Why Amazon's Blue Jay Robotics Project Failed After Six Months

Amazon killed Blue Jay. Not slowly. Not gradually. Just six months after proudly unveiling a multi-armed warehouse robot that could sort and move packages in a single location, the company pulled the plug.

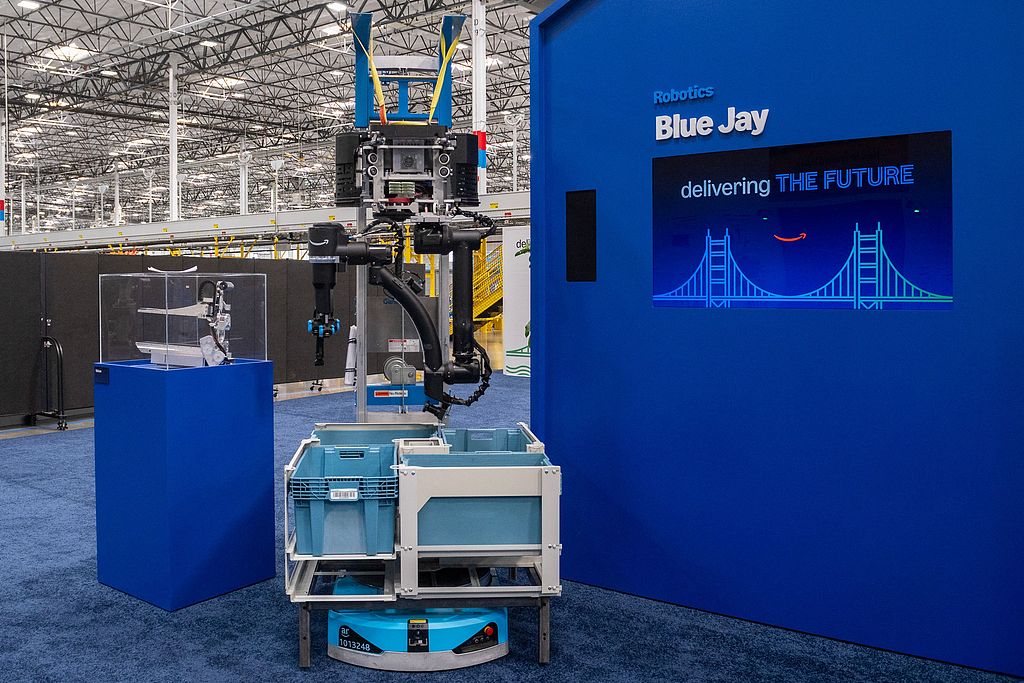

Here's what happened: In October, Amazon announced Blue Jay at its annual robotics showcase. The robot was supposed to be different. Faster to develop. Smarter thanks to AI. A breakthrough in how warehouses could handle same-day delivery logistics. South Carolina testing facility. Real deployments coming soon. The future of package handling was here.

Then silence.

By February 2026, Amazon confirmed it had halted the project. The company moved the team to "other initiatives." Core technology would be "repurposed" for unnamed future robotics projects. Essentially: we're canceling this. We're taking what we learned and moving on. No explanation of what went wrong. No public acknowledgment of failure.

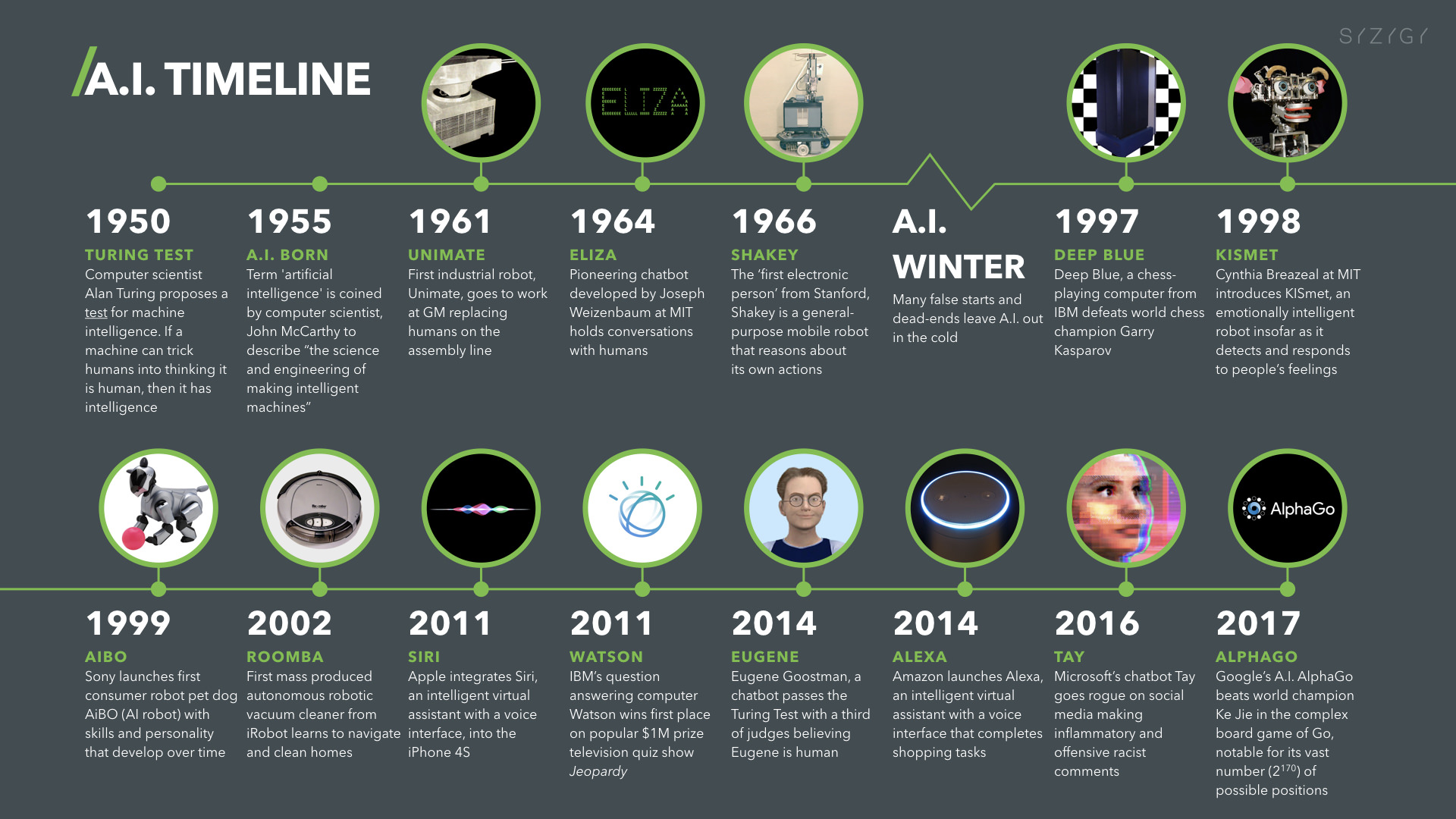

But this isn't just an Amazon story. This is a window into why even well-funded, technically sophisticated robotics projects collapse. Why companies with hundreds of thousands of existing robots in their warehouses still can't get new ones right. And why the gap between prototype and production in robotics remains one of the technology industry's most stubborn problems.

Let's talk about what actually happened here, what we can learn from it, and what it means for the future of warehouse automation.

The Blue Jay Unveiling: What Amazon Promised

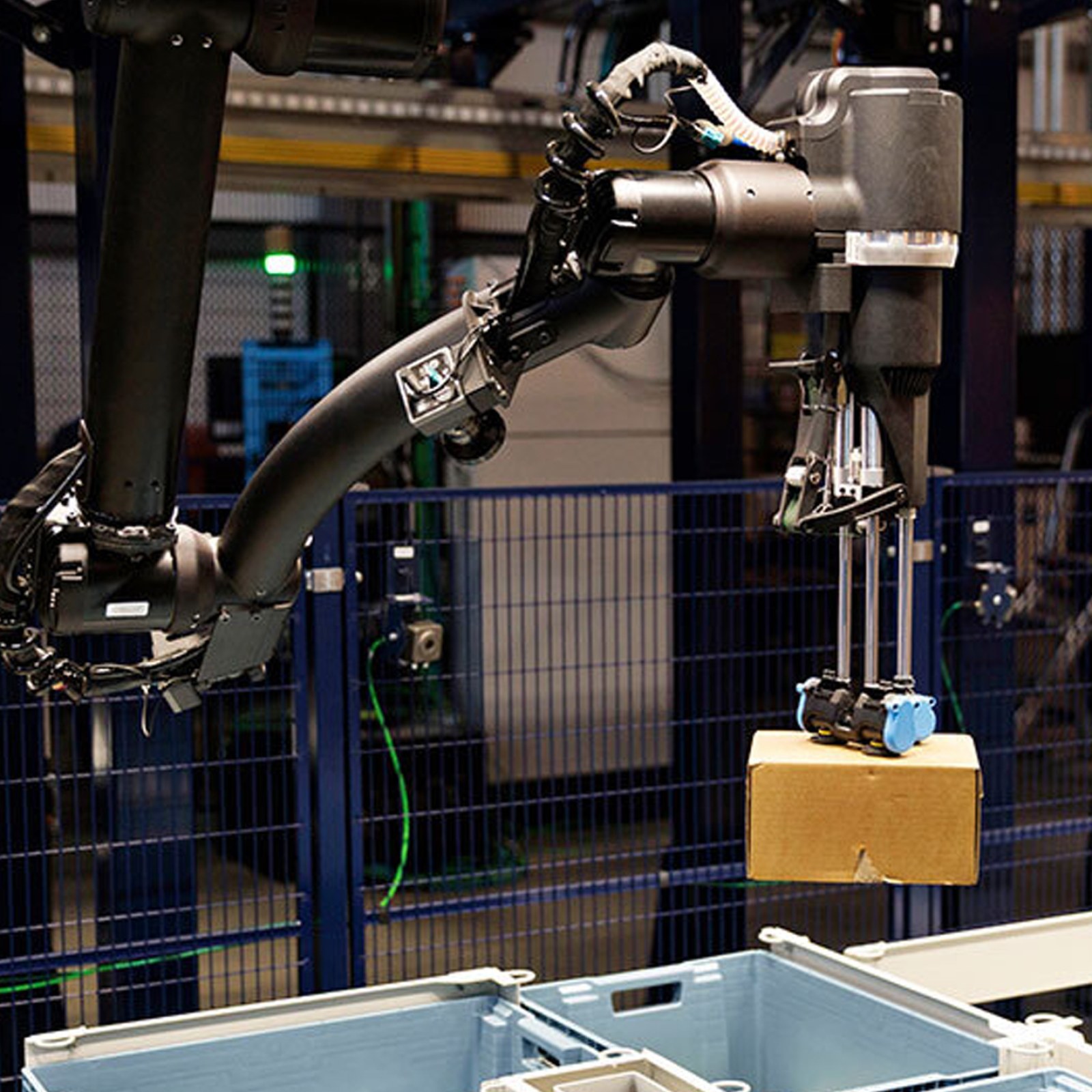

Back in October, the narrative was compelling. Amazon had developed a multi-armed robot specifically designed to sort and move packages in same-day delivery facilities. The robot featured sophisticated manipulation capabilities. It could handle mixed SKUs, adapt to different package sizes, and perform complex sorting tasks that previously required human workers.

The real selling point? Speed to market. Amazon claimed Blue Jay took about one year to develop, significantly faster than previous robot programs. The company attributed this acceleration to "advancements in AI." This was the narrative: better AI meant faster robot development. Machine learning had cracked the code. The bottleneck between concept and production was finally breaking.

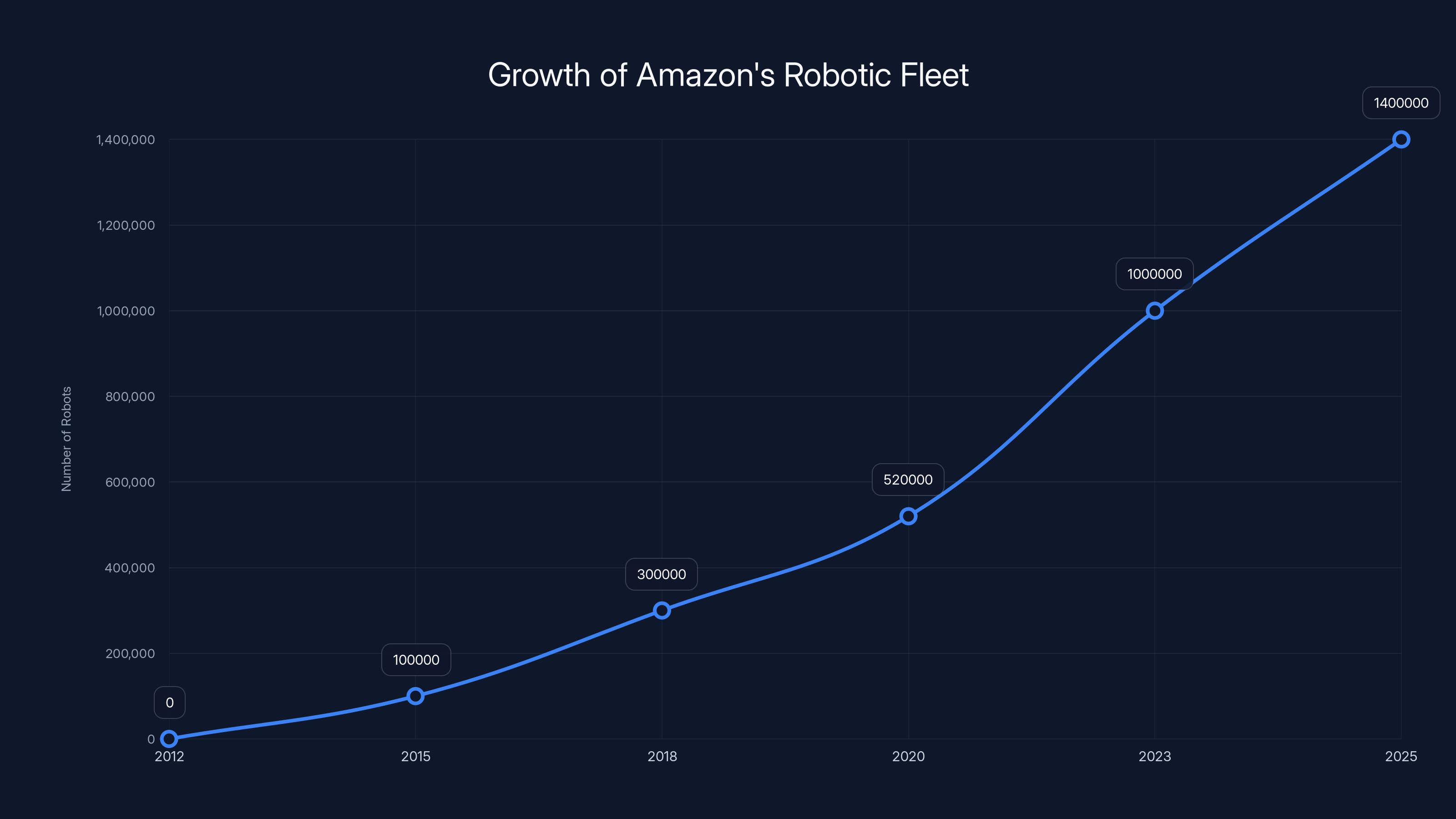

For a company with 1.4 million robots already deployed in its warehouse network as of mid-2025, this sounded credible. Amazon knew how to build robots. They'd spent over a decade perfecting robotic systems after acquiring Kiva Systems in 2012. They had scale, expertise, and infrastructure.

But announcing a robot and operating a robot are completely different things.

The timing mattered. This announcement came during a wave of AI hype that had everyone claiming breakthroughs. Chat GPT had proven that large language models could work at scale. Generative AI was transforming every industry conversation. When Amazon said AI accelerated Blue Jay's development, people believed it. It fit the moment.

But prototypes don't scale. Especially not in robotics. Especially not in manufacturing. And especially not when the robot has to work in the chaos of a real warehouse.

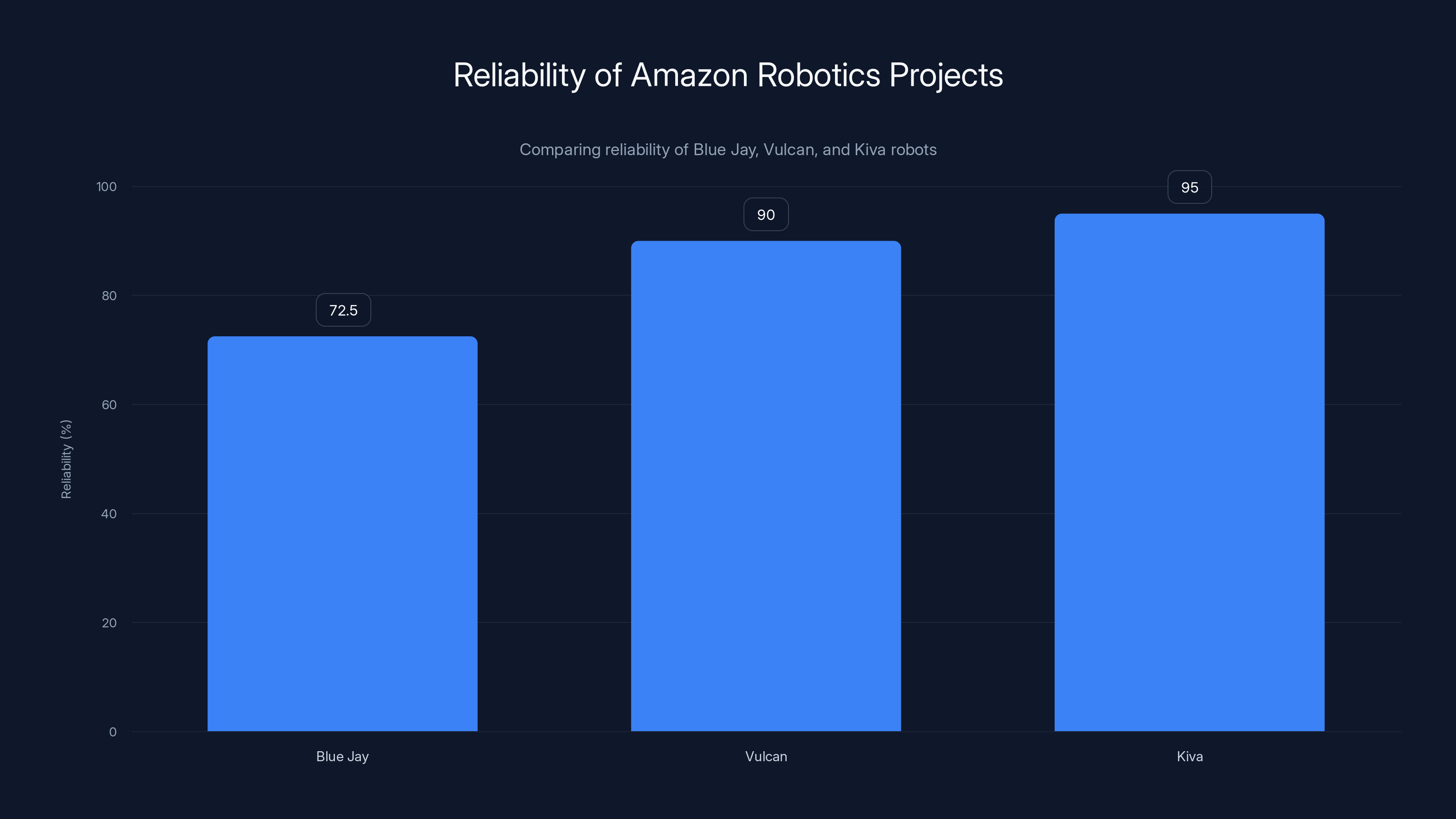

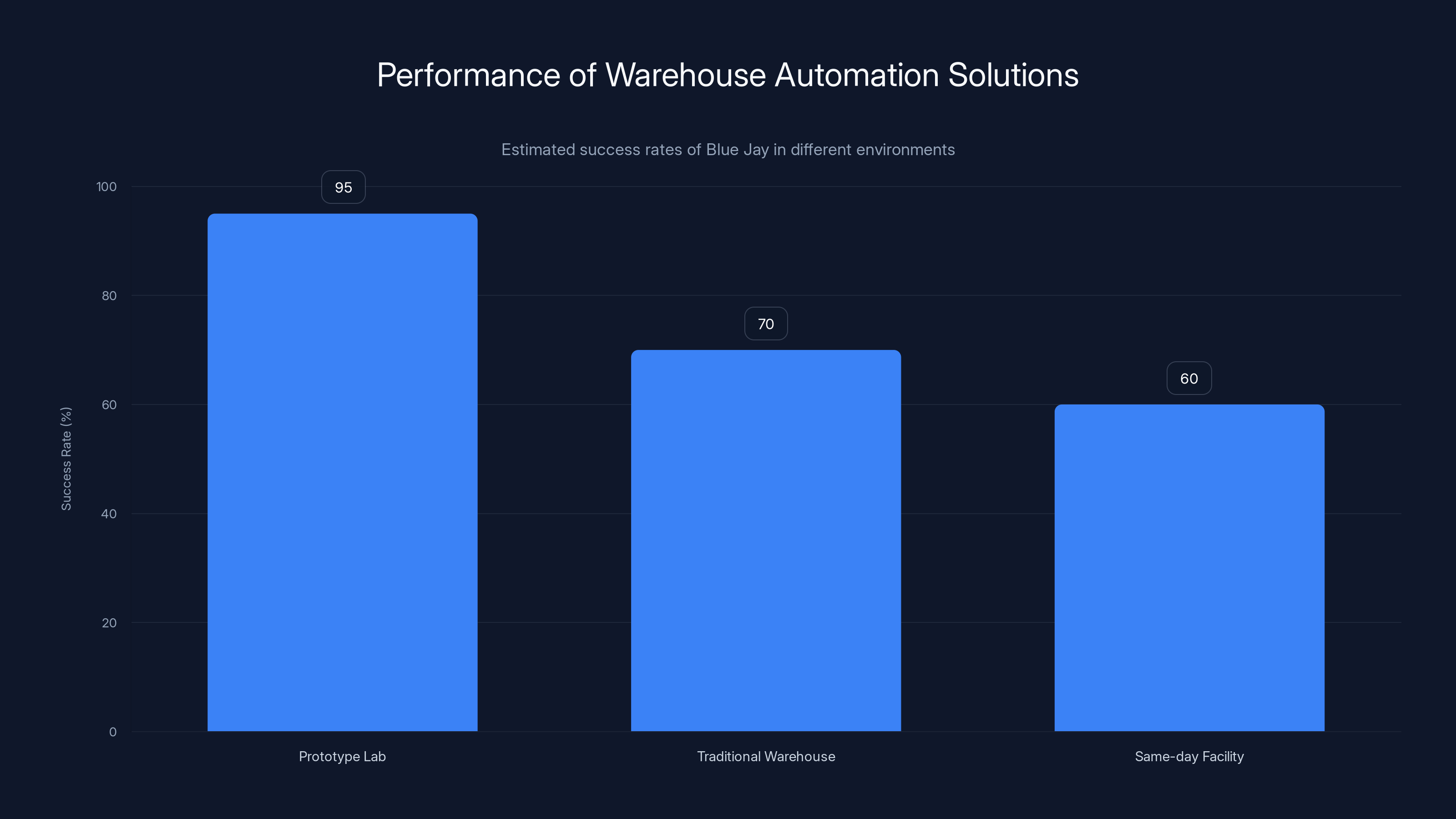

Blue Jay's reliability was estimated at 70-75%, significantly lower than Vulcan's 90% and Kiva's 95%, highlighting its complexity and challenges in achieving operational success. Estimated data.

Understanding What Blue Jay Was Actually Supposed to Do

Let's get specific about Blue Jay's intended function, because this matters for understanding why it failed.

Warehouse automation historically falls into two categories: movement automation and item handling. Movement is solved. Kiva robots move shelves around warehouses. That's the mobile element. But once a shelf reaches a workstation, a human still has to pick items, sort them, and put them where they need to go.

Blue Jay was supposed to be the answer to the picking and sorting problem. A robot with multiple arms, each capable of different tasks. One arm could handle delicate items. Another could move heavier packages. Computer vision would identify what's in front of it and decide what action to take.

This is genuinely hard. Imagine walking into a warehouse bin with 500 different items. Random sizes. Random weights. Some fragile. Some not. All mixed together. A human worker develops intuition for this. A robot needs explicit programming, computer vision training, and manipulation capabilities that work in reality, not theory.

Amazon's same-day delivery facilities are particularly challenging. These aren't traditional warehouses. They're designed for speed. Items come in constantly. Throughput matters more than optimization. The chaos level is higher. The margins are tighter. A robot that works 70% of the time might work fine in a traditional warehouse. In a same-day facility, that's a problem.

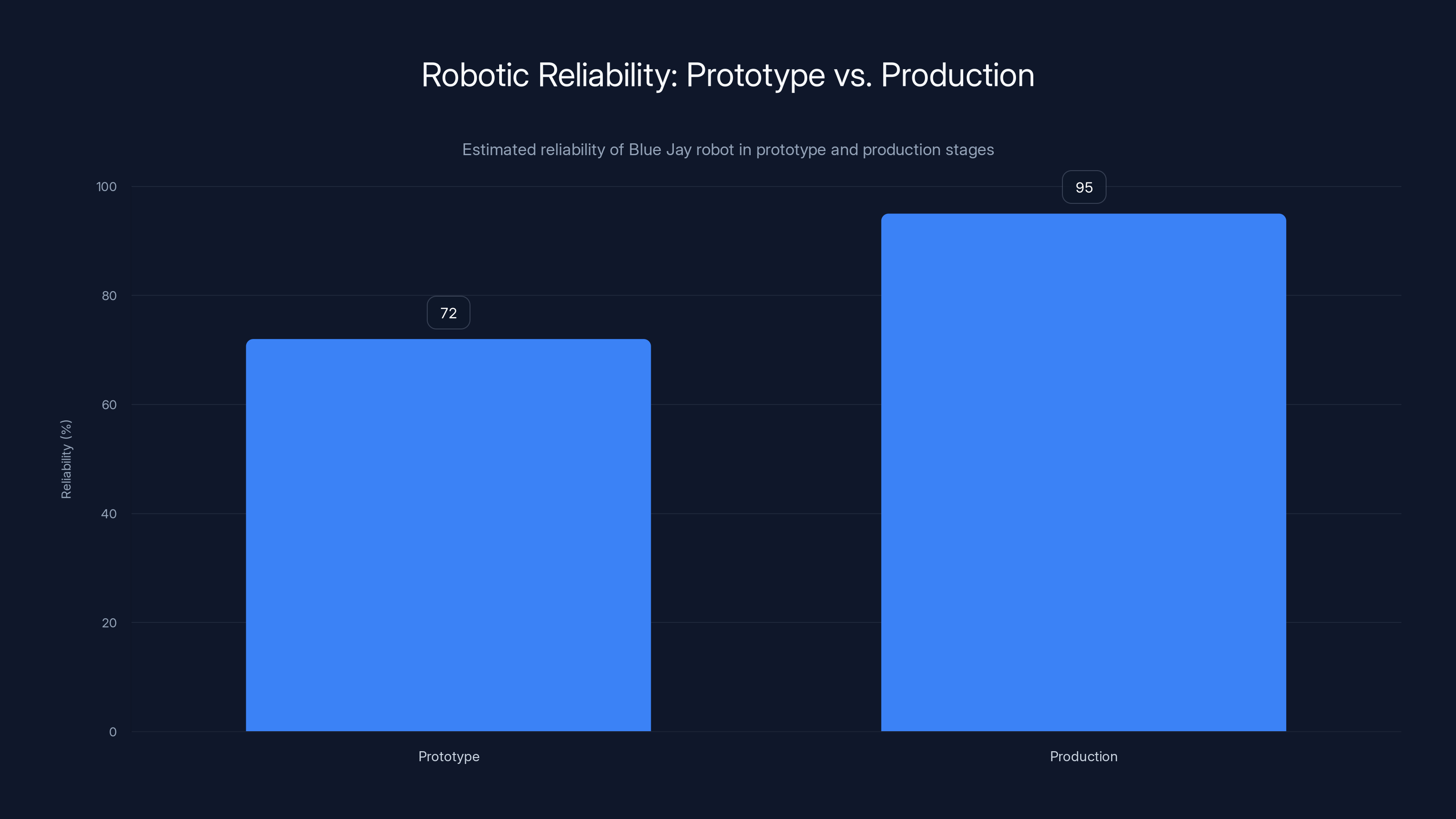

Estimated data shows Blue Jay's prototype reliability at 72%, falling short of the 95% needed for production viability.

Why AI Didn't Actually Solve the Speed Problem

Amazon claimed AI accelerated Blue Jay's development timeline. One year instead of the longer cycles for previous robots. This claim deserves scrutiny.

Machine learning can help with several aspects of robotics: computer vision for object recognition, reinforcement learning for manipulation strategies, simulations that speed up software development, and optimization of motion planning. These are real advantages. But they're not magic.

Here's what AI cannot do: it can't replace the physical engineering required to make a gripper work reliably, to design arms that move smoothly under load, to build systems that don't break after 10,000 operating hours. It can't replace the manufacturing tolerance work needed to produce consistent hardware. It can't replace the real-world testing that catches edge cases AI never saw during training.

What likely happened: Amazon used machine learning to accelerate the software and perception layers of Blue Jay. They trained models on massive datasets of warehouse items. They optimized vision systems. They probably used simulation to test manipulation strategies faster than physical prototyping would allow.

But this only gets you to "prototype that works sometimes." Getting to "production system that works reliably" is a different journey entirely.

The gap between those two states is where Blue Jay probably died. The hardware wasn't ready. The grippers failed too often. The arms got stuck on obstacles. The perception system missed edge cases. The reliability probably hovered around 70-75%, when production needs to be 95%+ for economic viability.

The Economics of Warehouse Robot Failure

Let's do some math on why Blue Jay probably didn't work financially.

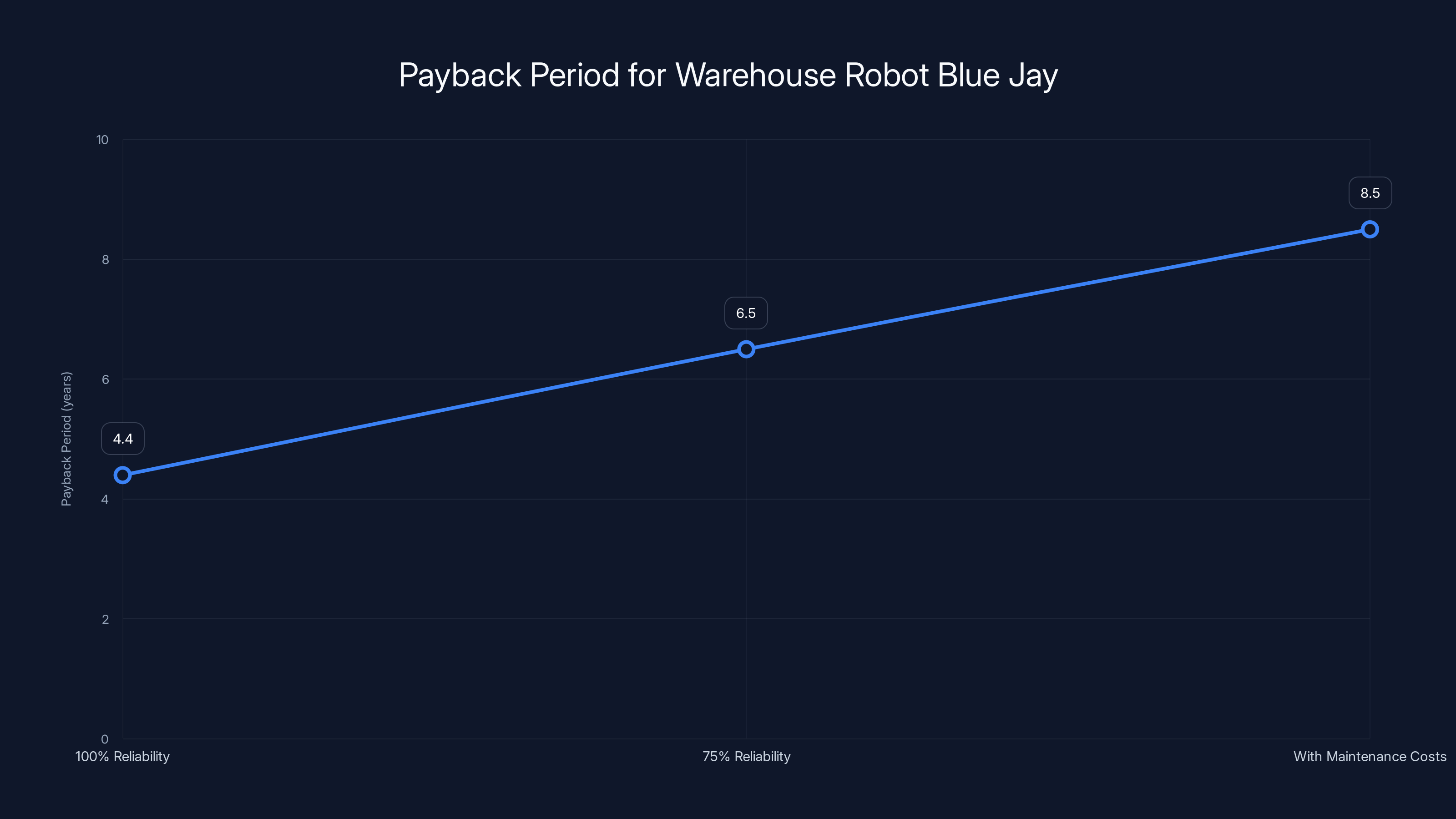

Assume Blue Jay costs around

The payback period calculation looks like this:

That's acceptable if the robot works. But if reliability is only 75%, the effective labor replacement drops significantly. The robot breaks down, needs troubleshooting, requires technician visits. Suddenly the payback period extends to 6-7 years. Add in maintenance costs, spare parts, and retraining staff, and you're looking at 8+ years.

When your typical warehouse equipment has a 10-year useful life, an 8-year payback makes the math very tight. One year of unexpected failures pushes the entire calculation negative.

Amazon has the capital to absorb losses on experimental projects. But they also have an obligation to improve unit economics. A robot that doesn't deliver promised efficiency gains is a sunk cost, not an investment. After six months of testing in South Carolina, Amazon probably concluded Blue Jay wasn't getting to the reliability threshold needed for broader deployment.

Blue Jay's success rate drops significantly from prototype lab conditions to real-world environments, highlighting the challenges of warehouse automation. Estimated data.

Comparing Blue Jay to Amazon's Other Robotics Efforts

Amazon's existing robotics portfolio provides helpful context.

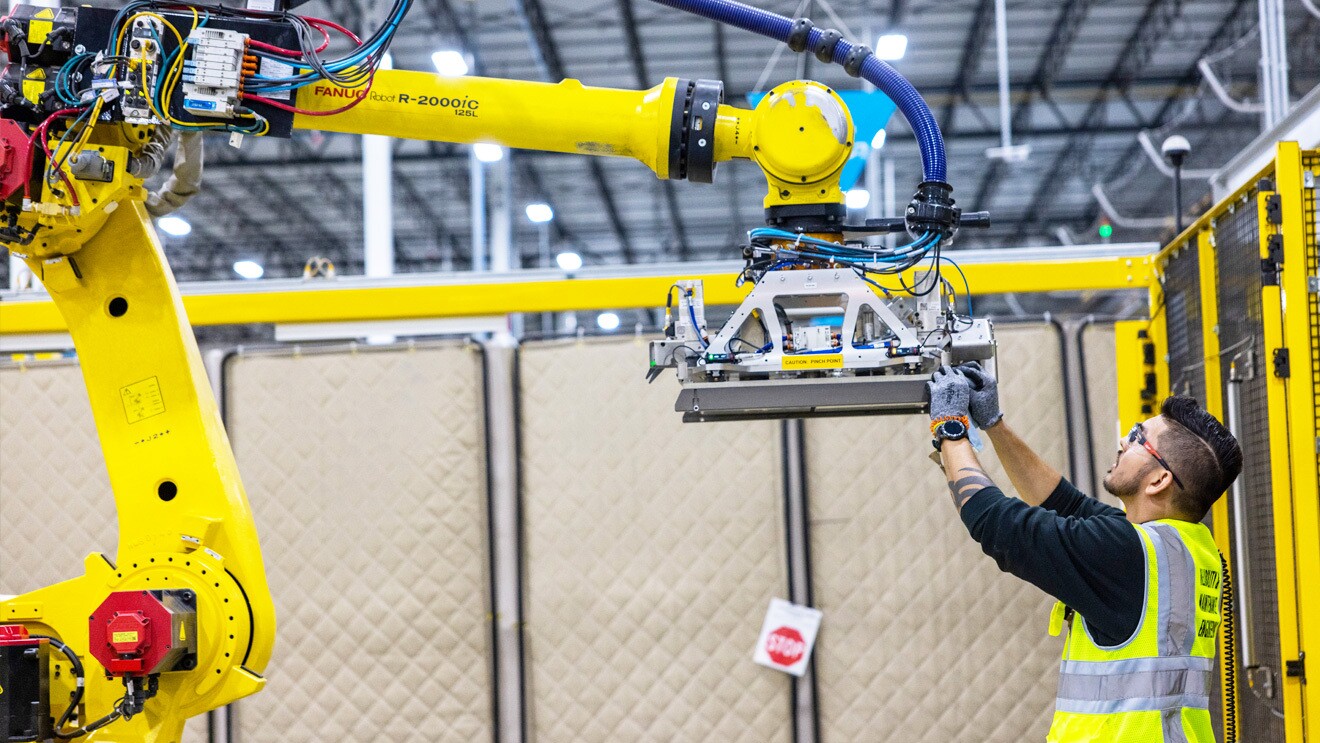

The Kiva robots that Amazon operates by the millions are simple. They move shelves. Wheels, basic navigation, electrical connections. No arms. No complex manipulation. This simplicity is why they work at massive scale. Amazon deployed 1.4 million of them. They're proven. They're profitable. They've been incrementally improved for over a decade.

The Vulcan robot, unveiled around the same time as Blue Jay, is more ambitious than Kiva but less complex than Blue Jay. Vulcan has two arms. One is a manipulator. One has a suction cup and camera for item handling. Vulcan focuses on bin management: organizing items within storage compartments. It's a narrower task than full package sorting.

Likely Vulcan is still operating. It hasn't been canceled (at least not publicly). Why? Probably because its task is more constrained. Organizing items in a bin is easier than sorting mixed packages from a pile. The reliability threshold is easier to achieve. The task is less chaotic.

Blue Jay was trying to be too clever. Too many capabilities. Too many variables. Sorting mixed packages with multiple arms, adapting to different item types and sizes. That's a research problem masquerading as an engineering problem.

Amazon's cancellation of Blue Jay might be the most rational decision the company made. It acknowledged that some problems aren't solved by buying more time or adding more funding. Sometimes you hit a wall that requires fundamental research, not engineering iteration.

The Broader Robotics Industry Context

Blue Jay's failure isn't an Amazon problem. It's an industry problem that Amazon happens to exemplify.

Across the robotics sector, the pattern repeats: impressive prototypes that fail to become reliable production systems. This is sometimes called the "demo-to-deploy gap." It's real and persistent.

Companies like Boston Dynamics have spent years moving quadruped robots from research curiosities to workplace tools. Progress is real but slower than headline announcements suggest. Tesla's Optimus humanoid robot has been "coming next year" for longer than Blue Jay existed. Warehouse automation companies like Brightpicks and Covariant advertise AI-powered picking solutions that still haven't achieved widespread adoption despite years of development.

The consistent problem: reality is more variable than training data. Warehouses have more edge cases than machine learning systems encounter. Hardware fails in ways simulations don't predict. Integration with existing systems creates unexpected friction.

Blue Jay's failure is actually a healthy sign. It means Amazon is willing to kill projects that aren't working rather than throw good money after bad. The alternative is what many companies do: keep funding something that's failing, hoping the next iteration will work, until you've spent hundreds of millions and still don't have a viable product.

Estimated data shows that as reliability decreases and additional costs are considered, the payback period for Blue Jay extends significantly, making it less financially viable.

What Actually Killed Blue Jay: The Technical Reality

We don't have Amazon's internal postmortem, so this is inference. But based on how these projects typically fail, here are the likely technical issues Blue Jay faced.

Perception failures: The robot probably struggled to reliably identify items in cluttered bins. What works with clean lighting and organized objects fails with shadows, reflections, and items packed tightly. Computer vision could be trained on more data, but there's a fundamental limit to how well vision works in real warehouse lighting.

Gripper reliability: Multi-purpose grippers are hard. A gripper soft enough to handle delicate items without damage is often too weak to move heavy packages reliably. The gripper probably had high failure rates on certain item types. Redesigning it would require months of mechanical engineering.

Motion planning under uncertainty: When perception fails, the robot needs to recover gracefully. But recovery in a cluttered bin is hard. A failed pick attempt can move other items, creating cascading failures. The robot probably got stuck in situations it couldn't recover from without human intervention.

Wear and degradation: Multi-armed systems have more points of failure than single-arm systems. Gears wear. Sensors drift. Grippers degrade. After thousands of cycles, reliability probably dropped below acceptable thresholds. Predictive maintenance systems help but can't prevent physical degradation.

Integration friction: Getting Blue Jay to work with existing Amazon systems probably created unexpected complexity. Inventory systems, conveyor integration, software compatibility. The robot probably worked fine in isolation but poorly as part of a larger workflow.

Any one of these issues is solvable with time and money. Together, they create a system that requires fundamental redesign rather than incremental improvement. At some point, you're rebuilding the robot, not improving it. That's when project cancellation becomes rational.

The Role of AI Hype in Blue Jay's Announcement

Amazon's claim that AI accelerated Blue Jay's development deserves more critical examination.

AI hype in 2024-2025 reached fever pitch. Every company was claiming AI breakthroughs. When Amazon announced Blue Jay, positioning it as an AI-accelerated development, it fit perfectly into that narrative. The tech media covered it positively. Investors believed it. It looked like Amazon was winning the AI race.

But here's what probably happened: Amazon used better AI tools in Blue Jay's development (simulation, computer vision, reinforcement learning optimization). These are real improvements. But the fundamental engineering challenges remained the same. The gripper still needed mechanical redesign. The arms still needed to move reliably. The perception system still needed to handle real warehouse complexity.

AI accelerated the development of Blue Jay's software maybe 20-30%. But Blue Jay was 60-70% hardware. You can't AI your way around hardware problems. The announcement made it sound like AI was magic. The product discovered it wasn't.

This is actually a valuable lesson. AI tools genuinely improve development speed in certain domains. Computer vision, simulation, motion planning. But they don't eliminate the hard physics and manufacturing problems that make robotics difficult. Conflating software acceleration with overall project acceleration sets false expectations.

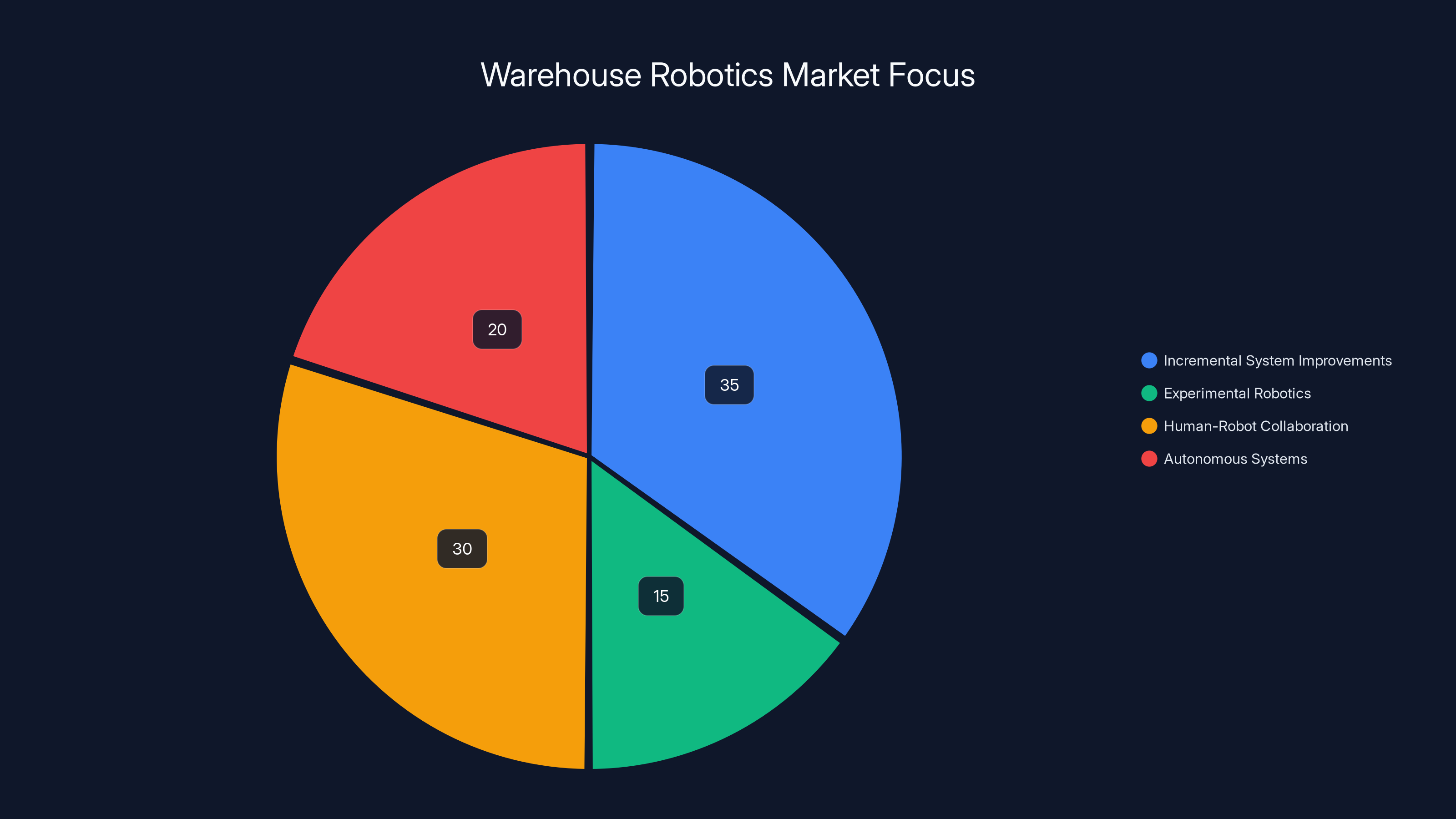

Estimated data suggests a shift towards incremental improvements and human-robot collaboration, with less focus on experimental and fully autonomous systems.

What Happens to Blue Jay's Technology Now

Amazon said Blue Jay's core technology would be "repurposed for other robotics manipulation programs." This is actually typical for canceled projects and probably valuable.

When you build complex robotic systems, even failed ones, you develop useful intellectual property. The gripper design, the motion planning algorithms, the computer vision training data, the mechanical engineering lessons learned. These assets don't disappear just because one product canceled.

Amazon probably extracted value by:

- Taking the perception systems and integrating them into other robots (maybe future versions of Vulcan)

- Using the gripper design as a starting point for simpler, more focused grippers

- Applying motion planning lessons to other manipulation tasks

- Adding Blue Jay's training data to Amazon's broader machine learning datasets

- Using the software architecture as a foundation for future robotics platforms

The people who worked on Blue Jay were moved to "other projects." This is corporate language for: we kept the team, redeployed them. They probably went to Vulcan, future robotics initiatives, or other Amazon robotics labs. That continuity of expertise is valuable.

So while Blue Jay the product failed, Blue Jay's technology might succeed as components of future systems. This is actually how innovation works in hardware. Most incremental progress comes from failed projects whose lessons inform successful ones.

Lessons for Other Companies Pursuing Warehouse Automation

Blue Jay's cancellation offers several concrete lessons for companies building or deploying warehouse automation.

First: Prototype success doesn't predict production success. A robot that works 95% of the time in a lab works 60-70% of the time in a real warehouse. This isn't a surprise to engineers, but it's news to executives and investors. When evaluating warehouse automation, separate prototype demonstrations from production-level systems.

Second: Complexity is the enemy of reliability. Simple systems scale. Kiva robots are simple. They work reliably at massive scale. Complex systems like Blue Jay are harder to make reliable. If you're building automation, start simple. Expand capability only if simple systems work reliably first.

Third: Real-world data doesn't exist until you're in the real world. Machine learning systems are trained on data. But real warehouses contain edge cases, chaos, and variations that don't exist in training data. You can't avoid this gap through more simulation or larger datasets. You have to accept that field deployment will reveal problems.

Fourth: Payback period assumptions need to account for reliability gaps. Most warehouse automation ROI calculations assume 95%+ reliability. When reliability is actually 75%, the payback period extends dramatically. Build in contingency.

Fifth: Moving from one location to another is harder than moving from prototype to one location. South Carolina testing was one facility, one set of conditions, one team supporting it. Scaling to multiple facilities creates variability that breaks marginal systems. Blue Jay probably failed not because the concept was wrong but because it couldn't scale.

Amazon's robotic fleet has grown significantly, from zero in 2012 to over 1.4 million by 2025, showcasing the company's rapid expansion in automation technology. Estimated data.

The Future of AI in Warehouse Robotics

Despite Blue Jay's failure, AI will continue to play an important role in warehouse automation. But probably not in the ways the hype suggests.

AI isn't going to magically make fragile hardware reliable. It isn't going to solve mechanical problems. It isn't going to eliminate the gap between prototype and production. But it will help in specific ways:

Computer vision will improve. Multi-modal foundation models that understand vision, language, and robotics will make object recognition more robust. This helps with perception systems like the ones that probably failed in Blue Jay.

Simulation will improve. Better physics simulation in game engines means robots can be trained more efficiently in digital environments. This shortens development cycles, even if it doesn't solve real-world problems.

Optimization will improve. Machine learning can optimize motion planning, gripper design, and task sequencing better than human engineers iterating. This makes existing systems more efficient.

Predictive maintenance will improve. AI systems can predict component failures before they happen, reducing unexpected downtime. This improves actual reliability even if peak reliability doesn't change.

But the fundamental constraint remains: you need reliable hardware. AI doesn't fix that. You need robust mechanical design. AI doesn't fix that either. You need real-world testing. No amount of simulation replaces it.

The companies that will succeed in warehouse automation are the ones that accept these constraints rather than trying to overcome them with more AI hype. Simple systems, reliably implemented, with conservative expansion strategies. That's boring. That's also how Kiva robots became the 1.4 million unit success story that Blue Jay aspired to.

Industry Implications and Market Shifts

Blue Jay's cancellation signals something larger about the robotics market.

For years, warehouse automation has been positioned as an inevitable upgrade. Every major fulfillment center will be automated. Robots will replace workers. This vision is real but slower to arrive than optimists predicted. Physical constraints are real. Economics are tight. Reliability is hard.

Blue Jay's failure suggests Amazon is recalibrating expectations. Rather than betting heavily on next-generation hardware, Amazon might focus on incremental improvements to existing systems. More Kivas. Better software for Kiva systems. Optimization of existing infrastructure.

Other robotics companies should notice. If Amazon can't make multi-armed warehouse robots work economically at scale, neither can anyone else. This might actually accelerate consolidation in the warehouse robotics space. Companies building experimental robots might struggle to fundraise once Amazon's failure becomes widely known.

Conversely, companies with proven systems (like the Kiva robots) become more valuable. Reliability trumps capability. A robot that works 95% of the time is worth more than a robot that works 80% of the time with more features.

We might see a shift from "replace humans with robots" to "augment humans with robots." Rather than fully autonomous picking, robots handle specific tasks while humans handle the complex judgment calls. This is actually more economically sound and probably what will dominate the next decade.

Why Companies Keep Announcing Failed Projects

This is worth examining separately, because it's a pattern.

Amazon announced Blue Jay publicly. The company probably knew there was significant risk it might not work. Yet they announced it at a major event. Why?

A few reasons. First, morale. Employees working on moonshot projects want recognition. Announcing a project publicly energizes teams. Second, investor relations. Showing innovation pipelines impresses investors. Third, recruiting. "We're building next-generation warehouse robots" attracts talent. Fourth, narrative. Amazon wants to be seen as an innovation leader, not just an ecommerce company.

But there's a downside: when projects fail, there's reputational cost. Not huge cost. People forget. But it contributes to a sense that companies overpromise on AI and robotics.

The better approach would be to announce after proof of concept rather than at concept stage. But that's not how PR works in tech. The incentive structure favors early announcements, which sometimes lead to embarrassing cancellations.

This is useful context when evaluating any company's robotics announcements. Take them as intentions, not promises. Expect some percentage to fail in transition to production. This is normal and healthy. It's how innovation works.

What Blue Jay Means for Warehouse Workers

One more perspective worth considering: the human element.

When Blue Jay was announced, there was implicit messaging about worker displacement. A sophisticated robot that replaces humans. A future where warehouses are fully automated. This narrative is economically appealing to some, threatening to others.

Blue Jay's failure is actually good news for warehouse workers. It resets the timeline for automation. Rather than rapid replacement over 5 years, the transition will take 15-20 years. Probably longer. Not because the vision is impossible but because the execution is harder than anticipated.

This isn't just sentiment. It's economically real. Systems that don't work reliably can't be deployed at scale. Workers can't be replaced by systems that work 75% of the time. Humans still need to handle exceptions. Until automation gets more reliable, humans remain the better economic choice.

The irony is that better automation for warehouse workers might come through different means than humanoid or multi-armed robots. Exoskeletons that reduce injury. Better lighting and ergonomics. Smaller, focused robots that handle specific subtasks. These incremental improvements might be more valuable than the moonshot of fully autonomous robots.

Key Takeaways: What Blue Jay's Failure Teaches Us

Let's synthesize what we've learned.

Blue Jay was a sophisticated multi-armed warehouse robot that Amazon announced in October after claiming one year of development accelerated by AI. The company canceled it by February after realizing it didn't meet reliability thresholds for production deployment. The core technology will be repurposed in future projects. The team was redeployed.

This failure, despite seeming like a setback, is actually a sign of healthy decision-making. Amazon recognized a problem and stopped throwing money at it. Too many companies do the opposite.

The broader lessons: robotics breakthroughs take longer than AI hype suggests. Hardware reliability remains the bottleneck. Simple systems scale better than complex ones. Prototype success doesn't predict production success. Machine learning accelerates software development but not mechanical engineering. Skepticism about warehouse automation timelines is justified by real-world evidence.

For people investing in, building, or deploying warehouse automation: expect longer timelines, lower initial reliability, and higher costs than vendors promise. Simple systems are more valuable than sophisticated ones. Proven deployments matter more than announcements. Real-world data always reveals problems that simulation missed.

For the industry: Blue Jay's cancellation might actually accelerate progress. It removes a distraction. It resets expectations. It signals that Amazon, the biggest player in the space, is being selective about robotics investments rather than funding every idea. Other companies might make similar choices.

The future of warehouse automation is real. But it looks more like incremental improvements to existing systems than revolutionary leaps. More Kivas. Better software. Focused robots for specific tasks. Humans in the loop. Longer timelines. This is less exciting than the Blue Jay announcement, but probably more realistic.

FAQ

What was Blue Jay and what was it designed to do?

Blue Jay was a multi-armed warehouse robot announced by Amazon in October 2025, designed specifically for sorting and moving packages in same-day delivery facilities. The robot featured sophisticated manipulation capabilities to handle mixed package types, sizes, and weights. It represented Amazon's attempt to automate the last-mile sorting problem that previously required human workers to manually process and route packages.

Why did Amazon cancel the Blue Jay project?

Amazon likely canceled Blue Jay because the system failed to achieve the reliability thresholds necessary for profitable production deployment. Prototype reliability probably hovered around 70-75%, while production systems require 95%+ reliability to be economically viable. The cost-benefit analysis likely showed that the extended payback period (7-8+ years instead of 4-5 years) made continued investment unjustifiable when Blue Jay's intended market could still be served by human workers or existing robots.

How does Blue Jay's failure compare to Amazon's other robotics projects?

Amazon's existing Kiva robots, deployed by the millions since 2012, succeed because they perform simple tasks: moving shelves from point A to point B. They lack complex manipulation capabilities. The newer Vulcan robot, which handles bin organization with two arms, is more sophisticated than Kiva but far simpler than Blue Jay. Vulcan has survived where Blue Jay failed, likely because organizing items within a bin is a more constrained problem than sorting mixed packages from a chaotic pile. Complexity directly correlates with failure rates in robotics.

What role did AI play in Blue Jay's development and failure?

Amazon correctly used AI to accelerate software and perception components, probably improving development speed by 20-30% through better computer vision, simulation, and motion planning. However, AI cannot overcome fundamental hardware challenges: gripper reliability, mechanical wear, integration friction, and real-world perception failures. The claim that AI would fundamentally solve warehouse robotics proved optimistic. AI accelerated the development of software, not the mechanical systems that actually interact with packages.

What are the broader lessons from Blue Jay's failure for warehouse automation?

Key lessons include: prototype success doesn't predict production success; simple systems are more reliable than complex ones; real-world edge cases aren't captured in training data; payback period assumptions need contingency for reliability gaps; moving from one location to multiple locations dramatically increases complexity; and AI hype often masks hardware constraints that AI cannot solve. These lessons suggest that warehouse automation will progress more slowly and through incremental improvements rather than revolutionary leaps.

How does Blue Jay's cancellation affect warehouse workers and employment?

Blue Jay's failure is actually positive for warehouse workers because it extends the timeline for automation. Rather than rapid replacement over 5 years, the realistic timeline for meaningful automation extends to 15-20+ years. Evidence shows that despite 1.4 million robots in Amazon warehouses, employment has grown rather than shrunk, because e-commerce volume growth outpaced automation deployment. Workers can transition to new roles during this extended timeline rather than facing sudden displacement.

What will Amazon do with Blue Jay's technology now that the project is canceled?

Amazon stated that Blue Jay's core technology will be repurposed for other robotics "manipulation programs." Practically, this means extracting valuable components: perception systems may be integrated into future versions of Vulcan; gripper designs will inform future robot development; motion planning algorithms will be applied to other tasks; training data will enhance Amazon's broader machine learning capabilities; and software architecture will serve as a foundation for future robotics platforms. The team was redeployed to other projects, preserving the human expertise developed.

Why do companies keep announcing projects that might fail?

Companies announce early-stage projects for several strategic reasons: to energize employees working on ambitious projects; to impress investors with innovation pipelines; to strengthen recruiting narratives around cutting-edge work; and to build corporate identity as innovation leaders. The downside is reputational cost when projects cancel. However, the incentive structure in tech PR favors early announcements, so this pattern will likely continue. This suggests investors and observers should treat robotics announcements as intentions rather than guarantees.

How long will it take for warehouse robotics to become truly autonomous and ubiquitous?

Based on Blue Jay's failure and broader industry patterns, meaningful warehouse automation deployment will likely take 15-20+ years, not 5-10 years as optimists predicted. Simple systems like Kiva robots can scale quickly because reliability is easier to achieve. Complex manipulation tasks require fundamental breakthroughs in mechanical reliability, real-world perception, and integration. The bottleneck remains hardware engineering, not AI. Companies making conservative estimates about automation timelines are likely more accurate than those claiming imminent wholesale replacement of human workers.

What types of warehouse robots are more likely to succeed than multi-armed systems like Blue Jay?

Simpler, more focused robots are more likely to succeed: single-task robots that handle specific, constrained operations; systems that augment human workers rather than replace them entirely; robots designed for lower-throughput environments where 85-90% reliability is acceptable; and incremental improvements to proven systems like Kiva. The industry is likely shifting from "replace humans entirely" toward "humans-plus-robots hybrid workflows" because hybrid approaches are economically viable with current technology while fully autonomous systems remain unreliable at scale.

Navigating the Future of Warehouse Automation

Blue Jay's story is ultimately about the gap between aspiration and reality in robotics. It's a reminder that announcements aren't promises, that AI doesn't solve physics problems, and that manufacturing constraints are real and persistent.

But it's also a sign that the industry is maturing. Amazon's willingness to cancel a project that wasn't working shows discipline. The company understood that throwing more money at a failing system doesn't make it work. That's the kind of clear-eyed decision-making that leads to real progress.

Warehouse automation will continue advancing. The Kiva robots will improve. Vulcan will expand. New robots will emerge. But the pace will be measured. The reality will be messier than the announcements. Workers will adapt. The timeline will extend. And that's probably healthier for everyone involved than a rapid disruption based on technology that isn't actually ready.

The next big robotics breakthrough probably won't be announced at flashy events. It will be quietly deployed somewhere, work reliably for two years, and only then become visible when adoption accelerates. That's how real innovation happens.

Blue Jay's failure is actually bullish for warehouse automation in the long run. It removes unrealistic expectations. It resets the timeline. It shows that the industry will accept only systems that actually work. That's the foundation for sustainable progress.

Related Articles

- Humanoid Robots in Factories: The Real Shift Away From Labs [2025]

- Aurora's Driverless Trucks: The Superhuman Era of Autonomous Freight [2025]

- Aurora Triples Driverless Truck Network: The Future of Autonomous Logistics [2025]

- Lidar & Vision Sensor Consolidation Boom [2025]

- How Digital Technology Solves UK Manufacturing's Workforce Crisis [2025]

- Biomimetic AI Robots: When Technology Crosses Into the Uncanny Valley [2025]

![Amazon's Blue Jay Robotics Project Failure: What Went Wrong [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/amazon-s-blue-jay-robotics-project-failure-what-went-wrong-2/image-1-1771439849244.jpg)