AWS Code Build Supply Chain Vulnerability: The Critical "Code Breach" Incident That Nearly Broke the Internet

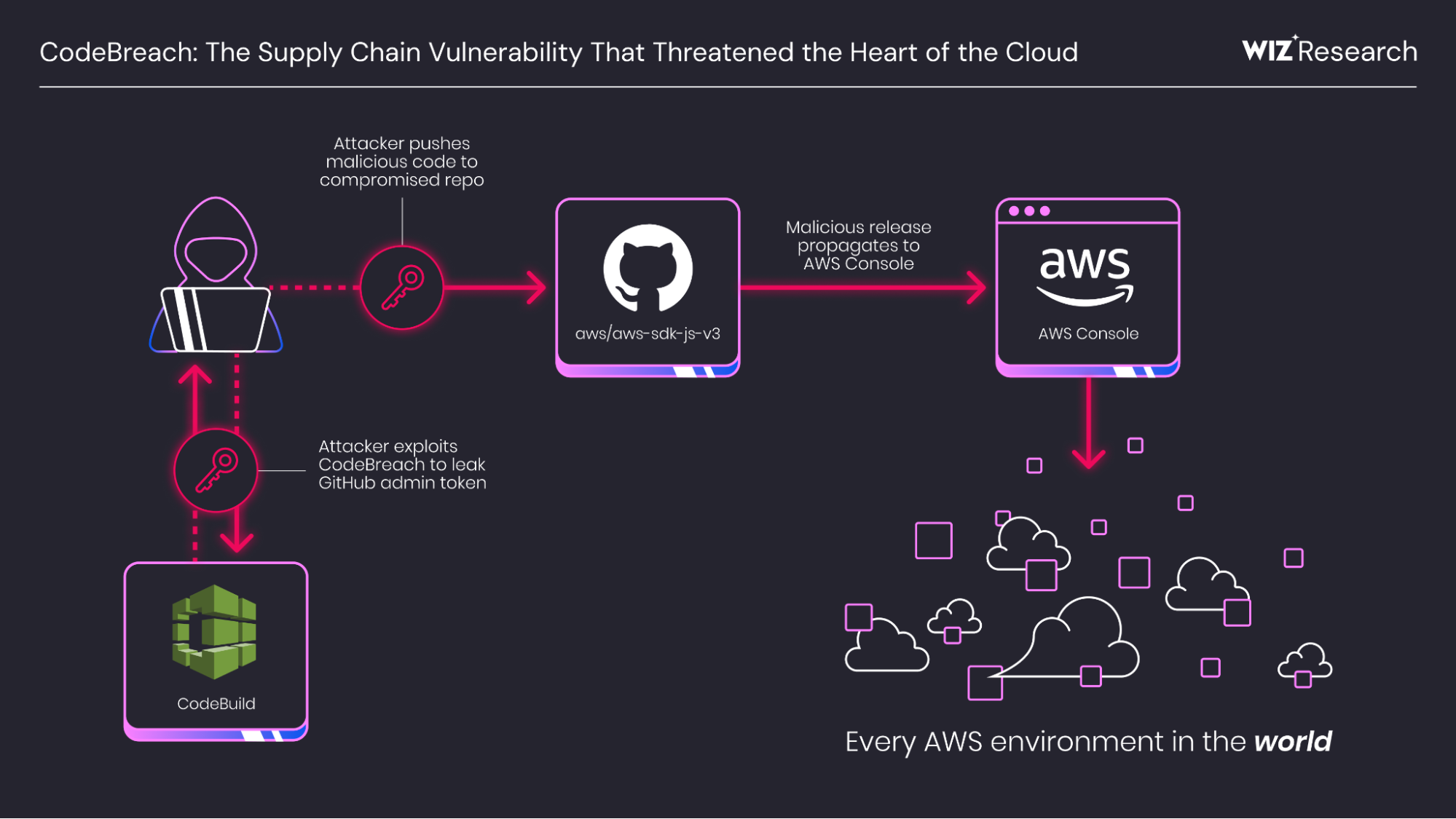

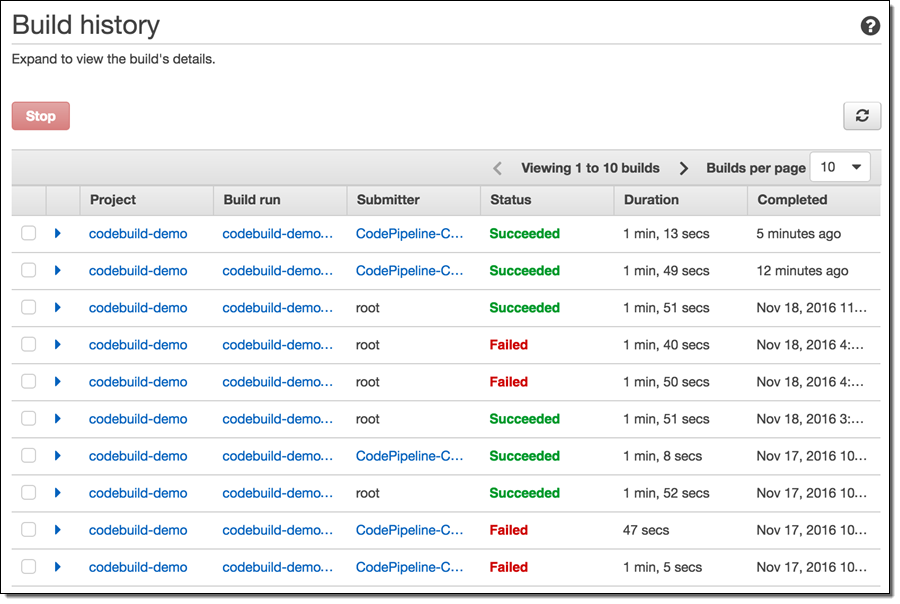

Something genuinely scary happened in the AWS ecosystem in August 2025, and most people didn't notice. Security researchers at Wiz discovered a critical misconfiguration in AWS Code Build that could have allowed attackers to hijack some of the most important GitHub repositories on the planet. They're calling it "Code Breach," and honestly, the implications still give me chills when I think about what could have happened.

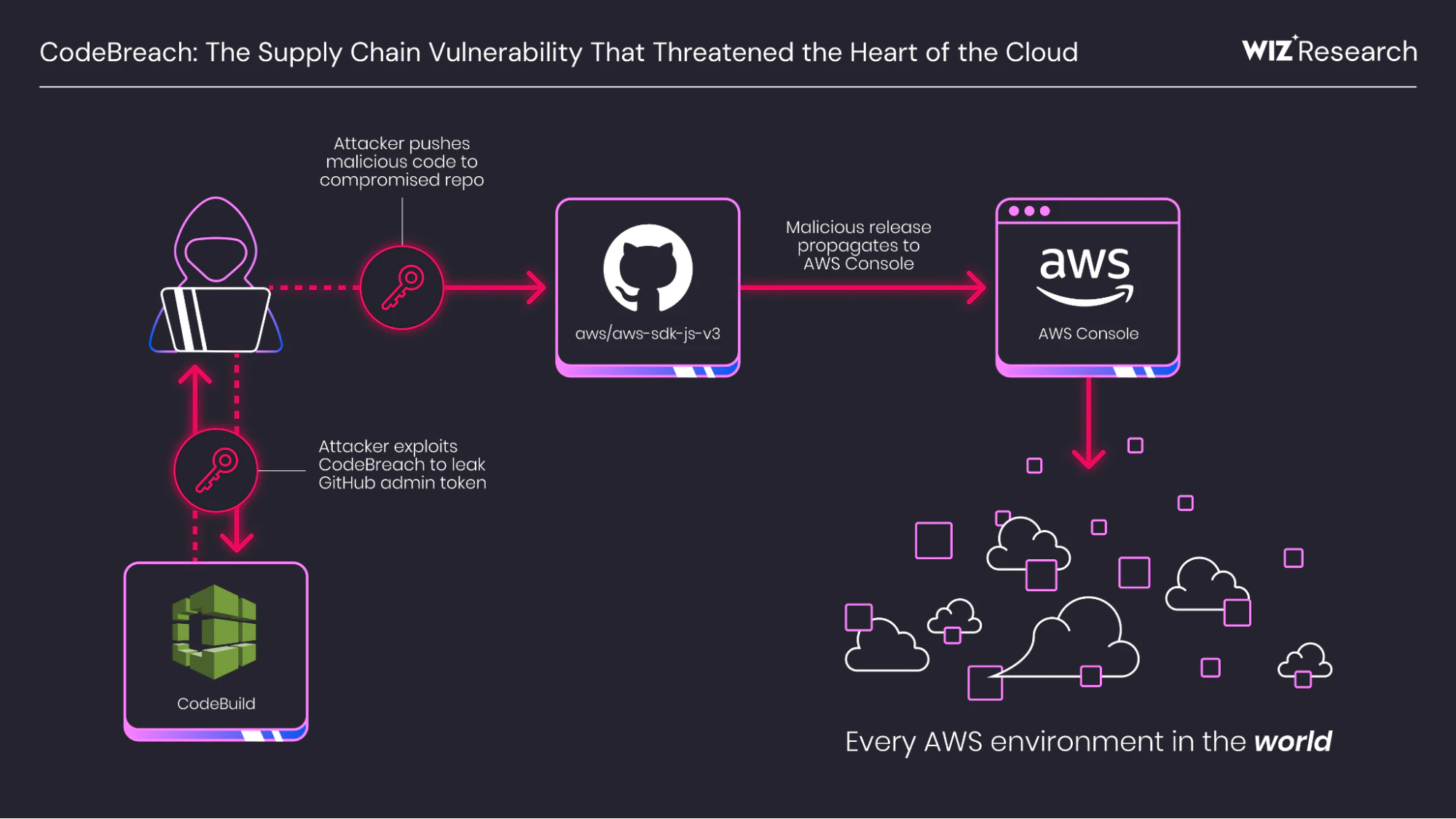

Imagine this: an attacker gains access to GitHub tokens stored in AWS build environments. From there, they can push malicious code to core AWS repositories. That code gets merged into production. Suddenly, AWS customers worldwide are downloading backdoored software without knowing it. The supply chain attack would ripple across the entire tech industry.

That's not hypothetical. That was possible under this vulnerability.

Here's what makes this different from your typical security flaw. This wasn't some edge case vulnerability buried in obscure code. This was a fundamental misconfiguration in how AWS Code Build validated user permissions. The scary part? AWS fixed it within 48 hours of disclosure, but only because Wiz caught it first. There's no evidence anyone else exploited it, but that doesn't mean attackers weren't looking.

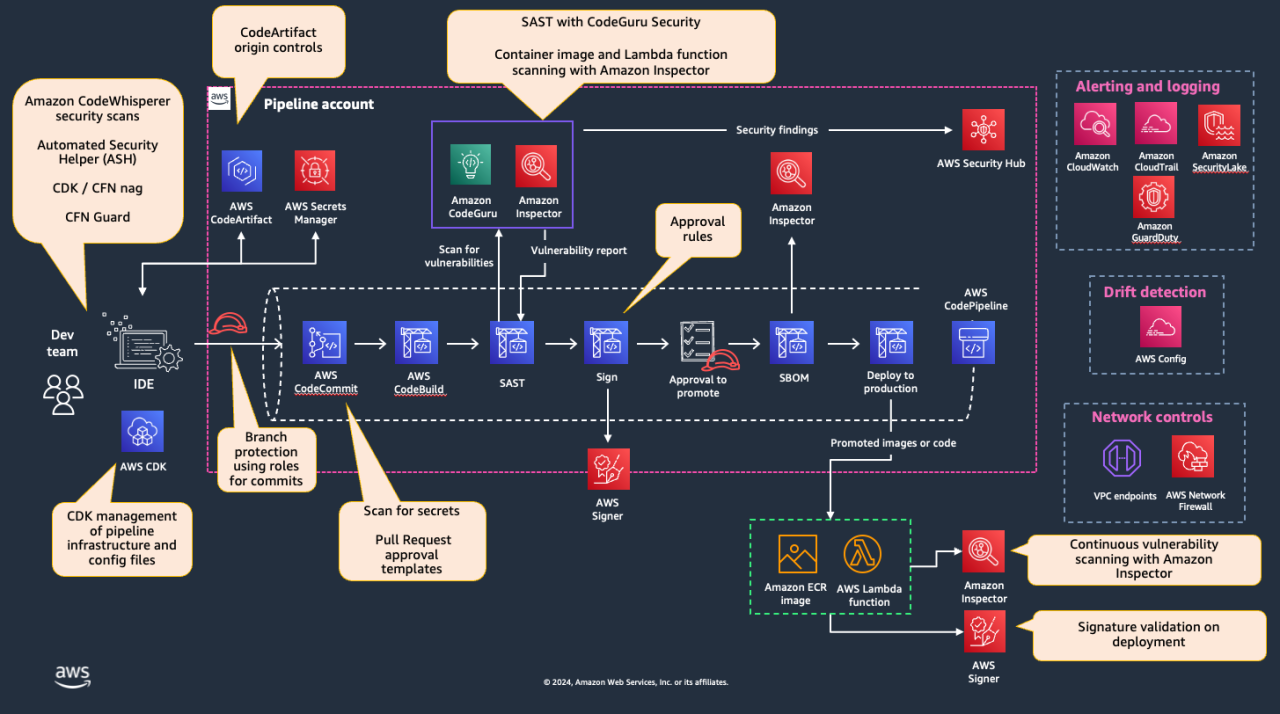

In this deep dive, we'll walk through exactly what Code Breach was, how it worked, why it was so dangerous, what AWS did to fix it, and most importantly, what you need to do right now to protect your own CI/CD pipelines. Because here's the hard truth: the vulnerability existed for a reason, and if you're not auditing your build configurations, you might have similar issues lurking in your own systems.

Let's start with the basics and work our way up to the really scary stuff.

TL; DR

- Code Breach vulnerability: AWS Code Build misconfiguration allowed attackers to bypass user validation and trigger unauthorized privileged builds

- The core flaw: Unanchored regex patterns in webhook filters didn't require exact matches, letting attackers use substring matching to bypass security checks

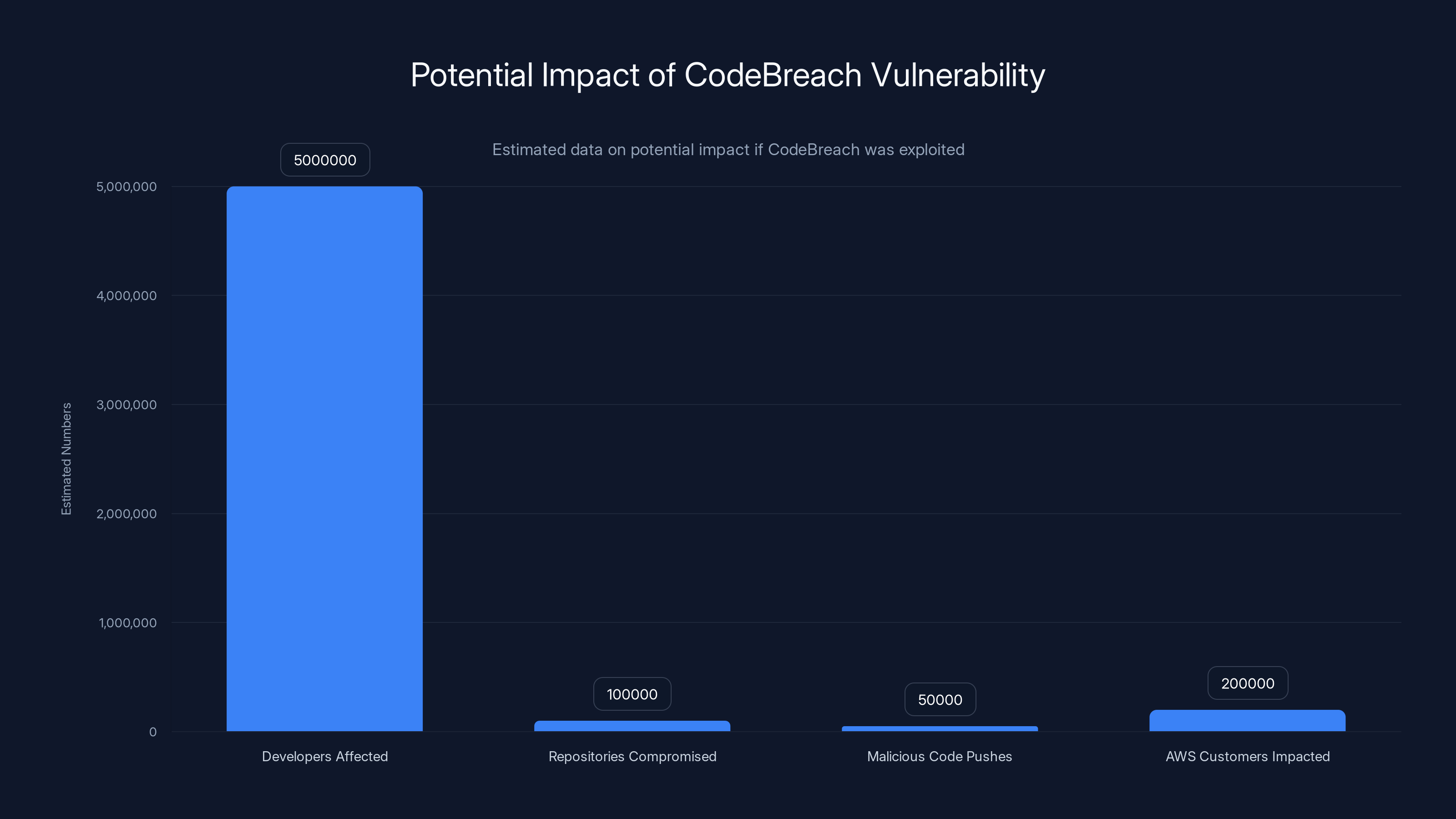

- Potential impact: Attackers could access GitHub tokens in build environments and push malicious code to AWS-managed repositories, creating a platform-wide supply chain attack

- AWS response time: The core issue was mitigated within 48 hours of Wiz's August 2025 disclosure, with no evidence of exploitation

- Your action items: Audit your webhook filters, anchor regex patterns, limit token privileges, and prevent untrusted pull requests from triggering privileged builds

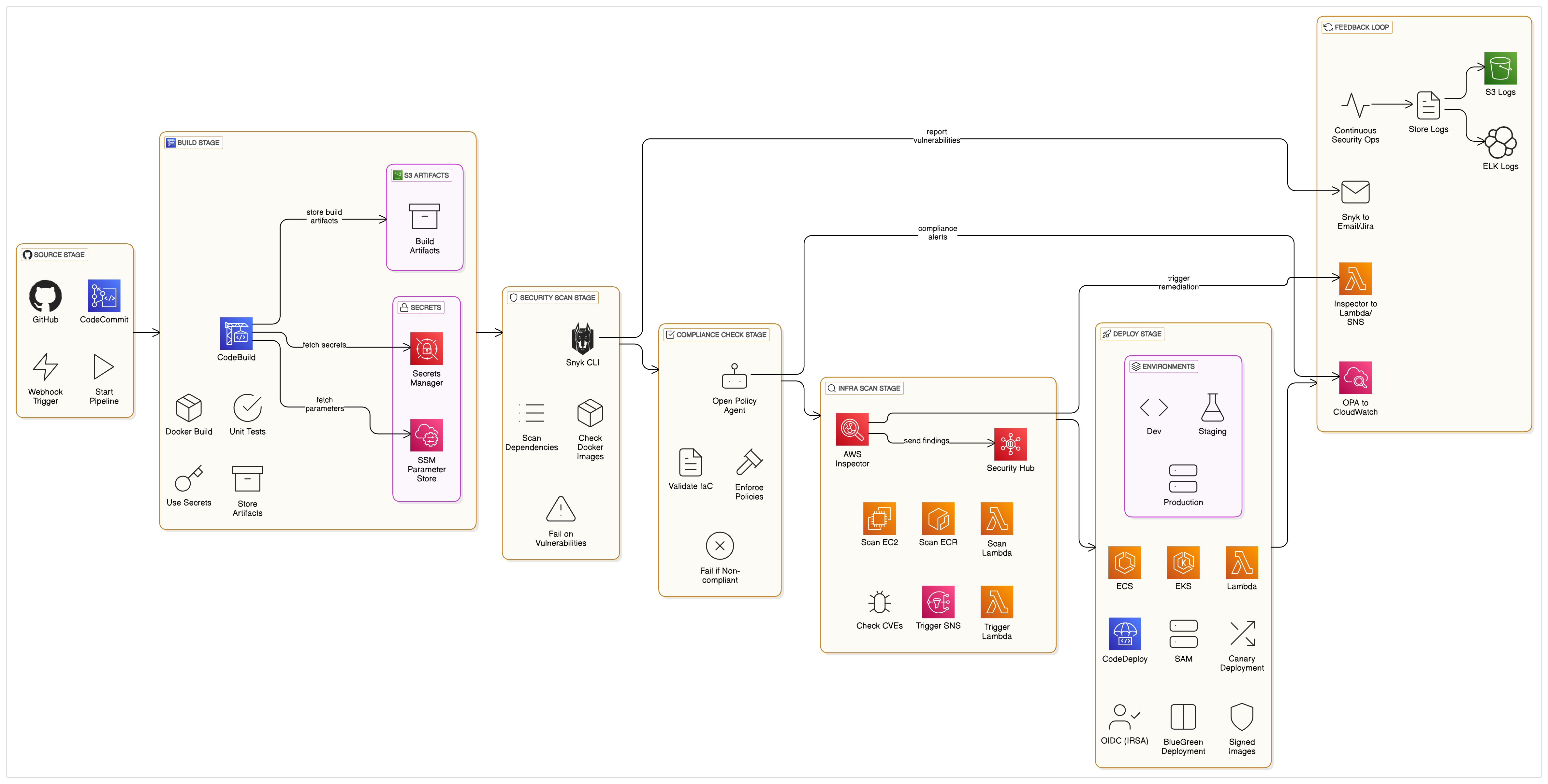

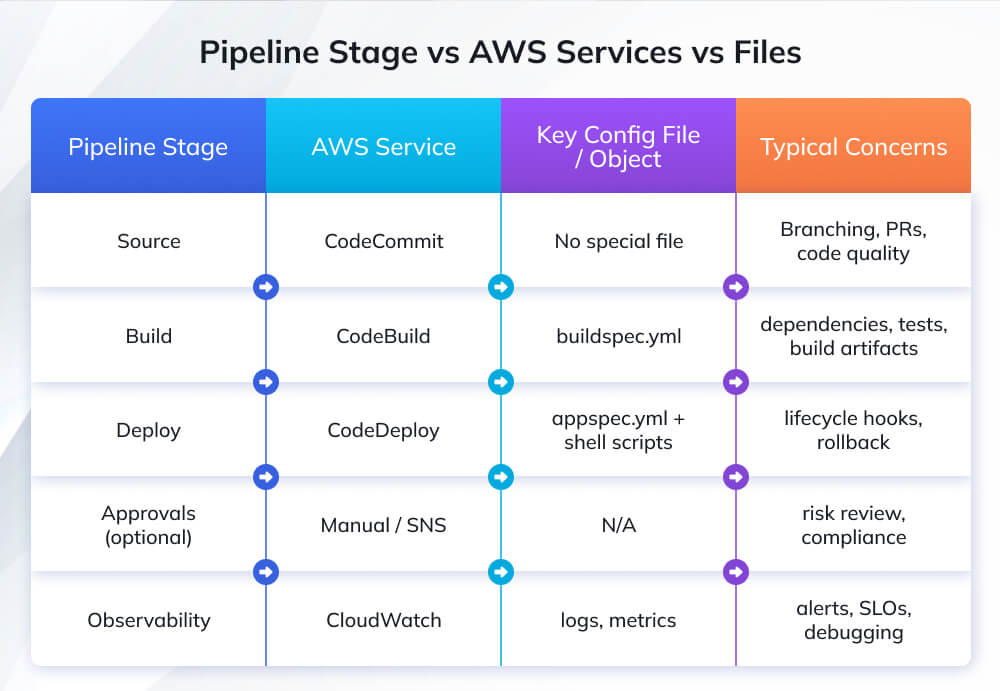

AWS CodeBuild excels in infrastructure management and scalability, with strong security and integration capabilities. Estimated data based on typical service features.

What Is AWS Code Build and Why Does It Matter?

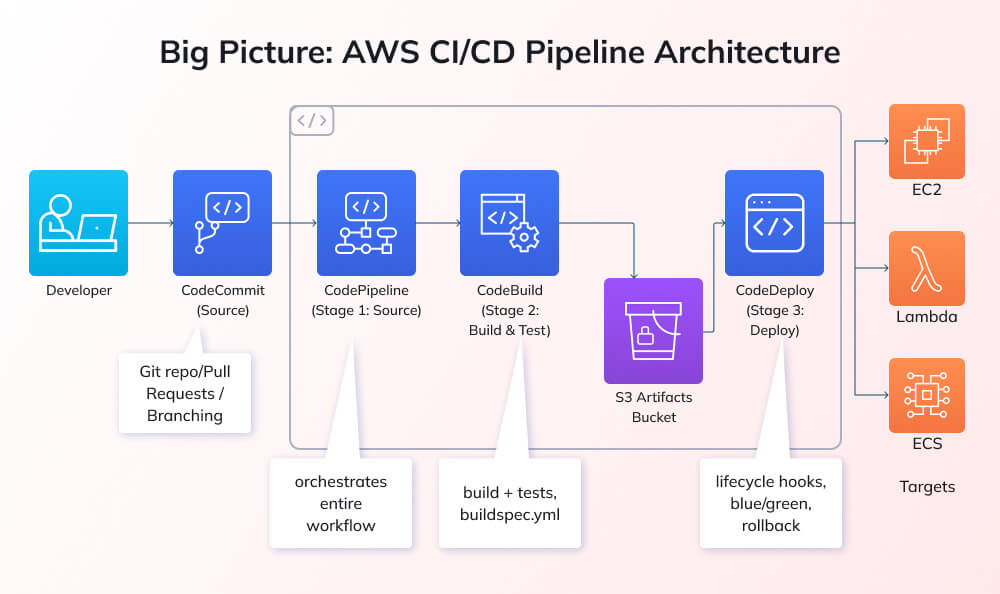

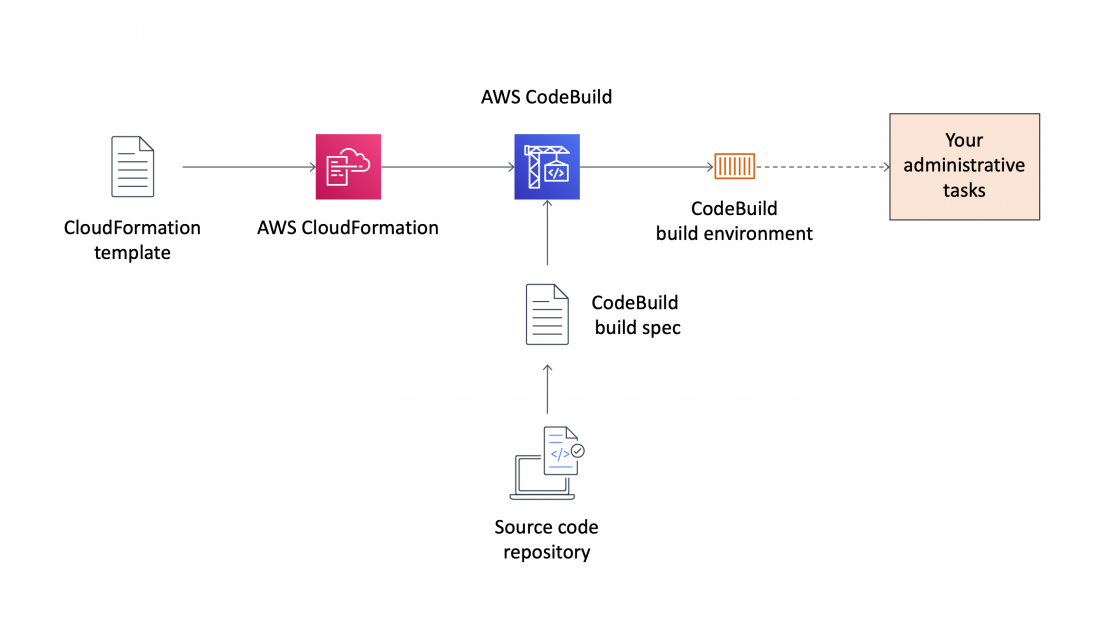

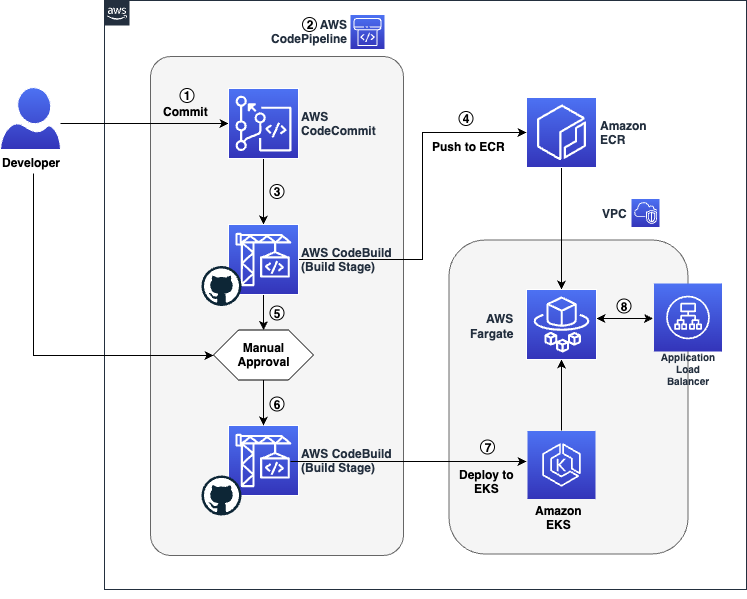

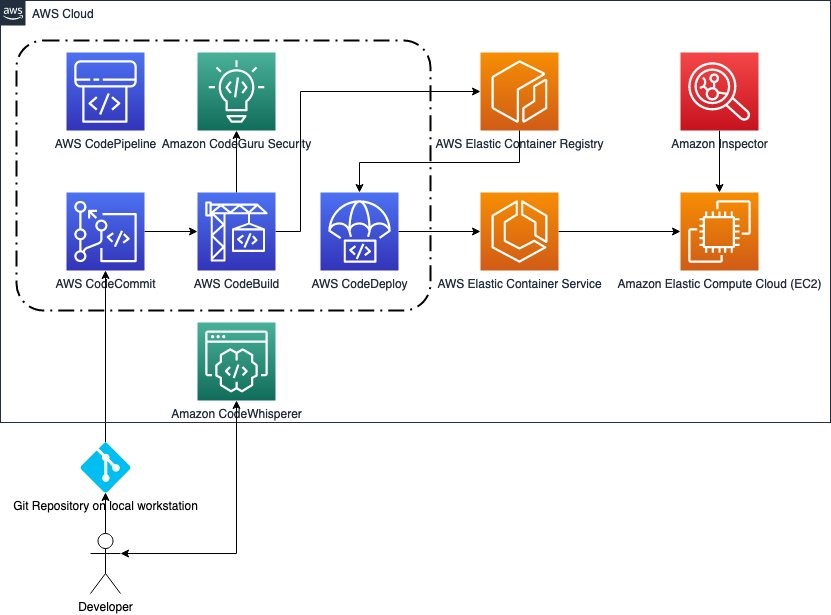

AWS Code Build is one of those services that lives quietly in the background of most modern development workflows. It's a fully managed continuous integration service that automatically compiles, tests, and packages your source code as part of a larger CI/CD pipeline. Think of it as a robot that watches your GitHub repository, grabs the latest code whenever something changes, runs your tests, and handles the build process without you having to touch anything.

The beauty of Code Build is that it handles the infrastructure for you. You don't manage servers. You don't patch operating systems. AWS does all of that. You define your build steps in a simple YAML file, point Code Build at your repository, and it scales automatically based on demand. Want to run 100 builds in parallel? Code Build does it. Need a single build? Code Build handles that too.

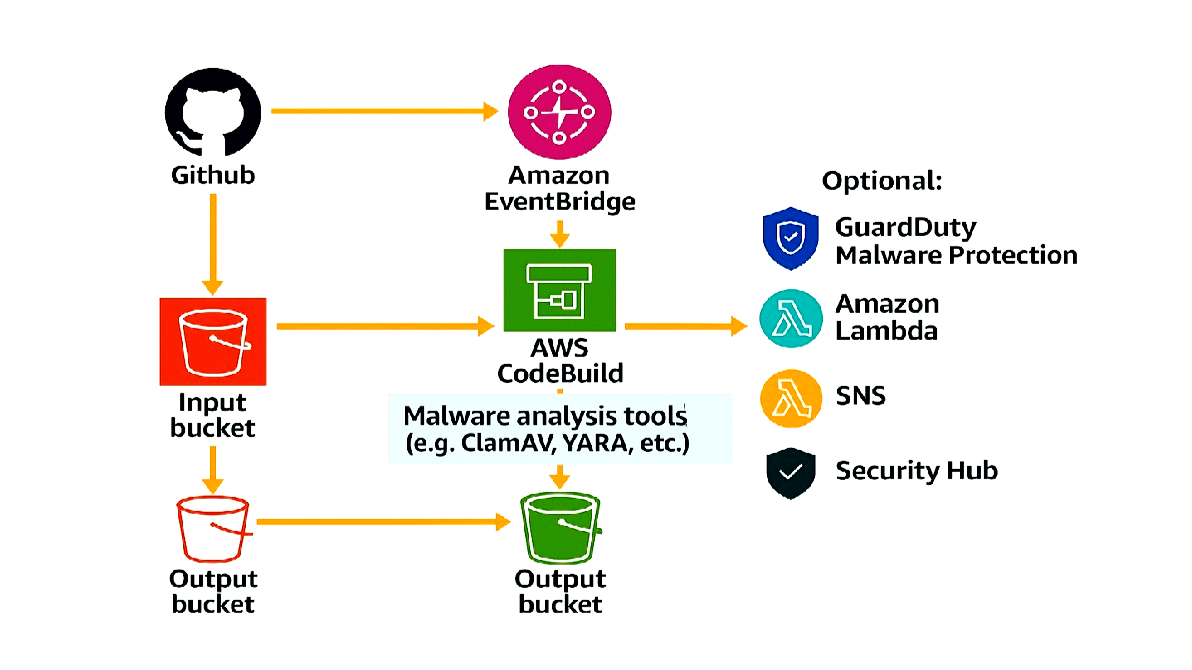

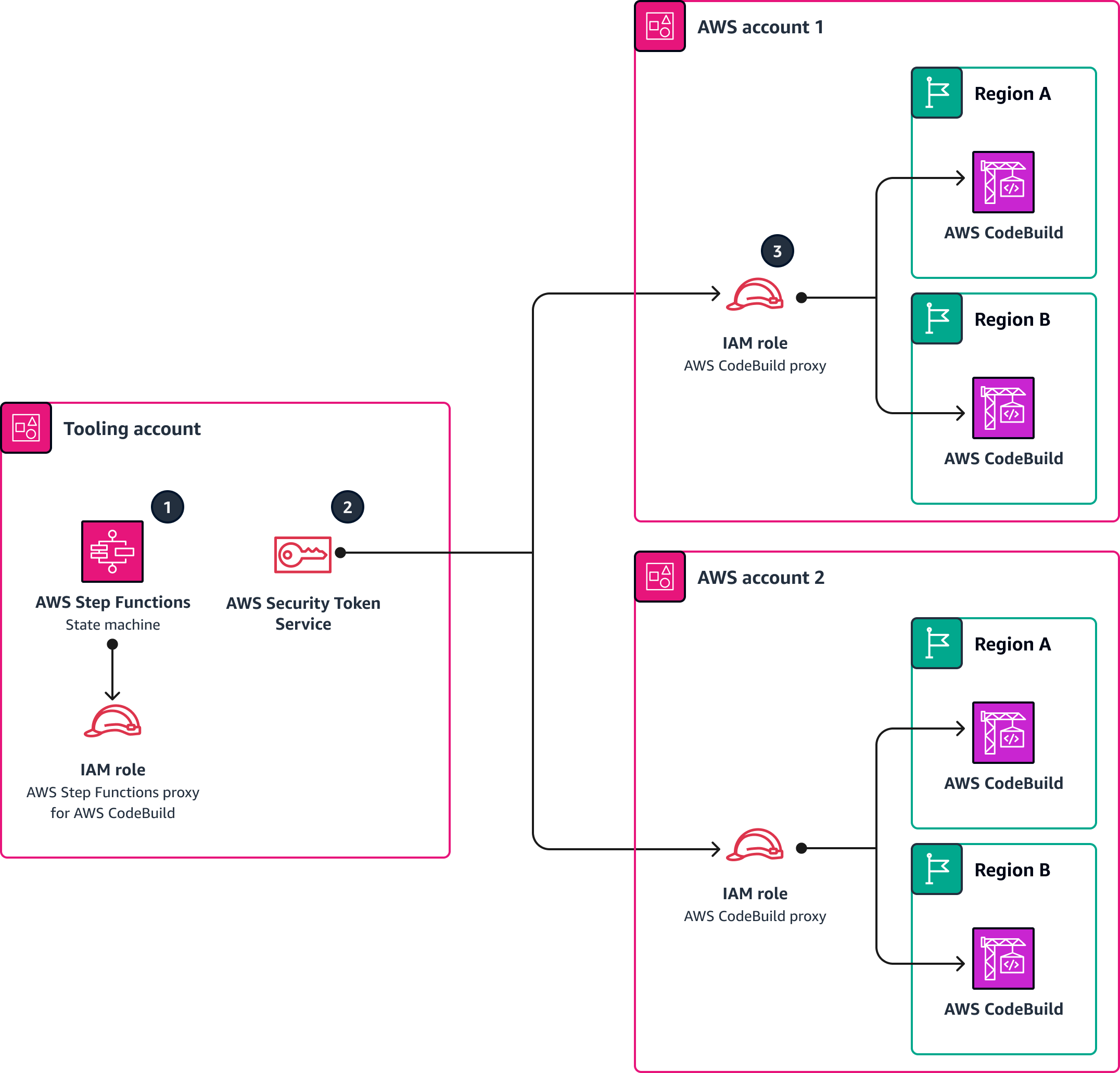

But here's the thing about delegating infrastructure: it creates a trust boundary. Code Build runs in AWS-managed environments, which means it has access to powerful credentials. If you're building an application that needs to deploy to AWS, Code Build can assume IAM roles. If you're publishing to a package registry, Code Build can store API keys. If you're pushing commits back to GitHub, Code Build can use GitHub tokens. All of these credentials are necessary for the build process to work, but they're also incredibly valuable to an attacker.

That's where webhooks come in. GitHub webhooks are how Code Build knows when to run a build. When you push code to a repository or open a pull request, GitHub sends a notification to Code Build saying "Hey, something happened, you might want to build this." Code Build receives that notification and needs to decide: should I actually run this build, and if so, with what permissions?

This decision point is critical. If Code Build always ran builds with full permissions for any change, anyone could fork your repository, open a pull request, and suddenly have access to your AWS credentials. That's why AWS implements validation. Webhooks come with information about who triggered the event, and Code Build checks that against a list of approved users. If you're in the approved list, the build runs. If you're not, it doesn't.

Or at least, that's how it's supposed to work.

The Code Build service is critical infrastructure for AWS itself. AWS uses Code Build to manage its own repositories. This is incredibly important to understand. AWS doesn't just sell Code Build to customers. AWS uses Code Build to maintain AWS. When you're talking about a vulnerability in how Code Build validates permissions, you're talking about something that could potentially impact AWS's own operations. The blast radius of this vulnerability wasn't limited to customer environments. It could have affected AWS itself.

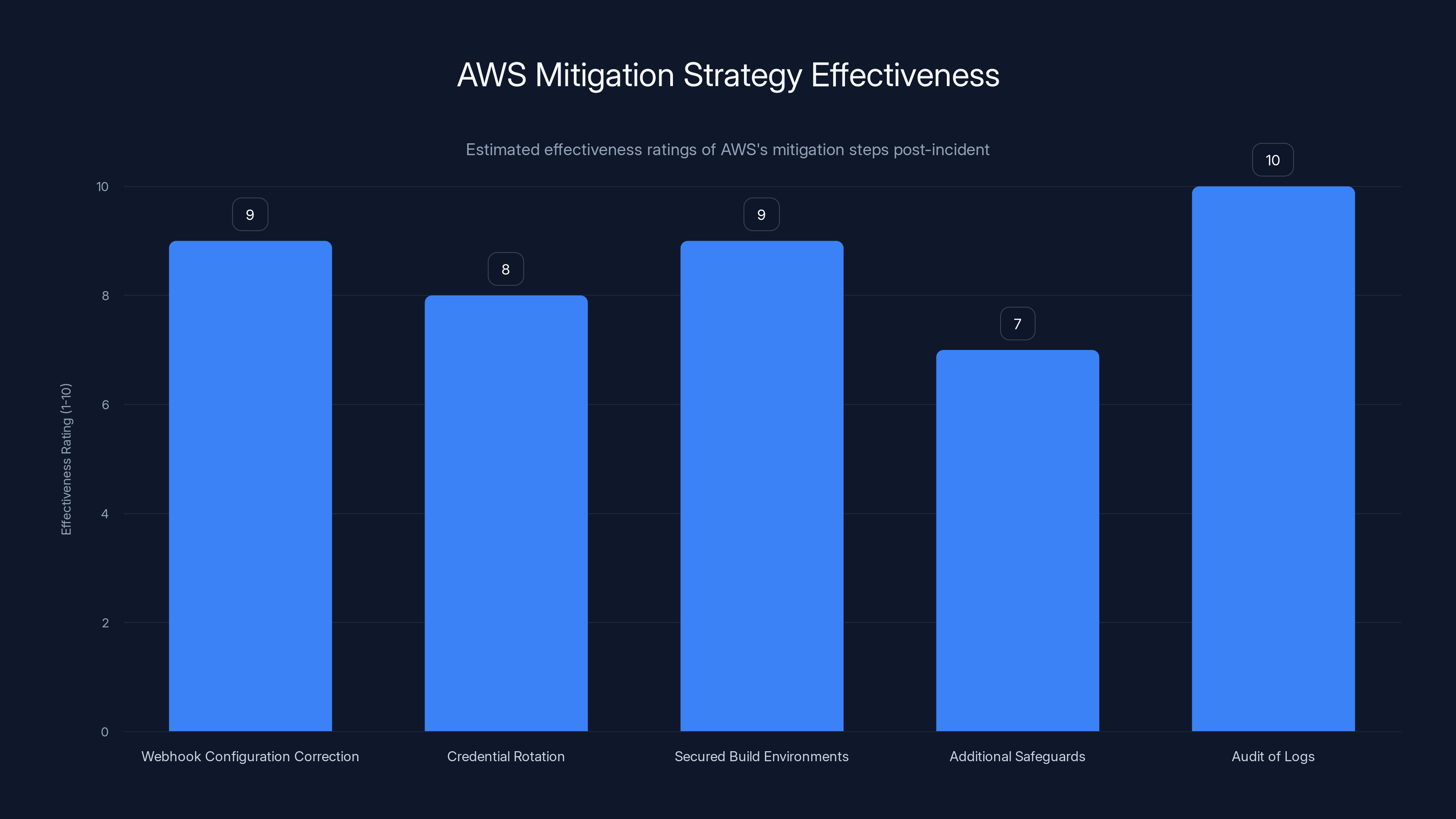

Estimated data suggests that auditing logs and correcting webhook configurations were the most effective mitigation steps taken by AWS, with ratings of 10 and 9 respectively.

The Technical Deep Dive: How Code Breach Actually Worked

Here's where the vulnerability gets genuinely clever, and by clever, I mean clever in a terrifying way.

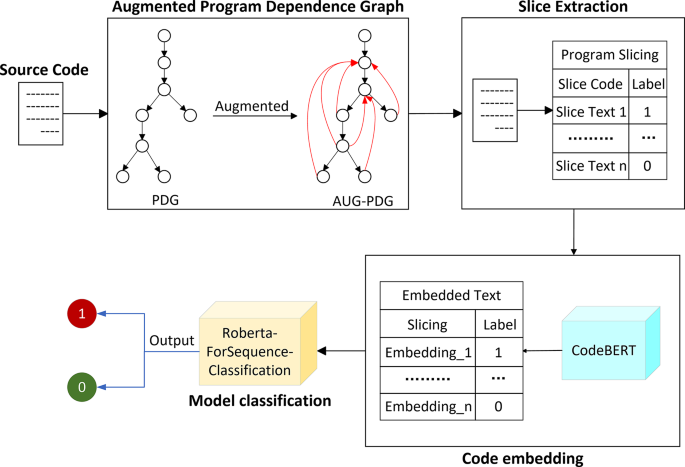

Wiz discovered that AWS Code Build was checking whether a GitHub user was allowed to trigger privileged builds using regex pattern matching. This is a reasonable approach. You store a list of approved GitHub users (or patterns that match approved users), and whenever a webhook comes in, you check if the user matches one of those patterns.

The problem was in how those patterns were written. They used unanchored regex patterns. Let me explain what that means because it's crucial to understanding why this is such a big deal.

A regex pattern is basically a template for matching text. If you want to match the string "alice," you could write the pattern alice. That's an exact match. If you use an anchored pattern, you're being specific about where in the string the match needs to occur. Anchored means you're saying "this pattern must match at the beginning and end of the string, with nothing extra."

But if your pattern is unanchored, you're just saying "this substring needs to appear somewhere in the user ID." It's a huge difference.

Let's say AWS Code Build had approved the user octocat to trigger privileged builds. A properly anchored regex would look something like this:

^octocat$

That means "match only if the entire string is exactly 'octocat' and nothing else." With that pattern, a user named octocat-admin wouldn't match. A user named evil-octocat wouldn't match. Only octocat matches.

But if the pattern was unanchored and just looked like this:

octocat

Now any user ID containing the substring octocat would match. octocat-admin? Match. evil-octocat? Match. octocat-evil-attacker-123? Match. The attacker could predict or craft a user ID that contains the approved substring, bypass the validation entirely, and trigger a privileged build.

This is a classic authorization bypass vulnerability, and it's particularly dangerous in the context of CI/CD because the stakes are so high. You're not just bypassing access to some low-value resource. You're gaining the ability to run arbitrary code in an environment that has powerful AWS credentials and GitHub tokens.

Once an attacker triggered a privileged build using this bypass, they could do something even more dangerous. They could access the GitHub tokens that were stored in the build environment as environment variables. These tokens are secrets. They're the kind of credentials that let you push code to repositories, create releases, modify workflows, and generally do whatever you want in GitHub.

With those tokens, an attacker could do several things:

Push malicious code directly to AWS repositories: No pull request, no review, no visibility. Just straight commits to main branches.

Modify CI/CD workflows: Change the build scripts to inject backdoors into compiled binaries that AWS ships to customers.

Create malicious releases: Package compromised software and release it with legitimate version numbers.

Compromise other repositories: If the token had access to multiple repositories (as tokens often do), the attacker could move laterally across AWS's entire GitHub organization.

The supply chain attack implications here are absolutely massive. If AWS's public repositories were compromised, the impact could have affected millions of developers and thousands of companies that depend on AWS open-source tools, SDKs, and infrastructure-as-code templates.

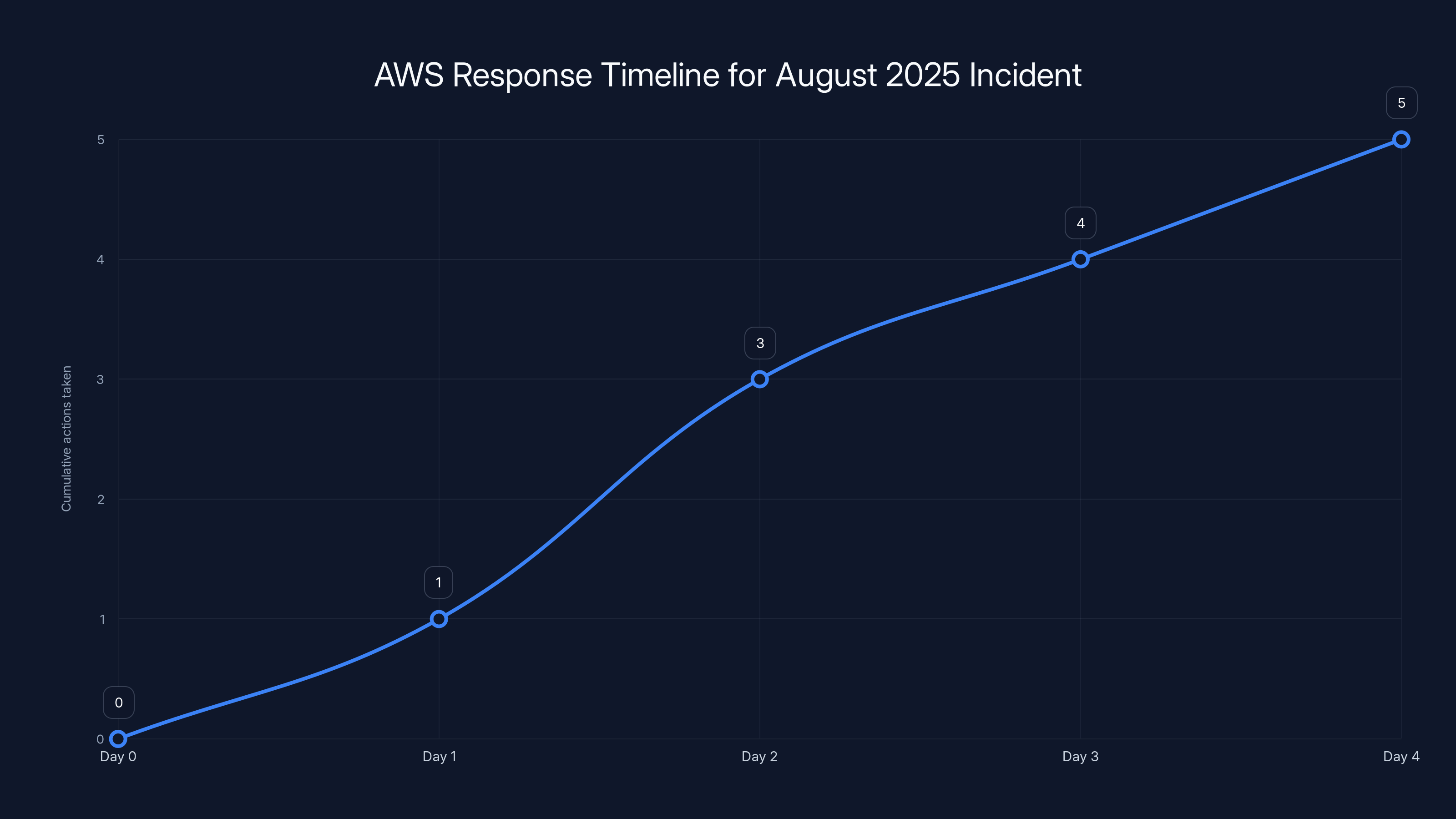

The Timeline: August 2025 and the 48-Hour Fix

Let's talk about the actual timeline of this incident because it matters for understanding both how serious this was and how AWS responded.

Wiz discovered the misconfiguration in late August 2025. This is important: Wiz found this proactively through security research, not because someone was actively exploiting it. They didn't stumble upon this because it was being abused in the wild. They found it because they're good at what they do and they were specifically researching AWS security.

Wiz reported the vulnerability to AWS through proper responsible disclosure channels. This is how security research is supposed to work. You find a problem, you tell the vendor privately first, and you give them time to fix it before you go public.

AWS moved fast. Within 48 hours of first disclosure, they fixed the core issue. They corrected the misconfigured webhook filters that were using unanchored regex patterns. This is genuinely impressive response time for a vulnerability of this severity in a service as complex as AWS Code Build.

But AWS didn't stop there. After fixing the immediate issue, they did several additional things:

Rotated all credentials: Any GitHub token or AWS credential that was stored in build environments got cycled out.

Secured build environments: They audited all public build processes to make sure nothing else was exposed.

Added additional safeguards: This is vague in the official statement, but it likely means adding additional validation layers, better logging, and more restrictive defaults.

Then AWS did the really important part. They audited all the logs. Every CloudTrail log, every GitHub event, every interaction with the affected repositories. They specifically looked for evidence that anyone else had exploited this vulnerability using the same attack pattern that Wiz demonstrated.

Their conclusion: no exploitation detected. No evidence that any bad actors had taken advantage of this before Wiz found it.

That's luck. Real, genuine luck. The vulnerability existed for some unknown period of time. It was affecting AWS's own repositories. And nobody else exploited it before responsible disclosure happened. This could have gone very differently.

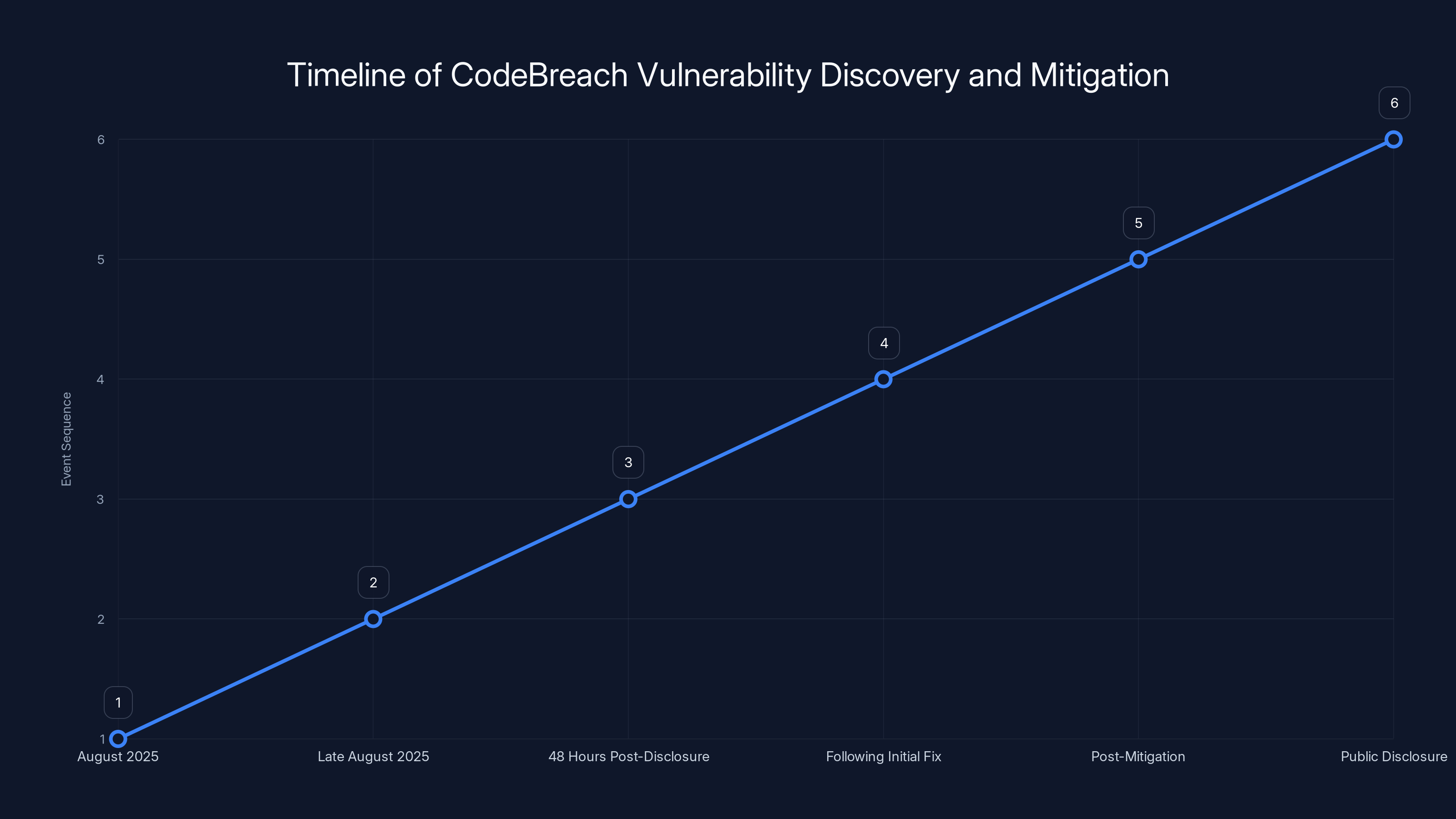

AWS responded swiftly to the vulnerability discovered in August 2025, fixing the core issue within 48 hours and implementing additional security measures in the following days. (Estimated data)

Why This Matters: The Supply Chain Attack Threat

I want to take a step back here and talk about why this vulnerability is so important even though it was patched and apparently never exploited.

Supply chain attacks are the worst kind of attacks because they're asymmetrical. An attacker doesn't need to compromise you directly. They just need to compromise something you trust and depend on. If they can inject malicious code into a library that a million developers use, they've compromised a million developers.

This is increasingly the preferred attack method for sophisticated threat actors. Nation-states and well-funded criminal groups have largely moved away from attacking individual companies directly. Why? Because compromising one company gets you one company. But compromising the software supply chain gets you everyone who uses that software.

The SolarWinds breach in 2020 is the classic example. Attackers didn't break into individual companies. They broke into SolarWinds and compromised the Orion software update process. Suddenly, thousands of organizations that trusted SolarWinds were running malware. The attack impacted at least 18,000 customers, including government agencies, Fortune 500 companies, and critical infrastructure operators.

What happened with Code Breach could have been worse because the target is higher in the supply chain. If attackers had compromised AWS open-source repositories, they wouldn't have compromised individual companies or even individual products. They would have compromised the infrastructure platform that millions of companies depend on.

Think about what that means. AWS SDKs in thousands of programming languages. Infrastructure-as-code templates that companies copy into their deployments. Open-source tools that are forked and incorporated into other projects. If any of that gets compromised, the blast radius is enormous.

There's another angle here too. AWS is trusted. When you download an AWS SDK or use an AWS open-source tool, you're not scrutinizing the code the way you might scrutinize some random GitHub project from an unknown developer. Trust is currency in the supply chain, and AWS has earned a lot of it. An attacker who could exploit that trust by injecting malicious code into AWS repositories would have an incredibly effective attack vector.

This is why Code Breach matters. It's not just a vulnerability in a misconfiguration. It's a vulnerability that could have been weaponized to compromise the supply chain for millions of organizations.

The Core Issue: Unanchored Regex Patterns and Why They're Dangerous

Let's dig deeper into the technical issue because understanding the root cause is crucial for preventing similar problems in your own systems.

Regex patterns are powerful, but they're also easy to get wrong. The difference between a secure pattern and an insecure pattern is often just a couple of characters: the anchors ^ and $.

When you write a security-critical regex pattern, you need to be explicit about what you're trying to match. If you're validating a GitHub username against an allowlist, you're not trying to find the username substring somewhere in a longer string. You're trying to match exactly that username and nothing else.

Here's a real-world example. Let's say you're a company that uses AWS Code Build and you want to allow only certain GitHub users to trigger production deployments. You might write an allowlist that looks like this:

devops-team

security-team

release-engineer

Now, every time someone opens a pull request or pushes code to a repository, GitHub sends a webhook to Code Build that includes the username. Code Build checks: is this username in the allowlist? If yes, it runs the build with production deployment permissions.

If you implement this check with unanchored regex, you've created a security hole. An attacker could register a GitHub username like devops-team-evil or devops-team-2 or attack-devops-team and potentially bypass your validation. Depending on how the regex is written, they might be able to match with just the substring.

This is such a common vulnerability that it's covered in every secure coding guideline. The OWASP Top 10 doesn't explicitly mention unanchored regex, but it's related to Broken Access Control (which is #1 on the list).

The reason this is so dangerous in the context of AWS Code Build is that the stakes are enormous. You're not just validating access to a generic resource. You're validating access to execute arbitrary code in an environment with powerful credentials. A small mistake in your validation logic becomes a critical security issue.

The timeline highlights the swift response by AWS to the CodeBreach vulnerability, with a fix implemented within 48 hours of disclosure. Estimated data.

How AWS Code Build Webhooks Actually Work (And Why They Matter)

To understand the full context of Code Breach, you need to understand how GitHub webhooks integrate with AWS Code Build.

GitHub webhooks are notifications that GitHub sends to external services whenever certain events happen in a repository. You can configure webhooks for push events, pull request events, release events, and many other types of events. When something happens, GitHub sends an HTTP POST request to a URL you specify, with JSON data describing what happened.

AWS Code Build can listen to these webhooks. You connect your GitHub repository to Code Build, and whenever GitHub sends a webhook, Code Build receives it and decides whether to trigger a build.

But here's the important part: different events can trigger builds with different permission levels. Some builds run with limited permissions. Some builds run with full permissions including access to deployment credentials, secrets, and other sensitive resources.

The idea is to be more restrictive for builds triggered by external events (like pull requests from external contributors) and less restrictive for builds triggered by trusted sources (like commits pushed by your team).

So Code Build's webhook handler needs to be smart. It needs to look at the event coming from GitHub and determine: who triggered this? Can they trigger privileged builds? Or should this build run with limited permissions?

This validation happens based on rules that are configured in Code Build. You can specify that only certain GitHub users or certain types of events are allowed to trigger privileged builds. Code Build checks the incoming webhook against these rules and makes a decision.

The Code Breach vulnerability was in this validation logic. The rules used unanchored regex patterns, so the validation wasn't as strict as it should have been.

Here's what a typical Code Build webhook validation might look like (simplified pseudocode):

if webhook.trigger_type == "pull_request" and webhook.author == "external":

build_permissions = "limited"

else if webhook.author in approved_users_list:

build_permissions = "full"

else:

build_permissions = "denied"

With unanchored regex in the approved_users_list check, an attacker could create a username that contains an approved username as a substring and potentially bypass this validation.

What makes this worse is that Code Build's webhook handler runs at the infrastructure level. It's not something you can easily debug or inspect. It's AWS's code running in AWS's infrastructure. If the validation is broken at this level, it's broken for all users who have webhooks configured.

The Wiz Research: How They Discovered Code Breach

It's worth understanding how Wiz actually discovered this vulnerability because it says something important about modern security research and how vulnerabilities are being found.

Wiz is a cloud security company that focuses on infrastructure misconfiguration and supply chain risks. They're not looking for individual vulnerabilities in specific services. They're looking for patterns. They're looking at how cloud services handle sensitive operations, where credentials live, and what could go wrong if access controls are bypassed.

Their research was focused on a specific question: how vulnerable is the AWS supply chain to attack? They were specifically looking at AWS's use of Code Build to manage its own repositories. If AWS uses Code Build for its own CI/CD, what does that security look like?

This is called "infrastructure security research" and it's becoming more common. Instead of looking at a specific service in isolation, researchers look at how services work together and where the security boundaries are weak.

Wiz likely started by looking at AWS's public GitHub repositories. They probably found the webhook configurations for Code Build. They examined the validation logic. And they found the unanchored regex patterns.

Once they found the vulnerability, they wrote a proof of concept (a demonstration of how the vulnerability could be exploited). The PoC likely showed how an attacker could:

- Create or register a GitHub user with a name designed to bypass the regex validation

- Trigger a webhook event (like opening a pull request) with that user

- Have Code Build trigger a privileged build because the validation was bypassed

- Access the GitHub token in the build environment

- Use that token to push malicious code to AWS repositories

Then Wiz did the right thing. They didn't publish their findings. They didn't attempt to exploit the vulnerability on AWS systems. They reported it to AWS through responsible disclosure channels.

This is genuinely impressive work because it required understanding not just how Code Build works, but how AWS uses it internally, what permissions are needed, and what the worst-case scenario would be.

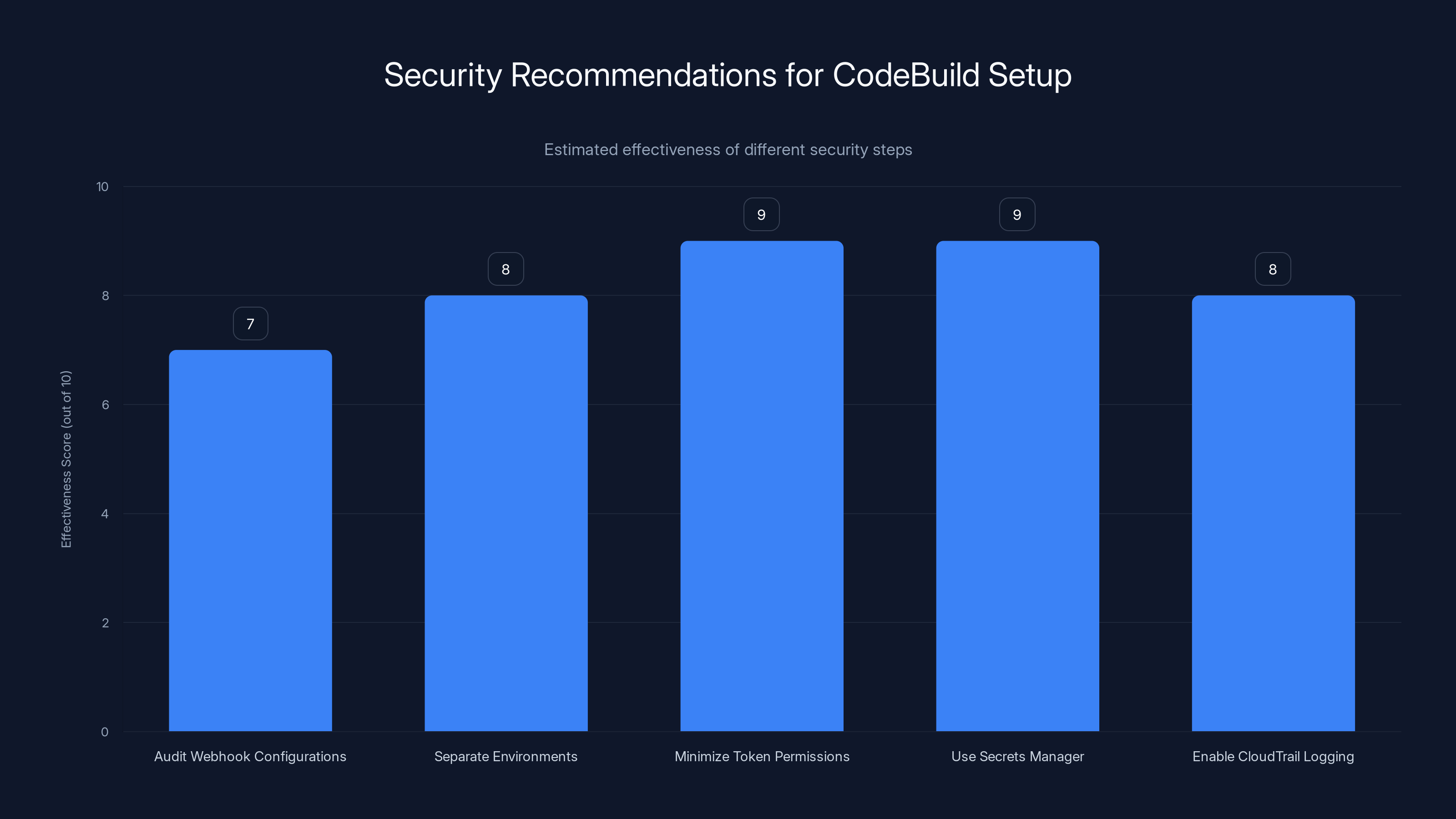

Estimated data: Implementing these security steps can significantly enhance the security of your CodeBuild setup, with minimizing token permissions and using Secrets Manager being particularly effective.

AWS's Official Statement and Mitigation Strategy

Let's look at what AWS actually said in their official response, because corporate statements about security incidents often contain clues about what actually happened and how serious it was.

AWS stated: "AWS investigated all reported concerns highlighted by Wiz's research team in 'Infiltrating the AWS Console Supply Chain: Hijacking Core AWS GitHub Repositories via Code Build.'" This language is important. They're acknowledging that Wiz's research was specifically about compromising AWS's own GitHub repositories. This wasn't just a hypothetical vulnerability. This was a vulnerability that could have affected AWS's own infrastructure.

Then they outlined their mitigation steps:

Corrected webhook filter configuration: This is the immediate fix. They went through all their webhook configurations and fixed the unanchored regex patterns to use anchored patterns instead.

Rotated credentials: Any credentials that might have been exposed were cycled out. This is important because if an attacker had access at any point, the old credentials are now worthless.

Secured build environments: They audited all build processes that contained GitHub tokens or other credentials and made sure they were properly protected.

Additional safeguards: This is vague, but likely includes things like:

- More restrictive default permissions for webhooks

- Additional logging and monitoring of webhook events

- Automated scanning of webhook configurations to detect other similar issues

- Updated documentation and training for teams using Code Build

Then AWS did something really important. They audited the logs. They didn't just fix the vulnerability and move on. They looked at every interaction with the affected repositories going back some unspecified period of time. They checked CloudTrail logs (which track AWS API activity) and GitHub logs (which track repository activity). They were specifically looking for evidence of someone exploiting this vulnerability.

Their finding: no evidence of exploitation. No suspicious builds triggered by unauthorized users. No commits pushed by accounts that shouldn't have access. As far as they could tell, nobody else exploited this vulnerability before Wiz found it.

AWS also stated: "AWS determined the issue was project-specific and not a flaw in the Code Build service itself." This is an important clarification. They're saying the vulnerability wasn't in the Code Build source code. The Code Build service itself works as designed. The problem was in how Code Build was configured for these specific projects. In other words, the vulnerability wasn't everyone's problem, just the problem of whoever had these bad configurations.

But here's the thing: this doesn't mean other customers are safe. If the issue is "project-specific," that means it's a configuration issue. And if AWS misconfigured Code Build for its own projects, there's a reasonable chance that customers could make similar mistakes.

What This Means for Code Build Customers

Here's the question that matters for people actually using Code Build: could you have this same vulnerability?

The answer is yes, absolutely. The root cause isn't a bug in Code Build. It's a configuration mistake that anyone could make. If you're using Code Build with GitHub webhooks and you've written a regex pattern to validate approved users, and that pattern isn't anchored, you have the same vulnerability.

This is why AWS is recommending that customers review their CI/CD configurations. Specifically, they're recommending that you:

Audit your webhook filters: Go through every webhook you've configured in Code Build. Look at the regular expressions used to validate GitHub users. Are they anchored? Are they doing substring matching or exact matching?

Limit token privileges: The damage from Code Breach was limited by the fact that the tokens in build environments have specific permissions. You should ensure that the tokens used in your build environments have the minimum permissions necessary to do their job. Don't give a GitHub token to Code Build if it's going to be used for building and testing. You only need that token if you're actually going to interact with GitHub. And if you do interact with GitHub, the token should have the minimum required permissions.

Prevent untrusted pull requests from triggering privileged builds: This is a fundamental security practice. External contributors should never be able to trigger builds that run with your full credentials and permissions. If someone opens a pull request from a fork of your repository, that build should run with limited permissions. Only builds triggered by your core team should run with full permissions.

Use separate credentials for different permission levels: Don't use the same credentials for privileged builds and unprivileged builds. If an unprivileged build environment is compromised, you don't want that giving access to privileged operations.

Estimated data suggests that if CodeBreach had been exploited, it could have affected millions of developers, compromised thousands of repositories, and impacted a significant number of AWS customers. Estimated data.

The Broader Security Implications

While Code Breach was a specific vulnerability in a specific service, it reveals some broader security challenges that affect cloud infrastructure security more generally.

The first is that security is often implemented through configuration rather than enforcement. Code Build itself works correctly. It's the configuration of Code Build that was insecure. This means you can't just rely on a service working correctly. You have to be responsible for configuring it correctly. And configuration mistakes are incredibly common.

The second is that supply chain attacks are increasingly realistic and increasingly valuable targets. Five years ago, a supply chain attack meant compromising a major software vendor or library. Today, it means compromising a popular GitHub repository, a CI/CD pipeline, a package repository, or a software distribution system. The attack surface has expanded enormously.

The third is that security in cloud infrastructure requires understanding not just individual services, but how services integrate with each other and where the security boundaries are. Code Build is secure. GitHub is secure. But the integration between them can be insecure if you're not careful about how you configure it.

The fourth is that logging and auditing are your safety net. AWS caught the potential impact of this vulnerability by auditing the logs. They were able to say with confidence that nobody had exploited it because they had records of every action. If you're not logging your CI/CD activities, you won't know if someone exploits a similar vulnerability in your infrastructure.

Lessons Learned: What This Teaches Us About CI/CD Security

Code Breach teaches several important lessons about how to secure CI/CD pipelines in 2025 and beyond.

Lesson 1: Trust Boundaries Matter: Your CI/CD pipeline is a trust boundary. Anything that crosses this boundary (external code, external users, external systems) should be treated with suspicion. Internal operations (builds triggered by your team, deployments to production) can have more trust. The key is being explicit about which side of the boundary you're on and validating that strictly.

Lesson 2: Validation Must Be Precise: If you're validating anything related to access control, be precise. Use exact matching when possible. Use anchored patterns in regex. Be specific about what you're allowing. Overly broad validation rules (like substring matching) create security holes.

Lesson 3: Defense in Depth Matters: Code Breach would have been less severe if there were multiple layers of protection. If the webhook validation was stronger, an attacker couldn't trigger a privileged build. If the build environment credentials had more limited permissions, an attacker couldn't do as much damage. If there was better logging, the attack would have been detected. The lesson is to have multiple layers of security so one mistake doesn't compromise everything.

Lesson 4: Credentials in Build Environments Are Dangerous: GitHub tokens in build environments are incredibly valuable to attackers. The fact that Code Build needs these tokens is unavoidable, but you should minimize how many builds have access to them, limit the permissions on those tokens, and audit how they're used.

Lesson 5: Audit Your Infrastructure Regularly: AWS found this vulnerability through proactive security research. They weren't responding to an attack. They were looking for security issues systematically. You should do the same. Regularly audit your CI/CD configurations. Look for overly permissive rules. Look for credentials that are too broadly accessible. Look for validation logic that might be bypassed.

Practical Recommendations for Securing Your Code Build Setup

If you're using AWS Code Build, here are concrete steps you can take right now to improve your security posture.

Step 1: Audit Your Webhook Configurations

Go to the AWS console. Find every Code Build project that has a GitHub webhook. For each project, review the webhook configuration. Look at any rules that specify which GitHub users are allowed to trigger builds. Check if those rules use anchored regex patterns.

If you see patterns like devops without anchors, change them to ^devops$. If you see patterns that do substring matching, consider whether you really need that level of flexibility.

Step 2: Separate Privileged and Unprivileged Build Environments

Create at least two separate Code Build projects: one for untrusted builds (pull requests from external contributors) and one for trusted builds (commits from your team). The untrusted build should run with limited permissions. The trusted build can run with full permissions.

Configure your GitHub webhook to trigger the untrusted build for pull requests and the trusted build for commits to main branches.

Step 3: Minimize Token Permissions

If you're using GitHub tokens in your build environment, make sure those tokens have the minimum required permissions. GitHub's token permission model is granular. Use it. If a token only needs to read repository information, don't give it push permissions. If it only needs to push to a specific repository, don't give it permissions to your entire organization.

Step 4: Use Secrets Manager for Credentials

Instead of storing credentials directly in your Code Build environment, use AWS Secrets Manager. This allows you to store credentials centrally, rotate them easily, and audit who accessed them.

Step 5: Enable CloudTrail Logging

Make sure CloudTrail is enabled for your AWS account and that it's logging Code Build API calls. This gives you visibility into what's happening in your build infrastructure. If someone does trigger an unauthorized build, you'll have a record of it.

Step 6: Monitor Build Logs

Implement log monitoring for your Code Build logs. Look for unusual activity like builds triggered by unexpected users or builds that access secrets they shouldn't have access to.

Step 7: Implement Branch Protection Rules

In GitHub, enable branch protection rules for your main branches. Require code review before merging. This is your last line of defense against malicious code. Even if an attacker triggers a build and pushes code to GitHub, they shouldn't be able to merge it without approval.

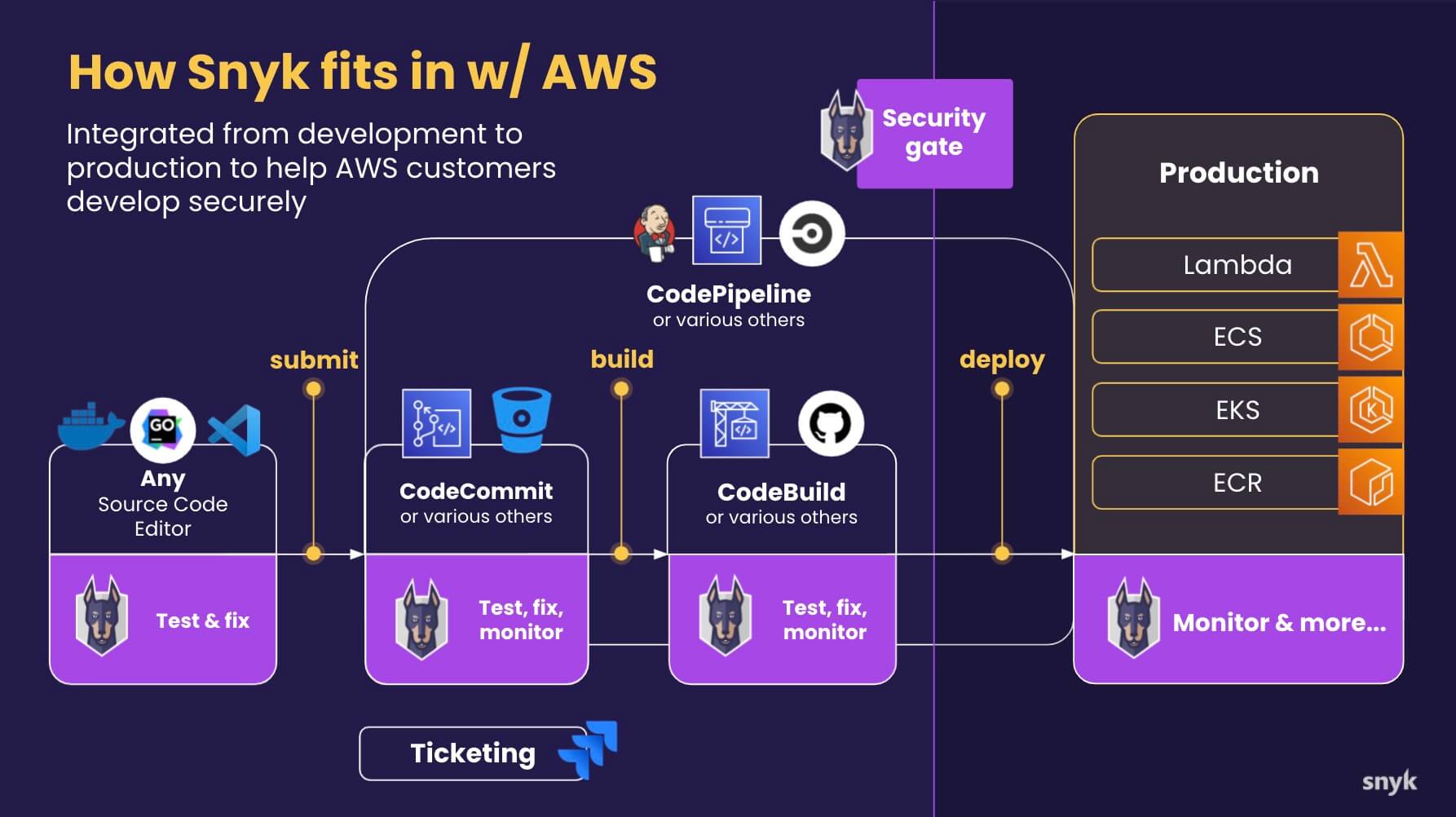

The Role of Supply Chain Security Tools

Code Breach highlights why supply chain security tools and practices have become so important.

There are several categories of tools that can help you defend against vulnerabilities like Code Breach:

Static analysis tools for CI/CD configuration: These tools scan your CI/CD pipeline configuration files (like Code Build buildspec files) and look for security issues. They can flag overly permissive rules, credentials in environment variables, and other red flags.

Software composition analysis (SCA) tools: These tools inventory every dependency in your code and check them against databases of known vulnerabilities. If a dependency is compromised as part of a supply chain attack, SCA tools can help you identify it.

Artifact scanning and verification: You can cryptographically sign your build artifacts and verify those signatures when you use them. If someone injects malicious code into your build, the signature won't match.

Infrastructure-as-Code security scanning: If you're using IaC to manage your Code Build configuration, you can scan those files for security issues before they're deployed.

Runtime security monitoring: Tools like AWS GuardDuty can monitor your build environments at runtime and alert you to suspicious activity.

The point is that Code Breach is just one vulnerability, but the category of supply chain attacks is large and growing. Using a layered approach with multiple categories of tools gives you better visibility and faster detection if something goes wrong.

Timeline and Key Dates: What Happened When

Let me consolidate the timeline so it's clear:

August 2025: Wiz discovers the Code Breach vulnerability in AWS Code Build. They identify unanchored regex patterns in webhook validation that could be bypassed to trigger unauthorized privileged builds.

Late August 2025: Wiz reports the vulnerability to AWS through responsible disclosure channels. They provide a detailed technical analysis and proof of concept.

Within 48 hours of disclosure: AWS fixes the core issue. They correct the misconfigured webhook filters and anchor the regex patterns properly.

Following the initial fix: AWS rotates all exposed credentials, audits build environments, and adds additional safeguards.

Post-mitigation: AWS audits all logs and determines there is no evidence of exploitation. They audit all other public build environments to ensure similar issues don't exist elsewhere.

Public disclosure: AWS and Wiz coordinate on public disclosure of the vulnerability, allowing customers to understand the issue and secure their own configurations.

This timeline is important because it shows that responsible disclosure works, but it also shows how quickly AWS moved once the vulnerability was reported. If an attacker had found this vulnerability before Wiz did, there would have been no 48-hour fix. The attacker could have exploited it for weeks or months before discovery.

What AWS Got Right (and What It Got Less Right)

AWS's response to Code Breach was generally solid, but there are some nuances worth understanding.

What they got right:

- Fast response time (48 hours to fix the core issue)

- Thorough investigation (auditing logs, checking for exploitation)

- Additional mitigations beyond just fixing the bug

- Transparent communication about what happened

What could have been better:

- Earlier prevention (unanchored regex patterns shouldn't have been used in the first place)

- More specific guidance for customers about what to do

- Earlier detection (this vulnerability might have existed for a long time; we don't know when it was introduced)

- More details about what the "additional safeguards" are

The honest truth is that AWS is a massive organization with thousands of services and millions of configurations. Mistakes happen. The question is how quickly you fix them, and whether you learn from them. AWS seems to have done both.

How This Affects Different Types of AWS Customers

The impact of Code Breach varies depending on who you are and how you use AWS Code Build.

If you're a small team using Code Build for CI/CD: Code Breach probably didn't affect you directly because AWS only configured it for AWS-managed repositories. But the lesson applies to you. You should audit your own Code Build configurations to make sure you don't have similar issues.

If you're an enterprise with many Code Build projects: You should systematically review all your projects, especially those with GitHub integration and those that run privileged builds.

If you're using Code Build for open-source projects: This is where the vulnerability would have been most dangerous for you. Open-source projects are often more exposed to external contributions and pulls requests. You should be especially careful about which builds trigger with privileged permissions.

If you're a GitHub user whose code is built with Code Build: You benefit from the fact that AWS caught this and fixed it. But it's a reminder that the software supply chain is under constant threat. You should be thinking about how the code you depend on is built and deployed.

The Bigger Picture: Supply Chain Security in 2025

Code Breach is just one vulnerability in one service, but it's part of a larger trend. Supply chain attacks are becoming more sophisticated, more common, and more valuable to attackers.

In 2024-2025, we've seen:

- Compromised npm packages: Attackers have repeatedly compromised popular npm packages to inject backdoors

- PyPI package attacks: Python packages have been compromised for stealing credentials

- Docker image tampering: Container images have been modified with malicious code

- GitHub Actions compromises: Malicious GitHub Actions have been created to harvest secrets

- Kubernetes manifest injection: Attackers have injected malicious manifests into open-source projects

Code Breach fits into this pattern. It's a vulnerability that could have been weaponized for a massive supply chain attack. The fact that it was patched before exploitation doesn't mean we're safe. It means we got lucky this time.

The lesson for 2025 and beyond is that supply chain security needs to be a first-class concern. You can't just focus on securing your own infrastructure. You need to think about the supply chain: where does your code come from, how is it built, how is it deployed, and at each stage, what are the security controls?

FAQ

What is the Code Breach vulnerability?

Code Breach is a critical misconfiguration in AWS Code Build that allowed attackers to bypass user validation and trigger unauthorized privileged builds. The vulnerability used unanchored regex patterns in webhook filters that would match any GitHub username containing an approved username as a substring, enabling attackers to hijack builds and access sensitive credentials like GitHub tokens stored in build environments.

How did the Code Breach vulnerability work technically?

The vulnerability worked through improper regex pattern validation in GitHub webhook handlers. AWS Code Build used unanchored regex patterns (like octocat instead of ^octocat$) to validate which GitHub users could trigger privileged builds. An attacker could register a GitHub username like octocat-evil or evil-octocat that contained the approved substring, bypassing the validation logic. Once validated, the attacker could trigger a privileged build and access GitHub tokens in the build environment.

What was the potential impact of Code Breach if it had been exploited?

If exploited, Code Breach could have enabled a massive supply chain attack affecting millions of developers. An attacker could have accessed GitHub tokens from build environments and used them to push malicious code to AWS-managed repositories. This compromised code could have been incorporated into AWS SDKs, open-source tools, and infrastructure-as-code templates, creating a platform-wide supply chain attack that would ripple across the entire tech industry and compromise countless AWS customers.

Who discovered the Code Breach vulnerability and when?

The vulnerability was discovered by Wiz, a cloud security research company, in late August 2025. Wiz was conducting proactive security research on AWS supply chain security when they identified the misconfigured webhook filters in AWS Code Build. They reported the vulnerability to AWS through responsible disclosure channels rather than publicly or maliciously.

How quickly did AWS fix the Code Breach vulnerability?

AWS fixed the core issue (correcting the unanchored regex patterns in webhook filters) within 48 hours of Wiz's initial disclosure in late August 2025. Beyond the immediate fix, AWS also rotated credentials, audited all build environments and logs, and implemented additional safeguards. AWS audited logs to confirm there was no evidence of exploitation before the vulnerability was fixed.

What should I do right now if I use AWS Code Build?

Immediately audit all your Code Build projects that use GitHub webhooks, especially those with privileged builds. Check your webhook filter configurations and ensure all regex patterns are properly anchored (use ^pattern$ instead of just pattern). Limit GitHub token privileges to the minimum required, separate privileged and unprivileged build environments, prevent untrusted pull requests from triggering privileged builds, enable CloudTrail logging, and monitor your build activity for suspicious patterns.

Is my AWS account affected by the Code Breach vulnerability?

The Code Breach vulnerability specifically affected AWS-managed repositories that use Code Build. However, AWS customers could have created similar misconfigurations in their own Code Build projects. The vulnerability itself (unanchored regex patterns in webhook validation) is something any Code Build user could accidentally implement. You should audit your own configuration to determine if you're affected.

What is an unanchored regex pattern and why is it a security problem?

An unanchored regex pattern matches a substring anywhere in a string, while an anchored pattern matches the entire string. For example, octocat (unanchored) matches octocat, octocat-admin, admin-octocat, and octocat-evil, but ^octocat$ (anchored) matches only exactly octocat. In security contexts, substring matching can allow attackers to craft usernames or other identifiers that bypass access control rules, which is why anchored patterns are essential for validation.

Why are credentials in CI/CD build environments a security risk?

Build environments typically contain credentials like GitHub tokens, AWS access keys, and API keys that are needed for the build process to work. If an attacker can trigger a build or gain access to a build environment, they can extract these credentials and use them for malicious purposes like pushing backdoored code, modifying repositories, or accessing other systems. This is why Code Breach was so dangerous: it gave attackers a way to access those credentials.

Closing Thoughts: Staying Ahead of Supply Chain Threats

Code Breach is a reminder that security in modern cloud infrastructure is never finished. It's not enough to build a service like Code Build correctly. You have to configure it correctly. You have to integrate it securely with other services like GitHub. You have to monitor it continuously. And you have to be prepared to respond quickly when vulnerabilities are discovered.

The good news is that this vulnerability was caught before exploitation. AWS responded quickly. And the cloud security community can learn from what happened and improve their defenses.

The bad news is that this won't be the last supply chain vulnerability. Attackers are increasingly sophisticated. They're targeting the infrastructure platforms that billions of people depend on. And each successful attack against the supply chain affects far more people than an attack against a single company.

If you take nothing else from this article, take this: audit your CI/CD configurations regularly. Treat your build infrastructure as security-critical infrastructure because it is. Use the principle of least privilege everywhere. Keep your logs. And stay vigilant.

The supply chain is only as strong as its weakest link. Make sure your link isn't the weak one.

Key Takeaways

- CodeBreach was an AWS CodeBuild misconfiguration using unanchored regex patterns that allowed attackers to bypass user validation and trigger privileged builds

- The vulnerability could have enabled supply chain attacks affecting millions of developers by exposing GitHub tokens and allowing malicious code injection into AWS repositories

- AWS fixed the core issue within 48 hours of Wiz's responsible disclosure with no evidence of real-world exploitation detected

- Critical recommendations include auditing webhook configurations, limiting token permissions, separating privileged builds, enabling CloudTrail logging, and implementing branch protection rules

- CodeBreach exemplifies the need for defense-in-depth security strategies in CI/CD pipelines and demonstrates why supply chain security has become a critical concern in 2025

Related Articles

- N8n Ni8mare Vulnerability: What 60,000 Exposed Instances Need to Know [2025]

- VoidLink: The Chinese Linux Malware That Has Experts Deeply Concerned [2025]

- FCC Cyber Trust Mark Program: UL Solutions Withdrawal & National Security Impact [2025]

- Jen Easterly Leads RSA Conference Into AI Security Era [2025]

- Pax8 Data Breach: 1,800 MSPs Exposed in Email Mistake [2025]

- VoidLink: The Advanced Linux Malware Reshaping Cloud Security [2025]

![AWS CodeBuild Supply Chain Vulnerability: What You Need to Know [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/aws-codebuild-supply-chain-vulnerability-what-you-need-to-kn/image-1-1768579743365.jpg)