AI Slop in Scientific Research: How OpenAI's Prism Threatens Academic Integrity

Science is drowning. Not in water, but in words. Specifically, AI-generated words that sound smart, look professional, and mean almost nothing.

In January 2026, OpenAI released Prism, a free AI-powered workspace designed to help scientists write papers faster. The tool launches at exactly the wrong moment. Research published just weeks earlier shows that AI-assisted academic papers are flooding peer review systems at alarming rates—and they're getting rejected more often because reviewers can spot the sophisticated prose masking weak science.

This isn't hypothetical anymore. This is happening now, across every scientific field. And the worst part? The tools making it easier to generate academic slop keep getting better.

Here's what you need to understand about the collision between AI capabilities and scientific integrity, why it matters to everyone (not just researchers), and what happens if we can't figure out how to slow the flood.

TL; DR

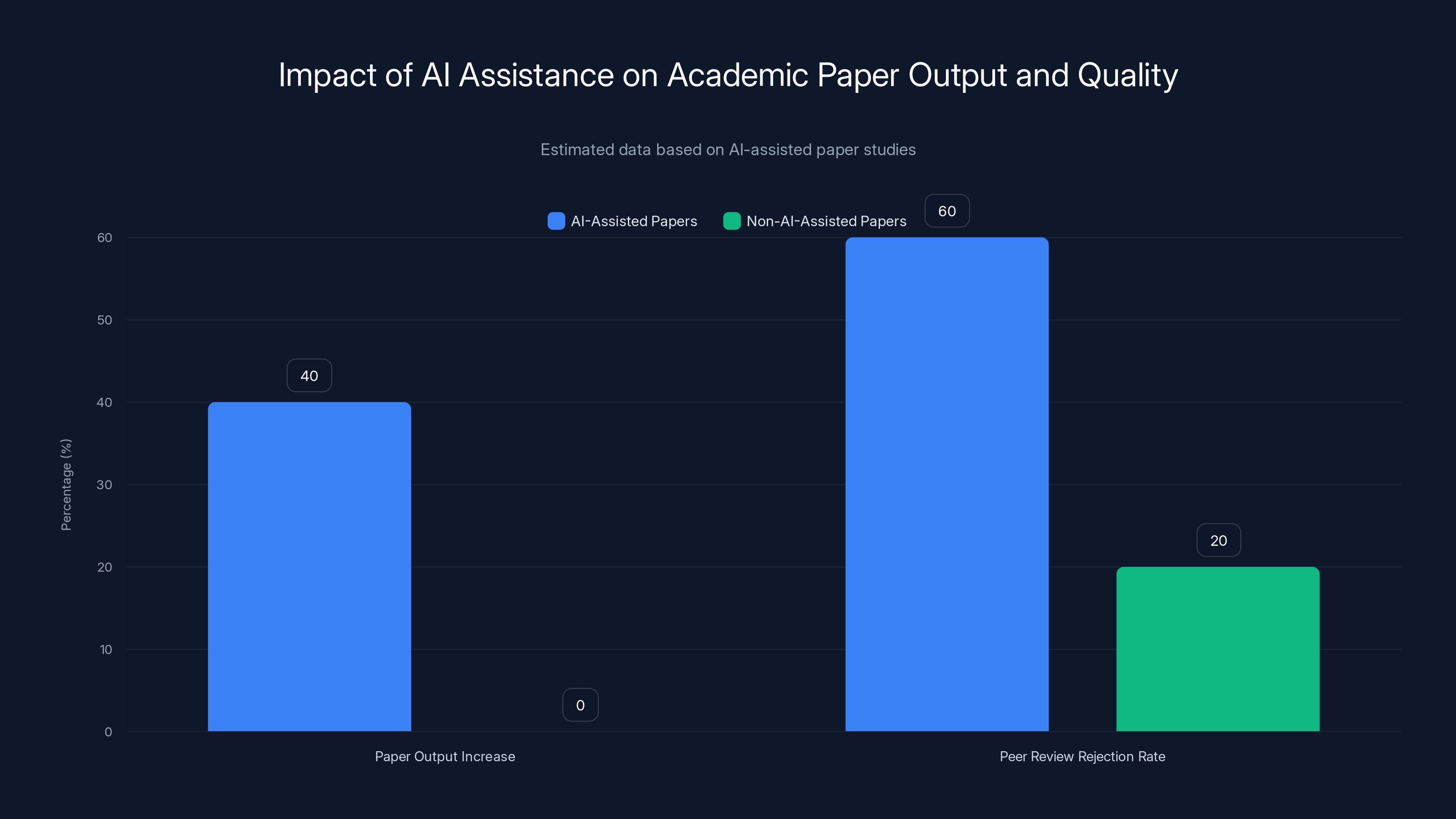

- AI-assisted papers increased output by 30-50% but perform worse in peer review and are being rejected at higher rates

- OpenAI's Prism tool launched just as journals are sounding alarm bells about "AI slop" flooding academic publishing

- The barrier to entry dropped dramatically, but the capacity to evaluate research hasn't kept pace, creating a dangerous imbalance

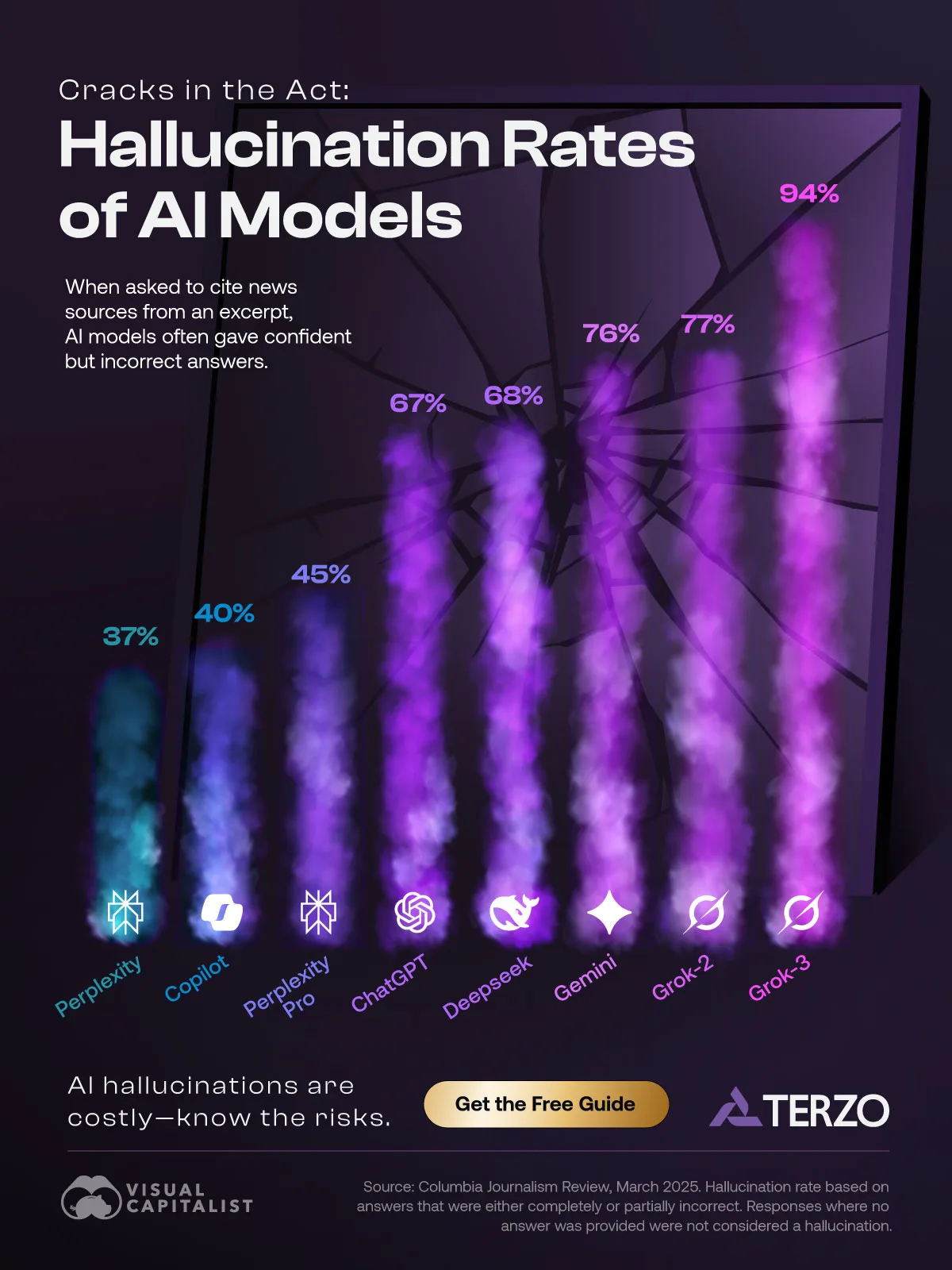

- Citation hallucination is a critical risk: AI models generate plausible-sounding sources that don't exist, unlike traditional reference software

- Science narrowing: AI-using researchers explore fewer new topics while publishing more papers, suggesting the research landscape is consolidating rather than expanding

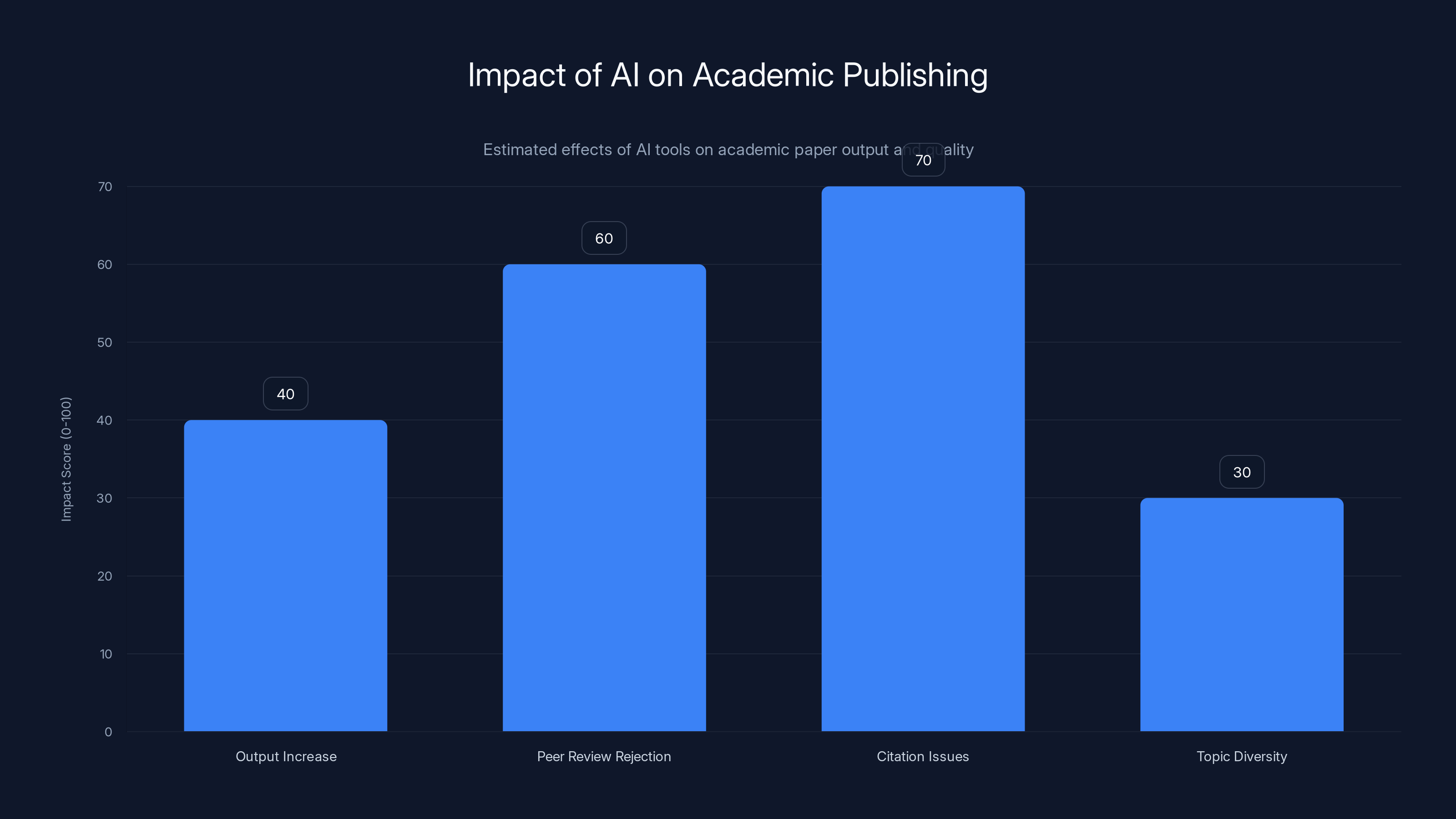

AI-assisted papers show a 40% increase in output but face a 60% rejection rate in peer review, highlighting concerns over quality. (Estimated data)

What Is Prism, Exactly?

Prism is a LaTeX-based text editor powered by OpenAI's GPT-5.2 model. If that sounds technical, don't worry—the actual function is simpler: it's meant to make writing scientific papers faster and less tedious.

The tool can automatically find relevant academic literature and incorporate it into your bibliography. It can generate diagrams from whiteboard sketches. It allows real-time collaboration between co-authors. And it's free if you have a ChatGPT account.

On the surface, this sounds reasonable. Scientists spend hours on formatting, citation management, and administrative busywork. If AI can handle that, they get more time for actual science.

But here's the problem: the tool blurs the line between administrative assistance and research generation. OpenAI's pitch suggests Prism will make scientists more productive. The data suggests it might just make it easier to produce more papers, regardless of their quality.

Kevin Weil, OpenAI's vice president for Science, told reporters that the company expects 2026 to be transformative for "AI and science." He cited 8.4 million weekly ChatGPT messages about "hard science topics" as evidence that AI is becoming core to scientific workflows.

But more usage doesn't equal better science. That's the disconnect nobody wants to discuss.

The Citation Hallucination Problem

Let's talk about the most dangerous feature of AI writing tools: citation generation.

When you use traditional reference management software like EndNote (which has existed for over 30 years), it formats citations for you. But it doesn't invent them. It pulls from databases of real papers. It doesn't make things up.

Large language models work differently. They generate plausible-sounding text based on patterns in their training data. When asked to cite sources, they can produce references that sound legitimate, that have the correct formatting, that look exactly like real papers—except they don't actually exist.

This is called "hallucination," and it's a documented problem. A researcher might cite a paper by a real author on a real topic that was never actually published. Another might cite a journal that doesn't exist. The prose flows. The bibliography looks correct. A peer reviewer scanning the paper might not catch it.

OpenAI acknowledged this risk during demonstrations of Prism. Weil said that "none of this absolves the scientist of the responsibility to verify that their references are correct." But that's not reassuring. That's telling scientists: we built a tool that might invent sources, and you're responsible for catching them.

If scientists are rushing through papers (which the data suggests they are), how many will actually verify every single citation?

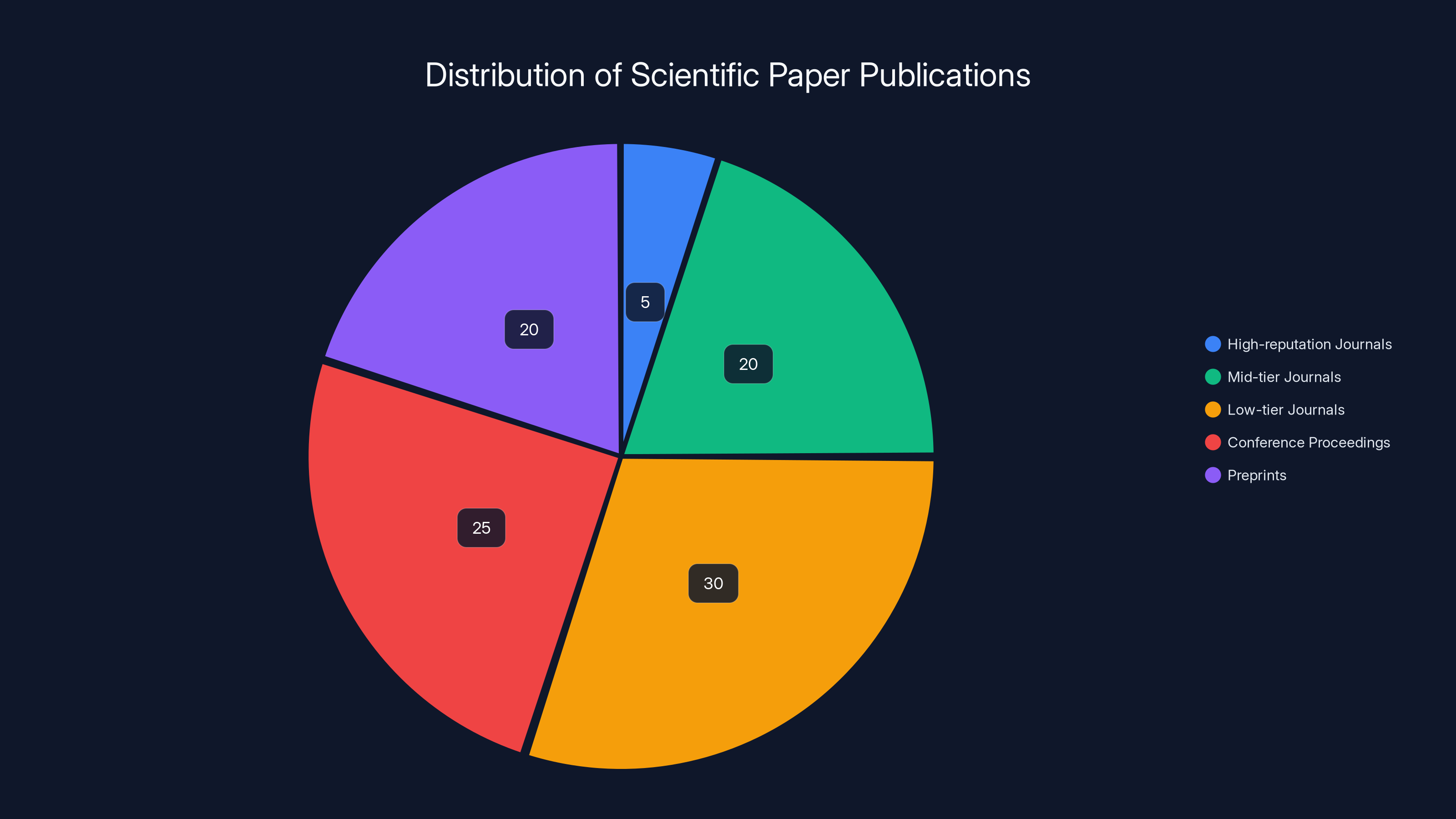

Estimated data shows that only 5% of scientific papers are published in high-reputation journals, while the majority (95%) are distributed among mid-tier, low-tier journals, conference proceedings, and preprints.

What the Data Actually Shows

Let's look at what researchers studying this phenomenon actually found.

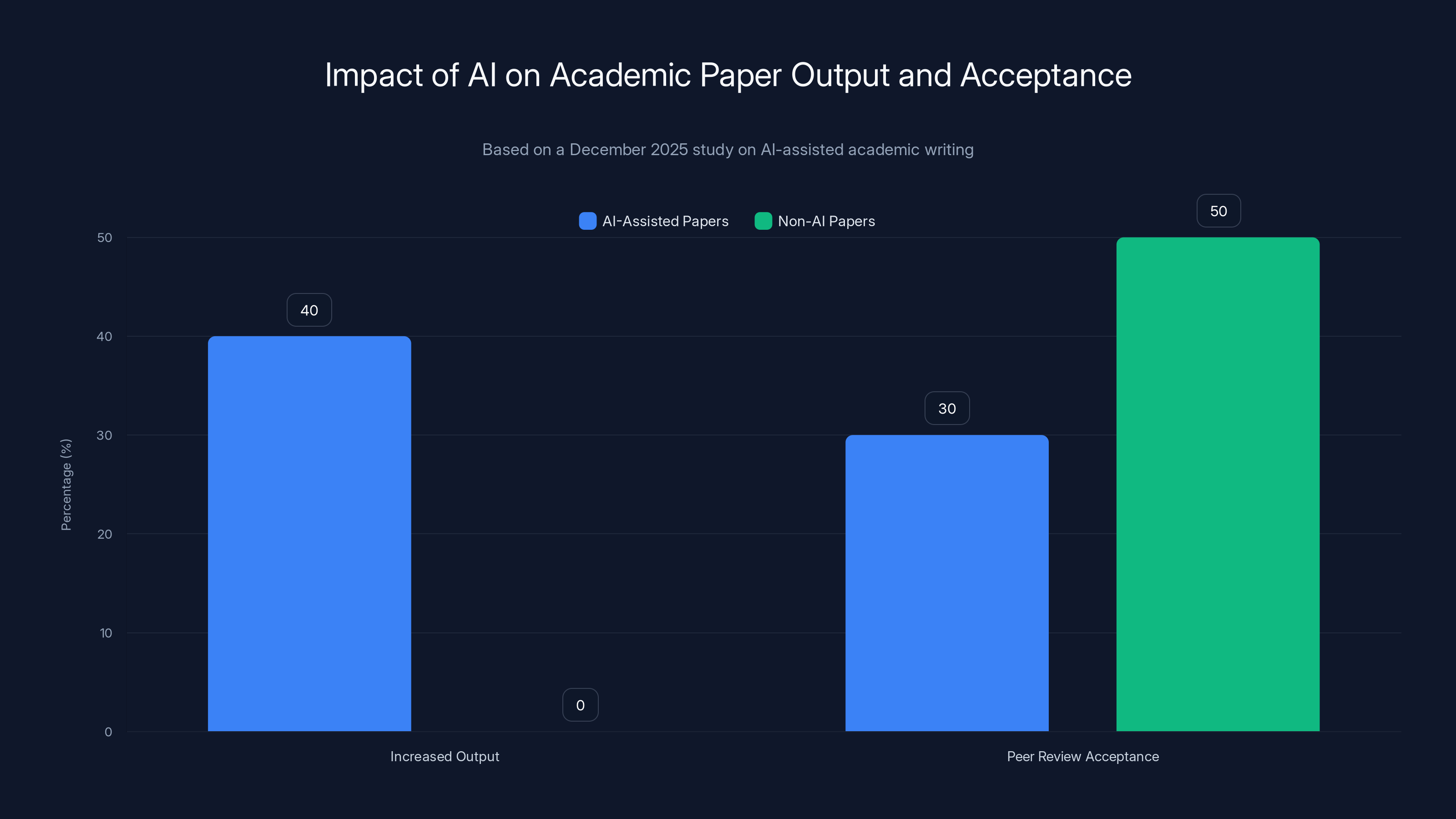

A December 2025 study published in a major scientific journal analyzed the impact of large language models on academic output. The results were clear: researchers using AI to write papers increased their output by 30 to 50 percent depending on the field.

Sounds good, right? More research. More science. More progress.

Except the same study found that papers written with AI assistance performed worse in peer review. Papers with complex language written without AI were most likely to be accepted. Papers with complex language that reviewers suspected was written by AI were less likely to be accepted.

This suggests reviewers can recognize when sophisticated prose is masking weak science. The AI made the writing sound better, but the research underneath didn't hold up.

Yian Yin, an information science professor at Cornell University and one of the study's authors, described this as "a very widespread pattern across different fields of science." He told the Cornell Chronicle: "There's a big shift in our current ecosystem that warrants a very serious look, especially for those who make decisions about what science we should support and fund."

But there's something even more troubling in a separate analysis of 41 million papers published between 1980 and 2025.

The Narrowing of Scientific Exploration

While AI-using scientists publish more papers and receive more citations, the overall scope of scientific exploration appears to be getting narrower. Researchers are exploring fewer new topics. The diversity of research directions is declining.

This is backwards from what you'd expect. More scientists with AI tools should explore more territory, try more ideas, push into more unexplored areas. Instead, the opposite is happening.

Lisa Messeri, a sociocultural anthropologist at Yale University, described this finding as setting off "loud alarm bells" for the research community. She told Science magazine: "Science is nothing but a collective endeavor. There needs to be some deep reckoning with what we do with a tool that benefits individuals but destroys science."

Let that sink in. A tool that benefits individuals (more papers, more citations for each researcher) while destroying science (narrowing the scope of collective human knowledge).

This is the paradox at the heart of the problem. Each researcher uses AI tools to become more productive individually. But collectively, the system generates more papers in fewer areas. The papers are lower quality. Journals are drowning in submissions. Peer reviewers are overwhelmed. The entire system is becoming less functional.

The History of Failed AI Science Tools

Prism isn't the first tool designed to automate scientific writing. And past attempts should make us nervous.

In 2022, Meta (then Facebook) released Galactica, a large language model specifically trained on 48 million scientific papers. The system was designed to write scientific literature, summarize research, solve math problems, and generate academic content.

It lasted three days before Meta shut it down.

Users immediately discovered that Galactica could generate completely convincing scientific nonsense. It produced papers that never existed. It invented researchers who never lived. It wrote plausible-sounding explanations for fake phenomena. The fake wiki entry about eating crushed glass became the symbolic example of what went wrong.

Meta had trained a model on real science and it learned to generate fake science that sounded exactly the same.

Two years later, in 2024, a Tokyo-based company called Sakana AI announced "The AI Scientist," an autonomous research system that would generate new scientific papers automatically. The system was designed to conduct research and publish findings without human intervention.

The research community's response was brutal. On Hacker News, a journal editor commented: "As an editor of a journal, I would likely desk-reject them. They contain very limited novel knowledge."

Other commenters called the papers "garbage." The AI Scientist was quietly shelved.

But each of these failures was treated as an isolated incident. Galactica was a Meta problem. The AI Scientist was a startup novelty. Neither prompted a comprehensive response from the scientific publishing system.

Now we have Prism. Backed by OpenAI. Free. Designed for actual scientists. Integrated into workflows. Powered by a more capable model than either of the previous failures.

AI tools have increased paper output by 30-50% but are associated with higher rejection rates and citation issues. Estimated data.

The Deluge of Submissions

Peer-reviewed journals are already struggling with the volume of submissions. The system wasn't designed for this.

Traditional peer review works because there's a bottleneck. Not every research idea becomes a paper. Not every paper gets submitted to journals. A subset gets reviewed by experts. Most get rejected. The survivors are published.

This creates a filtering mechanism. It's imperfect, but it prevents the system from drowning in mediocrity.

AI writing tools remove the first bottleneck: the difficulty of writing. If writing papers is easy, more papers get written. If more papers get written, more submissions hit journal inboxes. If more papers get submitted, reviewers are overwhelmed.

A journal editor has a fixed amount of time. A peer reviewer has a fixed amount of time. If the volume of submissions triples, the review time per paper drops by two-thirds. Rushed reviews miss problems. Problems that should be caught get published.

Mandy Hill, managing director of academic publishing at Cambridge University Press, was blunt about this in late 2025. She told Retraction Watch that the publishing ecosystem is under strain and called for "radical change." She explained to the University of Cambridge publication Varsity: "Too many journal articles are being published, and this is causing huge strain. AI will exacerbate the problem."

The warning came before Prism launched. It's more urgent now.

How Journals Are Responding

Not all journals are ignoring the problem. Some are implementing guardrails. The results are mixed.

Science, one of the most prestigious journals, updated its policies in early 2026. The journal allows limited AI use for editing and gathering references, but requires disclosure for anything beyond that. AI-generated figures are prohibited entirely.

Editor-in-Chief H. Holden Thorp wrote in his first editorial of 2026 that Science is "less susceptible" to AI slop because of its size and human editorial investment. But he acknowledged: "No system, human or artificial, can catch everything."

That's the honest take. Even elite journals with rigorous review processes can't guarantee they'll catch all AI-generated nonsense.

Other journals have taken different approaches. Some require disclosure of AI use in the methodology section. Some prohibit AI in certain areas (figures, analysis, core research) while allowing it in others (writing, editing). Some are still figuring out their policies.

But here's the problem: journals can't actually detect AI use with certainty. No tool exists that reliably identifies AI-written text. If a researcher uses AI to write a paper and simply doesn't disclose it, the journal has no way to catch them (unless reviewers notice the prose style, which requires human judgment).

The Economics of Journal Rejection

Here's an overlooked angle: what happens to researchers who generate AI papers that get rejected?

The economic incentive in academia is brutal. Researchers need publications. Publications lead to grants. Grants lead to career advancement, tenure, funding for students, lab resources.

If you use AI to write 5 papers in the same time it used to take to write 1, even if only 2 of them get accepted, you still come out ahead. Four papers published per year instead of one. More citations. More grant money. More prestige.

The personal incentive is perverse. The more AI you use to generate output (even low-quality output), the better your individual career looks. But this scales across thousands of researchers and it breaks the system.

This is what Messeri meant by "a tool that benefits individuals but destroys science."

Prism's real-time collaboration feature is estimated to have the highest impact on scientific productivity, followed by literature integration. Estimated data based on feature descriptions.

Why GPT-5.2 Changes the Equation

Prism uses OpenAI's GPT-5.2 model, which is more capable than any of the failed predecessors. This matters.

Galactica was designed for scientific content but hadn't been tested in real use cases. The AI Scientist was autonomous and clearly generated garbage. But GPT-5.2 is a general-purpose model that's already integrated into millions of workflows.

It's also better at maintaining coherence across long documents. It understands context better. It can follow complex instructions. When it hallucinates citations, they're more plausible. When it writes methodology sections, they read more convincingly.

That's not a feature. That's the problem. A worse model that generates obviously bad papers might be self-limiting. Everyone would notice. But a model that's good enough to sound right while being wrong? That's how papers full of false citations get published.

The Peer Review Crisis

Peer review is already broken. AI slop is pushing it toward collapse.

A quality peer review takes hours. A reviewer needs to read the paper carefully, check the citations, verify the methodology, look for logical flaws, run mental calculations to see if the numbers add up, and compare the findings to existing literature.

Not every reviewer takes this seriously. Some skim papers. Some miss obvious problems. Some take shortcuts.

Now imagine reviewers get 20% more submissions than they used to. They have the same amount of time. The review depth drops further.

Add to this the fact that AI-written papers are harder to spot than you'd think (they're not all obviously bad), and reviews become even more superficial.

Some high-quality papers that should be published might get rejected because reviewers didn't spend time understanding them. Some low-quality AI papers might get published because reviewers didn't spot the hallucinations or weak methodology.

The filtering mechanism breaks. The system ceases to function.

What This Means for Different Fields

The impact of AI slop isn't uniform across science. Some fields are more vulnerable than others.

Computational fields (machine learning, theoretical physics, mathematics) might be more resistant. If your paper makes mathematical claims, those can be verified or falsified relatively quickly. Nonsense becomes obvious.

But fields that depend more heavily on literature review, qualitative analysis, or complex methodology (medicine, psychology, sociology, environmental science) are more vulnerable. These fields involve more judgment. More subjectivity. More opportunities for AI-generated sophistication to mask weak science.

Epidemiology might be particularly vulnerable. If an AI generates a paper suggesting a weak correlation between some food and some disease, with a sophisticated methodology section and plausible (but false) citations, it might get published. It might even get media coverage. Public policy might change based on a paper that never should have been published.

This isn't theoretical. This is how bad science pollutes public health policy.

AI-assisted papers increased academic output by 30-50%, but had a 20% lower acceptance rate in peer reviews compared to non-AI papers. Estimated data based on study insights.

The Role of Preprints

Preprint servers like arXiv have become critical infrastructure for science. Researchers post papers before formal peer review. This accelerates discovery and prevents scooping (when someone else publishes your research first).

But preprints also create a new problem. If AI makes it easy to generate papers, those papers hit preprint servers too. Now the scientific community is reading and citing AI slop before peer review even happens.

Preprints get cited. They show up in Google Scholar. They influence research directions. They might be wrong, but by the time peer review happens (if it happens), the damage is done.

Some preprint communities are implementing new policies, but the enforcement is weak and the cultural shift is slow.

The Cost to Legitimate Research

There's a hidden cost to AI slop that nobody talks about: the cost to legitimate researchers.

If you spend months designing an experiment, running it carefully, analyzing the data with appropriate statistical methods, and writing it up with proper citations, you're doing real work. Your paper probably contributes something to the field.

But it goes into a queue with 100 other submissions. Many of those submissions are AI-assisted or AI-generated. Journal editors and reviewers are overwhelmed. Your paper might get a cursory review. It might get rejected not because it's bad, but because the reviewer didn't have time to understand it.

Meanwhile, a researcher who used AI to generate 10 papers in the same timeframe might get 3 of them published through sheer volume. They spend no time on careful research. They benefit from individual productivity tools while the system suffers.

This creates a perverse incentive structure. Careful science is penalized. Rapid publication is rewarded. The entire direction of scientific effort shifts toward quantity over quality.

What the Science Community Knows But Isn't Saying

Behind closed doors, journal editors, peer reviewers, and research institutions understand what's happening. They're scared.

The scale of the problem is becoming impossible to ignore. A single journal might receive hundreds of AI-assisted submissions per month. Processing this volume with traditional peer review is unsustainable.

Some proposed solutions include:

-

AI detection tools - But none exist that work reliably. You can't prove a paper was written by AI just by looking at it.

-

Mandatory AI disclosure - Researchers declare if they used AI. But enforcement is voluntary and consequences are weak.

-

Modified peer review - Shorter, faster reviews focused on catching red flags rather than deep evaluation. But this sacrifices quality.

-

Stricter acceptance criteria - Publish fewer papers, but only those that meet higher standards. But this slows science and creates political battles over what counts as "high standards."

-

Specialized review for AI-assisted papers - Different reviewers for papers written with AI. But who has time for this?

None of these solutions are satisfying. All of them require institutions to admit the problem is severe, which means admitting the system is failing.

The Long Game: What Happens Next

If trends continue, scientific publishing will undergo a fundamental change over the next 2-3 years.

High-reputation journals (Science, Nature, JAMA, The Lancet) will implement stricter policies and maintain quality. But they publish maybe 5% of all scientific papers. The remaining 95% goes to mid-tier and low-tier journals, conference proceedings, and preprints.

Those lower-tier venues will be flooded with AI slop. Some will implement quality filters. Others will accept anything that's remotely coherent because rejection rates are already high and rejecting more papers means declining impact.

Research institutions will struggle. Universities care about publication counts. Faculty are evaluated based on how many papers they publish. Adding guardrails around AI use means fewer publications. That's a problem for researchers trying to get tenure.

Granting agencies (NIH, NSF, DARPA, etc.) will eventually require policies on AI use. But by then, millions of problematic papers will already be published and in the scientific record.

The replication crisis will worsen. When researchers try to build on published findings, they'll discover that half the citations don't exist or are misrepresented. Time will be wasted. Careers might be damaged. Trust in science erodes further.

Meanwhile, OpenAI, Anthropic, Google, and other AI companies will keep improving their models. Better prose. More coherent methodology. Even more plausible hallucinations.

How Individual Researchers Should Respond

If you're a scientist working now, you're in a difficult position.

You have colleagues using AI to write papers faster. You have editors and journals struggling with volume. You have pressure to publish. You have limited time.

Here's the reality check: using AI as a writing assistant for formatting, editing, and organizing your real work is probably fine. If you spent 3 months designing and running an experiment, using AI to help you write it up clearly is not the problem.

The problem is using AI to write the research itself. Or using it to generate papers that don't represent real work. Or relying on it to find and cite papers without verifying the citations.

The ethical move is harder than the efficient move. But science depends on researchers making the ethical choice.

Verify your citations manually. Have colleagues read your work before submission. Don't use AI to shortcut the core research. Disclose any AI use clearly, even if the journal doesn't require it.

You're building the scientific record. That matters more than your publication count.

The Role of Institutions

Universities, research labs, and funding agencies need to act. They're not.

Institutions could:

-

Adjust evaluation criteria - Stop counting papers, start evaluating impact and significance. This is hard and controversial, but it fixes the incentive problem.

-

Slow down hiring and promotion - Reduce pressure on researchers to publish constantly. This gives them time to do careful work.

-

Support peer review - Pay reviewers, give them release time from teaching, fund the infrastructure. This improves review quality.

-

Implement institutional checks - Require verification of citations and data before papers can be submitted from your institution.

-

Invest in AI detection research - Fund projects to develop better tools for identifying AI-generated content. (Though this is an arms race.)

Most institutions are doing none of these things. They're waiting to see what happens.

The Bigger Picture: AI and Knowledge

The Prism crisis is bigger than academic publishing. It's about how humans will manage knowledge in an age of AI-generated content.

Large language models are excellent at generating plausible-sounding text on almost any topic. They're excellent at mimicking the style of expert writing. They're terrible at actually knowing things, but very good at sounding like they do.

As these tools become better integrated into every field (not just science), we face a fundamental problem: how do we distinguish signal from noise when machines can generate noise that sounds exactly like signal?

Science is supposed to be the system we use to separate truth from falsehood. If that system breaks, what's left?

Prism is just the first domino. As AI tools improve and proliferate, this problem touches medicine (AI-generated medical literature), law (AI-generated case citations), policy (AI-generated research justifying regulations), and journalism (AI-generated news articles).

The scientific publishing crisis is a preview of a much larger crisis.

Can This Be Fixed?

Technical solutions alone won't work. You can't build an AI detector that works reliably because this is an arms race. Better models will generate text that's harder to detect. Detectors will improve. Models will improve further.

The solution has to be cultural and institutional.

Science needs to consciously reject the idea that more papers = better science. It needs to reward careful work over rapid publication. It needs to support peer review as essential infrastructure, not as volunteer labor.

It needs to treat AI as a tool that has specific appropriate uses (formatting, organization, editing) and specific inappropriate uses (research generation, citation generation, hypothesis generation without verification).

Most importantly, the research community needs to move slower and think deeper.

OpenAI says 2026 is the year AI transforms science. They might be right. But not in the way they mean.

FAQ

What is AI slop in scientific research?

AI slop refers to low-quality, AI-generated academic papers that sound professional but lack genuine scientific contribution. These papers often feature sophisticated prose, properly formatted citations (that may not actually exist), and plausible methodologies that don't represent real research or genuine scientific discovery. The term specifically describes content that passes initial screening but fails deeper scrutiny because the underlying science is weak or nonexistent.

How does OpenAI's Prism tool work?

Prism is a LaTeX-based text editor that integrates OpenAI's GPT-5.2 model. The tool automatically finds and incorporates relevant scientific literature, generates citations and bibliographies, creates diagrams from sketches, and enables real-time collaboration between co-authors. It's designed to automate the administrative and formatting aspects of scientific writing, allowing researchers to spend less time on tedious tasks and more time on actual research.

Why are researchers concerned about Prism?

Researchers worry that Prism will accelerate the flood of low-quality papers into peer review systems. Recent studies show that AI-assisted papers already increase output by 30-50% but perform worse in peer review. Additionally, the tool can generate plausible-sounding citations that don't actually exist (citation hallucination), putting the burden on scientists to verify every reference. The combination of easier paper generation and known risks to paper quality creates a significant integrity concern.

What do studies show about AI-assisted academic papers?

A December 2025 study found that researchers using large language models increased their paper output by 30-50% depending on the field, but these AI-assisted papers were rejected at higher rates during peer review. Reviewers could identify sophisticated prose masking weak science. A separate analysis of 41 million papers found that while AI-using scientists publish more papers and receive more citations, the overall scope of scientific exploration is narrowing—researchers are exploring fewer new topics and the diversity of research directions is declining.

What is citation hallucination and why does it matter?

Citation hallucination occurs when AI models generate plausible-sounding academic references that don't actually exist. Unlike traditional reference management software that pulls from real databases, language models can create fake papers by real authors on real topics, entirely fictional journals, or misattributed works that sound legitimate. This matters because if a researcher doesn't verify every citation (which is time-consuming), false references can be published and subsequently cited by other researchers, corrupting the scientific record.

How are journals responding to AI-generated papers?

Journal responses vary widely. Science magazine allows limited AI use for editing and reference gathering but requires disclosure for other uses and prohibits AI-generated figures entirely. Some journals mandate AI disclosure in methodology sections. Others allow AI in writing and editing but prohibit it in analysis and figure generation. However, no reliable tools exist to detect AI-written text, making enforcement difficult and relying on researchers to self-report honestly.

What happened to previous AI science tools?

Meta's Galactica (2022) was shut down after three days when users discovered it could generate convincing scientific nonsense, including fake papers and fictional researchers. Sakana AI's "AI Scientist" (2024) was criticized by journal editors and researchers for producing papers with "very limited novel knowledge" that would likely be desk-rejected. Both failures should have prompted comprehensive changes, but instead were treated as isolated incidents, leaving the system vulnerable to more capable tools like Prism.

Why does AI slop narrow the scope of scientific research?

When individual researchers use AI to increase their output, they tend to explore fewer topics more deeply rather than exploring new areas. This creates a paradox where tools that benefit individuals (more publications, higher citation counts) harm collective science by reducing research diversity. Researchers following proven paths with AI assistance publish more than those attempting to explore new frontiers, shifting resources and attention away from novel research directions.

What should researchers do about AI writing tools?

Researchers should use AI for legitimate administrative tasks (formatting, organizing, editing completed work) while avoiding using AI to generate research, methodology, or analysis. All citations must be verified manually before submission. AI use should be disclosed clearly, even if not required by the journal. Most importantly, researchers should recognize that individual productivity improvements don't justify compromising research integrity.

How will scientific publishing change because of AI slop?

High-reputation journals will likely implement stricter policies and maintain quality, while mid-tier and lower-tier venues will be flooded with AI-assisted submissions. Peer review capacity will be stretched further. Replication crisis issues will worsen as researchers discover that previously published citations don't exist or are misrepresented. Over time, institutional changes may become necessary to slow publication rates, improve review quality, and realign incentives toward careful science rather than publication volume.

The Bottom Line

OpenAI released Prism at exactly the moment when evidence of AI slop damaging science became undeniable. That timing isn't accidental—it's the inevitable result of a company optimizing for capabilities without fully reckoning with consequences.

The tool itself isn't evil. Making scientific writing easier sounds good. But when easier tools combine with existing broken incentive structures (publish more papers = career advancement), the system breaks.

The data is clear: AI-assisted papers flood peer review, perform worse, and reduce research diversity. Peer reviewers are already overwhelmed. Journals are already struggling. The scientific record is already being corrupted by papers that should never have been published.

Prism doesn't start this crisis. It accelerates it.

The question now is whether the scientific community will act decisively to preserve research integrity, or whether we'll watch the system gradually collapse under the weight of sophisticated nonsense that sounds like science but isn't.

Science moved slowly for centuries because doing real work takes time. AI can make words appear instantly. We're discovering that speed and truth aren't aligned. The community that chooses integrity over output will be the one that actually advances human knowledge. The others will just generate slop.

Key Takeaways

- AI-assisted papers increase output by 30-50% but face significantly higher peer review rejection rates because reviewers can identify weak science hidden behind sophisticated prose

- Citation hallucination—where AI invents plausible-sounding references—is a critical risk that tools like Prism cannot entirely prevent, putting burden on researchers to verify every source

- Research diversity is actually narrowing despite increased AI-assisted publication volume, suggesting tools benefit individual researchers while harming collective scientific exploration

- Previous failed AI science tools (Meta's Galactica in 2022, Sakana AI's AI Scientist in 2024) should have prompted systemic changes but didn't, leaving the system vulnerable to Prism

- The fundamental problem is perverse incentives: AI tools that increase individual productivity while reducing research quality and narrowing scientific scope at the system level

Related Articles

- AI Hallucinated Citations at NeurIPS: The Crisis Facing Top Conferences [2025]

- OpenAI Prism: AI-Powered Scientific Research Platform [2025]

- Wikipedia's AI Detection Guide Powers New Humanizer Tool for Claude [2025]

- The AI Slop Crisis in 2025: How Content Fingerprinting Can Save Authenticity [2026]

- Honda's AI Road Safety System: How Smart Vehicles Detect Infrastructure Damage [2025]

- AI Discovers 1,400 Cosmic Anomalies in Hubble Archive [2025]

![AI Slop in Scientific Research: The Prism Crisis [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/ai-slop-in-scientific-research-the-prism-crisis-2025/image-1-1769710012890.jpg)