Introduction: The Data Bet That's Reshaping Autonomous Vehicles

Uber just made a quiet but massive bet on the future of autonomous vehicles, and it has almost nothing to do with building self-driving cars themselves. In early 2025, the company launched AV Labs, a new division focused on one thing: collecting real-world driving data at scale.

Here's the thing. Autonomous vehicle companies are obsessed with data. Not theoretical data. Not simulated scenarios. Real, messy, complicated driving data from actual roads in actual cities. And Uber, with its massive rideshare network spread across 600 cities, is in a unique position to provide it.

But this isn't nostalgia. Uber shut down its own autonomous vehicle development division in 2020 after a tragic incident in 2018 that killed a pedestrian in Arizona. The company learned a hard lesson: developing self-driving technology is brutally expensive, technically complex, and carries enormous liability. So instead of competing directly with companies like Waymo, Waabi, and others, Uber decided to become the infrastructure layer that feeds their AI.

The shift represents something bigger than just Uber's business strategy. It shows how the entire autonomous vehicle industry is moving. The winners won't necessarily be the companies with the best algorithms. They'll be the ones with the most data. And not just any data—the weird, edge-case stuff that happens once every thousand miles but can crash your system if you're not ready for it.

This strategy flips the traditional tech startup playbook on its head. Instead of building a proprietary product and defending market share, Uber is positioning itself as a data utility. It's betting that helping the entire ecosystem improve faster will create more value than trying to own the space alone. That's a fundamentally different mindset than what we saw during the first wave of autonomous vehicle hype.

Let's break down what AV Labs actually does, why it matters, and what it reveals about the future of self-driving technology.

TL; DR

- Uber launched AV Labs to collect real-world driving data for autonomous vehicle partners, not to build its own robotaxis

- Data has become the bottleneck in autonomous vehicle development, and solving edge cases requires massive volume

- The infrastructure approach is cheaper and less risky than building proprietary technology

- Partnerships with Waymo, Waabi, and others create network effects that benefit the entire ecosystem

- Tesla's approach demonstrates the power of distributed data collection, though Uber is starting smaller

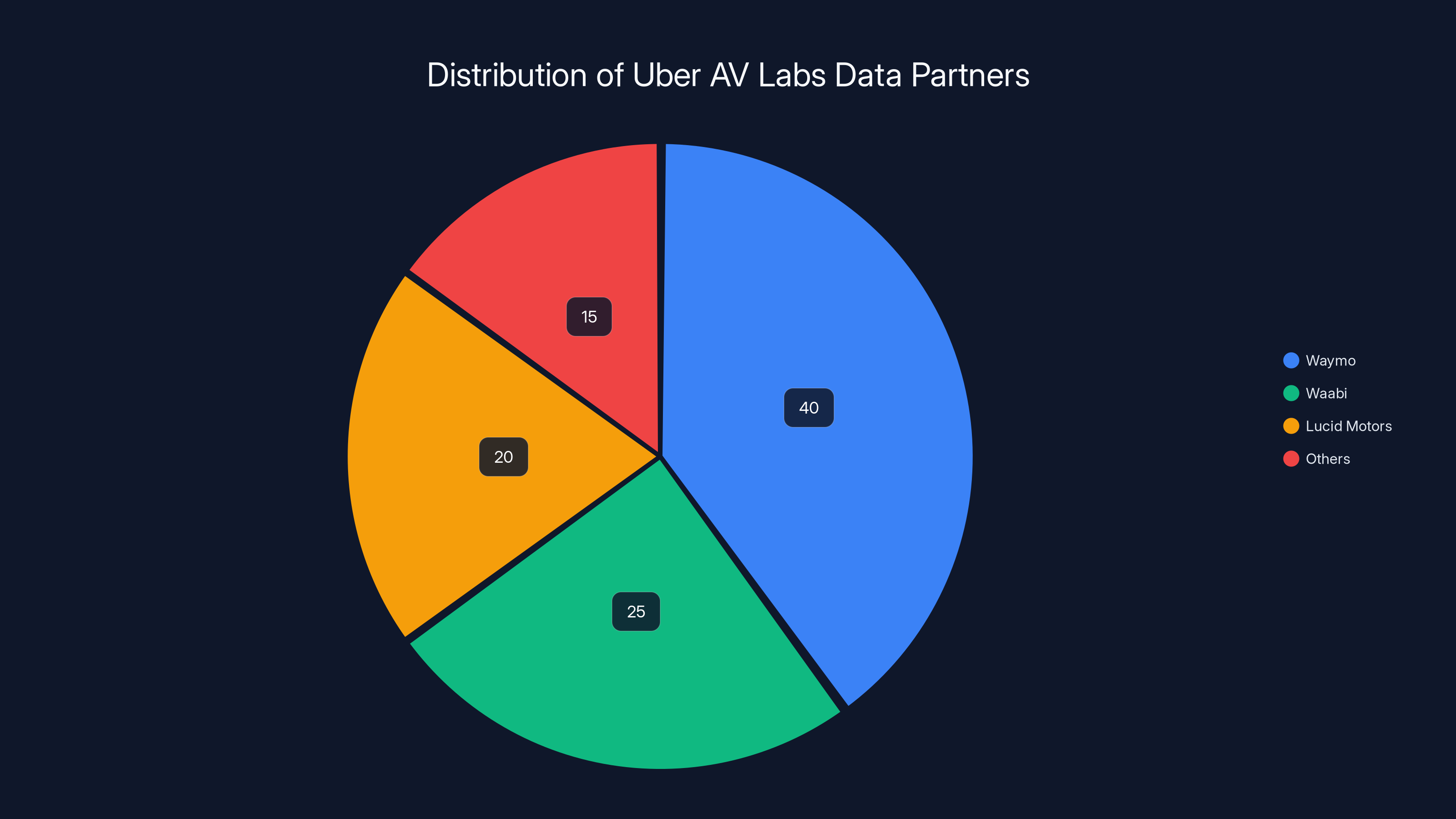

Uber AV Labs primarily distributes driving data to Waymo, Waabi, and Lucid Motors, with Waymo receiving the largest share. Estimated data.

Why Uber Abandoned Self-Driving Development (And Never Looked Back)

The story of Uber's autonomous vehicle program is a masterclass in knowing when to quit. For years, Uber invested heavily in building its own self-driving technology. Engineers worked on perception systems, decision-making algorithms, and path planning. The company had hundreds of test vehicles on the road. It was serious about becoming a player in robotaxi development.

Then came March 18, 2018. An Uber test vehicle operating in autonomous mode struck and killed Elaine Herzberg in Tempe, Arizona. She was pushing a bicycle across the street at night. The vehicle didn't detect her, and the safety driver wasn't paying attention. The investigation revealed that Uber's system had failed at the most fundamental level: seeing a pedestrian and reacting appropriately.

The incident changed everything. It wasn't just the tragedy itself, though that was obviously significant. It was what it revealed about the difficulty of the problem. If Uber, with all its resources and talent, couldn't solve basic pedestrian detection safely, then the company was probably years away from meaningful deployment. And those years would cost hundreds of millions of dollars, with no guarantee of success.

Meanwhile, Waymo was quietly making progress. The company had been working on autonomous vehicles since the Google days, accumulating years of real-world testing and learning. Waymo had a head start that looked unbeatable. Competing directly meant playing a game Waymo was already winning.

Uber made the rational decision. In 2020, it sold its autonomous vehicle division to Aurora in a complex deal that included cash, equity, and other considerations. Suddenly, Uber was out of the robotaxi business. The company would focus on what it does best: operating a massive transportation network.

But Uber didn't stop thinking about autonomous vehicles. Instead of building technology, it began thinking about how to leverage its core advantage: scale and distribution. That insight eventually led to AV Labs.

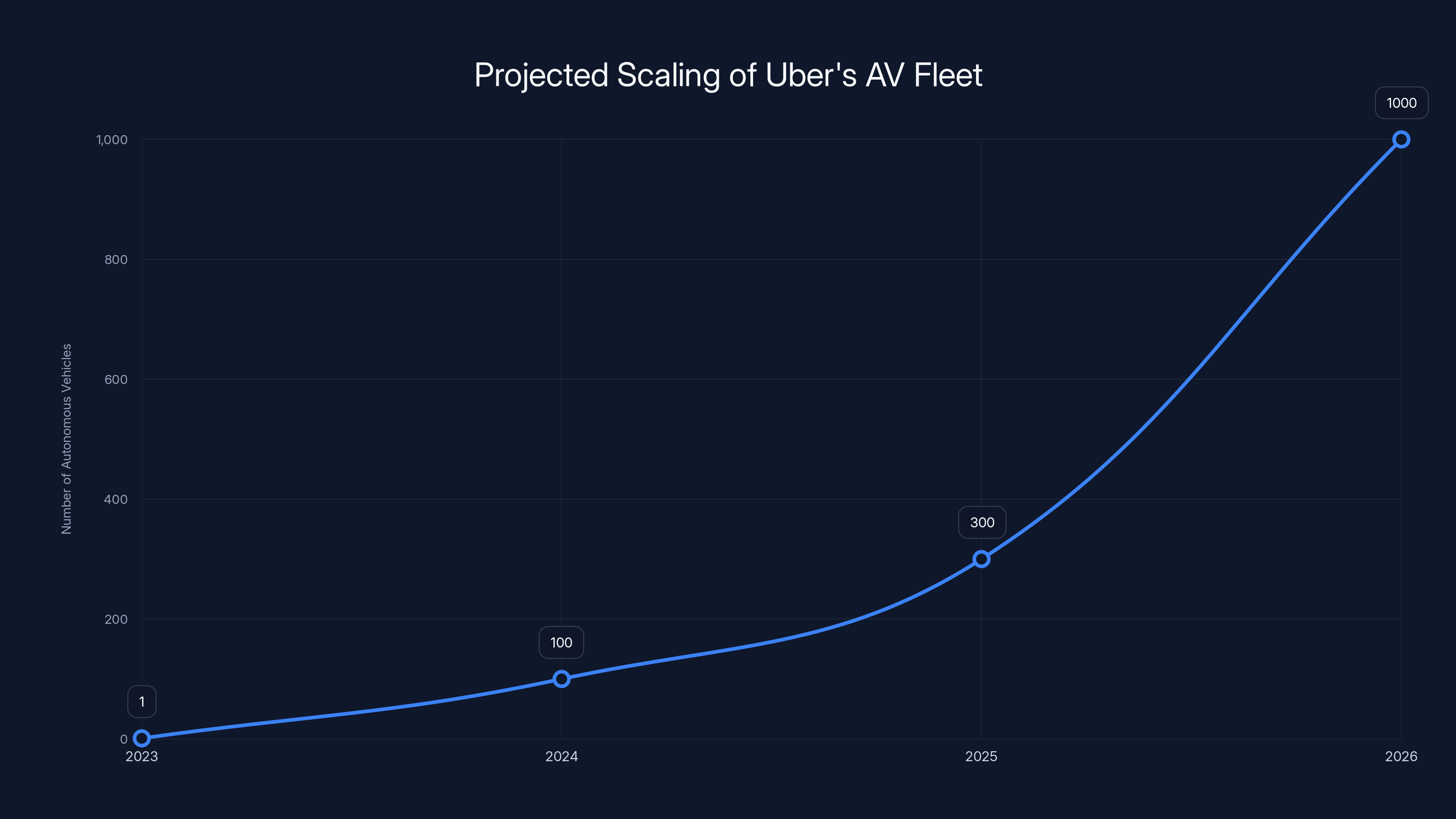

Uber's AV fleet is projected to grow from a single vehicle to hundreds within a few years, with potential for thousands as infrastructure and data collection capabilities expand. Estimated data.

The Data Bottleneck: Why Real-World Driving Information Became the Scarcest Resource

Autonomous vehicle development follows a simple but brutal equation: more miles driven equals more edge cases discovered. Edge cases are the weird scenarios that break algorithms. A school bus stopped in an unusual position. A one-eyed pedestrian. A construction worker in an unexpected uniform. A road sign obscured by graffiti. These situations happen once every thousand miles, but they're the ones that crash your system if you haven't prepared for them.

For years, the industry tried to solve this problem through simulation. Companies built digital representations of city environments, then ran millions of virtual miles to discover edge cases without the cost of actual vehicles. Simulation works, but it has a ceiling. You can only simulate what you've already thought of. The truly weird stuff? That only happens on real roads.

This is where the reinforcement learning shift becomes important. Many autonomous vehicle companies are moving away from rules-based systems where engineers manually code responses to different scenarios. Instead, they're building systems that learn from examples. Show the AI thousands of examples of pedestrian behavior, and it learns to predict pedestrian movement. Show it corner cases of pedestrians in unusual positions, and it gets better at handling those too.

But reinforcement learning has a prerequisite: data. Lots of it. Diverse data. Data from different cities, different weather conditions, different times of day, different traffic patterns. The companies that can collect the most data have a genuine advantage.

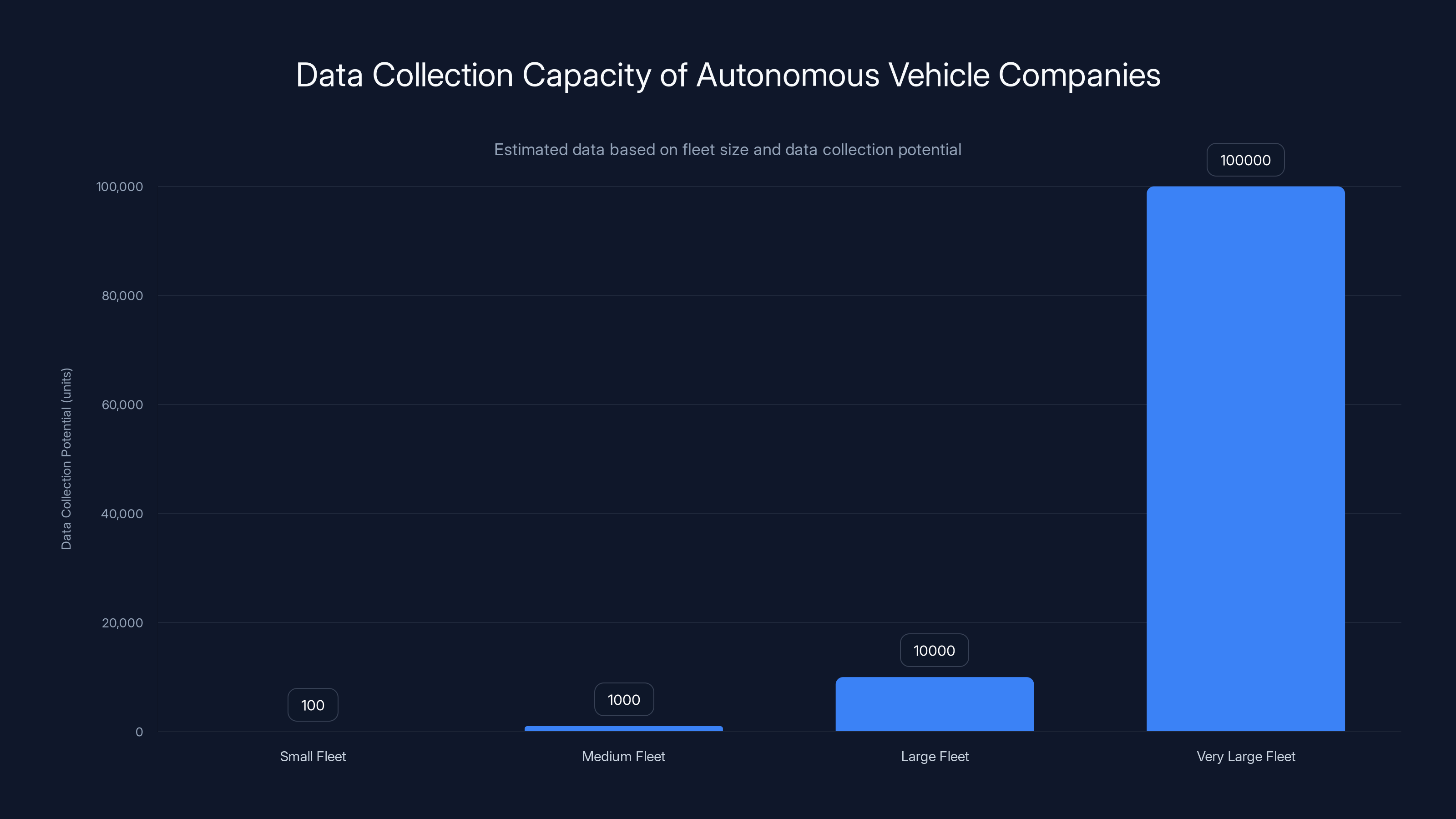

Here's the problem. Each autonomous vehicle company can only collect data from its own fleet. If you operate 100 vehicles, you get data from 100 vehicles. If you operate 1,000 vehicles, you get 10 times more data. But there's a hard ceiling. You can't operate 100,000 vehicles in testing without massive capital, regulatory approval, and operational complexity.

Uber's insight was elegant: we don't need to operate autonomous vehicles ourselves. We can operate regular vehicles equipped with sensors, collect the data, and distribute it to partners. The partners then use that data to train their autonomous systems. This approach gets around the fleet size constraint. Uber can deploy test vehicles to any of its 600 cities on demand. It can collect data wherever partners need it most.

How AV Labs Actually Works: The Mechanics of Data Collection and Distribution

So what does Uber's AV Labs actually do, day to day? The operation is surprisingly simple at first glance, though the underlying process is sophisticated.

As of early 2025, AV Labs operates with a single test vehicle: a Hyundai Ioniq 5. Yes, one car. The team was literally screwing sensors onto it by hand. Lidar units, radar arrays, multiple camera systems. This is not the polished, production-ready setup most people imagine when they think of Uber's resources. It's scrappy. It's a prototype.

The reason for starting small is deliberate. Uber's engineers want to validate their approach before scaling up. They want to understand what sensor configurations work best, how to process the data efficiently, and what format partners actually need. Once they've solved those problems, scaling to dozens or hundreds of vehicles becomes much easier.

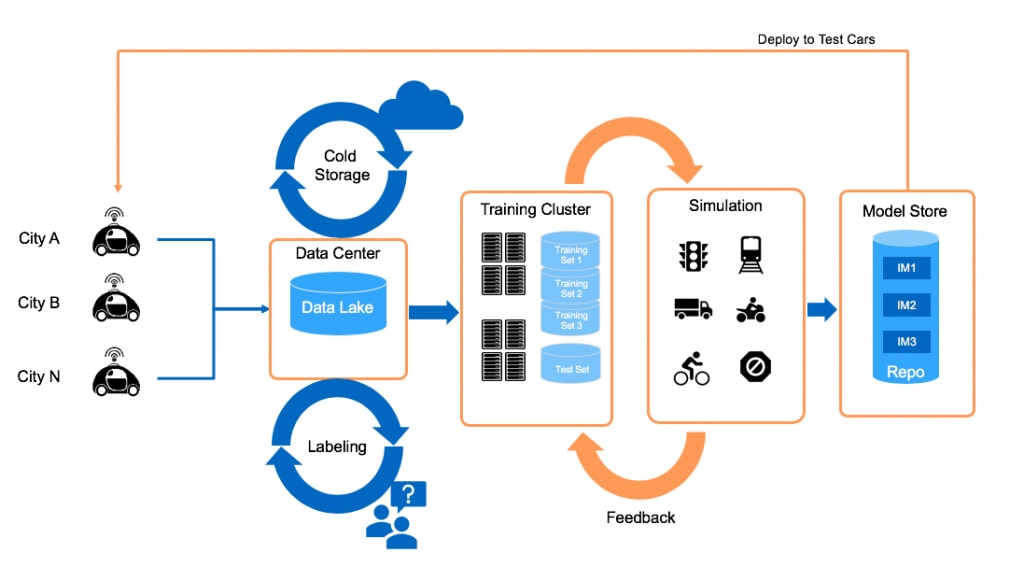

Here's how the data flows through the system. First, the vehicle drives through a city, collecting raw sensor data. This is everything: lidar point clouds, camera feeds, radar returns, GPS data, inertial measurements. Terabytes of information describing the driving environment from multiple perspectives.

Then comes the processing layer. Uber doesn't send raw sensor data to partners. That would be overwhelming and not immediately useful. Instead, the company has what they call a "semantic understanding" layer. Algorithms process the raw data and extract the relevant information. They identify vehicles, pedestrians, road markings, traffic signals, and other relevant features. They describe the driving environment in terms that autonomous vehicle algorithms can understand and learn from.

But there's another step that's equally important. Uber runs partner software in what they call "shadow mode." Here's how it works: a human safety driver is actively driving the Uber vehicle. At the same time, a partner's autonomous driving software is running on the same sensor data, but not actually controlling the vehicle. It's just making decisions in the background.

Whenever the safety driver does something different from what the autonomous software would have done, Uber flags that. Maybe the safety driver makes a gentle brake while the autonomous software would have done nothing. Maybe the safety driver turns slightly while the autonomous software would have gone straight. These discrepancies are gold. They reveal gaps in the partner's system. They show where the AI isn't making the same judgment calls a human driver would make.

Over time, patterns emerge. If the autonomous software consistently makes different decisions in certain scenarios, that's a sign it needs more training data from those scenarios. If it makes the same decisions as humans in most cases but diverges in specific edge cases, that highlights where to focus improvement efforts.

This approach mirrors what Tesla has been doing for a decade. Tesla's Autopilot and Full Self-Driving systems rely on continuous learning from millions of customer vehicles. Every time a human driver takes over, Tesla's systems learn what the human did differently. With millions of cars on the road, Tesla sees an enormous range of scenarios and corner cases.

Uber's approach lacks Tesla's scale but has a different advantage: intentionality. Uber can specifically target cities or scenarios where partners need more data. If a robotaxi company says, "We need more data for rainy conditions in Seattle," Uber can send test vehicles there specifically. Tesla's approach is passive; it learns from wherever customers happen to drive. Uber's approach is active; it can strategically collect data where it's most needed.

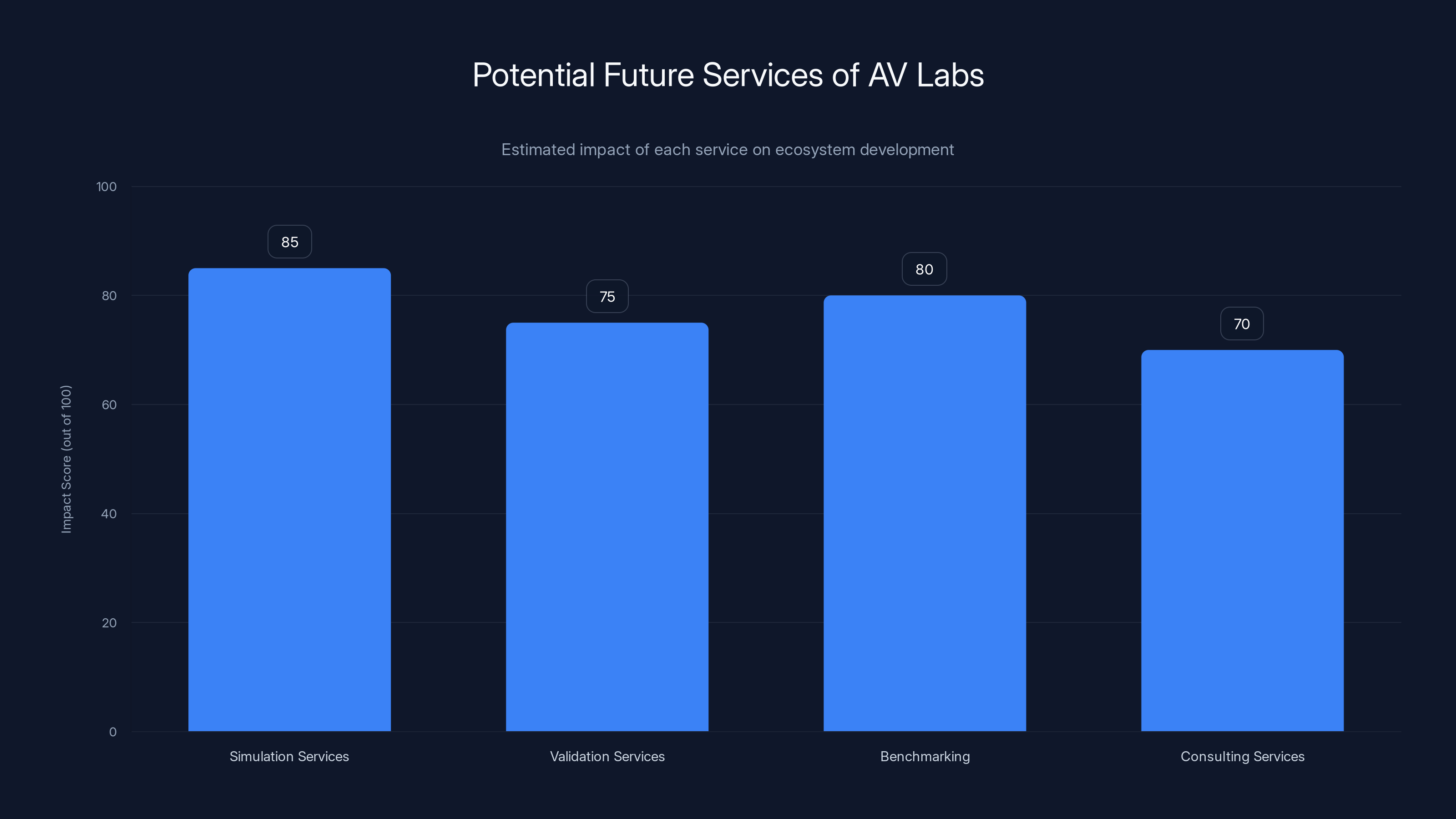

Estimated data suggests simulation services could have the highest impact on ecosystem development, followed by benchmarking and validation services.

The Partner Ecosystem: Why Everyone Wants Access to This Data

Uber has more than 20 autonomous vehicle partners. That's not an exaggeration. The company works with Waymo, Waabi, Lucid Motors, and others. All of them have expressed interest in the data that AV Labs will produce. But here's the interesting part: they're not all equally interested.

The companies most interested in Uber's data are the ones already collecting large amounts of their own data. This seems counterintuitive at first. If you're already collecting a lot of data, why would you want more from someone else? But it actually makes perfect sense.

Companies collecting large amounts of data have already figured out the hard part: integrating continuous learning into their development process. Their systems are built to ingest new data, extract patterns, and improve models iteratively. They have the infrastructure, the talent, and the processes to turn raw data into model improvements.

For these companies, additional data from a trusted source like Uber isn't just valuable; it's exactly what they need. It accelerates their development timeline. It helps them solve edge cases faster. It gives them data from cities and scenarios they may not have covered yet.

Waymo is a good example. Waymo has been operating autonomous vehicles since the Google days. The company has accumulated years of real-world driving data. Yet Waymo still has blind spots. In 2024, Waymo robotaxis were caught illegally passing stopped school buses. How does that happen? A school bus in an unusual position is an edge case that Waymo's system hadn't learned to handle properly.

Now imagine Waymo getting access to months of driving data collected in the specific cities where it operates robotaxis. If that data includes examples of school buses in various positions and conditions, Waymo's systems can be trained on those examples. The next version of Waymo's software is less likely to make the same mistake.

This is where the network effects become powerful. As more partners use Uber's data, they improve their systems faster. Improved systems perform better in the real world, which creates more demand for better data. The entire ecosystem accelerates together.

But why would Uber do this without charging partners immediately? The answer is strategic. Uber's CTO explained that the real value isn't in selling data; it's in creating an ecosystem where autonomous vehicles mature faster. When robotaxi companies improve, the robotaxi industry matures. When robotaxis become safer and more reliable, they can operate in more cities, at more times of day, handling more scenarios.

Uber wants to operate autonomous rideshare services eventually. It's already partnering with Waymo to offer robotaxis through the Uber app in certain cities. The faster Waymo and other partners improve, the faster that business can grow. Investing in AV Labs is Uber investing in its own future.

The Tesla Comparison: Scale vs. Strategy in Autonomous Vehicle Data

Anyone familiar with Tesla's approach to autonomous vehicle development will recognize what Uber is doing. Tesla pioneered the continuous learning model for self-driving cars. Every Tesla vehicle with Autopilot or Full Self-Driving enabled contributes data to Tesla's training pipeline. When human drivers take over, Tesla learns what the human did differently. With millions of vehicles on the road, Tesla accumulates enormous amounts of diverse driving data every single day.

Tesla's approach has clear advantages. It's passive from the vehicle owner's perspective. Owners aren't doing anything special; the data collection just happens automatically. This means Tesla can scale to unprecedented levels without additional operational complexity. The more vehicles Tesla sells, the more data Tesla collects. The more data Tesla has, the better its autonomous driving improves. The better autonomous driving works, the more vehicles Tesla sells. It's a powerful virtuous cycle.

But Tesla's approach also has constraints. Tesla only learns from the data its customers generate. If there's a scenario that's rare in the places where Tesla owners drive, Tesla might not have much data for it. If there's a type of road condition that's uncommon in Tesla's geographic footprint, the system might not be well-trained on it. The data collection is opportunistic, not strategic.

Uber's approach inverts some of these dynamics. Uber's data collection is deliberate and strategic. If partners say they need more data from a specific city, Uber can deploy vehicles there. If a particular type of scenario keeps causing problems, Uber can specifically collect data of that type. This allows for more efficient data collection and faster improvement in areas that matter most.

But Uber's approach can't scale as far as Tesla's, at least not initially. Uber needs to operate physical vehicles, maintain them, manage drivers or develop autonomous driving capabilities for the test fleet. This requires capital and operational overhead. Tesla's data collection is almost free at scale; once the vehicle is sold, the data streams in indefinitely.

The question is which approach matters more: scale or precision? Tesla is betting on scale. Uber is betting on precision plus scale. Uber wants to get to thousands of vehicles eventually, but first it wants to solve the data collection problem efficiently. Then it can scale.

Here's where it gets interesting. Both approaches might be necessary. The autonomous vehicle industry might need companies doing mass data collection like Tesla and companies doing strategic data collection like Uber's AV Labs. Together, they create a more complete picture of driving scenarios than either could alone.

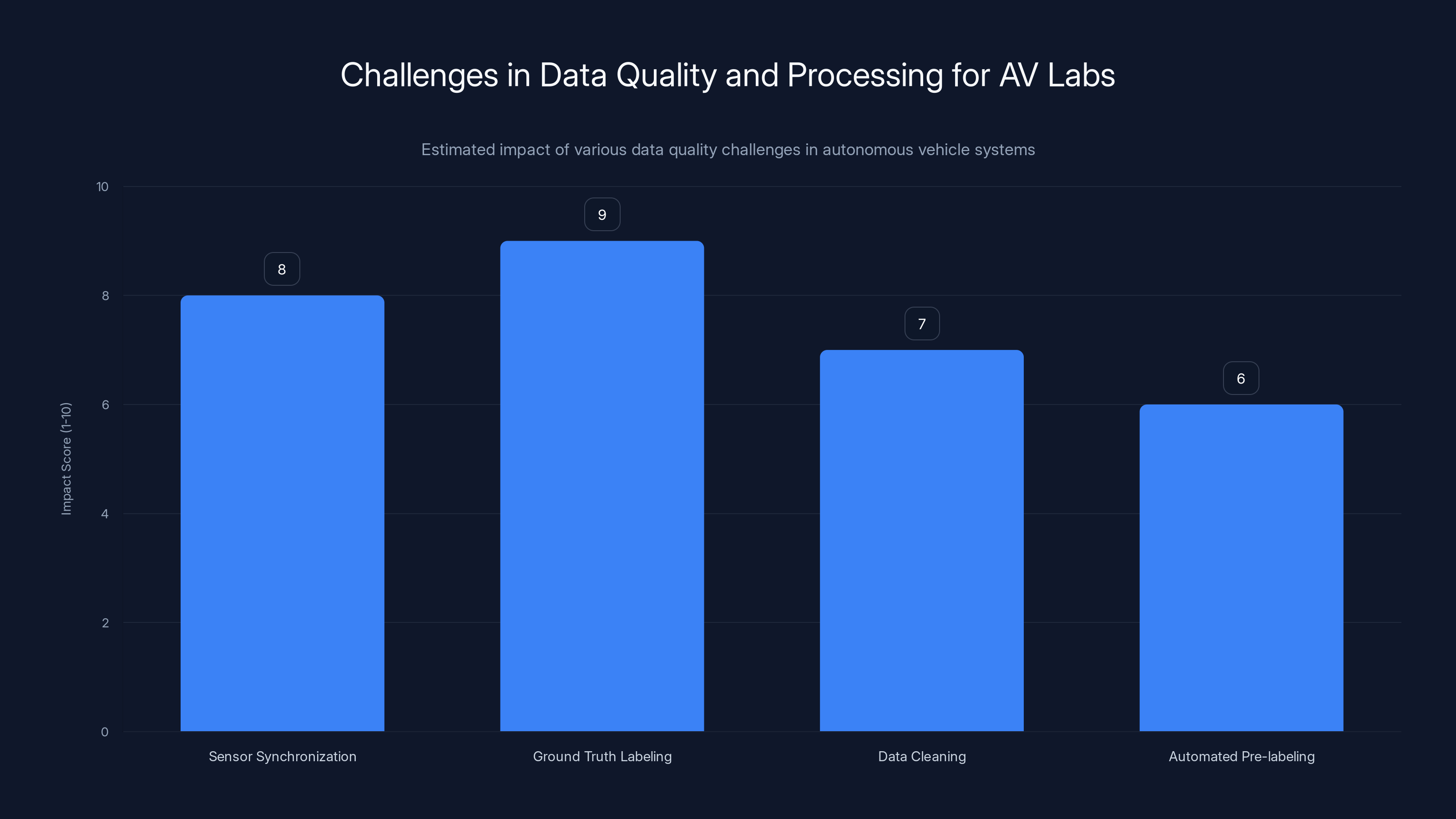

Ground truth labeling is the most challenging aspect, with a high impact score of 9, due to its complexity and importance in training accurate models. Estimated data.

Scaling AV Labs: From One Car to Hundreds

Uber isn't keeping AV Labs at one vehicle forever. The company expects to scale significantly, though the timeline is deliberate rather than rushed.

The current phase is validation. Uber's team is working through the basic problems: sensor configurations, data processing pipelines, format standards for partners. Once those fundamentals are solid, scaling becomes an engineering problem rather than a research problem. Engineering problems are easier to solve quickly.

Uber has mentioned that scaling to 100 vehicles could happen relatively soon, though "soon" in the context of robotaxi development means maybe 12-24 months. Once the team hits 100 vehicles, the data collection rate increases dramatically. You're collecting data from 100 different drivers, in 100 different contexts, often on different roads. The diversity of the dataset grows exponentially.

After 100 vehicles, the path to several hundred is clearer. Uber has hinted that growing to a few hundred people within a year is realistic. That's engineers, data scientists, operators, and support staff. Most of that growth supports scaling the data collection and processing infrastructure.

But here's the ambitious part. Uber mentioned that eventually, the entire Uber rideshare fleet could potentially collect training data. Imagine if every Uber vehicle had sensors collecting data. That's hundreds of thousands of vehicles generating driving data continuously. The scope of what you could learn from that dataset is almost incomprehensible.

That's years away, though. For now, Uber is focused on building the core infrastructure and validating the approach. The company learned from its autonomous vehicle program that patience and iteration are better than rushing to scale prematurely.

The geographical strategy is another scaling consideration. Uber operates in 600 cities. That gives AV Labs enormous flexibility in where to deploy test vehicles. If a partner says, "We need data from snowy conditions," Uber can send vehicles to Colorado or Minnesota. If another partner needs tropical climate data, Uber can deploy to Miami or Houston. The geographic diversity available to Uber is a genuine advantage that most other data collection operations can't match.

The Economics of Data: Why Giving It Away Makes Sense

One of the striking things about Uber's AV Labs strategy is that Uber isn't charging partners for the data. At least not yet. The company has explicitly said it's giving the data away, at least initially. This seems counterintuitive. If the data is valuable, shouldn't Uber charge for it?

But Uber's reasoning is sound. The company's CTO explained that the value of having partners' AV technology advance is far bigger than the money Uber could make by charging for data access. This statement reveals the actual economic logic. Uber isn't trying to monetize data directly. Uber is trying to create an ecosystem where autonomous vehicles improve faster, which benefits Uber's own robotaxi ambitions.

Think about it this way. Waymo's robotaxis are already operating through the Uber app in certain cities. When Waymo's technology improves, Waymo can deploy robotaxis in more cities and more conditions. Uber makes money from every Waymo robotaxi trip booked through the Uber platform. So Uber has a direct financial incentive to help Waymo improve. Investing in AV Labs is investing in Waymo's improvement.

The same logic applies to other partners. Most of Uber's AV partners will eventually put vehicles on the road for passenger service. The faster they can do that safely and effectively, the faster Uber can offer those services. Every month that Uber helps a partner avoid through data investment is a month closer to commercial deployment.

There's also a strategic defensibility angle. By positioning itself as a data utility that helps all partners improve, Uber makes itself indispensable to the entire ecosystem. Partners come to depend on Uber's data. Partners build their systems around being able to access Uber's data. This creates switching costs and dependencies that benefit Uber long-term.

Now, eventually Uber will likely charge for data. The company said so explicitly. But right now, the priority is getting partners hooked on the value of the data. Once partners are dependent on AV Labs data and have integrated it into their development processes, charging becomes much easier. It's a classic market development strategy: establish value first, monetize second.

The economics also work because Uber's costs aren't as high as they might seem. Operating test vehicles isn't free, but Uber already knows how to do it. The company operates a rideshare network with all the associated logistics, fleet management, and operational expertise. Adding a small fleet of test vehicles to that operation is incremental complexity, not a new business from scratch.

Companies with larger fleets can collect exponentially more data, giving them an advantage in developing autonomous vehicles. Estimated data based on fleet size.

Technical Innovation: Shadow Mode and Semantic Understanding

The real technical innovation in AV Labs isn't the vehicle operation or the basic data collection. It's the processing pipeline and the shadow mode approach. These are the pieces that transform raw sensor data into something partners can actually use.

Shadow mode deserves explanation because it's where a lot of the learning happens. Here's the concept: a human safety driver is actively controlling the test vehicle. But simultaneously, a partner's autonomous driving software is running on the same sensor data and making its own decisions. The software doesn't actually control the vehicle, but it makes all the decisions it would make if it were in control.

Every time the safety driver does something different from what the autonomous software would do, Uber flags it. These mismatches are incredibly valuable. They show where the autonomous software's judgment diverges from human judgment. Maybe the software would accelerate while the human would coast. Maybe the software would turn left while the human would go straight. Maybe the software would stop short while the human would proceed cautiously.

These discrepancies point to improvement opportunities. If the software consistently makes different decisions in stop-and-go traffic, that's a sign it needs more training data from stop-and-go scenarios. If it diverges in weather conditions, that's a sign it needs more rain or snow data. If it diverges on residential streets but not highways, that indicates a geographic or road type bias in training.

The semantic understanding layer is the other key innovation. Raw sensor data is overwhelming and hard to learn from directly. A lidar point cloud contains millions of data points. Raw camera feeds need significant processing. Radar returns need interpretation. Autonomous vehicle systems would struggle to learn efficiently from this raw data.

So Uber processes the raw sensor data into semantic representations. The system identifies objects: this is a pedestrian, this is a car, this is a bicycle, this is a traffic light. It identifies their properties: the pedestrian is standing still, the car is accelerating, the traffic light is red. It identifies relationships: the car is approaching the pedestrian's path, the pedestrian is looking in this direction.

This semantic understanding is closer to how human drivers think. We don't process pixels and point clouds; we process semantic information. We see a person, understand they're standing still, and predict they won't enter the road. We see a car accelerating toward us and predict it will reach our path. This semantic representation is much more efficient for training and much more interpretable for debugging when things go wrong.

Tesla handles this differently. Tesla's models are trained on raw pixel data and learn to extract semantic information implicitly. This approach has advantages and disadvantages. It can pick up patterns humans wouldn't explicitly code. But it's harder to understand why the model makes certain decisions, and it often requires more training data.

Uber's explicit semantic layer is more interpretable but requires more domain expertise to design correctly. The tradeoff is between interpretability and data efficiency versus end-to-end learning and implicit pattern discovery.

The Edge Case Problem: Why Volume Matters More Than You Think

This is the core insight that drove Uber to create AV Labs. In autonomous vehicle development, edge cases are the problem that doesn't scale with standard engineering. You can engineer your way out of common scenarios. You can test extensively and improve handling of situations that happen regularly. But edge cases are by definition rare.

Consider pedestrian crossing behavior. Most pedestrians follow clear patterns. They wait for walk signals, they cross at marked crossings, they make eye contact with drivers. A well-trained autonomous vehicle system handles these cases well. But pedestrians are unpredictable. Some cross against signals. Some don't look. Some move erratically. Some are disabled and move slowly. Some push strollers or wheelchairs that increase their profile size.

Waymo's experience illustrates this perfectly. The company has been operating autonomous vehicles for a decade. It has probably encountered millions of pedestrian scenarios. Yet in 2024, Waymo robotaxis were caught passing school buses illegally. How is that possible? Because the specific configuration of a school bus in a particular position with particular traffic conditions was an edge case the system hadn't learned.

School buses are different from regular vehicles. They're larger, they stop more frequently, they have specific legal protections. Autonomous vehicle systems need to understand these specifics. But if your training data doesn't include enough examples of school buses in various positions and conditions, your model won't learn to handle them correctly.

Now multiply this by every possible edge case. Every unusual road configuration. Every unexpected vehicle position. Every weather condition that creates unusual lighting. Every combination of factors that changes how a scenario plays out. The number of potential edge cases is essentially infinite.

Volume doesn't solve this problem completely, but it helps. The more miles you drive, the more you reduce the set of unseen edge cases. An edge case that would happen once every million miles becomes visible after a million miles of driving. But you won't see edge cases that happen once every ten million miles unless you drive ten million miles.

This is why data volume matters so much in autonomous vehicle development. It's why reinforcement learning requires so much data. It's why companies like Tesla with millions of vehicles on the road have such an advantage. They're constantly discovering edge cases and learning from them. Their competitors, operating thousands of vehicles, discover edge cases much more slowly.

Uber's data collection strategy is fundamentally about accelerating edge case discovery. By collecting data from multiple cities, multiple weather conditions, multiple traffic patterns, and multiple scenarios, Uber helps partners discover edge cases faster. Instead of waiting for an edge case to occur naturally in your own fleet, you get exposure to edge cases from Uber's data.

This matters because edge cases are where safety issues hide. The school bus passing wasn't just an embarrassment for Waymo; it was a safety issue. Autonomous vehicles need to handle edge cases safely, and the only way to improve handling is exposure and learning.

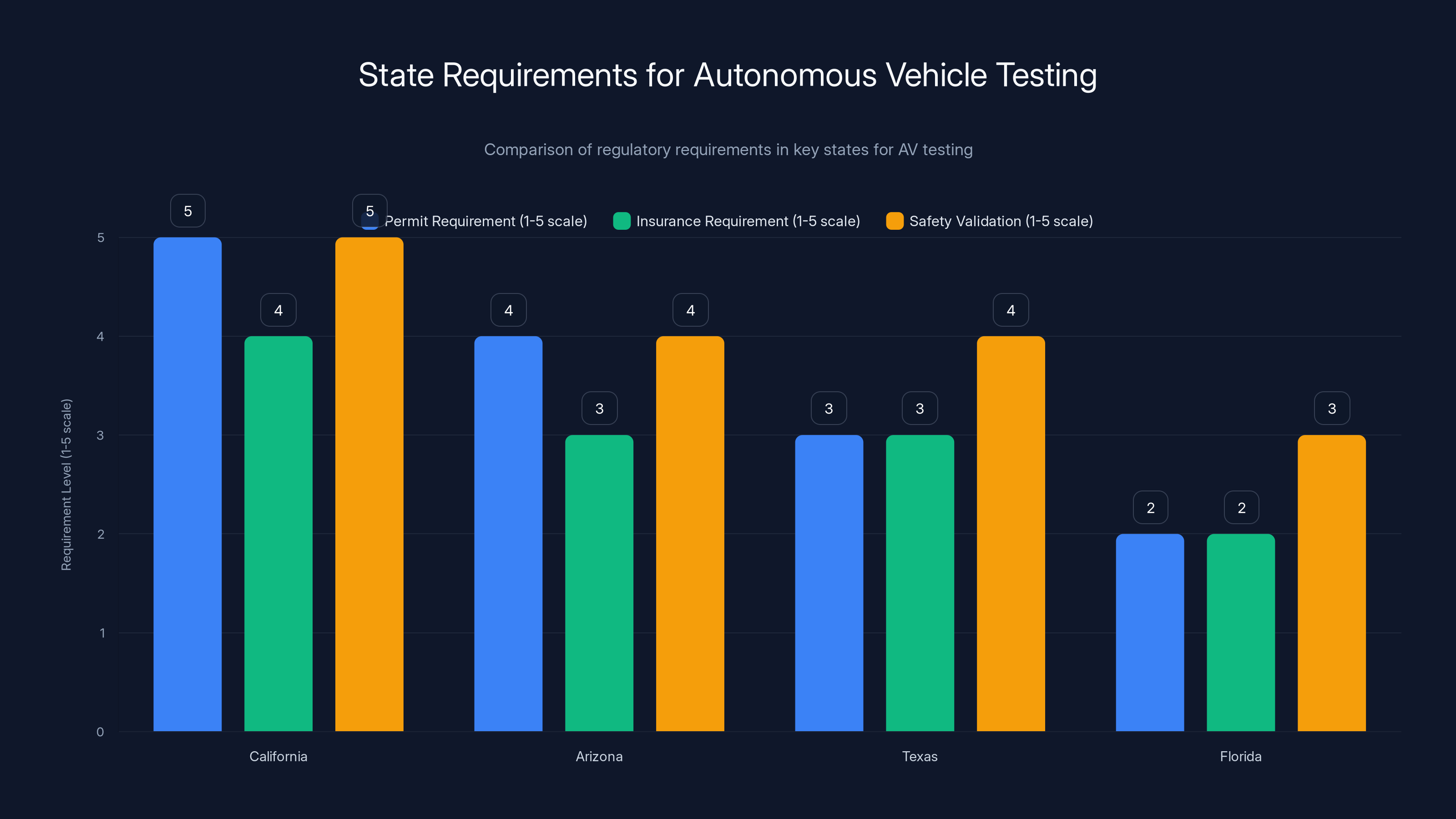

California has the most stringent requirements for AV testing, with high permit and safety validation needs. Estimated data based on regulatory trends.

Data Quality and Processing: The Unsexy But Critical Infrastructure

Most of the discussion around AV Labs focuses on scale and partnership. But the real engineering challenge is data quality and processing. This is the unglamorous work that determines whether the data is actually useful.

Raw sensor data is messy. Lidar returns bounce off rain and snow, creating phantom objects. Cameras get dirty or misaligned. GPS signals drop in urban canyons. Radar misdetects stationary objects. The data streams from different sensors need to be synchronized, calibrated, and cleaned. This is hours of unglamorous engineering work.

Then there's the problem of ground truth. When you're training a system to detect pedestrians, you need to label examples of pedestrians. When you're training path planning, you need to know what the right path decision was. Getting ground truth right is surprisingly hard. A labeler watching a video might misidentify a small object. The "right" decision in a complex scenario might be debatable. Getting enough labeled data of sufficient quality is an endless challenge.

Uber's engineering team is building systems to automate and scale this process. Computer vision models can pre-label pedestrians and vehicles, reducing manual labeling work. Clustering algorithms can identify scenarios that don't have ground truth yet, prioritizing which data needs human annotation. Statistical methods can identify low-quality or inconsistent data.

But none of this is easy. It's the kind of infrastructure work that doesn't make headlines but determines whether a data collection effort succeeds or fails. Uber's success with AV Labs depends less on the fancy partnership strategy and more on whether the team can actually deliver clean, useful data at scale.

This is where Uber's experience running a ride-hailing network becomes valuable. The company has dealt with data quality issues at massive scale. It knows how to build infrastructure for data collection, cleaning, and distribution. It has teams with expertise in handling data pipelines that serve thousands of queries per second. That operational experience is worth its weight in gold when building AV Labs.

Partnerships Beyond Waymo: The Full Partner Ecosystem

Waymo gets most of the attention when people discuss autonomous vehicle partnerships with Uber. But AV Labs is designed to work with a broader ecosystem. Waabi, Lucid Motors, and others have all expressed interest. Each partnership has different dynamics and different data needs.

Waabi is a particularly interesting partner. The company is building autonomous driving software from scratch, without the decades of Google-era development that Waymo had. Waabi is relatively young as an autonomous vehicle company, which means it's still in heavy development mode. For a company like Waabi, access to Uber's data could be transformative. Instead of spending years collecting data from its own small test fleet, Waabi can accelerate development using Uber's data.

Lucid Motors is another interesting dynamic. Lucid is primarily known for luxury electric vehicles, not autonomous driving. But the company has autonomous driving ambitions. Lucid cars could eventually offer self-driving capabilities. For Lucid, partnering with Uber's data collection effort makes sense. It gives Lucid the data it needs without the expense and complexity of operating its own fleet.

This partnership diversity is actually valuable for Uber. Different partners have different needs, different strengths, different technical approaches. Some partners are more focused on city driving. Others care about highway scenarios. Some partners are optimizing for safety margins; others are optimizing for performance and speed. By serving all of them, Uber learns which data matters most and which scenarios are universal challenges.

The competition between partners is also healthy for the ecosystem. If Waymo improves faster because of Uber's data, that puts pressure on Waabi to improve. If Waabi makes a breakthrough in handling challenging scenarios, that pushes Waymo to adapt. The competition benefits all partners and ultimately benefits Uber by accelerating the maturation of autonomous vehicle technology.

Eventually, Uber likely wants to add more partners. The company mentioned 20+ partners already, but as AV Labs proves its value, that number could grow. Each new partner is another potential robotaxi service provider on the Uber platform, another revenue stream for Uber, another way Uber benefits from autonomous vehicle development.

Regulatory Considerations: Safety Compliance and Operational Requirements

Operating a fleet of autonomous test vehicles requires navigating a complex regulatory environment. The United States doesn't have a unified autonomous vehicle regulatory framework. Different states, counties, and cities have different rules. Uber needs to navigate this fragmented landscape.

Some states require autonomous vehicle companies to apply for permits before operating test vehicles. Some require specific insurance. Some require safety validation reports. Some require periodic inspections. Uber's AV Labs needs to understand and comply with all of these requirements.

But Uber actually has an advantage here. The company has been operating in the regulatory environment for ride-sharing for years. It understands how to work with regulators, how to structure operations to meet requirements, how to document and report on safety. That experience translates directly to autonomous vehicle operations.

Safety is the critical regulatory consideration. Autonomous vehicle fleets are watched closely by regulators and the public. Any incident gets intense scrutiny. Uber learned this the hard way from the 2018 pedestrian fatality. The company is unlikely to take regulatory compliance casually.

Uber will probably need to work with specific states or cities to operate its AV Labs fleet. The company will likely focus on geographies where it already has strong regulatory relationships and where the regulatory environment is favorable to autonomous vehicle testing. California, Arizona, and Texas are likely candidates. These states have experience with autonomous vehicle testing and relatively developed frameworks for managing it.

As AV Labs expands to new cities, Uber will need to work through the regulatory process in each jurisdiction. This adds time and complexity, but it's not a major blocker. Waymo, Tesla, and other companies have shown that navigating this process is manageable, just not instantaneous.

The Long Game: Robotaxi Operations and Future Revenue

Uber's endgame with AV Labs isn't primarily about selling data. It's about owning a piece of the robotaxi economy. Uber already operates Uber Eats with both human and autonomous delivery. The company is already working with Waymo to offer robotaxis through the Uber app. This is just the beginning.

The strategy is clear: help the robotaxi ecosystem mature faster, then capture a portion of the value through the Uber platform. Uber takes a cut of every ride booked through its app, whether it's a human driver, a Waymo vehicle, or eventually a Lucid vehicle or Waabi vehicle. The bigger and more mature the robotaxi ecosystem, the more valuable the Uber platform becomes.

In this context, investing in AV Labs makes sense as infrastructure investment. It's similar to how Uber invested in driver incentives and logistics optimization early on. Those investments helped the ride-sharing ecosystem grow. Now those investments have compounded into enormous value.

AV Labs could follow a similar trajectory. Investing in data infrastructure now, before robotaxi services have matured, positions Uber as the central infrastructure player. Once robotaxis are widespread, Uber's platform, its data collection capabilities, and its partnerships become increasingly valuable.

This is a bet on a future where robotaxis are a significant portion of urban transportation. If robotaxis remain a niche service, AV Labs was a big investment in something that didn't matter much. If robotaxis become mainstream, AV Labs was a strategic investment that helped the entire ecosystem mature and Uber is positioned to capture significant value.

Uber's leadership clearly believes the latter scenario is coming. The company is willing to invest significant resources in AV Labs and accept no immediate revenue because leadership believes the long-term payoff is enormous.

Challenges and Uncertainties: What Could Go Wrong?

Uber's AV Labs strategy is sound, but it's not without risks and uncertainties. Several things could derail the approach or limit its effectiveness.

First, there's the fundamental question of whether data is actually the limiting factor in autonomous vehicle development. Uber's assumption is that more data equals better performance. But what if the limiting factor is something else? What if it's sensor technology, compute power, or algorithmic innovation? If partners are already sitting on more data than they know what to do with, then Uber's data isn't as valuable.

There's evidence suggesting data is indeed a limiting factor. Waymo's school bus incident suggests the company hasn't seen enough examples of school buses in certain configurations. But that's one data point. It's possible other limitations matter more.

Second, there's the question of whether partners will actually use the data effectively. Getting data is one thing. Integrating it into development pipelines, labeling it properly, training systems on it, validating improvements, and shipping improvements is another. Some partners might struggle with the technical execution even if the data is available.

Third, there's competition. Tesla is collecting vastly more data from its millions of customer vehicles. Other companies might invest in their own data collection efforts. Google could offer similar services to partners. The competitive advantage Uber has might be temporary.

Fourth, there's the regulatory risk. If regulations shift and become more restrictive around autonomous vehicle testing, operating large fleets could become more expensive or more difficult. Uber's whole strategy depends on being able to operate test vehicles efficiently. If that becomes harder, the value proposition changes.

Fifth, there's the economic risk. Operating vehicles costs money. Operating a few hundred test vehicles could get expensive. If Uber's predictions about the value of data don't pan out, the company might scale back or shut down the operation. Partners that have integrated Uber's data into their development processes would then be disrupted.

None of these are dealbreakers, but they're all real risks. Uber is making a bet. The bet might pay off spectacularly, or it might be a multi-hundred-million-dollar investment that doesn't deliver as expected.

Competitive Positioning: How AV Labs Shapes Market Dynamics

Uber's AV Labs strategy has interesting competitive implications. In a sense, Uber is democratizing access to data that would otherwise be proprietary to individual companies. This is good for partners. It's bad for companies like Tesla that are trying to maintain a data advantage.

Tesla's strategy is based on owning data. Tesla collects more data than anyone else from its customers' driving. Tesla doesn't share this data. Tesla uses it exclusively to improve Tesla's own autonomous driving. By keeping the data proprietary and inaccessible to competitors, Tesla maintains an advantage.

Uber's strategy inverts this. Uber is making data available to competitors. This levels the playing field between Waymo, Waabi, Lucid, and others. It's harder for any single competitor to maintain a data advantage when Uber is providing the same data to everyone.

From Uber's perspective, this makes sense. Uber doesn't have its own autonomous driving program to protect. Uber doesn't need to maintain a data moat. What Uber needs is for the entire ecosystem to improve, because every improvement makes robotaxis more viable and more valuable to Uber's platform.

But this strategy creates interesting dynamics. Companies with strong proprietary data advantage, like Tesla, might be disadvantaged relative to Uber's partners. Companies without resources to operate large fleets, like Waabi, are advantaged. The overall effect is to reduce heterogeneity in the industry. The leaders and laggards converge as they all have access to similar data.

Over the long term, this could intensify competition and reduce margins for autonomous vehicle service providers. If everyone has access to similar data, the differentiator becomes execution, not data. Waymo still has an advantage from its decade of experience. But that advantage is smaller than if Waymo was the only company with access to massive datasets.

Uber is implicitly betting that the benefits of ecosystem maturation outweigh the risks of reducing data-based competitive advantages for its partners. If the entire ecosystem matures faster, robotaxis become viable sooner, and Uber's platform captures value sooner. That seems like a smart bet.

Future Evolution: From Data Collection to Broader Ecosystem Services

AV Labs starts with data collection, but Uber's ambitions might expand. As the operation matures, there's potential for AV Labs to offer other services to the autonomous vehicle ecosystem.

One possibility is simulation services. Uber could use the real-world data it collects to build more accurate simulations. Partners could then run virtual miles against Uber's simulations, discovering edge cases in simulation rather than on real roads. This would accelerate development even further.

Another possibility is validation services. Uber could offer to run partners' autonomous driving software on Uber test vehicles in shadow mode to validate performance before deployment. This is essentially what AV Labs is already doing informally. Formalizing it into a service offering would create additional value.

A third possibility is benchmarking. Uber could offer to test different partners' software on the same routes with the same data, providing objective comparisons of performance. This would help partners understand where they stand relative to competitors and where they need improvement.

Uber could also eventually offer consulting services. Partners could hire AV Labs engineers to help with technical challenges, to optimize data collection, or to implement best practices from other partners' approaches.

None of this is confirmed, but it represents the potential evolution of AV Labs. Starting as a simple data provider, it could evolve into a comprehensive ecosystem services platform. Think AWS, but for autonomous vehicles.

This evolution would strengthen Uber's position even further. Not only would Uber own data infrastructure, but Uber would own validation infrastructure, simulation infrastructure, and consulting expertise. Partners would become increasingly dependent on Uber's services. This creates network effects and switching costs that benefit Uber long-term.

Conclusion: The Infrastructure Play That Could Define Autonomous Vehicle Development

Uber's AV Labs represents a fundamental shift in how the company thinks about autonomous vehicles. Rather than competing directly with companies like Waymo, Uber is positioning itself as the infrastructure provider that enables the entire ecosystem.

This is a smart strategic move for several reasons. First, it avoids the capital intensity and technical risk of developing autonomous driving technology. Uber tried that and decided it wasn't worth the cost and complexity. Second, it leverages Uber's genuine competitive advantage: a massive network of cities and the operational expertise to manage large fleets. Third, it creates aligned incentives with partners. When Waymo improves, Waymo makes more trips on the Uber platform, and Uber makes more money.

The execution risk is real. Building data infrastructure at scale is genuinely hard. Getting partners to actually use the data effectively requires technical execution from both sides. Regulatory approval and expansion to new cities could hit unexpected obstacles. Uber's assumptions about what constitutes valuable data could be wrong.

But if AV Labs succeeds, the implications are enormous. Autonomous vehicle development would accelerate. Edge cases would be discovered and solved faster. The robotaxi industry would mature on a faster timeline. Uber would be positioned at the center of this ecosystem, capturing value from every robotaxi service that operates through its platform.

The strategy also reflects how the industry has matured. Five years ago, every company thought it needed its own autonomous driving program. The industry has moved past that. Now the winners are likely to be companies like Uber that understand where the real leverage points are: infrastructure, partnerships, and ecosystem development rather than proprietary technology.

AV Labs is a bet on this future. It's a bet that data infrastructure will matter more than proprietary algorithms. It's a bet that ecosystem alignment will matter more than competitive advantage. It's a bet that Uber can execute better as an infrastructure provider than as a technology developer.

If that bet is right, AV Labs could be the most important thing Uber does for autonomous vehicles. Not by building the best robotaxis, but by building the infrastructure that helps everyone else build better robotaxis faster.

FAQ

What is Uber AV Labs?

Uber AV Labs is a new division launched by Uber to collect real-world driving data and distribute it to autonomous vehicle partners like Waymo, Waabi, and Lucid Motors. Rather than developing its own robotaxis, Uber operates test vehicles equipped with sensors to gather data that partners can use to improve their autonomous driving systems. The company doesn't currently charge for this data, positioning itself as an infrastructure provider for the robotaxi ecosystem.

How does AV Labs collect and process driving data?

AV Labs operates test vehicles equipped with multiple sensors including lidar, radar, and cameras that collect raw driving data from real roads. This raw data is processed through what Uber calls a "semantic understanding" layer that identifies objects, traffic signals, road features, and other relevant information. Partners' autonomous driving software runs in shadow mode alongside safety drivers, allowing Uber to identify discrepancies between what the autonomous software would do and what human drivers actually do.

Why did Uber stop developing its own autonomous vehicles?

Uber exited autonomous vehicle development after a 2018 incident in Arizona where an Uber test vehicle struck and killed pedestrian Elaine Herzberg. The incident revealed that even with significant resources, building safe autonomous vehicle technology was extraordinarily difficult and expensive. Recognizing this challenge and the lead that Waymo had already built, Uber sold its autonomous vehicle division to Aurora in 2020 and shifted strategy toward becoming an infrastructure provider.

How does AV Labs help Waymo and other partners improve their systems?

Waymo and other partners benefit from AV Labs in several ways. First, they gain access to large amounts of diverse driving data from cities where they operate or want to expand. Second, running their software in shadow mode on Uber vehicles helps identify gaps in their systems where the autonomous software makes different decisions than human drivers would make. Third, access to data from different weather conditions, traffic patterns, and geographic areas helps partners train systems that handle edge cases better.

Why doesn't Uber charge partners for the data if it's so valuable?

Uber's strategy is to democratize data access without immediate monetization. The company believes the value of having autonomous vehicle partners improve faster is greater than revenue from selling data. When partners' technology improves, they can offer robotaxi services through the Uber platform more widely, and Uber takes a percentage of every ride. Additionally, positioning AV Labs as a free utility creates network effects and ecosystem dependency that benefits Uber long-term when the company eventually introduces pricing.

How does Uber's approach differ from Tesla's autonomous vehicle data collection?

Tesla collects data from millions of customer vehicles driving in normal conditions, creating enormous scale. This passive data collection happens automatically and is essentially free at scale once vehicles are sold. Uber's approach is more strategic and smaller in scale initially, but allows intentional targeting of specific cities and scenarios. Tesla's data is proprietary to Tesla only. Uber shares its data with multiple partners, which accelerates the entire ecosystem but sacrifices competitive advantage.

When will AV Labs have hundreds of vehicles on the road collecting data?

Uber started with a single vehicle and plans to scale gradually and deliberately. The company has suggested it could reach 100 vehicles in the relatively near term, with expansion to a few hundred vehicles possible within a year or two. However, the timeline emphasizes validation and effectiveness over pure speed. Uber wants to ensure the data collection process works efficiently before massive scaling.

Could AV Labs eventually use Uber's entire rideshare fleet to collect autonomous vehicle training data?

Yes, this is explicitly mentioned as a future possibility. Uber's CTO has indicated that eventually the company's entire fleet of ride-hail vehicles could potentially be equipped to collect training data for autonomous vehicle partners. This would create an unprecedented data collection capability, though it requires vehicles to be equipped with sensors and the infrastructure to process the data at massive scale.

What cities or regions is AV Labs operating in first?

Uber hasn't specified exact locations yet, but the company has indicated it can deploy test vehicles to any of its 600 operating cities based on partner needs. Initial deployments will likely be in regions where Uber has strong regulatory relationships and favorable autonomous vehicle testing frameworks, such as California, Arizona, or Texas.

How will Uber eventually make money from AV Labs if it's giving data away now?

Uber plans to charge for AV Labs services eventually, but the current priority is establishing value and building dependency. Once partners have integrated Uber's data into their development processes and demonstrated improvements from using it, the company can introduce tiered pricing models, premium features, or consulting services. The approach follows a classic market development strategy of establishing value before monetization.

Key Takeaways

- Uber's AV Labs inverts traditional strategy by becoming infrastructure provider rather than autonomous vehicle competitor

- Real-world data collection has become the critical bottleneck in autonomous vehicle development, especially for discovering edge cases

- Shadow mode operation reveals gaps between autonomous software decisions and human driver behavior, accelerating improvement

- Strategic data collection beats passive collection for efficiency, though Tesla's scale advantage remains significant

- Uber partners benefit from ecosystem maturation while Uber captures value through its robotaxi platform

Related Articles

- Tesla Autopilot Death, Waymo Investigations, and the AV Reckoning [2025]

- Waymo Launches Miami Robotaxi Service: What You Need to Know [2026]

- Waymo in Miami: The Future of Autonomous Robotaxis [2025]

- Waymo's School Bus Problem: What the NTSB Investigation Reveals [2025]

- Waymo's Miami Robotaxi Launch: What It Means for Autonomous Vehicles [2025]

- NTSB Investigates Waymo Robotaxis Illegally Passing School Buses [2025]

![Uber's AV Labs: How Data Collection Shapes Autonomous Vehicles [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/uber-s-av-labs-how-data-collection-shapes-autonomous-vehicle/image-1-1769519223184.jpg)