Introduction: When Robots Outrun Humans

It happened. The moment that some thought wouldn't arrive for another decade just became reality. Aurora's driverless trucks can now haul freight 1,000 miles from Fort Worth to Phoenix in 15 hours straight, with zero human intervention. No breaks. No fatigue. No human driver trading off with another driver halfway through. Just consistent, relentless logistics execution.

For context, that's superhuman in the literal sense. Federal regulations mandate truck drivers stop for 30 minutes after eight hours of driving. They can't legally operate for more than 11 hours at a time. Then they need a mandatory 10-hour rest period before they're allowed back in the cab. So the fastest a human driver can legally complete that same route takes significantly longer, even with perfect conditions and no unforeseen delays.

Aurora CEO Chris Urmson called it "the dawn of a superhuman future for freight" during the company's earnings call. But here's what matters beyond the marketing language: this represents a genuine inflection point. Autonomous trucking isn't theoretical anymore. It's not a pilot program with observers in the cab and safety protocols that make the whole operation feel cautious. Aurora has crossed the line from "promising technology company" to "actual commercial operator generating revenue."

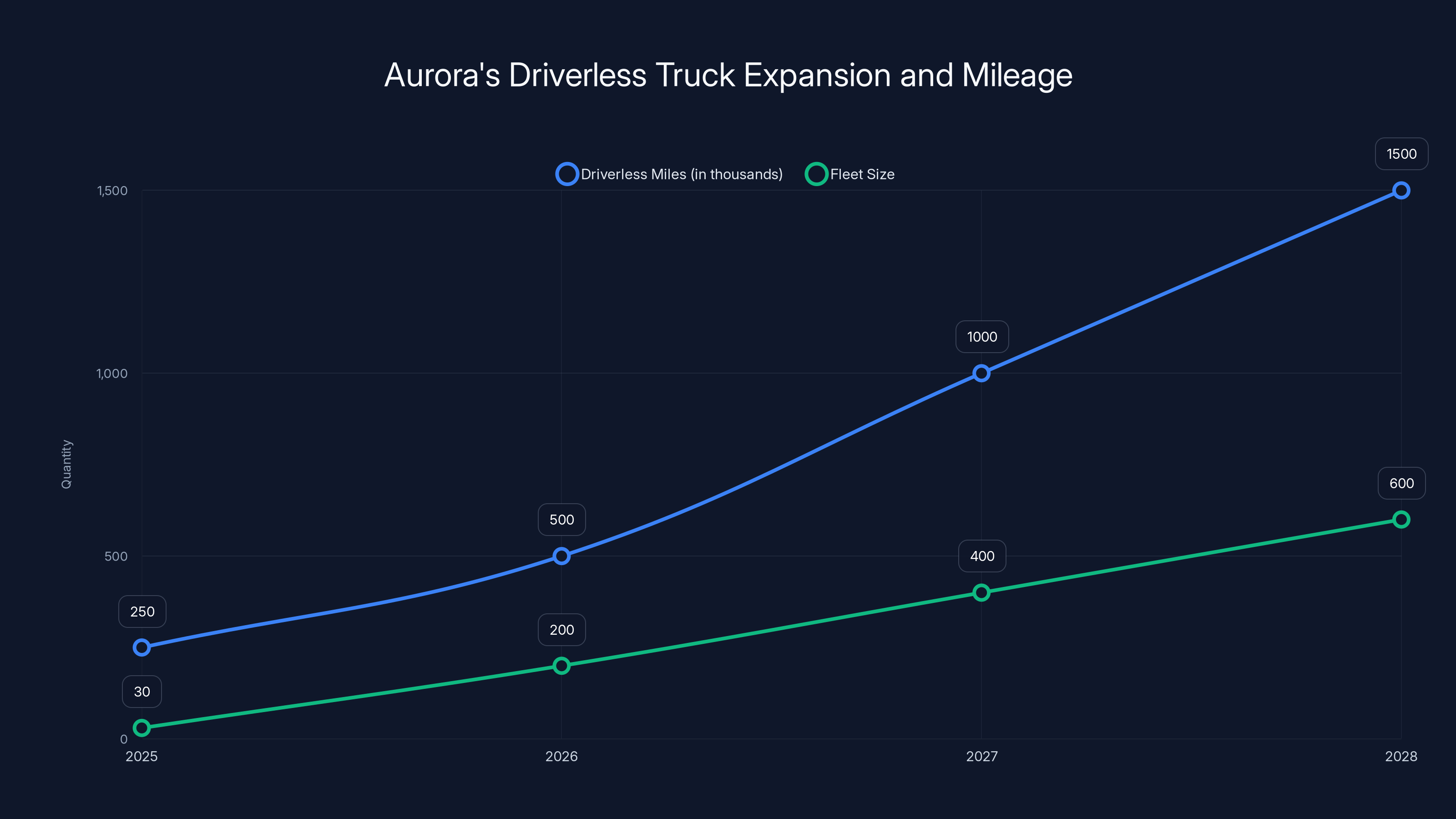

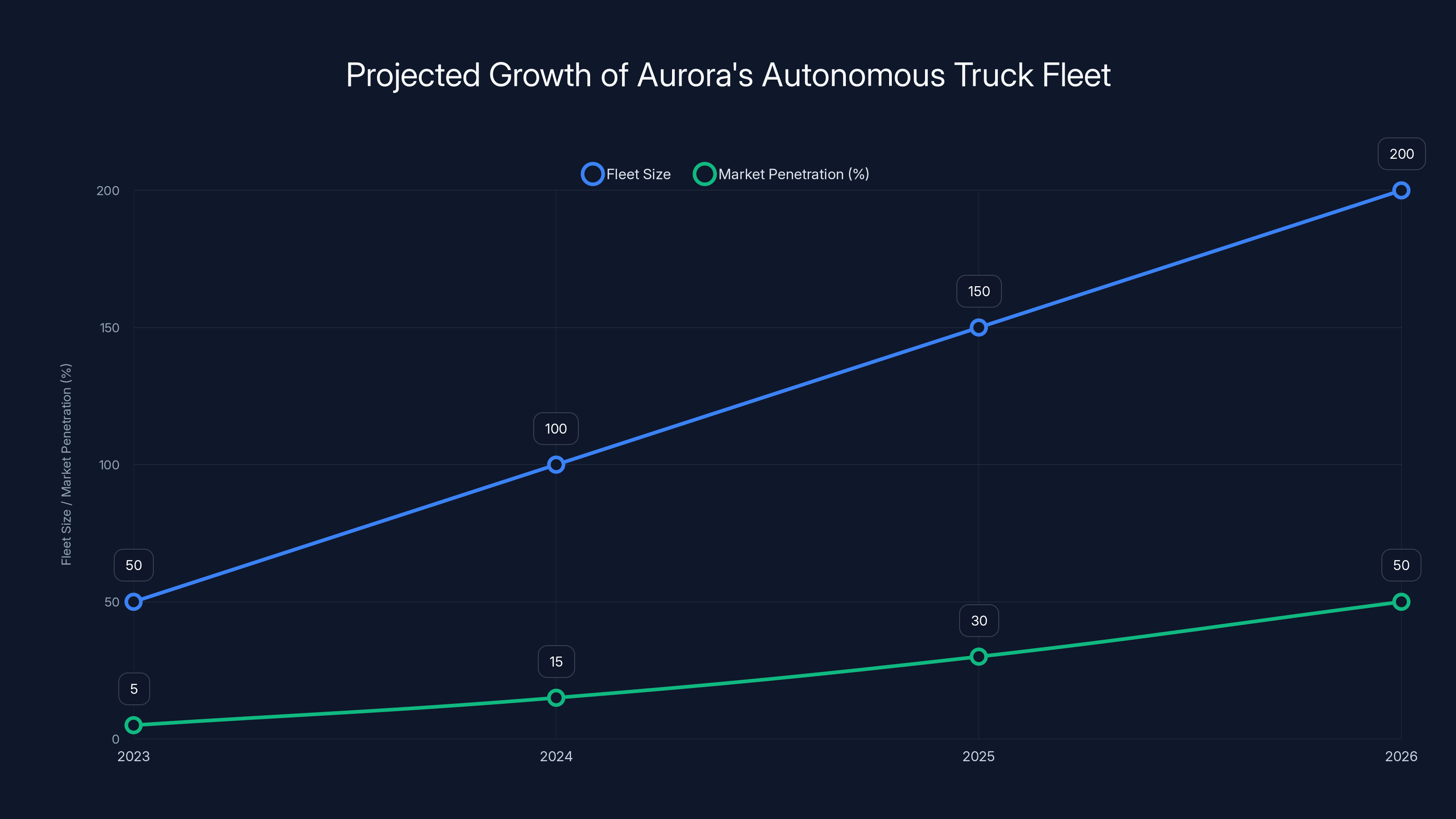

The company deployed its first revenue-generating driverless trucks in April 2025. By the end of that year, they'd racked up 250,000 driverless miles with a perfect safety record. They're already planning to expand their fleet from 30 trucks today to over 200 by year-end 2026. And they're moving faster geographically too, with operations across Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona, and expansion planned for Nevada, Oklahoma, Arkansas, Louisiana, Kentucky, Mississippi, Alabama, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida.

This article dives deep into what Aurora has actually achieved, why it matters for logistics economics, what challenges remain, and what this means for truck drivers, logistics companies, and the future of freight transportation. Because this isn't just a tech story. It's an economic story. A labor story. And ultimately, it's a story about how fast we're moving into a genuinely different future.

The Technical Breakthrough: How Aurora's System Actually Works

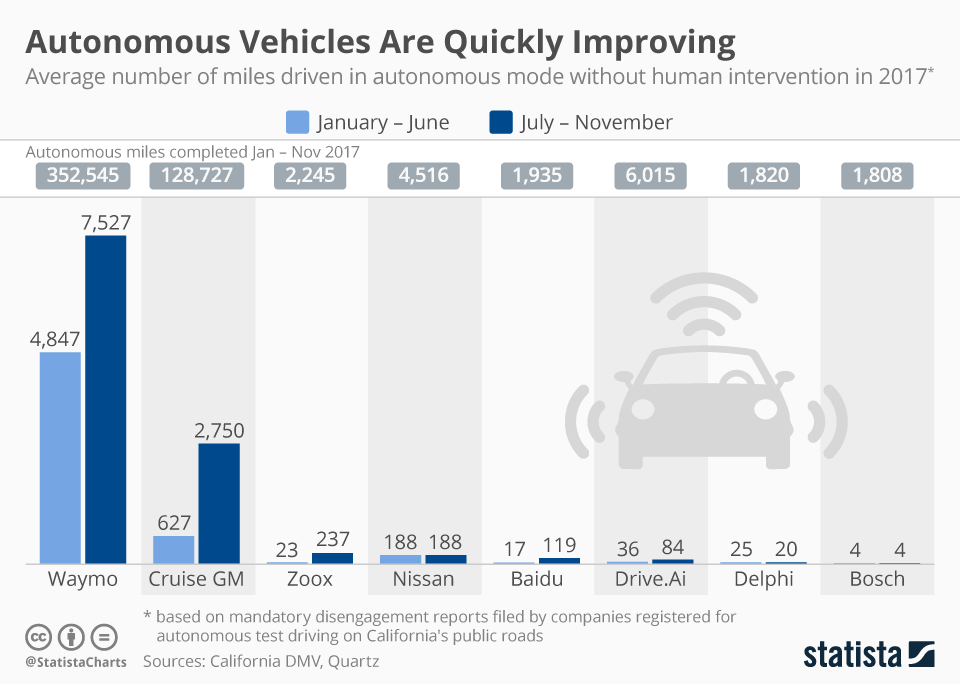

Let's start with the honest part: Aurora isn't the only company working on autonomous trucks. Waymo has robotaxis humming around Phoenix. Tesla has Cybercabs. But Aurora has something different. They're not chasing the consumer market. They're solving a specific, massive problem in a specific geography with a specific business model.

The Fort Worth-to-Phoenix route was chosen deliberately. It's primarily highways. The weather in the Sun Belt, while extreme, is predictable. There are fewer edge cases than, say, snow storms in Minnesota or rain in Seattle. Aurora's software has been trained relentlessly on exactly these conditions.

The company's approach has been incremental validation. Their fourth software release (as of early 2026) is the one that finally handles the full 1,000-mile route. The first release validated daytime operations between Dallas and Houston. The second validated nighttime driving. The third added El Paso. Now they can handle the geographic diversity and climate variations across the entire southern corridor.

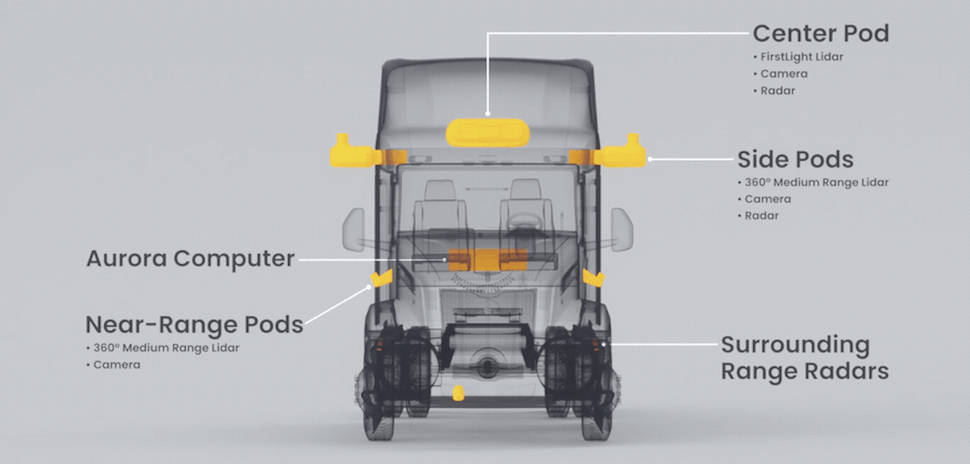

Under the hood, Aurora's system uses a combination of LIDAR (light detection and ranging sensors), cameras, and radar. The system constantly builds a three-dimensional model of the environment in real-time. It's not just identifying what's in front of the truck. It's understanding road geometry, lane markings, other vehicles, pedestrians, animals, debris, weather conditions, and road hazards simultaneously.

The software makes decisions at a speed that humans can't match. When a deer jumps into the road, or a car swerves unexpectedly, or road construction suddenly appears, the system reacts in milliseconds. That's not hype. That's computational reality. A human driver needs time to process, decide, and physically react. A computer system operates at electronic speeds.

Here's what's genuinely impressive: Aurora's trucks have achieved this with relatively minimal human intervention. Current operations use Paccar trucks with human safety observers, but that's contractual caution from the truck manufacturer, not a technical necessity. By Q2 2026, Aurora plans to deploy International Motors LT trucks with zero humans on board. That's the real litmus test.

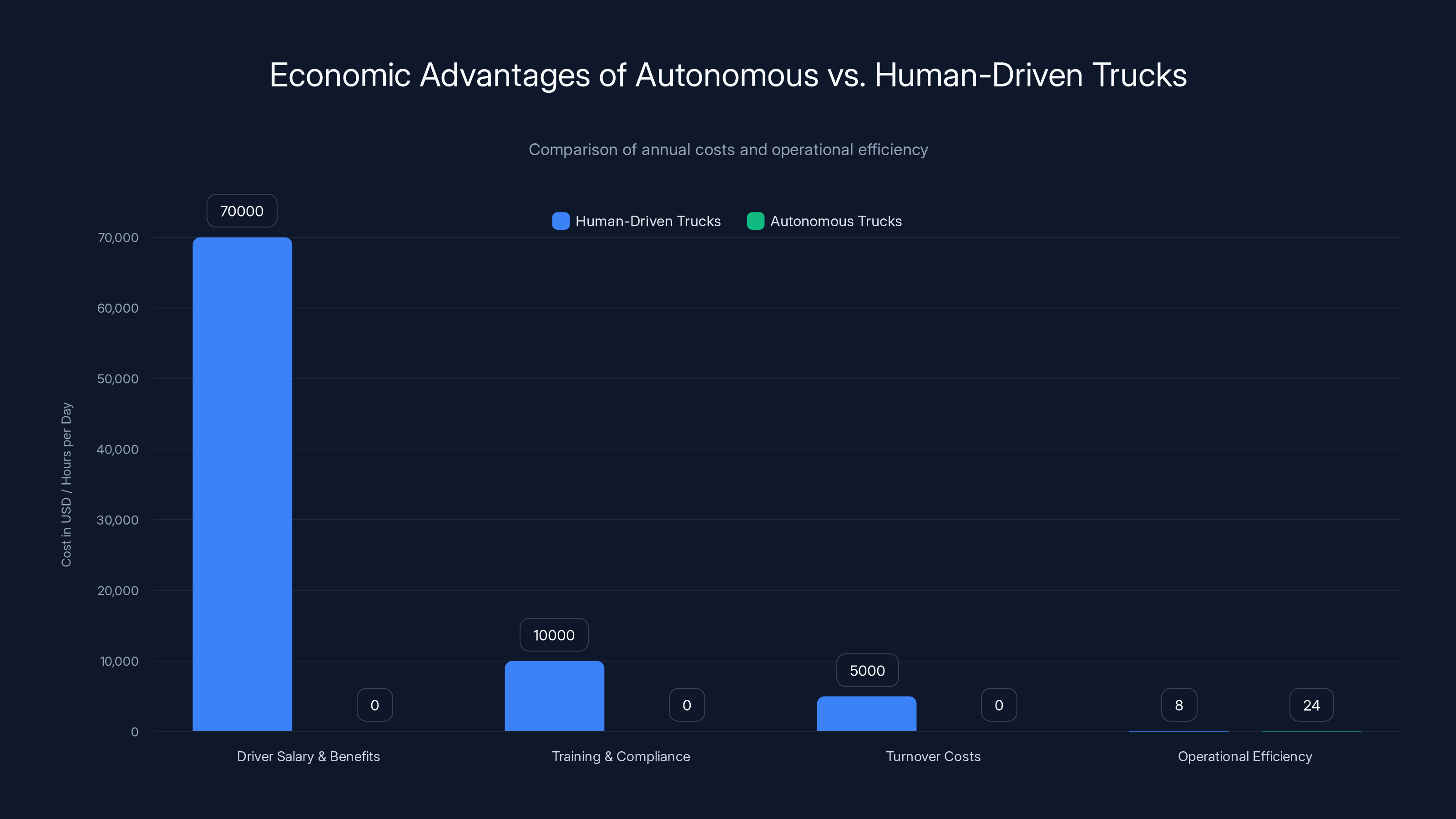

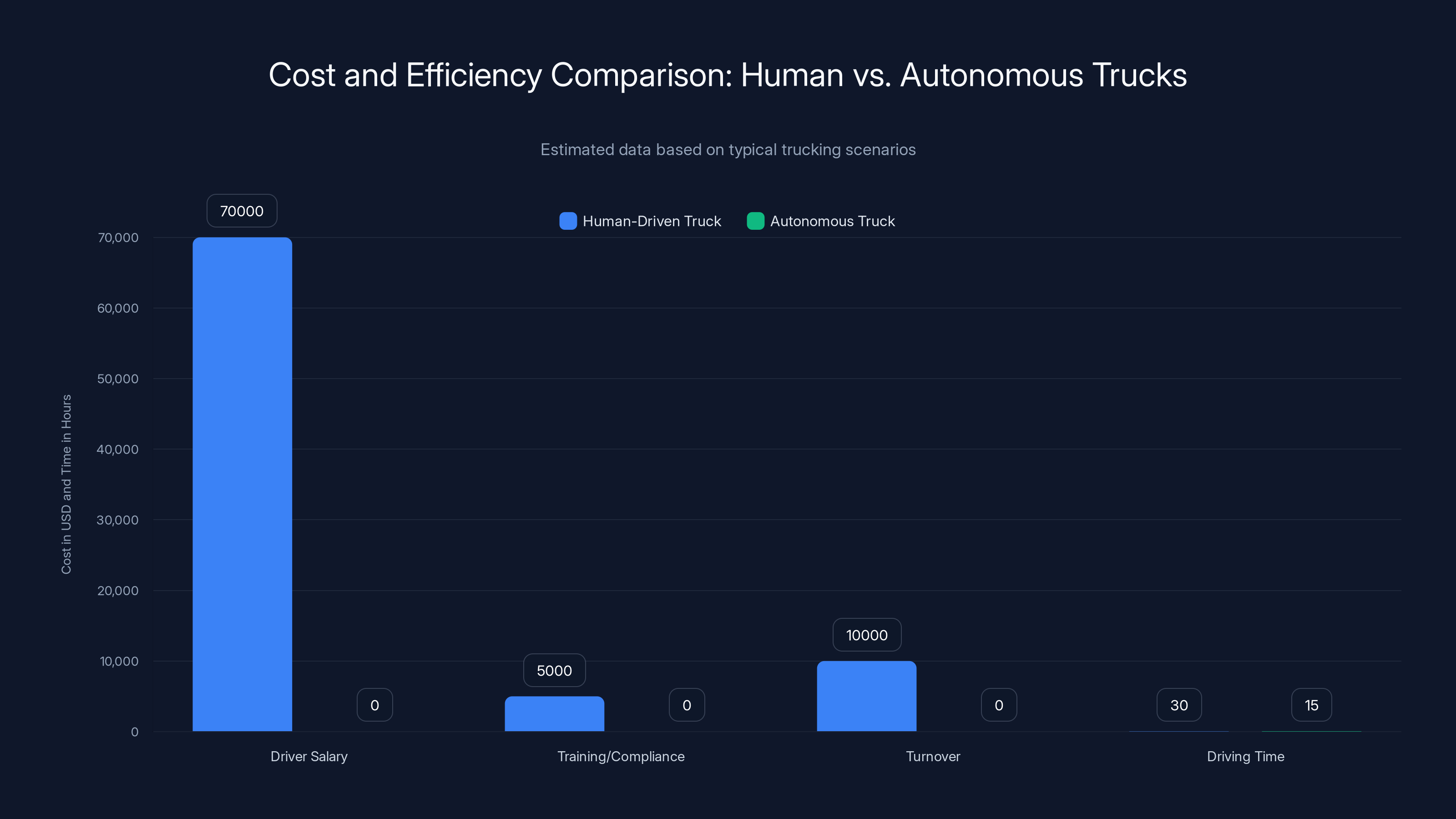

Autonomous trucks eliminate driver-related costs and can operate continuously, unlike human-driven trucks which are limited by federal regulations. Estimated data.

The Economics: Why This Matters to Your Supply Chain

Now let's talk money, because that's what actually drives adoption.

A typical semi truck driver costs trucking companies roughly

But there's more. Human drivers are constrained by regulations that create inefficiency. The 11-hour driving limit with mandatory rest periods means that a 1,000-mile haul that takes an autonomous truck 15 hours takes a human driver 2-3 days when you account for breaks and mandatory rest periods. That's a game-changing difference for perishable goods, time-sensitive freight, and just-in-time supply chains.

Aurora has publicly stated that its system can eventually cut transit times nearly in half compared to conventional trucking. That sounds hyperbolic until you think about it. If an autonomous truck can run continuously while respecting safety margins, and a human driver has mandatory downtime, the math is simple.

Let's do some rough numbers. Assume a logistics company needs to move 100 shipments per month on the Fort Worth-to-Phoenix route. With human drivers, each shipment takes roughly 30 hours of driving time plus downtime and handoff time. With Aurora's system, that same shipment takes 15 hours. You just halved your cycle time. Your capital asset (the truck) is moving freight twice as fast. Your operational costs per mile might be slightly higher initially (maintenance, insurance for autonomous systems), but the revenue per truck per month increases dramatically.

Companies like Hirschbach, an early adopter on the Fort Worth-to-Phoenix route, apparently agree. They signed up. So did Uber Freight, Werner, Fed Ex, and Schneider. These aren't startups betting on unproven tech. These are major logistics players with real money on the line.

Aurora recognized

Autonomous trucks eliminate driver-related costs and halve driving time, enhancing supply chain efficiency. Estimated data.

The Safety Question: How Autonomous is Actually Safe?

Let's address the elephant in the truck cab: safety.

Aurora claims a perfect safety record across 250,000 driverless miles as of January 2026. That's actually significant. Modern human drivers average about one accident per 500,000 miles. So a perfect safety record over 250,000 miles isn't statistically conclusive proof of superhuman safety, but it's not concerning data either.

Here's the honest complexity: autonomous truck safety is genuinely hard to measure. You can't just extrapolate one metric. You have to ask: what kinds of accidents? What were the circumstances? What does the comparison baseline actually mean? Human drivers have 80+ years of collective driving experience behind them, developed through trial and error and natural selection (bad drivers die or quit; good ones stay). Autonomous systems have whatever data they've been trained on.

But there's a genuine advantage here. Autonomous systems don't get tired. They don't get distracted. They don't check their phones, eat, adjust the radio, or get road rage. Fatigue is actually one of the leading causes of truck accidents, contributing to thousands of deaths annually. A system that literally cannot fatigue has a structural safety advantage.

Aurora's approach seems to be: build it carefully, deploy it carefully, expand cautiously, and let the safety record speak for itself. They're not pushing into Minnesota winters or mountain passes yet. They're staying on well-mapped, relatively controlled highways in predictable climates. That's smart. Build confidence before tackling edge cases.

The regulatory environment is also friendlier than it might seem. States like Arizona and Texas have been relatively permissive with autonomous vehicle testing. The federal government hasn't mandated specific autonomous trucking regulations yet, which creates both opportunity and risk. Opportunity because companies can innovate faster. Risk because a catastrophic accident could trigger heavy-handed regulation.

The Route Expansion Strategy: Sun Belt Dominance

Aurora's expansion strategy reveals some thinking about where autonomous trucking works best.

Today, they operate routes between Dallas-Houston, Fort Worth-El Paso, El Paso-Phoenix, Fort Worth-Phoenix, and Laredo-Dallas. The map looks like they're painting the Sun Belt. That's deliberate. The Sun Belt has consistent highways, minimal winter weather, relatively predictable traffic patterns, and major logistics hubs (Dallas, Houston, Phoenix). It's the right place to build an autonomous trucking business.

The company announced plans for future operations in Nevada, Oklahoma, Arkansas, Louisiana, Kentucky, Mississippi, Alabama, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida. That's essentially a half-circle around the southern United States. If Aurora can dominate the Sun Belt with autonomous trucking, they'll have access to some of the highest-value freight corridors in the country.

Here's why the geography matters. The Fort Worth-to-Phoenix corridor isn't random. There's actually substantial freight movement along that route because it connects two major logistics hubs and multiple manufacturing centers. Same with Dallas-Houston. And Laredo, which sits on the Mexico-US border, is critical for cross-border logistics. Aurora is targeting high-volume routes where the economics work.

Expansion to Florida or Georgia or North Carolina involves different logistics ecosystems but the same climatic advantage: no snow, no ice, no extreme cold weather edge cases. Autonomous systems struggle more in those conditions. Sensors get blocked. Road markings disappear under snow. Recovery from skids becomes harder. By staying in the Sun Belt initially, Aurora avoids those problems while building scale and confidence.

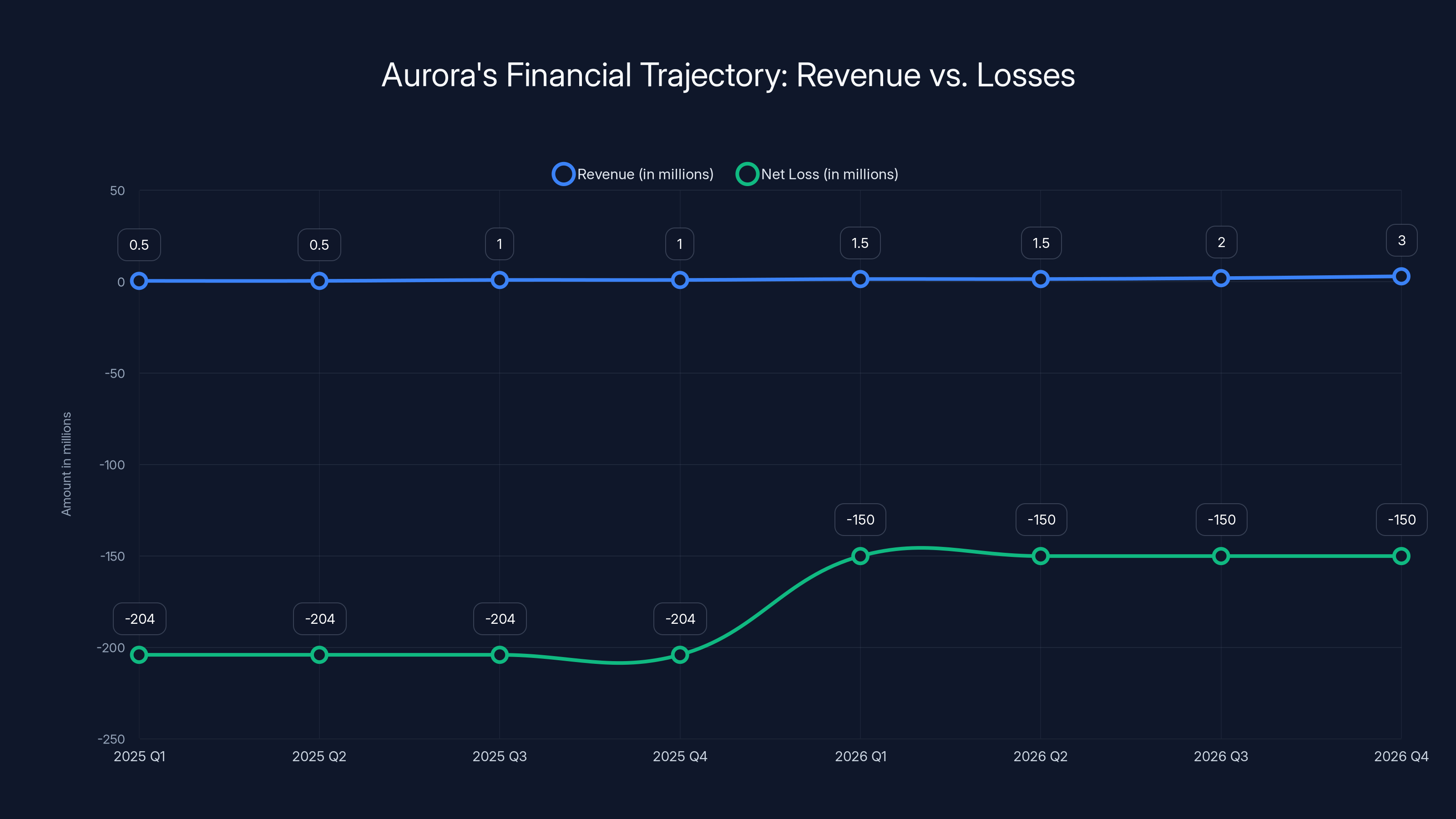

Aurora's revenue is projected to triple by the end of 2026 with the scaling of their truck fleet, while losses are expected to decrease as operations become more efficient. Estimated data.

Competition and the Autonomous Trucking Landscape

Aurora isn't alone. That's worth understanding clearly.

Waymo Via, Google's autonomous trucking subsidiary, has been running limited operations in California and Arizona for a few years. They're being more cautious about scale, which might be smart or might be slow depending on your perspective. Tu Simple, once a major autonomous trucking player, essentially collapsed. Their CEO resigned amid accounting irregularities and the company is in a drawn-out fight for survival. That's instructive: being in this space is genuinely hard.

Tesla is promising autonomous trucking through the Cybertruck, but that's more of a future roadmap than a current reality. Volvo, Daimler, and other legacy truck manufacturers have autonomous programs, but they're cautious about cannibalizing their existing business model (which depends on trained drivers buying trucks).

That makes Aurora's current position interesting. They're essentially the most advanced commercial autonomous trucking operator right now. They have revenue. They have expansion plans. They have major logistics partners. They're not the only company in the race, but they might be winning right now.

The competitive dynamics are also worth noting. As Aurora scales, they become a threat to trucking companies' driver recruitment and retention. Long-haul trucking is brutal work with high turnover. An autonomous alternative is genuinely attractive to logistics operators even if it disrupts their workforce. That creates a coalition of support for Aurora's technology.

The Hardware: International Motors and Next-Generation Sensors

Aurora's current fleet uses Paccar trucks. The company has announced that by Q2 2026, they'll deploy International Motors LT trucks without human observers. That's a significant engineering milestone.

Traditional truck manufacturers are generally conservative. Putting autonomous systems in their trucks without human safety operators means they're vouching for the technology. That endorsement matters. It suggests International Motors has confidence in Aurora's system, or at least is willing to stake their reputation on it.

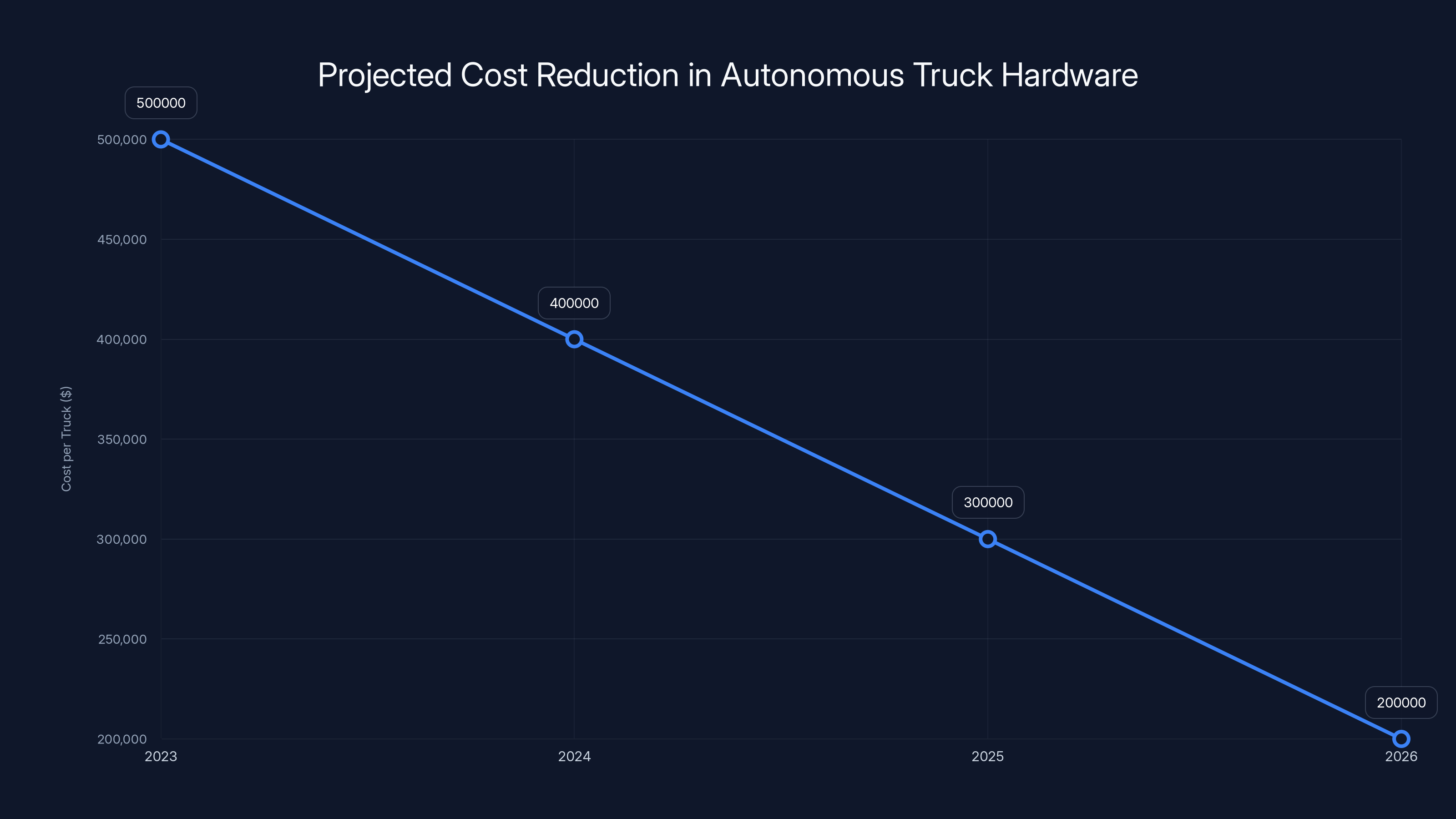

The hardware story is also important for cost structure. Aurora has announced that a second-generation hardware kit is in development. Current hardware uses premium sensors and computing equipment that's expensive. Second-generation hardware should reduce costs while maintaining or improving performance. That's the trajectory needed for economics to work at scale. You can't build a

The company hasn't released detailed specs on the second-generation kit, but the implication is clear: sensor costs will go down, processing power will increase, and integration will improve. This mirrors the trajectory of other autonomous vehicle companies. Early systems are expensive. Mature systems are cheap.

Estimated data shows a significant reduction in hardware costs per truck from

The Workforce Question: What About Truck Drivers?

Let's be direct about the uncomfortable part of this story.

There are roughly 3.5 million truck drivers in the United States. They're predominantly male, geographically distributed, and have limited alternative career options in many regions. Aurora's technology, if it scales to even a fraction of the trucking market, disrupts those 3.5 million jobs.

That's not a reason to stop the technology. Technological displacement is inevitable and historically, new technologies create new jobs while displacing others. But it's a real social question that logistics companies, policymakers, and society need to grapple with.

The timeline matters. Aurora is currently at 30 trucks. Even at 200 trucks by year-end 2026, they're replacing maybe 0.005% of the trucking workforce. There's time to adapt. But if the technology works and scales to 10,000 trucks over the next five years, suddenly you're talking about real economic disruption in a specific geographic region and demographic category.

Drivers who specialize in long-haul freight between major hubs are most at risk. Drivers who handle local delivery, complex docking situations, or tricky urban navigation are safer for longer. The transition might be measured in decades rather than years, but it's coming.

Software Innovation: The Fourth Release and Ongoing Development

Aurora's software roadmap is worth tracking because it reveals how the company is addressing new challenges.

The first software release validated basic driverless operations. The second added nighttime driving capability. That's non-trivial. Night driving removes one of the human brain's key advantages: visual processing of color and texture. Autonomous systems see the world differently than humans, and seeing it well at night requires different sensor configuration and processing approaches.

The third release added El Paso operations. El Paso introduces different challenges than Dallas-Houston or Fort Worth. Desert climate. Different road conditions. Longer stretches between populated areas. The software had to adapt.

The fourth release, which enables the full 1,000-mile Fort Worth-to-Phoenix operation, essentially represents solving the geographic diversity problem. Once you can handle the variation from Fort Worth to Phoenix, you've solved a significant portion of the general autonomous trucking problem.

What's not explicitly stated but is implied: each software release involved retraining the underlying neural networks on new data. Aurora presumably drove thousands of miles manually or manually supervised on each new route, collecting data, validating that data, retraining, and then gradually reducing human supervision. That's how modern autonomous systems work. It's not programming rules. It's training systems to recognize patterns.

The company has committed to continuous improvement. The next software releases will presumably add capabilities like adverse weather handling, more complex traffic scenarios, or expanded geographic regions. The trajectory suggests accelerating capability improvements as they gather more data.

Aurora's driverless trucks are projected to increase their mileage and fleet size significantly from 2025 to 2028, highlighting rapid growth in autonomous logistics. Estimated data.

The Financial Reality: Revenue, Losses, and the Path to Profitability

Here's the raw financial picture because it matters.

Aurora generated

That's a staggering loss-to-revenue ratio. But it's not incoherent. The company has spent years building technology that didn't generate revenue. Now they're beginning to monetize. The losses reflect years of R&D, regulatory navigation, hardware development, and pilot programs.

The key financial question is trajectory. Aurora needs to demonstrate that as the fleet scales, revenue scales faster than losses shrink. The company has approximately 200+ trucks coming by year-end 2026. If even 100 of those trucks are generating revenue at the same rate as current operations, revenue would roughly triple. That's movement in the right direction.

For comparison, Lyft and Uber both operated at massive losses for years before scaling. The difference here is that Aurora's unit economics—the profit per truck per mile—need to work eventually. If they don't, it's a failed business model no matter how much venture capital you throw at it.

The company went public via SPAC in early 2024, which provided capital for this scaling phase. As of early 2026, they still have resources to scale operations. The question is whether they can reach profitability before those resources deplete significantly.

Market Reception: Who's Actually Buying?

The most important validation isn't internal metrics. It's that actual logistics companies have signed up.

Uber Freight, which is Uber's logistics subsidiary, is a customer. Uber doesn't make casual technology bets. They're deploying the technology because they believe it works and has economic value. Werner is one of the largest trucking companies in the country. Fed Ex and Schneider are also signing up. These are companies with decades of experience evaluating trucking operations.

Hirschbach, mentioned specifically as an early customer on the Fort Worth-to-Phoenix route, apparently believes the economics work. They're betting their operations on Aurora's trucks for that corridor.

That customer adoption pattern is more important than any benchmarking claim Aurora could make. These companies have money on the line. They'd stop using the service if it didn't deliver value or created problems.

Aurora's fleet is projected to grow to over 200 trucks by 2026, with market penetration in the Sun Belt reaching 50%. Estimated data based on current trends.

The Geographic Limitation: Why Sun Belt, Why Now

Understanding Aurora's limitations is as important as understanding their advantages.

They're not operating in Chicago. They're not crossing into Minnesota, Wisconsin, or the Pacific Northwest. They're not tackling mountains or heavy snow. That's partly strategic (dominate one region first) and partly technical (autonomous systems struggle in snow and ice).

Snow and ice are particularly problematic because they obscure lane markings, which cameras rely on. They reduce sensor effectiveness by blocking light. They change road physics, making prediction harder. Winter weather is generally harder for autonomous systems.

Aurora's strategy of dominating the Sun Belt first is smart because it maximizes the probability of success in a region where the technology works well, customers are located, and expansion is geographically natural. It's also smart because weather volatility could undermine their safety record. Stay in predictable climates, build an unassailable safety record, then expand to harder climates from a position of strength.

The limitation is real though. The Sun Belt is important for logistics, but it's not the entirety of the US trucking market. Eventually, if autonomous trucking is the future, it has to work in Minnesota winters too. Aurora either solves that problem or accepts a regional limitation.

The Regulatory Wild Card: Federal Guidance and Safety Standards

Here's an area where Aurora is advantaged by a current vacuum.

There's no explicit federal regulation for autonomous trucks. The Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration (FMCSA) hasn't issued specific guidelines. That creates regulatory flexibility. Companies can innovate faster. But it also creates risk. A catastrophic accident involving an Aurora truck could trigger knee-jerk federal regulation that's poorly informed.

Aurora is being smart about this by maintaining a safety record and working cooperatively with regulators rather than antagonistically. They're voluntarily implementing standards even without mandates. They're being transparent about operations. That's the right playbook for a company navigating regulatory uncertainty.

The state-level permitting Aurora has received from Arizona, Texas, and other states suggests regulators are comfortable enough with the technology. But federal regulation is coming eventually. The question is whether it'll be designed thoughtfully with industry input or hastily after a disaster.

Aurora's track record of safety is essentially their insurance policy against heavy-handed regulation. If they can maintain a perfect or near-perfect safety record while scaling operations, federal regulators will have a hard time imposing restrictive rules.

The Vision: 2026 and Beyond

Urmson stated clearly that Aurora expects 2026 to be the year the market recognizes that autonomous trucks have arrived. If you live in the Sun Belt in 2026, you'll reportedly see Aurora trucks regularly on the highways.

That's a bold prediction, but it's more credible now than it would have been a year ago. The company has revenue. They have customers. They have an expanding fleet. They have demonstrated capability on a 1,000-mile route.

What happens next depends on a few variables. Do the trucks continue to maintain a strong safety record? Does the fleet expansion to 200+ trucks proceed on schedule? Do additional customers sign up? Does the expansion into other Sun Belt states execute smoothly? Can the economics remain favorable as labor costs and fuel costs fluctuate?

Optimistically, Aurora becomes the dominant force in long-haul autonomous trucking in the Sun Belt and gradually expands nationally. Pessimistically, they hit unforeseen technical or business challenges that slow growth.

The most likely scenario is probably middle ground. Aurora succeeds in their core market but takes longer to expand nationally than they're currently projecting. They face some unexpected challenges (maybe a serious accident, maybe sensor issues in unexpected weather) but ultimately overcome them. They reach profitability slower than investors hoped but eventually do.

Impact on Logistics and Supply Chains

If autonomous trucking scales, the implications for supply chains are profound.

First, velocity. Faster transit times mean inventory spends less time in motion. For perishable goods, that's a quality improvement. For time-sensitive manufacturing, that's a competitiveness improvement. Supply chain optimization improves when the cost of transportation decreases and the speed increases.

Second, reliability. Autonomous systems don't have driver variability. They don't get sick. They don't have scheduling conflicts. This creates more predictable supply chains, which lets companies optimize inventory and production planning.

Third, cost structure. Fewer drivers means lower labor costs per shipment. That gets passed along as either cheaper goods for consumers or higher margins for logistics companies. In a competitive market, it's probably some of both.

Fourth, geographic expansion. With lower operational costs, logistics companies can justify operations on lower-volume routes that weren't previously economical. That extends logistics network breadth.

The cumulative effect is a structural change in how goods move through the economy. It's not necessarily disruptive overnight, but it's meaningful over 5-10 years.

The Technology Maturity Question

There's a difference between "capability demonstrated on controlled routes" and "production-ready for any highway, any condition." Aurora has demonstrated the former. They're working toward the latter.

The fact that they can handle a 1,000-mile route in 15 hours is genuinely impressive. But that route is still a controlled scenario. Specific highways. Known geographic variation. Established demand. In some ways, it's still a pilot program, just a larger one than before.

Moving to true production-ready status requires solving edge cases. What happens in heavy rain? In fog? In unexpected road conditions? With unusual traffic patterns? When something genuinely surprising happens?

Aurora's fourth software release supposedly handles "diverse geography and climate of the southern United States." That's vague. The southern US doesn't include severe winter. It includes common weather patterns and reasonable road conditions. The question is how the system handles the 5% of scenarios that are genuinely weird.

That's where the next phase of validation happens. Not in controlled press releases, but in months and years of real-world operation where everything that can go wrong occasionally does.

The Broader Autonomous Vehicle Narrative

Aurora's success is also interesting in the context of autonomous vehicles more broadly.

The consumer autonomous vehicle narrative has been about robotaxis and robo-shuttles. Waymo, Tesla, Cruise (before it stumbled), and others have been chasing the passenger vehicle market. That's harder than everyone thought. City driving is complicated. Edge cases proliferate. Liability is messy. Regulations are uncertain.

But freight trucking? It's actually simpler in many ways. Trucks follow highways. Customers care about cost and reliability, not comfort. There's no passenger liability. The economics are straightforward. It turns out that solving autonomous transportation for cargo might be easier than solving it for people.

That's a useful corrective to the breathless hype about full autonomous vehicle fleets in major cities. Maybe the near-term impact of autonomous vehicles isn't robotaxis. Maybe it's trucks.

Long-Term Implications: The 2030-2035 Vision

Assuming Aurora and similar companies continue to make progress, what does the freight landscape look like in 2030-2035?

Probably a hybrid. Human-driven trucks still dominate, but autonomous trucks are a significant fraction, especially on high-value, high-volume corridors. The Southwest Corridor (Aurora's current focus area) is maybe 30-40% autonomous by 2030. Rest of the country is maybe 5-10% autonomous. The technology works, but it hasn't displaced human drivers everywhere yet.

Driver salaries probably adjust. Long-haul driving becomes less common and less economical. Local delivery and complex driving stays human-operated. Drivers who adapt transition to roles where human judgment and dexterity matter.

Regulation probably stabilizes. The FMCSA probably issues autonomous trucking guidelines based on accumulated experience with Aurora, Waymo, and others. Safety standards probably get defined. Insurance probably gets clearer.

Costs and transit times probably improve noticeably. Supply chains get incrementally more efficient. Goods move faster, cheaper, and more reliably.

The S-curve of adoption probably continues. Early adoption (2025-2027) is fast. Scale adoption (2027-2033) accelerates. Maturity (2033+) plateaus when basically all economically viable operations are autonomous.

FAQ

What is Aurora's autonomous trucking system?

Aurora's autonomous trucking system is an AI-powered solution that enables semi-trucks to operate without human drivers on designated highway routes. The system uses sensors (LIDAR, cameras, and radar), real-time environmental mapping, and neural network-based decision-making to navigate, detect obstacles, and respond to traffic conditions. As of early 2026, Aurora's system operates commercial routes primarily in the Southwest US, with the most notable achievement being the ability to transport freight 1,000 miles between Fort Worth and Phoenix in approximately 15 hours.

How does Aurora's technology actually work in practice?

Aurora's trucks use multiple sensor types working in parallel. LIDAR creates a detailed three-dimensional map of the environment, cameras provide color and texture information, and radar detects moving objects at distance. The system processes this sensor data through trained neural networks that make real-time decisions about acceleration, braking, steering, and lane changes. The software has been developed incrementally, with each new software release adding capabilities (first release: daytime highway driving; second release: nighttime operation; third release: geographic diversity; fourth release: full Sun Belt climate handling). Currently, Paccar trucks have human safety observers, but upcoming International Motors LT deployments will operate without humans on board.

What are the economic advantages of autonomous trucking?

Autonomous trucks offer significant economic benefits compared to traditional human-driven operation. Human truck drivers cost companies

Why is the Sun Belt the focus of Aurora's operations?

Aurora strategically chose the Sun Belt region (Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, and planned expansion to Oklahoma, Louisiana, Florida, etc.) because of several technical and commercial advantages. The region has minimal winter weather, meaning no snow or ice that obscures lane markings and degrades sensor performance. The highways are well-maintained and well-mapped. The region contains major logistics hubs (Dallas, Houston, Phoenix) that generate substantial freight demand on specific high-value corridors. The climate predictability allows Aurora to build and validate their system without the additional complexity of winter weather edge cases. This geographic focus enables them to maximize success probability in a defined region before expanding to more challenging environments.

How many driverless miles has Aurora logged, and what's the safety record?

As of January 2026, Aurora's autonomous trucks had completed 250,000 driverless miles with a reported perfect safety record (zero accidents or incidents). For comparison, modern human truck drivers average approximately one accident per 500,000 miles, so the current safety data is promising but not yet statistically conclusive over the long term. However, the zero-incident record across 250,000 miles without fatigue-related incidents (fatigue being a leading cause of truck accidents) represents meaningful validation. The company's approach emphasizes controlled expansion and careful validation of each new capability before scaling, which contributes to the demonstrated safety performance.

What's the revenue outlook for Aurora's autonomous trucking operations?

Aurora generated

What's the timeline for fully driverless operations without safety observers?

Aurora announced that by Q2 2026, they plan to deploy International Motors LT trucks that will operate completely without human safety observers on board. This is a significant milestone because current operations use Paccar trucks with human observers in the cab. The transition to fully autonomous operation demonstrates confidence in the technology's readiness for unsupervised operation. The company's expansion plans involve gradually converting more of their fleet to fully autonomous operation while maintaining their perfect safety record. This phased approach—maintaining observers initially, then removing them as confidence increases—represents standard practice in autonomous system deployment.

How do regulatory frameworks affect Aurora's operations?

Currently, there is no explicit federal regulation specifically governing autonomous trucking operations. This regulatory vacuum provides both advantages and risks. On one hand, Aurora can innovate faster without heavy-handed compliance burdens. On the other hand, a serious accident could trigger restrictive federal regulation before best practices are established. Aurora has navigated this by obtaining state-level permits from Arizona, Texas, and other states; maintaining exemplary safety records that pre-empt regulatory concerns; and cooperating with regulators rather than operating antagonistically. The Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration (FMCSA) has not yet issued specific guidelines for autonomous trucks, though such guidance is expected as the technology matures and becomes more prevalent.

What are the implications for truck drivers and the trucking workforce?

Autonomous trucking poses genuine disruption risk to the 3.5 million truck drivers in the US, particularly those focused on long-haul freight between major hubs. However, the timeline is measured and displacement is likely to be gradual. Aurora's current 30-truck fleet represents negligible workforce impact. Even at 200 trucks by year-end 2026, they're affecting less than 0.01% of the trucking workforce. The real disruption happens if technology scales to thousands of vehicles over 5-10 years. Long-haul drivers are most at risk, while drivers handling local delivery, complex docking, and urban navigation face lower displacement risk. The transition likely plays out over decades, providing time for workforce adaptation, retraining, and natural attrition as drivers retire.

How will autonomous trucking affect supply chains and logistics costs?

Autonomous trucking promises multiple supply chain improvements if Aurora and similar companies scale successfully. First, faster transit times (potentially 50% reduction) improve inventory velocity and reduce working capital requirements for logistics-dependent industries. Second, 24/7 autonomous operation improves supply chain predictability and reliability. Third, reduced labor costs lower overall transportation expense, which either translates to cheaper goods for consumers or improved margins for logistics companies. Fourth, improved economics enable operations on lower-volume routes previously uneconomical with human drivers. Cumulatively, these changes create more efficient, faster, and cheaper supply chains, with meaningful structural impacts over 5-10 years.

Key Takeaways

- Aurora's autonomous trucks travel 1,000 miles in 15 hours, faster than federal regulations allow human drivers (11-hour limit plus mandatory rest)

- The company achieved revenue generation in 2025 with major customers (Uber Freight, FedEx, Werner, Schneider) validating commercial viability

- Aurora's perfect safety record across 250,000 driverless miles exceeds human driver accident rates, though sample size remains limited

- Sun Belt geographic focus (Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, expanding to Oklahoma, Louisiana, Florida) leverages predictable climate for maximum reliability

- Fleet expansion from 30 trucks to 200+ by year-end 2026 enables revenue scaling; Q2 2026 transition to fully autonomous operation removes human observers

- Economic advantage for logistics companies is substantial: eliminates $60K-80K annual driver costs, enables 24/7 operation, potentially cuts transit times 50%

- Long-haul truck drivers face medium-term disruption risk, but timeline is gradual; near-term impact is negligible at current fleet scale

Related Articles

- Aurora Triples Driverless Truck Network: The Future of Autonomous Logistics [2025]

- Waymo's Sixth-Generation Robotaxi: The Future of Autonomous Vehicles [2025]

- Waymo's Fully Driverless Vehicles in Nashville: What It Means [2025]

- Waymo's Nashville Robotaxis: The Future of Autonomous Mobility [2025]

- Waymo's Genie 3 World Model Transforms Autonomous Driving [2025]

- How Waymo Uses AI Simulation to Handle Tornadoes, Elephants, and Edge Cases [2025]

![Aurora's Driverless Trucks: The Superhuman Era of Autonomous Freight [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/aurora-s-driverless-trucks-the-superhuman-era-of-autonomous-/image-1-1770919620489.jpg)