The Venture Capital Paradox Nobody Talks About

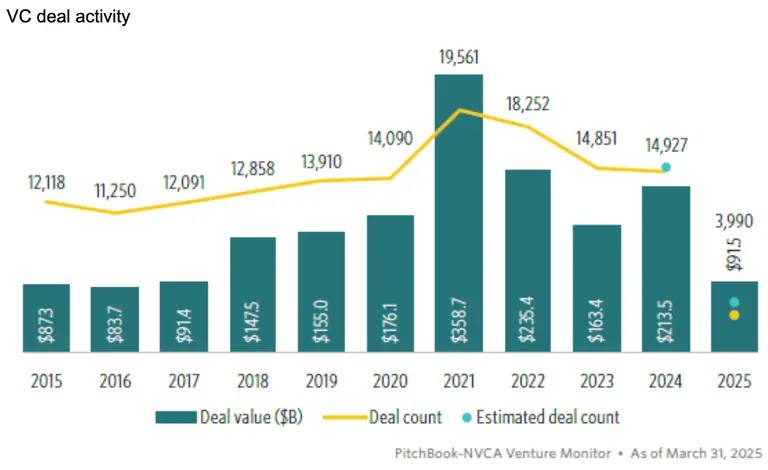

Silicon Valley moves in waves. Right now, everyone's obsessed with one thing: mega-rounds and AI everything. The numbers are insane. Series B companies raising $50 million like it's pocket change. Seed funds chasing trillion-dollar market opportunities in dorm rooms.

But here's what's actually happening beneath the hype. Thousands of competent founders with proven business models are basically invisible to most VCs. Not because they're bad founders. Not because their ideas suck. They're invisible because they don't fit the narrative du jour.

That's the exact problem Stacy Brown-Philpot spotted when she launched Cherryrock Capital in 2024. And she didn't just identify the problem—she doubled down on it while the rest of the industry was looking the other way.

Before you dismiss this as some diversity-washing nonprofit play, understand what's actually happening. Brown-Philpot spent a decade at Google, served as CEO of Task Rabbit, and watched that company get acquired by IKEA. She's not some idealistic first-time investor. She's an operator who understands what makes companies actually succeed.

What she built at Cherryrock is a deliberate rebellion against the current VC playbook. Concentrated bets. Measured deployment. Patient capital. In an industry that's obsessed with speed, she's gone the opposite direction. And after one year, the initial results suggest she might be onto something bigger than anyone expected.

Who Actually Needs Access to Capital Right Now?

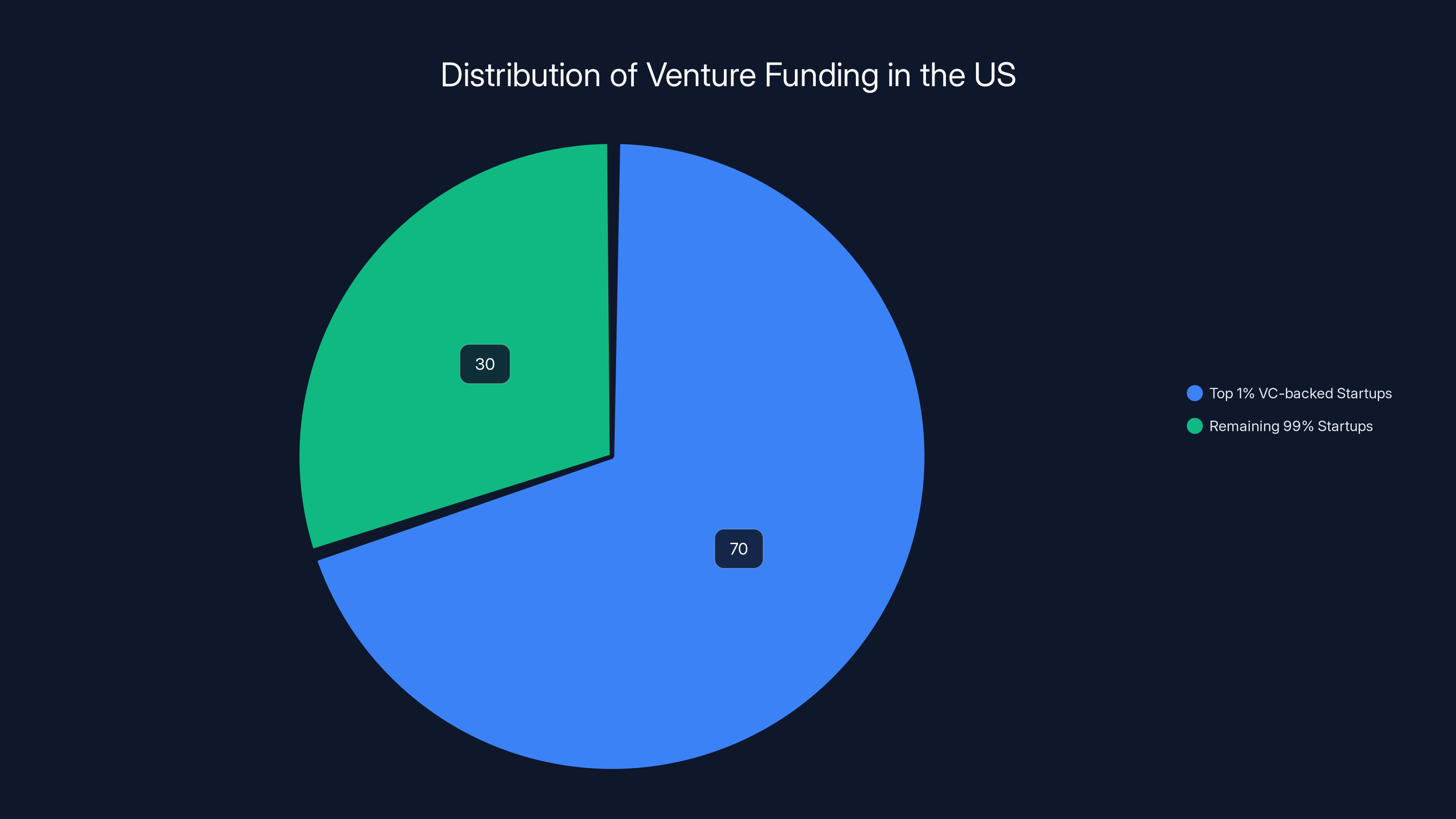

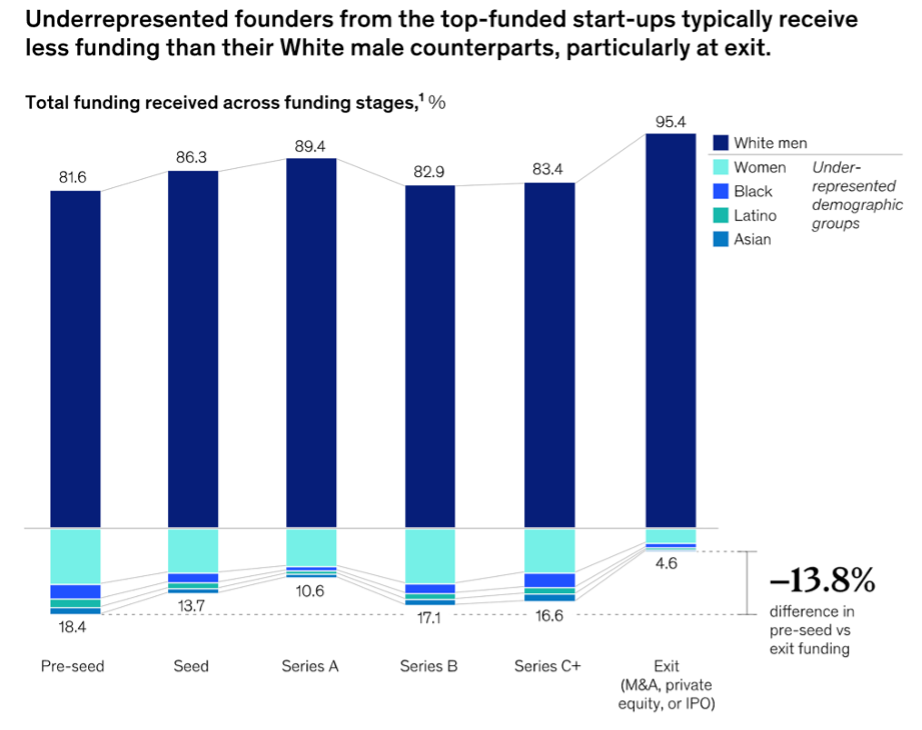

Let's start with something basic: the math is broken. PwC data shows that the top 1% of VC-backed startups consume about 70% of venture funding in the US. The remaining 99% fight for scraps.

But here's what most people get wrong. Those scraps aren't going to bad companies. They're going to companies that are growing, profitable, or close to it. Companies with real traction. Companies that have already survived their first three years.

Series A and B companies are in a peculiar position. They've cleared the tough hurdle—they've proven there's a real market for what they're building. They have revenue. They have retention. They have product-market fit or they're close enough to taste it.

But they're also invisible to mega-funds. A

Where does Series A and B capital actually come from in this scenario? Sometimes angel investors. Sometimes founders' own pockets. Sometimes slower institutions that the cool kids in Sand Hill Road don't talk about publicly.

Brown-Philpot's thesis is that this gap isn't temporary. It's structural. And it creates opportunity.

When she was on the investment committee for Soft Bank's Opportunity Fund (a $100 million vehicle launched in 2020), she got a front-row seat to how many qualified founders were getting passed on. The fund was specifically designed to back underrepresented entrepreneurs—and even with that mandate, the pipeline was massive.

Soft Bank eventually divested the Opportunity Fund in late 2023. But Brown-Philpot didn't see that as a signal to move on. She saw it as a signal to move in.

The top 1% of VC-backed startups consume about 70% of venture funding, leaving the remaining 99% to compete for the rest. Estimated data.

The Cherryrock Model: Concentrated Bets and Patient Money

When most venture funds launch, they set a number. "We're writing 100 checks this fund cycle." "We're targeting 50 to 80 investments." More bets feel safer. More bets mean more chances to hit a unicorn.

Cherryrock did the opposite. Brown-Philpot publicly committed to 12 to 15 investments from the debut fund. That's it. That's the entire portfolio.

Why? Because concentration forces you to care. When you're writing 100 checks, you can afford to be wrong on 90 of them. When you're writing 12 checks, each one needs to get your full operational attention.

The fund closed in February 2025 with backing from major institutional players. JPMorgan is an LP. Bank of America is an LP. You don't get those names on your cap table by being a charity. These are financial institutions that "expect to generate a return," as Brown-Philpot put it herself.

Also backing the fund: Goldman Sachs Asset Management, Mass Mutual, Top Tier Capital Partners, and Melinda Gates's Pivotal Ventures.

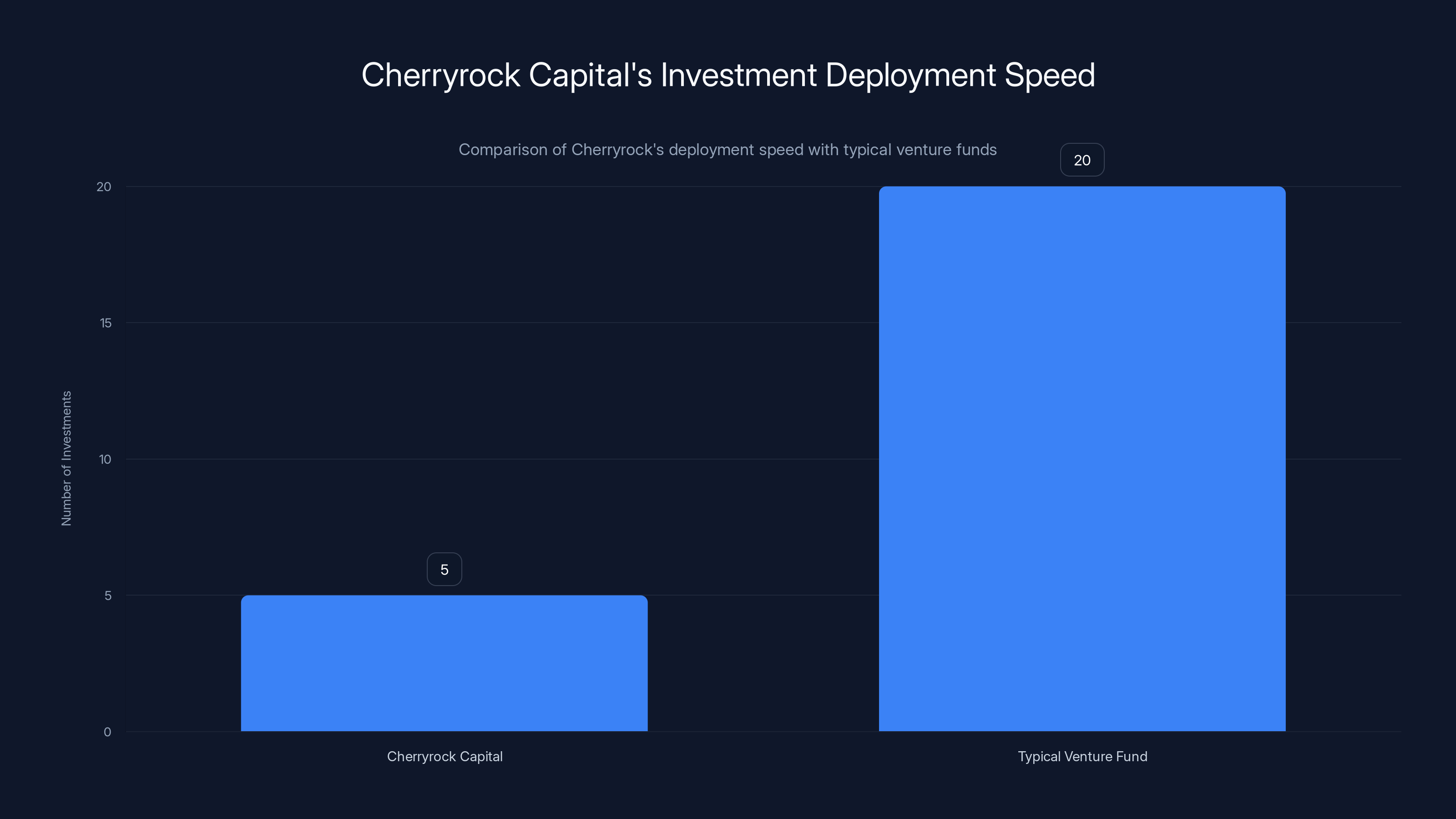

One year in, with the fund closed, Cherryrock had backed exactly five companies. Five. At a clip where most funds would have deployed 20-30 checks already.

That's not slow. That's deliberate. That's the opposite of the frantic capital deployment most VCs do because their LPs are breathing down their necks about deployment timelines.

Brown-Philpot's cofounder is Saydeah Howard, who spent nine years at venture firm IVP. That's someone who knows the operational side of what makes portfolio companies succeed. Together, they're deliberately moving slow, which in venture is essentially moving fast in the opposite direction.

Cherryrock Capital deploys investments at a significantly slower pace, with only 5 investments in the first year compared to the typical 20 by other venture funds. Estimated data.

The Portfolio: What Actually Gets Funded?

Brown-Philpot's thesis on "underinvested founders" is careful language, especially in 2025. The political climate has made the word "diversity" itself controversial in VC circles.

But let's look at what she's actually backing. The portfolio tells the story better than any statement.

Coactive AI: Multimodal Infrastructure for Media

One of the first bets was Coactive AI, led by Cody Coleman. Coleman holds advanced degrees from both MIT and Stanford—with a background in philosophy and engineering. The company provides multimodal AI infrastructure specifically for media and entertainment.

This matters because media companies are absolutely panicking about AI. Studios, content platforms, production houses—they're all figuring out how to use AI without destroying their existing content strategies or getting sued into oblivion.

Coactive is solving a specific technical problem in that panic. You need infrastructure that actually works for multimodal workflows (video, text, audio). You need something that integrates with existing production pipelines. You need compliance and governance baked in from the start.

Not flashy. Not a consumer play. Not a billion-dollar overnight story. But essential infrastructure for one of the largest industries in the world as it figures out AI integration.

Cherryrock led the Series B round alongside Emerson Collective. That's exactly the kind of co-investment that suggests serious institutional validation alongside patient capital.

Vitable Health: On-Demand Healthcare for Gig Workers

The second investment that Brown-Philpot publicly discussed was Vitable Health, founded by Joseph Kitonga. Kitonga is a Thiel Fellow and Y Combinator alum.

Vitable provides on-demand primary care health insurance targeted at employers and hourly workers. This is brilliant for one simple reason: Brown-Philpot knows this customer base intimately.

When she was CEO of Task Rabbit during its final years as an independent company, she lived and breathed the gig economy problem. Task Rabbit workers are independent contractors. They have variable income. They have no employer-sponsored health insurance. They're underinsured or uninsured.

That's a massive market opportunity that traditional insurance companies ignore because the margins look bad when you're dealing with variable-income workers. But Kitonga figured out a model that works.

He's "the exact kind of founder that we want to back," Brown-Philpot said. Why? Because he's solving a real problem for people he understands. Because he's coming from distribution (Y Combinator network, Thiel backing). Because the problem has been solved before in other ways, so you know it's real, but nobody's gotten the model right yet.

The Political Landscape: DEI in Venture During a Conservative Shift

Here's where things get interesting and slightly uncomfortable. When Brown-Philpot launched Cherryrock, the political environment was shifting. Trump's first term had ended, but anti-DEI sentiment had intensified. Major corporations were backing away from diversity pledges. Lawsuits against affirmative action had been won.

Venture capital, being very attuned to political risk, started adjusting language. Nobody wanted to be the next target of activist campaigns about "woke capitalism."

Brown-Philpot's response? Total calm. She addressed the question head-on: "It doesn't change the pitch at all. When we look at the people who decided to back Cherryrock, like JPMorgan and Bank of America, these are financial institutions who expect to generate a return. Our job as investors is to do just that."

That's a genuinely clever framing. She's not saying she's doing diversity work. She's saying her LPs are professional investors who expect returns. And they backed her thesis. The end.

Meanwhile, an interesting regulatory shift happened that actually helps her position. California passed a new diversity reporting law that requires VC firms with California nexus to report demographic data on their portfolio companies' founding teams. First deadline: April 2025.

Unlike the corporate diversity initiatives that have faced legal challenges, this law focuses on transparency, not mandates. No quotas. Just reporting.

For a firm like Cherryrock that's already tracking and prioritizing investments in diverse founders, compliance is what Brown-Philpot calls "table stakes." You don't get in trouble for reporting data. You get in trouble if you're not ready to report it.

So while other firms are nervously wondering how to address this requirement, Cherryrock is already ahead. The firm has been structured from day one to track these metrics. When the reporting deadline hits, they'll probably be one of the cleanest examples of the data.

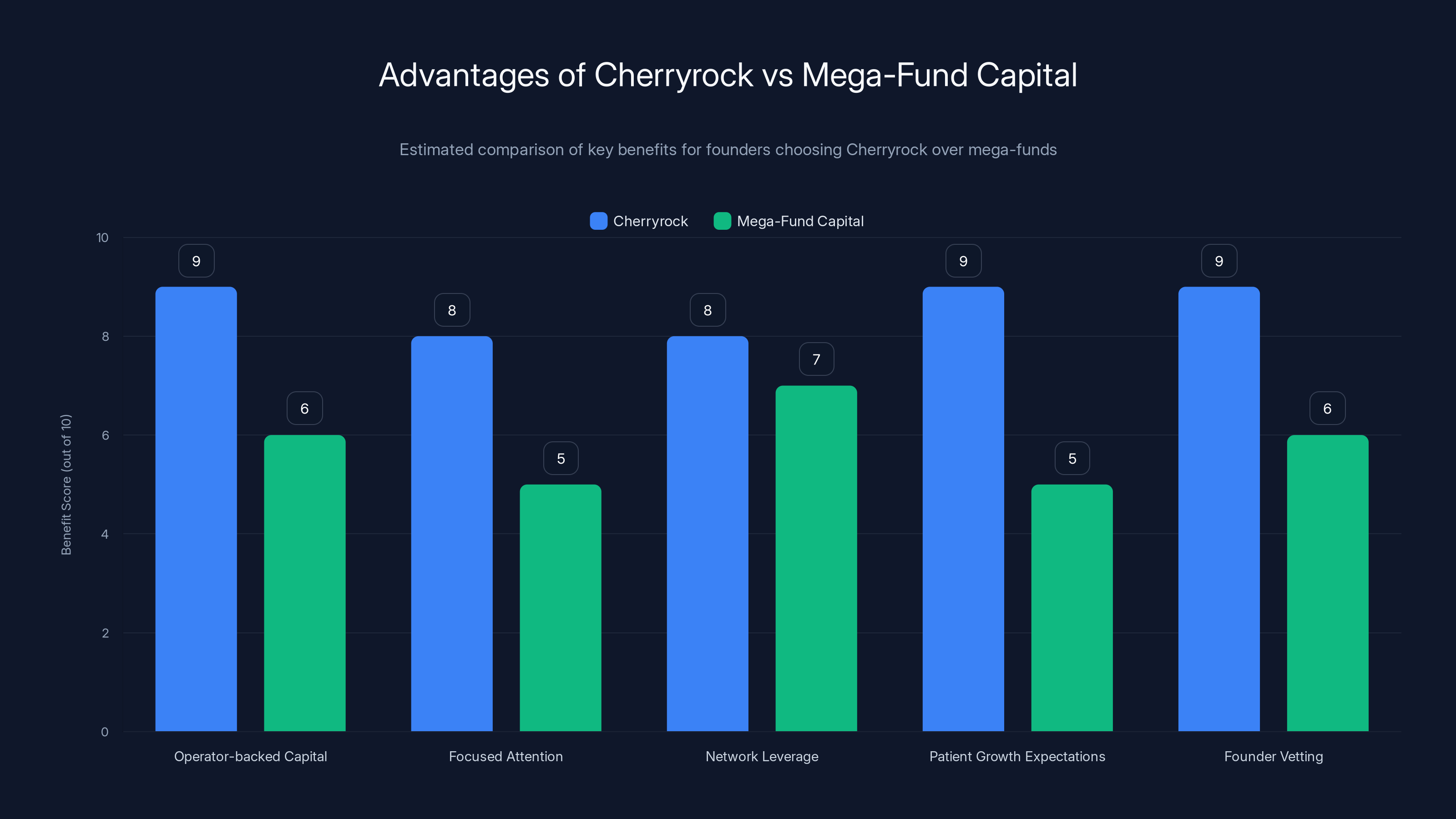

Cherryrock offers significant advantages in operator-backed capital, focused attention, and patient growth expectations compared to mega-fund capital. Estimated data based on qualitative insights.

Brown-Philpot's Network: Strategic Positioning Across Multiple Industries

One thing that separates professional investors from amateurs is network leverage. Brown-Philpot didn't just launch a fund and hope. She positioned herself across multiple strategic boards.

She sits on the board of HP. A hardware company. Enterprise infrastructure. That's not a consumer tech play. That's access to enterprise customers and procurement relationships.

She sits on the board of Stock X. A secondary marketplace for sneakers, streetwear, trading cards. That's e-commerce, logistics, fraud detection, and community dynamics. Three separate skill sets in one company.

She sits on the board of Stanford University. That's not just prestige. That's direct access to the next generation of founders, researchers, and entrepreneurs. Students in 2025 are navigating questions about AI's impact on employment. They're building companies while still on campus.

This network composition is strategic. It's not random. HP gives her enterprise relationships. Stock X gives her marketplace operations experience. Stanford gives her founder pipeline and early trend visibility.

When a founder comes to Cherryrock with a Series A round, they're not just getting capital. They're getting access to someone who can introduce them to HP's procurement team, or who can tell them what mistakes every marketplace company makes, or who can advise them on how to think about employment implications of their product.

The Stanford Insight: What Founders Are Actually Worried About

Brown-Philpot pays attention to what's happening on Stanford's campus because the university is a leading indicator of founder sentiment. When students are worried about something, it usually becomes a company problem within 18 months.

Right now, they're worried about AI's impact on employment. Not as an abstract concept. As a personal question. "Will AI make my skillset worthless? How do I prepare? How do I compete?"

But what she's seeing is students actively charting a path. They're not paralyzed. They're building. "The students are charting a path and finding a way to create opportunities for themselves," she observed.

That's a leading indicator that there's going to be a wave of founders building companies around AI and human employment. Education startups. Reskilling platforms. AI-augmented productivity tools. Tools that help workers understand how to use AI rather than get replaced by it.

Founders who see that trend early and start building companies around it will have a huge advantage. And Brown-Philpot is watching that play out in real time.

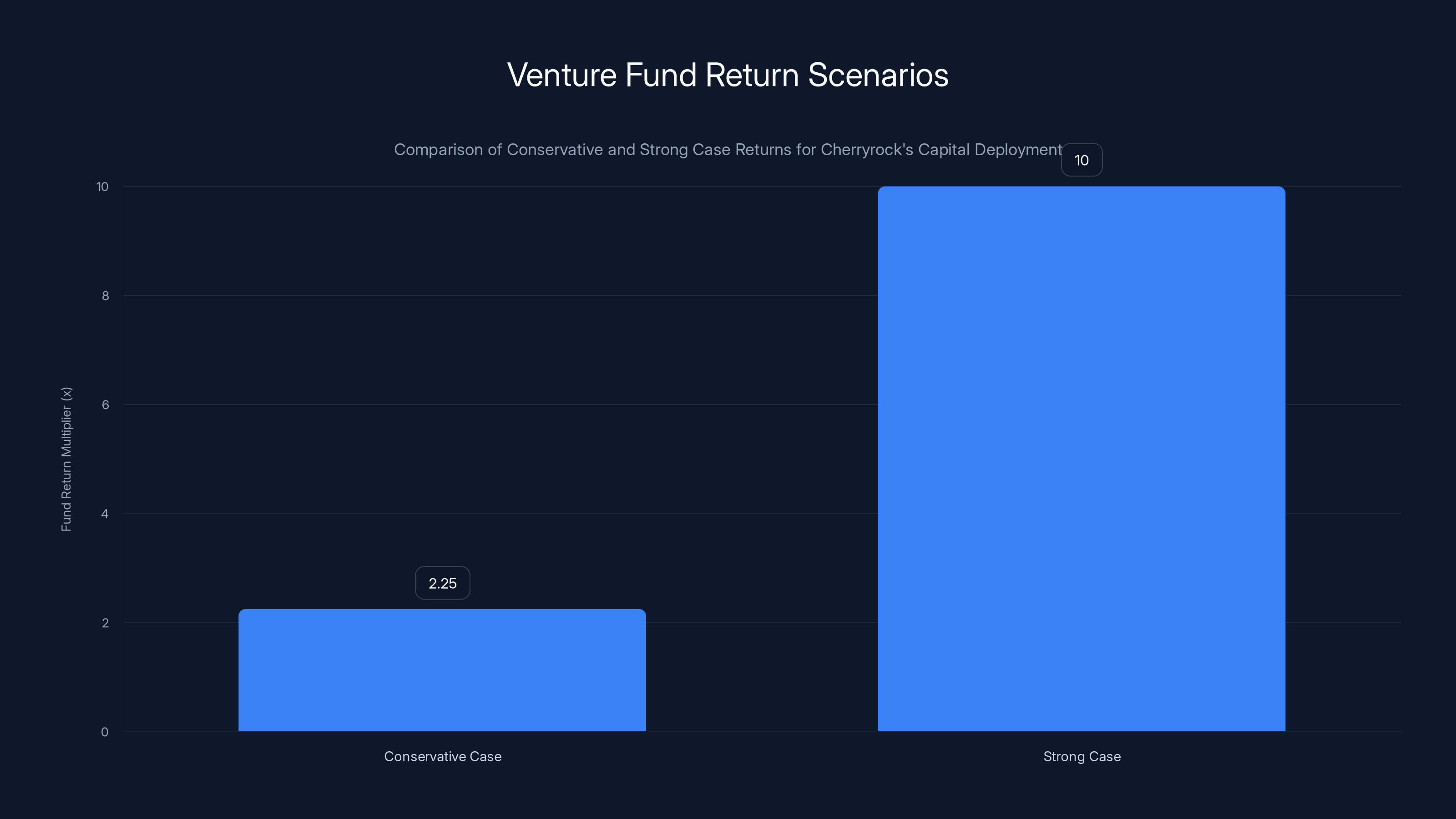

Cherryrock's concentrated investment strategy could yield a 2.25x return in a conservative scenario and up to 10x in a strong scenario, highlighting the potential impact of concentrated betting.

Capital Deployment Strategy: The Math of Concentrated Betting

Let's break down the economics of Cherryrock's model because it's genuinely different from the standard VC playbook.

Assume Cherryrock has

Most funds with that much capital under management are writing much smaller checks and doing many more deals. Why? Because they want optionality. More bets increase the probability of hitting a mega-winner.

But here's the mathematical reality: the distribution of venture returns is heavily skewed. A small number of companies return 100x to 1000x. Most companies return 1x to 10x. Some return negative.

In a concentrated portfolio, your success depends on company selection, not on quantity. You need better diligence. You need better founder insights. You need better conviction.

Brown-Philpot's background actually makes this work. She's not a career VC trying to hit home runs. She's an operator who ran a real business at real scale. She can probably diagnose founder quality better than someone who's only done venture.

The math gets interesting when you consider outcome scenarios:

Scenario 1: Conservative Case

- 12 investments at $16M average

- 6 companies return 3-5x (return $48-80M)

- 4 companies return 1-2x (return $16-32M)

- 2 companies lose money

- Fund return: 2.0-2.5x

Scenario 2: Strong Case

- 12 investments at $16M average

- 2 companies return 50-100x (return $800M-1.6B)

- 4 companies return 5-10x (return $80-160M)

- 4 companies return 1-3x (return $16-48M)

- 2 companies lose money

- Fund return: 8-12x

Most venture firms need the strong case scenario to justify their existence. But they achieve it by making 100 bets and getting lucky on 2-3. Brown-Philpot is trying to achieve it by making 12 bets and getting more of them right.

That requires genuine founder insight. Which she has. That requires founder relationships and deal flow. Which she's building. That requires patience. Which is explicitly part of her model.

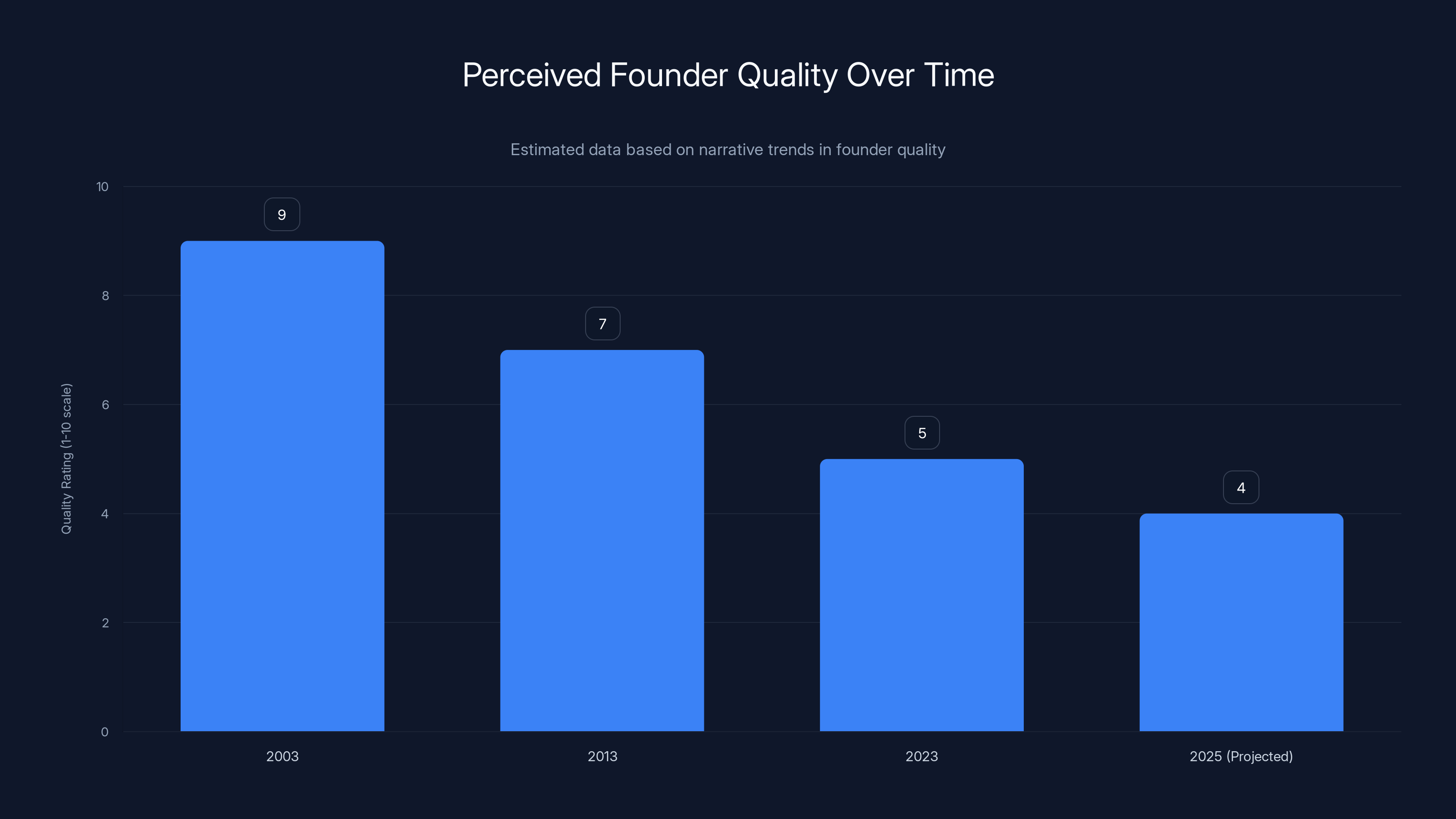

The Founder Quality Problem Everyone Avoids

Here's something almost nobody in venture talks about honestly: founder quality is getting worse, not better.

Twenty years ago, only exceptionally driven people started companies. You had to be willing to sleep in your car, max out credit cards, and work 120 hours a week for years with no guarantee of success. The selection filter was intense.

Now? You can bootstrap slowly. You can raise on a Zoom call. You can get funded as a solo founder with an idea. The bar has dropped.

Most of the founders getting funded by mega-funds in 2024-2025 are fine. They're competent. They might hit venture outcomes. But they're not exceptional.

Meanwhile, exceptional founders who don't fit the current trend ("we're only funding AI," "we're only funding consumer," "we're only funding founders from top schools") are getting overlooked.

Brown-Philpot's thesis is that those overlooked founders are actually better risks. They're more desperate to prove themselves. They have more operational urgency. They've had to think harder about defensibility because they didn't have the luxury of raising a $20 million seed round and just being given market share.

Coactive's Cody Coleman is a perfect example. MIT and Stanford pedigree? Sure. But he also has deep expertise in applied philosophy and engineering. That's not a typical founder background. He's thought deeply about problems before just building.

Vitable's Joseph Kitonga is a Thiel Fellow and YC alum? Sure. But he's chosen to focus on healthcare for gig workers, which is boring but necessary. Not "sexy," which usually means he had to think harder to get funding.

Estimated data suggests a decline in perceived founder quality over the past two decades, with projections indicating further decline by 2025. This reflects the narrative that the bar for founding a company has lowered.

The Risk: What Could Go Wrong?

Let's be honest about the downside scenario. Concentrated funds are dangerous. If you pick 12 founders and 4 of them struggle, your fund fails. That's just math.

Brown-Philpot is betting that her founder insight is better than random. That's always the risk. What if it's not?

Second risk: deployment speed. A year in, five investments out of 12-15. At that rate, it'll take 2-3 years to fully deploy capital. In venture, things can change fast. By the time the fund is fully deployed, market conditions might be different.

Third risk: the "underinvested founder" thesis might be true, but correlated with founder risk. Maybe these founders are overlooked for good reasons. Lack of domain expertise. Unproven team dynamics. Weak go-to-market instincts. You don't get better returns by taking on more founder risk.

Brown-Philpot has thought about these things. But they're real risks. No fund is risk-free.

The Broader VC Landscape Implications

If Cherryrock works—if concentrated bets on underinvested founders actually return better than the shotgun approach—it would be a significant signal.

Right now, the VC landscape is structured for scale. Big funds. Lots of checks. Spray and pray. It's the dominant model because it's the momentum model. When everyone's doing it, it becomes the template.

But momentum models break. They always do. Someone makes a billion dollars doing the opposite, and suddenly everyone copies that approach instead.

Brown-Philpot might be positioning Cherryrock to be that contrarian play. Not for ideological reasons. For purely economic reasons. Better founder selection + patient capital + operational help = better returns.

If that works, you'll see a wave of concentrated, patient, operator-led funds emerge. The mega-fund model will be seen as the 2020s excess. The thoughtful, concentrated model will be the corrective swing back.

We're not there yet. But if Cherryrock's five early bets hit, we might get there faster than anyone expects.

Measuring Success: The 5-Year Lens

Venture funds are ultimately measured by returns. It's the only metric that matters long-term. You can have the best story, the best founders, the best impact—but if your fund doesn't return 3-5x minimum, LPs won't come back.

Brown-Philpot's Cherryrock fund will be judged by that lens. Five investments in the first year. Will those five become category winners? Will they build into public companies or acquisitions that return the fund multiple times over?

The timeline on that judgment is brutal. VCs get about 7 years to deploy capital, then 7-10 years to see returns. So the real evaluation of Cherryrock's first fund won't happen until 2032-2035.

That's a long time. Entire market conditions will change. New technologies will emerge. The founders who are building today might be irrelevant by then.

But that's also why patience is valuable in venture. The companies that change the world are built slowly, with focus, with real product development, not with quick AI pivots chasing the latest trend.

Brown-Philpot seems to understand that. Her measured pace isn't cautious. It's confident. Confidence that she's picking the right companies now, and they'll still be relevant in ten years.

The Founder Perspective: Why Cherryrock Might Be Better Than Mega-Fund Capital

If you're a Series A founder who's raised $5-10 million and achieved product-market fit, you have choices now. You can go after mega-funds. You can go after generalist VCs. Or you can go after specialized, patient funds like Cherryrock.

Here's what you get from Cherryrock that you don't get from others:

Operator-backed capital: Brown-Philpot ran Task Rabbit. She understands what it takes to actually scale a company. That's not theoretical knowledge.

Focused attention: With only 12-15 companies in the fund, she's not spread thin. You're not a portfolio company number. You're a meaningful part of their return equation.

Network leverage: HP, Stock X, Stanford. Those aren't random board positions. That's access to real resources and relationships.

Patient growth expectations: You're not being pushed to grow at all costs. You're being pushed to grow sustainably. That's better for long-term value creation.

Founder vetting: The fact that Brown-Philpot is only backing 5 companies in year one means she turned away a lot. If you get funded, you're among the top 5 candidates she saw. That's validation worth something.

Founders who understand these advantages are probably self-selecting toward Cherryrock. That creates another advantage: better founder quality in the portfolio, which increases chances of success.

Looking Ahead: What's Next for Cherryrock?

If the first fund works, Brown-Philpot will almost certainly raise a second fund. The playbook will be proven. LPs will be ready to commit faster.

Second fund, she'll probably increase to $350-400 million under management. Maybe 20-25 investments. Still concentrated, but slightly larger.

The real question is whether she can stay true to the model as the fund grows. Bigger funds create pressures to deploy faster, to make bigger checks, to take more risk. Can she resist that pressure?

She seems like the type who can. Her background as an operator gives her the credibility to push back against LP pressure. She's not trying to be the biggest fund. She's trying to be the right fund.

That's a surprisingly rare conviction in venture capital, where bigger is usually seen as better.

FAQ

What makes Cherryrock Capital different from other venture funds?

Cherryrock focuses on concentrated bets (12-15 investments per fund) on Series A and B founders that larger funds overlook. Rather than deploying capital quickly like most VCs, Cherryrock takes a measured approach, backed by an operator with direct experience building and scaling companies. The fund's structure emphasizes patient capital and operational support over rapid deployment.

Who is Stacy Brown-Philpot and why does her background matter?

Brown-Philpot served as CEO of Task Rabbit during its final years as an independent company and exit to IKEA, and spent a decade at Google before that. This operational experience informs her founder evaluation skills. She also sat on the investment committee for Soft Bank's Opportunity Fund, giving her institutional insight into founder gaps and capital allocation patterns before launching Cherryrock.

What types of founders is Cherryrock targeting?

Cherryrock backs Series A and B stage founders building software companies that larger funds routinely overlook. These are often founders with strong product-market fit and proven traction but who don't fit current venture trends or narrative. The fund published investments in companies like Coactive AI (multimodal infrastructure for media) and Vitable Health (healthcare for gig workers), showing focus on founders solving real problems in underserved markets.

How does Cherryrock's deployment speed compare to other funds?

After one year, Cherryrock had deployed only five of 12-15 planned investments. This is significantly slower than most venture funds, which typically deploy dozens of checks in year one. Brown-Philpot's measured pace is deliberate rather than hesitant—she views thorough diligence and founder selection as more valuable than rapid capital deployment.

What is the California diversity reporting law and how does it affect Cherryrock?

California's new transparency law requires VC firms with California nexus to report demographic data on portfolio company founding teams, with first deadline in April 2025. Unlike corporate diversity initiatives with legal challenges, this law focuses on transparency without mandates or quotas. For Cherryrock, structured from the start to track these metrics, compliance is straightforward—it actually becomes a competitive advantage compared to unprepared funds.

Why would mega-fund VCs overlook Series A and B opportunities?

A

What does "underinvested founders" mean in Cherryrock's context?

Brown-Philpot uses this language carefully to describe founders overlooked by most VCs—often because they don't fit current narratives (not AI, not mega-round potential, not from typical venture networks), not because they lack quality. Her actual portfolio backs founders with strong credentials (MIT Ph Ds, Thiel Fellows, Y Combinator alumni) who happen to be building in unglamorous markets.

How does founder network and board positions strengthen Cherryrock's model?

Brown-Philpot's board positions at HP, Stock X, and Stanford provide access to enterprise customers, marketplace operations expertise, and early founder trends. These aren't prestige positions—they're strategic leverage. Founders funded by Cherryrock gain access to relationships and expertise beyond capital, creating competitive advantages in operations, distribution, and product strategy.

Key Takeaways

- Concentrated venture funds writing 12-15 carefully selected checks often outperform mega-funds with 100+ portfolio companies by focusing founder selection over quantity.

- Series A and B founders have been structurally overlooked by mega-funds due to economics—a 500M+ fund.

- Operator-led funds like Cherryrock offer founders additional leverage beyond capital through networks (HP, StockX, Stanford) and operational expertise from running real businesses.

- Patient capital deployment (measured over 2-3 years) can paradoxically be more profitable than rapid deployment because it allows for better founder vetting and diligence quality.

- California's new diversity reporting law actually creates competitive advantage for funds like Cherryrock that have tracked founder demographics from inception.

Related Articles

- Venture Capital Split Into Two Industries: SVB 2025 Report Analysis [2025]

- Inertia Fusion: $450M Funding Boom and the Race to Grid-Scale Power [2025]

- Cohere's $240M ARR Milestone: The IPO Race Heating Up [2025]

- xAI Engineer Exodus: Inside the Mass Departures Shaking Musk's AI Company [2025]

- Meridian AI's $17M Raise: Redefining Agentic Financial Modeling [2025]

- Apptronik $935M Funding: Humanoid Robots Reshaping Automation

![Cherryrock Capital's Contrarian VC Bet on Overlooked Founders [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/cherryrock-capital-s-contrarian-vc-bet-on-overlooked-founder/image-1-1771103154768.png)