The Hydrogen Revolution Nobody Saw Coming to Data Centers

For years, hydrogen has been the clean energy promise that never quite materialized. The automotive industry threw billions at it. Tesla laughed. Hydrogen fuel cell cars remained a rounding error in global vehicle sales. But here's what actually happened while everyone was watching the car industry fail: industrial hydrogen demand never stopped growing, and a completely different source just became viable.

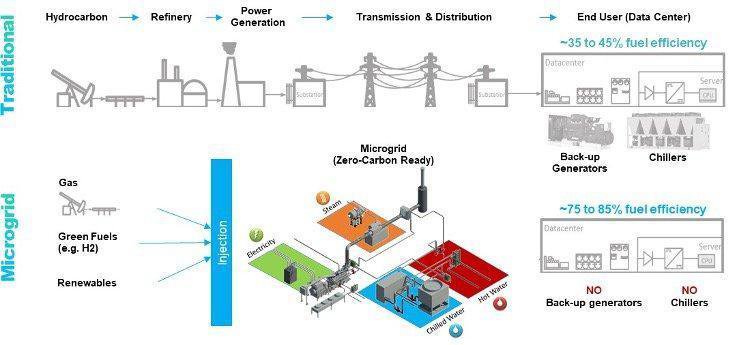

Data centers are consuming more electricity than entire countries. Google, Meta, Amazon, and Microsoft are all racing to find power sources that don't require them to pay carbon offset premiums forever. Battery storage helps. Nuclear micro-reactors are finally becoming real. But there's another player now: engineered mineral hydrogen, and it's about to change where data centers actually get built.

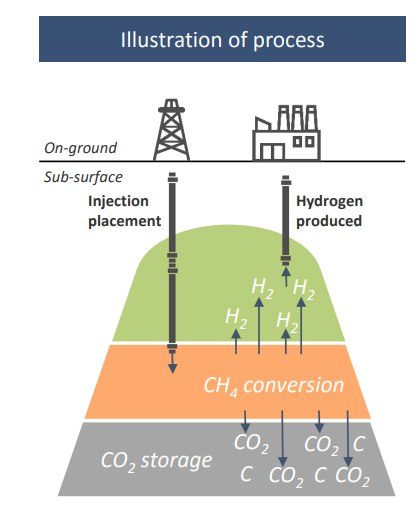

The story starts with geology, not technology. Certain types of rock formations—specifically ophiolite, an iron-rich rock that was literally pushed up from the ocean floor by plate tectonics millions of years ago—naturally contain hydrogen. When you inject water into these rocks at depth, apply heat and pressure, add some catalysts, hydrogen gas comes out. No methane reforming. No carbon dioxide. Just hydrogen.

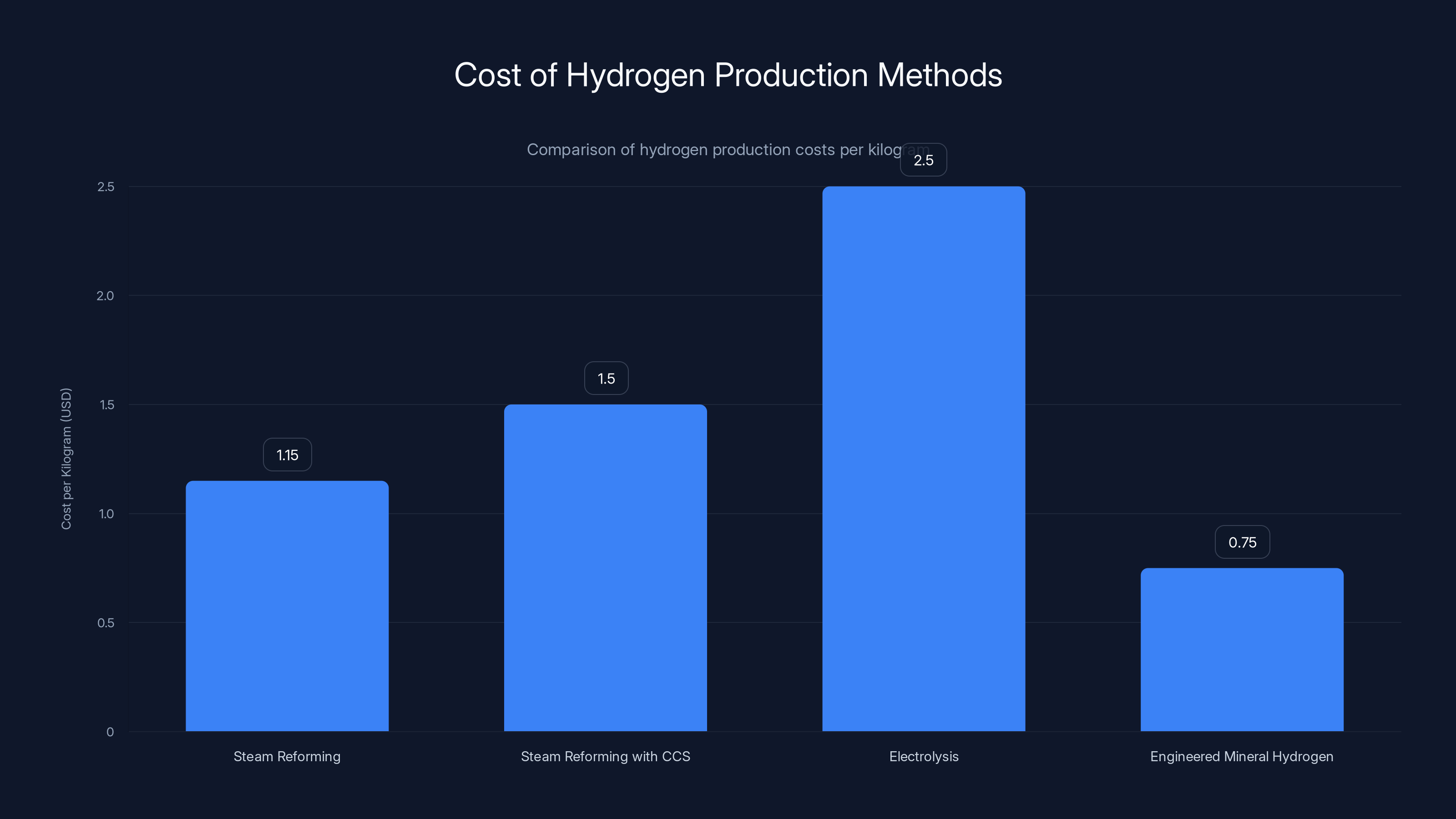

Vema Hydrogen figured out how to drill wells into these formations and extract hydrogen at scale. The cost? Less than $1 per kilogram today. Less than 50 cents within a few years. To understand why that matters, you need to know what hydrogen costs right now.

The vast majority of hydrogen today is made through steam reforming of methane, which sounds technical but is basically heating natural gas to break its molecules apart. It's energy-intensive, it releases CO2 as a byproduct, and it costs between 70 cents and $1.60 per kilogram depending on where you do it. Add carbon capture and storage to make it cleaner, and you're paying 30-50% more. Use renewable electricity to power an electrolyzer instead, which is the greenest current option? Your costs multiply several times over.

Now imagine hydrogen at 50 cents per kilogram, with zero carbon emissions, available right where you need it. Imagine drilling those wells in California, which has enormous ophiolite formations spread across the state.

The implications spiral outward fast. Data centers need baseline power that doesn't fluctuate with solar and wind. Hydrogen fuel cells can provide that. Cheap local hydrogen means no transportation costs, no supply chain fragility, no carbon accounting headaches. It also means data center operators suddenly care deeply about geology in ways they never did before.

This isn't theoretical. Vema already inked a deal with California data centers in December. They completed a pilot project in Quebec. Their first commercial well will reach 800 meters into the earth and produce several tons of hydrogen daily. This is happening now, not in some distant future.

What we're actually looking at is a fundamental restructuring of where computational infrastructure gets built on Earth. The equation that determined data center locations—power availability, cooling water, fiber optic connections, real estate costs, local incentives—just shifted. Geology became a variable that actually matters.

Why Hydrogen Failed and Then Suddenly Didn't

Hydrogen's reputation took a beating because of the automotive industry's spectacular mismanagement. Multiple times, car companies declared "the hydrogen future is now." Multiple times, they couldn't deliver fuel cells at scale, couldn't build supporting infrastructure, couldn't make the economics work. Toyota's Mirai exists. Almost nobody owns one. Honda built the Clarity Fuel Cell. It's discontinued. Even General Motors, which invested tens of billions in hydrogen research, essentially gave up on fuel cell vehicles for consumers.

But here's the thing people miss: hydrogen success never depended on personal vehicles. Industrial users don't care about range anxiety or fuel station networks. They need process heat, feedstock for chemical reactions, and baseline power. They'll literally drill wells to get reliable supply. Oil refineries use hydrogen constantly. Chemical manufacturers can't operate without it. Steel production increasingly relies on hydrogen.

Data centers are the newest industrial user, and they're different from traditional heavy industry. They have money. They have extreme environmental compliance pressure. They have power demands that only grow every year. They also have something refineries don't: flexibility in where they locate. A refinery gets built where oil infrastructure exists. A data center can theoretically go anywhere that has fiber, cooling water, and power.

Vema's timing is perfect because data center operators are desperate. They're struggling to get power contracts. They're facing increasingly strict carbon accounting requirements. They're losing social license in communities that see their presence as exclusively extractive—local jobs don't offset massive electricity demands. Clean, local hydrogen solves multiple problems simultaneously.

The technology itself isn't really new. Geologic hydrogen has existed in certain rock formations for millions of years. Researchers have known about it for decades. The innovation is the drilling and extraction methodology that Vema developed. The business model innovation is saying, "We'll build this right next to you and sell hydrogen directly." That's not revolutionary in a technical sense. It's revolutionary in a practical sense, which matters more.

Understanding the Geology: Why California Becomes a Data Center Hub

Ophiolite formations are the key. They're sections of ancient oceanic crust that got shoved onto continental landmasses by massive tectonic collisions. California has enormous ophiolite zones—the Smartville Block, parts of the Sonoma-Mendocino ophiolite belt, and several others. These aren't small deposits. They're hundreds of kilometers long and dozens of kilometers wide.

What makes ophiolite special for hydrogen production? The iron minerals in these rocks, specifically magnetite and other iron oxides, react with water under heat and pressure to release hydrogen. It's a chemical process that happens naturally in the Earth's crust. Vema accelerates it artificially by injecting water and applying catalysts.

The chemistry is straightforward enough:

This is an oversimplification, but it captures the basic mechanism. At depth, with pressure, heat, and the right catalysts, iron oxides break down water molecules and release hydrogen gas. The hydrogen gets collected through wells, compressed, and transported or used locally.

Vema's pilot project in Quebec demonstrated this works at commercial scale. Their first commercial well will go 800 meters deep. That's not particularly deep by oil and gas standards, but it's deep enough to reach sufficient heat and pressure while staying cost-effective to drill.

The geographic advantage for California is enormous. Most hydrogen production today happens wherever natural gas infrastructure is cheapest. That's often in the Middle East or Texas. Transporting hydrogen is expensive and difficult—it's a light gas that leaks through conventional pipelines, so you need special infrastructure or you have to convert it to ammonia, ship that, and then convert back.

But if you're drilling hydrogen right where a data center exists, transportation becomes a non-issue. You pump it from the ground, cool it slightly, compress it, and feed it into fuel cells on-site. The local hydrogen advantage is genuinely revolutionary for data center economics.

Current Hydrogen Economics: Why 50-Cent Hydrogen Changes Everything

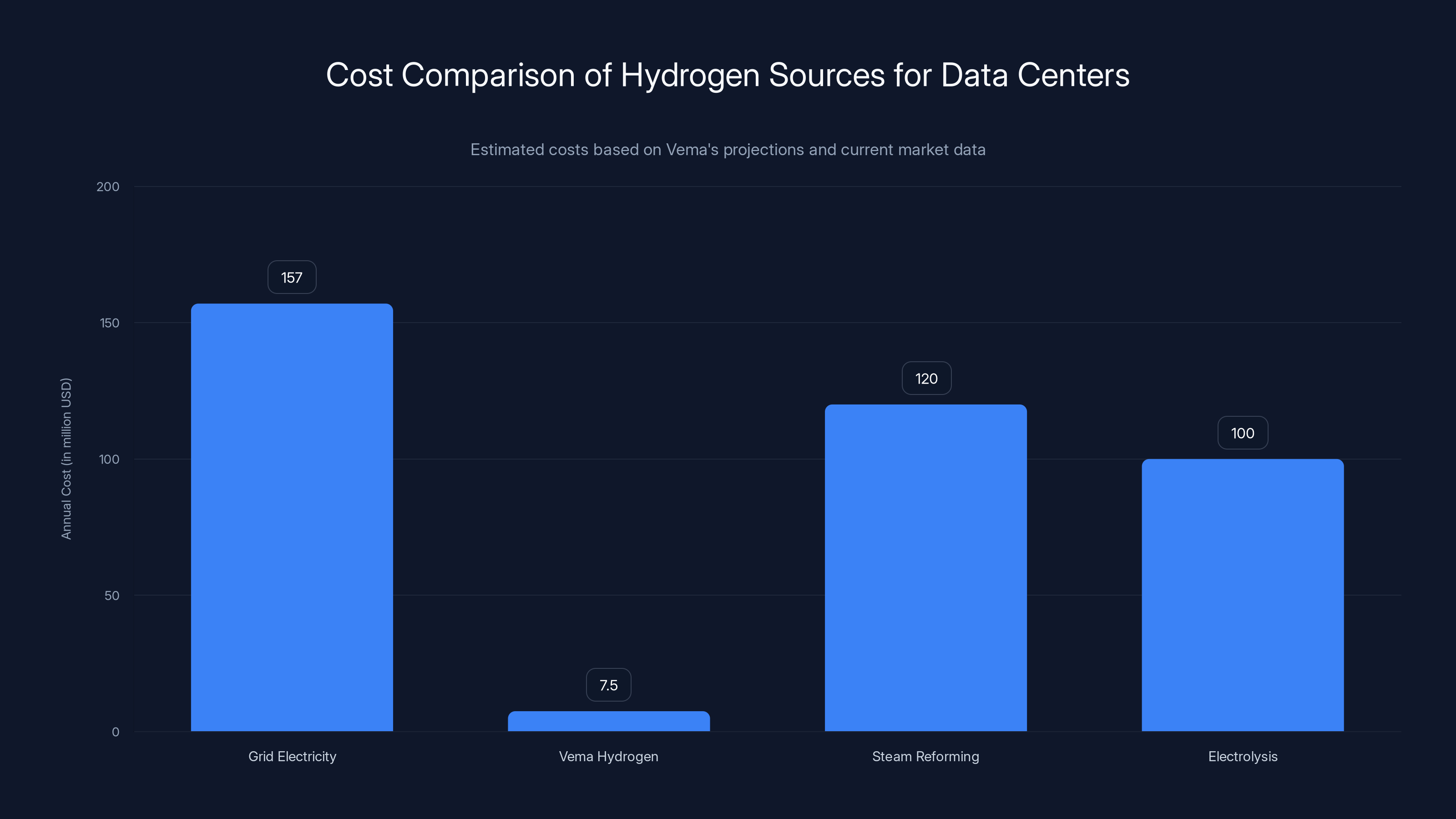

Let's do the math on what cheap hydrogen actually means for data center operations. A typical large data center might consume 100-500 megawatts of power depending on size and workload. Let's work with a moderately large facility at 300 megawatts.

Fuel cells can convert hydrogen to electricity at approximately 50-60% efficiency in real-world applications. That's actually quite good—combustion engines manage around 35%. A 300-megawatt data center running on hydrogen would need roughly:

At 50 cents per kilogram, that's approximately

But the calculation gets more interesting when you factor in carbon accounting. Every gram of coal-fired electricity carries about 1 kilogram of CO2 emissions. Data center operators currently buy carbon offsets at $10-50 per ton depending on methodology and credit quality. If you're avoiding coal-sourced power and instead using carbon-free hydrogen, you're eliminating massive offset costs simultaneously.

Currently, hydrogen from natural gas reforming (the cheapest source) costs 70 cents to $1.60 per kilogram. That's already competitive with grid electricity in many places when you factor in local distribution costs and the value of carbon avoidance. When Vema reaches their 50-cent target, hydrogen becomes cheaper than grid electricity in virtually every market.

That's the inflection point. That's when the geography of computing infrastructure actually changes.

The Data Center Infrastructure Imperative: Why Operators Are Desperate for Solutions

Data center operators are facing unprecedented pressure from multiple directions. AI training and inference demand is exploding exponentially. The power consumption of AI workloads is measured in megawatts, not kilowatts. A single large language model can consume as much electricity as a small town.

Simultaneously, grid operators in traditional data center hubs are tightening power allocation. Texas, Virginia, and other traditional data center regions are hitting grid capacity limits. Environmental regulations are tightening carbon accounting requirements. Local communities are increasingly hostile to new data center construction because they see massive electricity demand with minimal local employment.

There's also the geopolitical angle. Taiwan produces most of the world's advanced chips. China's making aggressive moves toward energy independence and computational dominance. The U. S. government has made clear it wants computational infrastructure distributed across the country, not concentrated in a few coastal hubs. Any technology that enables data center deployment in previously infeasible locations becomes strategically important.

Vema's hydrogen isn't just an energy solution. It's an infrastructure solution that addresses multiple problems simultaneously. Local hydrogen means:

- Decarbonized power: Zero emissions, no carbon offset costs, regulatory compliance built-in

- Supply reliability: Not dependent on grid stability or fossil fuel prices

- Location flexibility: Data centers can move to ophiolite regions rather than traditional power hubs

- Geographic distribution: Aligns with U. S. national security goals for distributed computing

- Scalability: Ophiolite formations are worldwide, so this works in multiple countries

Vema's deal with California data centers makes strategic sense on every axis. California has ophiolite formations. California has massive data center demand. California has the strictest carbon regulations in North America. California also has the tech industry's largest concentration, so proximity to customers matters.

Vema's Technical Approach: How They Extract Hydrogen at Scale

The actual drilling and extraction process is more sophisticated than the description suggests. Vema doesn't just drill a hole and collect hydrogen that naturally seeps out. They engineer the geological formations themselves.

Their process involves several stages:

1. Well Drilling and Site Selection They start by identifying ophiolite formations with the right mineral composition and depth characteristics. Not all ophiolite is equally suitable—they need formations with sufficient porosity and permeability, plus access to groundwater. The first commercial well goes to 800 meters, which places it in formations with significant geothermal gradient but isn't so deep that drilling costs become prohibitive.

2. Stimulation Injection Once the well is drilled, Vema injects water along with catalysts and possibly other reagents into the formation. The catalysts facilitate the chemical reactions that generate hydrogen from the iron oxides. This isn't about fracturing rocks hydraulically—it's a chemical engineering problem, not a mechanical one.

3. Heat and Pressure Application The geothermal gradient at depth provides most of the heat naturally, though Vema may apply additional heat from the surface. The pressure comes from the weight of overlying rock. The combination of heat, pressure, water, and catalysts drives hydrogen generation.

4. Collection and Extraction As hydrogen gas is generated, it fills pore spaces in the rock formation. The pressure differential causes it to flow toward the wellbore, where it gets collected through pumping equipment. The hydrogen is then brought to the surface, dehydrated, compressed, and either stored or fed directly to fuel cells.

5. Quality Control The extracted hydrogen needs to meet fuel cell specifications. They remove water vapor, particulates, and ensure purity standards. This is more straightforward than hydrogen from other sources because it's not mixed with CO2 or other byproducts that require separation.

Vema's proprietary innovation lies in optimizing this entire process to keep costs down. They've likely developed specific injection protocols, catalyst formulations, and extraction methodologies that maximize hydrogen yield per well while minimizing operational costs. They're not publishing detailed specifications, so the exact technical advantages remain proprietary.

What's observable is that their costs are reportedly heading toward 50 cents per kilogram, and they've already proven the process works at pilot scale. That's sufficient evidence that the technology is viable, even if the exact engineering details stay secret.

The Global Hydrogen Market: Context and Demand

Vema isn't entering a void. The global hydrogen market is already substantial and growing rapidly. Industrial users consume roughly 70 million tons of hydrogen annually. That's enormous. Almost all of it comes from natural gas reforming, which produces about 830 million metric tons of CO2 annually—roughly 2% of global emissions.

The pressure to decarbonize hydrogen is intense. Governments everywhere are setting targets for "green hydrogen"—hydrogen produced from renewable electricity and electrolysis, or in Vema's case, from geological sources without fossil fuel inputs. The International Energy Agency estimates that reaching net-zero carbon emissions by 2050 requires hydrogen production to increase sixfold, while simultaneously shifting almost entirely away from fossil fuels.

That's a multi-trillion-dollar opportunity. Every major oil company, every major industrial gases company, every startup with hydrogen credibility is competing. But the landscape is still emerging. There's no dominant technology yet. Steam reforming with carbon capture is advancing. Electrolysis is improving rapidly. But none of these approaches have achieved the 50-cent-per-kilogram target yet.

Vema claiming they'll reach 50 cents is a big statement in that context. If true, it's genuinely cheaper than any existing large-scale hydrogen source. That would make them the economics leader for hydrogen production.

The data center use case is perfect for launching that advantage. Data centers have massive, predictable, baseload demand. They have high environmental standards and compliance budgets. They can absorb the capital cost of on-site hydrogen extraction infrastructure because the operating cost advantage justifies it. Most importantly, they can locate anywhere geology permits, which means Vema can build wells at customer sites rather than competing in the bulk hydrogen market.

Carbon Accounting and Environmental Compliance: The Regulatory Tailwind

Environmental regulations are becoming the silent driver of hydrogen adoption. The EU's Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism is starting to tax carbon-intensive imports. California's cap-and-trade system is tightening every year. Corporate carbon accounting standards are intensifying. Microsoft, Google, and Amazon have all made public commitments to zero-carbon operations by specific dates.

Meeting those commitments with grid electricity is increasingly difficult. Renewable energy is growing, but it's intermittent. Battery storage is expensive. Nuclear takes years to build. Hydrogen produced from geological sources, with zero carbon emissions, fits perfectly into that requirement.

Moreover, Scope 2 emissions (purchased electricity) reporting is increasingly scrutinized. Data centers want to show that their power comes from decarbonized sources. Hydrogen from Vema's wells generates exactly that narrative. It's verifiable, traceable, and genuinely zero-carbon.

From a regulatory standpoint, engineered mineral hydrogen from ophiolite formations is also relatively uncontroversial. It doesn't involve fracking, which generates local opposition. It doesn't require rare earth elements or novel manufacturing. It's essentially just drilling and extracting a naturally occurring resource more efficiently than before.

That regulatory tailwind matters more than most technologists appreciate. Regulations are shifting to make cheap, clean hydrogen increasingly valuable and hydrogen from fossil fuels increasingly expensive. That policy slope is structural, not cyclical.

Global Ophiolite Distribution: Where Data Centers Will Actually Move

Vema's focus on California makes sense, but the global opportunity is larger. Ophiolite formations exist on multiple continents. Understanding where they occur geographically is essential to predicting where data center expansion will happen.

Ophiolite belts run along ancient collision zones where oceanic crust got pushed up during continental plate interactions. The major deposits include:

North America: California's Smartville Block and Sonoma-Mendocino Belt are the most significant, but ophiolite also occurs in Washington state, British Columbia, and parts of Quebec. Vema's pilot in Quebec demonstrates their technology works in North American ophiolite beyond California.

Mediterranean Region: Greece, Turkey, Cyprus, and the Balkans have extensive ophiolite formations. If Vema or competitors can scale globally, European data center operators will likely follow.

Middle East and Central Asia: Oman has some of the world's largest exposed ophiolite formations. The Tethyan ophiolite belt extends through Iran, Afghanistan, and the Hindu Kush. This matters because the Middle East is already a hydrogen production hub. If engineered mineral hydrogen works there, it could completely restructure Middle Eastern energy economics.

Southeast Asia: The Philippines, Indonesia, and surrounding regions have ophiolite formations. Given the region's explosive data center growth (supporting the Asian tech industry), this could be strategically significant.

Africa: Parts of East Africa have ophiolite deposits, though exploration is less advanced. As Africa builds out computational infrastructure, this could become relevant.

The geographic distribution matters because it suggests hydrogen availability could eventually exceed demand in specific regions. When that happens, hydrogen becomes an export commodity. That's when the real economic restructuring begins.

For now, Vema's strategy is smart: dominate where demand and geology intersect first. California and the U. S. Northeast have both. But their long-term opportunity scales to anywhere with ophiolite and power demand.

Data Center Power Economics: The Full Comparison

Let's compare the total cost of electricity for a data center under different scenarios. We're looking at a 300-megawatt facility operating continuously.

Grid Electricity (Coal/Mixed Sources) Typical U. S. wholesale electricity:

Hydrogen from Natural Gas (Current Market) Hydrogen at

Vema Hydrogen at 50 Cents per Kilogram Annual hydrogen cost: 9.855 million kg ×

Compare that across scenarios:

- Grid electricity with full carbon accounting: $157 million annually

- Hydrogen from natural gas: $47-57 million annually

- Vema hydrogen: $7-8 million annually

The savings are stunning. Even accounting for capital costs of hydrogen extraction infrastructure and fuel cells, the operating cost advantage is so large that payback happens in a few years.

That's why data centers are already signing deals. This isn't speculative. The math is too compelling.

Infrastructure Requirements: What Data Centers Actually Need

Adopting hydrogen isn't just about drilling a well and plugging in. Data centers need specific infrastructure to convert Vema's hydrogen into usable electricity.

Hydrogen Fuel Cells Stationary fuel cells for power generation exist from multiple manufacturers. Companies like Ballard Power Systems, Plug Power, and others produce megawatt-scale fuel cell stacks designed for industrial applications. These convert hydrogen and oxygen into electricity and water through electrochemical reactions. Real-world efficiency is 50-60%, which is genuinely competitive with other generation methods.

A 300-megawatt data center using hydrogen for baseline power might use 150-200 megawatts of fuel cells for continuous operation, with the remainder from grid interconnection for redundancy and peak loads.

Hydrogen Storage and Handling Hydrogen is difficult to store because it's a small molecule that leaks through most materials. Options include:

- Compressed gas storage in specialized tanks

- Liquefied hydrogen (requires cryogenic cooling)

- Absorption in metal hydrides (complex but dense)

- Underground cavern storage (if available and permitted)

For a data center co-located with hydrogen production, storage is less critical because hydrogen can be generated and used continuously, but some buffer capacity is still needed for operational flexibility.

Fuel Cell Balance of Plant Fuel cells generate significant heat as a byproduct. Water-cooling systems can capture and use that heat for facility heating or other industrial processes. This cogeneration efficiency further improves overall economics.

Grid Integration Data centers need to remain connected to the grid for redundancy. The fuel cell system becomes a form of distributed generation that can operate independently if the grid fails but typically works in parallel with grid power.

All of this is proven technology. It's not cutting-edge research. The novelty is simply using hydrogen from ophiolite formations as the fuel source, and having those formations occur where data centers want to locate.

Competitive Responses and Market Dynamics

Vema isn't operating in isolation. Other hydrogen production approaches are advancing rapidly. Electrolysis efficiency is improving every year. Carbon capture on natural gas reforming is becoming more economical. There's genuine competition across multiple technological approaches.

But Vema has several advantages:

Cost Structure: Their pathway to 50-cent hydrogen is extraordinarily cheap compared to alternatives. Electrolysis struggles to reach that price. Reforming with carbon capture adds 30-50% cost premiums.

Geography: Ophiolite formations exist naturally. They don't require rare earth elements or new manufacturing. They're widespread enough that the supply can scale to meet demand in multiple regions.

Proximity: Unlike centralized hydrogen production, Vema drills wells at customer sites. That eliminates transportation costs and supply chain fragility.

Regulatory Alignment: Zero-carbon hydrogen addresses environmental compliance directly without requiring additional carbon offset purchases.

The competitive response from other players will likely include:

- Electrolysis companies improving efficiency and reducing costs

- Reforming companies developing better carbon capture

- Oil majors moving hydrogen production to compete

- Startups exploring other geological hydrogen sources

But none of those approaches have the combination of low cost, zero carbon, local production, and proven scalability that Vema's approach offers.

The market dynamics suggest that Vema will face competition, but the addressable market is so large that multiple players can succeed. Global industrial hydrogen consumption is 70 million tons annually. Even if Vema captures 1-2% of that market, it's a multibillion-dollar business.

Scaling Challenges and Timeline Realities

Vema's timeline is ambitious but credible. They've completed a pilot project. Their first commercial well is planned for next year. They're targeting several tons of hydrogen daily from early wells.

But scaling to supply meaningful data center demand involves serious challenges:

Permitting and Regulatory Approval Drilling wells requires environmental impact assessments, groundwater permits, and local zoning approvals. California's permitting process is notoriously complex. Even with a strong business case, approval could take 1-2 years per well.

Geological Variability Ophiolite formations vary in composition and hydrogen-generating capacity. Not every well will perform equally. Some will exceed projections; others will underperform. Site selection and characterization become critical.

Production Optimization The chemistry of hydrogen generation from mineral oxidation still has optimization opportunities. Vema likely hasn't maxed out efficiency yet. Production rates might improve faster than expected, or they might hit unexpected constraints.

Capital Requirements Drilling infrastructure, fuel cells, handling equipment, and facilities require significant upfront investment per site. Vema needs capital to scale to multiple wells simultaneously.

Supply Chain They need materials, equipment, specialized drilling contractors, and engineering talent. If multiple hydrogen projects scale simultaneously, supply chains could tighten.

Realistic timelines probably show meaningful hydrogen production (hundreds of tons daily, not thousands) within 3-5 years. Scaling to significantly displace grid electricity for data centers probably takes 7-10 years.

But even that timeline is aggressive compared to other infrastructure projects. A nuclear power plant takes 10-15 years from site selection to operation. A major transmission line takes 5-10 years. Vema's parallel deployment of multiple wells could happen faster than any comparable energy infrastructure.

Geopolitical Implications and National Security

Hydrogen production from ophiolite has geopolitical dimensions that extend beyond simple energy economics.

Currently, hydrogen production concentrates in regions with cheap natural gas: the Middle East, Russia, and the United States. That concentration creates dependencies. If Middle Eastern politics destabilize or Russia tightens export controls, hydrogen supply becomes fragile.

Engineered mineral hydrogen from distributed ophiolite deposits disrupts that concentration. If Vema's approach scales globally, hydrogen becomes available everywhere ophiolite exists. That's less dependent on geopolitics and more dependent on geology.

For the United States, this aligns perfectly with national security objectives. Distributed data center infrastructure reduces dependence on centralized power grids, which are potential attack targets. Local hydrogen production reduces energy import dependence. This fits into broader strategic autonomy conversations.

For data center operators specifically, energy independence from grid fragility and geopolitical supply disruptions becomes a competitive advantage. That's real business value, separate from carbon considerations.

The geopolitical angle also explains why governments might support Vema's scaling. Investment tax credits, permitting fast-tracks, and regulatory support for clean hydrogen all make sense from a strategic perspective, not just environmental policy.

The Data Center Location Shift: A Restructuring of Computing Geography

If Vema achieves their cost targets and scales successfully, the geographic distribution of data centers shifts fundamentally.

Currently, data center locations are driven by:

- Power availability and cost

- Cooling water resources

- Fiber optic connectivity

- Real estate costs

- Local incentive packages

- Proximity to population centers (for latency reasons)

If cheap hydrogen becomes available, power cost becomes less of a decision factor (it's so cheap that it stops being limiting). That opens new geographies to data center development.

Opphiolite formations become location-determining factors. California gets data centers built in rural areas where ophiolite exists. Quebec becomes an attractive expansion hub. Parts of the Mediterranean become viable. Regions that currently lack hydroelectric power or cheap fossil fuel access suddenly become competitive.

This restructuring takes time—probably a decade or more—but it's directional. Over the long term, data center geography reorganizes around ophiolite deposits and fiber infrastructure, rather than around fossil fuel availability.

The economic implications are profound. Rural areas with ophiolite formations become valuable infrastructure hubs. Communities get construction jobs, skilled operational positions, and ongoing industrial presence. Real estate values increase. Tax bases expand.

But there are downsides too. Communities in geologically infeasible regions miss out on data center development. The environmental and social costs of large-scale drilling and hydrogen extraction become real concerns in affected areas. Groundwater impacts need monitoring.

This is classic technological disruption at geographic scale. Winners and losers emerge based on geology rather than historical accident.

Investment Opportunities and Market Trends

Vema's model has attracted capital because venture investors see a genuine business opportunity. But the investment case is broader than just Vema.

Companies benefiting from cheap hydrogen infrastructure include:

- Data center operators (lower power costs)

- Hydrogen equipment manufacturers (fuel cells, compressors, storage)

- Rock drilling specialists (more well development)

- Computing hardware companies (data centers can expand into new regions)

- Regional power utilities (distributed generation changes their business model)

Companies disrupted by cheap hydrogen include:

- Utility companies (centralized power generation becomes less attractive)

- Fossil fuel companies (hydrogen from geology undermines natural gas advantage)

- Energy-dependent data center operators in unfavorable geographies (cost disadvantage)

The investment thesis for hydrogen infrastructure broadly is strong. Global hydrogen demand will grow. Carbon pricing will make fossil fuels expensive. Engineered mineral hydrogen offers a cost advantage over alternatives. That's a multi-decade trend.

Vema specifically is betting that they can achieve their cost targets, navigate permitting successfully, and scale before competitors catch up. That's a meaningful bet with real downside risk, but the upside is enormous if they succeed.

For data center operators, the calculus is simpler: if cheap hydrogen becomes available, their power economics improve dramatically. That's worth paying for, investing in, and locating facilities around. The business case is compelling even with moderate probability of success.

FAQ

What is engineered mineral hydrogen and how does it differ from other hydrogen sources?

Engineered mineral hydrogen is produced by injecting water into iron-rich rock formations (ophiolite) at depth, applying heat and pressure with chemical catalysts, which causes the rocks to release hydrogen gas naturally. This differs fundamentally from steam reforming of methane (which uses fossil fuels and produces CO2) and electrolysis (which requires electricity). Vema's process is cleaner than reforming, cheaper than electrolysis, and requires no fossil fuel inputs, making it genuinely zero-carbon hydrogen at scale.

How does Vema's hydrogen extraction process work at a technical level?

Vema drills wells into ophiolite formations, typically 800 meters deep, where they inject water and catalysts. The combination of geothermal heat (naturally available at depth), pressure from overlying rock, and chemical catalysts drives a reaction where iron oxides in the rock release hydrogen molecules. The hydrogen gas flows toward the wellbore, gets extracted to the surface, dehydrated, compressed, and either stored or fed directly into fuel cells for electricity generation. The process is essentially accelerating a natural geological phenomenon that occurs continuously in the Earth's crust.

What are the economic advantages of using hydrogen for data center power?

Vema claims they'll produce hydrogen for 50 cents per kilogram eventually, which is cheaper than any current large-scale hydrogen source. For a 300-megawatt data center, this could reduce annual power costs from

What are the environmental and regulatory benefits of hydrogen fuel cells in data centers?

Hydrogen fuel cells produce only electricity and water—no greenhouse gas emissions or pollutants. This directly satisfies environmental compliance requirements, corporate carbon commitments, and regulatory carbon accounting standards. Unlike grid electricity, which requires carbon offset purchases to achieve neutrality, hydrogen from ophiolite is genuinely zero-carbon without offset dependencies. The regulatory environment is actively favoring clean hydrogen through carbon pricing and renewable energy mandates, creating structural support for Vema's business model.

Where in the world are ophiolite formations located, and could this technology scale globally?

Ophiolite formations occur globally along ancient tectonic collision zones. Significant deposits exist in California, the Mediterranean (Greece, Turkey, Cyprus), the Middle East (Oman), Central Asia, Southeast Asia, and parts of Africa. Vema's technology could potentially work anywhere ophiolite exists, which means hydrogen production could eventually be available across multiple continents. This geographic distribution is a strategic advantage because it reduces dependence on centralized fossil fuel production regions and enables distributed data center development based on local geology.

What is the timeline for Vema to scale from pilot projects to commercial operations supplying multiple data centers?

Vema has completed a pilot project in Quebec and plans their first commercial well for next year, targeting several tons of hydrogen daily. Scaling to supply meaningful data center demand probably requires 3-5 years for multiple wells and facility construction. Permitting and regulatory approval could add 1-2 years per site in complex jurisdictions like California. Full industrial scaling across multiple regions likely requires 7-10 years. This timeline is aggressive compared to traditional energy infrastructure but reflects Vema's parallel drilling strategy rather than sequential development.

How does hydrogen cost compare to current data center power sources across different scenarios?

Grid electricity (mixed sources) costs roughly

What competitive threats does Vema face from alternative hydrogen production methods?

Electrolysis powered by renewable electricity is improving rapidly in efficiency and cost reduction, though it still struggles to reach 50-cent targets. Reforming with carbon capture is advancing, but adds 30-50% cost premiums. Oil majors are investing in hydrogen infrastructure. But Vema's combination of low cost, genuine zero-carbon, local production, and geographic distribution creates advantages that are difficult to replicate. Competitors pursuing other pathways will likely succeed in their own niches, but Vema's model offers a unique advantage proposition for data centers, particularly in regions with ophiolite deposits.

What are the main scaling challenges Vema will face as they move from pilot to commercial operations?

Key challenges include navigating complex permitting processes (particularly in California), managing geological variability across different ophiolite formations, optimizing hydrogen production chemistry, securing necessary capital for multiple simultaneous well developments, and building supply chains for specialized drilling equipment and fuel cell systems. Regulatory approval could take 1-2 years per site. Success requires not just technical execution but also demonstrated reliability and cost performance at commercial scale, which takes time to prove.

How does Vema's hydrogen fit into broader decarbonization strategies for data centers and computing infrastructure?

Data centers are under intense pressure to reduce carbon footprints while managing exponential growth in computing demand. Hydrogen from ophiolite offers a genuinely zero-carbon baseline power source that's cheaper than grid alternatives and enables distributed data center geography based on geology rather than power availability. This fits perfectly into broader decarbonization goals, cloud infrastructure resilience strategies, and geopolitical objectives around reducing centralized energy dependencies. For corporations committed to net-zero targets, cheap hydrogen from Vema becomes a strategic tool for achieving compliance while maintaining competitive infrastructure costs.

Engineered mineral hydrogen offers a cost-effective alternative at $0.75 per kg, significantly cheaper than electrolysis and competitive with steam reforming. Estimated data.

Conclusion: The Quiet Revolution in Data Center Power

The hydrogen revolution in data centers isn't going to be flashy. There won't be press conferences announcing a breakthrough. Instead, you'll see quiet permitting approvals for wells in rural California. You'll see data center operators announcing new facility locations in geologically unexpected places. You'll see energy costs dropping in financial disclosures without explanation to investors who don't understand ophiolite formations.

That's how infrastructure transitions actually happen. Not through dramatic announcements, but through economic incentives so compelling that they reshape entire industries over a decade.

Vema's engineered mineral hydrogen represents that kind of inflection point. If they execute at scale—and there's genuine reason to think they can—the geography of computing infrastructure reorganizes. Data centers stop concentrating wherever power is cheapest through historical accident and instead cluster where geology permits cheap hydrogen extraction.

But the real impact is deeper than geography. It's about energy independence, carbon compliance, and computing infrastructure economics. When power costs become nearly trivial, data center operators can focus on fiber connectivity, cooling infrastructure, and talent availability. When carbon compliance becomes automatic, companies stop spending money on offset programs. When power supply becomes independent of grid stability, data centers become more resilient to supply disruptions.

Those are profound changes in how computing infrastructure actually works. And they're driven by rocks, water, and chemical reactions that have been occurring naturally in the Earth's crust for millions of years. We're just starting to harness them intentionally.

The next decade will show whether Vema can execute at scale. But the direction is clear. Cheap local hydrogen from ophiolite formations will drive data center location decisions. The data center industry will reorganize around geology. And computing infrastructure—the physical substrate of the modern digital economy—will become distributed, resilient, and genuinely zero-carbon.

That's worth paying attention to, not because it's flashy, but because it's fundamental infrastructure change with global implications.

Vema's engineered mineral hydrogen could reduce data center power costs to $7-8 million annually, significantly lower than grid electricity and other hydrogen sources. Estimated data.

Key Takeaways

- Vema's engineered mineral hydrogen extraction from ophiolite rock formations could produce hydrogen at 50 cents per kilogram, cheaper than any current large-scale alternative

- Hydrogen-powered data centers could reduce annual power costs from 7-8 million for a 300-megawatt facility while achieving zero-carbon compliance

- Ophiolite formations exist globally along tectonic collision zones, meaning hydrogen production could eventually be available worldwide across multiple continents

- Data center operators are signing deals with Vema because the economics are compelling today, not speculative, representing genuine infrastructure cost disruption

- Long-term data center geography will reorganize around geology—specifically ophiolite deposits—rather than historical power availability patterns

Related Articles

- Thermodynamic Computing: The Future of AI Image Generation [2025]

- Samsung RAM Prices Doubled: What's Causing the Memory Crisis [2025]

- Reused Enterprise SSDs: The Silent Killer of AI Data Centers [2025]

- Neurophos Optical AI Chips: How $110M Unlocks Next-Gen Computing [2025]

- The Hidden Terawatt: Why 1TW of Geothermal Power Is Being Ignored [2025]

- AI Storage Demand Is Breaking NAND Flash Markets [2025]

![Cheap Hydrogen Is Reshaping Data Center Infrastructure [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/cheap-hydrogen-is-reshaping-data-center-infrastructure-2025/image-1-1770122190299.jpg)