikipedia's Existential Crisis: AI, Politics, and Dwindling Volunteers [2025]

- Wikipedia's Enterprise Access Program: How Tech Giants Pay for AI Training Data [2025]

- FTC Finalizes GM Data Sharing Ban: What It Means for Your Privacy [2025]

- OpenAI Contractors Uploading Real Work: IP Legal Risks [2025]

- Razer Forge AI Dev Workstation & Tenstorrent Accelerator [2025]

![Wikimedia's AI Partnership Strategy: Meta, Microsoft, Amazon [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/wikimedia-s-ai-partnership-strategy-meta-microsoft-amazon-20/image-1-1768496980614.jpg)